Some dissidents were not as concerned about imprisonment in a labor camp, prison, or exile as they were about being declared mentally incompetent and confined to a psychiatric hospital. While one could return from a place of incarceration after serving a sentence, the length of stay in a psychiatric hospital was indefinite.

A rally in defense of Soviet political prisoners in Trafalgar Square, London, in 1977. Bohdan Nahaylo interprets for Leonid Plyushch. Seated in the foreground are Soviet dissident Vladimir Bukovsky and British actor David Markham, chairman of the Committee for the Defense of Chornovil in Great Britain.

The practice of systematically using psychiatry in the USSR to isolate dissidents began in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The Khrushchev “Thaw” awakened society, and this frightened the authorities. To curb public activity, they began to use punitive psychiatry. The head of the KGB, Yuri Andropov (1967–1982), played a special role here. In April 1969, he sent a draft plan to the Central Committee of the CPSU to expand the network of psychiatric hospitals and improve their use to protect the interests of the state and society. In addition to more than a dozen special psychiatric hospitals of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs (until 1961 they were called prison hospitals), there were also special wards in general psychiatric hospitals of the USSR Ministry of Health. The basis for placement in a psychiatric hospital was a copy of a court decision ordering compulsory treatment (however, people were also “treated” without a court order).

Among the fifteen or so special psychiatric hospitals of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs, one existed in Ukraine since 1968, in what was then Dnipropetrovsk. It housed such Ukrainian dissidents as Leonid Plyushch, Mykola Plakhotnyuk, Anatoliy Lupynis, Volodymyr Klebanov, Yosyp Terelia, Yaroslav Kravchuk, and others.

The most famous victim of punitive psychiatry was General Petro Hryhorenko. He was a prominent figure in the human rights movement, and thus the authorities tried to explain the Soviet general’s dissent as insanity. As a result, the general spent a total of six and a half years in psychiatric hospitals.

The first psychiatrist to prepare an independent forensic psychiatric evaluation based on Petro Hryhorenko’s case materials, which were passed to him in 1971, was Semen Gluzman from Kyiv. His remote evaluation declared the general sane and proved the illegality of applying repressive psychiatric methods to him. For this, Gluzman himself became a prisoner (seven years in labor camps and three years in exile). Although the conclusion regarding Hryhorenko was remote and therefore not sufficiently weighty for specialists, it had great significance for the public. It was passed on to the West, where it caused a considerable resonance.

The KGB sought to refute Semen Gluzman’s evaluation. In a letter from the camp, he wrote: “In September 1973, an officer from the central KGB, Georgiy Trofimovich Dygas, came to see me. Without any prosecutor’s sanction, I was secretly taken to the visiting house of ITK-36, where for three days, without witnesses, I was subjected to psychological processing. The deal did not go through; I refused. And it was very clear that someone really wanted my help. What if Gluzman agreed to refute the West’s ‘fabrications’ about healthy people being placed in Soviet psychiatric hospitals? And the price offered was not small.”

Forced treatment caused serious harm to a person’s health. In his autobiographical book “In the Carnival of History,” Leonid Plyushch described his “treatment” in the Dnipropetrovsk special psychiatric hospital of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in detail: “The neuroleptics and daily scenes blunted me intellectually, morally, and emotionally. The treatment and regime in the psych-ward, as I saw from my own example, were designed to immediately break a person and destroy their will to resist. Although I tried to spit out the tablets, they killed my desire to read or think, and I quickly lost interest in political affairs, then in scientific ones, and then even in my wife and children. My memory weakened sharply, and my speech became short and abrupt. The only thoughts left in my head were about smoking and bribing the orderlies for an extra trip to the toilet. I didn’t even want visits, which I had previously awaited so impatiently. I became increasingly afraid that my degradation was incurable and that I would help my torturers by going insane. The feeling of hopelessness, of the unlimited duration of my stay in this hell, prompted many sane prisoners to think about suicide. I, too, was losing the will to live. I held on only by self-hypnosis: don’t get angry, don’t forget, don’t give in!”

Leonid Plyushch was a mathematician and publicist. A statement from a group of witnesses about his court hearing reads: “The trial took place in an empty hall. The only representative of the accused was a lawyer, who was denied a meeting with the accused. The lawyer saw him only once, at the conclusion of the case. The witnesses summoned to court were predominantly those who confirmed the accusation. Judge Dyshel told us that the court was only deciding the question of a compulsory medical measure, and since we are not psychiatrists, he did not consider it necessary to invite us to give additional testimony. Something else here is alarming and frightening, namely the investigation’s confidence in the result of the expert evaluation. Some witnesses were told at the very beginning of the investigation: ‘He’s abnormal’ and ‘he doesn’t know what’s waiting for him.’”

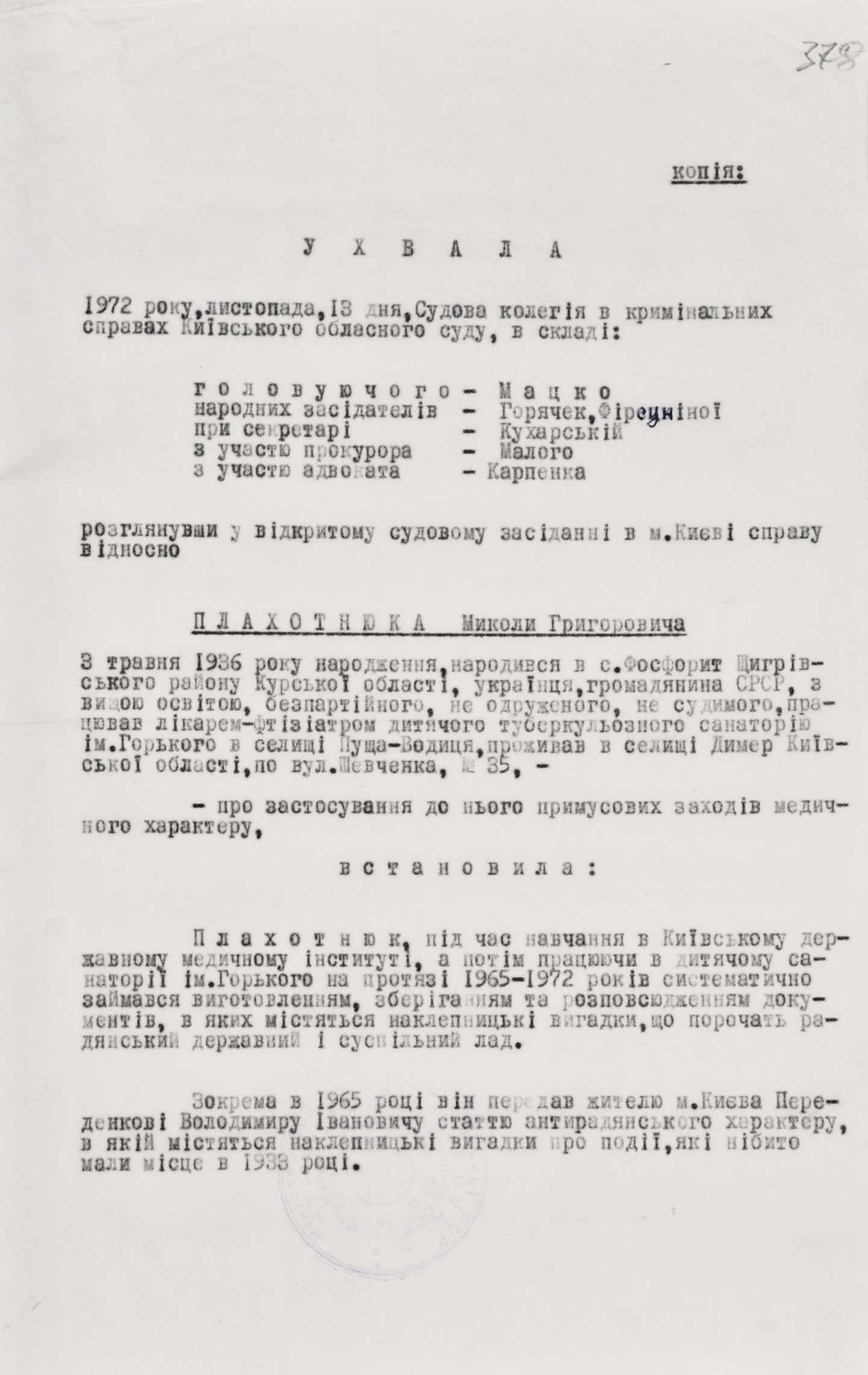

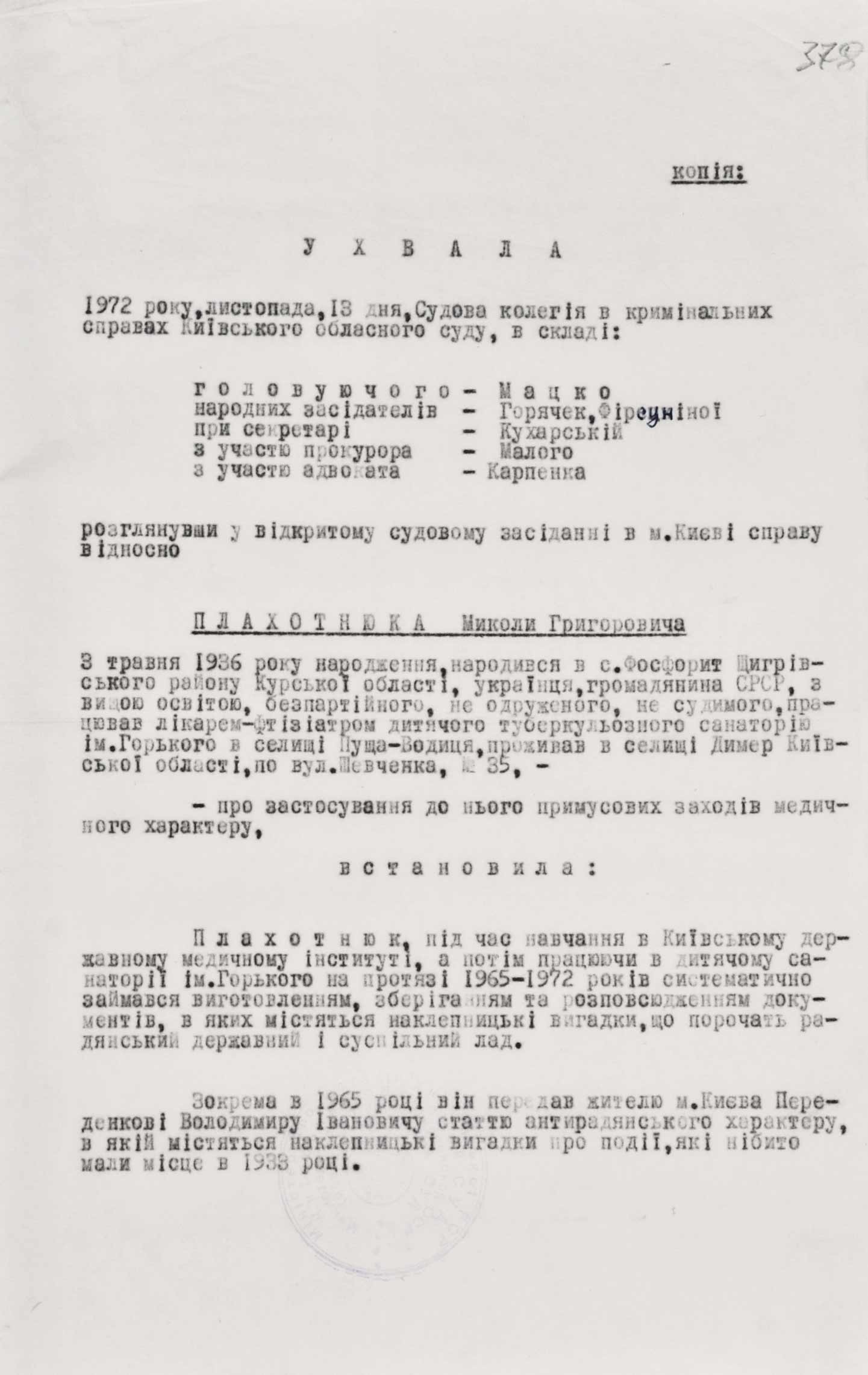

Ruling of the panel of the Kyiv Regional Court regarding Mykola Plakhotnyuk.

November 14, 1972

Ruling of the panel of the Kyiv Regional Court regarding Mykola Plakhotnyuk.

November 14, 1972

However, rallies in defense of Leonid Plyushch were organized in Paris, London, and other cities around the world, and Amnesty International got involved. The leaders of the French, British, and Italian communist parties demanded his release. As a result, Plyushch was released and allowed to emigrate to France, where Western specialists declared him sane, despite his debilitated state. Also, under pressure from the West, General Petro Hryhorenko and psychiatrist Anatoliy Koryagin from Kharkiv managed to emigrate, but such examples are few among the large number of unknown victims of punitive psychiatry. There are examples of people being sent to psychiatric hospitals for wearing a cross or reading the Bible and staying there for a long time. To have a chance of getting out, one had to admit to being ill. But even then, according to Leonid Plyushch’s memoirs, it was not the doctors but “the KGB that makes the diagnosis, prescribes the treatment, and decides when the prisoner has recovered and can be released.”

Another such victim of Soviet punitive psychiatry was the phthisiologist Mykola Plakhotnyuk, who spent 12 years in psychiatric hospitals. In 1972, he was arrested for anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. An evaluation by the V. P. Serbsky Institute for Forensic Psychiatry and the Kyiv Regional Court sent him for compulsory treatment to the Dnipropetrovsk special psychiatric hospital, then to Kazan, and later to the Cherkasy Regional Psychiatric Hospital of the general type.

The forensic psychiatric evaluation report for Plakhotnyuk is quite eloquent: “Mental state: during the interview, the subject holds himself with emphasized freedom and a sense of self-worth. He categorically refuses to conduct the conversation in Russian, stating that he can only convey his thoughts and experiences in the Ukrainian language and therefore insists on the presence of a translator at the interview. When discussing the charges against him, he becomes angry and irritable, stating that he fought and will continue to fight against injustice and the state’s improper attitude toward Ukraine, and repeatedly repeated that Ukraine must be free, that its Russification is unacceptable.”

Ultimately, Mykola Plakhotnyuk was diagnosed with a “chronic mental illness in the form of schizophrenia.” Victims of punitive psychiatry were predominantly diagnosed with “sluggish schizophrenia,” as well as delusions of litigiousness and reformism, and manic psychosis. Regarding this diagnosis, psychiatrist Semen Gluzman recalled an incident: “A leading psychiatrist, the director of the Serbsky Institute and also a major general, Morozov, was giving a lecture, and at the end, one of the forensic experts asked what ‘sluggish schizophrenia’ was. Professor and academician Morozov smiled and said: ‘You see, colleagues, it’s when there are no hallucinations, no delusions, but schizophrenia is present.’”

To protect the victims of punitive psychiatry, the Working Commission to Investigate the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes was created on January 5, 1977, under the Moscow Helsinki Group. Collaborating with it, Kharkiv psychiatrist Anatoliy Koryagin provided independent evaluations of dissidents. Among the volunteers who performed the very important routine work of collecting and transmitting information was Yosyp Zisels from Chernivtsi. The description of physical evidence in his first criminal case (1979) included a card file on patients in special psychiatric hospitals and informational bulletins No. 8 and No. 11 of the Working Commission, and witnesses testified that he informed them about the crimes of punitive psychiatry in the USSR.

The Moscow Helsinki Group’s representative in the commission was the Ukrainian Petro Hryhorenko, and its legal consultant was his lawyer Sofia Kalistratova. In 1977, the lawyer’s petition in the Hryhorenko case was made public at the World Psychiatric Association congress in Honolulu (USA), where a resolution was adopted recognizing the abuse of psychiatry in the USSR. A decision was made to create a committee to investigate cases of abuse, and a resolution was passed condemning punitive psychiatry in the USSR. Through the joint efforts of democratic forces, it was achieved that on January 31, 1983, the All-Union Scientific Society of Neuropathologists and Psychiatrists of the USSR officially withdrew from the World Psychiatric Association.

In 1988, 16 special-type psychiatric hospitals of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs were transferred to the USSR Ministry of Health, and 5 of them were completely liquidated. A total of 776,000 patients were removed from psychiatric registration. In 1989, articles under which anti-Soviet propaganda and slander against the Soviet system were considered socially dangerous activities were removed from the Criminal Code. However, unfortunately, even in our time, on the territory of the former USSR, and Ukraine is no exception, the practice of criminally using psychiatry against healthy people has not been completely overcome, particularly in Crimea.

Aleksandr Podrabinek. Human rights activist, journalist, public figure, one of the co-founders (in 1977) of the Working Commission to Investigate the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes under the Moscow Helsinki Group. Author of the book “Punitive Medicine” (1977), part of which was confiscated by the KGB, while the other was distributed through samizdat. “Punitive Medicine” was written based on materials that Podrabinek collected for three years on more than 200 victims of Soviet punitive psychiatry. The book was presented by Amnesty International at the World Psychiatric Association congress in Honolulu (USA) as proof of the use of punitive psychiatry in the USSR, and in 1980 it was published in the United States. Through the efforts of Aleksandr Podrabinek, some victims of special psychiatric hospitals were freed. He was imprisoned for his human rights activities. He is one of the most respected human rights activists in the post-Soviet space.

Punitive psychiatry in the Soviet Union was a universal tool of political repression and was applied to all dissidents regardless of their social, religious, or national differences. In every Soviet republic, there were victims of the political use of psychiatry. In every republic, there were psychiatrists who agreed to betray their medical duty and support the lawlessness of the totalitarian system.

Robert van Voren. A Dutch Sovietologist, human rights activist, General Secretary of the international organization “Global Initiative on Psychiatry,” and a lecturer at universities in Georgia, Lithuania, and Ukraine. He is the author of the book “Cold War in Psychiatry,” which was published and presented in Ukraine in 2017.

During the Soviet era, and most extensively in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, psychiatry was abused for political purposes in almost all Soviet republics, but it was most prevalent in Russia and Ukraine. The most inhumane psychiatric hospitals were located here. In particular, in the Ukrainian city of Dnipropetrovsk, where many dissidents were subjected to torture with medications and other methods. But it was only after the fall of the Soviet Union that we saw and understood that not only political prisoners suffered: truly ill patients were in no better position; the system broke them as well, right to the very end. Much has changed in the last 30 years, but the remnants of Soviet psychiatry are still there. We hope that a new generation will finally overcome the consequences of the Soviet past...