Unfortunately, in the modern history of Ukraine, there are many individuals who are well-known in foreign lands, where their memory is treated with great respect, their works are published, and commemorative events are held, while at home, the person is known only to specialists, and even then, not to all of them. The general public knows almost nothing about them. Just such a person is Mykola Vasylyovych Horban—a historian and fiction writer, a Ukrainian historian, a regional historian, the creator of the new Cossackophile historical novel, and a public figure.

In my opinion, the best characterization of those times and the tragic events in Ukraine is found in the words of the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset: “Never have so many lives been uprooted from their soil, from their destiny, and carried off who knows where, like tumbleweeds.”

The now widely used term “Executed Renaissance,” with which the famous literary scholar Yuriy Lavrynenko defined the flourishing and recognition of Ukrainian literature in the 1920s and 30s of the last century, and at the same time the ruin, physical destruction, and artificial oblivion of its creators, can equally be applied to Ukrainian science of those times, especially in the humanities.

Mykola Vasylyovych Horban is precisely one of those scholars who were capable of providing Ukrainian science with that high, dreamed-of European level. But it was not to be…

Mykola Horban was born on December 22, 1899, in the Hetmanate, in the village of Mykolaivka, Kostiantynohrad County, Poltava Governorate. His father was a zemstvo teacher who, from an early age, instilled in his son a love and respect for education, books, and the vibrant and distinctive Ukrainian culture. While still a student at the gymnasium, Mykola Horban joined the youth union of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (UPSR) and later became a member of that party.

In 1917, he graduated from the gymnasium with a gold medal and became a student at the Faculty of History and Philology of Kyiv University. The political events in Kyiv—the dispersal of the Central Rada, the Hetman’s coup, and the occupation of Ukraine by Austro-German troops—were turbulent, and the young Horban immediately became an active participant. He was a member of the Council of United Student Communities and was arrested during one of the mass student demonstrations against the Hetman’s rule, but not imprisoned. After his apartment was searched by the Hetman’s guards, Horban went underground and returned to Kostiantynohrad, where he worked in the department of public education and took an active part in organizing the local “Prosvita” and in the county branch of the UPSR. During the Denikin occupation, his apartment served as an underground meeting place for the Socialist-Revolutionaries. Mykola Horban took an active part in the celebration of Ivan Kotliarevsky’s anniversary, which turned into a mass protest against Denikin’s rule; he was arrested as one of the organizers and exiled from the Poltava Governorate with a ban on residing in Kyiv.

In 1920, Mykola Horban enrolled in the Faculty of History and Philology at Kharkiv University, from which he graduated in 1921. It was during his studies that Mykola Horban met his future academic supervisor, Academician Dmytro Bahalii. Mykola Horban treated his professor with great respect and interest and became fascinated with the questions that Dmytro Bahalii and his colleagues at the Research Department of the History of Ukrainian Culture were studying. Dmytro Ivanovych Bahalii, in turn, paid interested attention to the talented student who was in love with the history of Ukraine and treated him with sympathy. Dmytro Bahalii was attracted not only by his high level of general education but also by his knowledge of foreign languages, especially Latin. Mykola Horban’s natural persistence and his desire to get to the bottom of a scientific problem on his own also attracted the famous historian. In those years, Dmytro Bahalii even refused for a time to teach at the Institute of Public Education because the general level of students, who often lacked a gymnasium education, was very low, and the level of politicization was very high. And Mykola Horban was a bright personality against this gray background of semi-educated students.

This acquaintance between Dmytro Bahalii and Mykola Horban grew into a close scientific collaboration, and after graduating from the university in 1921, Mykola Horban became a researcher at the Research Department of the History of Ukrainian Culture, first as a postgraduate student, then as a research fellow, and in the second half of the 1920s, he headed a sector at the Institute of Ukrainian Culture and was Bahalii’s deputy. In addition, Mykola Vasylyovych worked as a research fellow at the Institute of Oriental Studies. At the Research Institute of Oriental Studies, he worked on the commission for the study of Ukrainian-Turkish relations. By the way, an interesting detail: in 2003, the “Biobibliographical Dictionary of Orientalists—Victims of Political Terror in the Soviet Period (1917–1991). People and Fates” was published in St. Petersburg, which contains data on two Kharkiv residents, employees of the Research Department of the History of Ukrainian Culture—Andriy Petrovych Kovalevskyi and Mykola Vasylyovych Horban.

Mykola Horban’s financial situation, both during his postgraduate studies and at the beginning of his work as a research fellow, was quite difficult, and he was constantly engaged in additional work to earn a kopeck, which was necessary for both living and “for spiritual sustenance.” In the first half of the 1920s, he worked as a teacher at the Kotliarevsky School, in the editorial office of the newspaper “Visti,” headed a department of the Central Committee of the CP(b)U newspaper “Selianska Pravda” (1921–1925), and lectured at the Skovoroda Pedagogical Courses. In 1926–27, Mykola Vasylyovych edited materials for the Ukrainian department of RATAU.

In the 1920s, Mykola Horban lived at 25 Rymarska Street, apartment 18. The living conditions remain unknown; most likely, it was a communal apartment typical for Kharkiv of that time. The building has not been preserved. But one can say for sure that Mykola Horban’s residence was in the very center of the “literary map of Kharkiv,” as all the editorial offices of republican and Kharkiv newspapers and magazines were located in this area.

Vivid memories of the team at the Research Department of the History of Ukrainian Culture from the time when Mykola Horban worked there were left by Nadiia Surovtsova, an outstanding Ukrainian woman, writer, translator, historian by profession, journalist, public and political figure, and a long-term prisoner of the GULAG. “…With the old and ‘solid’ ones, like Ohloblin, Vetukhov, Tatarynova, Vetkina, Avakiants, I did not maintain contact beyond the department’s affairs. But with some of the ‘boys,’ like Mykola Horban, Tikhonov, Nazarenko, and Petrov, we would sometimes go to some tavern on Katerynoslavska Street after a department meeting and have lunch, or dinner, or whatever you would call our meetings. Even during the meeting, someone with a preoccupied look would pass me a supposedly ‘scientific’ note under the nose of the all-seeing, vigilant Bahalii. Sometimes the note would ask if I had any ‘worms’ (as the young Kharkivites called the Soviet chervontsi—*ed.*). I earned more than them or perhaps spent less, and more than once I credited our ‘banquets.’ After the meeting, one had to act in such a way that it would not even occur to Dmytro Ivanovych (Bahalii) where his protégée had gone […]. So we would dash off to our tavern, and the boys knew this side of Kharkiv well, as they frequented them quite often. And time passed so wonderfully in conversations, interesting, scientific ones! But with a drink, and sometimes a decent drink. We loved these extraordinary ‘department meetings’ of ours. […] The lifestyle (of Nadiia Surovtsova—*ed.*) was bohemian. People came to my place whenever they wanted, the key was in a known place, food and wine were at the guests’ service; during my absence, they would come, eat, drink, sleep, work.” Artists Oleksandr Dovzhenko, Ivan Padalka, Mykhailo Yalovyi, Pavlo Tychyna, Ostap Vyshnia, Petro Panch, Mykola Bazhan, Yuriy Yanovskyi, Maik Yohansen, Valerian Polishchuk, Mykhailo Semenko, Volodymyr Sosiura, Mykola Khvylovyi, Hnat Khotkevych, Les Kurbas... and also politicians Yurko Tiutiunnyk, Mykhailo Levytskyi, Hryts Kossak, Karlo Maksymovych, Shlikhter with his wife, Academician Bahalii, Professor Oleksandr Ohloblin, scholar and writer Mykola Horban, and others would visit her or she would visit them. Such a wide circle of acquaintances and interests would later play a cruel joke on our heroine... Nadiia Surovtsova would spend 29 years in the GULAG, but she would survive and return to her native Uman.

At the end of the 1920s, the name of the young, talented researcher Mykola Vasylyovych Horban appears among the active figures of various historical commissions of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. His work in the Commission for the Study of the History of Sloboda Ukraine, headed by D. Bahalii, was particularly fruitful.

In 1929, he was elected academic secretary and a full member of the Archaeological Commission of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. At the Research Institute of Oriental Studies, he was on the commission for the study of Ukrainian-Turkish relations. By this time, he was fluent in French, German, Greek, Latin, and Turkish. A number of his articles and brochures on the history of Ukraine from the 16th to 18th centuries, published in these years, attract the attention of specialists with their breadth of problem-setting, considerable deliberation, polished approaches, and careful processing of archival sources. Mykola Vasylyovych worked very hard during this time, but the feeling of the “terrible times of terror” was oppressive—and not without reason.

In the “History of Ukrainian Literature,” published in Kyiv in 1965, Mykola Horban is named one of the founders of the historical genre in Ukrainian Soviet literature. The “Ukrainian Literary Encyclopedia” of 1988 also reports on his historical novels and other works, naming the novels “Cossack and Voivode” (Rukh, 1929), “The Sovereign’s Word and Deed” (Rukh, 1930), “The Hlukhiv Uprisings of 1750” (1929), “Echoes of the Decembrist Movement in Sloboda Ukraine” (1930). In total, before his arrest, he published over one hundred works (as separate editions, articles in journals and newspapers).

At the end of the 1920s, the Bolshevik regime faced new challenges in domestic and foreign policy. The Kremlin became firmly convinced that internal turmoil, combined with a series of crises in international relations, was weakening the USSR’s position and contributing to the activation of “counter-revolutionary,” “wrecking,” and nationalist forces. The revival of the latter was largely associated with the policy of “Ukrainization.” Therefore, it was decided in the higher echelons of power to hold several open political trials aimed at intimidating society, i.e., implementing a policy of terror.

In 1930, the GPU of the Ukrainian SSR in Kharkiv began preparing the case of the “Ukrainian National Center” (UNC), which, according to the plan of the falsifiers, was supposed to surpass the previously fabricated case of another anti-Soviet organization, the “Union for the Liberation of Ukraine” (SVU), in resonance and scale. The organizers of the next political farce tried to make Academician Mykhailo Hrushevskyi the “leader of the rebels.” But later, the leaders of the OGPU realized that they would not be able to make Hrushevskyi the main figure of the accusation, and after consulting with the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), he was released.

Mykola Vasylyovych Horban was arrested on April 6, 1931.

As a result of the case fabricated by the Chekists, 50 people were arrested and sentenced to terms of 3 to 6 years. Mykola Horban’s “accomplices” in this case were the academic secretary of the People’s Commissariat of Agriculture, Nazar Petrenko, a research fellow at the VUAN and secretary of Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, Fedir Savchenko, Academician Matvii Yavorskyi, the head of the “Rukh” publishing house, Ivan Lyzanivskyi, and others. In 1934–1941, 33 of them were re-convicted for “anti-Soviet activity” and “espionage,” and 21 were shot. Most of those who received new sentences died in the camps.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

“From the indictment in the case of the ‘Ukrainian National Center’”

October 21, 1931

“APPROVED”

Deputy Chairman of the State

Political Directorate of the UkrSSR

K. M. Karlson

– Horban, Nikolai Vasilevich, 32 years old, son of a teacher, former member of the UPSR, former research fellow of Kharkiv research institutions, historian-literateur. He was an active member of the organization from its inception and carried out counter-revolutionary activities in the scientific and cultural field, being a conductor of the organization’s counter-revolutionary ideas and directives. This crime is provided for by articles 54-10 and 54-11 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR. He pleaded guilty.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Historians consider the “UNC” case as one of the decisive steps in Stalin’s opposition to “Ukrainization,” as a stage in the extermination of those intellectual forces (including among the communists themselves) who were the bearers of the national revival of Ukraine.

In 1965, Mykola Shrah, a former member of the Central Committee of the UPSR who was also arrested in the “UNC” case, recounted: “During the investigation in 1931, forbidden methods of investigation were used against me. Frequent interrogations at night, standing on my feet during interrogations, shouting and insults from the investigators Pustovoitov, and sometimes Kogan, physically and morally exhausted me and demoralized me… I knew nothing about any organization, I was not involved in wrecking or preparing an uprising. At the investigators’ demand, I named former members of the UPSR, my acquaintances, as participants in the counter-revolutionary organization… I wrote everything they demanded of me, so that they would not summon me at night and shout at me. Sometimes I even wrote under the dictation of the GPU employee Pustovoitov.”

Mykola Horban could not endure it either. Later, in 1956, in his official statement to law enforcement agencies, he noted: “Lyzanivskyi and Holubovych did not involve me in any counter-revolutionary organization, although in 1931, during the investigation, as far as I know, they did testify that they had allegedly recruited me into a counter-revolutionary organization. During the investigation in 1931, I confirmed their testimony, but neither my testimony nor theirs on this matter corresponded to reality. I gave testimony in 1931 about my own and other persons’ counter-revolutionary activities because I was then in a state of complete mental breakdown.”

After ten months of imprisonment in Ukraine, he was charged under Art. 54-10 and 54-11 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR and sentenced under Art. 58/11 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR (Resolution of the Collegium of the OGPU of the USSR of February 7, 1932) and exiled to Alma-Ata (*now Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan*) for three years.

Thus, two days before the death of his teacher Dmytro Bahalii, his favorite student and colleague, Mykola Horban, was exiled from Ukraine.

While in Alma-Ata, the scholar worked extensively and fruitfully, engaging in scientific and pedagogical work, preparing reviews of archival documents, several original works on the history of Kazakhstan, and publishing guides to the archives of Alma-Ata.

He hoped that the worst was behind him, but in December 1933, he was arrested again by the GPU organs of Kazakhstan. This time, Mykola Horban was accused of hostile counter-revolutionary activity, which they saw in the work of the Ukrainian community in Alma-Ata. During the investigation, it was determined that an underground group of the Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO)—an illegal revolutionary-political formation—allegedly existed within the community.

Before his rehabilitation in 1960, Mykola Vasylyovych was interrogated in the investigative department of the KGB of the Uzbek SSR. During the interrogation on February 15, 1960, Mykola Horban recounted that after arriving in Alma-Ata, he first worked as a lecturer at the Alma-Ata Medical Institute, then as a research fellow at the Central Archival Administration of Kazakhstan. While in Alma-Ata, Mykola Horban met and communicated with Ukrainians exiled to Kazakhstan—“Ukrainian nationalists”—Polei Pavlo, Vysochanskyi, Panchenko, Koliukh Dmytro, Balandin Vasyl, Pushkar, Krotevych, Odarchenko, Mazurenko Vasyl, Dubrovskyi, and others. Among the exiles in Alma-Ata, the only ones he knew from Kharkiv were Balandin, an employee of the People’s Commissariat of Education of Ukraine, and Mazurenko, a professor at the Kharkiv Institute of Measures and Weights.

During the same interrogation, Mykola Vasylyovych recounted that he was forced to give a confession in 1934 because the investigator handling the case threatened that if he did not receive incriminating testimony, they would arrest Mykola Vasylyovych’s wife, who lived in Kharkiv, and place her with him, because, according to the investigator’s assertion, Mykola Vasylyovych’s wife—Horban Nadiia Vasylyvna—was allegedly a liaison between the groups of Ukrainian nationalists in Kharkiv and Alma-Ata. “I was afraid for my wife because she was ill, and I thought that if they arrested her, she would die.”

Mykola Vasylyovych was exiled for three years (1934–1937) to the distant city of Tobolsk. Here he worked as a senior research fellow at the Tobolsk State Archive, which is one of the oldest and most significant archives in Russia in terms of the number and value of its documents. The administrative status of Tobolsk, which was the capital of the vast territory of Siberia in the 18th–19th centuries, influenced the formation of the archive’s document collection. It houses the funds of provincial institutions, which reflect all aspects of the economy, social development, and life of Siberia. The earliest documents date back to the first half of the 18th century.

After his exile ended, Mykola Horban moved to Omsk. In Omsk, he worked as a teacher of literature and German in secondary schools, and from September 1953, he taught Latin at the Omsk Medical College, and then until February 1960 at the Medical Institute and the Veterinary Institute. At the same time, he worked at the Omsk Regional State Archival Administration (1937–1939), and this was his main activity. From 1945 to 1948, he was a lecturer, then an associate professor at the Department of History of the USSR at the Omsk Pedagogical Institute (1948–1950). In 1946, he defended his candidate’s dissertation at Leningrad State University on “The Movement of Peasants of the Spiritual Estates of the Tobolsk Diocese in the 18th Century,” and prepared a doctoral dissertation on “The Peasant War of 1773–1775 in Western Siberia,” in which he used materials from the archives of Moscow, Leningrad, Omsk, Tobolsk, Tyumen, and Tomsk. In any life situation, he did not cease his scientific activity, which remained the meaning and content of his life.

Unable to publish large works, he sought to introduce a large number of discovered archival materials into scientific circulation. In the huge array of his newspaper publications (over three hundred), several leading themes can be identified: the civil war in Siberia, the history of culture, the history of the peoples of Siberia, and the history of the church. Many of these articles in district and regional newspapers were reprinted by “Pravda” and “Izvestia.”

A purely Omsk theme of his scientific work was a series of brochures on the electoral system in Omsk before the revolution. Using the first post-war elections to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR as a pretext, the scholar introduced a large volume of factual material into the brochures. From 1957, he was a member of the Omsk branch of the Geographical Society of the USSR.

A brilliant lecturer, an interesting conversationalist, he could hold the attention of any audience without special effort. And his teaching work at the pedagogical university fully corresponded to his preferences.

But although Mykola Vasylyovych received some concessions from the KGB and was allowed to teach history, his criminal record remained, and he could not freely travel to his native Ukraine, and certain restrictions on publications also remained.

In the post-war period, Mykola Vasylyovych constantly appealed to the KGB with a request to review his case, proving his innocence as best he could. However, his requests were constantly met with refusals.

In 1950, another Stalinist “witch hunt” began—the fight against cosmopolitanism, and at the same time, Zionism. And they remembered Mykola Horban’s old “political sins,” accusing him of new crimes. Horban bitterly ironized: “Cosmopolitans and nationalists of all countries—unite!” At the insistence of the regional party committee, Mykola Vasylyovych was dismissed from his job at the pedagogical institute, and at the same time, they forbade him from holding a second job in the archival department.

Only on April 27, 1960, was Mykola Horban rehabilitated by the Supreme Court of the Kazakh SSR.

In 1988, a full additional review of the “UNC” case was conducted, as a result of which the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR closed the criminal case against three of the repressed individuals due to the absence of a crime in their actions, and the remaining 47 people were rehabilitated on the basis of the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of January 16, 1989, “On additional measures to restore justice for the victims of repressions that took place during the 1930s-40s and the beginning of the 50s.” But Mykola Horban did not live to see such a full clarification of the circumstances of this political case…

Let’s return to his life in Omsk. There, Mykola Vasylyovych met Debora Yakovlevna Sapozhnikova, a well-known literature teacher in the city. In 1945, a close relationship began to form between the young beauty and Mykola Horban. The age difference—almost twenty years—was something of an obstacle.

Debora Yakovlevna left an account of her acquaintance with her future husband. They were introduced by a close friend of Debora Yakovlevna—Raisa Azaryevna Reznik.

“Nikolai Vasilyevich Horban, who became my husband a year later, was invited to one of the evenings. A Ukrainian writer, historian, and archivist, he had been in prisons and exiles since 1931. He was subjected to various forms of persecution for the rest of his life. At the evening at Michurina’s, he was introduced as a Latin teacher, but he captivated everyone present with a story about his finds in the Tobolsk archive, where he had worked during one of his exiles.”

“…a particularly memorable—a joint burst of impressions occurred on May 9, 1945. It so happened that Victory Day became the starting point of my fate and did not pass by two people close to me. I think I have the right to such a conclusion. We were together all day. In the morning, in the dormitory, we drank a bottle of red wine saved for the great day (at that time, wines were divided into white—vodka, and red—everything else), and snacked on food each had brought. Then, separating from the motley company, the three of us found ourselves on the streets of Omsk. We walked without a goal, just merging with the stream of excited people, overwhelmed with happiness and pain, feeling the warmth and unity of strangers who had become tearfully close, who greeted us with gestures and bright smiles. I don’t remember how evening fell and night came. It was unseasonably warm. We didn’t want to go to our usual squalid dwellings, which reminded us of the war years that had just ended on this very day, in silent agreement.

[…] We spoke quietly, sat in silence for long periods. We read poetry, mostly about nature, eternity, and beauty.

Despite such a joyful event, our mood could be called elegiac.

N.V. read Tyutchev and much more in his own ‘mova’ (language). From that night, I remember this (and have heard it many times since):

The hornbeams stand, transparently yellow

In a bright, golden mist.

So what if you haven’t found happiness, my friend,

Why should you grieve for it?

Steer your youthful searchings

Toward the lake of tranquility,

For all that remains behind you—

Is but the trail of a small oar on the water…

(A poem by Maksym Rylsky, “Red Wine”)

At such hours, memories are inevitable—a turning point of time and life. N.V.’s turn to his ‘mova’ is also a kind of memory.

It began to get light, we quietly walked to the dormitory—to see R.Az. off. Then N.V. walked me home. We walked slowly and almost silently, ‘without our sleeves touching.’ The streets at such an early hour were more lively than usual: after the festive night, everyone was crawling back to their lairs to get to work—holidays were not granted. And we crawled back to our lairs, but the unity that arose lasted for the rest of our lives.”

The young woman, captivated by the mind, poetic nature, kindness, and suffering of this extraordinary person, decided to protect him, at least partially, from the vicissitudes of fate. She succeeded—they created a family. On April 19, 1952, a son, Oleksandr, was born into the family.

After new accusations of “cosmopolitanism-nationalism” in 1950 and his dismissal from work, Mykola Vasylyovych found a job for a pittance in an archive and as a Latin teacher in a medical college. For meager fees, he published newspaper notes based on archival finds without a byline, under other people’s names. He did work “for the other guy and for the other guy’s benefit,” sometimes even for a “bottle.” He often drank—a kind of anesthesia against life’s troubles. Eventually, after living with Debora Yakovlevna for fourteen years, Mykola Vasylyovych went to Tashkent to teach Latin at the medical institute. But his friendly relations with Debora Yakovlevna and his affection and love for his son remained until the last days of his life.

From the mid-1960s, Mykola Vasylyovych began to visit Kharkiv to see the graves of his loved ones and, as he wrote to Yuriy Bahalii, to “visit the city with which I have so many wonderful and good things connected.”

Mykola Vasylyovych died on April 19, 1973, by a tragic coincidence, on the birthday of his son, Oleksandr. He is buried in a cemetery in Tashkent.

In the Historical Archive of the Omsk Region, Mykola Vasylyovych Horban is remembered with great respect. It is here that his personal archive is kept. Here are lines from a letter from one of the employees of this archive: “Your countryman, and for us, a colleague, N. V. Horban was and remains the greatest authority not only in archival activities but also as a writer, researcher, teacher, and simply an honest and noble person. We have a rather large volume of documents on N. V. Horban. There is an N. V. Horban award, readings dedicated to Nikolai Vasilyevich are held, and 2 brochures of these readings have been published. There are many publications by N. V. Horban and articles about him. An evening in memory of N. V. Horban was also held, attended by his widow, Debora Yakovlevna Sapozhnikova, and his son, Aleksandr Nikolaevich Horban.”

Political persecution also affected Horban’s son. Mykola Horban, who had spent many years in exile and prisons, once recounted that in his Tobolsk exile, an anarchist used to check in with him—along with his daughter—and would joke: “Mykola, when I die, my daughter will check in for me, but when you die, who will go check in for you?” These words turned out to be prophetic. Mykola Horban’s son, Oleksandr, organized a student protest against political trials in 1968. The all-powerful Y. V. Andropov and M. A. Suslov personally intervened in his fate. Despite this, Oleksandr Horban was eventually able to get an education and become a famous mathematician.

Oleksandr Mykolayovych Horban lives in Great Britain, holds a Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences degree, is a professor at the University of Leicester, where he heads the Centre for Mathematical Modelling and the Department of Applied Mathematics, and works in many fields of fundamental and applied science, including statistical physics, machine learning theory, and mathematical biology. He is the founder of new scientific directions and schools in the field of physical, chemical, and biological kinetics, and the theory of dynamical systems. He has organized several dozen Russian and international conferences and is the founder of several physics and mathematics schools for gifted children.

The year 2019 marks the 120th anniversary of the birth of Mykola Vasylyovych Horban. And the Omsk Historical Archive is already preparing to mark this date. A question for the numerous contingent of Kharkiv historians: perhaps Kharkivites will also remember their famous countryman? In my opinion, it would be quite logical if the H. S. Skovoroda Kharkiv National Pedagogical University took the initiative.

Sources Used

1. V. S. Loburets. “A Vocation—Regional Historian (M. V. Horban).” Collection “Repressed Regional Studies.” 1991.

2. Nadiia Surovtsova. *Memoirs*. Olena Teliha Publishing House. 1996.

3. Volodymyr Prystaiko, Yuriy Shapoval. *Mykhailo Hrushevskyi: The “UNC” Case and the Final Years (1931–1934)*.

4. Oleksandr Leifer. To Unravel God’s Design…

5. Personal archive of the Bahalii family.

Photo of the staff of the Department of the History of Ukrainian Culture at KhINO, 1927. Seated: Head of the department, Academician D. I. Bahalii (center), to his right, Head of the Russian History section, Prof. V. I. Veretennikov, further right, Head of the Ethnological-Regional Studies section, Prof. O. V. Vetukhiv, and research fellow O. D. Bahalii-Tatarynova; to the left - full member V. O. Barvinskyi, research fellow O. H. Vodolazhchenko, and full member N. Yu. Mirza-Avakiants. Standing: postgraduate student N. V. Surovtsova, research fellow A. P. Kovalivskyi, postgraduate student Sevastianov, postgraduate student A. I. Kozachenko, postgraduate student O. Nazarets, research fellow M. V. Horban, postgraduate student M. M. Tikhonov

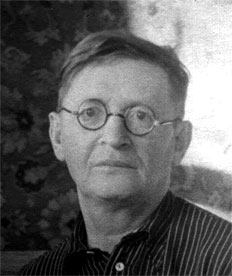

Mykola Horban in the reading room of the Omsk Historical Archive

Students of the regional courses for heads of district archives at the archival department of the NKVD for the Omsk region and employees of the State Archive of the Omsk Region. 2nd from the left in the first row is M.V. Horban

Participants in the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the birth of M. V. Horban, held at the State Archive of the Omsk Region on March 6, 2002. 3rd from the left is Debora Yakovlevna Sapozhnikova, 4th from the left is M. V. Horban’s son, Oleksandr

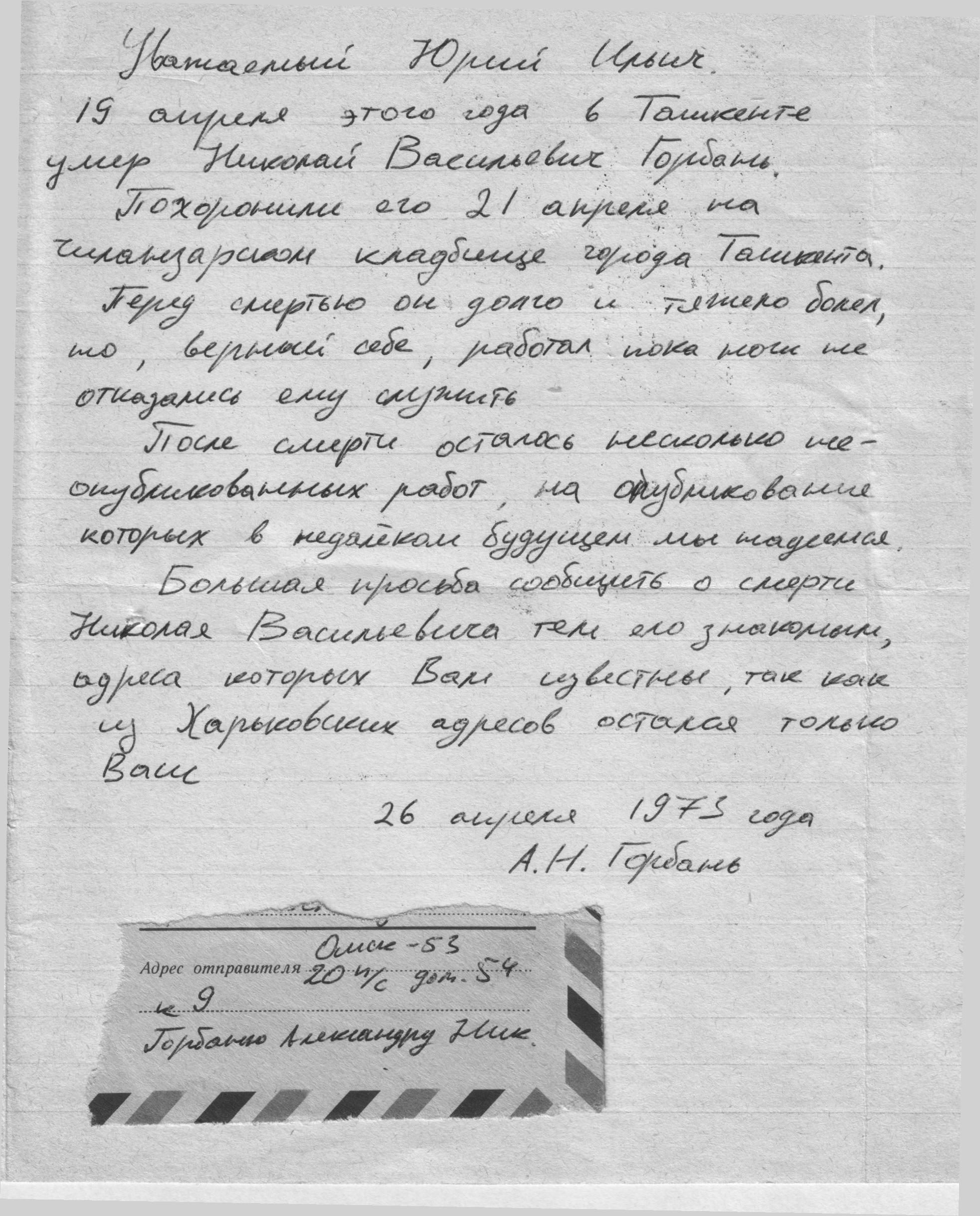

Letter from Oleksandr Horban to Dmytro Bahalii’s grandson, Yuriy Volodymyrovych (the patronymic in the letter is incorrect), about the death of Mykola Horban

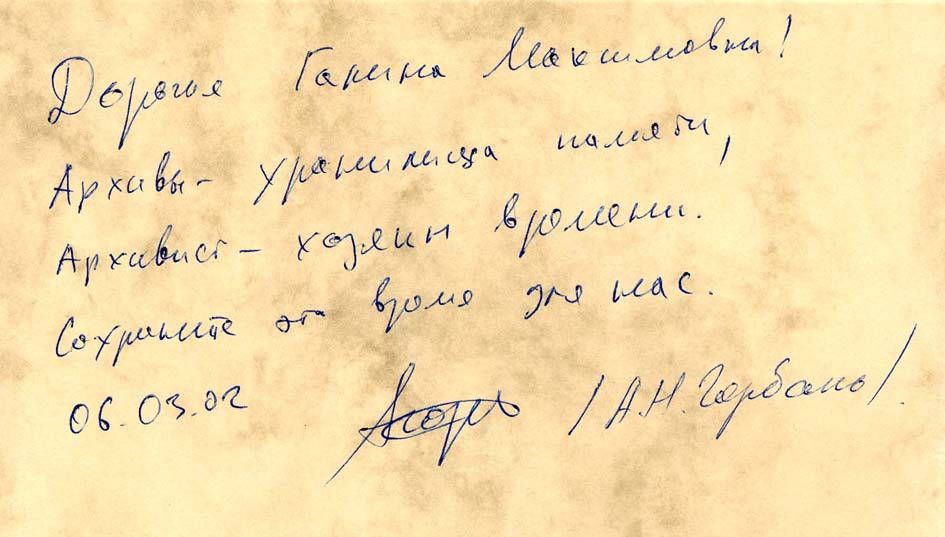

Autograph of Oleksandr Horban—son of Mykola Horban