As soon as members of the Ukrainian diaspora became acquainted with the Convention on Genocide, they translated this word into Ukrainian as narodovbyvstvo (nation-killing) and began to apply these terms to the famine of Ukrainian peasants in the 1930s. The word Holodomor came into use in the late 1980s, and after Ukrainian independence, it became the standard name for that horror. Subsequently, the Holodomor appeared in the English language, analogous to the Holocaust. But while “the Holocaust” evolved from its etymological meaning of “total burning” to “the genocide of the Jews,” “the Holodomor” retained its etymological sense of “to kill by starvation.” And here is the bitter irony: in Ukraine and around the world, the Ukrainian name “Holodomor” has established and preserves a mistaken and harmful concept that narrows the understanding of the genocide of Ukrainians to only the famine of the peasants. Lemkin did not use this term.

Raphael Lemkin, the author of the term and the concept of genocide and the father of the UN Convention on the Crime of Genocide, rejected such a reductionist understanding of the genocide of Ukrainians. Lemkin viewed the Ukrainian catastrophe of the 1930s as a stage in the construction of the Russian empire, and he treated it as such in his essay “Soviet Genocide in Ukraine.” The paper was written in 1953 for the commemoration of the Great Famine in New York but was not read there at the time. Unfortunately, the author did not publish it before his untimely death in 1959. Fortunately, a typescript of the paper was preserved in the New York Public Library but only became available to scholars in 1982, and Holodomor researchers did not see it until 2008. Since then, scholars and politicians have often mentioned Lemkin and his essay, but most of their interpretations of Lemkin’s theses are superficial and do not reveal the profound thought of the jurist or the full content of the topic he conceived.

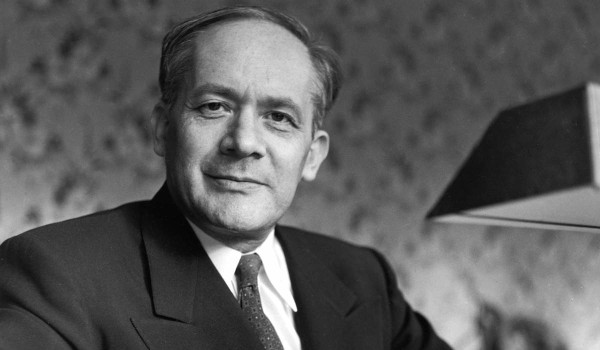

Raphael Lemkin (Rafał Lemkin)

The task of this short paper is, first and foremost, to prove that Lemkin’s theses were formulated in accordance with the UN Convention and that their correctness is confirmed by historical documents. The second goal is to show that Lemkin’s comprehensive approach is necessary for a deeper understanding of the Ukrainian genocide, its specificity, and its traumatic impact on post-genocidal Ukrainian society. Finally, it is to suggest that Lemkin’s analysis of the Ukrainian genocide can be useful in the comparative study of other genocides and in teaching youth how to prevent the seeds of genocide.

1. Lemkin’s Theses—The UN Convention—Historical Documentation

Lemkin conceptualized the genocide of Ukrainians in accordance with the UN Convention and based on his knowledge of Soviet realities. Now, his assertions and nascent analysis can be verified and supplemented by studying the relevant documents.

A. UN Convention: “On the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide”

The preamble recognizes that “at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity,” and the first article states that “genocide… is a crime under international law, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war.” The Holodomor occurred in peacetime, before the adoption of the Convention.

The definition of genocide in Article II: “genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

B. How to Understand the Convention in Relation to the Ukrainian Genocide?

– Genocide is an act, not just a thought;

– The key element of genocide is intent (to destroy), not motive.

N.B. “to destroy” is not a synonym for “to kill” (to deprive of life);

– The target of destruction is the group (1), not the individual members of that group (2);

– Distinguish between crimes: 1) the crime of “genocide” ≠ 2) a crime “against humanity”;

– The recognized victim groups are four: national, ethnic, racial, religious;

– “National” and “ethnic” are not synonyms; national alludes to statehood;

– “As such” refers to the “group” (the subject of existence), not to individuals;

– “Destruction”: 1) by killing (a); 2) by transformation (d, e); 3) by both (b, c);

– Genocide is a process of actions that can vary in duration and intensity.

Stalin’s version of intent: to completely destroy the group by partially killing its members.

C. Raphael Lemkin, “Soviet Genocide in Ukraine,” 1953

Lemkin explains the Ukrainian genocide as a four-pronged attack:

1) “The first blow was aimed at the intelligentsia—the brain of the nation, to paralyze the rest of the body.”

2) “Simultaneously with the attack on the intelligentsia, there was an assault on the Churches, priests, and higher clergy—the ‘soul’ of Ukraine.” [UAOC & UGCC]

3) “The third prong of the Soviet attack was directed at the farmers—the large mass of independent peasants, the repository of Ukraine’s traditions, folklore, and music, its national language and literature, its national spirit.” [N.B.: peasants as part of a national and ethnic group.]

4) “The fourth step in the process was the fragmentation of the Ukrainian people by the settlement of foreigners in Ukraine and the dispersion of Ukrainians.”

“These were the main steps in the systematic destruction of the Ukrainian nation, its gradual absorption into the new Soviet nation.”

For Lemkin, the Ukrainian genocide is “the longest and broadest experiment in Russification—the extermination of the Ukrainian nation.” He adds: “the Communist leaders gave the greatest importance to the Russification of this independent member of their ‘union of republics’ and decided to remake it, adapting it to their model of a single Russian nation.”

D. Lemkin’s Theses Correspond to the UN Convention

“Soviet Genocide in Ukraine” contains all the elements necessary for an indictment of genocide under the 1948 Convention. Lemkin points to the regime’s intent to completely destroy the Ukrainian nation (a national group and an ethnic group) through the physical annihilation of a leading part of its members and the transformation of the rest into members of another group—the “new Soviet nation,” which was, in reality, Russian.

Lemkin emphasizes that the killing began with the national elites of the city and the countryside, who in the past had led Ukraine to a national revival and could have organized a nationwide resistance to the regime’s new policy. Lemkin characterizes the peasants by their national and ethnic traits, not social or economic ones. The Stalinist regime destroyed Ukrainians for national (state-related) motives, not economic or social ones.

Lemkin categorically rejects the attempt by some to “characterize this most brutal manifestation of Soviet atrocity as an economic policy related to the collectivization of wheat fields.”

E. Documentary Evidence of the Genocide of the Ukrainian Ethnos and the Ukrainian Nation

The concepts of ethnicity and nationality are close. The ethnicity of a group is characterized by cultural traits, while nationality is characterized by statehood-related traits. Ethnic groups were factors in both the disintegration of states and their emergence. The year 1917 was an example of both these processes: the disintegration of the tsarist state and the emergence of new states: a separate new Ukrainian state, and a restored old Russian one (the USSR). Moscow’s intent to destroy the revived Ukrainian state and culture, which ultimately led to the genocide of Ukrainians, was caused by the desire to restore the Russian empire. This process is reflected in actions and words.

In January 1918, Lenin sent the Red Army to conquer Ukraine, and in April, Stalin warned V. Zatonsky and the Ukrainian communists: “Enough playing at Government and Republic, it seems that’s enough, it’s time to quit the game.” Ukrainization was intended to root the power of communist Moscow in Ukraine, not to strengthen the Ukrainian ethnos and its statehood. It turned out differently. Poloz, at a meeting of the Politburo of the CC CP(b)U on Ukrainization on May 12, 1926, stated: “The nation has grown to the point where it is time for it—based on economic prerequisites and its cultural level—to enter the arena of state life.” Stalin carefully watched Ukrainization. Ukrainian writers inadvertently reminded him of its danger during a meeting in Moscow in 1929: “A VOICE FROM THE FLOOR: Comrade Stalin, what about the issue of the Kursk, Voronezh provinces, and the Kuban, in the parts where there are Ukrainians. They want to reunite with Ukraine.”

The Ukrainian national revival convinced Stalin that he had to put an end to Ukrainization. In the mid-1920s, the regime began to persecute the Ukrainizers, and a large-scale pogrom of the conscious Ukrainian intelligentsia struck in 1929 with the arrests of academician S. Yefremov and 700 “members” of the SVU. In 1930, the authorities liquidated the UAOC, organized a show trial of the SVU, and killed or exiled the leading strata from the countryside. Linguistic Ukrainization continued until December 1932, when 8 million Ukrainians in the RSFSR lost the right to their language in schools, the press, and local administration.

Having decapitated Ukrainian society, Stalin set about the proletarianization of the peasants, and he suppressed resistance with famine, the power of which he knew well. In 1925, he warned the Central Committee that for the sake of industrialization, grain exports could be increased, but it would come at the cost of an “artificially organized famine with all the ensuing results.” At that time, these results would have been for the workers. In 1932, he knew that his decree on the five ears of grain “is good, and it will soon have its effect.” These “effects”—prodrozkladka (grain requisitioning), the famine of the peasants, and resistance in the CP(b)U: “As soon as things get worse, these elements will not hesitate to open a front inside (and outside) the party, against the party.” Stalin’s liquidation of this Ukrainian “front” would become one of the peaks of the genocide of Ukrainians, which continued until the Great Terror.

2. Lemkin on the Historical Specificity of the Ukrainian Genocide

“Genocide” originated as a legal term, but it has become a valuable concept for historical analysis, national memorialization, and -political discourse. Lemkin was the first jurist to use the word in all three contexts in his essay. His nascent analysis of Stalinist atrocities points to the following manifestations of the specificity of the genocide of Ukrainians:

a. Motives are not part of the legal definition of genocide, but they relate to history and collective memory. Every genocide is the realization by the genocidaires of their motives and includes general and specific crimes. Lemkin correctly asserted that Stalin wanted to “Russify,” that is, to destroy the Ukrainian nation by killing a part of its members. Why only a part? The “leader of the world proletariat” was building a powerful state and needed obedient collective farmers who would grow grain for the country’s industrialization and be formed into “cogs in the great state mechanism,” to carry “socialism” to the world when the capitalist countries began wars among themselves. And so it would happen during the Second World War.

b. Ukrainians became victims of genocide as a national group and as an ethnic group. The first included all citizens of the Ukrainian SSR, the second—ethnic Ukrainians in all republics of the Soviet Union. These groups intertwined. The genocidal authorities applied common and separate measures to them. The task of Holodomor researchers is to include the 8-million-strong ethnic Ukrainian population outside the borders of the Ukrainian SSR in a general, holistic understanding of a single, continuous genocide of Ukrainians.

c. Ukrainians experienced the trauma of Stockholm syndrome not only in their personal experience of the genocide but also as members of national and ethnic groups. Through famine and other repressions, the regime killed some, terrorized others, and forced them into submission. At the national and ethnic level, this meant imposing loyalty to the oppressor state and a favorable perception of its language and culture. The collective syndrome was created by state order. It should be studied not only as a consequence of the genocide but as an integral, designed part of this crime against Ukrainians.

d. The duration of the Ukrainian genocide is incredibly long—the entire 1930s. The regime maintained psychological trauma throughout the war and until the collapse of the Communist Party and the disintegration of the empire. During that time, parents passed on their acquired traumas to their children and grandchildren, and the state cultivated them in the society subordinate to it. Social recovery could only begin and be carried out in an independent Ukraine.

3. The Holodomor: A Comparative Study of Genocides and a Warning for the Future

Lemkin drew attention to the difference between the genocides of Jews and Ukrainians: “It is worth noting that there were no attempts at the complete annihilation of Ukrainians, as the Germans did with the Jews.” Although both totalitarian empires wanted to “destroy completely,” Berlin—the Jews, and Moscow—the Ukrainians, the Hitlerite authorities killed whomever they could, while the Stalinist authorities killed a leading part, and forcibly transformed the rest into members of a new, Russified, “Soviet nation.” There were well-known ideological justifications for this, state-building imperatives, and favorable circumstances: “The Ukrainian nation is too numerous to be easily exterminated. However, its religious, intellectual, and political leadership—the select and decisive parts of its nation—are quite small, so they are easily liquidated.”

The features of the genocide of Ukrainians were typical of the genocides of conquered and colonized countries. The study of the Holodomor can help to better understand genocidal measures in colonial and post-colonial countries of the two Americas, Africa, and Asia. Especially where the “destruction” of groups aimed to kill part of the population and reshape the rest into other groups, such as the destruction of existing states in the two Americas by European colonizers, or the assimilation of indigenous populations in “residential schools” in Canada, and so on.

The main goal of the United Nations Convention on Genocide was, and still is, to prevent these crimes in the future. Unfortunately, 70 years after the law was passed, the world still suffers from this scourge. Signs of genocidal actions can now be seen in Asia, in Crimea, in the Donbas. Genocide is a crime against a group, but it destroys human rights, and its victims are individuals.

To eliminate the danger of genocides, it is necessary to teach new generations to recognize the seeds and manifestations of these crimes in everyday life. Therefore, it is essential to prepare appropriate programs and educational material about the Holodomor, explaining the specifics of the genocide of Ukrainians. Such material is necessary, first and foremost, for Ukrainian schools, but also for schools in other countries.

In Lieu of a Conclusion

Lemkin wrote a speech for a political demonstration that condemned the Kremlin for the artificial Great Famine and for the continuation of the criminal occupation of Ukraine. In his speech, he gave a comprehensive explanation of the genocide of Ukrainians, but this understanding was nascent, incomplete, and with inaccuracies. Therefore, the task of Ukrainian scholarship is to correct and supplement Lemkin’s theses, and finally to give Ukraine and the world a complete and truthful understanding of the Holodomor.