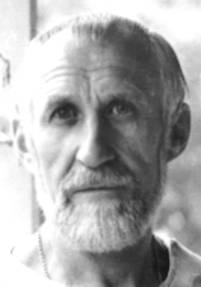

KALYNCHENKO, VITALIY VASYLYOVYCH. Born in 1938. Ukrainian. In 1966, imprisoned for 10 years for attempting to illegally cross the border. For his dissident activities, he was once again sentenced in 1980 to 10 years of imprisonment. Rehabilitated in 1991. Now lives in the USA.

Vitaliy Kalynychenko was born in the district center of Vasylkivka, Dnipropetrovsk oblast, to a family of teachers. His father, Vasyl Petrovych, taught Russian language and literature, and his mother, Hanna Havrylivna, taught history. His father died of tuberculosis when Vitaliy was not yet four months old. Hanna Havrylivna had to raise her son and daughter on her own. They survived the German occupation; under its oppression, the teacher refused to work at the school. After the war, she was appointed deputy head, and then head of the Vasylkivka seven-year school. In 1947, Hanna Havrylivna married for the second time. Her husband was Arsentiy Semenovych Tkach, the chairman of a collective farm in Vasylkivka. In 1954, Vitaliy graduated from the 10th grade; his dream was to attend a naval academy. But they only accepted applicants from the age of 17. So the young man forged his birth certificate, adding a year to his age, and became a cadet at the Riga Naval Academy.

But the military discipline, the strict regulation of every step of the cadets, proved unbearable for the young man who had grown up coddled by his family. Conflicts began—violations of the dress code, formation, and so on. He had to leave the academy.

Vitaliy was conscripted into the army. He served as a rangefinder in a coastal battery. Here, his service went well. Seaman Kalynychenko, as noted in his character reference, “having good theoretical knowledge, mastered the equipment well himself, and also helped his comrades, enjoying deserved respect among them”1.

After being discharged into the reserves, Vitaliy decided to continue his education, but this time in a civilian profession. For various reasons, he had to change several cities (Kharkiv, Leningrad) and institutes, eventually transferring to the Kyiv Institute of National Economy (KING), from which he graduated in 1964.

A restless nature and a sharp reaction to any actions of others that seemed offensive to him forced him to change jobs. Eventually, he found himself back in Leningrad.

By this time, the thought that it was impossible for him to live in the Soviet Union had been maturing for several years. Here, for a free person, there was no real freedom, no opportunities to apply one’s abilities. Vitaliy decided to go abroad.

In the conditions of that time, this could only be done illegally. Although the USSR had signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, according to which anyone could freely choose their place of residence, this was done, as they say, for show. Neither the Communist Party nor the government intended to abide by the Declaration. And how could one raise the issue of free exit from a country where a song with the words “I know of no other country where a man breathes so freely!” was practically an anthem?

So, citizens were supposed to “breathe freely,” and those who did not wish to were sent to appropriate places, so they would know where it was easier to breathe. The USSR was cut off from the world by a true “Iron Curtain,” which could only be crossed by risking life and liberty.

In 1964, Vitaliy Kalynychenko began to prepare for his escape; in particular, through foreign students at KING, he tried to contact the US embassy to obtain political asylum and purchased equipment for illegally crossing the border. His plans became known to the KGB, and Vitaliy was arrested. After holding him in prison for some time, scaring him, and warning him, they released him.

But he stood his ground. In the summer of 1966, he made an attempt to cross the Soviet-Finnish border. He wandered along it for 10 days until he was caught by border guards. He was tried in Murmansk. The judges, trying to understand what had led Kalynychenko to the idea of escape, concluded that, already while studying at the institute, he had behaved improperly, was fascinated by the philosophy of existentialism, sympathized with the Beatniks (there was such a youth fad at the time), and for this reason, the idea of escaping abroad had formed in his mind. But one does not joke with the Soviet state in this way. And the court qualified his act as treason to the Motherland in the form of an attempt to escape abroad, sentencing him to 10 years of imprisonment in a strict-regime camp.

Vitaliy Kalynychenko spent his time there, as they say, from bell to bell. He refused to reconcile with the camp regime, resisting it as he could, for which he received punishments. Case No. P-26123 contains a “Certificate of Violations and Punishments” of prisoner Kalynychenko, V. V., among them—violation of the dress code, reading a book during work, but most of all such active forms of protest as refusal to go to work. The punishments were varied:

a conversation with the authorities, probably not in the most pleasant tone, a reprimand, a warning, and the most severe—confinement in a punishment cell. Vitaliy received 6 days for reading a book in the work zone, and 10 and twice 15 days for refusing to work2.

But he was not re-educated, and upon his release, he received a very negative character reference, which immediately had repercussions when he arrived in Vasylkivka.

As someone who had not embarked on the path of correction, he was placed under administrative surveillance by order of the prosecutor of the Vasylkivka district. This meant that V. Kalynychenko could not leave Vasylkivka even for a short time without the permission of the police, he was not allowed to leave his home from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m., and was forbidden from visiting restaurants and cafes3.

On the prosecutor's order of April 8, 1976, regarding administrative surveillance, he wrote: “Acknowledged. Shame on the Soviet authorities! This is not release from the camp.”

Of course, it was difficult for a person under surveillance to find a job. He was hired as a worker at a hemp-spinning factory. The factory director immediately received a directive from the district police demanding to be informed of any instances of Kalynychenko violating labor discipline, as well as any positive facts regarding his attitude towards work and participation in public life, which should testify to his re-education and influence the decision to terminate the surveillance4.

Viewing the police's actions as compromising, Vitaliy Vasyliovych left the hemp-spinning factory.

Evidently, there were not many economists with higher education in Vasylkivka, so V. Kalynychenko managed to get a job as an accountant at the district department of “Silhosptekhnika” [Agricultural Equipment]. The days of service dragged on under conditions of constant surveillance and restrictions. Almost the same cage as before, only larger.

Unwilling to tolerate this situation, V. Kalynychenko wrote a complaint to the prosecutor of the Ukrainian SSR, in which he reported that he had served his sentence for what the state considered a crime, although from a universal human standpoint it was not a crime. He stated that when he wanted to leave the USSR, he was guided in his actions by Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—the ability of everyone to freely leave any country, including their own.

But the government of the Ukrainian SSR, having declared itself practically the main drafter of the Declaration, does not allow leaving the country, and individuals who attempt to do so are declared traitors to the Motherland and sentenced to 10–15 years, or executed5.

Of course, the complaint remained unanswered, or rather, the answer was: the term of administrative surveillance was extended for another 6 months.

Vitaliy Kalynychenko tried to somehow stir up the stagnant swamp in which he found himself, telling his work colleagues about the glorious past of Ukraine, about events in the world, but not from the official media, but by retelling reports from “Voice of America” and “Radio Liberty,” which caused indescribable horror among his co-workers. And they could be understood. It was extremely difficult for an educated person to find intellectual work in Vasylkivka, as in any small town, but it was easy to lose it—a rank-and-file employee was absolutely defenseless against even the slightest boss. And God forbid, if the authorities found out that you listened to “Voice” or “Liberty,” even not directly, but in someone else’s retelling, and did not run to report it where you should, you could expect to be fired, as they said before the revolution, “with a wolf's ticket,” and no trade unions, no court could help.

Therefore, among the frightened people, Kalynychenko's conversations not only had no success but, on the contrary, provoked an extremely negative reaction. On March 31, 1977, a meeting of representatives of the collective was held at “Silhosptekhnika.” The speakers subjected V. Kalynychenko to severe criticism and condemned his behavior and views: imposing views hostile to socialism and Soviet reality on those around him, and extremely nationalist judgments. The meeting demanded that he cease distributing ideologically harmful and slanderous fabrications in the collective and warned that if such activities resumed, they would officially inform the competent authorities6.

But there was no need to inform the competent authorities. On March 5, V. Kalynychenko had already been summoned to the regional KGB department and given an official warning, based on the corresponding Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of December 25, 19727.

They tried to guide Kalynychenko onto the “true path.” Representatives of the administration and the public repeatedly had conversations with him with the leitmotif: “What do you want? Settle down and let us live in peace.” But he did not settle down. On October 10, 1977, he addressed a “Statement” to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, in which he exposed the false assurances of the leadership of the CPSU and the government that the Helsinki Accords were supposedly being implemented in the USSR, in particular, he presented facts of the imprisonment of dissidents in camps and psychiatric hospitals, thus proving the existence of political persecution. He indicated that in protest, he was renouncing his Soviet citizenship and declaring a ten-day hunger strike8.

Kalynychenko wrote a “Statement” to the Vasylkivka doctors, which, in his opinion, was supposed to prevent his confinement in a “psykushka”9.

From broadcasts on Radio Liberty, Kalynychenko learned about the creation of the “Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords” (Hereafter—the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, UHG. – Author). Its founders were Levko Lukianenko, Oksana Meshko, Oles Berdnyk, and others. Regarding the creation of the group as a deeply patriotic act, Vitaliy Vasyliovych addressed an “Open Letter” to Levko Lukianenko with a request to recommend him for membership in the Group.

At that time, the members of the UHG had just addressed the Belgrade Meeting of 35 states, which had convened to review the implementation of the Helsinki Accords. Kalynychenko asked that his signature also be on the address. The text of the document with Vitaliy Kalynychenko’s signature reached the West and was broadcast on “Voice of America” and “Radio Liberty,” which caused a new fit of anger from the authorities. At the instigation from above, the collective of the Vasylkivka “Silhosptekhnika” appealed to the KGB with a request to get rid of such an employee. But there was not yet a normal, sufficiently strong pretext. They decided to wait.

The years 1978 and 1979 passed in a struggle of one who disagreed with the System, a struggle that was unequal and exhausting, in which the authorities used any means, not even shying away from the perusal of personal mail, because a letter in which Kalynychenko outlined his political views ended up in the KGB and became another stone in the foundation of the accusations. They continued to “educate” him. On August 17, 1979, a conversation was held by the secretary of the Vasylkivka district party committee “himself,” and on October 3—by the head of the district department of internal affairs. But all in vain. The stubborn Kalynychenko did not draw any conclusions, did not repent, listened to “Voice of America” and “Radio Liberty,” retold the content of the broadcasts, wrote “Statements,” and supported the actions of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group.

The authorities’ patience ran out. On November 28, 1979, the regional prosecutor approved a resolution to apply a preventive measure against Kalynychenko, V. V., as one who, after release from a correctional labor institution, did not embark on the path of re-education but, on the contrary, on the basis of anti-Soviet nationalist convictions, with the aim of undermining and weakening the Soviet government, systematically produced and reproduced (with the help of a ballpoint pen and carbon paper. – Author) documents containing slander against the Soviet state and social system, thereby committing a crime under Article 62, Part 2 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR9.

The measure was well-known and quite radical—detention. Long, exhausting interrogations began. The entire second volume of the seven-volume case No. P-26123 was filled with protocols. Although, in fact, there was no need to search for anything. The investigators ascertained whether Kalynychenko admitted his authorship of the “Statements” and “Complaints” to the higher bodies of Soviet power. He admitted it. But just in case, they conducted graphological examinations, which confirmed that the “Statements” were written in Kalynychenko's hand.

A rather prominent place in the interrogation protocols is occupied by discussions between the subject and the investigator regarding the rightness or wrongness of V. Kalynychenko. The KGB officer argued to Vitaliy Vasyliovych that the documents he produced were slanderous, justifying the hostile activities of persons sent to camps for committing particularly dangerous state crimes—L. Lukianenko, M. Rudenko, O. Tykhyi, and others, and contained fabrications that political persecution and a lack of rights and freedoms existed in the USSR10. And the persecuted man proved to him the opposite, that there were no political rights and freedoms in the USSR, that he wrote the pure truth in his statements, and everything he indicated fully corresponded to Soviet reality.

The investigation meticulously acquainted itself with Kalynychenko’s biography. Firstly, probably to show diligent work, a deep study of the subject, and secondly, to prove that Kalynychenko was a staunch opponent of Soviet power, that his anti-Soviet sentiments were not accidental and had deep roots.

From November 20, 1979, to April 2, 1980, 37 interrogations took place. The KGB bodies questioned everyone, or almost everyone, who communicated with him. There were not few, but not many—82 people—and their testimonies made up over 300 pages of the third volume of case P-26132. Most of the witnesses were residents of Vasylkivka. Their testimonies contained unanimous condemnation and generally negative assessments of V. V. Kalynychenko's personality.

But there were other opinions. In this regard, it is interesting to cite the words of M. V. Braun, who was serving a sentence for political reasons and was in the same camp as Vitaliy Vasyliovych. A native of Leningrad, a philologist by education, and a bibliographer by profession, he was working as a stoker at the time of his interrogation in February 1980. Braun testified that he regarded Kalynychenko as a capable person, a profound expert on Slavic languages, history, and ethnography of Ukraine12. Another characterization. Its author is A. K. Zdorovyi, an engineer from Makiivka. He believed that V. V. Kalynychenko was a man of principle, attentive to those who were suffering. He reacted sharply to

injustice or violation of the law regarding himself or other people. Zdorovyi was certain that Kalynychenko had not engaged in anti-Soviet activities13.

Of course, such testimonies were not taken into account, but the outrage of the Vasylkivka workers was recorded by the investigation with satisfaction.

On April 21, 1980, the “Indictment” was ready. It stated that, having served his sentence, Kalynychenko, V. V., did not embark on the path of correction, remained in positions hostile to the Soviet government, maintained ties with renegades like Lukianenko, Sokulskyi, and others, incorrectly perceived Soviet reality, slandered the state and social system, and the national policy of the Communist Party and the Soviet state, and therefore was subject to trial14.

On the eve of the trial, V. V. Kalynychenko submitted a request that the trial be open and held in Vasylkivka. He wanted to use another opportunity to share his views with people. His second wish was granted—the court session was held in Vasylkivka. As for the first, the authorities made sure to select attendees with appropriate moods and views.

The trial proceeded according to all the rules—with a prosecutor, a defender, and the summoning of witnesses. But still, the procedure was grossly violated. More than enough witnesses were called—23. The defendant demanded that defense witnesses also be called, naming L. Lukianenko, I. Sokulskyi, O. Meshko, M. Braun, and others. But he was refused this—apparently, the judges decided not to give themselves extra trouble by providing a platform to V. Kalynychenko's like-minded associates.

Receiving the floor at the beginning of the judicial investigation, the defendant stated that he was a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, a representative of the Ukrainian nation, and also expressed a protest against his arrest, reminding that he had been imprisoned not for any specific crimes, but for dissent, for his convictions. All his thoughts were set out in the “Statements” and fully corresponded to Soviet reality. He sent these documents abroad so that they would become common knowledge, so that the whole world would know about the violation of human rights in the USSR, about how the government deceives people.15

An interesting dialogue took place between the presiding judge and the defendant. The former asked how the government's deception of the people was manifested. V. Kalynychenko replied that the party and the government had promised to build the material and technical basis of communism by 1980, but had not done so. The judge, in all seriousness, became interested: “And what, hasn’t it been built?”16

The prosecutor considered V. Kalynychenko's guilt to be fully proven, although he could hardly prove in what it specifically manifested, and demanded 10 years of imprisonment. The lawyer asked to mitigate the sentence.

In his final statement, V. Kalynychenko did not renounce his views, asserting that he believed in the rightness of his cause, that every person has the right to speak freely, to enjoy freedom of speech, to say what they think. And how can one be sentenced to 10 years in prison for thoughts? He did not repent, did not ask for a lighter sentence, as he said, “your false mercy”17.

And the verdict was corresponding, determined in advance—10 years in a special-regime colony18.

V. V. Kalynychenko appealed to the Supreme Court with a cassation complaint, in which he showed that even after the trial, after the verdict was announced, the minutes of the court session were falsified. The presiding judge had worked on it so that some things disappeared and some appeared, of course, in the key desired by the “clients.” The prisoner resolutely demanded a review of the verdict19. But the complaint remained without consequence.

Vitaliy Vasyliovych Kalynychenko served 8 years, was released in 1988, and rehabilitated in 199120. He now lives in the United States of America.

NOTES

1 State Archive of the SBU. Fund of the Dnipropetrovsk oblast administration. Case 26132. Sheet 223.

2 Ibid. Vol. 5. Sheets 239-240.

3 Ibid. Vol. 6. Sheet 58.

4 Ibid. Vol. 6. Sheet 59.

5 Ibid. Vol. 1. Sheet 26.

6 Ibid. Vol. 1. Sheet 97.

7 Ibid. Vol. 1. Sheet 94.

8 Ibid. Vol. 1. Sheet 99.

9 Ibid. Vol. 1. Sheet 214.

10 Ibid. Vol. 2. Sheet 63.

11 Ibid. Vol. 3. Sheets 40, 64.

12 Ibid. Vol. 3. Sheet 24.

13 Ibid. Vol. 3. Sheet 97.

14 Ibid. Vol. 6. Sheets 142-193.

15 Ibid. Vol. 7. Sheets 10-13.

16 Ibid. Vol. 7. Sheet 23.

17 Ibid. Vol. 7. Sheets 98-99.

18 Ibid. Vol. 7. Sheet 139.

19 Ibid. Vol. 7. Sheets 166, 172.

20 Ibid. Vol. 2. Sheet 206.

REVIVED MEMORY. A Book of Essays. – Dnipropetrovsk: Scientific-Editorial Center of the Regional Editorial Board for the Preparation and Publication of the Thematic Series “Rehabilitated by History.” Vol. 1. 1999. – pp. 553 – 560.