APPEAL TO THE PEOPLE

DEAR FRIENDS AND COMRADES!

People who have found in themselves the strength and courage to speak out against the hateful dictatorial policy of the party and the current rulers are addressing your mind and heart.

FRIENDS!

Look at the world with seeing eyes, cast off the veil of deceitful words with which a handful of communists who have seized power entangle you with the help of newspapers and radio.

Don’t you smile ironically when reading newspapers or listening to the radio, are you not outraged by the vile lies and duplicity that permeate every phrase, every speech?

They shout about freedom and democracy, but it is freedom in a cage, and the rule of the people has been stifled and replaced by the rule of the party elite.

They shout about the wealth of the people, about the rise in their well-being, but the people, meanwhile, are poorer than before the revolution.

A worker cannot feed himself on his meager salary, let alone a family.

And how does a peasant live? The land, watered with the sweat of his grandfathers and fathers, was taken from him. Driven into a collective farm, having no interest, no attachment to the land, he leaves for the city so as not to see the rural misery.

But what will he find there?

The same lack of rights, poverty, and downtrodden existence. Shortages of food, shoes, and clothing, high prices and meager earnings—these are all the achievements of over forty years, during which the people have seen nothing but wars, ruin, hunger, tyranny, and deceit.

The foolish and dictatorial policy of the communist party, both within and outside the state, is leading the world to a schism, to an unbridled arms race with the expenditure of countless public funds and brings turmoil and fear for the future into the hearts of people.

FRIENDS AND COMRADES!

We desire brotherhood, true brotherhood, and not enmity between the peoples of all countries of the world!

Enough of splitting the world into two so-called “camps”!

Down with the fascist dictatorship of the party!

We need genuine freedom of views, speech, and the press!

We stand for the recognition of religion and the church by the state!

Down with atheistic propaganda!

Long live the true freedom of the people!

Union for the Liberation of the People (SOBOZON)

A leaflet with this text was composed in 1958 by a graduate of the Odesa Theatrical Art and Technical School and a lighting technician at the M. Kropyvnytsky Kirovohrad Ukrainian Music and Drama Theater, Oleksa Riznykiv (b. Feb. 24, 1937), and his friend, a master confectioner at a food processing plant in the city of Pervomaisk, Mykolaiv Oblast, Volodymyr Barsukivsky (b. March 13, 1938). The text was written on behalf of an organization that Riznykiv and Barsukivsky intended to create—the “Union for the Liberation of the People.”

Having printed about 40-50 copies of the “Appeal to the People,” the young men pasted them, placed them on stands, and distributed the leaflets in crowded places—Barsukivsky in Odesa, and Riznykiv in Kirovohrad. For greater resonance, this was done on the “October holidays,” November 7–8, 1958.

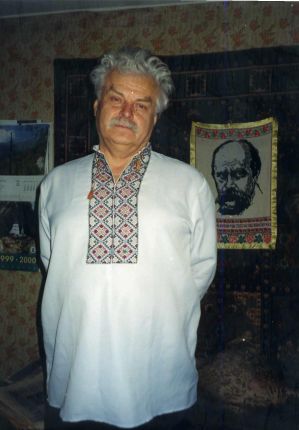

Oleksa Riznykiv

Later, Oleksa Riznykiv was conscripted into the army, served in the navy in Sevastopol, and published poems in the Sevastopol military naval newspaper “Vympel.” Almost 11 months later, the investigative department of the Odesa Oblast KGB opened a criminal case against Riznykiv and Barsukivsky, and the next day, on October 1, 1959, searches were conducted, during which a folder with Riznykiv's poems and stories was seized (some of which were later deemed slanderous), and the young men were arrested.

Volodymyr Barsukivsky

The leaflet itself, which became the reason for the arrest, was written in Russian and did not contain national slogans. It was directed against the “dictatorial policy of the communist party,” which had led the people to impoverishment and lawlessness, against lies and duplicity, against the arms race. But later, during the investigation and in the camp, Oleksa Riznykiv's views changed, as the poet would later say in an interview with Vasyl Ovsienko (b. April 8, 1949), “that thing I told you about begins—how I was spiritually reborn, how I became a Ukrainian.” Oleksa read Ukrainian books, in particular, I. Franko's “Prison Sonnets” in Russian translations. And when on January 1, 1960, Riznykiv and Barsukivsky’s accomplices were brought together in one cell in the Odesa prison, they began to speak Ukrainian, recorded and learned Ukrainian songs from the radio. On the eve of the trial, which took place in February 1960, Oleksa wrote an ambiguous poem about how he had disassembled and cleaned the mechanism and parts of his life, like a machine, and instead of a final word, he read the poem at the trial: “I’ve cleaned everything, I’ve greased everything, / With the tear of trial, of repentance, / I’ve reviewed with my soul’s eye / And here they are before me: / From the same muscles and skin, / From the same eyes, from the same hands / I must assemble another life. / And I swear that I will assemble it!”. In reality, he was talking about a new life—the life of a Ukrainian.

On February 19, 1960, the Military Tribunal of the Odesa Military District found Riznykiv and Barsukivsky guilty of conducting “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” and sentenced both to 1.5 years. While serving his sentence in camp ZhKh-385/11 in the settlement of Yavas, Mordovia, Oleksa befriended Serhiy Babych (Dec. 13, 1939–Aug. 24, 2016), the poet Sashko Hryhorenko (Feb. 22, 1938–Aug. 19, 1962), communicated with the insurgents serving 25-year sentences, practiced yoga, and wrote many poems.

After his release on April 1, 1961, he worked as an electrician, was a contributor to newspapers, a school secretary, a Ukrainian language teacher at an evening school, etc. From 1962 to 1968, he studied by correspondence at the Faculty of Philology of Odesa University along with Sviatoslav Karavansky (Dec. 24, 1920–Dec. 17, 2016), who introduced him to his wife, Nina Strokata (Jan. 31, 1926–Aug. 2, 1998). On Karavansky's initiative (before his arrest on Nov. 13, 1965), Odesans, including Riznykiv, collected books for Ukrainians in Kuban and sent letters about the Russification of schools and universities to newspapers, the Ministry of Education, and the prosecutor.

On October 11, 1971, Oleksa was arrested for the second time. The trial of him, Nina Strokata, and Oleksa Prytyka (b. 1932) took place in May 1972. It was the first trial in the series of repressions against the intelligentsia in 1972. On charges of conducting anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda (Part 1, Art. 62 of the UkrSSR Criminal Code), Riznykiv was sentenced to 5.5 years in a strict-regime labor camp. N. Strokata received 4 years, O. Prytyka 2 years.

Nina Strokata

The poet served his second term in camp VS-389/36 in the village of Kuchino, Perm Oblast. While there, Oleksa Riznykiv wrote poems in notebooks every day, in particular, as he recalls, “for some reason, in prison, in a cell, in a concentration camp, one writes sonnets.” In total, during his “time served,” the dissident wrote 1700 of them, and most of them have survived, except for the first 75, which were in two notebooks confiscated by the KGB.

The canonical sonnet is characterized by having four or five rhymes. But, as Riznykiv later wrote, at the time it seemed to him that so many rhymes were “an inadmissible luxury, forbidden to an imprisoned poet, like, for example, a dinner from the Odesa restaurants ‘Ukraina’ or ‘Kyiv’! It’s like a guitar with five or seven strings—a luxury, a violin with four—a luxury! And so I, having a certain natural habit of limiting myself even more than someone else had limited me, decided to consciously break those two or three extra ‘strings,’ leaving myself with only two. I have two wooden beds in my cell, two crossed bars in the window—vertical and horizontal. I can only walk in two directions—forward and back… Two hands, two feet, two eyes… And the investigation only sees two colors in my activities, in my life—black and white. No nuances.” Therefore, the poet began to write sonnets with two rhymes, calling them his two-stringed lyre. Here are a couple of verses that reveal this image:

On my lyre, there are two strings,

for the rest were torn away by the wind.

And now in my hands, I hold a splinter…

To abandon it? God forbid!

It has two strings. Is that so little?

Like a pair of hands, like a pair of legs,

like a pair of strong, supple wings,

that nature gifted!

Still, from them will rise to the heavens

that which was swaddled beneath the heart,

that which leads me and intoxicates.

Do not fall silent, two-stringed lyre!

Purer, clearer, start to ring, —

for you have not yet lost everything!

***

I take my two-stringed lyre…

one of its strings is mournful,

the other—cheerful, playful.

Which one do I touch first?

If the mournful one—it's no wonder,

for sorrow all around my soul,

like a borer on a tree’s bark,

gnaws with a wistful ache.

But, continuing the play,

I pluck with a timid finger

the more cheerful of the strings,

then—more often, then—a shower

of mixed chords I take!

for when I play, I am happy.

After serving his second term, Riznykiv was forcibly settled in the city of Pervomaisk, near his mother and father. For two years, the poet worked as an electrician in a maternity hospital, then got a job in a boarding school for children with special needs, where he worked as a caregiver for 10 years. In the late 1980s, Oleksa became actively involved in public life, particularly in the creation of the People's Movement of Ukraine and the Taras Shevchenko Ukrainian Language Society (“Prosvita”). After moving to Odesa in 1996, he was elected a member of the leadership of the All-Ukrainian Vasyl Stus “Memorial” Society, appointed chairman of the regional commission on rehabilitation issues, and elected head of the Odesa regional “Prosvita,” among other roles. In 1998, Riznykiv began to lead the “Hart” literary studio at the House of Children's and Youth's Creativity.

Oleksa Riznykiv

Since 1987, Oleksa began to be published in republican and local press. In 1990, he was admitted to the Union of Writers of Ukraine. In total, Oleksa Riznykiv has published two dozen books of his poetry and prose. Among them are “Odnorimky. Slovnyk omonimiv” [“Single-Rhymes. A Dictionary of Homonyms”], “Skladivnytsia ukraïnsʹkoï movy. 9620 skladiv nashoï movy” [“The Treasury of the Ukrainian Language. 9620 Syllables of Our Language”], “Spadshchyna tysiacholit’. Chym ukraïns’ka mova bahatsha za inshi?” [“The Heritage of Millennia. How is the Ukrainian Language Richer Than Others?”], and two books of memoirs about Nina Strokata. From 2004 to 2005, he hosted his own program on UT-1, “Nasha mova” [“Our Language”]. He is the recipient of many literary awards. He is married, has a daughter, Yaroslava, and a granddaughter, Yulia. He lives in Odesa.