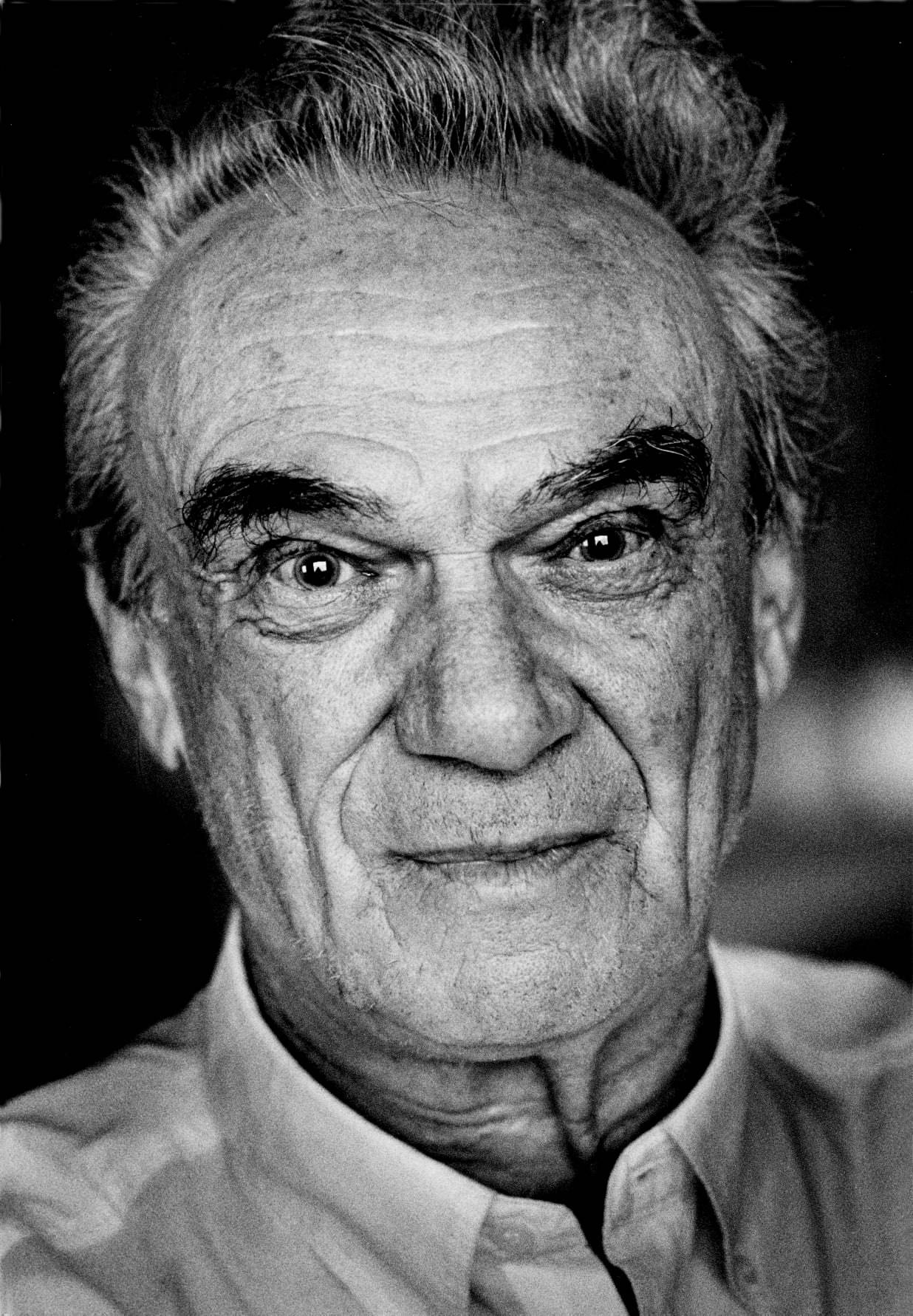

On the night of November 25, Mikhail Ruvimovich Kheyfets—writer, historian, and dissident—died in Jerusalem at the age of 85.

Mikhail Kheyfets was born on January 18, 1934, in Leningrad to the family of an electrician. In 1955, he graduated from the literature faculty of the Herzen Leningrad Pedagogical Institute. He worked as a schoolteacher while simultaneously studying in a correspondence postgraduate program, from which he was dismissed for “unorthodox views.” He began to write fiction. From the mid-1960s, he was a professional writer: he wrote historical novels, literary-critical articles, scripts for documentary films, and ghostwrote generals' memoirs. He was published in magazines such as “Koster,” “Zvezda,” “Voprosy Literatury,” “Avrora,” and others.

In 1973, Kheyfets wrote the preface to a 5-volume collection of Joseph Brodsky's works, prepared by the Leningrad writer Vladimir Maramzin for samizdat. Mikhail gave this preface (“Joseph Brodsky and Our Generation”) for review to the literary scholar Efim Etkind and the science fiction writer Boris Strugatsky. Later, at his trial, writing the preface and its “dissemination” became the main count in the charges against Kheyfets.

On April 22, 1974, Kheyfets was arrested. The preface was deemed “slanderous,” with particular emphasis on the writer's harsh condemnation of the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. He was also accused of possessing literary and human rights samizdat (“Chronicle of Current Events”), and articles and letters by Petro Hryhorenko, Aleksei Kosterin, and Andrei Amalrik. This case became an example of a “purely literary KGB case,” where a writer was tried for writing an article about literature.

On September 13, 1974, Kheyfets was sentenced by the Leningrad City Court under Article 70, Part 1 of the RSFSR Criminal Code (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”) to four years of imprisonment in a strict-regime colony and two years of exile. He was promised a pardon in exchange for “repentance,” but Kheyfets refused.

In his final statement, Kheyfets said he wanted to write a book about the camp. He later wrote: “...I was given a pass and a creative assignment to a completely forbidden-secret point of the USSR—I considered myself a special correspondent here. I was not supposed—or so it seemed to me—to influence events in the zone, but, on the contrary, to observe and study them in their natural environment, to delve into and investigate the natural logic of behavior of those whose existence in the zone was not accidental, like mine, but professional—the dissidents and the administration.”

He served his term in the Mordovian political camps (Dubravlag)—ZhKh-385/17A (Ozyorny settlement) and No. 19 (Lesnoy settlement). He became close with Armenian and Ukrainian political prisoners (Paruyr Hayrikyan, Zoryan Popadiuk, Vasyl Stus, Viacheslav Chornovil, Mykola Rudenko), participated in solidarity hunger strikes with them, and in the struggle for the status of a political prisoner.

On April 21, 1977, Kheyfets, along with other political prisoners, declared a de facto transition to the status of a political prisoner and began a 100-day phased hunger strike for the recognition of this status by the camp administration. For this, he was thrown into a punishment cell, where he spent a total of forty days. In June, he composed the “Report on the Struggle of Political Prisoners in the Mordovian Camps for the Status of a Political Prisoner,” the text of which was secretly smuggled out and published abroad. He wrote and smuggled out several books: an autobiographical work “Place and Time” about life in the camp and the struggle of political prisoners for their rights; and “Russian Field,” a collection of three interviews with political prisoners.

In April 1978, having served his camp term, Kheyfets was transported to exile in the town of Yermak, Pavlodar Oblast, Kazakhstan. He worked as a teacher in a secondary school, then as a methodologist in a training center. He continued his human rights activities there. On November 4, 1978, he sent a statement to KGB Chairman Yu. Andropov requesting intervention in the case of the long-term political prisoner Kostyantyn Skrypchuk. He fought for the right of Petro Saranchuk to leave the USSR. In early 1979, he sent several protests against the trial in Ukraine of Vasyl Ovsiienko. He later described his journey to exile and life there in the book “Journey from Dubravlag to Yermak.”

In January 1980, Kheyfets was released from exile and emigrated to Israel in March. He was published in Russian and Ukrainian émigré periodicals: in the journals “Kontinent,” “Kolo,” “Posev,” “Tribuna,” “Suchasnist,” as well as in the Israeli Russian-language journal “Vremya i my.”

From 1982 to 1990, he worked as a research fellow at the Center for the Study of East European Jewry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He then dedicated himself entirely to journalism. He was a member of the editorial boards of the journals “22,” “Vzglyad na Izrail,” and “Narod i zemlya.”

A number of Kheyfets’s books were published by the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. These include the three-volume “Selected Works,” which is available in the KHPG online library and which includes the works “Place and Time,” “Journey from Dubravlag to Yermak,” “Ukrainian Silhouettes,” and “Secretary War Prisoner,” as well as “The Story of One Political Crime” and “The Book of a Happy Man.” “Ukrainian Silhouettes” was also translated and published in Ukrainian. This collection contains essays about Kheyfets’s fellow camp inmates, mostly figures of the national liberation movement—Vasyl Stus, Viacheslav Chornovil, Mykola Rudenko, Zoryan Popadiuk, Vasyl Ovsiienko; about insurgents Petro Saranchuk, Mykola Konchakivsky, Mykhailo Zhurakivsky, Kostya Skrypchuk, Volodymyr Kaznovsky—in the chapter “The Holy Old Men of Ukraine”; and about Dmytro Kvetsko, Mykola Hamula, Mykola Hutsul, Fedir Dron—in the chapter “Bandera's Sons.”