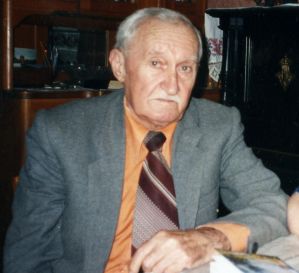

An Interview with Ivan Yukhymovych KOVALENKO

and Iryna Pavlivna KOVALENKO

(With corrections by the Kovalenkos. Edited text)

V.V. Ovsienko: On September 12, 1999, in Boyarka, near Kyiv, at the home of Ivan Yukhymovych Kovalenko at 36 Chubarya Street, Vasyl Ovsienko, coordinator of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group program, is recording his autobiographical narrative. Also participating are his wife, Iryna Pavlivna Kovalenko (née Pustosmikh), and Nina Borysivna Kotlyarevska.

Ivan Yukhymovych Kovalenko: I, Ivan Yukhymovych Kovalenko, was born a dissident. I was born in the small, remote village of Letsky, near Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi. It was in 1918, on December 31. Our family was large: four children. My father was an outstanding farmer, famous throughout the village because he knew how to get a good harvest from a small plot of land. That’s why, when they were dividing the land after the revolution, he didn’t rush to get a lot of it—he could have, because they were giving out one and a half hectares per person. But he took only three and a half hectares for the whole family, as if foreseeing the future dekulakization. But from those four hectares, with his skillful farming, he would gather a harvest so large that it was enough for our family, and he even had extra to take to market and sell.

I received my education later, in Pereiaslav. But before that, I lived through the Holodomor. In our village, only half the people died out, whereas other villages died out almost completely, or two-thirds of them did. Why? Because a commune called “Mayak Batrakiv” (Lighthouse of the Farmhands) was organized in the village. My father, realizing he couldn’t escape this disaster, joined the commune. There, they gave a ration per person: one glass of millet a day. But even that was enough to somehow survive.

Having survived the Holodomor, even though I remained a member of this commune, I had to flee the village. My mother did the same, because my father, although considered a poor peasant (with four and a half hectares), was still subjected to various forms of repression. They finally got to him. Although dozens of decent and good farmers were deported from the villages—deported to Siberia, deported God knows where—he managed to avoid it. Why? Because in the commune, he started working as a plowman. And that commune, in the beginning, lived up to the hopes of the commune-Bolsheviks: it produced very good harvests because the chairman was elected from the local peasants, and there were some decent people among them.

But later, when they started sending in the “twenty-five-thousanders,” my father's life got much worse. He was, of course, kicked out of this TOZ. And not only that, they found fault with him: he and another villager, one of only two or three left in the whole village, were raising a pig fifty-fifty. They found out about it, and for that, they demolished his house, demolished the entire homestead, but the only thing they didn't do was expel him from the village. This was after 1930.

I remained a member of the commune and was supposed to work in it, from the age of 7 to 16. But since there was no school in the village, except for two or three primary grades, my mother fled to Pereiaslav and enrolled me in School No. 1. It was a very good school. It was built by Prince Gorchakov, a great philanthropist. He equipped it with all the best teaching aids. There was even an astronomical observatory.

I was a good student, but even then I showed my defiance. After being a Little Octobrist for only two or three months, I refused to join the Pioneers, and I couldn't even think of joining the Komsomol. And so I lived my whole life without being a Komsomol member, a Pioneer, or a Party member.

I got my education while working in the commune. I worked in the summer and studied in the winter. But even then, I had “dissident” sentiments. I was expelled from school three times. Once, I was out of school for a whole six months because when they were extorting three rubles from each student to help striking workers in Austria, I said: “Some fools are striking over there, and we have to pay the money.” Where was I supposed to get three rubles to pay? So they expelled me for that. I didn’t study for six months. I was barely reinstated through the efforts of my older brother, who had found a job as a school principal in that same village.

Working in the commune and studying at school, I finished that school naked and in tatters. And I finished it thanks to a teacher, Nykanor Vasylyovych Ruban, who gathered three of us ragamuffin students and set up a sort of boarding-school-type shelter for us at the school. We ate whatever was in the cafeteria. They had hot breakfasts, and we ate the leftovers.

That’s how I graduated from this school in 1936. I didn't even have money to be in the graduation photograph. But I received my diploma with only one B, which is equivalent to a silver medal today. That B was in the Russian language.

Then I moved to Kyiv to be with my mother, who found work on construction sites. Her maiden name was Maria Hryhorivna Bozhko. An aviation club was being built in Kyiv. At that time, Stalin was preparing his “Stalin's falcons.” My mother worked there as a cook. And I immediately applied to the university. They didn't accept me because they found traces of tuberculosis. One doctor told me: “Do you want to get well? No medicine will help. Go to a construction site and work there in the fresh air. That’s the most powerful medicine.” Back then, there were no medicines for tuberculosis.

I listened to him and went to work on the construction of a keyboard instrument factory. In reality, it was the construction of the Antonov military plant. I worked there for two years. I changed various professions, went through everything. But the time came for my military draft. I got scared: I didn't want to join the army. So I went and enrolled in Kyiv State University.

Iryna Pavlivna Kovalenko: Should I speak for myself? So, in 1938, Ivan enrolled in the university. He had a medal, and I had a medal, which allowed us to enroll without exams. But the rector at the time, Rusko, summoned us (we ended up in his office together) and said: “We cannot guarantee your admission to the faculties you have chosen.” (Ivan Yukhymovych had chosen the faculty of Ukrainian philology, and I, Russian philology). “I can guarantee you,” he said, “admission to the newly established faculty of Western European languages and literatures.” We didn't know each other yet, but we each considered it and decided it was better to enroll in this faculty. Especially since it was so prestigious and offered a certain scope. We were accepted into this newly created faculty. It was only the first year. We chose the French department of the Romano-Germanic faculty. That’s how we met, finding ourselves in the same group. Six months later, we were already friends, and on December 31, 1939, on Ivan Yukhymovych’s birthday, we got married.

From that time on, our life has been shared. Although Ivan Yukhymovych later served five years in the camps, we consider those years to have been lived together as well. I wrote him a letter every day. He thought of me, and I thought of him. And it's hard now to separate our biographies because we lived our whole lives as one, experienced everything together, thought alike, read the same books, and had the same interests.

I am from Chernihiv itself. I was born on August 26, 1919. So I am six months younger. My family belongs to the urban intelligentsia of Chernihiv. My mother, Olha Mykolaivna Pustosmikh (she died at the age of ninety-seven in 1979), worked with Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky in the statistics bureau. She was the youngest employee in this bureau, a so-called “clerk.” Kotsiubynsky used to visit us. Our families were friends. The children, my older brothers and sisters, would attend the Christmas tree party at the Kotsiubynsky house and were friends with his daughters, Oksana and Iryna.

My father, Pavlo Pylypovych Pustosmikh, was repressed in 1930 and exiled to Central Asia. My mother sold everything she could and went to save him because he had fallen gravely ill there. And my sister took me to Kyiv then, where I graduated from School No. 56. I graduated with flying colors.

My father was later shot. In 1937, he was arrested for a second time, there, in his new place. Without the right of correspondence... And “without the right of correspondence” meant he was shot. Ivan Yukhymovych later—still under Stalin—managed to obtain a certificate stating that he died of a stomach ulcer.

V.V. Ovsienko: They had a whole list of diseases that were assigned to anyone as the cause of death.

I.P. Kovalenko: Despite the fact that the primary language in Chernihiv was Russian, our family lived with Ukrainian interests. My mother subscribed to all the Ukrainian journals. And the atmosphere in that statistics bureau itself was progressive, Ukrainian, one might say. I have a photograph of Mykola Vorony, Arkadiy Kazka, who worked in the statistics bureau, and Kotsiubynsky all together. Pavlo Tychyna also visited us a little. He was acquainted with my older sister. But I have no memories of Tychyna. But my mother was very good friends with Mykola Vorony; he gave her some of his books and would inscribe them: “To my dear Ol-Ol.”

When I met Ivan, he had uncertain views... I can’t say they were that anti-Soviet. But I was precisely of that anti-Soviet mindset... After all, they had taken my father. I entered the university by concealing this fact. Somewhere I wrote that he had died. Otherwise, they wouldn't have accepted me into the university. I hated that regime. And Ivan Yukhymovych caught this spirit from me. He caught the hatred for those who execute innocent people. And I learned the Ukrainian language from him. And so we exchanged what we could, our riches, and began our life together.

V.V. Ovsienko: So you began your life together—but where did you live?

I.P. Kovalenko: At first, we didn't live together. I lived with my sister. She had her own family, her own children... And Ivan found a place in the Otradny khutir—that's what it was called then. It was just an open field with a barrack on it. There was a small airfield for planes where cadets were trained. And Ivan's younger brother was a cadet pilot. So in this barrack, he, his mother, and Ivan were given a small room to live in. But the brother finished his training, received an assignment, and left for somewhere. And once I got married, I went to that house, to that barrack. Well, it was impossible to exist there because the walls were so thin, it was so cold... How we ever survived there, I don't know. And it was a seven-kilometer walk to the university, because the trams were practically not running.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Seven kilometers to the tram. And a long way by tram after that.

I.P. Kovalenko: I don’t know—we rarely had the chance to take the tram. That's how we lived until the war.

And the war began for us like this. We were taking our exams for the third year. We worked very hard, very productively, and were passing the exams very well. We still had to pass a course on some Western literature. We were studying for it at night (Yakymovych was the instructor). One Sunday, a very sunny day, I went outside and saw planes flying overhead. The atmosphere was already such that war was about to break out. I thought: “I’ll scare him.” I came in and said: “Get up, the war has started, German bombers are already here.” And he took it as a joke. Suddenly, a neighbor comes and says: “They’ve bombed Zhuliany, the war has started!”

Well, the war began. We barely passed that exam and had to flee somewhere. We went to dig trenches with the other students. Then they summoned us all and said: “Go back to your homes. Classes will resume in three months. We will notify you.” But where were we to flee? To that barrack that was being bombed? Bombs had already started falling on that place by then. My sister had left—there was nowhere to live there either. So we went to my mother's in Chernihiv. But they had already managed to arrest my mother—arrested her for expressing the opinion that the Germans might actually occupy Chernihiv. She said she was very lucky (as she put it) that the investigator was a Ukrainian. If he had been a Jew, she wouldn't have been so lucky. Because the denunciation was written by her Jewish colleague. We arrived just as she had gotten home. It was great fortune.

But Chernihiv ended up in a special zone: the Germans, to get to Kyiv, first began bombing Chernihiv. And Chernihiv found itself among the most devastated cities. There are five such cities, starting with Stalingrad. Nothing was left of it. The bombings began... Kyiv had not yet been taken—but in three days, Chernihiv was destroyed. It was impossible to stay there. Even the regional party committee didn't have time to evacuate—Fedorov and all those... They didn't stay behind on assignment but because they didn't have time to escape.

We gathered some belongings and set off into the unknown—somewhere to the east, to escape the Germans. On foot, of course, no one gave us a cart. We walked all the way to Pyriatyn in the Poltava region. We lived there for three months, hoping that we could somehow break through further east, but we ended up in the Pyriatyn encirclement. Some peasants, good people, took us in there. We waited there for three months for a chance to move on... But then—a paratrooper landing in Lubny, and we were completely cut off. It was hopeless to continue.

We walked back. We retraced the entire same path to Chernihiv. The house was destroyed, nothing left, just walls... And there we survived the occupation. We nearly died of starvation. We sold what we could. Ivan took up drawing. He painted icons, sold them, and we went to the villages. The villages were well-off, they gave us potatoes. As a man, he couldn't walk on the roads. I went by myself to sell, to trade, bringing back what I could.

And Ivan Yukhymovych will continue from here.

(((The text in triple parentheses was crossed out by I.P. Kovalenko. V.V. Ovsienko: The Bolsheviks didn’t have time to carry everything out of the Chernihiv region or burn it, so the peasants had something left.)))

I.Yu. Kovalenko: We started to get by somehow, earning money for food, getting what we could—sometimes dead horse meat, sometimes other things. But the thing is, the Germans started organizing roundups and deporting the youth. We ran into an acquaintance of ours who said: “I’ll arrange a fictitious job for you with the Germans, at ‘Zagotzerno’ (Grain Procurement Office), so they won’t touch you.” We agreed. And so he arranged it.

I.P. Kovalenko: This was three months before the liberation.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes, three months before the liberation. Just as we got settled and received our Ausweise, the roundups began. They deported thousands and thousands then. But those papers saved us. We stayed there and waited for the (((so-called))) liberation.

(((I.P. Kovalenko: Not so-called, they really did liberate us. It was a real liberation.)))

I.Yu. Kovalenko: (((Liberation, liberation))). Again we endured the front, the shelling, the bombing, everything else... The next step was to find some teaching work, even though our education was incomplete...

I.P. Kovalenko: You skipped something.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: What?

I.P. Kovalenko: You skipped how we met the Frenchmen during the occupation.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Ah, that's my achievement. During the occupation, I met a whole large group of Frenchmen who were forced to work for the Germans.

I.P. Kovalenko: They were labor battalions. They had been mobilized for construction, sort of semi-prisoners. These were Frenchmen with very communist sentiments. And we, of course, already knew French and could communicate. So they started visiting us frequently, coming to our home, telling us about their lives, and we exchanged thoughts. They told us how hard it was for them to work, that many of them had died and were buried here, in Chernihiv. They asked that if Chernihiv were liberated (and the liberation was already approaching), and if they didn't live to see it, that we not forget the graves of their comrades. We promised them we would report about them and their request to the Soviet authorities, that it would be done, that we would fulfill their request because it is every person's duty. When our troops arrived, Ivan Yukhymovych immediately wrote a report about his work among the French.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: That I had conducted educational work, found literature in French.

The French were very drawn to me. To living people in general, because they didn’t understand the surrounding environment and the events that were taking place. Then they gave me their list. I finished the report and took it to the regional party committee. They were very interested in it. They scolded me terribly for not leading them into the forest to the partisans. But how could I?

I.P. Kovalenko: The Frenchmen didn't express such a desire.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: But I took the opportunity and said that I was out of work. So they told me: “A school is opening, go to the school.” And right away, from the first day, I was appointed director of the only surviving school, No. 4. I worked there for about four months, until the real, Party-member cadres started returning from evacuation. They created such conditions for me that I had to leave that directorship.

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, the conditions were like this: “You’ll bring that wardrobe to my home.” (And we had gathered those desks, those chairs, those wardrobes with such difficulty just to start classes...) “My family is returning—make sure I have a table and all that.” Well, such conditions that you either had to give bribes or...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Or something... After working like that for four months, we became regular teachers: I taught German and English, which I knew, and my wife taught German and Russian. We lived like that for four years in Chernihiv. We didn't plan on leaving, but we saw that they were starting to gradually remove everyone who had stayed during the occupation. First one person would disappear, then another, then a third. And it even happened to people like this: one day he's a school director, and the next day he's gone. So I said: “No matter how hard it is, let’s leave everything...” And we moved here, to Boyarka. My mother was working here, there was a small room. We got jobs at Boyarka School No. 1.

I.P. Kovalenko: Where we worked together for eight years, starting in 1947. And in 1945, our son was born, so there were three of us... Our son is an interesting figure: Oles Ivanovych Kovalenko. He is interesting because he is a polyglot, but his main language is English. He made a contribution to Ukrainian culture: he translated quite a few classic works by Ukrainian writers into English.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Seven classics.

I.P. Kovalenko: Such as, for example, Panas Myrny’s “Do the Oxen Bellow When the Mangers Are Full?” His translated books are here on the shelf: works by Kotsiubynsky, Marko Vovchok, Panas Myrny. Our son was born in 1945—just as the war ended, he was born.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes. We started working at the Boyarka school. We worked sincerely. We really liked this work. At first, things were a bit freer... So we did various things: we went on hikes, organized a theater, staged plays. And only classics: Gogol’s “The Government Inspector,” Ostrovsky’s “The Forest,” some Ukrainian plays. But even then I showed my “dissident” nature. When I spoke at an open Party meeting and said that it was all empty talk, they fired me. I was without a job for several years. True, I always had private lessons. I also worked at a military sanatorium.

I.P. Kovalenko: Tell them how they tried to pull you into the Party.

I.P. Kovalenko: The fact is, we didn't fit in at all, not just with the staff, but with the environment of Party members. We were constantly at war with the Soviet authorities at the level of the school's Party organization. We were “not like the others.” First, they wanted to break up our friendship somehow. We shouldn't talk about that, but rather about how they wanted to subdue us. And you can subdue someone in two ways. The first is to get us to join the Party. Once we were Party members, they could put pressure on us and “work us over,” that is, destroy our independence. But we avoided that. We avoided it at the cost of being fired. Because when they saw that it wasn't working, they had to destroy us in another way. And we spoke out against the directors, against plunder, against lies within the staff, against drunkenness, and against all the Party members, because they were all very stupid and very bad people. And professionally, they were worthless. But we were very highly valued. By whom? The parents and the children. So they had this jealousy or envy, and they couldn't forgive us for it. Every year, they wouldn't rehire us for the next school year.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Meaning, they fired us.

I.P. Kovalenko: So the year ends, the graduation party, bouquets, flowers, and such kind words from students and parents. And suddenly: “You have not been hired for the next school year.” And this went on for several years.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Or, for example, they'd pull me out of class: “Go to the KGB, let the KGB deal with you.” They pulled me out of class and sent me away.

I.P. Kovalenko: And all this because we had been under occupation. One time they said: “Go to 4 Engels Street. Let the KGB there give you a certificate that you are loyal.” We went, found that 4 Engels Street in Kyiv, and said: “They told us you need to check our political character.” They laughed and said that if they needed to, they would check.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: No, they said: “You go to the district office...” We went to Kyiv first.

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, who gives out such certificates? These are just details, showing what it came to. It was just regular harassment—high-level harassment. I kept my job, but Ivan Yukhymovych, being more energetic... He has such a character that he was hard to handle. So they fired him. He was effectively without a job for several years, until some kind of thaw began. This was already under Khrushchev. Tronko's brother worked in Boyarka, and Ivan tutored his children, preparing them for university. So this Tronko's brother somehow, through his own brother, got him permission to work in the evening school. The evening school was the same as a concentration camp because it was full of just “juvenile delinquents.” He worked there until they took him away. I.Yu. Kovalenko: No, I then worked as a teacher for four years in a day school.

I.P. Kovalenko: So you had a few classes at the third school.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Not a few, a lot—I worked for four years, fourteen hours. But all that doesn't matter. The main work was at the evening school and the military sanatorium.

I.P. Kovalenko: So you were picking up work here and there.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: But you are more interested in my creative work.

I started writing poetry from a very young age, already in school. Like all fools, I started in Russian. Then, under the influence of my teacher, Ruban, who had studied with Malyshko, I started writing in Ukrainian. But I never wrote any poems to please anyone. I could have been published in the district newspapers. But I just wrote for myself. What I thought, I wrote. Back in 1956, when Tychyna was still alive, he was writing such filth... So I wrote a poem about him that could have gotten me arrested even back then: [Recording glitch]

Ти не поет - ти деспоту служив,

Не Україні, а служив ти кату,

Віддав святині чисті супостату,

У грудях матері не бачачи ножів.

Ти відвертався від кривавих жнив,

Коли твою палили рідну хату.

Ти пузо грів і їжу їв багату,

І при житті ти смерть вже пережив.

Цвірінькнув в юності, дістав вінок і славу -

Вони тобі належать не по праву.

Віддай достойним слави і вінця -

Тим, що за матір гинули в Сибіру.

А ти, що у підлоті втратив міру,

Чекай ганебного кінця!

I read this only to... I mostly wrote lyrical poetry. My wife pushed me toward lyricism: you're a lyric poet, a lyric poet, a lyric poet. That's why I have a lot of lyrical work. But things like that would break through on their own, just on their own. I have a cycle of so-called “furious” poems about all these contemporary figures. (((((The text in triple parentheses was ordered not to be published by I.Yu. Kovalenko. How do you feel about Pavlychko?

V.V. Ovsienko: Well, we have to tolerate him as he is. He did have that poem “When the bloody Torquemada died...”

I.Yu. Kovalenko: But he also had the poem “The Murderers.”

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes, about those who drowned children in wells.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: And a poem about Afghanistan. Shall I read the one about Pavlychko?

I.P. Kovalenko: No, don't. It won't be in the book either.

V.V. Ovsienko: If it won't be in the book, then you must read it.

I.Yu. Kovalenko:

Цей дуже здібний віршомаз

Не обминав народну справу,

Та більше дбав про гроші й славу,

В огріхах каючись щораз.

Тоді він сходив на Парнас,

Як інших гнали на розправу.

І шкода постать цю яскраву:

У можновладців - свинопас.

Зробив чимало для Вкраїни,

Хоч і побив собі коліна.

Та мова зовсім не про те:

Чи залишається надія

Пристосуванця, лицедія,

Чи щось прокинеться святе?

This poem isn't in the book. But I have one about everyone...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: He wrote this in the 80s, when Pavlychko became Kravchuk's swineherd. For a poet to be with that fat, arrogant Kravchuk...)))

V.V. Ovsienko: Let's return to the Sixtiers movement itself. You were probably acquainted with the people called the Sixtiers?

I.P. Kovalenko: Yes. Now tell them how you were completely separate from literary circles. He lived his own life.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Detached.

I.P. Kovalenko: Detached. He didn't know anyone, never went anywhere, no one was interested in him. But there was a certain impetus in his life. That impetus was meeting Mykhailo Kutynsky. Kutynsky is the author of “Necropolis.” Now this “Necropolis” is being published under the name Shyshov, but Kutynsky is also mentioned. In fact, the sole author of “Necropolis” was Kutynsky. He gave us the entire “Necropolis” that he wrote, unpublished. It’s lying up in our attic. Do you know what “Necropolis” is?

V.V. Ovsienko: No, I don't.

I.P. Kovalenko: “Necropolis” is a huge work. Literally, it translates to “city of the dead.” Kutynsky single-handedly carried out this colossal work—he collected data on all the prominent Ukrainian figures who lived and worked on this land and wrote an encyclopedia: where, who, when they were born, died, what they did—a short reference—and where they are buried, and in what condition their grave is.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: He came here to the grave of Volodymyr Samiylenko. We met him. He started visiting us, telling us about his work. Suddenly he asked: “Do you have anything written?” I said: “I do.” Then my wife gave him a few of my poems. That’s when I started getting published. But that was later. At first, she copied the poems and gave them to him. He made my first little collection, “Chervona Kalyna” (The Red Guelder-Rose).

V.V. Ovsienko: In what year did you meet Mykhailo Kutynsky?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: In the late sixties.

I.P. Kovalenko: No. From 1965, something like that. Because 1968—that was already Czechoslovakia.

I.P. Kovalenko: So, 1966, maybe that year.

V.V. Ovsienko: And the collection “Chervona Kalyna”—what was its fate?

I.P. Kovalenko: Kutynsky typed it up, bound it like a notebook, and gave it to Ivan Yukhymovych. He said it was his first little collection.

V.V. Ovsienko: In a single copy?

I.P. Kovalenko: In a single copy.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: No. In four copies. Another push for my public activity was meeting Yevhen Sverstiuk. I was the head of the trade union committee.

I.P. Kovalenko: At the evening school.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: I wanted to arrange a meeting with Ukrainian writers. We had one teacher. I asked her: “Do you know anyone?” She said: “I know Sverstiuk.” “Could he come here?” (I had been following his writings in the newspapers all the time, I subscribed to `Literaturna Ukraina`). She said: “He can.” “Then tell him to come.” And they came: Yevhen Sverstiuk, Vasyl Stus, and Nadiia Svitlychna. The three of them.

V.V. Ovsienko: Could you pinpoint when this was? Stus had been in Kyiv since 1963.

I.P. Kovalenko: Sixty... From that time, the surveillance on Ivan Yukhymovych began. It was 1966.

V.V. Ovsienko: Had the arrests of 1965 already happened? Was this before or after the arrests?

I.P. Kovalenko: After them. 1966.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: I gathered a huge class—up to two hundred students. And the poets read their works there for three hours. Who did they read? First, Sverstiuk gave a speech. He gave such a speech, it was nothing like what he writes now, nothing like it... He gave the speech, and then he read poems. He read poems by Vasyl Symonenko, the uncensored, unpublished ones. He read poems by Bulayenko—he was well-known then. And Nadiia Svitlychna read Ivan Drach—she said she was in love with Drach, though I see nothing special in him. She read Drach.

I.P. Kovalenko: Stus read.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: And Vasyl Stus read his poems. He was a bit nervous, flustered, but he read beautiful, profound poems. I'm amazed that the students sat without fidgeting and listened for three hours. Later, I caught up with the poets at the train station, got acquainted with Sverstiuk, with all of them, and I read one of my own poems to Sverstiuk—“The Judases.” He said: “Oh, a fine poem, if only it could be published.” It's in the collection. After that, I found out where Sverstiuk worked and visited him several times. Thanks to Kutynsky and samvydat, “Kalyna” spread. It ended up in Czechoslovakia, in the newspaper `Nove Zhyttia` (New Life).

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, Kutynsky simply sent his poems, including “Chervona Kalyna,” to the Czechoslovak newspaper `Nove Zhyttia`.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: The first poem published there was “Chervona Kalyna.” Then they wrote a letter and asked me to send something else. I also sent them “Bandura.” It’s impossible to list how many, because everything was lost.

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, a dozen and a half poems and two interesting articles. One article was “Kyivan Honcharivka.” It was about Ivan Honchar’s museum. The second article was about St. Michael’s Cathedral.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: I predicted that St. Michael’s Cathedral would be restored.

I.P. Kovalenko: And he wrote: “I believe that one day it will be restored.”

V.V. Ovsienko: Did you see St. Michael’s Cathedral?

I.P. Kovalenko: No, the one that was destroyed, he didn't see it—he wasn't living in Kyiv yet.

They asked us to send our poems, saying they liked them. Later, this became the main accusation: you see, he was publishing abroad.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Twelve or thirteen poems were reprinted in Canada. They published a little booklet on a printer. The KGB shoved this at me: “See, this is how it was in Czechoslovakia. And why was it also reprinted in Canada?”

N.B. Kotlyarevska: If you didn't receive any royalties, what does it have to do with you?

I.P. Kovalenko: As if they cared about that. The fact was that it was abroad.

N.B. Kotlyarevska: You hadn't seen this booklet, but they already had it.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: At the school, they were celebrating the centenary of Shevchenko's death, and I read one poem. Later, the investigator told me: “It was after that poem that we placed you under surveillance.”

V.V. Ovsienko: Is it also in your book?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes. I never thought they would arrest a provincial teacher from some small town for that.

I.P. Kovalenko: Mykhailo Kutynsky also supplied us with samvydat. They took two whole carloads of samvydat from us. They found the largest amount of samvydat at our place, a whole library. Everything that was published in Ukraine and Russia. And Kutynsky brought us everything he could get. In the summer, he would vacation here and bring all this literature to us, so as not to keep it at his place. His apartment was small. And so that people would be enlightened. And Ivan Yukhymovych distributed it very generously...

V.V. Ovsienko: Was Boyarka filled with samvydat?

I.P. Kovalenko: Filled. In the evening, Ivan Yukhymovych would come home from school—and students would already be waiting by the fence. He would pick something out, pick something out—and bring it out. I would say: “You’re going to get into trouble.” “They won’t snitch.” And then they interrogated two hundred students.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Not two hundred. They interrogated one hundred and forty students.

I.P. Kovalenko: They asked: did he give you anything to read? No one said a thing.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: No one said a thing.

V.V. Ovsienko: So you had very good students.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: I'm surprised myself. They said: “He gave us a French grammar book.” How is it that they interrogated one hundred and forty students—and they said nothing? Well, we can end on that.

On January 13, on my very birthday, eight cars showed up here. Eight cars were parked on all the corners, and two were right here. And eight people conducted a search for eight hours.

V.V. Ovsienko: And the certificate says January 13, 1972. But why do you say it's your birthday? Didn't you say December 31?

I.P. Kovalenko: The thing is, he was actually born on January 13, 1919. But he was registered on the last day of the previous year for the army—they used to do that for the army. Anyone born in the first month would be registered in the previous year, so they would be drafted into the army earlier. We always celebrate on January 13.

There was no banquet. He had just recovered from an illness and had gone out and stood in line for some “dog’s delight” (sausage) and was on his way home. And they had sent me to the district education department to submit some papers. It wasn't necessary, but there was such pressure... I got delayed there. I arrive—and one of them is standing here... And Ivan Yukhymovych gestures and says: “Look! Beria's heirs are at work!” They were rummaging through a drawer. They really held that against him later.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: The search at my place wasn't as long as at Ivan Svitlychny's. At Svitlychny's, it was twenty-four hours.

I.P. Kovalenko: The thing is, Svitlychny was a conspirator and an experienced man. And this one... First, they knew where everything was. They went straight to the library, and also found Ivan Yukhymovych's materials in a nook under the roof, and the things I had copied. My things were here, his were there. They only went to two places.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: They had conducted secret searches before that.

N.B. Kotlyarevska: So they had already been хозяйнували (making themselves at home) in your house without you?

I.P. Kovalenko: Someone already knew where everything was. They just took all my things. I had written letters to Kutynsky, and Kutynsky had returned them to me. Then they crucified me too for what I had written there. I wrote letters to Kutynsky, commenting on and reviewing his works. He wrote many works and dedicated them to me because I was very interested in them. Then he expressed a wish for me to write a critical article about one of his works. I wrote it. He liked it very much. But he returned the original—also a conspiratorial move... He didn't want to have it. Because he, Kutynsky, had served 25 years, so he thought it was safe here, but dangerous at his place. Later they said they would have definitely taken me too, but they took pity on the children and the mothers. My mother was already over ninety, and his mother was paralyzed. Our son had been caring for her for ten years, and then they took him... And our daughter was still in the younger grades of school.

V.V. Ovsienko: Your son Oles was born in 1945. And your daughter?

I.P. Kovalenko: She was born in 1957, Maria. Maryna Kovalenko.

V.V. Ovsienko: And were they living here then, when the search took place?

I.P. Kovalenko: Our son was at work. He worked for “Intourist.” At first, when he graduated from the university, they sent him abroad right away. He was an interpreter abroad. They sent him to Egypt, he worked as an interpreter on a liner, sailed the seas and oceans. He was in six countries. They sent him twice. And then it was as if a line was drawn. And that was the end of his career. He showed such promise. They were already planning to take him into the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. But when they secretly started persecuting his father—that was it. They drew a line, and after that, he didn't take a single step forward. Not one step could he make. They stuck him in a translation bureau. He translated for people there. He was just a clerk. And to this day, he just does translations. But his career is over. He lives in Kyiv.

And our daughter lives in Boyarka. She graduated from the institute. She had a Kyiv residence permit. But she was assigned to Borodianka, even though everyone with a Kyiv permit was assigned to Kyiv. This was after Ivan Yukhymovych was already home, but they gave her no opportunity. They basically didn't even let her teach.

V.V. Ovsienko: She also studied foreign languages?

I.P. Kovalenko: Yes. Ivan Yukhymovych has three languages, and she has French. So she works in a library. A very good friend of ours, Academician Hennadiy Kharlampiyovych Matsuka, simply went to the minister and asked for her to be given a free diploma, so they wouldn't send her to that backwater near Chornobyl.

V.V. Ovsienko: Were there any signs before your arrest that they were coming for you? Or perhaps you were in the circle of people arrested in 1972? At Svitlychny's, maybe, or with someone else? What were your relationships with these people?

I.P. Kovalenko: None.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: No, I was acquainted with the Svitlychnys. I used to visit the Writers' Union... Because they would invite me—someone from Czechoslovakia would be visiting, and they'd send me a telegram: “Please appear with new works.” And so the last time I went, I took many of my works, and met many very interesting people. Sverstiuk met me, introduced me to everyone: to Dziuba, to Svitlychny, to everyone. Musinka was visiting then. Miklos. I was supposed to give him my works. But I thought about it and decided I would refrain this time—the times were very uncertain. And it's not that I regretted it, but it was just some kind of premonition. And then I read in the newspaper that Miklos Musinka had been detained and a lot of samvydat had been confiscated from his belt. But mine wasn't there. But I met the editor of the newspaper `Druzhno vpered` (Forward Together) there, and other people. It was in the camp that I got to know Svitlychny better. There were eight of us poets in there. I knew Svitlychny very well. Ihor Kalynets, Taras Melnychuk... Who else?

V.V. Ovsienko: Probably Stepan Sapeliak?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: No, Sapeliak wasn't with us.

V.V. Ovsienko: Well, Vasyl Zakharchenko. I don't think he wrote poems...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Zakharchenko didn't write. But he was with us and greatly disgraced himself.

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes, I know about his repentant statement.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: The fact that he wrote a repentance is one thing. But in the camp, he was an ordinary stool pigeon.

I.P. Kovalenko: As it turned out later.

V.V. Ovsienko: You know, Vasyl Stus was already in exile when they released Zakharchenko—and he was his kinsman. He sent his kinsman a telegram with a single word: “Fie, Vasyl.”

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Zakharchenko behaved very shamefully. When a few people would gather and talk, about a hunger strike, about this and that—he would sneak up unnoticed and listen to everything. Then—suddenly, a pardon. He was pardoned, released a year or more early. And the sentence they gave him was so... And then came his repentance in `Literaturna Ukraina`. Have you read it?

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes, yes. I read it back then in `Literaturna Ukraina`, I think in 1977.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Why is it shameful? Dziuba also repented, but he didn't mention anyone there, absolutely no one. But Zakharchenko—he named Kalynets, Hluzman, everyone, absolutely everyone. He spat on all of them. He behaved very dishonorably. Well, fine, he did it himself, repented himself, so let him be. But for them to give him the Shevchenko Prize after that, for God knows what.

I.P. Kovalenko: Yes, for his betrayal.

V.V. Ovsienko: But we've gotten a bit ahead of ourselves. This search—how did you perceive it? The arrest? How did the investigation proceed? Who conducted the investigation? It would be good to talk about this in more detail.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: My search was more or less easy. When I heard about the searches at Svitlychny's, at Dziuba's, I thought mine was child's play: only eight agents and it lasted only eight hours. Well, they took books, rummaged through this and that, made me open the beds, the sofas. They searched everywhere.

V.V. Ovsienko: You probably didn't hide the samvydat?

I.P. Kovalenko: It was right there, in the library. It had to be within reach.

V.V. Ovsienko: It's interesting what they took from you. Could you name at least the most important things?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Everything that was being circulated then. Everything.

V.V. Ovsienko: Ivan Dziuba, obviously, “Internationalism or Russification?”

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Dziuba—of course.

V.V. Ovsienko: “The Ukrainian Herald”?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: “The Ukrainian Herald.”

I.P. Kovalenko: Works by Viacheslav Chornovil, all of Valentyn Moroz's articles.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: “Regarding the Trial of Pohruzhalsky.” One work copied in Iryna Pavlivna’s hand...

I.P. Kovalenko: “Woe from Wit.”

V.V. Ovsienko: “Woe from Wit” is Chornovil's. Moroz's “A Chronicle of Resistance.”

I.P. Kovalenko: Correct. “Amid the Snows”...

V.V. Ovsienko: “A Report from the Beria Reserve”—that's Moroz's.

I.P. Kovalenko: Yes.

V.V. Ovsienko: And “Instead of a Final Word.”

I.P. Kovalenko: We had all of that.

V.V. Ovsienko: Absolutely everything...

I.P. Kovalenko: And, well, Kutynsky's “Necropolis.”

V.V. Ovsienko: They took that too?

I.P. Kovalenko: They took it.

V.V. Ovsienko: What was the fate of that work?

I.P. Kovalenko: It was returned from the KGB.

V.V. Ovsienko: Returned? And is Kutynsky himself still alive?

I.P. Kovalenko: He has already passed away.

V.V. Ovsienko: To whom did they return “Necropolis”? To him?

I.P. Kovalenko: They returned it to us, because they took it from us.

V.V. Ovsienko: Someone should prepare it for publication.

I.P. Kovalenko: But it has already been published.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: It is being published.

V.V. Ovsienko: Where?

I.P. Kovalenko: It's being published in small portions in the journal `Dnipro`.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes. It's just a mockery.

I.P. Kovalenko: But it needs to be published separately.

V.V. Ovsienko: But if it's being published in a journal, then it won't be lost.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: For the third or fourth year, it's being published in the journal in such small paragraphs.

I.P. Kovalenko: Kutynsky was friends with Shyshov. He did some of it, Kutynsky did some. Well, mostly Kutynsky. Kutynsky never got up from his typewriter.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: He produced “Necropolis” in eight copies. Then he distributed them all among people. The KGB were rubbing their hands: we've confiscated all of Kutynsky's copies.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: All copies... But it turned out that Shyshov didn't have this one.

I.P. Kovalenko: His wife came here recently and said that someone else here in Kyiv still has a copy.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Not only that, he had a large card catalog. He worked like a real scholar. He gave it to some Kozyrenko. The KGB agents came to him and said: “You're holding on to it.” He got scared and immediately brought it out to them. A huge card catalog. There were eight thousand names in it.

I.P. Kovalenko: Such was Kutynsky's feat...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Such a feat. And he came here to Samiylenko's grave. And he wrote such an indignant article: is there even one teacher of Ukrainian language here? They don't see that Volodymyr Samiylenko's grave here is so neglected—no monument, nothing.

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, something is being arranged there now.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes. The investigation lasted nine months. The investigator was Mykola Andriyovych Koval. He spoke exclusively in Ukrainian. He did not use methods of physical coercion. But methods of psychological coercion—as much as you want.

I.P. Kovalenko: They were dishonest methods. For example, he would say: “Such and such people have already testified against you...” And he believed that they had.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: And I believed it: that one said you gave it to him, and that one said you gave it to him, and that one said you gave it to him, and so on...

I.P. Kovalenko: And he really did give samvydat to many people. And maybe they were watching how it happened—I don’t know.

V.V. Ovsienko: They had operational intelligence. Or they had suspicions. So they could use that to blackmail him.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: No, it was just their method.

I.P. Kovalenko: Why not? You gave it to Hlushchuk, and he said they gave it to Hlushchuk and summoned Hlushchuk? Well, so what? They knew some things.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: They were tailing me. He frankly said that the surveillance began in 1961.

I.P. Kovalenko: And you ask if there were any signs of the approaching arrest. Well, in hindsight, there really were. You could feel it, a certain atmosphere was felt both at my work and at his work.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: And there were threats against me at work: “You’ll see what happens to you...”—they said things like that. Four of my colleagues wrote a denunciation against me: the director, the head teacher, the secretary of the Party organization, and one other teacher.

V.V. Ovsienko: They wrote the denunciations before the arrest?

I.P. Kovalenko: They wrote it two years after the events in Czechoslovakia... The thing is, when the events in Czechoslovakia happened, Ivan Yukhymovych, that very day, made a declaration in the teachers' lounge, organized a sort of rally. The teachers were there, and he said: “This is a fascist action.” They wrote a denunciation then.

V.V. Ovsienko: So this denunciation lay in wait?

I.P. Kovalenko: Yes, it was waiting. But on the eve of the arrest, they summoned these people to renew the denunciation, to rewrite that paper in their own hand. This was one of the charges—the fact that he condemned such an event. I told him then that he shouldn't do that.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: They wrote that denunciation in 1970. Well, I was born that way, I can't tolerate anything like that. I can't tolerate it—and I called it a fascist action. You can't bring tanks into an independent country and crush people with tanks. That was one of the main charges. In general, in my camp, five people were imprisoned for Czechoslovakia.

I.P. Kovalenko: Samvydat, Czechoslovakia, poems like “Chervona Kalyna.”

V.V. Ovsienko: Were your own works also incriminated?

I.P. Kovalenko: Of course! Only in a stupid way somehow.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: What infuriates me most is that they incriminated me for the poem “The Unmown Meadow.”

I.P. Kovalenko: They really disliked “The Unmown Meadow.” They even interrogated me at the trial, asking what I thought about “The Unmown Meadow.” I said: “It's a poem completely devoid of political content—it's a philosophical reflection on how a person failed to realize their purpose.” “No, he meant something else here—what does ‘with a scythe in hand’ mean?”

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes, as in, we've been mowing and mowing Ukraine, but it's still not fully mown—is that it? They knew what they were asking.

I.P. Kovalenko: So stupid...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: The main thing is that of all these poems, “The Unmown Meadow” ended up in the cassation ruling of the Supreme Court. I filed an appeal... I have so many poems they could have latched onto, but they chose “The Unmown Meadow.”

N.B. Kotlyarevska: That shows their level.

I.P. Kovalenko: He was supposed to get a longer sentence than he did. But we were very lucky, you could say. I traveled to find him a lawyer.

V.V. Ovsienko: And who did you find?

I.P. Kovalenko: I found a certain... I've forgotten his last name. I only know that he was Jewish. They recommended him to me, said he was very good.

V.V. Ovsienko: Was he from Kyiv?

I.P. Kovalenko: From Kyiv, from Kyiv. An acquaintance recommended him. She had already used him in some case. She said he was a very good lawyer. He took on the case.

V.V. Ovsienko: But still, only lawyers who had clearance were allowed on these cases. They were KGB lawyers.

I.P. Kovalenko: Yes. That lawyer went to see Ivan Yukhymovych for the first conversation. And Ivan said: “Are you a Party member?” “A Party member.” “Then how can you judge me objectively if you are a Party member? Are you not Ukrainian?” “Not Ukrainian.” “Then what can you say about me, a Ukrainian?” The man spat and said he didn't want to take the case. I felt helpless because one lawyer had refused, and there were no others. I was sitting in that law office near the Golden Gate in Kyiv, very sad. And the head of the office called me in and said: “I can offer you the lawyer Yezhov.” I thought: who is this Yezhov? This Yezhov came out to me and said: “I’ve looked it over—there’s no case there. It can be dismantled in half an hour. There’s nothing there. I’ll take the case.” And so that Yezhov went. He had previously worked in a tribunal somewhere in the Baltics. He was completely removed from Ukrainian affairs. He knew nothing about Ukrainian national events—a complete outsider. But he was probably a good professional. He said: “I am currently defending war criminals, and I’ve already saved several of them. They were wrongly accused. I came here, I don’t know anything about what’s happening in Kyiv. Well, I’ll figure it out.” He came to Ivan Yukhymovych, who said: “What is this, that there are no good lawyers anymore? Once there were various Konis and Plevakos—and now there are none?” “I will prove to you that there are!” And during the trial, he spoke very well. But they didn't let anyone into the courtroom.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: It was a closed trial.

I.P. Kovalenko: He shouted so loudly that they could hear him in the hallway. The secretary ran out and closed the windows... He said: “What, you summoned his colleagues and forced them to write these few denunciations—and you're judging a man on that basis?”

I.Yu. Kovalenko: “...What has the KGB come to! If in 1937 one denunciation was enough for a man to disappear, you summon four colleagues and force them to write denunciations against their own colleague?”

I.P. Kovalenko: In short, he would have gotten more. But Yezhov made a very strong impression, even on the judges. The prosecutor demanded six years in camps and three in exile. But in the end, it was five years.

V.V. Ovsienko: And who was the judge? The prosecutor?

I.P. Kovalenko: The judge was Matsko. And the prosecutor... I only know he was one-armed.

V.V. Ovsienko: Ah, one-armed? Many people know about him.* *(Probably V.P. Pohorily - V.O.)

I.P. Kovalenko: He was a terrible beast... Later, after Ivan Yukhymovych’s trial, Yezhov became so popular that everyone started hiring him. He handled several trials. One girl was even acquitted based on his arguments.

V.V. Ovsienko: A political prisoner?

I.P. Kovalenko: A political prisoner, yes. A girl was imprisoned somewhere in Odesa or...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: In Odesa.

I.P. Kovalenko: In Odesa. She was completely acquitted. And then they revoked his clearance.

V.V. Ovsienko: Of course.

I.P. Kovalenko: I met with him here. He was so frightened. He said: “No. I can’t.” He had a heart attack then, they expelled him from the Party. He was in a terrible state.

[End of track]

I.Yu. Kovalenko: ...And who is going to listen to all of this?

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, your job is to tell it—maybe something will remain for history.

V.V. Ovsienko: We will definitely transcribe these texts onto paper, and I will bring them to you to read and correct any mistakes.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Just write whatever you want.

I.P. Kovalenko: And so Mykhailo Kutynsky gave Ivan Yukhymovych such a push that he started writing. Throughout his life, he had written like this: now and then, from time to time, maybe two poems a year—and even those he would lose. But now he felt that he could do something, that someone was interested. He wrote quite a few poems then.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: I bought a typewriter and typed and compiled two collections myself. One collection, called “Pearls,” had 138 poems, and the second, “The Unmown Meadow,” had 60 poems. Two collections. These collections circulated among people. They were even found as far away as Moscow. I typed these collections myself... But they found them all anyway.

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, they were standing right there, next to the samvydat, neatly bound and signed.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: No, no, I didn't have them here.

I.P. Kovalenko: What wasn't here?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: The collections weren't here.

I.B. Kotlyarevska: There were none left, people had already taken them all?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: They weren't here. They showed me the ones they confiscated from Kutynsky.

I.P. Kovalenko: The investigator traveled to Kutynsky, interrogated him in Moscow. They went to Chernihiv, questioned the whole street there: did he compromise himself in any way during the occupation. They found nothing, no harvest there.

V.V. Ovsienko: How did you endure this investigation? What were the living conditions like? How did you experience it psychologically?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: It was hard, of course. Extremely hard.

V.V. Ovsienko: Were you psychologically prepared for arrest?

I.P. Kovalenko: Yes. He was psychologically prepared, but...

V.V. Ovsienko: But legally, probably not prepared?

I.P. Kovalenko: He didn't know how to behave.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: I wasn't prepared physiologically, I wasn't prepared physically. Because no one distributed any kind of guide on how to behave.

I.P. Kovalenko: Later Hluzman wrote one with Bukovsky...

V.V. Ovsienko: That was later, in confinement. But before that... I also didn't know how to behave.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: I didn't know how to behave. That's why I got a bit scared in there. But I didn't say anything about anyone to anyone—I denied everything. The only one I couldn't deny was Kutynsky.

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, the correspondence, that correspondence of Kutynsky's...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: They took all the correspondence from me, they took all the correspondence from my friends, everything. And most importantly, the letters that hadn't arrived—they opened them and showed them to me: “Here you write: ‘...life is hard enough as it is, and now this centenary is stuck in my craw...’”

I.P. Kovalenko: Lenin's... Or this: “I read Shtemenko—it’s like I've been smeared in shit.”

V.V. Ovsienko: Is that about the book by that Chief of the General Staff?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: That was in one letter. Even the prosecutor mentioned it in his speech: “How can he say such a thing about our distinguished general?!”

N.B. Kotlyarevska: The letters weren't reaching their addressees. They were intercepting them along the way.

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, how did you feel at first? Koval told me: “And your husband says: ‘I’m resting here with you, because I was so tired: looking after my mother, giving lessons, supporting the family...’”

V.V. Ovsienko: And distributing samvydat on top of it all.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes. And typing everything, staying up at night. Staying up at night.

I.P. Kovalenko: “...At least I'll get some rest with you,”—well, that was just said for effect. What kind of rest is that, when your heart aches for your family?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Well, you know yourself what it's like to sleep there. The lamp is on all night, and you can't turn on your side, only lie straight.

V.V. Ovsienko: They only allowed you to cover your eyes with a handkerchief like this.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: That's all, they only allowed you to cover your eyes with a handkerchief. And your hands had to be on top of the blanket...

I.P. Kovalenko: So you wouldn't suffocate yourself...

V.V. Ovsienko: Some people don't talk about these daily life things... And you can't go out, there's no toilet. That slop bucket is standing there... And they are constantly looking in, constantly. There's a peephole in the door, and someone is always walking by, always looking in. Sometimes women were on duty there too. And if you needed to use that bucket, you had to hide somehow in the corner. And you couldn't ask to be taken out.

I.P. Kovalenko: It's horrible!

I.Yu. Kovalenko: The hardest part wasn't the investigation, but the transport.

V.V. Ovsienko: And who were you in a cell with during the investigation? Not alone, were you? Was there some suspicious person?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: A suspicious person—a plant, a stool pigeon.

V.V. Ovsienko: Well, of course.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: We were two to a cell.

I.P. Kovalenko: You were alone most of the time, though.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: No, after I realized that my cellmate was trying to pry everything out of me, I demanded to be left alone. “But that’s not allowed.” I said: “Let it not be allowed. Or else I'll kill him.”

V.V. Ovsienko: Was Sapozhnikov the head of the investigative isolator there?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Sapozhnikov.

V.V. Ovsienko: Yanovsky was Sapozhnikov's deputy.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: They left me alone. For the last two months, I was alone.

V.V. Ovsienko: During the investigation or after?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: After the investigation.

V.V. Ovsienko: And when was your trial? How long did it last, how did the process go? And you, Iryna Pavlivna, were you at the trial?

I.P. Kovalenko: Yes. Well, they only...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: First of all, for some reason, they gave me a closed trial. Why?

V.V. Ovsienko: And does the verdict state that it was closed?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Closed.

V.V. Ovsienko: Mine at least says “open.”

I.Yu. Kovalenko: It was all KGB agents sitting there anyway.

I.P. Kovalenko: It was closed because many students could have come to the trial. And the students... By the way, they fired me from my job too. They really did fire me. Well, they were counting on the students turning away from me. But the opposite happened. I was surrounded by such attention from the students... They fired me, but allowed me to finish the school year. This was 1973. I happened to have a graduating tenth-grade class. They let me finish the year. And they fired me somewhere in the spring, before the exams. So they let me administer the exams for another month. And that was it.

And so one day I was late for work, because it's quite a walk to that first school. And the students... It was my class. The head teacher had already arrived and hinted that Iryna Pavlivna had probably been detained, since she hadn't shown up for work. And I, out of breath, burst into the classroom. The students stood up and gave me such an ovation. I felt so...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: That you hadn't been arrested.

I.P. Kovalenko: And there was so much more: they sent people to check on the political upbringing of my children, they arranged exams. They were all so united, so concerned, so eager to support me. And then, at the graduation party, on the very last evening, as three classes were sitting there (I happened to be teaching in three classes)... I stood up to say a few farewell words, not hinting at anything. Nothing, just, go into life... And as soon as I stood up—all three classes stood up, you understand? I told Kutynsky about it, and he said it was a very good sign. After all, our society was no longer like it used to be, when the slightest suspicion was enough for everyone to turn away from you and believe it, and be afraid. But all three classes stood up—and the parents, and everyone. And they gave such an ovation!

So I want to say that the persecution was on two fronts—not just you, but me as well. And later they said: “We would have imprisoned her, but we felt sorry for the children and the mothers.” And his mother died right away.

N.B. Kotlyarevska: Yukhymovych's mother.

V.V. Ovsienko: How long did the trial last?

I.P. Kovalenko: It was... It started on July 6, 1972, and ended on the 11th.

V.V. Ovsienko: So you were one of the first to be sentenced?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: No, I was the second.

I.P. Kovalenko: After Stus. I was standing outside the building when Stus’s wife came out crying that he had received such a long sentence. But among the first. Serhiyenko had already been sentenced, because I was there with Oksana Yakivna. And in the Supreme Court, when the appeal was filed, both Serhiyenko and Kovalenko were considered together.

V.V. Ovsienko: Did you write a cassation appeal?

I.P. Kovalenko: Yes, the lawyer wrote it. Well, we understood that it wouldn't change anything.

V.V. Ovsienko: The sentence stood as it was?

I.P. Kovalenko: It stood as it was. They said: “We would have, so to speak, acquitted him. But he read it to his wife and his son.”

I.Yu. Kovalenko: That's not the point. I wouldn't have been imprisoned. When the trial had already begun, they brought me to the court early, the prosecutor came and brought a newspaper with Mykola Kholodny’s repentance, “On the Scales of Conscience”: “Read this, write something similar, and the trial will not take place. We will release you.” I read it and returned the newspaper to him. And I said: “If he had repented for what he himself had done, this or that, I might have forgiven him. But he slung so much mud on good people: on Ivan Honchar, on Hontovy...”

V.V. Ovsienko: On Oksana Meshko...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: “...on Oksana Meshko, that you will not get such a thing from me. Judge me.” And so it went. But if I had written...

V.V. Ovsienko: Well, certainly...

I.P. Kovalenko: They really valued those people who...

V.V. Ovsienko: Zinoviia Franko made a repentant statement then, Mykola Kholodny, Seleznenko...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Well, I said, I won't be disingenuous: “I can write only three words: I promise to have nothing more to do with samvydat. That’s all. If that suits you, take my repentance.”

N.B. Kotlyarevska: That wasn't enough for them?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Not enough.

V.V. Ovsienko: That wouldn't have worked in the press.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: And they, those scoundrels...

I.P. Kovalenko: Honchar also played a big role in your life.

V.V. Ovsienko: Ivan Makarovych Honchar.

I.P. Kovalenko: He visited Honchar several times, wrote him letters.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: He wrote poems to him, reviews, wrote about his museum...

I.P. Kovalenko: And encouraged young people to visit there. And then several of those young people had big problems. Why, you see, were they visiting Honchar's museum? (((One of our students, her father had to go to great lengths to keep her from being expelled from the institute.)))

V.V. Ovsienko: You said the transport was very difficult. When did you go on transport?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: It was in early September. You've been through these transports—they don't take you directly, but through four or five prisons.

V.V. Ovsienko: First Kharkiv, I suppose?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Kharkiv. There I was lucky to meet Vasyl Romaniuk, the future Patriarch Volodymyr. They put me in the basement. The windows were broken, it was cold, just terrible.

V.V. Ovsienko: And probably iron bunks?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes, made of sheet iron.

V.V. Ovsienko: Those are the death row cells.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Death row cells. I thought I was going to die right there.

I.P. Kovalenko: He was the oldest of the dissidents...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: And then the door opens and the prison warden himself comes in: “So you’re a political?” “Political.” “And why did you end up here?” “I wrote poems.” “And they imprison people for that?” And I say: “They do.” “Well, I’ll help you.” “What can you do to help?” “I have one free cell for pregnant women. I’ll put you there.” So, he moved me to this cell for pregnant women. I lived there for two days. It was a completely different matter: a soft bed there. I asked: “Are there any other Ukrainians here?” He said: “They brought another Ukrainian, he’s in a cell alone.” I said: “Move me in with him.” And he said: “But it’ll be such that you...” And I said: “Move me.” He moved me there—and I ended up with Romaniuk. And we lived there together for about a week. Oh, did we talk! I had been in solitary for two months, so we talked and talked our fill. And then we traveled together, on the road, where they turn for Mordovia...

V.V. Ovsienko: Ruzayevka.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes. They took him off there, and took me to Perm. They took me to Sverdlovsk, and then to Perm.

V.V. Ovsienko: And Romaniuk to Mordovia, to Sosnovka, to the special regime.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: It's hell in those transit prisons. In a cell that's supposed to hold twenty or thirty, they pack in sixty. Everyone smokes. Until I started smoking myself, because one person advised me: “If you want to survive, learn to smoke.” Because the heart can't take it if it's not prepared. So I hadn't smoked for fifty-five years, but I bought some cigarettes and started getting used to it bit by bit. And that saved my life. They don't take you out for walks, there's no ventilation, everyone smokes, and they even boil tea with newspapers. But you've been through all this yourself.

V.V. Ovsienko: So they transported you just like that, with common criminals?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: With common criminals.

V.V. Ovsienko: For some reason, they almost always separated me from them.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: They transported me with criminals.

I.P. Kovalenko: Maybe you're more dangerous? They stole his hat on the way. So he arrived bareheaded like that.

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes, and it was already autumn. How many days were you on transport?

I.P. Kovalenko: You were already there in October, weren't you?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes, in October. Twenty or thirty days.

V.V. Ovsienko: In 1981, they transported me from Zhytomyr to the Urals, to Kuchino, for thirty-six days.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: You see, you went through the very same transports.

V.V. Ovsienko: And then, in 1974, they brought me to Mordovia.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: How old were you then?

V.V. Ovsienko: I was 24-25 then. And which camp zone did you end up in?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: In VS-389/35. That was a stroke of luck for me too.

V.V. Ovsienko: Is that Vsekhsvyatskaya station?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes. The settlement of Tsentralny. I ended up there. That was also a bit of luck for me, because there...

I.P. Kovalenko: And for the first time, he found himself among writers.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: There, conversations about everything began. In the camp, there were initially two hundred prisoners. 75 percent of them were Ukrainians. The rest were Lithuanians, Armenians, others...

I.P. Kovalenko: And there were Russians, Jews...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Russians—only a few. There were Jews, the “hijackers.”

V.V. Ovsienko: If they were Russian democrats, they were Jews, and if they were true Russians—they were great-power chauvinists. By then, there were probably almost none of them. The Leningrad group of monarchists was imprisoned then.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Ogurtsov was imprisoned with us there. I was even very friendly with him.

I.P. Kovalenko: But you didn't agree on your views, did you?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: We didn't agree at all. But he was a cultured man, had two degrees, you could talk to him about anything, he knew foreign languages. Our Ukrainians hated him fiercely. Once they were beating him, and he said: “Ivan Yefimovich, don't lose heart. We will yet sit together in the Duma.” I said: “We will sit, but only in different...”

V.V. Ovsienko: In different Dumas?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: No, in different corners. We were just joking.

N.B. Kotlyarevska: And were the Ukrainians from the east and the west?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Mostly from the UPA.

I.P. Kovalenko: Tell about your relationship with the UPA.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: They accepted me as one of their own, surrounded me with attention, care, helped me in any way they could. How was I different from the other dissidents? The other dissidents were the high intelligentsia. They looked down on the UPA men. They would take a bunch of books from the library and go to work. They would gather by themselves, talk about high-minded matters, about everything else. But I immediately connected with the common folk. I knew almost all of my poems by heart. So they asked me several times to recite my poems, which they had heard. They would say: “We’re finishing our twenty-year terms and hoping that a new generation will come, that they will tell us something, help us with something, enlighten us in some way. But they pay no attention to us.” But I, on the other hand, read to them almost every evening—they would brew tea, gather around, I would read my poems, and they would sit and cry.

V.V. Ovsienko: And who from the insurgents was there? Can you recall any names?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: I'm telling you, there were two hundred insurgents there. If not more. Myroslav Symchych, who served 32 years...

I.P. Kovalenko: Pidhorodetsky...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes, Vasyl Pidhorodetsky—a man of a noble soul. He served 33 years.

V.V. Ovsienko: He's disabled, isn't he? Is he still alive?

I.P. Kovalenko: Yes. He is still alive, thank God.

V.V. Ovsienko: I'll have to visit him sometime.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Verkholiak...

V.V. Ovsienko: There was one Verkholiak named Yevhen, and the other...

I.Yu. Kovalenko: I don't know, I don't remember. But they were very attentive, friendly people. And what always distinguished the Ukrainians? Their clothes were always tailored, their boots always polished, they were trim, neat. And our intelligentsia immediately let themselves go, walked around all slovenly and greasy.

I.P. Kovalenko: Including you.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Including me.

(((N.B. Kotlyarevska: But they were all in their high-minded matters, that intelligentsia.)))

I.P. Kovalenko: Pidhorodetsky immediately took him in hand: he cut his hair, tailored his uniform, did everything properly and ordered him to always look like that.

N.B. Kotlyarevska: To keep himself up, not to let go, not to lose spirit.

I.P. Kovalenko: It's a certain form of defiance. There, for example, his good friend, Mykola Kots. We correspond with him, we are friends. He was always so untidy. And no matter how they approached him, saying he needed to be different, he would say: “I don’t recognize this.”

I.Yu. Kovalenko: “They threw me in here, and I'm supposed to walk around looking sharp?” We had “external appearance inspections.” Did you have those?

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes, yes.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: They would line us up and walk around, inspecting.

I.P. Kovalenko: Some did not submit. Well, they worked on Ivan Yukhymovych, who is a very neat person in general. That was the mood there.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: They sent me to Kots to tell him that a Ukrainian must always be a Ukrainian, wherever he is. He must be clean, neat, and sharp.

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, look at our Western Ukrainians. They always wear hats. Even the old village men or other men—in hats, they don't wear flat caps or kepis, because they respect themselves.

V.V. Ovsienko: And who from the Ukrainian intelligentsia was in the 35th zone?

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, it must be said that at first, there was this impression that they had sort of separated themselves from those who had fought, and whose hands were elbow-deep in blood. But later they grew closer to the intelligentsia, became friends.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: I was the liaison between the two groups.

V.V. Ovsienko: You were also closer to them in age.

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, that was a different generation. Young, educated people. The information at the time was such that they didn't immediately understand the role of these UPA fighters. Not all of them understood. They were strangers to them. But there, they all became equal.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: They became equal.

V.V. Ovsienko: That's right. From my own experience, I know that we became very close and were very much our own people. I knew several insurgents—they are some of the brightest individuals I have ever known.

I.P. Kovalenko: Wonderful people. Later, they visited us here in Boyarka several times in large groups.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Vasyl Pidhorodetsky was here, Myroslav Symchych was here, but he missed us.

I.P. Kovalenko: Yes, and Ivan Kandyba, but he's not an insurgent. He was also imprisoned there.

V.V. Ovsienko: Who else from the 1972 arrests was with you in the 35th zone?

I.P. Kovalenko: Svitlychny was from the same group, Valeriy Marchenko. Marchenko arrived a little later. Semen Hluzman, Ihor Kalynets, Vasyl Zakharchenko, Yevhen Proniuk, later Zinoviy Antoniuk, Mykola Horbal. Horbal was here with us too.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: At first, they put me on snow clearing, because snow fell right away. But then the doctors examined me and said I couldn't do that. So they sent me to sew bags.

V.V. Ovsienko: Did you meet the quota?

I.P. Kovalenko: No.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: I didn't meet it. When I didn't meet it, everyone helped me. Everyone helped.

I.P. Kovalenko: Comrades.

V.V. Ovsienko: Your profession is “sewing machine operator”?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes.

V.V. Ovsienko: I have that profession too.

N.B. Kotlyarevska: Were you in the same camp the whole time?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: In one. I was also in the hospital.

V.V. Ovsienko: The hospital there is just across the fence.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Have you been there?

V.V. Ovsienko: I've been there too. But at a different time, in 1987 and 1988. They moved us from Kuchino to the 35th zone on December 8, 1987. They assigned us the southern part of the hospital.

I.P. Kovalenko: Well, the hospital is a fond memory. He ended up there with Svitlychny. Well, tell them how you spent your time in the hospital, how you rested, how you wrote poems about each other?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: We wrote poems about each other. To amuse ourselves.

I.P. Kovalenko: For a bit of release.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Yes. Svitlychny was the leader of everyone. They brought everything to him, whatever anyone wrote. For his approval....

V.V. Ovsienko: You were released on the exact day, January 13, 1977, right? And brought here to Kyiv, of course?

I.Yu. Kovalenko: Of course. They wanted to come get me with Symchych's wife, to pick me up. Because Kandyba was released from the camp and got to Moscow on his own, and then lived in Moscow for a week. And then he went to Chernihiv. I was counting on the same. But no: a month in advance, they grabbed me in the terrible cold and took me through five prisons again, on many transports, through many transit points... I arrived, had no medicine, I arrived as a second-group invalid due to blood pressure. I had grown a beard down to my waist. They brought me to the KGB in Kyiv.

I.P. Kovalenko: Tell them that at first they gave me permission to go and pick you up.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: But in reality, they were carting me around prisons in such cold, especially in the Kharkiv prison, where there was no mattress, nothing. I sat there in the clothes I had on.

When I came home, I wasn't myself, because of the terrible blood pressure, the illness. At the KGB, the head of the Kyiv-Sviatoshyn district KGB spoke with me for two days. He gave me a “prophylactic talk.” I said: “But you won't register me to live in Kyiv or the Kyiv region.” “We will, we will. Just sit quietly and don't do anything, don't have acquaintances visiting you, don't prepare anything.”

To get a pension? I had long since earned it and served my time. They wouldn't give it to me. Why? Because I hadn't been fired from my job. They arrested me, but didn't fire me from my job. For two years, I fought to get them to fire me. So there would be a record that I was fired. And only after two years did I start receiving that measly pension.

I.P. Kovalenko: A whole 57 rubles.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: I didn't receive any help from anywhere, I didn't apply for rehabilitation. It was the students, without me...

I.P. Kovalenko: Let's be more precise: some fund helped—wasn't it the Solzhenitsyn Fund? Through Yulia Oleksandrivna Pervova, from time to time, he received 50 rubles. She was connected with Moscow, with the Solzhenitsyn Fund. We don't know what channels that money came through, it just arrived from time to time, 50 rubles, through her.

I.Yu. Kovalenko: We don't know for sure. Until they assigned the pension. Then I refused any help whatsoever. In the camp, when I taught many Jews English, they told me: “We will send you a parcel, a money order.” I refused. I knew that you have to pay for everything you receive from someone. That's why I refused and came out completely clean. While others happily accepted their handouts, I did not. The KGB persecuted me a lot there for communicating with Jews, for teaching them English. They were planning to go to Israel.

Gradually, I began to recover. It took me two years to recover, then I started to work a little around the house. Many of my fellow inmates visited me. Vasyl Pidhorodetsky was here, Mykola Horbal was here, Rudenko's wife, Raisa, was here, Proniuk's wife, Halyna Didkivska, was here earlier.

I.P. Kovalenko: Such a lovely woman!

V.V. Ovsienko: Did Vira Lisova not visit?

I.P. Kovalenko: No. I used to visit her.

N.B. Kotlyarevska: Was Nina Marchenko here?