For the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group

Audio fragment of an interview with Opanas Zalyvakha mp3-file (1279.817 kb)

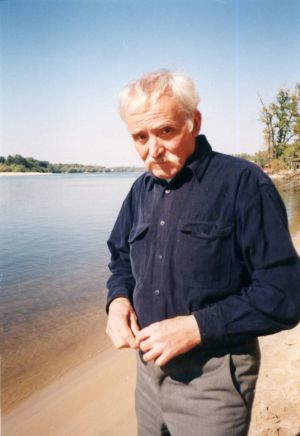

V. V. Ovsienko: This conversation is taking place in Hydropark in Kyiv on September 20, 1999.

Mr. Panas, on what occasion have you come to Kyiv from your Ivano-Frankivsk?

O. I. Zalyvakha: Yesterday was the seventieth birthday of my friends who are no longer with us—Ivan Svitlychny (Note: 20.09.1929 – 25.10.1992) and Alla Horska (Note: 18.09.1929 – 28.11.1970). I first received an invitation to their seventieth anniversary in 1964. It was sent to me then by the CYuK (Central Jubilee Committee), headed by Viacheslav Chornovil (Note: 24.12.1937 – 25.03.1999). And now, the same invitation was enclosed in the envelope, only larger—like a poster. Something prevented me from coming then, but I came this time. At that first seventieth, they were 70 combined, meaning 35 each—for Ivan and Alla... And now, they would each be 70. I am pleased that these are no longer the times when they were breathing down our necks, dispersing us, persecuting us, asking: where did you gather? what is this CYuK?

Although this is now my fifth day in Kyiv, I have only heard the Ukrainian language on the streets about ten times. This surprised me—a kind of indifference of Ukrainians to themselves. We have, as they say, “come full circle”: Ukraine is under surveillance, in a hostile environment—it has its internal oppressors, and it has external ones.

But I was pleasantly surprised that in Kyiv, there is a Ukrainian national spirit not only in the older generation but also in our elite youth. Although it was strange to me that we gathered in such a small hall of the Society of the Repressed—there were maybe fifty people. Like in the catacombs. A gathering of Ukrainian-minded people could have been held in a large hall.

In those days, I used to come to Kyiv quite often. I grew up outside of Ukraine. When I returned to Ukraine, the first thing I had to do, of course, was to get to know Kyiv. A republican exhibition was being held in Kyiv. I brought a small mosaic of mine there. It depicted a horse, and next to the horse stood a woman handing a saber to a Cossack. Of course, the work was rejected—they said I had to paint over the text “Boritesia—poborete!” I was somewhat surprised. Later, in the workshop of Liudochka Semykina, I got to know the Ukrainian artistic world. A world that was interested specifically in what was Ukrainian. Not socialist realism, but those artists who think in Ukrainian, who see a Ukrainian worldview, who understand Ukrainian aesthetics.

I would be in Frankivsk for a week or two or three, and the rest of the time I spent in Kyiv, painting here in Alla Horska’s studio. She always told me: “Paint, Panas, think here, read books.” I was just entering the Ukrainian milieu when I returned to Ukraine in 1961. It was Ivan Svitlychny who primarily set me on the Ukrainian path back then. When I visited him, he would say: “Panas, take a look at this book, this one, this one...” That’s how I began to align myself with the Ukrainian dimensions of public and cultural life. I had lived in Russia for over 30 years, had forgotten many Ukrainian words, or never knew them at all. So I walked around with a piece of paper, writing down unfamiliar words, learning the Ukrainian language. In Alla Horska’s workshop, it was Nadiyka Svitlychna who taught us Ukrainian. I remember that—I was the oldest in that group. I was 35, Liudochka Semykina was also 35 (I only recently found out she’s the same age as me), and others were 30, 25. We sat on the floor, and Nadiyka read us a dictation in Ukrainian. We wrote.

V. V. Ovsienko: So there was a whole class?

O. I. Zalyvakha: About ten people. Halia Sevruk was there... Nadiyka dictated to us like a language professor, and we wrote. Of course, this prompted us to be vigilant about language, to avoid the surzhyk that is so prevalent in Kyiv now. I first encountered the language issue in “Literaturna Ukraina” around 1966. It was an open letter from Maksym Rylsky (he died in 1964) to Konstantin Paustovsky and Paustovsky's reply to Rylsky. Someone in Kyiv gave me this newspaper. It was interesting that Rylsky reproached Paustovsky for leaving Ukraine and the Ukrainian language—despite being from an old Cossack family—and switching to Russian. Paustovsky replied that in Kyiv, you could only hear Ukrainian at the Besarabsky Market, and from everyone else—you wouldn't hear Ukrainian in Kyiv. Sometimes someone would come from Canada or America—people who spoke Ukrainian. That was their verbal duel. Because of the language issue, they started to watch me when I arrived in Frankivsk (it was still Stanislav then).

I put on a small exhibition in the local history museum—it was closed down after a week. I had placed a guest book there for comments. A debate started on its pages: “Oh, finally we see Ukrainian painting! This artist paints for himself, this isn’t socialist realism.” There was a teahouse scene where I depicted a person in ski pants with skis, and another Hutsul walking by with shoes made from car tire rubber, cobbled together with pieces of iron. A woman in an apron stands in the doorway of the teahouse, while locals and tourists pass by. They told me: “Is this a painting? What is it calling for? Nothing is clear here. It’s neither aesthetics nor politics, just a caricature of our reality.” I explained that it’s a contrast, you see: this one has come to go skiing, and this one is cutting down the Carpathian forest. They shut down that exhibition. A man from the regional party committee, from the third department for culture, came and said: “I'm taking this guest book from you, we need to study it.” I said: “I won’t give it to you. It’s my notebook, I put it there.” “But, you know, there are some very negative entries in it.” “I’ll sort it out myself.” So it remained with me. Later, it ended up with the KGB: when my place was searched, it was confiscated as one of the pieces of incriminating evidence for my sentence.

Oh, I also designed a display window for an art salon in Frankivsk. I put Hutsul ceramics in it—the background was ultramarine or Parisian blue. I made some shelves—and the window became decorative, it started to catch the eye. People began to stop in front of the window, they would come in and ask: what is this, who made this? At that time, I was in Vorokhta; Mykhailo Figol from Leningrad had invited me. He said: “Come visit us, Panas.” Figol and I were painting there in Vorokhta. A phone call: “Zalyvakha—get to Frankivsk immediately, there’s an issue with your window display.” Two hours later—another call: “You don’t have to come.” I later found out that the KGB had seen people stopping by the window and entering the store, so they took the display for expert analysis. They studied the combination of yellow and blue and determined that it wasn't a light blue color but Prussian blue with ultramarine, as well as cadmium yellow. They said it wasn't suitable—it wasn't the right tonality. But they made such a fuss. The window display, however, was not allowed to be restored—they just dismantled it.

That got me interested: why are they so particular about colors here in Frankivsk? Because I just painted as my soul prompted. But it turned out that one shouldn't paint things as they are, in symbols, but according to party requirements: more red, more uplifting tones—to call people to something. And when a color reminds you of something and evokes certain reminiscences—there was an organization for that, which checked everything. It wasn't an art council, but something like a taboo, a censor. In the annotations of books, it had the letters BF and some initial numbers. That's gone now. Now there is supposed independence, you can use any colors on a canvas in any way, but many artists are at a loss—what to paint? You can use any color for anything! Before, there was an art council, they would look and say: it needs to be painted so the foreground is brighter, “Your perspective combination here isn’t quite clear, this needs to be finished—please finish it.” Now there are no socialist realist directives, no censorship—it's “summertime.”

V. V. Ovsienko: And it became difficult to create?

O. I. Zalyvakha: And some artists were at a loss: what should we do? Before, the line was clear and distinct—this way and that way, this is progressive, this is a positive hero, and this is a negative one, here’s the foreground, the background. I remember, I first encountered this when I was studying in Leningrad. An artist kept submitting his painting to the exhibition's art council. The art council kept rejecting it, saying: “Your subject matter isn’t quite vivid enough.” He had clearly defined it: this is a woman, this is her son, this is something else. He brings it a second time—they say: “Alright, this could work, but you have no perspective, you need to create perspective.” He established a perspective—a foreground, middle ground, and background. He brings it a third time—they say: “Well now, that’s better, but your texture is all wrong, these brushstrokes don’t follow the form, they’re deconstructive, you need to make it as it is in nature, in reality.” They wore him out psychologically. He saw that they were going to “fail” him. He came one last time: he had painted a blue dog in the foreground. He brought it in, set it up, and everyone looked at it: “Good, everything is good—but where have you ever seen a blue dog? Is that even a dog? Really! The rest is all good, but the color is wrong.” But what he had done was he had glued a blue dog onto the canvas. So he ripped the dog off, touched up the spot where it had been glued, and said: “You said it was good, but the dog was bad. So, I’ve removed the dog.” “Well, fine then!”

V. V. Ovsienko: And what was left?

O. I. Zalyvakha: What was left was what was there before, only he had removed the blue dog.

I go to exhibitions in Lviv, in Kyiv. Many booklets and monographs on Ukrainian artists are published now. And I am reminded that when Mexico became independent, national artists appeared in Mexican art, freed from that colonial status—Rivera, Siqueiros, and others. A wave of Mexican monumental art emerged. After some time, Siqueiros was sent as an ambassador to France... Architecture, large walls were painted (quebracho—that's their Mexican technique). The Mexican style was revived—not the colonial, Spanish one. I compare that period in Mexico to Ukraine. Here, Ukraine has become “independent.” There is no art council, but there is also no Ukrainian art yet, no architecture. Neither in Kyiv nor in Kharkiv can one see a revival of Ukrainian spirituality. It seems a lot is being built, but there is very little Ukrainian in it. Evidently, there are some forces that are hindering the development of Ukrainian spirituality. I remember, once we had one newspaper, “Prykarpatska Pravda”—the organ of the regional committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. Now dozens of newspapers have appeared—with small circulations. Ukrainians work at the newspaper “Halychyna.” “Prykarpatska Pravda” was communist, it's been slightly repainted, but it’s the same. Ukrainian bookstores have very few Ukrainian books; that is, they exist, they are still written in Ukrainian, but their content is somehow provincial, post-Soviet.

I recall meeting a man named Ivan Vyrhan in 1963. He was a poet who had been in the camps. He came on a business trip to Ivano-Frankivsk, to Western Ukraine, to give lectures on Ukrainian literature. And I knew this Vyrhan from my time in Tyumen. His daughter, Natalka, studied with me in Leningrad. I wrote him a letter then, saying that while I was in Tobolsk in 1959 or 1960, I went to the cemetery to see the culture there, the tradition, and I saw Ryleyev's tombstone with a cross. I look—next to it is Pavlo Hrabovsky’s grave, with a small plaque: “Ukrainian poet,” and something else written there. Ryleyev's grave had a metal fence, but Hrabovsky's was overgrown with nettles, with a small wooden cross, I think. I went to the local history museum in Tobolsk, asked about Hrabovsky, and they told me: “Yes, your Ukrainian poet was here in exile.” I wrote to the Writers’ Union (the chairman at the time was the playwright Oleksandr Korniychuk) that the grave of our writer was in such a state. They didn't reply. So Ivan Vyrhan answered me: “Thank you for your concern about Hrabovsky, but we can't do anything. Write to the Writers' Union of Ukraine.”

While still studying at the Repin Art Institute in Leningrad (formerly the USSR Academy of Arts), I intended to come to Ukraine. The impetus for realizing who was who was this incident. I entered this institute after the Secondary Art School in 1946. In 1947, I was expelled “for conduct unbecoming of a Soviet student.” I was later reinstated. The boys and girls were ten years younger than me. I look, and there are two other guys in the course who are ten years older. But that’s not the point. That Minasovetisyan—he felt his Armenianness even more passionately than Saryan. There were Czechs, Poles, Germans, Chinese. And one day a Czech girl, Vlasta, asks: “Panas, what is your nationality, what is your art, what is your culture? Look, we Czechs think this way, the Albanians that way... And you, Panas, where are you from? Are you Russian?” I thought about it: who am I? And I say: “No, I’m Ukrainian.” “Well, what can you say about what’s Ukrainian?” And I knew nothing. That turned me upside down, and I began to search for my roots. Because I was just... a floater. A sovok.

Later, when I was finishing my studies, I had my practical training first in Lviv, and then I went to Hutsulshchyna. I went with the graphic artists, not the painters. Our team arrived in Kosiv. We lived there in the dormitory of the Kosiv Art College. There were students from the Lviv Polygraphic or Art Institute. For the first time, I saw Hutsul Ukrainian life. I went to the market. At that time, some people still wore postoly, some women smoked pipes. There were such Ukrainian colors, like at the Sorochyntsi Fair—I had once read about it in Gogol. I stared at those people, thinking: look how much I’ve lost! I was torn away, like a leaf. Once, there were girls on the bank of the Rybnytsia River. One of them used to come to our dormitory. We got acquainted. It was Olena Antoniv (Note: 17.11.1937 – 02.02.1986)—the future wife of Viacheslav Chornovil. I became friends with her, we went swimming together. A slender, beautiful girl. I was so captivated, I thought: no way would I try to flirt with her. She was somehow unattainable. We were sitting by the Bystrytsia once, and she says: “You know, Panas, we recently had a trial. We were tried for being Ukrainians.” Later, from Leningrad, when the training period ended, I started corresponding with her.

So, I saw some imaginary and real image of Ukraine in Halychyna. Ukraine attracted me. When I came to live in Frankivsk after Tyumen, the “organs” asked me: “And why did you come specifically to Ivano-Frankivsk, to Stanislav? You’re from Kharkiv region by birth, and you lived in the Far East. Who sent you here to Western Ukraine?” That surprised me, I thought: what a strange thing. And I say: “Some warm Ukrainian wave inside me sent me here. And who sent you here?” “Well, how? I like it here, it’s good. I’m a Siberian myself.” “And why don’t you want to love your own homeland?” “Well, you see, why are you asking me such questions?” “I’d just like to know who you are.” Interesting, isn’t it?

I have two brothers left in the Far East—Vasyl and Mykola. My little sister Varia lives near Moscow. I correspond with them. From Leningrad, I wrote to them in Russian—just as they wrote to me. Since I have learned Ukrainian quite well, in my opinion, I correspond with them in Ukrainian. I sent Ukrainian books to my brother Mykola in the Far East—Stefanyk, others that seemed to me truly Ukrainian, of a high artistic level. Mykola writes to me in Russian: “You know, brother, don’t send me Ukrainian books, because I read them, then I go to my classes, and Ukrainian words slip out.” This somehow surprised me: he is ashamed that he can’t speak either pure Russian or pure Ukrainian. He spoke that surzhyk. Later, however, he visited me in Frankivsk after I had married there. He said, “Forgive me, but I will speak in Russian. I’ve forgotten how to speak Ukrainian.” And Mykola and Vasyl were the same.

But they preserved the memory of our family, especially the eldest, Vasyl. I accompanied him to our homeland, in Kharkiv region. He showed me the place where I was born. Where our house stood. We moved from there later, father bought a bigger house. But in 1933, there was a terrible famine. I remember, I went to a nursery then. I walk down the street to the nursery—it's about five hundred meters. Fences, and under the fences, people. Some are sitting, some are lying, some are stirring. I come back from the nursery, I look—those people are already lying down, no longer stirring. We lived on the outskirts of the village, and across a ravine was the cemetery. One time I went into that ravine, climbed a little higher. The rye was golden, like waves. I thought, I hope I don’t drown here. I walked along the stubble past that cliff, climbed up to the pasture. I look—black earth. And people brought something in a blanket and threw it into a pit. I got closer, thinking: “People are carrying something. What are they carrying?” I came even closer, and I see a fairly large pit dug. Not for one person. And corpses were thrown into it. The people had left, apparently to get someone else. I got scared. I ran home. I later found out that they were clearing the dead from the village and dumping them there.

One time my parents were in the fields, threshing grain. They left me at home. “Don’t,” they said, “let anyone into the house.” We didn’t have locks, of course, only latches on the inside, and a peg was stuck in from the outside. One day I was in the little house. I hear a tapping on the windowpane, sounds like a violin, some kind of sawing sound. I went over, stood on my tiptoes, looked out the window—an old man was standing on the threshold. He wore some kind of overcoat, a straw hat, a bag. And a little boy was with him. And he was turning a crank. I later found out it was a lira. We called it a lirva. He turned it, his fingers moving over it. I listened to it. I don’t remember if I found them a potato or something—it’s all a blur to me. They stood there for a while and then walked on, hobbled away. That was the first time I heard Ukrainian music, right on my own doorstep.

V. V. Ovsienko: And what is your village called?

O. I. Zalyvakha: The village of Husynka. Kupiansk district, in Kharkiv region.

V. V. Ovsienko: You came into God’s world on November 26, 1925?

O. I. Zalyvakha: You know, it’s interesting. They recorded that date for me when we arrived in the Far East, when I had grown up a bit... At the military enlistment office, as a pre-conscript, they stripped me, examined me, and established that date. By the way, we traveled to the Far East from Husynka for quite a long time. But why did we leave Ukraine? It seems to me it was in the hungry year of thirty-three, in the autumn. They wouldn’t let us out of the village, of course. I watched my father make two double-family beehives for the village authorities. I remember how he planed the wood, how the shavings and glue smelled. It was all interesting to me. He made those hives, gave them to the authorities, and they let us go. People gathered in the house (I remember it as if it were yesterday, I was on the stove, peeking out from behind the chimney). The adults were having a drink, a kerosene lamp was burning. They sang a few songs. We were given a wagon, we all piled in—me, Mykola, and Vira—and we went to the station. It was about four kilometers from the village. There we waited for the train and—off we went!

We traveled to the Far East for thirty-one days. We were on a train they called the “Maxim Gorky.” There was a long stop in Irkutsk, maybe a day, or however long that echelon stood there. Two other families from Ukraine were traveling in our train car. It was there that I first went out with my mother. Or with my father. We went to see the city. We came to the bridge over the Angara. It was winter, cold, freezing—and steam was rising from the bridge. I was surprised that steam was coming from the river in winter. That stuck in my memory. There was some kind of cafeteria or something there. And my mother says: “Go in there, ask for some food, say: for Christ’s sake.” I felt so awkward asking, but my mother told me to, so I had to do it. And so I went from table to table: “Give me a piece of bread for Christ’s sake.” I had to beg like that more than once after that.

We reached the Far East. Our relatives were at the Shetukhe station. They had moved there—I later found out—during the Stolypin reform. They traveled via Odesa, through Singapore, landed in Vladivostok, and settled in Shetukhe—it's about a hundred kilometers from the railway. Their surname was also Zalyvakha. If we had arrived in Shetukhe, we were supposed to go to them. We got off the train car, my father asked some people for a couple of boards, made a small sled, my parents put their bag on it, and we set off. We walked and walked—along a snow-covered forest road—and reached a village. They let us spend the night there. I came down with pneumonia, I lay there on a bench, dying. A man, they called them “khodia” there, a Chinese man, was passing through the village, and they called him—maybe he could help, because a child was dying. He helped. When I later opened my eyes—I remember his narrow brown eyes and his smile. The Chinese man went on into the forest for ginseng, and we stayed in that village.

Later, when I was in a camp in Mordovia, there was a census. A captain was recording my information. He asks my nationality. I say: “Put me down as Chinese.” “Why?” “You know, a Chinese man saved my life.” “Well no, I can’t put you down as Chinese. As a Russian—please.” “Well, if I can’t be Chinese, then put me down as Ukrainian.” That’s how I became a Ukrainian.

I remember, in that village, the neighbors asked: “And who are you?” “We’ve come from Ukraine.” They brought us food: fish, frozen potatoes, a bowl of chum salmon roe, some other things. I later asked, when I was an adult, where they got the roe. And they had half a barrel of chum salmon roe. “Oh,” they said, “we go into the river, take the roe, and throw the fish away.” It’s gone now. I was recently in the Far East, and there they only caught chum salmon for the authorities. On this side, and the other side of the river was Chinese. There was a demarcation line, they caught their own.

V. V. Ovsienko: So which village did you stop in?

O. I. Zalyvakha: We stopped in the village of Pavlo-Fedorivka. This is the Ussuri region. Later we moved to the town of Lisozavodsk on the Ussuri River. My father worked as a carpenter and a blacksmith there. I finished seven grades there and was in the eighth grade. When I was in the eighth grade, and my father was working in the smithy, he was walking home one day and saw a colorful sheet of paper on the road. He picked it up, looked at it—he must have had some talent for visual observation. He looked, and there it said “Rules for admission to the art school.” He brought it home and said: “Take a look, maybe for you...” And I was already drawing a little then. I read it, and I see addresses of art schools, there was the Moscow Art School, an address. I wrote a letter, and after some time I received a reply from Moscow with a booklet, saying there are such and such schools, Blagoveshchenskoye, Irkutskoye, Samarkandskoye. I looked—the closest to us was the Blagoveshchensk Art School. I finished the eighth grade and said: I’m going there. They got me ready...

V. V. Ovsienko: What year was this?

O. I. Zalyvakha: When the war started, in forty-one. I remember, I went “to the other side,” as we used to say, of the Ussuri for bread. Because the lines there formed in the evening, and the bread was delivered in the morning. I'm standing in line, and they say: war with Germany.

V. V. Ovsienko: You were in your sixteenth year...

O. I. Zalyvakha: And so, people are saying: “Oh, we’ll get them in a couple of months...” And there was an old man there who says: “No, it's the Germans,”—a Ukrainian, he spoke Ukrainian.—“When I fought the Germans—in some year, fourteen or whenever—it’s not so simple.” I come home and say: there’s a war, they’re talking about it in the line.

I went to Blagoveshchensk. My mother gave me a pot. “This,” she says, “is for your father, bring him lunch in Ruzhyno.” That’s a couple of kilometers from Lisozavodsk. So I said goodbye to my mother by the garden and left. I never saw my mother again. Her maiden name was Pashchenko, Yevfrosyniia Zakharivna. They called her Priska. She died at a young age. She was about—I later found out that was a young age—thirty-eight years old. She died around forty-three. I don’t know for sure—look at that, I’m even ashamed.

V. V. Ovsienko: And your father? Please tell us, on this occasion.

O. I. Zalyvakha: And my father—Ivan Mykhailovych Zalyvakha. Our nickname, as I was told later, was Baly. On our street, we were called the Balys—Balenky, Balo, Grandpa Balo. When I started to think, I wondered about our lineage, who we were and where we came from. So Vasyl, my older brother, took me to the homestead where Grandpa Mykhailo once lived and told me that he was a master craftsman. They built windmills, churches—they traveled around Ukraine and built windmills. He earned some money, left his crew, and bought a desiatyna or two of land. There was some kind of shack there. He settled down, got married. This Zalyvakha line came from Husynka, but where it truly originated is unknown, because my grandfather was a wandering craftsman. I later calculated by the years that our family had not been enserfed—they were wandering craftsmen. And that comforted me, that we weren't serfs...

V. V. Ovsienko: You left off at saying goodbye to your mother and leaving.

O. I. Zalyvakha: I went to Blagoveshchensk. And the war had already been going on for three months, or however long, and the school administration says: “You know, for now we’re harvesting bread, we need to...” And they sent us, the students who had enrolled in the school, to the fields to gather the harvest. When we finished, the administration says: “You know, there’s a war—the school is closing. Whoever wants to study can go—there’s another school like this in Irkutsk. Whoever doesn’t want to can go back home.”

I went to Irkutsk. They transferred me, I didn’t have to take any exams there. I studied there for about two years, and one boy says: “Panas, you know,”—he spoke Russian, a Tatar named Ibragimov, with blue eyes—“you know,” he says, “Panas, let’s go to Samarkand. I found out there’s an art school there attached to the Academy of Arts. Let’s go there! What is there to do here, in Irkutsk?” And so—off we went to Samarkand.

We arrived in Samarkand—the Russian Academy of Arts had been evacuated there. We both enrolled there, in that secondary art school. After some time, the art school—the war was coming to an end, it was forty-five—was put on an echelon and off we went!—transported to the west. They brought us first to Zagorsk, near Moscow. That's the center of the Russian Orthodox Church. I studied in that school for a while, in the monastery buildings. I was already going to Moscow with the boys, we went to see the Tretyakov Gallery. The electric train ran between Zagorsk and Moscow then. Then the Academy was moved to Leningrad. We arrived there—the war was still on, but already in the Baltics. We boys were in a boarding school at the Academy. There were several rooms there. We ran around, rummaging through the Academy. After the war, papers were lying around. Well, for kids, that’s interesting. One time we were running around, and on the side—it’s a huge building between Third and Fourth Lines—a huge hole, about three meters wide, was punched through the main outer wall. They explained that a shell had hit it. I later found out that the shell had hit the very wall behind which was Shevchenko's studio. It was later repaired, and even later a small museum for Taras Hryhorovych was organized—people visit it now. But back then, there was a big hole.

I finished the secondary art school and entered the first year of the Academy of Arts. That was in 1946. In 1947, there were elections to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. I and a few other boys weren't at the meeting with the admiral who was being nominated as a candidate. They “took note of us” and said: “We are expelling you because you are boycotting the elections to the Supreme Soviet.” I was expelled “for conduct unbecoming of a Soviet student” in forty-seven.

I went to the director, had a talk. His name was Zaitsev, he was from Blagoveshchensk himself. He says: “You know what—go work, get a good character reference, then we’ll talk about reinstatement. Because it's known at the regional committee that students here...”

Well, alright, I went to a construction site, worked in a brigade under the Stalin Prize laureate Kulikov. As a bricklayer. I laid bricks. I was good at it. Sometimes this Kulikov, as a laureate, would go to some events, and he would say, you, Panas, take charge here. Well, I laid about six thousand bricks per shift, just like him. They wrote me a good character reference. I went to the director's office, showed them the reference. They looked at it and said: “No, this won’t work, maybe after Stalin’s death.”

V. V. Ovsienko: They said that directly?

O. I. Zalyvakha: Well, they didn’t say “after Stalin’s death,” but “in our time, this won’t work.” I see that no character reference is helping. I think, I need to get some artistic profession, which I have a bit of an inclination for. There was an art and pedagogical college in Leningrad. I finished it, received a certificate as a “teacher of drawing and drafting.” I see that I won't be reinstated at the Academy. I went to Kaliningrad, the former Königsberg. I worked there for a year in the Art Fund. Then a friend of mine from the secondary art school came to see me and said: “Panas, there’s a chance to be reinstated.” I went to Leningrad. I had to show a few paintings, a drawing... I did that, and in 1955 they reinstated me in the second year. I graduated from the institute in 1960. So it turned out that my diploma says: “Enrolled in 1946, graduated in 1960.” It’s a unique diploma, could be a museum exhibit. I studied for 14 years!

Well, after the academy, you have to get on your feet. And for job placement, there were various points in the USSR. I saw that in Tyumen they were offering a studio and promising housing as a second step. I decided to go to Tyumen, get a bit stronger, maybe become a member of the Union of Artists, and then go to Ukraine.

I spent a year in Tyumen, I see—nothing’s coming of it. There was a solo exhibition, but membership in the Union—that was careerism, I didn’t understand much about it. Sometime in December, I checked out. They had already given me a one-room apartment—a studio. Shyp Ostap, as I called him (because his name was Vinen), who graduated from the academy with me, says: “Panas, you’re going to Ukraine, and there’s a guy here who works as a molder, married, with two kids, and he lives in a former monastery, in a cell. Give him the apartment.” I say: “Alright.” I threw a farewell party, bought some dry wine. They had given me a samovar for my birthday, so I poured that wine into the samovar, set out glasses. Girls from “Tyumenskaya Pravda,” journalists, artists came. I got out that warrant and wrote that I was leaving the apartment to the man with many children, that I didn’t need that apartment anymore. And all of us, about ten people, signed it—employees of the Tyumen newspaper, artists. I gave him the warrant, left him five hundred rubles, and said: here, send me my trunk with this. And I left my bicycle there too. He sent my things to me in Frankivsk.

I left, checked out. I arrived in Moscow—it was already late, night, I thought I’d spend the night in a hotel, and then catch the train to Kyiv tomorrow. I go to the hotel, and she takes my passport and looks: “But you’re checked out, we can’t let you stay the night.” She says: “You can go to the agricultural exhibition, they have rooms there where you can spend the night without registration.” Because people passing through go there...

V. V. Ovsienko: ...villagers, who don't have passports.

O. I. Zalyvakha: I went to that agricultural exhibition, I give my passport and say: “I’d like to spend the night here.” They say: “But you’re checked out, we can’t.” I spent the night at the train station. I thought: so this is Russia. I arrived in Kyiv, from Kyiv—to Frankivsk, here—Figol. I stayed with him. And here this whole unraveling of mine began...

Three and a half years later, they come to me: “There's a telegram for you.” By that time, they had given me a one-room apartment. True, I wasn't registered yet, I hadn't had time, it had been about a month, I was planning to submit my passport for registration... I was in my underpants. They bring me a telegram. I get up, open the door, reach out my hand for the telegram, and I see—a boot in the doorway, military men in uniform entering the house. I say: “Wait, I’m undressed.” And I try to close it. “No-no-no, you can get dressed later, we’ll turn away.” This was in 1965, on August 28. They came in and said: “We’re conducting a search. Do you have anything anti-Soviet? Give it all to us, or we’ll conduct a search.” I say: “I don’t have anything anti-Soviet.” “We’re going to search.” I say: “Go ahead.” They showed a warrant. An hour later, the doorbell rings. I go to open it—“No-no, we’ll get it.” Ivan Oleksiyovych Svitlychny walks in!

V. V. Ovsienko: He arrived right during the search!

O. I. Zalyvakha: He says: “Oh, oh, how lucky we are today.” I say: “Ivan, I’ll put on some tea.” Well, an honored, dear guest. “No-no, let’s get down to business.” They finished the search, led us out to the “bobiks”—me in one, Ivan in the other, and drove us away. We said goodbye, Ivan says: “Hold on, Panas.” And so I was taken to the KPZ. I was in the KPZ for three days. They say: “Confess to everything and you can go. You locked your house—what about the keys? All your works are in there.”

V. V. Ovsienko: And what did they take from you?

O. I. Zalyvakha: They took a microfilm with Avtorkhanov’s book, something about Soviet power (Note: Abdurakhman Avtorkhanov’s work “The Technology of Power” was circulating in samvydav at the time). There were some interesting informers in the cell, asking about Horska, Svitlychny. The investigator: “And why did you bring and distribute such and such articles, we have data—you took and brought them. So, are we sending you to prison or not?” I say: “As you wish, that’s your business.”

I had an interesting dream back in the KPZ. It was as if I was in Kosiv, crossing the Huk stream on stones. I’m standing on a stone, wanting to get to the other bank, and the water is gushing. I think: Panas, you have to hold on, you have to hold on. And I turned a little in the opposite direction from the pressure... I remembered what was in the dream. I think: I have to endure. Later, I remembered how Svitlychny said: “Hold on, Panas.” And during the interrogations—it was long and tedious—I received a compliment from the investigator: “You know, Panas, it’s interesting to talk to you. But you don’t answer the questions directly. You divert somewhere else, into lyricism, into some other imagery, and you don’t directly address the question posed.” I say: “Well, you can look directly at a point, or you can look a little to the side, and then to that side and over there, to see more broadly, to embrace the phenomenon, the environment.” The investigation was extended, then there was a trial. They brought a tape recorder to the trial, something else.

V. V. Ovsienko: Were you tried alone or in a group?

O. I. Zalyvakha: I was tried alone.

V. V. Ovsienko: And you don’t remember the dates of the trial?

O. I. Zalyvakha: I don’t remember the dates (Note: The Lviv Regional Court heard the case of P. Zalyvakha on charges of conducting anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda in March 1966).

V. V. Ovsienko: And who conducted the investigation, who presided over the trial?

O. I. Zalyvakha: Something like... It’s already faded. Khoroshun—there was such an investigator. Then, it seems, there was Kozakov and Khromyi for a bit. He conducted Svitlychny’s investigation too. He spoke Ukrainian. Once, this Khoroshun even brought a watermelon and treated me. They were buttering me up like that. Well, and the verdict—five years in a strict-regime camp under Article 62, part 1.

V. V. Ovsienko: What specifically was in the verdict? By the way, do you still have the verdict?

O. I. Zalyvakha: No, no. It was for possession and distribution of anti-Soviet documents. Besides the Avtorkhanov microfilm, they also confiscated several other articles from me... I had notebooks where I wrote down things that interested me—either plots or sayings. And there was one poem by Shevchenko. I told them it was a Shevchenko poem. Well, he says, we'll check. They sent it for expert analysis to Lviv. The verdict states: “A poem by an unknown author of anti-Soviet content.”

V. V. Ovsienko: And that went into the verdict? Interesting. And you said you were acquainted with Ivan Svitlychny, he arrived right at your arrest...

O. I. Zalyvakha: He was arrested then too, he served, I think, six months, and then he was released. (Note: The detained I. Svitlychny was taken to Kyiv, where he was arrested on August 30, 1965, and a case was initiated against him under Part 1 of Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR; on April 30, 1966, he was released as “socially not dangerous”).

V. V. Ovsienko: This arrest seems to come out of nowhere for you. But you had extensive contact with the circle of people now known as the Sixtiers, didn’t you? Tell us, who were you acquainted with, what were your relationships with these people?

O. I. Zalyvakha: When I came from Tyumen to Frankivsk, there was a Kyiv republican exhibition. I took a small mosaic there—a woman standing and a Cossack accepting a saber from her. It had the words: “Boritesia—poborete.” I took it to Kyiv, wanted to submit it to the exhibition. But it didn't pass, they rejected my mosaic. There I met the artist Veniamin Kushnir, and later worked in his studio. I met the artist Alla Horska, and later—Ivan Svitlychny, Ivan Dziuba.

I went with the late Erast Biniashevsky to see Ivan Dziuba, who was in the hospital at the time. We came to the garden at the polyclinic—a table piled with books by Lesia Ukrainka. Ivan Dziuba was sitting there. He had a lung condition then. We met there. He said he was writing an article about Lesia Ukrainka. I was amazed: such a pile of books! Maybe forty books on the table. And he wrote a small article. I thought, how a person must work to wash the ore and produce pure gold. I still have that article, the KGB didn’t take it.

One time we were near the exhibition hall and Kushnir says: “Oh, now I’ll introduce you to Drach.” Opposite the pavilion was some kind of buffet. Ivan says: “Oh, you’ve come from Halychyna, I wanted to treat you.” He got some beer or something. And I looked at a Ukrainian poet, a real, contemporary one. That's how I met this group of Ukrainian youth. They were all younger than me. I went caroling with them. Iryna Zhylenko or Alla would write to me about when it would start and invite me to come.

That’s how I entered this Kyiv circle. Often, I felt more at home here in Kyiv than in Frankivsk. Because in Frankivsk I was only officially employed, but Kyiv—that was my spiritual place of rest and work. The KGB later asked me why I socialized more with writers than with artists—with Dziuba, with Sverstiuk. You have colleagues in your own field. I said: “You know, I lived in Russia for so many years—I’m studying the Ukrainian language, studying Ukrainian literature. I want to know what Ukraine is, because I grew up in Russia, in the Far East. I want to know my people, myself, to become a Ukrainian.”

V. V. Ovsienko: And when you came to Kyiv, who did you stay with?

O. I. Zalyvakha: I stayed either in Alla’s studio on Filatova Street or with the Svitlychnys. They lived on Umanska Street then. Ivan would coach me, like a singer’s voice: “Panas, read this, read that.” And I began to acquire a taste for it. I may have had that taste for literature earlier, because I remember reading all of Dostoevsky in Leningrad—I went to the academic library, read his “Crime and Punishment,” his diaries—it was an academic edition from the publisher Marx. After Dostoevsky, I couldn’t read anything for a long time—whatever you picked up, you’d think: is this really literature? I already had such a taste that this—is a real thing, and this—is just verbal chaff. And in Kyiv, I immersed myself in the Ukrainian essence—where is it, the core of that Ukrainianness? Especially when an artist thinks, how can one not contemplate who we are, where we come from, and where we are going? At that time, the Moscow institute was named after Surikov, and the Leningrad one after Repin—in Russia, they sometimes called him “Pererepenko.” And you think: what is Ukraine, where is it? That socialist realism—it completely diverted art from its national essence. This greatly troubled Alla Horska too. We walked together, thought together—how, what, that flatness, decorativeness, symbolism... It wasn't that Shishkin style—Shishkin would go out to paint his forests. He would take an axe with him, chop down what was in the foreground blocking his view. He painted from life—but what is truly painted from life is not art. Art is an image of the spirit, a system of national-aesthetic thinking or perception.

And this reminds me of the case from Leskov—“Levsha” (The Lefthander). There’s an interesting moment when this Russian craftsman, who could do anything, was given a French metal flea that could jump, for him to shoe it—see, what we Russian craftsmen are capable of! And that Levsha locked himself in his hut, where “the yoke was hanging,” but he did shoe the flea. But it stopped jumping. It's the same in art—when it works, it works, but when it is so perfected that some artist shoes a flea, it ceases to be art. Leskov must have had such a thought, because he was a clever man. Here it is jumping—and here it has a shoe, but it no longer jumps.

It’s the same in art. What is essential is passed down from age to age. Our national Ukrainian art is figurative. But it is silted up—our artists studied in Petersburg, in Moscow, in Italy, or somewhere else, but our national Ukrainian school—where is it? Boichuk was shot, Narbut was poisoned. I learned later how Moscow destroyed the Ukrainian national elite—historians, artists, the very essence of the Ukrainian nation—the peasantry. Because the cities were not Ukrainian, they were Jewish or Muscovite. When people came from the farmsteads to the city, the culture there was not ours, it was urban. Our rural population was drawn to the city, because there you had to sell, to trade. Ukrainians were only allowed to live on the outskirts of large cities, to be construction workers. Some managed to get the right to settle there. But in essence, all Ukrainian cities—they are not Ukrainian. Well, Kolomyia is still Ukrainian to some extent, Kosiv too. But Ukraine, it seems to me, will stand firm when there are Ukrainian cities, when there is a Ukrainian Kyiv—because it is not yet Ukrainian. We are freed to some extent from control, but the occupier and his idea, as Lenin once said...

By the way, I read this in Svitlychny’s possession. One time I was at his place, and he brought home sixteen volumes of “Congresses of the RSDLP, VKP(b), CPSU” and such. I asked him why he had bought so many party materials. And he says: “Panas, there’s a lot of interesting stuff in there.” I looked at one volume, flipped through it and came across this: one of the delegates called Lenin a prostitute. Pokrovsky, I think: “You say one thing, but you do another.” Lenin, in his concluding remarks, retorts to him: “Yes, that is the situation, comrades, but we took Ukraine. It cost us about two thousand victims. We took it from the inside, but if we had taken Ukraine head-on, with a front, it would have cost us a countless number of victims.” I think, how deeply he understood and saw. Which of the deputies in our Verkhovna Rada has read Lenin and can quote this—“We took Ukraine from the inside”? They want to take Ukraine from the inside now too.

V. V. Ovsienko: Those collections were called “The CPSU in Resolutions and Decisions of Congresses, Conferences, and Plenums of the Central Committee.”

O. I. Zalyvakha: This Symonenko and all the others—they should be sent to a madhouse to check who they are, and whether they have actually read Lenin. It seems to me they are ordinary, dull-witted careerists, because Lenin had his wits about him, but they... As the saying goes, who can we surrender to? It’s already the eighth anniversary of independence, and we are under siege. The nomenklatura is still in place. It was controlled by Moscow and is still controlled. I remember reading once that they would still be dividing those eight tons of gold—remember? And now they say: “There isn’t any—no diamonds, no gold, you owe us.” Israel receives huge sums of money from Germany for Hitler’s crimes. But Ukraine, for the forty million Ukrainians who were lost, demands nothing: brothers, pay up—we lost so much! And we are still in debt to them! And Kravchuk said we have a zero option, and now we are even in debt.

V. V. Ovsienko: Yes, in debt—we pay for gas, for oil, and more expensively than other nations.

O. I. Zalyvakha: And they come to embrace us! This head of the Verkhovna Rada, Tkachenko—he’s a brute, he should be in a madhouse, what is his level! And he’s an academician, by the way—that’s how it is. People might think: what kind of academicians do they have in Ukraine...

V. V. Ovsienko: I call him a collective farm boar.

O. I. Zalyvakha: It’s a disgrace, he’s a bull!

V. V. Ovsienko: But let’s return to 1965.

O. I. Zalyvakha: Somehow, Allochka found out that for the 150th anniversary of Shevchenko’s birth (1964), they planned to make a stained-glass window at Kyiv University. There was a huge window there, and, I believe, a statue of Lenin stood there. We developed a sketch. The late monumentalist Ivan Stepanovych Kyrychenko gave me a copy of the “Kobzar” to read. I flipped through the book and expressed the idea that we should take a text from the “Kobzar”. Allochka and I looked and decided that this was it: “Vozvelychu Malykh rabiv otykh nimykh! I na storozhi kolo yikh Postavliu slovo.” We discussed it, thought about it. It seemed there was no better text for a stained-glass window. Liuda Semykina organized the frames for the window. We spent the night at Allochka Horska’s apartment here, on Repina Street. I recently walked past that apartment with Nadiyka Svitlychna, where the Zaretskys lived—it’s unrecognizable, everything has been redone. The balcony is redone, the courtyard is redone. As if the Zaretskys never lived there. They erased the traces of Alla Horska. Thieves know how to cover their tracks.

And so we made that stained-glass window. It has two parts. The central part is Shevchenko, and a woman is leaning towards him. Shevchenko is holding up a book with one hand and supporting the woman with the other. I had also made a mosaic on the theme of Shevchenko before that, laying out the mosaic on a slab, in that same Kyrychenko’s basement. One time I was carrying it out, thinking of submitting it to an exhibition. And the party organizer of the Kyiv Union of Artists walked by and looked: “And what are you carrying?” “A mosaic for the stained-glass window about Shevchenko.” I did take it, I think, to the exhibition pavilion, and there they told me: “Panas, they’re already talking about you in the Union, that Kashpyrovych (I think that was his name) said he ‘saw such a Shevchenko—do you understand what he’s doing? Shevchenko is there with a book.’” They told me: “You’re in trouble, Panas, it’s not worth making any more mosaics, take this either now or later.” Of course, it didn’t get into the exhibition.

And this party organizer of the Kyiv Union of Artists, who carried out the “party line” that, so to speak, got me into trouble, a few years later applied to leave for Israel. They told him at the Union: “Why are you leaving? You have good works, ideological paintings, you’re one of ours, a Soviet artist, you’re so ideological.” And he said: “You’re not offended?” “No.” “Well, I’m not offended at you either—let me go. I served you—do me a favor too.” Well, they signed off on it and he left.

So we finished the stained-glass window. On the evening of March 8, 1964, at midnight or maybe one in the morning, we lit it up with electricity—the window came alive. True, a few days before that, the university’s party organizer came, pulled me aside, and asked: “Why are you doing this?” He switched to Ukrainian: “People have approached me and said that people are stopping here and asking what this is.” “Well, that’s good that people are stopping and looking, because before they didn’t look, and now they do.” “But it’s on the stairs, there will be a crowd.” But we saw that it looked good, and we went to spend the night on Repina Street.

In the morning we got up, got ready, washed up, and went to the unveiling of the stained-glass window. We arrive—it’s covered with a canvas, broken glass is lying around... The whole thing was a bust. The rector of the university, Academician Shvets, had forbidden it. They told me he signed his name “Shvets.” And that “Shvets” (tailor) and “podlets” (scoundrel) are written without a soft sign. They had shown him the sketch earlier, he had looked at it and approved it. The result was what it was.

The guys here are smart, they know what’s what, they called in an authority figure. At that time, such an authoritative writer was Mykhailo Stelmakh. Around eleven o’clock, Mykhailo Stelmakh arrived. After Drach and Dziuba, it was the first time I saw a classic, the writer Stelmakh. He looked at the sketch and said: “I can’t see what you have made, but on this sketch, I see nothing anti-Soviet, anti-aesthetic, or deconstructive.” And that was the end of it—on his good word.

Later we were summoned to the Union. At the meeting, they were “giving a dressing-down” to the Kyivans—Allochka Horska, Liudochka Semykina, Halynka Zubchenko, Veniamin Zaretsky, and others. But I was in Frankivsk. I was already an outsider, like in Camus. They called me, I arrived just as the party members were discussing Allochka Horska, Semykina. Everything was conducted in Russian.

By the way, something interesting. I knew Danylo Narbut—the son of that Heorhiy Narbut who once designed Ukrainian money for the Central Rada. He visited me once in Frankivsk. He spoke Ukrainian with me, but with his dog—only Russian. It struck me as a bit odd, that he used the noble language for the dog, and the ordinary, Ukrainian language for our conversation.

After the stained-glass window (it didn’t end with various reprimands), I was arrested some time later. Because I was “thinking incorrectly, un-Soviet.”

In March 1966, they tried me and sent me by transport to Mordovia. In Lviv, I met Valentyn Moroz, already convicted. We were transported to Mordovia together. Valentyn kept a diary—he had a general notebook with him. One time I noticed—before lights-out, he would write five to ten sentences in his diary and memorize 10-15 German words. He mastered the German language, I think, very well. At the transit prison, in Saratov, or wherever, Valentyn really got in with the shuryks—he would undress like them or do something else. I say: “Valentyn, why are you fawning over those shuryks so much?” He says: “Panas, it’s very interesting to know their psychology, to be in that zek environment.”

We arrived in Saransk, and from Saransk to Potma. The gate opens and they let me into the zone, behind the wire.

V. V. Ovsienko: And which zone did you end up in?

O. I. Zalyvakha: ZhKh-385/11.

V. V. Ovsienko: Is that Sosnovka?

O. I. Zalyvakha: No, I was in Sosnovka, but later. Yavas. Yes, like two words—“ya” (I) and “vas” (you). I entered the zone. The zeks are already there: who, from where, to where? They approached me: “We’ve heard about you. It’s so good that we have a reinforcement. We thought there was no wind, no wave left in Ukraine—and they’re still jailing people! That’s great!” I felt that it was... “We,” they say, “haven’t seen fresh prisoners in a long time.” “I’ve served,” says one, “fifteen.” Another says: “I’ve already served twenty.” “And you—you’re a fresh reinforcement. We see that Ukraine still exists.” It was interesting to hear such words from dreamers: “We thought you all had been buried, snowed under.” As that Vinhranovsky said: “Not snowed under? You won’t be.”

The guys took me, led me along, one of the guards determined where my bunk would be, which one I wanted, where there were more Ukrainians. They settled me there, found a level bunk, the old-timers brewed some coffee—you know how it is there... The cup went around the circle—two sips each. Mykhailo Ozerny from Frankivsk was there. He was a teacher, he also got three years for anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. They ask what case you’re in for, what the situation is in Ukraine. We are at what diplomats call a round table—but we were sitting on the grass.

That’s how we got acquainted. Later, I reflected on the theme of a person’s formation. I read somewhere that in prison, a person becomes most free, because they are uninhibited. I thought about that “big zone”—Ukraine, the entire USSR, that “zone” called the “socialist camp.” In the “small zone,” a person feels much freer. They can say what they want, because they’ve already been caught. Before lights-out, such intellectual people walk around, getting to know each other—one from Yerevan, one from Georgia, one from Moscow. Ivan Rusyn, when he was being released from the camp—he got a year, spent some months under investigation, and the rest in the camp—he said: “Panas, I would stay in the camp for another six months or more, because I’ve met so many people with whom you can speak openly. That won’t happen in the ‘big zone.’” The old prisoners were surprised: how could he want to stay another six months! Because a bouquet of thinking humanity had gathered there...

Mykhailo Soroka invited me to his barrack. I had already found out—one of the guys told me that there was a prisoner here who had been incarcerated for forty years. This was Mykhailo Soroka (Note: 27.03.1911, died 16.06.1971 in camp ZhKh-395/17. He spent a total of 34 years in captivity). He had been imprisoned back in the Polish era for the Pieracki case, since 1937. Later, in thirty-nine, he was released, in forty, he was imprisoned and taken to Kyiv. He was an old-timer there, an authority among the zeks.

So, in the second week or a week later, Mykhailo Soroka invites me to his barrack. I look—a small table, he’s made canapés, like they make in Lviv, and something else. We sat, got acquainted. He told me about himself. I felt that this was a person who had a special authority not only among Ukrainians, but among the zeks in general.

Soroka told an interesting story. He was in a transit prison somewhere. They bring in a zek who has just come from the hospital. The others jump down from their bunks: “Well, old man, what have you got there?” They pull out a piece of a bread roll, a pat of butter—and take it. I, he says, got down from my bunk, take this butter, that piece of bread roll and return it to him. And this man had just come from the hospital, he had an operation and they gave him this butter and white bread. Soroka says to this pakhan: “Who are you taking from?” “And who are you?” And we, he says, stood like that... either-or. And that zek couldn’t take it—he went back to his bunk. The spirit triumphed!

Soroka was recently translating Thomas Aquinas, he showed me the notebook. There were two general notebooks, such stitched books, about a centimeter thick. He says they were confiscated. I made an ex-libris for him there, in the camp.

V. V. Ovsienko: And what did you make it with?

O. I. Zalyvakha: Well, the guys from the mechanical workshop made me a cutting tool, and Soroka found linoleum in the camp. He stamped it on paper for himself and wrote letters to his wife Katria, who was also imprisoned.

He was a strange man. The guys sent me books. They sent some art book in Czech or Slovak.

V. V. Ovsienko: You could still receive books by mail then?

O. I. Zalyvakha: It was still possible then. They subscribed me to the newspaper “Druzhno Vpered,” Czech or Slovak... From Slovakia, indeed.

V. V. Ovsienko: Even a foreign one?

O. I. Zalyvakha: Yes. But then they were cut off, and they stopped reaching me. Ivan Svitlychny and the guys wrote a petition to allow the artist Zalyvakha to draw. I was called to the special section and they said: “You can draw—we have a club, go there, we are writing ‘To freedom with a clear conscience.’” I look at what those artists are writing. “No,” I say. “I don’t know how to do that, I would just like to draw.” “But no,” they say, “we have a club, please, you can work there as an artist.” So Svitlychny’s petition had an effect on them. They called me in, but they started to watch me more closely, to observe, because my ex-libris and something else had appeared in “Druzhno Vpered.” That was, I think, Mushynka (Note: Mykola Mushynka, a Ukrainian cultural figure from the Prešov region) who published it there. They conducted a shakedown on me, and since I wasn't hiding it, they took the newspaper.

But one time, something interesting happened. Dmytro Ivashchenko, Moroz’s accomplice, was being released into the “big zone.” The guys were writing some petition, and I made a woman’s hairpin and stamped that petition into it, sealed it, and made a little ornament. He was released with that hairpin, it was like a souvenir. Ivashchenko had it for a long time, and then they came to his place supposedly for something else and prised this hairpin open, found the piece of paper inside. “And where did you get this?” “I don’t know, it’s mine.” Later they established that Zalyvakha had made this hairpin. They took me from the zone to Saransk. They sat me down like this, one man at a table with papers, and two people standing on either side of him, and me in front of them. They talked about the weather, and then they mentioned Ivashchenko: “Do you know him? He was imprisoned with you, it seems?” “I think so.” “That tall one, who was with Moroz, his accomplice.” “Maybe so, I don’t remember.” “And how did you pass this to him? Did you make it?” I see—these three are looking at me. And I had read somewhere before that when a person is lying, their upper eyelids twitch. I already knew what was what, and I kept calm. I’m generally a bit of a phlegmatic type. And they played out that scene to “catch on,” to see how my eyes would react. It was an interesting psychological study.

People from Kyiv, as they used to say, “cultural figures,” came to visit us in the eleventh zone.

V. V. Ovsienko: “Representatives of the public.”

O. I. Zalyvakha: Oh, yes!

V. V. Ovsienko: Led by a KGB agent.

O. I. Zalyvakha: Yes, yes. They call for me. Some journalist approached: “Oh, is that Zalyvakha?” He offers me his hand, but I felt somehow awkward shaking his hand, so I said something like: “Good day.” “And why don’t you come join us? We came to have a chat with you.” “About what?” “You understand that Ukraine is being built, we all must work. What are you doing here? You have your own work, and here you are sawing boards.”

And there was an interesting reinforcement at this time. I remember, it was sunny. The gate opens and they bring in new zeks. I look—it’s Yaroslav Lesiv from Ukraine. He was twenty-one, or twenty. We met him, all was well. After those prison wagons, after those transit prisons, he walked around a bit, jumped around—and suddenly does a somersault. All the zeks were surprised: what was that? And he was an athlete, thin, so fit, he didn’t drink or smoke. And he did a somersault. I somehow got to know him, became friends with him, later we became kumy. And this Slavko would come to see me from time to time. He wrote poems, read them, we talked. He told me about himself, about Zeniy Krasivskyi. I was happy to see such a young man, because I was already older. Among those who were imprisoned at that time, I considered myself a bit of a latecomer. I thought: what is this? Everyone here is young, and I’m the oldest among the young. It was a little awkward. But, as they say, better late than never.

V. V. Ovsienko: And Bohdan Horyn was there too? Because he wrote a brochure about you.

O. I. Zalyvakha: Bohdan Horyn? Yes. We were there together. Mykhailo later, but in another zone. Mykhailo wasn’t there for long. And Moroz wasn’t there for long either—they were transferred. One day they call me: “Zalyvakha! Zalyvakha! There’s a person by the fence!” I look—Ivan Oleksiyovych is walking there. We exchanged a few words, he went to the other side. From the other side of the barrack, we exchanged some visual information. Later, Allochka Horska arrived. She was in that fur coat. She walked around that camp like a queen. I saw Raia Moroz near the walls—she came to visit her husband Valentyn Moroz. My friend Veniamin Kushnir, with whom I used to stay and paint in his studio, came to visit. They detained him there for three days.

One time—I had already served three or four years—they take me for transport—“with belongings.” I left all the books I had. I took a small bag, a piece of bread, something else—and off to transport. I left with nothing. They led me out of the zone, there was a “bobik,” they put me in and drove me away.

V. V. Ovsienko: A “bobik” or a Black Maria?

O. I. Zalyvakha: Or a Black Maria—something like that, some kind of car. First, they took me to Moscow. There is a huge multi-story prison there, Lefortovo. I spent the night there in one cell, and the next day—into a Black Maria and they drove me away. We’re driving and driving, a forest all around—where are they taking me? Suddenly the forest ends—Vnukovo, the airport. I waited a bit while they prepared the plane, then they led me on, to the pilot. There are four seats there near the cockpit. Then, I see, they started seating passengers. We sat down, there are magazines, two military men are sitting next to me.

[ E n d o f c a s s e t t e]

We took off. The stewardess brings a tray with candies. I liked that she came to me first, she sees that my escorts are to my left and right...

V. V. Ovsienko: And you were in the black zek uniform?

O. I. Zalyvakha: In zek clothes, because they took me from the camp—and onto the plane. It’s interesting that she looked at me so sympathetically, offered the tray of candies, and the thought flashed through my subconscious: should I take several or one? But something held me back, I took one candy. She went on to the passengers, from whom we were separated by a curtain, a little curtain like that. My head is spinning: where are they taking me on a plane? They brought me to Boryspil. The passengers got off, a car drove up, they put me in a “Black Maria” and drove me to the KGB building on Volodymyrska Street. They brought me in, did a thorough shakedown. I had a piece of herring, a piece of bread, and a bag. I was wearing these work boots, the kind for construction.

The next day, after I had spent the night in a separate cell, they took me out for a walk. The guard who let me in looks at my boots—and it was summer, warm, hot, and I had no socks. So I had cut out holes with a razor blade, made some sandals. “You had boots yesterday, and what is this now?” I say: “No, they were like this.” “But I saw them yesterday. Yours didn't have holes.” And I had inserted a razor blade into the herring. He broke the bread like this when he was checking it, but I had stuck the blade into the herring, where the gills are. So I was armed. He looked at me with such confusion, that I had outsmarted him.

I stayed there for about a month. One time this guard comes and says: “You know, you’re a bit... You have this here...”—he looked at my boots, at everything. “They’re calling you,” he says, “upstairs. You hold yourself together there, you understand?”

V. V. Ovsienko: They hadn’t called you for a whole month?

O. I. Zalyvakha: Not a month, less. But they fattened me up a bit there.

V. V. Ovsienko: Ah, they got you into “marketable condition.”

O. I. Zalyvakха: Into “marketable” condition, to show me to the high-ranking officials. So the guard tells me: “Pull yourself together a bit, you know—this is your last chance, because a high-ranking person wants to talk to you.” He took me upstairs, went in, reported that he had brought me. They let me into the room: “Sit down, please, sit down.” I sat down. “Well now,” he says, “what is it, Zalyvakha, you are wasting a lot of time for nothing. You could be painting, be at home, they wouldn’t be chasing you around anywhere. Think about it. You only have one life, one purpose.” I say: “You’re telling the truth, it’s true: one life.” “I would like,” he says, “for you to finally realize.” He didn’t say what our mothers brought us into the world for, but he said that life is one and you have to do something useful for people in your lifetime. I asked: “And what do you propose for me?” “That,” he says, “depends on you.” “Can you let me go home, I’ll do my own thing there?” “No,” he says, “you could write that you were tempted, that you stepped onto the wrong path. Our people are working by the sweat of their brow, building a bright future, and you have buried yourself, thrown yourself out of the movement. Here, write, write.” I say: “You know, I’m a very weak writer.” “We’ll help you, we’ll compose it, and you just write that you were led astray into a line of movement that wasn’t your own, not your own direction,” he advised me. I thanked him, I say: “No, I can’t do that.” “Well, you watch out, because you either go, we’ll take you home, or back to Mordovia. Choose what is more precious to you.” I say: “Take me to the camp.” “Well, alright. Consider this your last chance.” I say: “Thank you for the offer.” We spoke so gently with each other.

V. V. Ovsienko: And who was he, did he say?

O. I. Zalyvakha: No, he didn’t say. Some... I don’t understand ranks. He came out from behind the table: “Well then,” he says, “as you wish.” He comes up to me and offers me his hand. As a zek, I—put my hands behind my back, thank him. And it was so interesting for me to watch his hand fall. He offered his hand for a farewell, and I kept mine back, didn’t offer it. I was a little ashamed, I thought: this is a person, after all, but something held me back, I didn’t want to take his hand. I said “goodbye” and left.

I stayed in Kyiv for some time, and then they brought me to Frankivsk. And I stayed here for some time. Well, here they just kept me, it seems, no one talked to me, just a pause. And then to transport and back to Mordovia.

V. V. Ovsienko: These wanderings took about a month or two?

O. I. Zalyvakha: About that. They returned me via Saratov. I remember that in Saratov they fed us very well. There was sterlet, and other Volga fish. One time they gave us a delicious ukha, and it was the first time I ate that Russian fish soup. By the way, regarding zek food. There, in the 385th administration, an Armenian was imprisoned with us. He had crossed from Armenia to Turkey and wanted to go to the West. But he was caught in Turkey and handed over to the USSR. On the transport from Yerevan to Potma, he said: “In a Turkish prison—it’s Bayram. They give you raisins, kishmish, other things. They give you shashlik on some Muslim holidays. The food is varied and good in Turkey. But here from Yerevan to Potma—shchi, kasha—the same food.” Russian prison and Turkish prison... Although Turks and Armenians are not very friendly, but...

They brought me back to Mordovia, to the eleventh camp. I served out my term there. Then I was in the fourteenth, and somewhere else. By the way, when I was brought from Kyiv, I immediately went to my friend from Frankivsk, Mykhailo Ozerny. We were close. He subscribed to “Literaturna Ukraina” and as a linguist, he would sometimes explain things to me. He says: “Here, Panas, think about it—the word: nebo (sky). Ne-bo. ‘Bo’ (for) is like a warning of something, and ‘ne-bo’ (not-for) — don't be afraid, something like that. But it has come together in one word ‘nebo.’”

So, when I returned from Ukraine, the guys tell me: Ozerny has already become... No, not a Jehovah’s Witness, but a Pokutnyk. They would gather, five or ten men, shoulder to shoulder, and sing some little songs—psalms, something else. I ask how this happened? They say there is a barrel there, and in that barrel is water, either rainwater or some other kind, but it’s full, and they put Mykhailo in there, undressed him, and baptized him as a Pokutnyk. I think it was into the Pokutnyks—such a sect. And I never saw Mykhailo Ozerny again, because he was already in that group. I thought: what happened to Mykhailo? By the way, he had a very interesting head. When I was in a transit prison somewhere in Sosnovka or Saransk, a zek, a Russian, comes up to me and says: “Is he really a Ukrainian? Look at his head—that’s a Nordic type!” And he had such a fine forehead, such a sculptural head—he didn’t look like a Ukrainian at all. Well, that was his external, racial appearance. So he moved away from us. I met Mykhailo some time later: “Good day, Panas.” He was no longer one of us. Have you heard of the Pokutnyks?

V. V. Ovsienko: I know about the Pokutnyks. Semen Skalych was imprisoned with us in the Urals, in Kuchino. Pokutnytstvo is a purely Ukrainian religious movement. The main idea is that in Ukraine, in Halychyna, where Serednia Hora is—that’s where the New Rome will be.

O. I. Zalyvakha: Then Ozerny is not a Pokutnyk: I know Skalych. This was some sect, I don’t know—Subbotniks maybe... He was baptized in that barrel of water. And Mykhailo disappeared from our Ukrainian view... I heard something about him on the radio later.

But Mykhailo Soroka impressed me the most. Once he told a story similar to mine. He says they took him to Kyiv, brought his son Bohdan from Lviv. They gave him, he says, a black suit. They were in a restaurant with his son.

V. V. Ovsienko: In the restaurant above the “Khreshchatyk” metro station in Kyiv?

O. I. Zalyvakha: That’s the one. Mykhailo with his son and two of those guards. Then they took them to the theater. They say to Mykhailo: “Well, will you go home with your son, or again...” Just as they told me: “You will paint there or here.” So Soroka says: “Of course, I will go to the camp.” And so, he says, we said goodbye to my son. They brought me back, took off the black suit, gave each his own—my zek clothes to me, and their uniforms to the guards. It was interesting to listen to Mykhailo!

V. V. Ovsienko: And they also said that when some dishes and drinks were served in that restaurant, he didn’t take anything—he supposedly only drank water.

O. I. Zalyvakha: Because it was from the hands of the enemy. He was an authority for all nationalities. When something inter-ethnic happened, they would call him, and his word was final. By the way, it wasn’t a Ukrainian zone, but the vast majority there were Ukrainians.

V. V. Ovsienko: How many people were in that 11th zone?

O. I. Zalyvakha: There were over two thousand, and about half were Ukrainians. When I was there for Christmas for the first time, the guys gathered whatever they had: a piece of salo, someone had some poppy seeds, and they made such a feast. And there in the camp, I met a “worker from the Pushkin House”—he’s somewhere in Sweden now, I heard on the radio. We prayed, and this Russian says: “We don’t have this.” There you have it, brother Slavs! “We don’t have this.” It was strange for me to learn that: from the Pushkin House, an erudite man, and suddenly he says: “We are different people, we have a completely different culture.”

V. V. Ovsienko: That must be Yevgeny Vagin, one of the leaders of the monarchist organization VSKhSON—“All-Russian Social-Christian Union for the Liberation of the People,” arrested in 1967.

O. I. Zalyvakha: Vagin, that’s right. He’s in Sweden now. They would sometimes approach us. Say, some work was published in Ukrainian translation—either from Czech or German, they would ask about certain words. They read Ukrainian journals, and it was pleasant for me that a Russian would turn to me: “How should one understand this—it’s like this here, but somewhere else it’s like that?” They followed the latest news. At Christmas, that Russian intelligentsia was also invited. The writer who is now in Paris, Sinyavsky, was there then. Daniel and Sinyavsky. I was acquainted with them. One time our Ukrainian camp community invited Andrei Sinyavsky for a meeting. He conducted it on a high level: “Gentlemen!” He told us about himself, about the Russian national idea, about that movement, about art. I once spoke a little with Yuliy Daniel. He wrote that thing of his, I forget what it was called, something interesting... I had also thought about that topic once, and I expressed my opinion: “I haven’t read your piece, but the title is something...” There were some transgressions... “Day of Murders,” I think. “Day of Open Murder.” That there is one day in the year when you can settle scores with whomever you want. “Day of Open Murders.” He wrote such a work. It’s like a day of revenge. You have an enemy—on this day you can kill him. So I say: “It’s an interesting thought: to know your enemy, but should you kill him, or, like Dostoevsky, simply stop noticing him.” I say: “An interesting thought. What do you think about it?” I hadn’t read his piece, but the title itself gave me the opportunity to reflect on this topic.

And that Russian community kept to themselves. They were hostile towards Ukrainians. We had a guy—maybe you caught him too—Yoffe.

V. V. Ovsienko: I know Veniamin Viktorovich Iofe well. He spells his name “Iofe.” We met at the Museum of Victims of the Totalitarian Regime in Kuchino in the Urals, we traveled to the Solovki Islands together twice.

O. I. Zalyvakha: No, this was the camp chief, Yoffe. And so two Yoffes were talking through the barbed wire. That one says: “What kind of Yoffe are you? I am Iofe, and you are Petrov or... You see, we are both Iofe. One is in the camp, and the other is guarding him.” Such was the dialogue between two Jews. And our Yaroslav Hevrych was pulling that Iofe’s tooth. He was a dentist. Well, he joked about it: “You need an injection here so it doesn’t hurt.” “You be careful.” Because a zek is treating you...

V. V. Ovsienko: What kind of injection? An imaginary one, perhaps.

O. I. Zalyvakha: Yes.

Well, we are reaching the end of the imprisonment. I got ready, they shakedown me. I had drawn a little there, Ivashchenko made me a small album with pencils. From general notebooks. He was so good at making little books.

V. V. Ovsienko: And what did you draw with? Did you have any paints?

O. I. Zalyvakha: No, pencils and markers. Colored pencils were allowed. I stitched several notebooks together into one, and this little album. They took me for a shakedown, to be released from the camp. I put what I could into a bag. They led me to a guard. He was either Erzya or Mordva, some local guy. There were Erzya, Moksha, and Mordva there. Three tribes. “And what is this you have? And this?”—he began to examine everything carefully. I say: “Do you have a museum of Erzya here in Saransk?” “Yes, we do.” Because I had heard that Erzya was a great Mordvin artist. He and Konenkov returned from the States. Konenkov was given a workshop and an apartment in Moscow, but Erzya was given nothing, so he went to his homeland, to Mordovia. I say: “I’d like to know where to look for it... I’d like to see it—he’s your famous sculptor.” The guard sees that I have drawings, and he was so moved that I was interested in Erzya that he says: “Well, alright,”—and put it all together. He didn’t even search me much, because I started talking about Erzya, how to find his museum. Well, and I walked out of the zone...

V. V. Ovsienko: They released you from the zone? They didn’t transport you all the way home back then?

O. I. Zalyvakha: No.

V. V. Ovsienko: By my time, they no longer released people directly from the zone, but took them to the regional center and released them there. This was so they wouldn’t give interviews in Moscow.

O. I. Zalyvakha: No, I walked to the station. I arrived in Moscow. And before that, Svitlychny had written to me: “Panas, when you get out—here is Les Taniuk’s address in Moscow.” I arrived in Moscow, found the Taniuks.

V. V. Ovsienko: You knew him before?

O. I. Zalyvakha: I knew him through Alla Horska, back when the Creative Youth Club existed. Taniuk received me very well, briefed me. I went to the Shevchenko monument—that Shevchenko by the Moskva River. I sat for a bit, went to the station, and arrived in Kyiv. They met me here—Taniuk had already sent a telegram or said by phone that Panas was coming. Here was Ukraine.

V. V. Ovsienko: Alla probably organized the meeting?

O. I. Zalyvakha: My own people, and Alla. I went to the Svitlychnys first. Liolia says to me: “Panas, come on, we’re taking you with us.” They took me and went to get me dressed up. Such an outfit... They said that near Kyiv there is an interior that Alla designed—“Natalka,” I think it was called. We went there—there were people. Zenya Franko came in later. An orchestra was playing something. Someone says: “Panas, go on and dance! You’re in the Big Zone now.” And I had to dance a little—not the hopak, like Khrushchev danced, but just something, like roosters. Like a warm-up. It was colossal!

V. V. Ovsienko: And who was there—do you remember?