Interview with V. V. Andrushko

(With corrections by V. Andrushko dated March 13, 2005)

Vasyl Ovsienko: On July 18, 2000, in the offices of the Republican Christian Party at 23 Petro Sahaidachnyi Street, we are speaking with Mr. Volodymyr Andrushko. Vasyl Ovsienko is recording.

Volodymyr Andrushko: I, Volodymyr Andrushko, son of Vasyl and Daria Andrushko, was born in the village of Sadzhavka, Nadvirna Raion, on the border of the Hutsul region. I was born on December 5, 1929, but according to my current documents, I have a different date—February 9, 1930, because that’s how the birth certificate was issued. But I was actually born on December 5, 1929. My village is on the Prut River. My parents were peasants. In that area, they were known as Ukrainian patriots. My father was born in 1896 in the village of Sadzhavka, and my mother in 1894 in the Ternopil region, in the village of Ozeriany, which was then in Berezhany County. My mother died in 1967 in Kalush Raion, where I also lived after returning from the concentration camp. She is buried in Sadzhavka, where she lived for most of her married life with my father. Her maiden name was Daria Hutsuliak. And my father was Vasyl, son of Oleksiy. During the war, my father emigrated to the West and died in 1971 in the United States of America.

I was an only child, and in the first post-war years, because we were persecuted by the Bolshevik occupiers who replaced the German occupiers, we were forced to leave our home and flee from the persecution of the NKVD. For some time, we lived illegally in Kolomyia and other places. Later, I managed to legalize my status and graduated from high school in Kolomyia. I received my primary education in my home village, Sadzhavka, and during the war, I studied at the Kolomyia gymnasium—there was such a gymnasium in Kolomyia during the German occupation, though not for long, less than a year. It was there that I first became directly involved in the national liberation movement, belonging to the youth network of the OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists).

With the arrival of the Bolsheviks, the gymnasium ceased to exist, so in 1944, I was in the seventh grade of secondary school No. 2 in Kolomyia, and the eighth grade in school No. 1. For the ninth grade, I had to go to the village of Kornych near Kolomyia, where my godfather was the principal. But there was no one left to go to the tenth grade from that school, as some of the students had been arrested, and others had gone into the underground. I was fortunate to graduate in 1948 from the evening school for working youth in Kolomyia.

From that time on, I had no opportunity to study anywhere; I had to work. At that time, there was a shortage of teachers, so I got a job as a teacher for first through fourth grades in the village of Velykyi Kliuchiv in what was then Pechenizhyn Raion. I worked there for about three or four months and was fired because they gave me an ultimatum: either I join the Komsomol and continue to work, or they would fire me. I did not want to join the Komsomol, although I had connections with the underground, which allowed me to join, but it was hard for me to accept, and I decided it was better to leave the job. I was fired.

The following year, I went to another district, Kolomyia Raion, and again got a job as a primary school teacher in the village of Debeslavtsi. There I was closely connected with the underground. I had to join the Komsomol because of my illegal activities, as I was again facing dismissal from my job. It was a turbulent period of my life. I nearly died there once.

V.O.: And what did that activity consist of?

V.A.: I hung yellow-and-blue flags, distributed leaflets, burned down the Bolshevik club and its library, and destroyed the collective farm's thresher. I also wanted to burn down the collective farm, but I didn't succeed.

V.O.: You said you almost died...

V.A.: It was a situation like this. One day, I arranged a meeting with the insurgents. We met in a field in the evening to discuss various matters. I arrived. It was a very beautiful autumn. A warm, starlit evening. There were two of them, and I was the third. They were armed, of course; I was unarmed. They said there was no NKVD operational group in the village; intelligence had reported that it was safe. So we felt secure. But an operational group was just passing through our village from another, and they stumbled upon us purely by chance. But we saw them a moment sooner. One insurgent had a ten-shot carbine, and the other had a regular rifle, a *kris*, while the NKVD operational group had several submachine guns and a light machine gun. They spotted us and opened fire. I had to run for about a hundred meters, and uphill at that. I remember it felt like every step I took was my last. I ran, fell, got up, and fell again under the flashes of flares... I was lucky; I managed to escape. My friend, however, fared worse; he was seriously wounded, but by some miracle, he also managed to retreat. This was in late September 1949.

I had many such illegal adventures. I often transported literature and weapons. Twice I was caught with literature, but they didn't look inside my briefcase. Once, they were taking me to the NKVD—someone at the market had pointed me out as suspicious. They led me right to the door and left, and I just kept walking—it felt like I was born again!

Finally, in 1951, I had some documents and was living, one might say, legally, and I had to join the Soviet army. But for me, joining the Soviet army was worse than going to prison; I hated it so much. I knew it wasn't an army but the Golden Horde. I couldn't bear that oppression, that abuse; I might as well have gone into the underground. But by 1951, the underground in our Kolomyia Raion was already coming to an end.

By chance, I found out that students at Chernivtsi University were not being drafted into the army. I enrolled in Ukrainian philology. I still had ties to the underground, bringing them literature and leaflets, and on the night of May 23, 1952, I hung the national flag over Chernivtsi University.

V.O.: May 23—is that a significant date?

V.A.: It’s the Day of Heroes. It was an event that became known not only at the university but throughout Chernivtsi, in Bukovina, and in Kyiv. They searched hard for who did it, and I had hung a flag not just at the university but also in the city. They didn't find me, but they suspected I was unreliable because they established that my father was abroad. When I enrolled, I had, of course, concealed that. Then they expelled me without any specific accusations, as an unreliable student, undesirable to them. I was already in my second year, even near the end of my second year. They got to me almost a year later. Of course, I didn’t confess. “Then tell us who did it.” I said that if I found out, I would tell them (laughs). “Since your father is abroad, such a scoundrel, a traitor to the Motherland, and you don’t want to help us, then take your documents and get out of here!” I understood that if I didn’t leave, things would get worse. I took my documents—they gave me a transcript showing that I had completed the second year of university.

And when Stalin died in 1953, a certain thaw began. They were busy with their own affairs, the NKVD had weakened a bit, and I managed to sort of transfer to the Ivano-Frankivsk Pedagogical Institute, into the third year. I even passed some additional exams there. Strangely enough, they didn't inquire at Chernivtsi University about my character reference. Two years later (at that time, the institute program was four years, not five like at the university), I graduated and was assigned to a job in Kalush Raion, at the Pidmykhailia secondary school.

That was in 1955. But after some time, I was arrested for my activities at the institute. We had a group of students who read literature. They didn't know anything specific about me. It was just that one of our friends, who was suspected of trying to obtain a printing press font, was interrogated and probably beaten a little: “Who else do you know?” Well, he said there was this guy Andrushko, and there was Protsiuk—they were Ukrainian nationalists. They conducted a surprise search of my place—though I always expected a search—but they only found a few small books published during the Polish era and a few pages of my notes, clearly of a nationalist, anti-Soviet nature. By then, this wasn't enough to imprison me; no one could prove anything. I said that as an ideological worker, I had the right to read such books because I needed to be familiar with different ideologies, and as for my notes (there was something about a trial), I said they were just my personal thoughts, that I hadn't shown them to anyone, and no one had seen them. They tried me anyway and gave me five years. I was presented as the ringleader of a gang; my friend, the teacher Vasyl Protsiuk, was also tried and got four years. Another teacher was fired, and one student was expelled from the institute.

They arrested us on October 29, 1959. We were tried by the Stanislav—it was still called Stanislav then—Regional Court. The trial was in March 1960, I don't remember the exact date. My charge was “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” They also found a Bickford fuse and electric detonators, so they added the charge of “possession of weapons and explosives.”

V.O.: That would be under the new Code, Articles 62, Part 1, and 222—possession of weapons, right?

V.A.: Yes, yes. That one also carried a sentence of up to five years; I got one year for it. They had very little evidence against me. But they had information that I was nationalistically, hostilely disposed, and that was enough.

At the time, I was living and working as a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature in the village of Pidmykhailia, Kalush Raion, living with my mother. I had just gotten married and had been married for maybe ten days. My wife was from this village; she was studying at the Kolomyia Pedagogical College. Her name was Mahda Krushelnytska. I later divorced her. I have a daughter—Lesia Andrushko, who now works at a school in Dolyna Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast.

I served my sentence in Mordovia. I was in several camps. I was in the third one, in Barashevo. I was in the seventh—Sosnovka. I was also in the 11th (Yavas) and the 16th. In four camps altogether. I remember the third and seventh the most. I was with Levko Lukianenko, with my fellow defendant Vasyl Protsiuk, with Khrystynych from the Lviv region, with the Dolishnii brothers from the Ivano-Frankivsk region (they were from the UPA)—Ivan and Yurko, and with many others.

V.O.: What were the conditions like in the camps back then?

V.A.: At first, when I arrived, they were relatively easy. It was during the “thaw” after Stalin, so I was even surprised that the regime wasn't as harsh and difficult as I had expected. Initially, I was on the general regime. But gradually, over five years, the regime worsened. I was transferred to the intensified regime, and later to the strict regime.

V.O.: Were there any protest actions in the camps at that time?

V.A.: There were, but they were small. It was no longer possible to carry out the kind of protest actions that occurred after Stalin's death. But we refused to work; there were acts of disobedience, for which, of course, we were punished with the punishment cell.

I was released in 1964. I came home and found my mother ill and my wife ill. I returned to the village of Kniazholuka, Dolyna Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, where my wife worked as a teacher. This is the Boiko region, a beautiful village near the Carpathians. They wouldn't give me a job in a school, so I worked in construction at the Dolyna oil refinery, then at the gas and gasoline plant, then at the Kalush potash plant, and then they sent me to the sulfur plant in the Lviv region. Finally, I managed to get a teaching job in the Mykolaiv region. That was in the autumn of 1967. The school year had already started, and one school didn't have a Ukrainian language teacher. Even though it was a Ukrainian school, the Ukrainian language was not being taught. Then, a person from the Ministry of Education, so to speak, took me on under his own responsibility. I describe this in detail in my book. I couldn't work there for long; I was persecuted, so I fled to the Zhytomyr region. The same thing happened there. I moved to the Khmelnytskyi region—again, the same. Every year I changed jobs: from Khmelnytskyi, I moved to Lviv—and they fired me there too. Finally, I found a job in the Ternopil region, where I was arrested again in 1981.

To be precise, I wasn't arrested in the Ternopil region, but in Kyiv, where I had come with leaflets and was preparing materials to send abroad. I had previously been in contact with Lukianenko and the Helsinki Group but hadn't joined it because I knew the Helsinki Group would be quickly liquidated. It seemed to me that I could hold out longer on my own. But I only held out two years longer. In Kyiv, they caught me on a street while I was distributing my leaflets. But I had a more complex plan, which they never uncovered.

My leaflet was simple—the constitution of Ukraine (they had just adopted a new constitution then) gives Ukraine the right to secede from the USSR. I composed a leaflet stating that we demand Ukraine's secession from the USSR with the goal of creating an independent Ukrainian state. Seemingly, there was nothing anti-Soviet about it. A right is a right. But, just like the first time, what mattered wasn't what I did, but who I was. They caught me, by the way, purely by chance. I had also hung up a slogan: “Long live independent Ukraine!” on a road sign on the way out of Kyiv towards Zhytomyr. This was on August 10, 1981.

V.O.: And what were your connections with the Helsinki Group?

V.A.: I had direct contact with Levko Lukianenko; I transported microfilm and materials from Levko Lukianenko to Oksana Yakivna Meshko.

V.O.: Did you write for the Group's information bulletin?

V.A.: No, I didn't write. They caught me in the Leningradskyi district of Kyiv. It was a Sunday. They brought me to the district police station. They contacted the KGB pretty quickly. Two KGB types came in: “Who are you? Where are you from?” First, they took my documents, established where I was from and all that. “Tell us, who sent you here, what can you tell us about people like you?” I said I wouldn't tell them anything. But it was clear they had already arranged to frame me as a common criminal, not a political prisoner. By that time, they really didn't want political trials; they tried to frame political prisoners as criminals. I said I wouldn't tell them anything. “Oh, we know you won't say anything! Well, if you don't know, then let the police deal with you.” “Let them.” They left.

Prosecutor Usatenko, holding my leaflets, charged me with attempting to rob a store. I asked: “And where is this store I supposedly tried to rob?” “We’ll show you later.” “It’s Sunday, the stores are closed, how could I have robbed one?” “Well,” he says, “you were going to pry the door open with a crowbar.” “But there is no crowbar.” “Doesn’t matter, we’ll find one!” “Why are you fabricating these false charges against me?” He thought and thought, and then said: “If I had my way, I’d have you shot.” “For what?” He thought again and said: “Because your Banderite guys killed two of my uncles in the Lviv region, sometime in the post-war years.” I was in no mood for jokes, but I said: “If your uncles were like you, then they did the right thing.” “Just confess that you wanted to rob the store.” “Why should I confess?” I asked. “It’s necessary for the Motherland.”

I started thinking: if I really confess, the trial will be open, people will come, and at the trial, I’ll say: “Listen, what kind of thief am I? Where is the truth in this?” People abroad will find out that I’m in prison... I hadn’t confessed yet, but I was already thinking: maybe this option would ultimately backfire on them?

They were also trying to pin another charge on me: that during my arrest, I had engaged in “especially cynical” hooliganism. They took me to the Lukianivka prison, and they kept coming and saying: confess, confess. I thought: “What can I do to them?” But my case reached higher authorities, became known in the West, and the prosecutor of Ukraine realized that such a trial would turn into a scandal and an embarrassment, so my case was reclassified as “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” As if the prosecutor had made a mistake, hadn't known I was distributing literature, and thought I wanted to rob a store.

Then they took me to Ternopil and handed me over to the KGB. There they opened a second case for anti-Soviet agitation.

V.O.: How long did that charade with the criminal charges last?

V.A.: About two months. And when, by order of the republic's prosecutor, the case was reclassified, I argued that I was demanding Ukraine's secession from the Soviet Union based on the Constitution. I wasn't calling to beat up communists or overthrow the Soviet government; I was writing that Ukraine has a right, and we can exercise that right. But it was all the same: “Bourgeois nationalist, you wanted to undermine the friendship of peoples.” They found a few false witnesses who said all sorts of illogical and nonsensical things about me. They sentenced me again to five years of imprisonment and five years of exile. The Ternopil Regional Court tried me in March 1982. The investigation lasted a long time, about six months. A whole investigative team worked on it, led by the head of the investigative department, Colonel Bedovka.

There was no evidence. Only those few leaflets they found on me. I told them nothing. I didn't even tell them where the typewriter I used was. Interestingly, by the way: on my way to Kyiv, I had a feeling I would be caught. So I buried the typewriter and some other literature in a forest in Terebovlia. I marked the spot. I hoped I would return and use it. But I was caught. “Who typed the leaflets?” “Of course, I typed them.” “Where is the typewriter?” I didn't tell them where the typewriter was. A camera was part of the case file. They found photos of that area on me, but they didn't guess why I had photographed it: I was preparing material to send abroad. I didn't give them the camera. I gave the camera to a friend. When I returned, he gave it back to me. As for the typewriter—I had marked the spot in the forest where I buried it, but years passed before I returned, and the forest had changed so much that I couldn't find the typewriter. It's still there somewhere. The guys say we should look for it with a metal detector. I wrote to the Ternopil security service, saying that I didn't tell you (and some of my former investigators are still there) where I hid the typewriter back then, but I'll tell you now, just help me find it. They replied very politely that they don't deal with such matters and don't have the capacity. So the typewriter remains there.

V.O.: So they gave you 5 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile under Part 1 of Article 62? Why weren't you declared a particularly dangerous recidivist?

V.A.: They gave me Part 1 again because my first conviction had long been expunged. And they didn't have any concrete materials against me.

They took me to the Perm region, to camp no. 35, at Vsesvyatskaya station. I served these five years of strict regime there. It was harder there than in Mordovia. They punished you for anything. For example, for a while, I worked in the kitchen, peeling potatoes. One day, the potato-peeling machine broke down: something burned out. It ran on electricity. They accused me of breaking it. I said: “How did I break it?” “You overloaded it.” I said: “I couldn't have overloaded it, just as you can't overload this cup with water, because it has its limit on how much potato you can put in. How could it be overloaded?” But nevertheless, I had overloaded it, destroyed it, and they put me in the SHIZO (punishment cell). I served two weeks there. Or, for instance, one time I sat on my own bunk, and that was also a major violation. For that, they deprived me of a visit from my relatives. I didn't have a single visit because I was “violating the regime.”

Who was I there with? I have such good, pleasant memories. There were few Ukrainians in zone 35. The camp was small, about sixty of us. There was Stepan Khmara, and Ihnatenko from Kaniv. He was there for his religious beliefs. I have a very good impression of Natan Sharansky. He is truly a Jewish patriot and an honest, decent person. I was on very good terms with the psychiatrist Anatoly Koryagin from Kharkiv. He was released before me and went to Switzerland. He wrote to me from Switzerland, and I wrote to him, but over the years, that all ended. Now I don't even know where he is; I've lost contact with him.

They watched very closely to ensure no information got out. They didn't let letters through. Neither to me nor from me. I knew many people wrote to me, and I tried to write, but they would say: “Conventional signs in the text.” I had no visits. A whole range of products was forbidden: you couldn't drink coffee, you couldn't get sugar, no chocolate. You could buy five rubles' worth of products in the camp store, but only for good behavior and meeting the work quota.

V.O.: And what did you do there?

V.A.: I worked very hard. In the kitchen, I lost my fingernails. I had to wash dishes, and they gave us some chemicals for washing. I would stick my hands in those chemicals, and they completely ate away my nails. They later removed me from that job because I could no longer work. My nails still haven't grown back properly. I have another memento: a large hernia on my abdomen. A few months before my arrest, I had an operation in the Terebovlia district. When they brought me to the zone, I had to lift vats of slop in that kitchen, and my muscles tore. In Mordovia, I had surgery on my legs. I had varicose veins. It was a peculiar situation. I came to Mordovia as a teacher, unaccustomed to hard labor, because I hadn't had to work so hard before, and they assigned me to a brigade that loaded timber onto train cars. And all of it by hand. Winter, snow. The timber would slip; one of my friends there had his legs broken. I tried to get out of that brigade, but there was no way. But there, in the third camp, was the central inter-camp hospital. And there was a famous doctor there—Vasyl Karkhut. Do you know of him?

V.O.: I don't know him personally, but I've heard about him from Oleksa Tykhy and others.

V.A.: With his help, one could somehow get into the hospital. But I was healthy, nothing was wrong with me. Only through surgery. There was an intern there whom we called “Boogie-Woogie.” He performed operations. I had minor varicose veins on my legs. I agreed to have the surgery, and then we'd see—maybe I wouldn't end up back in that brigade, I'd get at least a little rest in the hospital. They operated on both my legs. But very quickly, literally a week after the operations, they sent me back to the zone—and to work.

I ended up in a different brigade. Also a hazardous one, also hard labor. They brought stone, cement, and lime into the zone, and all of it had to be unloaded. So I only gained a week. But gradually things changed, and I was transferred to other zones.

In the summer of 1986, they took me into exile. The transport lasted quite a long time, about a month, as they took me to the Tyumen region. By the way, they held me in the Tyumen prison for almost a month, for some reason in a punishment cell. There is a settlement there called Nizhnyaya Tavda. There is also a Nizhnyaya Tavda River. The well-known Kyiv psychiatrist, the Jewish Semyon Gluzman, was in exile in that Nizhnyaya Tavda. He had just been released, and I arrived to take his place.

V.O.: Into a warm spot. The network of informers was already in place...

V.A.: A typical Siberian river, swampy taiga all around, you can walk for dozens of kilometers through that swamp, terrible mosquitoes. The snows are deeper than in Perm.

But perestroika had already begun. I heard that people were being released from the Perm camps, that Stepan Khmara was already home. But they were still holding me. Finally, they released me too: “for good work and good behavior.”

V.O.: That was a typical justification for pardons back then.

V.A.: Yes, a pardon. It was at the end of May 1987. I left in June, having spent about a year there.

V.O.: So what did you do there?

V.A.: I did very hard work with very difficult people. At a timber mill. Sawing planks there. They placed me in lodging with some old grandmother.

V.O.: Did you get to go on leave?

V.A.: God forbid. No, no, no, it was out of the question! I was not allowed to leave the boundaries of the settlement.

They released me. In the summer of 1987, I arrived in Kolomyia. My uncle lived there. My mother was gone, and my father had died in the United States.

As a pardoned man, I again sought a teaching job. They wouldn't give me one; again, there was no vacancy for me. I went around and around, writing to various authorities—the district department of education, the regional department of education, the Ministry of Education. Finally, I wrote about it to Chornovil for his “Ukrainian Herald.” He published the letter. I also appealed to Gorbachev—Chornovil published that letter too. And still, no vacancy for me. Finally, at the end of 1988, I wrote to the United Nations, to the Commission on Human Rights, stating that I am so-and-so, now a citizen with equal rights, yet various repressions continue to be used against me. If your commission protects human rights, then protect my interests too, because in our country, people like me are treated unjustly. After some time, I was summoned to the district department of education. I saw my letter there. “Comrade Andrushko, you are seeking a job? But there is no vacancy. When there is a vacancy...” They hadn't let the letter go abroad. But I had made copies of this letter and given them to many people; this letter was probably also in Kyiv, and someone sent it to Radio Liberty. In the evening, I heard: Radio Liberty is broadcasting my letter in Ukrainian, and then in Russian. A few days later—the school year had already begun—they summoned me to the Kolomyia district department of education: “Comrade Andrushko, we are giving you a job.” I got a job in the village of Sidlyshche, Kolomyia Raion, in an incomplete secondary school. A nice little school, a small village in the forest. I worked at this school for a year. The teachers treated me well. They, of course, already knew who I was and where I had recently come from. But I was already dedicating myself not so much to pedagogy as to public affairs. I am one of the organizers in our region of the Ukrainian Helsinki Union, which I joined in 1988. I came to Kyiv for all the meetings and was a member of the UHS Coordinating Council.

I was invited to Bukovina, where I became the head of the regional organization of the Ukrainian Republican Party. I moved to Chernivtsi from the Ivano-Frankivsk region in February 1990. Thus began, so to speak, the next stage of my activity. It was a turbulent time. People were very active. I lived by those events, doing what I could. I had some publications in various media outlets.

But the most memorable thing for me at that time was when I raised our national flag over Chernivtsi University. That was on November 3, 1990. It was the anniversary of the 1918 Bukovina Veche, by which Bukovina joined the Ukrainian People's Republic. It was decided to raise the national flag over Chernivtsi on that very day. Thousands of people gathered. As preparations began, I mentioned that I had raised a flag over the university back in Stalin's time. It was the first time I had publicly admitted it. So they gave me the honor of raising the flag over the university now. I climbed up to the attic. With the help of some young men, I secured the flag over the building.

And a short time later—I don’t remember the exact date, two or three months later—the issue of raising the national flag over the Chernivtsi City Hall arose. They called on me again to raise it. There were also many thousands of people there; they gave me the flag, and I climbed high with it. I saw a sea of people below! That was probably one of the happiest days of my life. I understood that my flag over Chernivtsi University and over Bukovina would never be taken down by anyone.

There was another interesting event in my life. On May 1, 1991, I organized an anti-communist demonstration in Chernivtsi. One column gathered near the regional party committee building, while we, with our republicans and other people, made a symbolic black coffin for the CPSU and the USSR and carried it first to the regional party committee. They wouldn't let us in. So we went through the city to the bridge over the Prut, and there we threw the coffin from the bridge into the water, and people threw stones at it and sank it. After this, they opened a criminal case against me “based on a complaint from the working people about especially cynical hooliganism,” Article 206, and an investigation was launched!

V.O.: And what constituted your “especially cynical hooliganism”?

V.A.: I asked: “What was so bad about it? Was I running around naked or shouting obscenities?” “No, you were blocking traffic, committing hooliganism on the road.” They dragged out the investigation; they were, frankly, afraid to pursue it by then. A young investigator was handling it. I refused to speak with him, but in the end, with the proclamation of Ukraine's independence, the charges against me were dropped. So far, I haven't been in prison in the Ukrainian state. Although my friend Bohdan Kravchuk served two years. He is also a well-known figure in the Republican Party. On some false, fabricated charges.

In the winter of 1993, I swapped apartments and moved to the city of Nadvirna, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, 16 Lomonosov Street, apartment 14. *(The street has now been renamed: 1 Yulia Soldak Street, apt. 14. – V.A.).* I have a phone: 2-70-10.

I am mainly engaged in literary work. Last year my book “You Will Gain a Ukrainian State...” was published. It was published abroad, but not in its entirety. There are good reviews of it, here in the newspaper “Path to Victory.” Different people perceive it differently. The book is partly autobiographical, but I also raise other important issues. It's in the essay genre.

Just recently, my play “Foolish Children” was staged at the People's House in Chernivtsi. It was a success. My plays have been staged in the Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil regions. I have an invitation to Australia. *(I visited there in 2000. – V.A.)* I think I'll stage it there too. I am a member of the editorial board of the journal “Our Goal,” which is published in Adelaide, Australia. It is the organ of the League of Free Ukrainians. And before that, at the invitation of my countrymen, I visited England, Germany, and Belgium several times, in 1990, 1993, and 1994. I gave public speeches there, particularly in Manchester. There were publications about me there.

In the newspapers “Independent Ukraine,” “Path to Victory” in 1991 or 1992, and other publications, there were articles by me and about me.

V.O.: Was this when Ihor Kravchuk was the editor of “Independent Ukraine”?

V.A.: Earlier. By the way, Ihor Kravchuk is a former student of mine. And Bohdan Kravchuk too. Fate drove me for a time to the Zhytomyr region, to their village, where I met them. And then I sent them to study at Chernivtsi University. By the way, their mother is a former political prisoner. She is from Verkhovyna. And their father was from the Zhytomyr region. He died somewhere in a mine in Vorkuta.

I live in the Ukrainian state, and I cannot be accused of treason. However, there are still hostile forces that try to harm me. About five years ago in Kolomyia, a former communist printed a brochure on a computer (because no one wanted to publish it) in which he placed his supposed works. It's mostly plagiarism. He used to pass himself off as a people's poet. His name is Volodymyr Dzhygryniuk. He comes, by the way, from my village, from a very good family; his father was a Sich Rifleman. There's a saying that the apple doesn't fall far from the tree, but in this case, the apple rolled so far away that you can't even eat it, it's disgusting to even pick it up. During the Bolshevik occupation, he wrote nasty little poems for many years. And now he presents himself as a Ukrainian patriot, even supposedly a participant in the national liberation struggle. At the same time, he tries to harm people like me. Now it's difficult to say that I'm a hooligan or a thief, a state criminal or a traitor, so they compromise my father, my mother, my relatives, claiming that during the German occupation they were collaborators, worked with the German occupiers, that I come from a family of traitors. And what's most terrible? That a court in the Ukrainian state did not protect me. The case was first heard by the Kolomyia city court, and then the cassation court in Ivano-Frankivsk. And it confirmed that I come from a family of collaborators. This was in 1999. I submitted the case to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France. Such things are happening in our time! There were a number of publications about this trial, particularly in the Chernivtsi newspaper “Chas” (Time), the Ivano-Frankivsk regional newspaper “Halychyna” (Galicia) wrote about it, and there were materials abroad in the journal “Nasha Meta” (Our Goal). I am interested in having the public learn about this case. It is a trial analogous to the one that took place in Kyiv in the case of Slava Stetsko, concerning Stepan Bandera and her husband Yaroslav Stetsko, whom the communist Symonenko accused of being collaborators and traitors. Here is my complaint.

“COMPLAINT.

To the European Court of Human Rights from a citizen of Ukraine, Volodymyr Vasylyovych Andrushko, residing in the city of Nadvirna, 16 Lomonosov Street, apartment 14, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast.

Honorable Court!

The court of the Ukrainian state, to which I appealed with a complaint about the insult to my honor and dignity, violated Article 6 of the Convention regarding my right to a fair trial. The court deliberately and unjustly decided the case, compromising my relatives, myself, and Ukrainian patriots. My cassation appeal in the regional court was also not satisfied.

Based on the fact that the case did not receive a just resolution in the courts of Ukraine, I am appealing to you with this complaint.

During the communist occupation, I fought for the independence of my people, for which I was twice convicted. I was twice rehabilitated by the Ukrainian state, but it so happened that those who had previously persecuted me, who were hostile to the independence of our people, also transitioned into our state. Former communist functionaries in the modern Ukrainian state hold various leadership positions and, wherever they can, they harm our state.

I believe that the judges who heard my case are such people. As can be seen from the decision of the Kolomyia city court and the ruling of the Ivano-Frankivsk regional court, the court agrees with the slanderer that my relatives were traitors during the German occupation and collaborated with the fascists.

However, these false accusations are refuted by witnesses and documents issued by the Ukrainian state, which confirm that my relatives committed no crimes but were Ukrainian patriots and fought for the independence of Ukraine.

Your court, of course, does not have the right to punish the scoundrel-communist for his slander against honest people, but it does have the right to say that the trial that took place in my case was unjust and violates the Convention on Human Rights. This is what compels me to turn to you with my complaint.”

March 6, 2000.

The European Court of Human Rights refused to satisfy my complaint.

And here is the complaint to the Supreme Court of Ukraine. It was published in the newspaper “Chas” (Time), which is published in Chernivtsi in Bukovina, on March 17, 2000. I will read only the end:

“Strange are Your ways, O Lord! And strange are the deeds of our justice system today. I am not surprised by the behavior of Symonenko and the well-known scoundrel in Kolomyia, Dzhygryniuk—they were what they were, they are what they are, and they will be what they will be. One could even ignore them, but it becomes frightening when a court in the Ukrainian state sides with them, frightening that this is not a mistake by the court, but its conscious falsehood. I do not know how you will decide my complaint—perhaps the same as the previous courts—but prove to me that the documents that prove my relatives' innocence are false or have no direct bearing on the case. Prove that the Ukrainian state unlawfully compensated me for my father's property, which was previously confiscated by the communists. Name at least one sin, one crime of my mother, about which the slanderer speaks. One could ask other questions, but at least answer these.

And finally. I am submitting this case to your court, to the European Court of Human Rights, and to the court of public opinion. Because what happened in Kolomyia and Ivano-Frankivsk is not the resolution of some personal conflict between a communist and a Ukrainian patriot; it is a political act that has harmed not only me but other patriots as well, and blackens the idea of our independence. It is dirty water for the communist mill, which grinds poisonous meal for our people.

I hope that the public will understand and support me.”

My father was a political émigré who, like many of our people, ended up in the West during the war, in 1944. He was not an insurgent, but he was directly connected with them. He was the *viyt*, the head of the village community. And at that time, the entire local administration consisted of Ukrainian patriots. That was the directive—to put our people in power: our police, the church committee, the church, the school—these were all our people. Not like during the Bolshevik occupation, when they put all sorts of scoundrels in power. My father collaborated with the UPA, and he had been a nationally conscious person even before that. My mother had been the head of the Union of Ukrainian Women in our village. I remember that Olga Kobylyanska once visited our house. My mother, I remember, introduced me, a little boy, to her.

By the way, the famous military figure Yurko Tiutiunnyk hid in my village for several months in 1920, later forming a detachment in Poland and marching on Bazar. He was hiding with our priest. My father belonged to the church committee even before the war. Our church is old; it was damaged during the First World War. Somewhere the tin roofing was pierced, and it was leaking in the domes in the attic. The hole needed to be plugged. Everyone was afraid to climb up there. My father went up, looked to see where it was leaking, and saw that it was dripping on something. He looked closer—and it was a bundle of banknotes of a thousand hryvnias each. Maybe five hundred thousand, or maybe more, hryvnias of the Ukrainian People's Republic. They didn't know how that money got there. Only later did they recall that Yurko Tiutiunnyk had been hiding with the priest, and when the Ukrainian People's Republic was collapsing, he hid the money in the church dome.

Petro Franko, Ivan Franko's son, was in my village; he often visited our priest. And from the neighboring village of Lanchyn came the famous Ukrainian writer Yuriy Shkrumeliak. About fifty of our boys died in the UPA after the Second World War. And many from my family, my friends, and people I knew well, who had a great influence on me. I was a witness to that struggle. I was not in the UPA, but I was close to the UPA and saw this incredibly heroic struggle. I believe that in the history of our people, there has been no more heroic, more selfless struggle than the one waged by the OUN-UPA during the Second World War and in the first years after it.

V.O.: Do you have your verdicts? It would be good to get copies of them.

V.A.: I have been rehabilitated, but they didn't give me the verdicts themselves.

V.O.: Do you know that you can apply to the courts that tried you to get copies of the verdicts? You have to pay a small fee. Today, you and I went to the grave of Patriarch Volodymyr on the anniversary of his death, and we passed the monument to Bohdan Khmelnytsky. Well, Oksana Yakivna Meshko, whom we remembered so fondly today, returned from exile in 1986, went to the Kyiv court on the square in front of Bohdan, and wanted to get a copy of her verdict. They'll give it to you, but you have to pay a fee. “And where do I pay?” The policeman says: “You know where Bohdan is standing, grandma?” “I know.” “Well, with his mace he’s pointing right at the savings bank.” Look what Bohdan has been reduced to! He has a mace, like a policeman, and he's pointing with it to a savings bank! Oksana Yakivna told me this herself. She spoke very highly of you.

V.A.: I was one of the first to have contact with her. She was a special person. Once I came to her and said: “Leaflets have been distributed in Kyiv.” She had heard about it, but I didn't want to say that it was me distributing them. “A provocation!” she insisted. What was the point of proving to her that it wasn't a provocation... I thought, if I tell her it was me, she'll say I'm a provocateur. So we parted ways like that, but we had a good relationship later on as well.

V.O.: Thank you.

This was Mr. Volodymyr Andrushko. Recorded on July 18, 2000, in Kyiv by Vasyl Ovsienko.

Volodymyr Andrushko's book is titled “You Will Gain a Ukrainian State…,” Nadvirna, 1998. 132 pages.

[End of recording]

Characters: 39,300.

Photo:

Andrushko Volodymyr ANDRUSHKO

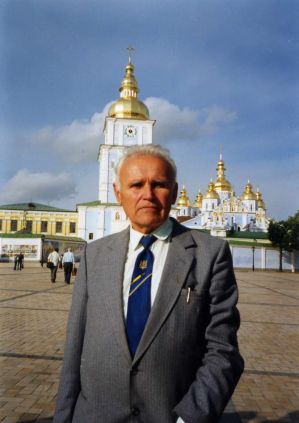

Photo by V. Ovsienko:

Andrushko1 Film 6343, frame 8A. July 18, 2000. Volodymyr ANDRUSHKO near St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery in Kyiv.