About Andriy KRAVETS

On April 2, 2000, in the village of Rosokhach, stories were told by Mykola Slobodyan, Petro Vynnychuk, and Mykola Marmus;

on April 3, by his widow Olha and son Mykola

Mykola Slobodyan: Andriy Kravets was born on March 23, 1943; he was a year older than me. His father and mother passed away long ago. He also had an older brother, Ivan, and a sister, Ivanna, who is married to Zinoviy Bezpalko. Andriy finished school here, worked for a bit on the collective farm, and later traveled to the eastern oblasts to earn some money. He was a man of Ukrainian spirit; he hated that Moscow regime. He was pained by the injustice, by the crimes of the Soviet government against Ukraine. Around him, there was always talk of how to get rid of that government so that an independent Ukraine could come sooner.

Petro Vynnychuk: I knew Andriy better in captivity, in exile. He was a very kind but firm person, persistent in his cause. He was a nationally-conscious Ukrainian. He loved to sing Ukrainian songs. He went through prison and exile, but it didn't break him; he did not fall to his knees before that Moscow regime—which proves that he was a man of strong will and firm character.

He was actually in our organization from the very beginning, but membership was counted from the moment one took the oath. I was there when, on January 14, 1973, four people took the oath: Andriy Kravets, Mykola Marmus, Mykola Slobodyan, and Mykola Lysyi. It was at Andriy's house. Leaflets were made in his house as well. On January 21, he took part in raising the flags and posting leaflets in Chortkiv.

Andriy was arrested on the same day as I was—April 11, 1973. He received 3 years of imprisonment and 2 years of exile. He served his prison sentence in Mordovia, in camp No. 17, in the settlement of Ozerny in the Zubovo-Polyansky district, together with Vyacheslav Chornovil. When Andriy was transferred to the Urals in the fall of 1975, to camp No. 37, he told us a lot about Chornovil. In April 1976, he was sent into exile to the village of Poludyonovka, Tomsk Oblast, Verkhneketsky district, Bely Yar. A year later, I was brought there too, but he happened to be on leave at home at that time.

Andriy and I met like brothers. We took an old house there that no one wanted to live in, repaired it, installed a small stove, and lived there together for just under a year. We worked on a farm every day, without holidays or days off, because there was no one to relieve us. In April 1978, I saw him off as is proper: we held a farewell party and gathered friends who were worthy of it. I remained there for another two years, while Andriy went home.

After his release, Andriy got married; his wife's name is Olha. They have three sons: Mykola, Kindrat, and Slavko (Yaroslav). The eldest has already completed his military service and is at home, the middle one is currently serving, and the youngest is waiting to be drafted.

Andriy died on September 11, 1996. He had had skin cancer since 1988. The cause of his death was liver metastasis.

Mykola Marmus: A week before his death, we visited him in the hospital in Ternopil. He was still holding on. But the doctors told us to take him home as a hopeless case—that it would be better for him to die at home. We took him home.

We all, and he too, probably, felt that these were his last days, so we made a trip out of the village to the grave of the Sich Riflemen. He could no longer walk, so he had to be driven by car; it's not far from here. We recorded it on a video camera and took photographs. Andriy tried to sing, but he couldn't anymore. He was grateful that we had not abandoned him. Soon, he was gone...

* * *

Olha Kravets: I was born on May 3, 1956. I'm from Shulhanivka in this district. My maiden name is Vitiv. Our family is a typical Ukrainian family. My mother used to be a teacher; she was in the Union of Ukrainian Women. My father had been working in Chortkiv since 1950. I first finished an accounting school, and then I completed a correspondence course at the Kopychyntsi Accounting Technical College. After that, I worked.

How did Andriy and I meet? I was working in Chortkiv, and my father's relatives lived here in Rosokhach, as my father himself was from here. So I would come here. And that's how we met. I knew that Andriy had been imprisoned and then in exile. He returned in 1978. We got married that same year. After his release, Andriy immediately started working as a laborer in Chortkiv at the regional repair and construction department.

V. Ovsienko: Did he have administrative surveillance after his release?

O. Kravets: There was no official surveillance, but they walked past our windows quite often. The district policeman would come by. And the KGB agents came by quite a bit. More than once, you'd come out of the house and hear someone walk past the house. And when you came out—they would run away.

V. Ovsienko: Were there any instances of harassment from the authorities, from the KGB?

O. Kravets: No, no one said anything to him. We didn't steal, we had no estates or luxuries, so the police didn't bother us.

V. Ovsienko: And what did you know about the 1973 case?

O. Kravets: I was in the 10th grade at the time, and I had heard about that case. They said that some boys from Rosokhach had hung flags in Chortkiv, but I didn't know any of them. Some people said one thing, and others said another. For example, they said that the KGB was now giving the whole village no peace. Some complained, others pitied them.

Andriy Kravets was born here, in Rosokhach, on March 21, 1943. He was baptized here in our church. It was Greek Catholic until 1946. He studied here at the school, finishing seven grades.

Mykola Kravets: Father finished eight grades. He said that he later attended night school.

V. Ovsienko: And please name your sons.

O. Kravets: Well, the first one is Mykola, born April 2, 1979. He has already completed his military service. The middle one, born August 15, 1980, is named Kindrat. He finished secondary school and is now in the army. And the third is Yaroslav, born February 4, 1982. He is supposed to go into the army now. Today he went to the military enlistment office because he's studying at a night institute. And he says he has to take his exams early. They say they'll postpone it until the fall, but he doesn't want to wait until the fall, because what good will that do?

V. Ovsienko: And when was Andriy's illness discovered?

O. Kravets: It was discovered 8 years before he died. It was skin cancer.

M. Kravets: Back then, they didn't even know what it was.

O. Kravets: They knew in Ternopil, but they didn't tell him to keep coming to them. It was the first stage, but he didn't have time for treatment and thought everything was fine with him. It seemed to be fine at first, but then in 1986–87, it got worse and worse. He died on September 11, 1996.

V. Ovsienko: The boys showed me a photograph—just a week before that, they had gone to the grave. Today they took me there as well.

1996—how old were you then, Mykola?

M. Kravets: I had just finished the 11th grade, so I was 16. My father was a good man. I hadn't even started school yet, and I already knew something... They told me such tall tales... My grandmother told me that my dad had thrown my grandmother into a pit, and that's why he was in prison. I knew he had been in prison, and then, when I was about seven, I found out that he was imprisoned for the blue-and-yellow flags. It became a little easier then.

O. Kravets: It was easier by then—those were the years when there was a little bit of freedom. In 1988, there was the 1000th anniversary of the baptism of Ukraine, and in the fall, the Catholic Church came out from the underground. They gave a little bit of freedom then.

V. Ovsienko: Mykola, when you were still in school, did any of the teachers or other people try to reproach you because of your father?

M. Kravets: No, no one said anything like that, as if nothing had ever happened. All the teachers here were from the village. When I was younger, they didn't want to say anything, and I didn't know the truth. And when I got older, there was no need to say anything—everyone already knew.

O. Kravets: We don't have teachers like that. There used to be, but not anymore.

V. Ovsienko: Did your father tell you about the trial, the imprisonment, the exile?

M. Kravets: He said that when he was tried, no one was allowed into the courtroom of the oblast court. And when the verdict was being read, the lights in the courtroom went out.

V. Ovsienko: They had their verdict announced to them by candlelight—just as they had taken their oath of allegiance to Ukraine, so too was their trial conducted—by candlelight.

M. Kravets: I've read the verdict; I know a few things. My father said that there, in captivity, there were good people too. He said that he was imprisoned in Mordovia, in camp No. 17, with Vyacheslav Chornovil—they were together for six months. And then they transferred Dad to the Urals.

V. Ovsienko: The best people were gathered in the political camps. It was hard to find such people in freedom, but there they were, all ready, all caught... In exile, communication was harder, because everyone there was a stranger. He was lucky that they also sent Petro Vynnychuk to the same place, to Poludyonovka in the Tomsk Oblast.

O. Kravets: Right after Andriy left for Siberia, it was supposedly hard, because the place was saturated with criminal exiles, and the local people couldn't know who was who. But after they got to know him, they treated him normally, and he was fine among them.

V. Ovsienko: And where do you work?

O. Kravets: At the school, as a maintenance worker. And the boys don't have jobs.

M. Kravets: There's no work here. Maybe there is work, but you have to look for something better, because our financial situation doesn't allow for low earnings. If they pay me 80 or 90 hryvnias, will I be able to pay for gas, for electricity? Because you have to pay for everything, and you have to have something left for yourself. That's why I need to look for a better job. You can go somewhere for seasonal work when the season starts.

Right now, my middle brother, Kindrat Kravets, is serving in Yavoriv, Lviv Oblast. He should be coming home soon; his service is almost over. And my younger brother, Yaroslav, is currently studying at the Institute of Entrepreneurship and Business in Chortkiv—it's a branch of the Ternopil Academy. He's also supposed to go into the army soon.

I read about my father in the Ternopil newspaper *Vilne zhyttia* (Free Life).

M. Kravets: The Chortkiv district newspaper *Holos narodu* (Voice of the People)—there was an article there too.

V. Ovsienko: Kyiv's *Molod Ukrayiny* (Youth of Ukraine) published an article by Volodymyr Marmus, “Flags Over the City”* (*No. 7 (17638), January 22, 1998. – V.O.).

And was Andriy rehabilitated?

O. Kravets: He was rehabilitated, he had a certificate of rehabilitation, a few of those benefits, but they canceled all of it—they say there are no funds. I've already gone to the district office.

V. Ovsienko: He was also a member of various organizations—when “Memorial,” the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, the People's Movement (Narodnyi Rukh), and the Ukrainian Republican Party were being formed...

O. Kravets: He didn't pay much attention to it because he didn't have time—he had a lot of household chores, and he wasn't healthy. But he still took part.

Published in:

Youth from the Fiery Furnace / Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Compiled by V.V. Ovsienko. – Kharkiv: Folio, 2003. – pp. 93–97.

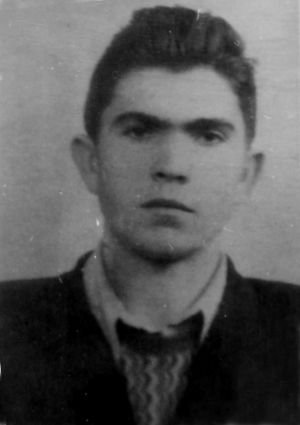

Photo:

KravezA Andriy KRAVETS in his youth.

Photo by V. Ovsienko:

KravecO Film 9770, frame 30, April 3, 2000, v. Rosokhach. Andriy KRAVETS's son Mykola and widow Olha.