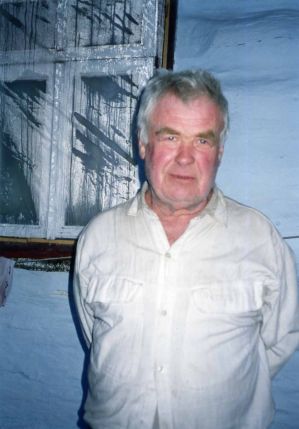

V.V. Ovsienko: Dmytro Kvetsko is speaking on February 4, 2000, in Sloboda-Bolekhivska, Dolyna Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Recorded by Vasyl Ovsienko.

D.M. Kvetsko: I, Dmytro Mykolayovych Kvetsko, was born in this village, Sloboda-Bolekhivska, in this very house, on November 8, 1935. I was named Dmytro, although we already had a Dmytro—my uncle. But since I was born on St. Demetrius’s Day, they named me Dmytro anyway, despite my uncle already being a Dmytro. And so we lived in our family, because my uncle was close with my father. And our fates, to some extent, were very similar—not just our names.

My uncle, Dmytro Kvetsko, was a nationalist and was persecuted back when this was Poland. The gendarmes beat him for raising a trident on the cross here with his comrades. The Germans seized him as a Banderite and held him in Auschwitz. The Americans later liberated them. From Auschwitz, the Germans were marching them to another concentration camp somewhere in West Germany. The column was bombed, the guards fled, and the Americans, riding in tanks, stopped the entire column. My uncle was with the Americans and recovered a bit there, because he looked terrible (the Germans were also very cruel to nationalists).

When my uncle returned from American captivity, he immediately joined the Banderites, in the Security Service, and after that, sometime in 1946, he was stunned by a grenade in a hideout—they blew themselves up. He was caught and also beaten very severely. He spent 10 years in the concentration camps in Inta, working in a mine there.

And my aunt Nastunia, his sister, was also arrested then for her connection to her brother. She also served 10 years in concentration camps in Gorky Oblast, at a logging site. So, they were fighters for an independent Ukraine before me, and I continued their family tradition, so it wouldn't be broken. Such was the fate of our family.

My father helped the underground and was also, in fact, driven from this world by the Bolsheviks, and they were the death of my mother when I was still little. So our whole family was in the national liberation struggle.

I don’t even remember when my father and mother were born, because I was still young when they died. My mother was Kasia, Kateryna that is. My father, Mykola Kvetsko, served in the Polish army. After that, during the Polish-German war in 1939, he was mobilized as a cavalryman and was immediately captured by the Germans at the front. When he returned, he didn’t join the UPA, the nationalist movement, because Dmytro had already joined. Dmytro said that someone needed to manage the farm. My father stayed at home in a legal status but always supported the movement. He and my uncle worked together so closely that there were no secrets between them. I emphasize again that our entire family was nationalistic, though not highly conscious, as no one had a higher education. But both my uncle and my father were in the movement. They wanted to deport us, so we fled and hid, and sometimes we bought our way out because we had a farm, we distilled horilka, and those from the garrison would come, we’d give them a bottle, and so we fought them off with that horilka. We were supposed to be deported because of my aunt. There was a certain Kulakov here, and this Kulakov came and inventoried and took all of my aunt’s property, conducted a so-called confiscation. But since they drank here, they knew that if they deported my father, no one would give them a bottle of moonshine anymore. So they carried out the confiscation nominally: they took all my aunt’s clothes and suitcases and carried them to the garrison. That was considered as if we had been deported. So they left us alone.

But my father also died because he fled to the forest, caught a cold in the forest, and got pneumonia, which led to consumption, tuberculosis, and he died of tuberculosis in 1953.

And my mother, somewhere around 1945—the roundup squads came and were shooting, and my mother got so frightened that from that terror she contracted some incomprehensible illness at the time, which there was no one to treat, and she died. I was 10 years old then. And after that, my father married a second time. My second mother was Maria, and with her help, I barely managed to finish school—it was so hard for me to finish school that I barely made it. Because we were so ruined by both the Banderites and the garrison. Because the Banderites would pass through, drink here all night, and the next day the garrison would come... It’s called Potik. It’s a hamlet where it was convenient for both the roundup squads to cause trouble and for the Banderites to come at night, because the garrison was far away and blocked off from there. We lived in constant fear, suffering from both sides.

But when I finished school, a certain love for politics, for history, awoke in me. I also came across books from “Prosvita.” The “Prosvita” library in our village hadn't been confiscated; people had taken the books to their homes, and then, through various paths, those books fell into my hands. I was very fond of books. I remember the first book a teacher gave me when I started school was Tchaikovsky’s “On the Outposts.” It touched my soul so deeply. That’s what instilled in me a love for history and politics.

We had a very good teacher from Vytvytsia, Taras Lypetsky. Five of his brothers joined the movement, and all of them perished. And he died right here, not far away, near Lyshor (?). The bunker where he died is still there. He taught me. He was a great nationalist and sensed that I was imbued with this spirit from childhood. Because when my mother sent me to the first grade, he fastened (Pinned on. – Ed.) a large trident to my chest and dressed me in blue shorts and a yellow shirt. He even let me grow my hair long—all the other children had short haircuts, but I had long, blond hair. He gave me a book. He had some kind of sympathy for me. I had no idea then what awaited me in the future. But the fact that I wore a large trident on my chest, woven from beads by my mother, and that blue-and-yellow outfit—it impressed him so much that he showed some sympathy for me.

When I finished school, I didn't yet have an inclination for politics, but literature, including underground literature, kept coming my way, and it was this that awakened a lifelong interest in history and politics.

I finished the seven-year school in Sloboda-Bolekhivska in 1948 and the Vytvytsia secondary school in 1953, the year Stalin died.

In 1954, I went to serve in the army, in the so-called Soviet Army. I didn’t yet have an awareness of my nationality or an inclination to oppose the existing system. In school, I joined the Komsomol, because everyone was dragged in, whether you wanted to or not. And anyone who didn’t want to was expelled from school. And in the Komsomol, I sort of integrated into that system. That system offered some hope that things would get better, because things were indeed getting a little better. It seemed to me that within that system, one could achieve something better, that it was possible to come to terms with it, that it wasn't so bad after all: they gave us an education, they didn't forbid us from speaking our language, we were allowed to read Shevchenko or Franko. I thought that one could reconcile with that.

But when I arrived in the army—and I arrived in Perm, which was then still Molotov—the picture was completely different. There I immediately saw that we were being nationally humiliated, humiliated at every step. The majority there were Russians, and there were relatively few of us, Ukrainians. The Russians ran everything; they felt they were in their own environment, while we were in a foreign one. We would gather separately, but in a way that didn't draw attention, because everyone was afraid. There I saw that there was a whole chasm between us and them, that they belittled us as people, treated us as the lowest grade, as some kind of servants or slaves. It was insolent and crude.

The officers especially sensed an opponent in me. I was sent to sergeant school. There, the school commander, a lieutenant colonel, spoke directly about me: “That one is a nationalist. He,” he says, “knows all the American farmers, but his weapon is always rusty. Nothing of ours. He is a stranger to us.” The result was that they didn't graduate me as a sergeant but assigned me the rank of yefreytor and sent me to a battery. The sergeant school had a relatively intelligent environment. It trained calculators and scouts. I was a calculator, working with instruments in artillery systems, howitzers and mortars—a 122-millimeter howitzer and a 106-millimeter mortar. There were people there with higher education; I already had a secondary education. But in the battery, the contingent was old, and they trampled on me there like the lowest scoundrel, someone they thought wasn't even worth considering. A protest was born in me, but I couldn't find a way to express it.

As a Komsomol member, they would make me stand guard by the banners, and there you had to stand, as they say, at the “attention” stance. And they constantly put me there. Whether at headquarters or in the camps we went to for summer training in the Chelyabinsk region—I was always standing there, because I was practically useless for anything else. I was too educated to learn their science, and unnecessary because that science and those batteries weren't used much. Except maybe for live-fire exercises, our commander would take me to the battery, I would prepare the data for him, and as soon as it was used and the artillery had fired, all the artillerymen would clean their weapons, because everything was dirty, in mud, the barrels were full of carbon after firing. And where did I fit in? I was no longer needed because I was a calculator. So, as a Komsomol member, they put me by the banner. But on the other hand, it was a very good place for me to think, because there was no work to do. So I began to think.

At first, I wanted to shoot those officers with an automatic rifle, just to get revenge. But then I thought: what would I get out of that? There are plenty of those dogs; I’d shoot some, others would shoot me, and that would be it. But what if I came up with some kind of organization when I returned? And that’s when the idea of the Ukrainian National Front was born in me. Back then, in the summer of 1956, it wasn’t so clear, but I had already sketched out the scheme. The 20th Congress of the CPSU, where Khrushchev spoke out against Stalin, and especially the events in Hungary, helped me a lot. They even took away our radio receiver then so we couldn't listen. But we immediately saw that things weren’t as fine and dandy and not as strong as they taught us in political classes.

When I returned from the army in 1957, the organization was already schematically developed, and the name of the journal was there. Melen (Myroslav Melen, born June 13 [in the verdict—September 13!] 1929 in the village of Falysh, Stryi Raion, Lviv Oblast. Member of the OUN Youth, arrested Sept. 23, 1947. Sentenced in Lviv on June 23, 1948, under Art. 54-1a, p. 8, 11 to 25 years. Participant in the Norilsk Uprising. Released July 12, 1956. Member of the Ukrainian National Front. Arrested March 23, 1967, imprisoned under Art. 62, Part 1 for 6 years and 5 years of exile. Released in 1973. Currently lives in the city of Morshyn) is trying to claim credit for it—he has absolutely no connection to it. He claims he gave the journal the name “My Fatherland”—he gave it nothing.

V.O.: He didn't tell me that when I was recording him yesterday.

D.K.: Well, he didn't say it because he sees that no one believes him after all that... But when I say it, I know, because he published it in some journal.

In short, I came home—the scheme was already there. But I still needed knowledge, so I enrolled in correspondence courses at Lviv University. And at the same time, I started working as a teacher. Actually, I had enrolled in the history faculty before the army, but I got an academic leave and effectively began my studies after returning in 1957. While I was studying, I encountered different people with different ideas, but I tried to hide my own thoughts and put my notes aside. Because I had to work a lot on myself, and there was work at school. This distracted me a bit from that idea.

I studied by correspondence and worked in various villages. In Roztoky, in Kalna. Besides history, I taught whatever subjects were assigned to me. Sometimes it was manual labor, physical education, I even taught a little math—whatever they loaded me with so I could study and finish my degree.

But when I was close to finishing, events happened that stirred me. In 1961, here, apparently on St. Michael’s Day in November, the future members of our organization, Mykhailo Dyak (Born Aug. 23, 1935, in the village of Kalna, Dolyna Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast – died Aug. 18, 1976. Member of the Ukrainian National Front. Imprisoned on March 22, 1967, on charges of treason and creating an anti-Soviet organization (Art. 64 and Art. 56, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR) for 12 years of deprivation of liberty (5 years in prison, 7 years in strict-regime camps). Released as chronically ill on June 2, 1975. Buried in his native village) and Mykola Fediv, raised a blue-and-yellow flag over the village council in Vytvytsia. I started to think: “What is happening here? Someone is already fighting. And if someone is fighting, then I shouldn’t just sit around either.”

I started thinking about what I could do. I decided that I could write, especially since some materials about the Banderite movement had already fallen into my hands. I wrote and wrote, especially in 1962. Throughout the autumn of 1962, I was writing the future program of the Ukrainian National Front. I was working as a teacher in Kavna at the time. They call it Kalna now, but the old name of the village is Kavna, and I believe it should remain Kavna. I once mentioned in Kavna that they should put up a sign on the spot where I was writing. It was on a hill in a small wood. I would go there with my notebooks and lie in the sun. The autumn of 1962 was very beautiful, dry and warm; I don’t remember another autumn like it. That was the time of the so-called Cuban Missile Crisis, when Khrushchev secretly brought missiles to Cuba, and Kennedy made a conflict out of it. All of this pushed me to work faster.

When I was graduating from the university in 1963, the program was already written. It was two thick notebooks. I decided to show these notes to someone. There was a teacher here, reliable in my opinion, whom I trusted. It was Bohdan Ravliv from Vytvytsia. I was sure that he was honest and decent. I knew he couldn't inform on me simply because of his decency and principles. When I gave him the notebooks, he returned them to me later and said: “I can’t make anything of this, it’s written in such a way that I don’t really get it. I’ll find someone who can help you figure it out.”

In 1963, when we were at a teachers' conference, around August 25, he said: “Come with me—I’ll show you the man.” “Where to?” “To Stryi.” We hopped over to Stryi (we were spending the night at a school in Bolekhiv). Before settling down to sleep (we didn’t even stay until the end of the conference), we had just enough time to go to Stryi and come back. In Stryi, Ravliv introduced me to Zinoviy Krasivskyi. (Born Nov. 12, 1929, in the village of Vytvytsia, Dolyna Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast – died Sept. 20, 1991, in Morshyn. In 1949, sentenced by the OSO to 5 years of imprisonment and lifelong exile. Released in 1953 under an amnesty. Member of the Ukrainian National Front. Arrested on March 24, 1967, on charges of treason and creating an anti-Soviet organization (Art. 64 and Art. 56, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR) to 12 years of deprivation of liberty (5 years in prison, 7 years in strict-regime camps) and 5 years of exile. In 1972, in Vladimir Prison, charged under Art. 70, Part 2 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”) and sent to a psychiatric hospital, released in July 1978. Member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group since October 1979. Arrested on March 12, 1980, and sent to serve the remainder of his 1968 sentence—8 months and 7 days in camps and 5 years of exile. Spent a total of 21 years in captivity).

My first impression was that he was such an unimpressive little man, so small, even his manners and movements were not very imposing or solid. But it is what it is. I said I had some writings and asked if he would take a look to see if they were worth anything. He said: “Bring them to me in Morshyn—I have a house in Morshyn with my brother-in-law. I’ll take them and look them over. You can come to me in Morshyn anytime.” And he gave me his address.

Well, fine, so within about a week, I took those two notebooks and went to Morshyn. I went to the place. I saw two men—one small, the other bigger, their pants rolled up, stomping around in the mud, just stomping... Those mud-stompers, again, didn't inspire much hope in me. But since there was nothing else, I reconciled myself to it. They were stomping around because they were building a cinder block house, and to bind the blocks, they needed a thick clay. So they were treading in that clay. Well, the little mud-stomper took my notebooks and said with an eager, smirking tone: “Alright, I’ll look all this over. Come back in about a month, I’ll give you an answer.” And that was it, I left.

I showed up at the agreed-upon time and asked: “Well, my dear sir, what’s the verdict on all this?” He said: “This all needs to be reworked. The sentences are long, a lot is written, but there aren't many ideas—it needs to be reworked.” I said: “Fine, I’ll rework it—that’s a technical matter for me. But will you type something for me—since you have a typewriter?” He had a typewriter; he taught typing courses at the Bolekhiv House of Culture. He said: “I can’t type that on my machine because the police have imprints of the letters. And what you have is something that shouldn't fall into the hands of the authorities. So I can't promise you anything. But take it and rework it. You can show up from time to time. I have a library, I’ve settled in a bit here, the house will be finished soon. So you can keep in contact with me, but I’m not promising you anything.”

Alright. But then another person came our way...

V.O.: And who was the other mud-stomper?

D.K.: Melen! Melen was hopping in the mud like a rooster, with such joy, and smirking. (Kvetsko laughs). I thought to myself: “My God, my God! How are we supposed to build an independent Ukraine with these two mud-stompers...”

V.O.: They’re building a house, one for the two of them...

D.K.: Well, they’re building a house, but I wasn't concerned about a house—I needed an underground, and the underground wasn't moving.

V.O.: A house is also a part of Ukraine!

D.K.: But we came across a rather interesting man. A certain Tadyk, Tadei Ilnytsky, came from Lviv to see Bohdan. In Poland, he’s Tadei, but we call him Tadyk. Tadyk is a nationalist and served time for being a Banderite. Tadyk has big plans and wants to realize them with us. What did he have in mind? First—about those “liars” that hang on the posts. He says he has equipment that he can throw onto the wires when the “liars” go silent, and he could transmit a nationalist statement, even throughout the whole oblast, over those public loudspeakers. He says he’s the manager of a shoe store and has connections. That’s the first thing he can do. Second—he says he can steal a mimeograph from some organization. He’ll drive up in a car, but he needs a man to help him. I said I would give him a man. I found such a man, but it was all a terrible escapade. I said that this escapade could end badly for us, that we would accomplish nothing and only expose ourselves. Therefore, while approving of the ideas, I didn't agree to carry out such an adventure. Then he says: “Boys, if you want to do something, I can help you with what? I have type and I have printing ink. I have a colleague in the printing industry who constantly steals ink from there, and type, but you can't steal much from there, he's constantly stealing a few letters at a time, and quite a lot has accumulated—there's a whole box of type.” I said: “Good, give it to me—I need that.”

He brought the printing ink and the type. And here I started to think: “Aha, Krasivskyi doesn’t want to type, says he won’t do anything until the house is finished. So, something has to be done without him.” The idea was burning inside me; I couldn't sit still. And here in Kavna, two of the blacksmith's children went to school. And someone, maybe Bohdan Ravliuk, advised me: “Go talk to the blacksmith—he’s reliable, his brother died as a partisan.” So I went to the blacksmith. At first, he thought that since I was a teacher, it might be some kind of provocation. But later he admitted to me that he was indeed a nationalist. I told him: “I need to set type—I have the letters, but I'm missing a frame. Do you know about such things?” “Sure, sure, I’ll make that frame! You just buy me some iron rulers, and I’ll do the rest.”

And indeed, when I gave him those rulers, he made a typesetting frame. After that, I also persuaded him to carve “Will and Fatherland” for me on rubber—in a line, with a trident on the side. I cut out the trident from a Banderite brochure and gave it to him, because he had already forgotten what the trident looked like. He made it for me.

I took that frame, I took those letters, I took the title he carved for me—I took all of it to Krasivskyi, because the house was practically finished. He took it, grumbled something, said neither “yes” nor “no.” At our next meeting, he said: “Nothing will come of this, we need to buy a new typewriter, one that isn't registered with the police, and on that machine, we can print something. I have a brother in Moscow, I'm going to see him. If you have money, give it to me—I'll buy a typewriter, bring it back, and we'll print something.”

I gave him 100 rubles and asked him to add the rest if the typewriter was more expensive. Because he had a miner's pension and wasn't poor. He went and brought back a typewriter—a large German “Optima.” Since the typewriter had a Russian keyboard, he had a few of the Russian letters re-welded into Ukrainian ones in Lviv—he knew how to do that. And so we had a typewriter. I had already reworked the materials as he had told me, and added some more things. We sat down upstairs in his library and started printing the journal “Will and Fatherland.”

V.O.: And when was this?

D.K.: The first issue came out in October 1964. We printed up to five issues at his place. We would put 6 copies in the typewriter at a time. And we divided them like this—he would take the first, I the second, he the third, I the fourth, he the fifth... I didn't take the sixth, because the impression was already poor. So I left the sixth one for him, and what I had was enough for me. That's how we worked. But after some time, he didn't want to print anymore. It was a trivial reason, but he didn't want to continue printing at his place because he was afraid.

V.O.: Maybe because the typewriter makes noise...

D.K.: But he had his own typewriter. Everyone knew he had a typewriter. There was a niche in the wall for our typewriter, and his stood next to it.

I’ll tell you, since we’re on the subject, what one of the reasons was. I was working in Kropyvnyk at the time. I ate at the school. At school, they only served food to the children at lunchtime. I ate lunch at school, and for the evening, I would take some borscht in a pot and a cutlet on a plate. I paid for all of it. And in the morning, nothing, because my landlady was ill and couldn't cook for me. She let me stay in her house but couldn't cook. You understand, they don't give large portions at school, and I was a healthy lad and wanted to eat a lot, especially back then, when I was young. So I lived half-starving like that. I come to his place—and Zenio ate very little, just licked his plate like a cat. And his wife would cook these miniature, fancy pyrohy and also serve bread and coffee. The coffee had to have a skin on it, that foam from the milk. They would buy that. So I didn't get my fill there either, because I was somehow ashamed. But one time she served those fancy miniature pyrohies—he ate a few, she ate a a few, and I ate my portion, however much they gave me. And then she brought out fine white bread—fresh and good. And she brought butter and that coffee. Here I had no limits, because everyone cut their own bread and took butter to spread. I cut off a large piece of bread and spread a thick layer of butter on it. Zenio saw this and said: “Look, some people don’t eat bread with butter, but butter with bread.” And I said: “Zenio, that’s what butter is for, to be eaten.” And Zenio just grunted and said: “Smear Fedio with honey, but Fedio is still Fedio.” (They laugh).

And after that, he said: “That’s it, I’m not printing.” I asked why, and he said: “Well, I’m scared, it’s not safe here, there’s a communist across the street, he might be watching me. I’m not going to print—and that’s final.” You’re not going to print—so the organization is done for. I grabbed my head—this was a huge problem! My whole life was directed towards the underground—and now it all collapsed. But I looked for some way out, I searched in the villages for a house where we could print—I would have to ask him to go there, he would come, and we would print. No village was suitable. People would sell you out. Even reliable ones—they were afraid. Some were afraid, others were inclined to sell you out.

And then I came across a man from our Sloboda—it was as if God brought him to me. He said: “I found a chest with Banderite literature. Come, I’ll show you.” He led me into the forest—and sure enough, a chest full of Banderite literature. Moreover, there was a large bunker there, where a Banderite printing press had been. He even found some type there and gave me a few pieces—there were lots of letters in Kolomna [or Kalna? Unclear]. Maybe someone had scattered them, or what, but he found a few there. Obviously, the roundup squads (because they weren't stupid) understood that if there was a printing press there, then there must be literature somewhere nearby. And when the Banderites were defeated, there was nothing in the bunker. So what did they do? They set the forest on fire. They thought to themselves: if the literature is hidden somewhere, then when the forest burns, the literature will burn too. They set it on fire—the whole forest burned down. Oh my! There were still such beautiful, charred trees standing, it was a pity to look at that burned forest. But when the forest was burning, the chest didn't burn—it was slightly charred on one side, but because it was in a stone niche, with a stone slab on top and stones on the sides, even though the stones got red-hot, only one little edge of the chest smoldered.

V.O.: But the chest was wooden, right?

D.K.: Wooden. It was probably from German shells, or something. Probably German, because it was made not in the Russian way, but in the German way. Besides, the lid was covered with sheet metal on top. When the forest burned, the heat from the stones only charred the edge. Well, mice had gnawed a bit, damaged some of the literature, but there was so much literature in bundles...

V.O.: And how big was the chest?

D.K.: Oh, it was a large chest. It might have been a meter and a bit by a meter and a bit. And about a meter high.

V.O.: And what kind of literature was in there?

D.K.: Well, most of it was brochures in Russian, “Who Are the Banderites and What Are They Fighting For.” Also, the “Information Bureau of the UHVR” and agitational calls and appeals like “Ukrainian Teachers!”, “Ukrainian Children!”, “Peasants of Ukraine!”. They were called upon to fight the occupier. A lot of it was wrapped in sackcloth, tied up, and stacked on its side in the chest. I went through it all, closed it up again, and said: “Let it stay, I’ll take care of everything here.” And when Krasivskyi refused to print “Will and Fatherland,” I went to that man and said: “My friend, we have to dig a bunker, there’s no other way out. We have to equip a bunker, because that one won't print at home, and I don't have another place.” He said: “Alright, alright, we’ll build it.” And he himself was a stove-maker and a craftsman.

V.O.: And what was that man’s name?

D.K.: Dmytro Yusyp. He’s here, I can take you to him. He’s still alive. I never gave him up, so no one knew about him, and he remained free. And the bunker was built solidly.

V.O.: Did you restore an old bunker or build a new one?

D.K.: No, a new one. There was nothing to restore there. We had been to old bunkers. The old bunkers, first of all, were huge, and secondly, restoring them would have been pointless. Why would we need a large bunker? It's a big pit, you can't build it so the sides don't bulge. We built a completely new one. On the spot where we started digging the pit, a huge fir tree had fallen, its roots tore up the ground, and the rest of the trunk fell across a ravine. Two ravines met there, and we dug on a small promontory, a place that was hard to get to, so no one would stumble upon it. Two ravines converged, and the trunk lay across one of them, you could walk over it. And from above, a branch hung down, which also made it inconvenient. The ravines were deep, and on that promontory, we dug the bunker. We dug it out and equipped it so that inside there was a table and a cot, so you could lie down or sit. We equipped it solidly.

V.O.: And what was its area, your bunker?

D.K.: The area wasn't large—there was a small table, a place to sit and lie down. I think it was about two and a half by two meters, and up to two meters high. So you could even walk around in there. Moreover, water seeped inside, so you didn't have to go out for water.

So we started moving everything into the bunker, but it turned out to be very cold there, because of the water and the terrible dampness. Somewhere in Stryi, Krysa welded a stove, Zenio brought the stove, and we moved it into the bunker to heat the place. I moved the typewriter from Zenio's there, paper—in short, everything needed for the work. The typewriter stood on the table, we used a candle for light, and we printed. We would go there at night to print. And we walked in such a way that no one could track us. We would leave from my house, Zenio would come here, and from here we would go up that mountain on secret paths.

V.O.: How far is it from your house—if not in kilometers, then in walking time?

D.K.: It would be, probably, 5 to 7 kilometers, no less. Because it's a climb up a huge mountain, and then you have to walk along the slope—it's far.

V.O.: In the mountains, distance is sometimes measured not in kilometers, but in walking time.

D.K.: Well, we didn't time ourselves, but I emphasize again that you had to climb a big mountain. We would go there at night and work. As a result, we published 16 issues of “Will and Fatherland,” and after that, we also sent a “Memorandum to the 23rd Congress” in Moscow, sent letters to Shelest, Shcherbytsky, and Liashko. We also sent statements about the arrests in Ukraine... No, that was a press conference, there's a lot to say about that, I'll skip it. So, we also distributed 50 statements in Kyiv. And later, when I heard that Kachur was arrested in Donetsk... Mykola Kachur, my relative, to whom I gave literature which he distributed there—he was caught there with that literature. And even before that, as Anatoliy Rusnachenko has now researched (See: A. Rusnachenko. The Ukrainian National Front—an underground group of the 1960s. // Ukrainian Historical Journal, 1997, No. 4; A. Rusnachenko. The National Liberation Movement in Ukraine.— Kyiv: Vydavnytstvo im. O. Telihy.— 1998.— pp. 105-140), Lesiv (born Jan. 3, 1943, in the village of Luzhky, Dolyna Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast – died Oct. 19, 1991, in Bolekhiv, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Arrested March 29, 1967, sentenced for treason (Art. 56, Part 1) and creating an organization (Art. 64, Part 1) of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to 6 years of deprivation of liberty. Released March 29, 1973. Member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group since October 1979. Arrested Nov. 15, 1979, on fabricated charges of drug possession (Art. 229-6, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR), sentenced to 2 years of deprivation of liberty. In May 1981, arrested again on the same charges, imprisoned for 5 years. Poet, priest of the UGCC. Died in a car crash. Buried in Bolekhiv) had messed up, because the teacher to whom he gave the journal took it to the KGB. So, by the summer of 1966, we were compromised.

V.O.: But you held on for so long! It’s amazing that it was for practically three years!

D.K.: Yes, yes, three years. The journal came out in 1964, but we started, I believe, in 1963, when I met Krasivskyi in Stryi. I believe that when more than three people know, it's already an organization. Those people were already there: Ravliuk, Krasivskyi, Melen.

V.O.: Did you print one set of the journal or several?

D.K.: No, just one—that was 6 copies.

V.O.: And were these journals reproduced somewhere else or not? Did anyone retype them?

D.K.: I don’t think they were retyped. Everyone was too scared—the material was terrifying. You can read that Program today—it’s so anti-Soviet, anti-communist, it was frightening. People’s hands would tremble, especially the older ones. Some people who read it would tremble and say they had a liver ache, or an ulcer. (Laughs). It was only in our group, where Dyak, Kulynyn (Vasyl Ivanovych Kulynyn, born Nov. 21, 1943, in the village of Lypa, Dolyna Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Member of the Ukrainian National Front since July 1966. Arrested May 26, 1967, charged under Art. 56, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR (“Treason”) and Art. 64 (“Organizational activity”), sentenced to 6 years of imprisonment in strict-regime camps. Released May 22, 1973. Currently lives in the village of Nyzhni Torgai, Nyzhnosirohozky Raion, Kherson Oblast.) and Lesiv worked—and they worked with young people—that the youth didn’t know what Stalin’s concentration camps were, so the journal was passed from hand to hand. But in the Lviv group, the older people's hands would tremble like this as soon as they took it.

I don't think these matters gained widespread publicity. But I believe that wasn't the main thing, because we couldn't overthrow that regime, which held almost half the world in its sphere of influence, with some underground organization. The main thing was the fact itself—that we continued the struggle waged by our predecessors, from Mikhnovsky to Stetsko and Bandera. Because when Bandera was gone, there was practically no one to take up that banner and carry it, because they were bickering there and still are—they created a Banderite OUN, a Melnykite one, then some “dviykari,” and who knows what else they spawned, and they were always squabbling over trivialities. But we raised that banner in the sense that we placed the struggle on a completely new foundation, on new realities. We fought for national socialism and for an independent Ukraine. It was, in fact, the forerunner of what is called dissidence or the Sixtiers movement. But dissidence and the Sixtiers movement were cultural in nature, while we were political. We, so to speak, supported the continuity, we drew a red thread to dissidence. We, so to speak, rose up on the shoulders of dissidence. Dissidence stood on national culture, on language, and we stood on its shoulders and raised political issues. Because that’s how it was—in 1965, they arrested the Horyn brothers (Bohdan Horyn, born Feb. 10, 1936, imprisoned Aug. 25, 1965, under Art. 62, Part 1 for 3 years. Art historian, People's Deputy of Ukraine of the 1st and 2nd convocations; Mykhailo Horyn, born June 17, 1930. One of the leaders of the Sixtiers. Imprisoned Aug. 26, 1965, under Art. 62, Part 1 for 6 years, a second time on Nov. 3, 1981, under Art. 62, Part 2 for 10 years and 5 years of exile, released July 2, 1987. Member of UHG, UGS, People's Deputy of Ukraine of the 1st convocation, chairman of URP in 1992-95, now chairman of the Ukrainian World Coordination Council), Masiutko (Mykhailo Masiutko, born Nov. 18, 1918, in Chaplynka, Kherson region – Nov. 18, 2001. History-Philology Faculty of Zaporizhzhia Pedagogical Institute. Writer. Imprisoned: 1937-42, 1965-71. Book of memoirs “In the Captivity of Evil” (1999), short stories “Pre-dawn Alarm” (2003)), a whole mass of people were arrested. And that’s precisely when we began our most turbulent activity. We were not dissidents in the pure sense; we were national democrats. So our merit is that we combined nationalism with democracy, and national democracy is now effectively the foundation of our state. I believe that the Ukrainian National Front was the first national-democratic party that put forward political demands, the demands for an independent state, when no one else was doing so. Dziuba wrote “Internationalism or Russification?” and Krasivskyi insisted that we should reprint it, but I said: “Under no circumstances, because in it he praises how great Lenin was, and that the Leninists are the scoundrels. I believe that both Lenin and the Leninists are scum.” I wrote a review of that book called “The Theory and Practice of Colonizers on the National Question.” It's in the journal, you can familiarize yourself with it.

Even Lukianenko (Levko Lukianenko, born Aug. 24, 1928, imprisoned Jan. 20, 1961, for 15 years under Art. 56 and 62, Part 1 for creating the Ukrainian Workers' and Peasants' Union, a second time on Dec. 12, 1977, under Art. 62, Part 2 for 10 years and 5 years of exile as a founding member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. Released in December 1988. Chairman of UGS, URP, Ambassador of Ukraine to Canada, People's Deputy of the 1st-4th convocations) in his program, on the one hand, says that Marx is fine and does good things, and on the other, says that it’s all bad. Are you stupid and don’t understand that they write these things not to act on them? That what is written is completely different from reality? In reality, there is a terrible totalitarian dictatorship, a despotism—and what is written is that there will be an earthly paradise: no state, no classes, everything will be like in the heavenly paradise—there’s Adam, there’s Eve, there’s an apple, and there’s a serpent.

And they made a big mistake in not seeing the difference between theory and practice, believing that if there is a good theory, there will be good practice. Both Dziuba (Ivan Mykhailovych Dziuba, born July 26, 1931, one of the leaders of the Sixtiers. Author of the book “Internationalism or Russification?” (1965). Arrested April 18, 1972, sentenced under Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to 5 years in camps and 5 years of exile. In October 1973, he appealed to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the UkrSSR for a pardon. Released Nov. 6, 1973. Literary critic, academician of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Minister of Culture of Ukraine in 1994-94, winner of the T. Shevchenko Prize in 1991, Hero of Ukraine) and Lukianenko. But I believed that a gangster theory leads to gangster practice. Because if the theory weren't gangster-like, it wouldn't have led to gangster-like practice. Obviously, there is something in that theory that justifies that practice. It's the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” But any dictatorship is violence, and where there is violence, it is no longer democracy. Because democracy is the rule of the people. And they have the rule of the party, the rule of a red gang. Marx put forward the idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat, Lenin supported it, and this gave birth to Stalin, Mussolini, Hitler—all those bandits, red, black, brown, and whatever you want.

I believe that this was the most important step in our entire struggle of the sixties—that we transferred the Banderite cause to our contemporary ground. I am glad that the Lord God gave me such an idea. I had a huge archive of Banderite literature. Besides that chest, we found a whole suitcase of archives, I didn’t mention it. I didn’t even have time to sort through that archive; it was lost. The Banderites, in those conditions, could not go further. Neither Fedun-Poltava, nor anyone else about whom Mr. Rusnachenko writes as the ideologists and theorists of the OUN (Petro Fedun, “P. Poltava,” Feb. 24, 1919 – Dec. 23, 1951. See: Rusnachenko A.M. With Mind and Heart. Ukrainian Socio-Political Thought of the 1940s – 1980s. – Kyiv: Vydavnychyi dim “KM Akademia”, 1999. – pp. 78 – 93; 145-162; 180 – 187 et al.). He gives them a correct assessment. But they could not look into the future, to see that there would be the Sixtiers movement, that there would be dissidence, that cultural movement, to some extent even official. Because Dziuba said that Lenin's national theory was correct, but they didn't follow the Leninist path. I believed that if they had not followed the Leninist path, there would not have been a Bolshevik empire, against which we also stood. So, I raised the “Banderite cause” to the level of the sixties—and in that, I see my merit. But when they started arresting us, everything fell apart.

V.O.: It's interesting, how and where was the journal distributed?

D.K.: The distribution was very intensive. To this day, we don't know the mass of readers it reached back then. The first copy went to the archive (it was preserved by Krasivskyi). I took my share, and Krasivskyi passed the rest to Melen, Melen passed it to Hubka (Ivan Mykolayovych Hubka, born March 24, 1932, at Hubky khutir (Bobroidy village), Zhovkva Raion, Lviv Oblast. Arrested in October 1948, on Aug. 23, 1949, sentenced by the Military Tribunal of the MVS for the Lviv Oblast under Art. 20-54-1 “a”, 54-1, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to 25 years of deprivation of liberty. Released Aug. 21, 1956. Member of the Ukrainian National Front. Arrested March 27, 1967. Sentenced Aug. 1, 1967, by the Lviv Regional Court to 6 years of deprivation of liberty in strict-regime camps and 5 years of exile under Part 1, Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR. Released in 1978. One of the founders of the Union of Political Prisoners of Ukraine), and Hubka distributed it throughout the Lviv region. Hubka knew a lot of people; those people had served time with him. They were reliable people, he knew they wouldn't betray him. So it went around the Lviv region. And I gave it to Ravliuk, and Ravliuk even gave it to children to read—he would take reliable students from the 10th-11th grades to his place, lock them in, and he and his wife would go somewhere to her relatives, and the students would spend the night at his place reading. And after that, the journal went into the hands of Mykhailo Dyak. And Mykhailo Dyak was a police lieutenant, constantly on the move: he had to be on duty in Ivano-Frankivsk, in Dolyna. He knew a lot of people, and he wasn't afraid, because even if someone wanted to inform on him, they would think that maybe he was testing them by giving them such literature. They would think he was trying to catch them to hand them over to the KGB. So Dyak gave the journal to many people to read. In addition, Dyak distributed that entire chest of literature. Dyak distributed it in 23 places! Mykola Fediv distributed a lot. Oh my! I took part in one such distribution myself. We scattered it on the rocks in Bubnyshche, and there happened to be a school group there, tourists from the Rostov region. So they took it and brought “Who Are the Banderites and What Are They Fighting For” to the Rostov region.

Lesiv also distributed it in the Kirovohrad region, in the Haivoron district. He gave it to teachers there to read.

V.O.: And another man was all the way in the Luhansk region?

D.K.: That was Mykola Kachur, who was caught there.

V.O.: Was he the first one to be caught?

D.K.: Well, maybe Lesiv was first—it's unknown, but he was caught and Lesiv was caught. Maybe around the same time, maybe one of them earlier, but by the summer of 1966, the collapse was complete. And Vasyl Kulynyn also gave it to many people to read. One time he left the journals in a haystack, in a bed. The landlady where he was lodging was fluffing the mattress and found them, gave them to her son, and the son, although a party member, did not hand them over to the KGB. They didn't want to give the journals back to Vasyl, so he made a scene, threatened to burn the house down. So they got scared and gave them back. But little by little, all these things were leading us to our downfall.

I emphasize again that, especially through the efforts of Mykhailo Dyak, Mykola Fediv, Yaroslav Lesiv, and Vasyl Kulynyn, the journal reached many people, maybe fewer in the Lviv region, but many here. I was mainly busy with writing; I did little distribution. So I can't say that I myself recruited many people. It was difficult for me, and I had other things to do—how many calluses I got from building the bunker! Because to build a bunker, you had to go there more than one night, and also work during the day. So I had a lot of work to do.

During the investigation, all of this came out... I denied everything for two months, gave no testimony, and when they had exhausted me to the point that my hair turned gray, I duplicated what everyone else had already said. That is, I confirmed what others had already told. And so they sentenced us; the trial began on November 16, 1967.

V.O.: It's interesting how you were arrested, and the others you know about.

D.K.: They caught each of us in their own way. On March 21, 1967, I was summoned to the district education department, where a car with KGB agents was already waiting for me. They arrested me and took me to the prison in Ivano-Frankivsk. They conducted the investigation there until September. I had two investigators—Rudyi and Shchekur (?).

V.O.: Did they use physical methods on you, was there any violence?

D.K.: There was not. The head of the Ukrainian KGB, Nikitchenko, came and met with us. I hadn't given any testimony yet at that point. He said to me: “I am advising you like a father to his child: tell us what you know. Because we already know everything, and you are denying it and only harming yourself. You should confess, and what sentence you get—that's a matter for the court, that's not within our competence.” But I said I knew nothing, and that was that. But later, when I started to give testimony (that was probably in May or early June)—I showed them where the bunker was. There was just a pit there, they had blown up the bunker.

V.O.: So they found the bunker earlier?

D.K.: No, it was Krasivskyi who showed them the bunker. And Dyak showed them the chest where the literature was. I only gave up the typewriter. As soon as I found out that Kachur was arrested, I moved the typewriter from the bunker and hid it under a fallen tree in the forest. And during the investigation, when I realized that everything was already exposed, I thought: what’s the point of that typewriter? If I'm going to be in a criminal camp, it will just rust there anyway, it won't be of any use to anyone. But this way, if I hand it over, maybe it will help me a little, as if I have also conceded something. I led them to where the typewriter was hidden and gave it to them. There was a major-operative there at the time—I don't know his name. I was in handcuffs and covered with a rain poncho. I told the two guards holding me that I needed to urinate. The guards asked the major for the key to unlock the handcuffs and take me. But the major said: “No, no, that's not necessary, I'll take him myself.” That major took me a few meters away behind some bushes (they had built a fire there and were about to have lunch) and said: “Listen, Nikitchenko said that whether you talk or not—no one will lay a finger on you. He said that no one should even touch you with a finger. So they won’t beat you, so you can behave as you wish—it’s your business.” And I said: “Thank you, I don't need anything else.” And that was it. I had even started to give testimony, but then I clammed up again and said it was all a lie, and to all the testimony against me, I also said it was all lies. So I behaved quite freely—I knew they wouldn't beat me.

I believe that Nikitchenko was not a bad person—even though he was a KGB agent, I figured that Nikitchenko was a decent man.

V.O.: That's why he was removed in 1970 for being too liberal, and Fedorchuk was put in his place.

D.K.: I think so too. He was navigating within that system; he couldn't just jump out of it. But, as I see it, there was some humanity in him. I believe that it was only thanks to Nikitchenko that I could afford to behave that way. As for the trial—it's a formality.

V.O.: Were you all tried together, one by one, or in groups?

D.K.: There was a group of us, five, who fell under Article 56. Me, Krasivskyi, Dyak, Lesiv, and Kulynyn. But they let Lesiv and Kulynyn through on the forty-fourth (Art. 44 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, “Imposition of a milder punishment than prescribed by law.” – Ed.), because they were only given 6 years. They didn't actually fall under Article 56, but since they were connected to me, they couldn't be separated into a different case. So the KGB decided that the entire group of five would go before the Supreme Court. We were tried by the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR, while all the rest were tried by regional courts—the ones from Lviv, Kachur, and everyone else.

V.O.: But the trial was still held here, in Frankivsk, as a circuit court session?

D.K.: Yes, a circuit session. There was a judge named Stoliarchuk, and it was that Stoliarchuk who sentenced us. The KGB tried us; the court was just a formality.

The trial lasted from November 16 to 27, almost two weeks. It couldn't have lasted just a day, because there were so many volumes in the case file, they couldn't possibly get through it all. There were very many witnesses, especially for Lesiv. Because Lesiv gave up all of his people, which is why he got 6 years. Lesiv had something like 23 witnesses, because he gave up everyone he had recruited.

V.O.: Good heavens!

D.K.: Oh yes. In particular, he gave up two students, they were about to be expelled, so they held a grudge against him. Nobody knew them, there was no need to give them up... Lesiv behaved very badly. And it’s reflected in the verdict, that during the investigation he helped to uncover the organization, so they only gave him 6 years. In Ukraine, you could get 7 years of imprisonment and 5 of exile for mere chatter—that was the "portion," the norm under Article 62, and here we had Articles 56 and 64—“treason,” “underground organization”—so it's clear he only got 6 years because he gave everyone up.

Then they took us on the transport. We celebrated New Year's at the Lviv transit prison, and Christmas at the Kharkiv one. We sang carols, and they were so surprised there, so fascinated.

V.O.: Were you transported with any of your co-defendants?

D.K.: There were three of us, me, Krasivskyi, and Dyak, because we were headed for Vladimir Prison. The three of us each had 5 years of prison. I then had 10 years of camp and 5 of exile. Because I got 20, and they got 17. So for them it was 5 years of prison, 7 of camp, and 5 of exile. The three of us were transported together. Christmas found us in Kharkiv, so we sang carols, and it even interested the guards. After that, they brought us to Vladimir Prison, and scattered us among the cells. At first, they kept me in cell 20. I met Mykhailo Masiutko there. And after that, they moved me to the first block, where Krasivskyi was. There they put a man named Ronkin, that little Jewish fellow, in with me. So Ronkin and I went on a hunger strike for 5 days. I got to the point where I developed hypertension. They were already keeping us in terrible hunger there, and we went on a hunger strike for 5 days on top of that, even though all the other cells in the prison only fasted for one day, symbolically. But we were told that there would be a hunger strike from December 5th to the 10th, because the 5th is Constitution Day, and the 10th is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. So we fasted for 5 days as a sign of protest that the authorities were not complying with the Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. I undermined my health with that hunger strike.

After that, they took me to Moscow for re-investigation, and I recovered a bit in Moscow. I looked so terrible, I was just a skeleton.

V.O.: What was this re-investigation?

D.K.: Ah, Moscow got involved... It was a matter of this nature. They tortured me most terribly to make me give up the archives—my manuscripts and those Banderite archives. They knew I had them. The journals? They didn't find a single journal on me, I had hidden them all. They wanted to check if I would slip up and if they could uncover something new during the re-investigation. They were terribly troubled by the fact that they didn't know how many journals were still in circulation. They had practically seized nothing during the searches. What did they take? They took two from Lesiv, some from Hubka, from Prokopovych (Hryhoriy Hryhorovych Prokopovych. Born 1928, insurgent, political prisoner 1950-58, from 1974 – member of the Ukrainian National Front. Arrested March 21, 1967, 6 years imprisonment, 5 exile. Lives in the village of Urizh, Drohobych Raion, Lviv Oblast, church elder). But they took nothing from Dyak, or me, or Krasivskyi. So where were the journals? They tormented me so much about them, because it just didn't add up, where the journals were. Dyak actually saved me—I said that I had once given Dyak at least ten, and Dyak was divorcing his wife because she saw he was involved in the underground and didn't want him, understanding where it was all leading. So he said he had burned the ten I gave him. And I also told them that I had burned another ten myself (let's say approximately ten) because they had gotten wet near Kropyvnyk. I had indeed hidden them there and they had indeed gotten wet, but that was nothing. But I said they got so wet they were no longer usable, because I had put them there in the autumn, and then snow fell. They weren't wrapped in anything, just in newspaper. And then I came in the spring, they were already soaked, it had turned to mush, so I took them and burned them right there. That's the story I told, and Dyak confirmed that he had also burned his because he was afraid his wife would turn him in.

But it still bothered them: “Where are the journals? Where are the journals?” And there were—count them: 16 times 6 is 96, and they had practically nothing. So where did the 96 journals go? That's what was eating at them: “There are no journals, you haven't turned anything in.” That’s why Moscow dragged me in for re-investigation, hoping I would mess up something.

V.O.: And when did they take you to Moscow and where were you held?

D.K.: In Lefortovo Prison, for about two months in 1970. They brought me there from Vladimir in a “Volga,” and from there—the guards searched me so thoroughly that, you know, they even broke the soles of my shoes. I gave them nothing, so they were so angry with me they would have eaten me alive. I repeated in Moscow what I had said during the investigation, I didn't make a single mistake. They saw they couldn't get anything out of me and became convinced that time had not affected me. They sent me back to prison. And in 1972, they took me to Mordovia. I ended up in the 17th small zone. I met Ivan Kandyba there (Ivan Kandyba. June 7, 1930 – Dec. 8, 2002, founding member of the Ukrainian Workers' and Peasants' Union, later a founding member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. Imprisonment: 1961 – 1976, 1980 – 1988) and many others.

V.O.: That’s the Ozyorny settlement (in Mordovian, Umor), Zubovo-Polyansky Raion, ZhKh-385/17-A.

D.K.: There's a lot to say about that, it’s in my memoirs. A certain Mykhailo Heifets arrived there. He later wrote a book about Ukrainian political prisoners (Mykhailo Ruvimovych Heifets, b. 1934, Leningrad. Russian-language writer. Arrested 1974, 4 years imprisonment in Mordovia and 2 years exile in Kazakhstan. Author of several books, including “Ukrainian Silhouettes” – about political prisoners V. Stus, V. Chornovil, M. Rudenko, D. Kvetsko, and others. Now lives in Israel). That Heifets was a very cunning Jew. Not just cunning, but smart. He started to play a game with us, and I got drawn into that game too.

V.O.: How so?

D.K.: Like this. He started submitting articles to the wall newspaper. And among political prisoners, that’s not something you do. The head of the section there was a man named Zinenko. He started to pursue a kind of, how should I say, liberal policy with that Zinenko. But he was doing it for his own benefit, and Zinenko later figured out what he was up to. But at first, he pretended to be on their side. Heifets and I were on good terms. And Zorian Popadiuk was also there (Zorian Volodymyrovych Popadiuk, from Sambir, Lviv Oblast, political prisoner 1973-87. Born April 21, 1953. Leader of the “Ukrainian National-Liberation Front,” journal “Postup.” Imprisoned as a student at Lviv University on March 23, 1973, for 7 years and 5 years exile under Art. 62, Part 1, a second time on Sept. 2, 1982, for 10 years imprisonment and 5 years exile. Released Feb. 5, 1987) and Vitaliy Lysenko from somewhere in Poltava. He was some kind of navigator on a ship and had revealed something to foreigners, or something. He leaned towards us, and we tried to keep those eastern Ukrainians close, so they wouldn't become snitches, because they were kind of at a crossroads.

A few of us gathered, and that Heifets started to persuade me not to serve 20 years, because, he said, I would be more useful to the cause on the outside than in here. You, he said, should write, because your case was wrongly classified—they shouldn't have given me Article 56. All I did was write, so it should have been “Anti-Soviet Agitation and Propaganda,” Article 62. He said: “They won't reclassify your article.” Because I had written to the Prosecutor General Rudenko, and to the Chairman of the Supreme Court Smirnov. I could see from their replies that they agreed that the case was wrongly classified under Article 56, but they didn't want to admit it.

Then Heifets told me: “Write for a pardon. If they pardon you, it’s not shameful—you’ll get your work done.” I wrote for a pardon, but there was nothing in the application that would humiliate me. Heifets and I (and Heifets is literate, and I'm no fool) worked it out well. That application lay around for a while, and then after some time, they call me in and say: “You need to write that you repent.” But back at the trial, I had said that I had no intention of fighting against the Soviet government, because the Soviet government had educated me—I was spinning that kind of yarn. And I had a chance to use that “yarn” here. But Heifets said: “That ‘yarn’ won't work, no one will pardon you for that.” Well, so I sat down with Heifets again, we changed a few things and submitted the application again. There was a certain Colonel Drotenko there...

V.O.: Drotenko, the head of the Mordovian KGB.

D.K.: And there was also a KGB agent in the large zone, Stetsenko.

V.O.: Stetsenko—oh, he was a cunning fox! I know him.

D.K.: (Laughs). But they couldn't outsmart us, because Heifets and I were also, you could say, old wolves. We were catching them by the tail. They wanted to use me—I figured them out later. My clemency petition went through: Drotenko took it up and moved the case forward. And after that, he summoned me and said: “We want you to talk to your people in Ukraine.” And they took me to Ukraine. That was in 1975, sometime in June.

They took me to Lviv and held me there. A representative from the Ivano-Frankivsk KGB came once and said: “We are familiar with your clemency petition. You need to write an article for the newspaper stating that you truly repent.” And I said: “I'm not against it—I'll write for the newspaper for you. Writing it is one thing, I don't see anything terrible in that. But first, let me meet with the editor of that newspaper. Because what if I write it, and he twists it so much that I don't even recognize it, and I just disgrace myself? What the hell do I need that for? Let the editor give me a written promise that he will publish it exactly as I write it.” And I already knew what to write.

The KGB agent left, they conferred about something there. He came back again and said: “We can't give you the editor—it's not in our rules, we don't do things that way. If a person truly wants to lay down all their arms, to disarm, then we need the articles, without any editor.” “Well, I can give you an article, but on the condition that you, again, won't change anything.” I wrote it, gave it to him, but it didn't satisfy him. He said it couldn't be like that. Well, I said, if it can't be, then what can you do...

And I wasn't getting any food parcels, my teeth started to get loose—it was terrible! They give you a spoonful of potatoes there. And those who were in the KGB prison got parcels and were basically eating food from home. And I got this little spoonful of potatoes, that little piece of fish, that bread, some of that watery soup! And that's it, you sit in a cell by yourself for months on end. If someone else had been there who got parcels, they would have shared. But to sit like that for months. I started to protest. I said: “Take me away, and if not, I’m going to write a complaint to the prosecutor.”

They put me on a transport, and I got sick on the way. Oh, I returned to Mordovia with great difficulty sometime at the end of July. It's true, Paruyr Ayrikyan (b. 1949, political prisoner, leader of the National United Party of Armenia) supported me a lot there, because he got a package from Armenia—some wonderful sausage, other food. The guys got me back on my feet after that illness, especially Ayrikyan.

They got me back on my feet, and then in August, they took me to the Perm camps. This was in 1975.

V.O.: In August 1975? I was transferred to Zone 17-A from the 19th on October 30, 1975, so the memory of you was still fresh there.

D.K.: [Laughs and says something unintelligible about Petro Petrovych].

V.O.: Petya Lomakin? He was a great revolutionary!

D.K.: [Unintelligible, about snitches]. In my time, I’ve seen a lot of snitches, but such a Quasimodo, such a vile creature, I had never seen before in my life, and I probably will die without seeing another one. I certainly knew what Petro Petrovych was, but I’m telling you, I have never seen such a vile beast.

There was a very fine man there, Bolonkin—have you heard of Bolonkin?

V.O.: Yes, I know Oleksandr Oleksandrovych Bolonkin. He’s a Doctor of Technical Sciences.

D.K.: He was very smart—he taught at the Bauman Institute. That Bolonkin once gave me instructions on how to make printing devices. And Lomakin snitched, so the guards confiscated everything. He was so meddlesome! But in the end, Ayrikyan stabbed him in the backside with a spear, and he bellowed like a bull. I had been holding him back when I was in the zone, but when they took me to Ukraine, they made him a quality inspector (we were sewing work gloves there), and he rejected so many, even those of the snitches, that even the administration was displeased. In the end, that vile little animal turned everyone against himself.

There's a lot to tell, but a group of cunning Jews and Khokhols came together there—Zinenko on one side, Heifets on the other, me on the third, and Lomakin on the fourth. A long war was waged, everyone was in their place in that war, and we knew how to fight it.

Once, Chornovil ended up with us (Viacheslav Maksymovych Chornovil, Dec. 24, 1937 – March 25, 1999. One of the leaders of the Sixtiers. Imprisoned Aug. 3, 1967, under Art. 187-1 for 1.5 years, a second time on Jan. 12, 1972, under Art. 62, Part 1 for 6 years and 5 years exile, a third time in April 1980 for 5 years, released in 1983. Returned to Ukraine in May 1985. Editor of the journal “Ukrainian Herald” (1970-72, 1987-90), member of UHG, People's Deputy of Ukraine of the 1st-4th convocations, leader of the NRU, winner of the T. Shevchenko Prize (1996), Hero of Ukraine, posthumously). Chornovil had this major flaw, that he held himself in very high esteem and could treat those who could have done a lot for him and helped him very lowly, or even ignore them. Such arrogance is harmful, and the events of the subsequent period of state-building confirmed this. His biggest flaw was that he wanted to do everything himself and be on top himself, to be in charge of everything, but without having the appropriate qualifications. I emphasize again—he was a rebel by nature. Similar to the Russian Narodnik Tkachev—maybe you've heard of him, he published “Nabat.” Because he didn't quite reach the level of Nechayev. That Nechayev murdered the student Ivanov. You may not know about Nechayevism, but I was very interested in it. But Chornovil was something like that Tkachev.

I immediately sized up Chornovil as not being very impressive, although he carried himself with a high air and rebelled. I was more impressed by Heifets, so cunning, inconspicuous, who hides himself but bites hard. He impressed me more, and so Heifets and I were friends, along with Zorian Popadiuk. Well, Popadiuk was a bit inexperienced, but we warned him about the snitches. Here is a book, Heifets writes about me in it. Have you held it in your hand?

V.O.: Yes, yes, I know this book well.

D.K.: Well, in there, that Heifets praises me even more than I deserve. (See: Mikhail Heifets. Banderite Sons. // Ukrainian Silhouettes. Suchasnist, 1983.— pp. 213 – 239, in Ukrainian and Russian; also: The Field of Despair and Hope. Almanac. – Kyiv: 1994. – pp. 327-361; M. Heifets. Selected Works. In three volumes. Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. – Kharkiv: Folio, 2000. Vol. 3, pp. 148 – 169).

V.O.: Yes, he holds you in high regard there.

D.K.: Oh yes, he exaggerates there, I wasn't like that. But maybe he wrote some truth—I'm not saying he's lying or anything. No, he writes the truth, but he praises me too much. Well, but when I got 20 years, went through prison, went through 10 concentration camps, went through exile where my legs were broken, and I came out alive, and you see me now... But there were those like Lytvyn (Yuriy Tymonovych Lytvyn, Nov. 26, 1934 – Sept. 5, 1984. Poet, publicist, member of UHG. Imprisoned 1953-55, 1955-65, 1974-78, 1979-84. Reburied in Kyiv at Baikove Cemetery on Nov. 19, 1989), like Tykhy (Oleksa Ivanovych Tykhy, Jan. 27, 1927 – May 5, 1984. First arrested in 1948, on Jan. 15, 1957, imprisoned for 7 years, a third time as a founding member of UHG on Feb. 5, 1977, for 10 years of special regime and 5 years of exile. Served time in Mordovian and Perm camps. Died in captivity. Reburied along with V. Stus and Y. Lytvyn at Baikove Cemetery on Nov. 19, 1989), like Stus (Vasyl Semenovych Stus. Born Jan. 7, 1938 – Sept. 4, 1985. Arrested Jan. 12, 1972, under Art. 62, Part 1, 5 years imprisonment and 3 years exile (Mordovia, Magadan Oblast). A second time on May 14, 1980, died in the punishment cell of the special-regime camp VS-389/36 in Kuchino, Perm Oblast, on the night of Sept. 4, 1985. Member of UHG, poet, T. Shevchenko Prize 1993, posthumously. Reburied at Baikove Cemetery on Nov. 19, 1989), like Svitlychny (Ivan Oleksiyovych Svitlychny, Sept. 20, 1929 – Oct. 25, 1992. Recognized leader of the Sixtiers. Imprisoned Aug. 30, 1965, for 8 months without trial; a second time on Jan. 12, 1972, under Art. 62, Part 1 for 7 years and 5 years exile. Winner of the Shevchenko Prize 1994, posthumously), like Marchenko (Valeriy Veniaminovych Marchenko, member of UHG. Oct. 16, 1947 – Oct. 7, 1984. Journalist, member of UHG. Imprisoned June 25, 1973, for 6 years and 2 years exile, a second time on Oct. 21, 1983, for 10 years of special regime and 5 years exile. Died in a prison hospital in Leningrad. Buried on the Feast of the Intercession in 1984 in the village of Hatne near Kyiv), Sokulsky (Ivan Sokulsky, July 13, 1940 – June 22, 1992. Poet. Imprisoned June 14, 1969, under Art. 62, Part 1 for 4.5 years, a second time as a member of UHG on April 11, 1980, under Art. 62, Part 2 for 5 years prison, 5 years special-regime, and 5 years exile, a third time on April 3, 1985, for 3 years, released Aug. 2, 1988) and others, who had shorter sentences but couldn't get through that hell. Because not everyone could manage it—you had to have a bit of diplomacy, a bit of that peasant philosophy to get through it. I obviously had that, because I had suffered since early childhood, when my mother died and my father was ill, I served in the army, so I had enough life experience. In that element, I could position myself so as not to expose myself to danger.

And when we arrived at the Perm camps, at the 37th zone, I ran into Yevhen Proniuk (Yevhen Vasylyovych Proniuk, philosopher, b. 1936, imprisoned July 6, 1972, for 7 years and 5 years exile under Art. 62, Part 1. Permanent chairman of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons, established June 3, 1989. People's Deputy of Ukraine of the 2nd convocation).

V.O.: He's a co-defendant of mine. And that zone is called VS-389/37, it's the Polovynka settlement.

D.K.: I only ended up in that 37th because I had applied for a pardon... But I want to say that when I returned from Ukraine, Zinenko called me in (you see what scoundrels they are!) and said: “Here, sign this, that your pardon has been denied.” I looked—and it was dated April! And they took me to Ukraine sometime in June. So those scoundrels had received the denial from the Supreme Soviet of the USSR back in April, but they took me to Lviv only to wrench an article out of me and to blacken my name! If I had written the article, it would have done me absolutely no good, because I had already been denied. Because for us, the political prisoners, there could be no pardon whatsoever. But since my article wasn't good enough for them, they put me in the 37th zone. Because in the 37th zone, they had gathered all sorts of, as the Russians say, mraz’ (scum)—those who were about to be released. There was a certain Mudrov there, Doroshenko, and all those who either snitched, or snitched a little (laughs), or had such thoughts. They were already being let go. And me, they put me there too! But not just me—there were very few Ukrainians there. There was Mykytko (Yaromy Mykytko, political prisoner 1973-78, Sambir, b. 1953, imprisoned as a student of the Forestry Institute on March 23, 1973, under Art. 62, Part 1 for 5 years. Served time in Mordovia and Perm Oblast), there was Izia Zalmanson, there were our boys from Chortkiv, five boys who raised a flag. They were taken there only because someone was needed to work, because a metal processing production was opening there. It's unlikely anything good was in store for me there... But they threw Yevhen Proniuk in there, from Kyiv. That Proniuk immediately came to me, suggesting we should pass information abroad. That immediately captured my interest—at least I could show the world what they were holding me for.

D.K.: I started to take part in that struggle. In our conditions, it was a very difficult struggle. We prepared materials about everything that was happening in the zone, made copies of verdicts if they were available. And we passed all of that through Sakharov to “Voice of America” or “Radio Liberty.” It was very difficult work. But I took on that work because I thought they would keep messing with me and I would get nothing from them, I would serve 20 years and accomplish nothing. And since a person is caught, one should at least make oneself heard in the world, so it was more advantageous for me.

We did it in such a way that Kyryn (?) would copy it, and I would hide and store it all. During visits, we would pass that copy along like a relay, and it would get out. But all of this brought on repressions. They started to persecute me because they sensed I was involved. Although I worked, I tried my best, but it didn't help me at all. First, they confiscated all my notes (and I had so many notes!). When they brought me to that zone, they kept asking why I had so many notes. I said they were excerpts from books—I read a book and take notes. But I had diaries there, memoirs.

V.O.: Among those notes?

D.K.: Yes. Heifets did the same. He had such intentions that if he got them abroad, he could use them. And I did the same. And my handwriting is bad, hard to read, so I thought they wouldn't be able to decipher it and would release it, and then I could get it out into the world. But they confiscated everything, and then they started throwing me into the punishment cell. And we declared a hunger strike—the struggle began. There was a postgraduate student from Moscow University there, Dima... what was his last name, he was from Kyiv himself...

V.O.: Mikheyev?

D.K.: Oh, Mikheyev, Mikheyev! So they threw me into the ShIZO together with Mikheyev. And the windows there were broken out, it was terribly cold, I thought we would freeze to death in there. But Mikheyev and I got out, because they put us on such hard labor—digging a trench. The zone had just opened, a bulldozer had pushed aside everything that the common criminals had built, that barrack. There were stones, bricks, reinforced concrete slabs. All of that had to be broken through, dug up, because they wanted to make some kind of road there. Snow had already fallen on that mud, and Mikheyev and I had a very hard time. They kept us in the punishment cell, then they let me out. We again organized various protests, hunger strikes. It's all in my memoirs. In short, I got into such a conflict there that from that holding pen (because people were released from there) they didn't release me, but threw me into the ShIZO along with Vasyl Lisovyi (Vasyl Semenovych Lisovyi, born May 17, 1937, philosopher, imprisoned July 6, 1972, for 7 years and 3 years exile under Art. 62, Part 1, in 1979 – for another 1 year for “parasitism.” Released in July 1983). Oh yes, he didn't want to work. They threw us in for 15 days, I think.

After that ShIZO, they didn't let me back into the zone—they brought me to the guardhouse, and there they showed me my belongings that had been brought from the zone. They put me in a Black Maria and brought me to the 35th zone. That's the Vsekhsvyatskaya station. There I met Ihor Kalynets (Ihor Myronovych Kalynets, born July 9, 1939, imprisoned Aug. 11, 1972, under Part 1, Art. 62 for 6 years and 3 years exile. Poet, winner of the Shevchenko Prize in 1991), Ivan Svitlychny, Yevhen Proniuk... No, Proniuk was taken away earlier. In short, I also ended up in good company there, which was doing the same kind of work. I saw that trouble would be waiting for me here too. I fell ill with pneumonia there because they put me on hard labor. I felt that it would probably be the end of me there. But what could I do, that's how it was—you have to endure. So I endured. I passed on some information, but Svitlychny was in charge of that there, and they treated me with some suspicion, so I was a bit on the sidelines of it all. They did things their own way. Only if I submitted some complaint would I also give them that material.

But I saw that they wouldn't leave me like that. I had a feeling that Vladimir Prison was in my future again. Someone came from Moscow and said they wanted to transfer me to prison because they knew about my materials abroad. I said that I don't pass anything on—I send it to the prosecutor, and as for the prosecutor—who knows who works for whom... I said that it had come to the point where they couldn't even trust their own employees—maybe they were bribed by either the CIA or Mossad. And I started to press him, saying they had no data against me, so their suspicion that I was passing information abroad was insulting. Because they hadn't caught me red-handed—if “Radio Liberty” is broadcasting it, it means nothing to me, because maybe the prosecutor passed it on. I wrote to the prosecutor, and then maybe someone took it from my bedside table when I was at work, or maybe from the special section. In short, I gave him an earful, but he said it wouldn't get me anywhere. But I hadn't been in the PKT there, and if you haven't served time in the PKT, they have no right to send you to prison.

And they decided, since I was doing hard labor there, to leave me, and basically disband the zone. And to some extent, the old Banderites helped them with that. Verkhliak was there (Dmytro Kuzmovych Verkhliak, b. 1928, paramedic. Arrested: 1955. Trial: Feb. 14, 1956. 25 years for participation in the UPA), Pidhorodetsky (Vasyl Pidhorodetsky, born Oct. 19, 1925, insurgent, arrested in February 1953, imprisoned for 25 years of deprivation of liberty, 5 years exile, and 5 years disenfranchisement. Sentenced to another 25 years for organizing strikes. Released March 29, 1981, tried twice more for “violation of passport regime.” Spent a total of 32 years in captivity), Molozhensky, and Symchych (Myroslav Symchych, born Jan. 5, 1923, commander of the Berezivska company of the UPA. Imprisoned Dec. 4, 1948, for 25 years, sentenced to another 25 for participating in a strike. Released Dec. 7, 1963. Imprisoned without trial on Jan. 28, 1968, for another 15 years, and at the end of the term – for 2.5 years. A total of 32 years, 6 months, and 3 days in captivity. Lives in Kolomyia, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. An active public figure. Book by Mykh. Andrusiak “Brothers of the Thunder,” interview by V. Ovsienko in “Suchasnist” No. 2 and 3, 2002). They basically brought the zone to its knees with their own hands. Those old guys started looking for trouble where there was none, which was exactly what the KGB needed. In short, they pacified the zone, the zone became dead.

V.O.: How so?

D.K.: Because information wasn't getting out. And if information wasn't getting out—that's it, the zone effectively doesn't exist in the eyes of “Radio Liberty” or “Voice of America.” Because the zone stopped providing anything. I reconciled myself to that, and they still took me to Ukraine, even though I didn't want to go.

And it happened like this. A certain Honchar came from Ukraine.

V.O.: Yes, there was a KGB colonel named Honchar, he worked in Kyiv, looked after the Ukrainians.