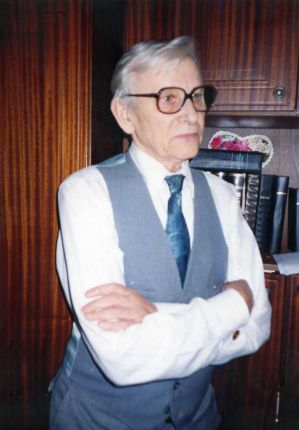

Recorded on January 20, 2000, by Vasyl Ovsienko in his home, in the presence of his wife, Nadiya.

Their corrections from June 1, 2002, have been included.

V. Kurylo: I was born in the Carpathian region, in the village of Tserkivna, now in the Bolekhiv district of Ivano-Frankivsk oblast, on April 2, 1921.

My beloved Carpathians, this beautiful landscape which I can never forget! It is before my eyes day and night; I see them in my dreams… When I was in prison, I always saw them in my dreams. It gladdens me that I so love our Carpathians, where I walked with bare feet, where I grazed cattle, where I gathered berries and mushrooms, where I delighted in the rustle of the forests, where I heard the roar of the gurgling water that rushed over the rocks like a waterfall! All of this gladdens me to this day! It is a delight that should fill the heart of every Ukrainian who loves their land, their Ukraine! This is what I want to say first of all. And whoever hears or reads these words, let them understand what kind of love one should have for everything that is native and dear!

I was born in the early spring on April 2, in a field where my father and mother had gone out to sow oats. Father was sowing oats, and my mother was sitting on the balk. She was in labor, but she waited patiently for the moment she would part with her child. It was very difficult. She was pushing out this tiny little crumb who was to bring her joy. And not just to my mother, not just to our family, but to all of Ukraine, because I work for Ukraine. I am placing my own small brick into this great edifice. And when I was born, the rays of the bright sun warmed my little body, illuminating the place where I was born.

A lark rose up high and then plummeted down like a stone. It seemed that it would shatter itself, but it rose again and sang cheerfully above us. This has been an inspiration for me since I was a tiny child. For I love to sing very much, I loved to dance. I love everything connected with my Carpathians, with my mountains—beautiful, green, and rich! When those spruces dance like ballerinas—the way their tops sway in the wind, what a beautiful performance they give! I see it, I understand it! And when you climb Mount Rusnachka and from those rocks you see the distance—that is what fills my heart!

When I was born, my father put my mother and me on a wagon and took us home. He was a very hard-hearted man. He didn’t understand pain, didn’t understand suffering, because he knew only one thing: work, work, work. After bringing us home, he said: “Feed him something quickly and come back out; the horses need to be led, we have to harrow.”

And so my first breath and my first cry were a response to my father’s cruelty. That is how my life began.

Life in Tserkivna was not easy because the land there is rocky and bad, not fertile, and it yielded little. But we had the richest forest! Nuts, apples, sweet and sour cherries—everything was in the forest! There were mushrooms, berries, raspberries, blueberries—whatever you wanted! Anyone who wanted to work could get everything from the forest.

There were eight of us children, and we all worked. But death rages where there is poverty. It took two of my little sisters and one brother from me. Four brothers and a sister were left. It was hard for us. But my mother worked and always thought about how to give us an education, how to teach us so we would be worthy people. I remember as if it were today, my mother always dreamed that I would become a priest. How she wanted that! She sent me to the gymnasium. I studied there until the “Polish canaries” destroyed the gymnasium and beat its director to death. That was the end of my gymnasium education.

V. Ovsienko: In what year did you finish?

V. Kurylo: 1939. I finished it with great hardship.

THE UNDERGROUND

Upon reaching my youth, I plunged into the vortex of the struggle for Ukraine's freedom. Along with other young boys like Shturmak, Hrytsylo, Huk, and my paternal uncle’s children. We all yearned to do something for Ukraine. I remember, when I went into the underground, my mother asked me, “When will you return home?” And I said, “Mommy, I don't know when that will be. But it won't be soon.” She went and packed some clothes for me, that is, a shirt, a towel, some linen, and said, “Here, my son, go! But do not bring shame upon our family, our kin, and our people! Remember, these are your mother’s words.” This is how my mother sent me off into the underground. She loved her son—and her son loved both Mother Ukraine and his own dear mother, who gave birth to me there, in the field, under the bright rays of the sun, on that balk. I thank God for helping me to understand all this. I live by this to this day.

I have lived through a great deal. When I was a young man, I was chosen as a youth mentor. I educated them in a national spirit. This is the ideology of Ukrainian nationalism. There were the forty-four rules, the twelve traits of character, there was Moshchak's prayer, Olzhych's prayer. I knew it all by heart—and I remember it to this day. It will soon be eighty years—and it all still weaves through my mind, because I love it, because it is mine, it is of my heart. I think about it and rejoice in it.

So when I was seventeen, I had to go into the underground. It was just when *“Polshcha vpala – i nas rozdavyla”* [“Poland fell—and crushed us”]. We then found ourselves under Bolshevism, under communist imperialism, which had replaced Poland. From the very first days, they began to deport people, arrest them, and throw them in prison. In Tserkivna, Uzhela Parania, Uzhela Mykola, and Ptakh with his family—he was a forester—were all imprisoned. It was immediately clear what socialism and communism smelled like. We recognized it at once. But not everyone did. So we began to band together, to take counsel. We had good teachers: Shturmak Hrynio, my uncle Kurylo Hrynio, Kurylo Ivan, Honchariv, Hrytsylo Hrynio. They educated us very well. Hrytsylo was older. They tried to make us understand the depth of the wisdom of the ideas of Ukrainian nationalism.

When the Bolsheviks retreated, another plague took their place—the brown one. The German fascists. They too immediately began to show their horns, to show what they could do. They started to track people down and execute them. We, the young men who were marked for anything, were forced to go into the underground.

I too went into the underground. In the summer of 1942, I found myself in the village of Mizun. The leadership sent me there. There I made contact with our leaders and there I swore an oath of allegiance to Ukraine, to my people, to the OUN-UPA. I went to work in the editorial office. In that place from which the words of call and fervor came forth, from which the voice came: “Boritesia – poborete! Vam Boh pomahaie!” [“Fight—and you shall overcome! God helps you!”]

I worked alongside the wife of the regional leader, Olya, and with the poet Oleh. He was from the Carpathians, just like me, “Orest” (that was my pseudonym). In time, a certain Myron joined us. I don't know his last name; he used the pseudonym “Myron.” He was like a Gestapo agent: he was fluent in German, had an SS uniform in which he had fled from them and come to work for the OUN. He was an excellent musician, he even taught me to play the violin. Another one, Andriyko, joined us. A very cheerful, good fellow. He was a humorist—and a very idealistic man. He never had a thought of shirking anything to save his own life, to survive. No! Our call was: *“Zdobudesh Ukrayins'ku Derzhavu, abo zahynesh u borot'bi za neyi! Ne dozvolysh nikomu spliamyty ni slavy, ni chesty ukrayins'koyi natsiyi! Bud' hordyi z toho, shcho ty ye spadkoyemtsem u borot'bi za slavu Volodymyrovoho tryzuba!”* [“You will either gain a Ukrainian State, or you will perish in the struggle for it! You will not allow anyone to defile either the glory or the honor of the Ukrainian nation! Be proud that you are an heir in the struggle for the glory of Volodymyr’s Trident!”] These are words from the Decalogue. We repeated all these words every morning when we lined up for exercise. Some recited Moshchak's prayer, others the Decalogue, we prayed to the Lord God to bless us and our struggle for the freedom of Ukraine. We did not fight with swords, we did not fight with arrows—we fought with a double-edged sword: the word of truth.

And so the days passed. We lived in Mizun, in a forester's lodge. A very beautiful place—near the forest, between the mountains. It seemed very beautiful, and the place looked almost safe for us. But one day our peace was disturbed by an evil spirit. A beggar with an outstretched hand came in through another door. But this hand was soft, and his face was pampered. He didn't ask for bread, he said: “Give what you can!” And he looked around to see how many of us there were. He was counting our people, how many typewriters we had, what we were doing. When we told him we had nothing to give him, he closed the door and left. We already understood that this person was sent to us. Myron, in particular, figured it out instantly: he quickly put on his uniform.

V. Ovsienko: The Gestapo uniform?

V. Kurylo: Yes, the Gestapo one, and he ran to intercept him. He had all his documents with him. He ran cross-country to meet this beggar on the road. He was running, out of breath, and he jumped, he said later, over a fence, thinking he had torn everything on himself. But he jumped over safely. And he met the man on the road, right at the turn. He yells: “Heil Hitler!” The other responds: “Heil!” Myron asks: “Wohin gehen Sie? Where are you going? Who are you?” The man: “And who are you?” Myron pulls out his documents and says: “I’m a Gestapo agent!” He says: “And I am a Volksdeutscher.” And so they understood each other. Myron immediately asks: “And what are you looking for here?” “Well, it's like this, the command gave me a task to find where the nest of bandits is located here. They need to be uncovered, destroyed, so that there's not a single bandit’s paw here.” “So that’s it! That’s wonderful, we’ll do it together! Are you hungry? Come on, we’ll feed you.” And he led him to the district leader with the pseudonym “Rostyslav” (the same Ivan Khomyna), who lived in this village. Ivan’s mother almost died of fright when she saw a Gestapo agent in her yard. But Myron winked at her to calm down and ordered: “Find half a liter of vodka, make some fried eggs, because we’re very hungry, we worked all night!” And she knew where I worked. My mother knew… He says that his mother quickly prepared it.

Right away Ivan appeared: “Hello, hello!” Seeing the uniform, he quickly grasped the situation, being a very intelligent man, and shouted: “Halt!” We, Myron says, jumped to our feet, saluted, and Ivan asked who, what, where, how. He spoke German well. At that time, almost all students were literate, intelligent. Not like now—they don't even know two words in their own native language. So he questioned him and said: “Well, alright! Let’s have a drink!” He poured, they clinked glasses, they drank. But Myron didn’t drink; he immediately rushed off to the village of Pshenysnyk. There, about a kilometer and a half away, was a village where the Security Service was quartered. He reported on the matter. They quickly ran through the forest, jumped across the river—and to the house. The “beggar” hadn’t even had time to wipe his beard when the SB was already there. They say: “Well, and now you’ll come with us. You can have another drink at our place. Let’s go!” And Myron says: “Well, alright, I have one more thing to do here, I’ll catch up with you.” He returned to his workplace, to our forester’s lodge, and laughs and rejoices. “What happened?” “Well, this and that happened!”

That was our work, the struggle against the enemy! It was very hard work—risky at every moment. They took that “beggar” to Pshenysnyk. I don’t know what happened to him. Well, it's clear what happened.

And we were forced to immediately get out of that forester's lodge, although we were very sorry to leave. We moved to the village of Novoselytsia. It's a place between rivers. A very beautiful village: between rivers, with a mountain, an almost golden mountain, all green. When we went up this mountain at night—just to rejoice, to breathe the air—we couldn't marvel enough at this beauty. When you see lights in the little houses all over the valley, and here, on the mountain, the moon shines, illuminating the mountain—it was beautiful! And we still lacked freedom... And so we began to work at the new place.

There were eight of us now. Everyone had a job. I worked on a cyclostyle, then I moved on to typing on a typewriter. There were girls there who also typed. And other guys worked on the cyclostyles. A certain “Sviatoslav” from the same Pshenysnyk would bring us materials; he was our quartermaster. He provided us with paper, stencils, correction fluid—everything needed for printing. Rollers, new cyclostyles—he got everything somewhere. And where from—that didn't interest us. We worked. Day and night, day and night we worked, because it was necessary.

It was necessary to send materials to the eastern regions of Ukraine, to the forest for the insurgents, to distribute them in villages to the people, so they would know that they needed to be conspiratorial and how to be conspiratorial to save themselves and their families. All this was the struggle. Everyone was involved in it.

And what about today? When I was arrested for the second time, my wife was walking down the street. People would avoid her, cross to the other side of the street to not meet her. Because her husband is an enemy of the Soviet government, sitting in prison! And she, poor thing, drenched in tears, would go home, perhaps hungry and exhausted. That’s how people fought and, to our great regret, continue to fight to this day... But it’s alright—among this nation there are wonderful people who completely devote themselves to the struggle for Ukraine’s freedom. They lay their small brick in this great edifice. Thank God, we too have lived to see this.

A great struggle against the Germans unfolded. There was a terrible battle near Brody. The Germans suffered a defeat there. Kovpak, Medvedev, and other beasts and villains were advancing on the Ukrainian insurgents. Then people understood that they needed to rally even more around the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. The people helped the UPA with everything. Although the Bolsheviks screamed themselves hoarse that the people hated it and didn't help, the opposite was true! The people helped with bread, with salt, with whatever they could, just to strengthen the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, to save these heroes. If a wounded person came to someone, they were cared for like a small child. When I was wounded, they also took care of me. Sister Avhustyna, the late Dr. Malynovsky, and others, so that I would recover quickly.

But the enemy was not sleeping. The enemy was watching my every step. And they finally tracked me down. When I was transferred from the hospital to Mayzli, I didn't stay there long: I was arrested right there. A certain Furchuk arrested me...

When we were working in Novoselytsia, there was an announcement that artists in Stanyslaviv would be staging some drama. At that time Oleh—although we begged him not to go, because it was dangerous, because it was forbidden—didn't listen to us and went. And he went forever, because it was a provocation: instead of a play, machine guns were already set up on the stage, and the Gestapo was all around. The muzzles of submachine guns were aimed from all the windows, all the people were under sight, including our dear friend Oleh. The Gestapo sorted everyone: some to the left, some to the right. Oleh fell into the group that was to be shot… When we learned about this tragedy, we were terribly grieved, but we couldn't help him in any way. He was shot on the third day. He behaved with dignity. He said: “You are trampling on our bones, but the time will come when we will trample on your bones!” He died with these words. There, under the Jewish synagogue in Stanyslaviv, seventy-six people died with him.

It was a terrible tragedy! Many underground fighters died there, many people who were not careful about their situation. After this, instructors and leaders came from the Carpathian region. They inspected everything, how things were with us, and said that from now on I was responsible for the technical department of propaganda. They made me the head of the technical department. Well, what could I do—an order is an order, it must be carried out. It was a group of printers and the soldiers who protected us.

But soon we were transferred to the village of Tiaziv. There, another provocateur appeared. He introduced himself as a flyer (a pilot), supposedly sent by the Carpathian region to train pilots. But he came with a completely different purpose. The district leader, Chornyi, exposed him. He immediately realized that something was wrong here. In the evening, they sent us to the village of Silets, and they themselves waited to see what would happen next. When they heard the rumble of trucks, motorcycles—instantly (it was summer) they crawled on their bellies into the garden, into the fields. They dragged whatever they could with them. And they escaped from that place. When the Germans raided the place, there was nothing left there. What happened to that flyer—I don't know. The Germans set fire to the houses, the barns. But there were no deaths, thank God. Only after this were many people from Silets taken away to slavery in Germany. And we were transferred from Silets to the Bohorodchany district, to the village of Chornolistsi. In Chornolistsi, we welcomed the year 1943 and wintered there until the arrival of the Bolsheviks. We set up camp and began to work. The conditions were difficult, but we paid no attention to the hardships, to the hunger. We printed literature—all sorts of brochures, leaflets, proclamations. We all worked day and night to make up for lost time.

Chornolistsi is a very beautiful village! And the hosts treated us very well. We had our own combat unit, which protected us. But by the early spring of 1944, Russian planes were flying and searching for us. They were searching for the Germans too. The Germans fought back. There were air battles. We carefully camouflaged everything then. The work stopped. An order came from the Carpathian region: we were to move in small groups to the Chornyi Lis [Black Forest]. This was the time when the Bolsheviks had crossed the Dnipro and were pressing the Germans. The Germans were hastily fleeing to the Carpathians.

When we were leaving Chornolistsi, the Germans had blocked us, but we somehow managed it successfully, not a single person was lost, we camouflaged ourselves as best we could. And the girls, and the boy-fighters—all of us, the workers, camouflaged ourselves so as not to lose a single unit. Thank God, we succeeded. We never lost our strength of spirit. We constantly did physical exercises before sunrise, washed with cold water, with snow, to harden our health. The food situation varied: sometimes we were hungry, when the quartermasters didn't deliver food, and sometimes we were full.

So, in small groups, we began to move to the Carpathians. I had to disguise myself as a little boy because I was generally thin, small, and my voice was squeaky. I rolled up my trousers, put a tattered hat on my head. The courier who was escorting me took a basket, stuffed what was needed in a corner, and off we went. We are going to the village of Zvyniach. We had to go through Zvyniach, through Yamnytsia and—to the Chornyi Lis. As we walked through the fields, some Magyars in their feathers (the field gendarmerie) jumped out in front of us: “Halt! Halt! Document?” And how the Lord God helped! I subconsciously stuck my hand into my top pocket, pulled out some piece of paper (how did I even have it?) and said: “Bitte, Herr!” And he: “Gib mir!” And I say: “Nein! Dokument! I am not allowed to give the document into your hands!” Why was I not allowed? If he wanted to, he could have taken it... I showed it to him. “Abfahren!” Do you understand?

V. Ovsienko: What does that mean—“Abfahren”?

V. Kurylo: Go away! Abfahren! And so we go. The girl turned pale, she can barely walk, she’s probably all wet... What do you think—a weapon, and something else in there! We passed by them, they were looking at us like that. And I'm just whistling! Oh, how I whistled! We passed them... I want to see if they are following us. I drop a handkerchief from my pocket onto the ground and pick it up. As I pick it up, I see that they are still standing where they were. Praise be to you, Lord! I tucked the handkerchief in my pocket, and we went on, step by step, step by step... No one else stopped us anywhere. The Magyars were everywhere there.

We arrive in the village of Yablinka. The stanychnyi [local OUN leader] and some other people who took care of us had already been informed and met us. But only the two of us arrived. And the rest? We didn’t know. But they whisper to us: “Your people are already here.” We stopped in this Yablinka.

And what’s happening in that Yablinka? The Bolsheviks are already at the doorstep, bullets are flying over the village, artillery is thundering—a terrible business! The front is three kilometers away! A leader named Poliovyi appeared before us. He had been sent to us in the technical propaganda department by the Carpathian regional leadership. He shows his documents, a note from Robert. Everything seemed to be true. But he starts asking questions: and where are you from, and where is he from, and where is that one from… I say: “I don’t know anything. We have conspiracy rules, and you know that no one is interested in anyone else. I am simply surprised that you still don’t know this!” And he says: “Well, I’m curious, I need to know my people, with whom I will be working.” We talked like this until evening. In the evening he disappeared somewhere. Half an hour or maybe an hour later he comes back with a guy like this, with a huge face. He comes and says: “I’m leaving for abroad. You are to take over the unit, you take over the people, you are responsible for it all.” This man, or maybe someone else, will come to you with this pseudonym: “Prophet Muhammed, Varna, Zdorovyk, Kvas, Tymchenko. You will answer him: ‘22-222’. And you can talk to that man. Whatever he tells you, you must do.” Now there was no mention of him going abroad. There were some strangers here. This surprised me. How could this be? But our entire unit was in hiding. People were sitting in some barns waiting for God's mercy: what would happen next? As soon as they left, I immediately call the stanychnyi and say… I immediately sensed a provocation because I was already an old hand, I knew what this could smell like. I say: “Immediately find wagons, load all the equipment, so that not a single piece of paper is left anywhere! Take everything so there are no traces! Demolish the bunkers! And let’s get out of here. During the day, so that by 11 or 12 o’clock there won't be a trace of us here!” And so it happened.

We left Yablinka at night. Where to go? To Hrabivka? We go through Uhryniv, through the village where Stepan Bandera was born. It's near Kalush. And we immediately went to Hrabivka. We arrived in Hrabivka—and I was glad that there were already acquaintances there. I went to look for a contact. The wagons drove into the forest, the guys set up posts, and I went to look for a contact.

And what? How the Lord helped! I enter one house, I look—there’s a flickering light. I knocked—there was some movement, and finally, a man opens the door. It turns out, he’s a priest’s son. He’s also a priest, studying to be a priest. We immediately recognized each other. He asks: “What happened, what is it?” I say: “Who is here?” He says: “Vira is here.”

This Vira is from my region, from the village of Vytvytsia in Bolekhiv district. She’s an old underground fighter. She was waiting in this Hrabivka until she would be taken to the forest, to Hamaliya. She says: “I’ll try to contact Hamaliya right now.” She had a word with this guy, what was his name, Yar. Yar left. He returns with some insurgent boys and says: “Unload the wagons immediately. Send the men away, they must try at all costs to get out of the forest before sunrise. Load up some hay: if the Bolsheviks catch them, let them say that they are the ones who were in Germany…”

V. Ovsienko: Ostarbeiter?

V. Kurylo: Exactly. And so it happened. They were older people, they knew how to present themselves. So they left. And we, the boys, took everything there was on our shoulders: the typewriters, everything, everything—and we went. There I met Hamaliya for the first time, I greeted him. “Well, how did you, you poor orphan, get here?” I told him the story, he laughed and said: “Oh, what a pity I didn't know—I would have cut them off.” He was such a warrior—merciless to the Bolsheviks.

And so we found ourselves in the Chornyi Lis. There I also met Rizun and Khmara. They were kurin commanders. And Rizun was already the leader of a detachment. People from Tiaziv came there, we united into a single group. But a plane landed somewhere on a mountain meadow, some officers arrived (I don’t know them), they conferred about something. Finally, all the groups began to disperse: some went east, others—west, who knows where.

We stayed with Hamaliya. He says this: “Now we will be your guards, and you will be our assistants.” And so it was.

ARREST

Just before the Christmas holidays of 1946, I was gravely ill. All of this had exhausted me so much that I had tuberculosis of the lungs. There was a paramedic named Kalyna there; she wrote me a referral. They decided to take me semi-legally for a consultation at the hospital in Stanyslaviv. I was very afraid of this. But what can you do? Sickness does not ask. She takes me by train from Bodnariv to the hospital for a consultation. And what happens? Several cars of Bolshevik chubaryks were on that train. Between the villages of Pavelche and Yamnytsia, our boys attack—shooting began. The boys hit the Bolsheviks so deftly that they scattered. Then they slowly retreated, fighting. With a fight, but they retreated. There was a small wood there, and they headed for this wood. Somehow I jumped out of the train car. I should have stayed in the car, but I jumped out… You know, it’s just one of those things, it affects your psyche. And then I was wounded by a stray bullet in my left leg, in the calf. The bone, fortunately, was not hit. And I hit my head on some object. And I broke my arm. My escort bandaged my arm, pushed me back into the car. The train didn’t stop for long, maybe forty minutes. It started towards Stanyslaviv. She took me not for a consultation, but straight to the hospital, at 114 Dzerzhynsky Street. That was the regional hospital. She brought me there and presented me as a poor boy from the village of Bodnariv, who had had an accident—a broken arm, and a head injury. She started to cry, and they admitted me.

They admitted me at the clinic—and immediately to the operating room. There was a Dr. Khlyupin. I remember, thank God, all their names. He looked and said: “To Dr. Bilonosova—have her take an X-ray of the head and arm.” They did it quickly (it was all in the evening)—and he immediately began to operate. Dr. Khlyupin operated on me, but next to me stood Sister Avhustyna, a nun who was from Bodnariv. She understood everything. She was a very intelligent, older woman. She understood everything, and she just caressed me like this: “Everything will be fine!” I didn't remember anything, but she kept whispering: “Everything will be fine!” And so they operated on me, put on a cast, bandaged my head, did a puncture. This was, in general, risky to do, but I was young, thank God, and I survived it well.

I spent the night. In the morning, they took me to some semi-basement. A tall, handsome man in a white coat and cap comes in: “Good day, hero!”—he says to me and offers me his hand. I was surprised: who and what? “I am the director of the hospital, Dr. Malynovsky. Don’t be afraid,”—and he squeezes my hand like this. “Don’t be afraid.” He examined me and said: “I will look after you. This sister will supervise you. Whatever you need, turn to her, and she will know what to do.” And so it was.

How long did I stay there? I think three weeks. My head got a bit stronger, my arm started to mend. But they held it like this—I was arrested with my arm like this. The wound healed quickly—youth, everything fell into place.

But one day, in the evening—some commotion. “What’s happening, what’s happening?” “They are looking for some underground fighter here. They're looking for an insurgent.” The head nurse, such a beautiful woman, comes running, and the same nun comes and they say: “Get your things quickly! We’re moving you from here. They’re looking for you,” she says. “They’re looking for you. We’ll send you away now.” They immediately took me to another door, through the gardens, a wagon was already waiting there. They put me on the wagon—and drove me away. They took me to Mayzli, outside the city. A suburb. And there, from who knows where, students appeared around me, from the medical institute. I remember it as if it were today: Volosiavko, a priest's son, and Moroz.. And these guys, around me this and that, and what’s this, what’s that? I didn't tell them anything. But they saw that I wasn't just a village boy. They hovered around me like that. Finally, I noticed a green cap walking under the windows.

When I noticed that, I already knew it was over—there was nowhere for me to go. I already saw that I was surrounded. This was… I’ll tell you in a moment—November 6, because on November 7 I was already arrested. This was in 1946. And in comes Furchuk—the executioner of the Ukrainian people, himself a Ukrainian from Volhynia, a Volhynian. He bursts in with his enforcers—and says to me: “Hands up!” And they search: “Where’s the weapon? What's your pseudonym? Where’s your leadership? Talk!” And they practically carried me out on their fists, shoved me into a “black raven” and drove me to the KGB in Frankivsk.

V. Ovsienko: It was Stanyslaviv then? And the NKVD?

V. Kurylo: Yes, I call it Stanyslaviv—that’s what they called it then.

They brought me there, and that very same Furchuk immediately began to conduct the investigation. He was a major. He constantly questioned me: “Where? Who? What? To where? And to whom? Who sent you? Who did you communicate with? Who are those people?” And so on. I play the part of someone who has lost his memory. And my good fortune was that it was written there that I had a small percentage of my memory left. That saved me. I acted as if I didn't understand, I didn't know, I couldn't remember. “How did you end up in the Chornyi Lis, what battles were there?” “I don’t know. I didn’t see any battles.” “How did you get there?” “I don’t know how I got there. I know that they were taking me to Germany. I know that they were taking me to Germany, some people broke up the train echelon, and I ended up here.” I twisted and turned like that, whatever came to mind, I lied. In three months, they compiled a file this thick on me. During my second arrest—Nadyusia here saw it—there was a mountain of volumes, eight volumes of all sorts of stupid nonsense they had collected…

He tormented me like that for two weeks. They were banking heavily on me. But fortunately, there were no weapons on me, only medical books. That’s what saved me. No matter how much they interrogated me, nothing came of it. They beat me, doused me with water. Everything on me was swollen. My head ached… In truth, my head ached terribly. One day the door opens, and in comes a tall, handsome officer, with a captain’s insignia: “Hello, Orest!” Imagine this moment: “Hello, Orest!” “What kind of Orest am I to you? Who are you?” I didn’t recognize him right away. “What’s with you? Have you forgotten your leader, Poliovyi? I am Poliovyi. I handed over the whole unit to you, the people. Where is the unit?” “What unit? I don’t remember anything, I don’t know anything.” “Did they beat you?” “No one beat me.” But I was all covered in blood. He did, however, press a button, a nurse and a doctor ran in at once. They immediately washed me, bandaged everything, cleaned me up. “How many days haven't you eaten?” “I don't know.” I know nothing—and that’s that. He did order me to be given Moro's solution. V. Ovsienko: What is that?

V. Kurylo: What they fed Mart Niklus in Kuchino… Those people who had been on hunger strike for many days: it's carrot juice, some other components—they give you such a liquid to drink. They gave me half a liter to drink. Not through the nose, I'm glad to say. I drank it, because I was terribly thirsty and terribly hungry. After that, they told them to give me a thin soup, so my intestines wouldn’t get twisted. The doctor ordered it. And so they did. They carried me on a stretcher to the basement, to a cell where they would hold me and conduct the investigation. And who did I see there? As soon as they threw me over the threshold and inside—a certain Stefan Savchuk from Yamnytsia runs up, like a fox. He was the head of the regional consumer cooperative. They immediately made a bed for me. I was wet, all my clothes were wet. I couldn’t move, so they undressed me. Next to me, on one side Savchuk, on the other—a priest, the vice-rector of the Stanyslaviv diocese. And he recognized me. He just gave a signal like this—I already understood, it was clear to me: “Don't talk!” Savchuk began to question me: “And where from? And who? And what? And how? And where? Were you in the army? Did you fight?” And so on. I say: “Don't talk to me, my head hurts very much. I am beaten. My head hurts terribly. I can't listen to you speak.” “No, no, no. I won't. I won't.”

Who else was there? Dikonov—a spy, a major spy, who got caught and for some reason ended up in our Stanyslaviv prison. There was a Pole, Adam Bialkowski—a zek, he was a former colonel or lieutenant colonel. And after that Chepyha—a teacher, Savchuk—the priest. And someone else was there. I don't remember exactly. And this Savchuk wanted to take me under his wing at any cost. But Dikonov, a very decent person, came, wiped me down: “It hurts here, you have a bump here, and here.” He felt everything. I pretended not to understand and played the fool—there was no other way out.

Oh, and I forgot something. When that Captain Poliovyi was leaving, he said to me: “Either say you know everything, or you know nothing.” He closed the door and left. Those were his last words to me. I never saw him again. “Either you know everything, or you know nothing...” What did he mean by that? “Hold on, boy, or you’ll perish!” Right? Yes!

I stayed there for another three or four days. They summon me (I was already back on my feet) to the basement. A deep basement, a huge dark room. There is light, admittedly, but no windows. A huge chopping block, with an axe driven into it. A carpenter's axe, with the handle sticking up. Do you understand? The block is covered with paint. It wasn't blood. But when you look at it, it looks exactly like blood. Two “parrots” are standing there: one on one side, the other on the other. Holding submachine guns like this. No one says anything. And there’s the one who runs all this. He’s some kind of senior NCO, or who—I don’t know. I don't remember because it was truly a psychological pressure. And: “Раздевайся! [Undress!]” I undress, there’s nothing else to do. “Догола? [Naked?]” “Да, догола! Тобі не потрібна вже та одежа! [Yes, naked! You won't need those clothes anymore!]” Aha, so it’s clear, they chop heads off here. So I undressed, threw all that junk, those boots, everything I had, to the side and stood there. “Підходь! [Approach!]” I approach the block, thinking, now he’s going to say: “Bend your head!” “Стій на місці! [Stay put!]” He went, took my boots, took some knife, and started picking at the sole. Prying up the sole, to see if anything was hidden in the boot. Can you imagine?! You had to live through that moment! What makes people go gray? Why do people have heart attacks? He checked everything. Then I understood that it was just a “bluff.” Then he said: “Одевайтесь! [Get dressed!]” I got dressed, then they shaved my head and—straight into a cell. A completely different cell, an investigative one.

They summon me for interrogation. He introduced himself as Major Buryakov. Major Buryakov: “Так что, будем разговаривать или будем в прятки играться? [So, are we going to talk, or are we going to play hide-and-seek?]” I say: “You haven't even asked me anything yet, and you’re already saying we're playing hide-and-seek.” He walked over and whacked me here. I went down like a sack, and there I was, lying on the floor. Two “parrots” ran up, sat me on a stool. I'm sitting again, sitting fine, as if nothing had happened. “Будеш говорити? [Will you talk?]” “Whatever you ask, I’ll answer you. Whatever you ask.” “Где ты был, в каких боях? [Where were you, in what battles?]” “In none!” “Кто тебя завербовал? [Who recruited you?]” “No one recruited me!” “Как ты оказался в банде? [How did you end up in the gang?]” “I don’t know, my head hurts, I’m beaten. My head, my head hurts terribly, I don't remember anything. I don’t remember what day it is today!” “Врешь! Врешь! [Liar! Liar!]”—and so on and so forth… You know, curse after curse! It affects me because I was not raised that way. I listened patiently, listened and kept silent.

He came up again, gave me a blow here, in the liver. The liver, truthfully, hurt a lot. I yelped but held back. And he (they summoned me at half-past eleven at night... Until six in the morning! That was the rule—to summon at night and interrogate, so no one would hear)—and when he had been tormenting me, tormenting me, and hadn't written a single word, he pressed a button—the “parrots” came and took me away. And as I was being led down the corridor, what did I hear? A woman was screaming, poor thing: “Дайте лікаря! Дайте допомогу! [Get a doctor! Help!]” “Когда все скажешь, дадим тебе доктора, будет все хорошо! Не скажешь – подохнешь! [When you tell us everything, we’ll get you a doctor, everything will be fine! If you don’t—you’ll croak!]” I heard all this with my own ears, all this is being recorded in my memoirs... I heard a few more words as she cried and begged for help. They gave her no help. She cried for a whole day more, and then toward evening, she fell silent. She fell silent forever—and her baby, and her. They weren’t separated! That’s how she was sent to the dungeons. That was such a terrible episode!

And when they finally began the investigation on me, this same Major Buryakov—what didn’t he do! How he didn’t mock me! And finally—a stool like this. He beat me with that stool. The stool broke, flew apart. Well, you have to understand, I was still a strong fellow, a stubborn Boiko. He hit me here—and it flew apart. I just heard something crack here. A fracture of the coccyx. He hits, and I am silent. He hits, and I am silent. “Почему ты не плачешь? Почему ты не просишься? Почему ты не кричишь? [Why aren’t you crying? Why aren’t you begging? Why aren’t you screaming?]”—and so on, and so on… And I say: “Because it doesn’t hurt.” “Ах, так! У тебя не болит? Тебя нечего бить! Тебя нечего бить! [Oh, really! It doesn’t hurt you? There’s no point in beating you! There’s no point in beating you!]” I had to endure this too in my life. He tortured himself with me for more than a month.

V. Ovsienko: So he was torturing himself or you?

V. Kurylo: I was tormented by him, and he by me. What do you think? That's torture too. He would hit me, bite his nails. I don't know how he didn't swallow them. He was always biting his nails. And finally, he hands me over to another investigator—Ishchenko. And Ishchenko was a KGB man. That one was playing a different game. But since my head hurt so much, I couldn’t tell him anything either. Then they transfer me to a third one—Gorokhov. He was the one who finished my case… They wrote up this thick... indictment. So when they arrested me for the second time, on January 30, 1980, they laughed. They had requested this first case file and were laughing at it: “Look,” said Boyechko, “we will have a mountain of files on you like this, we have material. And they wrote nothing on you. Вот, что это за дело? [What kind of case is this?]”—that Boyechko was laughing.

The investigation was concluded. I signed off on the charges, and they put me on trial. They give me ten years in Siberia and five years of exile.

V. Ovsienko: Do you remember the date of the trial?

V. Kurylo: I have it written down somewhere. February 27, 1947—that’s when they gave me the sentence.

Ukhta

After that, they transport me to Ukhta. I had to endure a lot along the way. I thought I wouldn’t make it to my destination because of the beatings, hunger, bedbugs, cold…

Here is one episode. The train is moving (they were transporting us in freight cars). An old woman died there. For three days, the blatnye took her bread and tyulka rations, not admitting she was dead. When she began to decompose, they started banging. The guards came (they had contact through the cars): “В чем дело? [What's the matter?]” “Заберите, вот видите, человек загнивает, почему не заберете? [Take her away, you see, the person is rotting, why don’t you take her away?]” They gave a signal, the train slowed down for a second, they take her by the legs—by the arms, and throw her into the snow. They threw her out, a signal—and they moved on. Seventy-three years old, a grandmother from Ternopil oblast... That's how the Chekists treated our people who fought for the freedom of Ukraine, for the freedom of the Ukrainian people, for this long-suffering, tear-soaked, prayed-for freedom, which some today so easily despise, and perhaps even sell!

They transported us for almost a month. They brought us to Ukhta. In Ukhta, they sorted us out, washed us, and told us that we would live here. There were old barracks there, but we didn’t yet know that this was the city itself. I was lucky in that there was a neuropsychiatric department there. Because my head was in pretty bad shape. I get to a certain Dr. Sokolovsky. He had been imprisoned earlier. He examined me: “It's alright, we will treat you as an outpatient.” He really helped me a lot.

They sent me to a stone quarry. Forty degrees below zero. We were breaking stone, smashing it into pieces—they were making a road out of it.

There was a poor boy there (he was from somewhere in Leningrad), very poorly dressed. You could practically see through his clothes. He didn't pick up a shovel, nothing, he just kept saying: “I’m freezing! I’m freezing!” The guard: “Будешь работать – согреешься! [If you work, you’ll get warm!]” But he said: “I can’t work!” “Ах, не можешь? Садись! [Oh, you can’t? Sit down!]” He made him sit. The boy sat in a huddled position and no longer asked for anything. He didn't ask for a long time. Finally: “Поднимайся! [Get up!]” But he was dead! Frozen! And what happens then? The prisoners (there were many of our people there, and non-politicals too) quite unitedly rushed the convoy. They rushed at that guard and tore him to pieces. Then the other guards started shooting in the air, then just into the crowd of prisoners. There were many wounded. Red flares were fired. Instantly, as if it weren't night, the camp administration arrived: the camp commander, the head of the regime, other officials: “Что такое? Что такое? [What's going on? What's going on?]” “Вот что сделали бандиты – убили конвоира! [This is what the bandits did—they killed a guard!]” He doesn't mention that he killed a man... Well, then they took everyone off work, drove them into the zone, and didn't take them to the dining hall as usual, but put everyone in the barracks—and locked them in: drop dead!

So that's what happened in that Vetlosyan. After that, they were somehow more careful with them. They tried to give them gloves, some valenki [felt boots]. Torn, but valenki. This had some effect.

My health deteriorated so much that I could no longer walk. I couldn't walk! They put me in the hospital. I weighed 43 kilograms at my height. That's a small child! A nurse, named Peria, I remember, an Estonian girl, would come to me, pick me up in her arms, and carry me, change my sheets. And put me back down. Like a child! I lay there for a while. And from there, they transfer me to the OP, the so-called health-improvement point. There was a musician there named Vitaliy, one of ours. A very good person. He was in charge of this OP. And he always gave me: a bigger piece of bread, some fish, an extra spoonful of balanda. He took care of me, this fellow.

I got stronger. Somehow, the head of the bathhouse, Pavlo Solomonovych, a Jew, noticed me: “Приходите ко мне работать! [Come and work for me!]” I came: “Hello!” “Здравствуйте! [Hello!]” “Как ваша фамилия? [What’s your last name?]” “So and so.” “Вы – бандеровец? [Are you a Banderite?]” “Yes!” “Вы долго уже сидите? [Have you been in long?]” I told him how long. “Вы можете прийти к нам в баню, будете белье стирать? [Can you come to our bathhouse, you'll wash laundry?]” Work in the bathhouse? That’s not the stone quarry! I say: “I will gladly go to you and work honestly and conscientiously.” “Хорошо, завтра вы будете работать у меня. Но у меня очень тяжелая работа. Надо будет наносить дров, набросать снега в баки, поджечь, разогреть воду, тогда замочить белье, а потом только стирать, когда белье немного отмокнет. Шахтерское белье – это страшный труд. [Good, tomorrow you'll work for me. But my work is very hard. You’ll have to carry firewood, throw snow into tanks, light the fire, heat the water, then soak the laundry, and only then wash it, after the laundry has soaked a bit. The miners’ laundry—that's terrible labor.]”

But I took it on. The guys from the kitchen started bringing their overalls to me. And when you bring overalls—there's already something hidden there: a meat patty or something else. And then they said: “And you bring what you’ve washed to us in the kitchen.” That's how I saved myself.

But somehow Pavlo Solomonovych found out that I was a medic and said: “Слушай, я тебя устрою в амбулаторию. Пойдешь? [Listen, I'll get you a job in the infirmary. Will you go?]” “Gladly, I'm a specialist.” “Хорошо, я переговорю с заведующим амбулаторией. Есть такой Петропавловский, он с тобой переговорит. [Good, I’ll talk to the head of the infirmary. There’s a Petropavlovsky, he’ll talk with you.]” “Хорошо! [Good!]” He calls me the next day: “Вы медик? [Are you a medic?]” “Yes.” “Напишите мне рецепт на хлористый кальций! [Write me a prescription for calcium chloride!]” I immediately put the date and wrote: “Recipe de tortalis doses, solici calcii chlorati”, 10%, to be taken 1 spoonful, so and so, I wrote it all down. And he: “Прекрасно! Все, будете работать! [Excellent! That's it, you'll work!]” He didn't ask me anything else.

V. Ovsienko: He gave you a kind of exam?

V. Kurylo: Yes, he gave me an exam to see if I knew. And if I hadn't known—he wouldn't have hired me. But I didn't work in the infirmary for long. By the way, Ostap Vyshnia worked there. He returned to freedom and died in Kyiv. They told me how he made everyone laugh, what a letter he wrote: “I’m no longer a vishnya [cherry], I’m just a pit from a cherry.”

They transferred me to the reception ward. There was a Pole there named Mendrun. An absolute scoundrel! A debaucher of debauchers. He didn't care if she was a free employee or a prisoner... They take him from the reception ward, and they put me in his place. The head doctor, a certain Yosya-zhid [Yosya the Kike], Kaminsky, appointed me. He says: “Будете запис вести. Ви то все знаєте. Робіть. [You will keep records. You know all that. Get to it.]”

I worked there for a while—they take me to surgery. There was a Dr. Ditelman there. That Ditelman took a real liking to me. I assisted him in operations. There was a Dr. Belinskaya (a very nice free employee), there was Kalchenko, also a doctor. We worked well together, they grew to love me.

V. Ovsienko: They were free, right?

V. Kurylo: Free. But one day after an operation, I go out into the corridor, and something here: a stab of pain. I go: “Oh, oh, oh!” I bent over and stood there. And Dr. Ditelman saw me bent over: “What’s wrong with you?” “Something just started hurting here.” And he: tap-tap-tap: “Go, let them change you. Prepare the operating table quickly!” They put me on the operating table right away. They operated on me, I lay there for a whole month, with a temperature of 40-41 degrees [104-105.8 F].

V. Ovsienko: What did you have?

V. Kurylo: They said it was adhesions. An old free-hire woman, a Russian, a senior nurse, brought me a little milk. She'd fill a hot water bottle, stuff it in here, tie it up—and in this bottle, she brought me very tasty milk. That's how they saved me. Thank God, I got out of that trouble too.

And then—I fall from a ladder. That was deliberately arranged because they were taking everyone to Vorkuta, and I didn't want to go. I could live there already—I had adapted. There was a Captain Balayev. He calls Dr. Ditelman: “Негайно його на вахту! [Him to the gate immediately!]” “And how can I take him to the gate when he's just had surgery? Come and get him yourself, I don't need him.” “Когда я тебя прооперирую, ты с ‘Горки’ не слезешь! [When I operate on you, you won't get off ‘Gorka’!]” (‘Gorka’ [The Hillock]—a punishment camp near Vetlosyan, located on a high hill. No one returned alive from this camp). Balayev then says: “Сейчас я посмотрю, насколько ты врешь [Now I'll see how much you're lying],”—to the doctor. That Major Balayev. The executioner of executioners, a worse camp commander—I have not met in all my years. And suddenly I hear: tap-tap-tap down the corridor. And I go: “O-o-o-o-o-o, o-o-o-o-o-o, v-o-o-o-o-o-o”—you understand, I'm vomiting, vomiting, spitting, everything in the world, I already understood everything: I'm a sly one (that's what Horyn used to tell me, that I'm sly). They all look—and I'm under anesthesia. They really did give me anesthesia. I'm thrashing about, the orderlies are holding me, but I'm breaking free. They watched, watched, waved their hand, got up and left. They left. The doctor comes, pats me: “Lie down and get well!”

VORKUTA. VETLOSYAN

I lay there for a month after that. It was nice. But I thought that they had already been sent to Vorkuta—and everything was fine. But no way! One evening a “black raven” arrives, they enter: “Забирайся з речами! [Get your things!]” “Куди? [Where?]” “Я не знаю, забирай речі! [I don't know, get your things!]” They took my belongings, what I had there, put me in the “black raven” and took me to Ukhta, to a transit barrack. I look, and all the familiar guys are there. And they are already preparing the rail cars, cramming people in. They took us to Vorkuta.

And what was happening there! They gave me the number “1F864”—that was my personal katorga number.

V. Ovsienko: When were you brought to Vorkuta?

V. Kurylo: Let's count—it was already 1949, winter, the beginning of the year. They brought us to the camp—but there was no camp. Where is the camp? A whole column of us, over two thousand people. And the girls there at the back, they lead us in front. There were many girls: from Ternopil, from Lviv region, from Stanyslaviv region. They lead us. “And where?” They say: “They are taking us to the bathhouse.” But you can't see a bathhouse. Finally, we see—steam coming out from under the snow. It turns out there are tunnels there, five meters down. A blizzard, the camp is buried in snow. And they crammed us in there. They kept us in the cold like that, and let in forty or fifty people at a time into the bathhouse. There they give you a spoonful of some liquid soap—they splash it on your head, pour a mug of water on you, you wash your head—and that's it: “Виходь! [Get out!]” And your clothes go into a delouser to steam out the lice. That's all. That's how we survived this bathhouse: whoever wasn't already sick with a cold, got one, because you came out and had to wait until everyone had gone through. The first to go, the last—they were all frozen to the bone.

Then they took me to barrack number 27.

V. Ovsienko: And what was the camp number?

V. Kurylo: Mine No. 29. Mine No. 29, where they shot 376 people during the strike. I'll tell you about it later...

V. Ovsienko: Yes, all in due order.

V. Kurylo: It was horrifying. In this 27th barrack, they gave us some of that balanda to slurp down: we were hungry, exhausted. We ate that watery balanda. Stinking, absolutely stinking! But we ate it, because we had to eat. After that, they distributed us to different places. A commission looks to see what category you had, what they can give you now.

V. Ovsienko: What were the categories?

V. Kurylo: First, second, third. First was heavy physical labor. Second was a bit lighter, and third was already KHO, the camp's economic service section (“khozyaystvenno-lagernaya obsluga” - Ed.). They leave me in the zone. I was very exhausted. Moreover, there was a certificate that I had a head injury, that I had memory loss, that I get lost, I could wander off. They leave me in the zone, give me a job clearing snow. But it's written down that I worked as a laundress. A certain Savva Dmytrovych Krainiy comes along, he was the first secretary of the CC of the Party of the Tajik SSR, a real goose. And he asks: “Who has worked as a laundress?” “I worked as a laundress.” “Підходь сюди! Де ти робив, як, що? [Come over here! Where did you work, how, what?]” I told him briefly, and he: “Підеш завтра в баню. Тебе приймуть туди. [You'll go to the bathhouse tomorrow. They'll take you there.]” I show up. A certain Volodia is already there, a violinist, a wonderful musician, and other guys. I immediately go to wash laundry. I washed for three days. I must have displeased them somehow. And Opolsky, the head of laundry, takes me as his assistant in the linen room. Oh, what joy! I'm already working in the linen room, I've already started to eat better there. I was already bringing food to that Opolsky. I'd already become a gofer! But what could I do? Eating wasn't a problem, because I ate alongside them.

I was running around there for a bit—and after that, they take me to the pharmacy as a pharmacist. I knew medicines well by then. There was a female head, Maria Ivanovna, a free employee, an older woman, there were three Lithuanian boys. Fine boys, they accepted me so warmly. What I didn't know, I asked them, and they explained it to me. I worked as a pharmacist until August 1, 1953.

On March 5, Father Stalin died. Father Stalin... I hear they are creating some kind of organization. And I'm shaking to join it. There was a Pole, Edward Bauts, a colonel in the AK (Armia Krajowa). He is organizing it. I didn’t know what was going to happen, but I quietly overheard that there would be a strike. A strike! Today they were only whispering about it, and by tomorrow morning the brigades didn't go to work. They brought them to the gates—no one went out. They brought the night shift to the gates—instead of letting them into the zone, they turned them back to the mine. An exchange like that. This began on July 25 and lasted until August 1. From July 25 to August 1, 1953.

V. Ovsienko: And were they giving out rations during this time?

V. Kurylo: They hadn't cut off anything for us yet. Then they cut off our water.

V. Ovsienko: And what about those who remained at the mine?

V. Kurylo: They didn’t go into the mine because the strikers threatened them, but they were given food, and we were not. But Bauts ordered (we had a food warehouse in the zone): “No one dares to touch the lock or the window.” Not allowed—it was strictly forbidden. Well, our people were there too—there was the head of the supply room, his name was Kontsevych, there was Dr. Polonsky, Dr. Zaitsev, Dr. Ripetsky. All one group, they were all on strike. There were 2 men from each nationality in the committee. They organized a committee, it deliberated on what to do, how to proceed.

About 3000 people were organized—not only in our camp, but also in other camps, like No. 40, No. 29, No. 27. Everything was aimed at the struggle: to remove the locks, to release the minors, to release the women, to release the old people from prison, to remove the bars and locks from the doors, and not to lead people to work in handcuffs. These were the demands to the Ministry of Justice, to the high command of the prisons. They sent such a demand. Everyone signed it and they sent it. A whole flock of them comes from there. This was on August 1. And from July 25 they hadn't gone to work. The things they did, the provocations they staged to get people to go to work, but the guys were strongly organized. When the warders came in, the guys would search them, because they could bring in knives, they could—who knows—stage some provocation, and then pin it on us. Ivan Otamaniuk, an SB man, was in charge of this.

And so, on the morning of August 1—and there it's daylight around the clock—trucks are coming. Trucks are coming, and coming, and coming... A certain Sava Dmytrovych Kremin came out. He says: "Boys, there will be blood. There will be blood, they will shoot." Well, we are ready for anything, for life and death. We watch what is happening. They are placing barrels around, each barrel filled with sand, next to each barrel—a soldier with a ten-round rifle or a submachine gun. And so on—a line around the camp. On the watchtowers, everywhere, there are machine guns, grenade launchers. Further on, a separate convoy of medical vehicles—a mass of medical vehicles is already on standby, people in white coats are walking around there. Outside the zone, they set up tables. And then a cry comes over the megaphone: "Come out of the zone. Whoever does not come out will be shot.” The boys—not a step forward. They all linked arms and held hands, they didn't come out. No matter what they shouted, how they agitated—no one went outside the zone. Then they turned on the water cannons, the firefighters started drenching them with water. The boys wrestled the water cannons away and wouldn't let them—well, they got doused with water, of course. They retreated with the water cannons. And then a red flare—into the air, but they didn't shoot yet. A group of those provocateurs, camp stooges, stood apart—there were about 8 of them. They stood separately and waited. They weren't in the crowd with everyone else, but to the side (this all happened at the stadium—there was a big stadium there). And when they said: "Come out!"—these ones started running for the gate. At that moment, some, apparently, smart boys with submachine guns let loose—and laid them all out—these very same provocateurs of theirs. It was a terrible blow to them. Then they started shooting. Whoever was a military man, practical, buried his head in the sand and waited, and whoever was one to watch where the bullet was flying—ah! gawked!—and at that moment a bullet would hit him. They were firing from all kinds of weapons. Like hail, bullets rained down on people. The shooting didn't last long, maybe two minutes, but in those two minutes they killed 376 people with that hail, and wounded many more. Afterwards, they took the wounded away in trucks. They grabbed me, tore the white coat off me, because I wanted to help the boys. We had formed such a group. The head of the ChIS (“chast’ intendantskogo snabzheniya” [quartermaster supply unit]), a big hulk, grabbed me like this: “Here,”—he says (what did he call me?)—“участничок [little participant],”—and shoved me out of the zone, and straight into a wagon. Just by the file—they tossed my file aside, asked my name, last name—and into the truck. They began to transport us. I end up at 9/10, at “the tenth,” in the camp.

There I met people like Dr. Suslin and Dr. Zvenyhorodsky, a Pole. Well, and our guys. There was a provocateur—and a decent man from Zakarpattia, Patrus-Karpatsky—maybe you've heard of him?

V. Ovsienko: Of course, he's a writer, and not a bad one.

V. Kurylo: Well, I met him there. There, the Bolsheviks staged another provocation. They got about 70 Georgians together (wherever they gathered them from?), armed them with knives, pikes, and set them on us in the zone. The guys didn't think for long—they were very energetic and experienced guys, mostly katorga prisoners—they broke the stoves (someone tipped them off that there were pikes and knives there), grabbing whatever they could, bricks… When they rushed—it was a real mess… They drove those Georgians into the forbidden zone (and when you step into the forbidden zone, the guard doesn't ask—he shoots!). They started shooting at them from the towers. The Banderites are pushing from here—and they are being shot at from there! It was hell. Then they begged: "Brothers! We won't do it again! Brothers, it was a provocation! They sent us." Then they gathered them all up and led them out of the zone. Where they took them, we don't know. But the Georgians never bothered us again in any camp.

Later, after they took us from there, they said that in that camp, they washed away the blood with hoses, collected the corpses, took them to the dok [lumber yard], where the boards and wood were stored. They piled the corpses there. The wounded—if there was a small wound on an arm, they would chop the arm off at the elbow, a wound on a leg—they would chop the leg off. The doctors were terrible executioners! They didn't want to treat anyone. Heads, though, they didn't cut off—if you were wounded in the head, they would bandage you up one way or another and send you away. They took few to the hospital, because that would have meant filling the hospitals with them and feeding them, so they sent them out to other camps. And so I ended up in this camp 9/10.

I saw a lot there—there was a doctor named Shcheka. How cruelly he tortured our people! A prisoner himself. He was a terrible person. We were kept in that hell for 3 months, in that hunger, with bedbugs. Finally, they transferred us from there to the 32nd mine. There I met our priest, Lubachivsky, with his brother. Lubachivsky Slavik… No, Yevhen Lubachivsky, his own brother. He immediately made it his goal to organize an underground. These are the kind of people who can't be at peace, they started to organize an underground again. There was a Stepan Soroka there—maybe you’ve heard of Soroka? He was writing some appeals there. Finally, Zablotsky, Soroka, and one more come to me. And I’m working in the bathhouse (I even lived there, next to the bathhouse). They come and say: "Surrender your power." I say: "What?" "Surrender your power, your people, the ones you have,"—and they show me knives. I laughed, it was funny to me. And next to me was a very nice guy, Yaroslav, Slavchyk Vodvud—he was my wonderful friend. He says: "Boys, what do you want?" "We want Vasyl to hand over his people today, and we will organize what we understand and what we want." "Alright. That’s it. We’ll hand them over." Well, then I stood up, I say: "Boys, sit down, sit for a bit." I started to speak. I say: "Friends! You are in chains. You don’t know what will happen to you tomorrow, what the Chekists will do to you tomorrow, and you come with knives to whom? To the one who fought for five years for the Ukrainian state, for the freedom of Ukraine, who crawled on his belly across the entire Carpathians? And now you come at him with a knife... Go on," I say, "cut me! Why don’t you? Well, go on and cut me, why aren’t you doing it?" Just like that, you know, my nerves finally gave way. I say: "Take it, stick the knife in me! I’ve been in prisons for so many years, and you—you haven’t sniffed gunpowder, you have no idea what war is. And you come at me with a knife?" And I began to lecture them, I really let them have it… I started to explain history to them—what happened during the Princely era, what happened during the Cossack era, what happened in 1918... I gave a brief overview of our whole history, and I say: "Today, and here of all places, instead of uniting, uniting into a single fist, you come with knives against a brother?!"

And then they wilted: "Forgive us, forgive us, forgive us! We didn’t mean that, we didn't want that, that's not what we want." And I say: "There you go, boys. Learn and keep learning.” We talked like that—and after that, they became my good friends. I heard their confession… They also needed a punch in the face for communion—and that would have been very good.

So at the 32nd mine, Lubachivsky began to organize the boys. He started something like a study group, pretending to read mathematics—he was a teacher. But in reality, the goal was one—to unite our boys. That’s how we survived that 32nd. They dispersed us. Then I said goodbye to Lubachivsky for the last time—I don't know what became of him. They said he was killed.

MULDA. EXILE

And in 1956 they transferred me to zone 19, from where I was released.

V. Ovsienko: That was when the commissions and amnesties began. How were you released?

V. Kurylo: I had no pardon, no amnesty, nothing. They released me because I finished my term. But I still had to serve my exile. From there they kicked me out to Mulda. Mulda—that was a place for only the most inveterate bandits. They didn't want to work, they lived at the expense of those who did. And no one there worked. The state fed them.

So I was released. There was a Vasyl Bereziuk. I lived with him. But he found himself some woman there. I couldn't stay with him any longer, because he was feeding her—was he supposed to feed me too? I didn't have a kopek. I was hungry, I wanted to eat. Seventeen of us lived in a tiny little room. Seventeen men! I had to find some way out.

They advised me: go to the regional health department. I go there, and they tell me: "Go to the mine! You will work as a doctor in the mine." How could I go to the mine? To those friends with whom I suffered together yesterday, was tormented, and today I'd be walking around in a little white coat, showing off in front of them? I say: "No, I won't go there." "Then where? Fine, there's another job for you—Mulda. You'll go to Mulda, the non-politicals are there. You will work in two camps. Will you?" "I will!"

Well, with the non-politicals—what's it to me? I don't have to baptize their children. They send me there, give me an apartment right away. They evict two officers from a room. A little room, a bit bigger than this one. And they settle me there. The head of the regime is right next to me, and there—the head of the KGB. They put me in the middle. As befits a respectable person—one on the side, another behind, and me in the middle. So I started working there. I'd come, see patients, and flee from the zone.

There was an incident where they caught one of their own thugs and were stabbing him with knives. They're stabbing him with knives, but he's already dead. And these "fly-swatters" [guards] tell me: "Go, they won't raise a knife to a white coat. Go at least see who they've killed there and who's doing the killing." Me, foolish and inexperienced (I had no such experience), I ran in there and said: "Boys, what are you doing! He's already dead! Why are you stabbing him?" And then—bam, from behind, someone pushed someone else aside. It seemed like a big bruiser raised a knife and was about to gut me. Do you understand what could have happened to me there? It turns out, another big shot, a blatnoy, grabbed him, punched him in the face, and said: "Who are you raising a knife to? That's our doctor!"

After that, I would enter the zone as one of their own. They would approach me: "Give us narcotics! Give us morphine! Give us promedol!" I'd say: "Boys, I won't give you that. And if I found out someone gave it to you, I'd hang him first in the zone, and you'd watch."

One day I'm seeing patients. A big brute comes in, pulls out a knife, slams it into the table like this, and says: "Either you send me to the prison hospital, or I'll gut you." And I say: "You know what? Put away that little blade, or I'll take it right now, break it, twist it up, and then I'll beat your face in and throw you out the door." And smoke is coming out of me here, pardon the vulgarity, from fear. And he: "Доктор, это шутка! Это – шутка! Я ничего от тебя не хочу. Но у меня есть одна падла, я хочу его замочить. Пожалуйста, оформи на меня историю болезни и отправь меня туда. [Doctor, it’s a joke! It’s a joke! I don’t want anything from you. But I have one scumbag, I want to take him out. Please, write up a medical history for me and send me there.]”

And I was already the head of the medical unit. The head of the medical unit before me had gotten caught with morphine. They jailed him for the morphine. Gave him something like twelve years. I say: "If that's the case, then I'll do it for you!" I go to the operative department and say: "Here's the thing, I have a patient, seriously ill—hypertension.” You know, paper will endure anything. “Send him to the prison hospital." "За чем задержка? Хорошо, только оформи, чтобы он в дороге не умер. [What's the delay? Good, just fill out the forms so he doesn't die on the way.]” "Он не помрет! [He won't die!]” “Кто он? А-а! Очмель! Мы его знаем. Ну, ничего, мы его избавимся, только напиши хорошо! [Who is he? Ah! Ochmel! We know him. Well, alright, we’ll get rid of him, just write it up well!]” “Хорошо [Good].” I wrote it up, and they sent him away. What happened to him and what he did there, I wasn't interested. The fact is, it had to be done that way, there was no other way.

I worked in that Mulda for almost two years. They paid me good money there, gave me an apartment. But they are already letting people go free. It's Khrushchev now, I think?

V. Ovsienko: Since 1956—Khrushchev. Even earlier.

V. Kurylo: They are letting me go. I got the itch—let me go free! I went to the regional health department. There was a Colonel Gherzen, head of the regional health department. He says: “Vasyl Oleksiyovych, don't go to Ukraine! I will provide you with work here. You will have a job, an apartment, you will live like a king. But in Ukraine—I'm telling you—you don't know what's going on there, but I do. But if you insist—go. But if it's bad for you there, then come back—I will provide you with work again.” Such a Chekist he was. But there was some human soul in him. He lets me go. In 1957, on October 23, I left Vorkuta. It was snowing when I left.

IN THE LVIV REGION

When I arrived in Lviv, or more precisely, in the Lviv oblast, in the Radekhiv district, the police and KGB summoned me within two days. A certain Solomko summons me to his office and starts questioning me: "Зачем ты приехал? Зачем ты заехал? Уезжай! Убегай, потому что тебе здесь жизни нет! Ты же знаешь, что ты здесь натворил. Ты знаешь, – то-то, то-то. [Why did you come? Why did you come here? Leave! Run away, because there's no life for you here! You know what you did here. You know, this and that.]" I tell him: "I haven't done anything here! Please, do what you want, I'm not leaving here." So this stubborn Boiko remained here, in the Lviv region.

This was my experience… This is what I, poor soul, had to endure… But I thank God that the Lord God helped me at every step, I remained alive and well! As you see, besides the fact that my liver hurts, besides the fact that I am blind, have remained in darkness, that it's hard for me to breathe, have cardiopulmonary insufficiency, that I have a stomach ulcer, two heart attacks... One heart attack was completely untreated. There, in my second arrest, in the Urals, they didn't treat me. And for all this I earned a pension of 54 hryvnias, and my dear wife gets 10 hryvnias for taking care of me, for worrying about me, for guiding me—she gets 10 hryvnias. That's how we live and rejoice, and thank God that we are on our own land, that we are among our own people, that we can tell other people about what we have endured, and guide people towards good deeds, towards the struggle against the evil enemies, of which we still have many.

V. Ovsienko: But you haven't told everything yet. You served ten years, and that wasn't enough for you?

V. Kurylo: Ah, that's another matter. I brought a whole suitcase of literature from Vorkuta.

V. Ovsienko: What kind?

V. Kurylo: Underground literature.

V. Ovsienko: So there was an underground there?

V. Kurylo: Yes, yes, a Ukrainian underground. The same Lubachivsky, Soroka, Yaroslav, Omelian Pryshliak, who lives in Mykolaiv on the Dniester, Yaroslav and Volodymyr from Mizen (I've forgotten their last names)—we were all involved in this. We were divided like this: each one had two people with him just in case. We studied the rules, what to do if we got separated. We only overlooked one thing: each person had only one address. So some remembered, like I did, thank God, but there were people who didn't remember. And everything was lost with them, went to dust. But it was established so as not to fall into the hands of the Chekists, so as not to betray ourselves and someone else.

So I brought literature with me. For 25 years after my first imprisonment, they watched me. For two years, they didn't give me a job. They hounded me like a puppy. They gave me absolutely no residence permit. This Solomko pressured me to go to Karaganda or back where I came from, otherwise, there would be no life for me. He wore me down so much that I decided: I'll go! I went to Radekhiv to buy a ticket. But, luckily, I didn't buy a ticket. On my way back home, I drank water from a well—and I got a terrible headache. And stomach pain, diarrhea, and so on. They called a doctor for me. He said I had typhoid. Typhoid! My head was aching terribly. And my head had been aching ever since they beat me. My head is like a crushed swede…

Then they hospitalize me in Lopatyn. There was a doctor there, Oliynyk. He himself had served ten years and worked as a therapist. He treated me. He took care of me, gave me medicines, various injections, IV drips. They pumped twelve liters of water into me. And so I recovered. And when I was in a comatose state, the prosecutor calls the head doctor: “Так, как он там? [So, how is he?]”—to the head doctor. And the head doctor was a man who walked on one leg, a disabled war veteran. He says: “Та він при смерті [Well, he's at death's door].” “Да? Он помрет скоро? А-а, ну если так, то нужно его прописать, нужно же будет его похоронить. [Really? He'll die soon? Ah, well if so, then we need to register him, he'll need to be buried.]” This is very important: “Нужно прописать, потому что нужно будет похоронить [He needs to be registered because he'll need to be buried].” Fine, they went to the passport office to register me temporarily. And the head of the passport office was a Georgian: “Да какое может быть временно – прописать его постоянно и все! [What do you mean temporary—register him permanently and that’s it!]” Slams the stamp, signed it, filled out the passport, handed it over. And that's it! You know, when I received the passport, when I received this residence permit—oh, I rejoiced! I felt myself getting healthier. Every day I became healthier, and healthier. And I'm healthy to this day.

V. Ovsienko: So where did they register you? In Lopatyn, or where?

V. Kurylo: In Lopatyn, yes.

V. Ovsienko: That must have been around 1959?

V. Kurylo: When they registered me, I went to fight for a job. Finally, in March 1959, the head doctor of the hospital in the village of Shchurovychi, Lopatyn district, hired me as a vaccinator. Later, they transferred me to the position of a visiting nurse, head of a medical post in the village of Triytsi, Radekhiv district, then as a pediatrician in the village of Ohliadiv in the same district. I worked like this until February 1974.

In 1963, when I was working as a district pediatrician in Shchurovychi, I suddenly went blind, completely lost my sight. From the district, they sent me for treatment to Lviv, to the medical institute. I was there for almost a year, and then continued treatment in Kyiv. After Kyiv, there was also a sanatorium in Irpin. Thus, I managed to restore 70% of my vision. However, in February 1974, they sent me to the Lviv Medical Institute for massage therapy courses, because my eyesight was getting worse and worse: they had already assigned me to the second disability group. One day, while I was studying in the courses and simultaneously doing practical training, the course supervisor approaches me and says: “Please take off your coat, because you have no right to either study or work.” I took off the coat and decided to seek protection at the regional health department. And there was a certain Roman Yaroslavovych Monastyrsky there. I come to him and ask for a job. I wrote an application, by the book—I know how it’s done. And he says: "What? A job? We don't give jobs to criminals!" This—an intellectual… He’s still in Lviv today. "We don't give criminals... Why were you in Czechoslovakia?"—He already knew everything, the KGB man. (That while in the underground, I had studied by correspondence at the Poděbrady University in the literary faculty). I reply: "I came to you for a job, not for an interrogation. Please, leave that function to others. And as for me, if you can, hire me..." "No. I don't have a job for you. Goodbye." I left.

Well, what to do? Where to go? But you have to live. I'm walking and I'm almost crying.