I TESTIFY

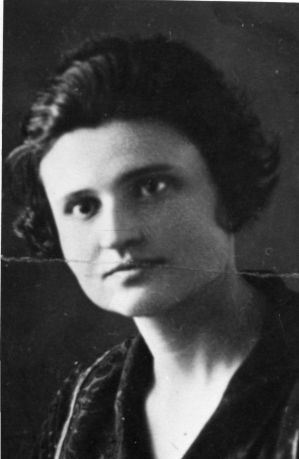

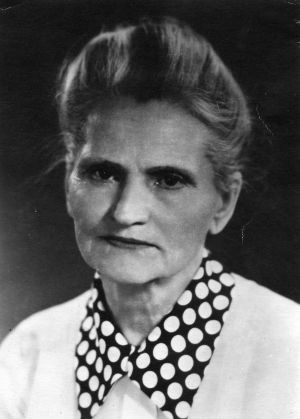

An Interview with Oksana Yakivna MESHKO

Recorded by Vasyl Mykytovych SKRYPKA on January 30, 31, and February 1, 1990

at her apartment at 16 Verbolozna Street in Kyiv.

Published in the journal “Kuryer Kryvbasu” under the title “The Mother of Ukrainian Democracy” in 1994 and as a separate brochure “I Testify” in 1996. Verified against the audio recording. Subheadings by the editor of the second edition, notes by Oles Serhiyenko.

V. Skrypka: The years have rumbled by, flown by... It’s been a quarter of a century, Oksana Yakivna, since we met—sometime in the mid-1960s—and it’s been that long until now. We used to meet more often, but there was a break in the 70s. It was caused by your imprisonment and my own turmoil, my various misfortunes. But you should know that you have always stood so high in my thoughts, in my mind, in my heart! When I learned that you, at 75 years old, had been sent away to the Sea of Okhotsk, you can't imagine how my whole soul went numb! How I suffered, how I thought about those who sent you to such torment! How cruel, how inhuman, and perhaps even how confused and doomed one must be to send an elderly person to such a remote place, to what they call the back of beyond. What’s there to do there! As you told me, for three days, the blizzard raged and buried your log cabin, where they’d thrown you. And how you then promised a bottle to the people—to whoever would dig you out. And after they dug you out of the snow, the guards warned those people not to do it again. And those people wouldn't agree to dig you out even for a bottle—that's neglecting the most elementary human act! A person is buried in snow—let her lie there, let her perish! Later, that Lyubka or Lyuda dug you out, just thirty meters from the road.

But you fought your way out of the snows and you are alive. And when I told this sad story about you to a friend of mine, he said, “What funny people, these countrymen of mine! If there were five grannies like that in Ukraine, the entire KGB would have a heart attack!”

Oksana Yakivna! Young people like me. I think it’s because I know our people a little, I know how they live. And I've scraped a bit of their wisdom onto the tip of my knife and, in my musings, in my sometimes unrestrained chatter, I pass it on. And I love old people. I sometimes think: we will yet call out, summon those people, fall at their footsteps, search for the traces of those people to nourish our spirit, to be reborn. And we won't always succeed, because much is disappearing, and we fail to reach those tablets that sustain us in this world.

I'm thinking now: maybe we could meet again in 10 years? My God, what's 10 years? The average prison sentence—oh, that's no small thing. I haven't been in prison—God forbid, I haven't. Vasyl Stus said he wouldn't survive a second term, and indeed he didn't. It’s hard there, so hard—that's 10 years! In the year 2000, if God grants us health, if we were to meet, I would talk with you again. So much would have changed in this life, and maybe we would be witnesses to those events. As my Grandpa Stets used to say (that was his nickname in my village): “I so want to see, I so want to live to see how all this will end.”

Once, Oksana Yakivna, I was among Western Ukrainians—proud people, so proud! They carry themselves so straight. They don't even lean over the table when they bring a spoon to their mouths. It's as if they live standing up, holding themselves so tall. I told them: “Oh, people, people! If only you knew what happened to us, the people from the Dnipro region, how they hounded us, how our people were destroyed and suffocated! If only you knew! From your milieu, fifty-fifty, decent people emerge. Half of them are crystal! And the other half can be scoundrels. But here, in the steppes of Ukraine, you're lucky if one in a thousand thinks about Ukraine, about its fate, about its future.”

And you, Oksana Yakivna, you are from the steppes. I was stunned when I found out you were from the Dnipropetrovsk region. And you reached heights where everyone sees you and respects you. And from that contemplation, they themselves become better people. That is what’s important, Oksana Yakivna!

Congratulating you on your 85th birthday, I wish for your next milestone to arrive in a free, independent state.

Glory to Ukraine. Vasyl Skrypka.

Dear Oksana Yakivna! I would like to ask you for a short interview. The first question I'd like to ask is: where are you from, and who were your parents?

FAMILY

O. Ya. Meshko: I am from the Poltava region. I was born twenty kilometers from Poltava, in a large old Cossack village-town called Stari Sanzhary. It is a picturesque corner of Ukraine on the Vorskla River. Five churches with their bell towers stood tall. The village was situated on five hills, lively and cheerful, with windmills, and in the evenings, filled with our Poltava songs, which still ring out today, but only in singing groups.

My parents were half-peasants, half-merchants, because they were landless. And it was very difficult to feed a family without a steady income in the densely populated Poltava region. My father, in addition to this, planted orchards throughout the whole area. He graduated from the Poltava School of Horticulture. Gardening was his favorite occupation. He loved working with the land. He didn't like to trade, but he had to in order to support his large family.* *(Her mother Marusia—a smart, cheerful, sociable woman—worked behind the counter. Villagers eagerly came to her for ordered goods, news, and pleasant conversation. – Note by Oleksandr Serhiyenko, Oksana Meshko's son).

The village belonged to the Cossack estate. It never knew serfdom, and that free Cossack spirit was felt in the entire peasant way of life. These were free, independent people. I bless my little town, where I lived my best years—the years of my childhood. But my childhood ended very early. As early as 1919, the working rhythm of this quiet peasant life was shattered by the revolutionary waves.

V. Skrypka: Oksana Yakivna, how exactly did these revolutionary waves manifest themselves?

O. Ya. Meshko: The village accepted the Ukrainian People's Republic, its government—the Central Rada, then the Directory. The Peasant Congress supported this government; it had authority and honor, and it enjoyed respect and full support. But it was driven out of Ukraine. Its place in the village was taken by the absolute dregs of society, idle people who commanded no respect among the peasants. This was when the red soviets took everything into their hands. How did it happen in our town? Five men ran the village. At night they hid from people, and during the day they used the help of red detachments that came from the city of Poltava. These red detachments, upon entering the village, robbed the peasants, taking their belongings, more or less valuable clothing, not to mention other valuables. They also repressed those people who, in their opinion, did not obey them.

And what did that disobedience consist of? A food tax was imposed on the village. The village paid the food tax, but after the food tax came the food requisitioning. They paid the food requisitioning—and then a new tax. And so on, endlessly. When the village had nothing left to pay with, they selected the most respected and relatively well-off people and made them responsible. My father was among these hostages. One day, when a red detachment came to Stari Sanzhary for such executions, my father was arrested and transferred to the GubChK. My father never returned home. At the end of 1920, he was shot on Kholodna Hora in Kharkiv. We received written notification of his death in 1921. Even before that, my younger brother Yevhen Meshko had ended up in a rebel detachment in the village of Bulanne, not far from Stari Sanzhary. The detachment was led by Bilenky. Yevhen was killed in some battle at the age of 19.* *(Yevhen, b. 1903, was respected among the village youth, and for this reason, the new authorities began to hunt him down. – Note by O. Serhiyenko).

My brother Ivan* *(The eldest, b. 1901. – Note by O. Serhiyenko), fleeing the red terror, volunteered for the Red Army, as there was no other way to save himself. Meanwhile, our entire family—our mother and two younger children, including me—were kicked out of our home. We were left without a roof over our heads. Our grandmother—our father's mother—took us into her little old hut. Later, Ivan appeared in the village with a red detachment. He came to the local administration as an insurgent, as a Red Army volunteer, and thanks to him, our house was returned to us.

We returned to our house, but there was nothing to do there anymore. We all scattered across Ukraine, wherever we could. I went to Poltava, worked there, and started my studies in secondary school. Later, I studied at the Dnipropetrovsk Institute of Public Education (INO).

Life was very hard. Constantly persecuted, constant interrogations, certificates stating I was from a kulak family. But by the standards of the time, we didn't belong to the kulaks, we didn't even qualify as middle peasants. This part of Ukraine, the Poltava region—I don't know how many wealthy people it had. These were landless but industrious people.

V. Skrypka: Dear Oksana Yakivna, I didn't want to interrupt you, but your father's death was a widespread phenomenon, which Korolenko protested against in his famous letters to Lunacharsky—this is written about in the journals "Novy Mir" No. 10 for 1988 and “Rodina,” 1989, No. 10.

O. Ya. Meshko: It was a phenomenon that was completely incomprehensible to the people of the town—people who were brave, familiar with military affairs, but unaccustomed to such a form of governance: five men, some sort of scum, the most worthless people, who hid at night and terrorized by day, relying on the red detachments from Poltava. They took the most prosperous and respected as hostages. And so my father was taken—he was not the first or the last to be arrested and shot. Kholodna Hora was a Ukrainian auto-da-fé, where so many people perished. They were shot and buried in a mass grave. Without a coffin, without any rites—so that people wouldn't see. And it's unknown where—no graves were marked.

V. Skrypka: There was no peaceful life, and then the war began. As one old man told me, he's not a true Soviet man who hasn't been in prison. So, Oksana Yakivna, perhaps we should move on to the most sorrowful and bitter part of your life—your arrest.

BETWEEN LIFE AND DEATH

O. Ya. Meshko: I was arrested in February 1947. Arrested for no reason at all—as if I were stolen. Right on a street in Kyiv, four young thugs in white sheepskin coats threw me into a car and took me to the republican NKVD. I received 10 years merely for sympathizing with my older sister, Vira Khudenko, whose son was in the insurgent detachments in Western Ukraine.

Vira was alone at that time. Her son and daughter-in-law had been arrested, and her husband* *(He was already nearly 70. – Note by O. Serhiyenko) was taken in a raid for no reason, simply because he happened to be in Western Ukraine and was arrested there... She came to me, and I wanted to help her get settled here. She was helpless, without any specific profession. But this, too, was considered a crime, because, you see, I had sheltered the mother of a rebel. Both she and I were punished in the same case, under Article 56, paragraph 8—terrorism. We had supposedly intended to assassinate Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev. There was no evidence, and the investigator in his office told me: “What evidence is needed? We need you to confess to it yourself!” When I said that I could never confess to such an absurdity and would never help an investigator commit lawlessness, he said: “But we'll force you to. You'll be begging us.”

For twenty-one days, they tormented me with sleep deprivation. For twenty-one days, I endured without sleep. No doctor will say that this is possible, but I know it is—I endured it. And I did not confirm any of the self-incriminating confessions that the investigator, Kutsenko, tried to force on me.* *(See more on this in: O. Meshko. Mizh smertyu i zhyttyam (Between Life and Death). Kyiv: NVP “Yava,” 1991; Oksana Meshko, kozatska matir (Oksana Meshko, a Cossack Mother). On the 90th anniversary of her birth. Kyiv: URP, 1993. – Ed.)

THE THAW

I served 10 years in prison. In 1956, during the Khrushchev Thaw, my case was reviewed. I was simply lucky that it fell into the hands of a more honest prosecutor, and he cleared my sister Vira and me of the stigma of being terrorists. I was rehabilitated and returned to my job at the Kyiv regional consumer union.

I found my only son, Oles, ill (my first son, Yevhen, died at the age of ten in Tambov during a German bombing). I was sustained by the hope of curing him. I also wanted to believe that the Stalinist lawlessness condemned by Khrushchev was gone forever. I believed it. But my belief was built only on my misunderstanding of the situation: Khrushchev was building on sand, and it did not last long. Wave after wave of lawlessness grew. Once again, nothing united Soviet society except fear and the desire to somehow survive, to preserve oneself. A period of spiritual emptiness began, which had a particularly devastating effect on the younger generation.

V. Skrypka: Then came the 60s. That's when I met you. Since then, you have always appeared before me as energetic and full of initiative. Those evenings, where I myself once spoke (at the agricultural academy), the poetry evenings of our glorious Sixtiers poets—Vasyl Symonenko, Mykola Vinhranovsky, Vasyl Stus—undoubtedly united the youth. But that thaw was indeed short-lived. It ended again in terror. And you suffered the most.

O. Ya. Meshko: You have just reminded me of a truly happy period of my life. Back then, when I was in Stalin's camps, I never even imagined that I would return to active public life and to a life of my own choosing. I retired, and when I was free from work, I didn't worry about the “what will I do now” problem, as my peers and many people who retire would say. “Why, that's already death.”

On the very first day of my retirement, I went to my Stari Sanzhary. I walked those roads that were so familiar to me—from Poltava to Stari Sanzhary, through the Pereshchepyne station, I walked through the village. And I was horrified by the changes that had occurred between 1920 and 1963. Just count how many years had passed, while they were telling us about the development, about the flourishing of villages and cities. I looked at our old town, so beautiful, so prosperous once—now it was in ruins! It was worse than right after the occupation. It turns out that there were hardly any Germans there—they passed by somewhere on the side. The village was destroyed by the authorities themselves. People fled the village, from their ancestral homes, as if from a plague. Some to the Donbas, some were exiled to Siberia, some went to the Dnipropetrovsk region to find bread in the factories, some to Zaporizhzhia. Only the old and elderly were left, wandering around their yards like lost souls. I could not accept my village like this. Even the beautiful “Prosvita” building, built according to the design of a famous architect, was destroyed. They said the Germans set it on fire, but witnesses say that our own people destroyed it when the Germans were taking the village.

I walked along our road all the way to the large cemetery, searching for the graves of my ancestors, which I knew very well. The cemetery was so neglected, as if people were no longer buried there. I found my relatives. I found neighbors. I didn't recognize them. All five churches were destroyed—not a stone was left standing. The credit unions, the windmills (both wind- and water-powered)—everything was destroyed.

I returned from my Stari Sanzhary and for several days lived under the impression of the ruin. And then I thought: “I am retired, and I must do something. What should I do?” I must find people who understand the urgent need for our spiritual revival. I found people sympathetic to this idea, people who did not ask, “How much will we be paid for performing at an evening?” I only said one thing: “On a voluntary basis.” And—oh, a miracle! People from the philharmonic, from all cultural institutions—no one ever refused to take part. I held matinees and evenings in twenty Kyiv schools on themes of Ukrainian classics: the Ukrainian song, anniversaries of Shevchenko, Franko, Lesia Ukrainka, Dovzhenko—whatever was on the calendar. In research institutes, clubs, in the Tram and Trolleybus Authority Club...

It was such lively work, I was so engrossed, I had so many acquaintances and friends around me, so many people wanted to help me! Only then did I understand the Soviet reality: people subconsciously want something different, people want work that is of their own choosing, according to their own liking.

In the years 1963–1968, or even until 1969—that’s a whole 6-7 years—I saw that Kyiv was alive, that people were thirsty for cultural, spiritual work, that everyone wanted to make their own contribution. I say that this was the best time of my life, when, it seems to me, I compensated for the years of my forced idleness, of state work for a salary, for a ration of bread and soup in an aluminum bowl, which I received for 10 years in Stalin's camps.

THE HARVEST OF 1972

During that time, I truly seemed to believe in the possibility of some changes. And for me, to be honest, the arrests of January 12, 1972, were completely unexpected. On the same day, at the same time, in the cities of Kyiv, Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Cherkasy, a great many people were arrested—members of the Ukrainian creative intelligentsia, people who never spoke of weapons, people who never spoke of any military formations or any organizations. These were people who spoke of the Ukrainian song, of Ukrainian poetry, of culture.

V. Skrypka: Oksana Yakivna, in 1972, which you're talking about, Shelest was removed. I was told then that on the second day after his “ascension to the throne,” Shcherbytsky sanctioned the arrest of 75 people in Kyiv alone—and you mentioned many cities—these were writers, cultural figures, in a word, the intelligentsia. This is a crime beyond compare. Now in Germany, Honecker has been put on trial, in Bulgaria, Todor Zhivkov. It seems prison is crying out for Shcherbytsky too—what do you think?* *(V. Shcherbytsky was appointed First Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPU in May, whereas the arrests began on January 12. – Ed.).

O. Ya. Meshko: There were indeed many rumors in Kyiv at that time. As for Shcherbytsky, he didn't just appear on his own. Someone sent Shcherbytsky. But as for Vitaliy Vasylyovych Fedorchuk, he came to Kyiv while Shelest was still in power. Shelest did not accept him. Then Moscow co-opted him into the Supreme Soviet, and he began to take charge.* *(V. Fedorchuk was appointed head of the KGB at the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR in July 1970). The arrests happened not under Nikitchenko, but under Fedorchuk. Right after the arrests, KGB agents spread rumors: “We have 3,000 people on our list, but to frighten the Ukrainian intelligentsia, those who have been arrested are enough: Ukrainians are a timid people and are used to Stalinist order.” They laughed, they laughed in the face of the Writers' Union and spoke of it with contempt: “Ukraiyonskiie pismenniki” (a derogatory, distorted Russian for “Ukrainian writers”). They treated them with such disrespect.

And indeed, not a single one of them spoke up in defense of, say, Ivan Svitlychny, Ivan Dzyuba, and others. I myself appealed to Dmytro Pavlychko with a letter-petition for Ivan Svitlychny. I chose a moment at one of the official evenings and approached him. He was frightened, read the letter, but of course, did not sign it. And do you know what his motive was? He said: “I met with a KGB colonel, and the KGB colonel said that there is a corpus delicti in Ivan Svitlychny's case.” I answered him angrily:

“So you consult with a KGB colonel about writers you know well, with whom you were, it seems, on friendly terms?” That's how my petitions to the Writers' Union ended... Dmytro Pavlychko played no small role in the Writers' Union at that time. No one spoke up in defense.

HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENSE

When my son was already in the KGB prison* *(Oles Serhiyenko was also arrested on January 12, 1972. – Ed.), I found him a good lawyer, but I couldn't get in touch with my son. And they appointed their own lawyer for him. I wanted to ignore that lawyer, so I had to address this issue to Fedorchuk himself. A lot of time passed, two or three weeks, and I kept trying to get an audience. Finally, one day I was told that he would see me today. I came with my daughter-in-law* *(Dzvenyslava Vivchar, Dzvinka. – Ed.). They said: “He's at Korneichuk's funeral, but he called from there (whether he called, I don't remember how) and promised to see you—please wait.”* *(O. Ye. Korneichuk died on May 14, 1972. – Ed.) We waited a long time, from morning until about two o'clock. Finally, we were told: “He will see you alone—the mother, but not the wife.” My daughter-in-law was indignant, as was I. “Should I not go?” she asked. “Don't go!” I said, “But I must go now—even if I go alone.”

I went in to see him. It was a long, bright office-hall, with mirrors, a piano, and he was sitting at a table with the prosecutor. They seated me so that the sun was shining in my face. I squinted but recognized the prosecutor for supervision of the KGB investigative bodies. I glanced at him, averted my eyes, and started looking only at Fedorchuk. The prosecutor asked me: “Why aren't you saying anything to me? You've been to see me before, haven't you? Or have you forgotten?” “No, I haven't forgotten, and I also remember what you told me. You told me that the KGB is a reputable and objective organization. So I stood up and said that I have no business with you if it's an organization that one cannot complain about. And you are supposed to be supervising it. So what are you doing there? And now I am appealing only to Fedorchuk—I am counting on him.”

This was such a compliment to Fedorchuk, he was so pleased, he was in a good mood after a hearty meal at Korneichuk's funeral, flushed and red from wine. As I entered, he even stood up and walked towards me—a tall, heavyset man with epaulets, but without a jacket, in a light blue shirt. I thought: “It looks just like a police uniform. MVD.”

Our conversation ended as it was bound to—my request to remove the lawyer Martysh and transfer the case to another, with whom I had an agreement, was not granted.* *(Lawyer Serhiy Makarovych Martysh from the Darnytsia bar association was one of those newly granted clearance for political cases. My mother did not know him. But when I spoke with him in the investigator's office, I sensed a decent person. And I was not mistaken: S. M. Martysh, having familiarized himself with the case, unexpectedly for the court proposed to release me, due to the absence of a corpus delicti in my actions. For this, the KGB revoked his clearance for political cases. When they were fabricating a criminal case of resisting the police against V. Ovsiienko in 1978-79, my mother recommended this defender to him. S. Martysh demanded the defendant's release due to the absence of a corpus delicti and the initiation of a case against the “victim” policeman V. Slavynsky. He had trouble with the KGB again. – Note by O. Serhiyenko).

But this meeting stuck in my memory. While I was talking about my son, I saw into whose hands the KGB had fallen. This was a very limited, self-confident, and cruel man. When I came out and met my daughter-in-law, she looked at me and asked: “What's wrong with you?” I said: “We're lost, Dzvinka, we're all lost!”

And so it happened: everyone was convicted without any guilt or fault. It was a bit strange, perhaps, that so many of our best people ended up behind bars, but no one protested by means of silence, by refusing to sign protocols. The time was not yet ripe for that. They had not yet matured to that point. They still thought that a good, decent conversation could be heard and that truthful conclusions could be drawn from it. But in the KGB, everything was already predetermined, all the sentences were set. They were all convicted. I tried to attend every trial, but they wouldn't let us in; the trials were closed. We would walk around near the courthouse—and the police would chase us away even from there, not even letting us into the reception area.

V. Skrypka: And do you remember, Oksana Yakivna, you also appealed to Mykhailo Stelmakh, and he wrote a petition to the Chairman of the Supreme Court of Ukraine on his deputy's letterhead? How did that end?

O. Ya. Meshko: Imagine this: I, having gone through years of lawlessness and injustice, still wanted to believe and still believed that I could somehow help the arrested! I appealed wherever possible, petitioning for my son. Thanks to you, it seems, I got to see Stelmakh. He received me very graciously. After listening to my case, he was filled with sympathy for me and wrote on that state letterhead his petition for my son, Oleksandr Fedorovych Serhiyenko. That Serhiyenko had committed no crime, that the whole case was fabricated. Even their own lawyer said in court that there was no corpus delicti in Serhiyenko's case, that he should be released from custody today. This statement from the lawyer gave me hope that I could help my son Oleksandr with petitions, and I took up the cause so sincerely. Before Stelmakh, I didn't know what a deputy was, what his functions were. Not believing the government, I never delved into its structure. But about Stelmakh as a writer, I thought: he must be an authority for them!

V. Skrypka: At that time, he was already a Hero of Socialist Labor, a Lenin Prize laureate, and even the Chairman of the Council of Nationalities of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR.

O. Ya. Meshko: Yes. He, as a writer, sincerely understood that I was telling him the plain truth—there was no crime in my Oleksandr's case. He wrote the petition on that state letterhead. He sent it himself. The petition was sent, but then he added: “I will talk to Yakymchuk.” He was the chairman of the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR. He had reception days. Stelmakh went to see Yakymchuk on a reception day. The first time, he was not received, but the second time, Yakymchuk himself called Stelmakh for a visit. He went. I called Stelmakh to ask about the results and heard this: “I spoke with Yakymchuk. Yakymchuk told me how vilely your son is behaving in the camp.” I asked: “And how would you behave if you found yourself behind bars for no reason? And does his behavior in the camp have anything to do with the case? He was convicted for something that didn't happen. We are talking about a review of the court case.” Stelmakh told me: “I cannot help you any further.”

I hung up the phone. Alarmed, surprised, indignant, I even forgot my wallet with my meager pension. This conversation brought me back to the forgotten, long-ago things I had thought about there, in the camp, and what I had wanted to forget after my rehabilitation because I wanted to believe in good. I understood: there is no good in this government, and there is no person who can help against this totalitarian, cruel regime.

Disappointed, but not hopeless, I looked for ways to defend him. The belief that anything could still help was gone, but for my own sake, I wanted to test whether it was possible, whether one should believe.

My deputy was Paton* *(Borys Yevhenovych, academician, President of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR. – Ed.). People go to their deputies with housing issues, with divorces, with other things. But I had an issue that seemed not shameful to bring to a deputy: I was defending my son, who was behind bars without having committed a crime. I told people: I'm going to see Paton. People shushed me: “What are you thinking! How can Paton help you? Paton gave the order at the Academy of Sciences to fire several people from the institutes of linguistics, folklore—people the KGB told him to fire!”

V. Skrypka: Oksana Yakivna, that was a whole purge. If you gathered all those fired from the Academy, you could form a second Academy. I was fired then from the Rylsky Institute of Folklore and Ethnography, and so was Tamara Hirnyk. From the Institute of Literature, Yuriy Badzio, Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, and Viktor Ivanysenko were fired. Not to mention the Institute of Philosophy—Vasyl Lisovy, Yevhen Proniuk; the Institute of History—Yaroslav Dzyra; the Institute of Archeology—Mykhailo Braichevsky... It's a terrible page. A “black hand”—a black and perhaps hairy hand—guided Paton's hand. That needs to be investigated separately... Please continue.

O. Ya. Meshko: But I went to the deputy. The deputy held his reception—where do you think?—at the university. There were two men sitting with him. I took a seat in the queue. Those two men—whether they were monitoring the deputy, I don't know, but I didn't like them. I decided I would speak only with the deputy. I came dressed all in black—that's how I dressed then. Paton received me graciously. He invited me to sit down. He listened to me attentively. The two men sitting nearby made some disapproving remarks about my explanations of my son's innocence. Paton signaled them to be quiet: he listened to me attentively and asked: “I would like to help you. But what would you like?” “I don't want much from you, comrade deputy. I only want the three years of prison, which were added to my son's sentence by a closed court in the camp, to be removed. He was sentenced to 7 years in a camp and 3 years of exile, but from the camp, he was administratively transferred to 3 years in prison by a closed court. And 3 years in prison—that was the term given for murder, for rape, for the worst crimes! I will ask you,” I said, turning to Paton, “to have these three years of prison removed, which is a flagrant violation of Soviet law. I am not asking you to help me review his court case or reduce his sentence—I am only asking for this!” He himself, right there, wrote a petition to the Perm Regional Court with his own hand. He handed it to me and said: “It would be best if you send this yourself.”

I left elated: I had found a man I could trust, a man who could help! But do you think that the President of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine was an authority for the Soviet authoritarian state? Do you think anyone listened to his petition? The petition was sent through the usual bureaucratic channels, disappeared without a trace, and ended up somewhere in a wastebasket. They did not remove that three-year sentence! But when I told people who knew Paton from the Academy of Sciences about this, they were surprised by such a reception. And then someone said: “O-o-oh! Do you know why that happened? His mother had just died then. She was probably about your age.” So, all people are not strangers to human feelings, but only in moments when it affects them personally.

I sent Paton's letter, and in the meantime, I went to Moscow to see the composer Dmitry Kabalevsky. He had been elected as a deputy from the Perm district, and my son was in a camp located in the Perm region. D. Kabalevsky was an authoritative, humane person, known by many people, and he enjoyed the sincere love of the citizens. The composer received me twice. The first time he was alone, and the second time in the presence of his wife. It was a pleasant meeting, and his wife also left a good impression—a kind, sincere person. He also wrote his petition on his letterhead and sent it himself. He even promised: “And I will also try to do this through the Chairman of the Supreme Court of the USSR. That might be effective.”

It ended the same way as with Paton. That is, our deputies have no authority, no influence with the government. They were people elected for show, to deceive the citizens. They were powerless. Dmitry Kabalevsky himself tried to speak with the Chairman of the Supreme Court—but it came to nothing. So I was not able to help my son.

I had one more chance. That was Ivan Dzyuba. Why Ivan Dzyuba specifically? Because my son had committed no crime. He was incriminated with co-authoring Ivan Dzyuba's work “Internationalism or Russification?”. It was comical: the author himself denied it. To incriminate Serhiyenko with authorship, it was enough that, while reading this work, which was being typed at Zinovia Franko's apartment, Oleksandr made some pencil marks on the 33rd page. Zinovia Franko herself told him that Ivan Dzyuba had asked: “Anyone who reads it and has any critical remarks or additions, I kindly ask them to write them boldly on this copy.” And supposedly he also corrected the title itself. In what way? “Internationalism or Russification?”—it wasn't “or Russification,” but something else, I can't recall. Oles didn't like it, he crossed out that word and wrote “or Russification.” Thus, the title itself took on a different, sharper character. And on page 33, he made some comments. This copy was kept by Ivan Dzyuba. It was the first copy, he kept it himself. Serhiyenko's comments—perhaps not all of them—he included in subsequent copies of his work.* *(This is how it was. Arriving late in the evening at Z. Franko's place with Nadiya Svitlychna, Ivan Svitlychny's sister and my wife at the time, I found her proofreading for typos. I began reading the introduction—an address to the Central Committee of the CPU concerning the arrests and the contemporary national policy of the CPSU in Ukraine. It was the notes to this section, which I. Dzyuba found pertinent and incorporated into the text without asking the author, that were incriminated against me. I made no changes to the title. – Note by O. Serhiyenko).

Serhiyenko demanded that Ivan Dzyuba be called to court as a witness, since these were purely a reader's comments; there were no grounds to consider them co-authorship. Then there would have been no grounds at all to open that case. Ivan was not summoned to court. As is known, Ivan Dzyuba was sentenced to 5 years and then pardoned, released from custody. Many people were incriminated for “Internationalism or Russification.” People received long sentences—and Ivan was free. I went to Ivan and reproached him for this very thing.

We arranged to meet by phone and met near the “Bilshovyk” metro station. While waiting, I thought about how I would meet Ivan Dzyuba. I would say that I no longer love him, no longer respect him... No, that's not right: I no longer respect the Ivan Dzyuba whom I had loved so much before his repentance. It was cold. I hid behind a window in the metro, saw some people watching me—I paid no attention. And when I saw Ivan approaching, I came out of the metro. We met.

I knew Ivan—Ivan was tall, with a well-set head, a proud posture. But here I looked: it was Ivan Dzyuba, but something in him had changed, in his walk, in his manner of carrying himself, in his bowed head. Ivan walked under the heavy weight of his apostasy. It had left its mark on him. We walked for a long time, we didn't sit, because I saw we were being followed. I even asked: “Are they following you?” And he said: “I think they're following you too, but pay no mind.” We walked and talked for a long time. I told him everything, I reproached him, and I spoke to him without tears, but with the words a mother speaks in her maternal despair. (Cries). Ivan is good, Ivan is wonderful—I love him. After that meeting, I forgave him. (Cries).

We met a few days later. Ivan wrote a beautiful letter in defense of Oleksandr Serhiyenko. His petition was the kind that only Ivan could write. It was bold, generous, and well-reasoned. I also wrote to the Supreme Court, sending Kabalevsky's letter, Stelmakh's letter, Paton's letter, and Ivan Dzyuba's letter. These were materials that truly needed to be considered. At least one case, selectively, as their law requires. But no one reviewed that case. All those materials settled somewhere in their files. But Ivan Dzyuba, as he said, was never called to account for it.

Such is the illustration of our justice system. I'm not saying this is the only case, but it is one of those characteristic, flagrant violations of legality. Everything was in the hands of the KGB and a lawless court. The judge who tried my son is no longer alive, nor is the prosecutor—young and healthy, yet for some reason, they departed from this life. Whether it was God's punishment, or whether they had crimes on their souls that gave them no peace... I am inclined to think it was their inner repentance, which they did not admit even to themselves, but which was reflected in their short lives.

THE UKRAINIAN HELSINKI GROUP

V. Skrypka: Oksana Yakivna, and when did they come for you?

O. Ya. Meshko: They never liked me. They didn't like me even back when I was organizing those evenings. They knew me from that time. But they liked me even less when I was making efforts to have my son's case reviewed. The fact is, I also turned to three lawyers—one from Leningrad, one from Moscow, and two from Kyiv. I wanted the lawyers to familiarize themselves with my son's case as well. But they wouldn't provide the case file. The lawyers bothered them, demanding the case for review. I annoyed them terribly. A rumor started that I was supposed to have been arrested along with everyone else. But they didn't arrest me—it was inconvenient, a mother and son. I don't know if that's true. I think it's not. They got to know me better after that.

V. Skrypka: Oksana Yakivna, forgive me for interrupting. But wasn't it the founding of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group and your participation in it that really got to them?

O. Ya. Meshko: I was indeed arrested for my participation in the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords. Formally, for that. The verdict I received was 12 pages long, very long, and so anecdotal that if it were published now, it would be a perfect illustration of the mindlessness of our legal system. Even before the founding of the Ukrainian Public Group, after my petitions and visits to Stelmakh, Paton, Kabalevsky, and Ivan Dzyuba, they began to visit me more often—sometimes with a search, sometimes to draw up some interrogation protocol. I refused to speak with them, and then I saw that I was effectively under house arrest! I couldn't go anywhere! They would grab me, put me in a car, take me for a personal search, for a search of my apartment... I was under house arrest! And then I fell ill: pneumonia. They came to see me daily—either alone or with a doctor. I wouldn't open the door—they would come with a doctor. I'd open for the doctor—and they would come in themselves. I then appealed to the prosecutor's office, stating that I considered this situation to be house arrest and asked to be released from such pressure. Prosecutor Tulin came to my home. In his presence, they took my statement (because I didn't want to give them such a statement alone). The prosecutor said: “You are free.” And he told them in front of me: “Stop all this.”

Thus I felt myself free. But I was already so angry, so geared up for a fight: to struggle, to struggle, regardless of anything, stopping at nothing.

In the autumn of 1976, Mykola Danylovych Rudenko came to see me with his wife. He came with a proposal to join the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords. “And who else is in the Group?” I asked. “Well, it's me, and you will be the second.” “But,” I said, “who then will bring packages to my son and send him parcels?” Rudenko was surprised, but without laughing, he said to me: “My God, Oksana Yakivna! You are so frightened that you thought we could be arrested! But our Ukrainian Public Group will be based on the Helsinki Accords, which were concluded on August 1, 1975.”

V. Skrypka: Oksana Yakivna, did you meet with Sakharov on that matter? Or was that later?

O. Ya. Meshko: That was later. So I sat and thought. I said: “There are only two of us right now.” “There will be more of us, Oksana Yakivna, don't be afraid that there are only two of us! We are just forming the core. There will be more of us.” I said: “But you know that we will all be arrested later?” “Oh, no!,” he laughed at this. “We won't be arrested!” I said: “We will be arrested. Because a wolf may shed its coat, but it never changes its nature. Just now, Comrade Rudenko, while defending my son and dealing with our state and judicial institutions, with the justice system, I have become convinced that it's all the same—we will be arrested. But I want to tell you—don't laugh—I am not afraid of being arrested. Because it's even better for me to be arrested. Because it's hard for me to live now. I can't live like this anymore.”

I agreed. I was the second member. We founded the Ukrainian Public Group. There were ten of us brave ones at first. They were Mykola Danylovych Rudenko, myself, Mykola Matusevych and Myroslav Marynovych, Nina Strokata, Levko Lukianenko, Ivan Kandyba, and General Petro Grigorenko—as the Moscow coordinator of our Group.

V. Skrypka: And Oleksa Tykhy came later?

O. Ya. Meshko: No, Oleksa Tykhy was there right away, and Lukianenko—there were 10 of us at the beginning. Two were in exile—Kandyba and Strokata were under administrative supervision without the right to leave their towns and without the right to leave their homes from 9 p.m. to 7 a.m. Tykhy was in the Donbas, Lukianenko in Chernihiv, Rudenko and I were in Kyiv, and Oles Berdnyk also joined us. That makes exactly 10 of us. Oles Berdnyk was the third member by count. Then came Tykhy and Lukianenko, then Matusevych and Marynovych, then Kandyba and Strokata.

I divided my duties regarding my son with my daughter-in-law in this way: you look after your little son—I will take care of my big son. He doesn't need a nanny—they are nannying him well enough there, and I will take on everything else that is needed. I had no other path left.

It was then that I truly embarked on the path of struggle. It was an unusual struggle. It was the first legal struggle in our history. In our human rights documents—because our main idea was the defense of human rights and the rights of the nation—we would refer to the Final Act of the Helsinki Conference and officially send them to the governments of the 34 signatory countries and the 35th—the Soviet government. This was the first opportunity that could not be ignored, that could not be relied upon. It was an opportunity to fight them on the basis of international legal documents that they themselves had adopted. They themselves gave this trump card to our democratic association.

V. Skrypka: Oksana Yakivna, you mentioned the press bulletins that the Helsinki Group sent to 34 countries and the USSR. What effect did they have?

O. Ya. Meshko: Our memorandums, declaration, and information about the state of human rights in Ukraine became known not only within the Soviet Union, because we addressed these documents not only to the Soviet government but also sent them through embassies to all the member countries of the Helsinki forum. Radio stations around the world broadcast these materials, popularizing them. The Group became very well-known in the world, despite being very small. There were 10 of us at first. The first five, with Berdnyk as the sixth, were deprived of the ability to work because they were arrested. The seventh, Grigorenko, ended up abroad. At liberty, so to speak, there were three of us left—me, Ivan Kandyba under supervision in Pustomyty, Lviv region, and Nina Strokata under supervision in Tarusa, Kaluga region—without the right to travel. Administrative supervision also dictated the hours they had to be in their homes: from 9 p.m. to 7 a.m., they were not allowed to leave their residences.

So, I stood alone like a rock, like a thorn in the KGB's side, and stormed ahead.* *(Here is a chronicle of the losses that Oksana Yakivna's heart endured—the arrests of Group members and those close to them:

February 5, 1977 – Mykola Rudenko (Kyiv) and Oleksa Tykhy (Donetsk region)

March 2, 1977 – Vasyl Barladianu (Odesa)

April 23, 1977 – Mykola Matusevych and Myroslav Marynovych

September 22, 1977 – Heliy Sniehiryov

December 8, 1977 – Petro Vins

December 12, 1977 – Levko Lukianenko (Chernihiv)

February 15, 1978 – Petro Vins (a second time)

December 8, 1978 – Yosyf Zisels (Chernivtsi)

February 8, 1979 – Vasyl Ovsiienko (Zhytomyr region)

March 6, 1979 – Oles Berdnyk

March 9, 1979 – death of Mykhailo Melnyk (Kyiv region)

July 6, 1979 – Petro and Vasyl Sichko (Dolyna, Ivano-Frankivsk region)

August 6, 1979 – Yuriy Lytvyn (Kyiv region)

October 3, 1979 – Petro Rozumny (Dnipropetrovsk region)

October 23, 1979 – Vasyl Striltsiv (Dolyna, Ivano-Frankivsk region)

October 23, 1979 – Mykola Horbal

November 15, 1979 – Yaroslav Lesiv (Ivano-Frankivsk region)

November 29, 1979 – Vitaliy Kalynychenko (Dnipropetrovsk region)

January 1, 1980 – Volodymyr Malynkovych expelled

February 20, 1980 – Hanna Mykhailenko (Odesa)

March 12, 1980 – Zinoviy Krasivsky (Morshyn, Lviv region)

March 12, 1980 – Olha Heiko-Matusevych

April 2, 1980 – Vyacheslav Chornovil (Yakutia)

April 11, 1980 – Ivan Sokulsky (Dnipropetrovsk region)

May 14, 1980 – Vasyl Stus

June 30, 1980 – Dmytro Mazur (Zhytomyr region)

July 1, 1980 – Hryhoriy Prykhodko (Dnipropetrovsk region)

After Oksana Meshko's imprisonment on November 13, 1980, they “scraped out” the rest:

March 23, 1981 – Ivan Kandyba (Lviv region)

August 15, 1981 – Raisa Rudenko

December 3, 1981 – Mykhailo Horyn (Lviv)

September 2, 1982 – Zorian Popadiuk (Aktyubinsk region, Kazakhstan)

October 21, 1983 – Valeriy Marchenko

November 29, 1985 – Petro Ruban (Pryluky, Chernihiv region)

– Ed. Note)

I experienced terrible pressure from the authorities. Constant searches, they would catch me on the street, force me into a car, take me to the KGB, interrogate me, and urge me to abandon this work, warning me that it would end badly. But by that time, I had lost my fear. Not only was I no longer afraid of anything, but I considered it my civic duty, my calling, since my age seemed to put me in the best position. But that's just what I thought... * *(Here is a chronicle of just some of the searches and detentions:

February 5, 1977 – search in the case of M. Rudenko and O. Tykhy, sanctioned by the Moscow city prosecutor;

June 12, 1977 – visit with son (together with daughter-in-law Zvenyslava Vivchar) at camp VS-589/36 in the village of Kuchino, Perm region. Personal search before and after the visit;

January 1978 – search and interrogation;

February 9, 1978 – search in the case of L. Lukianenko;

February 14, 1978 – 5-hour interrogation and warning of criminal liability under the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of December 25, 1972;

June 17, 1978 – O. Meshko was removed from the bus she was taking to L. Lukianenko's trial in Horodnia and sent back to Kyiv;

November 3, 1978 – armed attack on O. Meshko;

November 18, 1978 – detention and search (together with Olha Orlova-Babych) in the village of Lenine (Stavky) in the Zhytomyr region, where they visited Vasyl Ovsiienko;

March 6-7, 1979 – search; Hrytsko Miniailo, Volodymyr Malynkovych, Klym Semeniuk, and Olha Leliukh, who were visiting O. Meshko, were also searched;

April 12, 1979 – detention and search in Serpukhov near Moscow, while returning from a visit to Nina Strokata;

August 7, 1979 – search of Oksana Meshko, Vasyl Striltsiv, Mykhailo Lutsyk, and Stefania Petrash-Sichko at her home in Dolyna, Ivano-Frankivsk region;

August 8, 1979 – expulsion of O. Meshko from Lviv;

February 22, 1980 – search in the case of Hanna Mykhailenko;

March 12, 1979 – search;

June 13, 1980 – interrogation in the case of V. Stus and confinement to a psychiatric hospital for 75 days;

October 12, 1980 – last search;

October 13, 1980 – detention and confinement to a psychiatric hospital.

– Ed. Note).

The Group's materials, as I learned when I was abroad, did reach their addressees. The diaspora abroad published several volumes of these materials; they are preserved there, but there is no way to transport them here so that they can become known to our readers.* *(O. Ya. Meshko is referring to at least these publications: Ukrainskyi pravozakhysnyi rukh (The Ukrainian Human Rights Movement). Documents and Materials of the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords. Foreword by Andriy Zvarun. Compiled by Osyp Zinkevych. “Smoloskyp” Ukrainian Publishing House named after V. Symonenko. Toronto–Baltimore. 1978. 478 pp.; The Persecution of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. Human Rights Commission. World Congress of Free Ukrainians. Toronto. Canada. 1980. 66 pp.; Informatsiini biuleteni Ukrainskoi hromadskoi hrupy spryiannia vykonanniu helsinskykh uhod (Information Bulletins of the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords). Compiled by Osyp Zinkevych. Afterword by Nina Strokata. “Smoloskyp” Ukrainian Publishing House named after V. Symonenko. Toronto–Baltimore, 1981. 200 pp.; Ukrainska Helsinska Hrupa. 1978–1982. (The Ukrainian Helsinki Group. 1978-1982.) Documents and Materials. Compiled and edited by Osyp Zinkevych. “Smoloskyp” Ukrainian Publishing House named after V. Symonenko. Toronto–Baltimore. 1983. 998 pp. A collection of these documents has already been published in Ukraine: Ukrainska Hromadska Hrupa spryiannia vykonanniu Helsinskykh uhod: Dokumenty i materialy. V 4 tomakh. (Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords: Documents and Materials. In 4 volumes). Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; Compiled by Ye. Yu. Zakharov, V. V. Ovsiienko. Kharkiv: Folio, 2001. Total 794 pp. – Ed. Note).

V. Skrypka: Obviously, this didn't affect the Group's activities? Or did it, greatly?

O. Ya. Meshko: Imagine, the materials flowed in a continuous stream and were signed: “Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords. Attested. Meshko.” That is, I signed them as the secretary, while the members were already behind bars. There were people whose participation and work in the Group I was simply afraid to announce publicly, afraid to legalize. Such was Yuriy Lytvyn, and later Vasyl Stus. At one point, also Mykhailo Horyn, Zinoviy Krasivsky. There were also sympathizers—the late Mykhailo Melnyk. He took his own life... This figure must be remembered, it is a sin not to speak of him... He was a person who belonged to us with his whole soul, but fearing such a swift end as arrest, or perhaps he was not psychologically ready for it... He helped with various pieces of information. It was difficult to gather information about human rights violations. It required time and suitable conditions. He helped me a great deal on one condition—not to publicize his work.

On March 8, 1978, several of our sympathizers' homes were searched, people who visited me. And my home was under close surveillance: whoever came was noted down. The search on March 8 included Mykhailo Melnyk's home in Brovary. They confiscated a lot of material from him in 12 journals and a collection of his poetry. This was his creative work of several years. It was a chronicle of events that took place before his eyes. After the search, he understood that it would end in arrest, that all his work was lost, because there is no return from there. He took his own life at his home, in the cellar.* *(These searches of Mykhailo Melnyk took place on March 6 and 9, 1979, not 1978, in the village of Pohreby near Brovary. On the night of March 9, M. Melnyk took his own life, leaving a note saying he did not want to bring disaster upon his daughters and wife. – Ed.).

So, the price of our materials was very high. Yuriy Lytvyn and Vasyl Stus took part in writing them. Vasyl Stus took the most active part in the Group. While still in exile in Magadan, he, of course, knew about its emergence and its activities, understood and approved of it, and saw in it a healthy, rational core. From there, he wrote letters to his friends in Kyiv, asking them for help, chiding them for standing aside. Yes, he wrote a letter to Svitlana Kyrychenko, to Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, to friends from research institutes, to engineers and scientists. And when he returned home after his exile—no one joined the Group. But he took the most active part in it. First and foremost, he defended Yurko Badzio, traveling to Moscow with his wife, Svitlana Kyrychenko. This brought trouble upon himself from the KGB. He threw himself into it with such energy and zeal, as was characteristic of this maximalist.

I was very afraid for Vasyl because this was after the arrest of Yuriy Lytvyn.* *(August 6, 1979. – Ed.). So there was no doubt that a second term awaited him, and as a recidivist—15 years. 10 years of imprisonment and 5 of exile. And so it happened. He was arrested in May* *(May 14, 1980. – Ed.), after Yuriy Lytvyn. But Yuriy Lytvyn, who was at that time in a corrective labor camp (which they called an "institution") in Bucha near Kyiv—even from there he managed to establish contact, sending materials to Vasyl Stus. A part of it, in particular, his imaginary conversation with Brezhnev under the title “If God Does Not Exist, Everything Is Permitted”—it does exist abroad, it was published there.* *(See: Ukrainska Helsinska Hrupa. 1978–1982, pp. 394-404; Yuriy Lytvyn. Liubliu – znachyt zhyvu (I Love, Therefore I Live). Publicistic Works. Compiled by Anatoliy Rusnachenko. – Kyiv: Vydavnychyi dim “KM Academia,” 1999, pp. 81-87; Ukrainska Hromadska Hrupa spryiannia vykonanniu Helsinskykh uhod: Dokumenty i materialy. Vol. 4, pp. 95–100). There were other materials as well. I know that some of it got through, but not all, because Vasyl Stus had to burn it when he saw that the “tails” were following him closely and that an arrest or a search was inevitable. He was expecting the search, he was ready for the arrest. Vasyl Stus once told me: “Well, what of it—they'll arrest me and you—and that's it, there's no one left to pass the baton to.”

The pressure on me was terrible—probably precisely because they didn't want to arrest me. It was inconvenient; my age stood in the way. But it was absolutely necessary to stop me. The calculation was that a woman would be afraid. And one time—it was in 1978, sometime before the October holidays, maybe October 5th* *(November 3. – Ed.)—a man in a Soviet-style trench coat came to my door: “I'm here for Olha Yakovlevna.” I said there was no one here by that name. “I'm here to see you!” “But I'm not Olha Yakivna, I'm Oksana Yakivna.” “Then I'm here to see Oksana Yakovlevna.” “Where are you from?” “From Moscow.” I said: “Come in.” I thought: I should let him in, because it had happened before that people came to me from different cities. Maybe it's on some serious matter, I thought.

I invited him into the kitchen, and I myself wanted to get the keys to the room, which was locked. I had just reached the door when I suddenly felt him press his whole body against my back and grab my shoulder with a strong hand. With indignation—still with indignation, not yet with fear—I turned to him, and at that moment he pulled a Colt-system revolver from under his coat—a big one! black!—and pointed it straight at my stomach: “Money!” he whispered. I was silent for a moment. I was speechless, then I cried out: “Money?! Hah, it's the KGB! Because everyone knows I have no money. No one would come to me for money!” And I started to scream.

Luckily for me, my tenant—in the room opposite—heard, opened her door, and ran right into this man. So, the three of us got tangled up in a heap. I was half-turned towards him, he was pressing his stomach against me, and she was pressing against him. I shouted: “Tonya, we're being robbed!” She ran out and started screaming in the street. And in the moment he let go of my shoulder—the window in my room was open to the garden—I fluttered out like a bird, and he was left alone in the room. I ran out to get over to my neighbors. As you know, I have a private house surrounded by a low fence. I thought I would jump over the fence to the neighbors. I could have done it, but this fear, this terror, say what you will—a black Colt—it made its impression, because he could have, if not shot me, then hit me over the head. And I understood that they didn't come to play games with me, but to do me harm. Ultimately, they could have just scared me. I had recently had a heart attack; I could have had a stroke, another heart attack.

I was indeed frightened, but not so frightened as to not defend myself. I ran through the garden, couldn't jump over the fence, and ran into my summer kitchen. My other tenant had also run out into the street by then; they were both screaming there. And I locked the door, pressed myself against it—my heart was pounding... I could hear a baby crying in its cradle... It seemed I stood there for so long. It was quiet in the yard. When I finally opened the door and went out into the street, beyond the gate, my tenants were standing there, and two neighbors across the way. And my neighbor, a taxi driver, also did something amazing: he noted the number of the taxi the man had arrived in. It was a number from the Kyiv taxi fleet* *(17–97. – Ed.). It was purely professional memory. They saw him leave the house. He didn't take anything from me. Didn't touch anything. He got in the taxi and left.

I asked our neighbor to call the police. The police—well, it was as if a special department of the criminal investigation was on standby (that young man, Terpylov, knew who to call): it was like they were sitting there waiting for that call—they arrived instantly. When the car arrived and stopped by the gate, only one man came into the house* *(Inspector of the criminal investigation department of the Podilskyi District Police Department, Captain Dytiuk. – Ed.). And I had already gathered the neighbors in the house; I wouldn't let either of my tenants leave my side. I said: “Bring your driver in too—I'm afraid of you!” He laughed. I said: “Yes, yes, I'm afraid of you! I've just experienced such a fright that I don't trust you either. I don't know who you are—show me your identification!” “Well, now I have to show you my documents—you're asking for too much! Tell me what happened here.” When I started to tell him, he became interested: “And who do you live with?” I said: “Here are my tenants, and this is my neighbor.” “And who do you live with, who else lives here? What, you have no one?” “No, I have a son.” “And where is he?” “He's in prison, convicted.” “Ah-ha, so it must have been a friend of your son's.” “So, you're from that kind of criminal investigation department? On what grounds do you think it was a friend of my son? My son is not a convict, not a thief, not a robber. He was convicted for political reasons.”

In short, this man began to write a report that I didn't like. I demanded that I write it myself. Then he made corrections and said: “We will summon you.” I said: “No. Don't summon me, because I won't go anywhere—I'm afraid of all of you. Just inform me of the results.”

No one informed me of anything, and I understood that it was an attempt to scare me. Was I scared? Like all people, of course, I was scared, but I could no longer retreat—once the work was started, I could no longer abandon it. I saw that everyone was being arrested, and I was given a privilege—the privilege of my old age.

This didn't last long. When Vasyl Stus was arrested on May 5 (I believe it was May 5), the trial took place soon after.* *(V. Stus was arrested on May 14, and the trial took place from September 29 to October 2, 1980. O.M. was interrogated in the Stus case on June 13, 1980, and was forcibly committed to the Pavlov psychiatric hospital, where she was held for 75 days—until August 25. – Ed.). And two men came for me at home—one from the investigative bodies of the regional KGB, from Bereza's office. But he didn't show any documents, just said so, and our former district policeman. He wasn't even the district policeman at that time. But for some reason, the two of them came together. “We're going to an interrogation with investigator Bereza.” I asked for a summons—there was no summons. I said: “I won't go without a summons.” “We'll take you by force.” It was lunchtime. The street was quiet, empty. All the neighbors, of course, were at work. I was alone in the yard. Even my tenant wasn't home at that moment. I decided to go with them because I understood they would put me in the car by force. This had happened so many times that it was better to get into the car yourself than to be thrown in like a stone.

THE PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITAL

Well, we left. I looked: I know the way to the KGB building very well, but they turned in a different direction. They turned into the republican psychiatric hospital, to the admissions department. Here, for the first time, I was truly terrified. I know what a "psikhushka" is, I know how many people, arrested for political reasons, were put in psychiatric hospitals without a trial or investigation—and for good, with forced treatment...

They took me to the admissions office. The doctor asked for a referral from a psychiatrist. They didn't have one. She said: “Please leave and don't interfere with our work.” And to me: “You are free.” The psychiatrist was on top of her game—she immediately determined that this was a mentally healthy person and that this was coercion and an illegal act. But one of them left, and the other grabbed me and forcibly dragged me into the small room where they change the clothes of patients admitted for treatment. She was indignant, but in the meantime, she started admitting other patients. Someone called her on the phone. From the conversation, I understood it was about me and that she didn't want to admit me to the psychiatric hospital on the grounds that there was no referral, and this was a violation of the law, because in her opinion, there were no grounds for treating me. But someone on the phone forced her. She said for a long time: “Yes... Uh-huh... But... But there isn't... But... But...” And then she invited me to her office, and said to the policeman: “Get out of here! I will speak with the patient alone.”

She began to calm me down and said: “I will remind you of your right. I understand everything. This has happened here before. Here is your right: you must demand an examination within three days and your release.” “Doctor,” I replied, “don't you understand that they are forcibly putting me here and may even confirm that I am mentally ill.” “If you demand it, they won't confirm it!”

In short, this doctor was the first to take that step which is punished by human law, by God's law, and by the law of conscience, and in a state governed by the rule of law—by state law.

They changed my clothes into a hospital gown and large hospital shoes. Two orderlies took me to the third ward, where the head was Dr. Liuta.

They put me among the violent, among the seriously ill. There were three wards of them there. There were up to 60 people—the ward was terribly overcrowded. I stayed there for 60 days* *(From June 13 to August 25—75 days. – Ed.). But during this time, I wrote petitions, although, by the way, I was immediately placed under conditions different from those of other sick people. My packages were inspected, paper was taken from them, but the other patients had it. I wrote a petition-telegram to Brezhnev. And although I had no money, because money was also not allowed into the ward, some visitor took pity on me, took my telegram, and sent it as a letter. For his part, my son Serhiyenko, although he was in exile in Ayan, Khabarovsk Krai, also sent a petition to the legal authorities, to the prosecutor's office, and demanded that I be taken from the psychiatric hospital “for its intended purpose.” He understood, just as I did, that a punishment was already hanging over me, not yet determined by a court, but already assigned by the punitive organs. Therefore, he demanded that I be handed over to the KGB— “for its intended purpose.”* *(This is my mother's mistaken impression. Having learned from my wife, who came to visit me in exile during her vacation in June, that they were threatening to subject my mother to forced treatment, I, as a medical professional, sent a telegram to the head doctor of the Pavlov hospital, reminding him of the Hippocratic Oath and of the legal responsibility for the patient's health to their relatives. – Note by O. Serhiyenko).

I was assessed by a commission. Fortunately... I was assessed by Charochkina—a psychiatrist. She declared me sane and ordered my discharge. My doctor, Patorzhynska, even asked if I could go home now, if I had anything to wear. She rejoiced with me. She left. But then she was gone for a long time, and when she returned, her head was bowed in embarrassment as she told me: “We would have released you, but the KGB did not allow it.”

So, I remained there until the commission declared me mentally sound. They gave me the most thorough examinations—three research laboratories located in this republican hospital examined me. In one of the laboratories, I was examined twice: after the lab technician, the head of the laboratory examined me and, as if in exasperation or sympathy for me, I don't know why, exclaimed: “May God grant us all such health!”

V. Skrypka: Meaning, to feel that well?

O. Ya. Meshko: Yes, and then she said: “Don't worry, my laboratory is the last one, you have been declared mentally sound by all the laboratories, now everything will depend on you.”

So, the commission, headed by Charochkina and with a psychiatrist-lecturer from the medical institute, declared me sane, but the psychiatrist Verhun, the deputy head doctor for medical affairs, did not release me but transferred me to the lower floor into separate cabins, where recovering patients were kept, and began to blackmail me in this way: she would summon me and try to persuade me to do this: “I will release you, but on one condition: you will go... You live in the Podilskyi district? Well then, you will go to the Podilskyi district and register at the psychoneurological dispensary.” I said: “No, I will not put a noose around my own neck.” “But then you will stay here.” “Then I will stay here. But here I am by force, and there I would be admitting that I am ill. You know that I am not ill.” “But be objective, Oksana Yakivna! You are 75 years old. This is an age when a person, in terms of nerves... The wear and tear of the body, changes in the psyche...” “So what, are you trying to persuade me to admit it?” “Yes, this is your only salvation, because only in this way can you be freed.”

I refused. Ten days passed like this. Finally, on a Friday (August 25, 1980. – Ed.), she told me: “I will release you. Let's make a gentleman's agreement.” “In what way?” “You will come to see me—you know where my office building is. You will come to me on Monday. Today is Friday—you will come on Monday.” I thought: “And for what purpose?” “I want a good specialist to examine you.” “I don't want him to examine me.” “Well, then just stop by, we'll settle a few more questions.” I thought that if she said “stop by,” then I would already be coming from home. I agreed, I gave my word. She even cheered up, saying: “I know, your character reference is such that if you give your word, you will keep it.”

I went home. And on Monday, I came to see her.

V. Skrypka: Like a gentleman to a gentleman?

O. Ya. Meshko: I came to see her. I had just approached the building when she drove up in a car right next to it—swoosh! A man was sitting in the car, and she jumped out, as happy as if she'd met her own father, and said: “Good, please come to my office.” And she quickly led me away. I was still looking back, wanting to see who she had come with. But she let me go ahead—I didn't see.

We came to her office, sat down. She started persuading me again: “You don't want to go and register? Fine, but a doctor will examine you now.” “No, Dr. Verhun (Nelia Yakivna, I think is her name, I remember Nelia), no, I won't go in there with you. I don't want a doctor to examine me.” “No, a doctor will examine you.” I got angry and said: “In the 75 days of my stay in your psychiatric hospital, I have seen seriously mentally ill people whom you cannot help—and here you, such a doctor, have such a desire to make a sick person out of a healthy one? And where is your Hippocratic Oath?” I turned my back on her and ran out. She shouted after me, the phone was ringing—it was that impatient doctor behind the wall waiting to examine me. I ran out—the territory of this hospital is quite large, but I knew the layout of the buildings and started running. I thought: now two orderlies will catch me, and the same thing will happen all over again.

I ran like a madwoman, not knowing where to run. I remembered: Charochkina! Her teaching building is right here, for practical classes for students. I burst into that hall. She wasn't in the first hall. The second was her office. I ran there. To my luck, Larysa Charochkina was there. She looked at me and said: “What's wrong with you? Why are you so frightened?” I told her everything. She gave me some medicine to drink, warmed up some tea, put out some cakes, apples and said: “Now we will talk calmly. I'm so interested in getting to know you! Tell me about yourself.”

We talked for a very long time. I was in no hurry to leave her, because I was afraid that that hounding was waiting for me there. She reassured me: “I assure you that you will not end up in this hospital again, despite the efforts of our doctors. Forgive our doctors—they are also under duress.”* (These doctors should be named. On June 20, 1980, Prof. V. M. Bleikher and Dr. A. H. Koropova declared Oksana Meshko sane. After O. M.'s written complaint on August 7 to higher Soviet authorities, a consultation consisting of Deputy Head Doctor L. A. Charochkina, Head of Medical Affairs N. I. Verhun, Head of Department Ye. I. Yastreb, and Dr. A. M. Patorzhynska confirmed this diagnosis. In the 1990s, Nelia Ivanivna Verhun was a member of the Ukrainian Psychiatric Association, created by Semen Gluzman. Through her efforts, many victims of punitive Soviet psychiatry were rehabilitated. – Ed.).

We left. She walked me to the exit here, near St. Cyril's Church, down to the steps. She said goodbye to me and promised that she would not allow this to happen again. By the way, she gave me several addresses of doctors I was supposed to see. It was somewhere in Darnytsia, I can't remember now, some building.

Thus I did not end up in the hospital a second time. I understood that my time at liberty was very short. I sent a similar telegram to my son, and I myself was already prepared. In the meantime, I went to my grandson's school every day—he was in the first grade then. I was with him during the short breaks, and during the long break, I would take him with me, we would go to the park, the square, I would give him something to eat, talk to him. It was wonderful—a beautiful autumn. I will never forget it!

THE LAST SEARCH

And so, on October 12, 1980, they came to search my place. They conducted the search as they always did, checking everything—all the wardrobes, all the sofas and tables. They tapped the walls, the floor, the cellar, the attic, the summer kitchen. They dug and re-dug all the soil. I can't even count how many times it had been like that. But whatever they were looking for—they never found anything. They left late at night.

I opened all the windows of my house to air it out. I took a mop and poured water on the floors of my three rooms, I washed them. It was almost morning. I couldn't fall asleep. I was haunted by that terrible smell. These people smell particularly strong. A special smell from these men: whether it's tobacco, or stale alcohol breath, or whether they were morally decaying from within, but that smell constantly haunted me. I am not exaggerating—I am telling you about my subjective impression.

V. Skrypka: But it's true! There's the cloth of the uniforms, and the leather belts, and the offices, and maybe some internal emanations... Even their sweat could be specific. It's a function of their role. Maybe they have some malice in them, and malice produces a different kind of sweat than in a kind-hearted and good person. You are probably right.

O. Ya. Meshko: You see, it's not an invention. I have a very sharp, developed sense of smell. Since childhood. For flowers, for the air, for everything. I have been in concert halls, in crowded institutions, but I have never smelled such a smell anywhere else. These people have a specific smell. And I, tired from that search, that interrogation, that humiliation, that personal search, which I do not allow, by law! When they search a house, they must also have a warrant for a personal search. But they would come without a warrant for a personal search, bringing their female guards from the prison, they would forcibly strip me of everything, and I would scream. After such agitation, I would still take a mop, a bucket of water, wash the floor, and then lie down. I fell asleep a little only towards morning, having taken a sleeping pill.

ARREST

A knock on the door. It was October 13, 1980. I looked out the window—the KGB. I quickly got dressed, opened the door for them. Because I know so many of them at the Kyiv KGB—how many people have passed through my home! “Let's go to the KGB for an interrogation.” “But all this happened yesterday! Why today?” “They told us to bring you. But quickly, no time, the investigator is going somewhere...” I said: “He'll wait for me.”

I understood that my freedom had ended here. I gathered what is immediately necessary when a person finds themselves behind bars. This was the second time... As you know, I served 10 years during the Stalin era. They took me on the street, but they drove through the gate on Irynynska Street, which has a particular creaking music.* *(The entrance to the KGB building at 33 Volodymyrska Street is from Irynynska Street. – Ed.). A long dark tunnel. And it closes behind a person forever. I knew this was threatening me now. I started looking for the most necessary things. But that same executioner followed me and said: “Why do you need that? What underwear? What do you need? We'll bring you back, well, maybe in an hour, two, no more.” “Don't bother me, give me a chance to take what's necessary.” I took a small book, gathered my glasses, toothbrush, a small towel, a change of underwear, locked the windows, the doors, and left.

I never returned here.

I came to the office of my investigator, Seliuk. This was the investigator who had conducted Vasyl Stus's investigation. This was the investigator whom Vasyl Stus complained about in court, saying he had been tortured in prison.

I entered the office and saw the prosecutor. I knew him—he was armless. Oh my God, I can't remember his name right now...* *(In O. Meshko's verdict, the prosecutor is listed as V. P. Pohorily. – Ed.). He introduced himself. But I already knew him. I addressed him with a protest, with these words: “First of all, taking this opportunity, I declare a protest to the prosecutor as a member of the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords against the torture to which Vasyl Stus was subjected, about which he declared in court in the presence of his witnesses—Kotsiubynska and others.”

The prosecutor flinched and glanced at Seliuk.

“That is the first protest. The second protest—I, being a mentally sound person, spent 75 days in a psychiatric hospital. I was released as mentally sound, but no one apologized. And this was done with the permission or at the behest, more precisely, under the pressure of the KGB. They took me supposedly for an interrogation with investigator Bereza at the regional KGB department, but they brought me to a psychiatric hospital. In violation of all laws—they committed me by force. This is my second protest.

And the third: I demand an audience with the head of the republican KGB, Fedorchuk. I will not speak. Only after the audience, depending on what the two of us decide.”

Seliuk denied that Vasyl Stus was tortured within the walls of the closed KGB prison at 33 Korolenka Street, that is, on Volodymyrska Street. He also denied that there was such an investigator as Bereza in the regional department. It was a lie. Both the first and the second. And the prosecutor accepted this as Seliuk's justification and my slander against a decent investigator. As for my audience with Fedorchuk, Seliuk laughed sarcastically and said: “As if he has time to talk with you!” “Then I,” I said, “will not talk with you—this is my prerequisite for starting any conversation with you.”

While these conversations were going on, the prosecutor was nervously looking at his watch, and then he turned to Seliuk: “Forgive me, I'm already late: the store is closing, and my wife is diabetic, I need to buy her some diabetic bread.” I was indignant: “And are you aware that I am also a diabetic, and you are keeping me here for so long? I demand to be released from here. You are leaving—and I will leave too.” “Oh, no. You still have to finish your conversation with Seliuk, and I'm already leaving. Goodbye.” He said this so cordially to Seliuk and nodded at me. He left.

FORENSIC-MEDICAL EXAMINATION

As soon as the prosecutor left, Seliuk immediately changed his benevolent expression, went, opened the door of his safe, and took out a piece of paper. He gave it to me to read: the republican prosecutor Hluk—he is already in his grave, younger and healthier than me, probably, but gone earlier—had signed an order to commit me for a forensic-medical examination. I was outraged: “But just two weeks* (months. – Ed.) ago, I had an examination, I passed a commission as a mentally sound person, that is, as sane! Why do you want to subject me to such abuse again? To my human personality, to my dignity! Why are you destroying my health?” “We're going. Let's go, get ready without long conversations.”

We got into the car. And three more thugs, healthy men, with a fourth as the driver, drove me in that long, rattling car that all other cars make way for when it's on the road. I don't know, it must have some name.