Audio recording of the author’s reading

Excerpts from the book *Dissident Chronicles from a Head-chopper*, which was released by the Smoloskyp publishing house in 2003, and an interview with his mother **Hanna SAPELYAK** in the village of Rosokhach, April 2, 2000.

The herd’s contempt and the cries of “Crucify Him!” attacked me quite unexpectedly. I felt the sad approach of evil, of the dead zone into which my friends, both young and much older, were disappearing. Still safe, I searched within myself for the strength to flare up, to find the trail of a guide at the tangled crossroads of despair. And suddenly, the element of my father’s creed, the “I Believe,” triumphed within me.

My father, born in pre-Soviet Poland, a native of Przemyśl, a Ukrainian Lemko, could in no way accept a unified value system or aggressive atheism. A worthy Greek Catholic, he saved me with his bitter lesson, extending a hand to lead me to Communion, where, in the church, my grandmother and mother, from the “upper place” in the choir, would begin the very first Word of the liturgy. My mother Hanna and grandmother Nastia from the Ternopil region, traditional Greek Catholics, always shone with conscientious piety, entirely unaccustomed to living improperly. It was from them, ultimately, that I learned to stand before the icon of God, having taken off my kersey boots and cap; from them, I first “correctly” pronounced the words of the “Our Father.” The image of Easter bells still haunts my dreams. (...)

Fate chooses my destiny, and I demonstrate the path “for the purpose of subversion,” the path of voice and will. Symbolically, on January 22, 1973, along with eight other brothers-in-arms, on the day of the Fourth Universal and the proclamation of the Sobornist of Ukraine—the Unification Day—I hung four national yellow-and-blue flags and nineteen leaflets with calls for freedom for political prisoners, for rallies, and a manifesto against the total Russification of Ukraine.

...There were four of them. A scent of “Lilac” cologne filled the air. As if it were a premonition. My eyes grew dim. My body turned to wood. Their footsteps fell silent. The road of life was cut short. Paralysis of mind and body. Some wretched words—life was already carrying me through a Kafkaesque gallery of sacrifice and hopelessness. I could not comprehend the word “future.” As I came to my senses, the first thing I felt was a small bundle in my hands. No, not handcuffs, not voices, not a guard who was already holding the laces from my boots and the belt from my pants, but a bundle with a cup, a toothbrush, and a piece of soap. I didn't let go of it. I clung to it like a blade of grass, like the last privilege of life. The last of my strength, or perhaps just the instinct for self-preservation, was awakening in anxiety. The dark cell aimed its dim, mysterious, and indecipherable eye of reproach at me, and maybe even of hell. That was it. It had happened. The captors, dressed in festive attire, they were the kings of this conspiratorial basement, this vile trough, vampires of the grated sky of the prison yard. “...And deliver us from temptation,” I finished, my heart trembling as if it had been torn out. In the tremor of a significant world. Like a constant motive, an engine, the interrogations began, a crumpled shimmering of rage, omitted words, illustrations of “world problems,” and vague names that would have fit perfectly into a wonderful work about my duel with “barbed-wire literary criticism.” As an example, I’ll describe one of the first, yet typical, cases of the originality and falsified criminal nature of an interrogation by a major of the Ternopil UKGB, senior investigator Lokha.

“Citizen Sapelyak, here I have the Moscow newspaper ‘Izvestia.’ In your opinion, is it an interesting newspaper?”

“Yes.”

“I have a lot of paperwork here, so in the meantime, you read the newspaper. Pay particular attention to the article ‘America: A Way of Life or Propaganda of an Economic System.’ It seems interesting to me.”

I take the paper, look through it, and read everything, since time is unlimited. The article the investigator major had so unobtrusively and courteously offered me was an overview, genuinely interesting and unusual in its analytical depth and content. After reading, I feel bored. Finally, the investigator takes the newspaper from my lap.

“So, what did you think of the article?”

“It was very interesting, from both an economic and a journalistic point of view.”

“What specifically?”

“It seems there’s more objectivity regarding the material life of Americans, their high standard of living, and so on.”

“Hmm... Interesting. Yes, yes, you’ve read it well... Very clever. You are a clever man, citizen Sapelyak.”

The dialogue ended there. But I see the investigator began writing at length. One page, two... At last, he approaches my small table in the corner and says:

“Sign this,” and he hands me the text to read.

I read: in a conversation with investigator Lokha, I attempted to convince the investigator of the superiority of the capitalist system over the socialist one, thereby causing the investigator’s outrage and astonishment, and so forth.

Thus, another charge was added to the indictment against me.

The nearly ten-year sentence* (*5 years of imprisonment and 3 years of exile. —Ed.*), handed down behind the closed doors of prisons, concentration camps, and exile in the fall of 1973, I, of course, perceived as a fraudulent political hypocrisy that finally alienated me from any possible reconciliation with the communist delusion.

On a dreary, anxious December night in 1973, I had a dream. I saw an image of the Most Pure Mother, but she was deeply, deeply sorrowful. I fell to my knees and whispered something, pleading, yet doubting my own request, thinking, what right do I have to ask when the image of the Mother of God is so sorrowful. I stand before her and weep bitterly: what am I to do, whom can I ask to intercede for me? I try to stand, but kersey boots of some huge size—heavy, so heavy—buckle my legs with every attempt. I fall again, barely alive. And in this mournful despair, I vividly see a clear sky. In my dream, I continue my prayer...

The barking of a ferocious sheepdog woke me. A total search of the cell and the guards’ arbitrariness began. I came to my senses. This was already the transport to Siberia. A strained voice of a guard continued:

“Article... term... last name...”

Weakened, thrown to curses and the barrels of assault rifles, I humbly followed all the commands of the enraged guards. The one “true” meat grinder started to turn, humiliated, and renounced the “thirsty” one...

Ідуть етапи чорним ходом,

А білим ходом – снігопад.

Моїх небес німує попіл

Над барикадами ридань.

Останніх днів посмертні стріли

У смертнім мареві стримлять.

Блищали нари, як офіри –

Розп'яті на семи вітрах.

...In the Perm prison, I was kept alone. In a cell where a violent clash between criminals had recently taken place. The walls, plastered decades earlier, were soaked through with bloodletting from the inmates’ blood—as a protest against the regime. In the cracks between the floorboards and in the ceiling, millions of crimson-red bedbugs had settled. I was brought to the cell from the transport at half-past two in the dark dawn. Darkness. Maybe something gleamed a few centimeters from the ceiling. Hungry and exhausted from the long transport and the hounding of sheepdogs, I immediately climbed onto the top bunk. I was afraid of the bottom one, because I knew from experience on transports that mentally ill inmates, completely deranged, slept under the bunks. They could attack quietly and cunningly, and cripple me. As soon as I rested my head on the sleeve of my pea coat on the top bunk, I immediately fell into the abyss of sleep. But a few minutes or perhaps an hour later, I don’t know, I awoke from painful bites on my face. It felt as if someone were scalping me with a blunt object. The first thing I did was grab my eyes with both hands: they were burning intensely. I consciously tried to force them open. It was impossible. I had no strength, as I hadn't slept for more than three days, except while standing. Finally, it felt as if something was dripping into my hands. It turned out that with force I had managed to wipe a swarm of bedbugs from my right cheek. My entire body burned and was slick with blood. My mind was going mad. Consciousness was failing. Something insane buckled my legs. I lost consciousness.

I came to, feeling savage and as if my body were made of metal. No longer in the cell, but in the isolation ward for tuberculosis patients. Someone in a white coat, but a military man, was sitting on a stool. He introduced himself as the operative captain of this prison. Immediately, another man in civilian clothes entered. A brief, ritualistic conversation followed. They informed me that in a few days, I would be transported to the camp. And at the first opportunity, I would be transferred to the Skalninsky (...) camp administration as per my court sentence.

Another eight days passed. Every day I wrote complaints to the prosecutor’s office of Perm, to the department of internal affairs, screaming with an inhuman voice about the prison routine, the evil of this “black hole” of a prison, but the answer was always: “Wait. It is not permitted.”

And in this breathless role, amid this wild, battered silence, I heard the jangling of the herd-keepers’ keys. Three men entered the cell. They led me out “with my belongings.” The “shmonshchyky”—the searchers—“went to work.” In the semi-darkness, a KGB officer from Perm delivered a monologue: “You will be met in the zone by ‘otpeytiye nizkoprobniye, makhroviye antisovetchiki’ [incorrigible, low-grade, dyed-in-the-wool anti-Soviets]. Don’t get involved with them.” Two sheepdogs began to howl. The camp convoy approached. “A step to the left, a step to the right—we shoot to kill”—the last shouts in this gallery of death of the Perm transit prison. The “voronok,” like Cerberus, raged along the Siberian road at the foot of the Urals* (*Perm Oblast is still on this side of the Urals, not in Siberia. —Ed.*), only tears fell on the frozen shoulder of the rough, blackened snow. Only the aluminum cup, which the criminal murderers had swapped for mine, and a spoon, tinkled over my convulsive muteness.

У марнотах доби моє зірване слово.

Алюмінійна креш від щоночних утрат.

Україно моя. Ой сніги ж ці солоні...

Ой снігото солона, – на той світ етап.

Лине кров до колючки в кривавій вуглині,

Рідна мамцю моя. Пересохли вуста...

Я у смерті в гостях...

The sheepdogs whined. An anniversary-like silence surrounded us. Here it was, my bright future: My City of Urallag. And the Ural jackals howled in that moment.

And here—the zone! An island of “red lawlessness” and “blacklists.” A great advantage and a holiday on this somewhat arduous path seemed to be the “unauthorized” clear December sky with a dazzling sun. Essentially, I could gaze at the color of the sky without any “prohibited” instructions. Instantly, my heart flared up with life. Hold on—with all my strength. And the sky, like an icon—I was afraid that it would disappear from me at any moment, for in its heights lay a mystery, the divine sanctity of the Psalms of my destiny. The Communion of my soul. “I believe,” I whispered. “I believe!” And the convoy: “Faster, faster, citizen-convict!”

At the guardhouse, I was issued a black-and-gray, mournful prisoner’s “uniform” and a tag-patch with my last name and the number of an “especially dangerous state criminal.”* (*The ‘tag’ displayed the last name, initials, and the numbers of the ‘detachment’ and brigade. Numbered patches were abolished in 1954. —Ed.*) So, “with my belongings” (a bundle with a cup and a spoon), I was released from the sanitation block into the zone (institution VS-389/36). (...)

Of course, there were certain traditions and procedures for receiving a newly arrived political prisoner in the political zone. The closest fellow countrymen introduced themselves first. Others, as a rule, collected dry rations, since the transport exhausted one’s being to such an extent that there was no physical strength left to walk. True, a year of the investigative process and humiliation also took a toll on one’s physical condition. So, the first to come to my barrack were Bohdan Chornomaz from Ternopil and Oles Serhienko from Kyiv. Both were former instructors at pedagogical institutions. They gave me a little butter and a glass of sugar. Sugar, by the way, was “not permitted” in the zone—several tuberculosis patients gave it to me from their medicinal diet. Anatoliy Zdorovyi from Kharkiv gave me something to eat. Half a day later, my older countrymen came to get acquainted. Pavlo Strotsen—a twenty-five-year hard labor convict who had already served 20 years, and Viktor Solodkyi, who had a 30-year sentence. He had already served 27 of them for participating in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. Ivan Pokrovskyi—30 years of imprisonment. Twenty-five plus an escape. Yevhen Pryshliak—25 years. Head of the “Karpaty” Security Service. (...) Dmytro Paliychuk, Bohdan Chuyko, Fedyuk—these were prisoners of honor, defiance, and self-respect, who were already crossed off the list of the living. All they had to look forward to was physical annihilation “by shooting.” So, these people immediately responded to my further existence. They gave me a positive charge, sympathy, and mercy, as I was practically the youngest by age in the concentration camp. On March 26 (1974), I turned 22. ...)

One day, when I had already gone out to the so-called “promzona,” or industrial zone—the camp was divided into two separate territories: the barracks where the prisoners lived and “rested,” and where they performed their forced-labor drudgery—a tall intellectual, a “twenty-fiver,” a former member of the armed resistance to the Soviet regime and of many acts of defiance in the camps of Taishet, Irkutsk, and Murmansk, Hryhoriy Herchak, approached me to introduce himself. It turned out we were from very close hometowns. Herchak was from a neighboring village. In the zone, he was a respected political prisoner who consciously cultivated the art of beauty. He secretly carved ex-librises, sketched portraits of prisoners, and studied languages. We immediately became friends. He was a devout Catholic, which nourished my feelings with the domestic comfort of my childhood. Hryhoriy had a noble, peaceful nature. He knew how to respect people in the camp. In the past, he had been imprisoned with great people, particularly priests. He told me a lot about his close relationship with Patriarch Josyf Slipyj. Of course, this brought me back, saved the principles of honor before God’s Law. Such examples inspired resistance to the concentration camp routine. (...)

On June 23–25, 1974, in camp No. 36, where I was still being held, perhaps the largest strike in Urallag began. The reason for these disturbances and defiance by the political prisoners was the sadistic and vengeful beating I received from the officer on duty, Captain Galedin, and his squad at the zone’s checkpoint. The situation had essentially been escalating in the following way.

In the camp (...) there was a secret Resistance Movement. It included Ivan Svitlychny, Ihor Kalynets, Levko Lukianenko, Valeriy Marchenko, Gunars Astra, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Yevhen Pryshliak, and Yosef Mendelevich. I was also involved. Practically everyone had their own covert function to perform. This was especially true for the camp’s *Chronicle*, which was written daily by active prisoners. Under certain circumstances, the chronicle of events could be passed on to the outside. Thus, everyone involved in this chronicle-writing activity had their assignment. I was supposed to carry several meters of narrow transformer paper from the work zone to the living quarters, sometimes vice versa. The *Chronicle* was written on this paper. It goes without saying that other prisoners smuggled in pens, liquid (there was no ink), and so on, in a similar way. Each member of the Resistance Movement had their tasks.

So, on that day, the column of political prisoners lined up, as always, “by rank.” The officer leading the column to work, suddenly near the checkpoint, commanded: “Count off!” And he clearly gave the order: “Every third man” was to go to the checkpoint and strip for a “shmon,” that is, a personal search. I managed to tear off my “cache” of transformer paper from the heel of my kersey boot (this had been planned) and hand it to prisoner number two next to me, who was not subject to the search. Somehow, this was noticed by the guards, Warrant Officer Rotenko and Senior Sergeant Sharinov. Using physical force, they dragged me out of the prisoner column and took me to the guardhouse, supposedly to write a report. But what awaited me was inevitable physical punishment. They beat me however they could, wherever they could. The beating only stopped because of the mutiny of the prisoner column, which turned back, refusing to do their daily forced labor and meet their quota.

An hour later, other barracks and the shift that had just returned from the industrial zone joined the strike uprising. A strike committee was instantly self-organized in my defense. It included one representative from all the political and regional groups in the camp. This took the zone administration by surprise. For some time, it was quiet. They were waiting for instructions from the USSR GULAG. The political prisoners took advantage of the temporary lull. Everyone knew that a physical and moral crackdown, possibly even shootings, was imminent (on the watchtowers, the guards’ assault rifles were replaced with machine guns). The committee drafted a memorandum and demands for an investigation into the incident. They also demanded that all prisoners henceforth be treated with the status of political prisoners. The petitions were immediately sent to the camp leadership. Of course, I was immediately isolated, and a medical examination revealed severe physical injuries, especially to my liver and kidneys. The flesh on my back was a bloody black.

Several days of negotiations between the administration and the strike committee led to nothing. Instead, camp arrests began, isolating activist prisoners, especially from the Committee. L. Lukianenko, S. Kudirka—a Lithuanian, D. Chornohlaz—a Jew, G. Davidov—a Russian are taken away for transport. All of them, with the exception of two or three, are transferred to the Vladimir Prison facility (...). As for me, as soon as things settled down, I am convoyed to Kazan Prison and held in a solitary confinement cell for “death-row inmates”...

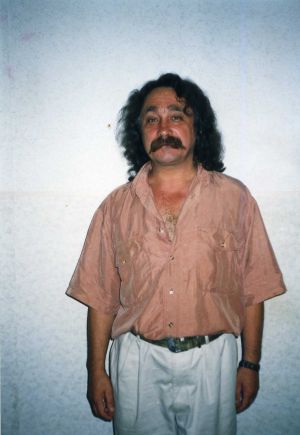

Hanna SAPELYAK

in the village of Rosokhach, April 2, 2000.

Volodymyr Marmus present

V. Ovsienko: Hanna Kostyantynivna, please tell us what you know about the events of 1973, when your son Stepan was arrested and put on trial.

H. K. Sapelyak: He never said anything at home, like: “Mom, I’m thinking about this and that.” Suddenly* (*February 19, 1973. —V.O.*) the KGB came to our house. We didn't know anything, we couldn't even imagine they had come for him. We thought they were from the military enlistment office. They sat down in the armchairs, one opened a folder and said: “I am a senior investigator for the Ternopil Oblast, my name is Lokha. Allow me to conduct a search of your home for anti-Soviet leaflets and literature.”

V. Ovsienko: And he showed you a search warrant?

H. K. Sapelyak: That's what he said—but what did we understand of his warrant? And the rest of them just sat there and listened. There were maybe 15 of them then. My husband and I ask, “What is all this? Because we don't know what.” —“Well, things like—maybe you have some manuscripts or books hidden somewhere? Maybe you have some pistols hidden?” And I say, “Why would we have books and manuscripts hidden? What kind of manuscripts would they be?” —“Well, maybe some notebooks are hidden somewhere?” —“And why would we hide them? We have a lot of notebooks, but we never hid them and we don't.” —“And where is your son?” —“My son is in Lviv.” —“And what is he doing there?” —“He works as a lab assistant at a college.” —“Well, since you don't want to hand over his notebooks...” —“But we will, they’re all in the attic, we can bring them down to the house.” —“And do you have a lot of books?” —“A lot.” —“And how many exactly?” —“I don't know, maybe 250, maybe 300.” —“And why do you have so many books?” —“Because my son was preparing to apply for university, he applied once in Ivano-Frankivsk and didn't get in, wanted to try a second time. He was studying and had those books. We can give you the books.” —“No, not the ones in the attic, we want the ones that are hidden.” —“We don't have any hidden ones.” —“Well, then we will look for them.”

They split up—two to that room, two to this room, two over there, starting from the icons down to the floor. This one in one room, and another in another, and with each of them was a witness—women from the village council. There was your sister, Volodymyr, Hania...

V. Ovsienko: They are called attesting witnesses.

H. K. Sapelyak: Yes, attesting witnesses. And the others climbed up to the attic and started bringing things down into the house. They used a magnifying glass on anything that was underlined in a book. And when they went for lunch, they left the books. And they did this for a whole month. And they told us not to take the books out of the house.

V. Ovsienko: What, they didn't finish the search that day and kept coming back?

H. K. Sapelyak: They finished the search, but then they continued to go through the books.

V. Ovsienko: Did they draw up a search protocol and take anything?

H. K. Sapelyak: No, they didn't take anything, they left everything here. They put some books aside, and left the rest in a pile and told us not to move them anywhere and not to leave the house, because they would be coming back. They came like that for a whole month. They were reading, but for a week they didn't tell us that Stepan was arrested. We kept asking them what was going on, why they were looking so hard through the books—maybe our son robbed a bookstore and was arrested for that? They said, no, not yet. No meant no. But my husband said he had to go to Lviv and find out where he was. Maybe they took him? So my husband went to Lviv, and they came here every day.

And another one came to see them on a Sunday with the secretary of the village council (Dudnyk was the village council secretary then) and said he was from the State Insurance and wanted to check on what we planned to build and what cow we had for sale. We showed him—here’s the cow, and here are the bricks, we want to add on to the house in that direction. But then they left on Sunday, and Stepan, as we later found out, was arrested the next day, February 19, 1973. But they told us he wasn’t.

Then my husband went to Lviv and asked there at the pedagogical college. They said he wasn't there, that he had gone home on Saturday and hadn't returned. That’s what the director of the college said. But he had left home for Lviv on Sunday, and they must have nabbed him somewhere along the way. He had a ticket for Lviv, and they caught him on the road. What he had with him, I don't know, but later they gave back his shoelaces and towels.

My husband comes back home, and they arrived again and one of them, Maltsev, the head of the Chortkiv KGB, started writing (the main office was in Ternopil, but a few men were in Chortkiv): “Well, Stakh?” My husband’s name was Stakh. My husband says, “Well, he's not in Lviv!” —“He's with us.” And I ask, “Where with you?” —“In Ternopil.” Well, then we knew that Stepan was in custody. But the next day I say to my husband, we have to go find him. I think, I’ll go over to their KGB office (in Chortkiv), ask what street, because I don't know where to look—Ternopil is a big city. I go and ask him where Stepan is located, on what street. And he says: “I don’t know where he is—whether he's in Ternopil, or with you, or in Lviv. And don’t you go anywhere, and don’t you look for anyone!”

But I didn't pay any attention to that and went. And that Lokha had said he was the investigator, and if we needed anything, we should contact him. I arrived in Ternopil and thought he was at the militsiya, I didn't know there was such a thing as the KGB administration. I searched the militsiya stations, went to all the precincts. And they all said he wasn’t there. And I wasn’t asking for my son, I was asking for that Lokha, because he said to contact him. He was nowhere to be found, until one man from the militsiya told me that it wasn't the militsiya, if Lokha summoned us—it would be at the KGB. I asked where that KGB was. He said it’s where the main post office is, that's where the administration is, and I should ask for him there.

I went in there, and they told me there was such an investigator. Then I said I was from Chortkiv, gave my last name and said I was looking for my son. And they said that Lokha would be right there. But it wasn't him who came, it was the head of the prison regime. He came and asked, “Who are you looking for?” —“Stepan Sapelyak.” —“Come this way.” I went with them. They say, “He's with us. He is under arrest.” I ask what he was arrested for. “He went against the authorities.” —“But he’s young, he served in the army,”—because back then they used to say that only those who didn’t serve in the army went against the authorities.—“He just came back from the army.” He had just returned from the army in the spring, and he was arrested on February 19. They say: “He went against the authorities and will be imprisoned. And what do you want from him?” —“I wanted to know where he is, and I want to give him something. Because I didn’t know he was in prison. And what did he do?” They repeated again that he went against the authorities. And they say: “Go buy him an undershirt and some food, whatever you have to buy. Do you have money?” —“Yes, I do.” —“Then buy him some onions, bread, half a kilogram of sugar, half a kilogram of sausage. Come back to us, we’ll give it to him.”

I went and bought it, and they took it from me. I couldn’t believe he was there—I thought they were probably fooling me. But his signature was there, and I recognized it, so I knew he was there.

He was arrested on February 19, and the trial was on September 18 of the same year. It lasted 8 days.

V. Ovsienko: Did they give you any visits during the investigation?

H. K. Sapelyak: No. I asked, but they wouldn’t let me.

V. Ovsienko: And there were no messages, no letters?

H. K. Sapelyak: Nothing at all.

V. Ovsienko: And you probably went every month to bring him packages?

H. K. Sapelyak: Yes, I brought him packages. Volodymyr's mother and I went together.

Volodymyr Marmus: After that arrest and search, you came to me and said there was a search and they took some things, some books were there... They took a notebook and some commentaries...

H. K. Sapelyak: Yes, yes, they took a few books. They took something that was underlined. I was in no state to remember, both my husband and I were just...

V. Marmus: And on the 24th, they came to my house and started a search.

H. K. Sapelyak: How we survived it, I can’t tell anyone, and maybe no one can understand me. It was a time when we were at each other’s throats. We were waiting, if not tomorrow then the day after, to be taken to Siberia from this little house we had built with our own ten fingers. We thought, how can we go to Siberia in winter with a small child, because he was arrested in February. It was only three months later, when I went to the lawyer Katsnelson, that I asked him: “I came to you with a request. My son was arrested for politics,”—because by then I knew it was under such and such an article, because Lokha had said so.—“I don’t know if we’ll be deported from our home or not. Because they used to deport people, I remember.” And he says: “Let me look in the Code right now.” He looked and says, “No.” And I say: “No? Maybe you're just tricking me? Because you think we’ll run away somewhere—no, we won’t run anywhere, we’ll wait. If they deport us, they deport us, we won’t run, but at least tell us so we can be ready.” And he says: “I’ll explain why not. They deported people whose sons were in hiding, and the parents said they didn't have any sons, but were secretly feeding them. That’s why the parents were deported. But in your case, you might not even have known what your son was up to?” I say: “No, we didn't know. My son never told me anything. We didn’t even know when he was arrested.” He says: “So they won’t deport you.” And I ask: “So at least tell me, because people are saying all sorts of things, maybe it will be a firing squad? Tell me, what's the worst that can happen for this? Here’s Article 62 and 64. What's the maximum for that article?” And he says: “Who told you about that article?” —“Investigator Lokha.” And he says: “Let me look it up right now.” He looked in that Code again and said: “The maximum is 12 years. But it depends on how he behaves at the trial. If he pleads guilty at the trial, they'll give him less, but if he stands his ground, they'll give him more. But they won’t deport you anywhere.” I learned this after three months.

After that, that Katsnelson represented him in court. He was about as useful there as a hole in a bridge, but what could we do? What good did his representation do? He was just trying to get words out of him. He would come out into the courtyard, that Katsnelson, and I’d go up to him, running after him: “Tell me, what’s going on, how are things?” And he, angrily: “He's not pleading guilty! I have no idea what’s going to happen!”

V. Ovsienko: And tell me about the trial—were you at the trial the whole time?

H. K. Sapelyak: They wouldn't let us into the trial. It was a closed trial. We would come and see them jumping out of the car. But they wouldn't let us in and said the verdict wouldn't be read. The trial went on for eight days, but they said the verdict wouldn't be announced. Every day they chased us away and didn't let us in.

V. Ovsienko: And how did you find out when the trial would be?