April 4, 2000, Borshchiv, Ternopil Oblast, with Volodymyr Marmus and Ihor Kravchuk present

V. Senkiv: I am Volodymyr Yosafatovych Senkiv, born on June 26, 1954, in the village of Rosokhach, Chortkiv Raion, Ternopil Oblast. My parents are Yosafat Ihnatovych Senkiv and Kateryna Levkivna Hadzhala. There were five of us in the family. My older sister’s name is Maria, then there’s me, Volodymyr, followed by my brother Ivan, who is now a dean, a priest, studying in Poland. My younger sister Vira works in Chortkiv, and the youngest lives in Ternopil. My father is from Rosokhach himself, he lived in the village almost his whole life. During the war, he was taken to Germany for forced labor and, I believe, was conscripted into the army there. And my mother was at home. My father was born in 1927, my mother in 1930. They live in Rosokhach, on a pension.

I started school after I turned seven. I finished 8 grades, then went to a rural vocational school to become a driver. After that, I was at home. Before the army, I became closer friends with Volodymyr Vasyliovych Marmus. In the fall, our sisters would go to school together, and we would herd the cows out to pasture. He loved to study history, and I loved to read books. And so we thought, let’s find some boys and create a small organization, and we’ll fight for Ukraine, for justice.

V. Ovsienko: What influenced you to come together like this—did you read the same literature, or listen to Radio Liberty?

V. Senkiv: I listened to the radio, and my father is a nationalist—he’s from that old generation of people who really love to read books, who love Ukraine. He's still like that to this day. At the trial, they said, like father, like son.

V. Ovsienko: Perhaps he was involved in the national liberation struggle?

V. Senkiv: No, my father was not directly involved, but his sister Maria was a liaison for the UPA. She still lives with my father. She had three or four territories, she maintained contact, and helped our Ukrainian Insurgent Army during the Bolshevik times. His brother Volodymyr died at the front.

V. Ovsienko: So your father told you about this?

V. Senkiv: My father didn’t tell me, because I was young. But I guessed, I later found a hiding place (kryivka) on our property. There was a stable, and in the stable was a passage to a kryivka for the winter. So I guessed what was there. We lived right by the forest. So the family was one that helped in whatever way they could. It’s true, I didn’t know it then, but later I slowly started figuring it out myself, they told me some things, I heard that my parents were honest, just people.

V. Marmus: Let me add. Our group also included Volodymyr Semanyshyn, who went by the name Sirko Latsko. He later got married and stayed behind, but he was aware of all our affairs. We often used his tape recorder for our recordings. We would even record a speech ourselves and circulate it among the young people. So Semanyshyn was involved in the organization.

V. Senkiv: Yes, I was younger. But Volodymyr Marmus and I were the first to agree on the organization. There were two of us. Then Volodymyr says: “I have a boy, you find another boy—and there will be four of us.” I had a friend, Petro Mykolayovych Vynnychuk, from my year, we went to school together. And Volodymyr Marmus had a friend, younger it’s true, but a fine lad—Petro Vitiv, known in the village as Hordiichyn. So we gathered, got to know each other well. We said that we would have to take an oath. Volodymyr Marmus wrote the oath, such a fine oath he wrote! I don’t remember the words very well, but I know that we swore to fight against the communists, for an independent Ukraine, and if I were to betray... Well, as it is written, may God punish me. It was written on one page and a little more. It was well written, very thoughtful.

The oath was taken like this: one person read, and everyone repeated. When we were in a clearing in the forest, at night, we lit a fire there, brought candles. I even took some icons from my father's sister to hang on a pine tree. It was done as it should be, solemnly. We took the oath there, and we already had a small organization. You know, when you have an organization, you don't misbehave anymore, people try to be honest, upstanding.

V. Ovsienko: When did you take the oath?

V. Senkiv: I don’t remember exactly, but I know it was in the fall.

V. Marmus: I think it was on St. Demetrius’ Day, November 8, 1972.* (*According to the verdict—November 5. —V.O.*) Right after the October holidays, we went and tore down the flags in the village.* (*On that very same day, November 5. —V.O.*)

V. Senkiv: That was our first combat mission—we had to take down those red flags in the village. Vynnychuk and I did it.

And before that, there was another mission. We had a grave mound for the Sich Riflemen, erected in 1941. Nearby, the military was taking rock for an airfield, so our party officials asked them to bring a bulldozer to level the mound.

V. Marmus: It happened right before my eyes. We don't know who told them to do it, but it wasn't a simple demolition—it was a demolition combined with a search. They thought there would be a bottle inside with a list of all the people who built it. Because after every pass of the bulldozer, the secretary of the collective farm’s party organization, Berehulia, ran and searched. But all that was visible was some rotten wood, the remains of a cross.

V. Senkiv: They leveled the entire mound, and in the village they had built a monument of a soldier with a rifle in his hand. We consulted and decided to vandalize it—they leveled our mound, so we'll damage theirs. It was strong, made of cement, reinforced concrete. But we damaged it a little.

V. Marmus: They vandalized it—they chipped off his nose, his helmet.* (*This was in late October 1972. —V.O.*)

V. Senkiv: Soon after, I was drafted into the army, around December 5th or 7th, 1972. I served for six months near Kyiv, in Vasylkiv, in an airfield company, worked on a vehicle. I received a letter from home saying that the boys had been taken for the flags raised in Chortkiv, that so-and-so had been taken. Well, I already figured that if someone was caught, I should be expecting it too. One evening, an officer approaches me and says, "Let's go have a talk." He asked about my parents, if there was a machine gun at home. I said yes, hidden over the stove there. After that, I understood that I needed to start getting ready.

Indeed, about a week later, a car from the special department arrived. They didn't want to arrest me at the base, so they summoned me to the hospital—said I needed to go to Kyiv, to treat my legs a bit. They told me not to tell anyone at the base where I was going, but just to come and go with them. I arrived and saw a UAZ car, an agent from the special department with blue shoulder boards, and a soldier with him. He says they’re going to Kyiv, it's on our way, they’ll give me a lift. They gave me a lift, and I was in the hospital for almost a month.

And then an investigator from Ternopil, Ivan Dmytrovych Lokha, arrived. In Kyiv, they gave me official travel orders to Ternopil. I stayed in Ternopil for seven days or so under surveillance. I lived in a hotel, but KGB officers were with me constantly, asking: “Why so sad?” I kept silent, I didn't want to talk to them about anything. Then I was in the hotel for another three days, but Andriy Kravets's sister was passing by—I was leaving the KGB building, and she was coming right towards me, probably bringing a package. “Oh, what are you doing here?” —“Oh, I'm here on a business trip. Maybe I'll drop by home for a couple of days.” She didn’t understand at first, but later she told my family where she saw me: near the KGB building. So the very next day, my mother, sister, and my mother’s sister came, bringing something with them. After that, they told me, “We are locking you in the basement.” I replied, “I'm not a little boy who's afraid of a basement. But what are you locking me up for?” He says, “There's a reason, there is.” They did indeed lock me in the basement after that. You were under investigation longer, because I was for less time.

V. Ovsienko: The verdict states that you were arrested on June 28, and the trial ended on September 24.

V. Senkiv: I was accused of damaging the monument, for the oath, and for creating the organization. They gave me 4 years in a strict-regime labor camp and 3 years of exile.

V. Ovsienko: It's interesting how you took that.

V. Senkiv: I wasn’t scared to be imprisoned there, so I have no complaints. I was in zone 36 in Kuchino, Perm Oblast, a strict-regime zone. Many fine people were imprisoned there. I saw good Ukrainians of ours there. Levko Lukianenko was there, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Yevhen Proniuk, Vasyl Lisovyi, Oles Serhienko was also there, but not for long—he was brought from the closed prison, he was there for about two weeks, we met once, talked, and then he was taken back to the closed prison. So he didn’t stay in our zone for long. I met not only with the young guys, but also with old OUN members. There were very good people there, I don’t regret having been there. If I had to do it again, I wouldn’t hesitate.

I spent two years in zone 36, together with Stepan Sapelyak. And then I was transferred to zone 37, the village of Polovynka. In the zone, I was always with our guys—whether there were hunger strikes or protests to be written—I was a reliable guy.

V. Ovsienko: Information was passed out of the zone from there. Did you know about it, did you participate?

V. Senkiv: I participated in this, because my father and mother came to visit me, and I passed things through my father. I taught my father to memorize an address in Moscow, then I would pass it to him, and after the visit he would stop by Moscow, even though it was out of his way, but he passed on everything as it should be. I know what was written there, I myself rewrote it, because they gave me what was written in large letters, and I wrote it small on thin paper. I constantly participated in this matter. I knew what was written there, what was being passed on.

V. Marmus: Did you write about yourself?

V. Senkiv: What about myself? Whatever they gave me, that’s what I rewrote, I didn’t write anything about myself.

V. Senkiv: I served almost half my time in the 36th, and then four of us were moved to the 37th. It was some new zone, there were only four of us there for a long time, and then they brought Volodymyr Marmus from the 35th zone and 6 other men. We lived like that for another two weeks until a transport came from Mordovia. Petro Vynnychuk arrived, and Mykola Slobodian, and Andriy Kravets, everyone arrived, and it was more cheerful.

V. Ovsienko: So they gathered almost all of you together there?

V. Senkiv: Yes. Only Sapelyak wasn't with us. But then Mykola Marmus arrived, almost half the village boys were in the zone! So it was fun.

V. Ovsienko: And what was the work like in those zones?

V. Senkiv: In zone 36 in Kuchino, they produced heating elements for irons. They also made plastic handles for them. The sand there was so hazardous that we worked in respirators, it was periclase—we used it to fill the tubes for the irons. And in the 37th, they installed lathes, and I learned to be a turner there.

V. Ovsienko: Were there protest actions there?

V. Senkiv: Zone 37 was new, almost all the prisoners there were young. We had a strike there, almost half the guys took part in it, because it was about the beds. The rules said the beds should have a hard chain-link mesh, but they had welded on these metal strips. You know, it was worse to sleep on that bed than on the floor. We threw all of them outside and slept on the floor. For a long time, 2 or 3 weeks, we slept on the floor and we managed to get them to stop taking the cardboard out from under our mattresses.

And in the 36th I never refused to participate in actions, because I was young, I wasn't that hungry, there was bread, what more did I need? In two years, I was in the BUR [punishment cell] three times. I was young, at first they didn’t really want to mess with me because I was young. And then they gave me 10 days. I served those 10 days. And it was a very bad time, because it was autumn, they hadn't started heating the radiators yet, and it was already cold, freezing. And you only ate there every other day, because you didn't go to work. I served 10 days there, I think: I’ll get out now, the guys will make me some tea. I come out—and they add another seven days. The guys said I came out pale. But the lack of food didn’t bother me too much, just the cold. I was caught at a time when it’s better to be in there in winter or summer, when it's warm. But in the autumn or spring, it's cold, there's snow, and they either haven't started the heating yet or have already stopped it.

In the summer of 1977, I was transported to Siberia. I served my exile in Tomsk Oblast, Parabelsky District.

V. Ovsienko: Mykola Horbal was in exile in Parabel, from 1975-77.

V. Senkiv: Yes, yes. I was brought to the Parabel station, spent the night there, and then was sent on some chartered plane to the village of Lvivka. It was a small village, just one street, maybe thirty houses. To be honest, I had nowhere to live there. On the edge of the village, there was something like a forge, where some drunks lived. I wasn't there for long, because I demanded that they give me a room. They prepared a room for me, plastered it, brought firewood, and said, “You will live here.”

V. Ovsienko: And what kind of work did they give you?

V. Senkiv: People didn't work too hard there. They assigned me as a mechanic in the tractor brigade—to help here, to help there. The brigadier didn’t force me to work much—if he asked, I helped them, because there was nowhere to live and nothing to eat. I went to Parabel, and they gave me 15 rubles a month. But it was alright, when I arrived, they set me up with milk, somehow I managed. There was no one to cook lunch, so I would take sugar with me, pick some berries at the tractor brigade, mix it all up—and I didn't have to go for lunch.

I was there for a month, then they assigned me to go to Parabel, because I was too far away and no one was watching me.* (*Apparently, after Mykola Horbal’s release on June 24, 1977, the informers were out of a job. —V.O.*) And this kolkhoz chairman—he took a liking to me—says: “I have one decent man in the village here—and they want to take him away from here too.” He called the raikom, the raiispolkom, and the KGB, just to let me stay—he says: “Just leave me one normal man!”

V. Ovsienko: Were they all drunks?

V. Senkiv: It was a terrible situation, what was going on there. They took me from there anyway. The commandant at that time was Yuriy Novomlynsky. He was also Ukrainian, but one of those who were born there. His parents may have remembered, but they were ardent communists.

In Parabel, they set me up with a job as a mechanic in a boiler room, a stoker's room. I worked there through the winter, and then my papers came through, and I got a job as a driver on the oil pipeline. I drove people to work. After a year of exile, they gave me a leave of absence. In June 1980, my exile ended.

I got married there during my exile, in 1980, and lived there for a long time because I had a job. And my wife’s mother was old. She didn't have a father. And her grandmother also lived there. My wife is Vera Aleksandrovna Struchalina, my son Aleksandr was born on January 18, 1980, and my daughter Kateryna on March 17, 1982. I came to my homeland on leave many times. We thought we would live there for a while, help the old folks, and then move to Ukraine. And so it dragged on for a very long time.

V. Ovsienko: And there were no thoughts like, if we go back, they’ll imprison us again?

V. Senkiv: I wasn’t afraid of that. While in exile, I visited the guys in Tyumen, then I visited Volodymyr Vasylyk, it wasn’t far from Narym. I met with a Moldovan Jehovah's Witness who was imprisoned in Narym itself. I was on my way to visit a man I had been in the 36th camp with. I asked: for such-and-such a person. “Ah, of course.” I went, said hello, then he looks at me, recognized me, and was overjoyed.

I worked on the pipeline the whole time—as a driver, then as a mechanic on the pipe itself. We finally returned last fall, on September 22, 1999, and are temporarily living with my brother Ivan in Borshchiv. I just got my passport on Saturday, without registration, because my brother isn't here—they can't register me. I asked people here, they say there's no work. And I desperately need a job, because my wife isn't working, the children aren't either, and the old savings have run out—what I brought from Siberia.

My daughter finished school last year, and my son two years earlier.

V. Ovsienko: It's interesting, do they speak Ukrainian?

V. Senkiv: They do, but still poorly. I taught them a bit there, but everyone there speaks Russian. But here they bought themselves Ukrainian dictionaries and primers. I can see that they are more or less speaking and writing. They need to speak Ukrainian, because this is Ukraine, here they should speak Ukrainian. To be honest, I sometimes slip into Russian myself, because I haven’t lived in Ukraine for 22 years.* (*In 2000, Senkiv’s family moved to the village of Sosulivka, Chortkiv Raion. —V.O.*)

15,254 characters.

Published:

Youths from the Fiery Furnace / Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Compiled by V.V. Ovsienko. – Kharkiv: Folio, 2003. – pp. 111–116.

Photo:

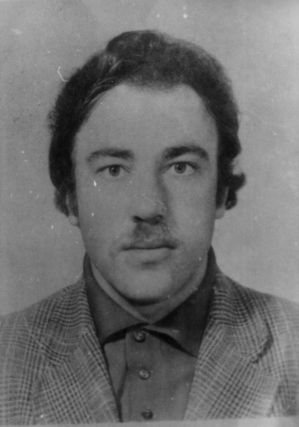

Senkiv1 Volodymyr SENKIV in his youth.

Photo by V. Ovsienko:

Senkiv Film 9993, frame 8. April 4, 2000, Borshchiv. Volodymyr Yosafatovych SENKIV.