(village of Rosokhach, April 2, 2000, in Mykola Marmus’s house,

also present are Volodymyr Marmus and Petro Vynnychuk)

M. Slobodyan: Mykola Vasylyovych Slobodyan, born June 21, 1944, in the village of Rosokhach, Chortkiv Raion, Ternopil Oblast. I studied at the Rosokhach school, finished the 11th grade of night school in 1971. I worked on the collective farm and studied at night school. I traveled for work. In our Rosokhach, it’s a custom to go for seasonal work to the other eastern oblasts.

My mother, Khrystyna Tymkivna, née Balakunets, born in 1902, was ill at the time. My father, Vasyl Mykolayovych Slobodian, was born in 1906. I have a married sister. My parents lived in the village of Rosokhach and worked on the kolkhoz their entire lives. My father was in the war.

When I was younger, my father often told me about the Ukrainian insurgents, how they wanted our Ukraine to be sovereign and independent, and how many of them had fallen. He spoke of how difficult it was for them to fight against the Soviet authorities and what those authorities did to Ukrainians. For example, in the village and in the fields, as was custom, crosses were placed at every crossroads. One evening, they gathered all the party members and communists, got a truck, and drove around the village and the fields desecrating the crosses that had been erected long ago by our grandfathers and great-grandfathers. They took them out of the village, past Yahilnytsia to a place called the Kinzavod, and behind the Kinzavod, there was a ditch—and they dumped them all there, smashed and shattered.

The people watched all this but could do nothing to stop it. Because if you said anything, the KGB would immediately show up—they would take you away and beat you, saying, “What, you don’t like the Soviet government?” They committed many crimes. Even to sing a Ukrainian insurgent song, you had to do it in a whisper, so no one would hear or see, because everything was reported to the district, to the KGB. Even in the Rosokhach choir—you first had to sing two Russian songs before you could sing a Ukrainian one, and only the one they approved, because we couldn't choose for ourselves.

V. Ovsiienko: Everyone had to sing “Pyrih with Cheese.”

M. Slobodian: Yes, “Pyrih with Cheese” and some other one like it. So we knew that Ukraine was under oppression, that Russification was advancing with each passing day, at every step. No one even tried to say a word against it, because it was frightening.

I was 27 or 28 years old, so I understood this perfectly well. I was friends with Volodymyr Marmus and his brother Mykola; we would go to the cinema together. Having heard and seen everything that was happening in Ukraine and in Rosokhach, we would talk about how we were being humiliated, how the Ukrainian language was being suppressed.

We knew that 1973 would be the 55th anniversary of the declaration of an independent Ukraine by the Fourth Universal. Volodymyr Marmus said that we had to mark this date, because people were already forgetting, and the youth didn’t even know what the Ukrainian People’s Republic was, or what our flags and our Ukrainian symbols were. So we decided to commemorate this date—January 22, 1973. Under the leadership of Volodymyr Marmus, we prepared paper and materials—blue and yellow cloth for the flags—and wrote leaflets calling on the people not to forget this date. Some of the guys wrote the leaflets, while others sewed the flags at my house. Mykola Marmus did the sewing. Well, others helped hem by hand. Mykola Marmus prepared the flagstaffs in Bilobozhlytsia, where he was working at the time.

On Sunday, the night of January 21-22, 1973, we gathered near the club in the village of Rosokhach. We already had everything prepared—the glue, the leaflets rolled into tubes, the flags, the flagstaffs. We stayed in and around the club for a bit, so more people would see us and know we were in the village.

I forgot one thing. The day before we were to go to Chortkiv, Stepan Sapeliak approached Volodymyr Marmus. He had a feeling we were preparing something, and he asked to join our organization. We agreed. All seven of us went to his home, where he took an oath by candlelight before an icon of the Mother of God. We all took oaths. We were divided into small cells: the first four took their oath in the forest. We have a clearing there called Lakanets. Sapeliak took his oath at his home, in a kind of outdoor storage shed. And the three of us—myself, Kravets, and Lysyi—took our oath at Andriy Kravets’s home.

Once everything was done, we consulted and told Stepan Sapeliak to take a bus to Chortkiv. We gave him the flagstaffs. They were wrapped in paper and tied up neatly so it wasn’t obvious what he was carrying and wouldn't attract too much attention. The rest of us went to Chortkiv through the Zvirynets forest, across Berdo hill.

When we arrived in Chortkiv, we were supposed to meet Sapeliak; he was supposed to be waiting for us near the “Myr” cinema. But for some reason, he wasn't there. We waited—nothing. Mykola Marmus and another guy went to look for him around town. We needed to start the operation all together, because everyone had a job—some were to glue leaflets, others to hang flags, and a third group was to go a bit ahead to provide cover for those doing the work.

Finally, Sapeliak appeared with the flagstaffs. Volodymyr Marmus and the guys went ahead to hang the flags. Three of us glued the leaflets. Two of the guys would grab me by the legs and lift me up against the wall so I could glue them high enough to be read but not so easily torn down. I had glue in one hand and the leaflets, rolled up, in my pocket. I would just grab one end—zip, I'd pull it out, the roll stayed, and the leaflet was in my hand. It’s true, it was a cold evening with a biting wind and flurries of snow, but we were wearing gloves and simply didn’t notice the cold, as we were focused on such an important task.

We started posting the leaflets and hanging the flags when most people were at the “Myr” cinema for a movie or at the House of Culture, where the youth were at a dance. This was planned so that there would be the fewest people on the streets. We started at School No. 4 and worked our way down Mickiewicz Street to the town hall in the center of Chortkiv, then passed by the “Myr” cinema. We put another leaflet on the wall of a residential building. We were already near the Seret River and still had many leaflets left, so rather than take them home, we glued them in prominent places, like bus stops. After that, as we were heading down into the valley, we saw our blue-and-yellow flag already flying on the town hall in the center of Chortkiv. That meant our guys had already hung it. We crossed through the market, continuing to post leaflets.

I recall one incident. Volodymyr Marmus and Petro Vitiv had just hung our blue-and-yellow flag on the flagpole of the “Myr” cinema. I was walking past the cinema, as I had my own task. At that moment, two rather elderly women walked by me. They noticed the flag and one said to the other: “Look, look—our flag is already flying at the cinema!”

V. Ovsiienko: But this was at night, wasn’t it?

M. Slobodian: Yes, but it was lit up in front of the cinema. There were special sockets there for flags. The guys pulled out their flag and put in ours. And people had already seen it. But we hadn't finished our work yet, because we had designated places to hang flags and post leaflets—it was all planned and thought out in advance.

We pasted one where the administration building used to be and then headed along the road toward Ternopil, here toward Kopychentsi. A red flag was hanging on a flagpole near the forestry department. So our guys took it down and hoisted our blue-and-yellow one in its place.

Then we turned toward the medical dormitory and pasted leaflets, then on to the pedagogical college, where we also pasted leaflets and hung a flag. That’s where our work ended. And then through the park, along the same road we took to Chortkiv, we went home. The wind was blowing with snow—it covered our tracks.

The KGB agents probably didn't see all the leaflets during the night—only the ones in open areas. But there were leaflets and flags hung in places where they couldn’t be torn down right away. So they all remained until the next day, and people who were out during the day saw and read them. And one flag was left at the forestry department. They took it down the next day because they hadn't seen it at night. It was on a tall pole. The watchman at the forestry department was from Rosokhach. So they summoned him to the KGB and interrogated him, asking where he was, what he saw, and why he didn’t see the flag. He said: “I came out in the morning, looked at the flagpole—yesterday your flag was there, and today, I see, our flag is there.” Well, he was an older man, so they, I don’t know, scolded him or what, but they fired him from his job after that because he...

V. Ovsiienko: “Lost his vigilance while on duty.”

M. Slobodian: We returned at about half past one in the morning. No one was out in the village anymore, no lights were on, and each of us went to our own home. Our families were already asleep. They didn't know where I'd come from. Sometimes I'd come home late from the club or from visiting girls.

The day after, we didn’t know anything at first, but when the second bus arrived from Chortkiv—because there's a bus from Chortkiv to Rosokhach—rumors had already started that some people in Chortkiv, maybe students or someone else, no one knew who, had hung blue-and-yellow flags and posted leaflets urging people not to forget about Ukraine. And so, wherever we worked, our ears were tuned to hear what people were saying. We were very curious, because we didn’t think we’d be caught. We had other ideas. We thought we’d do this job, and it would remain a secret.

The KGB didn't come to our village in the first few days. Then we heard: the KGB had come to the village council. They were calling people in: who wants to work in Ternopil? They were building the KhBK—the cotton mill. But it wasn't a real question of “who wants to go?” They simply sent someone from the village council—a man who summons people or delivers announcements. He came to my house and said the head of the village council was calling me in about work in Ternopil. I thought, I'll go.

When I arrived, I saw Vynnychuk was already there by the village council, along with some other guys who were not from our group. Three KGB agents were in one room, and there was another room through a door. They call you in and ask if you want to work there. I say, no, I don't want to work there, because my mother is ill, my father is old, and I need to stay in the village to be near them.

Well, by this time, we had already heard that the KGB was bothering Stepan Sapeliak. The KGB had already summoned him in Lviv, where he worked as a lab assistant, and questioned him about where he was on the night of January 21-22. What he told them is unknown, but we heard that he had been taken in by the KGB. After that, maybe they wanted to get a look at us, which is why they called us to the village council. Because they probably already knew who was in Chortkiv hanging the flags and leaflets. A few days later, I heard they had taken Volodymyr Marmus. Well, it became clear then that someone had betrayed us.

On March 22, they came for me. They searched the house. I had a beautiful embroidered portrait of Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko in a frame, showing Ukraine being crucified in chains, with crows pecking out people's eyes while they were still alive. After Stepan and Volodymyr were taken, my mother had some kind of premonition. She took that portrait and burned it. They found some little books at my place. To be honest, I didn't have any overt anti-Soviet material. But books—they looked through everything, confiscated some. And they took me. They brought me to Chortkiv, to the KGB, held me overnight, and the next day—I know now it was Colonel Bidiovka—he came with two guards and a driver. They put me in a UAZ and took me to Ternopil.

In Ternopil, they tried to scare me a little, to get me to confess where I was that evening, to tell them who was there, what we did, and who did it. I said: “I don’t know anything and I won’t say anything, because how can I say something about someone when I wasn’t there?” For four or five days, they summoned me for interrogation, but I didn't confess. On the fifth day, Bidiovka called me in and, taking a file, covered whose file it was and who had signed it with his two hands. In the middle, he let me read that so-and-so—Volodymyr Marmus, Mykola Marmus—all the members of our organization were listed in that file. I still didn’t confess.

When I was taken back to the cell, I started to think that there wasn’t a single last name on there that wasn't one of ours—only our guys. I guessed that it was Stepan Sapeliak, that this was his doing. What was the point of hiding it anymore? It wouldn’t help. The next day, they called me in again. They interrogated me a couple more times, and I finally confessed that, yes, I was there, that these were the guys who did it—because they already knew everything. Since they knew, my holding out wouldn't have changed anything. I tried to hide some things, but they kept questioning me until they got everything. This Lieutenant Colonel Bidiovka said: “I’ll make you remember every little stone you stumbled on.” In the end, they even prompted me, because the guys who were questioned before had already told them.

So, the investigation ended around late August. We were held under investigation for seven months. They said: “Get your things, we’re going to court.” They put us in “paddy wagons,” each separately, of course, and drove us away. The trial was closed. We were tried by Judge Kostyk and there were some others, I don’t remember their last names—one woman and two men, what do you call them?

V. Ovsiienko: People’s assessors, or “furniture” or “head-nodders.” They just nod their heads in agreement with the judge.

M. Slobodian: Assessors, yes, people’s assessors. The reading of the indictment took a long time. The trial lasted about three days... Volodymyr Marmus is reminding me, because I’ve forgotten a bit—the trial lasted more than a week.

I want to add something. When they brought us in and seated us in the defendants’ dock, we were so eager to say even a word to each other; we hadn't seen each other for seven months! I was sitting next to Mykola Marmus. A convoy guard who had been transporting us stood near us; he was the senior one and Russian. You could tell from his accent. He saw Mykola and I talking, burst into the hall, pulled me up, led me to a basement room, and said: “See, no one’s here. I’ll shoot you right now.” He pulled out a pistol and... Well, he was trying to scare me. I knew he wouldn't do it in that situation, with a trial going on, but he—saliva was flying from his mouth, he was so angry that I hadn't obeyed the order not to talk. When he brought me back to the courtroom, I told the guys what happened, that he had threatened to shoot me. When the judge returned, Mykola Marmus said: “What is this, that they’re threatening us with a pistol and want to shoot us here?” By the next day, that senior convoy guard was gone.

So, the trial ended, and they began to read the verdict. But for some reason, just as they started reading, the lights went out. Did they do it on purpose, to read us our sentences by candlelight? It’s true, they let our relatives who were still in Ternopil in for the reading of the verdict. They gave me 3 years of strict-regime camp and 2 years of exile. And Andriy Kravets got the same. They sentenced us in pairs, it seems, so that only Marmus, as our leader, received the heaviest punishment—11 years. The other guys got 8, the next pair 7, and Andriy and I each got 5.

They brought us back to the KGB, to those cells. It was already night. We spent the night, and the next day they started trying to recruit us as informants. A Captain or Major Ponomarenko calls me into his office and says: “Look, you have 5 years. You’ll serve them, but to make your life easier in there, you need to cooperate with us. We’ll tell you what to do and what to tell us.” I flatly refused. I said my heart and soul wouldn’t allow it, I couldn't be that kind of person. I knew they wanted to make me a *seksot*—a secret informant. He didn’t say anything, to be fair, and I was taken back to my cell. The next day he calls me in again, and for two days he tried to persuade me to go work for them. But they didn’t succeed, because I’m not capable of that; it's just horrible. And so they left me alone.

We were all awaiting transfer. How long did we wait—15, or 18 days? Volodymyr Marmus was the first to be taken. In late October, they took me and Petro Vynnychuk.

V. Ovsiienko: Did anyone file an appeal?

M. Slobodian: No. We didn’t write one, and there was no appeal hearing. One evening, they put us in paddy wagons and brought us to the train station in Ternopil, where a group of soldiers with dogs was already waiting. They surrounded us in a kind of corridor, led us into a “Stolypin” car, and took us away. They took us to Kyiv. We were in Kyiv for about two weeks, maybe a bit more. Then from Kyiv—to Kharkiv. At “Kholodna Hora” they held us for just over a week as well.

V. Ovsiienko: And interestingly, there, at that “Kholodna Hora,” you were probably held on death row? They have bunks there made of a solid sheet of iron...

M. Slobodian: Yes, and the walls are what they call a “shuba” coat—lumpy and bumpy. Yes, those were cells for death row inmates. Then they put us on a train again, in that Stolypin car, and took us to Mordovia, to Ruzayevka station, then Potma, then Zone No. 19, Lesnoy settlement, Tengushevsky district, ZhKh-385/19. Petro Vynnychuk and I arrived there at the end of November. Andriy Kravets was taken to Zone No. 17, Ozerne settlement, Zubovo-Polyansky district.

They bring us into the zone, and a stocky man walks up to us: “Where are you from, boys?” he asks. Well, things felt a bit cheerier; we recognized our own language. It was, as we later found out, Mykola Konchakivskyi. We were taken to the barracks where we were to live. Here, some Ukrainians approached us, and we told them where we were from and what we were here for. Such fine fellows, our boys, former UPA soldiers who had already served 18, 20, more than 20 years in prisons. Besides Konchakivskyi, there were Mykhailo Zhurakivskyi—an older man, Dmytro Syniak, Ivan Myron, Romko Semeniuk, Father Denys Lukashevych (I gave him massages because he asked, an old man), Lubomyr Starosolskyi.

V. Ovsiienko: He wasn't an old man! He was imprisoned at 18, also for a flag, for 2 years.

M. Slobodian: So he was young. From the younger generation, there were Kuzma Matviyuk from Uman, Hryts Makoviichuk from Kremenchuk, Ihor Kravtsiv from Kharkiv, Lubomyr Starosolskyi from Stebnyk, Zorian Popadiuk from Sambir; soon they brought Vasyl Ovsiienko from the Kyiv region, then Yaromyr Mykytko from Sambir* (*b. 1953, imprisoned in 1973 under Art. 62, p. 1 for 5 years).

V. Ovsiienko: Mykytko was brought to us a little later. Mykytko was in the 17th, and when his accomplice Zorian Popadiuk was sent to the 17th, he was transferred to us in the 19th.

V. Marmus: And then Mykytko was transferred to the Urals, to the 37th. He said he was Popadiuk's accomplice. I found out that the older patriots weren't that numerous in the 19th. There were more of them in the Urals. They were transferred there from Mordovia in 1972.

M. Slobodian: After that, we were taken to the barracks and shown where we were to sleep. About two hours later, we were taken to the commandant's office. The camp chief* (*Captain Pikulin. – V.O.) and the zone's doctor* (*Seksiasiev. – V.O.) were sitting there. The doctor said that this one would work in the boiler room, referring to me, and about Petro Vynnychuk, he said this one would go to work in the cutting workshop at the sawmill, cutting boards. This was already in the evening.

The next morning, they gave us clothes, had us change, and took us to the work zone. They familiarized me with the work at the boilers. I worked on the same shift as Dmytro Syniak, an insurgent (he is deceased now). He showed me what to do, as there were two boilers: one was a steam boiler for producing steam for the workshops to heat glue, and the other was for maintaining the temperature in the workshops during the winter.

After some time, I was transferred to the drying workshop. There, we had to take short boards from the cutting workshop, stack them on carts, and wheel them into the drying chambers to be dried, and then deliver them to the workshops where they were glued together to make clock cases—housings. We worked in shifts.

Both at work and in the living area, we socialized with our guys from Ukraine. There were plenty of our boys there with whom you could speak openly. Such conversations in the zone were called “tusovky”—we would walk shoulder-to-shoulder, telling each other things, and that’s how time passed.

There was a dining hall where they served all kinds of porridge—barley, wheat. Pure scraps. And the bread was such that you could mold little balls out of it. With that, a thimbleful of oil, not even fried. You go up with your bowl. You had to have your own spoon. They gave us fish, herring, but who knows how long it had been sitting in warehouses or stores. The fish was sometimes half-rotten and so salty it was impossible to eat. The guys really ruined their stomachs with this, but you had to eat a piece or two to survive somehow, to be able to at least walk a little.

They kept me there from November 1973 until the beginning of 1975. Sometime in August 1975, we were told to get ready to leave the 19th zone; a train was already waiting near the zone. They put us in Stolypin cars and took us away, but we didn’t know where we were going. After a few days, we arrived in Perm Oblast. At night, we were transferred from the “Stolypins” to “paddy wagons” with a convoy to Zone No. 37. It had just been built. A new zone. They brought everyone into a building where there was nothing inside, just walls. They brought everyone in, held us there, and then moved us to a building where bunks were already set up. They brought in some girls who had cooked soup, and the tables had bowls with sliced bread. It was as if they had arranged a cheerful welcome for us, as if they were very kind to us. We understood perfectly well that they were trying to ingratiate themselves. We had supper, and they assigned us to bunks. The bunks were two-tiered. We managed to get some sleep there that night.

And the next morning—reveille, and we were already assigned to our posts. That new building where they had first brought us during the night turned out to be a workshop where there were supposed to be machines—metalworking, grinding, and lathe machines. Those machines were brought in, and they needed to be installed on concrete so that we could then start working on them. We were assigned to various jobs.

I remember when they brought us, very deep snow had fallen. A special group of people was appointed to clear the snow from the residential building to the work building. This was in 1975, in November, I think I remember because it was in November that my mother died—they wrote me a letter from Rosokhach saying she was gone. For some reason, the letter was delayed—it arrived two weeks after they wrote it. They took a very long time to read that letter, for some reason.

My prison term in the strict-regime camp was supposed to end in March 1976. Everyone knows their day, and when it approaches, you start counting down—a week left, three days, two days. That day arrives. They even called me to the commandant's office a day early and told me to get ready. My boys—Volodymyr Marmus, Mykola Marmus, Petro Vynnychuk, Andriy Kravets were there—it was commissary day, so they bought me some things for the road. They took me to the commandant’s office, held me for three or four hours, put me in a Stolypin car, and took me away.

They took me to Tomsk. In Tomsk, I sat in a transit prison for several days. Three militiamen, armed with machine guns, picked me up from there and put me in a car. I don't know where they're taking me or how, but we had to cross the Ob River. They brought me to Kryvosheinsky district, the village of Nikolsk in Tomsk Oblast—a settlement right on the Ob River. They were carrying my case file with me, but I didn’t see it, because the file—my verdict and everything else—was handed over to these militiamen. They were also transporting another guy from Tomsk who lived in this village of Nikolsk. He had robbed something there, a store and something else. Right on the Ob River, one militiaman started bothering me, asking what I was in for, and said: “I’d shoot you right now, throw you in this Ob River—and no one would ever know.” And I just shrugged my shoulders—what else was I to say, when I was alone and so far from home? I didn't argue, because it wouldn't have helped.

They brought me to Kryvosheino—the district center. They locked me in a KPZ* (*Kamera predvaritelnogo zaklyucheniya—pretrial detention cell. – V.O.). It was already dark when they brought me. I sat there all night. They throw another guy in with me. The light was very dim, I couldn't make out what he looked like, but it was a man. He started telling me tall tales, that he had shot his wife, and what would happen to him, and where was I coming from, and for what? I didn’t confess what I had been in for. I said it was under Article 62. But for them, Article 62 means alcoholism, or so they think.

P. Vynnychuk: They really loved that article!

V. Ovsiienko: Article 62 of the Russian code is the equivalent of our 14th: compulsory treatment for alcoholism. It was enough to have committed a crime while drunk or to have a testimony in the case that you drank. It was added on top of the main article. In the zone, they use it to torture you further. I saw this in Zone 55 in Vilniansk, Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Those zeks walk around green, their guts are torn out from that “treatment.” And it’s not even needed anymore: by the time the investigation and trial are over—months go by. Their delirium tremens and that alcoholism have already passed.

M. Slobodian: I mostly kept quiet. They opened the door and took him away from me. In the morning, the chief of police came and I was taken to him. I had a wooden suitcase with me—the guys in the zone had given it to me for the road. It had some old rags in it—what else could I carry? But at least it was something to put a few things in. He said that as of today I am released from prison and am being transferred to exile, but I must check in with the militia every 10 days.

He called over a sort of commandant and said, pointing at me, “Here are his documents, assign him to some job, in some village, because he doesn’t need to be kept here.” As it turned out, Volodymyr Vasylyk was also serving his exile in Kryvosheino, also under Article 62.

The commandant sent me to the village of Nikolsk—it’s about 180 kilometers from Kryvosheino. He says: “There will be trucks going to that village today, I’ll call, you’ll go.” I say that I don’t know the town, where should I go? He told someone to give me a lift to that organization—PMK, or something like that. I went there, and sure enough, the trucks were getting ready to leave. One driver started questioning me. He spoke in Russian, I—in Ukrainian. I was curious if there were any Ukrainians here. He says that there's a smithy here, and a blacksmith named Vasylyk Volodymyr works there. “We’re not leaving yet, go there.” I went there—he wasn’t there. The driver says he’ll be back soon, he went for lunch a while ago, he lives nearby. And indeed, after a little while he says: “And here he comes.”

I walk up and say: “Good day.” And he looks at me like this: “Good day. Where are you from?” I say: “From Ternopil region. And you?” “From Ivano-Frankivsk region.” That's how we met, but there was no time to talk long because the trucks were already leaving. He says: “What do you have in that little package?” “Nothing much—while they were bringing me here, I had a crust of bread left.” He ran home, brought a piece of salo about half a kilogram, but there was no bread at his place or in the store, so he bought some sweet gingerbread cookies for 9 kopecks each. I told him where I was being sent. He says: “It’s okay, I’ll come visit you sometime, or you’ll come to me—we’ll see each other anyway.”

They took me halfway, and then the road was impassable because you have to go through forests and swamps. It was spring, and the trucks didn't dare to go on because they could get stuck in that swamp and sit there for a long time. So they returned to Kryvosheino. And I went with them, because how would I know how to get to that Nikolsk through the taiga? I returned, and the commandant says: “What are you going to do? Go to Volodymyr, to Vasylyk.” So I went. He was glad to see me, his wife was there too. He had received 2 years of imprisonment and 2 of exile for anti-Soviet activity.

V. Marmus: He stood up in defense of a cross.

M. Slobodian: He was so thin, but very resilient. On May 1st in this Kryvosheino, there was a demonstration. He took a bottle, broke it, tore his shirt, and cut his chest with the shards. I later asked him: “Volodymyr, what good did that do you?” He says: “You should have seen how they were all celebrating, and I at least disrupted their rally, so it wasn't so much fun for them.” For that, they gave him an additional two years. I was at that trial, because his wife sent a message to me in Nikolsk through a Romani paramedic.

And Vasylyk’s wife was a doctor at the polyclinic. She really helped me out once. It was very cold, down to -50 degrees Celsius, it was hard to walk to work, you couldn’t breathe because of the lack of oxygen. I went to her: “Mariika, here's the thing: how could I get at least a little break?” She says that we can only do it through the paramedic who works in Nikolsk. “How’s that?” “I’ll call her, and you go to her, she’ll be aware of the situation, she’ll do something there.”

Two days later, I went to the medical station in Nikolsk, the paramedic asked for my last name and said: “I’m giving you a referral to the district polyclinic, saying you have a cold, that there’s something wrong with your lungs and stomach.” I went to the office and said, here's the situation, I have a referral, I’m sick, I need to go to the district polyclinic to get checked out. The foreman I worked for says that nothing will come of it today, maybe a truck will be going tomorrow, and you can go then. And it was very cold, very difficult there.

I went to the polyclinic, met with Mariika, she took a sample of my gastric juice. It showed negative results, and they admitted me to the hospital. I was there for three weeks. They put a militiaman there, the one who had transported me from Tomsk. He recognized me. And I hadn’t told anyone in the hospital who I was—just from Nikolsk, that's all. And he told the doctor that I was an “enemy of the motherland.” That militiaman came up to me and said: “I was just thinking that you... But you're an enemy of the motherland, I know all about you.” A few days later, they discharged me from the hospital. I returned to Nikolsk and continued to work on the farm. There was no other work there, only on the farm. Everyone kept asking: “For what?” So I told them it was for the 62nd. They said that there were many like that now, it was for alcoholism. And I didn't explain further to them.

Remark: If only you had said it was the 70th under the Russian Code!

M. Slobodian: But by the second year, they all knew and looked at me sideways. They housed me in a dormitory—a dilapidated hut, no stove, nothing. I didn't want to live there and told the foreman, maybe I could find an apartment? He said there’s an old babushka there. I said I would help her—do some repairs, chop firewood. He took me there, and I settled in with that babushka and lived there for those two years.

I would travel to a town called Krasny Yar, on the other side of the Ob but a little downstream, to check in. I had to be away for the whole day, but I had to work, I was feeding a group of cows. So the sovkhoz director called and said there was no one to cover for me. So I started checking in once a month.

Then they summoned me to Kryvosheino and told me my term was ending, and they gave me my passport. I really didn't want to take it, but I had to. I boarded a hydrofoil called “Raketa,” sailed down the Ob to Tomsk. From there, I made my way home.

Here in Chortkiv, I also had to go to the militia to check in.

P. Vynnychuk: Forgive me, I’ll remind you that when you returned to the village in early 1978, some younger guys once again smashed the monument to a communist idol.

M. Slobodian: Both this monument across the river, and the same one that we had disturbed. It was as if in honor of my return. The KGB came around again, they had work to do, searching.

V. Ovsiienko: And did they find those boys?

P. Vynnychuk: They found them.

V. Ovsiienko: And were they tried too?

V. Marmus: By then, there was a different approach.

M. Slobodian: They were still too young. There are many people here who still say: “Why didn’t you tell us? If you had told us, we would have gone with you too.” But they say that now, after we’ve been released. They say if I had put out a notice, many would have joined the organization and done something.

When I arrived home, my father and sister greeted me, as my mother was no longer alive. I rested at home for a bit, and then got a job at the kolkhoz to earn a living. I worked at the kolkhoz, and when the administrative supervision was lifted after a year, I would go for seasonal work in Sumy Oblast. We always go for 3-4 months, earn a little money and some grain, to have enough to live on.

After my release, I married Olga, née Svidzynska. We already had a son, Vasyl. He had just turned 5. He was born on January 27, 1973, five days after we hung the flags and posted the leaflets in Chortkiv. Olga and I got married, and in 1982 our son Andriy was born, two years later, in 1984—our daughter Mariika, and in 1986, Mykhailo. Vasyl has already served in the army, gotten married, and already has two children. So I’m already a grandfather, I have two grandchildren. Andriy finished secondary school and is working. It’s very difficult to find work now, so he helps around the house. Mariika and Mykhailo are still in school—Mariika is in the 10th grade, and Mykhailo is in the 7th.

In 1989, “Memorial” was created.

V. Marmus: Why “was created?” We created it!

M. Slobodian: We created it. I joined the Coordinating Council of “Memorial.” This was in Chortkiv, in the park. We were supposed to discuss our issues, but the Chortkiv militia didn’t let us finish. A lot of them showed up and didn’t let us speak. So we moved to another place and created “Memorial” anyway. Then I became a member of the branch of the People's Movement of Ukraine, a member of the Ukrainian Republican Party, and now I'm in the Republican Christian Party.

V. Ovsiienko: Do you work somewhere, do you have your own farm?

M. Slobodian: I live with my children, I keep a cow, a piglet, chickens. My wife used to work at the kolkhoz, but now she's a pensioner. We have our own plot of land now, we grow potatoes, sow barley, cucumbers, tomatoes. We don't live lavishly, but we have no reason to complain or cry. If only our Ukraine can get out of this crisis, then maybe things will be more cheerful, easier. But for now, we must live with what we have and think for the best, and not listen to those who long for bread at 16 kopecks and cheap sausage, and say that now, you see, everything is expensive. But at least we can think and speak freely, and we’re not afraid of anyone or anything. And we’ll have our sausage eventually.

V. Ovsiienko: Mr. Mykola, what is the status of your rehabilitation?

M. Slobodian: I have received rehabilitation. They gave me a certificate for benefits in the district. I used to get gas, electricity, and road transport at 50 percent of the cost. But then they canceled it, said there were no funds in the district. But Volodymyr Marmus helped, so I now have benefits for gas. But with electricity, I can’t seem to get anywhere, although I need it, because the children go to school and need to read and write, and I need light on the farm. Maybe our district officials will somehow restore these benefits.

V. Ovsiienko: Thank you, Mr. Mykola.

Chars. 32497

Published:

Youths from the Fiery Furnace / Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Compiled by V.V. Ovsiienko. – Kharkiv: Folio, 2003. – pp. 80 – 92.

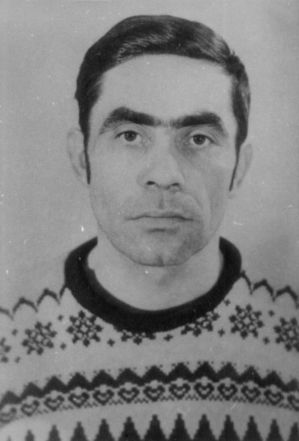

Photo:

Slobodian1 Mykola Vasylyovych SLOBODIAN in his youth.

Photo by V. Ovsiienko:

Slobodian Photo roll 9770, frame 19. April 2, 2000, village of Rosokhach. Mykola Vasylyovych SLOBODIAN.