Vasyl Ovsiyenko. On March 21, 2000, in the village of Pechenizhyn, we are talking with Mr. Mykola Motriuk. His wife Kateryna and son Mykolka are also present.

Mr. Motriuk, first of all, please tell us about your family background.

Mykola Motriuk. I was born in the Kolomyia region, in the village of Kazaniv, on February 20, 1949. At least, that’s what my documents say, although my mother told me I was born three days before Christmas Eve. But that’s how they wrote it down then. My father, Mykola Vasylyovych Motriuk, was born in 1901. In his time, he took part in the liberation struggles and was a rifleman in the Ukrainian Galician Army. My mother, Anastasia Onufriyivna, née Dudchak, was born in 1924. She was a victim of fascist repression: she was deported to Germany for forced labor and worked for a bauer for almost four years. Unfortunately, my parents have passed away. My mother died seven years ago, and my father back in 1968. They were peasants. Dad worked as a blacksmith on a collective farm, and Mom worked at home. That’s how we lived. Dad worked on the collective farm for a long time, and Mom was young (Dad had married for the second time), so he took pity on her and didn’t want her to work on the collective farm too. So around 1952, we moved here, closer to the mountains, to the private village of Markivka in the Kolomyia district.

V.O. And what is a “private village”?

M.M. You see, this is a mountainous area, so there were no collective farms. They established collective farms everywhere else, but they couldn’t here because there was very little land. So we ended up in Markivka. I went to school there with Dmytro Hrynkiv. I finished the 8th grade in 1963 because I started school a year early. There was no opportunity to go study somewhere else because there was no money. We lived in poverty.

After finishing school, boys like me would go for seasonal work in the Odesa and Zaporizhia regions. We earned a little money there to survive. Life was hard then. Not everyone had a job. In our region, there was too much labor. In Pechenizhyn, for example, or somewhere nearby, you had to give a bribe to get a job. Maybe further away there wasn’t such a problem, but here the authorities had taught people this way. And for the girls, it was different. In general, it felt as if we were a very backward people here in Prykarpattia, or something like that.

Then came military service. I served in the Moscow region, 37 kilometers outside Moscow, in Shchyolkovo. I worked as a military construction worker. They took those who had no education or weren’t healthy. By the way, many of those who served with us had served time as juvenile offenders. We built houses.

V.O. The army is a school of Russification. In your childhood and youth, were there any influences that shaped your national consciousness?

M.M. I want to say that my father had many such conversations with me. By the way, Hrynkiv also came over often—he was my friend. Dad would tell stories about how he served in the UGA, how he fought. He didnt fight for long because the Sich Riflemen* (Information on the realities and some individuals mentioned in the interview is provided at the end in alphabetical order.—Ed.) soon came to an end. At 17, he was called up to defend Ukraine. And in 1918, it seems, Poland was already here. When the Poles at the recruitment office asked him if he had served in the army, he said yes. “And in which one, the Ukrainian?” And he was immediately hit so hard that his nose started bleeding. Just for serving in the Ukrainian army. Of course, we had talks like that more than once. This had an influence on me and on Hrynkiv.

And then, after the army, we began to see the world differently. I returned from the army in 1970. I went to work. Dmytro Hrynkiv gave me a recommendation, and I was hired as a metalworker at his Construction Directorate No. 112 in Kolomyia. It later became PMK-67 (mobile mechanized column). We began to communicate more then, and there were more conversations on this topic. By that time, the Sixtiers were already in prison many of the leading human rights defenders were imprisoned.

V.O. And how did you find out about this?

M.M. We listened to radio broadcasts, of course. And Dmytro Hrynkiv was living in an apartment with the Ryzhky family—Paraska and Roman. They had both been in the camps and in exile. This was another push that made us start to think a little differently. The thought crystallized that it was time for us to do something too.

And it turned out... well, the way it turned out. Of course, if we had had someone older to guide us or tell us how to do it, it wouldn’t have happened this way. If there had been some secrecy, then maybe something would have come of that organization. It was only something terrible for the KGB. We didnt do anything illegal. I mean, what kind of “propaganda and agitation” is it when we met with friends and talked—one of us heard this, another heard that, and a third heard something else? That this person is in prison, that one is in prison.

V.O. You were agitating among yourselves?

M.M. Later we began to think that this was wrong. That maybe we deserved a better fate. They counted such conversations, debates, and discussions as “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” We had no leaflets, no public speeches. What kind of “propaganda and agitation” was that? But for the KGB, this was something criminal.

V.O. The other guys say that your first meeting was shortly after January 12, 1972, after the arrests of the Sixtiers. Were you there?

M.M. Well, of course. How could anything have happened without me, since I was there with Hrynkiv? I was directly involved in almost all the gatherings that took place. We met, I think, at Vasyl Shovkovyi’s place. I don’t remember when the first time was.

V.O. Dmytro Demydiv says for sure that it was at Shovkovyi’s place, on January 31.

M.M. Roman Chuprei came and brought Vasyl Mykhailyk with him. Vasyl Kuzenko was probably there too. There weren’t many of us. We began to talk about the need to some kind of organization to be able to fight against this regime in some way. Although we believed that such an organization was, of course, doomed to failure because we knew nothing about secrecy or clandestine methods. But maybe it was youthful bravado, or something like that—just to declare that we were fighting. Of course, no one thought it would be so difficult to get involved in this. But enough empty talk.

V.O. Hrynkiv said that he stuck a knife into the table, everyone placed their hands on the hilt, and you all took an oath. Was there such a ritual?

M.M. There was such a ritual.

V.O. An oath is already a sign of an organization!

M.M. Yes, of course. Once we swore an oath, we created an organization. Although no one wrote anything down anywhere, there were no documents, no statute, nothing was recorded, but it was as if we had already been founded. As if we now existed, as if we were already fighting against that state.

And then there were many such meetings. Well, for the KGB—many, but to me, it doesnt seem so. We met from time to time. But we had to work. We wanted to get a typewriter we wanted to have a tape recorder. To do anything, we needed technical means. You cant do anything with your bare hands. We didnt succeed in that. The organization was probably weak, which is why it failed. I dont know, maybe Hrynkiv says something was there. Maybe Demydiv says something was there. Except perhaps “agitation and propaganda.” In my opinion, we had hardly earned this Article 62, because there was no concrete propaganda and agitation. What could we do? Maybe placing a wreath at the Dovbush monument in the village—that was it. With a yellow-and-blue ribbon.

V.O. And were the gatherings specially convened? Or did you just meet by chance?

M.M. We would arrange to meet on a certain Sunday or a holiday—when everyone was free from work. Or meet on some occasion. Not as if by official order. From the case files, you can see that these were mostly religious holidays.

V.O. Did you suspect or notice that you were already being watched?

M.M. I don’t think our meetings could have interested anyone in the sense that they were against the state, that it was a crime. Because as I said, we had no leaflets, nothing like that. Perhaps only in conversation someone might have said, “We have such an organization, maybe you want to join.”

V.O. Your case file has episodes involving weapons. There were construction pistols, small-caliber rifles. Were you involved in that?

M.M. Directly. You know, young guys mostly want to have weapons, they want to shoot. And Hrynkiv and I went to a shooting club. We worked together, and there was a shooting club at our enterprise, so we would go there and shoot. By the way, Shovkovyi also went there, almost the entire organization. We were involved in shooting sports.

V.O. Did Hrynkiv have access to weapons at DOSAAF?*

M.M. Yes, yes. In addition to being the secretary of the Komsomol organization there, he was a sports instructor or something like that. So we went there often and shot, of course. And we took a pistol with us. Once we took it with us and shot it in the woods.

V.O. What was your purpose for having weapons? Why did you want them? Did the tradition of the recent partisan movement and armed resistance play a role—did you consider the possibility that you might have to resort to self-defense?

M.M. For self-defense. And thats how it appeared throughout the case file. They wanted to incriminate us for wanting to a gang and attack people with weapons. If I had wanted to do that, I would have done it a bit differently. We were just amateurs who liked to shoot, and we had no intention of attacking anyone.

V.O. The arrests began on March 15, 1973. Who was first? How did they find you?

M.M. How did they find us? Ill tell you now. There were already some rumors... The first signal came from Vasyl Shovkovyis father. He worked as a watchman at the village council, and someone told him: “Look, Vasyl, something bad is going on there, the boys are up to something... Tell them to stop whatever they’re doing, or it will end badly!” So we already knew something was wrong.

Sometime later, they took Vasyl Mykhailyk. They arrested him. He was gone for a long time, several days, then they released him. Thats how it seems to me. Well, we sensed something was amiss. And we had hoped we could move about freely and do what we planned. But nothing came of it. Someone else said, “Boys, watch out, something dangerous is going on there.”

On March 14, Vasyl Shovkovyi came to my place (in the case file, according to the documents, he is Ivan, but we called him Vasyl). He came and fixed my radio. We already knew we were under surveillance. When he was leaving for home (Markivka is nearby, two kilometers away), I even joked: “Well probably meet somewhere in Siberia, Vasyl.” That was on the 14th, and on the 15th, we were arrested.

V.O. But Dmytro Hrynkiv says that he gave the order to hide or destroy everything. And he conducted a search of his own home. He supposedly hid everything, but it turned out he forgot to hide the blank for the seal—the most important thing. And they found it during the search. Was there really a wave of alarm among you to hide or destroy everything?

M.M. Yes, there was, there was.

V.O. And did you have anything to destroy?

M.M. I didnt have anything like that. They found something at Dmytro’s place.

V.O. They found a note there where he gave instructions on who should do what.

M.M. What I was supposed to do&hellip I was supposed to collect nationalist songs. And collect biographical data on Orel, the company commander who operated in Markivka. They found that with him, something else with another...

V.O. Little by little—and it added up to a case. Under what circumstances were you arrested?

M.M. March 15, 1973, five or six in the morning. They raided us early. It was a well-planned, simultaneous arrest five of us were arrested at once.

V.O. Oh! So they had a whole operation—to catch such terrible enemies! That must have required several men for each of you.

M.M. A car and witnesses, two officers, some others. Well, they came in and started searching. They didnt find anything. They said, “Were detaining you.” I said, “How can you detain me? You have no right to detain me at home. If I were somewhere in the village or in Kolomyia, you could detain me there. But not like this. You can’t detain me at home.” They showed me a prosecutor’s warrant for a search. I said, “And where is the arrest warrant?” They stood there and didn’t know what to do. Then they said, “We’ll bring the warrant right away.”

V.O. How long did the search last? Searching a rural homestead is no easy task...

M.M. Not long, because there was nothing to search for. They arrived around five o’clock, and by eight-thirty we had left. They brought me to Frankivsk—and it began. The official line was that I was a witness in the Hrynkiv case, and that’s why they were detaining me.

V.O. Why would they detain a witness? They can detain a suspect for three days.

M.M. And they detained me for three days. Then a prosecutor’s warrant for my arrest was issued.

V.O. And during those three days, they probably “worked” with you very intensively?

M.M. Of course, absolutely! They worked from ten in the morning until four in the afternoon, with a break for lunch. They were trying to get a “confession,” or whatever they call it.

V.O. How did you react to the arrest?

M.M. Well, you probably know that yourself...

V.O. I, for one, took my arrest with relief, because I was expecting it. When they finally brought me to the KGB in Kyiv on March 5, 1973 (10 days before you!), at night, I lay down and woke up to someone shaking me. It turns out, I had covered my head, but the guard needed to see through the peephole if I was alive. He entered the cell and started shaking me. He must have been knocking and knocking on the door, but I didnt hear. I came to my senses as he was slamming the door on his way out. Such was the sense of relief that came when everything was finally settled. Everyone reacts in their own way...

M.M. They didnt ask me anything on the first day the conversation started on the second. I also slept normally the first night. I thought it was all nothing serious, just something like: they detained me, so let them. But when they started talking about weapons, I understood that I was going to prison. The weapons were hidden, and I didnt know if they had found them or not, because I had no weapons at home. I didnt know if Hrynkiv had surrendered the weapons or not. So I’m thinking: Im supposedly a witness, they didnt find anything on me, so maybe Ill get away with it. But then, when they told me that Hrynkiv had shown them the weapons... Is the tape recorder still working?

V.O. Its working, of course. Why?

M.M. It just seems like Im talking for a long time.

V.O. Why long? Some people have talked to me for seven hours. If a person has been fighting the Soviet authorities for 50 years and spent 33 of them in prison, they surely have a story to tell! Like Myroslav Symchych,* for example&hellip So, three days passed, and they presented you with a preliminary charge. What were you incriminated with?

M.M. “Treason against the homeland,” Article 56.

V.O. But for that, you needed some specific episodes of “treason against the homeland”?

M.M. Well, they already had them: there were weapons. There was no program, but there were weapons...

V.O. And did they tell you that your colleagues had already been arrested?

M.M. They told me later. Since I was in Hrynkiv’s case, I thought he was in prison. But who else? I didnt know who else was there. Hrynkiv, and then me, next in the case. Then it turned out that Shovkovyi was also in prison at the time, and Chuprei, and Demydiv a month later.

V.O. He was arrested on April 13, the last one. He told me how hard it was for him that the guys were in prison and he wasnt. Like, what must they be thinking of him?

M.M. No one knew who was in prison. We had no confrontations, so how could we know who was in and who wasn’t?

V.O. And who conducted the investigation? We must remember our heroes by name.

M.M. It was an investigator named Sanko. I dont know his first name or patronymic. They were all in civilian clothes. He was a senior lieutenant. He came to arrest me and handled the case until the end.

V.O. Did they use any physical violence against you?

M.M. No. We told everything as it really was. What could they get from us? We even incriminated ourselves.

V.O. Did they use cellmates to put pressure on you? That was often used.

M.M. No. I sat alone for almost three months, then they put a dental technician in with me, Bykov. He was trying to fish for information. But what was there to fish for, when I had already told everything... They thought maybe someone else hadnt said something. They sent in their agents, but it was useless because they already knew everything. We had even said more against ourselves than was necessary. I was explaining how I envisioned the process of Ukraines separation from the USSR... I said a lot of things I shouldnt have. It was all used against me.

V.O. So you conducted “anti-Soviet agitation” with the investigator?

M.M. Yes. But in fact, we hadn’t done anything—not a single leaflet, not a single statement or written protest—nothing.

V.O. Hrynkiv mentioned something. When the alarm was raised that someone had supposedly betrayed the organization, it was decided to convene a meeting and fictitiously announce its dissolution. Did that happen?

M.M. It happened, it happened. And what next? A confession?

V.O. Ah, obviously. You think logically! (They laugh). And yet it was a fictitious dissolution, staged specifically for Taras Stadnychenko, right?

M.M. Well, I dont know how it was. In a word, we were under surveillance—what were we to do? We needed to document it, or something, and turn ourselves in. Or hand over that protocol during a search... When did you talk to Hrynkiv?

V.O. I talked to Hrynkiv on February 8 and 9 at Myroslav Symchych’s place in Kolomyia*. And on the way to Pechenizhyn, I listened to the recording again. And I re-read the literature.

M.M. To be up to date?

V.O. Of course, one must be familiar with the case, so as not to talk nonsense.

How did the trial proceed, how did the guys hold up? Including you?

M.M. Normally. We were glad that it was finally over, that we would know what was what. The hardest part was the first three months of the investigation. The trial was closed.

V.O. How long did it last, by the way?

M.M. Four or five days.

V.O. Wow! And were there many witnesses?

M.M. Quite a few.

V.O. Were they probably the guys who were members of the organization but came as witnesses?

M.M. Yes, my brother, Ivan Motriuk, was a witness, and Vasyl Kuzenko too.

V.O. Here I’ve copied down from Anatoliy Rusnachenkos book, The National Liberation Movement in Ukraine. Mid-1950s—Early 1990s. K.: O. Teliha Publishing House, 1998, pp. 206-208, the names mentioned there. There are two pages of text about the “ of Ukrainian Youth of Halychyna.” Rusnachenko saw your case file, which is kept in the Archive of the SBU Administration for Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. It’s case 37527, in 4 volumes. Unfortunately, Rusnachenko has errors. For example, “Vasyl Mykhailovych” is probably Mykhailiuk. He writes that 4 people were tried, but there were actually 5—Roman Chuprei is not mentioned.

M.M. Vasyl Kuzenko is not a student.

V.O. We need to go through that text and correct everything. Theres a mention of you in a very good book by Heorhiy Kasyanov, “The Dissidents: The Ukrainian Intelligentsia in the 1960s-80s Resistance Movement,” K.: “Lybid,” 1995, p. 143. But unfortunately, you are called “M. Motornyuk” there, and your is called a league... In the book by Yuriy Danyliuk and Oleh Bazhan, “Opposition in Ukraine (Second Half of the 1950s-1980s),” K.: Ridnyi Krai, 2000, on p. 33 your organization is also incorrectly named “Ukrainian of Youth of Halychyna.” And it’s written that it was created by “third-year students of the automation faculty of the Lviv Polytechnic Institute, B. Chuprei, B. Romanyshyn.” No one else is mentioned. And on p. 38, things are mixed up: “...the KGB was actively developing cases against groups in the cities of Kolomyia, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, and Chortkiv, Ternopil Oblast, which included metalworkers of the Kolomyia mobile mechanized column, CPSU member Dmytro Hrynkiv and Mykola Motriuk, a joiner at &lsquoMizhkolhospbud’ V. Marmus*, and others.” Its impossible to understand who belonged to which organization. After all, Volodymyr Marmus* is from the Rosokha group, from the Chortkiv district. Such is scholarship...

M.M. Who else? Vasyl Mykhailiuk, Vasyl Kuzenko, my brother Ivan Motriuk appeared as witnesses. Ivan Kuzenko was not at the trial as a witness.

V.O. So, five of you were arrested. What articles were you charged with?

M.M. First of all, 62 and 64. That’s “anti-Soviet agitation” and “creation of an organization.” The Article 56 “treason against the homeland” charge was dropped when they started gathering these materials for the prosecutor. But for about two months at the beginning, it was there. Then they changed it to the 64th. We breathed a little easier then, as that one carried a sentence of up to 15 years in prison or the death penalty.

The trial was closed.

V.O. Not even relatives were allowed into the courtroom?

M.M. No, relatives were there, but first they were questioned as witnesses. There were some other people sitting there, but I don’t know who they were.

V.O. That would be the “special audience”—KGB guys and their agents. And does the verdict state that the trial was closed?

M.M. The verdict is stamped “secret,” so that means it was closed. And the text says: “in a closed court session.” We also had Article 140—“theft.” That was for the tape recorder. Hrynkiv was preparing a report. It needed to be recorded so it could be printed later. It was an appeal to the people. For that, a tape recorder was needed. We took it in Kolomyia from a not-so-good man. Though I don’t know what he was like, good or bad. I was the “lookout,” so to speak.

V.O. “I didnt steal—I was the lookout.”

M.M. Thats what happened. And then there were Articles 222 and 223—“possession of firearms” and “theft of firearms.” That was for the weapon I was convicted for, a small-caliber rifle. When Hrynkiv and I were still in school, we broke into an office...

V.O. So you did this as schoolboys? As minors? Then they had no right to incriminate you for that episode!

M.M. As schoolboys! We took that small-caliber rifle. That rifle was with Hrynkiv until we were demobilized from the army. And after that, a carbine was added. All of this was stored at our workplace. Hrynkiv and I worked as metalworkers, and we had a shed there where we changed clothes, and in it was a hiding place. The locker had double doors, like a false back wall. You’d open that wall, and all that stuff was stored there.

V.O. He told me that when they brought him to the changing room, he led them to a different one, the common one. They searched and searched there: “Where are your clothes?” He said, “These are my clothes.” They took them, and inside were someone else’s documents, not his. But after a few hours, he “disarmed” himself and surrendered that “arsenal,” because they would have found it anyway. Did you change clothes there too?

M.M. Yes, because we worked together. But on March 1, I was laid off, so I wasn’t working there anymore.

V.O. One more question. I know that Hrynkiv was the secretary of the Komsomol organization at PMK-67. Were you in the Komsomol at that time or not?

M.M. Of course, absolutely! That was the period. People said that earlier they used to force you to join the Komsomol the school principal took part in it. So the boys would escape from school through the windows. We didnt escape anymore. We no longer saw anything bad in it: the Komsomol—so be it, the Komsomol.

V.O. By that time, the youth had been “drawn into” the Komsomol...

Well, you got 4 years in a strict-regime camp. They take you on a prison transport. How was the journey for you, what were your impressions?

M.M. The journey was difficult, the impression was terrible because we saw the world from the other side, the dark side. Those *voronoks* they crammed us into, about 40 men... together with the common criminals. There was no more room, but they kept pushing more in because they had to transport everyone from the prison to the train car. We barely made it there. Then the transit prisons began. It was bad, but after the trial, they brought us together. We all traveled together. Roman Chuprei is a musician, I’m a musician too, so we sang. Hrynkiv helped us, so we formed our own transport ensemble. We sang very well. And we did this in the cells, wherever we were. Even when they were taking us in the *voronok* to the camp, the guards were sitting on a bench in their sheepskin coats and felt boots, as soldiers do. And we were frozen, it was so cold! The winter in Prykarpattia is not like the one there, in the Urals. So they’re chatting among themselves: “We must be transporting the wrong guys. These ones are singing, they’re not sad.” We sang almost the entire way. And it was a long journey. When they were assembling the transport, they took us to Lviv, then they gathered prisoners for Kharkiv. They assembled about two train cars, maybe even more. We waited for about two weeks while they gathered us all together. Then, in Kharkiv, at “Kholodna Hora,” we waited for about two or three weeks until they took us to Sverdlovsk. Theres a “Kharkiv-Sverdlovsk” train. And then from Sverdlovsk to Perm. And from Perm, three of us were sent to Camp 36, in Kuchino. Me, Chuprei, and Hrynkiv. And Demydiv and Shovkovyi were sent to Camp 35. They separated us there.

I served about two years in Camp 36. I was very sick, my furunculosis wouldnt go away. I had a fever. I was horribly covered in boils there. From there, I ended up in the hospital at Vsekhsvyatskaya station. So they left me there, in Camp 35.

V.O. How did you cope with the regime and the work?

M.M. The regime—I have to say, it was very bad in Camp 36. They are very cruel there. When I was transferred to Camp 35, I thought I had ended up in a completely different regime.

V.O. They did that on purpose. The regime was officially the same everywhere—strict—but in reality, it was different in every camp. It was the same in Mordovia. The toughest regime was in Camp 17. In Camp 19, it was easier.

M.M. Here in our camp, No. 36, the beds were wagon-style, with metal strips. And I got a strip made from 40mm angle iron, right on my ribs. We would look for fiberboard, cardboard, and stuff it in. Then a search would come—they’d throw everything out. So I would come to that bed and look at it as if it were a beast—I have to lie down and be tortured again. And when I came to Camp 35, the beds there had springs. It was calm, the regime was easier. In the industrial zone, you hardly saw the guards. We worked at our machines, and that was it.

V.O. Ive been to your former camp several times, after my release. Now, in what was my special-regime section and your strict-regime section, there is the “Perm-36 Memorial Museum of the History of Political Repression and Totalitarianism.” I am a member of the board of that Museum* (*On the night of September 22, 2003, the special-regime building burned down. It is said to have been caused by a short circuit. The building was under repair at the time, so the exhibits had been moved to the strict-regime premises. The Museums management assures that the building will be rebuilt.—V.O.). The punishment cell there is horrendous: an iron table, iron plank bed, a concrete post instead of a stool with an iron plate welded on top. How can one sit on that in the cold? Did you ever have to be there?

M.M. When we arrived from the transport, it was straight to quarantine. Where? To the SHIZO (punishment cell)! For about three days. I dont know why they do that. Then they dispersed us among the detachments. The *otryady*, as they call them. I was in the punishment cell once. Though I wasn’t much of a regime violator.

V.O. Who do you remember from this camp, with whom were you closer, who stood out to you?

M.M. It was very strange for me to see such old men, as they seemed to me then, who had been imprisoned for 25, 30 years. These were our UPA insurgents. Dmytro Paliychuk* from Kosmach, Mykola Genyk*—an associate of Myroslav Symchych*, and Symchych was in Camp 35. There was Vasyl Kulak* from somewhere in the Ivano-Frankivsk region. Ivan Pokrovskyi* was there—he and Levko Lukianenko* were from the same region, from Chernihivshchyna. From neighboring villages. Who else was there? You know, there were good people there. They used to say, “Fascists, fascists!” Investigator Sanko said that: “Well send you to the fascists, it will be worse for you there.” But people live there too. We only understood things better there, what was what.

V.O. Because the best people were truly gathered there. Out here, in freedom, you had to look for them or hear about them on Radio Liberty. And there they were, ready-made, caught for you, you just had to talk to them...

M.M. Those were our “universities.” From the younger generation, the Sixtiers, there were Yevhen Sverstiuk*, Levko Lukianenko*, the Latvian Hunnar Astra*. There were guys from Lithuania, a certain Ramanauskas. From the Rosokha group, there were Volodymyr Senkiv* and Stepan Sapeliak*. And when they transferred me through the hospital to Camp 35, Yevhen Proniuk*, Ivan Svitlychnyi* were already there—famous people. Everyone who saw them mentions their names. But I would like to name those whom no one has heard of. I mean from the times of the liberation struggle. Many of them have already passed away. Stepan Mamchur* was in Camp 35.

V.O. There are currently efforts to have his remains reburied in his homeland. Some people are working on this*. (*Reburied on August 26, 2001, in Irpin, near Kyiv).

M.M. He died there? There were many good people there—but so many years have passed! Ive already forgotten the names. At that time, in our Camp 36, there were protests for the status of a political prisoner. So when I arrived at Camp 35, I told them how it all happened, what the administration did. And in Camp 35, the movement to renounce citizenship had just begun.

V.O. What was your work there?

M.M. In Camp 36, I packed periclase into heating elements, for electric irons. At first, I worked a little as a blacksmith in the forge. My father had taught me, so I could shoe horses. Because there were horses there, they would come from outside the camp. But when the protest actions started, they fired me from that job. They didn’t need me anymore. They sent me to the workshop, where I made those heating elements. And in Camp 35, everyone was a lathe operator. Including me.

V.O. Are you aware that information was sent out from there through secret channels? Did you participate in that?

M.M. I wrote a few articles there. One of my letters ended up in Kyiv with Oles Shevchenko*. Then he was put on trial, and this letter featured in the charges. It’s unpleasant for me to recall this. I was already free when they interrogated me. That was in 1980. I disowned the letter, said I didnt write it. I still feel awkward about Oles Shevchenko because of that. The same head of the investigative department, Rudyi (he was a colonel by then), summoned me to the KGB in Ivano-Frankivsk. He read me this letter, showed it to me. Shovkovyi had rewritten it in a tiny script on thin capacitor paper. He wrote many such things. I said I didnt know the letter, I didnt write it. I was ashamed that I had disowned my own letter.

V.O. What else could you do—confess and go back to prison? And not alone!

M.M. If I had confessed, Shovkovyi would have suffered too. Because he rewrote it. Oles was displeased, and my conscience bothered me a little. But God be their judge.

V.O. And did you have any visits during your imprisonment?

M.M. I had one visit—my mother came. There wasnt much need for those visits because it was far and expensive. Chuprei’s parents were going, so my mother came along with them.

V.O. Interestingly, how were you released? Directly from the camp, or were you brought back by prison transport to the regional center?

M.M. They brought me to Ivano-Frankivsk. Before that, I had to memorize a lot of information: addresses, texts. I wanted to go to Kyiv and pass on that information while it was fresh in my memory, but they immediately placed me under administrative surveillance, and I couldnt go anywhere.

V.O. Thats when they brought me back by prison transport from Mordovia to Zhytomyr and “released” me under administrative surveillance on March 5. I heard on Radio Liberty that the Ukrainian Helsinki Group was already active, I sent word to Kyiv—and Mykola Matusevych* came to visit me.

M.M. Someone visited me too. I dont know who, because I happened not to be at home. They even brought financial aid. They also visited Demydiv and Shovkovyi.

V.O. Did they put you under surveillance right away? For how long? With what restrictions?

M.M. For a year. I had to be home from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., report to the police every Saturday, and not go to Pechenizhyn.

V.O. Was that specifically stipulated?

M.M. Yes. And I worked in Kolomyia. On top of that, there was a problem with getting a job—no one wanted to hire someone with a release certificate. As soon as they looked at it, theyd say, “We dont need you. We dont need you.” I barely managed to find a job. I was already working here, just outside Pechenizhyn, and if theres no bus, I have to run two kilometers into Pechenizhyn to catch one. And the surveillance rules didnt allow me to do that. So I said, “Should I get there by helicopter? Or just go ahead and try me, because I have to pass through Pechenizhyn.” I served that year without any violations.

V.O. Did they set up any provocations for you, to organize a violation of the regime?

M.M. They would come by, but I was lucky whenever they came, I was at home. The district police officer, detectives from the criminal investigation department would come. As for Shovkovyi, he’s our veteran in this matter. He was under surveillance for three years. They kept extending it for him.

I managed to find a job about a month after my release, purely by chance—through an acquaintance I had worked with before my imprisonment. He was already an energy specialist at another company. I told him my story, and he said, “There’s an opportunity. If you want, come work with us. I’ll get you a job.” It was a furniture factory in Kolomyia. A children’s furniture factory.

V.O. Did the KGB have any complaints against you? Did they summon you?

M.M. Wherever I worked, I had a minder. There was this one foreman. He was Russian by origin, but he was born here. A decent man, with a higher education. After some time, he came up to me and said, “You know, I’m in such a stupid situation... Forgive me, but they told me to watch you and report on you!” I said, “Thank you for telling me! There’s nothing unexpected here, don’t worry about it.” He was the only one who confessed to me. But there were others, of course. We had a guy named Koloskov, the KGB district officer for the Pechenizhyn area. He would come to my workplace, summon me to the office, talk to me there, ask me what’s what and what’s going on. In general, you could feel that they weren’t asleep, that they were still watching us. But new times came, and they calmed down a bit. But when Ukraine was declared independent, they remained, they are still living, thriving, and working under our flags.

V.O. Yes, yes. For example, I heard that the investigator who handled my last case in Zhytomyr, Major Tchaikovskyi (he was a major when he arrested me in the camp in 1981), was being appointed as the head of the Security Service in the Zhytomyr region around 1995, already with the rank of colonel. I protested, wrote to the SBU. Well, they expressed their sympathy and politely replied that, you see, he had not violated the laws of that time. Then I wrote to the President: “Who are you relying on? He fought against the emergence of the Ukrainian state! Do you think he is a good specialist? You are mistaken! The fortress he defended, the Soviet , fell. Now he will bring down Ukraine for us too!” I wrote that such “specialists”—“masters of the dirty work”—should be removed from the SBU. Let them earn their bread with a sickle or a hammer. A real one, not a paper one. I received a reply, but it was not so polite. Tchaikovskyi worked for three years, then he was dismissed. He probably has a good pension from the Ukrainian state now, against which he fought so fiercely.

M.M. Well, we have to put up with it. Ukraine is not yet what we hoped for.

I had problems with work. I am a specialist—thats how I see myself. I graduated from a cultural and educational college, I had a diploma, and I wanted to work in my field. In Kolomyia, the department of culture was headed by a former communist, Klapchuk. And he remained a communist. In 1985, I wanted to get a job there. He hired me. But I didn’t tell him that I had been imprisoned. After it turned out that I had served time, he fired me. He said, “Culture is a political beacon in the village, and a man like you shouldnt be working here. Please, clear your desk.” I left, of course.

That was in 1985. And when the Chernobyl tragedy happened in 1986, they took me, a former political prisoner, to clean up after the accident. They tried to take me twice—I refused, but the third time they took me. I thought, well, this must be my fate, what can I do? I served my time there and returned. And theres Koloskov, our KGB district officer: “I hear you were in Chernobyl?” I said, “Yes. When it comes to Chernobyl, a political prisoner can go and work, but when it comes to working in a club—then no.” “Well,” he says, “they made a mistake. They shouldnt have taken you to Chernobyl. It’s just some information we have here.”

When the revival of Ukraine began, the declaration of independence, I thought, I should be able to work according to my diploma now! I wrote a letter to that Klapchuk: “When should I believe you? Back then, when you said that culture should only be your pro-communist, pro-Soviet kind, or now, when you speak under blue-and-yellow flags? Where is the justice in this?” He then wrote me a letter back: “Come, lets talk.” I came. “Oh, how could this be! I don’t remember. Where? That can’t be! How could I have fired you? No, that never happened!” He tolerated me for about four years, then found a reason to fire me anyway. And he still works there. And all his staff still work there.

V.O. And when the national revival began, the movements of 1988-90, did you participate in any public or political organizations?

M.M. Of course, we tried as best we could. There were elections, and we tried to enlighten people, to tell them who to vote for. We organized trips with amateur art groups, brought politicians with us who would speak before the concerts. Then we sang patriotic songs. Now, of course, that euphoria is gone.

I was enrolled in the Ukrainian Helsinki *, which in 1990 became the Ukrainian Republican Party*. I still have its membership card, but no one bothers with me. What is there to argue about!? I feel very sorry about that. I wanted there to be a real human rights organization, not just a political one. There are people who need protection. I think you have found your calling in this.

V.O. In the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, I am running a specific program: creating the Ukrainian part of the International Dictionary of Dissidents, recording autobiographical stories of former political prisoners, and preparing them for publication. But I am not involved in specific human rights work now. I see that it is beyond my strength right now. And if you take on a case and cant help, youre just fooling yourself and others. Youll only compromise yourself and the cause. Its better not to get involved. I answer such people this way: “Fifteen or twenty years ago, I could have helped you get into prison. It was simple back then: there’s a human rights violation—I write about it, pass it abroad. You get imprisoned, and the person responsible gets imprisoned. But now I don’t know how to protect anyone specific from this gang! They do whatever they want, the law doesnt apply to them. And they are not afraid of international publicity.

Kateryna Motriuk: There is no law for them, Ive seen it myself...

V.O. This is your wife, Kateryna, and what did you name the boy? What year were you born?

Mykola Motriuk: Mykolka, born in 1991.

Kateryna Motriuk: We married in 1991.

M.M. And bought a baby right away.

V.O. Im glad that at least some former political prisoners have managed to somehow get their lives back on track after those hard times, after those losses. I just visited Zorian Popadiuk*, Yaromyr Mykytko*, and Liubomyr Starosolskyi*. They have wonderful wives and even more wonderful children.

M.M. Maybe they live a bit more comfortably?

V.O. Popadiuk was the head of the district administration in Sambir for a while. And now he’s in charge of the culture department. And hes already in huge debt. He inherited a huge house from his mother, and it needs to be heated, paid for! He doesn’t have the money. Power didn’t affect him at all: he remained a decent person. That is, he didn’t steal. Mykytko is in charge of ecology there. And Starosolskyi finished building his fathers house in Stebnyk (his father started it, and he finished it), but he lives with his mother, wife, and three daughters in the old little house because they can’t pay for the gas. The potash plant in Stebnyk was closed, which caused terrible unemployment. Everyone is struggling in their own way. And I, you see, remained an old bachelor. While I was playing Cossack on the modern Sich, all the best girls were taken... Now I’m the “master of the transit prison.” If you are ever in Kyiv, you can spend the night at my place. As Taras Shevchenko said: “And I have no children crying / And my wife does not scold me, / It is quiet, as in paradise, / Gods grace is everywhere— / Both in my heart and in my home.” So, former political prisoners stay with me.

M.M. We were in Kyiv once. Yevhen Proniuk* organized some mass protests there.

V.O. That was the “pink revolution.” You must have been at the Constituent Congress of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons on June 3, 1989? It was held on Lviv Square because they didn’t let us into the building.

M.M. No, this was in 1990, at the House of Cinema. It was a very rich program. We met with many former political prisoners, talked. Good memories remain. Your materials were there, there were photographs from the reburial of Vasyl Stus*, Oleksa Tykhyi*, and Yuriy Lytvyn* on November 19, 1989.

V.O. We already mentioned that there were books written about your organization. Do you know of any other publications about you? Did you write anything yourself about your case, or did someone write about you?

M.M. Shovkovyi should know about this. He says something was published abroad. In England, or where?

V.O. There is a thick book, about 500 pages, called *The Ukrainian Human Rights Movement*. It was compiled by Osyp Zinkevych and published by “Smoloskyp” in 1978 in Toronto-Baltimore. It has a full-page portrait of very handsome young men—Ivan Shovkovyi and Dmytro Demydіv. But there is no text about your there, you are all just mentioned in the list of political prisoners. There are also four and a half lines about you in Liudmyla Alexeyeva’s book, “History of Dissent in the USSR.” It was first published abroad in 1984. I have the 1992 edition, Vilnius-Moscow, “Vest,” on page 11. By the way, this edition was prepared by Yevhen Zakharov, head of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. And have you or anyone else written anything in the local press?

M.M. We published one article in the local press. That was in 1993. Shovkovyi and I put it together ourselves. It’s presented as if a journalist is interviewing us. But we wrote it ourselves.

V.O. Thats how it’s sometimes done. If you still have that article, Id like to have a copy. And please include the name of the publication and the date. Its not for nothing that I say that history, unfortunately, is not always what happened, but what was written down. So you should try to write the truth yourself, so that the truth becomes history. Otherwise, you see how many mistakes even people with academic degrees make.

M.M. Ill try to write it. I don’t know what impression it will make. Maybe some of our guys will claim that we had an organization. But in my opinion, we had nothing we were tried for nothing.

V.O. But I believe you were properly appreciated. The enemy saw where it was all heading.

M.M. Of course. But we regret that we didn’t have time to do anything.

V.O. That you had little time is another matter. The Soviet government punished for intentions just as it did for actions. And often, it attributed intentions that werent there.

M.M. If only we had printed a few leaflets and explained something to the people.

V.O. Ill tell you this: our generation was no worse than the previous ones. We did not remain silent, but continued the work of our predecessors. But we are luckier than our predecessors because independence was achieved in our lifetime and with our participation. Whatever it may be, it exists, and we have seen it. Our predecessors perished without achieving it or living to see it. And now our task is to fill it with our content. Because the people in power are not the right people at all. And, most importantly, the property is owned by the wrong people. It’s not for nothing that the state has not officially recognized the lyrics of the national anthem, only the music. Because it says: “We, brothers, will rule in our own land.” For now, it’s not Ukrainians who are ruling.* (*In early 2003, the lyrics of the anthem were recognized by the Verkhovna Rada.—Ed.).

Well, now Ive started agitating you. Its time to go to Vasyl Shovkovyi. Thank you.

V.O.: While preparing this publication, I asked Mykola Motriuk additional questions, to which he responded in writing on February 8, 2005.

What did you gain from that new world and those new people you met in the camps?

You can’t just say right away. On the one hand, there was the loss of freedom: prisons, transports, transit prisons, vicious guards with dogs, prisoner transport cars, and somewhere far, far away—freedom. And I was only 24. I wrote about it like this:

Квітує земля зелами сходить медовий місяць кує зозуля мов лискучу мідь мої літа окутані дротами глухо впала сльоза на човганий бетон перші зорі свердлять серце.

And so we were in the camp. They greeted us, smiled at us, asked where we were from. This first impression has stayed with me for a long time, especially the warm eyes of the long-term prisoners, who saw in us their sons who had taken up the torch in the struggle for Ukraine’s liberation from the Bolshevik yoke.

Which of these people would you like to talk about and what would you like to say?

I want to talk about the long-term prisoner Ivan Pokrovskyi. I remember how, I think it was in 1974, we were celebrating Easter. We gathered what little we had, brewed some tea, and there was even one egg. Pokrovskyi said a prayer, and when he finished, he exclaimed: “Christ is Risen! And may Ukraine be Risen!” This struck me deeply. I was once again convinced that no force could defeat such a people.

Who planted what seeds in your souls and how did they sprout?

I would like to thank the late Ivan Svitlychnyi, and also Ihor Kalynets, for their guidance in the world of poetry. True, I never became a poet, but I did manage to scribble a few camp verses.

What spirit did you carry out of captivity into the post-camp atmosphere of persecution? What warmed your hearts?It was the spirit of a rebel and an anti-Soviet. I was under administrative surveillance, as were my comrades. And what warmed our hearts was the memory of our camp fellowship and the belief that the empire of evil and violence would perish, that the Ukrainian state would be reborn.

What negative experiences did you take away from captivity? Do you have any regrets about what you lost?

I believe that any experience, no matter what it is, is always positive. I saw how people broke, unable to withstand the difficult trial of captivity. But I myself, thank God, served my term “from bell to bell” and have no regrets about anything. I consider it a great honor that I was fortunate enough to join the struggle for Ukraines freedom.

What hopes do you have for the future in connection with the change of power in Ukraine?

To be honest, none. Because 13 years of hoping for an improvement in the lives of political prisoners and the repressed have led to nothing. We, the former political prisoners, are still not noticed by government officials. In our village, we werent even invited to the Independence Day celebrations.

Information on individuals and realities mentioned in M. Motriuks interview

Astra, Hunnar, Latvian human rights activist, political prisoner. Died in the spring of 1988, one month after his release.

Hrynkiv, Dmytro Dmytrovych, leader of the “ of Ukrainian Youth of Halychyna” (1972). Born June 11, 1949, in the village of Markivka, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Arrested March 15, 1973, in Kolomyia. Charged under Articles 62 § 1 (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”), 64 (“participation in an anti-Soviet organization”), 81 (“theft of state property”), 140 (“theft”), 223 (“theft of weapons and ammunition”) of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR and sentenced to 7 years in strict-regime camps and 3 years of exile. Served his sentence in camp VS-389/36 in the village of Kuchino, Perm Oblast. Released in 1978. A writer. Lives in Kolomyia.

Genyk, Mykola, an insurgent, from Bereziv in the Kolomyia region, imprisoned in Perm camps in the 1970s.

DOSAAF - “Dobrovolnoye obshchestvo sodeystviya Armii, Aviatsii i Flotu” (Voluntary Society for Assistance to the Army, Air Force, and Navy). An organization created by the authorities to prepare youth for service in the Soviet Army.

Kulak, Vasyl, an insurgent from Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, a 25-year prisoner, was imprisoned in the Perm camps.

Lytvyn, Yuriy, Nov. 26, 1934 - Sept. 5, 1984. Poet, publicist, member of the UHG. Imprisoned 1953-55, 1955-65, 1974-78, 1979-84. Reburied in Kyiv at Baikove Cemetery on Nov. 19, 1989.

Lukianenko, Levko, b. Aug. 24, 1928, imprisoned on Jan. 20, 1961, for 15 years under Articles 56 and 62 § 1 for creating the Ukrainian Workers and Peasants . Arrested a second time on Dec. 12, 1977, under Art. 62 § 2 and sentenced to 10 years and 5 of exile as a founding member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. Released in December 1988. Head of the UHU, URP, Ambassador of Ukraine to Canada, Peoples Deputy of the I-IV convocations.

Mamchur, Stepan, served 5 years in a Polish prison (1934-39). A participant in propaganda mobile groups to eastern Ukrainian lands. He was a *stanychnyi* (local leader). In the 1950s, he settled in Irpin near Kyiv. Arrested in 1957, sentenced to 25 years. Died on May 10, 1977, in camp VS-389/35 in Perm Oblast. Reburied in Irpin on July 26, 2001.

Marmus, Volodymyr, b. March 21, 1949. Leader of the Rosokha group, imprisoned on Feb. 24, 1973, for 6 years and 5 years of exile under Articles 62 § 2, 64, and others. Served his sentence in camps in Perm Oblast and in Tomsk Oblast.

Matusevych, Mykola, founding member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, b. July 19, 1947, arrested April 23, 1977, as a member of the UHG, sentenced to 7 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile. Released in 1987.

Mykytko, Yaromyr, b. 1953, imprisoned as a student at the Forestry Institute on March 23, 1973, under Art. 62 § 1 for 5 years. Served his sentence in Mordovia and Perm Oblast.

Paliychuk, Dmytro from Kosmach, insurgent, a 25-year prisoner, imprisoned in the 1970s in the Perm camps.

Pokrovskyi, Ivan, b. Sept. 7, 1921, in the village of Shtun in Volyn. Insurgent. Was caught in a raid, became an *Ostarbeiter*. Arrested Dec. 7, 1949, in Baranavichy, sentenced to death by an OSO troika, which was commuted to 25 years. Served his sentence in Kazakhstan (Karlag, Karaganda, Taishet, Omsk). Released from the Perm camps in 1974.

Popadiuk, Zorian, b. April 21, 1953, imprisoned as a student at Lviv University on March 23, 1973, for 7 years and 5 years of exile under Art. 62 § 1, arrested a second time on Sept. 2, 1982, and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment and 5 years of exile. Released on Feb. 5, 1987.

Proniuk, Yevhen, philosopher, b. 1936, imprisoned on July 6, 1972, for 7 years and 5 years of exile under Art. 62 § 1. Permanent chairman of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons, created on June 3, 1989. Peoples Deputy of Ukraine of the II convocation.

Sapeliak, Stepan, b. March 26, 1952. Member of the Rosokha group, arrested Feb. 19, 1973, sentenced to 5 years imprisonment and 3 years of exile. Served his sentence in the Perm camps and Khabarovsk Krai. A poet, laureate of the T. Shevchenko National Prize in 1993.

Sverstiuk, Yevhen, b. Dec. 13, 1928. Literary critic, publicist, one of the leaders of the Sixtiers movement. Imprisoned on Jan. 14, 1972, under Art. 62 § 1 for 7 years and 5 years of exile. Served his sentence in the Perm camps and in Buryatia. Doctor of Philosophy, Laureate of the Shevchenko Prize in 1993.

Svitlychnyi, Ivan, Sept. 20, 1929 - Oct. 25, 1992. Recognized leader of the Sixtiers movement. Imprisoned on Aug. 30, 1965, for 8 months without trial arrested a second time on Jan. 12, 1972, under Art. 62 § 1 and sentenced to 7 years and 5 years of exile. Laureate of the Shevchenko Prize in 1994, posthumously.

Symchych, Myroslav, b. Jan. 5, 1923, commander of the Bereziv company of the UPA. Imprisoned on Dec. 4, 1948, for 25 years, received a second 25-year sentence for participating in a strike. Released on Dec. 7, 1963. Imprisoned again on Jan. 28, 1968, without trial for another 15 years, and for another 2.5 years at the end of his term. A total of 32 years, 6 months, and 3 days of captivity. Lives in Kolomyia.

Sich Riflemen - regular formations of the UNR Army in 1917-1919.

“ of Ukrainian Youth of Halychyna” (SUMH) - an underground youth organization. It emerged in January-February 1972 in the village of Pechenizhyn, Kolomyia district, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. The initiator of the s creation was Dmytro Hrynkiv, a metalworker. SUMH considered itself the successor of the OUN in new conditions its goal was the creation of an independent Ukrainian socialist state (similar to Poland or Czechoslovakia). Hrynkiv and engineer Dmytro Demydіv were developing a statute and program for SUMH, but they did not have time to adopt them. The group consisted of 12 people its members (workers and students) held meetings (a kind of seminar), obtained several rifles, learned to shoot, collected OUN literature, memoirs, and insurgent songs. SUMH was uncovered by the KGB, and in March-April 1973, its members were arrested. Five of them were convicted (Dmytro Hrynkiv, Dmytro Demydіv, Mykola Motriuk, Roman Chuprei, Vasyl-Ivan Shovkovyi).

Starosolskyi, Liubomyr, b. 1955, imprisoned in August 1973 for 2 years for raising a flag in Stebnyk, Art. 62 § 1. Served his sentence in Mordovian camp No. 19.

Stus, Vasyl, b. Jan. 7, 1938 - Sept. 4, 1985. Arrested on Jan. 12, 1972, under Art. 62 § 1, sentenced to 5 years of imprisonment and 3 years of exile (Mordovia, Magadan Oblast). Arrested a second time on May 14, 1980, died in a punishment cell of the special-regime camp VS-389/36 in Kuchino, Perm Oblast, on the night of September 4, 1985. A member of the UHG, poet, T. Shevchenko Prize winner in 1993, posthumously. Reburied on Nov. 19, 1989, at Baikove Cemetery along with Y. Lytvyn and O. Tykhyi.

Tykhyi, Oleksa, Jan. 27, 1927 - May 5, 1984. First arrested in 1948, imprisoned on Jan. 15, 1957, for 7 years. Arrested for the third time as a founding member of the UHG on Feb. 5, 1977, and sentenced to 10 years in a special-regime camp and 5 years of exile. Served his sentence in Mordovian and Perm camps. Died in captivity. Reburied along with V. Stus and Y. Lytvyn at Baikove Cemetery on Nov. 19, 1989.

Chuprei, Roman Vasylyovych, b. July 1, 1948, in the village of Pechenizhyn, now Kolomyia district, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, member of the “ of Ukrainian Youth of Halychyna.” Arrested on March 15, 1973, convicted under Art. 62 § 1 (anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda) and 64 (creation of an anti-Soviet organization) to 4 years imprisonment. Served his sentence in camps in Perm Oblast.

Shevchenko, Oles, b. Feb. 22, 1940, journalist, arrested on March 31, 1980, sentenced to 5 years imprisonment and 3 years of exile under Art. 62 § 1. Shovkovyi, Vasyl-Ivan Vasylyovych, b. July 7, 1950, in the village of Pechenizhyn, now Kolomyia district, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Member of the “ of Ukrainian Youth of Halychyna.” Charged with Articles 62 § 1 (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”), 64 (“creation of an anti-Soviet organization”), 140 § 2 (“theft”), 222 § 1 (“manufacturing and possession of weapons”), 223 § 2 (“theft of weapons”). Sentenced to 5 years in strict-regime camps. Served his sentence in Perm Oblast.

Shovkovyi, Vasyl-Ivan Vasylyovych, b. July 7, 1950, in the village of Pechenizhyn, now Kolomyia district, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Member of the “ of Ukrainian Youth of Halychyna.” Charged with Articles 62 § 1 (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”), 64 (“creation of an anti-Soviet organization”), 140 § 2 (“theft”), 222 § 1 (“manufacturing and possession of weapons”), 223 § 2 (“theft of weapons”). Sentenced to 5 years in strict-regime camps. Served his sentence in Perm Oblast.

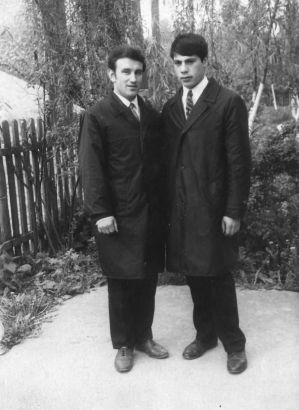

Motriuk Film 9629, frame 11F, March 21, 2002. Pechenizhyn. Mykola MOTRIUK.