FAMILY

Vasyl Ovsiyenko: On February 8, 2000, in the glorious city of Kolomyia, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, in the hospitable home of Mr. Myroslav Symchych,* (*Information about some of the political prisoners mentioned in this interview, as well as other realia, can be found at the end in alphabetical order. – Ed.) Mr. Dmytro Hrynkiv tells his story.

Dmytro Hrynkiv: I, Dmytro Dmytrovych Hrynkiv, was born in the village of Markivka, now in the Kolomyia Raion, into a simple farming family. My father belonged to the respected Hrynkiv family in the village, and my mother was from the Kopyltsev family; her name was Olena Yuriivna. My father’s brother Vasyl was one of the Sich Riflemen, and his son Mykola (my first cousin) later fought in the UPA as a machine gunner in Spartan’s company. Of course, the legacy of the Sich Riflemen was very close to our family’s heart.

My father, Dmytro Petrovych Hrynkiv, was born in 1900, while all his peers—born in 1888, ‘89, ‘90, and all those years—all joined the Sich Riflemen.* But my father was later drafted into the Polish army, where he served with the cannoneers (artillery).

Since my father’s older brother, Vasyl Petrovych Hrynkiv, had joined the Sich Riflemen, the younger one, Dmytro—my dad—stayed on the farm with my grandfather Petro. He had to manage the whole farm, and so he married early (just as he turned 20) his friend’s sister, Paraska Pryimak. Incidentally, my father’s friend, Vasyl Pryimak, who was two years older (b. 1898), joined the Sich Riflemen and fought in many battles, and was also on the Italian front.

I am a son from my father's second marriage. His first wife, Paraska, was shot by the retreating Hungarians. There was a front line in our village of Markivka. The Hungarians wanted to take a cow from the barn, but she was a very persistent woman and refused to give it up. So one of the Hungarians shot her in the back of the head with an exploding bullet. My father came home to find his wife dead in the yard, her face torn apart. At the time, he had three sons and one daughter from his first marriage. None of them are alive now: two sons were killed by a landmine, and one fell near Königsberg after being mobilized into the Soviet Army. That was my half-brother, Vasyl Dmytrovych Hrynkiv.

My mother was my father's second wife. He married her in 1947, after the war. It was her second marriage as well. Her husband, they say, had died of typhus, and she was left with a small child—my maternal half-brother, Vasyl Mykolayovych Kopyltsev.

I was born on June 11, 1948. My mother was unable to have any more children, so I remained the only child my parents had together.

Of course, in those days my father helped our boys—the insurgents—because his nephew was fighting in Spartan’s company. Our extended family—both the Hrynkivs and the Kopyltsevs—was also in the local armed unit. My father was able to help by transporting fodder with his cart, delivering whatever was needed to the company. Many things essential for the insurgent movement passed through our house. Sometimes, Dad would even butcher an animal here to feed the insurgents (a pig or a calf). When such a task came up, he would do it.

His daughter Maria, my half-sister from his first marriage, was very active in helping the boys. She was a liaison. I recall being told about an incident when two insurgents were fighting off NKVD officers in an outlying field near our house. It was an unequal battle in broad daylight. The whole village, as they say, held its breath, seeing that the boys were down to their last bullets. For some reason, they rushed toward the village. Running through it, they fired back at the attackers, the NKVD men. There were many of them, and they flew after those boys like rabid dogs. One of the boys was breathing heavily, wounded in the arm. He was passing through our yard and recognized Maria. Apparently, he had some connection with her, which is why he headed for our yard. He threw down some documents and other things wrapped in a military tunic and said to Maria on the run: “Hide this, I beg you.” The boys dashed into the next thicket and disappeared.

Well, of course, the NKVD officers had their long-range viewers, their binoculars, and they noted that the boys had turned into our yard. They came and turned everything upside down. They started tormenting Maria—she was the eldest: “Why did he run in here, what did you say to him?” She said: “I only gave him a drink of water because he was exhausted. I didn't know who he was, but he was wearing military breeches, so I thought he was one of your men, since he was in uniform.” Well, of course, they searched everywhere but found nothing. It turned out—she was a clever girl—that she had thrown the tunic with the documents into the cow’s manger under the hay, and the cow was chewing the hay, so they didn't search there, although they did go into the barn to see if the boys were hiding there. It was a heroic act. One can imagine the state my father and mother were in, having witnessed such an event almost before their eyes.

Later, when my cousin Vasyl began to visit my father more often in the evenings, my father helped him and Spartan's company in any way he could. My cousin (who had the pseudonym “Vynohrad”) was a machine gunner for the company and carried out specific assignments. For example, there was one such case (I describe it in one of my short stories). He and another insurgent, with the pseudonym “Zvirobiy” (St. John’s Wort), also a machine gunner, on their own initiative and with the permission of the company commander Spartan, caught a large detachment of NKVD men and *“strybky”* (*“Strybky,” “yastrubky” – from the Russian *istrebitel* [destroyer]. Paramilitary groups created by the NKVD from the local population to fight the insurgents. – Ed.) in a crossfire. This detachment had arrived in four Studebakers* (*American-made trucks that the USSR received during WWII through the Lend-Lease program. – Ed.) from Pechenizhyn, where an NKVD garrison was stationed. Before this raid by the garrison troops, word had gotten out about their plan, so the boys asked to take on this daring mission, assuring the company commander that it would be done without a major battle. Otherwise, there would be heavy casualties on both sides. They would stop them without a fight and force them to return to their garrisons. At first, the commander hesitated to entrust such a task to just two men, saying it was impossible: “You are going to certain death, boys.” But they assured him they could do it. They had a plan, and they went.

One of them took up a position on the side of the village of Runhory, while Mykola, my cousin, took up a position on the side of Markivka. They let the trucks pass by toward the forest and thus ended up behind the NKVD men, who had already gotten out of their vehicles. The boys, with their machine guns, chose good spots—and opened fire over their heads as they were lining up in ranks. They fired in such a way that all the NKVD men fell into the mud and couldn't lift their heads. The bullets whizzed over their heads, so as not to hit them too badly, to avoid casualties among them, and thus they made it clear that they couldn't go into the forest. The NKVD men must have consulted among themselves and understood the situation, and they slowly began to retreat to the Studebakers. They hid behind the Studebakers, but the boys kept them from retreating into the forest. So they got into their trucks and drove away.

This was, of course, highly praised, and they both received awards for this operation, which averted a danger to Spartan’s company. There was such an incident in our village...

Well, as for that—I was small, born in 1948. The only thing that stuck in my memory was when those NKVD men would come to our house, tear up the floor in the barn with their ramrods, shout, beat people, and always take my father away somewhere—I remember that, but I was very young. Sometimes they would come when my mother was home alone, ask where Dad was, and in Russian they would force her: “Cook kulesh, cook kulesh.” And sometimes my mother was forced to cook for the enemy, just to get them to leave the house. But everyone knows this, everyone lived through it.

V.O.: And that battle you were talking about, when was it?

D.H.: It was around 1945. My cousin himself told me about it. He is no longer living. I can't say how he left the company.

YOUTH

I graduated from the Markivka eight-year school. I started in 1955, and in 1961 I went to the Pechenizhyn school, which at that time was an eleven-year school. That was right during the Khrushchev era, when they established 11 grades. I graduated in 1966. At that time, it was very fashionable to go to construction projects on Komsomol assignments. But first, my brother and friends recommended it to me: “You know history well, go apply to the Ivano-Frankivsk Pedagogical Institute for the history department.” If I had gone, it’s not impossible that I would have been accepted and studied there. But my friends, especially Roman Chuprey, said: “It’s not fashionable to be a teacher anymore. You know, it's the age of technocrats, of engineers—let's go to the Lviv Polytechnic Institute, to the power engineering department.” It was such an unknown profession to us. I took my documents from the Ivano-Frankivsk Pedagogical Institute and submitted them to the Lviv Polytechnic. Of course, I made a mistake, because I had to switch gears for the exams right away. I had been preparing for history, I knew the humanities, but for the Lviv Polytechnic, you needed more math and physics. I passed the written math exam, but I failed the oral one—a new section, logarithms, had just been introduced. I was, as they say, a bit lost there. Although the instructor who was administering the exams said: “You will definitely get in next year, I can see it in you, you will know everything. We hope to see you.” And I said: “Next year, I probably won’t be here.”

But fate turned in such a way that I met that instructor again several years later, when I was applying to the Institute of Oil and Gas in Ivano-Frankivsk. She was also on the admissions committee there and recognized me, because she had a good memory for last names. Besides, a distant relative of mine, Vasyl Hrynkiv, was already a fourth-year student there. She knew him well, so she asked if we were related.

Well, I just up and went to one of those so-called new construction projects on a Komsomol assignment. We were all Komsomol members then. I went to Dnipropetrovsk, choosing the city for unknown reasons. A city on the Dnipro River, with factories being built there, and that attracted me. I thought, I'll work for a year and then come back to apply to the Institute of Oil and Gas or the Polytechnic.

So I went. I ended up at a factory that served a large housing trust, “Dniprobudmekhanizatsiya.” That trust had a factory—the Dnipropetrovsk District Repair Plant. It was near the Tire Plant—a giant in Ukraine. Many people from the Ivano-Frankivsk region came on the same assignment—from the Rohatyn district, from our Kolomyia district, there were some from Bohorodchany. We became friends with the guys. They immediately placed us in brigades where most of the people were from Eastern Ukraine. The foremen were also from there, and they were good craftsmen. They said right away: “We’re taking the boys from the Ivano-Frankivsk region because these boys are hard workers, they’ll do a good job.”

We went to the mechanical workshop as apprentice metal structure fitters. There were various structures there—from simple construction railings for balconies and stairs to more complex ones, like those garbage chutes. You had to understand blueprints for that. We started to master it. The chief engineer of the plant noticed us and recommended that a few of us go to study at the Construction Institute. For the time being, we enrolled in preparatory courses at the request of this chief engineer. But we didn't manage to get in, because we were already being called to the military enlistment office of the Amur-Nyzhnodniprovskyi district of Dnipropetrovsk and signed up for the first summer draft (at that time, on the initiative of Marshal Grechko, reforms were beginning in the army to shorten the term of military service).

I wrote a letter to Chuprey—Chuprey, I think, had passed all his exams for the Lviv Polytechnic but didn't get in due to the competition. We wrote to each other, and I invited him to come join me, so we could be together. We were friends and wanted to be together. He came, we passed the exams together, and they gave us the second skill category. We worked for about three months, mastered our trade, and started working in Mykola Hulah's brigade; he was a foreman from Eastern Ukraine, a wonderful person. But we were still drawn to Western Ukraine.

By the way, Roman Chuprey’s mother (I used to talk with his family) had made a great contribution to the development of the “Prosvita” society in Pechenizhyn. Pechenizhyn is a large town. Our village is small, but theirs is big. His mother, Hafia Lutsak, told us many interesting things that were not in the school curriculum. She said that now there was an overwhelming dominance of the Russian language, that we were not even reading the right literature, that this literature was missing… And she always turned us back to those times when that literature was available, and now it was banned. This depressed us: why was it banned? Roman and I were always of the same mind on this issue: this ban had to be circumvented. Why should it be this way? Why was Hrushevsky banned? She knew the works of Mykhailo Hrushevsky, his *History of Ukraine-Rus'*, very well. She got us that kind of literature, and we were already reading it back then. But when we ended up in Dnipropetrovsk, we no longer had the opportunity to read it or talk to her. The atmosphere and the people there were different. But we recalled that literature with pleasure and often talked about it in the company of the Eastern Ukrainians. They would listen in amazement—about the Sich Riflemen, about the UPA fighting units in Western Ukraine. They were very surprised.

There, they usually called all of us “Banderites.” We didn’t get angry. If some Russian had said it, with malice—but they said it with a kind of respect, it seemed. We were even proud of it and felt freer at that factory. They were such open people. We didn't sense any suspicion toward us. We could have even been used by some forces because we were so simple. We understood that we were Ukrainians and they were Ukrainians, and we would just tell them straight: “Why are you speaking Russian? Let's start speaking Ukrainian.” They would shake their heads and marvel at our simplicity. Because they had clearly had their fill of all that, so they kept quiet. But they were very friendly towards us.

Eventually, we received notices from the military enlistment office because we were of draft age. Roman immediately figured it out and said: “I’m getting out of here.” After passing one medical commission, he left. But I stayed behind. My delay was because I had a girlfriend there—my current wife. I told Roman: “You're leaving, but I can't go.” Because I intended to marry her. But I was still young, that was still in the plans. I said: “I'll probably stay and try to get in here, either at the university or at that Construction Institute where we took the preparatory courses by arrangement with the engineer.”

But that year, by order of the Minister of Defense Grechko, two-year service was introduced, and they were drafting from the age of 18. They did a spring draft, and I was supposed to be assigned to submarines based on my specialty. There was a worker at the plant, a very big man, with a Cossack build, and he told me: “See how big I am? But those submarines ruined my health, now I don’t want anything. Avoid them by any means!” “How can I avoid them? I've got the summons—see?” “I’ll advise you on how to do it. Ask the military commissar of the Nyzhnodniprovskyi district for permission to go home, and then don't come back on time. Just say you were late, that your parents were crying…” And I was living in a dormitory in the Dnipro district, on the left bank of the Dnipro, and I traveled to work on the right bank.

Alright, so that's what I did. I told the military commissar that for the few days they give before the draft, I would go to Markivka. I went, said goodbye to my parents, but I stayed for two extra days. When I got back, the military commissar was stamping his feet, yelling, foaming at the mouth: “These Banderites are shell-shocked, awkward, and cunning, they’re all like that! You'll never make a good man, a good soldier. And I wanted you to be a good soldier!” I thought to myself, “What a ‘university’ they had in mind for me: they wanted me to go to submarines!” “Well, alright, you'll go to the tank troops!” He didn't like the tank troops: this military commissar's unit had been destroyed in our region during World War II. Between Horodenka and Kolomyia, he had lost an entire tank regiment; they were destroyed by German units. That's why he recalled Kolomyia, where I had traveled, with such bitterness. So, on his part, this was supposed to be revenge. But for me, it didn't mean revenge—I could serve anywhere.

I was drafted in June 1967. I ended up in Oster in the Chernihiv region, in that training corps on the Desna River, which trained sergeants, junior specialists, and tank driver-mechanics. I was assigned to reconnaissance units of swimmers who service the PT-76 amphibious tanks. I completed my training, became a driver-mechanic, and fulfilled all the requirements. There was a condition that whoever finished the training with distinction would have the right to choose a unit within the Kyiv Military District. I chose Dnipropetrovsk. Everyone was very surprised because Dnipropetrovsk was considered very dangerous for tankers. They thought it was a hole, that it was bad to serve there, they said the Communist Division was there—where are you going? But I did it because my girlfriend was left there—such a romantic attachment. Of course, I didn't end up in Dnipropetrovsk itself, but near Novomoskovsk, where two tank units were stationed. As we called them, military settlements—Cherkask and Hvardiisk. They said it was the famous Marshal Chuikov who, looking at a map at the bend of the Samara River where it flows into the Dnipro, said: “After the war ends, station tank units here.” I completed my tank service there, as a sergeant.

Nothing special happened during my service, but since it was the Communist Division, they started to pressure me, asking why such an active sergeant like me wasn't in the Party. I knew from my village that Party members weren't well-regarded. And they were like, what are you doing, what's wrong with you, and so on… The propaganda there was quite serious, and I was the only non-Party sergeant left in that reconnaissance unit. And the head of reconnaissance for the whole division was a Major Volodin. He started approaching me, suggesting I stay on as an officer: “We see you’re so well-trained, you’ve finished a training school. But that's impossible because you're not in the Party—you need to join the Party.” I had no one to consult with, as I was alone in that unit, so I just asked another sergeant who was about to be demobilized: “What will it do for you, being in the Party?” And he said: “Well, that’s how it is today, but tomorrow it could be different. I can always leave the Party.” He was from the Vinnytsia region. I thought to myself: anything can happen. I had also heard that Party members could help in various situations. And this romantic notion captivated me. I thought to myself that if I became a Party member, I wouldn't change my views, but maybe I could contribute something to the Ukrainian cause. I agreed.

Sometime in August or September 1968 (I remember it was warm), I had to go to Dnipropetrovsk to become a candidate member. On the commission was a major general whose name I didn't know. They asked banal questions, but the general asked about my family. I said they were simple peasants. They nodded. Obviously, they had made some inquiries; there was a special department for that. I returned to my unit, and then Major Volodin told me I had been accepted as a candidate member and my candidate term was starting.

I qualified for reduced service, so I didn't serve the full three years. Some of those who finished training with me were already demobilized; I would meet them in Dnipropetrovsk as civilians while I was still serving. It was strange to me why they were discharged and I wasn't. I raised this question. The major said I had a few months left, that I would get out of the army in the fall. So I was discharged not in June, but in November 1969.

By that time I was already married. My girlfriend, Hanna Serbyn, used to visit me at my post from Dnipropetrovsk. I had studied with her at the Pechenizhyn school: she was in class “A” and I was in “B.” By mutual agreement, we had gone to the construction sites in Dnipropetrovsk together. Hanna told me she had relatives in Dnipropetrovsk. Though, we never actually connected with those relatives.

During one of her visits, Hanna complained that a sergeant at the checkpoint had made a snide joke, something like, we get plenty of these “loose women” coming here. So, to avoid such talk and rumors, Halyna and I decided to get married. It happened on October 26, 1968. Her official name is Hanna, from the Serbyn family. She's from the Poltava region, the village of Vechirky in the Pyriatyn district. That village (I visited it later) is not far from Berezova Rudka, where the famous manor house is located, the one Taras Shevchenko used to visit. Apparently, somewhere there, in that Berezova Rudka, he painted the portrait of that famous lady.* (*T. Shevchenko visited the Zakrevsky brothers' palace in Berezova Rudka in 1843, and at that time painted the portrait of Hanna Ivanivna Zakrevska. He also visited there in 1945-47. – Ed.). There is now a film about Shevchenko that mentions Berezova Rudka. When I was in Vechirky, people said that a mirror and other relics from Taras Shevchenko's time were still preserved there. So, my wife was from there, from the Serbyn family. On her mother’s side, she is a Dyka, of Cossack descent. They say that the Cossack Dyky family founded the village of Vechirky. And on her father’s side, she is from the Serbyns. As for how they ended up here—that’s another story...

So, I got married and was discharged from the army in November 1969. Where was I to work? I went back to the same factory in Dnipropetrovsk where I had been drafted from. They put me on the Party register. The Party organizer thought for a moment and said: “You know, you’re such an active young man, I see you’ve returned to your home factory—so I'm recommending you for a medal for the 100th anniversary of Lenin's birth.” They were supposed to award this medal in April 1970. And I just up and said that I didn’t know how much I needed it… Because I thought medals were given for some merit, but it turned out they had selected a few workers who had been working well since their demobilization. In the meantime, I had written home, and my brother wrote back that things were a bit tough there, that my parents were old, so why had I stayed there? Come back home. Then I wrote to my friends, and they also suggested I return home. I decided to go with my family, because I already had a family: in December 1969, our daughter Olenka was born, and things got tighter for us in Dnipropetrovsk, so we decided to go back home, where we had housing and everything else.

And so we did. It happened so quickly that the factory administration didn’t even have time to react. The Party organizer called me in, irritated, and said: “How can this be? We had high hopes for you, and you're leaving? You can't leave—we are putting you up for a medal award here.” I said: “Do I really need that medal?” And he said it looked disrespectful, because everyone wanted to get a medal. But for me, it was incomprehensible: what did I need that medal for? He was very annoyed and said he didn't expect this: “This is a Westerner, why is he like this?” But what he said didn't stop me.

He must have written some kind of accompanying note, because when I came to the Kolomyia City Party Committee to register, the secretary who handled registration looked up at me and said: “Aha-a…” He drew out the word like that. So they already had some kind of report on me. He says: “Oh, you’ll have to go through the candidate term all over again. Why did you leave Dnipropetrovsk without waiting for them to accept you there?” If I had received that medal there, I would have been accepted into the Party right after, I understood. I was just a few months short of completing the one-year candidate term. But I messed all that up, and now they were telling me I had to start over. Some kind of eternal candidate. But I didn’t take it to heart. The candidate dues were paid just like member dues back then.

I found a job in Kolomyia. We settled in Pechenizhyn with my wife’s parents, the Serbyns. Her father was a supervisor at the boarding school there, and her mother worked at the hospital. The apartment there was quite spacious, large. I didn't go to my own village because it was harder to commute to work from there, and it was closer from Pechenizhyn. In that same year, 1970, I got a job at construction management office No. 112 in Kolomyia. It later became PMK-67 (mobile mechanized column), and the director was Cherniavskyi. I worked as a fitter-assembler because that was the trade I had from the Dnipropetrovsk factory. They didn't object. I immediately got on the housing list, because as a construction worker, you could get an apartment quickly. Construction in Kolomyia was quite intensive at that time, and apartment buildings were being completed on schedule and quickly.

Meanwhile, I was intensely preparing for entrance to the institute. After a few months, they gave me a decent, standard reference, saying that I worked well. I was applying to the Ivano-Frankivsk Institute of Oil and Gas. Since they had opened an evening department in Kolomyia, where professors from the institute would come to teach, I began my studies there in 1970.

In 1971, the time came for me to be accepted into the Party. Before that, the company's Party organizer, Kyzylov, approached me and said: “We’ve been watching you. You write good reports about construction workers for the newspapers. And we have a situation where there's no secretary for the Komsomol organization. It’s a respectable, large organization. Could you head it, being a candidate for the Communist Party and also having entered the institute?” I thought about it and consulted with my friends. The guys said it was a good idea.

In the meantime, I began to move to Kolomyia: I needed to live somewhere nearby because it was becoming difficult to commute from Pechenizhyn. I registered in a dormitory and had to spend the night there at least once a week so the commandant would see me. But in reality, I was a family man. I decided to bring my wife to Kolomyia as well. I found an apartment. And this apartment caused a revolution in my consciousness. I realized that I was on the right path. I became friends with the people I was living with. They had been participants in the liberation struggles. Paraska Ryzhko, the wife of the master of the house, Roman Ryzhko, was from Pechenizhyn, had been a liaison for the UPA, and had served 10 years in Karaganda. And he had been in the SS “Halychyna” Division.

They were conscious people, and they started to have various conversations with me. But he was quite cautious with me because I had told him I was a Party member and showed him my Party card. And he just stood there, looked at it, and said: “And what will this do for you in your quest to do something for Ukraine?” I said: “Maybe this way, maybe not.” And Paraska from the house said: “You did wrong to join the Party. Look at what the Party members are doing!” And she started giving all sorts of examples that I had never heard before. A split personality began to develop in me, being a Party member on one hand, and on the other hand, being shown that this party was criminal. And Paraska was a very knowledgeable woman. They had a rich library. They showed me several old books.

Of course, when I met with my friends, I would talk about how Ukraine needed to break free from servitude somehow. Because I saw that even at the institute, there was a clear dominance of the Russian language, and we were forced to study from Russian textbooks. There was *“sopromat”* instead of “strength of materials,” *“teplotekhnika”* (heat engineering). Well, we translated it ourselves as we studied.

V.O.: And what language was the teaching in?

D.H.: The mathematician taught in Russian; he was Jewish. The history of the CPSU was taught by a sincere Ukrainian named Tverdokhlib. I had a chance to talk with him. He was a respectable man, spoke normally, but you had to learn the entire course on the history of the CPSU and pass it. And Marxist-Leninist philosophy—if you didn't respect these subjects, they would push you aside, ignore you.

And then our Kolomyia evening department of the Ivano-Frankivsk Institute of Oil and Gas was liquidated in our second year. Although we strongly advocated for a branch to be in Kolomyia, because we have no higher education institutions here. But the Party officials came and said at a student meeting: “We’re sorry, but there’s no possibility of constructing a building.” And our evening department was indeed squeezed into various schools. For example, in the second school. We even studied in the assembly hall of the shoe factory. Those part-time students had a rough time of it, and then they had to switch to correspondence studies.

Meanwhile, in 1971, they called me to the bureau and finally accepted me into the Party, on the recommendation of that Party organizer Kyzylov, who had “married me off” to the post of secretary of the Komsomol organization. I started working as the Komsomol secretary. They began to pressure me: “Many people from the villages are coming to your enterprise, but you’re not accepting anyone into the Komsomol. You need to prepare these people to join.” I would tell the girls who came to the vocational school to study as painters and plasterers to join. They’d say: “But we believe in God.” If they believed in God, they wouldn't join the Komsomol. I said: “Believe in God ten times over, it won't hurt you. Just don’t tell the admissions committee, and believe to your heart's content.” And some of these young people needed to get apartments from the construction administration, so they thought it was not a bad idea and started joining the Komsomol. But one of the secretaries, I think the second secretary, figured out my tactic. They called me to the Party bureau and began to criticize me, saying that Hrynkiv was using such tactics. Because one of those “sincere Komsomol members” had told on me: “Hrynkiv told us to say that. Believe what you want, but join the Komsomol.” That’s how she gave me away. At the bureau they said: “How could you? What are you allowing yourself?” They wanted to remove me as the Komsomol secretary, to give me a Party reprimand. But the party organizer Kyzylov waved them off. He was some kind of retired military man, a rather solid, influential figure, known in the city and in Party circles. He told them: “Forget it, we’ve seen worse! He's a good guy, he gets the job done.” This was a man who understood the system well. That it was all for show, just a facade. Later, during some inspections from the region, he would say: “Dima, make sure all your paperwork is in order! The main thing is the papers, and the rest…” And he would wave his hand, not finishing the sentence, because it was self-evident.

“UNION OF UKRAINIAN YOUTH OF HALYCHYNA”

While talking with my classmates—Roman Chuprey, Dmytro Demydov—we spoke about how some changes were happening in Ukraine, and we were being left on the sidelines. And these changes were such that even the nightingales were singing about them, all the birds were chirping, and it felt like we had been left out of the course of history. We started to speak openly about this with Paraska Ryzhko. And she said: “Well, there is important work to be done. If you want to, here you go: there's samvydav, and you’re not reading it, not distributing it.” We asked her: “Where can we get it, what do we need to do?” “You should listen to the radio broadcasts!”

So we came to the decision to develop a concept of self-education, to learn more about what was happening in Ukraine. The year 1972 arrived, and there was a huge uproar about the arrests of the intelligentsia, about how Petro Shelest had written the book *Our Soviet Ukraine** (*Kyiv: Publishing House of Political Literature of Ukraine, 1970. This book, which was meant to define the limits of what was permissible on the national question, was sharply criticized at a meeting of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU in March 1972. In May, P. Shelest was dismissed from his duties as First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine and appointed Deputy Chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers. In May 1973, he was removed from the Politburo. He lived out his days at a dacha near Moscow. – Ed.). Paraska told me about this matter. I got angry and said: “How can this be, that people are silent? Why were they arrested? We must scream about it!” And she said: “And how can you scream? You're a Party member, you won't scream.” “I won't scream?! I have to do something!…”

This got under my skin so much that I went to Chuprey, gathered the guys in January 1972, threw my Party card on the table, and said: “Boys! We have to take up something to fight for Ukraine.” Dmytro Demydov said: “How can you say that, you're a Party member?” “Nonsense! All the Party members at the top are fighting for Ukraine, what did you think? Look how many of the intelligentsia have been arrested! Were they not Party members? Did they not understand the need to fight?”

The guys believed me. Later, during the investigation, Demydov said exactly that: “How could I not believe him, when a Party man threw his card on the table and said we had to fight for Ukraine?” He told this to the KGB agents, and the agents understood well that this was a strong argument they couldn't counter.

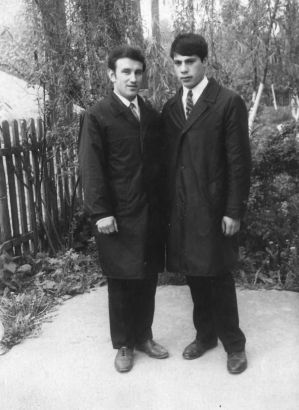

I said: “We're creating an organization.” “Let's create one.” They agreed to create an organization. Since I was the “accumulator” of this idea, they recognized me as the leader. Demydov said he would be the organization's ideological developer. Right there, at the first meeting in January, he was given the task of drafting our organization's program. We named the organization the “Union of Ukrainian Youth of Halychyna.” Since Roman Chuprey was studying at the Lviv Polytechnic Institute at the time, I think in his second year in the automation department, he was given a separate task to recruit a few students from the Lviv Institute into our organization. The first issue was the creation of the organization, that is, to recruit reliable people who truly wanted to fight for Ukraine.

Paraska listened to all those radio broadcasts every night and every day. She was an active person and saw that a spark had ignited in us. We didn't really hide it, we said: “There are some boys like that.” I brought these boys to her, and she told them what she had heard on the broadcasts. We already knew about the murder of Alla Horska,* about Valentyn Moroz's* works “Amid the Snows,” “A Report from the Beria Reserve.” They were read on the radio, we listened, and we retold them to each other. We worked in a general way like that. And then we decided we needed to expand our activities. We couldn't work without a program. Demydov worked on the program for a long time, and then, when we met for the second time in February, we assigned specific tasks to everyone.

We swore an oath of allegiance to Ukraine in January 1972. It sounded very simple and direct, but there was one romantic nuance regarding responsibility. On the table where we were sitting, there was a knife with a beautiful, ornate handle. I said: “We must swear on the knife. We won't cut our hands and spill blood to swear on blood.” I stuck the knife into the table, placed my hand on it, and said an oath something like this: “I swear allegiance to the ideas of Ukraine, for which thousands of people fought and died, and they preserved this idea in their hearts. So let us too preserve this idea, for we will fight as long as our hearts beat and as long as we have strength.” Everyone placed their hands on mine and swore: “I swear!” It was a very simple version, and it happened so spontaneously that we barely noticed. Ivan-Vasyl Shovkovy took the oath then. Was he in the camps with you?

V.O.: Unfortunately, no. I was in Mordovia then.

D.H.: Yes, Ivan-Vasyl Shovkovy was at Vsekhsvyatskaya, in Perm Oblast.

V.O.: Is Ivan-Vasyl a double name?

D.H.: Yes, a double name. We found out later that he had a double name; the KGB agents opened our eyes to that. We knew him as Vasyl, but it turned out that his passport name was Ivan. Well, who was going to check? Roman Chuprey, Dmytro Demydov, Vasyl Mykhailiuk, Fedir Mykytiuk, and Mykola Motriuk swore the oath. At first, six men took the oath on that Christmas holiday evening in January.* (*D. Demydov indicates the date as January 31, 1972. Indeed, the UYHG was formed after the January arrests of the intelligentsia, which began on the 12th. – Ed.). And in February, the following people also took the oath: Liubomyr Chuprey—Roman Chuprey’s brother, a power engineer who had already completed higher education (as had Demydov—he was a chemical engineer-technologist). Ivan Motriuk and Vasyl Kuzenko also took the oath.

Later, Vasyl Ivanovych Hrynkiv was unofficially admitted into the organization. He was asked if he would join the organization and if he would lead it. We wanted to accept him. He was a very powerful intellectual, had graduated from a pedagogical institute, and had gone to teach mathematics somewhere in the Rivne region, I think in the Sarny district. We met him in the summer of 1972. He was a Party member and a rather well-known guy. We told him: “Don't be afraid, because I'm a Party member too. Everyone is fighting for Ukraine now.” He said: “Yes, I feel it and I understand that it’s true. But if they find us, you know what will happen to us?” “So what are we to do? Someone has to start,” I said, “someone has to do something.” He was present at our meeting, reacted favorably to our ideas, but said: “Dmytro, I see that the way you speak, the way you lead this, there's no need for any other leader besides you.” And he declined the leadership and went back to his teaching job. Because in the summer he was still at home, but he started teaching in September.

I gave out assignments individually. At first orally, but then—you can't keep track of who did what. So I prepared some sheets of paper (one of them later ended up with the KGB, which they used to “unravel” us during the investigation). For example, under pseudonyms it was written: “‘Lisovyk’ has the task of studying reliable data about such-and-such a company commander who operated in the territory of Markivka village.” To another one: reliable data about another person who was in the UPA; write down the texts of songs that were sung on that part of the village. Seemingly simple tasks like that. Another was tasked with obtaining such-and-such illegal, banned books from the library of a certain collector. Well, for example, General Petrov’s—there were books like that there. About the Sich Riflemen—what was banned. By the way, one of these books figured in our investigation. We read all of that.

Oh, another task was to look for weapons. This was a romantic notion, as the boys were all young, so as to interest them in weapons. Everyone welcomed this, saying, let it be, let everyone have some kind of personal weapon. Not to shoot at anyone, but the specific question of whether we should offer any resistance was not raised.

At that time, I was the head of DOSAAF* (*DOSAAF – *Dobrovolnoye obshchestvo sodeystviya Armii, Aviatsii i Flotu* [Voluntary Society for Assistance to the Army, Air Force, and Navy]. An organization created by the authorities to prepare young people for service in the Soviet Army. – Ed.) at this enterprise, and at that time, passing the GTO* (*“Gotov k trudu i oborone” [Ready for Labor and Defense]. – Ed.) standards was very popular. I conducted shooting practice with the Komsomol youth brigades and had access to weapons. So, I could save cartridges that the brigades hadn't used. That's why later, during the search of my house, they confiscated about 600 cartridges from me. I also had access to Margolin pistols—10-shot small-caliber pistols. It was a wonderful weapon. To this day, I regret not keeping at least one pistol as a relic from those times. But it’s a weapon—what good would it do us now? God grant that no one shoots you and you shoot no one.

So, I had the opportunity to take this pistol from DOSAAF on request and conduct training for my boys. I taught them how to use weapons, taught them safety. There were three such training sessions in the summer of 1972. They were held in the tracts between Markivka and Molodiatyn. There are such tracts there, Chymshory and Kupchava. We would go out there. Not all at once, but like, three today, then maybe a week later three others, to a different tract. The shooting had to be done in some ravine, so that the sound would be muffled, because the Margolin pistol is loud. I got targets, and the boys learned to shoot.

In the fall, there was the anniversary of the killing of Oleksa Dovbush* (*Oleksa Dovbush b. 1719 in the village of Pechenizhyn, Kolomyia raion. Leader of the Carpathian *opryshky* [outlaws]. Died in 1745. – Ed.). By then, a monument to him had been unveiled in Pechenizhyn. So we prepared a wreath for the Dovbush monument with a blue-and-yellow ribbon. Each person had a specific task: who gets the wreath, who gets the ribbon, who makes the inscription. We planned to write Shevchenko's words on the blue-and-yellow ribbon: “There will be a son, and there will be a mother, and there will be people on the earth.” The blue-and-yellow ribbon was to play the main role: to remind people of our blue-and-yellow flag.

We also planned something with the trident, but it didn’t work out. To draw the trident well, I turned to my landlord, Roman Ryzhko, with whom I was staying then at 54 Prykarpatska Street. He chose the most distinct trident for me from old literature, from old Ukrainian calendars. There were such beautiful tridents there. I copied that trident and decided we needed to make a stamp for the organization. I put this on the agenda for discussion with the boys. The boys said: “Yes, indeed. A stamp—that's for internal use. But if you wrote a leaflet and put the stamp on it—that would influence people.” We decided to make a stamp.

I ordered the blank from a turner—a Muscovite—at that same PMK-67. By the way, that Muscovite figured in the case (*V.S. Mikov – Ed.*). What was it to him—he knew full well what he was making, an old Muscovite, but we gave him a bottle, so for a bottle… He turned a bronze blank for a stamp, traced the lines. It came out a nice blank. Now we just had to find someone who could engrave the inscription “Union of Ukrainian Youth of Halychyna” around the edge and a trident in the center. An engraver can do that. And here we made a big mistake, because engravers, as a rule, are “their” people, from the KGB. One of our wise guys warned me. It was Vasyl Kuzenko, he said: “Don't go, because all these engravers are suspicious people.” But I was still persistent in these matters. I went to the engraver who, I thought, was trustworthy. I got acquainted with him and said I needed an inscription done. He asked what kind of inscription. I showed him the stamp, but I didn't say yet that there should be a trident in the center, because even the word “trident” caused a shock in everyone. He said: “Okay, leave it with me.” I left it.

And he, apparently, took this stamp where it needed to go, and they told him not to let this matter out of his hands until I returned. I analyzed this later and understood how it happened, because he himself became interested: “Oh, why haven't you been by? And what is supposed to go in the middle here?” I said: “Well, you do the inscription, and then they'll tell me. It's not for me.” That was the tactic I chose. He took the stamp and said: “Okay, I'll make this.” I promised: “We will pay you.” And I asked him where he was from and all that. He answered: “I live here in Kolomyia.” We checked, and indeed, he lived in Kolomyia, on Shkriblyaka Street, Taras Stadnychenko, his family was decent: his father was a quite respected figure, from an old Kolomyia family, had a good library.

We decided to meet with him and talk semi-openly. But when I came to ask about the work, he himself said: “A man approached us here. He gave me a *Kobzar* to inscribe: ‘May Ukraine be free!’ I don't know what to do.” He named that man so that I would go to him and start communicating. It was probably a KGB setup. I happened to know this man. He was a taxi driver who worked at the bus station. I told the boys about this, and the boys immediately became suspicious that it was obviously some kind of trap: taxi drivers are unreliable people. I said: “What does this Stadnychenko have to do with him?” “Maybe he doesn't know? After all, he spoke sincerely about the *Kobzar*.”

We considered that this was indeed a well-thought-out trap for us. But we were already caught anyway. Sometime in December 1972, we came to the conclusion that this Taras Stadnychenko was working for the KGB. I called a meeting and said: “What are we going to do? The 'tail' has gotten into our confidence; he's been coming to our meetings. What should we do? I think we need to wind down our activities now.” How to get out of it? We decided to get out of it very simply. To finally test him, Chuprey and I came up with a scheme. At one of the meetings, Chuprey said that a student in his group (and he was the group leader) named Lotov had two pistols at home. Roman had done some work for him and was a welcome guest in this Lotov's Lviv apartment, and Lotov had boasted that his father and grandfather were military men and had exchanged personalized weapons on the front lines. The grandfather was already dead, the pistol was still in the house, but the father was still alive. So there were two pistols. Roman Chuprey looked at those pistols, gasped, came and told me right away. I said: “Roman, I don’t know about gun models. But the small pistol is probably a Browning, and the other one is some other model. We need to carry out an operation. You give me the address, and we’ll go and do it. You won't do it, because you've already been seen there.”

All this was said in Stadnychenko’s presence. When we said this, he obviously reported it to them, and they ordered him: “At all costs, you must be with Hrynkiv when he goes to Lotov’s.” And Stadnychenko began to give himself away with this, because at one of the meetings he was very insistent: “Why haven’t you gotten that weapon yet? It must be in Lotov’s apartment! You have to go and get it! I volunteer to go.” The boys looked at him and later said: “He's suspicious. Why does he want to go?”

Then we did this: we set a date for the operation. It was sometime in February 1973. I told Stadnychenko that he was not included: “I'll go. Me and one other person, and you'll stay here.” “No, I’ll go too!” “No, no, just the two of us. There shouldn't be more than two, God forbid. You wear glasses, you're noticeable.”

And what does he do? On the appointed day, he came to the train station—we weren't there. Then he got on the train, went to Lviv, went to Roman Chuprey’s dormitory and said that Dmytro was supposed to arrive soon. Roman knew it was a test and said: “Well, so what? We'll wait.” They waited all day, but I didn't arrive. A day later, Roman comes to Kolomyia and says: “He's not one of ours. This is trouble! What are we going to do?” We already had a security service. Kuzenko says: “I’ll strangle him. Just let me get my hands on him, I'll...” He declared it just like that. And I said: “Well, if you have such inclinations, that you'd even skin him, what would that look like? I can’t give such a sanction. We don’t know this person completely. We have to make some kind of move to remove him from the organization peacefully.”

We thought and thought and came to the conclusion that we needed to hold a large meeting, inform Stadnychenko as well, but not say anything about the agenda, and at that meeting announce the dissolution of the organization. The rationale would be that we now know the enemy well enough, have studied his methods, know how to fight him, and now everyone will continue on their own, without relying on the organization. It had fulfilled its functions and was self-dissolving.

In early March 1973, we staged the “self-dissolution.” Stadnychenko, obviously, ran straight to the KGB agents, and the KGB agents had no choice but to immediately grab us. They were afraid that after the self-dissolution, they would have nothing to charge us with. I later told the KGB agents: “What, were you scared we would dissolve ourselves?” The KGB agent just exploded. “You were already starting to fall apart. You should have waged war with us subtly—why couldn't you endure?” And they said: “But you had a security service.” As if to needle me. I said: “It wasn't functioning, that security service. If it had been functioning, we would have really messed things up. It hadn't come to that yet.”

The KGB agents made another mistake. A week before the arrest, a member of the organization, Vasyl Mykhailiuk, was summoned to the military commissariat. He worked at the woodworking plant. He was summoned—and disappeared for two days. A frantic Vasyl Kuzenko ran to me: “Do you know that Vasyl Mykhailiuk is gone? He hasn’t come back yet.” “What do you mean, hasn’t come back? He was summoned to the enlistment office. We need to go there and find out.”

This is how it was. They summoned him to the enlistment office and began to accuse him of something, took him to the drunk tank, and there they drew up a report that he was drunk. Before that, some “nice guy” had gotten him drunk, and Vasyl had said: “What’s that enlistment office to me! I just need to fill out some form there.” Of course, an already tipsy Vasyl Mykhailiuk was detained at the enlistment office, and they called the police from the drunk tank. So they took him to the drunk tank, held him for a whole day, and drew up a report there. He worked as a foreman, had graduated from the Lviv Forestry Institute, and valued his career highly. So they showed him: “You see this report? Either you tell us everything about the organization and write a statement—or we’ll send this report to your workplace right now.” Mykhailiuk panicked and wrote down everything he knew. That’s why the prosecutor at the trial had something to say: that the organization was uncovered thanks to the statement of this Vasyl Mykhailiuk. Although in reality, that wasn’t the case. They were just using Mykhailiuk as a cover.

V.O.: And Stadnychenko was supposedly not involved at all!

D.H.: And he was no longer needed. Such interesting nuances. One could write a whole study about this investigation. Well, they had a lot of experience, it was a terrifying organization.

V.O.: Yes, the KGB gained experience by exposing us, and we took our experience with us into captivity and passed it on to no one there.

D.H.: They also took into account how we exposed them. What, did they not discuss how and why we exposed them? Their agent worked too aggressively. He should have worked more subtly. That was their miscalculation. And we, instead of directing our energy toward concrete work, were forced to wage an invisible battle with the KGB's network of agents before our arrest. This went on for the last 3-4 months. But what else could be done?

ARREST

What else did this Stadnychenko do? The day before the search, on March 14, he brought me the stamp blank that we had given him. He had already engraved the inscription “Union of Ukrainian Youth of Halychyna,” but he hadn't made the trident. He says: “You know, the bits are breaking (*shteker*—that’s the name of the drill bit in engraving work). Maybe you know where I can find these bits?” I told him I would ask. He brought me this blank late in the evening, I was sleepy, and he confused me with those bits. The calculation was that I wouldn't have time to take it anywhere, so that it would be in the apartment. They were obviously also watching the house to see if I would go out or not. I took the blank and said: “Alright, just leave it here. We'll find the bits somewhere.” Especially since we already suspected him. I took the blank and put it in a sliding cabinet in the kitchen set. It was wrapped in the same paper on which the inscription “Union of Ukrainian Youth of Halychyna” was written in my handwriting. I put the blank there and thought I would deal with it. And at six in the morning, they were already waking me up, putting me and my wife against the wall. She was pregnant, by the way.

On March 15, 1973, everyone was searched. There were searches at Mykola Motriuk's in the village of Markivka, and at Vasyl Shovkovy's and Dmytro Demydov's in Pechenizhyn. They went to Rivne and conducted a search at Vasyl Ivanovych Hrynkiv's. They traveled everywhere in cars, in “Volgas” from the Ivano-Frankivsk KGB. They even interrogated one of our acquaintances who was serving on a submarine that very day about his connections. How much money must it have taken to conduct such an operation?

Of course, they gathered some information. Someone said something somewhere, someone wrote something down, something was found during a search. For example, at Shovkovy's place, they found a homemade pistol from his childhood. It shot in such a way that it could pierce a board with a nail. It was soldered shut and loaded with sulfur from matches. The barrel was screwed to a wooden handle. The boy had made it for himself back in the 8th or 9th grade—and that was already considered a firearm. They were delighted to have found this weapon.

V.O.: How did it shoot? Was there a hammer, or did you have to light it?

D.H.: No, he made it so that a hammer would strike, and the impact would ignite the sulfur. I never saw that pistol.

But there was another matter. I think it was in the summer of 1972 that we carried out an operation to steal construction pistols from a warehouse. We wanted to modify them so that they could be fired with one hand, because a construction pistol is fired with two hands. It's used to drive in dowels. I had seen these pistols with construction workers, but I couldn't study them properly. So I told Shovkovy about it. Shovkovy says: “You know, maybe they can be converted to be fired with one hand. That's a formidable weapon. You can get charges from construction workers. The barrels, of course, are made at the Tula factory, all of them are manufactured with the same technological process.”

I knew where these pistols were located because we worked at the PMK-67 service yard. So Mykola Motriuk and I stole them one night. Just the day before, we had been moving those pistols. The warehouse manager didn't realize who he was dealing with. We stacked some of the special crates as he ordered, and I discreetly hid a part near the door. I placed it in such a way that the door could be pried open a little to take them. And the doors there were such that the bottom could be easily pried up, because it was a huge gate, those construction warehouses are big. There was a guard, but he knew we were workers. We were boiling tar there. Sometimes we would come to boil tar in the evening or at four in the morning. Who would suspect us? We were workers from that yard. We had access, and on that particular evening, we even had a drink of vodka with the guard. So I went, took the pistols, and gave them to Shovkovy in Pechenizhyn for examination and modification.

When we exposed Stadnychenko, I gave the order to destroy all materials for which we could be arrested. When Mykhailiuk disappeared, we sounded the alarm again. In addition, Shovkovy's mother worked as a cleaning lady at the village council in Pechenizhyn. Some man took her outside and said: “Tell the boys there’s trouble. Have them hide everything.” He said nothing more and disappeared. The mother told Shovkovy, he called me from Kolomyia and asked: “How should we understand this?” And I said: “This is some kind soul trying to save us. That means destroy everything immediately—tapes, any recordings.” We had tape recordings. We had recorded fragments of one of my program speeches that I was preparing to give at a meeting. We erased those recordings. I ordered everyone to conduct a thorough search of their own places to destroy any traces of our activities.

I came home and told my wife that I was going to conduct a search of my own place, just in case. She was frightened and said: “What is this supposed to mean?” “Don’t ask any questions, I have to conduct a search. You will help me.” She followed me around. I checked my briefcase—I used to take a briefcase to work. The briefcase had a flap that covered the bottom. I pulled out a notebook from there. It was my speech. I tore the speech out of the notebook and destroyed it. I found nothing else in the briefcase.

I went on. I found a few such thin booklets. I was sorry to destroy them. I can't say now what they were about. One, very thin, was about Dontsov's nationalism. I also found my notebook—which assignments I had given to whom. And I didn't want to destroy the photographs either. So I carefully wrapped these photographs, two small books, and the notebook in a newspaper and tied it with a ribbon, went to the toilet and said to my wife: “Watch.” We had a metal plate in our toilet's cistern. I pressed on the plate, pushed the package into the cistern, and released the plate. The plate pressed the package tightly. I checked—nothing was visible. By the way, the KGB agents never found this package. When they took me away, my wife threw everything away in a panic and burned the photos, but she saved the books. I told her she shouldn't have burned the photos either, but she—you know how it is—she was hiding it herself. And they came several times and terrorized her. So you can't blame her. And at that time she was pregnant, in her eighth month. She gave birth in April, and this was March.

They burst into the house, put us against the wall... I didn't finish telling you how I did my search. The stamp—oh, what an idiot!—it completely slipped my mind, I didn't hide the stamp! If I had hidden the stamp—they wouldn't have found anything. And that stamp was important to them—it was a sign of an organization. I had gone into the kitchen—it seemed there was nothing in the kitchen. But I left the stamp in the kitchen! I was so pleased with my search, and wanted to find out how the other boys had done theirs. I asked one—he had done everything. Shovkovy said he had taken the construction pistols to the school toilet. There’s a huge pit in the toilet at the middle school. He threw the construction pistols into that pit. But he didn’t throw away his homemade pistol, and they found it. How things happen! And so they found a little something on everyone. At Motriuk's place, they found a few cartridges that he didn't even know about, from a "TT" pistol, and there were also some from a "PPSh" submachine gun. We have a lot of such cartridges in our villages, bullets in workshops. And his father was a blacksmith. They recorded that in the protocol too.

They found 600 small-caliber cartridges at my place. I didn't know what to do with them. I thought they wouldn't do me any harm, since I didn't have a weapon. Oh, but we did have weapons. I had a small-caliber rifle that I kept in a hiding place at work. I made the hiding place in the locker room. During one operation, we got a Mauser-system carbine. It's a rather interesting carbine, very rare, German. Dmytro Demydov, while talking to a friend from his studies, a Czech by nationality, who lived next door, found out that his father had several carbines. One carbine was stored by the seat under the toilet. There was a hiding place underneath, where you sit down. He showed him all this, and Demydov remembered it and told me. I went there at night with Shovkovy. Shovkovy distracted the dog while I went into the toilet and felt around in the dark. There was indeed a carbine, with 40 German cartridges for it. A Mauser-system carbine, its receiver could be unscrewed, so it was small if you took it apart and hung it around your neck, you couldn't see anything, you could hide it under a jacket.

So we had such a carbine. I also hid it in a hiding place at work. Motriuk, with whom I worked, asked what we were going to do with this weapon in the hiding place. We stood there, as if spellbound: what to do with this weapon? I said: “First, let’s analyze who knows about this weapon.” It turned out that many people knew, even Stadnychenko knew. The fact is that Shovkovy took this carbine to the mountains when he went on a trip in December with the other Chuprey, Liubomyr, also a member of the organization. They had seen bear tracks somewhere on Mount Syvulia in the Nadvirna district. He even had this carbine with him at the police station—they became suspicious about why they were sitting at the bus station in Nadvirna so late and took them to the police station. They didn't look in their backpacks, and this carbine was in the backpack. Shovkovy had a close call with that carbine, he said: “We could have been caught with it even earlier.” If the police had found the carbine, they would have “unraveled” us back then. Although we trusted these guys, I decided that the weapon would remain in this hiding place for the time being.

So, Kuzenko, Shovkovy, and Stadnychenko knew that there was a hiding place somewhere at work. But they didn't know exactly where. So we thought we should take the weapon from the hiding place. But we didn't have time. And the KGB, after the “dissolution” of the organization, was already watching us, what we were doing.

During the search, the investigator, Major Rudyi, took that stamp and said: “Well-l-l...,” he drew out the word so meaningfully. From his voice, I understood that this stamp was what interested them. “Oh, so this is something!”

They conducted a thorough search and found in my briefcase, which I had checked myself, in that hidden compartment, a thin sheet of paper on which an assignment for one of our boys was written! He just hadn't been at the meeting, and there was no way to pass it to him, so it remained in the briefcase. I was very surprised, because I had conducted the search myself.

V.O.: You are not a professional at searches.

D.H.: Not a professional. The bottom was covered by a bar—I didn't lift that bar, and then I was surprised at how they found it. And that got to me a little. But what I had hidden, they didn't find. Well, I thought, not yet knowing that searches were being conducted at everyone's place, at least that’s good—they don’t have photographs, so I'll take everything on myself to shield the others.

They took those 600 cartridges, the targets. I explained that I conducted shooting practice at DOSAAF, so to avoid getting cartridges too often, I took them home and issued them personally. They didn't find any weapons at home.

Then they took me to work for a search. Obviously, they knew. I figured it out then: I didn't show them the spot in the locker room or my specific work area, but led them to the general locker room, counting on the fact that they wouldn't ask the supervisors where I changed. Because our supervisors were decent people. When I saw the "Volga" arrive with me and two agents and one approached the chief mechanic, Filipchuk, and said they needed to conduct a search of Hrynkiv's things, he understood something was wrong. I just motioned to him with my head: say nothing, I'll show them myself. The KGB agent asked Filipchuk: “Does he change here?” “I don't keep track, everyone changes here.” I thought: thank you, Lord. He's a good man. He knows I work in a different area, but he doesn't specify, and they don't ask for specifics. “Well, go on.” They let him go and started searching the locker. They ask: “Are these your pants?” “Mine.” And the jacket, I say, is also mine. He reached into the pocket—and pulled out the ID of a mechanic named Macherniuk and said to the other agent: “How can this be? He changes here, but here’s Macherniuk's ID?” I said, the mechanics also change here. The man nodded his head: “Well, alright.” They found nothing and waved their hands in dismissal.

We got into the “Volga”—and they took me to the KGB. They brought me in, and there the agents laid their cards on the table: “And where is your carbine and your small-caliber rifle?” “Ah, so you already know about that too? Well, since you know...”

V.O.: Did you think that or say it?

D.H.: No, no, I said it just like that: “Aha, so you already know about that too?” He said it straight to my face. So what, what if I had said I didn't have it? He said: “No, it won’t do you any good to delay. We know they are hidden somewhere at your workplace.” So I thought, they’ll bring that Stadnychenko or someone else—what's the difference? I didn’t want the guys to have trouble because of this, so I said the weapons were mine. He said: “Let them be yours, but show us.” We got into the “Volga,” and they brought me to the place. I had to climb some stairs to get up there, so one of them had to rush ahead, afraid that if I climbed up first, I might grab the weapon and do something. They were extremely cautious. They shooed away the curious onlookers, as people had already seen what was happening and understood that something was wrong, and they were already murmuring about it.

I also lied, saying I needed to tell my wife something because she wouldn't tell them herself. But actually, I wanted them to take me to my wife so I could tell her Motriuk's last name, so he could get the weapon out. They figured out I was lying and didn't take me home, but went straight to my workplace. Although my wife, when they were taking me from the house, asked: “Are you taking him for long?” He said: “Yes, for a long time.” She started crying, and I told her not to cry and to go to Motriuk. The poor thing understood and rushed to go to Pechenizhyn to see Motriuk. But it turned out there was a search there too. She met someone in town and realized that there were searches everywhere. Shovkovy's mother came and said there was a search there too. It was already the second half of the day. Everything became clear.

INVESTIGATION AND TRIAL

After I handed over the weapon, they took me to Frankivsk in the evening. I was held there in a pre-trial detention cell at the KGB. They threw some kind of “hanger-on” in with me. He was trying to get information about everything, so I told him I was a simple guy, arrested for poaching, they found a weapon, an old carbine. He said that was nothing, because they found a machine gun on one guy. Well, it was clear he was one of their men, because he started sniffing around to see if I had anything else. He said I'd get out, because it was all nonsense: good people always have something put away. I already understood he was a cell-plant, and I kept telling him it was poaching, not politics.

The next day I was called in, and they began to present charges under Article 56. Actually, the prosecutor’s sanction had been read to me back at home. I said: “Explain this article to me.” He said: “You are charged under Article 56, ‘Treason against the Motherland,’ from 10 to 15 years or the death penalty.” I'm a very direct person, and after a few days of investigation, I asked: “How should I understand this Article 56? If I am the leader of the organization—then leaders get the maximum, and you see what the maximum is here?” He looked at me and said: “Well, you think about it, think about it.”

In short, they charged five of us under this article. Roman Chuprey, however, was arrested in Lviv two days later. That means they still had hopes of winning Chuprey over to their side, they were still hesitating whether to imprison him or not. He spent the night on a sofa somewhere in their office as a detainee. Dmytro Demydov was taken in even later. They couldn't get anything out of him and let him go. And they wanted to leave it at that, but he started incriminating himself because he began to feel unwell, and people started saying: “Well, how is it that they are in prison, and you are not?” This prompted him to the point where he almost went to the KGB himself and started saying: “Arrest me, take me, I'm the same, I'm for Ukraine.” He said a lot against himself and breathed a sigh of relief. And the investigator wrote it down in the protocol: “Stay put!” Such an interesting nuance with Demydov. He said a lot about himself that wasn't even true—to add weight to his person in this group. But what happened, happened, and what didn't happen—didn't. During the investigation, they didn't really try to find out: if he said it, then thank God, because it was convenient for them.

They conducted the investigation in such a way that no violence was used in the office. Those methods were used in the cells. Demydov was beaten by someone in the cell. The one who was planted with him beat his head against the wall. Demydov was screaming in there. They put two people in with me, one of whom was a homosexual, and the other was an artist who loved to draw Lenin in various poses. He drew so many Lenins that he drove me to the brink, and I told him off: “Is that all you've learned to do, can't you do something else?” He kept telling me how he drew the coats of arms of the union republics, what they were like. I wondered what they were trying to achieve with this? They were obviously studying my attitude towards all things Soviet. I held on for as long as I could, but then he annoyed me so much that I started to condemn Lenin and almost sent the artist packing, told him to get out of the cell, because I would... “You and your Lenin—you’re an eyesore, drawing that satrap here!” In short, I told him what I thought. He was immediately taken out of the cell, supposedly because we couldn't get along. But I understood that he was performing some function.

The second one's functions were something else. This homosexual. He was taking some towel at night, I woke up and said: “What are you doing? Are you not normal or what?” I couldn't understand—was it just to have a conflict with him. And then, I hear shouting from other cells that so-and-so is a *suka* [bitch], he’s a snitch. I ask: “Is that not about you?” He hemmed and hawed, they took me out for a walk, and he said he wasn't going. And when I came back from the walk, he was gone. They had their own methods there.

These were the kinds of clashes in the cell. They understood that I could defend myself and raise a big fuss, so they didn't try to break me physically. They physically took their revenge on Demydov—he was weak, so they found someone, and that person beat him.

There was one guy, taken from the army. He jumped on me, so I grabbed the teapot—they had such heavy teapots there—and hit him with it so hard that he jumped back. He was a big guy, he kicked me so that I flew back, but that teapot saved me, because I made such a racket with that teapot that the corridor guards rushed in and threw him out. Maybe there was some intention there too, because why did they put me with him? He was some kind of thief, talking nonsense about his case being related to weapons. Probably to get me to talk.

I made some mistakes with another “plant.” A skinhead, came from a labor camp. He was supposedly about to be released, but they “cracked” him for some buried weapon. He was from the village of Zhovten, now Yezupil near Frankivsk. That was his cover story, he kept repeating it to me, and then he said: “If you had a weapon, you need to go abroad.” He was trying to steer the conversation in that direction. I watched him closely: it turned out he prayed in the mornings because he saw that I prayed. Apparently, he had the task of praying with me. When I started the “Our Father” in the morning, he would also start to pray. And one morning, he wasn't praying. I asked him: “Why don't you want to? You were praying.” When I returned from my walk (because they always did things during the walk)—he was gone. They obviously realized that I had exposed him, and it was no longer expedient for him to have contact with me.

Such were the twists and turns during the investigation. And during the investigation, I took everything on myself. Where is the pistol? “I took it, and no one else.” Motriuk remained silent, so everything was fine. During the investigation, I figured out that if I did something with one other person and took the blame, and the other person said nothing, they couldn't prove it. But if three of us knew, the investigation would unravel it.

They carried out an operation at Lotov's place, took those two pistols, photographed them, and attached them to my case. “And what do these pistols, the Browning and the Walther, have to do with my case?” “Well, you wanted to carry out such an operation, didn't you?” “Yes, we wanted to, but we didn't do it. I only saw them in a photograph.” “But it's connected to your case, you uncovered them.” “So make a separate case out of it, as if we helped you uncover trophy weapons at the Lotovs'.”

I could have argued strongly with them, but at the time I was completely legally blind: they were so calmly twisting us with this Article 56. They kept us like that until May, and in May they said: “Your article has been changed: you are charged under Articles 62, part one—‘anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda,’ 64—‘creation of an organization,’ 223—‘theft of weapons,’ part two, 86—‘theft of socialist property’ (this was for the construction pistols), and 141—they accused us of stealing a tape recorder in Kolomyia from Khmelevskyi. So I had a whole set, 5 articles. On aggregate, according to Article 41, I was convicted on political grounds, Articles 62, part 1, and 64, for anti-Soviet activities aimed at separating Ukraine from the USSR.

They asked why we wanted a free Ukraine, what that would give us. The boys explained that today Ukraine has no army of its own, no currency of its own, no language of its own, that there is such great Russification. But Ukraine has representation in the UN. But it is such representation that it must be subordinate to the Union. They were also interested: “Do you think there are other youth or student organizations in Ukraine?” I answered that there are probably students in every educational institution in Ukraine who think as we do. They meticulously wrote this down. Obviously, they analyzed our answers later. They asked if we had any connections with them. They were very persistent about connections. I said I had not made any connections, that I only got information from radio broadcasts. They asked: “Who brainwashed you into thinking that Alla Horska* was killed by the KGB?” I said, it was on the radio. I told them that now that they had arrested me, the very next day “Voice of America” reported on our group—which means someone from your offices passed it on to them. He looked at me—it's as clear as day that few people knew about our group, and a broadcast was made immediately, all over Kolomyia people were listening about the arrest of the “Union of Ukrainian Youth of Halychyna.” The name of the organization and the last names, all clearly stated. That means this information could only have come from there, from them—someone there was sympathetic to us.

They were also very persistent in asking me: “Who warned you that you gave the order to hide everything?” They were desperately looking for the person who had warned us. It bothered them a lot. I replied that I couldn’t explain it, because I genuinely didn't know.

V.O.: And do you really not know, or could someone from your circle have indeed reported it to Radio Liberty? Was there no one like that?

D.H.: Of course not. I told them: “It was your side that did it.” They were very surprised and angry. Such debates often arose. We're talking, after all, you can't just stay silent the whole time, it's a long story.

Oh, in the cell (this was done on purpose—I realized it later) they kept me in solitary. It was cell 95, where Myroslav Symchych* had also been held. (*A new case against M. Symchych was initiated on January 28, 1968, and lasted 25 months and 13 days. – Ed.) There, “Symchych” was carved into the board. He had been there before us. But I didn't know who that person was. They scrape off all the inscriptions, but this one was carved on the side of the bunk. I learned about Symchych later, but he had been in the same cell on the 4th floor, cell 95.

Meanwhile, I would stand on the window ledge and look through those “bayans”* (*“Bayans” – additional wooden shutters on prison windows: slats placed at an angle so one could only see up, not down or straight ahead), and I could see some of the walking yards. One time I saw Chuprey in one of those yards. I stuck my hand through the “bayans” and shouted as loud as I could: “Roman! I'm here!” He looked at the windows, and I showed him with my hand. I look—and he points with his finger that he is lower. Aha. And just then the doors open, because the corridor guards heard, and the guard from the watchtower had called them. The guards rush in, pull me away from the window: “What do you think you’re doing?! To the punishment cell with him!” And they attacked me fiercely. I play the simpleton and say: “What—I saw a colleague here. Not seeing a person for so long—what’s wrong with you!” “You are violating the rules! You signed that you would not violate the rules!” “Where did I sign that?” I did indeed sign it, but I said it to him like that.

My investigator finds out about this. He calls me in and says: “You are misbehaving in there. We are not responsible for what the prison administration does.” He's also playing dumb. Of course you are responsible, good people, where do you think you are! It was self-evident, but that was the game. Roman is sitting below. We communicated through a cup, he says we need to lower a “horse”* (*A string that is cast from a window to another cell to pass a note, object, food, or tobacco).