Vasyl Ovsiienko: On March 21, 2000, in the village of Pechenizhyn, we are speaking with Mr. Vasyl Shovkovyi at his home. He is called Vasyl, but according to his documents, his name is Ivan. Mykola Motriuk* is also present. (Information about some of the individuals mentioned in the interview, and other terms, are provided at the end in alphabetical order. - Ed.).

Vasyl-Ivan Shovkovyi: I was born on July 7, 1950, in the village of Pechenizhyn. At the time, it was the Pechenizhyn Raion, but now it’s the Kolomyia Raion. In 1957, I started school but didn't finish it because, after the ninth grade, in 1965, I went to Chernivtsi and enrolled in a vocational school to become a cabinetmaker and furniture restorer, which I completed. I also finished evening school there, eleven grades, and was admitted to the evening department of the industrial technical college. I didn’t finish that either, because the army got in the way. I was drafted in the fall of 1969. I served for two years. Half a year in training camps in Crimea, in Yevpatoria (air defense, missile forces), and a year and a half in the Lviv Oblast, in Pustomyty.

After the army, I returned to Chernivtsi. They didn’t want to register my residence there. The runaround began: there was work, but no residence permit; there was a residence permit, but no work. So I returned home to Pechenizhyn. For almost half a year, from fall until spring, I looked for a job. I finally got a job at the DOS (Kolomyia Woodworking Plant) and worked there practically until my arrest.

V.O.: And who were your parents?

V-I.Sh.: My mother was Yevdokia Mykolaiivna Shovkova, née Pnivchuk. She was born in 1927 and died in 1993. My father was Vasyl Ivanovych Shovkovyi, born in 1921, and he died in 1988. My father was a war veteran, severely wounded. They were driven, literally unarmed, to force the Oder river. A great many of them died there. If he hadn't known Polish, he probably would have remained there. But they were advancing together with a Polish battalion, so Polish medics would ask who was Polish. And whoever knew Polish was picked up. That's how it was.

I have a sister, now Liuba Vasylivna Chuprei, born in 1959. I also have female cousins, but only one full sister.

V.O.: Before you talk about your arrest, think back—what influenced the formation of your national consciousness?

V-I.Sh.: It was a natural environment here. There was an echo of the old partisan resistance. Our generation basically grew up on that, although it wasn't spoken about in school.

M. Motriuk: Well, what about your father’s sister?

V-I.Sh.: For a time, my father’s sister was a courier for the UPA partisans. I can't say she told me a lot about it. But other people did, here and there. There were many sources of such information.

V.O.: The boys said that you regularly listened to Radio Liberty and were a radio enthusiast.

V-I.Sh.: Well, what kind of radio enthusiast? I repaired radio equipment. If you can call that being a radio enthusiast, then yes. There were some courses or a club for it in school. A lot of boys were into it. You could say it gave me another profession to some extent.

I remember the radio broadcasts about the arrest of Valentyn Moroz on June 1, 1970, and about the arrests on January 12, 1972*. We heard about it on the radio; there was a lot of talk about it then. And about the Russian dissidents, in particular, Vladimir Bukovsky*. I told the boys about it, and we shared our impressions. Our organization didn't emerge from a vacuum.

One evening, about six of us boys gathered at my place. This was after the January 12 arrests, sometime near the end of January, because the students had just come home for their break.

V.O.: Dmytro Demydiv names the exact date: January 31. And who was the initiator of the meeting?

V-I.Sh.: I wouldn't say anyone was the initiator; it all just came about on its own. It was hanging in the air. The initiative was roughly the same for everyone. Well, Dmytro Hrynkiv formalized it.

V.O.: Did this conversation take place in this room and at this very table?

V-I.Sh.: No, this is a new table, but it’s in the same spot. We did it, perhaps, on a childish level; some things were a bit naive...

V.O.: But with elements of ceremony?

V-I.Sh.: Yes. That there was. We adopted the form of the OUN underground, using pseudonyms.

V.O.: Did everyone choose their own?

V-I.Sh.: Yes. I don’t even remember who called themselves what. We met many times. But we wanted to get in touch with someone, to get some information and to be able to pass something on ourselves. At that time, we heard that the *Ukrainian Herald** was being published and that there was samvydav literature. That interested us more.

V.O.: Did you have access to samvydav?

V-I.Sh.: Only through the radio. At our meetings, Dmytro Hrynkiv did most of the talking. He would say: “We need to do something too. Look how many guys have gone.” He meant those arrested in Lviv and Kyiv. Then everyone would add something of their own. I talked about the latest arrests because I was listening to the radio more at the time and was up to date on the issue.

V.O.: And then Dmytro Hrynkiv took a knife and slammed it into the table, and everyone put their hands on the hilt... That's what he said.

V-I.Sh.: That was for the sake of ceremony. It happened during a symbolic feast. We sat, talked, and then went our separate ways. It lasted about an hour.

V.O.: And responsibilities were assigned then?

V-I.Sh.: That came later, when we gathered on May 1 at Dmytro Demydiv’s house. Dmytro Hrynkiv brought a small-caliber rifle—he got it from the DOSAAF*. After that, we shot at Dmytro’s door.

V.O.: You shot at it? What if someone had been walking by?

V-I.Sh.: No one was walking there. The house was still unfinished. At midnight, we took a wreath with yellow-and-blue ribbons to Dovbush’s monument. Then we dispersed.

V.O.: And what duties were assigned to you in the organization?

V-I.Sh.: We wanted to create our own security service. But that wasn’t serious at the time because we had nothing to do it with. Dmytro Demydiv later argued that we should have done it right away. We had already gotten a carbine from Zumer, and a small-caliber rifle from the school. We also officially took small-caliber pistols from the DOSAAF, because we were registered with them and went target shooting. We went to the forest once to shoot that old carbine. Dmytro Hrynkiv was the head of the DOSAAF in his organization and had access to weapons. He got cartridges through that organization. I know that they confiscated a lot of cartridges from him during his arrest.

V.O.: He said about six hundred.

V-I.Sh.: If not two thousand. Because DOSAAF members were supposed to shoot them. The cartridges were supposed to be kept somewhere in a safe at the organization. But he had all of it at home or in a storeroom at work. There at his workplace, in the changing room, he had some kind of hiding place where he kept a small-caliber rifle and cartridges. The carbine was there too. And there were cartridges at home.

V.O.: And what did you have?

V-I.Sh.: I had a handleless homemade gun. I had made it back in about the fourth or fifth grade.

V.O.: So that’s when you "embarked on the criminal path"! I wonder how that gun was made? Was it a flintlock, or did it have a firing pin?

V-I.Sh.: It was made with a firing pin. It was a piece of a rifle barrel, drilled out like a medieval revolver or pistol. It was loaded simply from the barrel, from the top. A hole was drilled here, and a piece of an oil can was screwed on. A shotgun primer was placed there. And there was a firing pin. My homemade gun would fire every other time, or every third time—it was hit or miss (laughs). It sat in my desk drawer like a museum exhibit for maybe ten years. The handle was broken off. Nobody needed it.

V.O.: But the KGB needed it!

V-I.Sh.: Yes. That was the main charge against me: manufacturing and possession of a firearm.

V.O.: But you were still a minor when you made it, weren't you? They should have charged you for possession, but probably not for manufacturing?

V-I.Sh.: There are articles for both manufacturing and possession, 222 and 223.

V.O.: You were all accused of anti-Soviet agitation. How was this agitation conducted? Was it just conversations among yourselves?

V-I.Sh.: Almost, yes, it was conversations among ourselves. What we read, what we heard. I personally read the memoirs of General Shukhevych about those winter campaigns to Kyiv, Odesa, and Fastiv. It was a book from the “Chervona Kalyna” publishing house*. (*This most likely refers to the memoirs of General-Khorunzhy Yurko Tiutiunnyk about the Second Winter Campaign of 1921, and its defeat near Bazar by H. Kotovsky. His most famous book is "With the Poles Against Ukraine," published in October 1924. — Ed.)

V.O.: But they didn't find that book on you?

V-I.Sh.: I borrowed it from Dmytro Hrynkiv. Vasyl Kuzenko got us most of these kinds of books. We had a second-hand bookseller who collected old books. We got them from him. Not directly, but through someone. He wouldn't have given them to us otherwise. We returned them. I don't know the fate of that book. Mostly, our “agitation and propaganda” was passing on news from foreign radio stations. For that, I modified a radio to pick up the 19-meter band. Back then, the 19-meter band wasn't jammed, so I could find out more.

V.O.: And shortly before the arrests, you became aware that something was being prepared against you, and then Dmytro Hrynkiv gave the order to destroy or hide everything, even to search your own homes. What triggered this alarm?

V-I.Sh.: How it happened was, my mother's teachers told her: “Something is wrong with your son, watch out, the KGB is interested in him.” Then at work, they demanded my passport and military ID for some reason. They never returned the military ID. That was the personnel department. Why did they need it so urgently? I was on vacation just before the arrest.

V.O.: Did you suspect any of your colleagues?

V-I.Sh.: Dmytro had accepted a guy who turned us in.

V.O.: Can you name him?

V-I.Sh.: Stadnychenko. I met him a few times. He worked as an engraver in the department store in Kolomyia.

V.O.: Was he the one who offered to make the organization's seal?

V-I.Sh.: Yes, yes.

V.O.: Dmytro Hrynkiv said he brought him the seal, still unfinished, on the eve of the arrest, and Dmytro didn't hide it.

V-I.Sh.: If you can call a piece of bronze a seal... It was just a blank. It wasn't a seal yet. Just a piece of bronze. Dmytro gave a lathe operator five rubles for it.

V.O.: But it figured in the case as a seal. And a seal is a sign of an organization.

V-I.Sh.: For credibility's sake.

V.O.: Under Soviet law, intent was classified and punished just like the crime itself.

V-I.Sh.: Maybe even worse. And you could feel it. At work, they started taking a very particular interest in us. Vasyl Mykhailiuk disappeared very suspiciously. We were on close terms, worked together at the woodworking plant. We traveled to work together. He didn't know everything, but he knew something about the organization. There was a guy here named Bondarenko—he has since moved to Russia. He got Mykhailiuk drunk somewhere, and they took him to the sobering-up station. He stayed there for a week. They released him right when we were arrested.

Well, I don't think he could have given the whole picture, because he couldn't have known certain details. But the KGB knew practically everything. There was someone closer, this Taras Stadnychenko; he knew almost everything. He met with Dmytro Hrynkiv every day in Kolomyia.

V.O.: Dmytro said something interesting: that during this alert, a meeting was called and it was fictitiously announced that the organization was supposedly disbanding itself. This was a charade specifically for this Stadnychenko.

V-I.Sh.: Perhaps that's what expedited the arrests.

V.O.: Because the KGB got worried that the organization would disappear. They had to arrest them immediately, while it still existed.

V-I.Sh.: I don't remember who was the first secretary of the Ivano-Frankivsk regional committee of the CPU at the time; I think it was Dobryk. Dmytro Hrynkiv has a letter from Dobryk to Shcherbytsky, dated March 14 (and we were arrested on the 15th), stating that such-and-such nationalist group had been exposed. Dmytro has it in an official book.

V.O.: I have a report from V. Shcherbytsky to the Central Committee of the CPSU dated August 27, 1973. It discusses the conviction of your "Union of Ukrainian Youth of Galicia" and the group from the village of Rosokhach, which raised blue-and-yellow flags over Chortkiv on the night of January 22, the 50th anniversary of Independence.

V-I.Sh.: And this letter is dated March 14. We were arrested on March 15, and the description to Shcherbytsky already says the group was arrested. The day before. So they knew everything perfectly well.

V.O.: How exactly were you detained? The circumstances themselves are interesting.

V-I.Sh.: It was March 15, a Thursday (I remember that well), 1973.

Remark by M. Motriuk: We were at my place on the 14th, fixing a radio.

V-I.Sh.: Right. We were fixing the radio. The next day, it was about six o’clock. Major Rudyi showed up. I don't know what rank Honcharenko held. Those were the two main ones. Major Rudyi conducted the investigation, and this Honcharenko was always in civilian clothes, so I don't know his rank. He was from the Kolomyia GB. And this investigator Rudyi was from the Frankivsk one, from the regional administration.

They immediately made a beeline for the desk drawer. "Oh, look what we found!" Who were the witnesses? M. I. Pertsovych, he was a surgeon, a wonderful person. Unfortunately, he's already passed away. He was called out somewhere, and these GB agents turned him back. It didn't matter if someone was sick or dying; this was more important—they had to make an arrest here.

And it began: "What do you have? A tape recorder? Show me immediately. Weapons? Anti-Soviet literature? Lay it out!" "What weapons do I have? I have nothing like that." Well, they immediately found the homemade gun in the drawer. I didn't have a tape recorder. Hrynkiv had one.

V.O.: They knew where to look and what to look for.

V-I.Sh.: Yes, that's clear! They took the homemade gun from me and, actually, nothing else. Oh, I also had a roll of film with our pictures on it. They searched me. I somehow managed to get that film out of my pocket and held it in my fist. So I brought it all the way to the Frankivsk GB headquarters and threw it in the toilet there. I managed to do that.

V.O.: And what was on that film?

V-I.Sh.: We were photographed on that film. I think with the carbine. There was one such shot... Kuzenko and I were supposed to develop that photo. I snatched that film...

V.O.: But they conducted a personal search on you at home, didn't they?

V-I.Sh.: They did. But they didn’t make me undress. And I managed, with a deft movement, to toss the film from hand to hand. And I managed to throw it away all the way in Frankivsk.

V.O.: Because there was no other opportunity?

V-I.Sh.: I couldn’t throw it out at all because they were following me everywhere.

V.O.: But the house was full of them, right?

V-I.Sh.: There were the two witnesses and, I think, three GB agents. But there were a lot of them here because they were conducting searches at everyone's places simultaneously.

V.O.: It was a grand operation. Searches and arrests in so many places! All the GB forces were thrown onto the front lines.

V-I.Sh.: They also took a whole bag of various radio parts from me. There was a receiver and, of course, a low-frequency amplifier I had made. They later called in an expert to turn on that amplifier (almost half a watt). We just laughed at the whole thing. They wrote such things that I didn't even sign the expert report. And I shamed them: "Are you people serious...?"

For three days, they didn't take me to the prison in Ivano-Frankivsk but held me like those 15-day detainees. But separate from them. In a pretrial detention cell. After two days, on the third day, they transferred me to the Ivano-Frankivsk prison.

V.O.: How did you take this arrest?

V-I.Sh.: Maybe some defense mechanism kicked in. For about a week, it felt like a dream. As if it wasn’t happening to me. I wasn’t even processing it all... At the first interrogation, I found out they knew everything. But I didn’t know who was arrested. I knew about Dmytro Hrynkiv. But I didn’t know about anyone else. Not until they threw me into a cell from which I could see who was being led out for interrogation at the KGB. In Ivano-Frankivsk, the prison and the KGB building are next to each other. They would take prisoners from the prison to the KGB for interrogation.

V.O.: Could you see from there?

V-I.Sh.: No, you couldn't see. I found a one-kopeck coin in my pocket and remembered chemistry from school. In prison, they give you salt and sprat. I stuck the coin to the bars, which were made of thin strips of metal, with bread. It was already rusty, and I attached the coin with salt, and it rusted through so that a hole a little bigger than three millimeters appeared. Through it, I could see who was passing by. I had a clear view of the gate in the wall between the prison and the KGB. They are right next to each other. I watched: there, they brought him, Mykola Motriuk, in, then Roman Chuprei. Dmytro Demydiv didn't appear for a long time. I shouted once in there, and they immediately took me out of that cell. They said: “Aha, so you know who’s here!” “I know.” “That’s very interesting.”

From March 15 until almost the end of April, they kept me in solitary confinement. I don’t know, maybe they were able to influence me with some clever tricks, because I was in such a depressed state, I was walking around like a poisoned fly.

When they moved me to another cell, they threw someone in there with me. Well, it was clear he was one of their agents. He was talking some nonsense... But at least there was someone to talk to. He was very curious: what about this, what about that? It ended with me slamming him against the bars, and they took him away from me. He started getting too curious. After that, they moved me from cell to cell. It was easier there. Because at first, they charged us with Article 56—"treason against the Motherland." That carried a sentence of ten to fifteen years. But halfway through the investigation, they changed it to Article 62. And that was up to seven years, so I cheered up. Well, it'll be five years, at least not ten.

V.O.: Did they subject anyone to a psychiatric evaluation? At that time, almost everyone accused of anti-Soviet activities was put through an evaluation. Meaning, they threatened them with psychiatric reprisal.

V-I.Sh.: No. It was after my release, when I had some ceremonies with them here (they kept me under administrative supervision for three years), that they told me: “It would have been better if we hadn't imprisoned you, but just scared you really good. That would have had a much greater effect.”

The investigation lasted for half a year. The trial was in early August; the verdict was delivered on the 9th. They gave us lawyers with Russian surnames. My investigator was Major Rudoi, and my lawyer was Suslov.

M. Motriuk: Mine was Sanko.

V-I.Sh.: And Roman Chuprei’s was Andrusiv. He's a local GB agent. I met that investigator, Andrusiv, when they wanted to bring me in as a witness in the case of Valeriy Marchenko*. Because I was involved in writing in the zone. For a while, I even kept a chronicle of the 35th zone...

So, our trial was in early August 1973. They kept us in prison until mid-October, until they gathered a transport. In the Kharkiv prison, on Kholodna Hora, we met up—Mykola Motriuk, Dmytro Demydiv, Roman Chuprei, Dmytro Hrynkiv—and we met Zorian Popadiuk* and Liubomyr Starosolskyi*. There were two of them, and they put us in the same cell, and we traveled together to Mordovia. They were taken off there.

V.O.: At the Ruzaevka station or in Potma?

V-I.Sh.: I don't know how they transported us; it was through the lowlands, below the Moscow Oblast. We were being taken to the Urals, and they were dropped off closer by.

In Sverdlovsk... No, it was already in Perm when we arrived on November 7. Almost a month had passed. The impressions of the transport are very colorful: we were robbed, we got into fights. All sorts of things happened there.

V.O.: But you were traveling as a group, right?

V-I.Sh.: Yes, as a group. Me, Mykola Motriuk, Dmytro Demydiv, Roman Chuprei, Dmytro Hrynkiv. But you can imagine: a cell for about two hundred men. Even as a group, you couldn’t do anything.

V.O.: Weren't you kept separate from the common criminals?

V-I.Sh.: They would bring us and throw us all in together. For example, when I was returning from the Urals, I spent a day with minors. That was very good because at least I ate normally there.

In the Perm prison, we were still held with our co-defendants, but separately from the common criminals. The prison warden himself brought us a letter from Dziuba. He said: “Look at this!”

V.O.: Was this the “penitential” statement by Ivan Dziuba*, published on November 9, 1973, in the newspaper *Literaturna Ukraina*?

V-I.Sh.: Yes, yes. It was around the middle of November. I don’t remember if it was the newspaper or a reprint from the newspaper. It seems photocopies didn't exist back then.

V.O.: There was already a machine that made copies back then, called the “Era.” The KGB kept a very close watch on those machines.

V-I.Sh.: Well, maybe the KGB had one. It seems they didn't give us the newspaper version, but a separate sheet. The prison warden himself brought it.

V.O.: The head of the investigative prison, Lieutenant Colonel Sapozhnikov, brought it to me too, but that was back in Kyiv, at 33 Volodymyrska Street.

V-I.Sh.: Then they took Mykola Motriuk, Roman Chuprei, and Dmytro Hrynkiv from Perm about a week earlier. And before that, they tried to recruit all of us there, openly, in plain text. There was a Latvian KGB operative named Kronbergs. He said directly: “You need to cooperate.” I replied: “I'll think about it.” So I was thinking...

V.O.: For five years?

V-I.Sh.: No, when I arrived in the zone and the guys took me under their wing, Captain Utyro said to me after about a month: “Well, I suppose there’s no point in asking you about that conversation in the Perm prison.” I said: “God forbid, there were no conversations.” “Well, don’t tell anyone.” “I already told everyone long ago how you tried to recruit me to your side.” “Well, alright,” he says.

In the 35th zone, at Vsekhsvyatskaya station, we were met by Vasyl Pidhorodetskyi*; you know him.

V.O.: Yes, yes. I just visited him in Lviv on January 21. He’s in good spirits, as the holidays were just ending.

V-I.Sh.: The main thing is that he’s cheerful. He never got discouraged. In the zone, he was a barber. So after the transport, we needed a shave, a haircut, everything as it should be. He asks Dmytro Demydiv: “How many years?” “Five.” “Ah,” he laughs, “I have twenty-eight...” That’s how he greeted us.

There was something like a quarantine for a few days. Then they brought in Mykola Marmus* and his brother Volodia Marmus*—they were from the Rosokhach group. So, there were four of us brought into the zone. We were met by Mykola Horbal* and... Who was the second one? I don’t remember anymore. One of the old-timers... And standing at the door of the barracks is Vladimir Bukovsky*. I say: “That’s a familiar name... Just before my arrest, I heard about you on the ‘enemy voices.’” He laughed. That's how we met. Then they gave us a warm welcome, with tea. Tea was mandatory. The KGB agents had warned us: God forbid you drink tea, it will ruin your heart.

V.O.: There were such superstitions.

V-I.Sh.: Yes. Right away, the next day, it was off to work. It was mostly metalworking there. They taught me to be a lathe operator. That became my main profession. Although I had studied it a bit before and had some idea about lathe work, I learned more there.

We didn’t know many things, so we learned. Then December 10 came around, the day of the UN Declaration of Human Rights. We had to write a petition. I say: “I have absolutely no idea, explain to me what’s what.” Ivan Kandyba* came down on me for not writing a petition. Someone else said: “Mr. Ivan, you should have at least explained what’s what. Why are you flustering the young ones like that right away?” Well, and then it started. In the spring of 1974, there was a hunger strike. It started because of Bukovsky. He was just taken to the Vladimir prison then. So they kept us away from that hunger strike, saying: “Guys, you’re still young, you don’t really know what’s what yet.” We only fasted for about three days then. I know Dmytro Demydiv came out of that hunger strike on the seventh day. I don’t think they even put him in the punishment cell. And then it started: in 1975 and later, there were many small hunger strikes, one, two, or three days.

V.O.: Who was in charge at the 35th zone?

V-I.Sh.: The leadership was: Major Pimenov, the zone chief, and Captain Ketmanov, the political officer. And who was the “godfather”? Many “godfathers” were replaced there; I don’t remember who the operative was.

M. Motriuk: Bukin.

V-I.Sh.: Bukin, yes. A “young” lieutenant, Bukin. He played billiards with us. The shop foreman was Zhilin. He had some issue with the Armenians, purely personal stuff.

We had an action there to renounce our citizenship. About forty people took part. I wrote several applications to the Supreme Soviet, and the replies that came back were: “Complaint unfounded. Convicted correctly.” This was after the Helsinki Accords in 1975*.

There was a whole series of renunciations of citizenship; we were demanding the status of political prisoners. We wrote sharp statements. And then, when Brezhnev's Constitution was adopted (October 7, 1977), we held a week-long protest of silence. It lasted for about a week. I wrote a statement that I was remaining silent because there was no freedom of speech—several people did this*. (*See about this in Mykola Horbal’s publication "Chronicle of the ‘Gulag Archipelago.’ Zone 35 (For 1977)" in the journal "Zona," no. 4, 1993, p. 141: "On October 4, as part of the week of silence, Soroka*, Shovkovyi, and Ghimpu* declared a hunger strike"; p. 142: October 9... As part of the week of silence, political prisoner Shovkovyi sent a statement to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, in which he once again confirms his renunciation of Soviet citizenship and his intention to seek to leave for Holland after his release from the camp. (...) On October 11, KGB agents Utyro and Shchukin summoned political prisoners Mykytko*, Shovkovyi, Ghimpu, and Soroka to clarify their intended place of residence after release. (...) Shovkovyi also named Holland as his place of residence." As stated in the preface, this "Chronicle" was smuggled out to freedom by Yaromyr Mykytko. He recounts this in an interview given to me on January 27 and 30, 2000. – V. Ovsiienko).

I copied statements, and they were passed on to the outside. My mother passed them on too, as she had just come for a visit. I passed a lot of things through her then. She took it all to Lviv, to Olena Antoniv*. She was Zinoviy Krasivskyi's* wife. What year did she die?

V.O.: She died on February 2, 1986.

V-I.Sh.: She was hit by a tram and fell under a car. That was already under Gorbachev.

I was transcribing documents, various articles, and statements for about two years, until... Do you know Vasyl Zakharchenko*?

V.O.: Vasyl Zakharchenko now lives in Cherkasy. I met him a few years ago. He is a talented writer, a laureate of the Shevchenko Prize.

V-I.Sh.: Well, he was pardoned. There was his article....

V.O.: In *Literaturna Ukraina*, around 1977.

V-I.Sh.: Yes. And after that article, the GB knew the whole layout, who was involved in this in the zone.

V.O.: Really?

V-I.Sh.: Well, clearly he had to reveal something to be released. I have no proof, but Ihor Kalynets* said he had told Zakharchenko about certain things.

I already mentioned that for a time I even kept a chronicle of the 35th zone. They must have gotten their hands on some statements, articles from the zone. Mostly, it concerned Valeriy Marchenko*, but it was written in my hand. Not written, but copied.

V.O.: You copied it in a very tiny script?

V-I.Sh.: Yes. I wrote very small, in a draftsman's font. They couldn’t prove who wrote it. Semen Gluzman* told me that no expert analysis would establish it. “This,” he said, “is not a serious matter. You can't prove from such handwriting that you wrote it”*. (*See about this in "Zona," no. 4, 1993, p. 137: "On August 11, KGB officer Honchar arrived in the zone. He summoned political prisoners Shovkovyi and Proniuk* for a conversation (in the presence of KGB Major Utyro). Honchar intimidated and threatened Shovkovyi, threatened him with legal prosecution, citing that the KGB allegedly had information that he, Shovkovyi, was involved in passing materials from camp 35. In the end, he demanded an article from Shovkovyi for a newspaper, similar to V. Zakharchenko's, but Shovkovyi refused").

V.O.: They probably wanted to use it in the second case of Valeriy Marchenko, which was opened on October 21, 1983?

V-I.Sh.: In 1983, around November 25-26, I was interrogated again, this time in Ivano-Frankivsk. An investigator from Kyiv came regarding Valeriy Marchenko's case. They started showing me many of the things that Valeriy had written, and which I had copied. It was all magnified many times over. I think Valeriy’s letter to his grandfather* was there too. (*Valeriy Marchenko. Letters to His Mother from Captivity. Oleh Olzhych Foundation. Kyiv: 1994.— pp. 167– 170). I refused. They kept me at the GB all day. I copied the lead article of the newspaper *Prykarpatska Pravda* three times in different font sizes. They wanted to use me as a witness to confirm that Valeriy had written it, and I had copied it. I said: “Don't involve me in this.” Not even a year had passed before Valeriy Marchenko died* (*October 7, 1984. – Ed.).

So, the GB knew the whole layout of who was doing what. That was 1977, when delegations of "the public" from Kyiv would come, and we wouldn’t go to the talks* (*See about this in "Zona," no. 4, 1993, pp. 142-143: "On October 14, a so-called ‘delegation of the public’ from the Ivano-Frankivsk region (Western Ukraine) arrived in the zone, led by KGB agent Kovtun and Andrusenko. They summoned Kvetsko* and Shovkovyi for a conversation. They spread rumors about the ‘prosperity’ of Soviet Ukraine, etc. They tried to persuade Shovkovyi to abandon his intention to go abroad after his release, citing ‘unemployment and the horrors’ of the capitalist system. They brought him letters from his sister, clearly written under the dictation of the KGB."). A colonel from Moscow came and had a long talk with Gluzman at work. They knew information was getting out of the zone, but they couldn't catch it. Then they caught the wife of Mati Kiirend, an Estonian, and caught someone else there. Later, they found Oles Shevchenko's* archive in Kyiv. The GB found out a lot. I was copying some statement for Vasyl Pidhorodetskyi*, and I had to eat two pages. Well, there was nowhere else to put it. That’s how Dmytro Verkholiak* covered for me. The old man fell asleep. I looked around—two guards were already next to me. So, I ate it all. After that, I couldn’t write a letter for a year. They had to check me ten times to see what I was writing. I couldn't write a letter without a guard present. Whenever I sat down to write something, a guard would come and watch what I was writing. But even after that, Ihor Kalynets and I put together an interview, and it was broadcast on Radio Liberty. We managed to pass it on sometime at the end of 1976. They demanded—both there and after my release, in Frankivsk—twice, that I write something, a repentance. So I wrote three words, that I had nothing to do with it. That everything in the interview was stated correctly, but I wasn’t the one who passed it on. And who interviewed me—that’s not my problem. I can say what I want to whom I want. And with you, I say, I’m speaking just the same, and I’m not ashamed. For that, they gave me three years of supervision after my imprisonment. First for a year, and then they kept extending it.

V.O.: I will add that when Vasyl Zakharchenko's statement appeared in *Literaturna Ukraina*, his godfather Vasyl Stus*, already in exile in the Magadan Oblast, sent him a telegram with two words: “For shame, Vasyl!”

V-I.Sh.: And the things he wrote in there... He really hit Ihor Kalynets hard, and someone else. Taras Melnychuk* also wrote something from the psychiatric hospital; it was in the regional newspaper. But Taras wrote about atomic bombs, without implicating anyone. In such general terms, because he obviously needed to get out of there. So it goes...

And Oles Serhiienko* was there too. You know that he and Dmytro Demydiv moved from the hospital to our zone? They climbed over the fence there. As I understood from Dmytro, Serhiienko started saying they were being poisoned there. And they ran over to our zone at dawn. I woke up in the morning—and Dmytro is standing in front of me! I'm thinking, how did he get here, when he's in the 36th zone? Then the GB did a shuffle: they took Ihor Kalynets, Ivan Svitlychnyi*, Valeriy Marchenko*, and someone else to the 36th zone. And they sent Yevhen Sverstiuk* here. Then they brought Marchenko back anyway, because he had to be kept near the hospital constantly. He was brought to the hospital in the summer, then released back to us. Oh, and they also transferred Gluzman* to the 36th.

V.O.: Did you spend your entire sentence at Vsekhsvyatskaya?

V-I.Sh.: Yes, in the 35th zone; they didn't move me anywhere.

V.O.: And how was your health there?

V-I.Sh.: It was fine, I was young, I could withstand anything. It was only a year after the army. Of course, it was a psychological blow, but as for food, there were no problems for me.

M. Motriuk: At least there was plenty of bread there.

V-I.Sh.: We had Latvians in the kitchen there. They were honest guys; they didn’t steal anything. And the camp was small. When we arrived, there were about two hundred and fifty prisoners, maybe a little more. And then the number decreased. When we were leaving, Myroslav Symchych* said: “Who will I be here with? With these Belarusians?” They were just starting to imprison Belarusian partisans then. They were rounding up entire battalions, holding show trials in military units*. (*During the "No One is Forgotten, Nothing is Forgotten" campaign, "traitors to the motherland" were tried almost every year in nearly every region to maintain an atmosphere of fear in society. – Ed.). Every month, Belarusians would arrive at the zone. I said: “Don’t worry! There will be more!” Just then, they started prosecuting members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group* for the second time.

V.O.: Those were already going to the especially strict-regime camps.

V-I.Sh.: Yes, but many were going for the first time too. Myroslav Marynovych* and Mykola Matusevych* arrived, co-defendants Stepan Khmara* and the two Shevchenkos—Oles* and Vitaliy*.

Then a cunning article came out: whoever earned a criminal sentence in the camp could go to a regular labor camp. It was thought that from there it would be easier to get parole. Vasyl Pidhorodetskyi and Myroslav Symchych had such additional sentences and wanted to go. But they were "interrogated" even more there. I later said to Symchych: "So what? It didn't turn out my way, did it?"

V.O.: And how were you released? From Vsekhsvyatskaya, or were you brought by transport to Ivano-Frankivsk?

V-I.Sh.: They brought me here. I used to say: “Put it back where you found it.” On February 23, 1978, on Soviet Army Day, they took me on a transport; I remember that well. I only managed to say goodbye to Anatoly Altman. They grabbed me so quickly that the guards themselves later brought my things to the guardhouse. Unexpectedly. Sometime before six o'clock, even the first shift wasn't up yet.

V.O.: So you wouldn't have time to "charge up" with information.

V-I.Sh.: And so they transported me. For almost a month. I spent a long time in the Kharkiv prison. Arriving at the Frankivsk prison felt like coming home. Roman Chuprei said that he and Dmytro Demydiv arrived at the Frankivsk prison together. They were walking on the fourth floor singing about Bandera. Singing for the whole floor to hear. The warden says: "O-ho! You see, our boys are here!" I recognized one who had searched me; he had sergeant's stripes then, and now I see he has a star. I say: "Listen, I've come here from the Urals. What can you possibly find on me?" I had a few books in a pillowcase, a piece of dry bread they gave me in Lviv. "Well, you still have to," he says, "empty it out." I emptied it. I don’t know who he was. "Well, tell me! We have to sit for at least half an hour." "What should I tell you about? How the GB got me the first time?"

They brought me in the morning on the Lviv train, by prison van to the prison—and the GB grabbed me right away. And immediately about that interview. I went at him: "What's this interview you're on about?" And in the Urals, the operative Bukin and the GB agent Utyro had shown me a photocopy (already quite clear and distinct) of the statements I had copied. And prints from some American newspaper where they were reprinted. About the renunciation of citizenship. He says: "Look, this could lead to a second sentence." I think to myself: since they brought me to Frankivsk, it's not for a second sentence.

And in Lviv, they had taken away my cross, so I tried to go on a hunger strike there. They returned it quickly. They took me to a cell and returned it.

V.O.: They learned their lesson with the crosses. They took one from Bohdan Rebryk* during a search on a transport in Kyiv. Rebryk, naked, jumped on the table and hid the cross in his mouth. Then a major tried to pull it out of his mouth with his finger. And Rebryk—snap!—bit off one phalanx of his finger. The major started hopping on one leg, shaking his hand. They subdued Rebryk and threw him in the punishment cell. He came to—lying on the floor, his clothes beside him. And later, Rebryk himself petitioned to have a criminal case brought against him for biting off the major's finger. The replies came: “All our majors have their fingers.” That major was probably promoted to lieutenant colonel.

M. Motriuk: A drunk guard ripped my cross off too. Then they took me from the bathhouse to the punishment cell.

V-I.Sh.: Ah, when I was returning, I wasn't afraid of anything anymore. I made a lot of crosses in the zone. Even one for Sverstiuk, and then I made one at home and sent it to him in exile.

I was in the Frankivsk prison for about three days. They threw me in after lunch with convicts waiting for transport, while they were at work. Then in the evening, they took me with them to the cinema. They were taken to work, and I sat in the cell all day.

They are releasing me. My mother and father arrived. They went through everything, wrote out the papers. The guard at the checkpoint says: “Well, hang in there, boys!”

When I arrived, I stayed at home for about a week, didn't want to go to the police in Kolomyia for those documents. They were just changing passports at that time. People couldn't get a passport for six months, but mine was ready in about fifteen minutes. So efficiently. By the time I went to the military enlistment office to get my military ID, the passport was already on the table, ready. And right away they put me under administrative supervision. To be at home from ten at night until six in the morning. If they catch you out, there will be trouble.* (*Article 196-1 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR "Violation of the rules of administrative supervision" provided for up to 3 years of imprisonment. – Ed.). The first year I didn't violate the regime. I didn't violate it—but they extended the supervision for another year. Because of those "eighth Saturdays." I'm at work, and the police say: "I don't care about any 'eighth Saturdays,' you must be here for me, sharp, by ten in the morning."

V.O.: What are "eighth Saturdays"?

V-I.Sh.: A workday. The work week was 42 hours, so it turned out that once every two months, there was a working Saturday. That was my violation. The police aren't interested in that, but here they tell me I have to be at work. Well, I could have asked for time off from work. But they needed a pretext to extend the supervision. The policeman Bilous says: "I'm not in charge of this. You go to the house next door, deal with them." And there, the police and the KGB are neighbors. "You," he says, "go and sort it out with them, because I didn't do this. I could have already released you from this supervision."

And in the third year—I was coming from Kolomyia by bus and was a bit late, by about 15 minutes. The police were hunting for me. It was only later that I talked to the KGB agent Boroda. He has since died. Do you know him? He was the supervisor of the zones in Mordovia.

V.O.: There was a KGB agent in Mordovia named Boroda.

V-I.Sh.: I don't know why he was based here in Frankivsk. We had some "heart-to-heart talks" with him, with coffee and cognac. I say: "Well, how long can this go on? A young man, sitting at home every evening, when am I supposed to get married? Do you want me to go to prison again?" He was sick with something, cancer, or something. You could see it on him. In 1984, I asked our investigator, Rudyi (he was already a lieutenant colonel by then, probably got his star for our case): "Well, how is Mr. Boroda?" "He died." I say: "A pity. He was a good guy." So we talked.

Twice a year or so, if they didn't come to my work, they would summon me to the village council or somewhere else. They didn't summon me to the GB. They were testing my "rottenness." In 1989, some guy named Koloskov and another one. I say: "Just pick up any magazine, *Novy Mir* or *Ogoniok*, and read it: they're spewing such anti-Soviet stuff! What more can I write for you? I'm already behind the times."

The last time I met that Koloskov was when we were putting up a cross in the cemetery. There was a whole pack of them, those GB agents, milling around. He says to me: "Good day!" And I'm carrying my little girl on my shoulders and reply: "Glory forever!" They were thinking of bothering me. But they saw there was no way anymore.

V.O.: And how was it with work?

V-I.Sh.: After my release, I worked here near my home at the municipal services combine. For the first six months as a locksmith, and then I became a lathe operator. I'm still officially employed there, but in fact, for about three years now, there's been no salary, so I don't go.

V.O.: And one more question. Where did you find such a beautiful Anna, and when? Maybe I should go there too?

V-I.Sh.: We got married in 1983. Exactly two years after they lifted my supervision.

V.O.: And when various public organizations started forming in 1987, 1988, did you take part in that?

V-I.Sh.: We initiated the People's Movement (Narodnyi Rukh) here. Not in the leadership, but more as advisers. Guiding the young ones. The trouble is that the wrong people got into this Rukh.

V.O.: And the Ukrainian Helsinki Union of 1988*, the Society of the Repressed?*

V-I.Sh.: We created the Society of the Repressed right away.

V.O.: Were you at the Constituent Assembly on Lvivska Square in Kyiv?

V-I.Sh.: I know about that, Yevhen Proniuk told me. We were at the assembly in the House of Cinema in 1990. Bozhena Ravchuk invited us. We spent the night at her place on Bekhterivskyi Lane. There, a guy from Kryvyi Rih says that it should be renamed to Bandera Lane. Near the Cuban embassy. I didn't know Kyiv, so rather than ask, I bought a map and found everything quickly.

M. Motriuk: There were about ten of us staying at Ms. Bozhena's place then, and the next day they got us a hotel.

V.O.: And please, tell me the names of your glorious little girls.

V-I.Sh.: The elder daughter is Oksana, born November 11, 1985, and the younger is Natalka, born April 16, 1992.

V.O.: Thank you. But still, what is your name—Vasyl or Ivan?

V-I.Sh.: According to my documents, it's Ivan, but at home, everyone calls me Vasyl.

V.O.: Is that so no evil force could get a hold of you?

V-I.Sh.: So that no one would guess.

V.O.: But the KGB guessed anyway and got you. Well, I think that evil force won't be grabbing us anymore. We are, after all, a luckier generation, because our predecessors laid down their heads and did not see independence. And we, one way or another, achieved it. I hope that these girls will fill that independence with Ukrainian substance. I thank you sincerely. (The conversation continues outside). Mr. Vasyl, why are you Pechenegs, why is your village called Pechenizhyn?

V-I.Sh.: There is a legend that in the old days, the Pechenegs were defeated here. In the Dibrova tract, near the school, children used to walk and find bones and weapons. The 550th anniversary of Pechenizhyn has already been officially celebrated.

V.O.: But the Pechenegs were even earlier.

V-I.Sh.: Archaeological excavations show that the settlement here existed much earlier.

V.O.: And do you feel anything of the Pecheneg in you?

M. Motriuk: There are versions that captured Pechenegs were settled here.

V-I.Sh.: We had a historian here, but he has already passed away. He was a Sich Rifleman. He would tell us which family descended from whom: those from the Mongols, those from the Tatars. Because we have people with Mongolic features. That gene shows up from time to time.

By the way, a little further on, where the monument to Oleksa Dovbush stands, there is an ancient military burial ground, 27 mass graves. They conducted excavations, but there's nothing there. There was a huge battle here, but when, and between whom—nobody knows. I asked our historians—nobody knows anything. They find flint axes there. People lived there.

V.O.: And what is this mountain range near Pechenizhyn called?

V-I.Sh.: Varatyky. Those aren't mountains yet. That’s the foothills. It's not seven hundred meters here. There was an old Hungarian military map. The altitudes are clearly marked there. It's not seven hundred meters.

Information about Persons and Realities Mentioned in the Interview with V-I. Shovkovyi

Antoniv, Olena, 11/17/1937 – 2/2/1986. Participant in the Sixtiers movement, human rights activist. Wife of V. Chornovil, later of Z. Krasivskyi.

Arrests of January 12, 1972 – a KGB operation targeting Ukrainian samvydav, which resulted in the imprisonment of its main authors and organizers.

Bukovsky, Volodymyr – dissident, human rights activist, convicted in 1967 to 3 years, in 1971 to 12 years. In December 1976, he was exchanged for the general secretary of the Communist Party of Chile, Luis Corvalán.

BUR – "barak usilennogo rezhima" (barracks of enhanced regime), the same as PKT – "pomeshchenie kamernogo tipa" (cell-type premises). In a strict-regime camp, the punishment was up to 6 months; in an especially strict-regime camp, up to a year.

Verkholiak, Dmytro – insurgent, sentenced to 25 years, was incarcerated in the Perm camps in the 1970s.

All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Victims of Repression was established on June 3, 1989, in Kyiv on Lvivska Square. Its permanent chairman is Yevhen Proniuk.

Vozniak (Lemyk), Liuba Yevhenivna, born 9/30/1915 in Krynytsia, Nowy Sącz Powiat. On August 4, 1941, she married Mykola Lemyk. Stepan Bandera was the witness. On an OUN assignment, she worked in Kremenchuk, Poltava, and Kharkiv. Arrested by the NKVD on 12/22/1946 in Lviv. The investigation was conducted in Kyiv at 33 Korolenka Street. In the fall of 1948, she was sentenced to death, which was commuted to 25 years of imprisonment. She was incarcerated in Mordovia and Norilsk, released in 1956. She lived in Taganrog and Anzhero-Sudzhensk, and from 1968, in Ivano-Frankivsk. She participated in the human rights movement of the 1960s–90s.

Haiduk, Roman, born 1937, arrested in March 1974 in the Ivano-Frankivsk region. Sentenced to 5 years imprisonment and 3 years exile. Was incarcerated in the Perm camps.

Helsinki Conference of 1975 – The Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe concluded with the signing of the Final Act on August 1, 1975, which, among other things, stipulated the observance by participating states of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of the UN of December 10, 1948.

Ghimpu, Gheorghe – political prisoner, Moldovan, was incarcerated in the 1970s in Mordovia, from 1976 in the Perm camps.

Horbal, Mykola, born 9/10/1940, imprisoned on 4/13/1971 under Art. 62, Part 1, for 5 years and 2 years exile; a second time on 10/23/1979 for 5 years; a third time on 10/10/1984 for 8 years and 5 years exile, released on 8/23/1988. Member of the UHG, writer, musician, People's Deputy of Ukraine of the 2nd convocation.

Gluzman, Semen, born 9/30/1946, imprisoned on 5/11/1972 under Art. 62, Part 1, for 7 years of imprisonment and 3 years of exile. Currently the Head of the Ukrainian Psychiatric Association.

Hrynkiv, Dmytro Dmytrovych, leader of the “Union of Ukrainian Youth of Galicia” (1972). Born 6/11/1949 in the village of Markivka, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Arrested on 3/15/1973 in Kolomyia. Charged under Art. 62, Part 1 (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”), 64 (“participation in an anti-Soviet organization”), 81 (“theft of state property”), 140 (“theft”), 223 (“theft of weapons and ammunition”) of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, sentenced to 7 years in strict-regime camps and 3 years of exile. Was incarcerated in camp VS-389/36 in the village of Kuchino, Perm Oblast. Released in 1978. A writer. Lives in Kolomyia.

Demydiv, Dmytro Illich, born 12/3/1948 in the village of Pechenizhyn, Kolomyia Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Member of the “Union of Ukrainian Youth of Galicia” (1972). Arrested on 4/4/1973. Under Art. 62, Part 1 (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”), 64 (“participation in an anti-Soviet organization”), 223, Part 2 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR (“theft of weapons”), sentenced to 5 years in strict-regime camps. Was incarcerated in the Perm camp VS-389/36.

Dziuba, Ivan – born 7/26/1931, one of the leaders of the Sixtiers movement. Author of the book “Internationalism or Russification?” (1965). Arrested on 4/18/1972, sentenced under Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to 5 years in camps and 5 years of exile. In October 1973, he appealed to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the UkrSSR for a pardon. Released on 11/6/1973. Literary critic, academician of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Minister of Culture of Ukraine in 1994-94, laureate of the T. Shevchenko Prize in 1991, Hero of Ukraine.

DOSAAF – "Dobrovolnoye obshchestvo sodeystviya Armii, Aviatsii i Flotu" (Voluntary Society for Assistance to the Army, Air Force, and Navy). An organization created by the authorities to prepare youth for service in the Soviet Army.

Zakharchenko, Vasyl, born 1/13/1936. Arrested in January 1972, incarcerated in camps in the Perm Oblast. Pardoned in 1976. A writer, laureate of the Shevchenko Prize in 1995.

Kalynets, Ihor, born 7/9/1939, imprisoned on 8/11/1972 under Part 1 of Art. 62 for 6 years and 3 years of exile. A poet, laureate of the Shevchenko Prize in 1991.

Kandyba, Ivan, 6/7/1930 – 12/8/2002, a founding member of the Ukrainian Workers' and Peasants' Union, later a founding member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. Imprisonment: 1961–1976, 1980–1988.

Kvetsko, Dmytro, born 1935, leader of the Ukrainian National Front, imprisoned in 1967 for 15 years and 5 years exile.

Krasivskyi, Zinoviy, 11/12/1929 – 9/20/1991, political prisoner in 1948-53, 1967-78, 1980-85. A founding member of the Ukrainian National Front (1964–1967), member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group.

Marynovych, Myroslav, born 1/4/1949, a founding member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, arrested on 4/23/1977, sentenced to 7 years imprisonment and 5 years of exile under Art. 62, Part 1, was incarcerated in the Perm camps.

Marmus, Volodymyr, born 3/21/1949. Leader of the Rosokhach group, imprisoned on 2/24/1973 for 6 years and 5 years of exile under Art. 62, Part 2, 64, etc. Was incarcerated in the camps of the Perm Oblast and in the Tomsk Oblast.

Marmus, Mykola, born 5/1/1947, arrested on 4/11/1973 as a member of the Rosokhach group, imprisoned for 5 years and 3 years of exile. Was incarcerated in the Perm camps and in the Tomsk Oblast.

Marchenko, Valeriy, 10/16/1947 – 10/7/1984. Journalist, member of the UHG. Imprisoned on 6/25/1973 for 6 years and 2 years of exile; a second time on 10/21/1983, for 10 years of especially strict-regime camp and 5 years of exile. Died in a prison hospital in Leningrad. Buried on the Feast of the Intercession in 1984 in the village of Hatne near Kyiv.

Matusevych, Mykola, a founding member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, born 7/19/1947, arrested on 4/23/1977 as a member of the UHG, sentenced to 7 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile. Released in 1987.

Melnychuk, Taras (8/20/1938 – 3/29/1995. Imprisoned on 1/24/1972 under Art. 62, Part 1, for 3 years; a second time in January 1979 under Art. 207 ("hooliganism") for 4 years; laureate of the Shevchenko Prize in 1992).

Mykytko, Yaromyr, born 1953, imprisoned as a student of the Forestry Institute on 3/23/1973 under Art. 62, Part 1, for 5 years. Was incarcerated in Mordovia and in the Perm Oblast.

Motriuk, Mykola Mykolaiovych, born 2/20/1949 in the village of Kazaniv, Kolomyia Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Member of the “Union of Ukrainian Youth of Galicia.” Arrested on 3/15/1973, sentenced under Art. 62, Part 1 (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”) and 64 (“creation of an anti-Soviet organization”) to 4 years of imprisonment. Was incarcerated in the camps of the Perm Oblast.

Pidhorodetskyi, Vasyl, born 10/19/1925, insurgent, arrested in February 1953, imprisoned for 25 years, 5 years of exile, and 5 years of deprivation of rights. For organizing strikes, he was sentenced a second time to 25 years. Released on 3/29/1981, he was tried twice more for "violation of passport regulations." In total, he spent 32 years in captivity.

Popadiuk, Zorian, born 4/21/1953, imprisoned as a student of Lviv University on 3/23/1973 for 7 years and 5 years of exile under Art. 62, Part 1; a second time on 9/2/1982, for 10 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile. Released on 2/5/1987.

Proniuk, Yevhen, philosopher, born 1936, on 7/6/1972 imprisoned for 7 years and 5 years of exile under Art. 62, Part 1. Permanent chairman of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Victims of Repression, established on 6/3/1989. People's Deputy of Ukraine of the 2nd convocation.

Rebryk, Bohdan, born 7/30/1938, imprisoned on 2/6/1967 for 3 years under Art. 62, Part 1; a second time on 5/23/1974 under Part 2 of Art. 62 for 7 years and 3 years of exile. Returned from Kazakhstan in the summer of 1987. People's Deputy of Ukraine of the 1st convocation.

Sverstiuk, Yevhen, born 12/13/1928. Literary critic, publicist, one of the leaders of the Sixtiers movement. Imprisoned on 1/14/1972 under Art. 62, Part 1, for 7 years and 5 years of exile. Was incarcerated in the Perm camps and in Buryatia. Doctor of Philosophy, Laureate of the Shevchenko Prize in 1993.

Svitlychnyi, Ivan, 9/20/1929 – 10/25/1992. Recognized leader of the Sixtiers movement. Imprisoned on 8/30/1965 for 8 months without a trial; a second time on 1/12/1972 under Art. 62, Part 1, for 7 years and 5 years of exile. Laureate of the Shevchenko Prize in 1994, posthumously.

Serhiienko, Oles, born 6/25/1932. Imprisoned on 1/12/1972 under Art. 62, Part 1, for 7 years and 3 years of exile. Was incarcerated in the Perm Oblast, in the Khabarovsk Krai.

Symchych, Myroslav, born 1/5/1923, commander of the Bereziv company of the UPA. Imprisoned on 12/4/1948 for 25 years; for participation in a strike, a second time for 25. Released on 12/7/1963. Without a trial, on 1/28/1968, imprisoned for another 15 years; towards the end of the term, for 2.5 years. A total of 32 years, 6 months, and 3 days of captivity. Lives in Kolomyia.

Soroka, Stepan – insurgent, sentenced to 25 years. Died in 2001 (?).

“Union of Ukrainian Youth of Galicia,” (SUMH) – an underground youth organization. It emerged in January-February 1972 in the village of Pechenizhyn, Kolomyia Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. The initiator of the Union's creation was the locksmith Dmytro Hrynkiv. The SUMH considered itself the successor to the OUN under new conditions; its goal was the creation of an independent Ukrainian socialist state (on the model of Poland or Czechoslovakia). Hrynkiv and the engineer Dmytro Demydiv developed the statute and program of the SUMH, but did not have time to adopt them. The group consisted of 12 people; its members (workers and students) held meetings (a kind of seminar), obtained several rifles, learned to shoot, collected OUN literature, memoirs, and insurgent songs. The SUMH was uncovered by the KGB; in March-April 1973, the group's members were arrested, and five of them were convicted (Dmytro Hrynkiv, Dmytro Demydiv, Mykola Motriuk, Roman Chuprei, Vasyl-Ivan Shovkovyi).

Starosolskyi, Liubomyr, born 1955, imprisoned in August 1973 for 2 years for raising a flag in Stebnyk, Art. 62, Part 1. Was incarcerated in the Mordovian camp No. 19.

Status of a political prisoner. The idea of the status of a political prisoner arose in the political camps in the mid-1970s. Since the authorities considered "especially dangerous state criminals" to be ordinary criminals, prisoners transitioned to the self-proclaimed status by direct action: they refused to wear camp uniforms and name tags, demanded work in their specialty, unlimited correspondence, proper medical care, and other rights. This led to additional punishments.

Stus, Vasyl, born 1/7/1938 – 9/4/1985. Arrested on 1/12/1972 under Art. 62, Part 1, for 5 years of imprisonment and 3 years of exile (Mordovia, Magadan Oblast). A second time on 5/14/1980, died in the punishment cell of the especially strict-regime camp VS-389/36 in Kuchino, Perm Oblast, on the night of September 4, 1985. Member of the UHG, poet, T. Shevchenko Prize in 1993, posthumously. On 11/19/1989, reburied at the Baikove Cemetery along with Yu. Lytvyn and O. Tykhyi.

Society of Political Prisoners – see All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Victims of Repression

Ukrainian Helsinki Group – The Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords was established on 11/9/1976 with the aim of disseminating the ideas of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of the UN of 12/10/1948 in Ukraine, the free exchange of information and ideas, promoting the implementation of the humanitarian articles of the Helsinki Final Act, and demanding the direct participation of the UkrSSR in the Helsinki Process. Founding members: Mykola Rudenko, Petro Grigorenko, Oksana Meshko, Oles Berdnyk, Levko Lukianenko, Mykola Matusevych, Myroslav Marynovych, Nina Strokata, Oleksa Tykhyi, Ivan Kandyba. 39 out of 41 members of the UHG were imprisoned. On 7/7/1988, it was transformed into the Ukrainian Helsinki Union, and on 4/29/1990, at its Constituent Congress, the majority of its members created the Ukrainian Republican Party on its basis.

Ukrainian Helsinki Union was established on the basis of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group on 7/8/1988. At the Constituent Congress of the UHU on 4/29/1990, the Ukrainian Republican Party was created, which included 2/3 of the UHU membership.

”Ukrainian Herald” – the first uncensored literary, publicist, and human rights journal in Ukraine. It was published in typewritten form in Kyiv. 1970–1972, issues 1–5, editor-in-chief – V. Chornovil; issue 6 was published in Lviv – M. Kosiv, A. Pashko, Ya. Kendzior. A Kyiv group, Ye. Proniuk and V. Lisovyi, released their own version, actually the sixth issue but labeled the 9th. From 1973–1975, issues 7–9 were published by S. Khmara, O. Shevchenko, and V. Shevchenko. It was revived starting with issue No. 7 by V. Chornovil in 1987 and was published until 1990.

Chuprei, Roman Vasylyovych, born 7/1/1948, in the village of Pechenizhyn, now Kolomyia Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, member of the “Union of Ukrainian Youth of Galicia.” Arrested on 3/15/1973, convicted under Art. 62, Part 1 (anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda) and 64 (creation of an anti-Soviet organization) to 4 years imprisonment. Was incarcerated in the camps of the Perm Oblast.

Shevchenko, Vitaliy, born 3/20/1934, journalist, imprisoned on 4/14/1980 for 7 years and 4 years of exile under Art. 62, Part 1.

Shevchenko, Oles, born 2/22/1940, journalist, arrested on 3/31/1980, 5 years of imprisonment and 3 years of exile under Art. 62, Part 1.

SHIZO – “shtrafnoy izolyator,” punishment isolation cell. Punishment was up to 15 days.

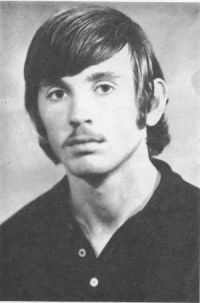

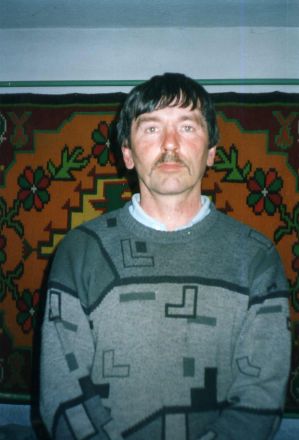

Photo by V. Ovsiienko:

Shovkovyj Film 9629, frame 15A, March 21, 2000, Pechenizhyn. Vasyl-Ivan SHOVKOVYI.

Shovkovyj2 Film 9629, frame 15A, March 21, 2000, Pechenizhyn. Vasyl-Ivan SHOVKOVYI, his wife Anna, daughters Oksana and Natalia.

Photo:

Shovkovyj1 Vasyl-Ivan SHOVKOVYI in his youth.