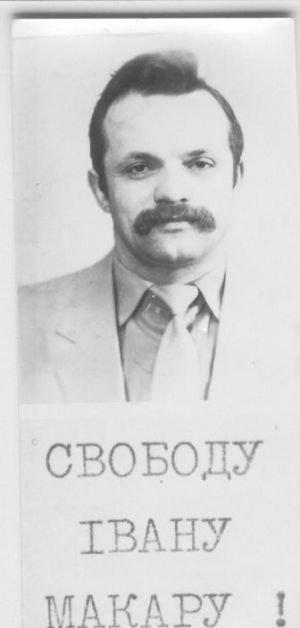

Interview with I. I. Makar

V. V. Ovsienko: Ivan Makar speaks on May 29, 2000. Recorded by Vasyl Ovsienko.

I. I. Makar: I am Ivan Makar, born in 1957. I was born on January 15. I come from a line of Carpathian Boykos. I was born in the village of Halivka, Staryi Sambir Raion—it’s now right on the Polish border, at the edge of the Turka Raion, in the Carpathians, on a remote farmstead. My mother’s family line goes back to the Dovbushes. According to legend, Oleksa Dovbush’s brother, after they had a falling out, went to the Western Carpathians and settled somewhere in those parts. So my mother, in fact, comes from the Dovbush clan.

V. V. Ovsienko: Was that her surname?

I. I. Makar: By her family’s nickname—the local name for them—she was from the “Dovbush plot,” where the Dovbushes lived. It could have been the brother himself, or it could have been one of Dovbush’s opryshky—it’s hard to say now. But at the very least, my mother has the Dovbush temperament. She fought with the authorities her whole life, always getting into some kind of trouble. At one point, she was fired from her job as head of the local club for refusing to toe the authorities’ line. Even after that, though she was no longer the director, she was always helping out there—she would stage Shevchenko evenings at the club, put on various plays, and even organized a village ensemble that performed at the first Boyko festivals. And this was from such a tiny village…

V. V. Ovsienko: What is your mother’s name, and what was her maiden name?

I. I. Makar: Her maiden name was Kateryna Voloshchak. By the way, she is some distant relative of Voloshchak—there was a blind poet named Voloshchak in Lviv. She was born in 1934. And my father was Ivan Makar, born in 1927. My father has an interesting biography. Like most young people then, my father was in the youth nationalist organization “Luh.” Our relative was a company commander in the UPA. But it was already clear that the national underground was in decline, that it would be practically wiped out. So my father’s brother persuaded that relative to kick my father out of the UPA. Well, they staged some situation—and he was expelled from the UPA. And then the informants later pointed him out: “Oh, that kid? He was kicked out!” So they didn’t bother him after that. But he continued to work for the underground. He helped out by working as an accountant at the kolkhoz and receiving money. The partisans knew when he was bringing money from the raion center, so they intercepted him, gave him a few bruises, and took the money. And so he appeared to be a victim. Then he helped them clear out the kolkhoz storehouse. They had just brought in seed stock, and the partisans needed something to eat. So he helped. But when he saw that the whole area was saturated with informants, he essentially fled into the Soviet Army in 1950. He had a deferment as a kolkhoz accountant, but he volunteered for the army, served for three and a half years, and returned in 1953. And until the end of his working life, he worked as a record-keeper for a tractor brigade. He принциpally refused to join the Party.

So that is my lineage.

I finished primary school in my village. I received my secondary education at the Strylky boarding school. In the village where, incidentally, Mykhailo Horyn once began his career as an inspector for the raion department of public education. During my time there, Strylky was no longer a raion center, but Mykhailo started when it still was. It was a long way to walk to school from home, so parents would send their children to the boarding school to keep them from taking partisan trails instead of the road to school. And I would have done just that, because I had a wild nature in my youth, so they decided to send me to the boarding school.

V. V. Ovsienko: And did Horyn establish that boarding school?

I. I. Makar: Well, in principle, yes, with his active participation.

Let me tell you something. As a child, I read a great deal. And what was there to read? About Valya Kotik, Pavlik Morozov, and so on. You know, I was raised as what you’d call a true-believing communist. The fact that many of my relatives were in Siberia—from both my father’s and my mother’s side—that many had been exterminated, was perceived as something of a fairytale. And my parents, considering my straightforwardness, tried not to emphasize national issues too much at home. I lived by what I’d read about Pavlik Morozov and Valya Kotik. At the boarding school, I could get by on just a few hours of sleep a night. The teachers had already given up on me; no one bothered me, and at that age, I read voraciously. That’s what shaped me. I read all the volumes of Martin Andersen Nexø, the Danish writer.

Academics came fairly easily to me, especially the exact sciences. I once made it to the All-Union Physics Olympiad because I was the winner of the regional olympiad in both mathematics and chemistry. I didn’t get a medal. The teachers offered me a medal, but I refused on principle. I felt I wasn’t strong enough in the humanities, so I didn’t want to be a “padded” medalist.

I graduated from school in 1974, after 10th grade. And I immediately enrolled in the physics department at Lviv University. It was very easy to study there, too; there were no problems at all. The problems were financial because my parents were not wealthy. All the highlanders lived quite poorly at that time. My mother was often sick back then. I finished my first year with all A’s. During the summer holidays, in a student construction brigade in Vologda Oblast, I earned what was then a large sum of money—1,000 rubles. Now I think about how much money we buried in that development of the Non-Black Earth Region, where in the very same place they were simultaneously carrying out drainage and irrigation. On sandy soils. Look at the wonderful black soils in Ukraine, where it would have taken far less money to invest in land reclamation, yet it wasn’t done. Even then, I understood that it was an occupational government, clearly occupational, that wanted to make everything in Russia advanced while leaving Ukraine in the role of a periphery.

My active resistance to the authorities began, perhaps, as a game of war with the system. A friend of mine, with whom I had been at the All-Union Olympiad, came to visit. I represented Lviv Oblast, and he, Ternopil Oblast. A fellow named Petro Zhuk. He had enrolled in the famous Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, but for his second year, he transferred to our Lviv University because, first, he wasn’t in good health, and second, they provided technical training there, whereas he wanted more theory. There may have been other reasons—I don’t know. And he didn’t have the money to travel back and forth. Academics also came very easily to him. And when studies are easy, you have free time. Well, we talked about something, and we didn’t like something about the existing system. It turned out there were others who also disliked things. There was a Sashko Kryvoi or Kryvy at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology. I think he was from Vinnytsia Oblast, but he got in there—a talented guy. There was also some Muscovite, I think he also studied at MIPT. I don’t remember it all now. And in Kyiv, at the Agricultural Academy, there was Petro Zhuk’s classmate—Bohdan Ternopilskyi and a fellow named Kytsai or Kytsak. So we created our own secret organization. It was conditionally called the “Union for the Struggle for Development.” It was a youth organization, seemingly oppositional, but communist. That is, we were for communism, just not for that kind of communism.

V. V. Ovsienko: Communist dissidents.

I. I. Makar: Well, something like that. This was my second year of university, 1975–76. I remember we were preparing something for the next CPSU congress…

V. V. Ovsienko: The 26th, probably?

I. I. Makar: I don’t remember. We were preparing some letter for the congress. Our own credo of sorts. Petro Zhuk was writing it. To be honest, in that organization, I was a guy who wasn’t too deep into theory. I wasn’t very interested in all the philosophizing. The one thing that suited me was that I was involved in this noble cause. I took on the purely technical aspects. I went to my village with that piece of writing, and the secretary of the local kolkhoz, who had studied at my same boarding school a year after me—she was already working as a secretary at the local state farm—typed it all up for me on onion skin paper. The kolkhoz party organizer was walking around nearby, and he was as dumb as a post, so I told him it was for some paper for the university, and he believed me. But she, I think, was a smart girl—she later worked as a party organizer in that same kolkhoz. There’s even an article by her where she criticized me when I started the revolution in Lviv in ’88.

V. V. Ovsienko: And what kind of materials were they?

I. I. Makar: Well, it was our organization’s credo, some letters to the congress. For some reason, we thought that Romanov, the secretary of the Leningrad regional committee, was an oppositionist. But it later turned out that he was the most conservative, dyed-in-the-wool commie. But for some reason, we thought he was more progressive, so we sent him some materials, letters. My function was to get this stuff typed up, then the guys took it to Moscow and dropped it in a mailbox. The conspiracy was so they wouldn’t find out where the letters were from.

V. V. Ovsienko: So, it was written in Russian? And the organization had a Russian name?

I. I. Makar: Of course, yes. It was, in essence, a Soviet organization. We were Soviet patriots.

V. V. Ovsienko: Was there any national element to it?

I. I. Makar: None at all! It was pure communism; we believed that there should be a more correct communism because the existing one was incorrect. To be honest, I can’t even properly define our ideological platform now because, I confess, I never even read our credo thoroughly to the end. I kept one copy later. My younger brother, who was “initiated” into the matter, kept it. He stored it at home in the unheated room, inside the stove. If anything happened, he was supposed to light it, and everything would go up in smoke. But that copy also disappeared: when the KGB took an interest in me in 1977, my brother burned it. And the guys sent off the original. What was the reaction? How could we know? And did anyone even read it? It’s clear that it couldn’t have been the pinnacle of thought; it was the creation of a second-year student.

But later, my national feeling began to emerge. Purely by chance. A friend of mine was supposed to come to Lviv and called the dormitory, asking me to find and book a hotel room for him. Well, hotels were hard to come by then. I sat down at the front desk of the dormitory and started calling hotels, trying to find a room anywhere. And one lady from some hotel tells me: “Why don’t you speak a human language? Tell me what you need like a human being.” That outraged me, and after that, in philosophy class—at a seminar on the national question—I spoke up, saying that we talk about the equality of nations, yet here I am being told that I have to speak “in a human language.” This was said openly, and after that, I received my first C in my grade book, for philosophy. Well, maybe it wasn’t so much that as the fact that I just couldn’t bring myself to study that dialectical materialism. I read what I could get my hands on in philosophy, starting with Aristotle. There were these little brochures, I read them all, and that’s where my intellect went. But I didn’t have the wisdom to grasp the communist philosophy of Marx and Lenin. I just couldn’t stomach it.

But my character was being forged. By my third year, I had already been elected chairman of the faculty’s student scientific society. Everything was going as it should; I had a chance to stay on at the department, to have a scientific career. In our fourth year, our group was already the leader of the faculty. We decided that if there was a Komsomol, it should be a proper one. Therefore, the people we thought were necessary should be elected to the Komsomol bureau, not the ones the party bureau recommended to us. And we succeeded. I spoke up and said that a certain man had embezzled funds in the student construction brigade, that people didn’t trust him, but the Party had recommended him because he was a candidate for Party membership. We shot him down; he didn’t get through.

We shot down two of their recommendations for the trade union bureau. Then the student council. Our group decided that I should be the head of the student council. The meeting is underway. And then the party organizers from two faculties whose students lived in this dormitory—journalism and physics—show up. There were more physics students. The students propose Makar and elect him. Apparently, the party organizers had instructions for someone else to be elected; they saw the situation was getting out of control and declared the meeting invalid. Then they started to work on us.

The processing, you know how it was: an extended department meeting, Komsomol meetings, trade union meetings, and they dragged us everywhere—to the dean’s office… I come home once, and the KGB had already been there before me, to my parents: rein in your little boy, he’s up to no good there. And I thought I was a true-believing Komsomol member! But apparently, I had misunderstood the Party’s policy—one thing is written, but two others are kept in mind. I didn’t want to keep anything in mind; I wanted what was written. And what was written was that I had the right to choose, that there was democratic centralism, elections from the bottom up. Well, that’s what we did. I actually came home because they had made such a fuss. Before that, my mother’s cousin had come from Lviv to see my parents, also saying that word had reached them that something was brewing over my head. At that time, I had a girlfriend who was on the university’s Komsomol committee. When I met her once, she said: “Are you leading some nationalist group here?” I was surprised myself: none of it had any nationalist motives. But in Lviv, it was immediately interpreted as nationalism. The entire system was geared toward fighting nationalism. Anything inconvenient had to be labeled as nationalist. But in reality, it was just our purely Komsomol efforts.

In an instant, my entire career went down the drain. In my diploma supplement, two-thirds of my grades are A’s, and one-third are C’s; there are almost no B’s. This at least does credit to the professors, that they didn’t give me F’s. Sometimes without even listening to what I was saying: “You used to know this better—‘satisfactory.’” The head of the theoretical physics department at the time, who was my thesis advisor, Professor Blazhiyevsky, later confessed to me. He still teaches at the same university. He confessed to me: “We were pressured to give you F’s.”

But at that time, they did expel two students, including Orest Chaban, supposedly for academic failure. But they specialized in a different department. Chaban later became the secretary of the Lviv Oblast Council of the first convocation. Then he worked as a secretary at the embassy in Uzbekistan because he moved there right after his expulsion. He had studied there from his first year, but he was expelled from Lviv in his fourth. He studied there, so he knew their language a bit. Whether it was in Uzbekistan or Turkmenistan, I don’t remember now.

Everything went to pieces for me; I became a person distrusted by the authorities. After graduation, I went to work at a school in the neighboring village. Not where I had studied, but in a neighboring mountain village, to teach physics. This was in 1979. A secondary school. The village of Mshanets. I worked there for a while. It was interesting. An authorized KGB officer would visit from time to time. I saw him quite often, but he never had any of those “prophylactic” talks with me. The only thing was, I had a lab assistant, a man who did practically nothing but constantly engaged me in some kind of conversations. My father had warned me, “Be very careful in your conversations with that man because he comes from a family where they all sold out the insurgents.”

I graduated from the physics department, the department of theoretical physics. At school, I taught physics and a little astronomy. I organized the instrumental support for a children’s music ensemble there. But I only worked there for less than two years and one more quarter. I got into a conflict with the administration and submitted my resignation. The director and I almost came to blows. I didn’t fit into that system. I didn’t yet understand that the system was: “I’m the boss, you’re the fool.” I didn’t want to understand or accept that system. Although the director himself treated me well until this conflict, because he was my father’s cousin. But a conflict is a conflict, and someone has to come out the winner. I didn’t want to be the loser, which meant I had to leave.

V. V. Ovsienko: And what were your relationships with the students like?

I. I. Makar: Oh, very good relationships, very good. I loved to work with them. Maybe I wasn’t such a great teacher, but one way or another, I prepared several Olympiad winners—they took second place in the raion. For a remote village school, that’s not bad. Even my F-students—I regularly gave them F’s in the quarters for intimidation, one quarter I’d give one, the next I wouldn’t—when they met me later, and I was carrying a heavy suitcase from the bus, they helped me carry it halfway home. So everything was normal in that respect; I had very good relationships with the students, no conflicts with parents or students.

In early 1982, in January, I got a job at Lvivnerhoremont—now Lvivatomenerhoremont. I didn’t work there for very long. I went to one power plant, then another—doing flaw detection. That’s checking welds with non-destructive testing. I went to the Novovoronezh Nuclear Power Plant. We were doing repairs there from Lvivenerhoremont, and I went with two flaw detection specialists to inspect the welds. It’s near Voronezh. We X-rayed the welds on the oil system—the photographs show inclusions, defects in the welding. The three of us looked at it—we’ll write a report to have it re-welded. But I stepped away for a moment, and when I returned, my guys were “under the influence.” I ask, what’s this? They say, come on, have some, they gave us some alcohol to clean the film. They’d already “cleaned” it… No, I say, guys, I’m not cleaning any film. I wasn’t a fan of that. I ask if they’ve made their conclusion yet. “Oh no, everything’s fine here, it’s minor, it’ll pass.” So “everything’s fine” now—they’d been bought off. Well, you know what an atom is? Even though it was just the oil system, things start with small details. And it’s a nuclear plant, what could be the consequences? I got into a conflict with the flaw detection specialists and the plant’s management. And there the system is simple: I didn’t please them—so threats followed: we’ll throw you out the window. I called the technologist from Lviv, the head of the laboratory. I saw that this was trouble, they really could beat me up and throw me out the window, so I took a series of connections and went to Lviv myself. They arrived, the разбирательства began, but it turned out that this flaw detection specialist was a communist. Well, how could they trust a non-Party engineer, and such an unreliable one at that? In the end, I turned out to be not quite right.

It was right around then that I met my future wife; we decided to get married immediately. We had known each other for a month or two at most.

V. V. Ovsienko: And what is her name?

I. I. Makar: Halyna.

V. V. Ovsienko: And where did you meet? Somewhere around there?

I. I. Makar: Well, yes, we were riding a bus to our home region, to our parents. She’s from the neighboring village of Ploske, in the same village council. From a farmstead, too. We were riding the bus on a Friday, and we agreed that on Sunday, I would pick her up on my motorcycle and take her to the bus. I had a motorcycle; I used to ride it to work at the school. I came for her on the motorcycle, but I couldn’t get all the way to her house because the roads in our mountains are such that you can’t get through. I had to walk a bit. By the time we rode the motorcycle down the mountain, we had decided to get married. It was that simple. We made an agreement. I went to that Novovoronezh Nuclear Power Plant for two weeks, came back, we submitted our application, and a few days later, we signed the papers. I got married on May 8, 1982. I did warn her, though. I said, you know, Halya, I have some sins against the authorities. What sins? Knowing roughly that people were imprisoned for such sins, I allowed for the possibility that I, too, might be imprisoned. I said it as if in passing, but I remember we had such a conversation. A gypsy woman had even told my fortune once. It seems strange, funny: “You will be in a state-owned house one day. Not for long, but you will.” I took it to mean that I had to endure whatever might await me.

I resigned from there and moved to Boryslav because my wife lived in Boryslav. The communists won the conflict because the brigade leader was a Party member, even though he was a drunk. And I resigned. I worked as an engineer at the Boryslav Foundry and Mechanical Plant. I got married in May, and from about June 1982, I started working there. I worked for about four months, until about September, as an engineer in the foundry and mechanical shop. Later, I got a job as a technician in a geophysical expedition. I had a bit of a penchant for tourism. We would go out into the fields, mainly measuring the state of wells, specifically their angle of inclination, the release of associated gases, and monitoring the drilling process. From there, they started sending us on business trips, on a rotational basis, to Novyi Urengoy. The work was actually quite good because I was my own boss. But there was nowhere to live…

V. V. Ovsienko: What do you mean there wasn’t? Rotational work—that means you go for a certain period of time, right?

I. I. Makar: Yes, but there was practically nowhere to return to. Her parents and mine lived on farmsteads; what kind of life was that… And in Boryslav, she worked as an accountant, and an apartment was nowhere in sight. So I decided to earn some money or maybe get an apartment there.

V. V. Ovsienko: Where there? In Urengoy?

I. I. Makar: In Novyi Urengoy, yes.

V. V. Ovsienko: You even considered that?

I. I. Makar: Well, of course. That’s why I went for it. A job found me there—I was hired as the head of the radiation safety service at the Urengoytruboprovodstroy trust. That is, right at the very beginning of that pipeline branch “Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhhorod,” where it started from the wells. That trust was building the pipeline. And our enterprise was directly responsible for inspecting the welds. I served as the acting head of the radiation safety service.

And there I had a major conflict when I saw how people’s health was being neglected. Those flaw detection specialists, after working for a few years, would find some driver or someone else to go give blood for analysis in their place. This flaw detector—a container, a source with radioactive elements. They might literally keep it under their beds. There was practically no real control at all; the gamma storage facilities where they were kept were completely unguarded. It was simply horrifying. I tried to bring some order there somehow. As a physicist, I knew what it smelled like, but bringing order interfered with the work. That is, bringing order automatically reduced the intensity of the work. Something had to be cleaned up, something had to be put in storage. This bureaucratic work had to be done. I wanted to establish order, and they immediately started slapping my hands. A conflict flared up. But the personnel department, even when I was hired, knew that I was a “disloyal element.” I went to the prosecutor’s office, and the prosecutor’s office was interested in it until my head of personnel went to the prosecutor’s office. As soon as she went there, the tune changed in an instant, and suddenly I was to blame for something. They threatened me to the point where the head of the trust said: “You understand, around here in the spring, they find ‘snowdrops.’ Anything can happen. And anything can happen to you.” At that point, there was no turning back. I even went to the secretary of the Urengoy City Party Committee. But for them, what was important was not what I was saying, but who I was. That’s how I understood it. That I was an enemy was apparently a foregone conclusion. To them, I was “not one of their own”—and that was that. And I began to feel it in my gut that the circle was tightening. Aha, it’s tightening—I’ll go on the offensive. I wrote a letter to the KGB: so and so, such negligence threatens state security. They called me into the KGB; I remember an authorized officer, Panov, spoke with me in the reception area. I later knew Ukrainian KGB officers in Lviv—how much smarter and more decent a man he was. At least he said: “Keep fighting; even we can’t do everything. But you’d be better off leaving this place. It’s unlikely you’ll be able to accomplish anything here.” I at least warned them about the situation. Besides, in doing so, I demonstrated my loyalty to the system by saying that I wanted to bring order to the state. I sensed that they really knew much more about me than I could imagine. Because they had everything on me—my biography, everything, everything.

Sometime just before March 8, 1984—and the frosts there were still severe… So, I was hired there at the end of November 1983, fought through the winter, and on March 5, they fire me from my job for “absenteeism,” seal and lock my trailer where I lived, leaving me with only the clothes on my back, with nowhere to even spend the night. I become a homeless person. All my belongings are in the trailer. And then comes March 8—a holiday, which means Saturday, Sunday—several days. Well, you could just howl. Everything starts to reek, I’m starting to stink. Like a homeless person, because there’s nowhere to wash, it’s Siberia. I complained to the Komsomol bureau, and some Komsomol member opened up a utility room for me, which didn’t even have heating. But at least it had single-pane windows. Because there, in Siberia, windows usually have three panes of glass. And there was also a bed frame and a mattress. Somehow I managed to get by there for three days, sleeping in my clothes.

They fired me for supposedly being absent from work. But I couldn’t have been absent in principle because I lived in the trailer, and the other half was my office. I was indeed sick for a few days, but I didn’t have a doctor’s note for it. My throat was sore, and I sat in my office doing paperwork. I knew they were watching me, so every day I made sure to leave a mark at the sites—a report here, an order there, something else, so it would be constantly visible that some concrete work was being done. One way or another, they later reinstated me at work, but instantly, a few days later, they demoted me for three months. They sent me to a site far north of Novyi Urengoy. They sent me there as a foreman. There were already two foremen there. There were about seven workers, two foremen, one superintendent, and they sent me there as the third foreman. No duties, nothing. The only duty was to show up in the morning, check in that I was there, and nothing more. Nothing to read, nothing, and no right to leave. So that you don’t travel around Urengoy, so you don’t go to various offices—here you go…

V. V. Ovsienko: Like exile.

I. I. Makar: …something like exile. But then they decided to get rid of me in a different way. A lab assistant was having a birthday. I was supposedly reinstated to the position of superintendent because the previous one had gone on vacation. And then this birthday. She wanted to have it at lunchtime. No, I say, let the workday end… I notice they’re showing me a lot of respect, “Ivan Ivanovych…” And there, the work was in hazardous conditions, so the workday ended at four; we had a one-hour shorter day. I waited until that time, went there, they poured me one shot, then a second—two small 100-gram shots. I look—something’s not right, I’m not usually that weak when it comes to this stuff, I could drink it by the kilogram on occasion… But I see—something’s wrong. I say I’m just stepping out for a moment. And—bam—literally on autopilot, as they say, I staggered to my trailer. I had a Bashkir friend there. He had gone to the night shift. So I didn’t go to my own place, but to his bunk. It was literally around five o’clock or even earlier, and I locked myself in there.

I wake up in the morning around eight o’clock. My head is splitting. They must have slipped some poison in my drink or something; you just don’t get like this from a couple of small shots… And my Bashkir bunkmate is already knocking, saying: “Your boss came by yesterday, he was looking for you, but I didn’t tell him where you were.” They wanted to set it up to accuse me of drinking on the job, to take me to the sobering-up station. But one way or another, they documented it, took statements from those who were with me. They all repented for having a birthday party for so-and-so with the superintendent. So they repented, and I was fired.

V. V. Ovsienko: That was right during the anti-alcohol campaign. The Andropov regime.

I. I. Makar: Yes. In June 1984, they fire me again with cause. I don’t remember now if it was Chernenko or Andropov… Andropov had just died then. Andropov died in the winter, around February, and I was fired in June. I went to Moscow, I go to the Central Committee, and they tell me: “Well, how can it be that everyone is bad, and only you are good?” That was the argument. That I was the “white crow.” I wrote a few more letters here and there, but one way or another, I needed to work. I tried to find something in our areas, in the Carpathians, maybe teaching somewhere—they wouldn’t hire me. They wouldn’t hire me for other jobs because of two dismissals for cause in my work-record book. I have a very interesting work-record book in general. Well, with a record like that, no one will even let you on their doorstep—it’s obvious you’re unreliable. But I got lucky. My younger brother was returning from the army. He had taught for a year in Odesa Oblast. They drafted him into the navy. He had proven himself to be a very good teacher, so they held his position for him at that school. I tell him I have nowhere to work. And he says he’ll try to get a job here, in our area. If he gets a job here, he’ll send a telegram to the Shyriaieve raion center, general delivery, so that I, as his brother, can take his place.

And indeed, he got a job in the neighboring village teaching geography and sent a telegram to Odesa Oblast. I went to the raion department of education, said that my brother had stayed there, and here I am, a ready-made physics teacher. But I don’t show my work-record book; I say my work-record book is in Urengoy, but I want to teach, you have a position here, here’s my diploma, everything is in order. They say, excellent, we need people like you, go to the school where my younger brother used to work. This was the Novoandriivka eight-year school, Shyriaieve Raion, Odesa Oblast.

In August 1984, I managed to get in there. Basically, I got the job through deceit, but that couldn’t last long. My desire to be a respectable citizen was my undoing.

V. V. Ovsienko: How so?

I. I. Makar: They received me wonderfully there; I had a full teaching load and even extra work in the workshop—I do a bit of carpentry myself. I even organized a small sopilka ensemble at the school. Everything was fine. My undoing, as I said, was my desire to be a respectable citizen. I needed to go to Boryslav, give my passport to a friend who was going to Urengoy so he could de-register me from there, so I could register here, in Shyriaieve Raion, to be a law-abiding citizen. I had barely registered when the local party organizer tells me (she had previously taught at the school, was the school director for many years): “Oh,” she says, “the KGB has been asking about you.”

I started to shake. Can you believe it—I’m working as a teacher in a village with only 47 children in the school, a tiny eight-year school, a remote village, doing some carpentry work for the kolkhoz on the side—and the KGB is interested! There’s no one to conduct “subversive activities” with there. And I was already starting to put down roots, starting to feel independent. The carpentry at the kolkhoz, people coming to me for help, I no longer depended on how many hours they gave me at school. I started to get into beekeeping a bit, to be a somewhat independent man.

V. V. Ovsienko: Well, and your wife?

I. I. Makar: And where would I put my wife? I wanted to earn a little house for myself at the kolkhoz. The head of the kolkhoz had already promised to give me a house from the kolkhoz. You can’t build one yourself. I worked dutifully for two months on the kolkhoz chairman’s house, for free. But they kicked me out of there too.

V. V. Ovsienko: And very quickly?

I. I. Makar: I worked at that school for two years. In 1986, they transferred me to another school there, in Shyriaieve Raion. They transferred me as a teacher of physics and physical education. They gave me more physical education because I had then enrolled in a correspondence course in physical education at the Odesa Pedagogical Institute. They transferred me there because there was supposedly no place for me at the previous school.

V. V. Ovsienko: And what is the name of that village?

I. I. Makar: Sakhanske. In the same raion. Well, there’s nothing there, you have no base to get housing. They put me in such a tiny room at the school—do what you want. And I also needed to help my child with something.

V. V. Ovsienko: And what year was your child born?

I. I. Makar: 1983. Natalka.

V. V. Ovsienko: The one we saw today?

I. I. Makar: No, that was Olha we saw. Natalka is actually taking her final exam today; she’s finishing eleventh grade, a graduate. And this is Olha, born in 1991. She’s a deputy’s daughter.

They transferred me there by force. I started another war there because they don’t give a person a chance to just live. Inspections from the oblast started; I even went to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. Sometime at the end of 1986, in winter. Or early 1987. I went to their reception office at the Central Committee to complain. I came out onto Khreshchatyk in Kyiv, asked where the Central Committee was, and a passerby showed me: “There it is, that ‘hornet’s nest.’” It was already a “hornet’s nest.” Well, I thought, Kyivans already have a normal perception of it. I went to that “hornet’s nest”—and heard almost the same phrase: “How can it be that everyone is bad, and you alone are good?”

I left there, thinking I wouldn’t find any justice here. I thought I’d just have to make it through to the summer and get out of here. The workload was very light, the salary was small, and there was nowhere to earn extra money.

One day I came to visit my friends in the raion center. One of them was the director of the House of Young Naturalists, and others worked at the House of Young Naturalists and the House of Pioneers. And I happened to arrive just as the head of the KGB was giving a lecture for the methodologists and staff about metalheads and hippies. He was showing a metalhead’s jacket—explaining how harmful it was. He finished his talk, the women who had farms at home listened and then went home. Only the young people were left to ask questions. The director of the House of Young Naturalists says: “And what is there for you to do here, in Shyriaieve Raion, why keep a KGB apparatus here? We have a small butter factory, a few kolkhozes, and practically nothing else here, just the town of Shyriaieve.” He says: “What do you mean? You understand, we have three former Banderites in our raion!” So, the apparatus must be maintained—because there are three former Banderites. “There’s one, in Sakhanske, who called the chairman of the village council a bandit! And in that same Sakhanske, there’s also a teacher named Makar…” And he looks at me like that. He didn’t say what exactly that Makar had done. But Makar was a “lefty!” You know, I started to shake. But there was still, obviously, fear of the KGB, because my friends said that when I was asking him questions, there was a little tremble in my voice and my knees were shaking. I say, you know, we have a mafia in our raion—that’s what you should be dealing with, you know, earn an extra star on your shoulder. “Who, where?” – “Well,” I say, “the secretary of the raion party committee, the head of the raion executive committee, the head of the raion education department—a mafia.” He says: “Do you understand what you’re saying?” – “Yes,” I say, “I understand, and I stand by my words.” He says: “Come see me next week with your passport.”

Well, what could I do—an order from the KGB. I go there with my passport, hand him the passport—he has nothing to say to me. He took the passport, shoved it in a drawer, and said: “Go.” What could he have said to me? I have arguments for everything, and he, apart from hackneyed commie clichés, has nothing. For about a month and a half, I went to get my passport back: “Give me back my passport.” They gave me the runaround. Then they passed my passport to the police. The only positive thing: that was the moment I stopped being afraid of them. When I saw a live man in front of me who had no arguments, who was afraid of me himself, who had become so small. Your only argument is that you have power and you shoved my passport in a drawer, and then I have to run around and beg until the police finally gave it back to me. But I already felt that the circle was tightening—they broke the windows in the shack where I lived. After that, I went into a store—they were provoking a conflict with me. I think, there’s going to be trouble here. I see the circle is tightening, they’re looking for a way to get me… So I often went to the raion center, stayed overnight with my colleagues in the dormitory, or sometimes just slept in a tent in a field.

I found out that the same Petro Zhuk had already become a department head at the Special Design and Technology Bureau of the Institute of Applied Problems of Mechanics and Mathematics. This was the institute that was then headed by Academician Pidstryhach, now deceased. And that Petro Zhuk offered me a position as a first-category design engineer at his institute, so I should come work for him. I agreed. But I was already, so to speak, taught by experience, knowing our good Soviet government, so I went to settle my accounts there, in Odesa Oblast. I’m settling up, and the head of the raion education department asks me: “And where are you going?” And I say that I’m going to the Altai, that I have an aunt in Barnaul who is the executive secretary of an institute, and I’ll be teaching students. Just like that, “off the top of my head,”—I had once been on a “shabashka” [moonlighting job] in Barnaul. I thought, let them look for me there, not in Lviv. Well, the fact that I was going to Lviv—I would first visit my wife and parents. So, they would be waiting for me in the Altai, and I would pop up in another place. I told him that, and he was so pleased that he knew where I was going, that I had told him so “confidentially.”

I went to Lviv, managed to get registered in a dormitory somehow because a university friend of mine, Roman Hrabovsky, was a party organizer in some construction trust. I quickly—one, two—got everything sorted out. And then, when my file arrived, that director, Komisarchuk, was horrified that they had hired such an anti-Soviet element. But, to be honest, I was already so worn out by this whole system… When Hrabovsky asked me if I would get involved in politics, I told him sincerely: “Only science and sport.” That was, I think, in July 1987. I had worked for three years in Shyriaieve Raion and was sincerely convinced that I would become a normal scientist, that I would engage in science and sport. I really did start running intensively in the mornings, signed up for swimming at the pool, and sat in the library. I really wanted to do my dissertation, and I had already started.

V. V. Ovsienko: You were in the dormitory—but where was your wife?

I. I. Makar: My wife was living in Boryslav. By then, her parents had somehow scraped together some money and bought a small house in Boryslav. Everything seemed to be going well until my friend Ihor Yurchyshyn, during a discussion after the workday, said to me: “What are you bothering me with all this price formation for? There’s a discussion club here at the Builders’ House.” And that was literally 50 meters from my work, that Builders’ House in Lviv. Such a coincidence. He says, go to that Builders’ House and debate as much as you want. And so, without any, as they say, ulterior motive, I went to that discussion club. And it was discussing the directions of democratization of society. The language there was the “common language” [Russian], and they discussed democratic “common” topics. I didn’t want to speak the “common language,” so I interjected in Ukrainian, and they looked at me with such spite, with a smirk or with contempt—he came here, doesn’t know the “common language.” But, you know, you just don’t want to speak a foreign language in your own land anymore. Well, why? For what reason?

The discussions were on Thursdays; I think I came to the meetings twice, and on about the third time, Bohdan Horyn came there.

V. V. Ovsienko: What month was this?

I. I. Makar: This was 1987, around November. Or early December. Bohdan Horyn already had a prepared lecture on the state of Ukrainian affairs in general. The things he said… Where did the man get such information?

V. V. Ovsienko: Like a revelation.

I. I. Makar: Especially since I didn’t even have the habit of listening to Radio Liberty. That is, I was active, I didn’t like things, I felt constrained living in this world. In general, I’ll tell you something, Mr. Vasyl. I came to the national movement and the national idea not with my soul, but with my mind. Until I reached a conscious age, I was raised on those standards—Valya Kotik and Pavka Morozov. And when Horyn read that… I remember then, I was walking him home and begging him for that “Ukrainian Herald,” how could I read that “Herald.”

V. V. Ovsienko: Chornovil revived the journal “Ukrainian Herald” in July-August 1987.

I. I. Makar: Yes. And Horyn looked at me so suspiciously, as if I were a KGB agent. He was somewhat wary, especially since I’m a physically well-built guy; I was still involved in physical training then, looked pretty good, and he’s such a small fellow. Well, he was keeping his distance from me. But one way or another, he told me to come to the Picture Gallery where he worked, and he would give it to me. I went there one day, and I remember this gesture of his. He was giving a tour in Russian; apparently, the visitors were from Russia. But when I stood there, he said to me: “Mr. Ivan, please wait a moment, I’ll be finished shortly.” That is, he interrupted his lecture. You know, that gesture was so pleasant: he showed the foreigners that we were here on our own land. He gave me the last copy of the “Ukrainian Herald,” typed on a typewriter. You could make out every third word, and the rest you had to guess. But one way or another, he gave me that “Herald.” My friends and I read it. That was my first acquaintance with representatives of the national movement; he was the first—Bohdan Horyn, somewhere in December 1987. And later, maybe in January, I don’t remember exactly, Mykhailo came. They began to collect signatures for the release of political prisoners who were still in the camps, including, I think, you were there. I didn’t really know then that anyone was imprisoned. Me, a person who wanted to do science and had a talent for it—the system itself pushed me into dissidence. Automatically. A person who had no particular humanitarian inclinations—the system itself pushed him toward dissidence.

V. V. Ovsienko: And that discussion club, was it affiliated with some institution? Can you give the address where it operated?

I. I. Makar: It was the Builders’ House, on Stefanyk Street. Many Lviv events are connected with it. It was about 50 meters from my work at 15 Lermontov Street—now Dzhokhar Dudayev Street.

When Mykhailo Horyn came, we were collecting signatures there. As I understand it, those signatures were not so much important for the dissidents themselves, or for the authorities, as it was important to get a person to sign, that is, to show solidarity with those who were imprisoned. But one way or another, the Komsomol members came and stole that letter…

V. V. Ovsienko: The sheet with the signatures?

I. I. Makar: Yes, the Komsomol members stole that sheet. After that, I got a scolding from Mykhailo Horyn. He says, and where were you? Well, I say, Mr. Mykhailo, a whole crowd of those Komsomol members came to that discussion club…

Then—sometime in January 1988—Viacheslav Chornovil came and gave out a few duplicated sheets of paper—theses for a future discussion. He asked for them to be passed on to the oblast party committee so they would send their own lecturer who could debate. So, Viacheslav Chornovil came with prepared theses for his future speech and challenged an official representative from the oblast party committee to a debate. It was then that the Komsomol members stole that signature sheet in defense of you, too, Mr. Vasyl. You would have served one day less, but I didn’t watch it closely enough. Although I doubt anyone even looked at those signatures. It was more for those who signed than for those who were imprisoned.

V. V. Ovsienko: Yes, one had to dare to cross that line.

I. I. Makar: An act of civic expression. You become a citizen; you cease to be a slave. The next meeting was scheduled—unfortunately, I don’t remember the date, Mr. Bohdan Horyn is more meticulous, he has everything like an archivist—the following Thursday we arrive, and the Builders’ House is occupied. It turns out the Theater on Podil from Kyiv had arrived, and they were given the venue to perform. The authorities wanted to organize a sort of inter-ethnic conflict. The Theater on Podil, I believe, is a Jewish theater, so the authorities wanted to organize an inter-ethnic conflict and warm their hands on it. Well, the people didn’t fall for the conflict.

A whole crowd of people gathered in the courtyard. Viacheslav handed out leaflets with what he was going to say, and I say: “Mr. Viacheslav, well, why didn’t you call on people to gather at the Franko monument? They don’t want us here—so the discussion will be at the Franko monument. You can lead the people there and calmly say everything you want from that pedestal.” Today, that’s simple. Freedom of speech, meetings, and demonstrations… But he says: “And why didn’t you do it?” Why didn’t I do it? Well, I didn’t do it because I didn’t feel like a leader in that situation. That is, I felt I was playing a somewhat secondary role. There, say, to say something strong… Because my education in the humanities at that time clearly lagged behind any of them—Chornovil, the Horyns. Especially since, having an education in physics and having gone through Urengoy, my language was impure, quite cluttered. These technical books were mostly in Russian, and no matter how you resisted, your language was maimed. With those words, “and why didn’t you do it,” he essentially told me: “I’ve already served my time, it’s time for others to sit.” So I got a push, you could say, I received a visa: you are allowed, and you can do it. That is, it’s time for your generation to take over this function—of going to prison.

After that conversation, I was already morally prepared to lead people to a protest, to the first rally. But then the people dispersed. A few more times people tried to get into the Builders’ House on Thursdays, but they weren’t allowed in. Since the discussions were getting out of the authorities’ control, the authorities no longer wanted to take part in them. And it began to fizzle out. I met with the organizers of that discussion club, but I became convinced, I felt, that most of them were not the organizers; they were organized by someone else. This continued until the beginning of June.

V. V. Ovsienko: I believe the first major rally took place on June 16.

I. I. Makar: It all started on a Monday, I think June 13. Sometime around six in the evening, I left work at 15 Lermontov Street (now Dzhokhar Dudayev), where my SDB was, and my friend Yurchyshyn told me that they were supposed to be organizing some Ukrainian Language Society today. I hadn’t been informed about this, even though I was already connected with those “extremists.” The Kalynets couple was there, Stefania Shabatura, the late Vasyl Repetylo—a friend of mine, a physics graduate from the same year as me—engineers from Lviv enterprises, university professors, and also the official figures—Roman Ivanychuk and so on. They came to the Builders’ House. They had supposedly been promised that they would be given a room to hold the founding meeting of the Ukrainian Language Society. They arrived, and the Builders’ House was locked. They say: let’s go to Adam Martyniuk—he was the second secretary of the city party committee at the time—and tell him that we’re not extremists, that we’re only for the preservation of the language—such were the lamentations there.

V. V. Ovsienko: Ivan Makar, May 29, 2000, cassette two.

I. I. Makar: I happened to arrive when they started talking about asking Martyniuk to provide a venue to create the Ukrainian Language Society. You know, I, a bit brazenly, a bit, perhaps, with bravado—still young—said that we shouldn’t ask. I was already ready to demand. I stood before them and in a loud voice said: “Who are we—sheep or Ukrainians? If they don’t open this House for us in five minutes, we will go to the Franko monument and hold our founding meeting there.” This was said with such confidence by a man who knew what to do, so that everyone understood that there was a leader. There was a mass—but it lacked a leader. Just like in Vysotsky’s song. It’s the psychology of a crowd: a man appeared who knew with absolute certainty what to do—that’s it, we’re going now, five minutes have passed, they haven’t opened, let’s go. We went to the Franko monument. Here, Stefania Shabatura took me by the arm, and we stroll along lightly, and the people—we look back—whether they want to or not, they are also strolling behind us. It was a very small group, about 30 people, that had gathered in front of the Builders’ House. But as we walk along Stefanyk Street, over there, past the Stefanyk Library, past the main post office—everyone asks where this organized crowd is heading, and since it’s the end of the workday, the group gradually grows.

We arrive at the Franko monument. I say: “Alright, who’s here?” A kind of hooliganism, a bravado, stirred within me: “Alright, who among you are the organizers? Get up here on the pedestal, get up, stand… Alright, the list—who’s on it? Read out the list of who’s here, to create the society? Right, everyone ‘for’? Everyone’s ‘for.’” I’m kind of directing from below…

V. V. Ovsienko: And who was leading?

I. I. Makar: And the leader was supposedly one of the engineers, who later became one of the most active members of the Society, Ihor Melnyk. Roman Ivanychuk was among the leaders there. They were on that pedestal, at the foot of the Franko monument, where the rallies later took place. They climbed up, but it was unusual for them, because they were doing something… You know, their legs were trembling slightly. And I’m like: “Don’t let your legs tremble there, just read, read!” And they, as if under hypnosis, like a rabbit in the jaws of a boa constrictor… Well, unclean spirits were guiding me… I don’t know, clean, unclean…

V. V. Ovsienko: Some force was guiding you.

I. I. Makar: That is, I was guided not so much by noble thoughts as by simple bravado, the fact that, “you see, my legs aren’t trembling, but yours are.” “Alright, so, who do you have in the initiative group? We’re electing a council, read out the list. Yes, we’re electing. Who’s ‘for’…” You see, I was effectively directing from below, in such a brazen manner… Well, I say, the council is elected, go to the gazebo, solve your issues there, and we’ll stay here. And then people started speaking from the pedestal. Some bard came, took the platform, started singing Lemko songs, started talking about how Lemko culture was destroyed, about Operation Vistula. Then someone else came out, started reading poems. Then some Lviv art teacher came out—I don’t remember his name. He says, here are the delegates going to the 19th Party Conference in Moscow. They’re going to the Party Conference, but they don’t ask us, the people, what they’re going with to decide our fate? They should have asked us… Until then, it was “the people and the party are one,” meaning the party was supposedly the representative of the people. There wasn’t yet such a complete psychological separation. For you, after you had served your time, there was a psychological separation, that the party wasn’t so dear…

V. V. Ovsienko: That it was a hostile force to us.

I. I. Makar: But here it was normal: they’re going, they say they are the people’s party, so let them consult with the people about what they are going with. And it was expected that the 19th Party Conference would be decisive in the life of the entire Union. And then an idea struck me. I climb onto the platform and say: “So, on Thursday, here, at this spot, at seven o’clock, there will be a meeting with the delegates to the Party Conference.”

V. V. Ovsienko: So, without knowing anything and without having arranged anything with anyone?

I. I. Makar: No, I just announced it like that: “There will be a meeting here with the delegates of the Party Conference, on Thursday.” Just like that, “off the top of my head.”

V. V. Ovsienko: What date was that?

I. I. Makar: On Thursday. You know, there were many of those Thursdays… But this, the creation of the Ukrainian Language Society, took place on a Monday, maybe June 13…

V. V. Ovsienko: I believe those first big meetings were on August 16. That’s how it’s recorded in history.

I. I. Makar: It’s hard for me to say now. But that initiative group for the creation of the Ukrainian Language Society was on a Monday. Evidently, the 13th. A council was elected, this structure elects its governing bodies in the gazebo, the Society exists. I announced the meeting with the Party Conference delegates for Thursday. I announced it and said: “We need to elect an initiative group.” Down below was Ihor Derkach, Oksana Krainyk was there, and we created an initiative group. I was the head of the group, and there were two members—Derkach and Oksana Krainyk. By the way, she is the daughter of the dissident Krainyk, what’s his name—Vasyl Krainyk, or what?

V. V. Ovsienko: Mykola.

I. I. Makar: I say that I take it upon myself to inform the delegates about this. Everything proceeds in its own course. Wait, it’s not all so simple, I’ll tell you…

V. V. Ovsienko: “To the Director of the SDB…”

I. I. Makar: “…Komisarchuk. Application. I request a day off on 20.06.1988 and 21.06.1988 for work done on 19.06.1988 (which was, accordingly, a Sunday). The day off is needed for the organization of a rally in support of perestroika.” Further: “To the Director of the SDB…” and so on. “I request a three-day unpaid leave in connection with the organization of a rally-meeting with the delegates of the XIX Party Conference of the CPSU. The rally will be dedicated to the support of perestroika. I will be absent from work from 20.06 to 22.06.”

This means that the meeting with the Party Conference delegates was, after all, on the 23rd, evidently a Thursday. There is a document. If it was Monday, June 13, and I wrote the application on June 17, then I scheduled it for Thursday the 23rd. So, the founding meeting of the Ukrainian Language Society was on the 13th, and the meeting was to take place on Thursday the 23rd.

On June 17, I submitted the application, and the department head, Zhuk… No, Zhuk was on vacation then, Ihor Yurchyshyn was filling in for him, he wrote “no objection” and then “in accordance with the instructions on providing leave without pay.” They granted me leave so that I could prepare for the meeting with the Party Conference delegates.

What do the authorities do? The authorities consider that the Ukrainian Language Society was created, so to speak, illegally. The authorities declare the meeting illegal and want to hold a new founding meeting on June 20 and provide that ill-fated Builders’ House. And a whole crowd of people came there. If the first time about 30 people came, then this time the hall was packed.

V. V. Ovsienko: And all our people, right?

I. I. Makar: Well, where else? They can’t gather that many of their own employees. On June 20, a whole bunch of our people come. These were real people, not yet worn out by rallies; there was a purity, an idealism, none of the superficial dirt that came later. “Well, then, we will elect a council.” I say: “Let’s also bring Mykhailo Horyn into the council.” But he hesitates somehow. In principle, maybe he was right, because Mykhailo Horyn had just been released from prison. And someone proposed electing me. Mykhailo Horyn turned out to be a prudent man, he says: “My brother Bohdan has a legal position, a tour guide, a research associate at the art gallery. Let him be, I withdraw my candidacy.” But I didn’t withdraw mine. And people were shouting: “Makar!” Because they already knew me from the discussion club. Despite the fact that the initiative group there didn’t like me, I still became a member of the first council of the Ukrainian Language Society.

I’ll tell you something. Just as they didn’t invite me when the report-and-election conference was held a year later (meaning I was somehow redundant there from the very beginning), they also didn’t invite me to the celebration of the tenth anniversary of the Ukrainian Language Society in Lviv, even though I was a member of its first council, nor to the celebration of the tenth anniversary of the “Prosvita” Society here in Kyiv. I didn’t turn out right, I didn’t become a true “patriot.”

Actually, it was then that we started organizing such large events, like the commemoration of Charnetsky—a bishop of the Greek Catholic Church. In Lviv, any occasion would gather a circle of conscious people—some who could say something, others who only dared to listen.

So, later, Iryna Kalynets and Yaroslav Putko were co-opted into the initiative committee. The authorities decided that something had to be done. They summoned me to the city council and said, let’s make a speech, hold a meeting with the delegates to the Party Conference, but not on the street, but inside the Builders’ House. I said that people might not fit in there. The deputy head of the city executive committee, who was assigned this task, decided to drive the meeting from the street into the building, to make it more official. I say that I cannot make such a decision on my own; we have a collective body, a committee, I must consult with my colleagues. I go to Iryna—we had set up a headquarters at the Kalynets’ apartment. Kalynets’s wife says: you know what, you agree, and we’ll lead them out onto the street later. People will demand it—we’ll seem to be “for” the building, but the people will demand to be near the Franko monument. A cunning vixen: it turned out for the best, just as she advised. The authorities agreed; I delivered the notices to all those delegates, personally to the head of the regional KGB, the first secretary of the city party committee, and the regional party committee.

V. V. Ovsienko: And do you remember their names?

I. I. Makar: The first secretary of the regional party committee was Yakiv Petrovych Pohrebniak, of the city party committee—Volkov, the head of the regional KGB was Malik. There were several delegates from industry, scientists, like Ihor Rafailovych Yukhnovsky (by the way, a former professor of mine). We delivered those notices to them. And at night, Derkach and I ran around putting up announcements. Putko and Kalynets’s wife printed them on a typewriter, Oksana Krainyk added a little something with a marker, we bought glue, and Derkach and I ran around Lviv at night like two greyhounds, pasting them up. What’s interesting is that they were running after us too, but they still wanted to get a little sleep, while we worked conscientiously.

We came to the Franko monument. Iryna stood on the pedestal and said: “Let’s open the rally. But, you know, our Party Conference delegates have gone to the Builders’ House. And there are so many of us, will we fit in there?” The question was posed in such a way that the answer could only be unequivocal: “No, we won’t fit.” – “So, maybe we should call our delegates here?” – “Yes, call them!” – “So, maybe you’ll delegate me to go there, maybe they’ll listen to me, a woman?” It was decided that a woman should go. Well, Iryna Kalynets goes with a delegation to the Builders’ House.

V. V. Ovsienko: Is that somewhere nearby?

I. I. Makar: About half a kilometer from the Franko monument. She goes there, and I have the task of warming up the crowd here. It was such a beautiful day. I hadn’t worked up my anger yet. And to let someone else speak—you know, there’s no one, people are afraid. But in the end, I did manage to warm up the people a bit. We look, and Iryna appears with her entourage—with the Party Conference delegates.

V. V. Ovsienko: And in the meantime, were you saying something?

I. I. Makar: Yes, of course, I was warming up the people for the rally. We brought megaphones.

V. V. Ovsienko: This was sometime in the evening already, right?

I. I. Makar: Yes, it was around six or seven in the evening. They approach, and just then Viacheslav Chornovil, and Mykhailo, and Bohdan Horyn arrive. We already have something to say. We let the delegates speak, then our people.

V. V. Ovsienko: And who from our side spoke?

I. I. Makar: From our side then, Iryna Kalynets, Viacheslav Chornovil, Bohdan Horyn, Mykhailo Horyn, one of the activists at the time, Sheremet, I think Ihor Kalynets spoke…

V. V. Ovsienko: And who among the Party Conference delegates was there?

I. I. Makar: Volkov was there, and a few other delegates. But Malik, the head of the regional KGB, and Pohrebniak—the first secretary of the regional party committee—did not come. Yukhnovsky was there. He was the director of the Institute for Theoretical Physics here. A rather Ukrainianized institute. Oh, we gave it to them there! As they say, we beat them like punching bags, hammering away at those party members. The people, as they say, let themselves have their fill.

V. V. Ovsienko: And what issues were raised? The national question, the language issue?

I. I. Makar: Mainly the national and language issues. I was actually leading the rally. And what I remember is that it was so unusual for them that I was leading… Volkov thought that since he was the first secretary of the city party committee, he should be in charge here, but I considered that since I was the chairman of the initiative committee, I was in charge. Volkov himself, as a person, was not a bad man, but it was the system… And I sidelined Volkov, giving the floor in turn. We talked about the closure of national schools.

We scheduled the next rally for the following Thursday, June 30. Someone from below prompted me—I now understand it was a provocation, but I fell for it—near the stadium. Firstly, the Lviv stadium is far from the center, and secondly, that square near the stadium is like being in a bag. But the rally was scheduled there, and there was nothing to be done about it. The day of the rally approaches, and I feel that we have scared them. Rumors started about troops being brought in or something similar. I see that people are starting to avoid me. At the rally, Kalynets asks people to disperse because there will be a crush. I didn’t understand. I ask for the megaphone, but Putko and Kalynets won’t give it to me. I understood that something was wrong, it was clear they had been intimidated there, at the KGB, told that troops were being brought in. Although it’s unlikely that Iryna personally could be intimidated by anything. Obviously, they were scaring them, that people would be crushed there, or who knows what. They didn’t give me the microphone. And there was also this Viktoria Andreyeva from the newspaper “Leninska Molod” [Leninist Youth].

V. V. Ovsienko: “The progressive journalist.”

I. I. Makar: Yes, yes. She truly had a gift for oratory. She captivated with her voice. But I think to myself, I have a pretty good voice too. I stood up and with a loud voice condemned the authorities and said that the next rally is scheduled for July 7 at the Franko monument. I realized that the stadium was not the right place. The Franko monument has a good spot—a ready-made pedestal that elevates you. And people automatically flock there; it’s the city center, it’s hard to disorganize things there.

And another interesting thing. Just before the rally, I saw a bunch of police arrive at the square near the stadium and line up their cars. I see that people are afraid to come out onto the square. I approached the police chiefs, saying: “You see, people are afraid. Let’s move those cars over there into the bushes, and spread out a bit.” I went up to the highest-ranking officers and explained, gesturing confidently with my hands. And what’s interesting is: if a man gives an order, it means he has the authority to do so. Maybe this is some high-level game of perestroika, and I am the man appointed to lead this event. They obey, so politely they obey, running around, repositioning cars, waving their arms this way and that—well, it was a joke. The little devil in me started acting up again.

This was on June 30, at the stadium. It was then that I managed to announce the next rally for July 7.

V. V. Ovsienko: Well, and what happened near the stadium on the 30th?

I. I. Makar: On June 30, near the stadium, there were people as far as the eye could see.

V. V. Ovsienko: Well, just by eye, how many?

I. I. Makar: You know, it’s hard for me to estimate. On the 23rd, near the Franko monument, there were more than ten thousand. At that time, that wasn’t a lot. The largest crowd was in 1989 when the issue was the restoration and legalization of the Greek Catholic Church. They gathered up to half a million then. It’s just a blessing that the streets of Lviv are winding and there are no wide squares, because otherwise there would have been a terrible crush. And the second blessing is that there were no provocations, no sudden movements of the crowd, because a terrible judgment could have happened there. Well, near the stadium, maybe a hundred thousand were there. A huge number of people. I went up on a hill—wherever you could see, everything was covered with people. There were even fewer on July 7. And yet, I managed to announce the rally for July 7 then. And then the authorities decided to take the July 7 rally into their own hands.

V. V. Ovsienko: Well, and on June 30, who spoke there?

I. I. Makar: On June 30, there were practically no speeches. Iryna asked people to disperse, Putko said something, they didn’t give me the microphone, I said something into the crowd, Andreyeva said something from the other side, I think one of the Horyn brothers said something, because they also have quite loud voices. Practically everything was disorganized. It was the first serious failure. First and foremost, my failure. Because I fell for the idea of leading people to the stadium, and everything went wrong from there.

Here, Kalynets and I had a bit of a disagreement, a bit of a quarrel… Maybe she simply had more information, maybe someone had scared her, because there were indeed rumors that a tank division was stationed outside Lviv, which could really crush a protest. If they crushed one in Georgia, why couldn’t they crush one in Lviv? But, you know, it’s one thing to be a thirty-year-old lad who still lacks life experience, only has a fair amount of nerve, and another thing to be a person who has been through a bunch of camps, whose zeal is somewhat tempered. That is, her life experience was greater. I wouldn’t want to say that she was to blame, or anything else—simply, in her opinion, we had to disperse, and in my opinion, we still had to push through. Who knows? Even with today’s experience, it’s hard for me to say who was more right. But the authorities later wanted to take everything into their own hands.

On July 7, the authorities decided to take the initiative into their own hands. The application to hold the rally was made by the newspaper “Leninska Molod” and someone else, I think, some city Komsomol committee. They entrusted Viktoria Andreyeva with this. Andreyeva decided to coordinate with me—as if not to sideline me completely. We agreed on how to give the floor, so that everything would be democratic.

They told me that there wouldn’t be megaphones, but a car with microphones. On the 6th, I had just taken a group of university students with a professor to Peremyshlyany Raion to help us with our research… I felt it—I practically felt it every time they were about to take me. There’s this sixth sense. I felt that they were going to take me before the rally. But I decided not to let them. There’s a system—I used to hunt—the hare’s system. It runs straight and true, and then at one moment it jumps to the side—and the trail is lost. And I did the same, that is, I run straight, I go to Peremyshlyany Raion, I tell everyone I’m going on a business trip. But I’ll only be there on the 7th until noon, because at 7 o’clock I have to lead a rally in Lviv—I tell everyone this, everyone knows. I go with the students on July 6, place them in a summer camp, and say that I’ll lie down here by the door. And tomorrow I’m with you only until noon.

I arrived there, carefully studied the bus schedule in the direction of Lviv. And very early, around three or four in the morning, I put on my shoes, got dressed quietly, had everything ready, went out, and walked to the highway. It was about three kilometers away. I got to the highway from Rohatyn to Lviv, the first bus from Rohatyn came along, I got on the bus and rode. But I didn’t ride to Lviv—I thought, who knows, someone might report me, someone who’s watching me might call, and they’ll nab me in an instant. I rode to a fork in the road and jumped off to the side—I went to Bibrka. And then I went into Lviv and thought, where can I hide until seven o’clock? Well, I know for sure they’re going to take me, I just feel it! Where? Maybe lie low at the lake? The weather was nice, but they might spot me.

I think, ah, the best thing to do is go to my dormitory on Zelena Street. I went in so stealthily that even the person on duty didn’t see me, went into my room, and locked the door. Well, I think, now I’ll finally get some sleep after all the sleepless revolutionary nights. And I lay there until six o’clock, or half-past five. My worker neighbors had already come back, saying, we’re going to the rally, our Makar is leading it there.

I quietly go out and, as if under the protection of those workers, we all go there together. By the way, I guessed right: they caused such a commotion! On the seventh, they found my brother in Stryi, found my parents in the village—well, the man had disappeared! It would have been enough for them to detain me for two hours—well, some crime occurred, they suspected me, held me, and then: “Excuse us, Ivan Ivanovych.” Apparently, that was their plan. And I disappeared. A KGB agent came to my parents, and my mom says: “Well, what, lost his trail? You should have put salt on his tail.” She had also become a bit defiant. She’s a woman who never liked the authorities, in any era.

I arrive at the Franko monument, and the rally is already underway. On July 7, they started the rally half an hour early. And I arrived at seven, on schedule. I arrived, and people there were already shouting: “What have you done with Makar?” I walk up and say: “I am Makar, no problem.” You see, they couldn’t control everything! I climb onto the platform, push someone aside with my shoulder—I’m in charge here. You know, what mattered most was nerve. Perhaps I lack what is now called conventional intelligence. I arrived, so why should they not give me the floor or give me the floor—I announced that rally, didn’t I? I’m the chairman of the organizing committee. And that someone else wants to lead—that doesn’t concern me, that’s their problem. I took the microphone in my hands. The issue being discussed was where to place the monument to Shevchenko in the city. Then they stopped their speeches. I arrived and changed the tone. I say that this rally is illegal, the topic of the rally is announced—the formation of the Popular Front of Ukraine for Perestroika. Just as a hooligan in a domestic setting can completely disorganize everything, so I did at that rally.

V. V. Ovsienko: And where did this idea come from—to organize a Popular Front?

I. I. Makar: Well, in principle, this idea was already being discussed, it was already in the air, because fronts had already been formed in the Baltics. And what to form that front from? I had some list of organizations there—small organizations had already begun to form: the editorial offices of the journals “Kafedra,” “Ukrainskyi Visnyk,” there was the organization “Revival of the UGCC,” something else. I read them all out, and this was supposedly the initiative group for the creation of the Popular Front. The authorities feared organization as such the most. I give the floor in turn. But they won’t let Mykhailo Horyn, Viacheslav Chornovil, and Bohdan Horyn onto the platform. I have the microphone in my hands, and I have something to say to the people. Look, I say, they have been silencing us for years, and today they won’t let us speak. They did end up giving them the floor.

V. V. Ovsienko: The Horyns managed to speak there about the creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Union.

I. I. Makar: Yes, they managed. And it was then that they said where the monument to Shevchenko should be placed. The argument was that it should be between the Russian Lenin and the Pole Mickiewicz. And why should the Russian Lenin be in Lviv?

V. V. Ovsienko: That’s a good question. Chornovil, it seems, didn’t manage to speak then?

I. I. Makar: He spoke, he spoke. Actually, he was the one they manhandled the most there. I played it up the most with him, with Chornovil… Because when they were dragging him, I shouted that, you see, the commies shut his mouth in prisons for years, and they’re shutting it now. And they did give him the floor, but he had already strained his vocal cords and was practically croaking. And let’s be honest, he, the deceased, was not a good enough orator. From the point of view of oratory, even for those rallies. Compared to both Horyns—hardly anyone reached that level. They are orators. You could feel it in the crowd. What can I say, I’ll never be such an orator. These are people who can lay everything out systematically; they have extraordinary diction.

V. V. Ovsienko: They specially studied oratory.

I. I. Makar: I’ll say it again, Mykhailo and Bohdan are colossal orators. At that time, people didn’t know how to speak in public.

V. V. Ovsienko: They read from a piece of paper.

I. I. Makar: Yes. There weren’t those who could speak coherently on a specific topic and hold people’s attention for literally several tens of minutes. In that sense, they both stood out for their oratorial gift. No, it’s not that they studied it; it’s simply talent.

V. V. Ovsienko: A gift from God.

I. I. Makar: Yes. Besides, Bohdan did lead tours in the art gallery. It was evident—both the clarity of diction and the purity of language. Then, on July 7, it wasn’t easy to get anyone up to the platform. We announced speakers as agreed: Andreyeva announced the party members, and I announced the nationalists. And Lubkivsky wanted to speak and says to me: “Announce me, I don’t want Andreyeva to announce me.” And I say that I can’t announce you, how do I know what you’re going to say. In the end, it wasn’t Andreyeva and not me, but Oksana Krainyk who announced him. So, the three of us led that rally. Mostly, it was me, Andreyeva, and sometimes Oksana Krainyk who announced the speakers.

When I was given a note about the monuments, I say that we need to erect monuments in every village to the people who died for our idea. But they give me a second note: “Do you mean the Banderites?” I say: “Yes, I mean those who are called Banderites.” And that, in fact, was the main point of the accusation against me as an anti-Soviet, that I was the initiator of erecting monuments to the Banderites.

As announced, this rally lasted from seven to ten. In those three hours, Mr. Vasyl, I’ll tell you… I have never, in my whole life—and there have been times when I spent a day, once 26 hours unloading a wagon of saltpeter, of mineral fertilizers in Stryi, because as a student I needed to earn a living—I was not as tired in those 26 hours, which we worked with short breaks to eat something, as I was in those 3 hours. I was so tired that I couldn’t sit, or lie down, or walk; I was simply a ruin. For that revolution to happen in those people, it seemed to require a bravado, that we had already established our truth, to be able to defend it. And, by the way, I wasn’t the only one who was so tired. After the rally ended, both Horyns, Viacheslav, literally sat down on the grass near the club.

V. V. Ovsienko: So it was a colossal psychological strain.