Kondryukov

An Interview with V. O. Kondryukov

V.V. Ovsienko: Today is October 21, 2006. We are speaking with Mr. Vasyl Kondryukov. Also present are Oleksandr Drobakha and Mr. Kondryukov’s wife, Zinaida Tarasivna. We are recording this at the home of Vasyl Oleksandrovych Kondryukov. The conversation is being conducted by Vasyl Ovsienko.

V.O. Kondryukov: I was born in the Donbas. There was no one in my family who might have been involved in the national struggle. I was born on March 24, 1937, in the village of Vyshneve, Antratsyt Raion, Luhansk Oblast.

V.V. Ovsienko: What was your father?

V.O. Kondryukov: My father, Oleksandr Kyrsanovych Kondryukov, was born in 1910. Before the war, he worked on a collective farm, and right before the war, he worked in a mine. He went off to war and never returned. He was probably killed somewhere in 1941 or early 1942, right at the beginning of the war.

V.V. Ovsienko: And your mother?

V.O. Kondryukov: My mother was Maria Ivanivna Kondryukova, maiden name Kulishova. She was born in 1908. She worked her whole life on a collective farm. It was very hard back then, of course, we all know how they worked from morning till night. And after the war—I especially remember this—they were paid in workday units, and there was one year when they gave nothing for these units. Another year, they only gave 300 grams of bread.

V.V. Ovsienko: The kolkhozniks worked for “tally marks.”

V.O. Kondryukov: I started school around 1944 because I remember when the war ended, they led us around the village with flags. The partorg [Party organizer] happened to be walking past the school and said, “Why are you studying? Today is the day the war ended.” We immediately stopped our lessons. I was in the first grade, and we walked around the village with flags. I studied in my village until the seventh grade, and after the seventh grade, I had to walk seven kilometers to school in Mykhailivka, to the mine, where there was a ten-year school. I finished ten grades there. The seven-year school was in Ukrainian, and the 10-year school was in Russian. (This is stated more precisely in my memoirs).

V.V. Ovsienko: What year did you finish school?

V.O. Kondryukov: I finished school in 1955. That same year, I entered an electrification trade school. It was called the School of Agricultural Electrification; it was a one-year program. Then I started at a mine, walking eight kilometers to work and back. I studied for about a year, then worked at the mine for about a year, and went into the army in 1957.

V.V. Ovsienko: Where did you serve?

V.O. Kondryukov: I served in Ukraine. Our military unit was stationed here in Kyiv, in Darnytsia, but we went on assignments. I was at secret, and top-secret, facilities. I happened to be in Crimea, and in Uzin, where the strategic aviation was based, where even now there are wells filled with gasoline.

V.V. Ovsienko: Was it you who filled them with gasoline?

V.O. Kondryukov: No, I would arrive there for a month, a month and a half, or two. We did our work there, for example, runway lights or landing lights. We’d fix something, get it lit, or lay a cable, and then head back to Kyiv. We never stayed anywhere for long; we were like communications troops, but not a stroybat [construction battalion]. Something similar, but it wasn't a stroybat. I was in Stipok (Stepok is a military town in Zhytomyr Oblast near the villages of Ivnytsia and Volytsia), then in Crimea, where our secret address was Moscow-400, but we were located in Crimea.

V.V. Ovsienko: And how many years did you serve?

V.O. Kondryukov: Three years.

V.V. Ovsienko: Are you an only child, or do you have brothers and sisters? Please tell us their names, so it can be recorded.

V.O. Kondryukov: There were five of us children; I have two brothers and two sisters. Dmytro Oleksandrovych Kondryukov, born in 1929. He worked his whole life in the mines; he never worked on the collective farm. Mykola Oleksandrovych Kondryukov, born in 1931, also worked in the mines his entire life. Both of them worked in the mines for over 30 years and retired from there. Then Yevdokia Oleksandrivna Kondryukova; she also never worked on the collective farm. None of us children worked on the collective farm, except for my mother and father, and even my father switched to the mine. Yevdokia worked in a cafeteria, and then she got married and, I believe, didn't work anywhere after that. And then my youngest sister, Alla, who is no longer with us. She was born in 1941, she studied, finished ten grades, also walking 8 kilometers to school. Then she studied somewhere, I think in Alchevsk... Well, I'd have to remember, I can't recall. And then she got married, lived in Antratsyt (we’re from Antratsyt Raion), got sick there—liver cancer—and died. She’s been gone a long time, 8-10 years. I have the document.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what was your life like after the army?

V.O. Kondryukov: After the army, I went back to the mine, not the one I was at before, but a different one. There, I actually went through all the specializations: I started as an electrical fitter, then I wanted to do tunneling, I was in the OKR, then in the ROZ.

V.V. Ovsienko: What is OKR?

V.O. Kondryukov: OKR is Otdel Kapitalnykh Rabot [Department of Capital Works], and ROZ is Rabochiy Ochistnogo Zaboya [coalface worker], which in the old days was called a hewer. I worked there for about a year, then I got tired of it all, I just up and left, went wherever my eyes took me.

V.V. Ovsienko: And where did your eyes take you?

V.O. Kondryukov: My eyes led me to Kyiv. I was reading about Kremenchuk at the time, about Komsomolsk being built on the Dnipro, thinking maybe I’d end up there, but I ended up in Kyiv when I found out the Vyshhorod Hydroelectric Power Plant was being built here. That was 1961, when I got to the Kyiv HPP.

V.V. Ovsienko: It’s the Kyiv HPP, but it’s in Vyshhorod.

V.O. Kondryukov: Not the Vyshhorod—the Kyiv HPP, but it is in Vyshhorod. I worked there as an electrician.

V.V. Ovsienko: And where did you live there—in a dormitory or what?

V.O. Kondryukov: At first, I was put on the brandvakhtas—these are barges; there were probably about 12 of them. They were huge barges with cabins. They housed a thousand or more workers. But I was on the brandvakhta for a very short time. Our Gidrospetsstroy workers brought all-metal trailers, split into two halves with an entryway in the middle. In that entryway stood a burzhuika, I don’t know what it’s called—a small cast-iron stove that was heated with firewood. I moved into this trailer and lived there, probably, until 1964.

V.V. Ovsienko: About three years?

V.O. Kondryukov: Yes. I had even gotten married in 1963 and was still living in the trailer. But it was very cold there in the winter. True, I made an electrical contraption there, I rigged up a homemade heater, because the firewood would burn out, there was no coal, and you’d have to sit and stoke it with firewood all night. So I ran a new cable, because the old one couldn’t handle the voltage, stuck it in the burzhuika, and it hummed all night. At first, the trailers were located right there, near the brandvakhtas, near the summer movie theater and the lake. And then our trailers were moved to Berizky, and there they were half-insulated with sawdust. I forgot that after the brandvakhtas I lived in a dormitory for a while, and then they put me in a trailer when those trailers arrived.

V.V. Ovsienko: What was the community like there, what were the people like, what were their interests?

V.O. Kondryukov: The people were all construction workers; there were no fighters for any cause in those years yet. It was all just beginning to appear, as I understand it. At first, information reached us from Russia, and from Ukraine a little later. Then we switched to Ukrainian. Ukrainian samizdat began to circulate a little later. We started with Solzhenitsyn, “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.”

V.V. Ovsienko: I think that novella came out in 1962. Was it a little book or the journal “Novy Mir”?

V.O. Kondryukov: I think I read it in the journal. Then I got to know one person, then another, then a third. At first, you could say, we didn’t even raise the question of struggle. It was a kind of, so to speak, free-thinking.

V.V. Ovsienko: Were you in the Komsomol or not? Because everyone was signed up back then; I was in it too.

V.O. Kondryukov: I was in the Komsomol, and I was also a member of the CPSU.

V.V. Ovsienko: Really?

V.O. Kondryukov: Yes. I joined in the army.

V.V. Ovsienko: Didn’t someone say, either Nazarenko or Drobakha, that there was even an organization there—the “Party of Honest Communists.” Was there such a thing or not?

V.O. Kondryukov: Nazarenko writes that, but he writes incorrectly that there was a Party of Honest Communists... Even before I met Nazarenko, we had a small group, you could say, of free-thinkers. He’s right that I created it, but it wasn’t called the Party of Honest Communists, but the Party of Real Communism, PRK. We called ourselves that as a joke. There was no party, but a group of four or five like-minded people. We would get together, sometimes have a drink, and start chatting about everything.

V.V. Ovsienko: Criticizing the CPSU, right?

V.O. Kondryukov: Yes. We saw that something was wrong, but we didn’t know how it should be. And then Anatoliy Havryushenko, one of these like-minded people, introduced me to Nazarenko. When I came here, I was, you could say, Russian-speaking.

V.V. Ovsienko: The school you attended was Russian-speaking?

V.O. Kondryukov: The seven-year school was Ukrainian, but the high school was Russian, and the army was Russian. In the village, the language was Ukrainian, well, not pure Ukrainian, they still speak that way there. More accurately, I was Russian-speaking when people spoke to me in Russian. But if someone addressed me in Ukrainian, I would immediately switch to Ukrainian. Nazarenko started speaking to me in Ukrainian, so I started speaking it too, and we hit it off very quickly. And then we met Karpenko, then Drobakha, then Petro Yordan was there, and Vovka Komashkov. We had already gathered a good group. But the most important thing I wanted to say is that our group formed independently of Chornovil, as Serhiyenko told me. Serhiyenko says, “Oh, that was Chornovil who created the group.” No, it wasn’t Chornovil; our group formed on its own. And when Chornovil appeared, some information, samizdat, came from him. We got some things from Kyiv. Information came to us through Komashkov. We got information from Komashkov. That is, he wouldn’t hand it to us directly; he would scatter samizdat on the table along with various newspapers and magazines. We would come, see it, and ask, “And what’s this?” We took it from him ourselves; there was no hand-to-hand transfer. And he later said that he didn’t give it to us, he didn’t distribute it, we took it ourselves—that was our tactic.

V.V. Ovsienko: That was around 1964? When did Chornovil appear there?

O.I. Drobakha: Chornovil appeared around 1961.

V.V. Ovsienko: What was his role there? I think he edited a newspaper?

V.O. Kondryukov: He was the editor of a newspaper, I think.

O.I. Drobakha: No, he was the secretary of the Komsomol organization for the right bank. And he published a wall newspaper. I don’t have exact data on when he appeared there. But he left the HPP—I have this clearly documented—after March 9, 1964, when he gave an incredibly brilliant speech about Shevchenko at the House of Power Engineers—I have that speech. And then they started to get on his case and push to have him removed from the HPP. And about six months later, it seems, he was kicked out of his Komsomol job. They saw it: when there was a competition over Shevchenko between Washington and Moscow, with two states starting to build monuments to him—suddenly in some Vyshhorod there’s such a fiery, patriotic speech. They saw that it was no joke.

V.O. Kondryukov: Maybe he wasn’t there from 1961, but we weren't connected with him. We found out about him much later. Information from him started coming, maybe a year, maybe even a year and a half later.

V.V. Ovsienko: So you organized independently and acted independently.

V.O. Kondryukov: Independently, yes.

V.V. Ovsienko: And did you ever talk about formalizing this group as an organization? Because some testify that there were such thoughts, that an organization should be created, but others said it shouldn't be, because it would only hasten its exposure.

V.O. Kondryukov: There were such thoughts. We gathered at Komashkov's place once, and we had this conversation. Nazarenko might know more, but I also know that we discussed whether to create an organization. We decided not to, because any organization would inevitably be exposed in the future.

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes, and of course, the sentences were harsher for being in an organization.

V.O. Kondryukov: And another thing I wanted to say is that our method of struggle back then was veiled. We supposedly highlighted shortcomings; there was a sort of buffer, we didn't burn our bridges. We argued that we were, so to speak, loyal to the Communists, we were for Soviet power, but we were criticizing shortcomings—that was our cover. But when Chornovil came along—not came, because he was already there—when we got to know Chornovil, he used every meeting, he began to criticize openly, directly. That is, we saw that it was possible to talk about it more boldly and directly. We understood that one method of struggle could be through letters: describe everything fairly and send it to higher authorities, but at the same time, a copy could be sent abroad or circulated among people as samizdat. Then the letters would be distributed and end up abroad. That was also a method of struggle.

V.V. Ovsienko: That was, one might say, educational work.

O.I. Drobakha: This is a very important clarification. This work, which Vasyl is talking about, began in an organized way in 1964. Before that, everything was somewhat spontaneous. Well, Vasyl had known Nazarenko earlier, then Dyriv. When I started making a museum in the basement of the dormitory in 1964, we started to gather and meet there very often. All these conversations happened both at Komashkov’s apartment and at our place. We did it in an organized way, but was it really organized? We decided: no names, no papers—we exist, we see, and we act.

V.V. Ovsienko: What kind of literature was circulating back then? You’ve already mentioned Solzhenitsyn…

V.O. Kondryukov: I won’t recall right now. Drobakha has a copy of—what’s it called? The court case.

V.V. Ovsienko: You have the verdict?

V.O. Kondryukov: Of course.

V.V. Ovsienko: Then I need to copy it, so that it is definitely in the archive of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Ah, is it the indictment? Because the verdict is shorter.

O.I. Drobakha: Vasyl managed to scrape it out, to steal it.

V.V. Ovsienko: And how did you manage that?

V.O. Kondryukov: In the camp, I told Ivan Pokrovsky—you probably know him—that I’d like to have my sentence in my hands. And Pokrovsky, through his people, I don’t know how, brought me this indictment.

V.V. Ovsienko: And why was the indictment in the camp? As a rule, it remains with the court. They put the verdict in the case file that follows the prisoner.

V.O. Kondryukov: But Ivan Pokrovsky brought me this document.

V.V. Ovsienko: Well, I'll be! I need to copy this document. If you let me, I'll make a copy and return it to you.

V.O. Kondryukov: Only on the condition that you return it.

V.V. Ovsienko: Absolutely, absolutely.

V.O. Kondryukov: Let's take a break, I want to have lunch.

V.V. Ovsienko: Alright. [Dictaphone turned off]. This is Mr. Drobakha.

O.I. Drobakha: Guys, Vyacheslav Maksymovych Chornovil arrived in Vyshhorod, according to my research, in May 1963. This is according to a report from one of the party bosses—his last name was Tykhy, from Mariupol.

V.O. Kondryukov: Borys.

O.I. Drobakha: I won't state categorically whether it was Borys Tykhy; the last name is enough. He got a job, or they got him a job, as secretary of the Komsomol organization for the right bank of the Kyiv HPP construction. After some time, Komashkov started communicating with him, and I met Komashkov sometime in November 1964. Chornovil was surprised that during the famous events of September 1965 at the Ukraina cinema, during the screening of the film “White Bird with Black Mark”...

V.V. Ovsienko: Not “White Bird,” but “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.”

O.I. Drobakha: Oh, forgive me, yes, “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.” Vyacheslav asked Komashkov, “Were there really five people from Vyshhorod?” And he says, “Yes, five people. Well, I know these five people, but there might have been more.” This is a separate episode. There’s a debatable point: who was the first to say, “Those who protest, stand up!”—was it Stus or Chornovil?

V.O. Kondryukov: Stus.

V.V. Ovsienko: Were you there too?

V.O. Kondryukov: No.

O.I. Drobakha: I know that Komashkov, Nazarenko, I, and Bohdan Dyriv were there. The three of us were sitting together. Komashkov, as always, tried to stay off to the side so they wouldn't grab him directly. I have replayed this episode many times. It was truly a shocking, impressionistic, or otherworldly thing in our imagination, because Dziuba is speaking calmly, logically, as Dziuba does, and says there are arrests in Kyiv. And just as he said that sentence, the lights suddenly went out, and sirens blared; he couldn't speak. Or maybe the sirens first, and then the lights went out... And then all hell broke loose. And suddenly someone stands up—it seems to me it was Chornovil—and says, “Those who protest, stand up!” Others say it was Stus. But they were together. And so I observe this tension, I'm watching out of the corner of my eye who's standing up. The slaves are standing up. The three of us stood up—Bohdan, Sashko, and I—we stood up and remained standing. Over there, I see, one person is ducking, another is standing up, another is hiding so they won't be seen not standing up, well, our own people there, the audience... And when the lights went out, the screaming and whistling started—it was incredible in the hall.

V.O. Kondryukov: It was intentionally disrupted.

O.I. Drobakha: Yes, of course, but they didn't think that such a commotion would start in the hall after the lights went out. They were also acting half-consciously, more uncontrollably, obviously. I have almost all of this written down, but my diary for two years was stolen from me. They started harassing me in 1965, when one of our secondary people was caught. He was caught with several seditious books. They grabbed him and started shaking him down...

V.V. Ovsienko: Who was it?

O.I. Drobakha: It was Lyakh, but he doesn't figure anywhere. And then they started taking all of us, started interrogating us. Some quietly—a “voronok” [KGB car] drives up and they invite you—me, for example. I didn't have the experience to ask, “Guys, give me some papers, who are you? Maybe you're bandits, why should I get into this ‘voronok’ with you?” I just calmly went and got in, but I should have... And the conversations: who, what, where, how? True, I was a bit experienced. In 1965, it's only recorded that I figured there, but they just talked to us and left us alone, while Vyacheslav was taken.

V.O. Kondryukov: Samizdat reached us both from Kyiv and through Komashkov from Chornovil.

O.I. Drobakha: And from Antonenko-Davydovych, and from others.

V.O. Kondryukov: Yes, yes, there was a lot. Well, and in Kyiv, it happened that someone would slip it under the tables at the university—this samizdat reached us in various ways. At first, we would read it and return it. Sometimes a large piece of material would arrive, and it needed to be read. One person would read it, but the next wouldn't have time. So Nazarenko and I organized a photoreproduction setup. We started together in the trailer, and then in my apartment on Vitryani Hory. Right in the kitchen, we would spread it out, set up lights, secure it, and photograph it, sometimes for almost the whole night. We would do the photoreproduction sometimes together, and sometimes I had to sit all night by myself.

V.V. Ovsienko: Whose camera was it?

V.O. Kondryukov: The camera belonged to Nazarenko. The material had to be returned the next day. And we would return it, after having photographed it. And then I would print the photographs, in several copies, give them to him, and only then would we read. Because otherwise, we simply wouldn't have time to get acquainted with it.

V.V. Ovsienko: But that costs money. Who paid for the photo materials?

O.I. Drobakha: We chipped in, Vasyl.

V.O. Kondryukov: No, with our own money. Sometimes Nazarenko would buy all the developers and fixers, sometimes I would.

O.I. Drobakha: We did chip in a little, Vasyl.

V.O. Kondryukov: Sometimes we did chip in. And when I got a typewriter through Nazarenko, I found a person, her maiden name was Filatova, but she soon married Savchenko… Is there someone like that there?

V.V. Ovsienko: And Larysa Panfilova—was that her? Nazarenko says that a student named Larysa Panfilova did the typing.

V.O. Kondryukov: He's mistaken. She wasn't Panfilova, she was Filatova. Then her last name became Savchenko. I was the one who found her and asked her to type these articles, and she agreed. But I told her, “So there are no suspicions or just in case, you’ll say that you agreed only for the money: ‘I was in a financial bind, and I agreed. I don’t know what was written there; Vasyl asked me, and I typed.’” It seems Nazarenko gave some small amount of money for the typing of his appeal.

V.V. Ovsienko: But Nazarenko said she typed for free.

V.O. Kondryukov: No, not for free, I paid her 20 kopecks per page.

V.V. Ovsienko: Maybe she liked the texts so much that she decided to type them?

V.O. Kondryukov: She said she liked the texts, she was a more or less conscious person, and she was willing to type for free. But I said, “No, not for free, I will pay you—this will be for just in case, it will be your excuse, that, you know, I didn't know, I didn't get into the content, I typed only for the money, because I was asked.” Neither Nazarenko nor Komashkov knew her. We had that kind of arrangement.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what articles were retyped, do you remember?

V.O. Kondryukov: Well, in our case file there’s a whole stack of materials…

V.V. Ovsienko: So, basically, all the samizdat of that time passed through your hands, right?

V.O. Kondryukov: Well, maybe not all of it, but a great deal. There was Djilas... Solzhenitsyn, I think, was no longer there. Mostly, we had Ukrainian literature. There was an article, “Regarding the Trial of Pohruzhalsky”—one of the first. We were charged for it in the case. Nazarenko turned out to have a lot of witnesses. I had only two witnesses.

V.V. Ovsienko: He explained that by saying they confiscated two notebooks from him during the search, and in the notebooks were many names and phone numbers. And they started interrogating all those people, about 25, up to thirty. And, by the way, in Chornovil's “Ukrainian Herald” at that time, there was an article about this case, and the opinion was expressed that, apparently, Nazarenko couldn't hold out, gave in, broke. But in reality, it's all explained by the fact that they confiscated his notebooks.

V.O. Kondryukov: Well, maybe, I don't know if he had notebooks. He probably did. But the thing is, it seems to me, they played on his ambitions: how could it be, you're such a revolutionary, and you've done nothing—did you really not have any acquaintances, did you really not have any people? They played on that a bit too. That's my opinion.

V.V. Ovsienko: So that's how it was! An interesting twist.

We’ve already basically started talking about the investigation, but what was the arrest procedure itself like?

V.O. Kondryukov: In 1965, I was already living in Kyiv on Vitryani Hory. I worked at Gidrospetsstroy. And Gidrospetsstroy managed to get a building of its own built on Vitryani Hory; they were somehow allowed to. I think the raion committee secretary at the time was Marshal, and the head of Gidrospetsstroy got the permission. They built a building, and I managed, with great difficulty, of course, to get an apartment. They tried to evict me there, sent me to Simferopol, said, “Go to Simferopol, our section is there, it will be better for you there.” I said, “I’ve worked here for so many years and don’t have an apartment, and if I go there, who will I be?” Well, they gave me an apartment, and I settled there. We already had our older daughter, Olya, she was born in September 1964, and I got the apartment in 1965. And Zinaida Tarasivna and I got married in 1963. Her maiden name is Matlayeva. It sounds a bit like a Chechen name—Dudayev, Matlayeva. Zinaida Tarasivna Matlayeva, born in 1942. And Olya, our first daughter, was born in 1964 in the trailer. There, in Berizky, where the trailer was already half-covered with sawdust—but it was still cold. We moved into the apartment and lived there.

V.V. Ovsienko: And why did you have such an interest in this kind of literature, why did you want to produce it? After all, it was a risky business, and millions of people didn't do it—why did you do it? Was it something in your soul?

V.O. Kondryukov: Perhaps forbidden fruit is always more valuable.

V.V. Ovsienko: Tastier.

V.O. Kondryukov: And more valuable, and perhaps tastier. Maybe it's from childhood... No, childhood has nothing to do with it. But when I came back from the army, I immediately switched to the Ukrainian language. Many people from our village would come back and speak Russian for a long time, but I switched to Ukrainian right away. Somehow I felt: why should I speak Russian? Maybe it manifested spontaneously then, but it was breaking through in my consciousness: why should I speak Russian or a foreign language when I have my own, my parents' language. And so it gradually, gradually developed. Why did I then hit it off so quickly with Nazarenko when he started speaking to me in Ukrainian? Maybe because of that, because my Ukrainian genes broke through.

V.V. Ovsienko: And the arrests of 1965, did they affect you in any way?

V.O. Kondryukov: I said that Nazarenko got close to people very quickly, so—this is now 100 percent certain—an informant was sent to him. It's visible in the case file... I don't remember his last name now. Nazarenko trusted him, talked with him, and the guy says, “Can you give me something to read?” “I’ll give you something to read.” But he was an informant, either from the KGB, or the Komsomol, or wherever. He read the materials and reported it. And they started watching us, and they watched us almost openly. I was working at the Institute of Superhard Materials for Bakul at the time. Bakul was the director of the Institute of Superhard Materials. So I already noticed that they were watching me. I could get home from work by different routes, even three routes: I could take the tram, I could walk to Vyshhorodska Street, I could go past the Kurenivka bridge, where a car couldn't even pass, walk to Vyshhorodska and take the trolleybus. Even when I was walking near the bridge, where there’s only a pedestrian path, a car would drive towards me and stop next to me. I walked around it and went on. They stopped there, and I walked to Vyshhorodska, got on, and left. I get to Kashtanova Alley, and I look... And this is on the second shift, so I’m returning at night. I look, there’s a car. There are no other cars, but when I get off the trolleybus and cross to Kashtanova Alley—bam, a car flashes by. Then I go up to the turn—again a car flashes by. I see, it seems they’re passing on a signal. And I also noticed from my balcony that near my building at 3 Chyhyrynsky Lane, a car was constantly parked across from the second building. Constantly. I don’t know if it heard our conversations or not, but they were watching my building, constantly watching. And I can tell you who sold us out. True, I don't remember the last name now, but you will find it in the indictment.

O.I. Drobakha: Let's clarify. It was probably Pcholkin, the secretary of the Komsomol organization.

V.O. Kondryukov: I don't know anything about Pcholkin.

O.I. Drobakha: I can say a little. It was 1965. We were slightly acquainted, but you lived in Kyiv, and the events were happening in Vyshhorod, and a storm broke out there. Now, many years later, I have analyzed their system of work. They already had Chornovil, so to speak, on a capital hook; they knew what kind of bird he was. He was arrested in 1966. But they were preparing the arrest, gathering information about him, of course, in Vyshhorod. They were trying to find out who was who, to establish his connections, his influence on us. And I had several conversations. It was like this: a “bobbyk” [KGB car] would arrive—“Oleksandr Ivanovych, we want to talk to you about such-and-such topics.” And I was working in the museum. Well, I come out: “Please.” And off to Rozy Luxemburg Street, to the oblast KGB. Komashkov was quite frank with me, but at that time he didn't say that it was Lyakh who was caught with this seditious literature. Volodymyr Lyakh and a few other people. Komashkov hinted at this to me later. There they were a bit at odds with each other... But for me, what was important was: who were they starting to pull in. And when Volodymyr Lyakh was caught, I don't know what he said, what kind of literature he had, but of course, several witnesses were being prepared against Chornovil. They needed more witnesses. And so I, already a somewhat beaten man, hear in a conversation after three sentences: “Are you acquainted with Chornovil?” I say, “Yes.” But no politics, only poetry, only literature. He had published some of my poems in “Moloda Hvardia,” where he worked. “Yes, he is a very erudite man in poetry.” I kept steering everything towards literature, but no seditious things and no names. They were pushing for what they needed. Later I found out that Komashkov was also being pulled in at this time. Nazarenko, I think, wasn't touched in 1965 because the KGB didn't have any material on him yet. Apparently, Lyakh named some other people who later figured among those 25 witnesses in 1968-69. And Komashkov and I spoke quite openly; at that time, some protest letters were circulating, we signed a few. I don't know if you knew about this or not. That's what I can say.

In 1965, they scared us a little, and even more, they put us on our guard. Knowing Sashko’s talkativeness, I, for example, looked for ways out. I distanced myself a bit from Karpenko, from Nazarenko, because Nazarenko especially... Some women in Vyshhorod told me that Nazarenko is such a revolutionary, such a revolutionary... The women were telling me, you know, what he allows himself to say. I had several serious conversations with him about this ultra-revolutionary character. I said, “Sashko, stop it. These are distant people, complete strangers, they don't rise above the kitchen level, this will be our doom.” He reacted a little, we even quarreled. I went to see Ivan Svitlychny (I had been to his place once before), and I told him, “Mr. Ivan, this is our situation. It seems to me that Sashko, of course, won't listen to me. It would be good to talk to him, because we're going to have a huge problem, as up to fifty people are involved. This will all be prematurely smothered.” Now Nazarenko writes that Ivan Svitlychny suddenly came to Vyshhorod and met with him. He thinks it was out of the blue, but it was because of my conversation.

V.V. Ovsienko: So that's how it was!

> O.I. Drobakha: I told Sashko about it later. But Svitlychny, as a very experienced man, hardly talked about politics with Nazarenko. Apparently, he was assessing the situation—who, what, where, how. It was more psychology than politics. And then Sashko bit his tongue a little about expanding the sphere of his revolutionary activity. But we continued to communicate, although this sedition was no longer circulating as openly and frankly as before. Back then it was just simple.

V.O. Kondryukov: Well, back then there was a bit of a, so to speak, thaw. At that time, they said about samizdat that everyone knew about it—both the KGB and the party leaders—it just wasn't being printed, but you could read it all and nothing would happen to you. That's what the thaw was like.

O.I. Drobakha: Until 1965-66.

V.O. Kondryukov: Yes, yes. And it came in waves: sometimes they clamped down, sometimes they loosened up, sometimes they clamped down, sometimes they loosened up. Right?

O.I. Drobakha: Well, yes. And after all these conversations, things quieted down a bit. After some time, Nazarenko and Karpenko moved to Kyiv, because the circle here was narrowing, narrowing, narrowing, and they saw that they had to get out. I visited them once in Kyiv; they were living in Sviatoshyn. They continued, though to a lesser extent, the same work, with completely new people. That leaflet…

V.V. Ovsienko: That was May 22, 1968.

O.I. Drobakha: Yes. That's when Maria Ovdienko and Nadiya Kyrian took part in its distribution.

V.V. Ovsienko: They printed over 100 copies.

O.I. Drobakha: Yes. Then, apparently, they decided to take them, and that's when they came for you.

V.V. Ovsienko: I have a date written down here: Nazarenko was arrested on June 26.

O.I. Drobakha: And Karpenko.

V.O. Kondryukov: They took me sometime in the summer, but I can't say the exact date. When did your mother come to visit then?

Z.T. Kondryukova: They took you on September 17.

V.O. Kondryukov: No, that was for good. On September 17, they took me and didn't let me go, but about a month before that, they took me and released me the next day.

Z.T. Kondryukova: They kept you. I was there, and my mother was waiting for me there, she said, “Maybe they arrested you too.”

V.O. Kondryukov: Ah, on Rozy Luxemburg Street, right? Well, they let me go the next day then. And a few days later they took me again and released me after a few days. Twice. And then on September 17, they took me and didn't let me go.

O.I. Drobakha: When they had accumulated enough facts.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what did they talk to you about when they detained you those two times?

V.O. Kondryukov: About Pohruzhalsky, how I got it, where and what I was doing, what I was up to. And not just Pohruzhalsky—about all that material, I don't remember it now.

O.I. Drobakha: And the leaflet that they got caught with, was there any talk about it during those first detentions or not?

V.O. Kondryukov: I don't remember.

V.V. Ovsienko: On September 17, when you were detained—was that an arrest with a search?

V.O. Kondryukov: Four men of a good, sturdy build came to my place, or maybe even more...

Z.T. Kondryukova: To your home?

V.O. Kondryukov: Yes. They conducted a search. They did such a search that they even looked in there...

Z.T. Kondryukova: And in the kitchen, and in the cupboards…

V.O. Kondryukov: ...that even the oven—he tore it open to see if anything was hidden between the walls. In all the cupboards, through all the books—they did such a thorough search. They found a photo enlarger on the mezzanine, some film was still left there undeveloped, and maybe some was already printed. They were just lying there. And where was I to hide them? Bury them somewhere? I lived in an apartment, so where would you take them to bury? It was all just lying there on my mezzanine—the photo enlarger, the film. And I don't think I had any photoreproductions. I gave the photoreproduction of Yuriy Klen to Ryma Motruk. She taught at the university. She lived with us for a while, and Hryhoriy Voloshchuk too. Well, Hryhoriy Voloshchuk had been previously convicted, and when he returned, he stayed with us for a bit. As soon as we got the apartment, they came to stay with us. We didn't even have a couch yet, so they slept on the floor, Ryma Motruk and Hryhoriy Voloshchuk. So I managed to give her the photoreproductions of that Yuriy Klen right before the real arrest.

O.I. Drobakha: “Ashes of Empires.”

V.O. Kondryukov: It's an interesting little book. I showed it to her and asked, “Aren't you afraid to take it?” “No,” she said, “I collect this as a philologist, I'm interested in it.” “Well,” I said, “take it.” She still has it. Ryma moved to Tarasivka, not far from Kyiv. Before you reach Boyarka, there is Tarasivka. They found a place to live there.

Z.T. Kondryukova: Maybe they built a co-op?

V.O. Kondryukov: No, I think it was some private house or they bought part of a private house, two rooms on the first floor.

V.V. Ovsienko: How many hours did the search last?

V.O. Kondryukov: About six hours, maybe. The search was very long, and then they called witnesses, who signed.

Z.T. Kondryukova: Why then—the witnesses were called right away.

V.O. Kondryukov: Well, right away. They looked, wrote down all the film rolls: how the roll starts, how it ends. They took the photo enlarger too. I didn't have a camera, but they took the enlarger. And they took me first to Rozy Luxemburg Street, they interrogated me there. And then they took me to 33 Korolenka Street.

V.V. Ovsienko: Did you spend the first night at Korolenka, that is, on Volodymyrska, right? Korolenka and Volodymyrska are the same thing.

V.O. Kondryukov: Sosiura wrote: “I was probably in that house at 33 Korolenka.” And they brought me there too. Here's the pass office, and on the other side is already...

O.I. Drobakha: I was there once for about three hours. They locked the room, I wait an hour—nothing, I wait a second—nothing, I wait a third—nothing. How long can you wait! Silence. This cell is for testing your endurance. And there are apartments there, stairs, carpets... They come and— “For a conversation.” And I tell myself what Stus told me before the trial began: “Look, talk less,”—that stuck in my memory for life.

V.V. Ovsienko: Whatever you say is to your own detriment.

V.O. Kondryukov: And was the room normal?

O.I. Drobakha: No, a tiny cell, a cell like this.

V.O. Kondryukov: And they put me in a normal, you could say, cell, like that bedroom. It's fine for two people, but I was there alone. After the investigator's interrogation, they brought me to the commandant or the head of this isolation ward...

V.V. Ovsienko: Maybe it was Sapozhnikov?

V.O. Kondryukov: I don't know that.

O.I. Drobakha: Who would tell you their last name there?

V.V. Ovsienko: I knew the last name of the head of the investigative isolation ward—Lieutenant Colonel Sapozhnikov.

V.O. Kondryukov: When all this was processed and they started leading me down the corridor, right there (I don't know if it was intentional or accidental), suddenly—they open a door and shove me into a small room. And the room had no light, nothing, it was impossible to even sit down there. It was about fifty by fifty centimeters, so I couldn't sit on the floor. If it got too hard, I would lean on my knees and buttocks. And darkness, complete darkness. I stood there, stood there, stood there, for who knows how long...

V.V. Ovsienko: It's called a “boksik” [box].

V.O. Kondryukov: A boksik, complete darkness. I don't know how long I stood there, probably an hour and a half to two hours. At first, I just stood, and then I started leaning on my knees—it was impossible to sit either way. And then they finally took me out and led me to a normal room, as I said, a bright one. Though, the window was somewhere high up, and barred. True, I asked before that, “What's this trick all about?” They said, “We're preserving the scent or collecting it for analysis.” That was their trick.

O.I. Drobakha: Psychological pressure.

V.O. Kondryukov: It was done to scare me. I understood that. And then after a few days, they put someone in my cell, but I told him almost nothing. I guessed that he was one of their people. They would call him in and ask what I was saying. I told him the same things I told the investigator. So I only had three witnesses. Of course, Filatova... Who else? It's written there, there were two or three witnesses.

O.I. Drobakha: Well, and Nazarenko.

V.O. Kondryukov: Ah, Nazarenko, Karpenko, and Filatova—so, three. As the old song went: “And there were three witnesses—the judge and two assessors.” And I had three, while Nazarenko had twenty-two, I think. No, I don't blame him at all. He knew more people, although I also knew many of the people he knew. But not all of them, he knew far more, of course. I had work, home, family, and he was still single, he would go to Kyiv, meet with many people there.

O.I. Drobakha: About a hundred people were involved with us, who knew about this literature. And 50, or maybe even more, read it. This is serious.

V.O. Kondryukov: Three were imprisoned, about 25 were involved in the case, and of course, many more knew about it.

O.I. Drobakha: Yes, Vyshhorod was buzzing, Vyshhorod was humming. And I was still working at the school, so people started to shun me like the plague. I had to leave the dormitory and move to Topylnia Street.

V.V. Ovsienko: Do you remember your investigator?

V.O. Kondryukov: Koval, I think, Mykola Yanovych, and Berezovsky, it seems. It's written there.

V.V. Ovsienko: Could it be? Berestovsky, Leonid Ivanovych.

V.O. Kondryukov: Either Berestovsky or Berezovsky. A young guy, tall. He was thin back then, but later became stocky.

V.V. Ovsienko: My case in 1973 was also started by Berestovsky, and then he handed me over to another investigator. He handled Ivan Rusyn's case in 1965. So, Berestovsky and Koval. How long did the investigation last, and did it seem difficult to you? How did you feel under investigation?

V.O. Kondryukov: The investigation lasted more than three months, up to four months. But the lawyer, Zayets, whom they gave me, said that they dealt with it very quickly, that such cases are usually handled for a very long time. The lawyer I had requested was not given to me. And how did I request one? The one they planted in my cell with me gave me the name of a lawyer, saying, “You should hire this one.” Well, I thought, I'll say it. And he praised him so much, saying he was so good, that he handles political cases. So I requested that lawyer. I can't recall his name now. But it turned out that that lawyer refused and handed my case over to Zayets. I was sentenced sometime in January 1969, I think.

O.I. Drobakha: No, no, the trial started in December. In December-January.

V.O. Kondryukov: That's what I'm saying, approximately then—in January.

V.V. Ovsienko: How did you psychologically perceive the arrest and investigation? You were about thirty years old then, right?

V.O. Kondryukov: That was in 1968, so 31.

V.V. Ovsienko: You had a wife and child left behind.

V.O. Kondryukov: When I was detained and after the investigator's interrogation they formalized the arrest and took me to the head of the isolation ward, I was a bit shaken. But when they took me to the cell, I somehow calmed down. What can you do, as they say, I was forced to face the facts. And the investigation itself, I'll tell you, was after Beria's methods were condemned, the Beria-era abuses—they didn't beat me, I'm telling you honestly. They didn't beat me, they didn't torture me. But there was various kinds of pressure. Like the example I gave, when they put me in the boksik or something like that. Or they would interrogate me: one in the morning, and another on the second shift at night. To wear me down. Sometimes the second-shift investigator would come, call me in, and interrogate me until about midnight.

V.V. Ovsienko: I take it you resisted, didn't give testimony?

V.O. Kondryukov: Well, I sort of did, I presented myself as “sincere,” but I, so to speak, didn't tell the whole story. They pressured me. I told myself, “When you prove it, then I'll confess,”—that was my tactic, so to speak. And still, they didn't establish a lot of things, there are a lot of lies in there, so if you were to write a history based on that case file, it wouldn't be accurate or objective.

V.V. Ovsienko: Because the investigator has his truth, and you have yours. And each wants to hide their own truth.

V.O. Kondryukov: Yes, to hide some things, maybe even to twist some things.

V.V. Ovsienko: Then tell us about the trial. Where were you tried? Right there, on Volodymyrska, in that triangle on Sofiyska Square, right?

V.O. Kondryukov: Yes, on Sofiyska Square. When they put us in the “voronok” [paddy wagon] and drove us to the trial, I tried to look. There was a small round window with blinds. I kept looking, thinking, where are they taking us? Well, I had a rough idea. But the guard sitting there saw me and closed the blinds completely. But I had somehow either calculated or guessed that I was in that little triangle. Well, what can I say about the trial?

V.V. Ovsienko: Do you remember the judge, who presided?

V.O. Kondryukov: It's probably written down there.

V.V. Ovsienko: The judge's name is not in the indictment; it's in the verdict.

O.I. Drobakha: I think the verdict is one or two pages long.

V.O. Kondryukov: I didn't give you the verdict, but I did type out the indictment for you. I'd have to search for that verdict for a long time. I don't even know where that copy is. Well, at the trial—I don't know what to say about it—we barely resisted. We said what we had said during the pre-trial investigation.

O.I. Drobakha: Did everyone say, “I plead guilty,” or did someone not?

V.O. Kondryukov: No. Everyone said, “Partially.” I also said partially.

V.V. Ovsienko: Meaning, you admitted the fact, but not that it was done with the aim of “undermining and weakening...” right?

V.O. Kondryukov: We were convicted under Article 62, Part One. “Production, storage, distribution of literature and oral agitation with the aim of undermining Soviet power.” All of this was proven. The witnesses were, who was there? Komashkov was a witness... And who else was there?

O.I. Drobakha: Well, there were 25 witnesses.

V.O. Kondryukov: I think the trial didn't last long, three days, it seems. They quickly went through those witnesses...

V.V. Ovsienko: So, Nazarenko got five years, you got three years, and Karpenko got a year and a half. Did you file an appeal?

V.O. Kondryukov: I did, I don't know about the others. I filed an appeal, they upheld the sentence, but they waived the court costs for me. They had charged me a large sum to pay.

V.V. Ovsienko: For what?

V.O. Kondryukov: How should I know?

O.I. Drobakha: For the lawyer…

V.O. Kondryukov: And my wife paid for the lawyer.

V.V. Ovsienko: Maybe for the expert analysis of the texts.

V.O. Kondryukov: I don't know, it was some large sum, but they waived the money, left a little something that I paid off in the camp. But they left the term, three years from start to finish.

V.V. Ovsienko: Did the prosecutor ask for more than the court gave?

V.O. Kondryukov: No, I think the prosecutor asked for that much. I won't assert it now, but it seems that what the prosecutor said, that's how it all went, because all those Zayetses, in the sense of lawyers, were all their appointees. But my first thought was to refuse a lawyer. If that guy who was in the cell with me hadn't dissuaded me. I didn't want a lawyer, but he kept convincing me, convincing me, constantly dripping it into my brain, so I agreed. When the investigator called me in, I said, well, let's have that one—some Jewish name with five letters.

V.V. Ovsienko: Did they give you a list of lawyers to choose from? Because they brought me a list of lawyers who were permitted to handle political cases. You could only choose from among them.

V.O. Kondryukov: No, I didn't have that list. I was adamant about not taking a lawyer, but my cellmate told me, “You're making a mistake, you need to get a lawyer, he's a good one,” he says, “a lawyer, he handles political cases, he wins political cases, just name so-and-so.” And when the investigator called me in about the lawyer, at first I said no, no, but at the last moment I said, “Well, alright, write down that one.” And he wrote it down. But that one refused and assigned the case to this Zayets.

O.I. Drobakha: Imagine if you had refused, Nazarenko had refused, and Karpenko had refused. First, three crooks wouldn't have made money off you, and there would have been a political nuance.

V.O. Kondryukov: Have you read Ivan Hubka?

O.I. Drobakha: I have.

V.O. Kondryukov: As it's written there, when you get arrested and you reach a point where your brain is barely working, you start to think: maybe I'm doing this wrong, maybe I'm acting incorrectly, maybe it's better this way, maybe it's better for me to repent and get out—I'll do more work out there than in here… Do you understand the kind of thoughts that go through your head? True, I've added this part, Hubka didn't say it exactly like that. When you're sitting at home on the couch, you can judge that so-and-so acted incorrectly, that they should have done this or that. That's how we now judge Vyhovsky or someone else.

V.V. Ovsienko: After the trial, there was the appeal. That delayed you for another month or two, and then you were sent to the transit prison in the spring?

V.O. Kondryukov: To the transit prison quickly, about a month or a month and a half to two, I don't remember.

V.V. Ovsienko: Which way did they take you—through Kharkiv, through Kholodna Hora?

V.O. Kondryukov: I said I didn't need anything, but this cellmate says, “Why are you refusing, they'll take you to the North,” he says, “take a padded jacket, take everything.” So I tell my wife, “Well, bring a padded jacket, I know what for.” She brought it. They took us through Kharkiv, and in Kharkiv they stopped our prison car, the “Stolypin,” very far away, so they led us across several tracks, about ten tracks, and the “voronok” was waiting way over there. They led us out together with the criminals. “Everyone link arms!” We linked arms. They surrounded us from the front, on the sides, and from behind, and: “A step to the left or a step to the right will be considered an escape attempt, and I will shoot without warning! Forward, march!” And they led us away. I remember those words exactly. Like that, across probably ten tracks, then they put us in the “voronok” and took us to Kholodna Hora. And they put us in death row cells, in solitary confinement.

V.V. Ovsienko: All the political prisoners who were transported from Kyiv were put in death row cells in Kharkiv. I was there too in 1974.

V.O. Kondryukov: Well, and the cells—you know what they're like, what's in them. Cold. I would lie on my stomach, putting my hands under my chest, and resting my face on my palms.

V.V. Ovsienko: To avoid catching a cold. The bunks there are made of a solid metal sheet. And the stool is similarly welded from a metal sheet, and the table too. And all of it is cemented into the concrete floor.

O.I. Drobakha: Metal, metal everywhere.

V.O. Kondryukov: And it's cold in the winter. And if you lie on your back, you can easily get pneumonia right away.

V.V. Ovsienko: Did they give you some kind of mattress? They gave me one, but it was so thin, the cotton was in clumps.

V.O. Kondryukov: They gave me a mattress, I lifted it like this, and there was a little something in the corner, cotton, I think. I lifted it—and it all crumbled to the bottom. At Kholodna Hora, I don't think they even gave us a mattress. There wasn't one, because I was afraid to lie on my back. And the mattress—that was somewhere else. I don't know, maybe it was already in Ruzayevka.

V.V. Ovsienko: A few days at Kholodna Hora, then on to Ruzayevka, that's already Mordovia, then—Potma. Then, you say, Barashevo, camp ZhKh-385/3.

V.O. Kondryukov: There are two Potmas. They transferred me from one Potma to the other. But I never went to the eleventh c they sent me straight to the hospital. The third camp didn't exist yet then; I was in the hospital, but they quickly fenced off the political zone from the criminal zone and organized that third camp.

V.V. Ovsienko: That's ZhKh-385/3-3 (slash three). Because slash four is the women's camp, and five is the hospital. And one and two were the hospital and the zone for criminal prisoners. And who was there, at least, of the well-known political prisoners? This was the spring of 1969…

V.O. Kondryukov: I have it written down somewhere. If I remember, I can write it down later.

V.V. Ovsienko: What kind of people were there, what categories of prisoners, how many were there in total in the zone? It was a small zone. You probably sewed work gloves there?

V.O. Kondryukov: The work zone and the living zone were separated by a railway track. They would lead us to the work zone, where we were building some RDK or whatever it was called, a station—something like that. We started building all that there. And we lived here in barracks. In total, it was a large zone, maybe a thousand or fifteen hundred prisoners, including the criminals. There were more than ten barracks there, huge barracks. I don't know, I didn't count.

V.V. Ovsienko: But you should have counted. That's all testimony.

V.O. Kondryukov: Well, who thought about that back then... Political prisoners grouped themselves by nationality: Latvians by themselves, Russians by themselves, Latvians by themselves, Estonians by themselves, Ukrainians by themselves. But we had contact with them, and when there was a holiday, we would invite representatives from Estonia, Latvia, and the Russians as well for tea.

V.V. Ovsienko: These were national communities, but I'm asking about the categories. There were those convicted for collaborating with the Germans, a portion of partisans—Ukrainian, Lithuanian, Latvian, Estonian, and a third group—anti-Soviets. These were the three largest groups.

V.O. Kondryukov: There were Ukrainians there who had been imprisoned for thirty years. These were from Western Ukraine. Banderites. Some were involved, some were not. I remember Turyk, Kurchyk. Lukyanenko mentions them. There was Dmytro Hunda. He was still there when I was released. And why thirty years? Because they had served twenty-five, their term was ending, and they would add another twenty-five, and some served thirty, and some even thirty-two years.

V.V. Ovsienko: You mentioned Ivan Pokrovsky, I think. He had 25 years, he was one of the insurgents.

V.O. Kondryukov: He had 25, they didn't add to his sentence. There were also believers. And you know, I even met the burgomaster of Krasnodon, Stetsenko. He was released while I was there, I think. I talked with him, but it was impossible to draw him into a frank conversation there. There was a group of ‘bytoviki.’ They weren't criminals, but ‘bytoviki.’ For example, one served in the army on the border. They put him on guard duty—he left his post and went to Iran or Iraq. They caught him there and returned him here. And he was a political prisoner. Such people would spill the beans about politicals to the oper [operative officer] over tea. And one served in Germany, he was punished for something and locked up for three days in a room on the second floor. He sat there and sat, got tired of it, looked out the window, saw a car standing there, and it was empty. And he was a driver. He jumped out the window, into the car, broke through the barrier... He was there for about three years...

V.V. Ovsienko: This is Mr. Vasyl Kondryukov, cassette two, October 21, 2006. We continue.

V.O. Kondryukov: So the contingent in the camp was varied.

V.V. Ovsienko: Contingent—what a wise word!

V.O. Kondryukov: They were different people. Even among our own, we didn't tell everything openly. So he, this Stetsenko: “Ah,” he says, “there was no real case there. They told me,” he says, “that in some village some boys had stolen cigarettes, robbed a kiosk. I went there and they were arrested,”—this is what he was saying about the Young Guards. “I,” he says, “arrived in a troika of horses, we arrested them, and that's it, I know nothing more about them,” he says.

I never thought I would meet war veterans in the camp, but there were still many of them there. And those who returned from German captivity—all of them were sent here for ten years.

V.V. Ovsienko: And how did the conditions of detention seem to you—hard or bearable?

V.O. Kondryukov: Well, to say that, you have to compare it to something.

V.V. Ovsienko: Ah, yes. You had no other experience.

V.O. Kondryukov: When I arrived, they seemed difficult, but bearable, so to speak. But when Pokrovsky was transferred from the 11th camp here to the third, he said it was much worse here. The 11th was a bit closer to Potma, and we were further.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what was the work? You said there was some construction?

V.O. Kondryukov: There was construction. There was supposed to be some kind of station near the railway, some RDK—I don't know what it was. I was installing a moving crane beam there. The fitters did everything, and I brought the electricity to it, those cables, stretched the cable so the cables could move and extend, a button below so you could control everything from a remote. And we also made concrete posts—pillars. There was a mold, we made the rebar according to a template, twisted it, welded it, and others poured the concrete. And I ran the electricity and did the welding.

V.V. Ovsienko: Was this work outdoors or in a workshop?

V.O. Kondryukov: In a workshop. The workshop wasn't heated. It was a construction site, who heats those.

V.V. Ovsienko: Were there any protest actions at that time?

V.O. Kondryukov: One time, I remember, we declared a hunger strike because a person was shot and killed from a watchtower for crossing the first wire barrier during the day and stepping onto the raked ground. After three days, having achieved nothing, we went back to work.

V.V. Ovsienko: And did many people take part in the hunger strike?

V.O. Kondryukov: No, not many. About ten men. That Mykola, a teacher from Kirovohrad Oblast... I'd have to look through the archives…

V.V. Ovsienko: Bereslavsky, maybe?

V.O. Kondryukov: No, Mykola Bereslavsky was also with us. He was released earlier, he didn't participate in the hunger strike. And the Latvians supported us—Andris Mētra, Gunārs Astra. Astra was killed later. He was the first to find out about the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

V.V. Ovsienko: He was later imprisoned with me in the Urals. A huge guy…

V.O. Kondryukov: Lukyanenko… I met Lukyanenko when Pokrovsky brought me my case file. I let him read it. He read it and said, “Well, would you look at that, in Kyiv, right under their noses, and this thing went so far. It means our cause is not hopeless.” Because there was so much material produced there.

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes, your case was truly grandiose. So much samizdat passed through, so much you produced… I don't know who else did so much.

O.I. Drobakha: Maybe one or two in Ukraine. That's why I use the title “The Vyshhorod Trial.” A book like that should be published. It’s a serious matter.

V.V. Ovsienko: Were you ever in the punishment cells?

V.O. Kondryukov: I didn't have to be. I was so loyal.

V.V. Ovsienko: That was a more or less lenient period—the late 1960s. They started tightening the regime in the early 1970s.

V.O. Kondryukov: No, I simply didn't argue, I silently went to work and did it.

V.V. Ovsienko: Wasn't the warden Major Aleksandrov?

V.O. Kondryukov: I've already forgotten his name. A young, tall, sturdy man. I think it was Aleksandrov. I don't even remember his face.

V.V. Ovsienko: And did anyone come to visit you?

V.O. Kondryukov: They allowed visits. My wife came once. They allowed up to three days, but they gave me one. I said, “What is this! Give me at least two.” They added another one, at my insistence. And then my brother Mykola came, the middle one, born in 1931. He came by himself, he was still in good health.

V.V. Ovsienko: And regarding correspondence—were there any restrictions, confiscations of letters?

V.O. Kondryukov: One letter a month.

V.V. Ovsienko: In the strict-regime camps, it was two letters. It was one in the special-regime camps, but in the strict-regime, you could write two letters a month.

V.O. Kondryukov: I think we wrote one letter a month. And one package every six months, it seems.

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes. And a parcel—that was after half the term, five kilograms, one per year.

V.O. Kondryukov: I always wrote home, “Don't send me anything, I don't need anything.” But I did receive packages. I think I received a package twice. Letters. And then I also... And who sent me a book?

V.V. Ovsienko: Ah, back then you could still receive book packages!

V.O. Kondryukov: Lyolya, Lyolya, I think, Svitlychna sent me Honchar’s “The Cathedral.”

V.V. Ovsienko: “The Cathedral” made it into the camp? Well, I'll be!

O.I. Drobakha: They didn't know, they were fools there.

V.O. Kondryukov: I read it, and then I let everyone read Honchar's “The Cathedral.”

O.I. Drobakha: Was it a hardcover or paperback?

V.O. Kondryukov: No, paperback.

V.V. Ovsienko: A blue one, right?

O.I. Drobakha: The hardcover ones were destroyed.

V.O. Kondryukov: No, Svitlychny himself sent... No, that was another book, so that was the second package. “Malvy” [Mallows] by Roman Ivanychuk. Hardcover, but the spine was cloth, glued. I don't remember who sent it to me. But when I unglued it, there were ten rubles inside.

V.V. Ovsienko: Rubles, you mean?

V.O. Kondryukov: Rubles. So I gave them to Pokrovsky, I said, “Take them, for whatever you want, for tea or something.” A holiday was coming up, so he bought tea.

V.V. Ovsienko: I know that Pokrovsky organized celebrations of holidays there—religious, historical. And they said it was truly beautiful—I still caught those celebrations. They were always well-staged. Despite all the poverty, it was truly a holiday.

V.O. Kondryukov: That's it, I'm saying, a little book, and right here it's bent and glued. And there's another little white leaf here. When I turned it over, lifted the leaf, there was that ten-ruble note.

V.V. Ovsienko: The censor didn't think to look there? Nadiya Svitlychna said she had bought a whole stack of Vasyl Symonenko's “Poetry” books, in the red dust jacket. She bought a whole stack and sent them to the prisoners. Did you receive one from her, or maybe someone else did?

V.O. Kondryukov: No.

V.V. Ovsienko: Well, if you think you've told everything about your imprisonment, then let's talk about the release procedure. Did they release you right in Barashevo or did they bring you back home by transport?

V.O. Kondryukov: They released me exactly on time, probably down to the minute, from start to finish. On the day of my release, they didn't take me out to work, and then they called me to the operative, he checked all my papers, looked over what was there. And what did I have—what was in that backpack of mine? Not even a backpack, a small bag. He looked through everything. Then they led me out. Ah, and I think they told me when the train would be. I went out and waited for the train to Potma.

O.I. Drobakha: Did they give you food for the road?

V.O. Kondryukov: No, we didn't have any food. We could buy goods for five rubles a month. They paid us very little, about 30 rubles. From that, 20 rubles went to the kitchen. They allowed us to buy goods for five rubles, then they deducted for the uniform, and whatever was left, they put in our account. When I got out, I think I had 360 rubles. Did I receive it in cash? I must have, because I was already traveling at my own expense—they just pushed me out and that was it. I paid for the ticket, in Potma too. They said that in Potma a man would be waiting for us to help us get tickets to Moscow. And with that, we parted ways.

V.V. Ovsienko: So you traveled through Moscow. Because, you see, by 1973-1974, they no longer released people directly from the zone to freedom. They would bring them to the oblast center under convoy and release them there. Why? Because when prisoners traveled through Moscow, they would hold press conferences for them with foreign journalists, which was a way for information to get out. And in 1977, they brought me by transport to Zhytomyr and “released” me under administrative supervision.

V.O. Kondryukov: Yes, that was later. We arrived at the station in Potma, we're wandering around, not knowing if the train would be soon. Some man in civilian clothes appeared there, helped us buy tickets.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what clothes were you wearing?

V.O. Kondryukov: The black ones we wore in the camp. The work clothes were dirty, but these were more or less cleaner. I didn't have any civilian clothes. We bought tickets.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what, you weren't traveling alone, was someone else released with you?

V.O. Kondryukov: I was alone from Barashevo, but then at the 11th camp, more people were added, and another woman got on along the way.

V.V. Ovsienko: From other zones.

V.O. Kondryukov: Yes, yes. There were about four or even five of us, another woman was traveling to Moscow. He got us the tickets, we got into one car and went to Moscow. And their “guiding and directing” hand was gone. I arrived in Moscow, I think at Kazansky station, started asking around, because I'd never been there before. To Kyiv, I thought, it must be from Kyivsky station. I asked how to get to Kyivsky station. They showed me the metro, I took the metro to Kyivsky station. There I bought a ticket for a platskart [open-plan sleeping car]. I think the train was going through Kyiv somewhere further abroad, either to Poland or Bulgaria. I said, “I need the next one to Kyiv.” I didn't talk to anyone there. True, I was hungry, I went to the restaurant car, had some borscht. Just once, during the whole trip, I went there, and then I just lay down to sleep and lounged around, whether I wanted to sleep or not, I thought, what else is there to do? So as not to bother anyone, I lay on the top bunk. I got out in Kyiv, it was dark, I don't remember if it was morning or evening. My wife and the Kushnirs—my wife's sister and her husband—met me there.

V.V. Ovsienko: And after your release, were there difficulties finding a job? Were you under administrative supervision after your imprisonment? Did they have any complaints against you?

V.O. Kondryukov: It turned out like this. Before my release, the operative called me in and said, “Where will you go?” I said, “To Kyiv.” “You can't go there. Where do you want to go?” I say, “Nowhere, I'm going to Kyiv.” “No, you can't. Where?” “Well,” I say, “to Boyarka.” “You can't go there either.” “Well, then,” I say, “I don't know any other cities, I'm not going anywhere, because I have a family and an apartment in Kyiv, I'm not going anywhere.” I think the conversation ended there. I came home, not even to Boyarka. There was some supervision over me, but not official.

V.V. Ovsienko: Well, they probably watched all the released prisoners, that's understandable. And did they interfere with you getting a job?

V.O. Kondryukov: Near Vitryani Hory there was the third auto repair plant, such a dirty factory—a horror, I got a job there as an electrician. Probably, if I had tried for some other job, they might not have hired me. But there they think: let him go there, into that slavery. I worked there, and when I found another job, closer, in Podil, at a baby carriage factory, I tried to resign, but they wouldn't let me. I asked, “What's going on? What, am I under official supervision or something?” “Nyet, nelzya” [No, you can't], and that was it.

V.V. Ovsienko: Aha! So you were really in slavery there?

V.O. Kondryukov: “Nelzya.” So I submitted a resignation letter, stating I was leaving due to my departure from Kyiv... Or something like that. Then they signed it. In short, I tricked them. I wrote that I was leaving. They let me go. I worked at the baby carriage factory for several years, then I went to Siberia for work, I arranged it with a brigade. Even there I noticed they were watching me, many years later. And why did I notice? When I had a fight with the brigade leader about something, he said to me, “And why are letters to you still written in Ukrainian?” I asked, “And who gave you the right to read them?” The address was in Russian. “And how do you know it’s in Ukrainian?” It means they were opening and reading them there.

Then I returned to the carriage factory again, and after that, I went to SUPR—Spetsupravleniye Protivoopolznevykh Podzemnykh Rabot [Special Administration for Anti-Landslide Underground Works]. This is far from the metro; this is against landslides. We made adits in the Kyiv hills, where there are quicksands, and then from the adit, with wellpoints, we would push them into the quicksand with jacks every three meters or so, and the water would flow through the wellpoints into the adit, and the sand would settle, and there were no landslides.

From about 1989 or 1990, there was probably no more persecution or surveillance of me.

V.V. Ovsienko: And when did you retire?

V.O. Kondryukov: I retired earlier... There was a law: anyone who worked in a mine—50 years of age and 10 years of underground service. If even a week was missing from the 10 years, that person had to quit their job, go to the Donbas, go back down into the mine to work off that month or two. Otherwise, they wouldn't get this preferential pension. And then somewhere in 1989 or 1990, or 1991, a law was passed on the differential calculation of pensions: however long a person worked underground in a mine, that's how much earlier they would retire. I worked underground for three and a half years, so I retired three and a half years earlier. That was probably in 1994 or 1993. So I started receiving my pension earlier.

V.V. Ovsienko: But those were already times when you probably weren't just sitting by the stove. In the late 80s, early 90s, you were probably active in some way?

V.O. Kondryukov: Well, in those times it was generally impossible to live on a pension. The pension back then started, I think, at 18 karbovantsi, then it went up to thirty, and then more and more. It was impossible to live on a pension then. I was looking for a job. I found a company nearby, organized by some retired colonel or something—“Soyuzservis.” I was an electrician there. One kiosk, a second kiosk near the stores, then at the Livoberezhna metro station. I, as an electrician, serviced all those kiosks. And then we left that job, we didn't like something there. Then I got a job on Voskresenka, there was a company called “Poltava.” I worked there for two months. Then I didn't work for a long time. Then I found a company at 13-E Frunze Street, as a watchman and janitor. They called me an ITR—inzhenerno-tekhnicheskiy rabotnik [engineering and technical worker]. It was some kind of insurance company that insured cars. There were about 16 people in that firm, but not a single worker. There was one owner, a general director, or maybe two generals, and then three regular directors. There was a computer specialist, a chief accountant, some others—all management, no workers there. I was the only worker.

O.I. Drobakha: And he was an engineer.

V.O. Kondryukov: I was called an ITR—engineering and technical worker. I swept the yard there, attached shelves for the computers, the ones that slide out. There was a free cafeteria, I made boxes for them for potatoes, the kind where the boards can be removed, I repaired the floor, screwed in light bulbs, did locksmith work—I did everything, because I was the only worker, and the rest were all management. They were probably laundering some money there, or who knows what was going on. And I worked there for a long time. Then that firm went bust. There was no one there for six months. And I would go there alone, take a look, and leave.

O.I. Drobakha: But they paid you a little bit of money.

V.O. Kondryukov: But the money was very little, 150 hryvnias. Then another firm appeared, which started to do a major renovation there, and it was a four-story building. It was considered two stories, but there was also a semi-basement and one under the roof. A winter palace, a winter garden. They'd work for a month or two—and leave. Probably, the owner didn't have enough money for the repairs. He'd wait a month or two. V.V. Ovsienko: Never mind that, it's not so important. We're interested in whether you showed any civic activism in those years? Were you in any organizations?

V.O. Kondryukov: No.

V.V. Ovsienko: Did you go to rallies?

V.O. Kondryukov: Oh! That I did. I didn't miss any rallies here. But as for active participation in any party, I can say I didn't.

O.I. Drobakha: Well, you were in the URP [Ukrainian Republican Party].

V.V. Ovsienko: And were you in the Association of Political Prisoners?

V.O. Kondryukov: In the Association—yes. I met with Yevhen Pronyuk, of course.

V.V. Ovsienko: Were you at the founding meeting on June 3, 1989? There were about a hundred people there.

V.O. Kondryukov: Yes, I know, it was on Lvivska Square.

V.V. Ovsienko: I was there too.

V.O. Kondryukov: That's our third meeting. The second was in Bykivnia.

V.O. Kondryukov: And a whole column went to Bykivnia, many people went then. I wasn't involved in any structures. I didn't want to be, I distanced myself.

V.V. Ovsienko: And have you written anything about your imprisonment?

V.O. Kondryukov: I have seven or eight articles. But I haven't found them all.

V.V. Ovsienko: We need to make photocopies of them. You found one. If you find the rest, I'll come to you and we'll make photocopies, let them be in the archive of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Has anyone else written about this case? At least there are interviews with Drobakha, Nazarenko... Has anyone else written about the Vyshhorod case?

V.O. Kondryukov: I don't think so.

O.I. Drobakha: Well, what about “Vyshhorod of the Seven Winds”? I mention it there. Vasyl mentioned an interview, but I have several essays, for example, in the book “Vyshhorod of the Seven Winds.” And in this (which?????) book I mention it, but less so.

V.O. Kondryukov: Well, that's what I'm saying, that apart from Drobakha and Nazarenko, no one has written about me.

V.V. Ovsienko: Anatoliy Rusnachenko has nothing about this case, but Heorhiy Kasyanov has mentions. The book is called “Dissenters: The Ukrainian Intelligentsia in the Resistance Movement of the 60s-80s.” It's a good book.

V.O. Kondryukov: I've read it, I know, but I forgot.

V.V. Ovsienko: In it, for example, there is one line: “Ovsienko actively distributed samizdat literature at the university.” And what lies behind that! Carrying samizdat in a briefcase for five years. I really value that line.

V.O. Kondryukov: And is there anything else somewhere about your activities?

V.V. Ovsienko: There is. I've written about it myself. (They laugh).

O.I. Drobakha: No, Vasyl, we are also obliged to write.

V.V. Ovsienko: Now there will be an interview. You will work on it, you will want to add something more. And if it is written, it will be published someday. And what is published, even in a small print run, will not be lost.

V.O. Kondryukov: “Manuscripts don't burn...” as Bulgakov said.

V.V. Ovsienko: I've seen them burn. For example, there in the Urals, when Mart Niklus was sent to prison, a guard named Chertanov, a small, thin man, with only his ears sticking out like a little devil's, was burning Mart Niklus's papers. And they were taking me and Balys Gajauskas out to the yard for a walk. There were manuscripts, newspapers, and colorful magazine illustrations. They burned with such colorful flames, and this Chertanov stirs them with a stick and says, “It's burning beautifully!” Stus's poems, the manuscript collection “Bird of the Soul”—that “Bird” never flew out of there. It's possible that it burned just as “beautifully,” and that was that. Unfortunately, they do burn, and very much so...

V.O. Kondryukov: Yes, I know they burn, I just recalled Bulgakov's expression.

V.V. Ovsienko: Well, we've recorded the main things. If we remember anything else, we'll turn it on again. Thank you.

V.O. Kondryukov: Some things were said hastily, without thinking. It is stated more accurately in the “Memoirs.”

Recorded 10.21.2006. Edited 05.31 – 06.04.2007.

Corrections by V. Kondryukov – 06.19.2007.

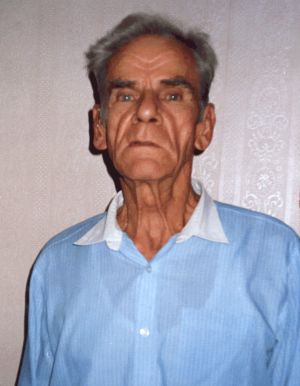

Photo by V. Ovsienko: Vasyl KONDRYUKOV. Film 2358, frame 20. 10.21.2006.

Photo by V. Ovsienko: Oleksandr DROBAKHA, Zinaida Tarasivna KONDRYUKOVA-MATLAYEVA, Vasyl Oleksandrovych KONDRYUKOV. Film 2358, frame 20. 10.21.2006.