LIFE'S JOURNEYS

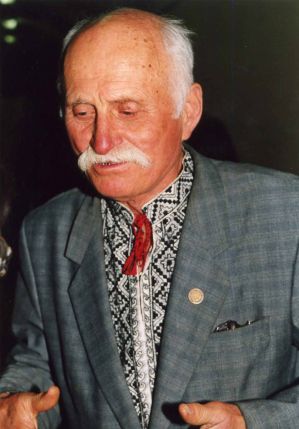

An Interview with Petro Pavlovych ROZUMNYI

December 11 and 13, 1998; April 29 and November 25, 2001.

With corrections by P. Rozumnyi.

Published in the journal “Kryvbas Courier” in 2006, issues 196, 197, and 198.

V. V. Ovsienko: On December 11, 1998, we are speaking with Mr. Petro Rozumnyi at the home of Vasyl Ovsienko—Kyiv, 30 Kikvidze Street, apartment 60.

P. P. Rozumnyi: I, Petro Pavlovych Rozumnyi, 72 years old, was born on March 7, 1926, in the village of Chaplynka, Mahdalynivka Raion, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. That same year I was born, my parents moved as part of a resettlement program to the right bank of the Dnipro, where there was free land that had not been cultivated since the revolution. These were fallow and virgin lands. They moved because here, in the new place, they were given more land, 12 desiatynas per family, and were exempt from taxes for a certain period.

So, my childhood was spent in the newly founded village of Pshenychne. It was founded and so named by the pioneers—the settlers from the left bank of the Dnipro.

My father, Pavlo Petrovych Rozumnyi, was the youngest son in his family, born in 1898. My mother, Fedora Stepanivna Denysenko, was born in 1896. They married in early 1917. As my mother used to say, “The revolution is happening, and we’re getting married.”

I get lost, not knowing what to say or in what order... I will try to continue this story by focusing on my own observations.

CHILDHOOD. THE FAMINE

My childhood was spent in the wide steppe, where as far as the eye could see, there was not a single tree, only burial mounds and blackthorns. The trees that now adorn our area were planted by the pioneers and local residents.

Whenever the question arose as to why my parents had resettled from established places to new land, my mother always said that she hadn't wanted to move, but my father had to, because he feared he might be subjected to reprisals for being a member of an underground organization in 1921-22 called the “Boys in the Willows.” A sheliuga is a type of willow that grew in the Dnipro valleys. I later asked my uncle about it and learned that some teacher from Halychyna had organized several dozen men who offered armed resistance to the expropriations carried out by the Bolsheviks and hid in these willows. They would intercept carts loaded with grain, disarm and chase away the guards, who usually fled, and the grain would be returned. The boys would also scatter and then reassemble, like insurgents. And my father led this kind of double life. My mother, after my father was gone, used to say that she didn’t like that life, that she had threatened to report him to the authorities if he didn’t quit on his own. But he told her: “I’ll come and kill you and your children, and if I don’t, others will come and kill you.” It seems to me that this was the only thing that held my mother back. She often complained about my father, that he was this and that, that he never listened to her. And they already had two children—my older sister, Yelyzaveta, born in 1917, and my younger brother, Ivan, now deceased, born in 1919. So my mother would say: “You have children now, so where are you going and what are you doing? They’ll take you away—and what will I do?” But he never listened to her and, on the contrary, threatened her. My mother didn’t dare report him, and so they lived until 1926. And when the opportunity to resettle came up, they moved, because the authorities were already starting to round up those who had resisted.

My parents settled in at the new place. Although there were six children, in a few years my father became the wealthiest man in the village. He was the first to organize several farmers into an artel, and they acquired equipment, even a threshing machine. With a group of people, he bought a motor with a drive for the thresher. So, by working hard, my father earned a reputation as a farmer who knew how to manage the land. For this, he was later declared a kurkul, because he was the richest man in the village.

I should say that my father came from a prosperous family. My grandfather, Petro Leontiyovych, who died of starvation in 1933, had 50 desiatynas of land and became poorer at the end of the 19th century only because he had to divide this land among his older sons and was left with a small plot. Because that was the custom: to divide the land among the children. Since my father was the youngest son, his father, my grandfather Petro Leontiyovych, lived with him.

When collectivization began—I imagine—some people knew that communization would soon follow, so they sold their equipment cheaply. The men who were organized and who didn't pay attention to what the future might hold, but lived for the day and took care of the present—they simply bought up this equipment for cheap and that's why they had so much of it. These are my conclusions from what I heard later. My mother couldn't explain this to me, and I remember my uncle Denys, my father's brother, couldn't explain this issue either. They said that the threat of communization was always there, it was constantly talked about, but the farmers paid it no mind—they just farmed, worked the land, had their own plans, and tried to carry them out. Those who worked well, lived well, while those who didn't work very diligently just got by on land that was overgrown with weeds, barely able to feed themselves.

I remember my father's reaction when a brigade of Bolsheviks, who were organizing collective farms, came to our yard. My father did not want to join the collective farm. He was one of those who went to hard labor rather than join the kolkhoz. One time—I remember this episode—sometime in early 1932, they came to take the horses. There were four of them—two from our village, and two activists from the village council. The village council secretary had Nagant revolvers tucked into his belt. My father said he would not give up the horses. They asked how was it that he would not give them up? My father said, “Like this!” He took a shovel—and they backed out of the yard. My mother rushed to my father, but he walked around the house with the shovel on his shoulder. And by the time he had walked around, the activists had fled the yard. They didn't come for the horses again.

But soon they came for my father himself. On November 16, 1932, a whole gang of these bandits came to the house, arrested my father, and took him to the village council, and then to a neighboring village. A week later, he was tried on the pretext of failing to meet the grain quota. In reality, he had delivered twice the amount, but he was sentenced to 10 years in prison. They exiled him to the construction of the Moscow-Volga Canal, where he died of exhaustion. According to people from neighboring villages and two from our own village who were also convicted, survived, and returned, my father organized or took part in an escape from that camp. They first fled into the forests somewhere north of Moscow, and then turned south, where they were caught. They were beaten severely along the way. They were brought back to the camp completely exhausted. My father never recovered from that beating and died of exhaustion and—as I gather from what was said—from gangrene, which had developed on his leg as a result of those beatings. So, he died on Maundy Thursday of Easter week in 1933. I calculated it—I believe it was April 10.

We soon found out that our father had died, and there were six of us left. The famine was looming, but we managed to survive because our father had provided for us... There was a total expropriation of grain, of all possessions. They even took my father's bicycle, which was in working order, and another one he had buried disassembled in the garden in a special box. They found that one too and took it. My father had hidden three pits of grain. My mother knew where these hiding places were. It was this grain that saved us during the famine. If not for those three pits, we would have had absolutely no chance of survival, because everything had been taken. They took things so thoroughly that they even swept up the grain droppings in the attic—this grain mixed with all sorts of trash. There was some beans in a pot somewhere—they took it. Wherever there was another handful of something—they swept it up and took it. But my father managed to hide grain in three pits. Two pits were in the yard, and they didn't find them, although they poked around everywhere with iron rods. And one pit was in the field. My mother said he used a very clever method: they would poke along the walls inside each building, but he had stepped back a meter and a half from the wall, dug the pit, and then tamped it down. And they didn't poke in the middle; they couldn't guess that the pit was right under their feet, not hidden under a wall. She said they poked dozens of times, poked all around the building—and didn't find it. It was a small trick that worked. That's how our deceased father helped us survive. It made no difference to him anymore, he was dead, but we had a very hard time.

We had to hide the fact that we were eating. Because the village was dying out, people were dying—but we weren't. This is what the activists were interested in. I remember a group of these bandits coming into our yard, led by a man named Hnat Makarovych Verhun, the first party member in the village. They all stood in a line, called my mother out, and questioned her. This Verhun posed the question like this: “Where’s the bread? Fedora, where’s the bread?” “What bread, uncle? I don’t understand what you’re talking about.” “You’re not lying to me! Where is the bread? Look,”—and we were standing right there—“look: all her children are alive, and no one is dying. That means there’s bread. Where is the bread?” “There is no bread!” my mother answered. “You’ll go to the village council.” They took my mother to the village council. And that's five kilometers away. They kept her there until evening, threatening her, waving a Nagant revolver under her nose. She didn’t confess. And so it passed, they didn't bother her anymore. And they didn't find the bread.

And there was another episode. These bandits conducted an experiment, so to speak, to prove that we were eating something that was keeping us alive. It was obviously grain, hidden somewhere, that my mother didn't want to talk about. One of those activists went to the outhouse and, with a small stick, pulled out excrement in which you could see partially undigested grain. It must not have been ground well enough in the mortar, so it didn't break down in the stomach. He brought it on the stick and presented this visual, material evidence to my mother. They called everyone over: “Look, they’re eating wheat, here, look.” And again they terrorized and interrogated my mother about where the bread was. After that, my mother would hide from them, running off into the bushes when they came, or hiding somewhere in the house. And we would lock the doors. Fortunately, they didn't break the windows, because if they had, they would have found our mother and taken her to the village council again for locking the doors. We would shout that our mother wasn't home and that we wouldn't open up. Well, they would pull out the window panes and shout through the opening, but they didn't break the windows: “Open the door!” But we wouldn't open it. Because my mother had told us not to open it for any reason. We were terribly afraid, but we didn't open it. That's how we survived.

My grandfather didn't live with our family, but with my uncle, that is, his son, Denys Petrovych, who was older than my father. Uncle Denys, having no children of his own, fled from this violence. He left his wife, his father, and his mother (my mother, that is, my grandmother Lukiya, also lived there) and didn't show up for some time. During that time, Grandfather Petro died, and we buried him. I remember the funeral. He died at the age of ninety. He was an elderly man. He had something to eat, they had some food, they had hidden wheat, got it out, and ate it, but because of his old age, he couldn't endure that semi-starved existence. He couldn't take it—he died. There was no one to bury him. His daughter-in-law, my uncle's wife, who was at home, didn't want to bury him. So my mother took it upon herself to bury him, even though we lived in a different house. My mother called us older ones: me and my older brother Mykhailo, born in 1922. We had a handcart with two wheels. We wrapped our grandfather in some rags, also put two shovels on the cart to dig the grave, and wheeled him along the village street. There were no people. No one to turn to. My mother said, “Maybe we can ask someone to help us bury him, because we have to dig a grave.” At the edge of the village, a man was standing at his gate. My mother turned to him: “Uncle, come and help us with the burial.” “I’m not going anywhere—I’m looking that way myself. I’m barely alive as it is.” So we rolled the cart to the cemetery, dug a very shallow little pit, and laid our grandfather's remains in it. We buried him ourselves. It took us half a day because we were all very weak; we were busy with it for half a day, until evening. We barely managed it. That's how we buried our grandfather, who died of starvation. That's an episode from the famine.

In some neighboring villages, there was no cannibalism. But in my village, there was. It was a fact that, so to speak, resonated throughout the entire area: a woman slaughtered her daughter. And this is how it happened. The daughter was born in 1917. Her name was Yelyzaveta. She was a beautiful girl, sixteen years old. She used to walk to Kichkas once a week. Kichkas is what is now Zaporizhzhia. That's what that side of Zaporizhzhia was called then. A dam was being built there. This woman's husband and three sons, who were not much older than us, born around 1910, had all run away from home and were working somewhere on that dam. And they survived by working there, because they were given some small portion, some food, and something extra—a handful of groats or something else. The task of this Yelyzaveta (she was the only daughter, the rest were brothers) was to bring something from her brothers for herself and her mother, so they wouldn't starve. So she would walk to Zaporizhzhia—it's about 45-50 kilometers straight across the fields. She'd get there in a day, and come back in a day. Well, she was gone for a long time, several days. During those few days, her mother went mad from hunger. And when the daughter came back with some provisions, then, as they surmise, she attacked her and hacked her to death with an axe. She cut off her head, threw it into a well, and set about cooking the meat from her body. She put this meat into two cauldrons. As it later became clear, she ate her fill of the boiled meat and died right there. People noticed that she hadn't come out of her house for a long time. The neighbors called, as they say, witnesses, so as not to enter the house alone. They went in—she was dead. They saw that it was human flesh; all the signs were there. They looked into the well—and found the head there. One of those activists, who had previously gone around the village sweeping out the last scraps from every farmer who was dying of hunger, was now also dying of hunger himself, because he was no longer given any of those provisions; there was nothing left to take. The authorities no longer cared for him, he was perishing from hunger, and when he saw this boiled meat, he began to eat it right there, in front of everyone, out of that hunger. Then representatives of the authorities appeared, seized him as an accomplice to the crime, but he died before they could get him to the village council.

This was a man with the surname Kozynka. I even remember when this Kozynka, now a beggar, came to our yard and asked for something to eat. “But you,” my mother said to him, I remember this well, “you were the one taking things from people.” “I did,” he said, “I am guilty, but you see what I’m like now, give me something.” “What can I give you?” my mother said. “I’ll give you a handful of corn kernels—what good will that do you?” “Just give it to me, I’ll smash it with a hammer, cook it, and eat it.” My older sister, Yelyzaveta, appeared out of nowhere—she was already sixteen, and she well remembered who had come and how they had swept and taken everything from the yard, the cow, and everything else. My older sister said, “Don’t give him anything—get out of the yard!” And she pushed him out of the yard by the shoulders, that weak, hungry man. And soon after, he ate a piece of that human flesh and died.

These are the kinds of episodes I remember from the famine. My memory must have been working well because there was this very sharp feeling: what could one eat to keep from starving to death. So, we survived a very difficult time.

V. V. Ovsienko: And what time of year was this?

P. P. Rozumnyi: This was in 1933, starting in the winter and ending... My grandfather died on May 10, the famine was still going on, because in May there’s nothing to eat yet. Although the rye had already put out its ears, the activists would go around catching anyone who took the ears—they would beat the children terribly, whoever gathered the ears. They would beat the children terribly with whips. They were on horseback, like you see in the movies. And they even exiled two families to the Komi ASSR for picking the ears—on that pretext. Because there was a plan: two families had to be exiled from the village. They didn’t know who to grab, and then here you go: one woman cut some ears—they grabbed her with her two children and exiled them. And one man also sent his children to gather ears, and they grabbed him too. He was exiled with his wife and children. So two families were exiled then. Those two families all returned alive from that exile. They ran away from there. They were brought to the Komi ASSR and left somewhere in a wasteland. They wandered, stayed in some villages, someone fed them there, and so they walked, they reached Moscow and walked all the way here. They were walking through a warmer region. The people there were wealthier and gave them a little to eat, because they were small children and a woman.

So, from the winter of 1933, there was such a famine in the village that people began to swell up and die. Until the harvest, I'd say, until June, because in June some vegetation appeared that you could eat. From it, they made what we called motorzhenyky and lipenyky. In other villages, it was called something else. It was a kind of mixture of grass with something else. Maybe a grain here and there. They would mix all this, bake it, and eat it. They ate lamb's quarters, acacia flowers. They are sweet. And other things like that, that you could eat. Those episodes from the famine need to be described. I described a little of it in my biography, as the late Zinoviy Krakivskyi asked, but only briefly. But I didn't describe such details, because it wasn't appropriate for an autobiography.

I would also like to mention how I started going to school during the famine. My father always insisted, and my mother would say: “I will not leave my children illiterate. They will all be literate.” My father didn't achieve this, because they destroyed him, but he did help us, and we all indeed became literate. Four of us six received a higher education. My brother Ivan was an officer in the army, and my sister Yelyzaveta was a nurse. We all studied, we all had a profession—teacher, engineer, so my father's will was fulfilled without him.

I wasn't yet 7 years old when I started going to school. Our teacher was a certain Oles Potapovych Dergachov, a Ukrainized Moskal, I would say. One of those Moskals who were driven to Ukraine by convoy in the 18th century to develop new lands. They were, as they said in our parts, traded for dogs. “Those are the ones they traded for dogs.” Whether this came from literature or from stories, it was passed down: “He’s one of those they traded for dogs.” There was such a contemptuous attitude toward them. Because their part of the village was very different from the Ukrainian part. There, where the katsaps lived, whom they said were traded for dogs—there wasn’t a single fruit tree near the houses, only random trees grew: a maple that had seeded itself somewhere, an acacia—and a bare house. It's almost the same with them to this day. True, most of them have scattered to the cities. But those who remain—still, you might find two fruit trees by their houses—no more. Where Ukrainians live, you can see that they are masters of their homes, they know that children need to eat more than just cherries, so they plant trees. That’s how they differ.

So, my first teacher was from that cohort, and by the way, he is still alive to this day. (This account was recorded on December 11, 1998. — V.O.). He is 94 years old. I interviewed him a few years ago. I was afraid, or rather, I didn't dare to ask him the main question, although he partially answered it for me: does he not regret taking part in the expropriations in the village, helping those bandits go around the village and terrorize people?

How did he do it? He himself did not directly participate, let's say, in poking around the house with an iron rod, searching for those pits where the grain was supposed to be. He had a rifle and would follow this team of bandits. He knew who they were going to, because they didn't go to everyone in a row, but chose those who were alive, who, so to speak, looked like a living person, and that's where they would go, because there had to be bread there, otherwise he would have already died. That was the main sign: if all the children are alive, then you have to go and search there, because they have bread. So this Oles Potapovych Dergachov with his rifle would always stay about a hundred meters from the house where they were searching for grain, and there he would pretend to look up at the sky, at a crow flying by, and from time to time he would shoot: bang, bang. And with this he reminded them that they weren't going to stand on ceremony here—they would shoot those who didn't give up their bread. That was his method. So, if these bandits, this gang of grain seekers, were at work, Dergachov would accompany them from a distance, shooting into the air, or if he came across a dog—he would kill the dog. He killed our dog, by the way, in our yard. The famine was already on, and my mother put it to use: we ate that dog.

What other unconventional things did we eat—I didn't say why we survived: in early spring, on St. Yevdokha's day, the first gopher comes out of its burrow. My older brother Mykhailo was a good hunter of them. We would catch them and eat them. They are very tasty, I recall. I think you could still eat them today. They are animals that eat grass, grain. Completely clean, beautiful animals, rodents. And we ate them. It was a big event—when a gopher was caught, my mother would cook a whole cauldron of soup or borsch, which we ate with great benefit, because it was meat. That was one of the things that allowed us to survive. My older brother caught the gophers, and I was just the courier. He'd catch one—and I'd run home to bring it. My brother was a lucky hunter. He managed to catch them almost every day. It was hard to find the burrow where they lived or where they came out. That was the most important thing—to find it, and if he found it, he would hunt for three days, but he would catch it. The method was to flood them out, but it was hard to carry the water. People flooded them out later too, when it was no longer necessary to eat them.

SCHOOLING

So, I wanted to say how our teacher, Oles Potapovych Dergachov, taught us. These were the first lessons in how to behave under Soviet rule, what kind of citizens should be raised under Soviet rule. The school was in the house of an uncle who had been driven out and had gone somewhere to Kichkas (Zaporizhzhia). The first question was: “Children, who knows, who has heard any of your parents, father or mother, brother or sister, say anything against the Soviet authorities?” No one ever answered this question, because it was not clear what "against the Soviet authorities" meant. But he asked it every time. True, he never explained this question to the children with examples, but he always asked it. I now think he was obligated to ask this question. It was always the same, and no one ever answered it.

But the second question he asked was: “Who has seen, or maybe heard, any of your parents hiding bread?” Silence. Well, bread meant grain: wheat or barley, or something else. A boy named Myshko Mostovyi raised his hand—he later died of starvation, all five children died, and their father died too. “I haven't seen bread,” he says, “but I saw my parents hiding grain.” He told where. Then our teacher, Oles Potapovych Dergachov, latches us in: “Sit and read!” And he went to where the grain was hidden. Obviously, they called someone from the village council. An hour or two later, we see a cart coming, with some sacks on it. It means they found the grain. And they are leading the man behind the cart. The man is walking, escorted by two orderlies from the village council.

These were our daily exercises in "who saw what." Another time, the same Myshko told how his neighbor across the road, with the surname Llianyi (or Lnyanyi), was hiding a plow in a haystack in his garden. This was equivalent to grain—the plow had to be handed over to the collective farm. You don’t join the kolkhoz yourself—but hand over the plow! But he didn't hand it over, he hid it. Then our Oles Potapovych Dergachov also locked us in and went to the village council. The plow is being carried on a cart, and Llianyi is being led away. He walks behind the cart, followed by armed guards.

So Pavel Morozovs were being born everywhere.

In my interview, I asked Oles Potapovych: “Why did you take part in this? You could have refused.” “I couldn’t have refused.” “Why? Others didn't participate, did they?” I named some who didn't take part in all that, even though everything had been taken from them. “Well,” he says, “if I hadn’t participated, they would have taken me too.” That was his argument. “Well,” I said, “whether they would have taken you or not, you contributed to those people dying of starvation.” “Well, that was the time,” and he throws up his hands. “Because, I repeat, if I hadn’t participated in these campaigns around the village, they would have taken me. They would have destroyed me, because my father was declared a kurkul.”

But I didn't dare ask the main thing, because his daughter came in, and she was a big activist. She's a bit younger than me. She was in the raikom, or what was it called?

V. V. Ovsienko: Raikom or raivykonom.

P. P. Rozumnyi: Raikom—that's the district party committee. But there were non-staff activists, about ten people. That daughter came in, gave me a sidelong glance—because she knew about my sentiments. I didn't want to ask in front of her, because she might have pounced on me, she's sort of unbalanced. So I didn't ask the main question: does he not regret that he deprived people of their material means and that half the village starved to death? I didn't ask that. If I live and if he is still alive, I will go and ask him. I have to ask, because it is important to me.

That's a brief account of my studies in the younger grades.

We were transferred to a school in a neighboring village, and for the first time I saw that more people had died in the neighboring village than in ours. The neighboring village is called Krute—it's an old village, not a resettlement one, but an indigenous one. There I saw houses where people had died out completely or had been evicted.

It seems our village was lucky that only one family of katsaps was sent to us. They were called nothing else, only katsaps. Not Russians, not Moskals, but katsaps. The houses that were emptied of people who had died, fled the village, or were evicted, were settled by katsaps. Only one katsap family appeared in our village. But in the neighboring village of Krute, where I went to school in the 3rd and 4th grades—half the village was overrun with katsaps. I saw them for the first time. They were sort of lanky, in bast shoes, in some kind of terrible, pathetic gray coats. And most importantly—they all cursed loudly. It was the first time I heard these obscene words coming from people's mouths as if they were some kind of blessing. Because, I remember, in our village, before saying an obscene word, the men would look around to see if there were any children or women nearby. And only then would this curse be squeezed out, and in such a quiet voice. And here, I suddenly heard that a curse was something like “good day,” that is, a common word. We would stare at them and examine them up close, as if they were an unknown people, some unknown tribe that shouted a lot, cursed, and bustled about. Because, I remember, they were busy sawing trees, even black poplars that grew in the old villages, lengthwise into planks. They made some special devices, sawed, and constantly and always cursed terribly loudly. Their enterprise was in the schoolyard, so we heard all this during recess, and before and after school. It was quite interesting to see these newly arrived people.

In the following years, in the fifth and other grades, I walked to school in yet another village, even farther away.

V. V. Ovsienko: What is it called?

P. P. Rozumnyi: The village of Bezborodkove. I walked there until I finished school. A daily walk of 5 kilometers there, 5 kilometers back. It was a tough business. We were often half-starved, but we endured it because we wanted to study. I remember that the main thing I learned in school was from reading all the books in the school library. And there were, as I later assessed, looking at post-war libraries, quite a lot of good books. I remember reading Mayne Reid in Ukrainian, Jules Verne and Dickens in Ukrainian I read, though I understood little of it, only the plot. I remember reading Walter Scott in Ukrainian. These books, translated from English, from French, completely disappeared after the war. I no longer saw them in libraries.

I was an average student, so-so, but not the worst, I would say, I got fours. Back then, a four was marked with the word “good.” I think I was a solid B student. At that time, report cards had a column for “special aptitude for certain subjects.” The teachers always wrote for me: “For the Ukrainian language.” Obviously, I was simply well-read. The teachers knew this, and maybe it showed in my speech. I don't remember knowing grammar well. I also remember that when I entered the institute, I quickly familiarized myself with Ukrainian grammar, and it wasn't difficult for me. I revived that knowledge.

V. V. Ovsienko: When did you finish school?

P. P. Rozumnyi: I would say this: I left school in 1941.

V. V. Ovsienko: And how many grades did you complete?

P. P. Rozumnyi: I didn't finish the 9th grade.

V. V. Ovsienko: Why?

P. P. Rozumnyi: Because I quit. I'll put it this way: we had reached such poverty that my work was needed to help out at home—well, there was nothing to wear on my feet, nothing to put on. My older brother somehow finished school with great difficulty, with great hardship—a pedagogical technical school. He was assigned to a job somewhere in the Mahdalynivka Raion, to do something in the district education department. But he didn't go. I now understand why he didn't go. I would say that he was, in the full sense of the word, without pants. Absolutely ragged and tattered. He had nothing to appear in public in. So he conspired with one of his fellow students, with whom he had gone to school, and they ran away somewhere to the Caucasus.

V. V. Ovsienko: What is your brother's name?

P. P. Rozumnyi: Mykhailo. He is deceased now. They ran away to the Caucasus. Just like the homeless run away now. They saw that at home they would have to give up everything and work on the collective farm. He didn't want that. That's what he said later. But you have to live somehow. They set off—someone told them that life was easy in the Caucasus. They wandered somewhere, worked odd jobs. They picked citrus fruits, as he later told me. The war found him in the North Caucasus. And the Germans had already come here. And from the North Caucasus, in the fall of 1942, he walked all the way home. And I was already in Germany by that time.

So, I left school in 1941. Poverty had simply worn me down to the point where I had no strength to hold on. To go to school and eat nothing or... pants down to my knees, nothing to put on my shoulders, because my mother alone couldn't provide us with all that. We lived off the garden. They paid then 300 grams of grain per workday—if they paid. My mother didn't even earn one workday a day, like those who had permanent jobs did. And people like her earned what was called “50 hundredths,” half a workday, and 70 hundredths was already a lot. I immediately went to work with the calves. I looked after the calves with an older woman. That is, I mostly helped. Right away, I started earning workdays, they began to give some grain for the workdays. I'd bring home five kilograms of grain, we'd pound it, and eat kasha. The younger ones—my brother Stepan (born in 1928, later became a railway engineer), my sister Kateryna (born in 1930, later became a doctor)—went to school, but I quit. Somehow I guessed right to quit, because the war started in 1941, so no one went to school then. Under the Germans, the school was reopened for one month, but then it was disbanded and didn't operate during the war.

So I had already become the breadwinner in the family. This was a huge relief, because I was earning for myself and a little for my brothers and sisters, and my mother was earning for herself, so we could somehow get by. It became easier. I wanted to go to a trade school, because they were being created then. They wouldn't let me go, because they only let those who hadn't studied at all, and I was a B-student. The director wouldn't let students like me go. This happened later too, even after the war, that if you studied well, they wouldn't let you go anywhere. But if you studied poorly—go ahead to the trade school! They wouldn't let me go. I was disappointed by that, and it was one of the reasons I quit school. I would say that my mother encouraged it, and I didn't object.

THE WAR

My intuition didn't fail me, because that school ended two months later, and the war began during the summer break.

V. V. Ovsienko: When did the Germans arrive in your area?

P. P. Rozumnyi: They came to us in August. When the war started, I was already a full-fledged worker in the family. I was bringing income to the house, although there was no money—only workdays. But I had already quickly adapted to what the collective farmers had adapted to: stealing. If I could steal—I stole this, that, or the other. In short, I was learning to live by Soviet laws. I saw the older ones stealing—and I did it with them.

I gathered a gang of boys, and we went into the windbreak to play war. We see a horseman galloping toward us through the wheat, across the field. The horse was already tired, it seemed, galloping reluctantly from the neighboring village, straight across the wheat, not on the road. He galloped up to us. We were on the road at the edge of the village. Without catching his breath, he said: “The war has started. War with the Germans. The German has attacked.” And he rode on to the office to tell them. And we followed him. I told the boys: “That can’t be—we have a non-aggression pact with the Germans.” I was already reading newspapers. A neighbor of ours subscribed and let me read them, and we would philosophize: who was being bombed, where the bombs were falling, about London—the war was already going on there. In 1939, Poland was conquered. The war was already on. They reported on who was bombing whom. “That's not true,” I said to myself. I was such a philosopher then and was already into politics. “It can’t be, because there was a non-aggression pact.” They had praised that pact so much, there were drawings in every newspaper, handshakes: Molotov, Ribbentrop signed, friendship, treaty—all that. There was friendship. There was a non-aggression pact. And I didn't believe it at first, but when the horseman told the men who were hanging around somewhere, cracking sunflower seeds near the workshop, because it was a Sunday, I started to believe. Because the men started talking about it among themselves with concern: “The war has started. The war has started.”

Well, the war began. They are preparing for evacuation. First, the cattle. They send my uncle Denys to drive the cattle to the other side of the Dnipro—that's about thirty kilometers from us. A ferry crossing had been set up there, they would drive the cattle onto the ferry and transport them across. And they drove them there on foot. My uncle said he drove the cattle as far as Luhansk, and then the Germans caught up. He fled from the cattle and returned. He abandoned them because the Germans "covered" them there.

Meanwhile, the kolkhoz chairman, who was from a neighboring village, sends an orderly to me to take him, the chairman, home in a “bidarka.” It's called a “bidarka,” a two-wheeled cart. I took him home, because it was already late. I was so obedient. Whatever they said—I would do it. I was a reliable worker, I did everything I was told diligently. I remember as soon as the orderly arrived, I threw on my clothes, took a whip, and arrived almost at the same time as the orderly. The kolkhoz chairman praised me: “With people like this, we’ll crush Hitler!” That poor kolkhoz chairman went into evacuation with his family. He harnessed a pair of good horses, equipped the best cart, but when he drove onto the Zaporizhzhia dam, at that very moment they blew it up, and he disappeared somewhere in the Dnipro. Some survived, because they only blew up a part of the bridge—the machine section, and that’s exactly where he perished. His name was Hamzyn, the kolkhoz chairman. So he died without a war, without the Germans—at the hands of his own people.

There was an episode, after the Germans arrived. Our people had driven off the cattle, for us it was unnoticeable—they drove them off and that was it. But when they started driving cattle en masse from other regions, you can't imagine it, it's hard to describe! It was a solid, uninterrupted stream of cows, horses, and sheep, with no gaps between the herds. And they drove pigs too. The pigs quickly got tired, so they would drive them into a ravine somewhere, where they could drink water, and they would lie there. People stole them. And I was one of them, stealing while they were lying there. Then we started eating meat, because it was grazing around our village. This was a continuous stream of livestock that moved at a slow pace, on and on and on.

Just before this stream, when it wasn't yet so massive, they sent me and one of the men with the reserve horses. There was such a reserve in every collective farm, a dozen or more horses that were fed for the army; they were not allowed to be harnessed. These were real horses, beautiful. We broke them in, taught them not to be afraid of the collar, but they couldn't be used for any work. And suddenly they decided to take them to Verkhniodniprovsk—there is such a town on the Dnipro—and hand them over to the army, because they were designated for the army. We harnessed a pair of horses to a harba, and a harba is a long, ladder-frame wagon for straw, you know. And our harbas were so large, I've never seen such wagons anywhere else. You don't have such wagons in your Polissia. They travel easily. They are used to transport straw and sheaves—they load them full, and then two racks are raised, and the harba is three meters high. A pair of horses pulls it. So, to this harba we tied ten horses all around. Well, I was the assistant, and Uncle Luka Yurchenko wasn't afraid of horses, he rode those reserve horses. We arrived in the raion center, Solone. They direct us to Verkhniodniprovsk. At the kolkhoz, they didn't tell us where to go next. In Solone, they gave us each a loaf of bread, beautiful round loaves, and half a kilogram of melted butter—so they gave us rations as if we were already mobilized.

In a day, we arrive in Verkhniodniprovsk. The hitching posts are already ready, we tied up the horses, fed them, watered them—that was our job. The next day, they even sent us a concert—artists danced and sang. And these were horses from the entire district. I had never seen so many horses in my life, there were hundreds and hundreds. And all the horses were the best—reserve horses, they were specially fed, they were not harnessed, only for the army.

And here is an episode. The hitching posts were like this—a hundred meters, a hundred meters, a hundred meters. A colonel with "sleepers" [insignia], as I remember, a lean man, with a retinue of officers, some civilians walking around, inspecting the horses. There were veterinarians with them, looking at their teeth—the horse is free, and they are still looking at its teeth! This episode is interesting because there were two speeches by this colonel to us, because in one day he couldn't inspect all the horses, evaluate their teeth, legs, and everything else. But on the first day, he inspected a few, looked at the horses, and then gathered us together and told us: “We will crush the German! We will definitely crush him, because we have applied a tactic: we are letting the Germans in, then we will surround and annihilate them. In this way, the front has advanced a little this way, so to speak, to this side of the Soviet border, but that is because we are letting them in to destroy them later. In this way, we will annihilate them.” Some of the men, who believed this fairy tale, said: “Oh, they are doing it smartly—letting them in, and then surrounding and destroying them!” My uncle was not so naive. He was silent, he just waved his hand like this. And the front was still far away—the German was nowhere near. And I remember, planes were flying right above the ground, in a low-level flight, they didn't go up high, because up high the Germans could already see them, but down low they could somehow still hide behind the landscape, they were not visible.

But on the second day, after the colonel had inspected the horses, he said this: “These horses that you have brought me here for inspection are worthless, they’re no good for anything. These aren’t horses, they’re nags. Take them away, lead them home, feed them so that they are fit to serve in the army, and so that with their help we can crush the Germans who have treacherously attacked!”

And we, this crowd of people with hundreds of horses, tie them to the harbas and head back. And when we were driving back, we couldn't go on the road, because the whole road was filled with livestock, including sheep, and so as not to injure their legs, everything moved slowly—horses, cows, and sheep. We had to leave the road and drive more than a hundred meters away from it to avoid getting into this solid stream of livestock. We drove through the fields for a long time. We twisted and turned... We arrived home, the next day I rested, didn't go to work, because I had returned from a trip, and they didn't call for me. My younger brother Stepan and I are watching—planes are flying from the southwest. They fly slowly, buzzing like autumn flies, and they look something like our U-2s, biplanes, with two wings, clumsy. We started arguing about whose planes they were, because in the newspapers (and I read the newspapers and showed my younger brother) there were drawings of planes—German, Romanian—what they looked like. My brother remembered that such biplanes were Romanian. But I didn't remember. He says they are Romanian, and I say no, they are Soviet planes, the Germans didn't have that type of aircraft. While we were arguing, we suddenly heard a whistle—a whistle, bombs are falling on the road where the livestock is moving. And the evacuated people, who for some reason were fleeing through our village from Vinnytsia Oblast, from Moldavia, from Mykolaiv Oblast. These six planes decided to bomb this whole solid stream of livestock and people. And not a single bomb fell on the village—somehow they all fell across the road and at a sharp angle. As we traced, three bombs fell on the road, and the rest fell in a field where sorghum was growing. Each plane dropped only one bomb—that was their procedure.

From that day on, the movement of livestock and evacuees stopped, there was no one on the road. The livestock stopped moving altogether, scattered, and those who wanted to flee further no longer dared to travel on the road, but only through the fields and at night, and during the day they sat somewhere under the trees, hiding in the groves. And German planes flew, although they didn't touch us, they were conducting surveillance.

There was an episode of looting on my part, to use today's language. Someone said that somewhere in a ravine, sheep were grazing, abandoned by their shepherds. The three of us went—me, my younger brother, and another one—to look at those sheep, to see how they were doing. We each caught one and dragged them straight across the fields. We had dragged them quite a distance, we were approaching the village, when we heard some rustling. We looked around—a plane was flying straight at us. It was descending on us, you could already see its frame, through which it aimed, its long landing gear wheels. It was a reconnaissance plane, as I later identified it, it was called a “frame” in the newspapers. And it was flying straight at us. We froze, pressed ourselves to the ground, and it flew, well, maybe a hundred meters above the ground. We didn't even have time to get scared before it turned, flew up, and went away. And we didn't abandon the sheep. That is, it saw there was nothing worth shooting at, and didn't shoot. They say the Germans shot at everything they came across—but it wasn't worth shooting at this, because he saw three sheep and some boys. He came down so low to get a good look. That was an episode of looting.

We ate our fill of meat and bread, because the harvest was already gathered, there were no more Soviet procurements, and before the Germans came, we took as much bread as we needed—as much as anyone wanted, they took. There was so much wheat gathered on the threshing floors that it hadn't all been taken. They took it in moderation, or I don't know by what criteria—whether by earnings, or what. People stopped taking it. And when the Germans came, they put a seizure on that grain, but that was no longer a problem for anyone, because everyone had as much grain as they needed in their homes.

I would also like to tell an episode I hinted at earlier. It may not be a very good one. How I became a Ukrainian, how it all began. I remember on Sundays, members of my father's association would gather at his house with their wives. There would be 8-10 of them, and all ten of them would drink a bottle of horilka together, no more—they would drink one bottle of horilka. They were very cheerful, they sang and grumbled about the grain being taken, about everything being taken, because Ukraine was always... I remember one of them constantly quoted: "Ukraine the bread-basket, gave its bread to the German, and is hungry herself." They always talked on this topic, and it stuck in my head that Ukraine produces bread, and the German takes it. Which German, where were the Germans? But when the Germans were coming, I thought that it must be those Germans who were coming now.

For some reason, we went into the field one day—the men, I think, decided to see how the wheat was harvested or how the sheaves were lying. There were a lot of sheaves then. They had threshed a little, but the rest was unthreshed, but in stacks. And they collected leaflets. One, the most literate one, while everyone else was collecting, began to read aloud: “Ukrainians, residents of Kryvyi Rih! The defeated Bolsheviks, fleeing in panic, are destroying the fruits of your labor.” I have reconstructed this exactly or almost exactly, I had it written down somewhere. “Do not let them do this to them!” And they explained how not to let them: “Kill them, drive them away, remember that you are to remain on this land, you need to live on this land and enjoy its fruits. And without this, you will die a hungry death. Do not let them drive away the cattle, burn the grain,” etc. This is what struck me the most: “Ukrainians, residents of Kryvyi Rih!” I looked around at these Ukrainians—it only made such an impression on me, on no one else. From that time on, I remember that we are Ukrainians, even though we are not residents of Kryvyi Rih, but something separate. Like that.

But then the Germans occupied Dnipropetrovsk and came to our village to rest. The village was full of vehicles. And our village had many trees—trees by every yard, and a windbreak around the village. You could hide in our village—it was the only way to camouflage from planes. A whole division could probably have hidden there. There were about 150 vehicles in the village. There were vehicles, but no heavy weaponry, only submachine guns, machine guns on some vehicles, but no cannons or other equipment, and I didn't see any shells.

So these resting Germans—this also struck me—every morning and every evening they gather in the village square and they are praying. Their chaplain, as I now know, says something or reads to them, then they get down on one knee, stand there for a while, and get up. It was interesting for us to watch. So we knew: the Germans pray twice a day.

I already had some notion of this, because I remember my mother and father taking me to have the Easter bread blessed. This was in a neighboring village, there was a parish there. We had a priest from a neighboring village, and his wife, the popadia, was my godmother. So my father was a believer. This priest, by the way, was killed by activists, and his wife, the popadia, that is, my godmother, was also killed, and they even mocked their corpses: they arranged them in an obscene pose. And they killed them like this. We had a village council head named Petukhova, a katsapka from those who had once resettled from Belarus. They were called “Lytvyns,” they spoke a language like Belarusians do, some sort of half-katsap language. Obviously, they were Belarusians, but I still haven't figured this out to this day. They are called Lytvyns, and the village is called Sursko-Lytovske. But they spoke and still speak Russian. This Petukhova was always drunk, a pistol tied to her leather jacket, she cursed obscenely, would hit men with the handle of her Nagant when something displeased her. She was a real bandit. So she summoned the priest and put the question to him in such a way that he should stop celebrating the Divine Liturgy. They say the priest refused, said he would serve God, and that the law allowed him to celebrate the Divine Liturgy, and no one could forbid it. “I’ll do you in, priest!” she said, and her words were later quoted. Indeed, that evening three men came, killed the priest and his wife, desecrated their bodies—and that was it, after that no one looked for anyone. They knew who did it. Two of them quickly committed suicide. One drank himself to death—drank so much he burned out, and the other hanged himself. And the third, with the surname Lypka, was still a police chief somewhere on the left bank in some district even after the war—this can be verified, because it's known. His surname was Lypka. He earned the rank of police chief for such feats. And the priest was killed by these terrorists even before the war.

I think I started talking about the war. So the Germans came to rest, and it was interesting for us to watch them. One time a German calls me: “Komm! Komm!” He pulls out a small dictionary and reads: “Zoloma.” I can't figure it out, but another German comes up to him: “Soloma.” Straw. Where is the straw? So I show him where. We went, I showed him where the straw was. We had an unfinished club—only the clay walls, and that was it. They spread straw there and slept there. They didn't stay in the houses, but all slept on the straw—it was warm, there was no rain.

Then there was another episode. They went to pray, and we went to rummage through their parked vehicles. I found a long, straight saber—not a Cossack one, but a Budyonny-style one. I took it, we were a whole gang, and we took turns chopping at trees. A man met us, scolded us, and told us to put it back immediately, or the Germans would shoot us all. I didn't put it anywhere, but brought it up to my attic, and I don't even know what happened to that saber. I didn't look for it then, and the Germans didn't look for it either.

And another time, I remember, the Germans were trading—they didn't take anything from us, but they traded eggs for lighters, for flints for lighters. So we had to bring a certain number of eggs. If you wanted a lighter, you had to bring eggs. We brought them eggs, and traded.

The kolkhoz was still there, there was a small pig farm. I remember the first thing they slaughtered and brought to the kitchen was a boar. Not a castrated pig, but a boar they killed, and it went to the kitchen. Even the men were surprised and laughed at how they ate boar, because the men would never eat it, a boar doesn't have tasty meat, it has some kind of smell. So the Germans took from the kolkhoz, but not from the men—there was no such thing as someone taking something from someone. They say there were some Germans in the neighboring villages who caught chickens, they didn't want anything but chickens. But in our village, the Germans didn't do that.

The main mass of Germans left the village, not many remained. There was a repair workshop in the village, about twenty Germans, who, obviously, maintained communications, laying wire directly on the ground between villages. This was for telephone communication. They repaired machine guns in our village. There was a place there with an earthen mound, and they would shoot into that mound. They would draw some line there and shoot along that line. And we would gape and run around them to see how it was done, and every day they would offer us: go on, you shoot—you shoot, you shoot. Anyone who wanted to could shoot. Pressing the trigger and—r-r-r-r—it was so interesting to shoot a machine gun! They were so friendly—no one did them any harm, no one tore up those communication lines, and I don't remember any repressions on the part of the Germans.

A commandant's office was set up in the neighboring village, where the village council was, so we were obligated to send a person on duty there from each village. And they sent me, because I was the most obedient and sometimes the wisest. I was there every week with that commandant. He would send me with packages. I would take a package under my shirt and ride a horse on a makeshift saddle with stirrups to carry out this task. Once a week, I had to ride to the neighboring village to the creamery. There was a note that this commandant was to be given half a kilogram of butter per week. They would bring and hand over this portion. It wasn't a case of take as much as you want, but they took the portion that was allotted to them. I can just imagine how much a Soviet commandant would have sliced off for himself.

I remember the winter of 1942 was so severe that it was terribly hard for those Germans. These were obviously rear-echelon troops, not those at the front. They were dressed in their greatcoats, and they were simply perishing from the cold. At the slightest thing—they would run into a house. They would run into the first available house, warm themselves up, and complain that it was “kholodno-kholodno” [cold-cold]. The cold paralyzed them, because it was unheard of for them. And the winter was severe, and there was a lot of snow.

I remember one episode. We had started to have salo, of course. We hadn't had salo since before my father was gone. As I said, we were profiting from the livestock that was wandering around. Two Germans came to the house in the winter of 1942 and showed a roll of coarse fabric, like canvas, though it was somehow soft and quite thick. And they wanted salo for that fabric. My mother looked to see if anything could be made from it, figured there would be pants, which she later sewed for me. My mother opened a large box full of salted salo. The Germans said, three pieces. That was three slabs of salo. My mother only gave two. The Germans insisted on their price, but my mother wouldn't budge. They had to agree.

V. V. Ovsienko: Petro Rozumnyi. Cassette two, December 11, 1998.

P. P. Rozumnyi: They took me for work related to road maintenance. The roads were, of course, in poor condition, because they had been destroyed during the major troop movements after the start of the war. We were sent to the Dnipropetrovsk-Kryvyi Rih road to repair it, to add gravel, and they brought us sand. We were engaged in this, though on our own keep; the Germans only brought us water and supervised the work, but we brought our food from home. We worked as much as we could, no one tried to set a quota for us or demand that we do a certain amount—we just worked slowly without any coercion, and the work progressed slowly.

I think it was then that I first felt how lonely I was in the world. I remember I climbed into the reeds along a small river, and my heart felt so heavy. I thought that I was alone in the world with my problems, as they say today, and that no force would help me—only myself. A kind of sadness in my soul. I remember that episode as a feeling of a new life that had already begun for me, because I had grown up, a teenager—I was already 15-16 years old. I felt a kind of responsibility for the future and had a feeling that I was alone, all alone... A fear of the future... I would call it that I awoke within myself then, but it didn't last long.

OSTARBEITER

Suddenly, they let us go home, and as it turned out later, they let us go in order to mobilize us for Germany. A certain number of people were assigned to each village, and they had to be selected. They were selected by our own people; the starosta [village elder] selected them in consultation with others. I would say they selected fairly: they took into account how many children were in the family, they took into account how many boys, how many girls, because that was important, how many boys and how many girls. Later they took everyone, but in 1942 they still, one might say, counted and combined. So, it was decided to take four boys and two girls from the village, and the lot—it wasn't a lottery, but just a designation—fell on me, on three other boys, and two girls. We, one might say, calmly, voluntarily, we went to Germany. They took us in wagons, they saw us off as if on a long journey, the whole village came out to see us off. We packed our food onto the wagons. There was plenty of food, we baked so many flatbreads you couldn't lift them. We took what we could, and there was plenty to take. We packed good bags with us; the Germans encouraged it. Of course, we didn't have much in the way of clothes; we were half-dressed. They brought us to the station.

V. V. Ovsienko: What time of year was this?

P. P. Rozumnyi: It was June 22, 1942, exactly one year after the war began. They bring us to the station, and there they load us into wagons. In each wagon, two Germans are hanging in hammocks in the air, and we are lying packed together on the floor of the wagon. We had brought some things with us to put underneath us. The Germans were going on leave without weapons and were watching over us to keep order, so that no one escaped, for example. No one ran away, because the Germans were watching, and also there was no mood to run away, I recall. I wasn't planning to run away, I think I intuitively guessed that there was nowhere to run, that I had to go, because here, in the Kharkiv region near Lozova, fighting was still going on. True, in 1942 it had already moved further east, but in the winter, fighting was still going on. I remember a German even told us that there was fighting there, he pointed: "Lozova, Lozova..." He told us how the Germans didn't turn off the engines of their tanks and vehicles day or night, because you couldn't start an engine in those frosts. And when a Soviet army offensive came—you couldn't move, so the engines ran day and night.

They brought us to Dnipropetrovsk and on the same day took us in the direction of Piatykhatky. We were in Piatykhatky that same day towards evening. There they organized the first hot meal for us. They let us out of the wagons—the Germans stood aside and watched to make sure no one ran away. We were told to take our bowls with us. You held out your bowl, they poured hot food into it, it was some kind of soup. We ate it with the flatbreads we had. They didn't give us bread, because we all had our own bread. We ate on the very first evening, though few wanted to. On the first day, we hardly wanted any of it, because we had just left home, the mood—you're going somewhere, you don't know where, what will happen—it didn't give us an appetite. I remember that in Piatykhatky almost no one took advantage of it, almost no one; they got out of the wagons just to get some fresh air.

For the first time, I saw some boys who were either simulating or pretending to be crazy, abnormal. They walked straight at the Germans, stumbling, the Germans pushed them, the Germans beat them, they fell and got up again, like that. It was a very unpleasant sight—the first distressing sight I saw, of violence being done to a person for no apparent reason, because those people were behaving as if they were unable to think and control their actions. I noticed two such people. They got it good in the ribs. They offered up their ribs, and the Germans didn't hesitate to walk over those ribs with their boots, because they were walking in a straight line and wanted to leave, and the Germans wouldn't allow that. So, they were violating the established order—no one was going anywhere, everyone was going to Germany.

On the second day, I remember, they stopped us again and fed us hot food in Shepetivka. Some people started eating there, because not everyone had packed enough food, and there were those who, perhaps, hadn't been properly provisioned from home, or there was no one to give them anything. So more people were eating that slop there. On the fourth day... From Shepetivka to Warsaw, we probably traveled for two days, as I recall. And in Warsaw, they fed us the same way. It was somehow interesting that in Warsaw the cooks were already Polish women, who spoke some incomprehensible language and were dressed differently than our people—cleanly and nicely dressed. They had more wealth than we did, both before the war and during the war, obviously. I remember a very interesting episode where girls and boys, all young, got out of the wagons. And the Polish women were about 40-50 years old, no less, and they were enticing them: “Come here, let's run away,” “Idz tu – tiakaj ze mna!” I didn't see anyone take them up on it, but I think one could have taken advantage of such an invitation to escape, because the Germans weren't watching that closely, the supervision was already relaxed, and there were a lot of us, and the movement was so great that you could have separated from the group and escaped. I remember one Polish woman came up to me, tugged at my shoulder and said: “Where is your chest, where is your strength, why are you so weak?!”—I must have been small and didn't look strong. But it was clear, those were just words, that she was pulling me by the shoulder somewhere else, that is, pulling me away from the group under the pretext that she was concerned about my appearance, which did not satisfy her. Well, I sort of turned sideways to her, turned away, and that was the end of it. There was some kind of bargaining going on: those women, for reasons that are still unclear to me today, wanted to separate someone and take someone with them. I think it wasn't by chance, because young people were traveling, and among those who were doing this, as I remember very clearly now, there were no young ones. They were all women, therefore, perhaps, women without husbands, because the war had passed through, so many had already been killed and the killing continued. That was an episode in Warsaw.

Exactly one week later, on June 29, we arrived in Halle. Along the way, we were struck by something: at the crossings, the train would stop. People were waiting. We were struck by their, as it seemed to me then, festiveness: everyone seemed to be in festive clothes. All those women with carts... At first, I didn't understand what these carts were, but they were baby carriages. They looked us over like exotic animals, because we were a conquered tribe coming from there, from the East. What we looked like. They were probably interested in what these young, beautiful people were like, as I think today. There were people of different ages, mostly women—and young women with children, older women who were looking after their grandchildren, but there were so many of those carriages on both sides of the crossing... It was a spectacle—these people would gather while the train was stopped to look at us, and we would look at them.

Finally, we arrived in Halle. The boys are separated from the girls here. We had been together in the wagons, just as we left the village. I slept next to one girl, and we would cuddle and kiss affectionately, because it was sort of like at the vechornytsi [evening gatherings] back then—without any special intentions, but there was a kind of affectionate relationship. I had a child's imagination about all of it then, but still—I was a young lad... They separate us, we go through sanitary processing. They make us undress, smear the areas where hair grows with a foul-smelling grease. We had a good bath, a shower, and they started grouping us into small teams. We spent the night there, bathed, spent the night, and the next day they were already grouping us. They take forty of us and drive us forty kilometers to the west—to the small town of Eisleben Lutherstadt. I once told a German, here in Kyiv, that I had been in Lutherstadt—Eisleben Lutherstadt, and he said: “Ah, Lutherstadt... There are hundreds of Lutherstadts in Germany. Wherever Luther was, there is a Lutherstadt in his honor. It’s a German custom,”—that’s how this German explained it to me. In this Lutherstadt, the first thing we noticed were three huge chimneys, smoking—this was our enterprise, which, as it turned out, smelted copper ore into a semi-finished product.

They housed us right on the factory grounds on three-tiered bunks. Since we were already finishing our own food, they fed us slop and started giving us bread. Some were already quite hungry and ate it all. At first, I couldn't get used to that carrot soup, I couldn't eat spinach—I just couldn't, it was as disgusting to me as boiled lamb's quarters. I couldn't eat rutabaga, but hunger, it's true, forced me to eat all of it after a couple of days. For us, such food was so unpalatable that I felt you would die from it. I later appreciated that it was the best food I had in my life, wherever I was in a barrack-like situation, that is, in Germany, in the army, and in the zone—I was there for three years each. So here they fed us the best, that is, the most rationally. That vegetable food really sustained us. Vegetable food—not constant kasha or a kasha-based soup, as they gave in the army: a boiled grain floating here and there, and the rest just watery slop, but this—a thick vegetable soup, cooked in broth—was good food. Later we got used to it, it was better.

They sent us out, distributing us as they saw fit: where they were stronger, they sent them to unload coke from wagons with fourteen-tined forks. Such forks, a short handle, so you couldn't stand up straight, because if you straightened up, the Germans would shout: hey, get to it! You can't delay the wagons, unload the coke. The doors opened on both sides, we unloaded as quickly as possible. The wagons, it's true, were small, not like ours, and shorter, the largest being 22 tons, and there were some of 16 tons—these were relatively small wagons. So, if you swung the fork all the way to the corner, you could throw it all the way over here. Me, not being the strongest among them, but on the contrary, maybe the weakest, both in appearance and in condition, and having just arrived from the journey—they didn't send me there, because that was the hardest work, truly hellish. They sent me to the so-called Schortze. This was a slag heap outside the factory grounds, where they would bring molten slag and pour it out. It would solidify there, covering the railway track with its iron sleepers, and our task was to break off that slag that had fallen on the track and sleepers with a crowbar, down into the abyss. By breaking it off, we gradually extended this mountain, because the slag kept coming and coming, and then every three days they would move the track closer to the abyss, so the slag would pour down. That was our task: when we moved it with crowbars on command—the Germans called it zwiken. That is, when you put a crowbar under something and move it, that was called zwiken, they have such a verb.

So, the work was relatively easy, and it was in the open air. And the mountain was so high that you could see far, and below was the railway, with trains passing—in one direction they moved slowly, because it was uphill, and in the other direction quickly, because it was downhill. The terrain there was rugged, and it all depended, because steam locomotives were pulling them, and they weren't as powerful as they are now. When the echelons moved slowly, we could see what they were carrying to the East, because they moved slowly in that direction, and quickly to the West. So we would look: they were carrying all sorts of ammunition. One day, the Germans even said that Hitler was traveling on that line, because first came the draisines, then a couple of wagons, then another couple of wagons, then another couple of wagons—it was all so convoluted... And at the end of the draisines, there were machine guns. It all rushed by so quickly that we... And the Germans were whispering: “Hitler, Adolf Hitler…” or “Führer, Führer…”.

And supervising us was an old man, a disabled veteran, he had been an officer in the first war, without both legs, but on prosthetics, but he walked on his own without a cane, Otto Ulrich. He treated me well, because I had become, so to speak, the translator there, and they turned to me with all questions, because I remembered some words from school, then I had lived for a year under the Germans—I had remembered something. In short, I had a vocabulary that allowed us to communicate, so I was the translator, because there were no complicated conversations there. And they would send me for coffee. At a certain time, a couple of hours after the start of the shift, there was Frühstück—the Germans would sit down, eat their sandwiches, and we ate nothing, because we had already eaten the bread they gave us in the morning back at the barracks, and besides that, there was nothing, but we drank coffee. It was a black-as-night coffee, not real, but brewed from some grains, obviously from roasted barley. It was so tasty that you could drink it like beer. They gave it to us: drink as much as you want, just pour it into your own container. I would bring one such Kaffeekann—a tall coffee pot—they entrusted me to carry the coffee. On the way, I could have thrown trash in it... I would bring it, put it down, they would sit down and eat. There was a small hut, I didn't go into that hut, they didn't let us in. We had nothing to eat, so we had to drink coffee, whoever wanted it, whoever had a container, the Germans would pour it. The Germans watched us and sometimes secretly gave us extra food—one would bring a piece of a sandwich, another would bring a sandwich. They gave extra food primarily to me, because I was the smallest. That Otto Ulrich, who was in charge of this work, invited me to his home twice. And his home was visible from the mountain, he would show me. From the mountain, you could see the villages all around, the churches in every village. He invited me home, he wasn't afraid, it wasn't a big deal for them. He was obviously a member of their party, I remember he wore the badge of a member of the National Socialist party. He would invite me and there he would try to ask about our life. I told him what I could and how I could—later I was able to tell a little more.

Working with us in shifts were Frenchmen, Belgians—civilians. In 1943—British prisoners of war, when Sicily was taken. When the Duce was kidnapped on that pretext, it was at that time that the British prisoners appeared, who had been captured in Sicily, obviously. It was a small group, about twenty people, they wore their own uniforms, with a square drawn on the back. The French prisoners had a triangle drawn on their uniforms, and we had the "Ost" sign. Although we were not obligated to wear it to work, when we went to other places, they required us to wear the "Ost" sign, we would sew it on. I have a photograph with that sign.

Here it is interesting to say what our level of freedom was, this is very important. We were not in a concentration c we were in an Arbeitslager, as they called it, and it was a semi-free existence. After work, we could go freely to the city and into the fields. This was often forbidden, but our boss allowed it; he had some influence in his party in that city. He allowed us to go, only reprimanding us when someone stole something and got caught, or when someone broke trees instead of just picking the fruit, breaking branches—that was the kind of thing.

There was an interesting episode, worth telling, about how one translator, Stefan, a Pole, translated what the boss said—that's a separate story.

So, we worked on this mountain, and it was our salvation. It wasn't hard work there, it was beautiful, we could always observe what a beautiful German landscape there was in those places—these are low mountains, beautiful forests, such a blueness. For me, it was a novelty, because I had lived and grown up in the steppe, I had never seen such things, and for me it was an exotic experience to observe what beautiful places there are in the world. I hadn't seen forests, and I always wanted to go into that forest.

Since we led such an existence, where we didn't have official permission, but no one bothered those who went out. We would walk around the city, do odd jobs for the Germans, who needed coal shoveled... They would bring the coal to a small window leading to the basement, throw the coal inside, close the window, and it would be stored there. Coal was piled up there, and piled up there. If we were walking by, the Germans already knew: “Komm, komm.” For the work, they would give a piece of bread or even a whole loaf, or a ration card. A ration card, if someone had one, was used to pay money. I remember they paid me, as the youngest, the least of all, but it was 36 marks. With this money, you could buy a lot of bread, and if you had ration cards, you could even buy sausage. Later, we did buy it. When the Americans started dropping ration cards for bread and meat from planes as a form of economic, so to speak, sabotage, the Germans got flustered. They started to look very carefully at who was giving them. And we managed to redeem the cards even through Germans, because Germans were trusted, and we weren't—they see you're an Ostarbeiter, so where did you get it? And if it's a policeman, he might even beat you. So we had to give not a full sheet, but tear off a piece. So I say again, we worked on the side, and in season, we picked apples, picked pears. They would give us a bag of pears so big you couldn't lift it—take it with you. The only thing was, if you saw a policeman across the way, it was better to duck into an alley or hide somewhere. He wasn't catching you, not specifically chasing you, but if you were right in front of him, he might ask: "Ausweis?"—if you have a document. You had to have an Ausweis. The policemen didn't chase us, you just had to be careful: if one was coming towards you—turn into a side street or go behind some trees, or just get out of the way, and he wouldn't follow you, even though he could see that something was suspicious. And the policeman wore such a tall cockade that you could see it from far away—like the tall hat on Wilhelm II.

I got into a routine: every day, I would bring apples that I had earned to a grocer, Frau Kaufmann, who lived on Hindenburgstrasse, I gave her all of them, and she would give me groats, vermicelli, all sorts of things like that—for those apples. And she wanted me to bring them, because she would then give them to someone else. So for the Germans, everything was by ration card. Pears, apples—all that had to be on ration cards. And when they gave this to us, it was also a violation, but apparently, they had no other choice, because we were free labor—for those ten kilograms of apples, we worked for several hours and earned them. And then in the winter, I also adapted. The winters there are snowy, so you could go into the apple orchards and look for apples among the leaves that had fallen, unnoticed by the pickers. This was such a vitamin boost, you can't imagine. They don't collect those frost-bitten apples now. They are small, but completely edible.