I n t e r v i e w

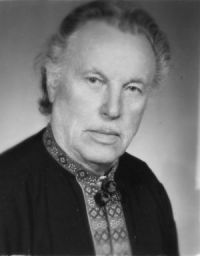

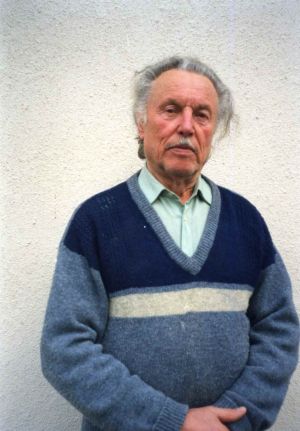

with Myroslav Oleksiyovych M e l e n

With corrections by M. Melen on November 9, 2005.

In October 2005, M. Melen rewrote the first two sections and part of the third, but a few phrases from the recorded text have been retained here. Subheadings are by the interviewer.

Some excerpts have been rearranged for chronological consistency.

The speaker’s specific emphases are highlighted in bold italics.

V.V. Ovsienko: On February 3, 2000, in the city of Morshyn, at 11 Zinoviy Krasivsky Street, we are recording a conversation with Mr. Myroslav Melen. The recording is being conducted by Vasyl Ovsienko.

FAMILY

M.O. Melen: I am Myroslav Melen, son of Oleksiy, born in the village of Falysh, Stryi Raion, on June 13, 1929, into a large peasant family. My father’s roots are from Bukovyna. From that same family tree comes Teofil Melen, one of the organizers of the press quarters in the Legion of Sich Riflemen from 1914&ndash1916. He was killed in battle with the Muscovites in 1916 in the village of Vektoriv.

In 1910, my father followed his seven brothers and left for America. He returned in 1920, after the war. He was the youngest. None of his older brothers returned. But they all gave the money they had earned by that time to my father. He returned to Ukraine and married a widow, Kateryna Pecheniak, who had a son, Vasyl, from her marriage to Pavlo Pecheniak. He had been a Sich Rifleman in Bukshovany’s kurin. In a battle with the Muscovites on Bolekhiv Hill, near the village of Lysovychi, he was severely wounded in hand-to-hand combat. A day or two after the battle, his friends brought him to his native village of Falysh (about 8 kilometers from the battlefield), where he was buried by his 22-year-old widow, Kateryna, with their young son Vasyl, who was born in 1910. Later, she became my mother, and Vasyl my full brother, but only on my mother’s side. I remember that in our home, the memory of Pavlo was sacredly preserved, and my father treated his stepson Vasyl like his own son his entire life. Vasyl studied at the Stryi gymnasium. This required a great deal of money, and my father provided it. He never reproached my mother with a single word. Vasyl studied alongside Stepan Bandera, Tychiy-Lopatynsky, and Yulian Hoshovsky (who later became regional leaders of the OUN). At that time, Stryi was a hotbed of Ukrainian revival and the birthplace of the first OUN underground network. After graduating from the gymnasium, given the political situation, he had to leave his native land and emigrate to Czechoslovakia, to Poděbrady, where the entire nationalist elite of Ukraine had settled after the war.

My brother returned in 1941 with the “Nachtigall” and “Roland” legions. I remember (I was 11 years old) how the villagers flocked to see “Amerikanov’s Vasyl” (to this day, my brother and sisters are called the “Amerikanovs” in the village). He was in a dark-blue uniform with the insignia of an ensign, fluent in German, Czech, and Polish, greeting relatives and friends with tears in his eyes. He let me play with his “Mauser” (without cartridges, of course), and I felt like the strongest, most heroic person. My peers, surrounding me, begged to be allowed to “pull the trigger” just once, to hold it for just a moment. That moment is still before my eyes with all its reality, although everyone has long since departed to the world of ancestral spirits, scattered to foreign lands, or disappeared without a trace.

On an assignment from the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Vasyl later became the chief of the “Werkschutzpolizei” in the village of Rypne in the Stanislavshchyna region. He took his brother Volodymyr (born in 1925) with him. During the German occupation, the Werkschutz post collaborated fruitfully with the OUN underground, providing it, first and foremost, with information, weapons, and food.

Before the arrival of the Bolsheviks in 1944, the entire 22-man post, with its weapons, joined the ranks of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, but I do not know who went to which group or unit. I only know for certain that Vasyl ended up in the kurin of Rizun-Andrusiak and held the position of the kurin’s ideologue. My brother Volodymyr was mobilized as a private rifleman into a sotnia, which immediately went on a raid from Stanislavshchyna to the Zakerzonnia region. Vasyl’s pseudonym was “Borovyk,” and Volodymyr’s was “Bilyi” (he was a light blond). In 1946, Vasyl was killed just before the Easter holidays in the Rozhniativshchyna region and is buried in a mass grave in the village of Tsyniava. Thirty-two warriors of the legendary UPA rest there together.

And back in 1945, on the very morning of Christmas Eve, raiders came to our house in the village of Falysh to conduct a search. They searched for almost the entire day: they tore down the stoves, ripped up the floor, and threw everything down from the attic—they were searching, as a song of that time went, “They broke the chests, looking for Banderites.” In the evening, they took my father away and wanted to arrest him. As my father came out of the entryway, he immediately darted to the side, trying to escape, but a burst of automatic fire cut him down. A drunken Chekist, shouting obscenities, threw a grenade at him as he lay on the ground. After the explosion, my neighbor Dmytro Morych and I took the body (I picked up his arm from the snow five meters away) and buried him by morning without a coffin, because otherwise, the Muscovites would have taken him, and to this day, no one would know what happened to him. As is now known to everyone, this was a method of covering the tracks of the barbaric subjugation of the people. Such a method of destroying nations or peoples was initiated in Muscovy by “Tsar Ivan the Terrible” when he “annexed” the peoples of the Volga region.

IN THE UNDERGROUND

I, an underage youth, was then studying at Stryi Secondary School No. 5. The teaching staff at this school was entirely from the Stryi gymnasium. The student body was as well. To avoid repression, I moved in with relatives in the village of Dashava (15 km from Stryi) and studied at the secondary school there. I semi-officially, semi-unofficially, completed the tenth grade there in 1947.

While still studying at the Stryi gymnasium, I was recruited into the Ukrainian Youth Association (SUM). I officially joined the OUN Youth in 1943 during a ceremonial Plastun (scout) bonfire on Mount Kliuch (the site of a 1916 battle between the USS and the Muscovites) under the leadership of Professor Kokolsky and Father Havrylyshyn, who were leaders in the OUN seniorate (they emigrated to the West in 1944). At that time, there were more than two dozen of us in the youth cheta, which swore an oath with the text of Lentavsky’s “Decalogue of a Ukrainian Nationalist”: “You will either gain a Ukrainian State or die in the struggle for it.” Everyone sacredly upheld this. Only one of the youths of that time became a traitor—Stepan Odynak—but the rest did not break their oath. Most perished in the whirlwind of the Liberation Struggle, or endured Muscovite hard labor without repentance or betrayal. For example, Demko Babiy, the youngest of our cheta, died a heroic death in 1946 in the same battle as his father and brother Mykola in the neighboring village of Stankiv. Ostap Barabash from the village of Koniukhiv blew himself up with a grenade, along with two KGB agents, when he found himself in a hopeless situation.

In Stryi, the Bolsheviks made arrests in 1947, on the very day the graduation certificates were being issued, when everyone had gathered. They arrested everyone in that 5th school who was in the youth organization. My friend and I were not arrested because we were in Dashava at the time. We received our certificates almost covertly—good people arranged it.

With the arrival of the Bolsheviks in 1944, the OUN Youth at Secondary School No. 5 carried out various tasks: some distributed underground propaganda literature, others were couriers, and a third group (mainly city youths like Ostap Markus, Romko Maslyanyk, Volodymyr Zlubko, and others) acquired various weapons wherever they could, while my brother-in-arms Volodymyr Morych and I delivered them to a designated location for the cell leader Orlenko. Or to Somko—the supra-raion leader. Sokolenko was my cousin (killed in 1948 in his native village of Falysh), his real name was Ivan Pavliy. And Somko was Stepan Kleputs from the village of Kamianka in the Skole region. Somko died tragically right here, in our Dashava’s Korchunok (as the hamlet is called)—he did not surrender to the enemy. Their entire combat unit perished. And Somko, wounded, let them get close—the Bolsheviks thought he was already dead and approached him, but he was holding a grenade in his hand, and at the last moment, he released the pin of an “F-1.” He was blown apart, but he also took two Bolsheviks with him.

And then this incident happened. My late, closest friend, who died four years ago, and I took the horses that a milkman used to transport milk from the villages to the collection point in Stryi. We took Uncle Petro’s horses and pretended to be hauling milk. But in the seat, made of pea straw, were ten submachine guns and other weapons. We were crossing the Stryi bridge, which was very heavily guarded. Uncle Petro got down and ran away. How did he run away? He left, saying, “You go on your own, boys.” And so we went and delivered the weapons.

One morning, messengers came from the village of Falysh, where I was born, saying that there was no reason for me to return to the village, as the house was destroyed, the floor ripped up... They had come looking for me again, as my father was already killed and my sister was gone. And so then—where was I to go? When our organization was exposed, we joined Orlenko’s self-defense cell. We went completely underground, with weapons in hand. We were still underage, but holding weapons in our hands, we felt an ascetic inspiration, a full sense of responsibility for our nation.

And here is what happened in 1947. Ukraine was starving then. Many people from Bessarabia, from all corners, were wandering here in Galicia. We gathered for a festive dinner on the Feast of the Transfiguration, August 19, in the village of Falysh, on the outskirts, across the river. A woman approached and said, “Be careful, boys!” There were six insurgent riflemen and two of us youngsters. The riflemen were armed. So, the woman warns us that some people are walking around, begging for alms, but they are young and healthy. And just as she said that, before we could even react, those two uninvited guests knocked on the door. They were about 25&ndash28 years old, with sacks on their backs. Orlenko, the cell leader, invited them into the house, fed them, and asked, “Who are you?” The boys already had experience with this and understood that these were planted KGB agents. One of them was a Belarusian by nationality, the other a Ukrainian: their surnames were Halchynsky and Rayevsky. The Ukrainian was very outspoken, with aplomb: “It will be the end for you! You are bandits! You won’t win this cause!” They came with the intention of convincing us that we should surrender...

They were both taken out into the yard... As I later found out, the first thought was to convince them that the Ukrainian insurgents were fighting for an idea. We do not destroy, as the Bolsheviks propagate here, people of other nationalities—we are fighting against the system. “So you go, be human, and tell them who we are.” But Halchevsky declared, “You are bandits, and wherever we can...”—he spoke in such an uncompromising tone.

It was obvious that the decision was made to simply physically eliminate them. Because if they had been let go like that, the entire household would have been deported and destroyed. There was no other way out. And the struggle then was: life or death. In the underground, we had no prisons, no investigative bodies. It was decided in a flash. We were told, “Boys, tie their hands.” And we, as best we could, with trembling hands, tied them up. “Follow us!” They went ahead. It was already a dark night, with a light rain falling. Suddenly, I heard a shot, then a second, a third. Halchynsky managed to escape, but a bullet caught the other one...

ARREST

When, a few days after the clash with the KGB agents in 1947, we fell into the hands of a raiding party, the agent Halchynsky, who had managed to escape from the insurgents, was already identifying us at the KGB duty office, tied up along with other traitors who had surrendered in response to the MVD of the Ukrainian SSR’s appeal and knew both of us by sight. That episode of my life was perhaps the most brutal!

...On the order of the cell leader, we moved to the neighboring village of Bratkivtsi. The self-defense cell left, as it had its own hideouts and bunkers in the forest, but we, as teenagers, went into the village to stay with relatives overnight, and tomorrow we would see what would happen. Before dawn, the relative said, “Myroslavets! Get ready! Go pasture the cow, there’s a raid, a raid! They’re taking everyone over fifteen, all the men, gathering them at the club, and we’ll see what happens there.” I took his cow by a rope, a воловик as we called it, and drove it out of the village to graze. And my brother-in-arms, Volodymyr Morych, was at another neighbor’s, also barefoot. Well, how old were we then? Not yet seventeen. They saw us anyway and took us. They held us in the club for almost two days. Some people knew who we were. A rumor spread throughout the district that there had been a battle, that they were looking for those who took part in it. No one said that we were from the neighboring village. People were silent. Then the one who had betrayed us back in school, Stepan Odynak, arrived. He just looked into the hall, saw us—and ten or fifteen minutes later, a captain of the red-epauletted officers came in and called out our names: “Melen and Morych! Come out! We know who you are—you and you.” They tied both of our hands together, laid us face down on the floor of the Studebaker, and stood on us. They took us to the district center, Stryi, to the KGB.

At the KGB, we were met by those Janissaries who had surrendered at Beria’s call, former OUN insurgents. There weren’t many of them, but they were there. We had a very famous fighter here once, Limonko. But he turned out to be a provocateur. He tormented all things Ukrainian. Bombyk, Hryn—I’m calling them by their underground pseudonyms. They knew us, and I knew them. So, Limonko was one of the first, already lacing his speech with Russian curses, to start with a beating. Without delay, he took me out into the courtyard (Volodymyr was taken to another room). In the courtyard, there was a large pile of manure, as there were many horses there there were fewer cars, and the KGB agents traveled everywhere by horse. On the manure, I saw something wrapped in a tarp. Limonko, after hitting me, forced me to unwrap it. As soon as I pulled the tarp off, I saw the face of Vasyl Rizhko, with whom we had just had dinner together in the same house two days before. He was older, born in 1926. He wasn’t in the underground he had returned from the front severely wounded. But his father was in the underground. And there I saw him, killed. He was in his holiday clothes, an embroidered shirt. His curls were matted with blood, blood from both temples, an eye was missing. In short, a burst from an automatic rifle had obviously hit him in the head. Limonko said, “If you don’t tell the truth, the same thing will happen to you.”

The interrogation began very actively and continued without a break, day and night, as long as I could stand on my feet. When the investigator went for lunch or was away for a minute, a guard stood over me and wouldn’t let me sit down or close my eyes, trying to wear me out to the point of exhaustion with sleep deprivation. He said, “It doesn’t matter what happens to you! We’ll shoot you.” When I collapsed on the floor, those who had surrendered—Limonko from the village of Dobriany, Bomyk from the village of Zavadiv, Hrim from Bratkivtsi (all these villages are in the Stryi region)—dragged me by my feet from the second floor down the stairs to the basement, so that my skull hit every step. I came to my senses in the basement about three days later. I remember sincerely praying, thanking God for the strength to endure: I endured and did not betray, because I was in the basement. Otherwise, they would have led me through the villages, and I would have had to show where I had slept, who had given me food, and so on. Because all they wanted from me was to tell them in which house we had eaten or slept. Then, probably, half the village would have been deported according to the Bolshevik method. However, God gave me strength, and my brother-in-arms Volodymyr as well—we withstood everything and said nothing. We said that we had been hiding on our own, getting food however we could. The method then was: “I know nothing. And if there’s nothing, there’s no case.”

I was still a minor, had never been in such a situation, except for hearing something similar in stories. It shocked me deeply. They brought me back to the room, and then from the other room came that same Halchynsky, who two days before had had the adventure I described earlier. He lunged at me, beating me, and all of them joined in, so I don’t remember what happened next. They beat me in various ways, doused me with water, and beat me again. Many years have passed since then, but even now I can feel those kicks with pointed shoes throughout my whole body, in every nerve. They also placed me under dripping water and made me stand barefoot up to my knees in water. Each felt like a sledgehammer hitting my head. To this day, I cannot comprehend how a human being—a *homo sapiens*—could do such things. I cannot reconcile myself with the Christian dogma: “If they strike you on the right cheek, turn the other also... Pray for those who persecute you... Forgive your fiercest enemy... You will be saved...” My father, in conversations with his brothers-in-law on winter evenings, often asserted, recalling the world war: “If someone comes to you in peace, meet them with bread and salt, but if they burst in with a sword, drive them out with a sword! Do not betray, but also never forgive betrayal, lest you become a traitor yourself!”

I came to in a basement room, in a cold and damp cell, all alone. A tiny room, about one by two meters—evidently, it was intended for something else.

It was then that I first felt a great strength of spirit within me, the kind that “the spirit yearns for battle,” as the poet said. It was then that I first felt the satisfaction of a moral victory over the enemy, and this confidence that I would endure never left me afterward. And I will indeed boast that I was always one of the first in any conflict: whether in fights with “blatnye” [criminal underworld] and recidivists during transports, or later in resisting the Soviet authorities in the GULAGs, or in freedom.

About two weeks later, they transported both of us to Lviv, to 7 Sudova Street, where we languished through interrogations for over a year. The conditions were very harsh: no parcels or visits, no news of my mother and relatives. An acquaintance from my village, Dmytro, helped end the ordeal with a face-to-face confrontation. In the end, they sentenced us. The death penalty had already been abolished—and they had promised us we would be sentenced to death. Under Article 54-1a, point 11—“terror”—they gave us 25 years each and 5 years of deprivation of rights. As we sang in the cell: “and for greater fear, they gave five years of disfranchisement, so that, as they say, we wouldn’t sin anymore.” And eternal exile “in the remote regions of the Soviet. ”

V.V. Ovsienko: Do you remember the date of your arrest and trial?

M.O. Melen: I was arrested in 1947, on September 23, during a raid in Bratkivtsi—a village in the Stryi Raion. And I was tried in June 1948. What was the date? The 23rd as well, I think.

THE TRANSPORT

On August 19, 1948, again on the Feast of the Transfiguration, they took all of us from the Zamorstynivska prison in Lviv on a transport to the North. Mostly young people. In Pullman cars, with three-tiered bunks.

We traveled for a very long time. The journey was hard. They transported us in the cars in this manner. Once every three days, they gave us a little kilka and some rusks. They only gave us water once a day. There were one hundred and twenty men in a car, and they gave us just one bucket per car. The train would stop somewhere in a desolate place, in the steppe. Unescorted prisoners would fetch water from a lake or some puddle and bring it into our car. We drank it because the thirst was terrible. And after that, people started getting sick—dysentery broke out.

Take my fellow villager, Vasyl Pastushchyn—we met on the transport. He was born in 1922, an insurgent. They captured him in battle, shell-shocked and unconscious. They patched him up and gave him 25 years. He didn’t make it to Norilsk. He died somewhere near Krasnoyarsk from severe dysentery.

Every evening and morning, there was a roll call. Vasyl didn’t get up, so the unescorted prisoners dragged him from the second tier of bunks by his feet (the bunks were three-tiered) and threw him on the floor. To this day, I cannot forget that terrible scene: how his head hit the floor of the car. And then they dragged him out of the car onto the stones. They said something among themselves, laughing: “One less Banderite.” No one knows if he was buried or just left there in the steppe.

Two FD locomotives (the so-called “Felix Dzerzhinsky”) pulled a train of over seventy Pullman cars filled with prisoners. There were all kinds of people, and on each car, the letter “B” was written in chalk and circled. Whether they meant “bandits” or “Banderites,” as they called us, I don’t know, but they were mostly political prisoners. Among us were many “Vlasovites” from the ROA (Russian Liberation Army). There were direct participants of the UPA, but most were those who had helped in that revolutionary liberation struggle. Many were from Dnieper Ukraine. In Kharkiv, at Kholodna Hora, they added many Ukrainians from Eastern Ukraine to our transport. These were people who had taken the side of the national struggle. No one delved into the political situation—the only goal was to be free from the Muscovite occupier. There were many conscious intellectuals.

Only in Chelyabinsk or Omsk were we taken for a “prozharka” [delousing], because lice had become a huge problem. They did a disinfection. It wasn’t until the Feast of the Intercession in 1948 that they unloaded us in Krasnoyarsk, at the Znamenskaya station. They marched the column to a transit point, about twenty kilometers away. They led us on foot across a field (there was no road), through terrible swamps. The convoy was on horseback, only the dog handlers were on foot. They marched us in a column, five abreast. We were not allowed to go around any water or puddle we walked straight ahead, as the convoy commanded. Because: “A step to the right, a step to the left—I consider it an escape attempt and will shoot without warning!”

A very hard journey. We were dressed in whatever we had, and it was already cold there, this being Krasnoyarsk Krai, on October 14, 1948. When they let us out in the morning, we walked those 20 kilometers for probably 5 hours, maybe longer. Rain, wind—very bad weather. I was wearing summer light shoes (that’s what we call loafers), lightly dressed, with no coat, no jacket, just a suit jacket, trousers, and a shirt. My feet got wet, and my shoes fell apart. There were many like me. I arrived at the transit camp, where they processed and registered us, completely barefoot. The ground was cold, and it was raining and snowing. But, thank God, I survived.

At the transit camp in Znamenskoye, they process us according to our files. Each one by surname: first name, patronymic, article number, term, and so on. A work assigner with a beard comes out to us. As it later turned out, he was a Polish officer who had miraculously survived being shot, either in Katyn or near Kharkiv. I didn't speak with him much, as I was very young then. As soon as he heard it was the Lviv transport, he received us warmly and said without fear: “They will approach you, they will rob you, they will beat you. But you fight back as best you can, and no one will say anything to you for it. Because here, it’s the law of the taiga: it’s every man for himself.”

The transit camp was large, divided into sectors: a women’s zone—for common criminals, politicals, and hard-labor convicts. And the same for men: common criminals, hard-labor convicts, and politicals under a special regime.

The transit camp consisted of a couple of huts on stilts with a roof but no walls. And a couple of huts that had walls but no windows. So, everyone tried to get into those, because a very biting rain and wind had started. We, a group of young guys, found a couple of boards. There was Yaroslav Skavinsky, Viktor Mytarchuk (he was from the Kyiv region, I don’t know what happened to him), Ivan Matviychuk from Brody, Ivan Ohorodnyk from the Stryi region, Volodymyr Morych, and many others who had stuck together since prison. Young guys, almost the same age. We made a loft in a barrack that didn’t have walls yet. We climbed up there. At night, we heard screaming, because common criminals had broken in on us. The guards let them in on purpose. And someone was shouting, “Beat them! Beat them! Beat them!” We jumped up, because someone had already climbed up to us. The boys grabbed the one who had climbed up and threw him down. He just thudded to the ground and didn't get up again.

In the morning, the guards came for the roll call, counted us, and just asked, “What is this?”—“We don’t know.” And truly, no one else asked: who it was, who did it. The unescorted prisoners came, put them on a cart, and took them away.

GORLAG

At the end of October 1948, we arrived in Norilsk, Krasnoyarsk Krai, at the “State Special-Regime Camp No. 4.”

A very hard story: hunger, cold, and we were utterly exhausted. They loaded us onto barges, and two weeks later, brought us to Dudinka. This was the last transport of that year, because you could only get from the mainland to the Taymyr Peninsula, into the Norillag system, via the Yenisei River or the Arctic Ocean through the Kara Gates—and into the mouth of the Yenisei. Or by air. So, GORLAG—“state special-regime.”

In Dudinka, there were so many deaths they couldn't be counted. How many of us made it, how many arrived—no one will ever count, even today. The mission of “State Special-Regime No. 4” in Norilsk was to build the largest copper-smelting complex for non-ferrous metals—a gift for Stalin’s birthday. That’s how I remember Stalin’s birthday—December 21 his seventieth birthday was in 1949.

About ten thousand prisoners were brought to the camp from different parts of the Soviet . An interesting contingent. I found members of the governments of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia there, which Moscow had occupied in 1940. There was Ukrainian intelligentsia, there were engineers from the Donbas. I remember Mykhailo Kriachko—a major mining engineer. There were Russians from the so-called “Gorky affair.” There were prisoners from 1937, from the Solovetsky Islands. They had miraculously ended up here. They spoke among themselves about the Ukrainian intelligentsia, even mentioning the name of Les Kurbas. But I didn’t know who that was at the time. Only now do I realize it.

One of the greatest personalities who influenced me was Professor, Dr. Mykhailo Dmytrovych Antonovych. The son of the Antonovych who was the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Central Rada. He was a professor at the University of Berlin. Bolshevik agents kidnapped him from Paris in 1947. He told me that he came to his senses in the Lubyanka prison in Moscow. He was also sentenced to 25 years. He was an orderly in our barrack. Antonovych was an encyclopedically educated man. Mykhailo Pylypchuk, a member of the Writers' , was with me. He now lives in Mykolaiv in the Lviv region. He wrote a lot about Antonovych.

There were many intellectuals there, like General Belov—a Vlasovite. There was the former Soviet ambassador to Canada, Oikhman, a Jew, who was tried in 1937. By the way, in January 1953, the “Doctors' Plot” flared up in the Kremlin. We came back from work, and the loudspeaker announced that a Jewish group of doctors had been exposed, which had intended to poison Stalin. Oikhman said to the whole barrack, “Watch what happens. They’ve forgotten who brought them to power!”

And indeed, two months later, before dawn—the polar night was still ongoing—we were marching to work. The column, about four thousand strong, was lined up five abreast. Only the shouts of the foremen and guards: “Catch up! Faster!”—when suddenly from the watchtower loudspeaker came the announcement: “Today, due to a cerebral hemorrhage, Joseph Vissarionovich...” —and so on. In that instant, from the chests of those unfortunate, tormented, tortured slaves, a cry erupted into the polar sky: “Hurrah! Hurrah!”—they threw their hats in the air, rejoicing, celebrating the death of the “leader.” Captain Nefedyev, the officer on duty at the watchtower, turned pale. I could only see his sinewy, drink-ravaged face turn red with tension as he shouted, “Calm down! Quiet! Quiet!” Finally, he gave the command—and from the watchtowers above us, bursts of automatic fire rang out. That’s how we calmed down. Everything fell silent, and life went on as usual. We went to work, but now we were cheerful, happy, because we felt that great changes were coming to society.

So, Oikhman had said, “You’ll see what happens.” Not even two months passed before Vissarionovich had his “hemorrhage” on March 3. To this day, I am convinced that a Masonic-Jewish mafia rules everything and everyone, including us now.

The men of all nationalities lived there in friendship. We were especially friendly with the Balts, particularly the Lithuanians, and with the Georgians, because in the Soviet Gulag camps, there were probably all the nations that inhabit Europe.

THE NORILSK UPRISING

And so, events unfold like this. In May, the polar summer begins there. The transition from winter to summer happens at once there is almost no spring. The first flowers in the tundra have very bright colors, like the aurora borealis. But they have no scent, no aroma. Two or three days—and they disappear without a trace. And the summer begins. Summer is summer—sometimes it’s ten degrees Celsius, and there were days when it was even fifteen.

We came back from work. The sun no longer sets—the polar day had begun. Youth takes its toll: as we loved to do, we gathered in front of the barrack and began to sing. We are singing. And I am standing in that circle. The changing of the guard is walking by and shouts, “Disperse!” Even though he had never done that before. But now he suddenly shouts, “Disperse!” We pay no attention. He takes his submachine gun from his shoulder and—fires a burst at us. Two victims: Haisiuk from Berezhany and another—I’ve forgotten his last name. Yevhen Hrytsiak described it.* *(Yevhen Hrytsiak. The Norilsk Uprising (Memoirs and Documents). Second edition, revised and expanded. &ndash Kyiv: Olena Teliha Publishing House. &ndash 79 pp.). Two victims, instantly. This became the catalyst—the entire camp rose up. It immediately spread to the fifth, and the sixth women’s zone. Within a day, all of Norilsk knew about it. And the Norillag administration included over one hundred and forty divisions, OLP (otdelny lagerny punkt, or separate camp point). I have this data written down. In Norilsk alone, there were more than twenty camps. There were about 150-160 thousand prisoners in Norilsk. Everyone worked for Russia. We did everything there. Now they are paying compensation to Ostarbeiter—when will they pay us? Seventy percent of the prisoners there were from Ukraine.

V.V. Ovsienko: And we still owe Russia so much!

M.O. Melen: Yes, and we are still in debt—we are eternal debtors! If I recall those first steps—in that camp, even the bunks were not made of planks, but of unhewn logs. No one had any idea what a mattress was, or a blanket, or a pillow, or a spoon, or a pot. People ate however they could. The most valuable thing we had back then was a tin can. The gong would sound—lunch. If you didn’t eat, no one cared whether you had eaten or not. Everyone ran, in the literal sense of the word. I had nothing to eat from, so I would take off my hat: “Pour the balanda [thin soup] into my hat!”—and we would gulp it down like that. And whoever had a pot or some tin can would quickly drink it and give it to a friend, saving one another. That’s how it was until 1949.

There were about 10,000 of us in the 4th camp of Gorlag. Navigation begins at the end of May and ends in October. So from October 1947 to the end of May 1948, out of those ten thousand, less than two and a half thousand remained. And the rest... The unescorted prisoners had two pairs of horses... There was a popular song, “A Pair of Bays.” Every morning, the dead were stacked in a pile, and when they were taken away, the guards at the watchtower would pierce each one in the temple and chest—that was the procedure—and they would be taken out to Shmidtykha... Mount Shmidtykha. I have it here in a book...

V.V. Ovsienko: Yevhen Hrytsiak also wrote about this.

M.O. Melen: Yes, yes. So one can imagine what our life was like. The workday was 12 hours, from 8 to 8, without days off, without any sick leave. The so-called sick leave was only when you could no longer get up: you wouldn’t be taken out of the zone for a day or two. And anyone who refused to go to work was made an example of: they would take a horse from an unescorted prisoner, strip the prisoners naked—three or however many there were—tie them by their feet to the swingletree, and the horses would drag them feet first through the entire zone to the watchtower. And the authorities would round everyone up: “Look! The same will happen to you if you don’t go to work!” They were dragged through the zone, pulled out of the zone—and no one ever saw them again.

It was leading up to an uprising. I wouldn’t say it was an organized uprising in the usual sense. I have my own interpretation. I was on the strike committee, for which there is a document. We came together on our own. Hrytsiak writes about this too. They had arrived in a new transport from Karaganda. And we, who had arrived back in 1948, stuck together, did everything jointly. There was a widespread system of informants. In the large zone, that is, in the state, and in the small zone, informing was encouraged: whoever cooperated got easier work.

We agreed that we would protest against the lawlessness, because the dictator Stalin was gone, and we were innocent victims. There were many people there without citizenship, including myself, because we were occupied in 1944. We were young, victims of the war, and we demanded a review of our cases.

Some describe the uprising in a way that is unpleasant for me to read. And foreigners sometimes look at us with amazement. We resorted to means of protest that were permissible under Soviet law. Because for any other method, they would have simply shot us. Some say and write that they sent tanks and airplanes against us... That is absurd. No one sent tanks. We were unarmed, defenseless, hungry, and exhausted. They were looking for a reason, staging provocations, and if they had found a knife, it would have been a reason to shoot us all down to a man. We protected ourselves there could be no armed, forceful protest. There was only one means—we don’t go to work, a strike and a hunger strike. And to get information outside the zone. We made paper kites with leaflets: “Help us, save us.” This is recorded. A Jew wrote one (I don’t remember his name now), Klimovich from Belarus, the Balts, a Frenchman named Jacques Rossi, Yevhen Hrytsiak, and I wrote too. We’re not saying we were armed. I don’t want to belittle anyone, but I believe we performed a great feat by standing up against the terror then. There’s no need for greater heroism, because no one in that system dared to rise up as we did. We in Norilsk held out for 70 days. We always compared it: the Paris Commune—71.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what is this document you have? Could you perhaps read it? In its entirety.

M.O. Melen: I am not making a hero of myself, but I want to read a certificate given to me by the KGB administration of Krasnoyarsk Krai, where our files are still kept. I will read it in the original language, with explanations:

“Top Secret. Number 51 (something illegible). Certificate. On June 6, 1953, a team of MVD USSR officers held a discussion with representatives selected by the prisoners of the 4th camp division of the Gorny Camp. The following acted as representatives of the prisoners: Halchynsky, Nedorostkov (these were from the Russians, I will explain shortly), Hrytsiak (from the Ukrainians), Henk (from the Germans), Klimovich (from the Belarusians), Melen (from the Ukrainians), Dzeris (from the Lithuanians).

The discussion lasted for 3 hours. At the beginning of the discussion, the prisoners stated that the local camp leadership should not be present, and then asked with whom they would be speaking, to which they received the answer that they would be speaking with a commission appointed by L.P. Beria.

Deputy Head of the 5th Department of the UMVD of Krasnoyarsk Krai, Captain of State Security Sigov.”*

*(Published in: Yevhen Hrytsiak. The Norilsk Uprising (Memoirs and Documents). Second edition, revised and expanded. &ndash Kyiv: Olena Teliha Publishing House. &ndash p. 27.).

The commission from Beria was headed by Colonel Mikhail Kuznetsov. Before his arrival, they addressed us via megaphone or loudspeaker: “He cannot speak with everyone, there are too many of you—each nation should choose its own delegates, and we will speak with you. You will present your complaints, and we will try to consider them.”

So, the moment came when someone had to be sent. Before that, I had been constantly communicating with Mykhailo Dmytrovych Antonovych. By the way, he was the first to tell me about Yevhen Malaniuk he personally knew the leaders of the OUN, remembered Melnyk and many others well. He told me a lot about Ivan Bahrianyi. He was educating me. He said, “Go! Go!” Well, what was there to say—we had already agreed. I will say that I went not because I knew a lot, but because, perhaps, my spirit took over. Because when we went, we knew that the Bolsheviks always eliminated the initiators.

The meeting table was set up outside the zone, beyond the watchtower. Many people saw us off. There were guys from the Stryi and Lviv regions. We said our goodbyes and parted, because I didn’t think we would return. But, thank God, they brought us back. Apparently, a different time had come. Each of us expressed our opinion, and they took notes. Interestingly, Kuznetsov said, “It’s strange. Such strict isolation between the camps—and how did you all agree that...” That the issues and demands were the same everywhere. This probably points to something else. But this question has not yet been researched, and I don’t know if it ever will be—how everyone mobilized like that, because within a few days, all the camps went on strike. All of Norilsk came to a halt. And that was an event of no small significance—the world started talking about us! We know this now, but we didn’t know it then. For seventy days we did not go to work, though they tried to force us. They agreed to review the cases. And our people were at the end of their rope, and so were they. Some decided to go to work. Others wanted to hold out longer. But before dawn, the red-epauletted troops burst into the zone. They surrounded each barrack separately. They beat us mercilessly, to death, to near death, and drove us out of the zone. Some grabbed their belongings, some didn't. They drove us out into the tundra, and there the “suky,” the snitches, pointed us out, and they sorted us, sending us to different places. The neutral old men were returned to the zone, but we—some were taken straight to the investigative prison, some to the punishment cell, some to be transported.

And so I end up in the punishment zone, it was called Kupets, or Kalargon. They brought about eighty guys there. We weren't in this punishment zone for long. The conditions there were horrific. From there, they take us to the Norilsk prison. That was a terrible prison. It was larger underground than above. They tortured, tormented, and shot people there. Here's how they "welcomed" you to this prison: they bring you into the courtyard, everyone stands one by one. In the corridor in front of the office, they strip everyone naked. They push you into a cell—and hit you on the head from behind. I don’t know with what—I lost consciousness. I came to in the cell.

I found myself in the cell—naked, with my things beside me. And they beat you in such a way as to not leave any bruises. They would lift you by the arms and legs—and throw you flat onto the cement. It was cold, unheated. Ivan Ohorodnyk from Koniukhiv in the Stryi district and Slavko Skavinsky from Sokal were already lying there. What’s wrong with us? I want to relieve myself, I go to the slop bucket. Nothing comes out, just clotted blood. Terrible pain. And in the morning, as if in mockery, a female Chekist comes: “Any sick people?” she asks through the food hatch. &ndash “Yes.” &ndash “You should be finished off.” &ndash And she slammed it shut. Just to mock us. Many of us died. God helped me survive, I thank Him for that. My faith and hope saved me.

The investigation begins. It lasted almost a year. We thought they would shoot us. But the death penalty was no longer in use then. Well, what could they do: add to our sentences. But we weren’t afraid of more time, because we all had 25 years. They sentenced us to the “krytka” [internal prison]. Me, for three years. There were five of us: Viktor Mytarchuk, Mykola Popchuk from the Ternopil region (he was a povit [district] leader of the OUN), Ivan Matviychuk from the village of Haii Didkovetski in the Brody district, Yaroslav Skavinsky from Sokal, and me.

THROUGH PRISONS

They took us, a group, back to Dudinka, then onto a barge—and the ordeal of the transport began again. To prevent us from staying too long in one prison and making contacts, they didn’t keep us in any one prison for more than three or four months. Our group (I don’t know about the other groups), thanks to those Bolshevik procedures, got to tour almost all the major prisons of the USSR: Krasnoyarsk, Omsk, Tomsk, Chelyabinsk, Petropavlovsk-on-Ural. From there, from the Urals—to Gorky, from Gorky—to Vladimir, from Vladimir—to Kharkiv, from Kharkiv—to Rostov, from Rostov—to Grozny, and then back up the Volga by barge—to Gorky. We kept returning to Norilsk like this until 1956.

And so the “Khrushchev Thaw” found me. We had already served three years in prisons it was time to return to Norilsk. They brought us to Krasnoyarsk, but since the navigation season had already ended, they sent us to the “Voroshilov factories.” These were some kind of gold-refining plants I didn’t look into it. We had to wait for spring—and then they would send us to Norilsk again.

But here they separate us. They take me “with my belongings” and transport me. Where to? I have no idea. I hadn’t had any correspondence with home for three years. Absolutely none, with anyone. What else is interesting? We were in Orenburg (then the city of Chapayev) in the same prison where Shevchenko once was: the Orenburg fortress.

They bring us to another prison. We had camp numbers. They call out your last name, and you have to respond with the formulaic data: first name, patronymic, article, term, and so on. There was a practice: you answer with your first name and patronymic, but you don’t say the article and term there was one phrase: “Until the end of Soviet power.” They beat you again, but we stuck to that answer as a matter of principle. Every one of us. They call out, for example: “Melen, Myroslav Alekseevich! Article?”—I’m silent. “Term? Speak!”—“Until the end of Soviet power.” And immediately: “Ah, you...”

Back then they called us “Berievites.” This point has not been clarified to this day: in 1956 or 1957, by Beria's order, the border with Poland was opened. (Beria was arrested on June 23, 1953. &ndash Ed.). Not for long, maybe a month or so. And a call was put out: “National cadres!” So they made us “Berievites,” because Beria had already been shot, and we, supposedly, wanted to dismantle the Soviet . For some reason, no one sheds light on this topic to this day, what that was all about. Whether it was a provocation, or if Beria really wanted to install national cadres, I don’t know, but such a fact existed. Because many of the visiting Muscovites got alarmed that only local cadres should be everywhere.

In Krasnoyarsk, spring and the “thaw” find us. It was already much easier. In those Krasnoyarsk camps, at the “Voroshilov factories,” there were mostly Vlasovites from the Russian Liberation Army. Many Belarusians who had served in the German civil police. These were people with a slightly different mindset. The Chekists said that cutthroats were coming to them. And there weren’t many of us, just five guys. The whole zone met us in the evening—the “cutthroats from Norilsk.” By then, they allowed us to have hair in the camps, they didn’t shave our heads anymore, and watches were permitted. I end up in the brigade of a Georgian, Dakishvili (they scattered us one by one). I don’t remember his first name, but I remember Dakishvili well. He had already been primed by the Chekists: “Listen, if you start acting up, I’ll finish you off myself!” That was the conversation I had with him. But we managed to conduct ourselves in such a way that later they were all on our side.

TO FREEDOM

The Easter holidays arrive. The navigation season hasn't started yet. I say to the Georgian: "Listen, we are Christians! It's Easter! Let's do something." There was already access to civilian freelance workers—drivers and others. We ask them to buy some vodka. I had never had vodka in my life, never tried it. It just happened that way. I was arrested as a minor, and it wasn't a custom among us. That was our upbringing. And we managed to smuggle in a couple of bottles. They caught me as I was coming back from work, carrying a quarter-liter bottle in my sleeve. They order me: "Go to the watchtower now, have dinner, and then come to the headquarters." Meaning, I should turn myself in democratically. But I didn't turn myself in—for three days, the entire holiday, I hid in the zone. They do a headcount, and I'm somewhere under the bunks...

Finally, the holidays passed, and the head of the guard service (he was Ukrainian, Captain Cherniak) meets me in the zone (they already knew everyone by sight). I was hiding until they caught me, but I was going to end up in the BUR [punishment cell] anyway. Where else could I go? A slightly comical situation. And he met me: "Ah, you kid! Why are you hiding, trying to start an underground in the camp? Don't you know you're supposed to be going free? You're a juvenile. Look, they've come to review the cases." I didn't know about this. There had been talk that cases would be reviewed. "What were you fighting for—to have your case reviewed?"—They knew everything. "Well," I say, "what's to be done, citizen chief?"—"Go to the barrack, pack your things, you're being sent on a transport tomorrow!"—"Where to?"—"I don't know where, but there will be a case review."

And indeed, they took me. I got nothing for the vodka. They would have locked me up, but something else happened. They are taking me to Ukraine. They transported me via transit prisons in a "stolypin" [special prison car]. Packed like sardines. From Lithuania, from Ukraine, from Belarus, from Latvia. Everyone had their own case, but that no longer interested anyone.

An incident. In Kharkiv, at Kholodna Hora, they put us in a transit cell. It was large, about sixty men, if not more. Packed so tightly there was no room to lie down. Some are sitting with their bundles, some are being transported for case review, and some are newly arrested. A lot of common criminals. I'm alone, but I teamed up with two Lithuanians, the three of us. I understood I was going for a case review. And there are these big guys with full bundles. Obviously, from parcels. Recently sentenced. The common criminals approach one of them and say, "Muzhik!" [peasant, chump]. They take his bundle, take his food. We, from the camp, didn't have the courage to say, "Give me something to eat." But these guys are taking it. And these are big men, guys who probably served in the army at one time. One of them was some kind of chairman... And they don't dare to speak up for themselves, not a word. Then the Lithuanian, Ivankus, says, "Why are you silent? Hit them!" And it turned out that we gave them courage. The men jumped up and started thrashing the criminals! A living mass tangled together, and you couldn't tell who was hitting whom! The food hatch opens, they spray us with water to calm us down...

I am going for a case review, and so are those Lithuanians. They could pin a new crime on us. We immediately broke away and went to a corner. They are sorting out the case. The guards saw us sitting in the corner, because they already knew who came from where. &ndash "Tell us, who started it?" We saw what was happening. The criminals had already stripped the men, taken their boots, sweaters, shirts. The guards took the criminals out into the corridor (they were good guys, apparently) and gave them some more. And we gave this advice: "Men, you're going to prison. If you're as meek as you were here, you'll perish like a priest's ducklings. You have to stand up for yourselves!"

In Lviv, my case is reviewed: a minor.

V.V. Ovsienko: When did you arrive in Lviv?

M.O. Melen: In early June 1956. The investigation was conducted daily, they were checking. Here, in Falysh, two from the cell I was with remained. One died last year, the other is still alive, he's over eighty. They only surrendered to the authorities after Stalin's death, in 1954. Our future depended on them—mine and my comrade Volodymyr Morych's. They testified well: they were just kids, they said. And so, I remember, on the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul, July 12, they released us.

They released both of us from the Brygidky prison in Lviv in the evening. I was dressed for winter, didn't even have a cap. Quilted trousers... I didn't know Lviv. We came out like frightened chickens. Where to go? I always carried a toothbrush, soap, and a couple of books wrapped in a towel. Shevchenko, my favorite poet, and the Hungarian revolutionary poet Sándor Petőfi. I love him very much to this day. Religious books were not allowed, and we didn't have any, although many sectarians were imprisoned with us. They were tried for anti-Soviet activities. So, I had these two books—and that was all. We came out onto Horodotska Street. They gave us tickets to the Stryi station. Where to go? Some people were laughing, while others, our people, approached us, crying, and showed us where to go, what to do.

We arrive in Stryi at night. From Stryi to Falysh is seven kilometers. We walk. People from the night shift join us, and then: "Oh, what an event!" They recognized me. I arrive at my house... Pause for a moment... I arrive at my house. I knock on the window... The people who were walking from work are standing on the road... And my old mother... She's 82 years old, she gets up: "Who is it?" &ndash "It's me, I'm Myroslav." &ndash And my mother fainted (M.O. Melen weeps). I break down the door—people helped... She hadn't heard from me for three years. They had already held masses for me, memorial services, panikhidas, everything they could. And—the son appears... I'll calm down in a moment—please, turn it off. (Dictaphone turned off).

Forgive me for crying now, but now my nerves and my age are not what they were. But when I had to bury my father as quickly as possible, because the Bolsheviks would have taken the body... And then where did they put the bodies of the killed? We have thousands buried in unknown places, which we are finding today in garbage dumps... I remind you that my father was killed outside our house on Christmas Eve. I, a minor, burying my father, did not shed a tear. I just resolved that I must avenge my brother's death, my father's death. I must avenge. And, as I could, I fought against that regime. But today I've relaxed, I'm crying, please forgive me.

When they were releasing us, the prosecutor gave us instructions not to disclose secrets, because there are such and such laws. I ask if I have the right to apply to study. I didn't understand then what rehabilitation was. He said: "You are a full-fledged citizen, you can study." This made me very happy. The entrance exams begin. By the end of July, without even having a passport, I went to apply to the Drohobych Music College.

V.V. Ovsienko: And how was that release classified?

M.O. Melen: I have a certificate somewhere, it was classified as: "No element of a crime." And as a minor. It was motivated by the law on reviewing the cases of those who were arrested as minors.

V.V. Ovsienko: So it was rehabilitation?

M.O. Melen: Yes, it was rehabilitation. We were all rehabilitated then—my friend Volodymyr Morych, and those who had short sentences, like 5 years. For OUN, but only for leaflets. But Morych and I had a different article.

I immediately enrolled in the Drohobych State Music College in the conducting department. The next year, I enrolled in Lviv University in parallel. When the exam sessions coincided, I would ask to take mine first, take a taxi from Lviv to Drohobych for an exam. That happened too.

V.V. Ovsienko: And which faculty at Lviv University?

M.O. Melen: At Lviv—philology. I wanted to go into journalism, but there was no such department back then. There was a journalism department from the third year, but my diploma says "Ukrainian, philological." I worked in a school, and I wrote, and so I have to this day. In three years, I completed the four-year college course. I knew and loved music a little, so I passed the exams for the third year as an external student from the first year and graduated from the college in 1958. And I graduated from the university in 1961.

UKRAINIAN NATIONAL FRONT

And here my new epic begins. When we were taking the entrance exams, there were many of us in the university corridors. They were only admitting one group of 50 people, and we had seven groups of 50 applicants. I could tell by their faces who was who, because there were many like me. And there I met Zinoviy Krasivsky. He had come from Karaganda and was also applying to the university. We got to talking—intuition prompted us. He didn't go back to Karaganda after the exams. I took him home to Falysh, and we became spiritual brothers, united by ideals, by struggle, by everything. Because his whole family, too—two brothers killed, parents exiled, they had died.

Living at my place in Falysh, we often talked about painful topics. We had other friends-in-arms. We could not reconcile ourselves with the terrible assault on everything Ukrainian. And especially then, they were forcing former participants of the liberation struggle, members of the OUN and UPA, to make public repentances. Almost every holiday, either on a Saturday or a Sunday, in some village, they would hold general meetings on the topic of condemning the OUN and UPA. It was a terrible business. I discreetly attended one village, then another. This deeply offended us. What were we to do? Would we reconcile ourselves and silently listen as they trampled on our national Ukrainian ideas, on our statehood?

We discussed various options. And then came 1963. From Vytvytsia—Zinoviy Krasivsky's homeland—an acquaintance of his, older than him, Bohdan Ravliuk, comes to visit us. He worked as a history teacher there, in the village of Vytvytsia. The same things pained him as us. He could not reconcile himself in any way. They talked as relatives. And then Zinoviy told me that there are people who also cannot reconcile with it. After some time, Bohdan Ravliuk came to us again and said that he also has a like-minded person, a history teacher, who works, I think, in the village of Kropyvnyky in the Kalush region. This is Dmytro Kvetsko. He is also obsessed with this idea, already trying to write something—how to proceed.

I know the laws of conspiracy, that where there are two, it's no longer a secret, and where there are three, it's news for the whole village. But I talked to Zinoviy—and I join. About two months later, Bohdan Ravliuk and Dmytro Kvetsko came to us. Zinoviy and I had already moved to Morshyn by then. Zinoviy lived on his side, and I on mine. We built the house together, did everything together, we shared everything. No one ever asked anyone how much anything cost: we got what we could, worked as we could. And so they come to Morshyn. We decide to an organization that would continue the traditions of the liberation struggle of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists.

V.V. Ovsienko: It is important to note when this meeting took place.

M.O. Melen: This meeting took place in early spring, around March 1964. We discussed the issue that we would form the backbone. I met Kvetsko then, but I immediately warned: if, God forbid, something happens, I don't know you, and you don't know me. Because I knew how Soviet law judged a group case versus an individual case. And so we agreed. Later, when the investigation proved that he had been in Morshyn x number of times, I said that I didn't know him, that he had come to court my sister-in-law. Because my wife has five sisters, one of whom, Stefa, is Krasivsky's wife. So I said I wasn't interested in that, I didn't know him. That's how I behaved during the investigation to the end regarding Kvetsko.

So, we decided. But to organize something, you need some means, some platform, some printed word. Because just talking—there is support, there is sympathy—and that's where it ended. I don't want to say that our Sixtiers did little or did something wrong, but from the point of view of an OUN member, I will say frankly that here in Galicia (I mean Mykhailo Horyn and many others)—it was pure cultural activism: they gathered, talked, read a poem, sang a song. That was very good, it was great progress! But there was no statute, no obligations. And what about us? We worked according to a statute, so to speak, according to the canons of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. With us, whoever joined had to know the Decalogue and the rule "Speak of matters with whom you must, not with whom you may," and that "you will either gain or you will perish," and everything that was in the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. It's not the time for armed struggle now, but if necessary, we must take up arms. All these are the principles of the OUN, absolutely.

We decided to publish a journal. We thought about what to call it. But first of all: what to name the organization? To call it the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists—that would be plagiarism. It's not possible, because the OUN, as is known from history, was already neutralized after the assassination of Roman Shukhevych. There were attempts to continue it somehow. After Shukhevych's death, Vasyl Kuk (pseudonym Lemish, he now lives in Kyiv) succeeded Shukhevych, leading the armed and theoretical struggle of the entire national underground. He held its leadership in his hands until his arrest in August 1954.

By the way, I want to say that when he was arrested, we were in Norilsk. New people came and said that Kuk had been arrested. We knew—I, for example, and those who were with me—that Vasyl Kuk was leading the underground after Shukhevych. The very mysterious circumstances of his arrest gave rise to various rumors and versions. Most were negative. Even Ivan Hubka, who was with us then in Norilsk, and other guys said that this could not be forgiven. Whoever returns must clarify this issue to the end. Well, time has now clarified everything, that Kuk is an honest man, that he has nothing dishonest on his conscience regarding our cause, he did not sell anyone out. He was cunningly caught. And the Bolsheviks knew how to do that.

I know about Fedir Dron from the Khodoriv group. One of them, Soroka, received the death penalty and was shot. But Fedir Dron remained. They did it like this. Forty of them were tried in a group. And those with shorter sentences, the Bolsheviks suddenly pardon. And they cast a shadow, because a pardon means he must be an informant. The man is innocent before God, but distrust has been sown. If you were pardoned, you must have done something, they don't pardon you for your pretty eyes. And you already have a split, there is no more unity in the organization. And there won't be until death. And how many have left the arena in undeserved disgrace! The enemies knew how to trample on our honor, especially how to exploit the mentality of that centuries-old Khokhol [derogatory term for Ukrainian]. And that’s what happened here.

I want to return to this topic. In Norilsk, during my first imprisonment, they forbade us from gathering. So we would secretly conspire: listen, it's Shevchenko's anniversary. So after work, we'll go to such-and-such a section, in such-and-such a barrack. So-and-so will say a few words, and you remember a poem, so you'll recite it, or we'll sing quietly. When the guards found out, they would put us in the punishment cell for it. I took an active part in such evenings. In Norilsk, we prepared fragments from Shevchenko's "Nazar Stodolia." Someone there knew the roles by heart, but Professor Mykhailo Dmytrovych Antonovych knew the most. He wrote it out for us: "Boys, do it this way." He was writing a history of Ukraine there, and we studied those manuscripts. The 25-year-termers—who knew if we would ever return? But we didn't talk about that. What a spirit there was! That was 25 years! How would I survive in those conditions? But we worked and didn't think about it: will I return or not. The idea was above all else. I want to emphasize this point.

And when I was imprisoned for the second time—I'll jump ahead a bit—the prisoners in Mordovia condemned any participation in amateur performances. I ended up in Mordovia from the Lviv television studio. The Morshyn amateur group was a showpiece for the entire Soviet . We performed at trade congresses of medical workers in the Palace of Congresses. So I had to sing "I Glorify the Party" there, because there was nothing else. And in Mordovia, my wife brought me an accordion, I gathered people and sang "Sheep, My Sheep...", something else for an encore. For that, some condemned me, saying I was "helping the party," collaborating with them... I say, "Why? I wasn't singing 'I glorify the party.' I sang what my soul wanted to sing, something Ukrainian." But they even reproached me to my face later, Horyn and others. Well, I replied: "Say what you want, but I did not dishonor the Ukrainian idea by singing 'Sheep, my sheep...', or 'Ash Trees,' or 'Chervona Ruta,' or 'Two Colors.'"

But let's return to the matter at hand. So, we are organizing a journal. First, what to name the organization? OUN—not possible. The OUN is paralyzed we won't take upon ourselves the mission of restoring the OUN—we don't have such authority. They'll say it's plagiarism. No need. Dmytro Kvetsko thought a lot about it. He was, so to speak, the "locomotive," credit must be given here. Kvetsko was the first to act in this matter. They asked for the death penalty for him at the trial. So he said: "National Front." Everyone immediately picked it up—a wonderful idea: "Ukrainian National Front."

Now, the journal. Someone suggested "Volya" [Freedom], Mykhailo Diak suggested "Surma" [Trumpet]. But collectively, the name "Volya i Batkivshchyna" [Freedom and Fatherland] was born. I knew how to draw a little, and there's a self-taught artist still living here, a talented guy. He was also imprisoned the first time for the liberation struggle. I imagined a trident in a crown of thorns and that cliché "Freedom and Fatherland," I sketched it out roughly, and he perfected it. Then Zinoviy Krasivsky carved it—he knew how to make all sorts of stamps, he had a talent for it. When he makes a stamp, even if it's an official one, it doesn't matter—it's a perfect match. The first time he escaped from Karaganda, he made his own documents. Then they caught him, gave him five years for escaping. He wasn't convicted the first time he was deported with his parents to Karaganda in 1945. I'll come back to this, because there are some misunderstandings about his prison term. I know it as if it were him, because we were the closest of friends for many years and lived in the same house.

When Zinoviy Krasivsky was deported, he decided to escape from Karaganda to here, to Lviv. He made himself a certificate, forged a stamp himself, and escaped. They caught him here after a few months and gave him a 5-year sentence for violating the passport regime. Then he lived with his parents, worked in a mine. There he got into a terrible accident, got a second-category disability, and a pension. And when we were here, he married my wife's sister. His wedding was in my house. His children were born here—Myrosia, who is now in Canada, and Slavyk, who is still here. We lived and worked together, and then we were tried together.

So, we decided on the journal "Freedom and Fatherland." The first issue was printed in this house, on that side, in Krasivsky's room. The first, second, and third issues. How did we gather materials? Kvetsko wrote, Krasivsky wrote, and I did in part, but less. Kvetsko and Zenko wrote the most. I did some editing. I practically had no time, but where could we get news? There were no connections abroad then. So, we divided the duties. I have a "VEF" radio, that tube-based "Ural." So I listen to the BBC, and you listen to "Deutsche Welle." Write down what you can.

In this way, we got news, because the journal covered political affairs, but there were also world news, and even sports. The journal covered a little of everything. I also got Professor Zinoviy Huzor involved. He worked and still works at the Drohobych Pedagogical Institute, now a pensioner. He provided a lot of material. We printed an article "On the Occasion of the Trial of Pohruzhalsky," Ivan Dziuba, and others. When the first issue of the journal came out—we rejoiced. I say (true, Kvetsko wasn't here then, but Zenko was, Holubovsky): "Boys, if we work and last for half a year in this manner, we are blessed by God." And we, thank God, lasted for three years. That was a phenomenon at that time, a unique case. Because if we had written and hidden it under the floorboards—well, we could have been doing that until now, and no one would have known.

We joked that we wouldn't last more than six months if we worked at such a pace and with such methods. But there was no other choice. Once we committed, we would work. At that time, a congress of the Communist Party was taking place—I don't know which one by number. We decided to send a declaration-statement to the congress, to announce our existence.* *(See "Memorandum of the Ukrainian National Front to the XXIII Congress of the CPSU." March 1966. In the book: The Ukrainian National Front: Research, Documents, Materials / Compiled by M.V. Dubas, Yu.D. Zaitsev &ndash Lviv: Ivan Krypiakevych Institute of Ukrainian Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 2000. &ndash pp. 274-275). Because before that, it was interpreted that any nationalist manifestation was a foreign provocation. And we wanted to prove that we are here, that it is not a provocation. We composed the declaration beautifully. Mykhailo Diak took it to Kyiv. He was a senior lieutenant or captain in the militia. Kvetsko had recruited him into his group.

Mykhailo, in his militia uniform, took it and dropped it off in such a way that on the second or third day of the party congress, that letter was being read. Shcherbytsky summoned Nikitchenko, who then headed the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR: to investigate and report. From that moment, the active search begins.

V.V. Ovsienko: It’s interesting, how was it possible to get into the congress?

M.O. Melen: He dropped it at a post office in Kyiv. There was some kind of postbox for the congress there. He delivered it personally, to it directly into the box. I don't know where, because I wasn't there. So by the second day, the letter was in Shcherbytsky's hands.

We started to work very actively. I had a rather rich library, which was left to me by my brother and parents, but it was scattered among people. I brought it here. I still have a fairly large library. When we were convicted, they took a whole flatbed ZIL truck full of books from Zenko Krasivsky and me. Then they sold them at auction, because they sentenced me to confiscation of my part of the property. My wife paid it off with the books. Some people who bought them returned them to me when I came back. I gave them their money back, but most were lost.

How did our activity begin? I know nothing about Dmytro Kvetsko's Ivano-Frankivsk group. I know it exists—and that's all. But who, what? I, knowing the laws of conspiracy, people. These are the people, I'll name specific names: Ivan Hubka in Lviv (he is now the regional leader of the Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists). He worked very actively. He organized the Lviv group, his network even reached Volyn—Korolchuk and others (this came out later). Here from Skole, Yevhen Horoshko, from Drohobych, Professor Zenon Huzor. From Chernivtsi, Hrytsko Prokopovych. In Lviv, Bohdan Krysa (we've already talked about him). And they found more people. How it was with them—that's their business. I also recruited a very active person at the television station, Oleksandr Heranovych (now in America). He was the chief director of musical programs at Lviv Television.

I gave literature to many people (I gave it to those I trusted), but to say they were involved, bound by an oath—that was not the case.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what was the print run of the journals?

M.O. Melen: One batch was produced—sixteen or seventeen copies.

V.V. Ovsienko: On thin paper, right?

M.O. Melen: On thin paper. How did Zenko do it? Only now has some of it become clear. When the journal printing began—we saw it couldn't be done in the house. Because there were many vacationers here. Zenko is typing, the typewriter is clattering... We needed to find another place. Dmytro Kvetsko organizes a bunker. He will tell you where, specifically. Well, I know where now. I warned that no one should know. He chose one person, and the two of them dug it. We gather the materials, edit them here—and Zenko, on a Saturday or whenever, takes a backpack, goes to Bolekhiv, and from Bolekhiv—there.

Several times he told me: "Let's go together!" I categorically refused him. And I stressed: "Zenko! Conspiracy! Where there are three of us, we'll later be blaming each other. You know, Kvetsko knows—and that's enough." When Zenko said it was a bit cold there, that heating needed to be installed, I ordered it from a guy (who was also involved in our organization), he made it and took it only to Bolekhiv. The guy's name was Stepan Sardynets. He lives in Ternopil. And it's a good thing it happened that way. Because when they later arrested us... But first, let me finish about the bunker.

So, they arrested us. "Where was it done? Where? Take us! Show us!" Even if I wanted to tell them—I didn't know. It was a dead end for them. I'm not saying there was a betrayal, but Krasivsky took them there. Now a book is coming out, that Yuriy Zaitsev is publishing. There's even a photograph there of him showing us*. (*The Ukrainian National Front: Research, Documents, Materials / Compiled by M.V. Dubas, Yu.D. Zaitsev &ndash Lviv: Ivan Krypiakevych Institute of Ukrainian Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 2000. &ndash pp. 335-336). So, Krasivsky took them to where he printed. It's not some kind of betrayal, just dotting the i's. But there were such rumors—maybe they reached you—that "Melen gave up that bunker."

V.V. Ovsienko: I haven’t heard anything like that.

M.O. Melen: But it reached me, because Horyn hinted that someone somewhere had let it slip—either Kvetsko or Zenko. I didn't investigate it, but it hurt me a lot. And to justify myself—to whom and with what? Well, they say: time will reveal what is hidden.

We thought and planned in such a way as to respond, if possible, to every event. We published, I believe, sixteen issues of the journal. I took them, Hrytsko Prokopovych would come. Whoever could, retyped as many as possible, and each distributed them, while the first copy was kept for the archive, which was with Bohdan Chernykhivsky.

V.V. Ovsienko: So it was a small print run—one batch. Was it reproduced further?

M.O. Melen: Yes, it was reproduced further, because we couldn't provide for everyone. Hrytsko took them. I told him: "You, Hryts, sit down at a typewriter or find someone, and retype four or five copies." And so it was reproduced further. Back then, there were no Xerox machines, no duplicating equipment. But the work was done at a high level.

ARREST OF THE UNF

The investigation begins. We felt that they were "grazing" us [watching us]. When they arrested us, I couldn't understand in prison who had sold us out. Later, I asked Dmytro Kvetsko. He had involved the now-deceased Yaroslav Lesiv, a physical education teacher. A great patriot, a young man, he was the youngest of us, very dedicated to the cause. After graduating from the physical education college, he was sent somewhere to the Donetsk region. He wanted to recruit someone there, gave the journal to someone. That person played the "good old boy" but took it to the KGB. They asked him where it came from, what, and how. That's how the investigation began, until it reached Morshyn.

Before March 23, 1967, I was preparing a major musical program for television, "Boyko Wedding"—the music and libretto were mine. A kind of operetta. They were introducing "new traditions" then: a woman grants the marriage in the village council, that's how a new family is born. We are recording for a day, two. The amateur performance was very strong: a dance group, an orchestra... The recording lasted three days. They go home, and I stay. It was the last day before the arrest. They tell me to stay—there will be a discussion with ethnographers at the obkom [regional party committee]: some rites and traditions need to be changed. I stayed. We arrive. They took me to the agitation department of the obkom, or whatever it was called. They tell me that some things need to be changed. Because in my script, it ended with Lysenko's "Where there is harmony in the family, there is peace and quiet. God blesses them..." How can "God bless" a Soviet person? A discussion begins.

I leave there, spend the night, and in the morning, I go home. Two men sit next to me on the bus. They brought me from Lviv to the station in Stryi. As soon as I get off the bus—they immediately take me by the arms. As if colleagues going for a beer, so I didn't even have time to orient myself—and straight into a "Volga" car. Before that, there was a question: "Do you have a weapon?" What are they on about? They know I'm coming from Lviv—would I be traveling with a "weapon"? But it was probably a tradition of theirs.

They brought me to the prison, to a solitary confinement cell. Our investigation lasted a long time. I hear a noise: there, there, there. I already knew that Hubka was arrested, Prokopovych was arrested. We were each in solitary. But Zenko wasn't there. About a month, two or three later, I find out that Zenko is in Ivano-Frankivsk, Stefa is taking parcels to him there.

It used to be: "No, I don't know." But now they had all the material, laid out like on a map. I read Bandera's appeal to the Ukrainian youth—the title was something like "On the Prospects of the Ukrainian Revolution." He says that the idea must be defended at the proper level. But we had already come to the conclusion ourselves that we would not deny it: "Yes, I did this." And Zenko says: "Yes, I did this. I wrote this." The investigator then: "So who among you did it?" Each took the blame for everything.

We enter into a discussion during the investigation. The investigator, Colonel Klymenko, was handling Zenko's case, and Kyrsta was handling mine. When a conversation started—I would corner him, because I was already speaking openly about Soviet reality. So Klymenko eventually says: "Let's stop! I'm at work. Answer the questions!" You understand: "I'm at work." Because he couldn't answer anything anymore—regarding language, culture, history, economics.

(V.V. Ovsienko: On February 3, 2000, in the car on the way from Stryi, Mr. Myroslav Melen added.

M.O. Melen: As soon as the investigation began, they would tell us individually, each one separately (because we were in separate, isolated cells) to dress cleanly, shave, and they would take us by car from the Lonskoho Street prison to the KGB Administration on Dzerzhynskoho Street.

They lead me into an office. At the tables are some unknown people. At the main table sits a man who introduces himself: "I am Nikitchenko (I don't remember his first name)—head of the Committee for State Security under the Cabinet of Ministers. We want to talk to you, to discuss some issues. Here is the first question: what pushed you into anti-Soviet activity?" They pestered us with these questions for two or three days. They were investigating: maybe the university curriculum was not right, that it was inciting us to anti-Soviet activity. After all, anti-Soviets are mostly humanitarians, although there were tech people too.

Remark (Mr. Zelensky): What was the breeding ground?