I n t e r v i e w with K. I. M a t v i i u k

(Corrections and additions by K. Matviiuk on 06.16.2006).

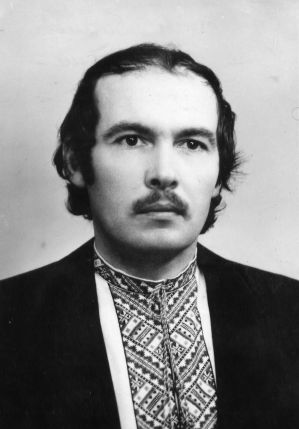

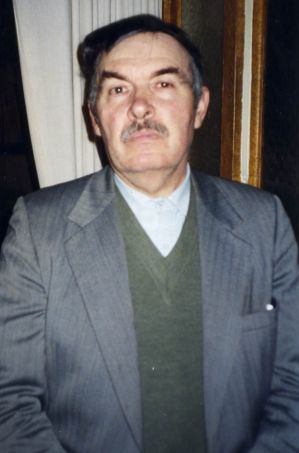

V.V. Ovsienko: December 10, 1998, in Kyiv, at 30 Kikvidze Street, apartment 60, we are conducting a conversation with Kuzma Ivanovych Matviiuk. The recording is being made by Vasyl Ovsienko. Today is Human Rights Day. I have just returned from Zhytomyr, and Kuzma Matviiuk has come from Khmelnytskyi.

K.I. Matviiuk: My last name is Matviiuk, my first name is Kuzma, and my patronymic is Ivanovych. I was born on January 2, 1941, in the village of Ilyashivtsi, Starokostiantyniv Raion, Khmelnytskyi Oblast, which at the time was Kamianets-Podilskyi Oblast. My parents were hereditary peasants, grain farmers; for as long as they could remember, they had lived in this village. And it seems my relatives never lived in any other village. My grandfather once served in the tsarist army and went through the entire imperialist war. According to stories, he came back from the war, so to speak, a little “red” because he would tell people in the village how oppressed Ukrainians were, that they were oppressed by the tsarist regime, and that there were people like the Bolsheviks who wanted to free people from the tsarist web. He had ten desiatinas of land, but when the Bolsheviks later took this land from him, he became very disillusioned, and until his death, he called any party members nothing but scum. His name was Musiy Kostyantynovych Yaroshchuk.

My grandmother, Oliana Doroshivna Kozak, came from a Cossack lineage; she remembered all this and told it to me. They were landless and for a long time managed to avoid falling into servitude by not taking land from the landlord, thus remaining free. She carried this love of freedom with her and passed it on to her family. Having ten desiatinas of land, it’s understandable that my grandparents’ family was dekulakized. During collectivization and the famine of 1933, five of the seven children in my grandparents’ family died; only two survived—my uncle Terentiy and my mother Darka.

I have a vague memory of the Germans. The Germans who were in our village even tried to teach us German, and when the Russians returned, I already knew a few German words and understood a little. So, if the Germans had stayed, we would know German as well as we know Russian.

I received my first trauma from the regime as a preschooler, because I was gathering leftover grain stalks and the *lanovyi*, as he was called, chased after me. This was a village man, an activist on horseback. I ran from the horse and into the thickets where there was a swamp, and there I lost consciousness. I came to in that swamp. When I told my mother at home how I had run with all my might because I was afraid of being sent to prison, I was very disappointed when she listened to it all and said, “You’re a fool.” I was completely crestfallen. “Why? What for?” She said, “They wouldn’t have taken you.” I asked, “Why not?” She said, “They don’t take ones like you—they take those who can work.” Meaning, to labor.

The second time I clashed with the regime was in the lower grades—I don’t remember exactly, maybe second or third grade—when the teacher was telling us very beautifully about the great Stalinist transformations. And I, with absolutely no intention of being critical and with no complaints against the regime, but simply with childish naivety, believing in the great Stalin, asked, “Then why aren’t there any of these Stalinist transformations in our village?” To my great surprise, the teacher started yelling at me: “I know where this is coming from! It’s coming from your parents!” Then my parents were brought into the conversation. Understandably, my parents also had long talks with me about it. It was a lesson. After that, I fell silent for a very, very long time and didn’t ask any more questions. In fact, I was terrorized and completely crushed.

I was given another social lesson in the raion center of Starokostiantyniv. I was perhaps in the fifth or sixth grade when my grandmother took me to Starokostiantyniv before school started. She had collected some eggs, churned some butter, and carried it all to sell in Starokostiantyniv to buy me pants or shoes for school. She took me with her to bargain for the money and to have me try them on so they wouldn't be too small. The main thing was that they not be too small. She stood there with the eggs, and people came up to buy them. Who was buying back then? Russians were. There was a large airfield in Starokostiantyniv, and these were the wives of heavy bomber pilots. Jews also bought from her, as there were many of them in Starokostiantyniv. And so I remember a fairly young woman approaching, perhaps half my grandmother’s age, and she condescendingly pointed her finger and asked, “And what do you have there? What are you hiding?” When she jabbed her finger at my grandmother, I thought my grandmother would get indignant, explode with anger, and say, “You little brat, who are you to point at me like that, who do you think you are?!” But to my great surprise, my grandmother said so meekly, “No, I’m not hiding it. I have butter here under a leaf so it doesn’t melt in the sun.” At that moment I felt even more hunched over, so to speak; I understood, as I later read in the *Kobzar*, that we were on our own land, but it was not our own.

In 1957, I finished ten grades and worked for a year in the Donbas at the Makiivka Metallurgical Plant as a locksmith. I got a little sick at that job, returned home, and for two years I worked as a machine operator on a collective farm in the village of Ilyashivtsi. At that time, the mechanization of collective agricultural production was underway. It was necessary for literate people to work with the machinery, so we, simple peasants, were allowed to get an education. I passed the competitive exams and in 1960 entered the Ukrainian Agricultural Academy in the city of Kyiv, graduating from the Faculty of Engineering in 1965. This was the time of the “Khrushchev Thaw.” I remember that we were already a bit more liberated and even dared to criticize, at least among ourselves, Nikita Sergeyevich himself for allowing the same cult of personality to be directed at him, the same praise, and so on.

After graduating from the Agricultural Academy, I served in the army, and from 1967, I began working as a lecturer of special disciplines at the Uman College of Mechanization. I knew what Uman was, that it was a historic city, the center of the Koliivshchyna, and from the first days, I went to the local history museum. I approached a research fellow at the museum, Olha Petrivna Didenko, and asked what they had that was unpublished but that one could read about the Cossack era. I remember Olha Petrivna asking a bit suspiciously, “Why are you interested in this?” I said, “Well, I love the Cossack era, and if the Zaporozhian Sich existed now, I would leave this college and go to the Sich.” It turned out to be like being accepted into the Cossacks back in the day: you cross yourself, drink a glass of horilka, and you’re a Cossack. Similarly, this was enough for Olha Petrivna to introduce me to a native of Uman, Nadiia Vitaliivna Surovtsova. She was a rather unique person. She lived in Uman, had graduated from the gymnasium in her time, then studied in St. Petersburg, where the 1917 revolution found her in her third year, followed by the Bolshevik coup. She returned to Kyiv, worked in Hrushevsky's government, and then emigrated with the government. She completed her higher education in Vienna, where she defended her doctoral dissertation. Then, in Vienna, she met Yuriy Kotsiubynsky. He convinced her that her place was in Soviet Ukraine because a new, Soviet Ukraine was being created there. And so, with faith in Ukraine, even a Soviet one, she returned and was arrested in 1927. Her life was split: until she was thirty, she was, so to speak, climbing the ladder of her career; then she spent thirty years in captivity, returned in 1957, and lived in Uman for another thirty years. Her house at 6 Kommolodi Street in Uman was a kind of national salon or circle, or whatever you might call it. Almost all the dissidents from Kyiv visited there. I met Ivan Svitlychny there, and I met his sister, Nadiia Svitlychna. Of the historians, Yaroslav Dashkevych, now a Lviv academician, was a frequent visitor. Many dissidents came from Moscow; for instance, Solzhenitsyn lived there for two weeks in the late 1960s while gathering documents for *The Gulag Archipelago*.

What happened there? There were constant discussions, and you could read everything. By that time, we already knew about Ivan Dziuba and Valentyn Moroz. We distinguished, at least, between two currents: the irreconcilable Valentyn Moroz, who called things by their proper names, and the people who said we needed to return at least to the achievements that existed before 1929, to the Ukrainization that had been permitted by the Bolsheviks. We unearthed Bolshevik documents and made legal attempts, so to speak, to restore “Lenin’s nationality policy,” although we understood perfectly well who Lenin was. Whether it was true or not, we used to say that although the supporters of Valentyn Moroz called things by their proper names, they weren't doing anything. But we, who were proceeding almost from Leninist positions, could legally push for the implementation of the Ukrainian language, supposedly by citing Lenin, and defend Ukrainian culture—that is, raise the Ukrainian issue. And we even managed to achieve some things. For example, at the Uman College of Mechanization, we managed to get all lecturers of Ukrainian nationality to switch to teaching in Ukrainian. They began to lecture in Ukrainian. And in about 1970, the Russians were told they were being given a few years to learn the language. But then came 1972, another pogrom, and the issue was dropped.

So, proceeding from these positions—supposedly returning to Leninist norms on the national question—we could make public speeches at seminars, hold evening events, and give lectures. I lectured on the Koliivshchyna and touched upon many issues there, such as the national liberation struggle, the preservation of our national identity, and so on. That was already the era of samvydav. What impressed us most was Mykhailo Braichevsky’s work “Reunification or Annexation?” It was incredibly interesting that what we were thinking was, it turned out, broader and even scientifically substantiated by such a well-known historian, a candidate of historical sciences. And then, so to speak, our handbook became Ivan Dziuba’s work “Internationalism or Russification?” where, also supposedly from Leninist positions, the Russification and the entire contemporary policy of the Communist Party in Ukraine were condemned. We made photocopies of this work and passed them around to be read. The circle of readers, of acquaintances—to say it was very wide would be untrue. After a while, this circle of readers was exhausted, and what remained were people who might read it or might not—the indifferent ones. We had to work with the indifferent ones in this way: if it was a correspondence student, he needed help with his coursework. For the coursework, he would usually have to pay some money. He was offered a barter: he wouldn’t pay, but he would read a photocopy of Dziuba’s “Internationalism or Russification?” and tell no one that I had given it to him. There were those who read it, and there was a category who didn't. And there was a third type: the moment you said you would give them something to read about Ukraine, they would already be looking over their shoulder to see if anyone was listening, and they wouldn’t want to talk to you or have anything to do with you anymore. I think this was a kind of genetic fear passed down from their parents.

At that time, things were going well for me. I had a big, and still have to this day, a rosy dream—postgraduate studies. I was good at metallurgy, and I wrote a decent research paper on steels for tractor tracks. This paper and I, as a person, were liked by Mykhailo Petrovych Braun, a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences, and he, so to speak, secured a full-time postgraduate spot for me. All that was left was the formality of passing the exam, because if the supervisor has already “secured a spot” for you, the exam is just a formality. But by that time, unfortunately, I had already been noticed by the authorities, and when I was taking the exams in the winter of 1972, they were already watching me closely. The commission of the Agricultural Academy, as I later managed to find out, had already been informed about me, and they gave me a “C” on the entrance exams, despite the protest—a rather sincere and stormy protest—of this corresponding member, Mykhailo Petrovych Braun. And that was the end of my postgraduate studies.

Of course, we were all in plain sight; we were very easy to figure out. Because all three rooms of Nadiia Vitaliivna Surovtsova’s apartment were bugged, as it turned out later when we became a little more knowledgeable about KGB matters. And my room, where I lived, was also bugged. I was living in an apartment belonging to Nina Ivanivna Domenytska, the niece, I believe, of Vasyl Domenytsky, a Shevchenko scholar who died young. My room was thoroughly bugged from January 1972 until the day of my arrest on July 13, 1972.

They took me to Cherkasy, put me in a pre-trial detention center, and the most difficult period of my life began. The bargaining with me started. The KGB said I had to “disarm.” I said that, in fact, my whole dream was to research steels for tractor tracks, postgraduate studies, and scientific work in the field of metallurgy. They said, “For now, forget about your scientific work; think about how to get out of here.” I, of course, asked, “And how do I get out of here?” They said, “You must disarm, and then we will think about you.” And for about two weeks, the conversation went on daily that they would think about me, and I would disarm. What did “disarming” entail? I was supposed to characterize my actions, as they said, from party positions, that is, to show all my activities and demonstrate how hostile they were to our social system and the Soviet people. Then I had to unequivocally condemn these activities of mine, and I also had to show where it all came from. Under no circumstances was it supposed to have come from me in a process of reflection, because that would immediately cast a shadow on such Soviet institutions as the Komsomol, which I had gone through, the Pioneer organization, our Soviet school, and the Soviet institute. They suggested the sources to me: it was supposed to have come from Nadiia Vitaliivna Surovtsova, from, so to speak, an “un-finished-off Ukrainian nationalist.” When my head had been shaved in the detention center, I asked my investigator, Kovtun, “What am I now, an enemy of the people?” He said, “No, you are a fragment of the un-finished-off Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists.”

It was an extremely painful process; I agonized in my cell for those two weeks. They constantly pressured me: “You won’t achieve anything by this.” For instance, I had to say who gave me “Internationalism or Russification?” to be reprinted. They would say, “We know who gave it to you, and that man has long been imprisoned and is awaiting trial. He has hundreds of episodes like this one of yours, and this new episode of yours will neither add nor subtract anything for him, but you will disarm yourself if you tell us.” And so I tortured myself: “Well, it’s true, it won’t add anything for him, I won’t harm him, and I’ll get out, I’ll do my scientific work, and I won’t go to prison.” But, with God’s help, I suppose, after two weeks of torment, I finally decided that I would not condemn my activities and would not point fingers at other people. But this cost me dearly. The man they put in my cell with me was a currency speculator; he influenced me and also tried to convince me that I was unlikely to get out of there alive. He said, “The KGB? They’re not people, they’re beasts, you can’t expect anything good from them. The only way to get away from them somehow is to do everything they say.” He constantly pressured me like that, and I made a decision, a very difficult decision, that if things were so, I would have to die. This decision was very, very difficult; I wanted to cry. I wrote a letter to my mother saying that, unfortunately, this branch of our family would probably end with me. I asked for my mother’s forgiveness, referring to the fact that we had many branches—her 7 brothers and sisters had died, and now this branch was ending tragically. I asked her not to despair, but to let our branch continue through the two children left by my uncle.

After I made this rather difficult decision about myself, things got easier for me. I endured the interrogations much more easily. When I kept refusing, they would ask, “So you won’t tell us?” and I would answer, “No, I won’t.” And after that, the interrogations went much more smoothly.

At the end of 1972, I was sentenced to four years. The prosecutor had asked for five. By the way, there was a system in the courts back then: if the accused cited the constitution, saying he did what was in the constitution, the court would give him as many years as the prosecutor requested. If he cited human rights and the United Nations, the court would not give as much as the prosecutor requested, but the maximum under that article. I, however, said that yes, I did it consciously, but after my term was over, I would work in my specialty and lead a lifestyle like everyone else, and I would not engage in politics. In addition, I denied several episodes, and the court could not prove them. Instead of five years, they gave me four.

At the beginning of 1973, I arrived in Mordovia, at camp ZhKh-385/19. It was the largest zone. I called it a zone of unknown people connected to politics. It was, so to speak, the second league, class “B,” while class “A” included Chornovil and Vasyl Stus, who were in a smaller zone, 385/3.

After serving my term, in the summer of 1976, I was solemnly escorted by plane to Cherkasy, accompanied by two soldiers and one warrant officer, in handcuffs. It turns out they escorted people so ceremoniously back then because prisoners traveling through Moscow would immediately give interviews there.

They didn’t let me go to Uman; they sent me home by bus, to where I lived in the Khmelnytskyi region. For six months, I couldn’t find a job. They put me under administrative supervision for a year, a kind of house arrest, as someone who, in places of deprivation of liberty, “had not embarked on the path of correction,” as they wrote back then. For six months, I couldn’t find a job. They constantly terrorized me: “We’ll jail you for parasitism.” I don’t know why they didn’t, maybe because I meticulously kept a diary of my job searches and recorded the rejections from jobs in my specialty. There were more than enough jobs for an agricultural mechanical engineer—it’s not a very rewarding job, specialists were needed, and at first they would hire me, but then, on the second or third day, when I brought my work record book, where it was written: “Imprisoned by court decision under Article 62, Part One,” they would refuse me. I kept this diary and wrote to all the prosecutor’s offices I could. So, they didn't end up jailing me for parasitism, and after six months, I got a job. However, until 1982, I couldn't hold any job for more than a year, because either they would fire me after a year for various reasons, or they would create such conditions that I was forced to quit myself.

During this period, there was a break in my public work.

I started my public work again around 1988, when we created the public organization “Spadshchyna” (Heritage) in Khmelnytskyi. Then we created the Ukrainian Language Society, and then the first cell of Rukh in Khmelnytskyi. I was a delegate to the first congress of Rukh, and from the end of 1990 to the end of 1992, I headed the Khmelnytskyi city-raion organization of Rukh and was co-chairman of the Khmelnytskyi regional Rukh. Around these years, a little later, a group of us who had been repressed created the regional organization of political prisoners and the repressed, which I still head today.

I have a relatively large family. My wife, Sofiia Petrivna Matviiuk, maiden name Nechyporuk, is from Volyn. Her father, Petro Nechyporuk, was a soldier in the ranks of the UPA from its very first days. In 1943, they fought battles with the Germans and gave them a lot of trouble. They fought a battle in trenches against a German military unit, and the Germans sent aviation against their company. The aircraft literally shot almost the entire company from the air. Almost all the boys were shot, including my father-in-law, back in 1943. After the war—not immediately after, but in 1947—Sofiia and her mother, Vasylyna, were deported to Prokofyevsk, Kemerovo Oblast, where they stayed for 20 years. Then they returned to Ukraine.

We have three children—two sons and a daughter. They are quite grown up now, all over eighteen, adults. Today, all of them are students at institutions of higher education. Two sons are studying at the Faculty of Engineering at the Agricultural Institute, and our daughter is studying at the Faculty of Law in Ivano-Frankivsk. I currently work as a leading specialist in the Department of Farmer Development at the Regional Department of Agriculture of the Khmelnytskyi Regional Administration.

Thinking back to Uman, I recall some amusing things. For instance, I would often approach acquaintances, friends, and even people I barely knew and say, “Come over, let’s talk about Ukraine.” Most of them would start looking around to see if anyone had heard what I proposed. But we already knew this: if a person got scared, it meant they were one of us, because if you ran into a secret collaborator connected to the KGB, he wouldn't look around but would say, “Yes, fine, let’s talk.” It was already suspicious when a person wasn't afraid.

It’s hard to recall things off the cuff now, but I remember that almost all the students from the pedagogical institute with whom I had conversations, to whom I gave something to read—what struck me was that not a single one said they were indifferent to these Ukrainian matters. They were all concerned with Ukrainian affairs. Later, the KGB processed all of them, and they too went through a painful experience, and some, it seems, have remained silent to this day. Why have some become so silent that I don't hear from them even today? When I was arrested, and the rest were witnesses, they were told, “You know, oh, this Matviiuk, he’s a rabid enemy of the Soviet government and our socialist reality; and you are students, you will work in schools. How did you end up with such an enemy?” And these were teachers, some of whom were already school principals by 1972, so they had to show how bad I was. At first, none of them found anything hostile in me; they all denied it: “No, he says normal things.” Then they were told, “So what, you want to go where Matviiuk is? You can go where Matviiuk is.” Then they would start looking for something strange and anti-Soviet in my behavior. And it would seem as if it was their own initiative to recall these things, their own authorship. That's why they became so withdrawn that even when 1991 came, when Ukraine was independent, when the KGB was long gone, these people are still silent because they are afraid that if they say anything for Ukraine now—even though I don't see them now—they are afraid I’ll appear somewhere and say, “Ah, so that’s how you talk now—but what were you saying back then?” They were put in a position where the “motherland would forgive them” for going astray by associating with me, but they had to prove their loyalty. And so they proved their loyalty to the cause of communist education. And to this day, I hear absolutely nothing from many of them. I don't know how they feel about these matters now, because their souls were truly broken and destroyed. I remember the students, young guys like Oliynychenko, Mykola Baziak, Vasyl Dovhanych, Volodia Moroziuk—they were all passionately involved in these matters. They even had, so to speak, “episodes,” because, for example, Mykola Baziak and Moroziuk were already school principals in the Uman region after graduation, and they were guilty of “sedition”: they collected memories of old people about the famine, they pushed for children to have national costumes, embroidered shirts, they revived embroidery, and so on. They already had a sort of criminal record because they were “fascinated by antiquity,” and that was already not good. They had to prove that they weren't so bad after all.

Of the Uman locals, as far as I can recall now, my closest friend in the matters of, so to speak, Ukrainization was Vasyl Bilous, who incredibly irritated, simply infuriated, the investigators of the Cherkasy KGB. Instead of condemning me—and he was a party member—Vasyl Kuzmych Bilous not only did not condemn me before the KGB, but he defended me in every way possible, and even brought me a package and insisted that it be given to me. At that time, this was a rather heroic act on his part, and for them, it was audacity, a challenge to the regime. He, in fact, paid for it, because in time he too was sentenced to three years under Article 187-prime—that’s for “slander defaming the Soviet state and social system.”

The second was the already mentioned research fellow Olha Petrivna Didenko, an Uman poet, to whom, by the way, these words belong: “Поети не вмирають. Ти наче Бог, ти можеш все, ти можеш рай зробить з болота, ти долі не корись, ти відсіч долі дай, мерзоті ти скажи: мерзота.” At that time, to tell filth that it was filth was also quite risky. Her son, Vitaliy Didenko, was a photographer; he re-photographed Dziuba’s work on film, and then we printed it. And of the workers I can recall, there were Volodymyr Naida, a young guy, and Volodymyr Kyrychenko. They would visit Nadiia Vitaliivna Surovtsova’s home; they also fervently embraced this movement and participated in the national revival.

I arrived at the camp in the winter of 1973. When a new person arrived, it was an event in the camp. A three-liter jar of tea would immediately be brewed, and a welcoming ceremony would be held. I remember being met by a fairly young man, Petro Vasylovych Ruban. I was very surprised that everyone in the camp already knew I was a mechanical engineer from Uman. They immediately took me to the barbershop, where one of the UPA soldiers was the barber. Then there was this meeting. Of the young prisoners at that time, there were Ihor Kravtsiv, Ivan Hubka, Vasyl Dolishniy, Hryhoriy Makoviichuk, and later, around the summer of 1973, if I’m not mistaken, Vasyl Ovsienko from the Kyiv region arrived and joined our community. (April 12, 1974. – V.O.). And then two more young guys from the Ternopil region came—Petro Vynnychuk and Mykola Slobodian (At the end of November 1973. – V.O.). Of the older ones I remember well, there were members of the Ukrainian underground from the western regions, participants in the armed resistance: Mykhailo Zhurakivsky, Mykola Konchakivsky, Ivan Myron, Roman Semeniuk, Ivan Ilchuk...

V.V. Ovsienko: Dmytro Syniak.

K.I. Matviiuk: Dmytro Syniak. We, Ukrainians, stuck together like that, called ourselves a community. I was very struck by how many Ukrainians there were. We had four “detachments,” there were three barracks. I went into almost every barrack, although it wasn’t allowed and was punishable. But I went in and simply counted by last names—there were “tags” on the beds. In every barrack, more than half were Ukrainian surnames—there were significantly more than half Ilchuks and Semeniuks. There was a large group of Lithuanians. I remember Povilionis Vidmantas, a young guy. There were Armenians, there was a group of Russian monarchists who stood for the restoration of the monarchy. I remember one of their, so to speak, elders from Leningrad, Yevgeny Vagin—he even tried to look like Nicholas II. They even walked with their hands clasped high behind their backs, just like Nicholas II walked. I remember Yevgeny Murashov from that group. And Jews. Of the Jews, I can now recall: Boris Azernikov, Boris Penson, Mikhail Korenblit.

V.V. Ovsienko: Lassal Kaminsky.

K.I. Matviiuk: Yes, I remember Kaminsky too. We had the best relations with the Lithuanians. In general, we tried to gravitate toward all the nationalists. Since the Zionists are also nationalists, we had quite good relations with the Jews. On a daily level, there was an extraordinary camaraderie with everyone, including even the Russian monarchists. I remember going out with Vagin on the so-called “orbit.” When we needed to talk so that the conversation couldn’t be overheard, we would go out on the “orbit,” which meant walking around the perimeter inside the camp. I would walk with Yevgeny Vagin on this “orbit.” In our conversations, I expressed a negative attitude toward the slogan “A single and indivisible Russia,” while he said that “this slogan is deeply revered by us.” Yevgeny Murashov was more frank; he had less education than Vagin, and he told me, meaning that I was a Ukrainian nationalist and he was Russian: “And keep in mind, Kuzma,” he said with that Russian directness, “if you didn’t get away from the Bolsheviks, you certainly won’t get away from us.”

We had good relations, I repeat, with the Jews, but I must note that everything we knew, they also knew from us. But, unfortunately, not everything they knew, we always knew. Perhaps this was a manifestation of a trait inherent in Jews not to be completely sincere, not to open up completely. For example, they, the Jews, already knew that the long-term prisoner, the poet Alexander Alexandrovich Petrov—I think he was the author of that song “Dark is the Night”...

V.V. Ovsienko: Petrov-Agatov.

K.I. Matviiuk: Ah, Petrov-Agatov. So they already knew that he was an informant, that he was giving information, giving quite detailed reports to the authorities inside the camp. They knew this, while I was still buddying up with him like a schoolboy and telling him everything, yet, for some conspiratorial reason, they were in no hurry to tell me.

V.V. Ovsienko: There were also the Moscow democrats there...

K.I. Matviiuk: Among the Russians, there was an even larger group than the monarchists—the Russian democrats. There was Dr. of Technical Sciences Sasha Bolonkin, Candidate of Astronomical Sciences Kronid Lyubarsky, there was the editor of the journal *Veche*, Vladimir Osipov, Sasha Romanov from Saratov, Valery Belokhov also from Saratov. Some of the Russian democrats who arrived gravitated towards the monarchists, while others remained democrats. For example, Kronid Lyubarsky and Alexander Bolonkin remained democrats. Osipov, of course, leaned towards the monarchists, and Sasha Romanov also seemed to be closer to the monarchists.

What else can I say about the camp? It was difficult in terms of daily life. The low-calorie food, the lack of protein, which led to muscular dystrophy. Although there were starches and carbohydrates, and enough bread, it was still mostly carbohydrates. Why was there enough bread? Because there were many people over 60-70 years old, old collaborationist policemen and Banderites. These people already had stomach problems and didn’t eat their full rations, so the bread was left on the tables. So we didn't starve for bread there.

V.V. Ovsienko: But what kind of bread was it—a special bake. It was sour. Remember when the bakery in the zone burned down, they brought us real human bread for a couple of months?

K.I. Matviiuk: There was a lack of protein and a complete vitamin deficiency. The issue was our physical weakening or physical destruction. When Captain Potapov caught me having forged a key to get into the electrical panel room, where I had placed a small box on the windowsill and planted a few onions to get green sprouts, he said, “We’ll catch you and punish you so that you won’t climb in there again.” I told him, “You know, you have an interesting way of thinking. You’re strangling me, and then your hand gets tired of strangling, you let go and say, ‘Don’t breathe.’ It’s in my nature to breathe. So you let go—I breathe; you start strangling me again—I don’t breathe. You are trying to physically destroy me, and I am trying to survive. So what’s the point of this conversation?” He didn’t deny that they wanted to physically destroy us, but he said, “You should have thought about that out there, in freedom.”

So, based on this, as I recall the prisoners, the camp didn't pass without consequences for anyone. For example, that same Sasha Romanov. He had a mental breakdown; he threw himself onto the barbed wire, climbed over one fence, and got into the so-called firing zone, where he could have been shot, and they would have even gotten ten days of leave for it. But, luckily for him, it was a soldier who wasn’t tempted by ten days of leave; he didn’t shoot him. Sasha then ended up in a psychiatric hospital for a while. The same with Murashov. His stomach rotted through; he had a stomach ulcer. Many, many came out of there as invalids. Personally, I was in such a state of exhaustion that while working on a board on a machine during a night shift, I lost the fingers on my left hand.

It’s also interesting how the system worked. The system worked in such a way that it gradually strangles you, and once you get caught in its gears, it’s very hard to get out. My fingers on my left hand were severed. I wrapped my hand in a towel and went to their so-called checkpoint. At night, around one in the morning, the question arose of sending me to the hospital. And that’s when it started. There was no order. Finally, after some time, they found one—all with swearing. They found a detail to take me. They were getting ready to go, getting their cartridges, assault rifles, then—looking for the dogs. Fine, they brought the dogs. It turns out that the guys they found, the ones who were, so to speak, the unlucky ones because they had been playing dominoes or sleeping and now had to take me in the middle of the night—it turns out these dogs didn’t recognize these soldiers and were growling at them; they weren’t used to them. And all this time, blood is dripping and dripping from my hand. At first, I was sitting on a stool, then it became hard to sit on the stool, so I sat on the floor against the wall. Finally, someone comes in and says, “Well, for crying out loud, are they going to find someone or not?” Still no one, the dog isn’t right, this one isn’t right. Then some officer says, “Just take him already, a little longer and there’ll be nothing left to take.” And there was already a pool of blood by my hand. Finally, they took me.

I got off—I don’t know if it was cheaply or not—but I got off with the fingers of my left hand. But after that, I had lighter work. I was in the hospital, after all, where the food was better; maybe that helped me not to get some chronic illness or get into another accident. So, rarely, very rarely, did anyone leave there unharmed, regardless of whether their sentence was long or short.

V.V. Ovsienko: We should talk about the collective actions...

K.I. Matviiuk: No, I’d still like to talk about the prisoners. There was also a fairly large group of policemen who had served the Germans. Our Ukrainian men. There were different kinds, there were decent ones, and there were those who collaborated with the camp administration. There were officers of the ROA—the Russian Liberation Army, Vlasovites, who fought alongside Vlasov. Among them, too, there were quite decent people, and there were not-so-decent ones, to put it mildly.

There was also a large group of Russians who had mostly served in East Germany and had defected to the West. They were somehow caught in West Germany, returned here, and given sentences. There were also so-called Russian or some other spies. They had been Russian intelligence officers, but they had defected, and then they too were caught and returned here. I also remember a man named Kalinin, one of the old Russian supporters of monarchism, an old man who was always praying. I remember an episode where he is praying, paying no attention to anyone, and Lieutenant Colonel Velmakin, the head of the camp regime, walks by. This Mordvin, Velmakin, had a lisp: “What, praying, Kalinin? Ask your god to let you out. Ha-ha-ha,” he laughed. A materialist, you see, what are you praying for, let god release you. Kalinin pays no attention, but in his prayer, he says, “And I also ask You, O God, send death upon the accursed fiend Velmakin.” Velmakin stops laughing and shouts, “Guard, guard, ten days in the punishment cell!” It was a comical scene because the atheist Velmakin, a communist, should have laughed at that too, but he was still afraid that the man would ask God for the “death of the accursed fiend Velmakin.”

Although resistance did not stop there, in the camp. We tried to prepare some documents, to smuggle them out of the zone, looking for ways through relatives who came for visits. There were hunger strikes for various reasons. We observed October 30—Political Prisoner’s Day. There was a hunger strike on that day.

V.V. Ovsienko: December 10—Human Rights Day.

K.I. Matviiuk: December 10. There was a hunger strike in defense of our women, who were imprisoned in a small zone there in Mordovia, in Barashevo, as a sign of solidarity, because they were treated very badly there.

V.V. Ovsienko: There was also January 12.

K.I. Matviiuk: Yes, and January 12—the day of the new repressions in 1972.

I want to add something about my children. All the children were, of course, born after the camp, because they did not allow me to register my marriage with my wife in the camp. My eldest son, Ivan, was born in 1977; he is now finishing his institute studies. My daughter was born in 1978; she is in her fourth year at the university’s law faculty. Her name is Oliana. And my youngest son, Petro, born in 1980, is a first-year student at the Faculty of Engineering of the Agricultural Institute.

V.V. Ovsienko: I remember your mother came to visit you, but your wife, it seems, was never allowed in.

K.I. Matviiuk: No, my wife was never allowed in, not once. They were constantly bargaining with my wife: if she would influence me to repent, she would be allowed visits, and if not, then no. She refused to persuade me to repent, so she was never allowed a visit. All that was left were short visits in the presence of a guard. When the time for a visit approached, every inmate tried not to get a “regime violation” so as not to lose that visit. On September 24, 1974, my wife Sofiia came to the camp for a short visit. According to all camp rules, the administration should have granted it. However, they didn't, completely without reason. They just informed me: “Your wife is there, outside the zone.”

V.V. Ovsienko: You didn’t see Vasyl Stus there, did you? Or Vasyl Lisovyi?...

K.I. Matviiuk: The question caught me off guard, so I didn’t remember right away. Vasyl Lisovyi was first brought to the third camp. The ones I called class “A,” the top league—Vasyl Stus, Viacheslav Chornovil, and Vasyl Lisovyi—they were in the third and seventeenth camps. Those were small zones; they didn't have their own punishment cells, but our 19th did, so this trio spent more time here in the punishment cells and the PKT—a cell-type facility—than in their own zones. So we saw them at least once a week. We always tried to go out to see them and exchange a few words when they were taken to the bathhouse to shave and wash. When I was being released, Vasyl Stus was just leaving the punishment cell for his zone, and we talked the whole time in the “voronok.” He was going to his zone, and I was going to Potma.

V.V. Ovsienko: You see for yourself how much we’ve recalled today, and yet there’s so much we haven’t. There is a need to remember and write all this down. I see you’ve made some notes for yourself now. I think this will become the basis for writing something. There’s less work in the winter, so get to it and write, because it’s not for nothing they say that history, unfortunately, is not always what happened, but what was written down.

K.I. Matviiuk: I have many notes, so to speak, written in the heat of the moment. I had a habit. When I arrived at the camp, I immediately wrote down the testimonies of my witnesses, who said what, and I managed to get it out. Then the diaries I kept after the camp. There is a lot of testimony there from the heat of the moment; they are more detailed.

V.V. Ovsienko: All the more reason and opportunity for you to write.

K.I. Matviiuk: For me, the bright memories of the camp, figuratively speaking, are like this. I feel a grip on my throat—an opponent’s or an executioner’s hand—and then he loosens it, and I feel that he’s not going to fatally choke me. I injure my leg, there’s a fracture in the bone—most likely a fracture, because my leg hurts and is constantly swollen, but I go to work. Captain Seksiasiev, the head of the medical unit, couldn’t find a direct fracture: “You’re healthy.” And that’s it, I go to work. But if there’s a fracture, our Jewish doctors (Korenblit) say that an unnatural joint can form there. And that’s already a damaged leg, and then you remain a cripple. But I keep walking. Then I ask the camp officers: “Let me walk to work on a crutch.” They say, “You want to use crutches? Go ahead.” I remember this as a bright moment. It was good for me because I put a small board on my leg, wrapped my leg to immobilize it where I had the fracture. I walked on a crutch; they allowed me. It was a slight violation of the regime, but they allowed it, so I walked like that. And when I finally got to the hospital and they took an X-ray, the image showed a fracture that had healed. They told me there, “Look how wonderfully the fracture has healed.” An artificial joint had formed, medically speaking. And what if I had been straining the fracture all that time?

I remember another bright moment, when I was under the pressure of the Khmelnytskyi KGB in the late seventies and early eighties. To support my family, I had to have some sort of farm, I had to build some kind of shed. But I couldn’t build a shed with money, because it was impossible to order building materials; they wouldn’t issue them to me. I could go out to the highway where they transport building materials, just stop a truck and buy some; the drivers would deliver it. Everyone did it, one hundred percent, the whole village, but I could be caught as an accomplice in the theft of stone from the quarry and imprisoned. And so I went to my job for a regular meeting with the KGB officer who was handling my case there, in the Khmelnytskyi region. I told him I was building a shed, so I had to build it the way all Soviet people build, otherwise I wouldn't be able to build it. So, would you catch me and imprison me for stealing socialist property? And he sincerely told me to build it peacefully.

V.V. Ovsienko: He gave his sanction.

K.I. Matviiuk: He gave his sanction. That is, steal the stone, like everyone else steals. I looked him in the eye and saw that he was telling me this sincerely, and it was as if the thing that was suffocating me had been lifted from my throat, so I could breathe, and I remember this as a bright glimmer in those times.

V.V. Ovsienko: And for the record: where did you work after your release? You had no work at all for six months, where did you live then?

K.I. Matviiuk: First of all, I was in the Cherkasy prison for two weeks for their “prophylaxis.” Then my investigator, Major Kovtun, came to see me; maybe he was already a colonel by that time. I remember asking him then, “Did Major Pavlenko catch 97 spies in that time?” He asked, “What’s with that number, why 97?” And I said that when I had asked him, “Is this your job—to rummage through other people’s letters?” Major Pavlenko had said, “Oh no, that’s maybe only three percent of my work.” So if he caught me with three percent of his work, it means that over these years he must have caught 97 more like me. He laughed, and then asked what I would do after my release. I said, “Well, what? I was convicted of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, I served my time. Did I serve it? Yes. Am I guilty according to your laws? No, I’m not. I will continue my teaching practice, since I am a lecturer of special disciplines.” So they didn’t let me into Uman; they sent me to the Khmelnytskyi region. Then from the Khmelnytskyi region, I moved to my wife’s place in Oleksandriia and was without work there for six months. But I also took a stand. They really wanted me to go work as a laborer. “We’ll give you an apartment if you go work as a laborer, and then you’ll prove yourself and start working as a lecturer again.” I said, “You know, I studied with state money, the state educated me, I am a mechanical engineer, so please, give me a job in my field.” And I flatly refused to go work as a laborer. They didn't want me to go work as a lecturer. I wrote to the prosecutor’s office in Moscow, I wrote to the newspaper *Pravda*—well, everywhere one could write. To Lukianenko, Lukianenko sent it somewhere further, to Amnesty International—it all went around in circles. So at first, I worked as a designer in a project technology bureau.

V.V. Ovsienko: In which city?

K.I. Matviiuk: That was Oleksandriia. I worked there for a year. In fact, I was a lead designer and really managed a project from start to finish, but I was paid as a first-category designer. That’s discrimination, less money, and a responsible job, but no advancement. I quit that job, especially since my term of house arrest was over. My dream was still to do scientific work, and I moved to the village of Shubkiv in the Rivne region and got a job as a senior research fellow at an agricultural research station in the mechanization department.

V.V. Ovsienko: When was that?

K.I. Matviiuk: That was at the end of 1977 and into 1978. I started doing research there, initially concealing my criminal record. After a while, the director informed me that my file had arrived, meaning the authorities had already found me there. They accused me of concealing my conviction. There was some party congress of theirs, the 26th, or something. They pulled us from our work and sat us in front of a TV to watch the speech of the General Secretary, Brezhnev was speaking. I was reading their own newspaper, either *Izvestia* or *Pravda*—they accused me of great disrespect for the party congress and the General Secretary because I was reading a newspaper during the broadcast of the first day of the congress. Then I said something else—and they fired me from this research job under an article for not corresponding to the position held. But they showed magnanimity and said, we are firing you under this article, but let’s write down that you were not re-elected to the position. I said, “Write what you’re firing me for.” “Oh, is that so!” And they wrote: “In connection with non-compliance with the position held.”

Then I came to the Khmelnytskyi region and got a job in Holoskiv as a mechanic on a farm at a collective farm. At first, everything seemed to be going well. Then the KGB found me there. There was a system. The management treated me normally. But as soon as the KGB came and started questioning the head of the collective farm or the director of the state farm about how Matviiuk was doing, after that, every manager considered it his party duty to make my life miserable at every turn. They thought it was required of them. I even have a thought that by that time, the KGB was no longer demanding that they create such conditions for me, that they poison my life. It was their own initiative; they didn’t know any other way to prove their loyalty to the authorities. The head of the collective farm starts looking for something that’s not right and something that’s wrong. I quit and go to work as a mechanic at a pig-fattening complex. This is now 1979–1980, a complex belonging to the city food trade department. At first, everything goes well, I mix feed for the pigs with a mixer, pump out the manure. The KGB finds me there, they start talking to the director of the city food trade department, start asking how I am, what I’m doing—and unbearable conditions are created there too. They immediately promised an apartment—now there’s no talk of an apartment. There’s no talk of a pay raise either. Instead, the director starts telling me, “You know, you concealed your conviction…” I say that I wasn’t convicted for fraud. He says, “Well, how so? In trade—and a person with a conviction…” I say, “Wait a minute, my conviction is political, what does it have to do with your trade? Right now I’m pumping out pig manure. What offends you?” “Well, you know, it’s still a conviction.” I quit that job and go to work as an engineer at “Puskonaladka” [Commissioning and Adjustment Enterprise]. For a while, I also work successfully, first as a troubleshooter, then I become a foreman, they give me a team of troubleshooters. The KGB authorities come there again, again they start asking questions. The management also considers it their duty not to be accused of some lenient attitude towards me. The management demotes me from foreman and transfers me back to being a regular troubleshooter, again “this is wrong” and “that is wrong.” I leave that job, I go to work as a mechanic, head of a garage at a mechanization school. I also work there for a year...

(The end of the story—a few minutes—was lost. But K. Matviiuk sent a handwritten addendum on 06.16.2006).

Everything repeats: work goes well until representatives of the KGB from Khmelnytskyi start visiting…

In two years, from 1976 to 1978, I had to move (change my place of residence) several times: the village of Ilyashivka in Starokostiantyniv Raion, the city of Oleksandriia in Kirovohrad Oblast, the village of Shubkiv in Rivne Oblast, the village of Samchyky in Starokostiantyniv Raion, and finally, the village of Pyrohivtsi in Khmelnytskyi Raion.

In 1982, I started a job as a club leader at the regional Young Technicians’ Station, and only then did things begin to “brighten up” somewhat. KGB officers also came to the director, but the station director, Oleh Fedorovych Lysenko, did not start demonstrating his loyalty to the regime by persecuting and harassing me. I was placed on an equal footing with other employees. My students won first places in all-Ukrainian competitions, and I was awarded a medal from the VDNKh (Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy). In 1988, I was appointed deputy director of this Young Technicians’ Station.

Around this time (1988), my public work begins. That year, the cultural public organization “Spadshchyna” (Heritage) was created in the city of Khmelnytskyi. We gathered in one of the classrooms of the local institute (the head of “Spadshchyna” was an associate professor of this institute, Hennadiy Oleksandrovych Sirenko), and although not everyone yet dared to say the word “Spadshchyna” out loud (when we met people near the door of “our” classroom, they wouldn’t ask “Did you come for ‘Spadshchyna’?” but would cautiously ask, “Did you come for the 5:30 meeting?”), it was already a breakthrough. We spoke out loud to a wide audience about painful national problems; we took these problems to the general public by giving lectures and holding conferences.

Later, we created the regional Taras Shevchenko Ukrainian Language Society. A debate began about creating the “People’s Movement of Ukraine for Perestroika” (Rukh). Opinions in “Spadshchyna” and the Ukrainian Language Society were divided: the radical group (to which I belonged) was unequivocally for Rukh, while the moderate group was against it, explaining that within the loyal “Spadshchyna” and Ukrainian Language Society, it was possible to work legally under the full power of the CPSU and the KGB, whereas the radical Rukh would be banned and its members arrested. The radical group prevailed, and from these two public organizations, the regional organization of Rukh was eventually created. I was a delegate to the Constituent Congress of the People's Movement of Ukraine for Perestroika (September 8–10, 1989). On the second day of the Constituent Congress (chaired by Dmytro Pavlychko), a heated argument broke out in the Presidium. In the heat of it, D. Pavlychko threw his pen on the table and exclaimed, “I can also just get up and leave right now!” The situation got out of the Presidium’s control. Delegates jumped up from their seats and ran to the stage, shouting and waving their arms. (The delegates from Khmelnytskyi who ran to the stage then later became or are today members of the Verkhovna Rada.) I also had my own position, I also shouted and waved my arms, and rushed to run to the stage. But I noticed that there were already too many people on the stage shouting and waving their arms. I immediately returned to those who had remained in their seats. We all just stood up from our seats and chanted, “Unity! Unity!” Eventually, the noise on the stage subsided, and the congress continued its work.

In 1992, I was elected chairman of the Khmelnytskyi city-raion organization of Rukh. I was also co-chairman of the Khmelnytskyi regional Rukh.

In 1993, with a group of activists, I created the regional organization of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and the Repressed, which I headed for two terms—until 1999.

In 1991, I submitted two detailed proposals (projects) to the regional state administration and to the SBU (Security Service of Ukraine) Administration of Khmelnytskyi Oblast. The first was to revive the traditional rural farmer of the Khmelnytskyi region by providing land for use and financial assistance from the state.

The second was to repurpose the SBU department that dealt with wiretapping and surveillance of citizens to fight organized crime (bribery, racketeering, etc.).

In those days, we Rukh members were accused of only criticizing and not doing anything practical ourselves. So, at the end of each project, I wrote that I was willing to work in these departments to implement what was proposed. They didn’t take me at the SBU, citing my age (50), but as for the agricultural project, in the summer of 1992, a department for the organization and development of peasant (farmer) households was created in the regional department of agriculture, and I was offered to head this department. From the summer of 1992 to the summer of 2001, I organized farming in the Khmelnytskyi region. It was difficult to work—the management personnel of the regional department of agriculture were former communist party officials. I was always an outsider among them, without support. And yet, I managed to make the distribution of financial aid transparent and democratic and to prevent the so-called “white farmers” in the Khmelnytskyi region. This was when regional and district officials registered land in collective farms under their own names, the collective farm workers worked those fields, and the harvest went to these “white farmers.”

From my public work:

2000–2002 – Chairman of the raion organization of the URP “Sobor.”

2002–2006 – Member of the Council of the regional organization of the URP “Sobor.”

February 2004–June 2004 – Head of a mobile experimental group from “Our Ukraine” preparing for the presidential election of Ukraine.

December 2004 – Member of the regional commission for investigating violations in the presidential election.