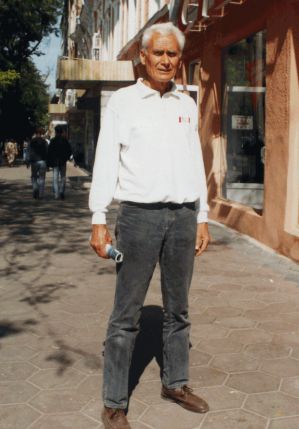

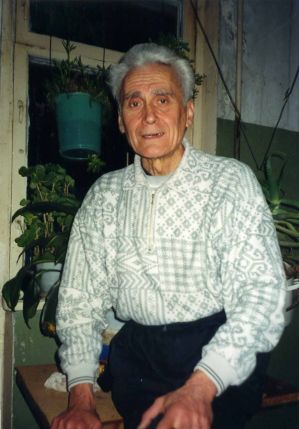

I n t e r v i e w with Leonid Mykolayovych T y m c h u k

Final corrections by L. Tymchuk in July 2006.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: On February 11, 2001, in Odesa, we are speaking with Mr. Leonid Tymchuk. With the participation of Oleksa Riznykiv.

Mr. Leonid, the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group is collecting materials about people who were involved in resisting the Soviet communist regime in various forms. I know from literature and from Mr. Oleksa Riznykiv that you were also an active participant in the resistance movement and have a story to tell. That you are acquainted with Hanna Mykhailenko, with Vasyl Barladianu, with Nina Strokata... So tell us not only about yourself, but also about other people. But first, please provide your biography leading up to how you got involved in the movement.

L.M.Tymchuk: I was born in the city of Ochakiv in 1935, on April 3. My parents were my mother, Yevdokia Fedorivna Zaporozhan, born in 1911, and my father, Mykola Mykhailovych Tymchuk, born in 1907. He was born in the Vinnytsia region, in the town of Medzhybizh. My mother was born on the family homestead of Kopani in the Kherson region—that was their homestead. Now it’s a large village. Later, my parents moved to Mykolaiv, where I lived until 1944. I studied at a German occupation school in Mykolaiv—I went to the first grade there, and then to the second grade under the Soviets. In 1944, we moved to Odesa.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And when did you finish school in Odesa?

L.M.Tymchuk: I didn’t finish it—I quit. I served in the army from 1954 to 1956 in Crimea and in Mykolaiv. After demobilization, I went to work at the Odesa port. At the port, I worked in the port fleet, on tugboats; I worked as a sailor, a motor mechanic, and a boatswain. I was even the secretary of the port fleet’s Komsomol organization.

Even back then, probably starting from my military service, I began to analyze what was happening, what we were all doing—together. They told us we were building socialism, communism, the society of the future, which would exist for millions of years. But I kept running into facts that showed that if we worked like this, if we lived like this, we wouldn’t get very far. I constantly had conflicts on this basis. Because of this, I even left the Komsomol—I stopped paying my dues—and generally withdrew from public work because it was impossible to fight the shortcomings that were obvious to everyone. They always told me, “Why do you only see the dark side and not the good?” And they did terribly stupid things just to show that we were fulfilling the plan, that we were living in a communist way, that we were building a communist society, that we had already built socialism. I said that as I understood that socialism, that communism—we were going in completely the wrong direction.

And it went on from there. Sometimes I read newspapers—I rarely read newspapers, I don’t like to read them, I live independently, I try not to depend on anyone, I always managed my own troubles myself. I got used to listening to the radio. I didn’t even watch TV, because if you watch TV, you can’t do anything else. But if you’re doing something in the kitchen, washing the floor, sweeping, or doing something else, your ears are free, you can listen.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: But weren’t there jammers working against the radio?

L.M.Tymchuk: And I worked against the jammers.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: How? That’s interesting.

L.M.Tymchuk: Well—a military radio station, a military radio receiver. A spy radio receiver, the R-310. (The R-310 radio receiver, with a panoramic device, has an antenna input switch that allows for connecting two types of directional antennas, which, depending on the quality of their construction, reduce interference.—L.T.).

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Ah, so you worked like a spy?

L.M.Tymchuk: On the screen of the R-310, with its panoramic device, you could observe the state of the airwaves and also determine which station was being jammed more or less, and on what frequency, and how they were jamming it. This radio station was once confiscated from me—they tried to confiscate it, but I fought to get it back. When they seized all these things during a search related to the arrest of Nina Antonivna Strokata, I said this: “Either take me with them, or give me back my things. We can only exist together.” “Where did you get it?” “I bought it.”

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Nina Strokata was arrested on December 6, 1971.

L.M.Tymchuk: I gave the search protocols to Zaiats in Lviv.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: That’s to Yuriy Zaitsev. And when did you start listening to the radio?

L.M.Tymchuk: I started listening to the radio as soon as I got a receiver. That was around 1959. It was a Soviet-made consumer receiver, only a 25-meter band, a “Vostok-57”—it didn’t satisfy me.

But to be consistent, I have to tell everything in order. I also became passionate about music. I started looking for like-minded people and found them—there was a Viktor Mykhailovych Kryukov (he has since passed away) and his wife, Kateryna. We recorded music. And music was also jammed. Kateryna Vasylivna is still alive. She’s retired and has a son, Ihor—he should also be mentioned. I don’t remember his address right now, I’d have to look for it, and I have very little time now.

Well, we recorded music, exchanged recordings, and it got to the point where I once wrote to the BBC to ask them to send me—and I meant for my friends too—the rules on how to dance the “Cha-cha-cha.” I wrote a completely neutral, completely apolitical letter—nothing, no reply, no delivery confirmation—none of it came. But that’s where it all started. We listened, trying to somehow establish contact with the BBC. The letters didn’t get through. But one day, on the air, we heard Larisa Bogoraz’s appeal to the world community about the trial of Ginzburg, Galanskov, Lashkova, and Dobrovolsky. This appeal was broadcast to the whole world. We gathered and started talking about it. We saw that this was an event unlike any other. We decided then that this was the beginning of a very major event.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And then, in connection with the occupation of Czechoslovakia, there was the “demonstration of the seven” in Moscow’s Red Square on August 25, 1968...

L.M.Tymchuk: Yes, yes, yes, that was in 1968. During the Czechoslovak events, we were already dissidents. We thought and wondered. I said, “Now all honest people will probably support this appeal.” And indeed it was so: statements and protests poured in from all over the world against this lawlessness. We waited and waited, listening every day, recording the broadcasts on a tape recorder—we recorded them several times because one time the beginning would be jammed, another time the end. Kryukov did this—he had a good Blaupunkt receiver, a German one; it had shortwave bands—13 meters, 16, and others. We would record and then transcribe it onto paper. It was very tedious work...

V.V.Ovsiyenko: By hand, right?

L.M.Tymchuk: By hand. A typewriter back then was a luxury. Not like now—computers and all that. Back then, everything was done by hand. We gave it to friends to read. And we kept waiting for someone from Odesa to support this appeal. But we waited in vain. And then we decided—I have this principle: if something needs to be done and no one is doing it, then I try to do it. So that’s what I said: “If no one in Odesa could be found, then we must do it.” First Kryukov and Kateryna wrote, and about a month later I wrote too—a protest to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, to the Politburo of the Central Committee. A very sharp protest against the trial of Ginzburg, Galanskov, Lashkova, and Dobrovolsky. I sent it—no answer.

Then we gathered again to consult on what was happening. They were supposed to give some kind of answer—they gave nothing. They were violating their own laws. What were we to do? I said we needed to call Larisa Bogoraz; we had sent her copies, but they hadn't arrived either. So I went to the main post office, dialed the number—back then you had to book a call—I booked Moscow, dialed the number, and Larisa Bogoraz was on the line.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And where did you get her phone number?

L.M.Tymchuk: It was broadcast on the radio. They broadcast her address on the radio too—where else would I have known it from? We scraped that address and phone number out from under the jamming. I told her—and I'll switch to Russian now—“This is your Odesa correspondent, Tymchuk, speaking.” Well, a correspondent in the sense that I had written a letter to her. “I wrote, and Kryukov and Kateryna wrote. Have you received anything?” “Nothing,” she said, “we haven't received anything from Odesa.” Aha! So that’s the dirty game they’re playing? That means they’re afraid of us? “We’ll deliver these letters to you with a traveler,” I told her. And that was that. We would bring them ourselves if the Soviet mail couldn’t do it. And that’s what we did.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And who took them?

L.M.Tymchuk: Kryukov and his wife took them. I was just at her place recently—I told her to write down everything, just how it was. I even took that protest they wrote from her and made a photocopy. It’s a document. I even made a photocopy of the delivery confirmations. I have it all now. It’s a document about the beginning. I don’t remember anymore if the three of us went to make the call or not. We let them know when we were planning to do it. Kryukov took a vacation and called to say that he and his wife would go to Moscow on May 1, or earlier—I don’t remember when. The year was probably 1967. I’ll get those papers now and even give you a photocopy. You can make another photocopy from the photocopy—it’s very convenient now.

Well, we got ready. Viktor took a vacation and said, “We’re going.” I said, “But we talked to Larisa on the phone.”

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And they listen in...

L.M.Tymchuk: “And her phone,” I said, “is bugged. We have to make sure you get there. Don’t go when you said you would.” And he went earlier. He went and got to Larisa without any problems. They walked around Moscow, Larisa showed them around, introduced them to Moscow dissidents—Anatoly Marchenko, and others. Everyone there was surprised, such a heroic deed—they came, they brought it, without any obstacles. Well, we explained to them that we had wrapped the KGB agents around our finger from the very beginning. And so it continued: I always managed to somehow outsmart and outwit them. Even when they decided to imprison me at any cost, at the cost of violating Soviet laws, and pinned a hooliganism charge on me—even then I managed to fool them.

It ended like this. Kateryna and Viktor Kryukov collected *samizdat* in Moscow. They were given what was available. There was little *samizdat* then, it was just beginning to emerge. And when they arrived in Odesa, they were arrested.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: After their return?

L.M.Tymchuk: Still on the train, even.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And what exactly were they carrying?

L.M.Tymchuk: I don’t remember. It was confiscated, everything was taken. They were framed for stealing some “Bologna” raincoats from some hotel, some valuable papers. The *samizdat* was under the lining of Kateryna’s bag. They ripped open the lining and took it. The Kryukovs said, “But these aren’t valuable papers, these aren’t Bologna raincoats—what are you doing, you’re looking for something completely different! If you’re looking for raincoats, take the raincoats.” But they took the *samizdat*, took the Kryukovs to the KGB, held them there late into the night, cursed them as much as they could, and told them not to maintain any contact with me—not to visit and not even to greet me if they saw me. But they did the opposite—as soon as they were released, they came to my place at night. Kateryna shouted from the yard through the window: “They searched us, they detained us, they just let us go! They took everything, and we were carrying *samizdat*.”

O.S.Riznykiv: And where were you living then?

L.M.Tymchuk: I was living on Industrialna Street then, Mykhailivska Street, number 44, apartment 4. And the Kryukovs lived on Zankovetska Street. They told me what had happened.

And then there was Serhiy Tytarchuk, a worker from the regional party committee in the Komsomol sector. He was friends with Kryukov because of their shared interest in jazz. They exchanged recordings. This Tytarchuk was a very interesting fellow; he and Kryukov would always greet each other when, of course, there were no witnesses: “Heil!” “Sieg heil!”

V.V.Ovsiyenko: That was a regional committee official?

L.M.Tymchuk: And this regional committee official told us that there was a meeting at the regional committee and the conversation went like this: “What principled people—they didn’t even take anything to speculate with! If only they had taken some things for speculation, we could have imprisoned them. But they—it’s amazing!—didn’t bring a single piece of clothing from Moscow, only that *samizdat*!” That was the conversation at the regional committee. Even at that level, there were like-minded people back then.

That’s how it started. Our letters were broadcast on the radio. They started taking measures against us. They began to summon Kryukov and me for “chats.” They organized a meeting at work, but I ignored it. I just walked out when all the party officials and KGB agents showed up. I had invited a friend of mine, Ostapenko, but they said he was an outsider and should leave. I said, “And who invited these people? I don’t know them either.” “They’re our people.” “And this is my person, and if he leaves, I’m leaving the meeting too.” They told Ostapenko, “Leave, leave the meeting.” He left, and I left after him. They discussed my letter—they didn’t read the whole thing, just pulled out certain phrases. And then they said, “It’s very bad that you left the meeting. We’ve drawn up a resolution saying what you wrote was wrong.” And I said, “That’s your opinion, and I have a different one. I stand by my convictions. Your convictions are your convictions, and mine are mine. They are different things, and I’m sticking to my position.” “Well, you watch out, or something might happen!” “Well, if it happens, it happens.”

We started to act. Kryukov said that someone in Odesa must support us. At that time, no one had yet. He lost heart, as they say, that no one supported us, that we were left alone. What were we going to do, what needed to be done? And I said that Odesa has a million residents. We talked to so many people, and they shared our opinion. So someone has to support us, right? We need to look for like-minded people.

And I started looking for like-minded people.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And how did you look for them? That’s interesting.

L.M.Tymchuk: Among my acquaintances. I had a large circle of acquaintances—they were music lovers, radio amateurs. I went through this large circle. But I didn’t have to go far, because my neighbor lived on Mykhailivska, in building 44—Zhora Martianov, he now works as a forensic medical expert. (Heorhiy Andriyovych Martianov died in 2005.—L.T.). I told him about my situation. He said that there were people who were interested in *samizdat*, and he introduced me to Sudakov—Viktor Viktorovych Sudakov, there was such a person in Odesa, he now lives in Germany. We met with Sudakov and his circle. There were like-minded people there too, but no one dared to express it to the whole world and throw their convictions in the face of the Politburo and the Central Committee. They were interested in *samizdat*, they read everything, but nothing more. Sudakov was a correspondence student at Moscow University in the journalism department. He would go to Moscow to the university to take exams, and at the same time, he brought *samizdat* from Moscow and our letters to Moscow.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: What did he bring at that time? Do you recall what works were circulating then? Maybe Sakharov’s *Reflections on Progress*?

L.M.Tymchuk: That was later. He brought a lot of *samizdat* and distributed it within his circle. But no one dared to join us in the sense of openly protesting against Soviet arbitrariness, against censorship. We were against censorship, for freedom of the press, for freedom of speech, and so on. They didn't let us express ourselves then.

Some time passed, and the circle began to widen. Sudakov continued his studies at Moscow University and was a kind of messenger, a courier. After a while, he introduced me to Anatoliy Mykolayovych Katchuk and Oleksiy Tykhomolov. They were also people who were interested in *samizdat*—they shared our democratic views, but nothing more.

After some time, Tykhomolov came to me and with a mysterious expression on his face, whispered that there were people who were interested in *samizdat*—a whole group. “Well, who are they, what is it?” “I’ll arrange a meeting and introduce you to them. They need to somehow get in touch with Moscow—they’re business-like guys.” We agreed and after a while, Tykhomolov did indeed arrange a meeting for me with Vyacheslav Igrunov and Oleksandr Rykov. We met very conspiratorially, in some park, I don’t even remember where now. Vyacheslav Igrunov and Oleksandr Rykov came to the meeting. They were indeed interested in *samizdat*. They had no connection to Moscow. They wanted to meet Moscow democrats. I said I would arrange it—it’s very simple. And indeed, I arranged an introduction for them. I wrote a letter, gave it to them for Larisa Bogoraz, one of them went—I think Igrunov went to Moscow, and they too began to bring *samizdat*.

Igrunov was then a student at the Institute of National Economy—he was studying at the Faculty of Economics. (He now lives in Odesa.—L.T.). He had a very ascetic, emaciated look, and so did Rykov. He gave the impression of a person who devotes all his energy to his convictions, which at that time was *samizdat*. I asked them, “Are you ready to write some kind of protest, to send it to Moscow?” “No, we're working now, our guys are working, doing scientific research—we need to finish it, and then we'll do something. When we finish, we'll publish it.” To this day, I have not become acquainted with their works. But they regularly brought *samizdat*. Rykov was more interested in non-criminal, so to speak, *samizdat*—philosophy, psychology, yoga, karate. He made money on it. Igrunov was interested in political *samizdat*.

They managed to organize the duplication of *samizdat* in Odesa. They duplicated it by photo-process—a Xerox machine was then only available at enterprises, and even then under close supervision, so you couldn’t get near it, but they managed to do it on a Xerox as well.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: There was a machine then called “Era.”

L.M.Tymchuk: Yes, there was an “Era.” Rykov, where he worked, used this machine. But of course, that was done for money, and he earned money on non-criminal, philosophical *samizdat*. That’s how this *samizdat* existed.

I inquired how Igrunov's circle came to be. They had studied together in school. Their homeroom teacher was Isidor Moiseevich Goldenberg. Isidor Moiseevich Goldenberg organized an underground circle for studying Marxism-Leninism—this was under Soviet rule, strangely enough. That circle was attended by Rykov, Igrunov, and a few other guys—there was a Synilov group, a *samizdat* group. It probably didn't include many people, I only remember one... Oh, I've already forgotten the name. Well, fine, I'll remember it later. (The real scientific work was done single-handedly by Eduard Vasylovych Petrakovsky. He read all of Lenin's works and the stenographic reports of the congresses of the VKP(b) and the CPSU. He drew conclusions, but when the searches began at our places, he burned everything.—L.T.) I'm writing, trying to write all this down, to set it out in written form.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And you’re right to do so.

L.M.Tymchuk: But there isn't enough time, so I have to do it like this.

Goldenberg led a circle for the study of Marxism-Leninism. While working as a school teacher, he had a side job at a factory of folk art crafts. They produced wooden bracelets, medallions, pendants—things like that. Igrunov worked there with Isidor Moiseevich Goldenberg, and Rykov also worked there part-time. Goldenberg allocated 10 rubles a month to Igrunov for *samizdat*. As much as he could. But Igrunov was dissatisfied with this sum and said that they weren't helping us, they weren't helping us enough—Isidor Moiseevich makes big money from this workshop, and he only gives us 10 rubles a month. After a while, Igrunov and Tykhomolov, who worked there, staged a coup in the workshop.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Well, I'll be...

L.M.Tymchuk: This workshop, by the way, was organized by Avram Shifrin with the artist Alik Altman. When leaving for Israel, he handed this workshop over to Isidor Moiseevich Goldenberg. (Shifrin maintained contact with Valeriy Semenyuk—one of the workshop's employees—for a long time after his departure. Semenyuk is Ukrainian. He now lives in Ovidiopol.—L.T.). Subsequently, Igrunov and Tykhomolov accused Goldenberg of misappropriating money and took the workshop from him. Isidor Moiseevich left the workshop. What happened there—I didn't analyze it, I didn't have access to those documents, nor the time to analyze it, to be interested in it, but that's how it was.

And so Igrunov came to rule that workshop. Subsequently, the workshop's affairs worsened. I helped as much as I could, but Igrunov, being a student of the economics faculty, was fascinated by the American economist Taylor and decided to introduce the Taylor system in this workshop. On that, he suffered a collapse. The workshop workers rebelled, the workshop fell apart. Igrunov was accused of misappropriating money and buying half a house on Dubova Street with that money.

Later, I met Nina Antonivna Strokata. During his first visits to Larisa Bogoraz, Sudakov had mentioned that there was a lonely woman in Odesa, no one was helping her, and that she needed help, that some kind of circle should be created so she wouldn't be so lonely in Odesa. This was Karavansky's wife. We didn't know anything about Karavansky back then. Larisa Bogoraz gave us Nina Antonivna's address and somehow we visited her and got acquainted.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Can you recall approximately when that was?

L.M.Tymchuk: It was probably during the Czechoslovak events of 1968. Later, I introduced all my acquaintances to Nina Antonivna—Kryukov, his wife, Igrunov—everyone who wanted to meet her.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And how did she receive you?

L.M.Tymchuk: She received us very cautiously, uncertainly—she simply couldn't believe that such a thing could happen, that people would visit her so fearlessly. From time to time she would say, “Watch out, these visits won’t end well for you.” And so it happened.

We began to exchange *samizdat* with Nina Antonivna. Then she introduced me to people from Lviv, to Vyacheslav Chornovil, to Iryna Kalynets.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: What, they came here?

L.M.Tymchuk: They came, of course. With Stefania Hulyk, with her husband.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: So that must have been Chornovil visiting after his first imprisonment, around 1969?

L.M.Tymchuk: Yes, yes. He came here, we met. Igrunov met with him too, but Igrunov had imperialist views, even pro-Soviet ones. This was his constant refrain: “The Soviet government isn’t so bad, if only it could rise economically, everything would be fine, but somehow they can’t get the economy right, and they won’t let us help them.”

Then came Nina Antonivna's arrest.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: She was arrested on December 6, 1971.

L.M.Tymchuk: Before her arrest, she introduced me to some people from Kyiv.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Who were they from Kyiv?

L.M.Tymchuk: My father was living in Kyiv at the time. I would visit my father and I met Oksana Meshko, and Svitlychnyi. Nina Antonivna gave me the addresses, so I went and got acquainted. I, of course, introduced the people from Lviv to the Odesans. But the Odesa group—that was Igrunov's circle, which had managed to organize the duplication of *samizdat*. The main people duplicating this *samizdat* were Valentyna Mykhailivna Prokopenko, the head of the rope factory's club, and Liudmyla Karabanchuk. There was a photo lab there. They duplicated the *samizdat* in that photo lab.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Did they not use typewriters?

L.M.Tymchuk: They used them when it was difficult to make photocopies from a copy—then they retyped it.

Immediately after Strokata’s arrest, my place was searched in connection with it. Then, on the initiative of Vyacheslav Chornovil, the Public Committee for the Defense of Nina Strokata-Karavanska was created, which also included Iryna Kalynets, Vasyl Stus, Petro Yakir, and myself. It was the first open human rights organization in Ukraine. But by early 1972, Chornovil, Kalynets, and Stus were arrested. The Committee only managed to issue two documents—a statement on the creation of the Committee and a bulletin titled “Who is N. A. Strokata (Karavanska).” That was the first search at my place. They took my R-318 radio station and some papers. I don’t even remember what it was or how it happened—I need to sit down and recall it without rushing. Nina Antonivna felt that the arrest was coming, so she decided to help Yurko Shukhevych. How? By exchanging her apartment in Odesa for one in Nalchik, to improve his living conditions, so he would have a place to live. She barely managed to do it. She was moving her things to Nalchik, and I was helping her. It turned out that at the time of the arrest, no one was left—they had chased everyone out of Odesa. They intimidated—well, not intimidated, because it was impossible to intimidate those girls—but they did everything to make sure Maria Ovdiyenko was not in Odesa, to make her leave Odesa. And she had been helping Nina Antonivna until the very end.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: I know Maria Ovdiyenko.

L.M.Tymchuk: I misspoke when I said they intimidated her—they pulled the rug out from under this girl, and she went to Kyiv for a while. I had to take over this matter and be Nina Antonivna’s authorized representative, that is, to take care of her property, which was still in the Odesa apartment, and send it to Nalchik. She was arrested, they searched the place here, while we were packing her things. It was Maria Ovdiyenko and her husband (they weren't married yet) Dmytro Obukh. At that time, the KGB agents already knew that putting pressure on me was pointless—that pressure only embittered me and inspired me to further action. I did my job, brought her parcels, arranged for a lawyer. And I continued to sign protests.

One day, Hanna Vasylivna Mykhailenko visited me. She was looking for a way to contact Nina Antonivna, looking for connections, and she came to me. That’s how Hanna Vasylivna and I met—she came herself and said that there was another teacher in Odesa—Hanna Viktorivna Holumbiyevska, who was being persecuted at school for telling her students about Solzhenitsyn.

Later it turned out that Holumbiyevska lived, as the crow flies, about 150 meters from me, on Melnychna Street, number 8. Holumbiyevska herself came to my place one day—she somehow found out my address and came, we got acquainted. She told me about her troubles, about how the school administration was harassing her for her behavior. Holumbiyevska was the first, after me, Kryukov and his wife Kateryna, to start signing and writing protests. She was the first person. It’s impossible to even say who was first. Hanna Vasylivna—she had no way of knowing how or where to send her protests. So the two of them began to write and sign joint protests. That's how our circle expanded.

Hanna Viktorivna worked at a school. She had students who shared our views. These were Zina Varga, Vasya Varga, and Tanya Rybnikova, who now works at the Odesa Literary Museum. She could also be called a dissident because she signed some protests. I don’t remember what she signed anymore. Zina and her husband, Vasyl Varga, also signed, so the circle expanded.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: So they were no longer schoolchildren, they were older?

L.M.Tymchuk: They were no longer schoolchildren. Zina was probably a student already.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: They were Holumbiyevska's students?

L.M.Tymchuk: Yes. Then Hanna Vasylivna introduced all of us to the Siryis—Leonid and Valentyna—and his family. That's when the protest writing began. Then there was the trial of Igrunov.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Under which article was he tried?

L.M.Tymchuk: He was tried under Article 187-prime, I think.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Was he given three years?

L.M.Tymchuk: He was sent to a psychiatric hospital, but his sentence was very lenient—after two years... He served his time here, in Odesa, in a psychiatric hospital; you could visit him freely. After a while, he was released.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: So it was the court that sent him there, right?

L.M.Tymchuk: The court sent him.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Do you remember when that was?

L.M.Tymchuk: I don't remember. It's recorded in the *Chronicle of Current Events*.

I had known for a long time that there was listening equipment installed on the wall that faced the factory. After Igrunov's arrest, I analyzed some conversations at the KGB and came to the conclusion that they were eavesdropping, and that Igrunov had been arrested using materials from the eavesdropping. He wasn't arrested on the basis of these materials, but the investigation was conducted using them. They quoted our statements verbatim, not even trying to hide that they knew what we were talking about. In this way, they tried to demoralize us—that there were informers in our circle. I said, “I don't give a damn who's an informer and who isn't. Invite everyone. I'm not Jesus Christ, nobody is going to sell me out, nobody will give 30 pieces of silver for me. Let them sell, let them buy.” That's the kind of thing I came up with then. (I also used to say this: Jesus Christ knew which of His disciples would betray Him, but He didn't cast Judas out. Judas had to fulfill his mission!—L.T.).

V.V.Ovsiyenko: An interesting position.

L.M.Tymchuk: I said we’ll talk anyway, but we need to talk in such a way that they don't catch us distributing *samizdat*. So that it wouldn't be heard—we'd write some phrases on paper. I understood that the investigation was using eavesdropping, and I constantly urged the group to censor their conversations. Write on paper—there were devices back then that you could write on many times. You'd lift the film like this—and it would be erased.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: In Moscow, this device was called a “Russian-Russian phrasebook.”

L.M.Tymchuk: Yes, yes, yes. But the group didn't react, especially Holumbiyevska—she was reckless, she'd say, “What, am I going to tie my own tongue—what to say, what not to say? Maybe no one is listening at all.” Then I decided to prove that they were listening. I went up and broke their equipment, took it. They conducted a search at my place, to which I managed to invite Holumbiyevska. They caught me on the street, and I threw a small stone at her window. I knew they were going to search my place, so when they were taking me home, I threw a stone at her window—she looked out, and I said, “Come over to my place for a search, you can be a witness.”

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Interesting!

L.M.Tymchuk: They found all their equipment, confiscated it, and for that, they caught me on the street twice and accused me of hooliganism.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And when was that search, do you recall?

L.M.Tymchuk: You'd have to look at the protocols. I'll write all this down in detail—I have the summonses, everything.

What else can I tell you?

V.V.Ovsiyenko: What happened in connection with this search? They didn't open a case against you?

L.M.Tymchuk: There were no grounds to open a case. I broke and took the equipment that was on the wall of my apartment. But to open a criminal case for the theft of this equipment, someone had to file a lawsuit, someone had to file a claim with the court—the owner of this property, and they said, “This is a civil defense installation, it belongs to the civil defense.” I said, “If so, then let the civil defense open a criminal case against me—or whoever the owner is, from whom I stole it. I'm not hiding—I took it.” When they came back to install the equipment again, they didn't yet know I had done it, because the dog didn't pick up the scent. I climbed onto the roof of my apartment building via a tree and did everything from the tree—there was a tree next to the wall and boxes with some machine tools. I did everything from that box, took it, and climbed back. Only my tourist axe fell, I didn't pick it up. They decided that someone from the factory had done it because I had entered the factory territory. It was factory territory.

A day or two later, they came to install it. I was lying down, already resting. I hear them fiddling with the wall. I climbed onto the roof, looked—it was dark—a car was parked there, guys were working, chiseling the wall. One of them noticed me looking and said, “There’s a man on the roof!” And the others: “What are you doing up there?” And I answered them, “What are *you* doing down there—that’s what’s interesting. Get out of here,” I said, “and take your business with you!” “You’re bothering us!” I said, “You’re bothering my life! Get out of here with your stuff!” And I left. They stood there until morning, not knowing what to do—whether to continue or stop.

And I disappeared from home for a couple of days; they were looking for me, hunting for me. Grazhdan shouted when they caught me, “I haven't slept for two nights because of you!”

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Grazhdan—who is that?

L.M.Tymchuk: Yuriy Stepanovych, an investigator, a senior lieutenant of the KGB. He was the most upset. And Alekseyev—there was a Captain Alekseyev, Oleksandr Serhiyovych—he kept asking in KGB circles, “Well, how did he find out that he had listening equipment installed?” And someone later told me—a person told me, I won't name them now. It was one of their employees, by the way, who told me. It's still not safe—to name this person. I don't know where he is now or how he is, but these guys are very diligent about getting rid of their own people like that—even now. Now they have their own business, their own circle, their own program, and maybe he is still among these people. I won't name him. But there was a whole meeting—I know this for a fact, that Alekseyev asked exactly that: “How could he have found out?” This was in March—when I dismantled it.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: What year?

L.M.Tymchuk: Strokata was already gone, Igrunov was already in prison.

They were waiting for me there. How did they catch me? I was already walking home at night. I look—there’s a guard at my gate. I decided to go into the neighboring building, number 46, into the yard, and climb over the wall into my own yard. As I was climbing over, I saw a person on the factory roof with a night vision device—he was watching the yard. Aha! Well, for me, as they say, there was no turning back, so I went to my house and they caught me right by the house. That's what happened.

And then there was a search—as I already said—I threw a stone at Holumbiyevska’s window. That’s when the search was. I took down that equipment on March 9, I remember that for sure, because—the 9th or 10th?—because I planned my actions so that it would be more convenient for me to do it. There’s security at the factory, of course. I decided to go there after the holiday, when everyone was tired. I thought that would be the quietest time, the most advantageous time for this business—I guessed it exactly right.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: It’s interesting, what kind of equipment was it, what was it like?

L.M.Tymchuk: It was filled with a compound, several blocks. A regular consumer microphone, wrapped in electrical tape, and a lot of “Mars” type power batteries—I pulled them out, left them there, I wasn’t interested in them anymore. So I took it. I didn’t even get a good look at it. But it was very primitive, homemade equipment, not from abroad. Probably their local KGB craftsmen made these things. And it was connected to the telephone network, so I had seen the wire for a long time—it went across the road to building 33. And in building 33, there used to be a district MGB department. So after the district MGB departments were liquidated, something remained there, but without a sign. I saw the wire going there and realized that their people lived there. And then I took a closer look at this building and saw that they were always watching me from the balcony—a woman sat there. Working from home like that, without interruption.

O.Riznykiv: A homeworker! (Laughs).

L.M.Tymchuk: A stay-at-home informer. I already knew: when she was sitting and watching, I was under surveillance. I figured out that I was being watched, that they would be following me. Well, so she watched. I would leave the house—and our buildings are opposite each other, so the distance isn't great—she's sitting on the balcony, knitting or reading something. And it's like this: a glance at the book, a glance at the gate, a glance at the book, a glance at the gate. I'd come out, she'd see which way I went, and she'd go into the room. That's how I knew when I was being watched and when I wasn't.

Well, what else can I tell you?

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Were you doing anything at that time, was *samizdat* still being produced? The 70s were when the repression intensified.

L.M.Tymchuk: There was *samizdat*. Igrunov was arrested, but he didn't have any *samizdat* on him anymore. His system was set up like this: the person who duplicated the *samizdat*—Valentyna Prokopenko and Luda Karabanchuk did the duplicating, she was a student, a young woman, the duplicating depended on them—the person who printed it didn't keep anything: print and pass it on, print and pass it on—they didn't accumulate the *samizdat*. There was a librarian who accumulated the *samizdat*. At that time, the librarian was Yuriy Serhiyovych Horodentsev, he now works as a priest at the St. Demetrius Church. And then he handed over this library to Butov—there was a Petro Butov. The librarian didn't distribute the *samizdat* literature, he only gave it to those who carried it. There were people who would come to him and distribute it. They also didn't keep much on them. *Samizdat* was confiscated in Odesa time and again. We even had a standard, well-rehearsed answer: “Where did you get it?” “I bought it at Starokinnyi.” Bought at the Starokinnyi market—books were sold there. You could buy anything there. After several such confiscations and such answers, they started chasing all the booksellers from Starokinnyi.

Then Petro Butov took over the library.

After some time, in the fall, they caught me on the street for the first time, took me to the police station and wrote down that I had been hooliganizing, harassing girls. The court didn't dare to prosecute me for hooliganism then, because I had never had any hooliganistic acts—it wasn't recorded anywhere.

As soon as I got out—three days later they grabbed me again and put me in for 15 days. Three women found me then. They were Hanna Viktorivna Holumbiyevska, Hanna Vasylivna Mykhailenko, and Rozalia Mendelivna Barenboim, a math teacher, who later left for Israel. But the very first to find me was Hanna Vasylivna Mykhailenko. She found me and even showed me through the small window that she knew where I was.

Then a very interesting event took place: just as they grabbed me and took me to the detention center—not the pre-trial detention center, but the one on Uspenska, what's that cell called—a temporary detention cell?

V.V.Ovsiyenko: KPU. In Russian it’s KPZ.

L.M.Tymchuk: KPZ. Just as they put me there—that storm hit, the one that broke everything here—broke trees, tore down wires. The city was without water, without electricity, and I was sitting there in the KPU—watching through the window. It was already the fifth day—they came for me. They open the door: “Tymchuk!” I say to the guys, “See you later,” and they say, “What see you later—you’re going home.” “Well, I'm baffled as to why I'm going home.” And it turns out, those three women—during that storm, in the sleet, on the ice, without any public transport—the public transport in Odesa wasn't working—they went to the prosecutor's offices, they went everywhere, looking for me and filing protests.

I got out—I didn't recognize the city, everything was so iced over. But one detail was very positive, gratifying: all the jammer antennas were broken, and you could listen to any radio station you wanted. Nothing was jammed, there was no way to do it. Even the small masts were bent. The big one was intact, but the antennas stretched to it, and they were torn off. And the small metal masts were bent. That was some event.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: What year was that storm?

L.M.Tymchuk: I can't even determine that now... They released me into the custody of those women—they achieved that. And literally on New Year's Eve, I attended Hanna Viktorivna Holumbiyevska's New Year's dinner. That's when the protests began. As soon as I got out, I called the Moscow correspondent of the BBC about my troubles, but they didn't react at all, nothing was broadcast on the air. I sent a protest telegram to the Politburo of the Central Committee, asking either to be let out of the Soviet Union to some country where democrats are not persecuted, or for this persecution to stop. People started to protest my persecution. Then Vasyl Barladianu joined our group—we met him at this time—and many other people I met then. There was a period when friends escorted me around the city so that they wouldn't pull the same stunt on me as they had done twice before. This went on for a very long time. Then the court sentenced me to a year of forced labor and I've already forgotten what percentage of my salary. (I commented on this event at the time: paying alimony to the KGB.—L.T.)

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Twenty, I think?

L.M.Tymchuk: Twenty-five. I worked at the port, and my friends would walk me to and from work.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And they didn't try to fire you from your job?

L.M.Tymchuk: There were sharp conversations at work. Some people spoke to me harshly, but I paid no attention. The majority quietly sympathized with me. (They only promised to fire me now, in 2006, for a conflict with the administrative-trade union alliance of “Infoksvodokanal.” They promised to create appropriate conditions for me and Borys Vasylyovych Virolyubov. So the Soviet government died—long live the Soviet government in the form of “Infoksvodokanal.” A kind of capitalism with a communist face or buttocks—it makes no difference. I will send you a photocopy of the case. The case is very easy to refute even after such a long time. It’s very interesting why our highly respected government doesn’t deal with these issues? I wonder what fate befell the organizers of this case? As soon as we drive this internal occupier out of Odesa, I will get on it. There is a connection between these cases, although weak, it probably exists.—L.T.).

It is imperative to tell how this persecution ended. People got tired of escorting me, and I got tired of it. It’s worse than arrest: when I need to go somewhere, I have to ask someone to go with me. What am I—a small child? Or am I such a coward? And one day I sat down and decided: I must deal with this myself. I need to do something and not torture people, because it’s very inconvenient for them. I dismissed the guards: that’s it, I’ll deal with them myself. For a while, I walked alone, alone, alone. I knew they would be watching me. And I determined when I would have a “tail” like this: at work, I worked on a tugboat. The KGB agents had to know when I was at work and when I was leaving work, when to follow me, and when not to follow and could rest. When I’m at work—there’s no need to follow me, they can remove the “tail,” let it rest—so they decided. And they had to find out on the tugboat, on the vessel. To go around and ask when I’m working—that was impossible for them. The communication with the vessel was from the dispatcher’s office. He still commands the tugboats, which one to send where. So the dispatcher would sometimes ask when Tymchuk was on watch. I correlated this with the “tail”—when they ask, I have a tail. That’s good—I know when they’ll be watching me. There were guys who would tell me that they had been asking when I would be on watch.

Sometimes I even did a trick like this. They ask when I'm on watch. And I'm by the radio station and I answer: “Tomorrow.” (Laughs). I messed with them wherever I could. I also developed another technique. I was interested in mathematics, I got acquainted with the works—there were authors like Smolyan and Gnatepa (the second surname is illegible), they wrote works like “The Algebra of Conflict” and “Conflicting Structures.” They were trying to mathematize shamanic practice. What did shamans do? They threw stones. And in mathematics, randomness is very well exploited—there’s a method called Monte Carlo, a very good, fruitful method. I decided to adopt this technique. To put it in the words of Carlos Castaneda (and Carlos Castaneda’s work came out in *samizdat* then, he’s the author of the mystical “Teachings of Don Juan”), a warrior must be inaccessible. A warrior must make himself inaccessible. How to do that? Very simple: to be inaccessible, one must be unpredictable. That is, so that they couldn’t predict my actions. So I didn’t tell anyone where I was going or when. If I went out, I also used randomness: I chose my route using the numbers of oncoming cars. I had a mathematically developed method—how and in what zigzags to walk. They relayed Captain Alekseyev’s statement to me, who was complaining at the time: “What is this? Lenya is running around the city like a young horse!” And that was me, making those zigzags. Sometimes I would leave the house, look at a car number, and turn back home—I didn't need to go anywhere.

That’s how Castaneda, Smolyan, and Gnatepa (the last name is illegible) influenced my fate. They developed this methodology, and I exploited it. (I mean the works of Soviet mathematicians Smolyan and Lefebvre “The Algebra of Conflict” and “Conflicting Structures.”—L.T.). From Castaneda, I learned that I am on the path of a warrior, because I have a worthy enemy. And a worthy enemy is a very good thing, it turns out. You just can’t force a person to learn something, but when there is danger, that person has to learn. I started to learn and develop my own methodology, because throwing dice on the street or drawing cards was completely impossible. Instead of dice, I used the numbers of oncoming cars.

One time they told me that they had asked when I would be on watch. That means there would be a tail. I went out, looked right, left, looked at the balcony—the woman wasn’t on the balcony. I looked to the right—by building 46 stood a light-colored Volga car, “white night”—that’s what the paint was called. I looked closer—there was a very familiar face, pale yellow, a bilious-looking person. I had noticed that man long ago. As soon as I moved away—the car started. I looked at the number, what should I do? Straight ahead. I approach the intersection—the car number indicates straight ahead. According to my calculations—straight, straight, and straight to the sea terminal. And at the sea terminal, they had prepared another provocation for me. I left early to have room to maneuver, but I went straight, straight, straight and arrived a little earlier than I was supposed to. And they were trying to stage a provocation with the help of Holumbiyevska’s husband... They killed him later, because he went against them, and he had things to tell about them.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And what did they stage?

L.M.Tymchuk: He approached me, then fell to the ground, got up and said that I had hit him. When he was trying to do this, the shift was changing, the whole watch was walking by and everyone saw how it was being done. Tolya Lanin was there, the commander of the port’s people’s druzhina, and the mechanic Hryhoriy Oleksiyovych Myakhed was coming on watch. They saw everything. Lanin came up and said, “Lenya, what’s going on here?” I told him, “Tolya, they want to throw me in the slammer again.” The police were set on him: “And who are you?” He said, “I’m the commander of the port’s people’s druzhina.” And they all backed off. Later, the mechanic, Hryhoriy Oleksiyovych, came up. When we had already started working there, he asked, “What was that?” And I said, “That was just an attempt to put me away for good.” And he said, “Well, I’ll give them a piece of my mind.” He’s a communist, a very principled, honest man. After that, I even stopped saying “very honest,” because very honest is already dishonest. He is an honest man, a truly honest, principled man. He argued with me very often, we argued almost to the point of fighting. He sat down, thought for a moment and said, “Tomorrow I’m going to the party committee, I’ll tell them. I’ll do everything to put a stop to this.” He went to the party committee right after his shift. He later said that from their conversation he understood that they in the party committee knew about it. After that, the attempts at provocation stopped. That’s how many people saved me, even people I had never seen—the same Lefebvre (illegible), the same Smolyan, the same Castaneda. That’s how it turns out. And I only, as Carlos Castaneda writes in his work, had to tie my shoelaces in time.

I’ll tell this episode because it’s very characteristic. Carlos Castaneda is traveling with don Juan in the mountains. Carlos Castaneda’s shoelace came untied. He sat down to tie the shoelace, and don Juan stopped and watched him tie it. And just as he tied the shoelace, a landslide thundered down on their path. Don Juan says, “You see, we are worthless, we play no role—all that is left for us is to tie our shoelaces in time.” In this way, we turned out to be the victors. It’s mysticism, but it’s a fact.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And when the times of “perestroika” came, did you participate in any organizations?

L.M.Tymchuk: I never stopped my activities, but it somehow felt strange to me that there was no resistance to my actions, I didn't feel resistance. That is, the resistance decreased, and I rested a bit, because there was a very large expenditure of energy. When I got into the temporary detention facility, I thought I would rest a little. (Laughs). I was even a little pleased that I wouldn't have to run around, I'd get some rest there. But I got out—and it was running around again. I thought, if they had convicted me, I wouldn't have to run around. But the Soviet government and the KGB were no longer resisting.

When that didn’t work out for them, they fired Captain Alekseyev from the KGB, took his stars, and he became an administrator at the philharmonic. Then they called me to the OVIR and offered me to leave for Israel on someone else’s invitation.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Why Israel?

L.M.Tymchuk: That's just what they decided. And I said, “You save that option for yourselves, it doesn’t suit me, goodbye.” That was my answer. Why should I go to Israel? I have nothing against Israel as a country, but no one is waiting for me there, I have no interests there. Let Israel develop, go its own way, but what does it have to do with me? And why should I go on someone else's invitation? I have nowhere to go at all. Why should I go? Well, here I am, I arrive in a foreign country... “Why did you come?” I’ll say, “Look what a mess I made at home, I want to make the same mess here.” (Laughs). Others tell me, “Why didn't you leave? If I were you, I would have left long ago.” I say that I have no reason to go there. They have their own business there, and we have ours here, I have nothing to do with it there. That's how it was.

Then Hanna Vasylivna was arrested here, Barladianu was arrested—protests were already flooding in from here. I don't even know who and how many people signed those protests. Then they organized a Helsinki Group in Odesa. Even a certain Viktor Lanovyi appeared, the manager of the aid fund—he identified himself as such. Where he came from, I still don't know. He's a psychiatrist, but he immediately latched onto the money. I spoke with him several times, but I had a feeling that he was not one of us.

I like it when I do something, that I feel some kind of load. If I'm tightening a nut, I feel normal resistance. I know the nut is advancing. But when I turn it and feel no resistance—I know it's not moving. If I'm pulling a bucket of water from a well and don't feel the weight—I know there's no water in it. When I do something, I have that kind of feeling, it can't be described. I can talk to a person and when I feel that I'm pulling an empty bucket—that's it, I won't talk anymore. I developed this feeling during my dissident years. These constant arguments, constant conversations between people—I compared what I felt when I talked with Hanna Viktorivna, with Hanna Vasylivna, with Nina Antonivna, and what I felt when I talked with Gleb Pavlovsky, with Igrunov. I would remind them that it was time to “surface, enough working underwater.” Petro Butov, after my arrest, started signing protests, but before that he would write statements for us, but not sign them himself. But after the provocation against me, after the arrest—the number of signatures, the number of overt dissidents immediately increased. That's when, by comparison, I felt, I developed some kind of inner feeling, whether the bucket was empty or full, whether there was a little water in it or the rope had broken altogether.

I had that kind of feeling, that the bucket was empty, when I was talking to Gleb Pavlovsky. He's a very big shot in Moscow now, they call him by various such epithets—bad ones. Recently he was talking to a correspondent from “Deutsche Welle.” With some journalist or diplomat—he's the same as he was. He's a slippery person—he will never give a straight answer. He starts to maneuver, to twist things. And I remember the saying of a mathematician—again, a mathematician. He said this: “Thank God that He created a world where everything that is true is very simple, and what is complex and convoluted is false.”

That's why no one testified against me. After I broke that listening device, the KGB agents visited all my acquaintances—they tried to gather some material on me because they needed to imprison me urgently. They gathered absolutely nothing, absolutely nothing! Then they resorted to violating Soviet laws, according to which people like me were tried under Article 187-prime and Article 62. But they went for a violation, they falsified a case of hooliganism. A lot of people came to the trial. They gave me a year of forced labor.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And what year was that trial?

L.M.Tymchuk: I don't keep dates in my head. I have documents, everything is precisely indicated there.

L.M.Tymchuk: When Nina Antonivna was released from prison, she came here for her father's funeral...

V.V.Ovsiyenko: She was released in December 1975...

L.M.Tymchuk: There was already a Helsinki Group here in Odesa. Of three people: Kryukov, Kateryna Vasylenko (her maiden name was Vasylenko), and me. I can't remember everyone now, because there isn't enough time. When you start writing, somehow it comes back better.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: You need to write it down.

L.M.Tymchuk: I'm trying to write not just a dry chronicle, but something that can be read, that is interesting, that is artistic, that you can even laugh about. What does our “Memorial” write now? It’s a dry chronicle, almost no one reads it. It should be a work of art. There should be living people, there should be the Odesa flavor—the whole atmosphere needs to be conveyed.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And this must be done by the people who participated in that movement. Because if they don't do it, no one will. It will all be lost.

L.M.Tymchuk: Who is left—Hanna Vasylivna Mykhailenko, Zina and Vasya Varga, the Siryis went abroad, Butov is in Germany, Tanya Rybnikova is at the Literary Museum. Everyone must be remembered. Lena Danielyan is in the United States—she should also be mentioned, because she also signed protests. When I was on trial, I made many new acquaintances, including this Lena Danielyan, and many, many others. Viktor Borovsky, who is now in Canada or the United States, also passed through Odesa.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: He went to Canada. Professor Tynchenko sent him an invitation. He’s from Korostyshiv, from the Zhytomyr region. So, was he in Odesa too?

L.M.Tymchuk: He went abroad through Odesa. When he was leaving, I wrote a letter to Moscow for him to take to Iryna Korsunska or to Larisa Bogoraz herself—I don't remember anymore—so they would help him. Because I saw that this boy would perish if he didn't leave.

Vasya Kharytonov also left with our blessing, I also helped him leave. Both of these boys went through the psychiatric hospital. Vasyl Kharytonov—I don't know where he disappeared. I'm not very fond of corresponding...

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Viktor Borovsky worked at Radio Liberty, and then I don’t know where.

L.M.Tymchuk: I’m very stingy with letters. To write something is a very big event for me. I try to do everything very carefully, and I don’t have the experience to do it automatically, like professional writers do—they write everything smoothly at once, without correcting anything. But if I don't like a certain expression—I stop. I see that these words don't convey that atmosphere, the spirit of the event, they don't portray this person correctly—that's it, I've stopped.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: You mentioned the Ukrainian Helsinki Group in Odesa...

L.M.Tymchuk: I don't even know if I was a member or not, but I probably didn't miss a single document to sign. Whether I participated in the meetings of this group or not... It happened in such a way that we didn't even notice how the Helsinki Group was organized. Our circle grew, and grew, and grew, we communicated, we improved, Vasyl Barladianu gave us lectures, we had very useful discussions among ourselves. We didn't even notice how we became the Helsinki Group. We grew into it naturally—no one dragged anyone by the ears, people gathered on their own. I played the role of a spark that people gathered around. And then I wasn't even needed anymore—there was Hanna Viktorivna, Hanna Vasylivna, Vasyl Barladianu. It was already such a bonfire that I was unnoticeable against its background. There was such energy, confidence, conviction in our own rightness.

And now wherever you look—there’s no sense of resistance.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And are you a member of any organization now?

L.M.Tymchuk: I went to the Cossacks, I went to the KUN, I even visited the RUNVira followers. But I don't feel there what I can apply my energy to. It's just talk. If it's RUNVira, then let's practice RUNVira, not talk about it.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: You were born in 1935, are you still working?

L.M.Tymchuk: I worked as an electrician at the water utility, but it was reorganized, so I work at the city water supply. And I work well. How else—you can't live on a pension now. You have to work.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Thank you for the conversation. You have laid out your story well and told us about many people—this is very valuable.

L.M.Tymchuk: I must mention many people.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: When this text is transcribed, I will send it to you, and perhaps it will push you to write more extensive memoirs.

L.M.Tymchuk: You see, I don't have time. I was just about to get some work done now.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And we interrupted you. It’s already nine o'clock in the evening...

L.M.Tymchuk: So I said: let’s reforge syringes into wrenches. I’m very good at that. In my entire life, I have only been on sick leave once.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: You are so strong and stand so firmly on your feet!