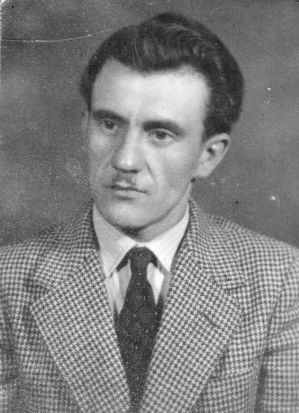

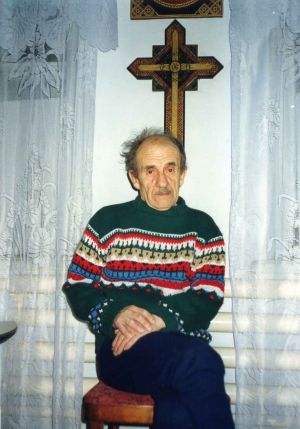

An interview with Petro Stepanovych SARANCHUK,

with the participation of Nina Ivanivna MOROZ.

P. Saranchuk’s corrections were not received. Final reading on July 30, 2007. Subheadings by V. Ovsiienko.

V. V. Ovsiienko: On December 11, 2000, in Kyiv, at 30 Kikvidze Street, in my apartment, number 60, Mr. Petro Saranchuk tells his life story. Ms. Nina Moroz is present. The recording is by Vasyl Ovsiienko.

Childhood

P. S. Saranchuk: I was born in the Ternopil region, in the village of Konyukhy, Western Ukraine. It is now in the Kozivskyi district. Back then, it was the Berezhanskyi povit. In 1918, my father, Stepan Hryhorovych, served as a clerk in a battalion of the Ukrainian Galician Army during the campaign on Kyiv. There was a typhus epidemic in the UHA. My father recovered in Fastiv. He returned from near Kyiv to Lviv in a typhus convoy. After that, he was a member of the UVO—the Ukrainian Military Organization. Then, until his death, he was a man dedicated to enlightenment as a member of Prosvita. My father was a carpenter, but he was quite literate and handled all of Prosvita’s record-keeping. All the operational matters were in his hands. My father was born in 1898. He lived until 1990. He did not live to see my return from prison. We missed each other by only three months. (Later, P.S. says it was two and a half months. He was released on February 28, 1990. This means his father died at the end of 1989.—V.O.).

My mother died earlier. My birth mother (we called her our first mother), Teklia Matviiv, died in 1929, leaving the three of us as small children. My father remarried in 1930. He married Marta Zabudzinska (or Budzinska?), who lived with him until 1978. I never saw her again—she passed away.

I was born in 1926, on October 26.

From childhood, I spent a lot of time with older people, my parents' friends, who would gather at our house. I grew up in this Prosvita-affiliated and patriotic society of older people, which was very important for me. My father had friends who were teachers, students, people like the Symchyshyns. He would take me with him there. That is how my understanding of society and the state was formed.

The thing I remember most is my father’s first arrest in 1930, during the Pacification. My worldview was formed on this from childhood. It was a time of arrests of former UVO members—members of the Ukrainian Military Organization, which became part of the OUN in 1929.

My father was under investigation for six months, and this was counted toward his prison sentence. He suffered a permanent injury there; his leg was ailing. That helped him: he was given a short sentence, just six months in total, and released. The longest sentences then were three years, for two men.

But at home, there was no peace from those uninvited guests: first the police, then the required police check-ins, that is, mandatory appearances. All of this affected me as a child. Why? They would be saying something, and I kept asking: why do they come to our house with knives, with those bayonets?

I started school at the age of six. I finished the Polish seven-year school in Konyukhy in 1939, just before the Polish-German war. When the Soviets came in 1939, they demoted us: from the seven-year school, to equalize us with the Soviet school, we were sent back to the fifth grade. We didn't even make it to the seventh Soviet grade—the war started again.

V. V. Ovsiienko: What, was the level of education in the Polish school considered lower?

P. S. Saranchuk: They didn’t recognize our seven-year school simply because we didn’t know the Russian language.

V. V. Ovsiienko: Is that so!

P. S. Saranchuk: It was for the sake of the Russian language that they demoted us by two years. Mostly, they focused on literature and grammar. They had no complaints about the other subjects.

The War

So I made it to the war, to the arrival of the Germans. In October 1942, they took me to Germany. I escaped during the loading onto a train at the Berezhany station.

V. V. Ovsiienko: How did you manage to escape?

P. S. Saranchuk: It was quite simple: they were herding a whole hundred of us. One group was already loaded, and they were herding the second one behind. I might have even gone then. It was a somewhat hungry year, but it was already autumn, and things were improving. But I saw on the side, from behind a fence, they had rounded up Jews from the ghetto at the station. They were being loaded as prisoners—whether you wanted to or not, you had to go. One man from Hutsulshchyna tried to run, and the policemen started shooting. I looked and thought: they haven't even finished loading, and they're already shooting! So I turned around with my sack and went along the wooden beams where the Jews were surrounded—we didn't have a convoy behind us. Only an escort, the one handing us over, and some German officer. They were just herding us to be loaded, without a convoy.

As I was running away, I saw a Jewish man, Myl Shloma, standing on a stump. And I was running with a sack. I threw the sack off and, in a panic, yelled: “Pan Myl, catch!” And my buns and little rolls spilled out… But the strap of the sack somehow got caught on my fingers, and I was running so furiously that I reached the river and thought: what do I need an empty sack for? And I threw it away.

V. V. Ovsiienko: So everything spilled out?

P. S. Saranchuk: I poured it out for him. Because he was yelling after me: “Sonny, whose are you? Sonny, whose are you?” He had been a cashier with us during the logging of the community forest. He was a frequent guest at my father's house.

I no longer showed my face in the village, not even to the police. I hid until the snow fell. I slept in people's yards. I met my father once, and he took me with him: “It will cost you dearly—you'll freeze, get sick, so it’s better to go home.”

They came. But the police were local people. They sat for a while with the soltys—the village elder—he was a friend of my father's from a Polish prison back in 1930. They sat and then just waved it off and left. After that, I was finally able to go out on the street.

I worked a bit: we were working in the church; I was painting. There was a monk there from a monastery. He himself was a good artist, a painter who had graduated from the Roman Academy of Painting. We worked together, the two of us, and I got a bit of a knack for painting there. But it didn't last long: the front began to approach.

After my escape, I had already joined the Ukrainian Youth. Well, I didn't just join; I was officially accepted.

What was dangerous for me at the time? I would very boldly walk up to German vehicles and take whatever wasn’t nailed down.

V. V. Ovsiienko: And what was that?

P. S. Saranchuk: Submachine guns, rifles, binoculars, bandages. I even cut out and pulled out the bandages they had as spares, the emergency ones, stitched onto their tunics, on the lapel, on two pockets, sterilized. Wherever I passed, they no longer had these pouches. But it was a dangerous thing. I got caught three times.

I remember one time I took a revolver from a German. But my mistake was that I should have taken it together with the holster and belt, but I just slipped off the revolver and left the belt in a yard. So he caught up with me, that German. Ryzhoch—I still remember his last name. He took me for a kid and just scared me, said he would take me to the front, and simply locked me in the cabin of his military vehicle. So I sat there. The front was only 15 kilometers away, very close. I escaped from that vehicle. Well, not escaped: some driver came on alarm and threw me out of the vehicle. So I was on my way—and ran off.

That German came to my father for three more days: “Perhaps you know, the child took it…” My father told me: “Give it back!” I said: “He’ll shoot me with it! Who should I give it to? And why give it back? Did he catch me red-handed?” The revolver stayed with me.

The Germans were not vigilant. They were not used to anyone stealing things or things disappearing from where a person had left them. Only later did they call it “tsap-tsarap, tsap-tsarap.” Meaning, things are being stolen.

But we were already organizing. The front shifted. Following the front, already in 1944, UPA insurgent units appeared. The front passed through our area right during the harvest. It was after the front passed that people started gathering rye, in July or thereabouts.

Well, by that time I had acquired a full set of weapons for myself: ammunition pouches, a carbine, a bayonet, a backpack—everything that was needed. I armed eleven of my friends—each with a carbine, one ten-round rifle, two MPis. But when our unit was being formed, they took the automatic weapons away. Probably for the officers. I’ve already forgotten which month that was…

V. V. Ovsiienko: You say you armed them—was this on your own initiative, or was it already some kind of Ukrainian Insurgent Army unit?

P. S. Saranchuk: A UPA battalion was stationed in our area. It announced a recruitment of volunteers into the UPA—military personnel: Polish corporals, German and Soviet officers. These were taken. They immediately became squad leaders when the battalion was formed. This was Roman’s battalion. The supply depot for this Roman’s battalion was here, so they conducted a rearmament: exchanging German weapons for Soviet ones, for whatever was more convenient and necessary.

From there, we set out on a march. We were already two companies strong, marching from near Ternopil all the way to Rohatyn. In the Vulchynetsky forest (the village of Vulka) near Rohatyn, there had been partisan huts since the war. We occupied them. But there, they turned our two companies into three and fully formed the battalion. Roman’s battalion. It later became Ren’s battalion, when a new commander, Ren, arrived. So we marched as two battalions. They left us for training in the Vulchynetsky forest, while Roman's battalion moved on.

Between Berezhany and Rohatyn, we suffered a great disaster. It wasn’t a battle, it was a slaughter… Our camp was quite compact. We had eighty pairs of horses with us, carts with ammunition and food, our own field kitchen—all pulled by those horses. But the Soviets broke through our defense. It happened during their third assault, when their own blocking detachment was shooting at their own men as they retreated. Well, the retreating ones broke through. Everything got mixed up, it came down to bayonets, to knives…

Such a disaster might not have happened. But they surrounded our section of the forest and used flamethrowers. They set the forest on fire with some kind of combustible substance. It stank as if they were pouring bitumen on the trees. The trees were burning, the ground was burning, a man couldn't stand it there. Everyone fled from the fire. They caught us, they shot us.

We didn't even make it halfway to Kalush (and we were heading to Kalush). The commander of the third company was Holka. He’s in the USA now, has his memoirs in the *Litopys UPA* [Chronicle of the UPA] and describes this battle there. This terrible thing clattered on all day. They had already pinned us to one edge, so he shouted: “Boys, hold on till nightfall! Hold on till nightfall—and then break out in all directions!” Eighty of us got through. We took a "Maxim" machine gun, its whole crew, and 80 of us slipped out of that fire through this gap. Well, as for the rest… Many people died.

We all went back to our homes, although we were supposed to report to formation points. But after such a terrible first defeat—that was no longer an army. And what kind of army was it? Just youths. They marched off with a great “hurrah!” and later could barely drag their beaten legs behind them. The local leadership ordered us to report, because they had come to recruit new people, but they weren't successful—few joined the new battalion.

Then, in the fall of 1944, I was appointed the kushch-level guide for the Youth. Our kushch had 74 men. Everything was divided into squads, and each unit had one firearm. Everyone there was familiarized with weapons. They exchanged weapons, starting with the Mauser and the three-line rifle, and then mastering automatic weapons. That’s how we prepared for the second recruitment drive.

Toward the spring of 1945, Shukhevych was there. He was guarded by Bondarenko's honor guard. There was some kind of council, a lot of partisan troops were there, guarding this headquarters. They managed to leave.

And near us, in the Youth, they had already set up officer schools. There were few people there. It was already a preparation for disbandment. But the youth, on whom hopes were pinned, were going through the school for the OUN underground.

Trouble struck in March 1945—general round-ups. Again, there were many casualties among the civilian population and the underground group. Those were hard times. That officer school even left our kushch, and we were completely disbanded. And it was done just in time, because they had just started catching people; there were mass repressions. And not just catching—they herded entire villages for the so-called "state check-up." When they took people for the "state check-up," they released them in droves: women with children and so on. But the attitude of the occupiers toward the population was clear. They drove this crowd, women with children in their arms, and beat them. The mud was very deep—it was March. They had no pity for whether it was a woman or an old man—everyone was under the stick. It was terrible!

V. V. Ovsiienko: Were they herding them to the station for deportation?

P. S. Saranchuk: No, they were herded to the district center here, and there into the temporary detention cell. They occupied the Catholic church and the school there—and they took the whole population in for investigation. An investigation is an investigation—but they beat everyone terribly—both women and old people. And then they released them just the same.

It was only after this that the underground began to reform. But the kushch had been reduced to a stanytsia, we were disbanded altogether. The underground phase of the struggle began.

But it did not remain stable for long, as it should have. Although units still circulated, there were raiding groups, the people began to slowly become demoralized.

I was then appointed the stanytsia leader for this Konyukhy kushch; I held this stanytsia. So I had to, whether legally or not, let people know that not everything was crushed. We would form groups of four or five horsemen and ride noisily through the village (and the village stretched for 10 kilometers), so that the population would see that not everything was destroyed. These weren’t partisans, just an occasional clatter. And then we would listen to what people were murmuring about it: “Look at that! It barely gets dark, and they appear! It means they haven't crushed them all!”

This continued until 1946, when the polling stations were being prepared. Then the occupiers blockaded all the territories, connected the headquarters by telephone, and so on. There were still two months, if not more, until the elections. Those elections of theirs were unsuccessful.

V. V. Ovsiienko: What elections were these and when?

P. S. Saranchuk: In February 1946, there were elections to the Supreme Soviet and to local councils. Because everything was shattered, there was nothing. A government was being formed completely, but under the lash.

First Arrest

Truth be told, I didn't make it to those elections, because I was caught on Epiphany, and after the elections, on March 6, I was tried.

V. V. Ovsiienko: How did that happen?

P. S. Saranchuk: I had been stepping out of that area into Podillia. I was returning to my forest (where the stanytsia was) and got caught in the Zalissia farmsteads near Konyukhy. But it wasn't just that I got caught. The NKVDists were following me: someone had pointed me out. The Soviets killed him later. This boy pointed me out. They arrested me near a farmstead in the woods. There was a heavy frost—and I fell right into it... They suspected something, because they had followed me for 15 kilometers to the place where I had stopped.

V. V. Ovsiienko: They took you right in the forest, unarmed?

P. S. Saranchuk: I didn't go to Podillia with a weapon. I stayed openly with people I knew, like a son, like a child. But that was among people who knew me, or to whom I was "passed along." So it was right before the Epiphany holidays, on the very Holy Eve of Epiphany, that I got caught.

V. V. Ovsiienko: And where did they take you and hold you?

P. S. Saranchuk: In some homeowner's cellar. There was a garrison in the village. I was in that cellar for three days. There was nothing to even lock the hatch with, and they even rolled a barrel of cabbage on top of it. They considered me that strong. And I could no longer stand on my own... From there, they transported me to the neighboring village of Vybudiv.

But once I arrived in my own territory, my boys had signed a "two-hundred"—a document closing the case. They had mentioned me a bit, as part of their defense. And then, there you have it—they bring me in! I arrived before them, crippled. I said: “How could you do this?” Well, one of them answered: “We thought you wouldn’t come back!” They thought, they thought…

The investigation was very confused. The investigators had material on my involvement with the Youth. And then, for those who weren’t even in the Youth, they had material on the stanytsia, on the OUN. It didn’t work out well for them. Some said he was a kushch leader, others that he was a stanytsia leader. Things were already heading toward a grave resolution for me…

But the investigation didn’t stop there, because they took me from Kozova, from the Kozivskyi KGB, and transported me to Berezhany. And in Berezhany, there was also a stanytsia. A special group attached to the NKVD included traitors—former OUN and UPA members. They held me there for two weeks, and they finished me off there. There was nothing left to beat… Anyway, they returned me from Berezhany back to Kozova for further investigation.

This re-investigation cost me very dearly, of course. They crippled me. But it doesn't matter... They tried all ten of us together.

V. V. Ovsiienko: Where were you tried and when?

P. S. Saranchuk: On March 6, 1946, we were taken to Ternopil and tried in March. And on April 28, those of us who had been sentenced were shipped out to Kharkiv.

We arrived at the Kharkiv transit prison right on Easter Sunday. I was there for a very long time because I was maimed, my wounds reopened, and later my whole body broke out in sores, and my head started to rot. I went to the prison hospital. The doctor was some old Jewish woman, and she didn’t treat me, but scraped off the scabs. In short, she was maiming me there. It was a paramedic, a boy from the Lviv region, who warned me not to go to her. He said she had already crippled more than one person there. He advised: take warm water and make a compress. Well, and the rest—with zelyonka. And it helped.

In the Urals

I languished in that transit prison until August 9, 1946. And nine days later, we found ourselves in Kuchino in the Urals. It was the Vsesvyatskaya station, and then after the Vsesvyatskaya station was the first camp.

V. V. Ovsiienko: The settlement of Kuchino in the Chusovskoy district of the Perm region. I was imprisoned there in the 80s too…

P. S. Saranchuk: Yes, they brought us to Vsesvyatskaya. They finished us off there in the logging camps, later moving us to health-improvement centers at Stvor. That's 18 kilometers from Vsesvyatskaya, the settlement of Stvor right on the Chusovaya River. But they dragged us back and forth. Because in 1947, a dysentery epidemic broke out there. The camp chief, Major Severov, and the head of the medical unit, Senior Lieutenant Suvorov, caused the epidemic. They brought on this dysentery with rotten flounder, written off from a military division, and with soy press cake.

V. V. Ovsiienko: What did they make from the press cake?

P. S. Saranchuk: Soup. Soup from the press cake and porridge from the same cake, sprinkled with pearl barley. Stomach disorders started, and the whole camp fell ill. There were even two barracks for tuberculosis patients. I don’t remember how many barracks there were, eight, it seems, quite spacious, and all that was left were one invalid barrack—where they wove bast shoes—and one or two work brigades. Everyone else was sick. They carted corpses out of there, but they performed autopsies on the corpses every other day: one day funerals, the next day autopsies. They would bring out 20-25 corpses a day in boxes up the hill toward the forest and bury them. And the next day they'd collect more corpses.

A visiting commission from Perm put a stop to this killing of people. True, they took away that Severov and that Suvorov. Some captain took over, a raging drunkard—he would beat people right on their bunks. And a woman became head of the medical unit, supposedly a former zek named Yelena Rastorguyeva. She was very merciful to these people. And then people got back on their feet, and those who survived were sent back to their original camps.

Tayshet

These camps didn't exist for much longer, because they organized us and began shipping us to Tayshet. In the autumn of 1948, we arrived in Tayshet. I spent a year in the Tayshet camps, passing through five of them. There I had the opportunity to meet Archimandrite Malyuta of the Pochaiv Lavra, Metropolitan Sheptytsky's doctor Korkhut, later the editor of the Prague journal *Visnyk* [The Herald]—last name Baran, and the commander of the Northern District Vorobets (he went by the pseudonym Vereshchaka). He died in the Tayshet camps.

Norilsk Uprising

A year later, they transported us from Tayshet to Norilsk. That was in 1949-1950, I don't remember exactly… We lived in the katorga labor camp in Norilsk until June 4, 1953. The uprising began in the third katorga camp. It lasted exactly two months, until August 3. The underground committee, which actually led the revolutionary work, was headed by Danylo Shumuk (1), Stepan Semenyuk-Kernytsky (now living in Warsaw), and I don’t remember the third person. It's not that I don’t remember, I just don’t know his last name.

On June 4, 1953, right after Beria’s arrest, the uprising began in the fourth katorga camp. At first, it was a protest against arbitrariness, and later it became a list of demands under the slogan “Death or Freedom!” It lasted for two months, and over those two months, it evolved through various phases. A glimmer of hope appeared after the arrest of those Beria henchmen. The administration itself cut off contact with us; they panicked during those arrests. We held out until August 4.

V. V. Ovsiienko: And what was your role in this uprising? I heard you participated in making leaflets. That’s interesting.

P. S. Saranchuk: My part in this uprising was as follows. In the small building where the KGB used to be, they printed leaflets. This was a secret from the camp population. Meletiy Semenyuk (2) stood guard there. He stood at the doors where they made the matrices, the stencils, and other things, and where they stamped them out.

V. V. Ovsiienko: And what were those matrices made of?

P. S. Saranchuk: They were cut from rubber. They were very poor. So we decided to make our own printing press, if you can call it that. There was Petro Vlasovych… I’ve forgotten his last name.

V. V. Ovsiienko: He is named in your file as Petro Volodymyrovych Mykolaychuk, from Uman.

P. S. Saranchuk: He was a sculptor himself, but had once worked in a typography shop in Poltava. He was a great master. And there was another fellow from the Karaganda transport (I don't know him, because it was a time when no one asked anyone: where are you from, what's your name, because everyone who needed someone already knew them). So, there were three of us working in a secret room. No one had access. I was an engraver, making matrices for the type; I made the forms; Petro Vlasovych himself trimmed them, and this third guy prepared the lead blanks, because everything was made of lead. We printed leaflets the size of a standard school notebook. Well, we set the letters in grooves, and it was very good, very successful. This terribly enraged the administration…

V. V. Ovsiienko: Did you set the text one letter at a time, or were whole texts carved out?

P. S. Saranchuk: No. We cut them one letter at a time, then set the type. We hammered out a lot of lead, and Petro Vlasovych assembled it. He carved each letter separately, uppercase and lowercase. For this, we collected all the vials we could find from medications. Each letter had to be made. Uppercase alphabet, lowercase alphabet, commas, colons—everything that was needed. It took a lot of time. But it terribly infuriated the administration—that we weren't writing anymore, but printing! The first thing we did was to shower the stadium with these printed materials.

V. V. Ovsiienko: In what way?

P. S. Saranchuk: With kites. It was a large kite, glued together from slats and paper. A tail was attached to it to maintain balance, and then we let it out on a string—like children do. But our string was three kilometers long, on a windlass. The kite rose quite high during a wind. We even chose which way the wind was blowing, so the kite carried our leaflets all the way to Kaerkan.

V. V. Ovsiienko: And how did you time it for them to drop?

P. S. Saranchuk: Crosswise—from both sides, on the nose and in the middle, we tied a packet of two hundred leaflets each. It depended on the size, because we made many kites.

V. V. Ovsiienko: That’s quite a lot of weight.

P. S. Saranchuk: A lot, but the wind could lift a kite of that surface area. And we attached a fuse to it—a wick tied to the packet. It was cotton wool soaked in potassium permanganate; it burned very well. We measured how much time the wick took to burn. A wick on a thread was attached to each packet. We calculated how much time was needed for the kite to rise, how many meters of thread were needed. But you could see it.

One kite carried three packets of leaflets. It would drop two hundred each, six hundred leaflets in total. All the paper in the camp was collected; we even made these packets from cement bags. But what infuriated them most was when the kite went up, they would shout: “Oh, look what we've come to, they've reverted to a child’s mind, flying kites!” They started shooting with submachine guns, with rifles, then they figured out to tie a stone to a rifle to shoot it down. They did bring one down; the wind spun it around. Then they launched their own similar kite, but raised it over the zone, crosswise to ours, to tangle it. But they launched it from a two-story building, and there were telephone and electric wires, so they couldn’t get it right. That gave us something to laugh about: look how they're copying this child's mind!

V. V. Ovsiienko: And was the camp surrounded? Did they shout at you through megaphones?

P. S. Saranchuk: There was a time when they set up loudspeakers. They agitated for us to cut through the fences, to make exits. When all the loudspeakers screamed into that square of the zone—there was a lot of noise. This noise disturbed some people—for some reason, many Balts left the zone. 180 men came out.

V. V. Ovsiienko: And how many people were in the zone altogether?

P. S. Saranchuk: Five and a half thousand katorga prisoners. Some were sick. There were five thousand men on their feet. 180 men came out, mostly Balts, Belarusians, Russians. There were also so-called “traitors to the Motherland,” former military men, but they weren't sentenced under 54-1-a, but under 54-1-b—which is “military treason.”

So, a commotion ensued.

But we had an underground revolutionary headquarters. Semenyuk and Shumuk were in charge. The headquarters had its branches. I was involved in the secret service for preparing the uprising. But there was also an official, declared headquarters, which I think had 15 members. At first, a man named Vorobyov was in charge of this; he was later suspected of preparing an escape. Whether he wanted to provoke an escape or escape himself… But the main role belonged to Shumuk. The headquarters coordinated events completely. The entire camp population was divided into regional groups. An authoritative countryman would gather people from his region—and that was a regional group. So, they gathered very quickly upon call. It was the best way to get people together.

They opened the gates and those 180 men walked out of the checkpoint. Then our posts formed two rows of people. Those fleeing the zone rushed and attacked them. They weren't allowed to do that to these brave men. But it wasn't easy to stop people. Before closing the exit, the administration guards said: “Whoever is leaving—leave! We are closing the gates.” Someone who hesitated—“Why not escape?”—and didn’t make it to the gates, found himself in a very awkward position. Those were unfortunate people! No one said anything to them about it, didn’t reproach them, but they themselves found themselves in a very awkward position.

The escapees were received outside the zone. Colonel S... I've forgotten…

The military stormed the c they brought in five trucks with armed soldiers in helmets. Their weapons were tied to their hands with straps. They opened fire at full speed from the gates all the way to the wire fence. They cordoned off the zone with this live force on trucks, cutting the camp in half. First, they dealt with the left side, dragged the prisoners out of the gates, and then they went after the right half with clubs and ramrods.

That was the end of the defense. They led us all out into the tundra. They had a large pit prepared there for some construction project. They herded a great many people there. Shumuk and all the leaders of the uprising were taken away. They beat them terribly: while they were walking, and those who tried to run. Even the snitches, as they were being led away, threw themselves at them with all sorts of sticks. It was a momentary, not a serious, attack. But the guards would lift Shumuk up and throw him to the ground. They didn't kill him, but he got it good. They were immediately taken to Vladimir Prison.

I want to say that Shumuk finished his book *Beyond the Horizon* in Vladimir Prison. Later, he wrote an addendum, *What I Lived Through and Reconsidered*. When we met for the second time, already in Mordovia, I gave him some material for *What I Lived Through and Reconsidered*. Later still, I collected some photographs and sent them. In this way, I helped him finish his book *Beyond the Horizon*.

A Long Journey to Ukraine

V. V. Ovsiienko: And what was your fate after the uprising?

P. S. Saranchuk: After the uprising, part of the people were taken to Vladimir Prison. Others were taken somewhere to the mainland in several transports. They held us for a long time and threw us around various points. I don’t know how it was, but Korol says they were preparing these people either for execution or for some other reprisal. But when the head of the Norilsk Combine, Zverev, returned, all sorts of persecutions stopped.

They didn't keep us in one place but moved us to Medvezhka, then somewhere else. It was only when commissions were created to review cases that they began to treat us a bit more humanely. There were already results from the commissions’ work—some were completely released, for others, they left a few years.

They took our small group last. But few were released. I, for example, should have qualified as a minor. I should have been rehabilitated, but it didn't happen. It didn't happen only because we were already in a special camp. For the first review by the commission, they took us from Seredniy to the administration building. The commission didn't bother with me because they called me a bandit. When they called me a bandit, I protested right there at that commission.

I didn't expect a good result, but I already had two years of work credits and had served about ten years, so even if they didn't reduce anything, I only had 3 years left of my 15-year sentence. So I wasn't, as they say, shaking in my boots over it. But they were supposed to release me because of my age, as I was accused at seventeen, from the time of my service in the insurgency. So they cancelled my rehabilitation and reduced my sentence by three years. But they escorted me out of that commission. The commission's decision was sent to the camp later—that I had 6 months left to serve to complete 10 years. They took off 3.

Well, with that I was eventually released. But they took me to Tayshet, where I finished my term, and since I still had those work credits, luckily, I managed to cover those two years with the credits. Because those work credits didn't exist for long—I managed to get out on them.

V. V. Ovsiienko: And when did you, as you say, get out?

P. S. Saranchuk: On October 28, 1956, right before the “October” holiday. Because during that “October” holiday, we stopped in Bratsk with another man to visit his acquaintances. We spent the night there with those people. Our train arrived. There were seven other people traveling. We joined them.

And what was strange was that nobody… They gave us these travel tickets. Nobody escorted us, just quickly, with this pea coat—march, march, and march. They marched us like that (was there a convoy or some escorts, or not????) all the way to Krasnoyarsk. In Krasnoyarsk, there was a crowd—many people at the stations. Some policeman came, looked at us, took our tickets (there were a lot of Gypsies for some reason at the station with small children and other people), and he took all our tickets, stamped them, put us on the Moscow train—and that's how we left. So we didn't have to suffer at those stations. As they say, we had “green lights” everywhere.

“On My Native—Not My Own—Land”

I arrived home, in my Konyukhy, in the Berezhany region, right for the Christmas holidays, already in 1957. But I didn't get to graze there for long. Although they did give me a passport. They did everything I needed, because the secretary in the village council was a childhood friend of mine. We hadn't seen each other for a long time, since the war. He did it for me quickly, and then they summoned me because I had to present my release card. The chief scolded the secretary a bit for that. He came and said: "Trouble! You have to go to the..." I copied it, took it there... At the military commissariat, they stamped it, stating that I was not subject to military service based on some law BB. To this day, I still don't know what BB stands for.

I didn't get to graze there for long… I moved. I could have stayed at home a bit longer, but another man was released and arrived, from the underground. So they rounded us all up—and out in 24 hours! It didn’t take exactly 24 hours for us, but something like that...

We went to Mykolaiv. To avoid ending up in Kazakhstan, where they were deporting released insurgents.

A year later, I returned to Konyukhy again. I was just drawn to home… Whatever you say—among strangers, and with this stigma… The people from this state farm, where we had settled, go to vote—and we also go with them, as if to vote. But we don't go to the ballot boxes, just to show people that we are also voting. But this charade didn't last long.

After a year, I came home anyway. I stayed until March. But they didn't forgive such rudeness. A representative from the district KGB and the chief of the district police arrived, along with someone else, I don't know who he was, he didn't introduce himself. And I had again submitted my documents for registration—that same village council secretary was helping me out. So they gave me 24 hours to be gone (this was in 1958). But it didn't happen in 24 hours, I started making some excuses. The next day they sent me to the district police station. The chief there was some Major Vershok. He told me nothing more than: “Whether you like it or not, I have to exile you: there are people who do not wish for you to be here.” And he drew up a document for me, officially prohibiting me from residing in my native land.

But he treated me humanely. At that time, released insurgents were deported from their home areas, because wherever you looked in Ukraine, you couldn’t be within 102 kilometers of a regional center. So all these people were deported to Kazakhstan. But my fate was to be 50 km, but from the old Polish-Soviet border, that is, east of the Zbruch River. I won out in that I just went to Mykolaiv. True, I registered for Dnipropetrovsk but went to Mykolaiv. I was very cunning, so cunning that they eventually asked me: “Why do you write one place, but go to another…”

Well, so I settled in Mykolaiv until 1970.

V. V. Ovsiienko: How did you live there? What did you do? Did you work somewhere?

P. S. Saranchuk: I worked in construction, and at a reinforced concrete plant—in short, I worked wherever they put me. I was thinking about my own place to live. And this was a construction plant, and I had a decent reputation there, both with the administration and with the people. And I decided to build my own house, as I had been living in a dormitory for six years. I searched for a place anywhere—there was none. Then, in 1965, they started allotting plots for construction. I managed to get six hundredths of a hectare for myself. True, with all sorts of difficulties. But the fact is, I got a plot. And what was triumphant for me—was that I dug the foundation for my house and laid it with stone. Then I started looking for materials. I didn't squander my earnings but saved them for a home, whatever it might turn out to be. And I built a house with the help of people.

In 1966, right on May 1st, people came and built the walls of my house up to the window lintels on my foundation. And on the 9th, on Victory Day, by lunchtime, my masons, as is tradition, placed a flower in the wall. The people showed a kind of solidarity, both familial and social, because they came to this construction site, and there was no longer any need to hire anyone. Well, those were the neighbors. And in 1967, I had already moved into one room and spent the winter. And by 1969, I had completely finished.

Mordovia

I survived another winter in 1970, and then in May 1970, they came to arrest me (for Vakhtang Kipiani, it was July 1.—V.O.).

V. V. Ovsiienko: On what charge?

P. S. Saranchuk: They didn't present the charge to me right away. They came in: “Hands up!” They turned me upside down, in short, they had me under their feet. And only during the investigation under arrest did they charge me—“anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation.”

They gathered all sorts of muck. But the main thing was, they conducted a search and found some of my writings and a brochure from the IV Grand Assembly of the OUN in Winnipeg. This was the main material for the trial. And they tried me under Article 62, part two. And they slapped me with 8 years of special-strict-regime. I served these 8 years in Sosnovka in Mordovia, which for some reason was called Korabel [The Ship]. There were many guys there, and that’s where I met you at the hospital...

V. V. Ovsiienko: You gave me a beautiful postcard there that you painted: a Ukrainian boy carrying an Easter egg bigger than himself. You both signed it, you and Mykhailo Osadchy. And that was the mistake—that you signed it. Because when I was returned to my 19th zone, they confiscated the postcard during a search and wrote in the report that “the alienation of any objects in any form between prisoners is prohibited.” I had “alienated” the postcard from you—or you had “alienated” it from yourself for my benefit... Exquisite Jesuits! So please, tell me about Sosnovka. Because I was on strict regime then, and you were on special, i.e., cellular, regime. What were the conditions like there, what events took place?

P. S. Saranchuk: There’s not much to boast about. But in 1972, I met Danylo Shumuk there. I met people there who had been imprisoned since the 50s. Kost Skrypchuk, Mykola Konchakivskyi were there. They had already been serving 25, 30 years. They were there without a chance of release.

V. V. Ovsiienko: And Dmytro Syniak was there?

P. S. Saranchuk: And Dmytro Syniak. But they held Dmytro Syniak there as a katorga prisoner. Although katorga had long been abolished, they commuted his death penalty to 20 years of katorga. His accomplices were there: they were given 25 years, but not katorga. It was time for Dmytro to be released, but his partner—I've forgotten his name—was still serving.

When I was in the hospital, I had opportunities to see the guys from the strict regime—Vasyl Stus, you, Zoryan Popadyuk—the youngest. And in our zone, we had a cellular regime. We were grinding some kind of glass there. The dust was very harmful. I found a good way around it: I would rub it until it got hot, or drill those holes, and then pour water on it, and it would all crack, but I kept doing it. They noticed something suspicious about my work, so they threw me out of that workshop. They gave me another job, something to do with cleaning, but that’s not important.

What is important is that they predicted ten years for me, but they only gave me 8 years and without exile.

V. V. Ovsiienko: That would be from 1970 to 1978. But towards the end, you were transferred to the strict regime, to the 19th camp, when I was no longer there?

P. S. Saranchuk: Yes, but only to tear me away from the guys. Because we had a “capsule mail” system there, and they suspected me of it. Well, there was no need to suspect, they knew who was doing it. I was making microscripts. I made a lot. Later, Eduard Kuznetsov started making them too. We had a few disagreements. He started writing the texts himself, but I continued to make the capsules. I could fit 250-280 characters on a piece of cigarette paper in one capsule. It was very painstaking work: I did it for Moroz, for Danylo, later for Romaniuk, and for Kuznetsov as well. Just rewriting a text in a tiny script. My letters were the size of a poppy seed. That's how I paid them back for my imprisonment.

They suspected something and started taking samples of my handwriting. This was after a plan of the camp got abroad and was published in a newspaper, I think it was *The New York Times* in July 1977—that really enraged them. Then they started coming down on me. At first, to write some notices, then to rewrite something—that is, taking a handwriting sample for analysis. I wrote in block letters, albeit small ones, but the experts were working on it. But I'm an old dog: I didn't refuse them; on the contrary, I made some inscriptions for them on little boards, their seven-year plans. But I was on my guard.

And then some guy of theirs was drawing a plan of the camp. They brought me to their commandant’s office: “I don’t like this plan. It’s crudely made. Couldn’t you make it more presentable?” I said: “I won’t take it on, I’m simply afraid. You have to specify things, know what’s where. Why do you need to redo it? I can’t. It’s simply too much for me.” Then they left me alone.

But later they caught up with me in the hospital. I overstayed there a bit because I had made a deal with the doctor that I would make him some wall stencils for whitewashing. He went on vacation himself and left me for a month. They sent this Kyriukhin, the authorized agent. I see he’s arrived: “So what, so how, what are you sick with?” I say: “Ask the doctor what I'm sick with.” “And why are you here for so long?” “Because I’m sick, that’s why it’s long.” What was I supposed to tell them? They're holding me, so they're holding me.

Then they were plotting something against Mykhailo Osadchy. His case had no physical evidence. So they wanted at least some scrap of paper from him to add to the case file. They came once, a second time. And he was somewhat helpless, Mykhailo. He came to me for advice. I ask: “What does he want?” He says: “The basis on which the case rests.” I say: “And what is he promising?” “Well, that you’ll finish your sentence.” I say: “Mykhailo, right now you are being held illegally, and that’s what’s eating at them. But if you do this,” I say, “it’s a lost cause. You’ll get an additional sentence. Don’t even think about it!” But he hesitated, he wanted to go home…

Well, then they latched onto me. The doctor comes to me and says: “I’m going to discharge you.” “But why? You said…” And I had already made the stencils. He says: “You’ve been sitting here too long. There are complaints.” “Well, thank you even for that.”

Then, just before my release, they transferred me to the 19th zone. I was there for two months. And that, with a scandal. After that, two months in Saransk.

Again in Mykolaiv

And after that, in a little over a month, they transferred me from Saransk, from Mordovia, to the Mykolaiv prison. There, the Mykolaiv KGB paid me six visits in a month and a week. That was far too much. They both coddled me and threatened me. The head of the department who was releasing me demanded that I not disclose my conversation with him. Because he would draw up a document about disclosing a state secret. I said: “And why did you speak to me about a state secret? I will never keep this secret. I do not recognize such secrets.” And he then says: “Supervision—starts from the prison gates.”

Many people, family, came to meet me at the prison, they brought a bus. But they brought me under prison escort all the way home.

And so it began. A whole year of administrative supervision with a warning: that no people should visit me, that there should be no guests. Well, what could I say to him: “You know what? I can’t refuse people entry—I have family, I have acquaintances. If you have a list of people who visit me, then give me an excerpt. I’ll stick it on the gate, a person will show up, and I’ll tell them: ‘Read it. You are not allowed to visit me, be angry or not.’ Otherwise, they will visit. Or else, pin tags on them, who can and who can’t. What is this—to visit or not to visit me?”

It ended with them tormenting me with their summonses. At first, they came to the house. They came in. No one was home, only my brother’s child. They conducted a search—no one was home, just a little kid. They left a summons on the table. And he’s clapping his hands: “Oh, uncle! We had guests!” I’m thinking, what guests on a Thursday? “And who was it, Ihorko?” “Some uncle came. He told me he’d buy me a fishing rod.” He was fishing with some stick in a basin where they had collected rainwater to soak laundry. And the man struck up a conversation with him, lured the child into the house: “Go on, show me where your uncle sleeps?” Well, what does a child know. I was sleeping in an empty room on a cot. He looked around, reached under the pillow—I figured. Ihorko says: “He wrote you a letter,” pointing to the table in the hallway. I look—a summons, to appear. We had argued with him before that. He had told me: “When you need to, just drop by, don't be shy.” I replied: “I have nothing to do here, and I will not be coming for your summonses anymore. Enough! You keep me for two hours, you take my time after work, and after seven o’clock I can’t go out on the street. This won’t do. First, why don’t you pay me for these hours you keep me here? Second, you have no topic. What can be discussed in five minutes, you drag out for two hours.” Some Colonel Knyazev came in: “We’ll come to your workplace.” I say: “Go ahead. I’m not stopping you.”

In short, it came to the point where he threatened me with prison again. I said: “For what?” “We’ll find something.” “What do you mean, you’ll find something? For what?”

The Case of the Fence

I put up some kind of picket fence. They came, measured mine, the neighbors’—everywhere. Mine was a total of 14 meters and 70 cm. Not even 70 cm, but by one picket. Well, my neighbor—I came home from work—says: “Some people came by, they were measuring your pickets.” I stopped and thought: “That’s it—Knyazev is at it again…”

And so it was. They measured this fence. But I didn't say anything. When they came, I said: “And where did you find so much fence at my place—70 meters?” A commission came, measured it—14 meters. I say: “Well, that’s mine. Without the gate. I made the gate myself.” They left: “You’ll report to [unintelligible] in a while and remeasure.” They took this very Ms. Nina. And I had to appear too…

Appear is one thing. But I had already put on my warm underwear. I thought it wouldn't pass so easily. And sure enough—they didn't let me out of the temporary detention cell.

V. V. Ovsiienko: That must have been in 1980, right?

Nina Ivanivna Moroz: That was 1980, the year of the Olympics. Mid-August.

V. V. Ovsiienko: So you were caught up in the “Olympic purge”…

N. I. Moroz: I am Nina Ivanivna Moroz, Petro Stepanovych Saranchuk’s partner. I’ve known him since 1964. We worked together at the Reinforced Concrete Products Plant-2. I started as a laborer. I knew Petro Stepanovych as an artist.

After his second term, after he served his time, we got together and lived together. Then comes the year of the Olympics. Petro Stepanovych wanted to go to Lviv. And there were some competitions in Lviv. He went to the director, asked the director to let him go on vacation. The director made a phone call somewhere. And they didn’t give him a vacation. Petro Stepanovych, I don’t remember if he was angry or not, but he wrote a sharp letter to the police. I didn’t see this letter; I only found out about it from his brother’s wife. She said that if she had known what he wrote in that letter, she would have stood guard by that mailbox for two days to get that letter out, so it wouldn't get to the police. I don’t know what he wrote there.

Before that, I was working as a foreman. I see that everyone is taking something. So I decided to take some defective posts, a truckload of concrete. Instead of the firewood we had a permit for, we got some of these separate, neat little planks to make a fence, because our fence had fallen down. And so I, as a foreman, used the truck twice. Well, not for its intended purpose. I brought them to Petro Stepanovych for the fence.

Before that, the director summons me. I thought he was summoning me as a foreman: the technologist is going on vacation, and now the director will tell me, “Nina Ivanivna, you will work as deputy shop chief while he’s on vacation.”

I enter the director’s office. I say: “Hello, Yevgeny Fyodorovich.” He says: “Come here,” and leads me to the Party office. I enter the Party office. Some short, bald man meets me. “Please, meet…” He introduced himself as Knyazev: “Let’s talk.” We started talking. He began to talk to me about Petro Stepanovych: “You know, you know… He has two nicknames. He’s a bad man. He’s this and that…” And I, of course, as a woman might… Well, I didn't want to. He started making proposals. My daughter was in an orphanage in Pohorilivka. He tells me: “I’ll send a car for you every Saturday, so it won’t be noticeable that you… But you watch who comes to see him, rummage through his papers. Well, and so that it’s not noticeable, a car will come, pick you up and take you to the orphanage to see your daughter. And you’ll watch him, and no one will suspect a thing.” I refused: “Oh, no. I can’t do that.” He then told me: “Well, if you don't want to do it the nice way, then don’t forget that if you just take one little misstep here—we will punish you.”

Time passed, and Petro Stepanovych received a summons. I was upset too. But nothing for me. And at the end of August, I’m saying this for a fact, I’m submitting the work reports to the chief engineer. Then the police come, take me, put me in a police van, and drive me to the police station. They take me to the OBKhSS [Department for Combatting Theft of Socialist Property] and start an investigation. They interrogated me, wrote up a report, and put me in what seemed like pre-trial detention. I look up—and Petro Stepanovych comes in. And that was the last time I saw him as a free man, when he came to give his testimony. I was released a short time later. Then we were tried together.

V. V. Ovsiienko: So both of you were tried?

N. I. Moroz: We were both tried. What, you didn’t know? I got a sentence too. I know this case for a fact.

V. V. Ovsiienko: Well, and how much did you get?

N. I. Moroz: I received three years at the construction sites of the national economy. My charge was “abuse of official authority, part two.” I was not under arrest. I served a year and seven months under travel restrictions—under supervision. And the most important thing is that when I came to work at the alumina construction sites, since I had a minor child, they didn't take me away because there was no place for women in the camp. And for the child's sake… Well, they often came to check on me. The police would come. I also had no right to go anywhere after ten o'clock at night. If I ever went to visit my mother, I was obliged to check out at the special commandant's office, and upon arriving in that city, to register, and to check out when leaving. And every Sunday I went to check in at the special commandant’s office. There was a section officer there.

Then I found an acquaintance. He looked at my case and said: “Yes, indeed, they gave you this sentence incorrectly.” And in general, everyone laughed that I was serving time on such a charge, for such a case. It was a matter of pennies, it was all fabricated. Very little had been taken, but they said they didn’t have a price list for those items, so they applied a coefficient of 1.3. And although I returned almost everything: those lintels and all… It was worth 100 rubles. But we still returned 70. It ended up being a matter of pennies for us. But the fact is that I helped, as everyone believes, to put Petro Stepanovych in prison…

V. V. Ovsiienko: Well, well, what they needed to do—they did. So, that trial was at the end of 1980? Sir Petro, how much did they give you then?

P. S. Saranchuk: Five and a half years of special regime.

They sent me to the special regime in Izyaslav, Khmelnytskyi region, which was in a former monastery. I stayed there until Stepan Pyskiv, a man from my village, arrived from Australia. He tried to get a visit with me, but they refused him. After that, he submitted a statement to Radio Liberty. They commented on his visit and my case. I think Shumuk also made a statement. No, Shumuk found out later from my letter… So after this Australian’s broadcast, they immediately grabbed me from Izyaslav and took me to Sukhodolsk, Luhansk region. Some authorized operative came there. He summoned me and asked: “Aren’t you tired of sitting? We can release you. You’ve already served half. But,” he says, “you have to write a confession.” I ask him: “What am I supposed to confess to? First of all, my case is fabricated, and second—I’ll serve my time.” But I also told him: “I'm not against it. But I'm an illiterate man, I can't write it myself. You need it, so you write it.” And he says: “I'll write it.” He started writing something, pushed some piece of paper to me. And I said: “Listen! You wrote it—so you sign it. Why are you giving me your letter to sign? I agreed for you to write a confession. So you sign it. It's your work. What, did I have a hand in it?” He looked at me and said: “You’re going to Mykolaiv.”

The Case of Disobedience to the Administration

Then, through some commission, they remove my special regime, replace it with strict regime, put me on a train—and transport me to Mykolaiv.

I ended up in the camp in Olshanske. There they started to press me: I didn’t do the work, I went to the wrong place, I entered the wrong area. Then in the evening, they took me to the medical unit, beat me, and accused me of breaking into the medical unit at night and beating up the orderly because he wouldn’t give me my medical history. And right there, they opened a case against me for attacking him. They put me in the isolation cell for three months.

This went on for a long time. I had only ten days left of my five-and-a-half-year sentence. My brother had already come to see me, because I had let him know to come and pick me up by car from the gates. I was afraid to walk to the bus stop alone. He arrived—and I was gone. He looked here and there, and they told him: “He’s not here.” “What do you mean, not here?” “He left.” “Where did he go?” “He went home or somewhere.” “But how did he leave if he wasn’t released?” Ten days left until release…

In short, a month later he found me in the Mykolaiv prison. They started an investigation against me for attacking the medical unit. They gave me three more years on top of the five and a half. For two months, they transported me to the correctional labor colony in the settlement of Lozivske, to a special-strict regime. A year before my release, the so-called “buyers” came—to hire workers. They needed specialists—locksmiths, molders—there was some kind of rush job. I signed up. They removed my special regime—and sent me to Sukhodolsk as a specialist. And I was already in my sixth decade, fifty-five and a half…

They brought me there, and there were representatives from the factory in the camp chief’s office. “What can you do?” “Whatever you say.” But I saw myself—something was not right. The camp chief says: “Well, okay, he's approaching sixty, where am I going to put him?” But they told him: “We don’t need clients like these.” They talked it over until it was decided that neither one of them needed me. But the camp chief says: “Will you do anything at all?” “Why anything? Whatever you say.” “Well, will you be a janitor in the factory yard?” “Well, why not. You said it—I’ll go.”

I waved a broom there until spring; in the winter I did clear snow, it's true. I walked around with a broom… I was also a gardener there. I sowed flowers. Among the flowers, I sowed dill and sorrel—greens for myself. Just for me, for soup. I served out my term and was released from there on February 28, 1989. They put me on a train. But I didn’t get to see my father. My father didn’t live to see me by two and a half months. In Sukhodolsk, they called me to the commandant's office and didn’t know how to tell me: “Don’t take it to heart. Your father has passed away.” It hit me hard; they took me to the barrack.

So in the spring of 1989, I was released. That was my last charge—“Disobedience to the Administration.”

V. V. Ovsiienko: That is Article 183-3. Finally, you definitively returned to Mykolaiv…

Finally—Free…

P. S. Saranchuk: Definitively is definitively, but they put me under supervision. I lived with my brother for two more years and had to check in for a whole year in the Zhovtnevyi district. I would come here, to my own house, and check in here. And why? Because I had nothing to live on, so I had to live with my brother.

V. V. Ovsiienko: Were you registered there too?

P. S. Saranchuk: No. I was registered at my own house, at 42 Svidna Street. I lived with my brother and worked there: we were building some dacha. Then I started coming home: I had to do something. The district officer at my place of residence took me under his supervision.

V. V. Ovsiienko: So your administrative supervision only ended in the spring of 1990?

P. S. Saranchuk: Yes. One year, and then they threatened another year because they didn't find me at home once.

V. V. Ovsiienko: I want to ask you: you were under supervision for a whole year. Did you show any civic activism—it was already the beginning of perestroika, independence was approaching? Were you in any organizations?

P. S. Saranchuk: I immediately joined Rukh. Well, what kind of a worker was I then? Oleksa Mot protected me from any kind of activism. Because it was like this: they call you here, you have to go there, why didn’t you come there? People didn't know my troubles. So Oleksa protected me.

V. V. Ovsiienko: And how did you celebrate your 70th birthday?

P. S. Saranchuk: The 70th birthday was celebrated on October 26, 1996. It was mostly relatives, at home.

N. I. Moroz: The seventieth birthday was at the DOSAAF hall. You helped, Ivanyuchenko from Rukh, and Vakhtang Kipiani. Mostly Vakhtang, it was a great contribution on his part.

P. S. Saranchuk: Well, that's when I joined Rukh, and the URP.

The great work we did—we raised two churches from ruins. Though, when I was in the hospital in Yaremche for three months, they cheated us with one church…

N. I. Moroz: St. Panteleimon’s Church.

P. S. Saranchuk: I came back—and other people had somehow taken that church into their hands. A priest. It became autocephalous. That’s on Sadova Street. Before that, the church was a club (it's a big church!). We did all the preparatory work. We restored the iconostasis, primitively, perhaps, but it was still done nicely. I made the iconostases in both the first and the second church. And now that church is a beauty. They’ve already raised its spire, its dome. Well, the work is still ongoing.

V. V. Ovsiienko: It’s of the Kyivan Patriarchate, right?

P. S. Saranchuk: Kyivan Patriarchate. What other could we have? There were some disputes about these patriarchates, and they somehow stole one church from me. But God be with them. Our success was great, a multitude of people comes. It was destroyed in 1934. They tore down its dome, converted it into a club. But the fence remained, a good location. Now many people gather there for Easter, for the Transfiguration. And in general, many people attend. It has been robbed three times already. Now, they say, they’ve found some thief who came to ask for forgiveness. He came to the church to ask for God’s intercession. I don’t know how it ended. It’s a legal matter.

Well, my work was interrupted by illness. I have pulmonary tuberculosis. A cavity the size of a five-kopeck coin on my right lung. But it's starting to heal. A third of it remains. They might discharge me from the hospital by the New Year. For now, they’re keeping me. But they already say I’m getting better. I’ve started eating. And I’ve put on weight. On my arms, the skin is still barely sagging here and here. I didn’t think I would survive… The doctors are treating me very carefully. Well, and I don't allow myself any unbecoming behavior there.

V. V. Ovsiienko: Sir Petro, you came to Kyiv for the presentation of Mykhailo Kheyfets’s three-volume work. It contains “Ukrainian Silhouettes” (3), where there’s a wonderful piece written about you. I am very grateful to you, and to you too, Ms. Nina, for deciding to come despite your illness. Because it is important that we Ukrainians honor this worthy man for such a good book about us. Thank you for coming!

N. I. Moroz: And thank you for having us and providing us with everything. If it weren't for you, we would have thought twice about whether to come or not.

V. V. Ovsiienko: End of Petro Saranchuk’s story, December 11, 2000.

Notes.

1. Danylo Shumuk, born Dec. 24, 1914. A political prisoner of Polish, German, and Russian concentration camps—a total of 42 years, 6 months, and 7 days of imprisonment. Finally released on Jan. 4, 1987, he left for Canada. In 2002, he moved to the city of Krasnoarmiisk, Donetsk region, to live with his daughter, where he died on May 21, 2004, in his 90th year of life. P. Saranchuk mentions his books: D. Shumuk. *Za skhidnym obriiem* [Beyond the Eastern Horizon].—Paris-Baltimore, 1974; D. Shumuk. *Iz Gulagu u vilnyi svit. Rozdumy pro zustrichi z ukrainskoiu diasporoiu i uriadovymy chynykamy ta dopovnennia do knyzhky “Perezhyte i peredumane”* [From the Gulag to the Free World. Reflections on Meetings with the Ukrainian Diaspora and Government Officials and an Addendum to the Book "What I Lived Through and Reconsidered"]. Vydavnytstvo “Novyi shliakh”. Toronto, Canada, 1991. 260 pp.; D. Shumuk. *Perezhyte i peredumane. Spohady y rozdumy ukrainskoho dysydenta-politviaznia z rokiv blukan i borotby pid troma okupatsiiamy Ukrainy (1921-1981)* [What I Lived Through and Reconsidered. Memoirs and Reflections of a Ukrainian Dissident-Political Prisoner from the Years of Wandering and Struggle under Three Occupations of Ukraine (1921-1981)], Kyiv: Vydavnytstvo im. O. Telihy, 1998.— 432 pp.

2. Meletiy Semenyuk—an insurgent from Volyn, a political prisoner. One of the leaders of the Brotherhood of Former UPA Soldiers. Died in 2004.

3. Mikhail Kheyfets. *Izbrannoe* [Selected Works]. In three volumes. Volume 3. *Ukrainskie siluety* [Ukrainian Silhouettes]. Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. – Kharkiv: Folio, 2000, pp. 124-135. Also: Mykhailo Kheyfets. *Ukrainski syliuety* [Ukrainian Silhouettes]. Suchasnist.— 1983.— pp. 179-195 (in Russian and Ukrainian); also: *Pole vidchaiu y nadii. Almanakh* [The Field of Despair and Hope. An Almanac]. – Kyiv: 1994. – pp. 296-319).