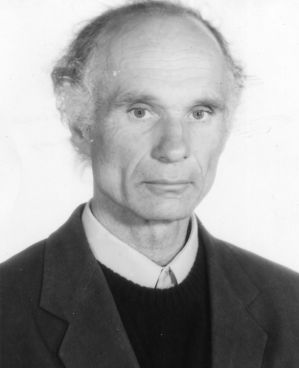

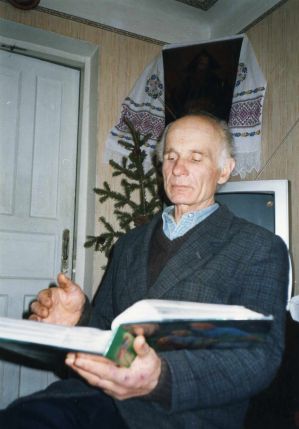

Interview with Dmytro Dmytrovych MAZUR

July 22 and August 7, 1998.

V.O.: Mr. Dmytro, please tell us about yourself.

D.M.: Any decent person, when asked about themselves, feels awkward and wants some justification. But we are mortal, and so we must say something about ourselves, because every biography is a part of our people’s history. Sometimes I get scared (like the great Herzen) that with my death, everything I know will vanish into Lethe. No one will know why events in Ukraine unfolded this way and not another.

I was born before the war, on November 5, 1939, so my entire childhood was marked by war. I remember the war. It was very shocking: the shootings, the combat, the Ukrainian partisans, the Soviet partisans who fought against the Germans and against the Ukrainian partisans. People often found themselves on opposite sides of the barricades. My soul was forged in this turmoil.

My earliest memories are the execution of a Soviet partisan, a battle between Ukrainian and Soviet partisans, a battle of Ukrainian partisans in Ustynivka, Malyn district, against the auxiliary police whom the Germans were driving into the attack (one German for every ten policemen). The Ukrainian partisans shouted:

“Brothers, surrender!”

The policemen advanced, the Ukrainian partisans opened fire with machine guns—and they all fell. The partisans approached, bandaged anyone who was still alive, and left. There was no such thing as finishing off the wounded. They were picked up by the Germans and other policemen who arrived later.

My entire future life was shaped under the sign of these events. They demanded an awareness of what was happening.

As early as 1946, I heard about Stalin’s crimes. A little girl—a bit older than me—told how they were transported by steamship for two months, and the dead were constantly thrown overboard. Two hundred people. She couldn't have counted them. She probably knew this number from the stories of other people. She said it was so frightening when they threw people into the sea. I remembered this story for the rest of my life.

And some 20 years later, the KGB tried to figure out why I became the person I am, and not someone else. That is, a decent person. And decent people are still not tolerated…

V.O.: And what is your family background?

D.M.: My parents were teachers. My mother, Olha Zakharivna Tkachenko, was from a peasant family in the village of Huta-Lohanivska, Malyn district, in the Zhytomyr region, and my father was also from a peasant family from neighboring Ustynivka. My mother was born in 1919 and died in 1990; my father was born in 1914 and died in 1991. After I returned from imprisonment, I buried them.

We were affected by Chernobyl and know all about that tragedy…

Life was hard. It broke some people, while others sprouted. Like the seed mentioned in the Bible. Of course, I didn't read the Bible then—it was forbidden—but I grew up under the sign of old Ukrainian folk culture. A friend later said that I was “ethnographic.” I never even thought that could be said about me. For me, it was normal to be surrounded not just by Christian, but by pagan-Christian culture. Fragments of it were still alive. Like a broken tree that still sends out shoots. Like a willow by the water. There were still beautiful wedding, Petrivka (St. Peter’s Fast), harvest, and ancient Kozak songs, even though we are far from the Sich. There were even some that have never been recorded anywhere. I failed to write down in time the folk song about Karmaliuk:

Уже б тая рушниченька була б не стріляла,

Якби моя Марусина правдоньки не знала.

The song “Beyond Siberia, the Sun Rises” is not a folk song; it is of literary origin.

I studied in an ordinary Soviet school, which offered very little. My parents moved from village to village, and this helped my development: new surroundings, new impressions, so I didn't become dull or standardized. Always new memories, stories about the Ukrainian partisans, who were still fighting with their last strength and their last people. The deaths of strangers, people I didn't know, helped me keep my soul alive.

I finished school in 1957 in the ancient village of Chopovychi. I only recently learned from an old woman that it has existed since the Princely Era. Academician Rybakov mentions the *hryady*—fortified places. That old woman from the village of Huta-Obodzynska said that the *hryady* were built by Greeks who lived in Chopovychi. She even showed me the place where a fortified point had been. That a fire burned there constantly and a guard was always posted. The ramparts stretch from the southwest, in the direction from Malyn, to the northeast, toward Kyiv.

This living history also influenced me. Just look around. I don't know how people live in America, where there was no Middle Ages, no ancient world… I was probably more fortunate than Americans.

The first significant event that formed me was the Hungarian Uprising of 1956. Soldiers returned from there and told how they drove tanks through crowds filled with children and women… Even then, the teachers were dissatisfied with me as an “anti-Soviet.” They even called my mother in. But it didn't go beyond the school. And even then I wasn’t afraid of it.

After finishing school in 1957, I worked on a kolkhoz. Following family tradition, I suppose, I went to the Zhytomyr Pedagogical Institute. I enrolled in 1961 but studied with an interruption. There was Khrushchev’s military draft. I was called up from my second year. I served less than three years because I developed hypertension. I returned as a third-group invalid. I served in Crimea and in Stalingrad. It was a wasted time. I would have been better off studying.

I returned to the institute in 1965 with the understanding that the struggle had to begin. One could not remain silent. Ivan Dziuba also helped me. I heard about him, went to Kyiv, and visited the Dnipro publishing house on Volodymyrska Street. He advised me: one must not remain silent. If you don’t stir things, they will grow moldy. (A person needs the advice of others, even if they consider themselves wise).

So I stood in opposition to them. At the time, I believed (and still do) that you need scandals to move things forward. Because silence is stagnation. I began educational work among people who should have been educated themselves. They were village boys and girls studying at the pedagogical institute. They knew very little about Ukraine and were slowly showing an inclination to become not teachers, but village bureaucrats (unfortunately, Ukrainian intellectuals easily become bureaucrats). There were conversations, debates, sometimes very heated. Sometimes I was met with indifference. But there were some results. The graduates went on to schools and influenced their students.

My first summons to the Zhytomyr KGB belongs to this period (around 1966). They said: there is a lot of talk about you, so we want to know who you are. We are studying you. I wasn’t listening to Radio Liberty at the time, and samizdat literature did not reach me.

V.O.: You hadn’t read Dziuba’s work *Internationalism or Russification?* at that time? It has since been published as a separate book.

D.M.: Even now, in our democratic times, I can’t get that kind of literature. I was shaped by life, not literature.

V.O.: Did Oles Honchar’s *The Cathedral* come out during your student years?

D.M.: I graduated from the institute in 1967. With great difficulty. I just couldn’t pass Marxism-Leninism. I even went to the Ministry of Education. Of course, I ran into a KGB officer there (I found this out later). He told the rector over a direct line: “Don’t make a scandal. Let him stop traveling around Ukraine. Give him a passing grade.” Rector Oslak was a good man. He didn't testify against me later either. But he was dependent on the circumstances of the time. It wasn't he who persecuted me, but the former retired officers who headed the department of Marxism-Leninism. They didn’t want to give me even a “satisfactory” grade. Because I was already under surveillance by then. I was not cautious: I once asked a lecturer, Leonid Pyvovarsky, if it was possible to read Hrushevsky’s *History of Ukraine-Rus’*. He was the first to report on me. That’s how it began. The very desire to read was a crime… For the provinces, this was great sedition. Like any stubborn Ukrainian, this didn’t scare me; it even amused me and gave me energy. Even I need to be stirred up sometimes… I became even more interested in Ukrainian affairs and spoke about them more.

In 1968, Oles Honchar’s novel *The Cathedral* was published. With a print run of about 110,000. A fine book.

V.O.: In the January issue of the magazine *Vitchyzna*, with a circulation of about 30,000, and almost simultaneously in the “Novels and Novellas” series—100,000 copies. There was also a hardcover edition from Dnipro, but very few people got it. I managed to buy one.

D.M.: They began to attack it. In other words, to create a scandal. Well, if you want a scandal, you'll get one. In the village of Riasne, Yemilchyne district, where I was already working at a school, I received a letter from someone at the institute saying that I should come to Zhytomyr because a week of Ukrainian culture was beginning in the Zhytomyr region. Andriy Malyshko, Oles Honchar, Lyubov Zabashta, and some literary critics were coming.

V.O.: That would have been around spring 1968. They didn’t touch Honchar until after April 2, because that was his 50th birthday. But after April 2, they started pecking at him.

D.M.: I didn't read newspapers, but the guys told me there had been some attacks on *The Cathedral* in the press. They said: when the meeting happens, maybe you'll get a chance to speak. They knew me and asked me to write a speech. I wrote one. We timed it—about 9 minutes. And it was delivered. The meeting took place in the auditorium of the pedagogical institute. I don’t even know the young man’s name… They wouldn't have let me speak. They needed a student, and I was no longer a student. He spoke last. We didn't know what the reaction would be. They could have just ignored it. But those who needed to notice, noticed: a KGB colonel was sitting in the first row. They rarely wear uniforms… I met him later, but I don't remember—and don't want to remember—his name. There were about 500 Ukrainian students in the hall and a couple hundred Uzbeks. They were studying Russian at the Faculty of Russian Philology in Zhytomyr at the time… I don’t know how they use it now… They already understood Ukrainian as well. Many people were standing. I listened to the speech and then went home.

A scandal erupted. I wasn’t interested in who started it. But everyone began fighting among themselves. First of all, the lecturers. Some said the speech was correct, while others called it a “nationalist sortie.” The whole of Zhytomyr was in an uproar. Surprisingly, people even started using the word “Ukraine.” There were many old local residents in Zhytomyr who were far from approving of the language shift, the closing of Ukrainian schools, the influx of colonizers, and the settling of the city center by retired military officers—everything that was destroying their way of life. They reacted positively to these events. They hadn’t heard the speech, but they knew that something had been done in defense of Ukrainian life, the Ukrainian Church, and Ukrainian customs. People talked about it for several years.

V.O.: And what was the fate of that student?

D.M.: They allowed him to graduate from the institute because they knew the speech was not his own intellectual property. There were no other cases against him. They had a talk with him. He didn’t say who wrote the speech. They found out later. But then the lecturers began to be dismissed. Some submitted a letter of resignation “of their own volition,” others were fired… The scandal forced people to think. And that was a good thing.

My presence at the meeting was noticed. They began to watch me even more closely, although they didn't immediately establish that I had written it. They summoned me to the Zhytomyr KGB and interrogated me for three days. They let me go at night. I had a “tail” following me, but I would shake it, so they got angry because they didn’t know where I was spending the night. They yelled at me, threatened me… I sent a record of those conversations to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. And then this event, long forgotten, it seemed, was constantly stirred up.

According to the unwritten laws of the time, I had to submit my resignation “of my own volition” from the school in Riasne. I found a job in the village of Bilka, Korosten district—it’s adjacent to the one where I previously taught. When, during a “Lenin lesson,” I spoke about the Holodomor of 1933 and the repressions of 1937, about the fact that several dozen people from this village had been shot (the students later said: those were our grandfathers)—I was fired from my job as “professionally unfit.” This was in 1971. The dismissal document was prepared by the school principal and approved by the district department of education. I remember some of their last names, but what for? My specialty is Ukrainian language and literature, but in Bilka I had to teach German. As if I were teaching it poorly… Then they should have given me Ukrainian…

In addition to this turmoil, I also had hypertension, so I returned to my parents in Huta-Lohanivska. I helped them. In 1973, I was accused of “parasitism” and a visiting court from Malyn in Huta sentenced me to one year of corrective labor. I appealed the court's decision and waited. I even wrote that if the appellate court found the decision to be just, I would start the work they assigned me.

Why didn’t I take a job before that? There was a moral barrier. After all, in class, I didn’t just talk about the repressions of 1937. I spoke about what was happening in the village at that time. How they forced people to vote for candidates for deputies… And at that same time, my neighbor froze to death in her unheated house. Her stove was broken, and her son had been drafted into the army. He came, buried his mother—and had to go back to serve… I said a lot of things, I won't recall them all. I did nothing and could do nothing. It was only a word. But they did not forgive me for this. I said: this cannot be tolerated. She was my neighbor nearby. I didn't know anything yet in that village. I hadn't seen anything like that before. I was simply obligated to talk about it. It was necessary to stand up for these helpless people who cannot defend themselves. And talking about the Holodomor was absolutely forbidden back then. Even our President Kravchuk said he didn’t know about the famine in Ukraine. He was being disingenuous…

This horrifying event shook me once again. I said then: do something, at least for this village, and then I will take any job you give me. If not, then sentence me. Or give me a teaching job. I had only been teaching German, not Ukrainian. The judge was local, from Malyn. He's still a judge… I wrote: if the Zhytomyr appellate court confirms the fairness of the sentence, I will go to forced labor wherever I am sent. But I have not received the decision of the appellate court to this day.

I think it was on February 28, 1973, that I was summoned to Malyn. I thought they would announce the appellate court's verdict, but instead, I was taken into custody. The trial lasted five minutes (the judge was Stelmakh, he still works there). I wasn't given a final statement, no one was allowed into the courtroom. They sentenced me to a year of imprisonment. This was a clear violation of Soviet law. If they had served me the appellate court's decision and I had refused to work, they should have replaced the year of corrective labor with four months of imprisonment—one day of imprisonment for three days of corrective labor. But on February 28, they took me to the investigative isolator in Zhytomyr and held me for over a month.

They began to collect materials for a political charge. My cellmates told me that they were being forced to write things about me. They said, we signed it because we’re afraid… Only one of them (a “vor v zakone,” a professional criminal) did not sign. Then, 6 years later, they were summoned to court as witnesses…

I was transported by prisoner train to the Sumy region, to the village of Perekhrestivka, near Romny. It was a general-regime camp. I don't remember the first days of my stay there because I was running a high fever. There was no work for a while. I would just go out for the roll call—and then collapse. Sometimes I would collapse before even reaching my bunk.

An officer from the Zhytomyr KGB came there. He admitted it himself: he was gathering materials on me. To convict me without releasing me. But one of the inmates told me: “You did nothing to me. I don’t want to lie about you. They forced me. Let me write a retraction, I’ll give you a copy—and what will be, will be.” Maybe that saved me. The prosecutor summoned me and said that they were giving me a warning but would not put me on trial. I had to sign for it.

V.O.: This was a warning under the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from December 25, 1972.

D.M.: I knew that after this, sooner or later, they would arrest me. But I was not going to change my views or give up my educational work. That would have been indecent. After my release, I worked for a while in Malyn at an experimental plant, as a loader, a concrete worker, on the construction of a paper factory workshop.

I was arrested before the 1980 Moscow Olympics. And then the Afghan War started. I realized that this was the beginning of the collapse of the USSR. Amalrik had already written about this—“Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?” The Russian Empire faced the inevitability of collapse in the Crimean War, fell apart after World War I, and then reassembled itself as the USSR. They would not be able to win a war against Afghanistan, where the British and the Soviets themselves had been bogged down after the revolution. Judge Biletsky’s first question was… Did he also preside over your trial?

V.O.: Yes.

D.M.: The first question was (they read my letter): “Why do you believe such a fate awaits the Soviet Union?” But the time when I spoke frankly was past. I said nothing in response. My lawyer warned me that I would get 6 years of imprisonment and then exile. I wasn't much concerned with what the term would be. I had already decided that a decent person—I repeat this word, because it is definitive in our times—should not receive a short term. I was not going to ask for anything.

V.O.: And what was the pretext for the arrest? When and how did it happen?

D.M.: No pretext! Everything was fabricated. I hadn't even had a chance to say anything about the Afghan war…

V.O.: The Afghan War began on December 29, 1979.

D.M.: And I was arrested on June 30, 1980. When the Afghan war started, I discussed it. Like everyone else. These were everyday conversations. Who heard what, where, and when. It was not some kind of agitation or propaganda. They just needed someone to put away. One KGB officer told me that they hadn't had a person they imprisoned just for their words in a very long time. Later they said: the one who handled your case—he was earning his pension on you. Kosyak was his last name. And Major Radchenko, the head of the investigative department, in a moment of candor (or perhaps not wanting trouble for himself), said: “We will kill you. We don’t need cunning people like you. We will kill you under the pretext that you are inclined to terrorism.” He was simply warning me. This was in the interrogation room. I was being recorded on a tape recorder, but it was turned off at that moment. It was supposedly a private conversation.

It was very difficult for them to build a case against me. They said that I had said something somewhere. They arrange face-to-face confrontations—the person confirms nothing. “Well, planes were flying, and he said: they’re flying to Afghanistan.” Indeed, bombers were flying. I knew them because I had served in the air force. Or: “He talked about the fighting in Afghanistan.” Even the radio was talking about that.

I knew they could imprison me, but I didn't think they would look for such pretexts: “agitation for the purpose of subverting the Soviet regime”… I wasn’t afraid. I was secretly laughing at them.

V.O.: How did they arrest you?

D.M.: The arrest was connected with your arrest in 1979. You may not know everything. Academician Sakharov spoke out in your defense, and talk about you began. The KGB men found out that Lina Borysivna Tumanova had come from Moscow to the trial in Radomyshl (she was later arrested). I met her in Kyiv, and showed her that we had a “tail.” They were glancing at us and whispering among themselves…

V.O.: You really “lit yourself up” at that trial. And you had visited Oksana Yakivna Meshko before that regarding my case…

D.M.: I wanted to get acquainted with decent people who were doing something. I did not apply to join the Helsinki Group for the reason that I didn't attach any importance to this formality. I visited Mykola Rudenko, spent the night at his place, visited Oksana Yakivna—a very noble person. The KGB men later told me: “Whatever happens, you're always there.” It was funny: and why shouldn't I be there, where something good is being done? A person should be active, know everything. This is normal for me.

They came with a search warrant when I was not at home. I was summoned to the kolkhoz office at that time so that I wouldn't be present during the search. They found your letters, my letter in defense of Dziuba, or something. Your text, “Instead of a Final Statement.” They called it very anti-Soviet. But those were the words of a beaten man who is saying that I am not the one who should be beaten. And a few days later, on June 30, they came and took me away.

The investigation was led by Radchenko. He is a bureaucrat, a very vicious man. But he did warn me about the murder threat… The verdict is preserved. It says there that I talked about the fighting in Afghanistan. That life is hard for kolkhoz workers. That Ukrainian schools are being closed (the prosecutor at the trial said: “There are still Ukrainian schools in Zhytomyr”). This was incriminated as undermining the foundations of the Soviet regime. Not even “slander,” but “for the purpose of subverting and weakening the Soviet regime.” Article 62. Up to seven years of imprisonment and five years of exile.

Investigator Lyabakh really did not want to conduct the investigation against me. He said: “Denounce me.” Because I had told him that when he returned to his home in the Ivano-Frankivsk region, they would peck out his eyes… There was also some Gorodnichy from the Sumy region—he later handled Feldman's case. He didn't question me, just was part of the investigative team.

What was there to imprison me for? That, with long-held naivety, I tried to defend Oles Honchar? That I wrote a letter in defense of Solzhenitsyn when he was expelled from the Writers' Union? They dropped the latter so that the case would have a purely “nationalist slant”…

There were many interrogations about nothing. They would say: “Say something against yourself, so that we have material. We’ll give you less time. As it is, there’s nothing to charge you with.” Well, fine, I’ll say that life was good for the kolkhoz workers without pensions. Life was good during the Holodomor. During the executions… People in the village talked about this then and still talk about it. What does “subversion” have to do with it? Why did this fall on me specifically? This fact itself surprised me.

I understood that this regime was foolish. It was working against itself, to its own destruction. They are foolish—and that was the extent of my thoughts about them. What is there to say about them? They are foolish. They are harmful to themselves. They disappear very quickly into the earth—without any trace. And in my character reference, they wrote: “Very cunning.” They would read this to me at prisoner transfer points. If only they had once said that the man understands something… “Cunning”…

The trial lasted three days. I couldn’t see if anyone was in the hall. They made me sit with my back to the audience. Soldiers stood at my side and wouldn’t let me turn—they kept pushing me. I knew what the sentence would be. I did not defend myself—who was there to defend myself before? I answered what year I was born… And when they gave me my final statement, I said that, of course, I was guilty, but I didn't know of what. I did not want to make any programmatic speeches for purely practical reasons. I knew that the guys were sitting in concentration camps. I would have a visit with my mother and I would pass on what needed to be passed on to whom.

During the trial, I had very high blood pressure. On the last day of the trial, during the lunch break, they gave me some kind of drug with my food, which made it difficult for me to take a step, to open my mouth, and to speak. I have never been in such a state again. In the camp, the guys told me the names of those pills. Back in my cell, I want to pick something up—I can’t. I want to move, to stand up—I can’t. I want to say something—it's hard to pronounce a word. Then it passed. They must have slipped something into my food. Maybe they were afraid I would say something. For example, a friend wrote to me from Kazakhstan that his investigator told him: “People like you should be killed along with your children.” I replied to him that one must not say such things, that it is outrageous… This ended up in my verdict. This outrage—that I didn’t want the children of political prisoners to be killed. I wrote about this in my appeal. I received no answer. They showed it to me, I signed for it—and they took it away.

They transported me by prisoner train. In Ruzayevka (Mordovia), they threw me into a cell with common criminals—a mix-up. In Russia, their Article 62 is for “parasitism,” or something. Then they moved me to a separate cell. There you could communicate with the neighboring cells through the pipes. I sang Ukrainian songs to some girls. They were charmed, but said: “Why are they so sad?”

I was brought sometime in early March 1981 to Mordovia, to Barashevo, the third camp. There were good people there… A monarchist by conviction, Vladimir Osipov. Yuriy Badzo from Kyiv arrived. From Kharkiv, Yevhen Antsupov (now deceased, may God rest his soul. He died in Frankfurt am Main. He managed to write several books. He wrote: “I am as far from an anti-Ukrainian position as I am from the stars.” Not all Russians held such a position regarding Ukraine). Mykola Rudenko was with us. His wife was imprisoned in the same camp, just a few fences away. You couldn’t see her, but if you shouted loudly, you might be heard. That's why Rudenko was transferred to the Urals.

The guys were glad I arrived because they didn't know what was happening in Ukraine. I said that I didn’t know either, but when I started talking, they said: “Oh, you know so much!”

I did what I had planned. Whatever they wanted to pass on, I did my best to convey through my mother. Then some very fine young guys came from Latvia, who had no contact with anyone. Jānis Barkāns and Zaiņis Balodis. One from the military, one a civilian. I passed on materials about them. A man from Latvia came to my mother, took them to Moscow, and from there they were passed on further. The Latvians were very pleased that the news spread all over Latvia. There was a lot of noise. People found out what fine people they had sitting in prison. This didn't happen often. It’s hard work. But someone had to do it. And it bore fruit. People got information about why they were being punished.

The work in the camp wasn't hard, but it was harmful: sewing work gloves. A lot of dust from the old material. It would clog your nose and mouth—you couldn’t breathe. Sometimes I wanted to go to the punishment isolator, to freeze, to suffer from hunger, but not to breathe that air. I was in the punishment cells often. I didn't hide what I thought there either. I could call the section chief a fool. There was a Ukrainian chief there, a decent enough person, but reports were filed against him and he was removed. They put a Russian in his place, whom I called a fool. He took revenge on me. A KGB man from Zhytomyr came and together they asked the workshop foreman to write that I was a bad worker. He was a Russian. He said: “I have never had such a good worker. I will not write that.” A kind of courage that Ukrainians often lack. So they found a guard, Trifonov. He wrote that my bedside table was messy, or my bed was not made correctly… They often put me in the isolator—and for a long time. The last time for 9 months.

V.O.: Was this the PKT? Because the ShIZO is for 15 days.

D.M.: It was the punishment isolator. The 15 days would pass—Trifonov would come and say: “There’s a spider web in the corner.” A soldier’s reason…

V.O.: When I was in Mordovia before early 1977, there was only one punishment cell for three zones—in Lisne, in zone 19. Did they take you there?

D.M.: No, they built a punishment cell in Barashevo on the spot where they had executed believers. The political camp in Lisne was liquidated (it became a criminal camp).

In 1983, the KGB man from Zhytomyr said: “There is a lot of talk about you. Where can I find someone to convince you to write a plea for a pardon?” The section chief said: “I have nothing against you, but you’re going to Ukraine. Let them have a talk with you there.” In the summer, they took me to the Zhytomyr prison. Some low-ranking officials tried to talk to me, but I remained silent. They realized that nothing would come of it. I was there for about ten days or two weeks. I fell ill there because a diesel engine was running under the window and the fumes were coming into the cell.

They would put all sorts of people in my cell, who admitted they didn't want to inform on me, that they had their own sentences to serve. One of them, who was in for speculation, told me that he had had a conversation in Crimea with a Jewish man who loaded fuel rods at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. He had been terribly irradiated and was undergoing treatment. He told my cellmate that Chernobyl was bound to explode because the fuel rods had been loaded incorrectly. An explosion was inevitable. Even before the graphite shield was in place, they started the reactor, and the workers didn't know they were being irradiated. I thought they were provoking me. I had to verify it. But I fell very ill…

I returned to the zone barely alive. I started to check the data on Chernobyl. It turned out to be true. I had to do something with this information, but there was no opportunity for a long time. I understood that if there were accidents in the US, then ours were much larger and inevitable. But I couldn't imagine their scale. When Gorbachev came to power, I wrote him a letter. More than one. Around Constitution Day in 1985 (around October 7), a representative of the Zhytomyr KGB arrived and ordered my isolation by any means (the workshop foreman told me this). Another inmate came and said: “Don't ask me how I know this, but you will soon be put away, and for a long time.” (He now lives in one of the not-quite-democratic countries of the CIS, so I won't name him, to avoid any trouble for him). Two days later, I was isolated. They kept extending my time in the punishment isolator every 15 days. With all its attributes: hot food once every two days, no walks, no bedding, no hat…

I wrote another letter to Gorbachev. They didn't send it, but the head of the KGB directorate for Mordovia came. He read my letter. He said: “Write to the prosecutor.” But I didn't write, because I saw it was hopeless. They told me directly that my letters were not being sent out. I was dealing with fools who were hastening the demise of their own empire, which they were supposed to be protecting.

On June 30, 1986, I was taken directly from the punishment cell to exile in Siberia. The journey took about a month. Sverdlovsk, Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk, Ulan-Ude, Zaigrayevsky district, Novaia Bryan’.

V.O.: That’s where Vasyl Lisovyi was in exile before!

D.M.: And Yuriy Badzo. They threw me out hungry, cold, without a kopek to my name. I starved for a long time. I borrowed money from my supervisor for a telegram to have money sent to me. Until then, I had eaten almost nothing. And I was already exhausted before that… I didn't know I had the right to go to the district executive committee and demand 30 rubles.

When they settled me in a dormitory and put me to work, I saw that I would soon be beaten. They housed me with the secretary of the Komsomol organization, Kuzmin. He kept harassing me. He would come home drunk every time. I called the local KGB and asked for a different job and a different place to live. They refused to meet or talk with me. In other words, they set me up intentionally. That Komsomol member beat me up. He broke both my arms and gave me a severe head injury, broke the bridge of my nose. I was bleeding profusely and ended up in surgery. I wrote to the prosecutor, but he didn't react. Only the police chief detained the hooligan for three days. They housed me again in the same room with the same Komsomol member. He, with me being helpless and with broken arms, would drag me out onto the balcony and threaten to throw me off. He really would have thrown me… He would have said that I fell off myself, and the case would have been closed. The prosecutor did not react—and I had to run away. I escaped. Sometime in the autumn of 1986.

V.O.: Where did you escape to?

D.M.: I ran away home, where else. I was helpless, anemic, couldn’t do anything, my arms just hung…

V.O.: Did anyone see you in the village?

D.M.: Some people in the village saw me. Then I was in Korostyshiv, at my friend Ivan Borovsky’s place. About two months passed. Winter began. I was arrested in an apartment of a woman in Korostyshiv. They gave me a year in a criminal camp, as was prescribed by Soviet law. The camp was in the settlement of Solnechny, I don't remember the number, near Ulan-Ude. Two colonels from the Moscow KGB came, gathering information on me. As if they didn’t know enough already… But mostly they drank vodka. They demanded that I write a plea for a pardon. I refused. It came to the point where I became the last political prisoner of the Soviet Union… Badzo and Lukianenko were in exile then, it was easier for them. Then Gorbachev went to America, and there they asked him about me. Because that's when you, Mr. Vasyl, raised a fuss about me…

V.O.: Yes, I was released on August 21, 1988. I went to your mother's place in Huta-Lohanivska, asked her questions, and read your letters and the verdict. In September, I went to Lviv. The Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners, headed by Mykhailo Horyn, was already active there. He told me: “You know the most about Mazur, so you should write.” I wrote a page of text by hand and sent it as a phototelegram to Gorbachev. A copy, of course, went out to the whole world.

D.M.: At that time I was in a tuberculosis prison and also fell ill with jaundice—viral hepatitis. It was very difficult in that prison. People died almost every day. Essentially, there was no treatment… As a result of that uproar, they isolated me—and it got a little easier. They released me on December 7 or 8, 1988. The same day as Badzo and Lukianenko.

V.O.: It must have been under the same decree.

D.M.: At home, my father was paralyzed, and my mother was sick with cancer. I had to fulfill my filial duty. I buried them… I tried to get a job as a teacher, but they wouldn't give me one. I went to work on the kolkhoz. When they stopped paying, I stopped working. I run my own small farm. I live alone. Not married. For now… I have a brother, Viktor, a little older than me, who now lives alone. My sister Halyna had to move all the way to the Tyumen region—because of me, she was denied both work and housing.

I joined the Helsinki Union, then the Ukrainian Republican Party. In 1996, our Malyn organization joined the People's Movement of Ukraine (Rukh). I was nominated for the regional council, but I had no money to travel to meet voters. They elected someone else. He immediately got caught up in theft. He was kicked out—after many publications in the press. They elect those who have more money, not decent people… That’s how we are. But I hope that everything will be all right.

V.O.: We are continuing our conversation on August 7. Mr. Dmytro, last time we were in a hurry and missed a few things. We need to clarify and add to it.

D.M.: Despite the haste, I was being a little cunning. I didn't want monotony. I didn't want to complicate the essence unnecessarily. I didn't mention my second escape from exile. By then, I was already sick with tuberculosis. When they threw me out into the cold again in that Zaigrayevsky district… There was nowhere to live. The disease was progressing. I had no choice. For a time, I stayed with good people, Russians, also former inmates, who had been imprisoned in Stalin's time. But due to lack of money and illness, I had to leave to save my life. I don't know if it's ethical, but I had no other way to save myself.

V.O.: Let's clarify when the first and second escapes were.

D.M.: The first was in the autumn of 1986. It was still warm.

V.O.: So, two months “on the run,” a year in prison, released in the winter…

D.M.: I think it was December 1987. I could be mistaken. There were severe frosts. I didn't stay with those people for long. They were very poor people.

I was literally freezing—not a single dwelling for 20 kilometers. The Mordopovsky bridge—they were guarding it. It's a large bridge—the highway to Vladivostok runs over it. They gave me shelter. I lived with them for a few days. I seemed to recover a little. But I couldn't stay, because food was very tight for them.

V.O.: So they didn't provide you with housing there?

D.M.: No, they brought me to the district center—and said go wherever you want. I set off at random and almost froze to death on the way.

V.O.: And what were your relations with the authorities then?

D.M.: The police were not hostile to me. They never treated me with hostility. But everything depended on the KGB. And the first time, I wasn't planning to start an uprising in exile… The authorities simply didn't want to deal with me.

V.O.: But this was already “perestroika”…

D.M.: “Perestroika” hadn't reached Siberia yet. They hadn't heard of it there. Things were happening in Moscow, in the center. But there they understood it backwards. I remember when something was said on the radio about needing to take some measures, they understood it as needing to “tighten,” to “turn the screws.” So, the second escape was sometime in early 1988, in the winter.

V.O.: How did you escape?

D.M.: They were, of course, watching me, but they lost my trail. I got lost myself in those vast spaces. Buryatia is very large. Its territory is like Ukraine's, but the population is only 1.1 million. The districts are as big as our regions. When I found myself in the middle of the taiga and didn't know where to go, I went at random. I walked about 15 kilometers and came across a cabin in the forest. In the forest, but there was a road. I knocked. I said, I'm freezing. They opened the door and welcomed me warmly. They treated me with what they had. They told me their story. A woman named Nastya. Her husband, I think, was Hryhoriy, their son was Serhiy. Baba Nastya told me her life story, typical of the 1930s. Her father, a Tatar, was the head of a kolkhoz. Her mother had died. There were three children. The father wanted to remarry. He went to some woman, and she said: “I don't need your children. Do what you want with them.” She took Nastya's younger brother, led him into the taiga, tied him to a pine tree—and he froze to death. She brought the other sister to the water and drowned her. And I, she says, hid in the dog's kennel. The dog would bite me, I would give it my hand, it would lick it and then leave me alone… (When Nastya was telling this, I said that I had almost frozen to death too…) She said, when I was 12, I took a knife and cut my stepmother’s throat, like a dog's. They gave me 10 years, she said. I carried railway sleepers together with political prisoners (as they are called now), with Lenin's comrades-in-arms. Later she saw one of them on television, a Jew by nationality, and said: “Oh, he was in prison with us! I knew him. He told us a lot about Lenin, with whom he was on friendly terms.” So that’s the kind of story…

Because of their poverty, because of my illnesses, I had to leave and save myself.

V.O.: But you didn't have money for the train…

D.M.: My mother sent me money. Later, when they interrogated me, they said they had seen me sending a telegram. And how I traveled. I had little money, so I didn't travel only by train. The highway runs across that Mordopovsky bridge. There's a lot of traffic there. Even cars from Chita to Moscow. I "voted" [hitchhiked]. Some car stopped—the driver was bored driving alone. We drove for a very long time. But I needed to eat something. I didn't want to ask him for anything, so I got out of the car, got on a train at some small station on this Trans-Siberian Railway, and traveled via Kharkiv home.

The situation at home was difficult. My mother was fading, my father was bedridden. She was terribly exhausted taking care of him. My health was getting worse and worse. My chest began to cave in. You could just feel your lungs withering. To save myself, I decided to go somewhere south. They caught me in Mariupol. They "figured me out" by my appearance. I was terribly thin. I didn't know this, as I hadn't looked in a mirror. But they looked at me and pointed their finger: this one must be detained. There was a police sweep at that time: there was a Khrushchev-era penal labor colony nearby. I didn't know this. So they detained me by chance.

V.O.: And how long were you at liberty this time?

D.M.: Not long. I spent a little over a month in Ukraine. When they detained me, it was still winter, sometime at the end of January. They transported me back by plane. In Mariupol, they kept me in some cell where I was suffocating. It had forced ventilation. If the guard on duty forgot to turn on the fan, there was no air to breathe. I would lose consciousness. The inmates would start pounding with their fists, shouting: “He's dying!” They would turn on the fan, and I would come to. They put me on a plane in Mariupol. In handcuffs. To Moscow, then to Ulan-Ude. Two guards accompanied me. They didn't know who they were transporting. They were terribly surprised when I told them. They said that foreign radio stations talk a lot about people like me (they were from Moscow). The guards began to treat me more leniently. They saw that I was no criminal. But they kept me in handcuffs. We flew over snow-covered Siberia all the way to Ulan-Ude. We landed somewhere. From Ulan-Ude, they took me in a paddy wagon to Zaigrayevo. The district court gave me another year. They said that it was all lies, that I hadn't been beaten, that I hadn't complained anywhere, that the prosecutor knew nothing, that I wasn't sick… They had destroyed all the documents about it, and they had taken all of mine too…

By the time they brought me to Buryatia, Kuzmin, the one who beat me, had already been stabbed to death. He had attacked someone else. So they provoked a new murder. They were probably afraid that Moscow would uncover it. They hardly needed any scandals. The man who killed Kuzmin was tried for murder. I asked to be a witness in that case, but they did not summon me to the trial. The man who killed Kuzmin in self-defense got 7 years. We were later in the same camp. He said to me: “Why didn’t you kill him? You would have gotten less time.” “And why didn’t you demand my presence at the trial?” “My lawyer told me not to.” And this lawyer was the prosecutor's wife. It was not in her interest to summon me to court.

It was at this time that they put an informant in my cell—a man sick with open-form tuberculosis. Even though I was already completely ill.

So they take me in a paddy wagon to Ulan-Ude, to the same strict-regime camp. They say, we know you have tuberculosis. They sent me straight to the tuberculosis ward of the camp hospital—separated from the zone by barbed wire. That strip was not a firing zone, so the inmates would crawl back and forth. There I also got viral hepatitis because there were so many sick people there. There was no isolation from them. We bathed in a common bathhouse, drank the same water. I got infected from them. It was terribly difficult—with tuberculosis, after the beating… The doctor said: “We need to save you, or your liver will fail.” They put me on an IV drip. The doctor was attentive to me. He said: “They’re talking about you. You will be released soon.” He also said: “I’ll lock you up so that no one enters your ward. It will be better that way.” They isolated me. The window was open, though it had bars. But no one bothered me. In those last months, it was tolerable.

The whole time, two colonels from Moscow were in the zone, who were dealing with my case and drinking vodka. The cell plants who talked with them told me this. These cell plants wrote reports on me. At first, they would give them to me and say: “If they allow 15 rubles for the camp store, I’ll share it with you.” But these colonels told them: “No matter what you say to him, he won’t tell you the truth.” They were not very interested in me. They drank vodka because they had money for their business trip. It was already the collapse. Nobody needed anything anymore. Whether you were a criminal or not—formalism reigned everywhere. And all this was called “perestroika.”

Then Gorbachev went to the US (I was told later that they asked him about me there). He stayed in the US for only one day, because the next day there was an earthquake in Armenia. He returned. That same day, a telegram came from Moscow about my release. But they released me the next day. I was told that this was connected with Gorbachev's visit to America. He was reprimanded for my imprisonment.

V.O.: Your documents say you were released on December 9, 1988.

D.M.: And Badzo and Lukianenko were released on the 10th. Because they were in exile. But it was the same decree. When they released me, there was no surveillance on me. They brought me to the station: “Can you find your way, get a ticket yourself? I have to go on my own business.” He gave me money for a ticket to Moscow: “I don’t have any more.” I had some change of my own. I got to Kyiv, and from there I took a commuter train home.

V.O.: When I was told that Dmytro was already home, I immediately went to see you. I was walking from the highway to Huta-Lohanivska, and we met on the road in the forest. A light snow had fallen…

D.M.: I don't remember your visit at all. I was in such a state…

I found my mother very ill. I had a feeling that she had cancer. I can’t say how I knew. Probably because I thought about it all the time. I was always afraid my mother would die of cancer. Why? I guessed it… My father was bedridden… Life was very hard. As it is in Teslenko's work: "Hurry on to the grave..."

My sister Halyna had to leave her homeland because they wouldn't give her housing in Malyn because of me, wouldn't let her build a house. When she did get a plot, they gave her one under high-voltage power lines, where the magnetic field is strong. When she started to build and had already paid for a prefabricated wooden house, they didn't give it to her. She sued to get her money back. She had to leave to find work somewhere. Where did Ukrainians look? Beyond the Urals.

My brother Viktor had a very hard life. His wife, a teacher, was fired from her job because of me, and she died shortly after. His life was crippled. He had a stroke. He was paralyzed. He was sick. Somehow he recovered. But he couldn't help me in any way.

V.O.: I know that your mother appealed to Georges Marchais on your behalf…

D.M.: Yes. She was at the trial in Zhytomyr. And my aunt Olha. They wouldn’t let her in, but she got through. I didn't see them. My mother did indeed write a letter to the General Secretary of the French Communist Party, Georges Marchais. I haven't read that letter… According to her story, it said that one witness at the trial testified: “I signed because the KGB officer told me he would hang me if I didn’t sign.” The prosecutor heard this and immediately silenced the witness: “They taught you to say that.” But my mother heard it. Also, that I didn't want the children of political prisoners to be killed. She laid this out for Georges Marchais. It was published somewhere. Elections were approaching in France. He soon came to the Soviet Union, so it had some significance. Although it didn't make things easier for me. Except that they kept telling me: “Write a plea for a pardon.” Especially towards the end: “Just say a little something. On the radio. On television. There’s the tape recorder… We'll release you in a month.” This was during the “prophylactic talks” in Zhytomyr. It was hard for me even to walk then. I wasn’t even thinking about writing or saying anything. Then they said: “You don't consider us human beings.” I didn't think about whether they were human or not. I simply didn't want to see or hear them.

That is all I wanted to say.

Many things in history seem to have passed and died, but in reality, they leave their traces. For example, when I had surgery after the beating, a man was lying next to me—a former front-line soldier. He told how they were defeated in the Carpathians. They lost all their weapons. He was wounded, with a shattered leg, and was captured by the Germans. A younger German wanted to shoot him, but an older one didn't allow it. They put him on a stretcher. He recovered in a camp. He befriended captive officers—a major and a colonel. They always stayed together. They ended up in the British zone of occupation. They were handed over to the Soviet authorities, but they were not imprisoned in camps, not even the officers, because they defended each other. But he said that he met a Tatar whom nobody in the camp liked. They twisted his arms and led him to the river to be shot. They turned him with his back to them. An officer fired—he fell into the water. Before his death, he asked me to visit his mother in Kazan and tell her about his fate. I remembered the address for a long time, he said, but now I’ve forgotten it. This is cruelty, characteristic of the era we lived through.

Three meters from the punishment isolator in Barashevo (Mordovia), where I was held (a forbidden zone with five or six fences), there is a grave of six thousand executed monks. A local guard told me that they were shot in 1939, in one day. The pit had already been dug. They were shot… The next day—maybe someone was being overly cautious, or what—the order came not to shoot them. There are six thousand of them there. The women were taken further, to a birch grove, and shot there. The place, when I was there, was entangled in barbed wire. There is no mound there. A lowland. The meltwater runs there. To the mass grave. All of this, of course, shapes a person. But it no longer evokes powerful emotions. You simply perceive with your mind what was.

That's all I wanted to add. Do you have any more questions?

V.O.: Are you involved in politics now?

D.M.: I take little part in political work. I am burdened by daily life, by my health. Rural life is generally hard. A hard life. You have to earn your daily bread every day. Poverty is no sin, but… What did Korolenko say? He has a story about it… He was a political writer of a rather narrow focus. It's probably because of him that the expression “kvass patriotism” exists, right? Well, you don’t have to write this down… He wrote that he became a Russian writer because when he was being transported to exile, a Russian peasant gave him a drink of kvass on the way. He liked it so much that he renounced Ukraine (he lived in Zhytomyr). He wrote that he knew very little about Ukraine. Something was preserved in his memory about some rituals, songs, some girls singing something… He lived a philistine life. Ukraine did not touch him. He went down a different path. Franko regretted it when some Ukrainians went down that other path. That their activities fell outside the scope of national life…