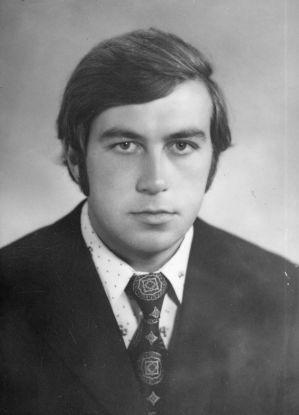

Interview with Yaromyr Oleksiyovych Mykytko

(Corrections by Y. Mykytko – April 21, 2006)

V.V. Ovsienko: On January 27, 2000, in the home of Yaromyr Mykytko in Sambir, Lviv Oblast, Vasyl Ovsienko is conducting this interview with him.

Y.O. Mykytko: I, Yaromyr Mykytko, patronymic Oleksiyovych, was born on March 12, 1953, in the city of Prokopyevsk, Kemerovo Oblast. My parents, as children of the repressed, were exiled to Siberia.

My mother’s father, Ivan Yurtsan, born in 1898, was drafted into the Austrian army in 1914 and later fought with the Sich Riflemen against the Russians and the White Poles. He was arrested in 1920, after which he escaped from prison and was forced to emigrate with his father to Argentina, then to Brazil. In the early 1930s, he returned to Zolochiv. When the Red Army retreated from Zolochiv in 1941, he was an activist in the reburial of victims of mass repressions. In 1944, he was arrested as a nationalist and sentenced to 10 years in prison. Consequently, his family—my mother, grandmother, and my mother’s sister—was deported to Siberia. My mother’s name was Volodymyra Ivanivna Yurtsan, later Mykytko.

My paternal grandfather, Hryhoriy Mykytka, a resident of the town of Shchyrets in the Pustomyty Raion, was quite literate, fluent in Polish and German, and was elected *viyt* [village head] of the village of Ostriiv during the German occupation. For this, he was later sentenced, also to 10 years, and his family was also deported. My father, Oleksiy Hryhorovych Mykytka, born in 1926, confessed just before his death that he had been a UPA liaison, but that was not the reason for his deportation. The NKVD had not exposed him. After my grandfather’s arrest, my father went into hiding; he was caught and deported to Siberia as the son of an “enemy of the people.”

My parents met and married in 1950. After Stalin's death, they were rehabilitated, and in 1956, we returned to Ukraine. I was 3 years old at the time. But my parents were forbidden to reside in the territory of Lviv Oblast (deprivation of rights), to which Shchyrets belonged, so my father was forced to look for work elsewhere and found it in the town of Sambir in what was then Drohobych Oblast, 60 km from Shchyrets. I studied at School No. 1 in Sambir, and in 1967, with the opening of School No. 10, I transferred there according to the district zoning. I graduated in 1970.

That same year, I enrolled in the Lviv Forestry Institute in the Faculty of Mechanical and Technological Woodworking, from which I was expelled on March 27, 1973, in connection with my arrest.

During our school years, Zorian Popadiuk and I studied and were friends. At that time, radios were very scarce, but Zorian Popadiuk had a “Spidola” with built-in additional bands at 16 and 19 meters, which weren’t jammed, and we constantly listened to Radio Liberty, gathering information and, as they say, entering the world of politics. The first event that outraged us was the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. I got together with a group of classmates, including the late Yevhen Pohorielov, Oles Ivantso, Omelian Bohush, Ihor Vovk, and several other boys, and we decided to react to those events in some way.

V.O.: What grade were you in?

Y.M.: We were in the 9th grade. We composed the text for a leaflet. We understood that such things could get us into trouble with both the judicial authorities and the militsiya. We decided to distribute those leaflets in a very clever way. It was only from the case files, after our group was exposed, that we learned that a criminal case had been opened in 1968 in both Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblasts in connection with the distribution of these leaflets. The system was very simple. The boys got on a regular bus, and on the way to Ivano-Frankivsk, they pasted up leaflets at every stop. After this successful action, we gathered again in Popadiuk's yard and decided to form an organization, the “Ukrainian National Liberation Front”—we debated the name but settled on that one. Like any organization, it had to have its own symbols, so we decided to make a flag and a seal, and we decided to pay membership dues to be able to buy a typewriter in the future.

V.O.: So, all the characteristics of an organization, Article 64.

Y.M.: Yes, all the characteristics of an organization.

V.O.: And why that name—“Ukrainian National Liberation Front”?

Y.M.: Because we were already reading *samvydav* literature. Popadiuk’s mother worked at the university in Lviv and was close to the *Sixtiers*, so we received some literature.

V.O.: I’m curious, what did you happen to read back then?

Y.M.: What I remember most is Ivan Dziuba’s work *Internationalism or Russification?*, and some articles by Chornovil...

V.O.: And I’m curious, in what form was this literature?

Y.M.: The literature was in the form of photocopies and typescripts.

We drew the name from the then well-known underground organization “Ukrainian National Front” from the Ivano-Frankivsk region. But we wanted to be a little different from them because we had no contact with them. We had no idea where it operated or who led it. We found out a little when they had already been convicted. We decided to differentiate ourselves slightly, so we called ourselves the “Ukrainian National Liberation Front.” All the paraphernalia we needed was made, for the most part, thanks to Popadiuk's own initiative.

Later, when we finished school, we met very rarely. Some from that Sambir initiative group studied in Rivne, some in Ivano-Frankivsk. We started to look for connections, for people who were close to us. Zorian found support among students of the history faculty at Lviv University. By that time, we had bought a typewriter and were reproducing some *samvydav* materials. And since we, as they say, didn't have a professional typist, we took turns learning. The typewriter was repeatedly moved from Zorian Popadiuk's place to mine, to my parents' house. When none of my parents were home, we retyped some materials. I can’t recall specifically what they were, as it was a long time ago, but we did distribute a bit of literature.

In 1970, everyone in our group enrolled in various universities in Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Rivne. Our practical work became a bit more complicated because we had very few opportunities to meet. Popadiuk and I took on most of the work. I assisted him in all organizational and practical matters. I enrolled at the Lviv Forestry Institute in the Faculty of Mechanical and Technological Woodworking, and at that time Zorian found like-minded people at the university—they were mainly history students. They already had an informal study group. They were interested in questions that were blank spots in historical literature. They created their own group, would gather somewhere in an apartment, take on reports on one topic or another, sit in libraries, search for literature, and thus collectively deepened their knowledge of history. Zorian found like-minded people among them, and they, as far as I know (because I hardly knew any of those people), began to prepare materials, and the idea of publishing a journal emerged. They agreed that the journal would be called *Postup*. This journal included some materials and articles by the students themselves, as well as some *samvydav* works that were circulating.

We printed the journal in Sambir in our apartments, at my place, at Popadiuk's. When the repressions of 1972 began, Zorian Popadiuk’s mother, who taught at the university, was fired from her job. Their apartment was searched—they lived on Engels Street in Lviv. Chornovil sometimes stayed at their place. *Samvydav* literature was found there—that was in the spring of 1972. Popadiuk was also expelled from the university. (During the search on January 12, 1972, at the Popadiuks' home, no *samvydav* literature was found, fortunately, although it was in the apartment. Zorian Popadiuk was expelled from the university on February 16 for mocking the KGB agents during the search—for which he was fined by the court. His mother, Liubomyra Popadiuk, was fired from her job in June 1973. – V.O.).

I can recall one nuance that we didn't pay attention to at the time. In the fall, he was called up for military service. He already had his draft notice, was all packed, and had already come from the military enlistment office to the train station to board the train—and he was given a deferment, for unclear reasons. We didn't understand it at the time, but later we analyzed it and came to the conclusion that we were already being watched. And perhaps there was someone among the newly recruited people, among the students, who was likely providing information to the KGB. When Zorian was given the deferment, he had more time, and practical work began: that journal was printed—it wasn't much, 5 sets of folded sheets, but, as we now know from the investigation materials, they counted more than 15 copies—that's what was confiscated. Apparently, someone else was reproducing them.

V.O.: And how many pages were there, approximately?

Y.M.: I think it was about 40 pages of typescript.

In 1973, after the 1972 repressions against the Ukrainian intelligentsia, it came to the point where Shevchenko evenings were banned at Lviv University. For that reason, Popadiuk and the university students, his former acquaintances and those who worked with him, decided to print a leaflet of protest, which began with Shevchenko's words, “Let's rise up, let's break our chains.” The text was printed on a single page. Popadiuk found me in Lviv and brought me about 50 leaflets; the Lviv University students took care of the rest. I left some of the leaflets with another one of our Sambir natives, although he was not a member of our organization, but we studied in the same faculty—I left him about 10 leaflets to distribute in the dormitories of the Forestry Institute, which he did and for which he was expelled from the institute...

V.O.: What was his last name?

Y.M.: Roman Radon. Well, and I involved another one of our mutual acquaintances in distributing these leaflets—Myron Klak. His fate after all that is completely unknown, as he was neither arrested nor prosecuted; he wasn't part of the investigation.

Knowing some conspiracy methods from detective novels, we took glue and gloves so as not to leave fingerprints, and in the evening, we went around Lviv and pasted up almost all the leaflets.

At about ten o'clock in the evening, I returned to the apartment where I was living with my relatives in Levandivka—understandably, I was agitated. I had a separate room. I had just lain down and, maybe 15-20 minutes later, before I had even fallen asleep, the doorbell rang. My *vuyko*—uncle, as he is called, my father's sister's husband—got up and opened the door. They came in, showed their identification, and asked if Yaromyr Mykytko lived here. My uncle said yes. They said he probably lives in that room—it's unknown how they had that information. They said: “We have a complaint against him and are going to conduct a search.”

V.O.: Were these men in plain clothes?

Y.M.: In plain clothes. As I later found out, the one who showed the identification was my future investigator from the Lviv Oblast KGB, Vadym Ruzhynsky. They, as they said, had two witnesses with them. They conducted a search, worked carelessly, and found nothing, although if some logic had been applied, they could have: I had maybe 2-3 leaflets left in my jacket. The jacket was hanging on a rack in the hallway—when they took off their coats, they hung them right over my jacket. They only searched in one room, turned everything upside down—and found nothing. It was about three o'clock in the morning. They asked me, demanded: “We know everything, you were putting up leaflets.”

V.O.: What date was this?

Y.M.: It was on the evening of March 26-27, 1973. The search lasted until about three o'clock. They found nothing, drew up a report that nothing was found, I signed it, but they told me: “Let's go to the department, we'll sort things out there.” I explained that I had to go to my classes in the morning, but they said: “It’s fine, we’ll give a note to the institute so they'll count the day for you.” The car was waiting downstairs—as they say in the jokes, a black “Volga”—and it really was a black “Volga.” We drove off.

V.O.: And what about the jacket and the leaflets?

Y.M.: The thing is, in the alcove in the entryway, I had a coat, and I put it on. They also got dressed, and the jacket was left hanging. On the way, they tried to persuade me: “Let's go and take down the leaflets.” I later read in the investigation materials that the entire Lviv Military-Political Academy had been put on alert, and they had spent the whole night walking the streets. They tore down a few things, but some were left. I had, by the way, pasted one leaflet on the door of the editorial office of the newspaper *Vilna Ukrayina*. I denied everything, thinking that since they hadn't found the leaflets... Well, and out of youthfulness—I later realized it wasn't quite like that. From the investigation materials, it became clear that they had been leading up to us, but—I still can't understand how it happened that they, as they say, lost us in the city. They just lost us.

V.O.: And they allowed you to actually get the job done...

Y.M.: In principle, it was the same as them hanging their coats over my jacket—that's how well they were watching us. The service was working, I think, at a “D” grade level.

V.O.: By the way, the leaflets left in the pocket, did they find them later? They could have done a second search and found them.

Y.M.: No, they didn't do a second search. My uncle found those leaflets and destroyed them, and that was that.

They took me to the KGB department at 1 Myru Street, where a sign said “Militsiya,” and behind it was an old Austrian prison, now the SBU prison. They did a standard search, unlaced my shoes. They took me to an office. In the office was the same Vadym Ruzhynsky, the investigator. We arrived at three-thirty in the morning, and the interrogation went on nonstop in that office until about midnight. The people kept changing, though for lunch they brought me a bun and made me some tea, and it just went on, and on, and on... Until 12 o'clock at night.

I denied everything, thinking they would believe me, but they said: “The thing is, we have some information.” Although from their questions, I already understood that they knew about one thing, another, a third... They had some information from somewhere. I wouldn't say they were brutal. I denied everything, and it ended with them bringing me (that day, I mean), as if by the way, several photographs showing mutilated corpses, a severed head—well, that was just standard psychological pressure being applied. They said that “people just like you did this.” They asked if I knew a certain Popadiuk. I said: “Of course I know him. We went to school together.” From all this, I understood that they had a large amount of information, and all they needed was for me to start giving testimony.

At about 12 o'clock at night, they told me: “We haven't fully sorted out the situation today. You can spend the night with us.” They opened a cell and took me into the cell. I spent the night, and the next morning the interrogation began again. I don't remember if it was on the second or third day, they started presenting me with the testimony of certain people, to jog my memory. I realized that some of our friends were giving it, each as they could, whoever was more or less involved. When they started bringing me depositions on the third day, I saw that, in principle, there was no point in arguing further, and I just started confirming what had already been recorded in the protocols.

At the end of the third day—I don’t know how many people were arrested there, but at least about 10-12 people, maybe, had been in the cells for 3 days. They began to release the detainees. I figured this out from the conversations of the “corridor guards.”

V.O.: That's up to three days—for detainees. They were in such a hurry to squeeze something out because after three days they have to either release them or present preliminary charges and arrest them.

Y.M.: Yes. And later the fate of those who would be part of the case and who would be witnesses was decided. Probably all those who were detained—because I heard conversations through the door, as people were taken for interrogation all day—words slipped out between the guards: this one's being released, that one's being released. Well, and in the evening, they brought me to a large office, sat me in a chair in the middle of the room, like in a zoo, with 10-15 men in civilian clothes sitting around, who looked at me askance, and from one of them came only one question: “What—were you avenging your grandfathers?” They didn't even wait for an answer, and I didn't know what to say. Then someone nodded, and they led me out. I spent the third night there and realized that I was now under arrest. The next day, indeed, they extended my detention for a month, then extended it again; I was already considered arrested. Then the investigation—that was just a formality, because almost everything was already known. Some details were just being clarified.

Over the months, you get used to the cell and you can roughly tell when you're just being taken for an interrogation. There were several passageways from that prison—you can already tell by the way the guards treat you that you're just going to sign another protocol. But one time, before taking me out, they “shook me down,” then led me through one corridor, to the wall—and shook me down again, then led me through another corridor—a third shift shook me down.

V.O.: Does that mean they are taking you outside the prison?

Y.M.: No. They brought me, as always, to Ruzhynsky’s office. I wouldn’t say he was a particularly cruel person—he was just an ordinary careerist. It so happened that after my release, I accidentally met him at a soccer game in Lviv. When he saw me, he turned red, as he always did when he turned red, and only asked: “Is that you?” I said: “It's me.” “Well, how are you?” I say: “It’s over.” He says: “Do you hold any grudge against me?” I say: “Why should I hold a grudge, when you were conducting a case that was already wrapped up and the facts were known?”

So then, they bring me into the office, and Ruzhynsky is sitting there, almost purple. As usual, he doesn’t greet me. And next to him sits a man in a military uniform, with large glasses. Short in stature. He conducted a formal interrogation on some issue, we signed the protocol, and they led me out. About 2-3 hours later, they call me in again, but this time without any such precautions, without those endless shakedowns. He was typing up a protocol, they called me in to sign, and then they told me, by the way: “Do you know who that was? That was Fedorchuk.” At that time, Fedorchuk was the head of the republican KGB, which is why they were all so scared.

A few months later, I already understood there would be a trial. I already had a lawyer, some honored war veteran, a Russian himself, he was missing a leg, clearly had a prosthesis. Just then, before our trial, Ivan Dziuba's letter of repentance appeared. The lawyer, when he met with me, told me: “Don't worry, Ivan Dziuba got five years, but what are you compared to Ivan Dziuba?”

V.O.: Let me clarify: Ivan Dziuba's statement was published in the newspaper *Literaturna Ukrayina* on November 9, 1973. But it was written earlier, and the non-newspaper text was shown to some. And the head of the Kyiv KGB investigative prison, Lieutenant Colonel Sapozhnikov, brought me *Literaturna Ukrayina* from November 9 himself.

Y.M.: November 9th? That means it was after the trial. Because he told me that Dziuba got 5 years and was released under amnesty. (The trial of I. Dziuba took place on March 11-16, 1973; he was sentenced by the Kyiv Regional Court under Part I of Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to 5 years in camps and 5 years of exile. In October 1973, I. Dziuba appealed to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the UkrSSR for a pardon, and on November 6, 1973, the Presidium pardoned him, and he was released. – V.O.). Maybe the cassation appeal had already been written then. I don’t remember well, but there was such a conversation with my lawyer. He filed the cassation appeal. Of course, it was rejected.

V.O.: And when was the trial?

Y.M.: The trial was in August 1973—I don't recall the exact date, I'd have to look at the verdict. (August 6-7, 1973. – V.O.). The trial was closed, as it was for everyone.

V.O.: And is it written in the verdict that it was a closed session?

Y.M.: No, they didn't write that in the verdict. The reason is that there were some people at the trial, but they were strangers. A few people were always there—my parents, my dad would come...

V.O.: Was your father at the trial the whole time?

Y.M.: Yes. Well, not the whole time. The trial lasted, I think, 3 days—he was there about twice. The prosecutor—like any prosecutor, he always demands the maximum; he practically made us out to be executioners and bandits, like in that photograph with the severed head.

V.O.: It was strange to listen to: is this really about me?

Y.M.: Yes, yes. And the prosecutor was very well-known in Lviv; he even tried his hand at writing, Antonenko. Everything he said boiled down to, “Ukraine, the Ukrainian people, condemn bourgeois nationalists.” Prosecutor Antonenko would come to court in an embroidered shirt and speak in Russian, “branding” us in Russian.

V.O.: Look at that! So blatant...

Y.M.: The final result—of course he asked for the maximum for us, 7 and 5, but I was given 5 years of imprisonment, and Popadiuk was given 7 years plus 5 of exile.

V.O.: And was there no attempt to charge you under Article 64, “Organization”?

Y.M.: No, only Article 62, Part 1. There was another person in the case, Khvostenko, but at the trial, it was read to us that due to illness, he was currently undergoing treatment, and his case had been separated. Khvostenko's subsequent fate is unknown, although he took an active part in the preparation of *Postup*.

After the trial, they held me for another 2 or 3 months, while the cassation appeal went through, while we waited for the *etap*. I think it was early November—"with your things," to the *etap*, the train station... An interesting detail: maybe it was done on purpose—my parents brought me a package with all sorts of canned food. A good little backpack, a good food pack. They gave it all to me. For the *etap*, the KGB gave me a dry ration for the road, probably half a kilogram of ham, bread, sugar. I had no idea where we were going. They brought me to the freight station while it was still dark, in the morning, and put me in a wagon. The first wagon was probably completely empty. They opened one section, put me in, I placed my things under the bench and lay down. The wagon gradually began to fill up. Shouts, noise, women being seated separately. And I'm lying there proudly, all by myself. I hear them crowding around, shoving a bunch of people into one cell.

V.O.: You must have been in cell 9, the three-person one?

Y.M.: No, somewhere in the middle of the wagon. Finally, the doors open and my cell also starts to fill up. It turns out they stuffed 16 of us in there. I look—all the men are older. What am I, 20 years old, and these are men already in their late 30s, over 40—well, and they look at me like that... Sizing me up, who I was, and I them. It turns out they were transporting special-regime prisoners—recidivists. Here in Lviv, they have a republican hospital for them.

V.O.: What, were they in stripes?

Y.M.: Yes, from the hospital. The convoy had everything sorted by regime, or maybe it was done on purpose. On my file it said “especially dangerous state criminal,” and on theirs, “especially dangerous criminals”—a one-word difference. But that’s not the point. They looked me over, and apparently, there was a senior among them—I later understood they have some sort of hierarchy, he's the leader among them—and he says: “Listen, you, what did you, what did you do? How old are you?” “I'm 20.” But I’m afraid to admit I’m an anti-Soviet, that it’s anti-Soviet activity, because that’s an “enemy of the people.” Well, they slowly questioned me: “Did you, like, knock off ten guys, or what? How many? First time in and already special regime? Did you, like, knife ten guys?” Well, of course, I was a bit scared, because I had never met this type of people before. I told them it was for leaflets, for anti-Soviet propaganda. How they flew into a rage! They started pounding on the door, they started screaming: “Damned pigs, you’re trying children now?” The train was already moving, and they shouted that the communist gang was now starting to jail children for a leaflet. They raised a ruckus in the whole wagon, they were about to start rocking the wagon, because there’s this thing, if they get the signal, they’ll sway to one side, then the other—and the wagon rocks a little.

Then the situation is this: everyone is standing sideways, some are hanging on the third-tier bunks, crammed in somewhere, and that's how we travel. But the time comes when you need to have a bite to eat. For their rations, they were given rotten fish—the whole wagon stinks from that fish. That bread... And I have ham, I have canned food. And they started treating me very well. For some reason, I wasn't allowed to receive candies in my cell. But they had bought candies at the commissary in the hospital—and they gave me all these candies... It was time to eat—a terribly awkward situation. I say: “Guys, wait, could you squeeze together a bit, I’ll lift the bench, I have canned food there, stew, some things they passed me for the road. You see, they stuffed a piece of ham in here for me—boiled meat.” I say: “I’m not going to eat alone, let’s all eat.” Well, I see that these people are treating me well. Then the senior one said: “You still have to chew on the permafrost, kid,” as he put it. “We're here, in Ukraine, we're not going any further, but you... Forget about it.” And all the way to Kharkiv (because I didn't know where they were taking me) I didn't eat anything, because they themselves said we don’t know how long we’ll be traveling. They knew they were going to Kharkiv, but I didn't. I felt terribly uncomfortable as they ate that stinking fish, but they didn’t take a single can from me and didn't even want the meat, no one wanted it, because the senior one said: “That's it...”

Well, we reached Kharkiv, then they took us in a Black Maria to that transit prison.

V.O.: Kholodna Hora.

Y.M.: Yes, I know. I ended up in a transit cell. In the cell was Vasyl Zakharchenko (Born Jan. 13, 1936. Arrested in Jan. 1972, served time in camps in Perm Oblast. On July 19, 1977, his “penitent” statement was published in the newspaper *Literaturna Ukrayina*, in connection with which he was pardoned. A writer, laureate of the Shevchenko Prize in 1995. – V.O.) and some Baptist preacher, or from some sect. We got acquainted there, and literally a day or two later we went by *etap* to Ruzayevka. They dropped me off in Ruzayevka, and I ended up in the 17th Mordovian camp, and Vasyl Zakharchenko went to the Urals.

We traveled for maybe 10 days, not more. They brought me to the 17th. It was a small zone, maybe 150-160 people. It was like a subdivision of a large women's colony; it didn't even have its own kitchen, food was brought from the women's zone. At that time—the end of 1973—what kind of contingent was there? I met Dmytro Kvetsko there (from the Frankivsk group, from Dolyna, the “Ukrainian National Front,” with the late Vyacheslav Maksymovych Chornovil). There were three of us Ukrainians there—among the young ones, as we say. Because there were mostly members of the underground from the Baltics, from Ukraine, Belarus, a few deserters from the army in the GDR, there were young Lithuanian guys—Alex Pasilis, Bronis Vilčiauskas, there were Armenians—the older one, Babayan, and the younger one, Suren Milykian. There were Russian democrats—I've forgotten their names.

V.O.: And was Bolonkin there?

Y.M.: I met Bolonkin in the 19th camp, but Bolonkin wasn't there yet. Pashnin was there, and later Kronid Lyubarsky. There was Vyacheslav Petrov, who considered himself part of the Russian democracy, a very intelligent man. As far as I know, he passed away long ago. That was my first zone. They moved us from zone to zone so we wouldn't come together and communicate. The more we wrote various statements and protests, the faster we were parted from that zone. There was some action when we declared a hunger strike, and they dispersed us—some to the isolator in the 19th, because there was no isolator on the territory of the 17th, some to the isolator of the women's zone, some to Vladimir. Then, after a series of protests, I was transferred to the 19th, and Zorian Popadiuk was transferred to the 17th. I already knew—it was passed along through the *etaps*—that Popadiuk was in the 19th zone. Who else did I meet in Mordovia? I got sick, had pneumonia, they took me to the hospital in Barashevo, to the third camp. On the way, as the wagon was moving, there was a women's political zone. I saw Stefa Shabatura and Iryna Kalynets, exchanged a few words with them—who, from where? From Ukraine. It was interesting to meet my compatriots.

Well, and later—the 19th. In the 19th, among our compatriots was Vasyl Ovsienko... Ihor Kraintsiv was there, who educated me for the first time, because I didn't know about the address “pan” or “panych.” Who else among the young Ukrainians was there? Kuzma Matviyuk, Hryts Makoviychuk from Kremenchuk. Makoviychuk—a small man, not tall.

V.O.: But he was quite stocky. Petro Vynnychuk and Mykola Slobodian. Kuzma Dasiv was there. Who else? There were older men, from the insurgents, Dmytro Syniak—did you meet him?

Y.M.: Dmytro Syniak was there.

V.O.: Mykhailo Zhurakivsky, Ivan Myron, Mykola Konchakivsky, Roman Semeniuk. That was our circle. Y.M.: Yes. The 19th camp is most memorable to me for its volleyball court, where the Ukrainian national team fought against the entire Soviet Union, led by Dima Mikheyev.

V.O.: But Dima Mikheyev was from Kyiv, too.

Y.M.: Yes, he later did manage to go abroad, because he was imprisoned for attempting to leave on false documents. I think he was amnestied; he didn't serve his full term.

V.O.: Right. He was one of those who were ashamed that they did a little work for the KGB and would blush beet-red because of it.

Y.M.: But I know he did go abroad. I even heard him on the “Voice of America” after his imprisonment; he was speaking. Later, Petrov was in the 19th zone. We also held various protest actions related to various events both in the world and in Ukraine, and then there was a massive *etap* in 1975...

V.O.: I think it was in July, that's when they moved very many people.

Y.M.: The 19th also struck me because there—this didn't happen in the 17th—they had a morning walk to the music of “Heart, You Don't Want Peace...” The disabled, the old, and everyone else would make a “lap of honor.”

V.O.: Yes. I especially came to loathe “Farewell of Slavyanka.” At reveille—it's natural that the first thing you need is to run to the toilet—no, there are guards standing by the toilet and they won't let you in. Go to physical exercises—so that urine, instead of blood, circulates through your body.

Y.M.: Yes. In the 17th, we were learning to sew, making gloves, and in the 19th, it was woodworking. They taught me how to polish watch cases. It turned out to be very simple. Although on the first day, I probably ruined half of the production. But later I could fulfill the norm in 4 hours. So the rest of the time was left for reading a newspaper or some literature.

V.O.: But secretly from the guards.

Y.M.: Secretly, yes. Well, at first, yes, but later, when you get used to it, you already know where to hide.

V.O.: It was a big zone, there were places to hide.

Y.M.: Then there was the big *etap* of 1975 to the Urals. They opened a new zone there. In fact, it wasn't yet developed; we were installing metalworking machines in that factory. There, in the 37th, in Vsesvyatskaya, where I spent about a year, maybe a little less, production hadn't been launched yet. We were involved in installing machines, pouring concrete, etc. There I met the boys from the Chortkiv group—Volodia Marmus and his co-defendants. Petro Vynnychuk, Mykola Slobodian. They were brought from the 19th. Later, Volodia Marmus and I were taken to Polovynka, to the 35th—that was my last year of incarceration. It was a unique zone. Firstly, there were many interesting people there from whom I learned a great deal, in a purely intellectual sense. At that time, Ivan Svitlychny was in the 35th—he was, admittedly, very ill. He was considered a patriarch in the zone... He had very high blood pressure, he was very sick. He was engaged in his own research work. There was Yevhen Sverstiuk, with whom I had many conversations and from whom I learned a great deal in a spiritual, moral, and philosophical sense. There was Ihor Kalynets—an interesting, peculiar man.

But what’s interesting is that I accidentally met a not-so-distant relative of mine, whom I had never known about, who was never even spoken of in the family because our family had endured severe hardships in Siberia and across the world—Yevhen Pryshliak. He had been sentenced to 25 years. And sometime between 1949 and 1951 or 1952, he was the commander of the Security Service of Lviv Oblast. They took him from a hideout with a head wound—he had such scars. We met purely by chance. He was an older man, already finishing his term—I think he was released in 1978. Of his 25 years, he spent more than ten in solitary confinement in Vladimir. And it turns out, he was my grandmother's brother, from the Pryshliak-Hukhovetsky family from Shchyrets in the Pustomyty Raion of Lviv Oblast. The name Pryshliak meant nothing to me. A few months passed, we lived in the same barracks, we communicated... How did we communicate? As Ukrainians, we celebrated our various religious holidays; whoever had something would bring it, and we would set a table. And one day he asks me: “Where are you from, yourself?” I say: “From Sambir.” Well, Sambir meant nothing to him, so he asks: “And your parents?” I say: “No, we’re not natives, I’m not a Sambir native, my father is from Shchyrets.” So he says, very delicately: “I know the Mykytkas there, but they are Mykytka.” And my grandfather was indeed Mykytka and spelled his name that way, but when my father was exiled to Siberia, they didn’t understand the ‘a’ there, they wrote an ‘o’, and so the last letter changed. Well, we got to talking, and it turned out we are quite close relatives.

In the 35th was the “Russian emperor” Ogurtsov—well, I'm joking a bit, but he was a member of a monarchist organization founded sometime in the sixties in what is now St. Petersburg. A very educated man, he graduated from the Institute of Oriental Languages, he knew several Turkic languages and even dialects. A very peculiar man, I had many conversations with him, because not many people wanted to talk to him, as he spouted Great-Russian chauvinistic “nonsense.” Besides, there was something wrong with his memory. Well, since I, being young, listened to him, he would talk to me, tell me things, and it was interesting for me to listen to him.

I must mention Stepan Mamchur, who was finishing his term. He was, as I recall, a repressed Greek-Catholic priest. Not long before his release, he simply died in the camp and never returned to Ukraine. (Stepan Mamchur had a 5-year sentence in a Polish prison (1934-39). A participant in propaganda groups on their way to eastern Ukrainian lands. Was a local OUN leader. In the 1950s, settled in Irpin near Kyiv. Arrested in 1957, sentenced to 25 years. Died on May 10, 1977, in camp VS-389/35 in Perm Oblast. Reburied in Irpin on July 26, 2001. – V.O.)

In the 35th—I don't know whether to talk about it or not, but in short—there was a very well-developed system for transmitting information to the *Chronicle of Current Events*.

V.O.: You must talk about this.

Y.M.: Since there were many people there who were capable of powerfully producing their intellectual information, their creative work... For example, Valeriy Marchenko, Semen Gluzman... I didn't meet him in freedom, though I've read some of his publications—I wouldn't say he wrote poetry, but his poetry teacher was Ivan Svitlychny...

V.O.: And in 1994, he published a collection of poems, *Psalms and Sorrows*, written in the camp and in exile. They say they are very beautiful poems.

Y.M.: Yes, a peculiar kind of poetry. The system of transmitting information there was very well-organized. From a circle of trusted people. Practically everyone who was leaving, with the help of a simple but very original method, took information out with them. Then that information about events in the 35th zone would appear in the *Chronicle of Current Events*. I was also involved in this, as I rewrote the information that was given to me. Accordingly, there was a system of guarding the person who was writing. We were alerted if someone undesirable approached. Truly, my richest impressions are from the 35th zone.

V.O.: You must have been sorry to leave the 35th zone?

Y.M.: I was even sorry to leave, because there were truly so many people from whom I learned so much. Some people say they went through universities in prison—well, I went through my university in the thirty-fifth. Because communicating with people like Svitlychny, Sverstiuk, Marchenko—it was very gratifying. There were boys from Kolomyia—Vasyl Shovkovy. One time, he and I ended up in the punishment cell together. He was, as they say, the volunteer projectionist. In that booth, there was some kind of record player. We were almost the same age; I think he's a year older than me. As compatriots, we sang carols and drank tea in his radio booth and played two worn-out records. On one were recordings of Adriano Celentano. I remember there was a song “I am a lion.” When they were showing a newsreel and showed Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, something went wrong with the switch, and suddenly that roar of Adriano Celentano came on. Well, after that, Vasyl and I landed in the punishment cell.

About a month or a month and a half before the end of my term, they take me for an *etap*. Since it was common practice that no one was released directly from the zone, but were taken by *etap* to the regional center, I prepared in advance. Since I could be taken out at any time—tomorrow, or the day after... I had been preparing for my departure for a long time, and I had all the information I was supposed to take with me. And so they take me—with my things for the *etap*. They put me in that punishment isolator for the “holding period.” And the “holding period” lasted, I believe, 4 days. I sat in the isolator, and after that—a Black Maria, the road. It was probably about a month, maybe a little less, maybe 3 weeks before my release that I spent in the same prison where I was put after my arrest. And I did get that information out. The procedure was very difficult, unpleasant, though original... It's interesting that in my cell there was a person who got there by some unknown means, and I couldn't get away from him. It was impossible to hide from him... He himself told me where he was from and why he'd been brought there, but he didn't rat me out, although for some things, I could have suffered greatly.

On exactly March 27, 1978, the same day I was arrested, I was released. My parents came for me. They gave me six months of surveillance, although the district officer, one of our neighbors (he has since passed away), came and said: “Do you want to go somewhere? If so, tell me, because that surveillance is on me.” He knew my father well. “Just tell me when you're leaving, and I'll, just in case, cover for you somewhere,” he told me.

In 1979, I got married. My wife Tetiana, or rather, her father, is from Zaporizhzhia, and her mother is from Sambir. She grew up in Zaporizhzhia, in her father's homeland. We met, got married, have two children, a daughter, Iryna, born September 26, 1980. In 1998 she graduated from Secondary School No. 2 in Sambir with a gold medal and is now studying at the Lviv State University in the Faculty of Geography. My son Oleksiy, born February 20, 1983, after 9th grade, is a student at the Sambir Technical College of Mechanized Accounting, in the computer programming department.

In 1982, I enrolled in correspondence courses at the Lviv Forestry Institute in the Department of Forestry. I started with woodworking technology... There were interesting nuances, but—times were changing. The fact is, they pulled me out of one exam in Lviv. I was already taking the third exam when a KGB agent from Sambir arrived, and they started failing me. I knew the exam questions, because I had even studied physics as an additional elective in school. I knew physics well; I didn't even prepare for it much. But when they started asking me about Newton's fourth law, and then Newton's fifth law, I realized that something was not right.

V.O.: Aha, because there is no fifth law?

Y.M.: It doesn't exist. The fourth, theoretically, existed, I knew the fourth, but the fifth never existed in nature—it was an invention of our professor. When they sent me away, saying, “That's it, you didn't pass, you don't know physics at all,” I went out into the hallway and ran into one of our Sambir KGB agents. I only knew him by sight, because he was a soccer player and played for the Sambir team “Spartak.” He asks me: “What are you doing here?” I say I'm taking an exam, and he says: “And why don't we know anything about it?” I say: “Wait, I'm not applying to the KGB school...” “Well, how could you...” “Don't worry, I already failed to get in—I don't know any physics.” He took me to some office and started telling me: “You know that they still remember you here at the institute, not much time has passed, why didn't you apply to some other university? We have nothing against it.” I say: “Wait. It’s my choice, I decided so, I like this specialty. They cut me down properly here, I can already see by whose hand it was.” “No, no, we had nothing to do with it, nothing.” When I went to get my clearance slip, it turned out that it had a grade of 'three' [a C] on it. And, by the sum of my scores, I actually got in.

I worked in the forestry department in various positions. At first, after my release in 1978, no one wanted to hire me. They took me on as a woodcarver in the forestry department—there was a souvenir workshop. There was a little house, all sorts of souvenirs. After some time, I worked as a storekeeper in the internal materials warehouse, and after the 3rd year of correspondence studies, when correspondence students were required to work in their specialty, I went to work at the Dubliany forestry of Sambir Raion, where I worked as a foreman. Later, for a year, I worked in Staryi Sambir, at the “Spas” forestry, as a logging foreman.

And in 1990, when the elections for what we call the first democratic convocation took place, and Zorian Popadiuk, as a result of all those twists and turns, was elected head of the Sambir City Council—he had been released from the camp not long before—it's understandable that he didn't know people in the city, nor did he know the bureaucratic work, practically, because before that he had worked as a bread loader at the Sambir bakery—he offered me a position as his adviser. From 1990 to 1994, I worked as an adviser to the head of the Sambir City Council. In addition, there were two newspapers in our city that were fueling a religious conflict in Sambir. There were roughly equal communities and one church in the city. One newspaper supported one community, the Orthodox, the other supported the Greek-Catholic community. The newspapers only exacerbated the conflict with their publications. So we decided to create our own city council newspaper, the “Bulletin of the City and Raion State Administration”—at first it was the city council and executive committee, and then the city administration. I was the editor of that newspaper. I gathered material, did everything except the technical work. After our city and raion were separated in 1994, after new elections, I went to work in the raion state administration as an instructor in the organizational department. After that, on a separate job as the secretary of the commission for social protection of Chornobyl victims and secretary of the commission for ecological safety of the raion, where I work to this day.

My wife, Tetiana Pavlivna Mykytko, graduated from the Lviv Medical Institute; she is a pharmacist, worked in a rural pharmacy in the village of Luky as the head pharmacist, and now, due to the denationalization and privatization of small enterprises, it is a private enterprise, “Apotheka Luky.”

What other questions do you have for me?

V.O.: After your release, apart from that incident with admission to the institute, were there any other dealings with the KGB?

Y.M.: There were. I want to recall an interesting moment. I think Zorian Popadiuk will remember this better, but maybe I can figure it out. He had 7 years, so his term ended in March 1980, then he was in exile. So, in 1981, that firm called the KGB was working, as always, sloppily, and because of that, a funny thing happened. As it later turned out (I didn't even know it at the time), in 1981 Popadiuk was supposed to come on a legal vacation he had earned in exile. I was already working as a storekeeper in the internal materials warehouse. I get called to the military enlistment office and they tell me to go to Khyriv—there’s a paratrooper brigade stationed there. It’s still there now. That’s Staryi Sambir Raion. They wanted me for the “partisans.” And it was like this: they called me in the morning—so that by noon you’d already be there. V.O.: This is called military retraining.

Y.M.: I say to the military commissar: “You understand that I am a materially responsible person. I can’t just close up those warehouses like that, because there are parts for trucks, various household inventory, work clothes—I can't just lock up, as you say, and be in Khyriv in 2 hours.” He says: “If not, then we will prosecute you according to the law.”

V.O.: Deserter!

Y.M.: Yes, yes, as a deserter. So I went straight to the director of our forestry, saying: “Mykola Ivanovych, this is the situation...” He says: “What are they, nuts? Well, how is this possible? You hand over the keys—what if there's a shortage? Anything can happen... You have to do a proper handover here.” He rushed off to the military commissar. He returns: “Give the keys to—he said who—and go, because you don’t want to mess with them.” There was a guy there named Ivan, so I gave him the keys. He’s a good friend of mine, I know he’s a conscientious man.

I arrive in Khyriv, report to the checkpoint with this summons for the “partisans,” and the guard on duty says: “What partisans, we don't have any partisans!” I say: “I have orders.” He took me to the unit commander, who cursed me out: “What partisans? What kind of idiot is sitting in the military office in Sambir?” He dials the Sambir military office. The commissar told him something, and he says: “Well, alright. And where do you work?” “I work at the forestry warehouse.” “Well,” he says, “fine, for two weeks you’ll work here at our warehouse.” He called over a *praporshchyk*, the warehouse manager (Jewish by nationality), and says: “Here's a warehouse manager under your command.” The Jew, it turns out, got scared—why would he want witnesses at the warehouse? He also had warehouses for laundry, a bathhouse—he had three or four soldiers living at that bathhouse. I hung around for a day or two, and that *praporshchyk* says to me: “Listen, go home. What are you gonna do here...” He didn't want me in his warehouse, or what, he says: “Well, what are you going to do here? I'll cover for you, come back next Monday to check in.”

I come home, and they tell me: “You know, Popadiuk has arrived.” And they had conducted the operation so sloppily, to prevent us from meeting!

V.O.: And did you meet after all?

Y.M.: Well, I came back after 2 days, when that *praporshchyk* let me go. And how would the *praporshchyk* know what was what? The KGB, apparently, worked at a higher level to ensure we wouldn't meet. And I arrive—and they tell me Popadiuk has arrived. So we met right away when I got back. And I saw him off to his exile.

But I had no other incidents with them. There was the one with the institute admission and this one, to prevent us from meeting. There were no attempts to “get at me”—I can’t say anyone was really harassing us. I know who in my organization regularly wrote reports on me—he just told me himself: “You know, they called me in, told me I had to report on you—think what you want, be angry with me or not—I'm not writing any denunciations against you.” But they, apparently, were carrying out their preventive measures for the sake of ticking a box.

Any other questions?

V.O.: I have no more questions. I think we have covered everything quite well, and if we remember anything else, we will have an opportunity to add it. Thank you. So, this was January 27, 2000, in the glorious city of Sambir. Yaromyr Mykytko was speaking, and Vasyl Ovsienko recorded.

[ E n d o f I n t e r v i e w]

V.O.: On January 30, Yaromyr Mykytko speaks about his fellow prisoners. First and foremost, about Sasha Romanov.

Y.M.: My impression is that Sasha Romanov, although he went to the camps as a Marxist, understood the national question a bit better than most of the Russian democrats I knew. I remember him for knowing many poems in Ukrainian. In fact, it was from him that I learned, and still remember, the poem by Zinoviy Krasivsky, “My Triad.”

V.O.: Sasha, by the way, said that in his early childhood he had a semi-Ukrainian-speaking environment. He’s from somewhere in Saratov Oblast. “There,” he said, “are many Ukrainians, *khokhols*,”—so the Ukrainian language was quite natural for him.

Y.M.: I have a good opinion of him, especially since he had previously communicated with Zorian Popadiuk. He had a very high opinion of Zorian—I understood they had communicated and were good friends and fellow prisoners.

Undoubtedly, the person who made the greatest impression on me was Vyacheslav Chornovil, whom I met in the 17th, in Mordovia. An energetic man, he knew how to convince, how to rally people around him, how to stand up for his rights. I believe he is the greatest figure of our revival period of the sixties to nineties. That is my personal opinion; I know that some, even his associates, had some complaints against him, but I believe he is the greatest figure of our revival.

In the 17th camp, Dmytro Kvetsko made a great impression on me—a man of a philosophical turn of mind, with deep knowledge of Ukrainian history. We also communicated with him, were on friendly terms.

Of course, every camp had its leaders and organizers. In the 19th camp, one of the people who united nationalities and age groups was Vasyl Ovsienko.

V.O.: Is that so?

Y.M.: Who else? I, for one, personally don’t remember anyone else who could organize. To this day, I remember that before any actions, Vasyl Ovsienko would run around and persuade, rally people—then we would resolve all those issues. I don't remember anyone else.

V.O.: Kuzma Matviyuk, Ihor Kraintsiv, Kuzma Dasiv were there.

Y.M.: Kuzma Matviyuk was a deep thinker. He thought for a long time before deciding on something. Well, that’s my recollection.

As for the 37th, it was mostly us, the young ones, brought from different camps. It seems to me that it was the Ukrainians who organized several actions there. Among them were Volodia Marmus, Petro Vynnychuk, Mykola Slobodian. Undoubtedly, the people who made a very big impression on me, from whom I learned a great deal, were Ivan Svitlychny, with whom I was in the 35th. Although I communicated little with him because he was completely engrossed in his scientific work. But I communicated a lot with Yevhen Sverstiuk, had many conversations with him on political, moral, and ideological topics, and I learned a great deal from him as a young person who was, in fact, just becoming firm in his convictions.

Of course, there were many outstanding people there, but I don't want to just list them. Of course, Ihor Kalynets. Among people of other nationalities, I remember the young Lithuanian political prisoners: Bronis Vilčiauskas, Rimas Cikialis, Alix Pasilis; from the Estonians—Mati Kiirend, whom I met around 1989 when I was in Tallinn, I looked him up. From the Moldovans, Gheorghe Ghimpu made the biggest impression on me—a very impulsive, very active person. It seemed he was ready to storm the barricades, although everyone was somewhat wary of him, thinking that his peremptory actions could ruin any undertaking. But in general, he was very ill. Among the Latvians, I remember Gunārs Rode.

I would also like to especially mention my communication with “Pan Dobrodiy” [Mr. Benefactor], as we called him, Yevhen Proniuk. He was an incredibly unique person who inspired admiration from our side, your side, and everyone.

V.O.: In which zone were you with him?

Y.M.: In the 35th. I was with him for about a year. It was maybe late 1976 or early 1977, 1978. Something like that, for a year.

V.O.: Proniuk is a co-defendant of mine, so I’m interested to hear.

Y.M.: He was the kind of person you could apply to a wound. A person of such character that it seemed, no matter what you asked of him, he was ready to give you the shirt off his back. Well, I’m not talking about material things. This was a man who was always ready to be at the forefront, on the barricades, but at the same time, was ready to give everything to anyone, and often—his last kopeck. (Laughs). That’s what he was like... Our boys in the zone often quarreled with him—because by the time he brought that miserable parcel—he himself was sick with tuberculosis—by the time he brought it to the barracks, he had given it all away to everyone he met.

I have listed those with whom I communicated more closely. I especially want to note our 25-yearers. I already mentioned that I met my uncle Yevhen Pryshliak, who from 1950 to 1952 was the leader of the OUN in the Lviv region. He was captured in a hideout, gassed, tried to shoot himself, but they, as they say, revived him, and he served 25 years, 10 of them in Vladimir in a solitary cell, where he was listed as prisoner Ch-1. During that time in Vladimir, he was forbidden even to mention his own name. By the way, I'll show you—I brought a book about my family's lineage from my mother.

Dmytro Besarab—an extremely brave, steadfast person who always supported us, the youth, and all our actions, and, as they say, supported the camp's work, held his ground. Dmytro Verkholiak, Syniak—right?

V.O.: Dmytro Syniak—that was in Mordovia, in the 19th zone.

Y.M.: Yes, in the 19th. And in the Urals—Vasyl Pidhorodetsky.

V.O.: Oh, you knew Vasyl too?

Y.M.: Yes. And the esteemed—eternal memory to him, because he died in the camp—Stepan Mamchur. He died in the 35th.

I would like to note that I have a special memory of Semen Gluzman. In the 35th, he did a great deal to ensure that information about events in the camp, about the work of creative people who were in the camp, appeared on Radio Liberty and in the *Chronicle of Current Events*.

Among the Jews with whom I had the opportunity to communicate, I would like to single out Hillel Butman. He was a Zionist, a man of conviction, who led and coordinated the actions of the Jewish community. I met Hillel at the first congress of political prisoners in Kyiv. He now lives in Israel, but he came to our congress, and we met there. It was pleasant that he had not forgotten and, to a certain extent, supported the cause of Ukrainian independence.

V.O.: And what can you tell us about the gathering of information in the zones and its transmission to freedom? What do you feel you can talk about?

Y.M.: I believe that this process was quite intensive in the thirty-fifth, its technology was quite complex and original, but information systematically went beyond the camp's borders and practically all of it appeared on the airwaves and in print.

V.O.: Semen Gluzman, Mykola Horbal, and Zinoviy Antoniuk have already told some of this. Some of it has been published. (Mykola Horbal. *Vaha slova. “Khronika ‘Arkhipelaha GULAG’. Zona 35 (Za 1977 g.)”* // journal “Zona.” – No. 4, 1993. – pp. 134 – 150; S. Gluzman. *Uroky Svitlychnoho.* // Dobrooky. Spohady pro Ivana Svitlychnoho.– K.: Chas, 1998. – pp. 477-497. – V.O.).

Y.M.: Well, I would not want to delve into all those nuances, into the very technology of that matter, let it be... I was somewhat involved in this, but let the people who were the organizers and who consider it necessary or unnecessary to talk about that process—let them personally talk about it.

V.O.: He still hasn’t come out of the underground, you see, Zorian?

Y.M.: No, it's not that I haven't come out of the underground—I just believe that since I wasn't the initiator of that matter, although I participated directly, I don't know if it's appropriate to talk about it now.

V.O.: Well, there can be no coercion here.

This is the end of the conversation with Yaromyr Mykytko on January 30, 2000.