An I n t e r v i e w with Mykola Kostiovych K h o l o d n y i

V. Ovsiyenko sent the text of the interview to M. Kholodnyi on January 5, 2006. However, M. Kholodnyi did not correct it. He passed away at his home in Oster in mid-February 2006. The date of death is unknown. He was buried on March 15, 2006. Therefore, we are publishing the interview with question marks (?) in doubtful places. Indeed, this interview cannot be presented without the poems. We are adding a recording of M. Kholodnyi’s creative evening from September 13, 1999. Poems that are repeated during the creative evening are omitted here, leaving only their titles.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: On October 6, 1999, on Volodymyr Hill in Kyiv, we are speaking with Mr. Mykola Kholodnyi. The recording is being made by Vasyl Ovsiyenko.

This, Mr. Kholodnyi, is meant to be, so to speak, your dissident autobiography. The Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group is preparing the Ukrainian section of the “International Dictionary of Dissidents” (or “Dictionary of the Resistance Movement”)—the latter will include several hundred names, so it’s impossible for Mykola Kholodnyi not to be in it. We will also post these interviews on the KHRG website (See: International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former USSR. Vol. 1. Ukraine. Part 1. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; “Prava Liudyny.” – 2006. – pp. 1–516; Part II. – pp. 517–1020. The entry on M. Kholodnyi: pp. 799-805; KHRG website http://museum.khpg.org)

M.K. Kholodnyi: The Evil Empire touched me with its black wing even in my childhood, and my family—even before I was born. My grandfather was dekulakized. My grandfather didn't join the kolkhoz back then, so they threw him and his children out into the snow. And it was only because my godmother, my father's sister, Olha, was herding the brigadier's geese—the collective farms were already in place—that my grandfather bought his house back from the kolkhoz. I say, it was thanks to my godmother herding the brigadier's geese. Grandfather Ivan's sons were my father, Kostyantyn, and my uncle, Petro. Truth be told, they didn't have the same father, because my grandmother's husband died, so she remarried. So that uncle, Petro, was in Kotovsky's brigade. Kotovsky was no longer in command of it; Kryvoruchko was. Interestingly, Kryvoruchko wrote a very sharp letter to the village council demanding the house be returned. And later, Kryvoruchko was shot as an “enemy of the people.” Well, it turns out the Bolsheviks killed Kotovsky too.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Some guy shot him in bed while he was in the midst of his womanizing exploits!

M.K. Kholodnyi: You see, they didn't tell the truth back then... Well, my father went from Stalingrad all the way to Austria, and then ended up on the Japanese front. But the Germans—what’s interesting—treated my mother and me with tolerance. Well, that’s a whole other topic.

That was the first episode, with my grandfather. I was born in 1939. That very year, our khutir [hamlet] of Yahidnyi (it belonged to the village of Krasnopillia) was resettled. People scattered, whoever could, wherever they could. Such cellars remained there, impossible to dismantle—they were so sturdily built with lime mortar. We ended up in the khutir of Stiahailivka, near the village of Karylske in the Korop district of the Chernihiv region. After the war, so that I would be allowed to attend the Karylske school, they registered me as having been born in the village of Karylske. Later, once a year, I would walk to Krasnopillia for the patronal feast day. Actually, not to Krasnopillia, but to the church hamlet outside the village of Krasnopillia. It was sixteen kilometers from us. We went on foot. So I saw the place where our house had been and where that khutir of Yahidnyi had stood. There was a lake there, with many ducks on it—my mother used to tell me. Our house stood on the shore of that lake. But by the time I went there after the war, everything was overgrown with sedge; there were only wastelands. But there were still plum and cherry trees on those old homesteads.

The postwar years. My mother would get up early, go to the fields, and return very late. There were no days off. And in a year, she would earn a bowl of grain, and sometimes she would even owe sixteen kilograms to the kolkhoz, for supposedly taking some grain from the kolkhoz. Although she hadn't done it, it was impossible to prove the truth to anyone.

They wouldn't let us gather leftover ears of grain in the field; they would shoot at us. We would hide in the corn, I remember. And then they would plow those ears under. Once, there was a meeting, and Mykola—they called him Baranyk—asked: “Why are you plowing the grain under?” The next day they took him away, and he spent about five years in prison for that question.

At that time, letters of a religious nature were circulating, claiming that somewhere on a seashore a boy had seen the Mother of God in the sky, that she had said something—such omens, according to those letters, were appearing. Under the influence of those letters, in about the third grade—it was still in the hamlet school, which only went up to third grade, and then you had to go to the village school—I went and wrote (it was essentially a leaflet) that Stalin had died and everyone was praying to God. And I tossed it in the hallway. The teacher was Mykhalko, Mariya Lavrentiyivna. And her relative, Brushko Olena, was a cleaning lady. That Olena found the note and gave it to the teacher. The teacher guessed from the handwriting that it was me. (One witness to this story is still alive: Shura Zatskin. He’s in Korop now—the district center). The teacher immediately informed the principal. And the principal was in the village of Karylske, at the seven-year school. His last name was Kochubei. He came, and I was summoned to the teachers' lounge. That teachers' lounge also served as this teacher's, Mariya Lavrentiyivna's, living quarters. There was even a stove there. He yelled at me and told me to keep my mouth shut about what I had done. Because if they had made it public, I don’t know what would have happened to me, but I think they could have been taken away. Well, at the very least, they could have paid with their jobs—both the teacher and the principal.

On September 1, 1955, I published a poem in the district newspaper *Radianska Koropshchyna* [Soviet Korop Land]. It was my first publication. The poem was called “The Lazy Brigadier.” It was a criticism of a communist brigadier. I used that phrase in the poem, but the editor, Pozdnyakova, crossed it out. I didn't know then that you couldn't use words like that: a communist-slacker. You could only name him by his last name. The gist of it was that the lazy brigadier Chaika drank all day at a christening, and couldn't care less that the thresher was in the field. They had sent us schoolchildren to the thresher, and I had already been going there. 1955—how old was I then? Sixteen years old. I started working in the kolkhoz fields with my mother while I was still in school.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: But what about school?

M.K. Kholodnyi: Well, we worked in the summer—weeding potatoes, hilling them up. There were these plows that worked on two sides. We couldn't even climb onto the horses; we could only peek out from behind the plow. So they sent us to the thresher, but he hadn't provided enough people for it. You need someone to feed the sheaves and someone to rake away the straw. It's a whole conveyor line. And there weren't enough people there, so we practically wasted that day and didn't earn anything. We just sat there pointlessly.

After this poem, the first persecutions against me began. I was forced to flee the village. And I fled to Myrorod. They didn't issue internal passports back then.

Speaking of my human rights activities, they can be divided into several categories. The first is my poetry, in which I came out in defense of the social and national rights of the Ukrainian people. This is particularly evident in poems such as “Dogs,” “Uncle Owns the Plants and Factories,” and “Today There Are Horses in the Church...”—this one already has national overtones.

Then there was publicism. I had several publications in the journal *Suchasnist*—it was still being published in Munich at the time. The CPU and the CPSU still existed. I also published in the journal *Prapor* and the newspaper *Molod Ukrainy*. True, in *Molod Ukrainy* that article appeared under the name Okolko—a student with whom I had once studied in Odesa. I was finishing my studies at the university there, and he was at the pedagogical institute. The article was called “Who Will Protect the Crimean Ukrainians?” Another of my publicist pieces was published in a Tatar journal that came out in Feodosia. It was published by Rafik Muzafarov, a Tatar. It was an article about Crimean toponymy, which the Bolsheviks had distorted. In place of historical names, toponyms, all sorts of Krasnogvardeyskis, Pushkins, and Lenins appeared... There was a lot of the color red there, especially.

The third area was my public speaking. For one such speech (at Kyiv University during a discussion of Arsen Ishchuk's novel *Verbivchany* in December 1965), I was expelled from the Komsomol and, automatically, from my fifth year at the philology department of Taras Shevchenko Kyiv University. What’s interesting is that two years later, I was reinstated at Kyiv University after working as a watchman and a swineherd in the Kirovohrad region. I brought back character references and was reinstated at Kyiv University. Then I transferred to Odesa and finished my studies there in 1968. I've been retired for several years now, but it was only in 1993 that Academician Skopenko, the rector of KDU, rescinded the order for my expulsion as unlawful. Justice, so to speak, triumphed.

On May 28, 1966, I read two poems near the Franko monument: “Dogs” and “Ivan Franko's Monologue.” It was the fiftieth anniversary of the Kameniar's [The Stonemason's] death. They grabbed me and threw me in...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: They grabbed you right at the monument?

M.K. Kholodnyi: No, no, they grabbed me when I was on my way home. They grabbed me on Khreshchatyk Street. By the way, Yevhen Sverstyuk had warned me. He must have sensed how it would end. He first went to the conservatory. There was an official event there, by special invitation only. We couldn't get in. And some worker tried to get those who wanted to get in through the stage—Oleksandr Serhiyenko (he's now a deputy of the Kyiv City Council) and his classmate from the medical institute, Valeriy Nabok (Valeriy Nabok died of a heart attack in Chernihiv in 1994)—and they were detained. On Khreshchatyk, they detained Viktor Kovalchuk—a student from the journalism department of Kyiv University—because when some unknown individuals in civilian clothes attacked me (a police “voronok” [paddy wagon] had driven up), he rushed to defend me. So they took him too.

The next day was Sunday. That Sunday, at the court of the Leninskyi district of Kyiv, Judge Pedenko sentenced us to fifteen days in Lukyanivska Prison. The night before the trial, we slept on the floor at the Leninskyi District police station in Kyiv. And the next day, they took us to Lukyanivka, having sentenced us to fifteen days.

We declared a hunger strike there, but they kept us for the full fifteen days anyway. They released me and returned my passport (because I had my passport with me)—and my passport already had a stamp: “Deregistered.” They ordered me to leave Kyiv within twenty-four hours. Which I did, going to the Yahotyn region to guard an orchard at the “Novo-Oleksandrivskyi” radhosp [state farm]. The current member of the Writers' Union of Ukraine, Valeriy Illia (b. June 23, 1939, d. July 27, 2005. – V.O.), was working there as a watchman. He started a dynasty of writer-watchmen. Because later, after me, this profession was mastered by Mykola Vorobyov and Viktor Kordun, who had been expelled from Kyiv University. Somewhere in the journal *Svitovyd* in the United States, Kordun published a photograph: the three of us—Vorobyov, Kordun, and I—in the orchard in the village of Pashkivka... That's in the Makariv district. Across from Makariv, somewhere to the left, on the way to Zhytomyr.

I didn't mention that when I was expelled from Kyiv University, I didn't lay down my arms. They offered to reinstate me at the university at the level of the Komsomol raikom [district committee]. If I hadn't made trouble for them, it might have ended peacefully. But I was already on a roll. I went through all the channels right up to the Central Committee of the Komsomol. I wrote a letter—a kind of confession. That letter was over sixty typewritten pages long. I addressed that letter to the then First Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPU, Petro Shelest, to *Komsomolskaya Pravda* in Moscow, and to Oles Honchar (he was the head of the Writers' Union of Ukraine at the time). This was almost 10 years before the creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group in Kyiv.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: The Group, you mean.

M.K. Kholodnyi: The Group. Although I wasn't a pioneer in this field. I already had, so to speak, teachers who had gone through the great school of political struggle. This struggle took place in the sphere of literary criticism. At the forefront were Ivan Dziuba, Yevhen Sverstyuk, and Ivan Svitlychnyi. But their critical articles had clearly defined political overtones, because by then everyone had come to believe in the “Khrushchev Thaw”... And then in 1963, Khrushchev was provoked, obviously by those who wanted to seize his portfolio, against the intelligentsia, and then against the working and peasant classes. He took away cows in the villages, plowed up lands that shouldn't have been plowed, and they hid grain somewhere... These themes found reflection in my poems.

In that letter to Shelest, I referred to the main articles of the UN's “Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” And it was concealed from the people here. I read it in the *Courier* journal, which I got from a library in Kyiv.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: The *UNESCO Courier*?

M.K. Kholodnyi: The *UNESCO Courier*, because there are many *Couriers* now, and maybe there were others back then too. I also familiarized myself with the constitutions of capitalist countries, I read Jefferson's “Bill of Rights.” I wanted to bring those articles to the people in this way—because the letter spread through samvydav. I heard on foreign radio back then that it had been published in France. And just now, a few years ago, I published it in the regional newspaper *Vinnychchyna*. The letter was published in many issues. They returned this letter to me from the KGB's safes (now it's the SBU archive). There are eight volumes of my case file—that's the investigation of my so-called, and maybe not “so-called,” anti-Soviet activity. Because what's “so-called” about it? Now those quotation marks can be removed. As for the poems, there is a vivid document, produced at the request of the KGB—a review of my book *Kryk z mohyly* (A Cry from the Grave). By the way, I forgot to say that in 1969, in Paris–Toronto–Baltimore in the USA, the Vasyl Symonenko “Smoloskyp” publishing house (the director of this publishing house was Osip Zinkewych) published my book *A Cry from the Grave*. It was a book directed against the national policy of the CPSU. It was a direct challenge. True, it was published under the heading “Clandestine Poems from Ukraine,” without the author's name. But it contained a number of poems that had already been published, and they identified me immediately. Because I also read those poems in public. By the way, I didn't hide them. For this collection and for other poems that were circulating, the KGB arrested me in the winter of 1972.

Actually, I forgot to mention that eviction from Kyiv. I will make some digressions during my story, because not everything comes to mind at once. As for that eviction from Kyiv. Now, wherever I appealed (for example, I appealed to the Prosecutor General's Office), I would receive a reply that my arrest for an administrative violation was not provided for in the law in 1966. Well, all the more reason, if the arrest was not provided for, they should have somehow rehabilitated me and declared the expulsion from Kyiv illegal, right? Because I was registered here on Boichenko Street. I should have had an apartment long ago.

By the way, Vyacheslav Chornovil wrote about that eviction from Kyiv in 1966 and about that arrest, about being thrown into Lukyanivska Prison, in his famous work *Pravosuddia chy retsydyvy teroru?* (Justice or Recidivism of Terror?). (See: Chornovil V. Works: In 10 vols. – Vol. 2. *Justice or Recidivism of Terror?*. *Woe from Wit*. Materials and Documents 1966 – 1969 / Comp. Valentyna Chornovil. Foreword by Les Tanyuk. – K. Smoloskyp, 2003, – 906 pp.: ill. The mentioned work on pp. 71 – 359, about M. Kholodnyi – on pp. 353-354. – V.O.).

This is a work from the sixties. He ended up behind bars for it, by the way. And some thirty years later, Ukrainian President Kuchma awarded him the Shevchenko Prize for it. (Also for *Woe from Wit*. – V.O.) There was a list of those repressed extrajudicially and judicially. I was number thirteen on that list. It was stated that I, Serhiyenko, Nabok, and Kovalchuk were convicted with the wording: “For an attempt on the life of a police officer.” For such an accusation, we should have gotten about ten years, no less—but they gave us fifteen days. Of course, it was a phantasmagoria of the judge and those directors who orchestrated all of it to compromise us. And just this year, in February, the Kyiv City Prosecutor's Office and the Kyiv People's Court (the judge, I think, was Hryhoriy Zubets, and the prosecutor, I believe, was Abramenko, and another one—the deputy prosecutor of the city of Kyiv, I forget his name) made a “Solomonic decision.” The three of them—Abramenko filed a motion, the deputy prosecutor of the city of Kyiv approved that motion, and the Kyiv city judge rescinded that ruling by Judge Pedenko from May 29, 1966.

By the way, when the KGB arrested me in February 1972, the story of the speech at the Ivan Franko monument was part of the case file. We also laid flowers there. Oksana Meshko was there. We sang a few songs. And the whole park was filled with police. What were you asking me about? I forgot.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Please detail the procedure of your expulsion from the Komsomol and the university. With dates, if possible. Who took part in that spectacle?

M.K. Kholodnyi: This is how it happened. I spoke at the discussion of Professor Arsen Ishchuk's novel *Verbivchany*. It was, I think, on December 5, 1965. And on the sixth, I believe, the order was issued. There was a Komsomol meeting for our year, then a faculty meeting, then the university's Komsomol committee met. At the Komsomol meeting for our year, the students mostly spoke out for me, in my defense.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Do you remember which of your classmates defended you?

M.K. Kholodnyi: I'll tell you who spoke... Mykola Chyshchevyi especially spoke in my defense. Then there was the faculty Komsomol meeting. Hoshovskyi—the secretary of the university's Komsomol committee—came to that one (he later became a lecturer at the pedagogical institute). He was set against me. Petro Kononenko was also set against me...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Petro Petrovych?

M.K. Kholodnyi: Petro Petrovych. Because I was also in charge of the “SiCh” literary studio there. He really didn't want me to be elected head of the literary studio.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: “SiCh”—the Vasyl Chumak Literary Studio.

M.K. Kholodnyi: Right, the Vasyl Chumak. By the way, they never actually removed me as head of the Studio, so from a legal standpoint, I still consider myself the un-re-elected head. True, the Studio was later renamed after Maksym Rylskyi. And it came to be led by a professor with the symbolic surname Dubyna, Mykola. [Dubyna means “oak grove” but can also be a pejorative for a stupid person—Trans.] He was the one who compiled some book about the so-called Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists abroad, *The Seal of Bloody Cains*, or something... He made things up there, like that Yar Slavutych had supposedly served in the SS “Galicia” Division, but he never served there. Yar Slavutych responded to him in the press somewhere. I know this story because my book about Yar Slavutych is currently in typesetting at the “Dnipro” publishing house—he is a poet, an outstanding Ukrainian scholar, lives in Canada, and during the war, he commanded the insurgent detachment “Chernihiv Sich.”

Even Professor Arsen Ishchuk spoke in my defense. But nothing could be done—the machine had been set in motion, they needed to find some pretext. What did they actually latch onto? That novel by Ishchuk, *Verbivchany*, was nominated for the Shevchenko Prize. Oleksa Zosenko asked if anyone would be speaking. And Oleksa Zosenko—he's a literary scholar, a literary critic—was playing first fiddle there. He lost to Ishchuk at billiards at the Writers' Union. And everyone there plays billiards without having any money. And whoever loses, the bartender puts on a “blacklist.” The worst thing for her was when the man who lost suddenly died. Well, Oleksa Zosenko lost to Arsen Ishchuk. So he says: “I have no money—I'll help you get your novel nominated for the Shevchenko Prize.” And that novel wasn't worth a damn. And so he didn't get the Shevchenko Prize.

The Studio, where I spoke, met in the yellow building of the university. Andriy Kabaliuk was sitting next to me. He writes poetry. I don't know, maybe he's even been admitted to the Union. So I asked him: “If they kick me out of the university, will you give me a ten-ruble note for bread?” He says: “I will.” Then I say: “I'd still like to say a word.” And no one, neither the professors nor the students, had read that novel. They were praising the language, saying it was interestingly written, but no one said anything specific. So I opened it in the middle (I hadn't read it either), and there was an episode where they bring some innocently arrested person to a prison, and its employees, these wardens, speak Ukrainian. I said: “This doesn’t meet the requirements of socialist realism for a truthful depiction of reality. Where have you ever seen a prison in Ukraine where the officials communicate in Ukrainian?” And that was enough. This was assessed as nationalism. And the carousel for my expulsion started spinning. Besides, in August of that year, 1965, a wave of arrests swept through. And I was acquainted with Mykhailo Horyn. We went together to act as a matchmaker for a girl, Tereza Tsymbalynets, in the Svaliava district of Zakarpattia.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: For whom were you matchmaking?

M.K. Kholodnyi: For me. Mykhailo Horyn was the matchmaker (`svat`). And then he went to the Black Sea. I didn't know he had gone there. He even sent a telegram saying he would be late. And it turns out, the leaders of the Ukrainian national movement (essentially, the Ukrainian national underground) were gathering there. Mykhailo Masiutko was there (I know this now because they were all arrested then), and Ivan Svitlychnyi was there. Well, I don't know about the others. So, Tereza and I went to the unveiling of a Shevchenko monument in Sheshory, in the Ivano-Frankivsk region of Prykarpattia. I saw Vyacheslav Chornovil there, Zinovia Franko. Hrytsko Sahaidak from Troyeshchyna came in his “Pobeda” car. He has published a book now, maybe two. But they forbade the unveiling of the monument back then. By the way, the author of that monument was the famous sculptor Ivan Honchar, in whose school (and not just me, but my whole generation) I received a national upbringing. They didn't unveil that monument then, but they did about a week later, without any people.

Well, the KGB agents, so to speak, got on my tail. On the way to Svaliava, I stayed behind in Berehove. My friend, Kolia Horyn from Kyiv, was supposed to send me money there—my honorarium. I wasn't rich back then. And I forgot that we had changed the plan: he sent the money to Rakhiv. And I thought he would send it to Berehove. And by the time I arrived, everything had changed for that Tereza Tsymbalynets. And we were already preparing for the wedding the following Sunday. I didn't know why. She accused me of having some female acquaintance in Berehove. But I had stopped there because I was waiting for the post office to open. And we had arrived there very early. It turned out (she told me this many years later) that as soon as she got to the village council, the head of the council, who happened to be her relative, called out to her and said: “They're summoning you to the KGB.” Well, she took a bus to the KGB in the district center, Svaliava. There, some guy started asking her: “What counter-revolutionary plans were you and Kholodnyi hatching?”—because we had been walking near the forest. Well, what plans were we hatching? We were hatching plans to have fewer people see us, to kiss somewhere, or what do I know... You know what plans a young man hatches.

And then the guy who had grabbed her by the shoulders and terrorized her was killed in a motorcycle accident.

When I returned to Kyiv from Tereza's, I no longer lived in the dormitory. I was registered at Alla Horska's place, but I was living at the artist Mykola Storozhenko's place at the so-called Kulzhenko's dacha. These are art studios, there, beyond Shevchenko Square, in Kurenivka. My things were in Storozhenko's wardrobe; I left what I didn't need there. I took my passport with me, but I left my military ID and my Komsomol card there. The dues were paid. And so when the KGB agents conducted a search there, the military ID was there, but the Komsomol card was missing.

The next day, when I spoke at the university during the discussion of Ishchuk's novel, I was immediately summoned to the university's Komsomol committee and they asked me: “Where is your Komsomol card?” I ask: “What's the matter?” “Well, his wife found it in Kurenivka.” “And why did she find it there? The dormitories are on Lomonosov Street.” “No, no. She found it on Lomonosov and brought it to us.” But it turns out, the KGB agents had stolen the card from my pocket and wanted to play on that. They waited three months, thinking I hadn't paid my dues. But we had paid the dues about six months in advance because our Komsomol organizer was going somewhere to the virgin lands, for some job, and they were returning in late autumn. So the dues were already paid. In short, they accused me of losing my Komsomol card. They promised they wouldn't expel me from the university. But they did expel me, from the Komsomol and then from the university.

When I was summoned to the Komsomol committee, they didn't know what to ask for a long time. Then someone stood up, I think it was Hoshovskyi, or his deputy, and said: “The floor is given to the representative of the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics, so-and-so.” And he asks me: “Why do you wear a beard?” I had a beard, maybe a millimeter and a half long, I measured it. And at that time there was a campaign against beards. Someone was just telling me recently—I think it was Petro Volvach—that somewhere in Crimea, they told some dean or rector to shave his beard (he really did have a beard). He didn't shave it, so they immediately fired him from his position as rector or dean... Maybe I'll recall the name of that scientist who paid for his beard during our conversation.

Right, so he asked: “Why do you wear a beard?” I thought: what should I answer? I had three hairs sticking out there... And right in front of me hung a portrait of Karl Marx. So I answered: “You should ask Karl Marx about that.” Oh, they just flared up at that: “You see, he’s hostile to Marxism-Leninism! Let's expel him! How can he remain in the Komsomol?” These hearings on my case went all the way to the Kyiv Oblast Komsomol Committee. There was a guy named Kornienko there then; he later became, I believe, the first secretary of the Kyiv city or oblast party committee. The city committee. He was a careerist. He asked me: “And why did you...?” And back then I had also written a work called *About the Soul in Song and Song in the Soul*. It was later published in Italy, in Rome. The Vatican even awarded me some honorary prize for it. This work was later published abroad as a separate monograph by “Smoloskyp,” in Rome in 1979, and in Baltimore and Toronto in 1981. They awarded me the prize in 1979.

So Kornienko asks: “And why did you mention Savchuk in your work? Don't you know he lives abroad?” I say: “Not Savchuk, but Ulas Samchuk.” When they familiarized me with my archival criminal case from 1972 around 1992—because I hadn't been familiar with it before—there was a transcript of that meeting of the oblast Komsomol committee, about thirty or fifty pages long. By the way, I asked, and they gave me that transcript from the case file. I'll publish it somewhere someday.

I had a house. In 1972, I was deregistered again—this time from the Kyiv region. I was living in Mykulychi. I had a house, I had a plan for a new house, I wanted to build it. But a bulldozer tore that house down, and I was exiled to Vinnytsia. There, I was essentially under house arrest.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: From what year were you in the Vinnytsia region?

M.K. Kholodnyi: From 1972, around the summer. I worked in a school there. Then the situation there became unbearable; I was “taken to task” for so-called nationalism several times. I left that place. I was unemployed for a while, and then I got a job at a museum. They slandered me there, claiming that at the Tyvriv museum I had ordered that exhibits not be labeled in two languages—Ukrainian and Russian. But I had never even been to the Tyvriv museum, nor had I ever been to Tyvriv. The court acquitted me, but the museum director, Zayets (and he was a professional KGB agent, he headed the veterans' council at the Vinnytsia Oblast KGB directorate) said: “I'll put you in prison anyway.” So I fled from there to Oster and later ended up in the Chornobyl zone, because when the reactor exploded, Oster fell into the Chornobyl zone.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And you've been in Oster since what year?

M.K. Kholodnyi: Since 1976. I was cut off from cultural life there. I just live there, as if in a ghetto, because the city library doesn't receive a single Ukrainian journal. And to order a book through interlibrary loan, for example, you have to pay money. And to come to Kyiv, for instance, to get something—you can't read a book in one day, if you need to do it somewhere like the Vernadsky National Library or somewhere else. That means you have to spend the night. And staying in a hotel is several times more expensive than the trip itself.

Then the head of the Verkhovna Rada commission on national spiritual revival, People's Deputy Les Tanyuk, sometime in the early nineties—by the way, right before the GKChP putsch—appealed to the Kyiv City Council to grant me a one-room apartment in Kyiv, because I wasn't claiming anything more. He argued that since the time I was evicted from Kyiv, and later from the Kyiv region, I would have already received housing through my place of employment. And when the KGB arrested me in 1972, I was working as an engineer at the Central Normative Research Station of the Ministry of Land Reclamation and Water Management of Ukraine, on Kavkazka Street. And before that, around 1967, or more likely 1968, I was working as the executive secretary of the Society for the Protection of Nature of the Zhovtnevyi district of Kyiv. I was summoned to the Zhovtnevyi district executive committee, by some guy named Tokarev. And it turns out, in 1965, he had reviewed my case in the district Komsomol committee and knew me. As soon as he heard I had ended up in that district, he said: “How could we allow this? We have fourteen thousand workers here. And you were here as a nationalistic element?!” He took away my certificate as secretary of the Society for the Protection of Nature. The next day I was dismissed “at my own request.” I was hired through the city branch of the Society for the Protection of Nature. Serhiy Bilokin's father helped me with this—he was an academician, a wonderful person. He helped me get the job because he himself was a biologist. And the city society was headed by Ivakh. Ivakh was then summoned to the city party committee—and he had a minor heart attack there. The son of the writer Inna Kulska knows this very well. He himself is now a member of the Writers' Union, Ihor Moiseyev, my friend; I lived with him when I had nowhere to live. But then they found out about this letter from Les Tanyuk from the Verkhovna Rada about my return to Kyiv. The KGB found out—and they tripped me up. And so to this day, I am burning on a slow fire in that Oster reservation.

What else did I forget to say? You can ask a question.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: 1972. That arrest—I don't even know the date you were arrested. What were the motives, what charges were brought against you?

M.K. Kholodnyi: Alright, then. By the way, you asked who spoke against me at the university. Volodymyr Zabashtanskyi (b. Oct. 5, 1940 – d. …………) played the most shameful role there. By the way, I used to write poems for Zabashtanskyi, literally write them. It wasn't just editing; I had to write them for him myself. I used to walk him home on Frunze Street because he was blind. Then a legend spread in the Komsomol bodies that he had supposedly lost his hands and eyes while quarrying granite for Lenin's mausoleum. But in reality, it happened under domestic circumstances. They were trying to detonate some kind of explosive charge in a quarry, having taken it from the workers. As a result of an accident, he became disabled. So he played a very shameful role then because he was a member of the literary studio. And before me, the literary studio was headed by Ivan Drach, and before me, Valeriy Shevchuk—so the literary studio ignored the socialist realist canons. Petro Kononenko was constantly sitting in the back row. Zabashtanskyi was immediately accepted into the party, and then into the Writers' Union of Ukraine. Then he was given the Mykola Ostrovsky Prize—that Ukrainophobe—and then the Shevchenko Prize.

So Zabashtanskyi, by the way, sent me a letter sometime at the beginning of, I think, 1988, and suggested that I should repent for the collection *A Cry from the Grave*. I went to see him. And the manuscript of my collection was at the “Radianskyi Pysmennyk” [Soviet Writer] publishing house. It's now called “Ukrainskyi Pysmennyk” [Ukrainian Writer]. He, you could say, “ratted me out,” because during the investigation I said that I had not sent the collection abroad. But in 1988, he was speaking at our literary studio in Chernihiv. He got drunk, couldn't come to the session for a long time (he was there with Mykola Tomenko—also an author of songs about red horsemen, etc.). So Zabashtanskyi spoke and said that he, meaning Kholodnyi, was, supposedly, ‘still proud that his book *A Cry from the Grave* was published abroad.’ That I had even been walking down the street back then telling him that I gave the collection that title and sent it abroad.

By the way, Petro Kononenko wrote a character reference for one of our students to enter graduate school (and she did finish it). And in the reference, he indicated that she had helped him fight against me, Kholodnyi, back when I was the head of the literary studio.

So you're asking about 1972, when they took me?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: The date of the arrest, what charges were brought? Where, under what circumstances were you arrested?

M.K. Kholodnyi: They were looking for me... At the Samhorodok school, where I worked, there were no teaching hours for me. That is, they found out there that I was a politically unreliable type. And I was fired from my job while I was in the hospital. This was in the Skvyra district. At that time, I had the imprudence to submit my poems to the journal *Duklia*, and they were published in 1967. There was a poem there:

Зацькований, цілую п'яти, зв'язані Сергієві, сохну в поезії, дійку обвиваю вужем. Друзі, якщо впізнаєте мене на вулиці в Києві, вдарте, будь ласка, під ліву лопатку ножем.

I was undergoing surgery on my middle ear at the Kyiv Oblast Hospital, and during this time I was fired from my job at the Samhorodok school in the Skvyra district. Because the head of the raivno [district department of public education], Brovko, to whom I had given that journal to show off that, you know, I was even being published abroad in the publications of socialist countries—he took it to the raikom [district party committee]. So I paid for my naivety.

And then I worked in Kozyntsi in the Borodianka district. I only worked there for a year too—KGB agents were already following me, escorting me from the electric train all the way to the village. Because I often spent the night in Kyiv and traveled there for work. The principal there was a certain Chervanskyi. By the way, I read his character reference for me in the KGB file, in that criminal case against me, just now, in 1992. He wrote that “I was not familiar with his poems, but they were of an anti-scientific character.” And he hadn't even read them...

I then bought a house in another village, in Mykulychi. It wasn't far to walk from the electric train. By the way, I bought that house with Vasyl Stus, because I was afraid someone might rob me of the money. So Vasyl Stus was holding the money. I bought the house for a thousand of the then-currency, those Soviet rubles. That was in 1969. We agreed on nine hundred and fifty, but when we went to finalize the deal, the old woman said a thousand—she added another fifty. And it turned out she had been selling it for only five hundred before. We went to look for the money, we had to find another fifty rubles. We come back, and the old woman says she doesn't need the fifty rubles anymore. “Why?” And she says: “I was chopping wood—I broke my arm. God punished me for agreeing to nine hundred and fifty and then trying to take another fifty rubles from you.” So she sold the house for nine hundred and fifty.

I stayed there for a year. And then the head of the raivno summons me, says: “Listen, you don't have your documents. We'll have to dismiss you from your teaching position.” But the school year had already ended. I go to the principal—his name was Yaremenko. He asks: “Why did they summon you to the district office?” I say: “They're taking me to the Teacher Training Institute, so I need a character reference.” He wrote me a positive reference—thinking it was a way to get rid of me.

And that head of the raivno in Borodianka, whose surname was Dvornyk, he was angry: “If I had met you somewhere on the front, I would have shot you on the spot.” I say: “And what makes you think you would have shot me, and not the other way around?” Well, he fell silent after that. So with that reference, I went to Ivan Svitlychnyi and asked: “What should I do?” He says: “Do you know who fired you?” “Who?” “It’s obvious who—the Okhranka fired you. That's who you should call.” “Who?” “Well, call him... You won't get through to Nikitchenko, he won't see you. Call Shulzhenko.” Well, I didn't call Shulzhenko—I went to the Central Committee, I think to Tsmokalenko, and Tsmokalenko called Shulzhenko. Well, they had no power there in the Central Committee—they knew the KGB did everything. I went to KGB General Shulzhenko. But Shulzhenko said: “We know, your works are abroad, some not even published yet.”

They led me on and on there in Borodianka and, in the end, they had a full staff, and so I was left without a job. I got a position as an engineer. Viktor Nikiforov and his friend Fedir Volvach helped me with this. They helped me get the job, even though I had a philological education.

I was on a business trip in Zhytomyr when the arrests were happening here. Specifically, at Yevhen Kontsevych's place. In 1965, for Kontsevych's birthday on June 5, Oksentiy Melnychuk—some local writer—brought an album, and a listening device was mounted in the head of a little dog statuette inside the album. Yevhen discovered it. Dziuba then spoke of this album as a new method of educating literary youth. Kontsevych had an embroidered towel on which guests would sign, and his wife would later embroider these autographs. My signature was there too.

So, in January 1972, I was on a business trip at a construction management office of the Ministry of Land Reclamation system. I was working as an engineer in the department of construction materials expenditure. Kontsevych and I read in the newspaper that arrests had taken place in Kyiv. When I returned to Kyiv, I met with Fedir Volvach. Volvach says: “They've already been to my place. They were asking for you.” Then I showed up in the village, in Mykulychi. A neighbor told me: “They asked for you, that you should stop by the village council.” When I was buying a travel pass—my pass for the electric train had just expired—the station master looked at me very suspiciously. And some rank-and-file employee of that station told me: “Get out of here quickly, because either the police or the KGB are looking for you.” I spent the night in Kyiv, not showing up at home in Mykulychi. Well, I hid whatever samvydav I had.

By the way, I didn't mention that I distributed samvydav. Once, Vasyl Stus (I was going to Donetsk) gave me a speech, I think by the Pope or by Yosyp Slipyj, to pass on to Volodymyr Mishchenko. I passed on this material. Then I passed on other samvydav documents. Mishchenko now lives somewhere in the Dnipropetrovsk region, I think—he moved somewhere then. By the way, he was the editor of my first book published in Ukraine in 1993 by “Ukrainskyi Pysmennyk”—*Doroha do materi* (The Road to Mother).

I was hiding illegally in the settlement of Vyshneve—that's Zhuliany, at Viktor Kordun's place. We noticed there that a spy was following me on the platform, hot on my heels. I came to Kyiv, spent the night somewhere, met with the artist Borys Plaksiy, and then went to a meeting at a pharmacy. The pharmacy was on Franka Street, on the corner. There was a pharmacy on one side and a shoe store on the other. So I met there with Valia Malyshko. She was either Malyshko's wife Liuba's niece or something—I had a brief relationship with her. (b. Dec. 29, 1937 – d. May 17, 2005. – V.O.). With her and with a certain Petlychka. Her last name was Petlychka, I forget her first name. She lived in Bessarabka. She said her father was a party official, but maybe he worked for the KGB? She had a communal apartment. I then saw that some... A KGB officer, young, married, lived there. So I'm walking with this Petlychka to meet Valia (she had told me that Valia Malyshko would be coming). And Valia was there. Just as I passed St. Volodymyr's Cathedral, I see—several white cars are parked there. The license plates were 05, I think. My heart immediately sank, knowing they were coming for me. Well, where could I run—you can't run far, where can you go? I went up to the girls and kept looking at those cars... And for some reason, Valia ran home, supposedly to change clothes. I'm looking at those cars, and Petlychka says: “Don't look in that direction.”

Then Valia came back. We're walking towards the opera house, and I say: “I'll get some beer.” She, that Petlychka, says: “Oh, I have something to drink at my place.” We go to Petlychka's home. She says: “Go into this store and buy it.” And I think: “No. I won't go in there, they'll grab me here, it's two meters to the KGB—they'll drag me away, and no one will even see.” I say: “No, I'll buy it downstairs, on Khreshchatyk.” There's a grocery store on Khreshchatyk, across from the department store. I go in there, get some beer, probably two bottles. And Petlychka said: “Get some cigarettes for Valia and me too.” I got the cigarettes, come out of the store—they're gone. I thought they had slowly started walking home. Thinking I would catch up with them on Khreshchatyk. Just as I reached the “Sporttovary” [Sporting Goods] store—they grab me by both arms: “Mykola Kostiovych?” I screamed: “Fascists!” Or something like that. And they dragged me into one of the white cars that were parked there. I later saw one of these cars on the grounds of the pre-trial detention center, on Irynynska Street—it's here, where Volodymyrska is, that car was parked. It was something like 05-20 KIA, or something. They took me to the oblast KGB. They fussed around with something for a long time, because it might have even been a Sunday. They fussed for a long time until they took me to that KGB pre-trial detention center.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: What date was that?

M.K. Kholodnyi: It was February 20, because the wave of arrests had swept through around February 12...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: January 12, 13, and 14.

M.K. Kholodnyi: January, I'm sorry. But I was on a business trip in Chernivtsi then. I didn't want to wander around Kyiv. I was in Konotop, visiting my mother. I took all the photographs I had to my mother. Because there were a lot of friends, dissenters, and if that photo archive had fallen into their hands, a lot of people would have suffered. They came to my mother's with a search warrant sometime in March. My mother noticed them in the yard as they were walking: the head of the village council, Borys Kotok, Berestovskyi went there...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: I know KGB investigator Leonid Berestovskyi. He started my case on March 5, 1973. And then he handed it over to Mykola Tsimokh.

M.K. Kholodnyi: This Berestovskyi did his practicum in 1965 on Vyacheslav Chornovil. Chornovil really laid into him then! He showed his incompetence. So they transferred him to Khmelnytskyi. By the way, at that time they transferred Tamara Hlovak, who worked in the Central Committee of the Komsomol, to be secretary of the oblast committee (I don't know if that was a demotion or a promotion)...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: She was the second secretary of the Central Committee of the Komsomol, right?

M.K. Kholodnyi: Yes, for ideology. When they kicked Shelest out to Moscow after my arrest—it was almost synchronous—and Shcherbytskyi took over... Because it was supposedly Malanchuk who ratted on Shelest, saying he had allowed nationalism to flourish... Then Shelest's book *Ukraina nasha radianska* (Our Soviet Ukraine) came out. Its title was graphically arranged in such a way that it could be read as “UNR” [Ukrainian People's Republic]. So he was later accused in the journal *Komunist Ukrainy* of autarky—of wanting to run things here independently of Moscow. Well, there was something to it, that he had a falling out with Suslov over some Dutch oil cake: Suslov wanted to take it for Moscow, and Shelest for Ukraine—for the cows, for the farms.

The first thing they charged me with then was the collection *A Cry from the Grave*. There were long and tedious conversations. The interrogations were conducted by Berestovskyi. They took me in warm clothes, because it was winter. So I wrote a note there and wanted to smuggle it out in my clothes... I had to somehow continue the fight with them. There, in the conditions of the pre-trial detention center, I couldn't imagine how to fight them. I wrote a kind of appeal-statement to the prosecutor of Ukraine, in which I expressed a sharp protest in connection with my arrest. That they had snatched me just like during the German occupation—grabbed me right off the street. And for what? For nothing! No, they knew what for... I wrote that statement in several copies. I hid one in my shoe—the sole had been cut open. I had felt boots... I don't remember, maybe even in both shoes. I hid it behind the heel counter in the shoe, and I hid the other one in the nightstand. I took the lid off the nightstand and put it under there.

Then they put some guy named Klymchuk in my cell—he was supposedly in for stamps. Well, it was so he could wear me down psychologically.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: That's a must—an informer in the cell was a must.

M.K. Kholodnyi: That's probably why they put him in with me, to find something out, to involve me in something. Yevhen Proniuk figured him out. Proniuk later told me that they had put him in his cell. That Klymchuk said he was in for some refrigeration units—supposedly he repaired refrigerators and took bribes. And for some stamps from Scandinavia, as a philatelist. His name was Klymchuk Oleh, he was from Chervonyi Khutir. He said that when he got out of prison, he would accept glass containers at some pavilion, that he would buy an old “Zaporozhets” and make a fortune. Indeed, when I got out, I was curious: had he gotten out or not? So once I visited him with Vasyl Skrypka (b. April 16, 1930, dismissed in 1972 from the Institute of Art History, Folklore, and Ethnography for political reasons. From 1986 – professor at the Department of Ukrainian Literature of the Kryvyi Rih Pedagogical Institute. Died Sept. 19, 1997).

Indeed, everything was going according to plan—he got a job accepting bottles, or maybe they helped him. He bought a humpbacked “Zaporozhets.” And when I visited him a second time, the house was overgrown with weeds. The part where he lived was shared with his brother. So his part was overgrown with weeds, not whitewashed on the outside. It was clear that he had gotten into trouble again somewhere.

What else? I had an interesting confrontation with Zinoviy Antoniuk. Antoniuk had some of my books. I was the godfather to his wife's sister's children, and Ivan Dziuba was the godfather to Zinoviy Antoniuk's child. We had such, so to speak, distant, symbolic family ties. So I would occasionally spend the night at Antoniuk's. Long before the arrest, I brought him Valentyn Moroz's *Instead of a Final Word* and some other samvydav. So I took the blame for that. I knew they had found *The Ukrainian Herald* at his place (I had given information to it myself, I distributed this *Herald*). I think they found one copy of *The Ukrainian Herald* at his place. This came up somehow, either at the confrontation or somewhere else. So I took the blame for it—I said I had brought him the *Herald*. But actually, I hadn't brought him the *Herald*. Larysa (?) knows that I took the blame for it then. Well, Antoniuk said that I had brought this *Instead of a Final Word*. They asked me where I got it. I said that some guy named Vasyl gave it to me, and I don't know him from Adam. Somewhere in a café, where Paradzhanov lived, there was a varenyky place. I say, I don't know him, I was drunk at the time and I don't know who he is. I tried, so to speak, to cover my tracks.

What else did they incriminate me with? They searched my home—but they found nothing there. In the wardrobe, under the glass, under the mirror (I once bought the wardrobe at a second-hand store, we bought some other furniture with Paradzhanov)—I had hidden a typescript of Yevhen Sverstyuk's work *Ivan Kotlyarevsky Is Laughing*—they didn't find it. But they did find—well, I didn't hide it—Dovzhenko's *Diary*. Oles Serhiyenko had given it to me once. I didn't say where I got it. By the way, that *Diary* was reprinted from Soviet editions—from Dovzhenko's *Dnevnik* in Russian. I also had a clipping from some newspaper on the door of my room, which I had partitioned off, maybe from *Pravda*, about Khrushchev's dismissal to retirement. So they tore off that clipping and took it. They took a book, a small brochure about yogis. Ihor Moiseyev had published it back then. He worked at some medical publishing house—I don't know what it was called... Somewhere there behind the Verkhovna Rada he worked. So they didn't return those books to me. Probably some KGB officer took them for himself. They searched, dug around under the peat in the shed, poked around there—they found nothing there. One guy climbed onto the stove, looked in the chimney—he didn't find anything there either.

But at my mother's... I don't know where those photographs were—there was a whole bundle of them. My mother saw the KGB agents in the yard and quickly hid the bundle in the pich [large stove]. And they didn't go into the stove. They found a few of my letters to my mother in a drawer—so they took them.

And my papers (there were a lot of them) I gave to Danko Dmytro in Nemishayeve. By the way, his godfather—the local police officer—lived next door to him. And it turns out, he was watching me, but he didn't report anything about me. Although he knew well what spirit we were breathing then—an anti-Soviet spirit. He didn't rat me out anywhere. What's interesting: Danko took all those materials in a plastic bag and lowered it into a well—in the winter! It would have been a piece of cake for that bag to tear, everything would have gotten soaked, or a bucket could have... And it was a well shared with the police officer! He could have scooped up that package. But the bag was intact. It stayed there until the end of the summer of 1972. When I came from Vinnytsia, he gave it all back to me.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Nothing got wet?

M.K. Kholodnyi: No, it didn't get wet. Actually, it wasn't like that. I didn't come from Vinnytsia; the KGB released me for one day. They brought me to the village of Mykulychi and told me to pack my things. And Svitlychnyi's trial was happening at the time (April 27–29, 1973. – V.O.). I was asked a question: had Svitlychnyi given me any advice? The lawyer asked. I said he hadn't. They asked if we had exchanged samvydav. By the way, they also asked this at Stus's trial. I said there was no exchange of literature either with Svitlychnyi or with Stus and that there were no anti-Soviet conversations or conversations on political topics. These were stereotypical questions; they probably asked everyone.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: You were summoned to the trials of Stus and Svitlychnyi?

M.K. Kholodnyi: Yes. I've already mentioned Danko Dmytro, that he saved my archive. But, it's true, when I was carrying that bundle and opening the house, some photographs fell out in the yard. I didn't notice. And then in the morning, Berestovskyi arrives. He must have understood very well the origin of those photos scattered around the yard, but he kept silent. Although he could have reopened the investigation. But he kept silent.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And were any poems incriminated against you?

M.K. Kholodnyi: Oh, the poems—that was terrible! I've already mentioned that there was a review of the collection *A Cry from the Grave*.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And who wrote it?

M.K. Kholodnyi: I believe it was Anatoliy Kovtunenko, a senior research fellow from Shamota's Institute of Literature, from which Stus had been expelled from graduate school. And Stus, by the way, wrote about this reviewer Kovtunenko. In my criminal case file, there is one letter. The KGB addresses the director of the Institute of Literature, Shamota, asking them to review the collection *A Cry from the Grave*. Then there is a response from Shamota, that they have already reviewed it. But, what's interesting, the letter to Shamota arrived around the 20th or 21st of February, and Shamota already replies to the KGB on the 23rd that it has been reviewed.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: They were quick to fulfill KGB orders.

M.K. Kholodnyi: Quick. But, what's interesting is that the review is dated somewhere around March 3rd, or even March 23rd. Apparently, Anatoliy Kovtunenko didn't write it correctly. So, it seems, they dictated to him at the KGB how it should be written, so he was probably adding to it. Because the date is completely different from the one Shamota reported. There, Kovtunenko wrote that in my collection *A Cry from the Grave* I call on the people to armed rebellion, to take revenge on the working people for their loyalty to the socialist Motherland, that I harbor delusional ideas of restoring a bourgeois Ukraine, and something else like that. If it had been in the 30s, for such an accusation, they would have put me up against a wall—that's for sure.

Right, which poems did they appeal to? To those that were deemed anti-Soviet, nationalistic. Poems like “I Am a Foreigner Among You,” “Ivan Franko's Monologue,” “Today There Are Horses in the Church...,” “Uncle Owns the Plants and Factories...” They were particularly bothered by my poem “The Ghost”—it's a classic poem. By the way, Tsimokh, the one who now works somewhere in the presidential administration, he would quote my poems by heart. The artist Boychenko told me this—he worked there too.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: He still quotes them?

M.K. Kholodnyi: He still quotes them.

And then in some year, eighty-something, maybe 1989, the then-prosecutor of the still-UkSSR, Potebenko, acknowledged that there was nothing anti-Soviet or slanderous in the collection *A Cry from the Grave* (because they called these poems slanderous). I then appealed to the prosecutor's office and the oblast prosecutor's office rehabilitated me. But I was not reinstated at my place of work at that normative station, nor at my place of residence. The same goes for the second rehabilitation: the order to imprison me in Lukyanivska Prison in 1965 was rescinded, but nothing more was done. Neither the judge nor the prosecutor's office even mentioned that my residence in Kyiv should be restored. And that I was deliberately thrown out of my job at the Society for the Protection of Nature—that was to ensure my foot would never be in Kyiv. And they achieved that.

I also haven't mentioned that around 1969, they kicked me out of the “Slovo” cooperative of the Writers' Union. I had already made a down payment there. Everything was done to get rid of me from Kyiv. Now, those tormentors of mine are walking their dogs under the Kyiv chestnut trees, receiving good pensions on time, while I'm swallowing radionuclides in the Chornobyl zone.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: You mentioned investigator Mykola Ivanovych Tsimokh. He also handled my case in 1973.

M.K. Kholodnyi: Yes. And he made up, as far as I know, that he handled my case too. We were young and inexperienced back then. Do you think they didn't set traps for me? You had to be constantly on the lookout not to get caught in some trap. This Tsimokh made up that he had already broken me.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: That's what he told me himself.

M.K. Kholodnyi: You see what kind of person he is. There's not even a hint of conscience there.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: But I was charged with distributing your poem “Today There Are Horses in the Church...”—as anti-Soviet. That's one of the episodes in my sentence.

M.K. Kholodnyi: Well, there you have it. And Tsimokh—I don't know him from Adam. My case was handled by Berestovskyi.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: This Berestovskyi also started my case, handled it for about a month, and then handed it over to this Tsimokh. That's the story.

I think it's starting to rain?

For the most part, you've told the story of this case. It fits on one cassette.

M.K. Kholodnyi: You know what I haven't mentioned yet? The distribution of samvydav.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: I was just about to ask about that: what kind of literature passed through your hands? Who did you get it from—if you can say?

M.K. Kholodnyi: You know, once Chornovil (may he rest in peace) went and told everything, who he got what from, who he passed it on to. It seems to me it's premature to talk about this. We probably must hold out to the end, because if the communists make a comeback, silence will no longer save us. I've already written so much against them during the years of independence that they'll do what their predecessors did with the “Executed Renaissance” in the twenties and thirties.

As for what materials passed through my hands. I received samvydav from Ivan Svitlychnyi, from Ivan Dziuba, Vasyl Stus, from Chornovil, from Henrich Dvorak (he was a representative of the technical intelligentsia), from Lionia Pliushch (he's still alive). A lot of material came from Moscow, especially through Pliushch from Sakharov. I remember materials by Veniamin Kasterin and Petro Hryhorenko in defense of the Crimean Tatars. They weren't allowed to return to Crimea back then. I read such materials and passed them on. Then Valentyn Moroz's “Amidst the Snows,” “A Report from the Beria Reservation.”

Maybe we should go somewhere under a tree?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: There's a gazebo over there.

M.K. Kholodnyi: As for samvydav. From Viktor Nekrasov I received Amalrik's work in Russian, *Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?* Ivan Dziuba ironically commented on this title at the time—he said that the Union will survive until 2084, but will Amalrik survive until 1984? And indeed, Amalrik went abroad and was traveling somewhere in Switzerland with Fainberg, a non-conformist artist. They were traveling in a passenger car, I believe, to the Madrid conference on Helsinki-75. There was some international conference on this topic. They collided with a truck and Amalrik was killed. So Dziuba's words turned out to be prophetic.

But, what's interesting, in April 1984 Gorbachev came to power, and the Union collapsed....

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Gorbachev came to power in April 1985. But it was indeed the beginning of the end.

M.K. Kholodnyi: And other materials came through Viktor Nekrasov from Sakharov. I saw Sakharov and Bukovsky at Viktor Nekrasov's place, I spoke with them.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Sakharov came to Kyiv?

M.K. Kholodnyi: Yes, he did. I saw him once at Nekrasov's. And once I saw him near the courthouse, during Ivan Svitlychnyi's trial.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Sakharov came to Ivan Svitlychnyi's trial?

M.K. Kholodnyi: He did, yes. He and Viktor Nekrasov were standing...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And they didn't let him into the building?

M.K. Kholodnyi: I don't know what happened there. I think they probably didn't let him in.

Ah, I never finished saying. When Klymchuk and I were in the cell, suddenly in the middle of the night the guards came in and ordered us both to undress. I think both of us, well, me—for sure. And they did a shakedown. And in the nightstand under the lid, they found my note. And I thought my mother would receive my things and the guys would have the sense to rummage through them, to see if I had passed anything on. I thought they would find it in the shoes, they were ripped open, and the notes weren't there. Then those notes were photographed and appeared in my case file. This was also added as an episode of my crime. And I was charged under Article 62, “prime”—“anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation.”

As for the investigation of this “activity” of mine... Eight volumes were written! Essentially, Berestovskyi wrote them himself. Not even Balzac had such industriousness—he wrote eight volumes in less than four months! A whole brigade must have worked on it. Balzac didn't write like that!

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Well, there were also materials, articles, the distribution of which you were charged with.

M.K. Kholodnyi: By the way, what I found there. There are interrogation protocols of Mykhailo Nayenko (now the dean of the philology department at Kyiv University), Liudmyla Kaidash, Anatoliy Hryhorenko, Arsen Ishchuk. Berestovskyi interrogated that one, by the way, from two o'clock until about six. Apparently, Arsen Ishchuk wanted a drink and thought the guy would give him something, so he broke down and blamed me for everything. And Berestovskyi thinks he can keep talking—and he held him for a long time. That guy said such things about me that I got goosebumps when I read it. After the war, Ishchuk specialized in criticizing Mykola Yevshan's *Aesthetics*.

So many people were involved in the study of my literary and political activity—and my literary activity was essentially politicized... About twelve oblast KGB directorates were involved. Interrogations were also conducted by investigators from the Leningrad Military District, the Belarusian one. Someone was even interrogated abroad, because there was some field post office in the case file. Only now someone from the SBU told me that some of the guys were interrogated abroad. When I came to my village, there was a wedding at Mykola Lytvynenko's, our neighbor. I was invited there, and I read my seditious poems there. And there were young guys there, several went into the army. So Berestovskyi traveled to military units, conducted interrogations, or their local investigators conducted them.

The teachers behaved very positively. The principal of the Romodanivka school, Vereshchaka, where I studied, the teacher Zelenskyi (by the way, he was once accused of collaborating with the Germans during the war) could have, for example, trembled and pandered to the KGB, but he didn't do that. They gave me positive character references—just as it really was. The women in Dobrovelychkivka gave me positive references—I worked there in a subsidiary farm at the school, as a swineherd. The girls in Odesa also behaved very well. By the way, not a single woman betrayed me. True, Liudmyla Kaidash babbled a lot of nonsense—well, she seems to have been a member of the party committee in our faculty back then, so she had to speak against me... So where did we stop?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: I was asking about samvydav.

M.K. Kholodnyi: Ah, about samvydav. From Ivan Svitlychnyi, I received the book *Contemporary Literature in the UkrSSR* by Ivan Koshelivets. I took that book to Donetsk, gave it to Volodymyr Mishchenko. They took it from Mishchenko back in 1965, after my arrival. And he didn't admit to me until 1972 that they had taken my books from him. They also took my book by Okhrymovych from him. I had given him those books to read. They took the book *The Development of Socio-Political Thought in Ukraine*. It was a book from the twenties. And in 1972, all this came to light. But Mishchenko behaved quite decently. Back then, in 1965, he said that I had brought him a speech by either Yosyp Slipyj or the Pope in defense of national rights in Ukraine. I thought, how can I save the situation? We had a confrontation in the KGB's pre-trial prison. Berestovskyi was conducting it. So I tell him: “Listen, don't you remember? The day I arrived, you found that thing in your mailbox. You just thought I had thrown it in for you. You should have said that you thought it was me who threw it in, that it just coincided with my arrival.” He says: “That's right, I found it in the mailbox.”

V.V. Ovsiyenko: You prompted him like that, right at the confrontation?

M.K. Kholodnyi: Berestovskyi pounced on him: “You remembered better back then than you do now! Your memory was fresher then!” And I say: “No, it's not what he said once that matters, but what he's saying now. What he says last.”

Dziuba gave me Solzhenitsyn's *Cancer Ward* to read. Borys Mozolevskyi was also reading it at the time. He was a friend of mine, I even lived with him for a while in a dormitory, he was still working as a stoker. Somewhere near Dziuba's, on Donetska Street in Chokolivka.

And I also signed those petitions. There was a petition in 1965 or maybe early 1966 in defense of Ivan Svitlychnyi. There were many signatures—seventy or so.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: I think it was seventy-eight. It's a well-known document.

M.K. Kholodnyi: I was about to say seventy-eight too. And I signed it.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: There were several such letters back then. Those who signed them were called “signatories.” And besides poems, were any of your articles circulating in samvydav?

M.K. Kholodnyi: That long letter to Shelest was circulating.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: The reference doesn't have the date you were released in 1972. It would be good to record that date.

M.K. Kholodnyi: It was in the summer. But I don't know the day. It somehow happened that the order to release me came today, but I had nowhere to go because for some reason they were releasing me in the evening.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Well, if you don't remember, so be it. So, after that release, where did they send you—to the Vinnytsia region?

M.K. Kholodnyi: Yes. This is how it was. They took me in a “bobyck” [police van] to the village of Mykulychi to gather my things. And the same car, that “bobyck,” took me back. It drove me around... I don't know why he took me to the Irpin forest. I thought they were going to whack me there. He kept looking around.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: They sometimes did that—to scare you.

M.K. Kholodnyi: I didn't know what it was for. They were stalling, dragging their feet, and didn't tell me anything, then they brought me to the train station—and Berestovskyi hands me a ticket for...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: So it was Berestovskyi who was driving you around?

M.K. Kholodnyi: Yes, yes. With a driver. In a “bobyck.” They brought me from Mykulychi to the railway station in Kyiv and Berestovskyi handed me that ticket. The ticket was made of cardboard, for the “Kyiv – Chernivtsi” train, to Vinnytsia.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And did he tell you where to go?

M.K. Kholodnyi: And he told me to go to Vinnytsia and check into the “Zhovtnevyi” [October] Hotel. And then I was to go to the City Council, to the city department of public education about a job, to submit an application.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: What grounds did they have to send you specifically to the Vinnytsia region? Did you have relatives living there?

M.K. Kholodnyi: The head of the KGB, Fedorchuk, summoned me: “So where do you want to go: to the East or to the West?” I immediately understood what “to the East” meant—to Siberia, right? I say: “To the West.” He says: “Not so fast. You won't be going to the West. You'll be going not to the West, but in that direction. You'll go to the Vinnytsia region—you took a wife from there, after all. We'll find her, maybe you'll get back together with her,”—because I had divorced my wife. We had nowhere to live, so she lived in Kyiv, and I lived there, in the Borodianka region. So our family fell apart because of that.

As soon as I got out of the car at the station in Kyiv, Serhiy Paradzhanov comes along. He was on his way to Kamianets-Podilskyi, some woman was shooting a film there, he was interested in the shoot. There, where the metro is, there was a grocery store, with an underpass. A lot of people were standing there. He bought a wicker basket on the street and says: “Do you see where this man is from?”—And I was untanned. Everyone was tanned, but I had been sitting in a cell where almost no light came in. He bought everything there—dry wine... I wasn't traveling in my own compartment, maybe not even in my own car, because I went to Paradzhanov's. For some reason I was standing in the car, and some guy came up to me and started a conversation. It means someone was escorting me.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Of course, absolutely. They watched you relentlessly, probably right up until independence.

I want to ask, what was your relationship with Vasyl Stus? He said that you stayed with him for some time at 62 Lvivska Street.

M.K. Kholodnyi: As for Vasyl Stus, yes, I stayed with him... I did spend the night at his place. He received my poems from me. But during the investigation, I said that I hadn't given him those poems. And he also said that he didn't know how they ended up there. At the trial, I said that...

There was a discussion of my poems at the Writers' Union together with Stus. They also threw in Natalka Kashchuk. And Mykola Klochko also spent the night—another homeless man, he had been imprisoned before. The KGB soul-shepherds never gave him any peace. Once Vasyl went somewhere, so we lived in his house for a bit. Oleksandr Teslenko from Donbas also lived there. Mariya Ovdiyenko was there once, I recall. I remember once Nadiya Kyrian was there...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Yes, I know Nadiya Kyrian and Mariya Ovdiyenko too.

M.K. Kholodnyi: And then, I remember that Stus might have been in the cell right next to me. I was in number six...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Ah, Vasyl spoke loudly, he could be heard from far away.

M.K. Kholodnyi: He was arguing with the old man who walked on the catwalks, or whatever you call them. Above the so-called walking yards. It was in the winter. So he was arguing about something with that old man. That's how I found out that Stus was there. I started talking loudly so that Stus would hear my voice, so he would understand that I was sitting here too. So he began to quote one of my poems. It was immediately clear that Stus was there. The walls of those yards were often plastered with new cement—because, you see, someone would scratch their initials. Yevhen Sverstyuk—he wrote on the ice in large letters, so you couldn't figure it out right away—he wrote: “Ye.S.” So one could understand that Yevhen Sverstyuk had been there.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Good. You said you were born in July 1939. What was the date?

M.K. Kholodnyi: July 30. Although according to the metric records (and that's how it actually was) I was born on July 31, and not in the village of Karylske, but in the village of Krasnopillia. That's in the Korop district of the Chernihiv region. It's the neighboring village, to which our khutir of Yahidnyi belonged.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And I also noticed: you seem not to have mentioned your mother's first and last name.

M.K. Kholodnyi: My mother's name was Halyna Mykhailivna, her maiden name was Chucha. My mother died right on the street, I don't know why, in 1984, around February 16. She had some kind of blood clot on the back of her head. It seems there was some kind of blow to the head, if she fell backward. By the way, she never regained consciousness, but lay in the hospital for several days until about the 19th. She was in the hospital for about three days and died without regaining consciousness. And the man who brought her home on a sled (he brought her while she was still alive), Vasyl Yakymenko, who was married to a woman on Hukova Street—I forget her name—he lived two houses away from my mother—he said that my mother was lying with her head in the direction of her house. Well, maybe she turned around, who knows what could have happened...

And my father perished. He remained in Siberia. He wanted to bring my mother there, but my mother didn't go—her mother, that is, my grandmother, dissuaded her. She dissuaded her, saying: “Don't go there—it's far away. And besides, you know, he might leave you there.” Well, you see, the war caused such things back then. My father didn't want to return to the kolkhoz, he wanted to send us an invitation. My mother didn't go. I, of course, would have been long Russified there and would not have existed as a poet. And my father died somewhere around 1962 or so. Supposedly he fell under a train. Whether he fell, or maybe they, I don't know... I don't think it should be connected with me. In short, he died, fell under a train.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: You didn't have any brothers or sisters?

M.K. Kholodnyi: I had a sister for four years. I had a brother. He died during the war, as a little boy. And I had a sister, she died too. My father came home on leave after the war, around 1947. A sister was born after that visit. He maintained a normal relationship with my mother. My cousin was bathing her in the well, and she caught a lung disease. There was no penicillin back then, and she burned out in a week.

What else did I want to add. I gave a significant part of my archive to the State Archive-Museum in Kyiv, located on the territory of St. Sophia's Cathedral. And part of my archive—up to 1984, in particular, photographs, documents—I gave for safekeeping to Vasyl Yaremenko, a professor at Kyiv University. And he appropriated it. Seriously! Why did I give him materials up to 1984? Because my mother died then and clouds began to gather over me again. I was constantly blackmailed at school. By the way, I was fired from my job for corresponding with Sakharov. They thought I was corresponding with Academician Sakharov, but I was corresponding with the Sakharov who, you may remember, rescued or found the crew of Grizodubova, Raskova, and Maryna Osypenko somewhere in the Far East. That pilot, Mykhailo Yevhenovych Sakharov, was captured during the war with a teacher, also a pilot. I met him through Makarenko, a teacher from Yavmynka (?). I taught there with Makarenko. So he told me that he was captured with that pilot. Well, Sakharov no longer flew military aircraft, only civil aviation, on firefighting planes. Well, Grizodubova helped save him a bit, otherwise he would have been in Siberia.

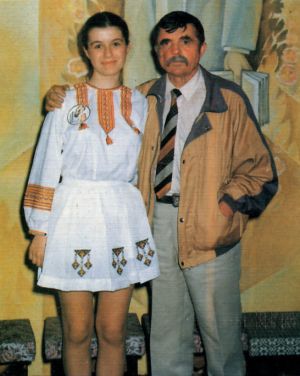

So in 1984 I appealed to Reagan, and sent a copy to Chernenko, with a request that he grant me political asylum. After that, clouds began to gather around me. The oblast KGB issued me a warning. I thought my place might be searched and my archival materials confiscated. Therefore, I gave Vasyl Yaremenko many photographs: there's Paradzhanov, and Dziuba, and Pavlychko, and Kalynets, my father and mother, me with my mother and father.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: That's a valuable archive. Have you asked Yaremenko to return it?

M.K. Kholodnyi: There was an agreement with him that he would send them somewhere abroad, to preserve them that way. I said: “If you don't do it in two years, then return them to me, I'll do it myself.” I thought, if they don't imprison me, then in two years this will all blow over, the clouds will dissipate—I'll do it myself. But he didn't do it. And then he tells me: “My son will research them. I won't return those materials to you.” There are a great many items for storage there: letters from Dziuba, from my mother. There are autographs of Serhiy Paradzhanov, of people who have already passed away. There are documents about my persecution. For example, a letter from Petrenko from “Radianskyi Pysmennyk” says: “We cannot accept your book for consideration because you hold anti-Soviet positions.” They didn't accept it for consideration, but he knows what positions I hold. So Yaremenko supposedly told the director, Kriachko, that he would hand over Kholodnyi's archive. I've already spoken about this in the press, about who appropriated my archive. On the sixth or seventh, I gave an interview to the newspaper *Den*. But he had told Kriachko this even earlier. There are documents there that were given to me from the KGB archive, with KGB stamps.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Maybe all of it will be preserved?

M.K. Kholodnyi: I think it should be preserved.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Well, okay, Mr. Kholodnyi, I think we've covered what we needed to. Thank you.

M.K. Kholodnyi: Thank you, I wish you creative success.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: This was on October 6, 1999, on Volodymyr Hill. Mykola Kholodnyi was speaking. The recording was made by Vasyl Ovsiyenko. (The recording continues on the move).

M.K. Kholodnyi: Who supported me morally and financially when I was expelled from the university, when I was being persecuted in Kyiv? Because I was still living in Kyiv, writing poetry. I didn't lay down my arms. Who supported me financially?