Interview with Viktor Ivanovych KUKSA

(Last reading on February 11, 2008).

V.V. Ovsienko: Today is April 10, 2002, and Viktor Ivanovych Kuksa is speaking. What is the address here?

V.I. Kuksa: 8 Zholudyeva Street, apartment 37.

V.V. Ovsienko: Please give the postal code as well.

V.I. Kuksa: I think it’s Kyiv-134 now.

V.V. Ovsienko: 03134. And do you have a telephone?

V.I. Kuksa: My home phone number is 472-48-10.

V.V. Ovsienko: Vasyl Ovsienko recording.

V.I. Kuksa: I was born in the Kyiv region, Bohuslav district, in the village of Savarka. It’s a picturesque village on the Ros River.

V.V. Ovsienko: Please state your date of birth.

V.I. Kuksa: I was born in 1940, on February 13. Our village is quite interesting, and the school I attended is quite interesting. Not so much the school itself, but the teachers who taught me. Our school always raised patriots. The vast majority of the teachers were patriots of their profession and patriots of their homeland. We had a music teacher who served 25 years in prison and then returned to the school.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what was that teacher’s name?

V.I. Kuksa: That was Dmytro Yevdokymovych Chaly. He was in Kolyma, probably went through all the Soviet transit prisons. He survived, came back from the camps, fell ill, and died. He was already old. For the most part, they were men who were naturally intelligent, who still remembered the Ukrainian People's Republic. Even my mother remembered it—she was orphaned at the age of three and was taken in by wealthier people, and she grew up with them. This man—her stepfather, so to speak—also served more than twenty years in the camps.

V.V. Ovsienko: It would be good if you could name these people, if you remember.

V.I. Kuksa: Ronsky, Oleksandr Ronsky, he also served time. I remember when he returned from the camps. I was old enough to remember. It must have been the first post-Stalin amnesty.

V.V. Ovsienko: Around 1954.

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, he returned around that time. He later worked at the sugar factory, preparing those straw mats they use to cover piles of beets. He often visited us and told my father a few things. My father was a naturally intelligent man and also told me many things.

Another interesting thing: across the Ros River from us, there’s a village called Sich. In that village, the surname Kobets was common. From the 1920s to the 1930s, all the Kobetses were shot. If your surname was Kobets, the NKVD would get you one way or another and destroy you. They destroyed people just for having that surname. The explanation is very simple. During the time when Soviet power was being established, it didn't take hold in our village for a long time because the people were against it. The Ukrainian people fought against Bolshevism even before the 1920s. In the 1920s, that resistance was crushed. I was born in this village, among these people I knew, and I heard many things. From a very early age, I knew the anthem “Shche ne vmerla Ukraina” (Ukraine Has Not Yet Perished). Well, maybe I didn't know all the words, but I knew most of them. I had a decent voice, I could even sing it. Of course, I tried not to sing it in public. Only among friends. I tried not to tell anyone about it. And when I was about 25, I was living in a dormitory. There were all sorts of people there. With the Khrushchev Thaw, this kind of ferment began among the people. As someone who was already a bit knowledgeable, nationally conscious, as they say, I listened to all of it. I read—well, not a lot, but I did read.

V.V. Ovsienko: Let's pause here. I would like you to recall your parents, by name, and from what year to what year they lived.

Maria Polishchuk, wife: Tell him about the mathematician Kravchuk, who taught at the school…

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, the famous mathematician Mykhailo Kravchuk once worked at our school.

V.V. Ovsienko: Ah, the academic who was repressed and died in Magadan? (Born 27.09.1892 in Volyn. He worked in Savarka from 1919–21, was elected an academician of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences in 1929, arrested on 21.02.1938, and died on 9.01.1942. – V.O.).

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, he was my school’s principal. I didn’t know him, because he lived there a bit earlier, but the spirit of that Kravchuk—it remained for a long time. Arkhyp Lyulka, the aircraft designer, also came from this school. (24.03.1908 – 1.06.1984. Designer of the first dual-circuit turbojet aircraft engine. – V.O.). He was my neighbor; he and my father herded cows together as children.

V.V. Ovsienko: You mentioned your father—what was his name?

V.I. Kuksa: My father was a naturally intelligent man. But his life turned out in such a way that he was very poor in those times, especially in the thirties, when he was already married. But since he was naturally intelligent, they made him the head of the village council. Because there was no one else to take the position. But he knew his own worth, he knew who he was dealing with. Even when the Germans came, he was the head of the village. The Soviet authorities didn’t take him to the front; he was left behind for underground work. But his underground work ended when he started hiding young girls from being deported to Germany. So the order would come: “Give us the girls,” and he would, of course, gather the girls, but—we have a large ravine near the river—he would hide the girls in the bushes there, and so he handed over almost no one to Germany. What else did they do? They burned granaries with grain so the Germans couldn't take it away... And then one of the communists turned him in, the Gestapo took him, and he ended up in the Bohuslav prison. He was terribly tortured in that prison. But the very same person who turned him in—he was the one who let him out, because the Germans gave a final word before execution. They call you out: dig a grave for yourself. You dig it. Then, a day later, at six in the morning, they would shoot you into the same grave you dug. But before that, they give you a last word—you can say whatever you want. And that guy was afraid that my father might not hold up and say that he was a communist. But my father was never a communist. So at night, he says to my father: “Ivan,” he says, “go chop some wood for the commandant's office.” They took him out of the cell. He said there wasn't much of a guard, so he went over the fence—and into Bohuslav. There are ravines there, and he escaped from there. Once he escaped, he went into hiding. And then, in 1943, he was drafted to the front. He fought until 1945, reached Berlin, and came home after the war.

V.V. Ovsienko: So, is your father still alive or has he passed away?

V.I. Kuksa: No, my father passed away. I was released from the camp, but I didn't make it in time: I arrived when my father was lying unburied. It was freezing, I arrived, and my father was lying at the cemetery—they hadn't buried him, they were waiting for me. That was in 1969. That's how I found my father. He was born in 1907. Ivan Vasylyovych Kuksa. And my mother—Oksana Anatoliivna, maiden name Zemenko. She was born in 1911 and died in 1987. My mother was from the neighboring village of Olshanytsia. Her parents died, and she was left an orphan at the age of three. A wealthier family with the surname Lonsky took her in—a Ukrainian family. There were two brothers: one was Oleksandr Ronsky, the one who took my mother in. His own brother, Krysan, was a colonel, I think, I don't remember, but he held a rather high rank in Symon Petliura's army. He was shot when the army fell apart and Petliura went abroad. They were rounded up then and shot somewhere here in Kyiv. Where the officers' cemetery is. Those Soviet officers—they lie on the bones of the Ukrainian People's Republic army. An old acquaintance of mine took me there and showed me the place where the officers of the Ukrainian Central Rada were shot. Where that Jewish Menorah is, if you walk further down that ravine. People walk their dogs there now. Right on that spot, they shot the officers of the Ukrainian People's Republic. And they buried them in that officers' cemetery. When that old man and I went there, there were still unburied bones. That was somewhere around 1972–74, I think. Now, it's probably all covered over with generals.

So, my mother's stepfather's brother is also buried somewhere there. And then what? When the Bolsheviks came, this Oleksandr Ronsky was arrested in the 1920s–30s, like everyone else, and sent to the camps. He spent a long time in the camps and came home after the amnesty, worked at the sugar factory, preparing mats for the beets, to cover the beets. So I still saw him, met him more than once. He died earlier, and his wife lived on after him for maybe ten years or more.

My mother lived and worked on the collective farm her whole life. That's what I can tell you about my mother.

V.V. Ovsienko: And when did you finish school?

V.I. Kuksa: I finished school in 1957. And when I ended up in the dormitory, that's when this ferment started among the people. And why was there ferment—that Khrushchev Thaw contributed to a national upsurge. At that time, I didn't yet go to that club, which was then called, I think, “Zhaivoronok” (The Lark). I later got to know the people who went to that choir. Alla Horska went there, and Lyudmyla Semykina, I think—I don't know for sure—the late Vasyl Symonenko. If you find a photograph, you can see. Later, I joined the “Homin” (The Echo) choir. But the first choir was “Zhaivoronok.” That was the first choir that started singing carols in Kyiv. It was directed by Leopold Yashchenko.

V.V. Ovsienko: I think Yashchenko directed the “Homin” choir?

V.I. Kuksa: “Homin,” “Homin.”

V.V. Ovsienko: And what year did you start going there?

V.I. Kuksa: I started going there in 1969. That choir used to gather on the banks of the Dnipro, where the dacha of the former defense ministers was. It's near the Pechersk Lavra. The late Ivan Makarovych Honchar used to come there, all the people who were nationally conscious. People got acquainted there, the circle grew. When this choir was banned, it split in two. One part went indoors, because at the time they were told they had no right to be on the street, they had to go indoors.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what premises?

V.I. Kuksa: Some of the people went to a school building, I don't remember its number, but Ihor Holobutsky knows this very well—he still goes to this choir. The people there have changed, but some of the old-timers have remained—they're now in their sixties, but they still go to the choir. Here's a photograph for you.

V.V. Ovsienko: So is Vasyl Symonenko here?

Maria Polishchuk: And this is Vasyl Lytvyn’s wife, this is Alla Horska.

V.I. Kuksa: And here is Vasyl Symonenko, and this is... Oh, I've already forgotten. But isn't it an interesting photograph?

V.V. Ovsienko: Oh, yes, yes!

V.I. Kuksa: In the dormitory, there were many people who started to get interested in this, but they didn't know who to go to or where. Since I already knew Georgiy Moskalenko, we decided to do something.

V.V. Ovsienko: So you lived in the dormitory—were you working somewhere?

V.I. Kuksa: I worked in construction.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what—right into construction after school? Were you in the army?

V.I. Kuksa: I was, from 1959 to 1961.

One thing led to another, and it came to the point that something had to be done. Around us were patriotically-minded people who were not against maintaining contact with us and doing something, but we decided to do something just the two of us for the time being. We decided to hang the national flag. We had a banknote (it’s somewhere in these photos), and we took the tryzub from there, because it wasn't available anywhere else. We made a flag. True, making the flag was also a big problem.

V.V. Ovsienko: I’m curious, how was it done?

V.I. Kuksa: The Soviet authorities made sure that there was no yellow fabric in Ukraine. In those days, it was useless to even look for yellow fabric anywhere in Ukraine—you wouldn't find it. We went to the stores, and we found blue. But yellow—where could you get it—nowhere. They were selling scarves at a department store on Harmatna Street. They had a sort of brownish tint, although they were yellow. We looked at them—they would do. We bought this fabric and decided to sew a flag. We lived in a room for two. There was a third person, but he was away at the time. We sewed the flag right there in the room.

V.V. Ovsienko: So you and Georgiy sewed it together? By hand?

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, yes. By hand—what’s there to sew? We cut a tryzub out of black sateen, the kind used for linings. We deliberately made it black—we knew what color it should be, but we cut the tryzub from black sateen and sewed it onto the flag as an appliqué. I knew the words to the national anthem, but we didn't write them for the people on the street, because the words wouldn't be visible from there, but for those who would later take it down. We wrote the words “Ukraine has not yet perished” and deliberately added “it has not yet been killed.” And we put three dots. This was written on the flag. Well, we started to figure out where we could hang it.

V.V. Ovsienko: And this text—was it embroidered with thread or was it written?

V.I. Kuksa: No, it was written. We wrote it with ink. The question arose of where to hang the flag. At first, the plan was to hang it at the train station, over the central entrance. We scouted the area. It would have been quite difficult there because security was tight, and it had to be done before May Day. And we thought to ourselves that I wouldn't even have time to climb up there before they’d take me down—a sniper or someone else. So we decided to postpone that—we concluded that we should hang it on the institute. And why on the institute—that's very simple to explain. In Soviet times, the demonstration that went to Khreshchatyk from that part of Sviatoshyn would gather, or they were brought by buses, to the “Bolshevik” factory, which is opposite the Institute of National Economy. There they would form columns, raise their banners, and march to Khreshchatyk. The Polytechnic Institute, the Institute of National Economy, and others. Back then, all students were herded to these demonstrations. Of course, the calculation was that many students would see this flag, and maybe it would, as they say, awaken their national consciousness.

This idea was accepted with joy. We waited until late at night, around two in the morning we got on the last tram and rode from Sviatoshyn to the “Bolshevik” factory. We got off one stop early, checked everything, although we had already been there before. I put socks-mittens over my shoes, tucked the flag under my shirt, but there was a red flag hanging in that spot. I knew I would be cutting down the red flag, which is why I took a kitchen knife. Flag under my shirt, knife in my pocket, I climbed the ladder. It was quite difficult.

V.V. Ovsienko: Is there a fire escape there?

V.I. Kuksa: A fire escape. The roof is covered with sheet metal. From the street, the roof looks flat, but it's not—it's all at an angle. But when it's covered with sheet metal, they make these seams. I grabbed onto these seams and climbed. I took out the knife, hooked the red banner from below, it rolled down the roof and got caught there. And I took out our national flag and hung it in its place. I climbed down from the roof, we looked, we went out onto the road—it was fluttering beautifully, a beautiful sight. At night it's illuminated—they set up lighting before May Day. We left.

V.V. Ovsienko: And did you inspect this place beforehand, go inside? You must have known in advance how to climb up there, right?

V.I. Kuksa: Moskalenko was a student at that institute; he had a look around and said that there was a fire escape, that you could get to it and climb it. And he had a homemade pistol made especially for this purpose. What was it for? In case someone was coming or a policeman saw us, so we wouldn't have to shout, but just give a signal. And the homemade pistol was loaded with sulfur from matches. In childhood, everyone made such pistols. Georgiy was supposed to give me a signal to run—it was specifically for a signal. We had one bottle of gasoline. We poured it all around the ladder after I had climbed down, in case they searched with dogs, so the dog couldn't immediately pick up the scent. I had some leftover bandage—I tied the flag with a bandage. We went to Komsomolsky Park, there's a neglected lake there, and we threw the rest of what we had into the lake. And that was the end of it.

They found us by the handwriting. Moskalenko had written on the flag. They went through all the students, and they identified him by his handwriting; it was established by a graphological examination.

V.V. Ovsienko: But wait, you mentioned that you went to the park the next day—which park was that?

V.I. Kuksa: Ah, yes, yes. That was Pushkin Park. There were a lot of people near the institute. We didn't go near. The flag hung there, they took it down around ten in the morning, or so, because they were even afraid to climb up there: they thought it was mined. It caused quite a commotion—nothing like it had ever happened before. They took it down and immediately called Moscow. Back then, everything went through Moscow. And the instruction from Moscow was: “Find and punish them at any cost!” But thanks to the fact that here in Ukraine, we still had Petro Yukhymovych Shelest, God rest his soul, they gave us the minimum.

V.V. Ovsienko: But wait—they couldn't find you for quite a long time, right? Were there any signs that they were looking for you? You showed me some documents earlier.

V.I. Kuksa: There were, there were. The documents—that was later. That was after I returned from prison, when they were evicting me as an unreliable person. But back then, they got on our trail fairly quickly, but they didn't arrest us. They watched us, sent all sorts of provocateurs, agents, who would strike up all kinds of conversations with us. They wanted to know who we were dealing with—maybe we were dealing with some organization or someone else. That was their goal. I think that's why they didn't arrest us for so long.

V.V. Ovsienko: Or maybe they weren't sure?

V.I. Kuksa: Or maybe they weren't sure. We can only find that out from the archives. If we are ever rehabilitated and the documents are opened, then it will become clear why. Although, probably, even that isn't there. They say they had double-entry bookkeeping—if someone wrote a denunciation, it doesn't mean that denunciation is in the file now. It could have been burned or transferred somewhere. Well, all this will become clear when the archives are opened and everything can be read.

V.V. Ovsienko: And were there any summons to the police or any suspicious conversations?

V.I. Kuksa: There were many. I wrote about this. They summon you to the military enlistment office: write in block letters, fill out the form, be sure to use block letters. They were double-checking, because it was written in block letters on the flag. And after the camps, they constantly summoned me: if something happened somewhere in Kyiv—they'd summon me to the enlistment office: write a pledge that you won't leave the dormitory. And when the Prime Minister of Canada, Trudeau, came, they stationed the commandant at my door. Well, he didn't stand there all the time, but he was always watching to make sure I didn't leave my room. And when US President Nixon came, they had to send me all the way to Sokolivka. I don't know what they were afraid of—probably that I would communicate with someone somewhere.

They got on our trail in about a month or more. They sent in provocateurs who would engage us in all sorts of conversations. We felt that we were, as they say, “on the hook,” but we kept working and paid no attention to it. We were, so to speak, waiting for what was bound to happen.

Sometime in December, two or three weeks before the New Year, they summoned me to the HR department in the morning before work. I went to the HR department, and two guys there took me by the arms and said: “Come with us.”

V.V. Ovsienko: So what date was that?

V.I. Kuksa: It was about, I think, two or three weeks before the New Year of 1967. “Come with us!” Well, I went out onto the street with them—a “Volga” was standing there, they opened the door, put me in the “Volga”—and drove me away.

V.V. Ovsienko: We need to establish the exact date. It's recorded here: February 21, 1967.

Maria Polishchuk: So that was after the New Year.

V.I. Kuksa: No, before the New Year.

V.V. Ovsienko: But here's the document: you were arrested on February 21, 1967. And where did they take you?

V.I. Kuksa: To the KGB prison on Volodymyrska Street. They kept us in solitary confinement cells. They also planted an informer in my cell. He was about fifty, maybe. He kept asking me why I was here and what for. And he told me that he was a teacher, and his student had written some poem. He tried to show that he was such a Ukrainian patriot. But I already had an idea of what kind of patriot he was, and I didn't fall for it: I knew he was an informer. Because I had seen them before. Literally a month before my arrest, I had already seen informers—I could feel it in my soul, as they say, that someone was breathing down my neck. The investigation lasted until about May.

V.V. Ovsienko: Who led the investigation, do you remember?

V.I. Kuksa: It was investigator Loginov, and there was another one—Chunikhin. What can I say about these people? To be honest, this Chunikhin was the kind of man who honestly did his duty. It wasn't like he was out to get me or anything.

V.V. Ovsienko: I'm curious, what language did they conduct the investigation in?

V.I. Kuksa: Russian. Chunikhin told me: “What are you—you’re a fly, and here’s an elephant. The elephant will just go—*thwack*—and crush you. See? You’re gone.”

There were other people in the prison. One particularly interesting person was the one who shaved us, the barber. The Arab-Israeli war was happening right then. And we weren't given newspapers, or magazines either. So when they brought me to be shaved, he would shave me, but he would lay out the newspapers and hold them there for a long time while I skimmed the news. A very good man. I don't know if he's still alive today.

And there was another incident, which could only have been done by one of the KGB agents. One evening—it must have been ten o'clock at night—the “kormushka” (feeding hatch) opens, and someone says: “Come here.” Well, I can't see who it is, because it's low. I approach. “Give me your bowl.” I hold out my bowl. He puts two onions, a piece of butter, two big, beautiful apples, a slice of sausage, and, I think, a lemon into the bowl. But when you get a package, a list is always made: who, what, and from whom. But this was just placed on the plate, the “kormushka” slammed shut—and that was it. To this day, I don't know who did it. So there were people there, too, who were sympathetic to us. I don't know if it was just for me, or if they brought things like that to others as well. I'm telling you honestly, they brought me this, and no one ever reminded me that someone had brought me something—nothing like that happened.

V.V. Ovsienko: And as for the investigation—how was it conducted? Did they already have a prepared charge against you?

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, they found everything through the handwriting.

V.V. Ovsienko: Did you deny it much or not?

V.I. Kuksa: There was no point in denying it further: the expert analysis had established the handwriting.

V.V. Ovsienko: But you weren't the one who wrote it?

V.I. Kuksa: No, Moskalenko wrote it. They figured out from the handwriting that he was the one who wrote it. Further denials were pointless.

V.V. Ovsienko: Did they show you the flag during the investigation for examination?

V.I. Kuksa: They only showed us a photograph of it. There was an envelope on which was written “store forever.”

V.V. Ovsienko: “Store forever”? Oh, that's interesting! So this flag might be stored somewhere in their possession?

V.I. Kuksa: Of course, it's stored. Everything is stored.

V.V. Ovsienko: It would be interesting to retrieve it from there. Was the photograph in color?

V.I. Kuksa: I don't remember.

V.V. Ovsienko: They probably didn't have color photography back then. It's written somewhere that it was supposedly a color photograph, but who knows if that could have been possible then.

V.I. Kuksa: I don't remember. It was thirty years ago, after all, I don't remember.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what court tried you—a closed one?

V.I. Kuksa: The Kyiv Regional Court, a closed trial.

V.V. Ovsienko: In the building on Bohdan Khmelnytsky Square?

V.I. Kuksa: Yes. They tried us there. The trial lasted two days.

V.V. Ovsienko: And there were no witnesses?

V.I. Kuksa: The only people in the courtroom were the witnesses who saw the flag. They were either the dormitory commandant, or some retired military men who saw the flag in the morning, got scared, and called the police, and then the KGB. They said they were afraid to go up there because it could have been Banderites, so maybe it was mined. Well, I don't know who took it down or how, but it's interesting that there was such a negative attitude towards us. There was one retired military man—he called us “scum,” said: “We fought in the war, and they, the filth…” And they called us every name in the book. I don't know them, I've never seen them in my life.

V.V. Ovsienko: You know, in 1973 in Chortkiv, some guys led by Volodymyr Marmus also hung four flags on Independence Day, that is, on January 22, and they had an old man as a witness, a watchman, who testified like this: “What did I see? In the evening, your banners were hanging, and in the morning, I look—our banners are hanging.” Flags, that is.

V.I. Kuksa: And these retired military men condemned us in court more than the prosecutor did. There were two of them. I had never seen them in my life.

V.V. Ovsienko: And how much did the prosecutor ask for?

V.I. Kuksa: The prosecutor asked for three years for both of us.

V.V. Ovsienko: That's Article 62, Part 1, but what about Article 222?

V.I. Kuksa: They did it cleverly, look. According to Soviet law, “manufacturing and carrying a cold weapon” was, I think, two years. There is such an article. And for a “firearm,” it's three. Since I had that knife, I got two years. And Georgiy had a homemade pistol, which is considered a “firearm.” This, in my opinion, played the main role in Georgiy getting one more year.

V.V. Ovsienko: And he was the one who made that homemade pistol?

V.I. Kuksa: I don't know who made it.

V.V. Ovsienko: But it wasn't you?

V.I. Kuksa: No, not me.

V.V. Ovsienko: So, he probably made it, and that's why he got more.

V.I. Kuksa: I don't know who made it. Because I didn't make that knife either. It was a kitchen knife. Since I was carrying it (and there is such an article), they had to give me a charge for “carrying a cold weapon.” But they didn't take into account that the knife was related to the main charge, because I cut the flag with that knife. I said: “Why are you pinning a criminal charge on me?” “Eh,” he says, “you should have chewed the Soviet banner with your teeth!”

V.V. Ovsienko: So, you were sentenced on May 31, 1967, to two years, and Moskalenko was given three years. Then they took you...

V.I. Kuksa: Then they took us to Kholodna Hora in Kharkiv. There, they locked us in a death row cell.

V.V. Ovsienko: Familiar places. And what impression did it make on you? On me, for example—nothing special: I didn't even know it was a death row cell. I thought all cells were supposed to be like that.

V.I. Kuksa: When we looked at those iron bunks, how they slam those bolts, the dogs... Those on death row are separated... We didn't stay in those death row cells for long; they threw us into another cell, and there we met Mykhailo Osadchy. When he was brought into the cell, we exchanged a few words, he looked at us and asked: “Boys, where are they taking us?” We said we didn't know, but they say to some place in Mordovia. “And I,” he says, “am coming from Mordovia. We won't be here for long, because they'll take me from here soon.” And indeed, he was with us for about 2-3 hours, then they came, took him from the cell, and transported him to Kyiv.

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes, since he was arrested at the end of August 1965, his two years were just about up. He had a two-year prison sentence.

V.V. Ovsienko: Well, that's where we met him, at Kholodna Hora. And then they shaved our heads. It’s interesting how they transported us. They take us in a “paddy wagon” to the train. They're transporting only common criminals. But according to instructions, we need a separate convoy. They're leading us across the road—they station guards with German Shepherds and lead us across. People ask: “Who are they leading like that?” “They're English spies.”

V.V. Ovsienko: “Especially dangerous ones.”

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, yes, yes. We traveled separately in the train car all the way to, I think, Ruzayevka. In Ruzayevka, we met a group of Marxists from Leningrad. There were two of them—one was Smolkin, and the other was Hayenko—a surname like that...

V.V. Ovsienko: Ah, I know Smolkin.

V.I. Kuksa: So I met them at that transit point in Ruzayevka. And then came Potma and Yavas.

V.V. Ovsienko: Yavas—what was the camp number?

V.I. Kuksa: Camp number eleven in Yavas.

V.V. Ovsienko: What impression did the camp make on you?

V.I. Kuksa: When we got to the camp, I was surprised. The guys came, many people came to the gate. And when we crossed into the camp, there was no convoy, the guys surrounded us: where are you from? what happened? We started to tell our story. The guys gave us a very warm welcome.

V.V. Ovsienko: And were they mostly Ukrainians?

V.I. Kuksa: All Ukrainians!

V.V. Ovsienko: One gets the impression that everyone there was Ukrainian.

V.I. Kuksa: Mostly Ukrainians. We looked around—this is Ukraine here!

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes, they moved Ukraine to Mordovia.

V.I. Kuksa: They gave us a few days off. They put me in one brigade and Georgiy in another. I ended up in a construction brigade. It was time to go to work in the industrial zone—it was a furniture factory. A guy comes up to me, asks: “Where are you from?” I say, from Kyiv. “And where were you born?” “Bohuslav district.” “And which village?” “Savarka.” “Do you remember Vasyl Linsky? From Mysailivka, the neighboring village?” “No, I don't remember.” “Well, you might not remember him, but you remember the trial. I am Vasyl Linsky.” And he was in charge of this construction brigade. He was the foreman. He took me into his brigade. Since he was from the neighboring village, you could say he helped me a bit in the camp. Well, what was there—a shovel, a crowbar. And in his brigade, there was an excavator operator, an excavator driver. The guy himself was from the Poltava region, had served 25 years, and was about to be released. Someone had to work on that machine—and there was no specialist. He asks who can do it. And I went and said—once, when I was 18, I completed a course for machine operators. I say: “I can.” And he tells me to say that I can do it. I told him I have the document, but I've never actually done it. He says: “You'll learn. Fedya is being released in a day, he'll teach you in one day.”

I go up to this Fedya in the industrial zone. He asks: “Are you going to do the work?” “Yes.” “Get in, I'll show you.” And this excavator was ancient—twenty levers, no hydraulics, all on cables and ropes.

V.V. Ovsienko: Rope-and-pulley technology.

V.I. Kuksa: Yes. He explained and showed me everything. But when a person wants to, you can learn in an hour. I really mastered all that science in literally an hour, the only thing was that for almost a week I could barely walk—my legs ached so much from those levers. But then it all passed, and I was like a circus performer on it. Sometimes, the guys would ask—they were unloading lime, which is back-breaking work, or gravel, or stones—so they would wake me up at night when the train cars arrived, and take me to the industrial zone. And the guys would already be there with crowbars and shovels. I'd start that excavator in the freezing cold… I always helped the guys.

V.V. Ovsienko: They brought wood there and made some kind of furniture?

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, furniture. But not construction materials—they even made concrete and then transported it by truck somewhere outside the camp zones, building roads somewhere. We had a concrete mixing plant that made this concrete. I was always helping the guys with this excavator. Everyone will confirm that. That's how I served my term in that camp.

V.V. Ovsienko: There were our people there, you communicated with them. It would be interesting if you told us what that environment was like, what kind of people you knew there.

V.I. Kuksa: It was 75 percent, maybe even 80 percent—Ukrainians.

V.V. Ovsienko: And how many people were there in total?

V.I. Kuksa: In the camp, there were probably about 800 men, something like that. What I remember most—near one of the barracks stood a watchtower with a guard constantly on duty. It was interesting when their guard changed. When they changed, you could hear everything they said. The new shift arrives: “Comrade Sergeant! Post number 3 for the guarding of state criminals and traitors to the Motherland is handed over!”—and “Post No. 3 for the guarding of the same is accepted.”

V.V. Ovsienko: Would you look at that!

V.I. Kuksa: I was in a camp like that—“state criminals and traitors to the Motherland.” For that flag, I was a “state criminal and traitor to the Motherland.”

V.V. Ovsienko: Something you're still proud of?

V.I. Kuksa: And the people there were truly such that—anyone who hasn't been in that camp doesn't know the real Ukraine. Only those people who have been in the camps can grasp what all of Ukraine is. Because if you go to some region, you won't feel it. But when you're with those people, communicating, you can draw your own conclusions about what the people are like there—what the people in the Poltava region are like, what the people in the Ivano-Frankivsk region are like, what the people in the Kyiv region are like. You see how they differ slightly from one another. But basically, they are Ukrainians, for whom the Ukrainian idea, Ukrainian patriotism—is the main thing.

I met people there who had arrived before me. It was the first wave: Ivan Hel, Sashko Martynenko, Bohdan Horyn, Mykhailo Horyn, the same Mykhailo Osadchy, Mykhailo Ozerny, Panas Zalyvakha, whom I knew very well and still know, I'm on friendly terms with him to this day. (P. Zalyvakha died on April 23, 2007. – V.O.), Bohdan Rebryk. Stepan Virun was there, but when I arrived, Virun had been pardoned.

V.V. Ovsienko: In the Lukianenko case?

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, yes, as soon as I arrived, that pardon notice, as they called it, was hanging there, stating that Virun was pardoned. Martynenko, Oleksandr, I think Ivanovych—he was a unique person. He was a man of high morals, of high culture. He was, I believe, a physicist himself, a geophysicist, one of the best students at his institute. While still a student, he gave lectures to other students; the associate professor would entrust him with it. He studied at Lviv University.

V.V. Ovsienko: He was arrested on August 25, 1965—and how many years did they give him?

V.I. Kuksa: They gave him five years. And he served them. And he himself was taken from Kyiv. After his release, he was not allowed back into Kyiv; he went to the Poltava region, because he was from the same village as Bilash. They, I believe, went to school together with the composer Oleksandr Bilash. When I arrived at the camp, I met Martynenko; he approached me. We were friends until he died.

V.V. Ovsienko: And when did he die?

V.I. Kuksa: When perestroika was already underway, when there was the club that Serhiy Naboka organized.

V.V. Ovsienko: The Ukrainian Culturological Club? That club started around July 1987.

V.I. Kuksa: And he died sometime in 1988. At the Zhovtneva Hospital in Kyiv. He came on vacation, to rest. They gave him no peace in the Poltava region, even though they had already been given an apartment there. They gave him no peace there, so he went to work somewhere on the Yamal Peninsula, I think. There was some radio station there; he worked as a programmer. And either the climate didn't suit him, so he came here, fell ill, and died. He is buried in the Baikove Cemetery. It was a circle of people—Alla Horska, Lina Kostenko, Lyudmyla Semykina, Ivan Svitlychny, Ivan Dziuba. It was one cohort of people, some of whom are still alive today.

V.V. Ovsienko: Do you know where his grave is?

V.I. Kuksa: I do.

V.V. Ovsienko: It would be good to know the location of this grave.

V.I. Kuksa: I know, I know. He was cremated; there's a small urn with his ashes.

V.V. Ovsienko: That's called a columbarium. You mentioned the younger generation, the Sixtiers, but in Mordovia, there were also people of the older generation. Who among those people did you know?

V.I. Kuksa: Most of them were people from the OUN, from the UPA. There was Vasyl Yakubiak, Levko Levkovych... I think his name was Levko. There was also a man with us—he died in the camp—Stepan Mamchur, a priest. Maybe you've heard of him, he was with me.

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes, he died later in the Urals. His remains were recently brought back to his homeland, did you know?

V.I. Kuksa: I didn't know that.

V.V. Ovsienko: About a year, a year and a half ago, maybe.

V.I. Kuksa: He was a priest in Irpin. He himself was from the Ivano-Frankivsk region, I think, but when they got on his trail, he moved here and was a priest here, and he was arrested from here. He was also an interesting person. There was Dmytro Bessarab, who told how they went after the Polish general.

V.V. Ovsienko: Świerczewski.

V.I. Kuksa: Świerczewski... Vasyl Pidhorodetsky. Then Vasyl... What's his surname?... I've forgotten. Well, I'd have to try to remember, I can't right now. These were such outstanding individuals, and if they are alive today, may God grant them health.

V.V. Ovsienko: Some are still around. Pidhorodetsky is still alive; I saw him about two years ago, he lives in Lviv now. (Died 20.08.2004. – V.O.). Did you talk with these people? I'm curious, was there any samizdat circulating there?

V.I. Kuksa: All sorts of literature circulated there, and samizdat circulated in the camp. People brought it during visits, somehow they managed.

V.V. Ovsienko: Mykhailo Horyn's wife brought him “Internationalism or Russification?” there. He started reading it and they took it away from him.

V.I. Kuksa: The newspaper “Literární listy” was passed around there, remember when the events in Czechoslovakia were happening. It circulated in the camp, we all read it. And all sorts of articles that were published in samizdat, we read them in the camp. I have especially fond memories of Panas Zalyvakha. He worked all the time in the camp: he was always reading something, carving something. I even helped him drill those cigarette holders—drawing wasn't allowed, so he was engaged in that. Another thing he did—was to create a portrait of Shevchenko in the camp. Well, probably not just him, because when I arrived, there was already a huge portrait made of flowers. These were live flowers, a portrait laid out so beautifully in a flowerbed.

V.V. Ovsienko: Wait, out of flowers?

V.I. Kuksa: The kind that grow in flowerbeds. All sorts of small flowers that they sow. A portrait of Shevchenko made of live flowers. The guys looked after it; it wasn't destroyed. They were afraid to do that because 70 percent were Ukrainians. These guys generally brought order to the camps when the criminal element was rampant...

V.V. Ovsienko: In the late forties—early fifties?

V.I. Kuksa: When the UPA army arrived, an organized force, so to speak, they took crowbars and shovels and cleaned out all that riffraff—they were climbing the barbed wire, and they were hosed down with machine guns from there.

V.V. Ovsienko: Yes, I have many such stories.

V.I. Kuksa: This Mordovian camp, the one where I was—it was the first Soviet camp, established back in Lenin's time. Lenin created the first concentration camps. Captured Austrians were placed in this camp when Austria-Hungary was defeated. Captured Austrians ended up there. This camp dates back to then. And after the war, there were many captured Japanese there. They improved the c there were still a few gazebos that the Japanese had built. It was a beautiful camp, clean. The political prisoners maintained it. And after us, they say, the criminals there even burned down the barracks—making tea. And they killed the entire guard shift, slaughtered them.

V.V. Ovsienko: At one station there—I was being transported by convoy once and we stopped—you could see a memorial plaque that Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky had visited here in 1918. It was one of the first new constructions of the Soviet government. They laid a railway branch there and surrounded it with concentration camps—as early as 1918.

V.I. Kuksa: And people who were imprisoned there told me that from that camp—this was even before the war—no one came out alive. A released prisoner would be let out and given a travel ticket to go to the electric train. (Back then, a railcar ran. – V.O.). There’s a station from which they travel, I think, to Potma, and in Potma they would transfer to a train and head towards Moscow. There are birch trees there now. Well, back when I was there, the birch trees were quite large. And as soon as a person reached that point, a sniper would be waiting there and would kill that person. Released from the camp, and right there—poof—he’s gone. And they would bury him right there. The reason I'm telling this is because you weren't allowed to dig with a shovel anywhere there. They didn't allow digging anywhere, because if you dug, you'd find bones everywhere.

There was another interesting person in the camp, we called him the “Kyiv prince”—Petro Samokhval. He was from Kyiv himself, lived here on the hill in Pechersk, what’s it called... They took him for nationalism too. They gave him 25 years. When I arrived, he was in the invalids' barrack. When he was released, he came back, looked at the place where his house had stood—and went back to Mordovia to die. He was an interesting person, but he was old by then, I don't know if he's still alive.

Who else was in the camp? We had the burgomaster of Krasnodon, Stetsenko.

V.V. Ovsienko: Did you have a chance to talk with him, maybe you heard those stories about the Krasnodon Young Guards?

V.I. Kuksa: No, not with Stetsenko. We had Davydenko, with whom I worked in the same construction brigade. In fact, he saved me. Not from death, you can't say that, but at Kholodna Hora in Kharkiv, they gave us rotten vobla fish, and I got food poisoning from it. My stomach hurt so much that when they brought me to the camp, I couldn't find a moment's peace, everything ached. He looked at me and said: “Don't worry, you'll go to the industrial zone, I'll treat you.” He took me to the Estonians. There were large diesel engines from a submarine there—they provided light for the camp. Estonians worked on these diesels, well, like in a boiler room. They had pots of aloe. Big pots like that. I would go there with him, and this Uncle Stepan, as he was called, would break off the leaves. And the polish... Back then there were no chemical varnishes, only natural, fruit-based varnishes—they used them to coat furniture. And he would mix this varnish, add a little salt, throw all this in, and give me about 200 grams of this alcohol, and I would eat it with the aloe. And literally within a week, I was completely cured. So this Davydenko was Stetsenko's driver. Indeed, there were Young Guards, who are still talked about today.

V.V. Ovsienko: What do you know about this? Because now our Mr. President Kuchma is reviving the heroes of Krasnodon, wants to educate and teach patriotism to the younger generation based on these heroes.

V.I. Kuksa: I can tell you what I heard. This Uncle Stepan Davydenko, I don't know his patronymic, was apparently Oleg Koshevoy's stepfather. There were three of them: Stetsenko, Davydenko, and one other. Now I remember that the newspapers once wrote about their trial. In the camp, I learned: if you sign what we tell you to—well, the KGB—then you'll stay alive, but if not, then, as they say, you're done for. And supposedly they shot one of them, the third one, and these two remained alive. So I met them in Mordovia. Stetsenko was the burgomaster of Krasnodon, and Davydenko was his coachman. He, Stetsenko, says: “Harness the horses tomorrow, we're going, the Germans want to arrest Tyulenin and someone else there.” And the day before, in the evening, this Stepan Davydenko met with Tyulenin and said: “Seryozha, run, because they're coming to arrest you tomorrow.” Well, he and some other young guys didn't listen. Indeed, they came, and the Germans took them. And they were caught, as the story goes, because there was a German truck with gifts. This was before the New Year, there were Christmas presents. This truck wasn't locked, so supposedly they robbed this truck, and they gave the chocolate to a boy, I think, this Ivan Zemnukhov's son. This boy went out into the street with this chocolate, and some patrol saw the chocolate, and from this chocolate, they got on the trail of these boys. That's one episode.

V.V. Ovsienko: So they were arrested for that and...

V.I. Kuksa: Well, God knows what else, I don't know what their deeds were with this “Young Guard,” whether it was real or not, I can't say, I'm only telling what I know about these people, because I saw them both personally, and I spoke very closely with one of them, more than once, just like I'm speaking with you.

V.V. Ovsienko: Yevhen Stakhiv, a famous OUN member, was in the underground in that same Krasnodon, and he says that there was practically no Soviet underground there, there was an OUN underground.

V.I. Kuksa: OUN, that's right.

V.V. Ovsienko: And about these boys, he really heard something like what you're telling, and that's all. The theft of those gifts—that's really all there was to it.

V.I. Kuksa: Well, whether it was like that or not, if one were to gather all those archival documents, maybe something could be put together from it, or if, for example, Davydenko or Stetsenko were alive. He was already in his seventies then, and thirty years have passed—it's clear he's no longer alive. And this Davydenko was already about sixty then. They told him that he wouldn't get out of there, he knew that. Or that he shouldn't go back to where he came from. Well, they probably had such a conversation with the authorities, that they shouldn't appear there. He's probably not alive anymore either. He could have really told the truth about it, how it really was, because he was indeed the coachman for the burgomaster of Krasnodon, I know that for sure.

A few days before release, you have to turn in your things for a shakedown. Well, what did I have—nothing, some books. I came, and there's a procedure where they strip you naked and look everywhere, check, feel you, to see if you're taking anything out. (Laughs). They felt me up, I had nothing that would arouse any suspicion in them. That was in the morning. I waited until they issued me a passport there, in Mordovia. They issued the passport. Then one guy sat down with me…

V.V. Ovsienko: What, they issued you a Mordovian passport?

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, they issued a Mordovian passport. But when I arrived in Kyiv, no one would hire me with that passport. (Laughs). And they gave me the passport, and an escort sat with me, who took me and put me on the “Potma–Moscow” train. So I arrived in Moscow by myself, came home—and found my father already dead. Not in the house, but there, at the cemetery.

V.V. Ovsienko: And were you informed that your father had died, or did you not know?

V.I. Kuksa: I didn't know. Maybe I had already left from there. They say they sent a telegram, but...

V.V. Ovsienko: And did your relatives know the date of your release and not bury your father?

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, they sent a telegram, but the telegram and I missed each other.

And after that, of course, constant persecution…

V.V. Ovsienko: So you returned to the village?

V.I. Kuksa: No, I came to Kyiv. At first, I went to the village, stayed there for a bit. Then I went to Kyiv. A friend of mine offered: “Come on,” he says, “work the excavator, I have a spot, because they won't hire you anywhere now, come work for me on the excavator, I'll take you.” He hired me as an excavator operator. They didn't want to register me in Kyiv for a long time, even though I was taken from Kyiv. But then they finally registered me and I settled in the same dormitory from which I was arrested. But I was constantly, as they say, persecuted. Whenever something happened, the district police officer would summon me. At every police station where you live, there's a KGB agent, and you have to go to him, check in with this KGB agent, and he writes some papers, probably to higher-ups in the KGB. And this continued until the very end, until independence was proclaimed, all the time. It was worse than in the camp.

V.V. Ovsienko: You said that after your release you started communicating with the same people again?

V.I. Kuksa: Well, no one forbade me from walking the streets. I was unmarried—I'd finish work, get ready, and go. I'd take these routes, making sure I didn't have a tail. Vasyl Stus lived not far from me, so I often visited him. (At 62 Lvivska St., in Sviatoshyn. – V.O.)

V.V. Ovsienko: And did you know Vasyl?

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, I knew him personally. And I would just zigzag around, see that I had no tail, and then go to his place. I knew Ivan Svitlychny and visited them at home, I knew Alla Horska, visited her workshop, there, in Pechersk. Her workshop was not far from the Pechersk bridge.

V.V. Ovsienko: Aha, yes, yes, I know, Borys Dovhan works there and someone else.

V.I. Kuksa: Semenko's (?) workshop was a little separate there, and it's still there. Ivan Rusyn (he was supposed to come here today), Panas Zalyvakha—all the Sixtiers who were in the camps—I maintained contact with all of them.

V.V. Ovsienko: And the arrests of 1972, did they affect you in any way, did they search your place?

V.I. Kuksa: They conducted searches, said: “We'll lock you up anyway.” They summoned me to the prosecutor's office in Pechersk. What's the name of that street? They summoned me there, my notebook is probably still there to this day, they didn't want to give it back, they said: “Let us give you a ruble, but we won't give back the notebook.” And there were phone numbers written in it.

Wherever I worked, they wrote denunciations against me. When independence was already proclaimed, I was riding a bus once... I was working at “UkrNIIProekt,” the coal industry institute. I worked there as a section foreman. I had measuring instruments in my section. Two brigades of people worked there. We had five sections, and a foreman for each section. I had already left that institute, moved to “Ukrnafta,” and I'm riding the bus, a guy comes up to me, says: “Vitya, I'm looking at you—and my conscience is clear before you.” I look at him: “Why?” He says: “Everyone wrote denunciations against you, but I,” he says, “didn't write any. They pressured me so much, asked me: ‘You write one too,’ but I never wrote a single denunciation against you. And now I look at you—and my conscience is clear before you.”

V.V. Ovsienko: And did you know that man or not?

V.I. Kuksa: Well, he also worked as a foreman. Everyone who worked with me wrote denunciations, and I couldn't work there for long. You work for a while, you look, and you've already got a tail—you have to run, because you can already feel them, as they say, breathing down your neck, you're forced to flee from there. And this continued until independence was proclaimed. Only after that did the last KGB agent from this institute, where I still work, disappear. Where he went, I don't know, only the office where they sat remained.

V.V. Ovsienko: You say you worked at various jobs. What is this last institute called?

V.I. Kuksa: It's now the Ukrainian Oil and Gas Institute, where I work.

V.V. Ovsienko: And when public organizations started to emerge in, say, 1987, particularly the Ukrainian Culturological Club, did you participate in it?

V.I. Kuksa: No, I didn't participate in the Culturological Club, I was just interested in all of it. Then, after the Culturological Club, came the rallies, and completely different clubs.

V.V. Ovsienko: So you participated in those?

V.I. Kuksa: In all of them, all the ones I could.

V.V. Ovsienko: And were you a member of any organizations? There was the Helsinki Union.

V.I. Kuksa: No, I didn't join the Helsinki Union. It was, that Union, arrested literally before my eyes.

V.V. Ovsienko: That was the Group that was arrested, we're talking about the Union from 1988 onwards. And what do you know about the Group?

V.I. Kuksa: I know that people came from Oksana Meshko to sign a statement, and we literally just missed each other. If I had come earlier or stayed a bit longer, I would have signed that statement. They brought it to the bandura player Mykola Lytvyn, and I was visiting him. He had just had a baby, the room was tiny, life was so difficult there, and they came with those papers for him to sign. I can't say how, whether he was supposed to sign it, or if they first came to say they would come—I don't remember now, it was a long time ago. I came, but I didn't meet the people who came to sign this paper for the Helsinki Union. So I didn't sign it. And if, of course, I had met them, I would have signed and would have been tried a second time—that would have been a guarantee. But we missed each other. I knew those people later—Oles Berdnyk and whoever else was in that Union.

V.V. Ovsienko: You're talking about the Group, not the Union. The Union was from 1988, and the Group was from 1976. It included Oles Berdnyk, Mykola Rudenko, Mykola Matusevych, Myroslav Marynovych, Olha Heiko...

V.I. Kuksa: None of these people came to me. As I said, they approached Mykola Lytvyn, and I was supposed to go there. I don't remember this episode—whether I was supposed to come, or I had already left, and they were supposed to come to sign a statement in defense of that Union. Whether they had already been arrested, or were about to be arrested…

V.V. Ovsienko: And in the late eighties and in the nineties—were you in any organizations, parties?

V.I. Kuksa: When the Ukrainian Republican Party was being organized, I was invited to join.

V.V. Ovsienko: Maybe Petro Borsuk? He lived somewhere around here.

V.I. Kuksa: No, Petro Borsuk was in Rukh. He's a good acquaintance of mine. I don't call him often, but sometimes I do. But the last time, when he told me how Boyko paid them their salaries, he left that Rukh and is now outside of Rukh. They asked me to support the Republican Party, I was in the chapter of the Sviatoshyn or Leningrad district, we used to meet there on Tupoleva Street. I went to a few meetings, and I'll tell you honestly, when I got to know that contingent, there were probably as many provocateurs as there were members. And I stopped going there. I concluded that the party had barely had time to organize, and provocateurs were already joining it, organizing it, and then saying it's a party. I was there for a few months, went to maybe three or four meetings, looked around—provocateurs, what was there to do? So I stepped away from it.

V.V. Ovsienko: Alright, but on the other hand, you got married and have a son—tell us a few words about that too.

V.I. Kuksa: I got married, this is my little wife Maria.

V.V. Ovsienko: When did that happen?

Maria Polishchuk: In 1973.

V.I. Kuksa: Well, and the boy—Vladyslav.

M. Polishchuk: 1992.

V.V. Ovsienko: What grade is he in?

V.I. Kuksa: Third grade.

M. Polishchuk: He'll be ten on March tenth.

V.I. Kuksa: They're on an accelerated program now—he's finishing third grade and going into fifth, they don't have a fourth grade. Well, to be honest, he's my friend and my support. In a national sense, may God grant all Ukrainian men to have wives like mine. Then all men would be happy.

V.V. Ovsienko: At least you have that happiness—and that means a great deal.

V.I. Kuksa: And indeed, whoever you ask—he married someone from Ryazan or some other place. And it's always the case that when some patriot gets married, it's to some woman from far, far away. And then come the children, and then the problems...

V.V. Ovsienko: But you were lucky in that regard, I see.

V.I. Kuksa: And in this, as they say, I was lucky: I have a wife who is truly nationally conscious, may God grant her health.

V.V. Ovsienko: And where are you from, Mrs. Maria?

M. Polishchuk: From the Cherkasy region.

V.I. Kuksa: Cherkasy region, Mankivka district, village of Krasnostavka.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what is your maiden name?

M. Polishchuk: It's still mine—Polishchuk. I didn't change it. There was the diploma… I'm a graphic artist, this is purely practical work, although my education is in electronics. But since they pushed me out… I worked at VUM—the computer factory, as it's called now. Viktor worked there, that's where we met. Well, they pushed me out there...

V.I. Kuksa: For nationalism.

M. Polishchuk: Yes, yes. And the pecking, and the pecking... I was summoned to the First Department—I had to resign. And work, as you know, is hard to find... And then friends from a publishing house helped me. But I had to work there. It was graphics, technical illustration for textbooks, books, monographs. So I worked there for another 14 years. My husband supported me a little, and I him, and that's how we worked and lived.

V.I. Kuksa: And we're still living.

V.V. Ovsienko: Good. And do you still have a friendly relationship with Moskalenko?

V.I. Kuksa: Well, we never, as they say, divided anything, never quarreled, like it sometimes happens that co-conspirators don't get along. To say we're great friends—no.

M. Polishchuk: Because he lives in Bucha.

V.I. Kuksa: You have to travel—either him or me. Well, when something is needed, we go.

M. Polishchuk: He has a family, his own problems there.

V.I. Kuksa: We don't have any disagreements or dissatisfaction with each other.

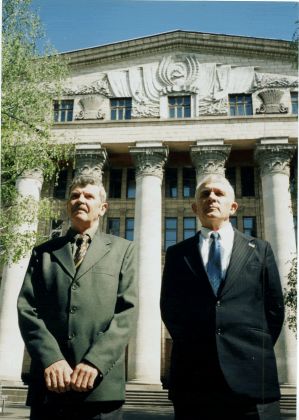

V.V. Ovsienko: We should somehow get you two together and take a picture. There are a few publications, there's this picture that appears in the newspaper—you took it the day after your “crime.” It would be good to find it, scan it, and take a new picture. Then we could make a good publication. I would like to do that, if possible, by May 1st. And what about rehabilitation? You haven't told us about that yet.

V.I. Kuksa: Everyone has tried to take on this case, but the judges who were there then are still there to this day. That second article, 222, which they hung on us—it's still there to this day. And no one can remove it. If you think about it, we're probably not even needed by the state, although the same president and the same judge sit under the same symbols that I carried to the roof of the institute, for which I served time. You see how it is—everyone sits under those flags, and I'm a state criminal.

V.V. Ovsienko: But you were rehabilitated...

V.I. Kuksa: On May 22, 1994, Article 62 was dropped, but Article 222—the knife—remained. This is the knife with which I cut down the red banner and hung our national flag on the same pole. For cutting down that banner with a knife—that article is not being removed from me.

V.V. Ovsienko: It's such a paradox that the accompanying article remained, while the main one was dropped. Like with the guys in Chortkiv in 1973 who also hung flags. One of them, Petro Vitiv, was 16 years old. So for Volodymyr Marmus, the group's leader, Article 62 was dropped, meaning there was no crime, but the article “involving a minor in criminal activity” remained.

V.I. Kuksa: The Supreme Court, which reviewed this, decided that I am a state criminal to this day.

V.V. Ovsienko: You probably already know that on March 18 of this year, 2002, the founding meeting of the Public Committee for the Rehabilitation of the “May Day Two” took place. Present were Hryhoriy Volodymyrovych Hrysiuk, head of the Kaharlyk district organization of the Green Party; myself, Vasyl Ovsienko, as coordinator of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group program; Valeriy Oleksiyovych Kravchenko, head of the Kyiv organization of the Democratic Party of Ukraine; and Serhiy Serhiyovych Tauzhnyansky, co-chairman of the Kyiv Council of Citizens' Associations. We established the “Public Committee for the Rehabilitation of the ‘May Day Two’” and set ourselves the task of creating a precedent—to achieve the full rehabilitation of you and Moskalenko. Of course, we could have taken on a bigger piece at once, that is, to say that there are many such cases, but God grant that we create one precedent of rehabilitation, one fact. Then it will be possible to raise the issue of all the others. We submitted information to the press. You went on Radio Liberty, right?

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, I went on Radio Liberty.

V.V. Ovsienko: That broadcast was shortly after March 19.

V.I. Kuksa: They said it would be on Thursday or Tuesday, or today. The journalist said we wouldn't have time today. Then a friend of mine calls me: “Did you listen to Radio Liberty?” I say: “No.” “They were,” he says, “talking about you today.” I say: “They said they would broadcast on Thursday.”

V.V. Ovsienko: Now that May 1st is approaching, we need to prepare a publication or two, this case needs to be promoted, public opinion needs to be created around it, and pressure needs to be put on the authorities. Especially since the Verkhovna Rada will be better now, we need to push for the adoption of a new law on rehabilitation, because draft projects have been developed. The Society of the Repressed took part in this, and a whole number of people. It should be a much better law than the one from 1991, more categories of people will be rehabilitated. We need to push it through the Verkhovna Rada. And things like what you have hanging over you must be removed.

Well, we've had a good conversation, clarified this picture. I thank you for the story, and your wife, Maria. This was on April 10, 2002, in Kyiv. [Dictaphone turned off].

V.V. Ovsienko: Tell us more about Sinyavsky.

V.I. Kuksa: I can say a few words about Andrei Sinyavsky. I know him from work. We met in the industrial zone during the second shift, when it was necessary to remove sawdust from the workshops. This sawdust was burned in the boiler room. During the day, I worked on the excavator, and for the second shift, they sent me to a DT-20 tractor, a small tractor. I would hook up these wagons (made of plywood) and pull them along the narrow-gauge railway to the boiler room to be burned. I was on the tractor, and Sinyavsky would load this sawdust and accompany me, because these wagons often derailed. A lot of snow fell, so he would walk either in front or behind. When it got badly stuck, I would stop, get up, and help him put the wagons back on the rails, and we would bring them to the boiler room to be burned. Sometimes I managed to talk with him. Well, what can I say—an exceptionally educated man, a man of high culture and morals. But to say that I was friends with him—no. That's all I can say about Sinyavsky.

V.V. Ovsienko: Good. About Stus.

V.I. Kuksa: I had one such episode. I'm walking to Vasyl Stus's place. There's a small street leading to his house, lined with old linden trees, I look...

V.V. Ovsienko: This was when he lived in the dormitory on Vernadsky, right?

V.I. Kuksa: No, when he lived in Sviatoshyn.

V.V. Ovsienko: Ah, at 62 Lvivska?

V.I. Kuksa: Yes, yes. I look, and there's one “paddy wagon” under one linden tree, and another one a little further away. After the camps, I already understood a thing or two about these matters. I see that these “paddy wagons” aren't there for no reason. There are people sitting in these “paddy wagons.” I know what kind of people they are, by their appearance. And a bus from the train station used to go there, and, I think, tram number six. So I didn't go to Vasyl's house, and I'm not going to my own dormitory either. I think, if they've come to take Vasyl, they'll definitely come for me, because I lived nearby, on Lvivska. I think, I'll go to Ivan Rusyn's place. And Rusyn lived on the left bank in Rusanivka. Just as I'm approaching the tram—Ivan Svitlychny gets off. I know where he's going, so I say: “Ivan, don't go to Vasyl's, there are ‘paddy wagons’ there—either they're conducting a search, or... Well, they've come there for some reason, these ‘paddy wagons.’ They're probably conducting a search, most likely.” Ivan also stopped. And sure enough, they were conducting a search at his place then.

V.V. Ovsienko: That was before 1972, right?

V.I. Kuksa: I don't remember what year it was, but Vasyl hadn't been convicted yet, and Svitlychny hadn't been convicted yet either, but he already had a “tail.” This is what happened before my eyes, I saw those cars myself and warned Svitlychny not to go in there.

V.V. Ovsienko: Such incidents happened. On January 12, 1972, they were searching Ivan Svitlychny's place, and Ivan Dziuba happened to come by, so they held him there until the end of the search. But they didn't arrest Dziuba then; they took him home, searched his place, and let him go.

V.I. Kuksa: And if I had gone to Vasyl's, and Svitlychny had come right after me, I don't know what would have happened... Whether they would have put us in those “paddy wagons” or not, it's hard to say now, but there would have been trouble.

V.V. Ovsienko: Thank you. [Dictaphone turned off].

V.I. Kuksa: Once I come to visit my mother, and my mother says to me: “Chop some wood, son.” I took the axe and started chopping wood. I raised the axe, about to split a log, and I look—an old man is standing by my gate and looking at me. I just lowered the axe. He looked at me, took off his hat, and bowed low, very low to me. And then he asks: “Are you Ivan's son?” I say: “Ivan's.” He says: “He was a good man, God rest his soul. But,” he says, “you're not a bad lad either. I,” he says, “know all about you.” He put on his hat and left. I stood there for a few more minutes and didn't know what to do.

V.V. Ovsienko: So did he say “not bad” or “good” lad?

V.I. Kuksa: A good lad.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what, was that old man from your village?

V.I. Kuksa: From our village.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what was that old man's name?

V.I. Kuksa: I think the old man's name was Lehor (That is, Hryhor. – V.O.), his house was the last in the village, and if you're coming from Olshanytsia, it would probably be the first.

Later, a young man, a surgeon, came to visit me from Kyiv. I was showing him the fortress of Kyivan Rus. The Pechenegs used to attack, and there on the Ros River stands a fortress to this day. It is surrounded by a large earthen wall, right by the Ros River. I decided to show him this fortress. And on our way back from the fortress, we passed this old man's house. I say: “Let's stop by this old man's place.” We went in, and the old man, with such humor, began to ask us where we were from, where we had been. We told him. It came, as they say, to modern life, and the old man says: “Eh, it's good to live now.” “Why, grandpa?” “Because you don't have to think: they've already thought for you long ago. You go to work today—they'll tell you where to go, what to take with you, whether a pitchfork or a rake. They'll definitely tell you. So you don't have to think. And they'll tell you when to leave work. So life has become wonderful.” I don't know, that old man has probably passed away by now, but that episode is still before my eyes.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what—when an old man, an old grandfather bowed to you—that is a high honor for you! He knew what he was bowing for.

V.I. Kuksa: That's true. When I remember this, when I go over the people from this village in my memory—I rarely go there now, only for Memorial Day to visit the graves—I always remember this old man, how he stands before my gate, looking at me, and I stood and looked at him. It lasted a few seconds, and then he bowed low, very low.

DECREE OF THE PRESIDENT OF UKRAINE NO. 693/2006

On awarding the Order “For Courage”

For civil courage, demonstrated by raising the national flag of Ukraine in the city of Kyiv in 1966 and in the city of Chortkiv, Ternopil region, in 1973, and for active participation in the national liberation movement, I hereby decree:

To award the Order “For Courage,” 1st Class, to

VITIV, Petro Ivanovych – builder at the agricultural enterprise “Rosokhatske,” Ternopil region

VYNNYCHUK, Petro Mykolayovych – builder at the agricultural enterprise “Rosokhatske,” Ternopil region

KRAVETS, Andriy Mykolayovych (posthumously) – former resident of the village of Rosokhach, Ternopil region

KUKSA, Viktor Ivanovych – engineer at the joint-stock company “Ukrainian Oil and Gas Institute,” city of Kyiv

LYSYI, Mykola Stepanovych – pensioner, village of Rosokhach, Ternopil region

MARMUS, Mykola Vasylyovych – pensioner, village of Rosokhach, Ternopil region

MARMUS, Volodymyr Vasylyovych – head of a sector of the Chortkiv Raion State Administration, Ternopil region

MOSKALENKO, Georgiy Mytrofanovych – pensioner, town of Bucha, Kyiv region

SENKIV, Volodymyr Yosafatovych – machine operator at the collective peasant enterprise “Sosulivske,” Ternopil region

SLOBODYAN, Mykola Vasylyovych – pensioner, village of Rosokhach, Ternopil region.

President of Ukraine Viktor YUSHCHENKO

August 18, 2006