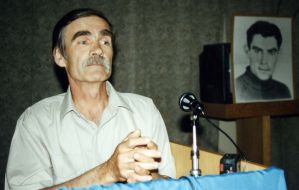

An interview of Vasyl Semenovych LISOVYI with Vasyl Ovsienko and Vakhtang Kipiani. Last read-throughs on 01.12.2008 and 09.29.2013. During his lifetime, in September 2010, V. Lisovyi ordered it removed from the KHPG website because his more extensive memoirs exist: Lis-Spohady-mij text-08-2010 https://museum.khpg.org/1281364212. Given the value of this oral autobiographical account, we are restoring it to the KHPG website on 09.29.2013.

V. V. Ovsienko: October 9, 1998. We are listening to the story of Vasyl Semenovych Lisovyi at his home in Kyiv. The recording is being made by Vasyl Ovsienko, and Vakhtang Kipiani is filming it on videocassette.

V. S. Lisovyi: I, Vasyl Lisovyi, will try to tell my story as concisely as possible, because I’m afraid I might get sidetracked, and then this story will drag on for a long time. There are too many facts that I would like to recall and talk about. I was born in the village of Stari Bezradychi, not far from Kyiv, in the Obukhiv district. Next to this village is Novi Bezradychi. Stari Bezradychi is located near the Stuhna—a river from the chronicles. It has several hamlets—Kapustiane, Berezove—and I was born in one of them. This hamlet is situated on the southern bank of the Stuhna, running along the river. There are two roads there—one Upper, the other Lower.

During my imprisonment, they were renamed: one to Taras Shevchenko Street, the other to Alexander Pushkin Street—in honor of the friendship of peoples, so to speak. Healthy peasant common sense called them Upper and Lower because one is located on a hill, actually on a kind of sandy, fluid ground deposit, many of which are found in the lower Dnieper basin. The kitchen gardens run right down to the Stuhna itself, and these two streets are situated along the Stuhna. My first impressions are related to the war. My memory illuminates almost nothing before the events of the war, its beginning; just some very dim pictures. But the war period—those are very vivid pictures. I could talk a lot about that time, about the war period, but I'll say something basic. I remember the entrance of German machine-gunners, who rode into our village quite ceremoniously, because the Soviet troops had retreated and were surrounded, so the Germans entered the villages ceremoniously, without any fighting. We boys were standing on the street, and I said, I think, the word either “Fritz” or “fascist.” And then I heard the first warning that would appear more than once in my life, in the lives of my friends, my peers—one of them said, “Be careful, it’s dangerous” or “Be careful, or they’ll hear you.” I don't remember exactly how it was said.

Our first childhood toys were shell casings and various other military items—starting with packaging. What else stuck in my memory was a kind of raggedness, the chaos of that wartime life, that continuous uproar. And when our troops were advancing, the battle took place right in the village. We hid in my uncle's cellar, and most people hid like that. I remember that with every explosion, I would scream. Shells were flying over our cellar and landing. We hid in my uncle's cellar because there was a battle, and a shell or a bomb could fly directly into our dwelling, into the house. I was born in 1937, and in 1943, when Kyiv was being liberated and the Red Army was advancing, I was already six years old. What needs to be said? I would like to divide my impressions into positive and negative. The positive impressions—the ones that are foremost in my mind and have constantly nourished me since childhood—are the impressions of the diversity of nature. It's a forest-steppe, and the garden of our house abutted an oak grove—a very diverse forest, where I constantly walked throughout my youth. On one side, there were floodplains, a swamp where we would pick sweet flag for Green Sunday (Pentecost). We called it Tatar herb. And over here, near Kozyn—which is past Novi Bezradychi—there was a pine forest. I particularly remember the spring rustle of the oak grove as it awakens, when spring is announced—the still quiet, barely audible murmur of the grove. The second point, related to nature and the village's location, is the historical memories.

In Bezradychi, there was a hillfort (in fact, it is still there, this hillfort); it was later excavated. I don't know the results of those excavations, but we kids used to wander around that hillfort, imagining how the Tatars attacked, how our people defended themselves against the Tatar onslaught. It was very steep, and it remains very steep—with almost vertical slopes. We loved to wander through these places, these hills. This feeling of the breath of historical memory with which the land is filled—I rarely meet people now for whom the earth seems to speak of those events and even with the voices of the people who fought here, whose history is hidden somewhere in this land. These impressions are also childhood impressions. I must also mention other positive impressions, or a whole sphere of impressions—the remnants of Ukrainian ethnoculture. At that time, after the war, the customs were still very much alive. In fact, their destruction only began in the Khrushchev era, or perhaps in the Brezhnev era. At that time, all these rites and customs were alive. I was a part of them; I saw weddings with the full ritual performed: the bride, dressed in national attire, would come, invite people to the wedding, and bow. Women kept chests with embroideries, with clothing. I have photographs of people in embroidered attire. Every woman, not just a young girl, cherished this as a kind of relic.

The impressions of ethnoculture, of these customs, are very important. They are also a nourishing source for me, one of the memories that constantly lived on, and in difficult moments I would return not only to nature but also to ethnoculture. But despite everything, if we don't count the fact that our house was truly embraced by greenery and this oak grove, that this grove seemed to rock our house and hold it in its gentle palms—the other side of our village life was quite sad and difficult. The first difficult impression was the death of my father in the war. He was taken in forty-three, because at the beginning of the war he was not of age, but at the end of 1943 they began to take both younger and older men, so my father was taken too. Most of the youth who were taken in forty-three, and the older men, were not even trained, often not even given new clothes; they were thrown, untrained, un-uniformed, almost without weapons, against German machine guns right here nearby, in the steppes of Ukraine. And my father died the same way. Some of our people went into those steppes and brought back their killed relatives. A truly very difficult childhood, in terms of living conditions, began. The house was falling apart, and there were three of us young children left, as one brother had not yet returned from Germany. The Germans had taken him to Germany. He was liberated by the Americans and refused to go to the West because he wanted to return to Ukraine. Many made that decision—but they were sent directly by train to the mines of Karaganda. He had to work off a two-year punishment for having been forcibly taken to Germany for labor. A cousin of mine died in Germany. He had a very interesting correspondence with her, and I had their very interesting poetic postcards, from which I memorized some of the poems that Natalka Lisova had composed.

There were three of us little ones with our mother. Mother fell gravely ill somewhere around 1944 and suffered from a very severe heart condition for the rest of her life. But she fought for our lives—my younger sister's, mine, and my older brother Fedir's. Fedir went to work on the collective farm early to help out somehow. But my entire childhood, and not just mine, but that of many children whose fathers, whose husbands, had died, was difficult. Because if a father returned, he could still earn something on the collective farm or repair the house. But for those whose fathers did not return, childhood was very difficult in terms of living conditions. The house leaked, and we no longer knew where to hide, as it was covered with iron sheets, and there was no way to re-roof it. The only thing that saved us, and in particular saved us during the 1947 famine, was that our mother refused to sell the cow, no matter how hard it was for a woman to get hay, as she couldn't mow. Mostly, men would mow somewhere, and she had to reap with a sickle and carry it in bundles. But she didn't sell the cow, and that helped us a great deal. It's true that in 1947 my brother Pavlo returned from the army; he had been taken to the war as a younger man, and then some regulation was introduced that those who had gone through the war but had not served in the army before the war had to complete their service. So he remained in the army and then returned in 1947. He traveled to Western Belarus and brought back some bran, but by the end of 1947, we had run out of everything—there was only the milk that mother divided among us, I don't remember how much, maybe half a liter per child and a liter for the older one—that was my brother. But we were already trying to bake some kind of pancakes from acorns—we would grind the acorns and try to bake... In short, this domestic side of life was filled with serious anxieties and harsh impressions. But I think that was typical for our post-war generation. I had to go to school. I started about a year late.

I don't even know if it was functioning in the first year after the war. We had to walk across the Stuhna to Bezradychi, to the center. It's quite a long way. Back then, the road was not paved. The left bank towards Obukhiv is sandy, but on the other side of the Stuhna, the clay began. That muddy, clay road... I remember one time I was walking in valenki, I got stuck somehow and lost a galosh. No matter how much I rummaged in that mud, I couldn't find the one galosh. Mother sewed the valenki by hand, but we bought the galoshes. That was how we dealt with the situation of having something to wear on our feet to get around in winter. It was early spring, snow with slushy clay, and I lost a galosh. It was a great drama and a great ordeal. I walked home from that spot praying the whole time, because it was an exceptionally great loss. I prayed because I knew what a blow it would be for my mother. But I finished the seventh grade. I must say that my love for learning was awakened somewhere in the sixth or seventh grade. Starting from the fifth. Before that, my friends and I mostly wandered around the cliffs and ravines, fantasizing, and only around the fifth grade did some inclination towards history, and then towards literature, awaken—humanistic interests.

I finished the seven-year school with some C's—in mathematics and a foreign language. And in Obukhiv, there was a secondary school. When I applied there after finishing the seventh grade (there was no secondary school in Bezradychi), they told me: “You know, we get many applicants from the neighboring villages, and we select them. You have C's, so we won't accept you.” Thus, I had to stay home for a year. For a while, I went to a construction site. At that time, trucks would come to the villages and pick up workers for the roads, for construction sites in Kyiv. Between the seventh and eighth grades, I worked on a construction site where the tram now descends to the “Kyianka” store.

V.O.: Klovskyi Descent.

V.L.: Klovskyi Descent. I can still see that building now. Back then, a truck would bring us, and we would dig a trench. It started to get cold in the autumn, and we rode on top of a regular cargo truck. People traveled to Kyiv on top of trucks back then, driven by so-called *kalymshchyky*, who were earning extra money this way. Women, mostly, would bring ryazhenka or some fruit to Kyiv to buy bread. And they would bring back bread, sugar, and sometimes they could buy some clothes. Then my mother persuaded me to leave that construction job.

I was quite frail. Since childhood, I had suffered from a severe middle ear infection; I moaned for a long time, and then the pain was somehow eased a little, it subsided, but it constantly suppurated. This went on for, I don't remember how long, two years or so, but I remember I suffered a lot. Then the pain subsided, it seemed to have healed, but it still acts up sometimes even now. In high school, it was just me and my younger sister, Luba—she lives here in Kyiv now. We constantly heard our mother's moans—she was gravely ill from time to time. It was a difficult psychological situation. She would be in the hospital, and when she returned from the hospital, she would throw herself back into hard labor; she couldn't leave it because she had to support us somehow. I went to secondary school a year later. A secondary school opened in the neighboring village of Velyki Dmytrovychi. And before that, for a year, I read a great deal. I constantly borrowed literature—there was a library at the club in Bezradychi. There was all sorts of literature—laureates of the Stalin Prize, and *Far from Moscow*, and so on, but among them, some very valuable literature could be found, and I am grateful to fate that I managed to read such valuable literature.

I must say, regarding my intellectual and spiritual interests, I was fortunate in some respects. I observed not only the remnants of ethnoculture. I had three uncles—my father's brothers...

V.O.: Please state their names.

V.L.: They were Savka, Musiy, and Anton. I must say, they helped us little in our daily life, almost not at all; everyone was somehow busy with their own affairs. But Musiy had saved many books. For example, the journal *Osnova*, where I first read some poetry—this was early, maybe in the fourth or fifth grade. He kept a *Kobzar*. I first read the *Kobzar* at his place. I was also impressed by the illustrations for the Bible—he had arranged these little cards in a corner of the house. They were illustrations for the Bible. When I entered the first room of their house, the door to the second room was ajar, and in the glint of the sun, I saw these illustrations for the Bible—the Dead Sea… These unusual pictures from early childhood were etched in my memory. He also kept the journal *Vestnik Evropy*. And the *Kobzar* in a dust jacket with people holding pitchforks—do you remember that *Kobzar*?

V.O.: Yes, the illustrations by Kasiyan.

V.L.: I am especially grateful to him for the *Kobzar*. I started writing poetry back in elementary school, stylizing it after Shevchenko. Later, however, I gave it up. In secondary school, my interests shifted from the humanities to the natural sciences, and specifically to mathematics. I read extra material—there was some kind of turn towards mathematics. In the secondary school of that time, when my generation was studying, some wise person had introduced such fine and concrete subjects as logic and psychology. The psychology textbook, as I recall, was by Teplov. Logic and psychology—that was the beginning of a philosophical education. I would like to get a hold of those specific textbooks someday. They made a very good impression on me then; they were so wisely written. At least, as far as I remember, very simply and accessibly, and at the same time clearly, without any superfluous verbal baroque. Later they introduced this social studies. I looked at those social studies textbooks that the poor students had to learn from—it was horrifying. In secondary school, I was already a straight-A student, finishing each grade with a certificate of merit, and I graduated from secondary school with a gold medal. It was the first gold medal for the Velykodmytrivska school.

V.O.: In what year was that?

V.L.: I graduated in 1956. The physics teacher took a liking to me, and I began to hesitate between the natural sciences and the humanities. I could enroll without exams, because back then, gold medalists could enroll without exams. And so I began to waver between the natural sciences and the humanities. In the end, I chose philosophy after all. I remember at the interview, Tancher, the dean of the philosophy department at the time, asked: “And what have you read in philosophy?” I had read the section of the history of the CPSU that covered Stalin's historical and dialectical materialism. And I had read some of Lenin's articles. I named those articles. “And what are they about?” I recounted something, I don't remember what exactly. So, my university years began. I had a dim idea of the environment I was entering. Probably, most of the village boys and girls who came to study at the university had a very dim idea of the intellectual and spiritual environment they were entering. But, I must say, our interactions were quite good.

Unfortunately, I didn't get a dormitory room for my first year, and I had to live in rather cramped conditions in one room with my brother Pavlo and his family. He didn't have an apartment—it was some kind of workers' barracks. I had to live there for the first year. The next year, I had to work in the summer on the construction of a dormitory being built on Chigorina Street; as a result, I was given a room in the dormitory in my second year. I settled in the dormitory on what is now Triokhsviatytelska Street, where the Institute of Philosophy is now located. Back then, it was a university dormitory, so I now work in the very place where I once lived. I must say that I developed rather slowly at the university, but I still chose a purely positivist direction—I went into psychology when the specialization began, and then I became disillusioned with psychology and, towards the end of my university studies, switched to logic. And then I applied to the graduate program in the Department of Logic. At first, it was the Faculty of History and Philosophy, but during our studies, it was divided into two departments—philosophy and history. At the Faculty of History and Philosophy, we took a course in history and a course in philosophy. When they made two departments, the students already studied separately in the philosophy department, which eventually became the Faculty of Philosophy. But all this was complicated by the fact that my mother was seriously ill, and before graduating from the university, I had to take a sabbatical.

I enrolled in 1956 and graduated in 1962, so I studied longer. But there was a fortunate circumstance in this—how did it happen? My mother was left alone in the village, because my sister had enrolled in a vocational school in Kyiv, as she was afraid of that collective farm. So, mother was left alone. She fell seriously ill, lived with my brother for a while, but it was just one small room in a barrack. Understandably, my brother's wife was not happy with this situation. So I had to take a sabbatical—and for a year, I once again immersed myself in walks in the oak grove, reading, and carrying firewood. The story with the firewood is this. Back then, you couldn't find a single twig of firewood in the nearby oak grove—everything was raked up, gathered. The forester, when he caught a woman with a bundle, would tear the rope, even though the women only collected dry twigs. Whether this was an order from above, I don't know, but people tried to sweep and rake up everything. So I would take a small saw, climb trees, and cut off the dry branches. It was a kind of test, because the trees—oaks and pines—are quite tall, and I would climb from branch to branch, risking a fall. And generally speaking, there were two such tests of will in my childhood: the neighbor's cow, which would attack. It had a disposition: if you don't run, but stand before it and hit it, it backs away, but if you run, it comes after you. I mean the risks, the tests, when fear grips you.

Similar tests were associated with gathering firewood, when you have to climb high trees, moving from branch to branch like a cat, very carefully, otherwise a dry branch will break—and that's it. And then you cut a few of those branches from the tree and carry them home, so there's something to heat with. So, during that time, that year, I had to carry firewood; I didn't work. And there was nowhere to work there anyway. So I read that year—it was very fruitful, just like in my childhood. This one-year break brought me together with Yevhen Proniuk, because he was a year behind me. I graduated from the university in 1962, and in the last year, the 1961-62 academic year, we came together, as we met in this course and soon became friends. During my student years, my worldview had more or less formed, mostly positivist—ideology, philosophy, and even dialectical materialism seemed vague, chaotic, and undefined, completely amorphous. I first went into psychology, then logic, and began to consciously get into so-called logical positivism—precision of concepts, definiteness, and all that. But my friendship with Yevhen, with whom I became close, was very significant for me. Until that time, the problems of national consciousness were somehow on the periphery for me; I did not clearly realize them. But communication with Yevhen forced me to get more and more involved in this problem.

This year of communication brought about a worldview shift. My philosophical preferences moved on their own, as I now had a certain methodology of logical positivism. But the worldview shift, and in particular, the appreciation of the national existence of the people, the problem of national self-awareness, and the problem of the nation in general, its ruin, its destruction, arose in full force. Moreover, at that time, Yevhen already had access to some samvydav materials. This was 1962. I remember bringing Symonenko's poems (I mean the unpublished ones) with me to Ternopil, where I went to teach philosophy. At that time, I think, Symonenko's first book hadn't even been published yet, when I brought a typewritten booklet of his poems. These were the first samvydav materials that were at hand. When I arrived in Ternopil, I was already nationally conscious. The task was how to transform this national consciousness and spread it among the students. The main problem was how to speak on the topic within the official curriculum, while at the same time saying something to affirm national consciousness, national dignity, and so on.

I came up with various approaches. I was willing to teach historical materialism. And there I would choose topics like internationalism and transform them accordingly, saying that internationalism is not the destruction of a nation, but tolerance for national culture, for national identity. I said that there is a defensive nationalism—it was stated in the program that it should be distinguished from aggressive nationalism. You know how that could be presented within the framework of the ideology of the time, how with skill one could transform it to deflect accusations of being anti-Soviet or a nationalist. It worked. There was one very favorable circumstance.

On the department where I came to work, there was Leonid Kanishchenko. He later served for a time as deputy minister of education in independent Ukraine. He became the Party organizer of the institute, but this man was very wise and courageous. He was an economist by training. He knew the whole machinery of the state at that time and the Party machinery. And he knew who I was—that I was nationally self-aware—and he knew how to shield me accordingly. That is, I had some indirect support and mutual understanding. Of course, one had to be wary of those who definitely want to catch you at something. But if you value working with young people, then to give them something, you must act cautiously. But what we also did then—Kanishchenko entrusted me with heading the editorial board of the institute's wall newspaper. I went up to the wall newspaper, looked at how it was made—it was a kind of box where they pasted something very formal. And that box was divided, with strips of text pasted into it. The headline was cut out. First—we got rid of that box and made a free-form newspaper: a large sheet on which we placed poems by Lina Kostenko, Ivan Drach, Vasyl Symonenko, and then we decorated it. I managed to assemble a good editorial board. It included Petruk-Popyk—then a student at the medical institute, Stepan Babiy—he later published his poetry, I think, in *Vytryla*, and in other almanacs. A few more students. Petruk-Popyk later played a major role in the Rukh movement in Ternopil and the Ternopil region. We started publishing this wall newspaper.

One time, the KGB collected our wall newspapers and told Kanishchenko to summon me for a talk as well. Their complaints were about where I get the materials we publish in this wall newspaper. And I, of course, had calculated that such a move was possible, and, of course, I didn't include any samvydav materials there. The patriotic materials we could find in the publications of Lina Kostenko, Drach, Symonenko, and others were enough for us. I said: “We take these materials from official publications, all of this is permitted, there is nothing here that would arouse your suspicion.” They asked me to bring the little books. I brought them, and on that, the conversation was exhausted. But it's interesting how the Party organizer Kanishchenko reacted. I said: “Leonid Oleksiyovych, maybe it's not worth risking this?” He understood that there were lectures, there was the spoken word. “What do you think? It seems to me that we could just stop making that wall newspaper, one that is so provocative.” He says: “Don’t pay any attention to it. Everything is normal. You showed that you take everything from ordinary books.” He knew this machinery, knew that as long as we stayed within certain limits, they couldn't shake me, that is, couldn't get me fired from teaching. That's roughly how I understood the situation. I must say that I also found mutual understanding among some Ternopil residents, in particular, from Ihor Hereta. (Hereta, Ihor Petrovych, born 25.09.1938 in the village of Skomorokhy, Ternopil region. In 1962, graduated from the history faculty of Chernivtsi University, worked at the Ternopil Regional Studies Museum. Arrested 27.08.1965, sentenced to 5 years probation under Art. 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR. – V.O.)

I remember that after his suspended sentence, I decided to talk to him. It so happened that I met him at the opera house. I told him that I wanted to talk to him about the situation in Ukraine. And he quickly-quickly pulled me from the lobby to a remote corner of this opera house. He was more experienced, he knew that there might be some listening devices installed here in the lobby. I remember his characteristic phrase: “But you have an audience—you have great opportunities!” So he kept his distance, so as not to involve me directly, so that I could do what I could in my own field.

I must say that at one time, Yevhen Proniuk also wanted to involve me in more active work—I mean in samvydav. However, for me, working with young people at the university was a very serious area, and of course, sacrificing or risking this work would have been unjustified. What did I observe then? That this ideology had already begun to grind down the youth and people in general, even in western Ukraine. In the Ternopil institute, people from the villages, doctors who had already defended their dissertations in medicine, refused to lecture in Ukrainian. This surprised me.

Some of the local people—graduate students, even some lecturers—kept their distance from me, and some even argued with me. I recently met a woman who asked for my forgiveness, saying that back then she had almost called me a nationalist. And at that time, despite all my caution, I was told that I was already being called a nationalist there. But there, of course, they first offered me to join the Party, and the head of the department said this: “You work in an ideological department, you understand that this is ideological work. We have no non-Party members.” I thought, I stalled a bit with this, and then I thought: I have to decide—one way or the other. Of course, the work with the youth and the audience must be valued above all, because we saw that Russification was spreading there too. Of course, some of the students came from Russia, but the vast majority were still locals, with the Ukrainian language. But I could see that this ideological plague of communism and Russification was spreading even among them. Around sixty-five, I came to Kyiv for about six months to take advanced training courses. Here I became involved in active work related to samvydav. It was possible to do it here. But in Ternopil, combining teaching with the distribution of samvydav—that was impossible.

Ihor Hereta had his own circle—that's understandable. Later, while in graduate school, I combined teaching at Kyiv University with distributing samvydav. But in Ternopil, it was harder for me. Maybe because I was younger, I didn't have the experience yet. And the environment was less known to me. I could have easily made a mistake there if I had started distributing samvydav. And I refrained from such widespread distribution in Ternopil—only to my closest friends, especially the graduate students with whom I was friends, such as Anatoliy Palamarchuk, Baykura, and a number of other friends of mine at the time. These were mostly graduate students whom I trusted, so I gave them samvydav to read. But in the student audience, it was risky; I could have easily made some fatal mistakes. In sixty-five, during the advanced training courses, I remember, there was a need to retype letters from the camps on a typewriter, apparently to send them somewhere abroad. These were letters from Kandyba, Lukianenko—I remember these names, maybe there were others. Perhaps Nadiyka Svitlychna remembers more of these letters. How was it organized? Yevhen Proniuk arranged it with Nadiyka Svitlychna, and Nadiyka, I think, specifically gave me a typewriter for this. Yes, she gave me a typewriter, and I set it up at my relative Tamara Ivanova's place—on the former Maloshyianivska Street, which was later Nemirovycha-Danchenko Street, not far from the Pechersk Lavra. There I retyped these letters. It was very difficult to decipher them. They were written with a "Tma" pencil, often in very small letters, and it was quite a serious job of deciphering.

This was the first impression: you are holding in your hands documents that somehow got out of the camps, you are deciphering them, trying to improve them, to guess the meaning or connect the style—it was the first experience of working directly with those sources that came from the camps. But, upon returning to the Ternopil institute after passing my candidate exams, I did not actively distribute samvydav there, except, as I said, to my closest friends. I don't remember exactly when I applied for graduate school, but a logician from Kyiv University, with whom I communicated towards the end of my student years, wrote to me that there was a chance to get into the graduate program in logic at Kyiv University. I submitted my application. By that time, I had passed two candidate exams, and so in sixty-six I entered graduate school, albeit with some delay, because the notification of my admission to graduate school was given to me later. Maybe they were thinking something over—in any case, the department head called me in with some delay and said that there was a notification: “You have been admitted to graduate school, but you must give up your apartment.”

But by this time I had brought my mother to live with me; we lived together, my mother and I, and she was already very seriously ill. She had been gravely ill her whole life, since the war, since forty-five. And I began to hesitate about whether to go to Kyiv. My aunt was here and so was my brother, but to count on them—you know, it's always very difficult to count even on relatives in such a situation. But my mother was eager to come here, closer to her native region, because it was far away, after all. She grew up here, she was drawn here—this circumstance influenced the decision to go to Kyiv after all. We arrived, she lived for some time with my aunt Vasylina, but then, as always, a situation arose where I had to take her in. I had to rent an apartment.

I remember that I couldn't find an apartment for a long time. I found one in Nyvky, Yevhen suggested it to me, but unfortunately, it was an attic room under the roof, and it was very cold. I still have a feeling of guilt that this cold was perhaps one of the reasons her condition worsened. In any case, I had to send her to the hospital from there, and after the hospital, she did not live long. She was brought to my brother's place, and on September 6, 1968, she died there. I was already living there, taking care of her, because I couldn't entrust her to anyone. I had grown so used to her and had been taking care of her all the time, and I took it very hard, because I have special feelings associated with my mother. She was the image of a strict ethical ideal. She never fawned on any authority. There were those who, during the German occupation, tried to curry favor with the Germans to get something—some sugar, or something else. And then some tried to cozy up to the collective farm bosses. But my mother was a model of ethical independence—to save us, her children, through her labor, her fate, her suffering, and to remain ethically independent.

This happened in 1968. After that, for some time, if I'm not mistaken, I lived in a dormitory, or maybe not. But soon, since I was in graduate school, I rented an apartment together with Vadym Skurativsky. It was a place on the street that connects Shevchenko Boulevard with the former Lenin Street, now Khmelnytsky Street. Behind the opera house, the second to last one before the slope.

V.O.: I visited you there once.

V.L.: Ah, you were there once. I was also lucky in that I was in constant communication with Vadym Skurativsky, and he gave me a lot of pointers. Generally speaking, we had somewhat different approaches. I am mostly inclined to build some logical constructs and concepts, while he is a person who primarily values facts, history. He has a very tenacious memory for facts and for various sources. I remember he always tried to shake my constructions with some historical facts, or incidents. But he advised me on many things from sources, from literature, which he followed very closely and probably continues to follow for new literary works and just literature in general. His erudition is quite vast, he reads a lot, and in different fields, from philosophy to history and philology, literary criticism, journalism, and so on. He would pick out something for me, roughly guessing what I needed and knowing my preferences, and give me advice. And I am very grateful to him for advising me on many things that I found useful.

My graduate school supervisor, Pavlov, was also a special person. An ascetic, dedicated to science, kind and strict at the same time, pedantic. He is still alive. I remember his mentorship with fondness. But, to be honest, I was already secretly evolving from so-called formal mathematical logic towards philosophical logic or, let's say, towards so-called analytical philosophy, linguistic philosophy. This is linguistic philosophy and semantics. He, seeing that I had truly evolved, that my sympathies had changed and I was no longer working in formal logic, advised me to take Myroslav Volodymyrovych Popovych as my supervisor. And Popovych at that time had published his first books on semantics. And it was quite natural that I also became interested in semantics and linguistic philosophy. So, Popovych became the supervisor of my candidate's dissertation in graduate school. After finishing graduate school in 1969, I had basically completed a draft of my dissertation—which was necessary to get a job—and I tried to get a position at the Institute of Philosophy. These were complex vicissitudes.

Eventually, I was hired—with some delays—at the Institute of Philosophy. I must say that during my graduate studies, I also taught part-time at Kyiv University. The graduate school period was very intense for me. And in general, while I was teaching, I always felt anxious, because I had a sick mother on my hands and my career could be ruined because of samvydav, even though I distributed it on a limited basis then, but someone could have informed on me or at least associated me with the image of a person with nationalist inclinations or, as they said then, with elements, with the spirit of “bourgeois nationalism”—and my career could have been ruined just by that. But that didn't happen, although during my time in graduate school the tension increased because I started to get more involved in samvydav. In fact, at that time, the main work of producing and distributing samvydav in Yevhen Proniuk's group fell to me. How did I do it? I, of course, tried to act very cautiously. When I was making samvydav for Nadiyka Svitlychna, I even typed wearing rubber gloves, which I had and which I did not forget to put on, so as not to leave fingerprints. Even if the document didn't necessarily fall into their hands, it was done just in case. There was a certain meticulousness.

I also did this. I would be working in the reading room of the university's scientific library, in the building closer to Shevchenko Boulevard. At some point, I would leave my books open on my desk, take my briefcase, and go to a meeting with Mykola Khomenko. He would be coming from Kaharlyk, where he worked as a radiologist and produced photographic copies of samvydav. We would usually meet somewhere near Kozyn. I would get off the Kyiv bus, and he would get off the one coming from the opposite direction. We would meet in the forest. Getting off the bus, I would see that there was no one behind me. There were two stops near Kozyn—the first and the second. It was often at the first stop—usually, no one got off there. I would get off and walk into the forest. I would see that there was no one behind me. He would also get off the bus coming from Kaharlyk, enter the forest, and we would meet there. He would give me the copies, I would get on a bus and reappear in the reading room, where my books were lying open. But in the reading room, I also tried never to leave samvydav materials in my briefcase. I always tried to carry all samvydav materials with me.

Then they were passed on during meetings. For example, Borys Popruha, who later became the mayor of Kobeliaky, from the Poltava region, was one of the biggest radicals because he could start agitating and propagandizing on a bus that Stepan Bandera was a hero of Ukraine. I would tell him: “Listen, are you going to distribute samvydav or are you going to agitate on buses? How long will you last with this public agitation, and such a radical one at that?” Eventually, he seemed to listen. I think it wasn't easy for him to restrain himself, because he is quite emotional and quite radical in his position. But it seemed to me that he did become more cautious. I would meet with him, and he would take copies. It would be interesting to find out what he did with them. Once, after returning from imprisonment, I met him by chance, but it wasn't the time to ask questions. One student from the Ternopil Medical Institute entered the graduate program at the Kyiv Medical Institute. I valued and respected him very much—I'll remember his name later (Nestor Buchak. – V.O.). He also regularly took these materials. In addition, I distributed these materials myself directly among graduate students, except for those I suspected should not be given them. It would be interesting now to compile a list of those who were not afraid to take this literature at that time.

In graduate school, these were Mykhailo Hryhorovych, Vadym Skurativsky, Oleksandr Pohorily, Serhiy Vasyliev, and others. These were people with whom I communicated and could constantly give literature that came into my hands. And Myroslav Popovych said that one of such works got to him through someone. We made the most copies of and distributed the works of Braychevsky and Dziuba. We made some separate excerpts from Solzhenitsyn's *Cancer Ward* and other things, but much less. We distributed Sakharov, and from foreign books—Koshelivets's *History of Ukrainian Literature* and Bohdan Kravtsiv's *On the Crimson Horse of the Revolution*. *On the Crimson Horse of the Revolution* was a very good book for that time, showing the destruction of the Ukrainian intelligentsia. But it was more difficult for me to do this in a student audience. I could say things with hints—I taught logic to journalists and philologists—but to choose among the students, to intuitively guess the person…

Sometimes I liked a certain student. Once I went to one student—obviously, Vasyl Ovsienko knows him—but he recoiled when I mentioned it. But those who approached me themselves... Once a student approached me—it was Valentyn Lysytsia—but I intuitively did not accept him. He just came up and asked me if I had samvydav and if I could give it to him. When I didn't intuitively accept someone, it was impossible to distribute samvydav through that person. I don't remember how Vasyl and I got together. We probably talked about various topics. As usual, I talked with students on various topics, but not with everyone did I want to continue our communication and, say, give literature after these conversations. But here, obviously, complete trust was established, and then Vasyl took over the whole business of distributing literature in the philology department, in journalism. I think it spread to other faculties as well. This was at the university. This, of course, was also a very risky job.

And in general, it's good that he managed to act so skillfully that for, probably, two years...

V.O.: Something like that, from the beginning of sixty-nine to seventy-two.

V.L.: Yes, three years in all. To operate for three years and hold on so that they didn't get to him directly. That time, 1969-72, was already a time when they began to watch very closely. We were operating on the edge. That is, when you pass something, you have to do it in such a way that it's not obvious that it's samvydav—whether in a newspaper or a magazine. So that it's not obvious that it's some kind of exchange. In fact, samvydav was distributed through professional connections, through friendly, family connections, and that was its advantage, that it was difficult to establish. Family ties, professional ties, friendly ties—all this was intertwined, but who passed what to whom—that was difficult to monitor if it was done skillfully enough. After that came the arrests of 1972. By this time, I had already defended my candidate's dissertation and become a junior research fellow at the Institute of Philosophy. The 1972 arrests would not have directly affected me. Firstly, I was a member of the Party, had defended my candidate's dissertation, and they, even if they knew (and they did, as they had already called me in for one conversation) and had so-called operational data, which they later spoke about during the investigation, it would have been disadvantageous for them to arrest me.

They would not have wanted to touch me, as I did not belong to those who actively spoke out. The fact that in 1969 I wrote an anonymous “Letter from a Voter,” signing it “Koval,” or the facts that I edited or printed samvydav materials, were not known to them. I was then using the same apartment of Tamara Ivanova, where the typewriter was, on which I retyped some materials, for example, poems by the Dnipropetrovsk group led by Ivan Sokulsky, and other documents. The letter about the self-immolation of Jan Palach. I can't shake the impression that someone was interfering with the samvydav stream and sometimes introduced confusion into it. It seems to me that there were such attempts. In the stream of materials I had to retype, I noticed absolutely nonsensical phrases. Of course, I threw out those nonsensical phrases and made a normal text out of it. I don't think it was originally written that way. But someone was trying to turn a document into nonsense by inserting some phrases that could only compromise samvydav. I had to clean all this up and pass it on. In 1972—these things, I think, are better known—when the arrests took place, I wrote a letter of protest. By then, I, Yevhen Proniuk, and Vasyl Ovsienko were acting together. We collected—mostly Yevhen through his channels, I a little—information about the arrested. These were short biographical details, place of work, family status, illnesses, and other circumstances about each person. In addition to this, we obtained a document about the KGB investigation of Borys Kovhar...

V.O.: The letter to KGB Major Danylenko.

V.L.: Yes. We formatted it as an issue of the *Ukrainian Herald*. I don't know its fate—at least I had no data on whether this *Ukrainian Herald* was passed on anywhere.

The plan was that this letter of protest of mine would also go into this *Ukrainian Herald*. It wasn't included because I was late with its preparation. But I wrote the letter. I saw that it was virtually impossible to avoid arrest. I remember our meeting with Vasyl, where I told him to step aside for a while and that we shouldn't meet, because when I submitted the letter, they would be watching me and might arrest him. After the arrest (July 6, 1972. – V.O.), a long investigation began. I must say that the investigation itself was quite hard on me. Hard why—firstly, because of my neuro-psychological state, because I started to develop some kind of nervous disorder, a sensitivity to sounds. I think they may have intentionally developed and maintained this disorder, when the state of the nervous system becomes very severe. It's a kind of continuous pain that resembles a toothache. When I said that stones are falling, shots are ringing out in there—I don't know if they used tape recordings or what—they didn't react, and the doctor said: “That’s just your type of nervous system.”

By the end of the investigation, I was terrorized beyond belief. My nervous system completely gave out; it was tough. And then the second circumstance—I was worried about all the people around me. This involvement of relatives, the community, these women, children—I was terribly worried about how things would turn out. My goal was that whatever we said, it should only be to close the circle of people in the investigation to Vasyl, me, and Yevhen. When Vasyl was arrested and joined us, there were three of us. And if we could manage to cut off everyone else, that would be wonderful. Everything else—say, the evidence against us—that interested me little; the only thing needed was to close this case as much as possible. Our fate was already decided anyway, because we, of course, had to receive our sentences. I arrived at the camp, of course, in bad shape, almost on the verge of complete nervous exhaustion.

I wanted to get out of that solitary cell, to finally be in the camp where I wasn't constrained by a wall, where they didn't plant currency speculators, as they called themselves, who would unexpectedly clap their hands with all their might, and I would flinch all over, because my nervous system couldn't take it anymore. Of course, physical pain is one thing, moral suffering is another. And when people now tell me: you know, you didn't behave very well during the investigation, because you talked about each other—in that respect, I am morally completely at peace. We did our job, we dared to do what we did then, and during the investigation, we held out as best we could. And whoever is now capable of casting a reproach or a stone at us—it doesn't bother me. Back then, it was important to go, and we expected that the movement would expand, that meeting people from the KGB was a way of overcoming fear. And it should not be avoided. This was not a deep underground—it was, on the contrary, a semi-legal affair. You have to prove you are right and overcome fear.

Some reproached us for being too deeply conspiratorial—that's not entirely true. We distributed samvydav at our workplaces. It's another matter that many people were afraid; there were very few people who overcame their fear to join this cause and expand it to awaken national self-awareness, to form a personality that overcomes fear, that, in fact, becomes a personality, that resists conformism. It was truly the formation of national self-awareness. This work, this reformation movement did not become a mass movement then; a large mass of people did not join it for Ukraine to arise from below as self-aware and national. This work must be done now, and unfortunately, it is not always done well now, because there is too much reliance on declarations. At the time when we communicated, we discussed ideas, it was an intellectual communication.

When I communicated with Svitlychny or others, it was a wide circle of ideas, it was some kind of cultural and intellectual movement, it was a worldview exchange of ideas, a completely different atmosphere compared to when you communicate with parties now and they offer you just plain, banal declarations. It's not the same atmosphere. We had a cultural movement. Now, I think, the problems of the national movement are again tied to the same thing—to a deeper cultural and philosophical foundation, to the philosophy of culture, to the appreciation of cultural worlds and original culture, to leading people into the temple of this original culture. These are purely intellectual aspirations that will interest young people, not banal patriotic declarations that do not replace intellectual culture. But that's a digression. In the camps, they repeatedly threw me into the ShIZO—the punishment cells.

The most common accusation was that I refused to work or that I did not meet the production quota. The wording was usually that I refused to work. And I repeat now that it was often provoked, because they would start picking on me. It must be said that we still have not properly analyzed that time and those events. There were certain individual approaches to everyone—I observed this. When some now describe those times as if everything was very simple and the mechanics of pressure were simple—I do not think so. It still needs to be re-analyzed, what methods they used to try to break people. Even if you were right next to me, it was often unnoticeable to you what they were doing to me or what might await me. For example, they might bring you together with me, give me a parcel, and you would go around telling people: “He's living so well!” You spread the word that “he gets parcels,” and meanwhile they take me away from you and throw me into the ShIZO or somewhere else and start beating me or doing something else. In short, I do not think that the picture of psychological and physical pressure is as simple as it sometimes appears from the stories. I believe the KGB's mechanics were more complex.

For about half of my term, I paced from corner to corner in the punishment cell. I was often thrown in there when it was cold. I would sleep on those plank beds—without any bedding. I don't know how long I could stand it—maybe two hours, maybe an hour and a half, maybe an hour, and then I would start walking, doing various exercises, until I warmed up. Once I warmed up, I could sleep for another hour or so, and then I would get up again and walk until I fell asleep on my feet. Eventually, Yevhen and I somehow managed to pull through—our seven-year prison term ended, and it so happened that we met in the same vehicle when we were being sent to exile.

V.O.: Was this in the Urals?

V.L.: In the Urals, yes. It was a great joy, of course. And then our paths to exile diverged: he went to Shevchenko's places beyond the Caspian Sea, and I to Transbaikalia. In exile, they continued to terrorize me with the same things. I come to work—there's no lathe. This was at an auto repair plant in Nova Bryan. It's a settlement in Transbaikalia, in the Buryat ASSR. Well, I say: “How can I work here?” “I don't know.” Fine, I walk around the workshop... Then I went home. After a while, they accuse me of not working. What can I say in response? They formulate an accusation of parasitism and throw me into a so-called “pressure cell,” as Oleksandr Bolonkin, who was also serving his exile there and later published an article in the magazine *Ogonyok* about his stay in the Ulan-Ude prison in this so-called pressure cell, called it. Here, in addition to psychological and all sorts of other methods, they use physical ones. That is, various methods of beating. I must say that it was still not the kind of beating as in the thirties, that is, brutal and aimed at killing a person.

There was a sense of some correction. For example, every day one or two criminal inmates (because it was a camp for criminal offenders) would approach me and always hit me in the same spot—right here or somewhere here. Only once, I remember, I somehow approached the window—it seemed they called my name, that I had some parcel, so I wanted to get the parcel at the window, but then an inmate attacked me and hit me in the liver, here, there, and I fell. But otherwise, they beat me methodically, just to inflict pain—you already have bruises here, and they continue to hit the same spot. I say to him: “What's the interest for you in hitting me?” That investigation ended, and before the trial, I had to undergo a medical examination. The doctor examines me. I undressed—bruises here. The poor woman, I see, started to cry, but she probably couldn't say anything, as she was clearly completely controlled by the KGB. After some time, a trial takes place, and they give me one year. But what's characteristic is that when the court session began (my wife came to the trial), the first question was how I felt about my previous charge and whether I admitted my guilt. This was a continuation of the same pressure to make me admit guilt. Because they had met with me earlier, in the camps, and almost in a friendly way said: you write a renunciation of your beliefs today, admit your mistakes—tomorrow you go home. I think they even said they would drive me. So this was the final push. But then they gave up on it—they saw that it was a hopeless case.

I served an additional year in the camps on top of my exile. Then my wife came with the children, and we lived in the settlement of Iltsí (pos. Ilká). I worked as a lathe operator at an auto repair plant; the workers treated me well, the pressure stopped, and I worked peacefully at the lathe until the end. We bought an old little house there, fixed it up. They say it was built by Lithuanian exiles. The children went to school there, and they were treated well there too. It was a Russian school, of course, no Buryat language—it wasn't even studied there, although Buryats live there. In 1983 we returned to Kyiv. And new ordeals with work began. Eventually, I wrote a statement to the KGB, saying that I was again facing a fact, because the police had already come, and I felt that they could charge me under the second part of the article on parasitism. Only then, with their assistance, on instructions from the KGB, was I placed at the Museum of the History of Kyiv, where I worked from 1983 to 1987.

In 1987, I returned to the school I had graduated from. My wife and I decided to buy a house there. Besides, the salary at the museum was very low, and at the school, it was higher. We had to support the family somehow. And so we bought a small clay house there, repaired it, and now we use it as a dacha. I worked for two years at this Velykodmytrivska school, which I had once graduated from. Of course, they welcomed me gladly, because they still remembered me and were concerned about my fate. The principal even supported me during the reinstatement of my candidate's dissertation, speaking at the academic council meeting in Kyiv when the issue of returning my academic degree was being decided. They had stripped me of my academic degree, and it was returned in the same way, through the VAK in Moscow. After my academic degree was reinstated, I was reinstated and now I work in the Department of the History of Ukrainian Philosophy, where I worked before.

Now I am the head of this department. But things in these research institutes with these salaries are bad, getting worse and worse, and I wonder what will happen to these research institutes. Young people are leaving these institutes. But those are other, modern problems. That's briefly all I could tell you in this time. V. Kipiani: Please say a few words about your wife and children.

V.L.: My wife, too, throughout this whole time, during all these periods I have briefly described, was subjected to persecution. We got married when I was finishing graduate school, in 1969, and had just started as a junior research fellow at the Institute of Philosophy. We got married then, and since that time she has shared all my anxieties, all the tensions of my life. Firstly, after my arrest, she was fired from her job. She worked at the UNDIPi (Ukrainian Scientific-Research Institute of Pedagogy. – V.O.) as a lab assistant, was pregnant, and they wanted to fire her immediately. And then they did fire her. She got by with odd jobs; some people here helped her out, gave her work to do at home. She was supporting two children. My son Oksen was born after my imprisonment. She raised two children, and when I was in exile, we solved all these life problems together. It was easier together; for her alone, of course, it was much harder. But she became actively involved in the work of the Solzhenitsyn Foundation, and they began to persecute her, summon her to the KGB.

Even when we returned from exile, they still tried to summon her and threaten that they could open a case against her for this. And such cases were opened back then. But this was already 1983, the USSR was moving towards perestroika, and they obviously saw that times had changed, and it stopped. Of course, Vira Pavlivna, my wife, was very worried. She loved teaching in school, and she too cultivated national self-awareness in her Ukrainian literature lessons. Many of her former students remember her well and are grateful for her lessons. Some people of other nationalities—Russians, Jews—were imbued with her rightness in valuing distinct cultures. She taught this. For example, her student Alakan and her husband became ethnographers and emigrated to the USA. They correspond with Vira, writing wonderful letters. She is Jewish, he is also Jewish, but they became imbued with an appreciation for their own distinct Jewish culture, education, and Jewish national self-awareness under the influence of her lessons in Ukrainian language and literature, the parallels between the fates of Israel and Ukraine, and the fact that my wife emphasized the value of the temple of an original culture, which must not be destroyed and must not be absorbed by another culture, that the dignity of any culture lies not in expansion in space, but that culture itself is the main value.

It seems to me that this philosophy is now effectively lost. The conversation about this is not happening—everything is based on some general declarations. But declarations are not enough. When I talk to young people now (I lecture at the Institute of Linguistics and Law), I feel that they understand precisely this kind of language, when you open up for them the horizons of thought and those values that we must protect. That we must preserve not only the diverse biological world, but also original cultures. This is very important now, I think. That is, what do I want to say? That the modern formation and spread of national self-awareness must be based on the philosophy of culture, on a deeper intellectual foundation, without which only some simple declarations remain. So, my wife knew how to do this; she knew how to awaken the national self-awareness of children in her lessons by introducing customs, by opening up the world of ethnoculture.

Of course, there were more conscious children who preserved this. From time to time, they meet somewhere and communicate with her, remembering and being grateful to her for this very thing. So we had common lines of activity. That, in brief, is about my wife. And that student from Ternopil who entered graduate school in Kyiv—that was Nestor Buchak, an exceptionally fine, ethical person. He was a wonderful young man. He later married, and his wife is just as wonderful. He took samvydav from me when he was a graduate student at the medical institute, distributed it in his circle and, I think, in the circle of doctors.

V.O.: And I also wanted to ask you: what was your mother's name? It would be good to name her maiden name as well.

V.L.: In the village, she was called Priska, but in her passport, she was registered as Yefrosynia.

V.O.: Like my mother? Only my mother was called Frosyna. Although we also have that variant.

V.L.: Yes, there is such a variant, and my mother was called Priska. And my father's name was Semen, Semen Petrovych. Because our grandfather was Petro; I still remember my grandfather. But I don't remember my grandmother.

V.O.: And your sisters? You sometimes named them, and sometimes not.

V.L.: I had three brothers: Petro Lisovyi, the one who was in Germany, he was the eldest.

V.O.: What year was he born?

V.L.: Born in twenty-three. And then Pavlo Lisovyi, who worked as a driver here in Kyiv. Mom lived with him for a while and died in his apartment. Then Fedir Lisovyi. And I was the youngest among the brothers.

V.O.: You were born in thirty-seven?

V.L.: Yes, I was born in thirty-seven.

V.O.: On May seventeenth?

V.L.: That date does not correspond to my actual birthday. Why—because the documents in the village council were lost, and then, when they issued us birth certificates, they just made up the dates. They made up dates for many people like that. In fact, I was born at the end of August, before the First Feast of the Theotokos. That's what my mother remembered. And those documents and records burned during the war.

After the war, they were reissued, and the dates were set arbitrarily. They did it completely irresponsibly, setting dates without asking the parents. I don't publicize this much, but that's the actual state of affairs with my birthday.

V.O.: And the names of your sisters?

V.L.: I had two younger sisters—Halya and Luba. Halya died during the war when she was still little, at about three years old. And Luba—I have one sister—lives in Kyiv, married an engineer, a lecturer at the Polytechnic Institute. They lived a very good life, though not without complications that I would rather not talk about. Her husband, Stepanov, a Russian who knew how to be tolerant of everything Ukrainian, died recently. And they raised their daughter to be patriotic. She is the wife of Father Andriy, who serves in the church near the museum. For a time, she was a *panimatka* (priest's wife), worked in the church. So I'll reveal a secret: I have a priest in my family, among my closest relatives.

Of course, my sister lived a life of hard work. She worked at a shoe factory. From our family, only I received a higher education; all the others did not manage to. Life was hard. Especially for Fedir, who followed the path of those young men who, out of desperation in the village, began to sign up for recruitment to escape that collective farm. And once they went on those recruitment drives, it was for a long time... He was first recruited to the Urals, then moved to the open-pit mines in the Caucasus. He was injured there—some kind of charge or detonator exploded in his hands, and his fingers were blown off. Although he had already lost some during the war, though that was his fault—he was fiddling with some detonator. And in the Caucasus, even more were blown off. That, in essence, is all about my relatives. Today is October ninth, 1998; the video recording was made in my apartment in Kyiv in the presence of Vasyl Ovsienko and Vakhtang Kipiani. Thank you for the video filming and tape recording. It's very good that we did this.

V.O.: Thank you.