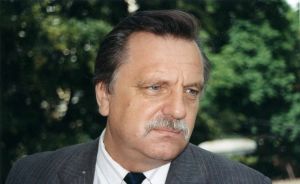

I n t e r v i e w with Mykola Andriyovych H o r b a l

(Last corrected on January 7, 2008)

V.V. Ovsiyenko: On July 17, 1998, in the home of Mykola Horbal, Vasyl Ovsiyenko is conducting this interview with him. Please, begin.

M.A. Horbal: Vasyl, when these things are recorded, it’s obviously for a reason. Perhaps it’s necessary. I’m holding this short biographical note you wrote about me, and I must say it contains many inaccuracies.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: They need to be corrected.

M.A. Horbal: Obviously. So I will start with it. First, let’s clarify my date of birth. I was born in Lemkivshchyna. I’m holding a certificate from the Ministry of Labor of Ukraine—it turns out that documents on resettled people are now kept only in this Ministry. It states: “In 1944-46, based on the agreement between the Ukrainian SSR and the Polish Committee of National Liberation of September 9, 1944, a resettlement of citizens from Poland to the territory of the Ukrainian SSR was carried out. The family lists of resettlers from Poland to the Ukrainian SSR for the village of Volovets, Horlytsi County, include the family of Andriy Hnatovych Horbal, composed as follows: Andriy Hnatovych Horbal, born 1898—head of the family; Teklia Mykolaivna Horbal, born 1906—wife; Maria Andriivna Horbal, born 1928—daughter; Olena Andriivna Horbal, born 1932—daughter; Bohdan Andriyovych Horbal, born 1937—son; Mykola Andriyovych Horbal, born 1940—son. Place of birth—the village of Volovets, Poland. Date of preparation of the family lists—February 8, 1946.”

V.V. Ovsiyenko: A Polish document?

M.A. Horbal: No, I think it was prepared by a special deportation authority that operated under the aegis of the NKVD. You see, this paper is dated 1946, but we were deported in ’45. So, this was the only document for all family members. Now, I am officially listed everywhere as having been born in 1941. When I received this list, I asked my sister at home if it was true that I was born in 1940, as indicated here. My sister confirmed it. During those hard times, when we were resettled, we had no documents with us, only this list, and even that was lost when our house burned down here in Ukraine, in the Ternopilshchyna region. When I needed to go to the 8th grade after seven years of school, they required a birth certificate, which was issued to resettlers by the local ZAGS [Civil Registry Office] based on a parental statement. Apparently, my father decided then that I should be six months younger. (I was born on September 10, 1940; according to the ZAGS certificate—May 6, 1941).

What was the motivation for this? My sister later said: “We were so unfortunate, exhausted by the war, resettlements, wanderings, and hunger, that Father thought, let him be a year younger—he’ll grow a bit more by the time they draft him into the army.” Now, because of that, I’ll retire a year later.

So, I corrected one mistake, because I knew for sure I was born on September 10, and I always said the tenth, but my passport said May 6. But it was impossible to correct the year. How could I? I celebrated my birthday on the old date but wrote it as it was in the certificate of birth, according to my father’s statement. Such an inaccuracy. Obviously, when I have to write some biographical note about myself someday, I will write it as it was.

So, I was born in 1940, on the night of September 9-10, in the village of Volovets, Horlytsi County—that was Kraków Voivodeship in Lemkivshchyna. This is one of the westernmost parts of the Ukrainian Carpathians, not far from the village of Krynytsia—a famous resort with mineral waters. There was not a single Polish family in our village; it was a purely Ukrainian village.

Obviously, I should tell you a little about my father and my family. Vasyl, I’ll show you my father’s education certificates and his diploma from the cantor’s institute. (He takes out a large book with leather covers, which contains his father’s certificates. – V.O.) This book, a Psalter, is one of my relics that went through all the resettlements with us. Dad brought it from America at one time; his uncle (mother’s brother – V.O.) gave it to him.

All the Horbals come from the village of Bortne, which is next to the village of Volovets—the same Bortne from which the family of the composer Dmytro Bortniansky originates. It was a well-known, nationally conscious village. It so happened—but that’s a separate topic—that during the First World War, Lemkivshchyna, like all of Western Ukraine, was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was at war with Russia at the time. I must admit that we had very strong Russophile tendencies (and they existed in Lviv, as in Galicia in general), but while in Galicia the intelligentsia slowly began to distinguish between the concepts of “Ruthenian” and “Muscovite” and to embrace the new concepts of “Ukrainian” and “Ukrainianness,” in Lemkivshchyna, unfortunately, these processes occurred much more slowly. And the imperial Russian structures indeed supported Russophile tendencies in every way in Galicia, to which Lemkivshchyna also belonged.

The Austrian government couldn't figure it out: part of their state’s citizens called themselves “we are Ruski,” “we are Rusyns.” (The word “Lemko” at that time was more of an external nickname, and the Lemkos themselves did not call themselves that at the beginning of the twentieth century). For the Austrians, who were at war with Russia, this segment of the population, which clearly sympathized with their enemy, was not unreasonably regarded as a Muscovite agency, so quite a few Lemko intellectuals were arrested and imprisoned in the Thalerhof camp. Many of them perished there. In the village of Bortne (I recently visited that village), there is a cross. “In memory of the victims of Thalerhof. Grateful residents of Bortne in honor of the Russian idea,” reads the inscription. The poor Lemkos could not figure out that the Muscovite State, which took the name Russia under Peter the Great, and their Ruthenian identity were not identical concepts. And the Muscovites exploited this.

This Psalter was a gift to my father from his uncle, who had invited him to America. I opened this Psalter and read on the last page: “To the glory of the One-in-Essence, Life-Giving, Indivisible Lord the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, in the reign of the most pious autocrat, our great lord Emperor Nicholas Alexandrovich of all Russia, and his spouse, the most pious lady Empress Elizaveta,” and so on. Our Lemkos, even over there in America, were praying for the Tsar-batiushka. Or more accurately, such spiritual literature was published there, obviously with Muscovite money.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: What year is it from? The date is written in Cyrillic letters. One needs to know them…

M.A. Horbal: I can't say for sure. But that's not the point. In 1927, there wasn't a single Orthodox church in Lemkivshchyna. It was a region of the Greek Catholic Church. But then a transition to Orthodoxy began. In my village, they built a new church. I never had a conversation about this with my dad; I was a boy—it wasn’t the time for it, and then my father passed away; he died in 1961. I terribly regret that I didn't ask him so many things! My father was the firstborn in his family. My grandfather died when my father was eleven, and a stepfather came—Dziubyna: my grandmother remarried. Since my father was the eldest, the greatest burden of the household fell on him. For some reason, he didn't have a good relationship with his stepfather, and he ran away from home as a minor. For a while, he was a servant at the cantor’s institute in Przemyśl. It’s noted here somewhere—he was like a ward, then he was admitted to this institute.

But that's not what I wanted to say. Here is my father's certificate...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: It says here: “a student of the cantor’s institute”...

M.A. Horbal: “A student,” he was a ward later. And this is a school report: “Andriy Horbal, born March 10, 1898, in the village of Volivtsi, of the Catholic faith, Greek rite, began his schooling in the year 1906-1907, has been attending the local school since September 1, 1906.” And here are his grades: “Conduct—satisfactory, second semester—commendable, diligence—satisfactory, in studies and religion—very good, in reading—very good, in writing—very good, in the Ruthenian language (obviously, Ukrainian)—very good, in the Polish language—very good, in arithmetic combined with the science of geometry and forms—very good, in knowledge of history and nature—good, in drawing—very good, in singing—very good.”

By this I want to say that the village of Volovets, Horlytsi County, Kraków Voivodeship, was a Ukrainian village; you see the language this certificate is written in. The village had a school, it had its own kindergarten. And if today the question arises as to what kind of territory this was, this document, dated 1907, testifies...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: 1911.

M.A. Horbal: Excuse me—eleven. Issued to my father after he finished school. Things like that.

In 1925, my father graduated from the institute in Przemyśl. Obviously, Przemyśl at that time was a center of Ukrainian culture not only in the San region and Lemkivshchyna, but also in Galicia as a whole. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Przemyśl had become a kind of center of the Ukrainian renaissance. It was in such an environment that the consciousness of a boy from Lemkivshchyna—Andriy Horbal—was formed. Unfortunately, when he returned to the village as a specialist, almost the entire village was already attending a different church, not of the confession to which my father belonged. In my village—I asked my aunt—only three or four families remained, as a rule, the village intelligentsia, teachers, who still went to the Greek Catholic church, while the rest of the peasants built a new church for themselves—an Orthodox one. They brought in a *batiushka*, as the Lemkos call him, for it.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: A *batiushka*?

M.A. Horbal: A *batiushka*. In the Lemko dialect, the stress is fixed, always on the penultimate syllable, so it’s *batiushka*, not *batyushka*. I ask my father's sister, Aunt Maria, how she converted to Muscovite Orthodoxy: “Why a Muscovite *batiushka*?”

– “Well, our men say that some *batiushka* came from somewhere (a refugee from Russia, which by that time was under the Bolsheviks – M.H.) and is calling on everyone to convert to Orthodoxy, because it is ‘our firm faith.’”

How were the Lemkos to understand that Greek Catholics are the same Orthodox, just oriented towards Rome and not Moscow? In a Polish environment, such a step by the Lemkos (coming under Muscovite jurisdiction) even looked like a kind of resistance, a manifestation of patriotism. They were not yet oriented in the political processes, that Ukraine was forming in opposition to the Russian Empire, but, being in a Polish environment, they were searching for their own identity, sincerely believing that Lemko-Rusyn and Russia were identical concepts. A huge mass of people was deluded by this.

Why am I bringing this up? The resettlement that began in 1945 was (according to documents) a “voluntary exchange of population”: from here, from Galicia, from Volhynia, Poles were leaving for Poland, and from Lemkivshchyna, Kholmshchyna, the San region, and Podlachia, the Ukrainian population was being deported. 480,000, almost half a million Ukrainians, moved to the Ukrainian SSR.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Was this not connected to the national resistance?

M.A. Horbal: To a large extent, yes! Moscow was ready to give up this territory, although Khrushchev—there are documents—wrote that this territory (Kholmshchyna, the San region, Lemkivshchyna) should be annexed to the Ukrainian SSR because it is Ukrainian territory. But Moscow refused. It gave it to the Poles on the condition that this would knock the ground out from under the armed resistance. And so it was, because this was the region of Polissia, the Carpathians, where UPA detachments were actively operating. Our population, for the most part, supported this armed resistance.

I must admit that on the Polish side, the authorities were also interested in driving the Ukrainians out of there. There were numerous cases where armed Polish detachments massacred entire Ukrainian villages. People were forced to flee for their lives. So really, can such a departure be called voluntary? I later asked my mother how it happened that we left. “Well,” she says, “some military men came and said we had to leave. People didn't want to go, many didn't want to. We had lived there as long as we could remember, our great-grandfathers’ and grandfathers’ graves were there—but we had to leave it all behind.”

My father was among those who did not want to leave, but I must say that even my grandmother said: “Let’s go to Russia, because we are Ruski.” She was a convinced Russophile. When we were traveling through the Lviv region, my father said: “People, let’s stop here, there are empty villages here—a place to live, our people are here,” but his mother categorically objected: “No, we won't stay here, we are Ruski, let’s go to Russia!” And they arrived in the Kharkiv region—they weren’t allowed to go further, of course, because resettlement was only within the Ukrainian SSR. They settled in the Kharkiv region. However, half a year of that collective farm and that “Russia” was enough for our Lemkos to harness their horses and, by their own means, travel across the whole of Ukraine “back home”—and they ended up right at the border, in the Sambir region; they weren't allowed any further “home.” My entire family, the families of my uncles, whom we call *stryikos* (father's brothers), are still there today, in the Sambir region. And since my father was an intellectual, had no horses or wagon, he sold all the furniture for a train ticket. It was only enough to get to the Ternopilshchyna region. There was some family on my mother’s side here. We arrived in the village of Letyache after the harvest in 1947 and settled there. I won't recount our whole odyssey—I always say that after the deportation, we settled in the Ternopilshchyna region. Although by the time we got here, it was already 1947, and we were deported from Lemkivshchyna in the spring of 1945.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And those *stryikos*—did they want to go back to Lemkivshchyna?

M.A. Horbal: Obviously, but no one was allowed into Poland anymore—the border. Many people who were deported to the Odesa, Donetsk, and Dnipropetrovsk regions fled back. At one time, they believed that “there are beautiful lands there, people live joyfully all together in collective farms,” and so on. In Lemkivshchyna, the land is mountainous; you can't get very far on those stones. They sowed oats because wheat didn't grow well there, so they really lived hard. And they remembered from the First World War, when the Russian army came—they were uhlans, well-dressed, on fine large horses. My grandmother used to say that they would sometimes be given bread from the military field kitchen, white wheat bread. She would say: “My God, that bread is like the sun.” And here an NKVD officer is telling them: “We all live together, all the orchards are ours, the fields are ours, we grow things, then we share everything together, there are bees, they give honey.” I remembered that “honey.” Grandma says: “Let’s go there, they give honey there.” So when I was imprisoned, I wrote a letter to my uncle from Mordovia. Because he was surprised: I was a teacher and had some success, although we lived separately, me in Ternopilshchyna and them in the Drohobych region—“What happened to Mykola, why is he suddenly in prison?” So I wrote to them: “Uncle, so that a Lemko wouldn't complain too much, ‘where’s that honey?’, they gave him a bit of honey.” So that I wouldn’t complain too much about where the honey was, they gave me a bit of it. So now I’m eating that honey in Mordovia. Such is the irony of fate.

And Operation Vistula? That was a completely different action, because those Ukrainians who managed to remain in Poland, the Polish government, now as its own citizens (just of Ukrainian nationality), deported them to the western territories of Poland, the so-called “ziemie odzyskane,” lands that had become the property of Poland from Germany during the post-war redrawing of borders in Europe. This was a truly criminal action. Because we could at least gather, pack our things, could refuse to go, could demand something, could take property with us, including livestock and equipment, while they were given two hours to gather their bundles—and this population was scattered, one or two families at a time, into a Polish environment for complete assimilation. The intelligentsia was arrested and thrown into the concentration camp in Jaworzno. That was Operation Vistula.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And in terms of time, how would you mark this? Your resettlement was in 1945, but what month?

M.A. Horbal: In the spring of 1945.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And Operation Vistula?

M.A. Horbal: Operation Vistula was also in the spring, at Easter, but that was 1947, two years later. It lasted exactly two months. That is, the Poles did it all very quickly, because the troops came in and deported them. There were, in fact, two actions to destroy Ukrainian identity in Poland—in 1945-46 and 1947. I was recently in the village where I was born...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Does the village still exist?

M.A. Horbal: Yes. Four or five families who returned from western Poland live there, but there are also two Polish families now. They showed me the place where our house was. It’s overgrown with weeds, but you can see that there were foundations there. It was a new house, made of brick. As a rule, Lemkos built wooden houses, but my father, having returned from working in America, had a little money. It was large, had four rooms and a kitchen. It was already in a new European style.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: When was the house built?

M.A. Horbal: Actually, it wasn't completely finished; one of the rooms didn't even have a floor yet when they started deporting us.

After graduating from the cantor’s institute, my father was assigned to work in the small town of Wola Michowa. He was a cantor, a choir conductor, and he also worked part-time as a forester.

There he met my mother—a young girl, eight years his junior. They got married, and my two sisters were born there. Their firstborn, Dmytryk, died as an infant. So when Bohdan was born—he was already the fourth child—and he also fell ill, my mother was terribly worried. I describe this in my essay about Bohdan, “Bohdan—My Brother.” They applied leeches to him, and perhaps after that, he barely breathed for about six months. My mother carried him in her arms; the child was neither living nor dying. Then there was a developmental delay; his teeth started to grow in at the same time as mine, and I was three years younger. Obviously, this affected his overall development and his mental state. Such was Bohdan’s fate.

So we arrived in the village of Letyache in 1947. That same year, I went to first grade.

In 1957 I finished ten-year school. When I applied to the music department of the Chortkiv Pedagogical College, I failed the exams. For several years I worked in my “native” collective farm in a road crew—breaking stones on the road with a hammer, crushing them into gravel.

In 1960 I finally got into the music and pedagogical department. I graduated in 1963. What’s interesting is that I only picked up a violin at about sixteen—it was my father’s violin, which he had brought from America. But a Lemko acquaintance of ours borrowed it from my father and played it at weddings. My father only took the violin back from him when I said I wanted to apply to the music department. So at the time of my admission to the college, my command of the instrument was not very high. Under such circumstances, I could no longer have great achievements as a violinist. You have to play the violin from a young age. Although in college, I was an above-average student.

Later, at work, after graduating from college, the artistic ensembles I created stood out for their novelty—breaking the stale stereotypes of Soviet pop music, I had some success. In the town of Borshchiv, I organized a children's ensemble—a song and dance group, which was recognized at the regional review in its second year.

I unleashed children's creativity and clearly went beyond the bounds of Soviet music-making. We went beyond that accordion; I managed to secure funding through the district department of public education—they believed in me there—and purchase good-quality pop music instruments: an electric guitar, a Czech double bass, a saxophone, a trumpet, a xylophone, and drums. That was the children's musical accompaniment for the ensemble. I won't even mention that I had no problems with the vocal groups. The dance groups were led by a good young ballet master. We created an interesting children's collective called “Sontse” (The Sun). Most of the songs were my own.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: “Sontse” or “Sonechko”?

M.A. Horbal: “Sontse.” There was also a younger group called “Sonechko” (Little Sun), but the song and dance ensemble was called “Sontse.” There were two vocal groups—an older and a younger one, a dance group, and an instrumental group. Obviously, the kind of repertoire I wanted was not in all the repertoire collections of that time. This prompted me to write myself. I knew what I wanted, so why should I go around searching when I could do something myself? That's how I became a composer—the times simply prompted it. The district youth teachers' ensemble I created, “Podolyanochka,” was an emphatically national group. I somehow spontaneously entered the renaissance of the Sixtiers.

Then, in the 60s—that was Oles Honchar’s “The Cathedral,” Romana Ivanychuk’s “Malvy,” the poetry of Lina Kostenko, Vasyl Symonenko, even some samizdat reached Borshchiv. Oh, I was simply inspired then! I was on close terms with Volodymyr Ivasyuk. The boys from my orchestra, schoolchildren, entered the university in Chernivtsi, and they played in Ivasyuk’s first orchestra. Ivasyuk would come to visit me; we talked, consulted. Perhaps I was one of the first to hear his “Chervona Ruta,” which had not yet been published. But that's by the way. I'm talking about that time and the environment in which I created. It gave me a certain confidence. I allowed myself to joke, to mock the Komsomol when I went to the district Komsomol committee—and there were those worthless officials... Well, my position, my independence, obviously irritated them, but since my ensembles brought honor to the district, they tolerated it. As it turned out later—for a time...

In 1967, I enrolled in the Kamianets-Podilskyi Pedagogical Institute. Why Kamianets-Podilskyi? Because they had opened a new faculty at the pedagogical institute—music and pedagogy. In the summer, I rode my motorcycle there a few times and passed the exams. They accepted me. It was a shame to leave Borshchiv, my ensembles, but the institute only had a full-time program. I studied full-time for a year, but I would travel to Borshchiv for rehearsals because it was also a way to earn extra money. Then I transferred to the correspondence program in Ivano-Frankivsk and returned to work in Borshchiv. At the Borshchiv College of Agricultural Mechanization, they introduced a subject called aesthetics. It turns out they had introduced this subject in all technical schools. It was a new trend.

Since I was involved in art and music, they invited me to teach this subject. I gladly agreed, even though there were no textbooks for this subject yet. I even took advantage of this opportunity: I had a pile of poetry books, patriotic prose, so wasn't there something to talk about with these young men? I also went there with another goal—to create a powerful male choir: a thousand full-time students—as a rule, boys from villages, usually after military service, usually with strong voices. Moreover, in Borshchiv, there was a choir at the House of Culture that had the title of a people’s choir. Most of the members of that choir were teachers from that college. The foundation was already there, as most of the teachers were already singing and had professional academic singing skills. It was impossible not to gather a hundred singing lads from a thousand students. True, I was overloaded with hours of aesthetics—many groups. But it was a joy for me; I had things to say about poetry, painting, and the new trends in Ukraine.

They became interested in me as a teacher. They proposed that I conduct an open demonstration lesson in aesthetics for teachers of this subject from the entire Ternopil region.

I felt uninhibited. After all, one must teach these boys, who would soon become tractor drivers and mechanics, that besides this, there are some higher values, a spiritual life!

I had no idea that all those who came to the open lesson were KGB men.

Just a few days later, they arranged another “open lesson” for me. A telegram arrived: I was being summoned to a seminar for aesthetics teachers in Ternopil. It turned out they had summoned me to “tie me up.”

During the search, they seized my poem “Duma.” My songs, although completely devoid of Soviet patriotism, were not such that they could be used in an accusation as anti-Soviet. They were emphatically Ukrainian songs, works with a pronounced civic position, but in my opinion, there was nothing to find fault with. Well, the poem “Duma” was obviously an anti-Soviet work. I later realized that they had been following me for about six months, that they already knew about “Duma,” that it had already been reported. I’ll show you this work later; I have it.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Do you have the manuscript?

M.A. Horbal: I have the manuscript; the SBU returned it to me. And so it happened, Vasyl, that I ended up in Mordovia.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Just specify the dates.

M.A. Horbal: I think it was around the 17th or 18th (of November 1970. – V.O.) that I went to Ternopil for that “seminar.” Suddenly in Ternopil, there were an awful lot of friends from college whom I hadn't seen for three or four years. One after another, we'd meet, go to a café... Obviously, these were scenarios developed by the KGB to dig up something else, to get some more information, maybe I would offer them something, maybe I would “blurt out” something else at the last minute. It was important for them to find out if I was forming some group, some organization. Later, when I was in the camp, I remembered that friends had come to me several times: would I like to have a typeface, to print something, because there was such an opportunity at a printing house... A few days before I was to be taken, a friend of mine from the music school came up and asked if I wanted to buy ten volumes of Hrushevsky. They needed materials to confiscate, because they knew everything I had, they had rummaged through my things when I wasn't home, it wasn't a problem for them to rummage through my belongings. I ask: “How much?” He offered ten volumes of Hrushevsky for a very affordable price. Something made me suspicious—I refused.

So they were very actively working on all fronts with those “friends” to get more episodes for the accusation. That day in Ternopil, I “accidentally” met another friend; he had graduated from the same college three years earlier and was in charge of amateur arts at the cotton mill in Ternopil. I tell him: “They summoned me to a seminar, I went to the cooperative college—no seminar, to another college—also no. And he says: “What's with that seminar? You'll go tomorrow. Maybe it will be at the music college. Come stay the night at my place, and tomorrow you'll go to the music college.” So I spent the night at his place. We even went to a restaurant, and some friends met us there, told various anecdotes... The next day he says: “Mykola, there's the music college, you go that way, and I have to go this way.” I just turned away from him, he had maybe walked 50 meters from me—and then some guys grabbed me, twisted my arms, and threw me into a car. I didn't even realize what had happened. There were some rumors going around at the time that people were being kidnapped, their blood was being drained, something like that. My first thought was—bandits. The car sped off, turned around near the department store and went uphill, and it was about 150 meters from the KGB building. We drove up—“Get out. See where you are?” I see—the Committee for State Security. “Get in!” And so it began.

As a legal ignoramus at the time, I didn't yet know that they only had the right to detain someone for three days, and then they had to release them if there were no grounds for arrest. Back then, I thought I was already arrested. They kept me at the KGB until about eleven o'clock at night. First one interrogates, then another, then a third, then they leave me alone in an office for a long time, then they take me to some other office... Probably everyone who has gone through this knows all those first-day procedures: they run around, make noise, open doors, come in, creating the appearance of frantic activity, the appearance of a powerful, effective organization; all this is supposed to create a state of hopelessness in the detainee—a psychological workover. And indeed, it was terrifying; I got the impression: that's it, I'm caught. All sorts of thoughts race through my head... That notebook with “Duma”—it has edits. This notebook was in the hands of a person who works in Ternopil. I knew about those edits. The thought: I was caught because of that notebook; it fell into their hands.

It got dark, it was already pitch black when they led me out into the courtyard: “Get in the car!” On one side was a broad-shouldered KGB agent, on the other, I was squeezed in the middle. We're driving. I see we’re leaving Ternopil. In the front, another one is sitting—shoulders like a wardrobe. They turned on the music, playing loudly. They drive out of the city on the highway to Lviv. I'm thinking: now they'll take me somewhere into the woods and beat me, or kill me. I know what they are capable of; I know perfectly well what kind of organization this is.

They took me to some small town, I think it was Kozova. They brought me to a hotel and said: “You'll spend the night here. Do you want to eat?” I refuse—what kind of food in a situation like this. They brought a bun and a bottle of kefir. “Eat.” Two of them sat on stools by the door. They say: “Have your supper and go to sleep. You'll have a fun day tomorrow.” And they themselves sat down to play chess. It was an interesting game. They play, saying: “Oh-ho, so you decided to move your knight? Don't you see there are two bishops here, and you're playing the fool? We're about to back you into a corner! What, you've put up a pawn? We have to take it, take it!” And so they played chess all night. And so I didn't sleep all night. Then a whole day of moral torture at the Ternopil KGB. On the third day, they took me for a search in Borshchiv. I was living with a math teacher in a building next to the college. I open the door, we go in. I had a “Spidola”—it was a good radio, you could listen to “Radio Liberty.” I open the room—no one is home, the “Spidola” is tuned to “Liberty,” “Liberty” is talking at full volume... Obviously, they did this themselves with the help of that colleague-mathematician. “Whose radio is this?” I say: “Mine.” “Oh, ‘Liberty’! You listen to ‘Liberty’?” – “I listen sometimes.” They started the search. They turned everything upside down. They found the notebook with the poem “Duma.” It turns out that on the same day, there was a parallel search at my mother’s house in the village. There they took all the papers, all the books that had even the slightest underlining.

We arrived in Ternopil. Here they (finally!) showed me the arrest warrant. The third day of my detention was ending. (In the certificate, the date of detention is November 20, 1970, date of arrest—November 24. – V.O.) They took me to a cell in the basement of the Ternopil KGB.

During one of the interrogations, a whole group rushed into the investigator’s room: “That's it, get ready, we're going to the regional hospital!” I understand now that this was a performance that I fell for.

A doctor I knew from Borshchiv worked at the regional hospital. The second copy of “Duma” was in Borshchiv with his relatives, and this doctor had made some notes in it. I thought that it was because of this copy that I had been detained. It made no sense to remain silent about the existence of the second copy; it would mean setting up that doctor who made the notes, and I was terribly worried that someone would suffer because of me. I think: “They are going to arrest the doctor because of those edits.” I have to take all the blame on myself, I say: “I have another notebook, with such-and-such people.” They took that notebook from those people. True, I never told the investigator whose edits they were, but as we can see, they knew who made them anyway. To this day, I don't know what role that man, the doctor, played in my case. But it's a shame that I myself admitted to the existence of the second copy. If there hadn't been a second copy, there wouldn't have been the fact of distribution.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: It doesn't matter, Mykola, they would have charged you with “possession with intent to distribute.” And that’s the same as distribution. And the “intent” is pulled out of thin air.

M.A. Horbal: No, no, they knew that I had read “Duma” to people, there were testimonies from those informants that I had read it in such-and-such a park, that I was seen in such-and-such a place. So they were already following me.

I obviously wasn't very prepared for the cell. Because there were guys who knew what they could endure, but I hadn't prepared for something like this. But, fortunately, I didn't disgrace myself. I didn't point a finger at anyone; no one suffered because of me.

In the cell in Ternopil, there were two or three others with me, who were later released. From time to time, they would catch someone and then let them go. Apparently, they repented.

During the investigation, they took me to the madhouse in Vinnytsia for an expert evaluation.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: How long did that last?

M.A. Horbal: Well, probably about three weeks. When they were taking me to Vinnytsia, the car broke down in the middle of a field. They let me out of the car. It was chilly, as it was early spring. “Run around, warm up! Well, why are you standing there? Run around.” – I say: “I won't run.” I think it was a staged escape attempt. From such an insistent “run around, warm up,” I understood that they could just shoot me right there, because they had suddenly started caring about keeping me warm. They saw that I didn't want to “warm up,” started the car, and we drove on. It was a small van, a very modern paddy wagon. Like some foreign dry cleaner's van, or something, with small cabins for four prisoners—no one would have ever thought it was a paddy wagon.

We arrived in Vinnytsia. I was worried about the madhouse, I was afraid they wanted to make a fool out of me. Fortunately, the diagnosis was that I was “sane and responsible for my actions,” so I made it to trial.

When Major Bidyovka brought the indictment, I didn't want to sign it; it was full of terrible words: “Embarked on a path of struggle against the Soviet reality, hostile activity, this is hostile, that is hostile, overthrow of Soviet power...”—something like that... I say: “Listen, I'm not going to sign this—I didn't do that! What overthrow? In what way overthrow? I had my own point of view, I have a right to it, the constitution doesn't forbid it.” – “What are you telling me! The constitution was written for negroes, not for fools like you,”—he answers me in that vein. – “Take it, sign it.” I say: “I won't sign it.” – “So what, you want to keep sitting here in the basement? You've been sitting here for half a year already. Do you want to keep sitting? You wrote those two notebooks, engaging in nonsense! If I were your father, I would have given you a good thrashing! Look at him, such a great writer!”

I'm thinking: “Ah-ha, guys, you're trying to squirm out of this! You've held me for half a year for nothing—so now you have to write something terrible about me, to show you didn't hold me for half a year for nothing. And since the article starts at half a year...” Later it turned out they were deliberately leading me to that thought. “There was a wise guy here—Hereta, we confiscated two carloads of anti-Soviet books from him! So we really had to put him on trial—we gave him four years probation. Now he's working at the museum again. And you're here with your two notebooks—to sign or not to sign?” – Bidyovka continues.

And I believed his logic. I think, you can understand them—they need to somehow get out of this, to close this case...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: You had to help them… (They laugh).

M.A. Horbal: Help them… I reason to myself, they'll probably hold a trial, give me this half year that I've already served, because the article is from six months to seven years. Why would they give more? And they'll release me from the courtroom. If they took two carloads of books from Hereta and gave him four years probation? He's working, living freely, though silently, because if he says a word—the sentence can take effect.

I say: “Alright, I'll sign. But there will still be a trial...” “Of course, there will be,” says the investigator. “The article is from six months to seven. And if you start talking nonsense there, who knows how the court will decide.”

So at the trial, I didn't “push my rights” too much—what was I to “blabber”? – “Did you write this?” – “I wrote it.” I said during the investigation that I wrote it, I don't deny it. “How do you know this?” – “I heard it on the radio.” – “And where did you get such thoughts?” – “I heard it on the radio.” I'm not going to say that I learned it from someone, that someone told me, that I read it somewhere. Because how could it be: an anti-Soviet person formed right under their noses, when there's the Komsomol, when there's the Party—and suddenly a person with different thoughts! Where did this come from? Although—it's a normal phenomenon. I grew up when people were being shot, when I sat at the same desk with a boy in the first grade, and in the morning he was gone because, it turns out, he had been taken to Siberia with his family. Didn't I see people whispering among themselves, afraid to say a word, that the contingent (grain) was being taken away by men with machine guns? That in a neighbor's barn they were beating some woman with flails because she hadn't handed something over, she was crying out to God—didn't I hear this? Didn't I see where this government came from and what kind of government it was?

And they—that someone must have taught you this, that you must have learned it from somewhere, as if I had fallen from the Moon. I had to play the naive one—blame everything on the radio, the “enemy voices.” That's why the verdict said that “under the influence of listening to enemy radio stations, he embarked on a path of struggle against the Soviet reality by writing hostile, nationalistic...” and so on. That was the verdict.

The trial lasted exactly two hours, since I didn't deny anything—it was me, me, I wrote it. They went to lunch, brought me in a paddy wagon to the KGB, to the basement, gave me lunch, and took me for the reading of the verdict: “All rise, the court is now in session!” The court came in, read that for my anti-Soviet activities I was receiving five years in strict-regime camps and two years of exile in the Komi ASSR.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Was the place specified—in Komi?

M.A. Horbal: That's what was written in the verdict, but it turns out the court has no right to determine the place of exile. But my verdict said— “two years of exile in the Komi ASSR.” However, I was later exiled to the Tomsk region. No one paid any attention to that part of the court's verdict.

So that's how I ended up in the camp, Vasyl. Obviously, I was shocked by the verdict.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: What was the date of the trial?

M.A. Horbal: It says somewhere in those papers that it was in April, either the eleventh or some other day. I've already forgotten. I arrived at the 19th camp in Mordovia.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: You were sentenced on April 13, 1971.

M.A. Horbal: Yes, on April 13. Seven years! It seemed like a whole eternity. Seven years! They led me into the cell and suddenly this tension, this waiting, this uncertainty finally ended, everything suddenly became clear—camp, seven years… I sat down on the bunk and cried. For some reason, I cried, probably I relaxed. I prayed for this cup to pass me by. I don't remember the last time I had prayed. Although I grew up in a family of believers, I had somehow moved away from the tradition of turning to God every day—and here, suddenly!..

When I arrived at the camp, I saw that people had been sitting for 25 years. And it was nothing, sometimes they even joked. When I arrived, a very calm man, a former UPA soldier named Vasyl Yakubiak, who was arrested in 1946 and had served 25 years, was due to be released in a month. And I felt awkward before him with my sentence.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: With your five years…

M.A. Horbal: They brought me on a Thursday, they lead me into the camp, pigeons are flying, flowerbeds with flowers...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Is this zone 19, the settlement of Lesnoy?

M.A. Horbal: Lesnoy. The radio is playing, people are walking around—because there were many prisoners of retirement age who were no longer forced to work—they are walking around, strolling. They took me to the dining hall—it was relatively clean, they were serving some kind of borscht, I ate it and thought: “Well, somehow I'll survive here...”

On Sunday, a man approached me, from somewhere in the Lviv region. A fine man, he was a machine gunner in the UPA. He says: “Come, Mr. Mykola, our community has gathered over there, you can get acquainted.” It was there, behind the barbershop, on that patch of grass. It was warm, people were walking around, shirtless, so stately, mustachioed… I don't know, about fifty or sixty men were sitting in a circle on the grass, an enameled bucket of tea in the middle. It turns out—they had gathered to welcome my arrival in the camp. Vasyl Pidhorodetskyi was the barber in the zone, he cut the prisoners' hair, and this was next to the barbershop, he was the one who brewed that tea. I go around the circle, greeting each one: “Ivan Myron,”—he shakes my hand, states his term—“twenty-five years.”

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Was Mykola Konchakivskyi there?

M.A. Horbal: He was. Next was—big mustache—Fedorchuk, I think his name was also Ivan—“twenty-five,” “Basarab—25,” and me: “five,” “five.” I thought: What a disgrace, they should have given me more!

What am I leading up to? Even a year in prison is a lot, but everything is learned by comparison.

When I later met Ivan Svitlychny in the Urals, and Zinovy Antonyuk, and got acquainted with Valeriy Marchenko, I thought to myself, where would I have met these dear people if I hadn't been brought here? Such an argument is comforting. I admit: I was never so uninhibited, never had so much humor, and never was so ironic and laughed so much as in the camp. And truly, the best people were there—well, I don't need to tell you about it, you know this.

I promised myself that I would never complain to God, because God knows best which paths to lead me on. I repeat this phrase often, it is worth it. So that people know that you cannot complain about fate, because if this path is destined for you, then that's how it is meant to be.

Then there was a second term, I always reminded myself of this—“such is God’s will,” then a third trial... And this saved me. When they didn't release me after the second imprisonment but tried me a third time, I began to grumble somewhere in my soul: God, what is this? But then I remembered that I have no right to complain. I survived two terms with God's help—so this too is God's will, if I have to lay down my life here.

Later, when I was put in a cell with the Semyon Skalych you know, I even thought to myself: My God, to hear the revelations of this man, I really needed to end up in this cell, and to get here, I had to get another eleven years! This man told strange, mystical things, but that's a separate topic.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: But it would be worthwhile to say a little more about the camps. You weren't in Mordovia for long, were you?

M.A. Horbal: I was there for a little over a year. And then around July 1972, there was a large transport: they were opening three camps in the Urals. I think this was connected to the fact that the dissident movement had expanded—there were many arrests (mass arrests in January 1972. – V.O.), and the KGB didn't want these people to be together, because the camp is a certain consolidation of different forces: they took one from here, another from there, and in the camp they were brought together—they already start developing broader plans. It was necessary to disperse the prisoners. So the regime was ready to open more camps, even though it meant more guards, more staff, it was more expensive, but it was probably justified by their “better to be overcautious than not cautious enough.”

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Besides, Mordovia is relatively close to Moscow, and well-established channels for information getting out were already operating there.

M.A. Horbal: Yes. They wanted to move that new, active generation a bit further away, and they restored three camps in the Urals. There used to be political camps there, but recently they had been criminal zones. For example, in zone 35, in Vsekhsvyatsk, before our arrival, it was a zone for underage girls. They had fouled everything up, wrecked everything. Those girls didn't want to work; they couldn't even look after themselves. And they brought us there.

The transport was difficult. It took three days to get from Mordovia to Vsekhsvyatsk. A hot summer. As a rule, they transported us at night, and during the day they would shunt the wagons into some siding at a station, and this “Stolypin car” would heat up like a tin can… I remember there were about twelve prisoners in our cage. Sweat was pouring off us so much that on the floor, you won't believe it, it was about ankle-deep in sweat, that is, everything was soaked in sweat. Early in the morning, when they brought us to the Vsekhsvyatsk station and led us out of the train, I didn't recognize my friends—everyone was so terribly emaciated, I probably looked the same: everyone was dreadful, gray—in three days we had sweated ourselves out. There was no water; they gave us little, a cup twice a day. It was really hard. One prisoner died on the transport—unfortunately, I've forgotten his name...

Finally, we arrived. The detached “Stolypin cars” are standing in the middle of the forest, and it turns out we still have to be driven about five kilometers to the camp in paddy wagons. When they led all of us out—the sun was rising, so red, they surrounded us with submachine gunners, sheepdogs were barking, a bunch of vehicles were brought in. There were no paddy wagons, but there were such flatbed trucks. The sides were lined with boards, and behind them were submachine gunners. As we drove through the forest, there was also a soldier with a submachine gun at every turn—they were transporting especially dangerous prisoners!

And so the new zone was opened. About one hundred and twenty of us prisoners were brought to this camp. The premises were quite decent—brick barracks, the kitchen and club were more or less decent. We had to put the premises in order. The work in this zone was metalworking; they were just bringing in the machine tools.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Was this in Kuchino or Vsekhsvyatsk?

M.A. Horbal: In Vsekhsvyatsk. Zone 35. I worked on a lathe. The camp enterprise was a branch of the Sverdlovsk Tool Plant. We manufactured tools there, made taps, cutters—these are quite fine, precise jobs. The machine tools, however, were old; there were even American ones brought over during the war under Lend-Lease. So we worked on those machines.

I’m saying that my life hadn’t been easy even before that. I’ll go back to the beginning, that in 1947, when we reached the village of Letyache, there was no vacant housing; the Polish houses were destroyed, burned down. Some resettlers who had arrived here earlier had managed to settle in undamaged houses. We didn’t find any vacant dwellings; some undestroyed stable was left. We settled in that stable. We made one small room, a pantry across the hall, and behind it, a place for a chicken coop or a stable. That was our dwelling. And in 1949, it burned down. It had a straw roof, it caught fire and burned down. My father took 1949 very hard.

In that same year, they began to create the collective farm; those who didn't want to join began to be deported to Siberia… My older sister, Mariyka, who had completed two courses at a teachers' seminary in Krynytsia back in Lemkivshchyna, could have entered university without exams, but she had to go work at the sugar factory to earn some money—so she never became a teacher, never left the peasant life. She was the eldest among us children. Dad says: “Well, who will earn a kopeck, child, if not you, to at least put a roof on that burned house before winter?”

I remember my mother took a hatchet and went to the forest to cut down a small pine tree to make a rafter for the roof, and there was an ambush—an NKVD garrison hunting for Banderites. They caught my mother. They beat her with iron rods, so that good people brought her home half-dead on a sheet. We had our share of all kinds of trouble.

Even when we were in Lemkivshchyna, my father was always hiding from the Germans in the forests. He was a healthy young man, but those stresses, sleeping in the forests, took a toll on his health. He passed away in 1961, at the age of 63—not such an old man. I feel very sorry; he was a knowledgeable and soulful man. In Letyache, he—not a local resident—came and managed to organize the local community, to put the little church in order, he collected a bowl of flour or an egg from each household in the village, because where would you get money, he hired painters, and they restored the church. He led the church choir. I remember they would gather for rehearsals in our little hut. It was a good choir; the older people still remember and sing the church scores taught by my father. As a boy, I also sang in that choir. My father also led a drama club in the village; they staged plays. Despite the poverty, some spiritual life still flickered in the village. Considering those terrible times—I am proud of my father.

On the collective farm, my father worked as a carpenter. He was a good carpenter, because they said my father could make wheels for a wagon, and that, it turns out, is a higher qualification—if you can make a wheel. Because there's geometry, everything has to be calculated down to the millimeter. From time to time, my mother would send me to the workshop for wood chips, which we used to burn in the stove. Since my father worked there, I could bring a sheetful of chips. I would gather the chips and listen as the men told various stories and all sorts of witticisms. My father had a good sense of humor, he was an interesting man, it's a pity I couldn't communicate with him as an adult. And my father didn't always want to be open with us, the children. The times were such—he was probably afraid for us, that we might let something slip somewhere.

I must say I had one happy year—in 1960 I entered the college, and when I came home for Christmas, my father and I started singing carols in two parts from sheet music. Seeing my progress in solfeggio, my father was terribly happy. He formed a positive impression of me, that even if I hadn't made it yet, something could still come of me. From then on, my father and I became friends. Unfortunately, my father passed away just a few months later, in the spring of 1961. So our communication was not long. It was then that I became interested in his education and his life. He could have told me so much, but unfortunately—it didn't happen.

About the exile. I must mention the date of my release from exile, because they gave me a certificate...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: But you're skipping the Ural camp again?

M.A. Horbal: Well, there's probably enough material about that, because I served my time with Antonyuk, with Svitlychny, and with Marchenko, with Kalynets, and these people can tell no less about it. Valeriy Marchenko's book “Letters to Mother” has just been published. To a large extent, these are letters written from this very camp. When I read it, it seems that Valeriy wrote knowing that these texts should remain forever. I couldn't write to my mother like that—she didn't have a single year of schooling, because when she went to first grade in 1914, the war started, she studied for only six months, and then the school was closed, and that was the end of her education. The front passed through that Lemkivshchyna, and when the war ended, she didn't go back to school; she herded cattle. Later, when she was our mother, there was no need for her to write, because my father was literate. But when I was imprisoned, my mother started writing letters to me. At first, a whole letter was a single sentence. But by the end of my term, she was already using commas and even capital letters. That's how she learned to write, by writing letters to me in captivity. But they were extraordinarily interesting letters—a mother's letters to captivity. I have saved them all.

My mother was an extraordinarily interesting figure. To this day I can't comprehend it: not a single year of schooling, yet so much inner intelligence, so much warmth of soul. Fortunately, I managed to make a short video with my mother in the village. And then here, when I brought them to Kyiv. A strange figure, like my father: there was something mystical in this marriage.

My father could stand in prayer for an hour. I would still be sleeping, and in the morning he would already be at the table reading the Holy Scripture. I will probably write about my father separately someday. (Mykola Horbal’s memoir “1 of 60,” published in 2001, is dedicated to his parents. The author wrote warmly and vividly about his parents. – V.O.) As a boy, I was frail, perhaps somewhat stubborn, but with a heightened need to know the truth. I found it out...

Well, in the camp, I already started thinking: if God gave me such a path, then I must at least realize myself somehow. I started writing some sketches in letters, but, given the conditions, most of it was done conspiratorially. I tried to send that collection of poems “Days and Nights” to my mother in letters. But my mother not only didn't know what to do with it, she was also scared for me: “he's writing something there again.” I realized I had no right to complicate my mother's life. Ihor Kalynets helped out: he gave me the address of one of his Lviv friends. So from time to time, I sent her my poems-reflections, songs. In this way, some things were preserved. Svitlychna collected a lot, then some things through Kalynets. Eventually, Nadiya Svitlychna had the opportunity to publish it in America—the collection “Details of an Hourglass.” True, it also included some poems that I managed to send from my second imprisonment. And in Mykolaiv, during my second imprisonment, it wasn't a big problem for me to send something out of the camp: for example, this little book “A Kolomyika for Andriyko” I simply mailed in an envelope from the post office managed by a detachment guard (More details about this story in the memoir “1 of 60,” p. 234. – V.O.). It was later published in America as a separate booklet, with my own illustrations. The article that came out of my second imprisonment—“A Chronicle of Life in a Criminal Camp”—was passed outside the zone by fellow prisoners I knew; it was later published in Paris, in the newspaper “Ukrainske Slovo.”

Well, in the camp in the Urals, I just felt that I had to do something, because you can't just sit there with your hands folded. Back in Mordovia, Levko Horokhivskyi and I began to collect materials, at least to copy the verdicts of prisoners and pass them to the outside world. Even the text of a verdict—when you see what people are being punished for—became an anti-Soviet document. From the very first visit, when my sister Maria came to Mordovia, I passed information about the verdicts through her. She was supposed to take it to such-and-such a place. It's another matter whether those people passed it on, or got scared and didn't do it. But something did get out into the world, because if you do nothing, nothing will happen. I did get a little practice in this conspiratorial work, writing in micro-script on cigarette paper, so when the new “batch” of 1972 arrived, I already had some experience.

Obviously, it was a constant risk, “shakedowns,” you have to hide with it. I am absolutely convinced that one portion (an ampoule) of my information did end up in the hands of the operatives; they found it in a hiding place. Probably to catch me in the act of passing it outside the zone—they put it back, but I guessed—I had a mark that it had been in their hands, I understood—they had noticed it. There was a method of marking, with radioactive isotopes. Wherever you hid a piece of paper treated this way, they could find it with special devices. Apparently, they were so happy to have found a lead that they got impatient and started fussing: someone slipped me a few sheets of cigarette paper; suddenly my pencil disappeared—I wrote with a chemical pencil, it could be sharpened with a blade as thin as a hair. You write five or six lines, then sharpen it again, but it wasn't a problem, it wrote finely, better than a ballpoint pen. And this pencil of mine disappeared. It was gone for a week. Then they planted it back. Ah, I thought—the scoundrels. I rewrote everything from that ampoule, and destroyed the marked one. How much of an emergency there was! But that's a separate topic. They couldn't catch me “red-handed.” Despite everything, from zone 35, we managed to pass a lot of things outside the zone. We wrote a chronicle of the 35th camp.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Was it published somewhere? In the “Chronicle of Current Events”?

M.A. Horbal: I think so. All those materials were there: who is on a hunger strike and when, when they came out of it and what they are doing, who was put in the punishment cell—all this was recorded, not to mention the statements. (See also: Mykola Horbal. The Weight of a Word. “Chronicle of the ‘Gulag Archipelago.’ Zone 35 (For 1977)” // “ZONA” magazine, 1993. – No. 4. – pp. 134–150. – V.O.). By the way, Vladimir Bukovsky doesn't even suspect that I was the one who copied his book on punitive psychiatry in micro-script. I copied it twice, because one time Semyon Gluzman lost this thing during a visit, it got drowned somewhere, so I had to write it again. So it was quite a large volume of work.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: You had to hide. There was a library there that the guards could enter at any moment and take things away.

M.A. Horbal: They could. But, firstly: a portion of the finished materials, which were not yet sealed and glued, was kept in my books. I guess it's okay to talk about this now? I would very carefully glue two pages together and stuff the papers between them. If you flip through this book or shake it, it won't fall out. Sometimes I couldn't find it myself. I just knew which page to look for. Glue the pages around the perimeter, and leave only one small place unglued and stuff things in there... That was in the books. Secondly: I didn't keep what was already written on my person. If a guard came in, I had the opportunity to eat one piece of paper. I never got caught. Not once. I wrote in the barracks and in the library. The best place to write was in the library, when Ivan Svitlychny was the librarian. He was the librarian for a while, so someone would sit, read, and watch the door. And I would sit with my back to the guard, so if he came in and I was given a sign, I could quietly hide it or eat it. And if it was written—on these small strips—I would stuff them between the pages. They never found them.

Through the library, we had a perfect connection with the PKT [punishment cell block]. We developed a system of communication through books. I've forgotten the mechanism now, but the pages were counted from back to front. Let's say, an even-numbered page, or every other page. In the second or fifth line from the bottom, a letter would be faintly marked with a pencil. No guard ever figured it out. Two or three letters per page—entire statements came out of the PKT this way. When you sit for years, you can develop any kind of technology. No secret compartments for you, no invisible ink or milk—just a faint dot on a letter. Once a week, books in the PKT were exchanged.

Conversations with Kalynets somewhat changed my understanding of poetry—rhyme became optional. Thus, a collection of captive reflections appeared. A lot was lost. During my first imprisonment, I wrote about two dozen songs. Most of them were sent in letters. For example, “Children's Carol”—it's a dedication to Proniuk's son, Myroslav. Proniuk sent this song in a letter to his wife. The song “White Stone”—Volodymyr Dziak, from Lviv, sent it for his daughter Vira's birthday... Most of the songs were sent by friends in letters to relatives as greetings on some occasion. Obviously, the authorship of the song was kept silent.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: What, you wrote them with musical notation?

M.A. Horbal: With musical notation! The first song (in the Lemko dialect) “Cemeteries”—Ivan Svitlychny sent it to Liolia (Liolia—Leonida Pavlivna Svitlychna, Ivan Svitlychny's wife. – V.O.). The letter with this song arrived around the time Dziuba repented, so they even thought the song was a dedication to this sad, depressing event. Because they all went through it, they were all depressed by what had happened, they felt very sorry for Ivan. And then suddenly they receive “Cemeteries,” so for some reason, they thought it was a reaction from the camp to that event. And that it was written in the Lemko dialect was, they thought, so that it wouldn't be too easy to figure out. I only wrote three songs in the Lemko dialect; the rest are in the literary language. “And the Field is Black”—also a children's song, I don't know which child it was sent to. Ihor Kalynets sent “By the Stream” to his daughter Dzvinka. Later, Nadiya Svitlychna included all these songs in the collection that was published in America.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And what is that collection called?

M.A. Horbal: “Details of an Hourglass,” it's a collection of captive poems and songs, the songs with musical notation.

In the zone, I tried not to get into conflicts—I fulfilled my work quota, didn't violate the regime. I violated it like everyone else, together with everyone—I went on hunger strikes, wrote statements when everyone else did. That is, I wasn't passive. I saw my dossier, which the staff of the Perm “Memorial” copied from the materials of this camp. Interesting documents, some of which I had already forgotten. For example, Gluzman and I wrote one statement. It's interesting because we asked the Prosecutor General's Office if I had the right to dispose of my own body when I die in the camp. After all, the Soviet authorities didn't even give the dead body back to the relatives.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: It seems the Perm “Memorial” has the text of this statement.

M.A. Horbal: That's what I'm saying—they collected material on the activities of zone 35. To clarify: I took part in all the collective protest actions in the zone. There were several such mass ones. During that long hunger strike, in which we planned to come out of the hunger strike one by one (only Svitlychny, Antonyuk, Gluzman, and Balakhonov fasted for more than two months), I started having convulsions on the eighth day, and they suggested I stop the hunger strike. We knew it would be a long hunger strike, maybe more than a month. But on about the eighth day, a dentist came to the camp. He comes once a year, maybe once every two years. And I had a toothache, so my friends said: “Just go and have it pulled.” I thought so myself: I'll go and have it pulled, because who knows, maybe it will hurt, I'll pull it—and have peace. That medic pulled out the top part of the tooth, broke it, and the root remained. He gave me an injection and started splitting that root into pieces and digging it out piece by piece. Then he gave me another painkilling shot. The body had been hungry for several days, and apparently, those injections had some effect on me, because at night—and I was sleeping next to Kalynets—I started having convulsions. That is, my legs were contracting, my hands were shaking, and I couldn't do anything about it, I couldn't stop them. Everyone got scared, someone ran for the doctor, they took me to the hospital on a stretcher. I think it was from those shots.

Five months before being sent to exile, I was suddenly put in the PKT—for no reason at all. I think it was so they could prevent me from passing on information. One evening after work, at roll call, they read out that I was sentenced to six months in the PKT. I say: how can it be six months, I only have five months left until the end of my term? They gave me more than I had left. But the guards didn't leave my side for a step, they took me to the cell, locked it. True, they took me from the PKT for transport a week earlier, but they also transported me for another 50 days. So when they released me into exile on January 14, 1976, they counted those 50 days, in excess of my term, as one day for three. There is such a law. Because I should have been out of custody for 50 days, I was a relatively free man, and they were keeping me in a cell. Therefore, my term was shortened to June 24. So I served everything, you need to know this. And the fact that I got out in June, and not on November 20, was due to this transport.

It was a very difficult transport. In Sverdlovsk, they kept me in a punishment cell, because it was written on my file in red pencil: “To be escorted and held separately.” The prison warden comes and complains: “Well, where am I going to put you separately from the others? One and a half thousand people pass through the prison every day!” And this is the Siberian main line, transports to the Far East, to all of Siberia, go through this prison. Such a combine, a slave market. Dozens of vehicles—some bringing in, others taking out prisoners around the clock. And he threw me a board in the punishment cell—not a bed, but such a plank, so as not to sleep on the concrete. And the cell was narrow, just a toilet bucket, my head on the toilet bucket… I started demanding, “pushing my rights,” what I was entitled to, and this was “cell-type confinement.” – “Well, where am I supposed to put you? You see what’s going on here?” I agreed to it. And the prisons there are spat-upon, filthy, stinking, lousy, with bedbugs!

In Tomsk it was already easier, because there was a separate cell for exiles. It turns out, there's an article for exile, besides the political one, there's also one for murder. They served 15 years and still have 5 years of exile. Alimony dodgers, who were given exile without imprisonment. They went under convoy through the prison to exile. He didn't pay alimony, was hiding from his wife somewhere, they caught him, gave him two years of exile, he has to live there and pay alimony. He has no right to leave from there, because he's in exile.

The cell was full of exiles. They kept us in this cell for several weeks—a long time. Once during a walk, I said: “Let's not go back to the cell, we all should be free today, and they're keeping us here. Why are they keeping us?” I incited them, that we wouldn't go back to the cell after the walk. And really, why weren't they sending us on? We were being eaten by lice, the prison was old, wooden, infested with bedbugs. Well, what is this? The block guard came: “What's this?” I say: “We're not going into the cell.” – “Who are you?” – “What difference does it make who I am. Why am I not being sent on, I'm a free man, I should have been free for the second month now.” – “Hey you, come here! What's your article?” – “62.” – “What kind of article is that?” In Russia, it turns out, it's for something like alcoholism—something like that. “An alkie, are you?” – “No, this is the Ukrainian SSR, the Russian equivalent is 70.” – “Ah, so that's what kind of bird you are! So you're already starting to stir up trouble for us here? We'll fix you right now!” – “Don't you scare me. Sooner or later, I'll be free anyway, and in a few days the whole world will know what's going on in your prison here.” And indeed, the next day they announced that the whole cell was going to Teguldet. “Get your things together!” And I know that Mykola Kots is in exile in Teguldet, I have his address. I tried to get the addresses of all those exiled to Siberia while still in the camp. It was December 19, St. Nicholas Day—we were being transported. I'm thinking: “I'll be at Mykola's name day celebration today, what an unexpected meeting it will be.” They lead all of us into a “holding pen.” Suddenly the door opens: “Who's Horbal?” – “I am.” – “Come out!” They took me back to the cell.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: They left, and you stayed?

M.A. Horbal: Yes, they took them. They brought me to the same empty cell, locked it. But around ten o'clock at night, I hear a commotion in the corridor, clank-clank of keys, the door opens—all those prisoners are being brought back into the cell. I ask: “What happened?” – “Well, the weather's not flyable at the airfield, a blizzard.” They were supposed to fly on a “Kukuruznik” [An-2 plane], but they didn't. But they had already breathed freedom, they were at the airport. “Come on down, Kalyok!”—I was on the top bunk. One pulls a huge white loaf of bread from his bosom, another a stick of sausage—it turns out they had already “stocked up,” they had been to the kiosk at that airport. Someone else pulls out a bottle of vodka—and they managed to bring all that into the prison—thugs! So I unexpectedly celebrated St. Nicholas Day in prison. I got a piece of sausage, a swig of vodka (in prison!). That was a strange St. Nicholas Day in 1975. Of all the St. Nicholas Days in my life, it's perhaps the most memorable.

They kept me here for about another week and then finally took me for transport—by paddy wagon. They drove for about twelve hours and brought me from Tomsk to Kolpashevo. I was there in prison for about another week. It was a district town, the prison there was quiet, clean, they fed us well, I thought they would leave me there. I say: “Why aren't they releasing me?” – “Well, we don't know, we don't know.” One morning they took me and drove me to Parabel.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: How did they transport you?

M.A. Horbal: By paddy wagon. Also a long time, about eight hours, it shook terribly, on a frozen, roadless path, through the taiga...

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Is it a dirt road there?

M.A. Horbal: Probably. We were thrown around so much in there—I think there were three of us being taken there. They brought us to the police station. It was a Friday, the end of the week. So I sat there at the police station with the fifteen-day detainees until Monday. On Monday morning they called me and said: “Get ready for the plane, you'll fly to...” To some village there. Another hour by plane from Parabel to that village. Such are the Siberian expanses—by plane from a district center to a village. They brought me to the office, looked over my accompanying papers with unconcealed antipathy. And I'm in that stinking prison smock after those transports, unwashed, lousy. Some boss there said: “You will live in the cattle-breeding brigade, a tractor will be coming for the mail soon—you'll go on that tractor.” Indeed, a tractor-sleigh arrived. About an hour and a half later, I was at the office of the “cattle-breeding brigade.” There was only a farm and about ten wooden houses. The manager came, some old Latvian, probably one of the former exiles: “Oh, my God, well how are you, and what are we to do with you—well, you'll be a cattleman.” I say: “And where will I live?” – “Well, I don't know, we have one ‘keldim’ here (I, of course, don't know what a ‘keldim’ is)—well, we have to break open the door. Go, Fedya, get a crowbar.” They got a crowbar, the door was boarded up—they tore it off. “You will live here. Two exiles lived here. One killed the other, so we buried that one, and this one was arrested, taken away.” Thugs. No kitchen, everything is falling apart. The floor is torn up. I say: “But how can one live here?” – “Well, there is no other housing.” I say: “Then I won't live here.” – “Well, where are we going to get you a better one?” I say that the regulations on exile state that I must be provided with housing. I am a free citizen, I just don't have the right to leave here—and what is this? – “And where am I going to get it for you, what can I do? I don't have any.” Forty degrees below zero, January, I was just released on January 14, on the old New Year.

So I spent the night in a manger in the cowshed—with the cattle, it's a bit warmer there, the cows are breathing. In the morning I went to that office again to protest, but there was no one there, it was locked—some guy was standing there, he had come to the store for wine. So we got to talking. And it turns out, he's a Ukrainian, working at a logging site, there's a logging site nearby—well, he says, come and spend the night with us, maybe you can get a job at the logging site. And I went with him. A dormitory, well-heated. There were indeed guys from Ukraine, from Kuban, they received me with sympathy, I had dinner with them. Dinner, of course, with a drink. I say: “Guys, I have no money, I have nothing.” “Never mind, never mind—if you're alive, you'll have everything.”

In the morning I went to the post office. I had postage stamps, about three rubles worth, I approach the postmistress, I say: so and so, I'm in exile, from prison, a political, I need to send a telegram, but I have no money, I have stamps. If, I say, you take them, and tomorrow the money comes by telegraph, I'll pay you back. – “What difference does it make to me, stamps are money.” I say: for this amount. And I even had about a ruble left. I sent an urgent telegram to my mother to wire me 150 rubles. The next day I received the money at the post office.

In the evening, I treated the guys. Logging—they're tired from work. The work is bad, they pay little—not as promised, but they are on contract, and they have to finish their term here. There's a banya there, I washed, washed some of my clothes. The next day I went to their office, to the boss, and said: “Hire me to work for you.” He says: “I'm not against it. But I can't hire you without permission from your superiors.”

I had been in transit for two months, before that I was in the PKT... I say: maybe there's something easier to start with, because I'm a bit weak after the transports, I wouldn't want to let the guys down, it's a brigade, they all work together, and when I recover a bit, I'll work on par with them. “Well,” he says, “for now you can haul water with a horse to the kitchen, and we'll see from there.” So I agreed.

But I had to go to Parabel to the authorities for permission. I have money now, and the plane brings mail there twice a week. I washed, I'm in no hurry, the head of the logging site gave me four days off.

I’m getting ready to go to Parabel, to the police station for permission to work at the logging site. About a week later I arrive, I go into the police station. They: “Eek-eek-eek! Where have you been?” It turns out, they had already put out a search for me, the whole KGB was on its feet—they were looking for me, Horbal had escaped.

And there's a commandant over the exiles there. How he yelled at me! “I'm the commandant, I'm already looking for you, there's a search out for you!” Well, I say: “Are you making an idiot out of me? I'm not afraid, I just came from there. By law, you are obliged to provide me with housing—why did you shove me into a cowshed? No housing, nothing. I need to wash, to do my laundry... Who do you take me for?” And the chief: “Quiet, quiet! You're not going anywhere, you'll stay in Parabel.”

So they left me in the district center. I didn't become a “cattleman.” “You will go to the site.” This, it turns out, is six kilometers from Parabel itself, a construction site for “Tomskgazstroy.” They put me in a dormitory. They immediately set me up as a stoker. The work was hard: there were two of us stokers, working twelve-hour shifts, without days off. The heating was with oil, because there was a pipeline nearby. And the boiler room was made of concrete slabs—a suffocating stench, no ventilation. It had to heat their administrative building, a few houses for these civilian employees who worked there, and the dormitories of the “khimiki”—criminal prisoners on parole, who had to work off the rest of their term here. They were, in fact, the ones building the “oil pumping station.” These are huge tanks, a pumping station, reservoirs that they fill with oil, because sometimes something happens on the line, and the pressure in the pipeline has to be constant, and they turn on these cisterns through compressor stations.