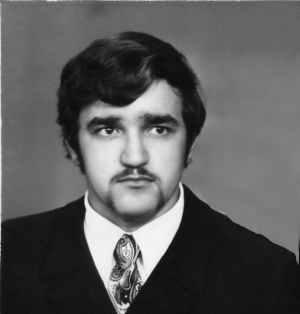

I n t e r v i e w with Lyubomyr Zenonovych S t a r o s o l s k y

and his mother, Oksana Mykolaivna S t a r o s o l s k a

Last edited on November 23, 2007.

Vasyl Ovsiyenko: January 28, 2000, in Stebnyk, Lviv Oblast, at the Starosolsky home at 5-A Olekshyshyn Street, Ms. Oksana Starosolska is talking about her son, Lyubomyr.

Oksana Starosolska: I, Oksana Mykolaivna Starosolska, a resident of Stebnyk, was born in 1935. My son, Lyubomyr Zenonovych Starosolsky, raised a blue-and-yellow flag in 1973, under the Soviet regime. It was on May 9. At that time, the entire Soviet state was celebrating Victory Day. And the boys from the 10th grade thought they should make their own Victory Day, one that looked Ukrainian, and they hung up a blue-and-yellow flag.

V. O.: And how did they do that? What were the names of the other boys, besides Lyubomyr?

O. S.: Klapach and Dmytriv. They were all classmates, tenth-graders. They were all in the same class. But Klapach was tried along with Lyubomyr, while Dmytriv was released on surety. Because, how should I put it, Dmytriv was a slightly worse student, and his father didn't let him go hang the flag. They had prepared the flag in the attic of another boy’s house. He was also released on surety. Dmytriv was there too, but when it came time to hang the flag, only he and Klapach went. (O. Starosolska consistently calls Roman Kalapach “Klapach.” – V. O.).

V. O.: And where did they hang it? It must have been at night, right?

O. S.: Of course, it was at night. Klapach came over, they talked about something, and Lyubomyr told me he was invited to a send-off party for a friend who was going into the army. And Klapach confirmed it. I let him go to the party. He came home around three or four in the morning, something like that. I knew he was at a party, so I got up and even said to him, “You didn’t drink any vodka, did you?” He looked at me and said, “Mom, what are you talking about? Where would I be drinking vodka? Was there nothing else to drink there?” But he hadn’t been to any party—he was hanging that flag.

After they hung the flag, a joke even started going around Stebnyk... Because they hung the flag in the middle of town. There was a crossroads there, you know, with those little pennants hanging. They took those down and hung the blue-and-yellow one. Klapach—his house was across the river—he folded up the Soviet flag, put it in the river, and pinned it down with a rock. They also went and hung a flag on the House of Culture in Old Stebnyk. But there was a watchman on duty. He came at dawn and took that flag down. The police later asked him, “Why did you take it down?” And he says, “Well, how can I put it—when I was going home, yours was hanging, and when I came back, ours was hanging. I took it down because that flag isn't supposed to be there.” So everyone in Stebnyk laughed, saying, “When I was going home, yours was hanging, and when I came back, ours was hanging.”

My son wasn't allowed to finish 10th grade. He was given a failing grade for conduct and barred from exams. And at that time, he was considered the secretary of the school's Komsomol organization.

V. O.: Imagine that!

O. S.: They did that in 1972, but the investigation went on, so they weren't arrested until February 1973.

V. O.: So he wasn't under arrest while the investigation was ongoing?

O. S.: No. He was summoned for questioning. They couldn't arrest him because he wasn't 18 yet. His birthday is on May 8, and he hung the flag on the 9th. So from February 1973 until May, they held him in Lviv in what they called a pre-trial detention cell, until he turned 18.

V. O.: How did you take it—the arrest of your minor son, straight from his school desk?

O. S.: How did I take it? You know, I was ready to kiss not just the hands, not just the feet, but the entirety of those investigators, those KGB men, if they would just let the child go. He was just a child! Maybe the boys didn't think it through, maybe they didn’t consider the consequences. Give the boys a chance to make amends... Klapach was applying to law school, and my son was going to apply to a pedagogical institute. For me, it was like a bolt from the blue. If I had known even a little bit, I would have—I don't know—tied him up or done something to stop him from doing that, because it was a death sentence. As one investigator told me, “You are very lucky that he is only 17 years old, because from there, where the sun rises, he would never have returned.” Those were the words of a KGB man.

V. O.: Boys in Chortkiv did something similar. That was Volodymyr Marmus and others; there were eight of them. In 1973, on the night of January 22, they hung four flags and 19 leaflets. Volodymyr Marmus got six years in prison and five in exile, and the others got less. Thank God, they all survived. I knew those boys too.

V. O.: And how did the population here, the people, view this act?

O. S.: I’m telling you how they viewed it—they made up a joke: “Yours was there—but now ours is hanging.” Even today, people meet me and ask, “Does Lyubomyr have a job? What—Lyubomyr isn’t working anywhere? He isn't! Oh!”

V. O.: Clearly, it wasn't just a boyish prank. The boys did it consciously. As far as I know, your whole family was nationally conscious.

O. S.: I'll tell you, one of my mother's brothers was in prison; he was arrested in 1946. He was a nationalist, in the OUN. He was well-known, and the communists feared him. Even though he didn't join the UPA, they arrested him in 1946 when they were clearing out the area. He was born in 1905. He had organized the OUN back when Poland ruled here. We have two uncles abroad—they were also in the UPA. One uncle came to visit recently. We're sitting right here, and my uncle looked around and said, “You don't even know that Stepan Bandera walked down this street.” We just froze: “How?” And he says, “That’s right. Because he spent the night in our old house—we had an old house there. And I led him over there, to Dobrohost.” Well, what year could that have been? It must have been under the Poles.

V. O.: Yes, under the Poles. Because the Germans arrested Stepan Bandera sometime in late July 1941, and he never returned to Ukraine after that.

O. S.: Yes. He's sitting on the straw, looks over, and says, “Oh! You don't know this story, that Stepan Bandera walked along this road.” So we come from a family that couldn't reconcile with them.