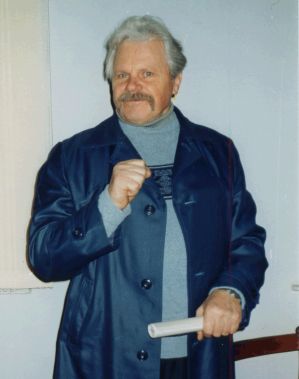

Interview with Dmytro Romanovych SHUPTA

(On the KHPG website since March 7, 2008. D. Shupta’s corrections made on March 30, 2008)

V.V. Ovsiienko: On February 12, 2001, in the city of Odesa, at the editorial office of the newspaper `Dumska Ploshcha`, we are conducting a conversation with Mr. Dmytro Shupta. Recorded by Vasyl Ovsiienko.

D.R. Shupta: Shupta, Dmytro Romanovych, born January 20, 1938, in the village of Kurinka, Chornukhy Raion, Poltava Oblast. I finished seven grades in my village, then studied in the neighboring village of Mokiyivka, 6 km away, where I completed my secondary education.

My parents were peasants. My father was captured near Lutsk during the First World War and was a prisoner of war in Germany until 1924. At the front, he was in a topographical platoon, holding the position of a junior officer—an unteroffizier. He had a talent for drawing and knew fonts, which helped him a little. But how did he get captured? An exploding shell under his horse left him concussed, with no memory. This was with Samsonov's army—that army was encircled.

I won’t tell you my father’s whole story, only that in the concentration camp, he played female roles in dramas by Vynnychenko. He had a handsome face, blond hair, blue eyes, and was short in stature, so he played women there. But the theater also put on productions in the city, on a Berlin stage. He later became a cemetery artist and had semi-legal access to the city.

They were exchanged for German officers after the “leader's” death. When they were returned to Moscow (he was a prisoner with his cousin), they were offered jobs as Kremlin guards. His comrades agreed, but he refused under any circumstances and went home to his village. He took up farming, got married, but in 1929, he was repressed as a wealthy peasant because they began creating collective farms then. He was exiled to the Arkhangelsk region, where he loaded tree trunks, standing up to his knees in icy water. Perhaps he was saved by the fact that he developed two hernias and could no longer physically work loading these logs, so he was assigned to some household duties. Around 1937, he received a paper stating: “Convicted on a technicality.”

Then the war. During the occupation, my father took us out of the village where I was born. After the end of the German occupation, my father didn't end up at the forcing of the Dnieper, but in a howitzer regiment in the Kirovohrad Oblast. He was on guard duty near Iași while the howitzer crew was sleeping in a small house. There was an artillery barrage, and either a heavy shell or a heavy bomb hit the house. Nothing was left of the house, but my father was buried by a wall. Everyone in the house died, but he miraculously survived. I think some doors were lifted, they saw part of a person, and dug him out. He was severely concussed and was treated on Lake Balaton, but when he came home, they seized him and sentenced him. They gave him 25 years, he was even threatened with execution. I won't say why—because he never told us anything about it. We were told he was a “traitor to the Motherland.”

There were five of us—from my mother—and two more from my father’s first wife. I finished school. When Stalin died, my father returned. All this time, we lived in a state of hunger. For us, it wasn’t just the famine of 1947—we were hungry until I even finished school. And it wasn’t just our family, not just our village. Even though it's 200 km from Kyiv, it’s on the periphery of the Poltava Oblast.

I went to Simferopol to enter an art school. A fellow countryman, an artist whom I had helped with stage design at the club, took me there. But we arrived too late, the exams were already over, so I had no choice but to go to Technical School No. 3 named after Admiral Makarov on Ushakov Balka in Sevastopol. A teacher I knew from the Sevastopol technical school, Yevhen Ivanovych Chertkov, took my documents. He took my address and said, “I'll send for you.” I waited and waited, and waited, and I knew that classes had long since started there, but they didn’t call for me. I went there—they accepted me, and I started studying.

V.O.: What year was this?

D.Sh.: This was 1956. And before that, I took exams for the industrial technical college in Kyiv. I was failed there. And a notebook with my poem “Teresy” (The Scales) was stolen. (It touched upon many political and other delicate life issues. It came to the attention of the KGB. From then on, the author was under constant surveillance. – From D. Shupta’s memoirs).

I didn't tell anyone there that I wrote poetry. Because of provocative moments… (Sevastopol was a “closed city” at the time… On May 1, 1958, during a May Day celebration outside the city, I was detained by men in civilian clothes and taken to a border post, where they conducted an interrogation and a three-day check, after which they finally released me. – From D. Shupta’s memoirs). So, the next summer, I prepared to leave the city and enter the Simferopol Art School. I prepared well, it seemed. But in the 9th grade, I had ocular tuberculosis and was blind for a year. The damp Crimean climate, especially in winter and autumn, didn't suit me. I felt unwell and thought that art school would require a lot of eye strain, plus there was no dormitory, the stipend was very small, and most importantly, it was four and a half years of study. I thought I could finish an institute in that time.

So I entered medical school. They were nearby, on Nekrasov Street in Simferopol. Although the deputy director of the art school tried to persuade me to go there. I had only taken the special exams there, but I took the entrance exams for medical school.

The following year, I was summoned to the regional health department, to the office of Titenko, the head. She went out, and two well-built fellows asked: “Why did you run away from Sevastopol?” I said, “I didn’t run away, I enrolled in medical school.” “What are your plans?” I didn’t know what to say, but I remember a phrase slipped out, that in life I don't shy away from any work, and then: “You have to work, work to have something.” For some reason, they didn’t like that. (For the first time, they openly tried to recruit me to be a stool pigeon, which I refused. The interrogation lasted from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m. Later there were other summons to that service, but also without result. – From D. Shupta’s memoirs).

I was the head of the trade union committee for the entire school. After that conversation, they removed me, and I didn’t graduate from medical school with honors, even though I had been an excellent student the whole time. This saddened and alarmed me very much—why? Because I dreamed of studying at a medical institute after medical school.

I tried to get into medical institute 4 times. And all 4 times I didn’t know why they wouldn’t accept me. Finally, I got into medical institute, thinking with some malice: I’ll study for a year, show them I can learn, and then leave. By the way, I had gone to medical school because I hadn't passed the competitive exams for the institute. During that time, I also tried to get into the Kyiv Medical Institute. There, from a distance, I saw a note in red pencil on my file and understood that I would never get into that institute. I traveled to enroll in the agricultural academy in the agrobiochemistry faculty. The department head there talked me out of it: “But you're already studying at a medical school.” Every summer I would go somewhere to try and enroll. Nothing worked out. Finally, I passed the exams for the chemistry faculty at Kyiv University, although I wanted to get into hydrobiology. But it had been closed in Donetsk and Lviv, as well as in Kyiv. Only Odesa University still had a department. Whoever wants to, go there. I imagined how many of us would flock there and decided to take my scores and go to the Crimean Medical Institute. I showed them to the rector, and he said: “So it’s you? We know you. Come back next year.” That was my third attempt. On my fourth try, the following year, I already knew I would pass the competition at the Crimean Medical Institute.

During that time, I worked as the head of the medical unit at a reinforced concrete products factory. All the workers at the factory were ex-convicts. I didn't know this when they sent me there. The head of personnel there was a man named Krutikov. He constantly came to me with provocative questions. I had boxes of vitamins, and he would just scoop up a pocketful and leave. I told him off once, then a second time. I went to the director to complain and realized I wouldn't be working there much longer. People from the KGB came. When I found out the guest was from the KGB, I invited him: “It's your turn.” I felt something was wrong. But he said, “No, no, I'm not here for an appointment.” Then I found a moment when no one was around and asked, “So why are you here? I can't see patients with a stranger present.” He took out his credentials and said, “Come with me.” They took me to the KGB methodically—once a quarter, for sure. For conversations, interrogations, and recruitment attempts to become a “stool pigeon,” which drove me to the brink of madness.

During my studies at the medical institute, I changed jobs about seven times—not by my own choice, not because I was a negligent worker. They arranged it so that I couldn’t stay in one job for long.

Eventually, I got a job with the “emergency ambulance service.” That’s where I was when I graduated from the medical institute. I graduated with honors. I was constantly analyzing my situation. In our third year, they were recruiting guys for the military academy. The C-students and just about anyone went, but I didn't pass the credentialing committee. Before graduating from the institute, I knew they were planning to keep me on at one of the departments. Such rumors were circulating. I went to the rector and said, “Please let me stay in a practical department, not a theoretical one.” Any would have suited me. “No, you'll go and work for a bit, and then we'll call you back.” I said, “I'll forget everything, and then who knows—maybe I’ll get married, maybe something else will happen.” Why did I want to stay at the institute so badly? There were people there who helped me—for example, they told me I was on the “blacklists,” this was after I didn't pass the credentialing committee. I was criticized several times at the Komsomol course meetings as a negligent Komsomol member—why? Because I was either working or studying, I didn’t have a single free second.

One time, I received a large package at the post office. Oleksandr Ivanovych Hubar, an associate professor from the pedagogical institute (now Crimean University), happened to be with me. I said, “Oh, look, Oleksandr Ivanovych, what a package!” We tore it open in the little park next to the post office—and there it was, Ivan Mykhailovych Dziuba's `Internationalism or Russification?`! He exclaimed, “Hide that quickly!”

V.O.: And in what form was this work? A typescript?

D.Sh.: Yes, a typescript.

V.O.: When was this? The work generally appeared at the beginning of 1966…

D.Sh.: It was around 1967. Hubar looked around and said, “See who's sitting over there?” And there were these pumped-up athlete types. They were “tailing” us. I took the package, and we went our separate ways. I brought the work to the medical institute. I kept it, and it was only in 1983 that it disappeared somewhere—vanished into thin air!

This Hubar gave me a “good path” at the newspaper—they used to publish budding poets there. I was in the Crimean literary association.

We had a classmate there, a guy named Yevhen Kaplych, with a tape recorder. He would provoke me into conversations. I'm sure he recorded them. I didn't think at the time that he was recording—it was only later that I figured it out...

I had a few dates with girls. Generally, I didn’t have time for dates… I remember one evening in Gagarin Park, I was walking with a girl, and behind us—people with movie cameras! She noticed it and said that we were being filmed. So much for the date.

When I was studying at the medical institute, in 1963, I was at the Odesa literary seminar, where Vasyl Stus, Vasyl Zakharchenko were...

V.O.: And Bohdan Horyn was probably there?

D.Sh.: And Bohdan Horyn was there. Everyone, except those who were planted, was later repressed in one way or another. There are books where I am pictured with Stus. I see that you are studying Vasyl Semenovych. Maybe you didn’t notice, but I'm in the photos there.

So, I didn’t manage to stay at the medical institute in a department. I receive my diploma without even a job assignment—a “red diploma” without a job assignment! I return to my native village. It's the main center of the collective farm, which included several other villages. I think, let's have a medical ambulatory here, I'll work in my home village. There was a building to set up the ambulatory. The chairman of the collective farm was a former school director. Young, energetic, a graduate of Odesa University's biology department. Hryhoriy Tymofiyovych Yasko, from a neighboring village. I go to him—“Come back tomorrow.” He probably consulted with the necessary people. “Go to the regional center—they should give you permission for the ambulatory there.” I go to Poltava. Of course, no one was waiting for me there, no one had called them. Or maybe they did call, but did the opposite. My fellow countrymen—my classmate Mykola Ivanovych Nazarenko (who worked at the pedagogical institute) and Hryhoriy Fedorovych Artyukh (an oncologist who had graduated from Kharkiv Institute) say: “Get out of here, nothing good is waiting for you. There will be no ambulatory in the village.”

So where did I flee—I got a job as the head of the therapeutic department at the railway hospital, that's Poltava-Pivdenna. I could work there, but as I understand it now, I would never have received housing. I was interested in surgery. During the day I worked in therapy, then I'd go up to a higher floor and spend the whole night in surgery. On one hand, this seemed good, but on the other, the head doctor said I wouldn't get a position in surgery for seven years.

I had to go home again. I get a job as a surgeon in Pyriatyn. At this time (in 1969), I managed to get into a specialization course in Kharkiv, at the institute for advanced medical training. As a rule, this happens after about 5-7 years of practice. But the chief surgeon from Poltava came, and either he was persuaded, or the situation was such that there were no young surgeons in Pyriatyn and they decided to strengthen the staff. So I go to Kharkiv.

In Kharkiv, I had a manuscript at the “Prapor” publishing house. I had sent it there earlier. I decided to take it back because there had been no response for a long time. I go to the publishing house—it’s lunch break, they say: “Your manuscript was sent to your home address.” But a short man (I don’t know his last name) comes into the office and shows me a review. I read it: “The poems are nationalistic, anti-Soviet.” And it was signed by one of the writers—Lopatin. It was an editorial conclusion or something like that. Of course, I could have taken that piece of paper. But for some reason, I didn't. I came home—indeed, a folder had arrived by mail, with a completely different cover letter: “Rework the manuscript.” They pointed to some pessimism in one or two poems.

In Kharkiv, they wanted to take me from these courses for research work at the Institute of Neurosurgery. But when I went there and saw it—it was worse than a prison! Extremely high walls, all surrounded by barbed wire at the top, and it looked like it was all electrified. I thought to myself—no, this won’t do. To implant electrodes in someone or what?

I return to Pyriatyn. I returned with my wife, whom I met at these courses. The head doctor here was very indignant: “There will be no work for you, go to the district hospital as its head.” I say: “But wait, I’ve completed advanced training as a surgeon. Here are my excellent grades, they wanted me at the neurosurgery institute.” “We're not interested, go where I tell you. There will be no place for you or your wife in Pyriatyn.”

I had to take a job at the railway hospital at Hrebinka station. Six months later, certain authorities find me again, summon me, and say that as long as I live here, I will never get an apartment. I go to the Ministry. They send me to Boryspil as a surgeon, but they won’t give me an apartment right away, I have to rent. But in Yahotyn, they give an apartment immediately. I return to Yahotyn and get a job as a surgeon.

But six months passed—and I found myself in a wave of unbearable life. They started seizing my medical records, and they ended up with the prosecutor.

I remember one incident: on Victory Day, the head of the department, a war veteran, goes around congratulating everyone, especially the ward for invalids and participants of the Great Patriotic War. He congratulates them on the holiday, and I silently walk behind him. After lunch, the prosecutor summons me: “Do you know that a word can heal?” I say, “I know that perfectly well.” I didn’t know why he had summoned me. But there had already been a denunciation that I had not congratulated the invalids in that ward—he told me this after seven hours of interrogation. I left his office around 11 p.m. I said, “Wait, a word may heal, but we have a chain of command. The department head was offering congratulations. You have to respect the chain of command.” “You should have too.”

There was another shocking incident. I had an invitation from the Writers' Union to the Shevchenko March holidays in Leningrad. Yuriy Kobyletsky from Kyiv was going (he died shortly after). Roman Lubkivsky was in that group. Everything was fine, we were met there by Petro Zhur—a Shevchenko scholar who had written several books about Shevchenko. I return home—the head doctor takes me to the prosecutor's office because, it turns out, I violated all labor codes and should be fired. I say, “How so? You let me go yourself!” “But you asked to go to the Academy of Arts!” “That’s right, I was there.” “But we thought that was in Kyiv.” “How could you not know that it’s the only one in the USSR, this Academy of Arts? And you studied in Leningrad!” Well, he never forgave me for that as long as I worked there.

When I was working as a doctor in Yahotyn, Taras Melnychuk came to visit me. I had known him a little earlier because he used to come from the Ivano-Frankivsk region to the Writers' Union in Kyiv. I was visiting from Crimea at the time, and that's how we met. Then he disappeared… And the last time I saw Vasyl Stus was on the day of his final arrest. He was going up the stairs at the Union. As I later understood, these well-built fellows were taking him to the Party committee… (It's unlikely that Stus was at the Writers' Union on the day of his arrest, May 14, 1980, let alone at the Party committee... – V.O. Here, maybe I am making a mistake about the time. – D.Sh).

V.O.: You say final—he had two arrests.

D.Sh.: The second one. And I was going down. Why was I there? My collection had been “axed” at the “Radyansky Pysmennyk” publishing house. I had as many “axed” collections as I had published ones. For example, my first collection was supposed to come out around 1965 in Crimea. But until the “Molod” publishing house in Kyiv published it, I couldn't get published in Crimea. Every year I was included in the publishing plans, but to actually print a collection—never. I later understood: I could never have published a collection if I had relied solely on the “Krym” publishing house. With this, they drove me almost to madness. It was my first collection, a person worries… It was such a refined terror—anyone who has gone through it can imagine what it was like.

To continue about Yahotyn. Andropov came to power (General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee from Nov. 12, 1982 to Feb. 9, 1984). At that time in Poland, “Solidarity” was expanding its activities. And with me, periodically, and frequently under Andropov, they began to seize medical records—and I had to report to the prosecutor. It's a good thing I had no deaths during that period; none of my patients died. If a patient had died, I'm sure they would have incriminated me in some crime.

I remember, around that time, they inform me in the operating room that some artist is running around the clinic asking for the surgeon who walks around in an embroidered shirt—can you imagine? I go down, we meet. Volodia Kalnenko, an artist from the Leningrad Mukhina Higher School of Art and Design. He says, “Here I am with my bandura, I was in Pereiaslav.” And he shows me a beaten-up bandura. He comes home with me. I was living alone at the time. My wife had left with the children to her parents' place beyond Chernihiv. Why? Because she filed for divorce. Two small children—and she files for divorce. All this was caused by the circumstances that the head of gynecology, Zhanna Karlivna, lived next door on our landing, and several times when I came home, she would open her door and shout for the whole building to hear: “The nationalist has arrived!” At first, I paid no attention, I thought it was some kind of joke. Then I made a remark to her at work, but eventually, I understood that all this was connected to the troubles in our family life. My wife is also a doctor and apparently communicated with her. When I came home from work, she was always in tears. Well, what can you do—a divorce is a divorce—she grabbed the children and left. And Kalnenko and I came to my place. We cooked some kind of kulesh, some tea, and Volodymyr suggests the idea of going to Leningrad for the Shevchenko celebrations. Perhaps he was the one who pushed this matter forward, leading me to join that group.

When I returned from Leningrad, it was very hard for me to account for it. Why? Because I was supposed to go to Kyiv, but I went to Leningrad—that's one thing. And I stayed there a few days longer than I was supposed to; they were waiting for me here. But most importantly, no one knew where I had disappeared. They were searching for me all over Kyiv. When they summoned me to the Pereiaslav KGB (they had a regional office there), some Sereda told me: “You ended up in a special group, they were watching you even in Leningrad.” And what did I do there—I read poetry, nothing else. And ate varenyky, like everyone else, when we were invited. “In any case, you are a nationalist.” “Because I read in Ukrainian?” “No, you even operate like a nationalist.” “And how is that?” “Your sutures on wounds are peculiar.” “What, are they stitched in cross-stitch or with Ukrainian patterns?” “You want to know too much! You'll find out!”

But my wife returns. After the divorce, after she no longer even used my last name—she returns. The children run in first, I came out and said, “Run along, you're home.” And she stays: “But what about me?” I say, “Do as you wish.” We no longer had a family life—the children lived in the middle room, she was there, and I was here. I started locking my room. The lock was broken several times. One day I come home—the lock is broken, and I'm summoned to the district party committee to see Porokhniuk, the first secretary of the district committee. “They found a weapon at your place.” I say, “A lot?” “You should know.” “This is the first I've heard of it.” They charged me with possessing a rifled weapon—a homemade pistol and some kind of rifled parts. They didn’t let me leave the department.

V.O.: Where and when was this?

D.Sh.: In Yahotyn, 1983. On October 25, I was summoned to the district committee, and on October 29, I went to the police station. But it wasn’t the police—it was state security investigators. Everything was already formalized there, and I didn't get to go home from there. I spent two nights in Yahotyn, and then I ended up in the temporary detention facility in Pereiaslav. In Pereiaslav, we stayed for two or three days, and then they put us in a “voronok” (paddy wagon), me in a “stakan” (a tiny solitary cell inside the vehicle), and drove us to Kyiv.

V.O.: You say “us”—who was with you?

D.Sh.: They were transporting a group of arrestees. They gathered a group and took us. I ended up in Lukyanivka. They held me sometimes in solitary confinement, sometimes in cell number forty, sometimes in ninety. Different groups, different criminals, there were stool pigeons there too. I understood this later, analyzing it all. They knew everything in advance, even knew how it would end for me, how much I would get, and where I would serve my time. I stayed in Lukyanivka until 1984.

As soon as Andropov was wounded, the trial took place. He died sometime at the beginning of the year. (The trial took place on January 11, and Andropov died on February 9, 1984. – V.O.). For me, it all passed like a terrible dream. I had no sleep, nothing—just this solid mass, I was in this sticky mass of events. I had an official defense lawyer and two public defenders from the Union—Volodymyr Zabashtansky and Petro Zasenko were my public defenders. They were at the trial. The trial was over very quickly.

V.O.: What level of court was it—regional or district?

D.Sh.: Yahotyn District Court. They had already stitched together completely different charges against me.

V.O.: And what was the charge—possession of a weapon? Article 222, right?

D.Sh.: I don't remember the number, honestly. But if Andropov had still been in power, they would have charged me with murder and whatever else they wanted. They had that pistol. They could have done anything with it and proved that I did it. But these are all conjectures. I return to work…

V.O.: And what was the court's verdict?

D.Sh.: A two-year suspended sentence. (According to the verdict of the Yahotyn District Court of the Kyiv Oblast on January 11, 1984, D. Shupta was punished under Art. 222, Part 1 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR with two years of correctional labor without deprivation of liberty, with 20% of his earnings to be withheld by the state at his place of work. His “accomplices” Vasyl and Valentyn Yevsennikov, who are listed first in the verdict—implying greater guilt—were sentenced under the same article to two years of imprisonment, suspended with a probationary period of 2 years and transferred to the supervision of their work collectives for re-education. Such verdicts were issued by Soviet courts when the guilt of the accused could not be proven, but it was necessary to “justify” the groundless arrest. – V.O.).

V.O.: So, some guilt was still recorded in the verdict?

D.Sh.: The pistol, and that's it. But at the beginning, as soon as I was arrested, they charged me with possession of weapons, ammunition, a bag of dollars buried somewhere I don’t even know where, several radio stations buried somewhere on the border, and ties with “Solidarity.”

V.O.: Amazing!

D.Sh.: The “weapon” emerged after all these accusations were dropped following Andropov's death. Well then—two years. And I had already served several months, so they counted that.

V.O.: How many months did you spend there?

D.Sh.: Four months, three of which were in solitary. They could have put me in solitary right away or at the end and not let me out. But they probably moved me to those cells where the “stool pigeons” were. That's their tactic.

After that, I can't get a job. I go to the Ministry again—no work. But I lost not only the opportunity but also the ability to work as a surgeon. I fought for a surgeon’s job to restore my reputation. But I never managed to achieve that. I became a surgeon-expert for the VTEK—the medical expert commission. Then I was on a VTEK course in Kharkiv. They took me to Kyiv, to the regional VTEK, in surgery. A situation had just arisen where a surgeon's position had become vacant.

I commuted by electric train from Yahotyn to Kyiv. You get up at 4 a.m., and you get back around 11 p.m., or midnight—the buses aren't running anymore, and I still have about three kilometers to go from the station to my home in Yahotyn. I started staying overnight with acquaintances in Kyiv—and they put out an all-Union wanted notice for me!

The alimony terror began. It’s impossible to describe what I went through. I was with my family until I had paid all the alimony. My older son went into the army, and the younger one, a year his junior, entered a technical college. And then I never showed up at home again. There, of course, all my manuscripts perished, and very, very much else was lost.

Was it any easier for me after that? Probably not, because even now I still feel the consequences of all this. For example, I'm not registered in Odesa. I'm registered in my village in the Poltava region, in my father’s house. I’m here—and everything there gets robbed 5-7 times a year. I come, lock up, board up the windows—and it's the same thing over and over again. Methodically, you see? The robbers know there’s nothing there, but the searches continue all the time.

What else can I say? Now, of course, there is a possibility of being published, if there were sponsors. But that's probably a problem for you too. I had hoped that Mykola Kozak—we had a conversation—would get some of my papers. I wrote to the KGB in Odesa, in Kyiv, in Crimea. The answer was always the same: “No cases were ever opened against you.” Yet I know for a fact: before I left Crimea, they summoned me to the regional KGB and showed me my poem “Teresy” to identify if it was mine. I said, yes, it's mine, I didn't deny it. The second case was handled throughout my years of work in Yahotyn by the head doctor. It was denunciations, denunciations, and more denunciations. He collected them, and what’s more—he provoked them himself, so that people would write them. He had a separate folder in his safe. There, in Yahotyn, there was a Major Vasyl Vasylyovych Tereshchenko, who was gathering materials on me. There are many such facts, and I would like to get this matter sorted out: am I a victim of repression or not?

I couldn't work in my profession after that. After Lukyanivka, I have two vertebrae jammed in my back, between my shoulder blades, I lost my sight and hearing, and many other things…

V.O.: Why? And these scars on your fingers—what are they from?

D.Sh.: The result of interrogations.

V.O.: And what did they do to you?

D.Sh.: They slammed my hands in the door. And the doors there were such that the bone would remain intact, but if they twisted it, the skin would peel off like a glove. My hands were like that.

V.O.: Wow! Such methods were not often used in our time!

D.Sh.: But I had to endure it…

V.O.: And do you remember the last names of those investigators?

D.Sh.: I remember Kolosovsky—young, about 20 years old, at the KGB in Yahotyn. After that, I don’t remember anything. I have a brother—no visits, no packages, nothing during my entire time in detention.

V.O.: And so, you’ve appealed to various institutions—and they all reply that there was no case against you?

D.Sh.: “You have a criminal record, for a weapon.”

V.O.: Ah, criminal record, a weapon.

D.Sh.: That was the last time I appealed—and then I just gave up. Besides, there’s not a single Ukrainian there, the language is Russian—who am I supposed to appeal to?

Dmytro Shupta, February 12, 2001. Photo by V. Ovsiienko.