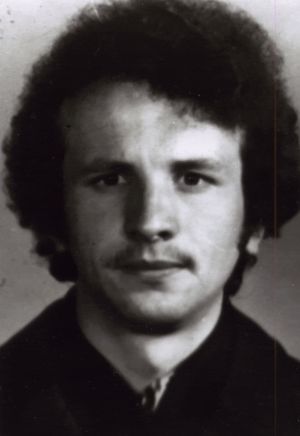

An Interview with Mykhailo Mykhailovych YAKUBIVSKY

(On the KHPG website since March 1, 2008).

V. V. Ovsiyenko: December 6, 1998. Vasyl Ovsiyenko is interviewing Mykhailo Mykhailovych Yakubivsky at his home. Kyiv, 8 Teremkivska Street, apartment 64.

M. M. Yakubivsky: I, Mykhailo Mykhailovych Yakubivsky, was born on November 21, 1952, in the village of Verbivtsi, Ruzhyn Raion, Zhytomyr Oblast, into a peasant family.

I barely remember my father. I was only about three years old when he died. But I remember well that he was a carpenter, how he crafted things, how I would help him with something when he was building a new house. That was in 1955. He had surgery in the town of Berdychiv. As I can judge now, it was a botched operation. Perhaps it shouldn’t have been done at all. Because when my mother went there, the doctors looked at her with guilt in their eyes. Father was only 45 at the time. I have already written in my memoirs that I felt very good with him. I felt it then as a child. Even my mother was surprised.

One time, my mother was sewing on a machine. We had a Singer machine. Its still there. I, a little boy, was beside her. And Father—I could see him through the window—had gone outside (this was already in the new house), and wearing a sheepskin coat, he went down toward the Tasmia river. And I said something like: “Mama, is Father going to die?” And she replied, “What are you saying?” Well, a child, about three years old. I remember when Father died, a candle was burning. That was my first pain—seeing the candle flame. Another thing: I was running on the bench while Father was in the coffin. And then I kept pestering the gravedigger: “You’re the one who buried our father.” Such was a child’s mind—what was that man guilty of?

So that was my childhood, without a father. My mother’s maiden name was Onufriichuk. Her mothers was Kukharenko (?). And there were no other Yakubivskys in the village. It surprised me—the Yakubivskys. But it was probably my grandfather who moved to the village. Or rather, not my grandfather, but my great-grandfather, because my mother told me that he had moved here. Perhaps he was of Polish descent. There was some landowner, and my great-grandfather worked for him as some kind of assistant. That landowner even gave him land. This was for my great-grandfather Vitsko. Vitsko means Ivan Yakubivsky. Of course, I should look into the archives…

I know they really disliked the Soviet government. My mother said that when Lenin came to power, they had their own fields and worked them themselves. They didnt have hired hands, but seasonal workers. And seasonal workers—that already meant they were kulaks. But they paid them! My grandfather came home, held his head in his hands: “My God! This plague has arrived! What will happen?” There was such a premonition of disaster. Then came the NEP, and people’s lives improved so much. Grandfather Herasym—my fathers father—built a very beautiful house, under a tin roof, as they used to say. They had a homestead, many buildings: for grain, for the thresher...

In 1929, collectivization began. When my mother married my father, they lived in that house for another week or two. And then she, along with my father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, were thrown out of that house, and it was turned into a mill. I know the spot in the village where that house stood. My great-grandfather lived in some kind of shanty (?). He died in 1933. And Grandfather Herasym, my fathers father, went to the Donbas during the famine to look for bread. As one man from Verbivtsi who went with him said, my grandfather died and was thrown off the train. Where that happened is unknown. Where my grandfather’s and great-grandfather’s graves are—no one knows.

Well, my father was taken into the labor army. They told my mother (she was 16): “What do you need him for?” He was his parents’ only child. (There were other children, but they had died). Father hated that government his whole life. He was always well-dressed, in boots, being the only son. He would be walking, and the Komsomol members would say: “Look how he’s dressed! Let’s kill him and take his chrome leather boots.” So they took him to the labor army. He was there for a short time and then refused to serve. He was the kind of man who had only finished four grades but was a very good carpenter he could make anything by nature. Father returned from that army and said, “I can’t stand it there I’m going to Crimea.” Everyone tried to dissuade him: “Come back!” But Father said the labor army was worse than prison they tormented and beat you there. We had an old man in the village called Humen. He had been to Canada, to America: “Mykhasko, go back, or you’ll be in for it.” But Father said, “I’m going to Crimea.” A cousin or some relative lived there in Crimea. “There,” he said, “I will do carpentry.” As for this labor army—I dont know where it was, maybe in Zhytomyr. He refused to serve there and deserted from that army. In modern terms, he was a deserter.

He got ready, but before he could even reach the Koziatyn station, they arrested him there. He was given six years in the camps... They told my mother: “Go to him.” Mother visited him there. She was young—it was 1932, so how old was she? She married at 16. Then his mother, Palazhka, went. (I never knew them—neither grandmothers nor grandfathers. Only my mother). His mother, grandma Palazhka, went with a sheepskin coat, saying it would be cold there. She brought food. She arrived, but he was already gone. Where he was—no one knew. And those clothes disappeared somewhere too.

And how was it for my mother? Kicked out of her house, she wandered around with a little boy, Mykola. His name was Kolia. Just like in Shevchenko’s works—from one house to another, to a third… No one would take her in, because she was the wife of a kulak. “You needed that Mykhasko like I need a sore,” said one man with tuberculosis who worked in the village council.

And then came the Famine. She managed to stay with her sister for a while. The sister had a very strict husband. That was my aunt she’s deceased now too. She used to say, “What saved me during the Famine—they took everything—was a sack of millet.” She hid it right in the snow. And so much snow had fallen... There was cannibalism, she told me. I have a poem about it, which I wrote in 1971. Well, I didnt write that it was in 33 because I wanted to get it published I wrote in the year N, so that if they came after me, I could say I meant some ancient case. My mother was young, so she was afraid they would slaughter and eat her... We had such cases... There was one woman, whom I describe in this poem, who slaughtered her neighbor... These are horrific things. My mother said that half the village was lying dead. And, as everywhere, those who collected the dead were given some bread. It was profitable for them. Sometimes a person was still alive, and they would say, “Ah, we’ll take him, so we don’t have to come back for you tomorrow.” This happened all over Ukraine we read about it now. It was a planned campaign.

And the homestead where we live now, my mother bought it for a bundle of millet—a little “Shevchenko-style” hut. The homestead where I was born is near the forest. Under it, the ground is full of mollusk shells. They were collected in the spring or summer of 1933 from the Rastavytsia River, boiled, and eaten. I don’t know how they survived.

I’m telling this briefly, but I want to say it all.

Father returned in 1935. He told Mother that when they were transported to Siberia, their heads would freeze to the walls. The boxcars were packed to the brim—up to the top bunks, to the very ceiling. They threw them that frozen bread. It was impossible to break. And then they threw out the corpses. He was 22 when he was sent there (he was born in 1910). He was already completely bald. And when he got out of the wagon, he had to move his legs with his hands, one, then the other. It was to the Ussuri region, Bamloha station. Mother wrote him letters there. He worked as an orderly there, having gotten into a course with a good doctor. Besides, my father was also a craftsman, and that saved him. (And in the village, many of his creations remain with people: a weaving loom, furniture, and he did a lot of work in houses. He was a wonderful craftsman. There was no other like him in the area...)

They counted a year there as two for him. He only served three years. He sent letters to my mother. To avoid paying exorbitant taxes, my mother was forced to get a sham divorce. That boy, Mykola, died. My mother had three other children who died. There was Vania—after my father returned from the war. Before me, there was another boy, Lionia, born in 1950. He was about a year and a half old when he caught scarlet fever from the neighbors. He needed penicillin, which was available at the hospital, but they didn’t give it to him, giving it instead to some official’s son. That little boy Kolia died. Mother remembered how he walked out of this house and cried, “Mama, Mama!”

My mother endured a lot. When my father finished his term and was released, he wanted to move her there. Mother had already gathered all the documents, but he wrote: “Don’t come, I’m returning.”

My mother remembers how he came back: everything on him was prisoner’s garb—a jacket, those kinds of pants. It was sometime in the summer. They were young, it was 1935, my mother was only twenty. Father returned and said to her, “Oh, you’re still like a girl!”

My mother raised a pig. And these activists come: she hadnt paid some tax—so they drag the pig out. And my fathers sister says to him, “Why are you staying silent?” And he says, “You know, I’ve already seen a few things, I’ve traveled the whole vast country. I’m not the master here.” In other words, this whole act was designed as a provocation. And what could he say? Such was the atmosphere...

Father worked on the collective farm. They sent him to some courses in 1941. He was somewhere in Volyn, in Lutsk—he had to study for some position. The military commissariat sent them. And then the war started. So, he said, they jumped out in their underwear—they were being bombed on June 22. He returned home. There was nowhere to go beyond Koziatyn, as the Germans had already occupied it. So, until the Soviet troops arrived in late 1943, my father was in the village.

What did he think? The whole nation thought—our own government has come. Under the Germans, churches were reopened. About that house—my mother said, Don’t take it! Don’t touch it! Because their own house had been taken for a mill. The village elder said, “It’s their house.” Rightly so—they had built it themselves. Father had already fixed everything up, the housewarming was supposed to happen, they were about to move in. And then the Reds returned, and Father got scared. My father was not a policeman or a partisan. He was afraid. There were some partisans in our village… In other words, bandits—every fellow villager would say so. Because they drank and caroused with the girls. The village elder brought them bread and meat. Because the people brought it to the elder. And when the Reds were advancing, they, apparently to cover their tracks, killed some German. I dont know what kind of German. Kuznetsov did the same thing—he would carry out acts of sabotage and claim it was the Banderites. Then the Germans would kill peaceful civilians. The same thing happened here. For that, the Germans burned the neighboring village of Sokiliv Brid, burned children, like in Khatyn. I mentioned this once. They wanted to burn our village too, but the Reds were already advancing.

Why am I saying this? Those partisans killed many people, they simply slaughtered the elder and a few others, their own fellow villagers. These were cruel people, perhaps they had been greatly abused. Were these people guilty before the Soviet authorities? How was he guilty if the village had elected him? It was terrible—they cut off ears, noses, and threw the bodies straight into the river. This is how they tried to curry favor. These were “our own”—we’re not saying it was some outsider. They were our own. Father was afraid they would get to him, these partisans. He was afraid for this house. So he never moved into it. Well, they didn’t touch Father, it’s true. When the Soviets came, no one among the neighbors said anything bad about Father he had done no one any harm. But there was some NKVD unit asking who he was.

After that, he went to the front lines. My mother even visited him somewhere as far as Koziatyn. Then a death notice came. They thought Father wouldn’t return. But then a letter arrived saying he was in the hospital.

The reason I’m telling you this is because it was talked about during my childhood. My older brother, Vitaliy, was born in 1936. He now lives in Kyiv, and his poems have been published (Died on January 3, 2005. – V.O.). Anatoliy, from 1939, is more inclined towards agriculture, beekeeping. I also have a sister, from 1941. And then me, the fourth—the four of us who survived, four children. So when my brother Vitaliy was studying journalism at the university, he would bring home books. This was already after Stalin, after the 20th and 22nd Party Congresses. I remember we had an old man named Mykola. His nephew was the executive secretary of the newspaper *Silski Visti* (“Village News”) at the time. He was such a commie (we don’t have contact with them) he’s retired now. This was around 1959 or 1960 I hadn’t started school yet. They still celebrated Stalin then and didnt tear his picture out of calendars, even though he had been condemned. Well, I tore out the calendar page with Stalin. That was my political act. Because that’s all we talked about at home.

I remember that the first words I learned to read were “Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev.” Thats interesting! Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev! I also remember him speaking. I was born at the end of 1952, but I remember Khrushchevs speeches. He liked humor. He would say something, and after every sentence, as they say now, stormy applause. And he would do this thing: ahem-ahem-ahem. He would clear his throat. How old was I? Eight?

I was very drawn to literacy. My brother brought a primer, I remember, then Shevchenko... I dont remember when my older brother Anatoliy went into the army because he left earlier. My memory couldn’t capture that. And when Father died, he didn’t come from the army for the funeral. But then, I remember, it was spring, the snow had melted. He comes out of the forest, with blue epaulets (he served in the air force), and picks me up. I thought, “Oh, so I have other relatives.” The thing is, all the neighbors on our Lisova Street had fathers. But I didnt. My mother was so beautiful. She sang well and was a hard worker. She said, “Maybe I’ll somewhere…”—some fellow wanted to marry her. And I’d say, “What are you thinking? I’ll chop him up.” Well, I was a feisty kid…

I’m talking about my brother Anatoliy. My brother comes out of the forest, picks me up... And Vitaliy started bringing little books, by Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko... I remember those children’s books. I started to read. When Anatoliy was still in the army, I wrote him letters before I even started school. I couldn’t write in cursive yet, so I wrote in block letters. I have some of those letters somewhere. I collected them its all so interesting.

You can’t say my childhood was very hard. I did well in school. It was even getting boring for me. Truthfully, I wanted to go to school earlier. I was two months short of being seven. Back then, they took you to school at seven. And that probably would have played its role too. Because the boys from my street went.

I told you who we were. A widowed mother, four children, it was hard. The only thing that saved us was education. Vitaliy studied journalism at the university, Anatoliy at the agricultural institute. And I came later.

You mentioned that Mykola Rudenko believed in Stalin. I was tearing down Stalin. But Lenin... You know, so much was written about him, how good he was. But I saw the discrepancy in the village. I analyzed things. Id look at the collective farm chairman—the power he had! Two people died practically because of his fault. I analyzed everything… My brother should have foreseen what this could lead to… For example, in 1967, he brought home a book by Vasyl Symonenko. I learned lines from it like: “_Хай мовчать америки й росії, коли я з тобою говорю_” (“Let Americas and Russias be silent when I speak with you”). On the one hand, there was the dreadful officialdom, and on the other... I used to visit Kyiv back then. For me, a village child, Kyiv was so magical! But what struck me was that people there didn’t speak Ukrainian. That we were some kind of outsiders there, humiliated. The reason I mentioned my last name—Yakubivsky. Maybe there’s a quarter of Polish blood in me. Maybe it comes from the Poles, or maybe it’s in every person’s blood… I had no idea what lay ahead for me, and yet I had already drawn such conclusions.

Then, in 1967, I was the top student in the school. I remember in 1966 I was the winner of the checkers tournament of the *Zirka* (“Star”) newspaper (and this from a remote village we didnt even have a road back then, they built it later). How did I get into checkers? I generally loved books. I still do. For me, a book was something sacred. Well, the calendars had checker puzzles, with the solution in the next issue. I solved them. And then there was a contest in the pioneer newspaper. I solved those puzzles in a flash. And master Kaplan congratulates me, probably a Jew: “My young friend, you solved it correctly.” Then a third-class rating, then second-class. It was printed in the *Zirka* newspaper for 1966 (you can find it in the archives): “Mykhailo Yakubivsky from the village of...” There were many winners who had solved all the combinations. Later, the district newspaper wrote about me and the 100-square checkers, which were called Russian. I was already thinking there would be a prize.

But then, you see, another problem arose—the national one. I recited Symonenko on the stage of the village club. We had a school principal... I mentioned the head of the collective farm—Nykyfor Avakumovych Dymchuk. And the school principal (she’s still alive) is from Ohiivka. Maybe she’s related to that Fedorchuk—she resembles him in character. Ohiivka is where that super-executioner Fedorchuk was born, who later sat on the KGB throne in Kyiv and even in Moscow, for the entire Soviet empire. He made quite a career for himself. We know how those careers are made...

I had a normal relationship with the school principal. She was a teacher of Russian language. And then I started (I have some notes about it somewhere): “Why this song? Why aren’t we singing in Ukrainian? Why is there Russian in it?” Well, thats when she started: “Who’s been feeding you this stuff? Give me your brother’s address!” At that time, she used to walk around at night with a small-caliber rifle, as they called it. She would shoot at anyone who tried to steal the first strawberries. I mentioned our village was remote. We once had a church—probably the best wooden church in Ukraine. Then the Bolsheviks destroyed it... And so she would shoot into the darkness… She was, as I understand now, a KGB agent. And a village, you know, is a community. I now know that probably every communist was an agent-informant. Well, a school principal even more so. And so I got on her bad side. In 1967, she refuses to admit me to the Komsomol. Me, the top student in the school!

Then in 1968, I wrote an essay about Shevchenko (I still have it). And my grades—from first to eighth grade, all I got were straight As! In it, I wrote that there will be a Ukraine, a Taras Shevchenko, high burial mounds, the spirit of Khmelnytsky, Ostrianyn, Bohun... No one taught us that in school! They taught us songs about Chapayev, about Moscow. And here was this... She sensed it. She ordered that I be given a four [a B grade]. For me, it was a tragedy. It had nothing to do with her, as she taught Russian, but...

Well, 1968 was the year Oles Honchars novel *The Cathedral* was published. I read *The Cathedral*. And I hadn’t yet finished Borys Antonenko-Davydovych’s book ( *Behind the Screen*?). You analyze these things later… My brother and I would be walking in the woods somewhere… We have a forest nearby. Hes 16 years older, so he should have known a little… I found out later: Ivan Makar, a member of parliament from the Lviv region, he says that his mother was even afraid to teach her child the song Oy u luzi chervona kalyna (“Oh, the Red Viburnum in the Meadow”). But my brother—did he think I wouldnt fall under that crosshair? I would express such thoughts to him, that we would give our lives for Ukraine. It felt so sweet in my soul! I now think that if everyone rose up today, I would go. But when you go alone… I later saw in life that when you’re alone, those very same *khokhols* [a derogatory term for Ukrainians] laugh at you.

I was supposed to go to another school, because ours only had eight grades. My brother said there would be boys there just like me—there were no such boys. I looked for them, asked to be in a different class—none.

And here, I had a revelation! I was well-read, you see. I had read Gorbovskys *Hunters of Ghosts*. It explained the forces that enslave people: power, wealth, money, love, and for those who want to live long—health. Well, I was young. I was making my plans. Could it be that we wouldn’t build Ukraine? My brother said that the future of humanity could be determined mathematically—well, then Ill become a mathematician. And I shared my thoughts...

Then, they sent troops into Czechoslovakia. The invasion of Czechoslovakia shocked me deeply! I skipped school one day… Nowadays, they’re making a national hero out of Shelelst. Well, certainly, in comparison with Shcherbytsky… But, thank God, my memory is still good! I remember it was in the morning. The anthem played in the morning—and Shelelst was speaking. It was around the end of August, the 21st or 22nd of August, 1968. He said there were enemies there, that our troops had been sent in. Ive hated Shelelst ever since, to be frank. I remember that speech. How he said that in Prague there were counter-revolutionaries, our troops had been sent in, and with such a voice...

At that time, I made a discovery that still surprises me. That Pavlychko is lying, I’m saying it straight. And Drach. They all lied: “We didn’t know who Lenin was.” How did I know at fifteen? It’s not true that the Central Rada was an enemy. Did they want bad things? They wanted Ukraine’s independence, our own state. And Lenin called it the Central Betrayal [a pun on Central Rada]. You see, I have a critical attitude toward life. And the Marxists themselves say that everything should be questioned. And that same Lenin destroyed our state! I’m amazed that Pavlychko didnt know this, that another one didnt know. They knew it very well, they just served the regime! Why doesnt Stus have a single poem praising that scoundrel? And I dont have one either. I don’t write poems now, but I have poems—quite the opposite. I felt it with a childs heart and understood who he was. I couldn’t think that way about Lenin!

Of course, when I went to the other school, I shared my thoughts there. I asked to be in another class. I didn’t even know what a psychiatric hospital was back then. And then I couldn’t sleep all night—it was such a shock! And then Shelelst made his speech. I even got a little scared. I thought: “My God, I’m living in such a state! Why are they lying on this radio? Its horrifying! They’re criminals, they’ve occupied Czechoslovakia!”

They didn’t take me by force right away. There was a clever trick: “Go see a doctor.” I had missed school then. Well, I’ll go, they’ll give me a note, and that will be my excuse for not being in school. I go in, and they ask: “What happened there, what?” I just hadnt slept all night. And Im afraid to admit it. I wrote a letter to my brother then. If my brother had come, everything would have been different. But my brother didnt come. True, my brother and I had talks, but not about Lenin. Lenin was like a god back then. Now you can tell jokes about him...

To make a long story short, they say: “Well, we’ll check you now.” I didnt understand Russian very well back then. When someone speaks Russian to me, I imagine a board studded with rusty nails. I remember when we were herding cows in the summer, and some city folk would arrive and speak Russian, we would just beat them for speaking Russian. And here this doctor, Bondarenko, asked in Russian, “_Vas toshnilo?_” (“Were you nauseous?”). I now think that was the first time I fell into the beast’s maw. I say, “Yes.” I didn’t know what the word “_toshnilo_” meant. Because Russian was not in use among us. And even now, in my village, the Ukrainian language is perfectly preserved. The doctor says they will check me now. And from there they sent me to the Bila Tserkva psychiatric dispensary. This doctor who detained me handed me over to a woman—Lashchuk, Halyna Ivanivna. Did she call him specifically? In this Bila Tserkva psychiatric dispensary, she would thrust paper at me to write about myself. She is still alive. I have her address (I know she’s a scoundrel).

I thought I was the only one who had figured it out! I couldnt tell anyone anything. And she says: Write what you think. And the other patients: You have to write... I remember I started to write something. Just a little. But at the end—a poem by Lermontov. I thought: if I start writing, I’ll sell out my brother. You remember those times, dont you? And my brother didnt come. Why didn’t I run away from that psych hospital? I would have found a way... But I didnt know what they were preparing for me.

There was one teacher there. They were giving him glucose injections. I started telling him about Czechoslovakia. Maybe he was a snitch? I don’t know. Well, what is a psych dispensary? In those days, people came there to rest. I was 15, almost 16. The food was good. I observed that teacher. I’m not saying Im a psychologist now, but I have seen all sorts of people. When I mentioned Czechoslovakia, that speech by Shelelst, he said, “Oh, you’re 15. At that age, our guys are such blockheads! And you think like this!”

I thought I’d rest there for a bit. I thought, Ill stay here a little while. And she was so persistent: Write what you think. And the others said: If you dont write, shell send you to Glevakha! And there!... My brother arrives. Well, such a blockhead, to use the Russian word. Clueless. Hes talking to me through the toilet window. And that doctor, Bondarenko, for some strange reason is here as a patient. Was he on a check-up? I think so. And my brother says to me through the window, Bohdan Khmelnytsky was here in Bila Tserkva! There will be an independent Ukraine after all. And this doctor, the one who gave me the referral from Bila Tserkva, Bondarenko, had somehow come there as a patient himself. I see him watching me. He would walk around in that striped robe: _Malchik, malchik, kak dela?_ (“Boy, boy, how are you?”). And I would shy away from him... And when my brother was saying that to me, this doctor was right there, in the toilet. He was either smoking or something. And my childs heart feels... I was a very secretive boy in general. I thought: “Well, brother, why did you have to blurt that out?”

They kept asking me what books I had read. This Halyna Ivanivna Lashchuk, I remember: “_Shto on chital?_” (“What did he read?”). So, I was an interesting patient for them, I understood. “Write.” “Well, what should I write?” “Write about your brother.” Well, I’m no Pavlik Morozov. I didnt write anything. And one day she says: Listen, there’s your brother…”. They see Im a village kid, what defense do I have? And so she goes: “Misha, you will go to Kyiv. A professor will examine you there.” And by the way, I was afraid they would find out my thoughts. I saw something written there: “Biletsky - hypnotist.” I thought they would hypnotize me and discover my anti-Soviet sentiments. He said he was from the KGB. Meaning they could do anything. A prison is a prison, you know...

Well, since I didn’t write, they decided: “Misha, you will go to Kyiv. A professor will examine you there.” And frankly, I wanted to share my thoughts with someone. If she had spoken Ukrainian, I would have told her about my doubts. But I could see—she was a stranger. I’m telling you as if before God, at that time I even had a hatred for those who spoke Russian! Now I understand, I’ve been through it, that there are Banderites, there are nationalists, theres the slogan “Ukraine for Ukrainians.” Well, back then they pushed me to such a state. We are on our own land. So why should we be so nice? The Jews are nationalists, the Germans are nationalists. What about us? I had such hatred then. The way out was clear. I thought this was some great discovery… Even my older brother never said anything to me about Lenin. Back then they said: Lenin was good, he gave Ukraine all the rights. And I had figured this out. She says: “Write!” But I didn’t.

I had heard what Glevakha was, that it was something terrible, I knew it was an asylum. But here, the conditions were normal. I remember there was a very beautiful girl there who always brought me grapes. So the community was normal. But this Lashchuk: “_Vot ty poyedesh, professor tam tebya posmotrit, i potom sestra zaberet tebya_.” (“So you’ll go, a professor will see you there, and then your sister will pick you up.”). So she was lying to me vilely. But I didnt know she was planning such a vile thing. When I went to say goodbye to the boys I played checkers with, they said, “Well, write letters,” with a sneer, you understand?

As I rode in the ambulance, a madwoman was screaming the whole way (its a long way from Bila Tserkva to Glevakha, almost a hundred kilometers). It was October, I remember, they were harvesting sugar beets from the fields. Were driving on this highway. I see us turning. And this woman screamed the whole way—it was terrifying! But in general, in the psychiatric dispensary, there were more or less normal people. Well, there was Vania, he came up to me when they sent me away: Youre screwed! Actually, he said it more harshly, but that was the gist of it, youre screwed.

To make a long story short, they brought me to Glevakha, to the childrens ward. I see this Glevakha—its a disgrace for me! I understood that this would be a mark on me for life! But I didnt give up there. There was a children’s doctor there, Zhanna Arkadiyivna Koretska. As far as I know, that ward doesn’t exist anymore. And this was October 1968.

My brother brought the essay I wrote about Shevchenko for my eighth-grade graduation (by the way, I still have it). And Koretska—she was Jewish. Well, I was on good terms with her. She read it: “_І потече іудова кров у синєє море..._” (“And Judean blood will flow into the blue sea...”) “_І не стало іудових синів на землі святій..._” (“And there were no Judean sons left on the holy land...”). By the way, the writer and professor Arsen Ishchuk later read that text and said it was very well written. Said it left an extraordinary impression. I remember when I was writing that essay, it just flowed... I generally wrote good essays... But that one... There was a word in it, like what you said about Stus. I no longer have that same sense of the word, because everything has been burned out: thoughts, emotions, everything. But back then, after I wrote that essay, I walked along the Tasmia river and felt that we are truly an invincible nation, that we will accomplish something. And she read it and said: “You have such thoughts there, such thoughts!” I had no idea what was to come. I just looked her in the eye… From that day on, the torment began.

I won’t tell you everything, because there were things that cannot be told! I spoke on the radio, but I couldn’t talk about all of it. At 15 years old... They were likely injecting neuroleptics, haloperidol... Well, maybe they didnt have haloperidol back then... Or maybe they did inject it, because I didnt know yet. But aminazine—they definitely injected that. At night, they got me into such a state that I had a temperature of 42°C [107.6°F], and tonsillitis. After that—the bedwetters ward on the fourth floor, a horrific place, where there were children... All sorts of children are born, you know! A horrific scene: I saw epileptics. There were children there who masturbated, who wet their pants, it all stank. And they put me in there—the winner of the *Zirka* newspaper checkers tournament, the top student... It crushed me! My brother would bring a package, and Id say: Take it away! They wouldn’t let me see my brother.

Well, to make a long story short, they tortured me there. Then—insulin. When you get insulin, your temperature rises, you can start hallucinating. And in those deliriums, I must have told them everything. What Shevchenko wrote about Jews… I must have told them about Lenin too… When it passes, a person comes to their senses. There was a nurse or an orderly named Tania. She said, “Boy, the things you were saying here! The things you were saying!” I remember she used to bring me books. It was there that I first started reading the literary-critical articles of Ivan Franko. I knew we had Franko, that we were no dumber than others.

It really, as I’ve said, grated on me when I would come to Kyiv and hear Russian spoken. But when I got out of there a few months later, I’ll tell you, I felt it had hardened me. But at the same time, I thought, this is a system! This is already a system! But I was still a child, what could I say? I’m no genius, but I figured it out… It hardened me.

They beat me. And when my brother came—they wouldn’t let me see him. Once I told my brother that my teeth were knocked out. “Brother, get me out of here!” My brother was supposed to be a father figure to me, in a sense. And he says, “I didn’t know what a psych hospital was either!” “Oh, you didn’t know?..”

When I was leaving, I thought, “Well, what was that? An episode in my life?” There sits Koretska, and that Nikitin, such a handsome man. I remember he had a little secretary there. He was probably up to something with her… But thats another story. When I was leaving, I said that it had hardened me.

I returned to 9th grade to continue my studies. I had essentially missed two and a half quarters. And in a quarter and a half, I only got two or three Bs. Then I finish 10th grade with straight As. I write essays. They’re stored there somewhere, those essays. If you need, I can show them to you from first grade. I kept them—it was somehow pleasant.

I grew up on my own. You say I think about everything? My brothers and sister left. It was just me and my mother. The farm work. But I was mostly alone. I used to herd the cow as a little boy—I always had a book with me. A book, a newspaper... Thats what interested me. I finished school. So that Glevakha experience didn’t affect me. In a way, I even thought, well, I’ve seen something. But I saw how people in the village and at school treated me. This was a ten-year school in a neighboring village. I’m walking, and a man on a cart is riding towards me and shouts, “Glevakha!” And what can I say to him? I saw that this was some kind of shame, that I was either sick or what?

But I finished school with all As and went to apply to Kyiv University. We were raised to be honest... I could have approached Professor Arsen Ishchuk then he was from our district, wrote the novel *Verbivchany*. True, it’s not about our village. He knew people. But I thought: I’ll get in myself, I’ll do it myself! I had such strength! Such faith in myself! As a straight-A student, I wrote an essay (it’s also saved) about Symonenko. They gave me a B. So I didnt get in the first time.

Then I go to work at the Skvyra district newspaper, *Leninska Pravda* (“Lenins Truth”). The editor, Klepka, only kept me for a month. He found something out and said, “You’re a slippery one.”

From there, I went to a newspaper in Chudniv. I was more cunning there. I started writing in a certain style... You know, like Oles Honchar: he was for Ukraine, but a socialist one. Something like that: pleasing both sides. Pavlychko wrote even worse. You know. So I wrote there like a national-communist. And they didnt want to let me go. But I said, I want to feel the whirlwind of student life.

But what struck me most then? I didnt even smoke or go out with girls yet. I was pure, as they say... I was at the pre-conscription training at the military commissariat. The first time I applied, I had my registration certificate.

V.O.: What year did you graduate from school?

M.Y.: In 1970.

V.O.: And you didnt get in the first year?

M.Y.: Thats right, I applied to the philology department, by the way. I would have known you for two years then. Natalia Richmedinova (?) was in that years class she lives here now. I meet her here. Shes going through a hard time now, has some illness. A nice woman. Radyshevsky was there too... He always carried the professors briefcases. Now hes a professor too. Thats a whole other story...

So, listen to this. In this military commissariat, Im the best shooter, an athlete, there’s a commendation in my file. I won first place in running in the district, second in the long jump—an athlete. But my uncle Mytro (my aunts husband, hes deceased now) once said, The hardest thing in the Soviet , Mykhailo, is for those who are for Ukraine! I thought: he’s illiterate, finished four grades, was a prisoner of war in Germany, and he says, “It’s the hardest thing.” And I can say the same from my own experience.

So, they give me an award as the best pre-conscript. But before that, Koretska writes a letter there (by the way, she probably wrote to the school as well).

V.O.: Where does she write a letter to?

M.Y.: To the military commissariat. Her letter, Koretskas, went there. And when I was supposed to be issued my military ID (this is the most terrifying thing, look at what a system it was!), Major Bereza gave me the file, apparently so I could tear it out, because he knew it would be a mark for life. This was late 1970 or 1971. And there it was written: “From childhood engaged in philosophy, read a lot of literature. Had childhood neurosis. Underwent a course of treatment. Intellectually preserved...” Well, such praise. And: “Has the right to enter higher educational institutions.” And then below: “Diagnosis: schizophrenia, simple type.” I didnt even know what schizophrenia was. Well, here in Kyiv there’s a lot of information. But in our village, such a word wasn’t used. I read pages of Dovzhenko’s diary—I remember this word from there: “They say war is an art. It’s an art like schizophrenia or the plague.” What is schizophrenia? It’s not even our word. And my hand reached out to tear all this out. But I was so honest, I thought, and then I’d get in trouble for it. But Major Bereza—he told me later: “I gave it to you on purpose. I did everything I could for you.”

Well, I argued with the military commissar there they were asking me something: Why didnt you come the first time, when the commission was here? That was the previous year. But none of my friends from Verbivtsi told me. I would have come then. I thought: Ill hide all this, this psychiatric hospital business. And so they toss me my military ID, like a dog—without a commission, without anything.

V.O.: Where was this?

M.Y.: In Ruzhyn, at the Ruzhyn military commissariat.

My heart sank then. It had category one, article four. And category one—thats schizophrenia. And it further stated: Not subject to re-examination. By the way, I have two of these military IDs, because I “lost” one, thinking that maybe they would give me a new one, you know, with a clean slate...

And so I was already working at the district newspaper, but this weighed heavily on me. I was writing, while the other boys were going into the army. See how they raised us?.. There were boys who, on the contrary, would have wanted anything written about them just to avoid the army. But I felt very uncomfortable, like some kind of deserter.

Applying a second time. I wanted to go into journalism by then. I had a pile of articles (I still have them, by the way). So I go there. They glance at my military ID: Ah... Go on ahead—to the student polyclinic. It was somewhere near the Institute of Philosophy. I went there, near Volodymyrs Hill. And they say, Look, hes sick, and he wants to study? You are not allowed to study. How am I not allowed? I say. Maybe I dont want to serve, I want to study. Oh, look at you! They threw me out. What to do? They wouldn’t even let me take the exams. And I had all As…

V.O.: What year was this?

M.Y.: Seventy-one.

Well, what to do? I come back to the village, and my brother is there. I say, “What should I do?” I always kept all my papers. I still had the form 286 from 1970, when I applied to the philology department. It says 1970 on it. Who would give you a new certificate? I say to him: Go ahead, put an ink blot there so the year 1970 isnt visible, so its not clear what year it is. Youre the one who got me into this anti-Sovietism! So put a blot on it! And he made such a huge blot. I said to him, You cant even make a proper ink blot! Well, it’s all over. We send the documents to the admissions committee. Im thinking, they wont even call... And in the village, people will point fingers: Look, there goes the schizophrenic, the sick one, the madman. I was the smartest—now Im the dumbest. But then a summons arrives. And I take the exams. I pass, did well on everything. Everything was normal: one or two Bs, the rest were As.

And so Im studying. How did it happen that I, a freshman, ended up with you, fifth-year students, in room sixty? There was a girl named Leliukivska (?)—you must know her, she’s from the neighboring village of Berezianka and studied at the same high school as I did. When I came to the ninth grade, she was in the tenth. And well, the school was buzzing about me! I spoke at school assemblies, talked about Hrinichenko there. What a scene that was! I even recited Vasyl Symonenko there... She told them about my nuthouse story, about Glevakha. In other words, she cast such a stain on me! When I moved into the room, there was a guy named Tupyi, Volodymyr. Hes Muzyka now. I think he works at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs—he must have been an agent at the faculty. He started tormenting me. There was another one: “We already know about you. No one will talk to you anywhere.” This was right after I moved into the room in student dormitory No. 5... Well, there was another guy named Mykola... I realized she had told them. I saw it wasnt even interesting to talk to them. I decided it would be better to move in with the fifth-year students, with smart people. When I came to that room, No. 60, there...

V.O.: You swapped places with someone, I think?

M.Y.: Yes, with Mykola Bohuslavskyi. It was like paradise for me then. My God! I learned so much in that room!

V.O.: Who was there?

M.Y.: Yuriy Skachko (I dont know his fate), Yosyp Fedas, Ivan Bondarenko, and Vasyl Ovsiyenko, that is, you.

I remember you well. Your bed was by the window, to the right as you enter. It was a corner room. You had your books here. You sometimes slept, like Rakhmetov, without a mattress... Well, I really liked it there! But, you remember, that Tupyi was already trying to get in there too. He changed his last name to Muzyka. Actually, he heard me on the radio, met me and said, Oh, Im so glad to see you! In fact, it was because of him that I moved in with you, because others there were also bothering me. They already knew my life story, as I understood it. Because it was Leliukivska... It must have been Leliukivska, because there was no one else from my area who could have told them about my psychiatric hospital business. Because when I was applying, I kept it a secret. I didnt tell anyone in my year. And I didnt tell you when I was living with you. I only told Ivan Yakovych Bondarenko: I have this thing on my soul, Im always thinking about it. And he said: It will pass, youll laugh about it one day. But as you see, it didnt really pass with time...

There I got acquainted with Ivan Dziubas work *Internationalism or Russification?* I remember how it happened. I came in once, and there... I thought Ivan Yakovych was eating salo: there was a table lamp, and he had a newspaper spread out. He was an interesting man. I remember he was cheerful, loved a drink, and had a great sense of humor.

I remember when I came to you, brought my books, set them up. And then they introduced me: “This is Ovsiyenko.” Everyone there loved Ovsiyenko. And I say: “Oh! Where from? A fellow countryman, countrymen!” “Ah, ‘a little countryman with tin buttons’.” I remember that. You were already graduating. Of course, you had rosy plans. You wanted to apply for postgraduate studies. And I was envious: I’ll finish... I’ll learn from them. Well, youth! You understand what youth is, dont you? Its hopes for a better life, for the future. I thought that life would be good and no one would spoil it...

So I walked in and thought Ivan Yakovych was eating salo, but he was reading Dziuba.

V.O.: What form was it in?

M.Y.: It was printed on cards.

V.O.: On photo paper?

M.Y.: On photo paper. There was a whole lot of it, as you say. I ask, What is that? Dziuba. Are you serious? How? Let me have it! Ive heard about him. I was always looking for guys like Ovsiyenko. I was looking for them back in the Kryvoshyiivska school, but I didnt find any. But here there were guys from all over Ukraine... I read it twice and even took notes on parts of it. The KGB never knew that I had taken notes.

V.O.: And I remember Ivan Yakovych told me later that he was the one who gave it to you. He didnt ask for my permission.

M.Y.: He did. That was the kind of information available back then! It’s even funny: Lenin is mentioned as a messiah four hundred times in it. It was considered anti-Soviet literature, but the author had sent it to the Central Committee! But I say: if they, the fools, had acted according to Dziuba’s work, maybe it would have been a lifeline, so to speak, to preserve the . But they acted differently. They broke Dziuba. But it was a normal work, by the way. It was pro-communist, a hymn to Marxism and national-communism. But they considered it to be overloaded with information.

In my third year, where I was studying modern Greek—I thought of translating ancient Greek literature—the darkest period of my life began in 1974. That was Glevakha (I have it written down somewhere: 1968–1975—that was the terrible seven years). Well, maybe God gave me the strength to endure it. I don’t know how much longer God will let me live, but these are the things, as they say…

I remember, it was in the kitchen I was frying potatoes at the time. This was in my second year. Viktor Baranov says to me… (Later he worked in the Central Committee of the Komsomol—well, of course, they don’t just pick anyone for the Central Committee. Now he’s the author of the song “To the Ukrainians”). Maybe he wanted to test my reaction, and he says: “Do you know that Ovsiyenko has been arrested?” I was frying potatoes at that moment: “You don’t say?” And I had written a letter to Ovsiyenko back then. While still in my second year, to Tashan in the Pereiaslav region, where you were teaching. But I never got a reply. Maybe they intercepted it. Maybe that letter was the reason I was summoned then... I dont know who or how, because before that, Ivan Yakovych Bondarenko had come to visit me, and he said: Under no circumstances say that you read it. Did he really think I was such a fool that I would say it? But those tails were following him on Khreshchatyk. Theyd say: Oh, Ivan Yakovych, good day! Well, is it a great feat to follow someone? What’s so clever about that?

One day this investigator, Pokhyl, calls me. He calls and speaks Russian. I didn’t know how this would be used against me in the investigation. I was planning to quietly immerse myself in my studies. I was studying modern Greek. I wanted to somehow get that article [on his medical record] removed. Because I knew it would hinder me later. I didnt tell anyone about these issues of mine.

On the phone: “_Eto vas leytenant Pokhyl bespokoit. Vy mozhete zavtra priyti?_” (This is Lieutenant Pokhyl calling. Can you come in tomorrow?). It already grates on me. I respond in Ukrainian… It was somewhere around the end of May, maybe May 22nd. I dont remember. They probably have protocols. They called me to the security desk (this was in dormitory No. 5). I went. “_Vas takoy-to bespokoit... Vy zavtra mozhete? Ya budu tam na Vladimirskoy, 33_.” (“So-and-so is calling… Can you come tomorrow? I’ll be there at 33 Volodymyrska Street.”). I understand now that they, the KGB, just needed to earn their keep, to justify their existence. It infuriated me that he spoke Russian, while I responded to him in Ukrainian.

And my brother happened to be visiting me at that time. I say, Theyre already summoning me to the KGB. My brother stood stiff as a board. “What should I say? Should I say I read this Dziuba, or not? What should I do?” I wanted to earn some loyalty. I have this article on my record. I got into the university illegally. By their laws, no one would have accepted me into that university. They must have dug it up later, how it happened. My brother says nothing.

I met with this Pokhyl… A fat man, I remember. He leads me down these corridors. We sat somewhere far off. I remember it was a kind of semi-basement. And the windows were barred. I remember, as you enter—there’s Dzerzhinsky. This is 33 Volodymyrska. I saw his desk was covered in this samizdat. It was printed somewhere, or did they have those Xerox machines back then? Because it was printed so beautifully. I’m thinking: where was this printed so beautifully?

V.O.: It was an Era copy machine. A rarity back then.

M.Y.: But they had one, right? Very nicely done. I would have liked one myself... I was always looking for that path. My thoughts: how to make Ukraine independent, and so on. I could have learned so much from this samizdat... Did you read this? I say: No. I wanted to say I wanted to read it, but... Did he, Vasyl Ovsiyenko, give you anything to read? No, he didnt. Come on, stop it! Because you understand, for a sincere confession we have leniency... Tell me honestly, did he give you anything to read? No, he didnt. Tell me honestly, did he give you anything to read or not? Im asking for the last time! Well, I say, if only my brother had told me to insist: I didnt read it – and thats all. But that was my fate! I say, He didnt give it to me. Ivan Yakovych, I think, what about Ivan Yakovych, a disabled man... I say, Ivan Yakovych gave it. Vasyl didnt give it to me.

And then he started asking about you. I said that our relationship was good. I said it was a surprise for me that you were arrested. He’s stalling. I say I had little to do with him because he was an upperclassman, he was older. Just that our relationship was normal. And I ask: “What did he do that was so bad?” He doesnt say anything. “Well, he’s going to be tried anyway. You can’t do anything…” I understood that they had called me in just to sound me out, to find out who I was. “He’s going to be tried.” “But what did he do?” He doesn’t say. “I heard he said something in class… What is there to try him for?” I say, “he was a good person, our relationship was normal…” “Well, what did he talk about?” I tell him: “Well, there were conversations. He said that in the Baltics, they are also oppressed.” I essentially gave myself away with that. I should have played dumb, pretended I knew nothing. By the way, Pokhyl said: “Oh, you speak Ukrainian so well.” And his own speech was so poor… He’s writing the protocol, twisting my words. “Sign it…”

Well, when you enter the KGB building, there’s this aura… How many people they destroyed there! And just before, some boss of his, apparently, came in and said: “Tell him, or we’ll send him to a factory.” “For what?” And then: “Sign.” The protocol. And I ask again: “But what did he do?” He doesnt say anything.

I felt so bad after that! I even talked to Mykola Bohuslavskyi then. We were friends... We used to go running here... From Lomonosova Street to the lake behind the exhibition to swim. I was worried. I didnt want to go running. I didnt expect you would end up there... They had a strong surveillance system.

I was also at the trial.

V.O.: How was it? It’s clear our weak point was that we didn’t know how to lie.

M.Y.: Yes, thats right.

V.O.: And they had mastered lying. They did it perfectly.

M.Y.: At every turn. For them, it was a piece of cake.

V.O.: Was there only one summons? Or were there more?

M.Y.: One time. They summoned me once. Well, that time I was 15… And here was societal schizophrenia: these mass media, literature, newspapers. You read them and you’d think it was a fairytale society. I have complaints against Honchar, and against Stelmakh. These writers should be tried for distorting reality, for lying… By the way, you once saw me keeping a diary. Roman Ivanychuk has a novel, *Malvy*. There are two roads in it: one is open—that’s the one Stus seemingly took, and the other is like Pavlychkos, I guess. He bent: “I was like that, I knew how vile it is to serve the great (or the boss). But I rose up, and I curse that time when I bent like that vile scum.” So there is this second path, to do ones own thing. I chose that second path. I have it written down somewhere... They were watching me... I know who was watching in the second and third years...

And so, the trial. I was the youngest of the witnesses. Good thing I knew the least. I didn’t even know what Ovsiyenko was on trial for. They called me right before the recess. What was said there? I remember Ovsiyenko said (that is, you said) that it wasnt anti-Soviet, that it was poems by Tychyna or Sosiura, published in the 20s. How could that be anti-Soviet?.. And then they called me. I know that I’m already punished, that Im basically here illegally. No one knows my background, that according to my documents I’m technically a schizophrenic. I’m still studying, with this Damoclean sword hanging over me. And I’m young, I didnt even smoke yet, I was young, energetic.

V.O.: You were summoned to the trial?

M.Y.: Summoned. I remember you were sitting there in a plaid shirt.

V.O.: The trial was in late November—early December 1973. When was your ordeal?

M.Y.: It was after the trial. Your trial must have already reached a verdict. They have what’s called a chastnoye opredeleniye [a special ruling].

V.O.: That’s an `okrema ukhvala` for them [a separate judicial ruling].

M.Y.: Or `okrema`, yes. We were sitting in the courtroom next to Vira Lisova. I liked her very much. How did it all happen? Before the trial, they summoned me to some department in the rectors office: You will be speaking at the trial...

V.O.: Wasnt it Liushenko? The curator of all university informants. He had an office in the rectorate. He came to see me, already arrested. He said, How did I not know you? And I, like a fool, said, But I knew you.

M.Y.: I dont know. They had their eye on me for a long time. Either during this interrogation or during the investigation. I’m thinking, what am I going to say there? What do I know? I remember that when the trial was on, you were in a plaid shirt… It was sometime in December. I already said that I was sitting with Lisova and Proniuks wife. I remember Lisovyi: such a handsome man, black hair. My soul was trembling that, those bastards, they are taking our people. I remember Proniuk too. He was a bit reddish-haired, I remember, slightly balding... Well, and just then they brought you in. You are on the right, the prosecutor is kind of handsome, in a prosecutors uniform. And I think: “My God! They’re even speaking Ukrainian! They are our own!”

V.O.: Prosecutor Makarenko.

M.Y.: Our own!, I thought to myself. Did he want to harm you? If there had been an independent Ukraine... Our own people! Well, scum, scoundrels!

I came forward and said, It was a surprise for me that Vasyl was arrested. He says, Im not asking you that! Did he give you anything to read? Well, he did. He spoke about the national rights in the Baltics. He did. So what if he did! Thats all I can say. Sit down! I sat down. And then, I remember, I walked past you and gave you a wink. Well, what could I do? Im telling you, I was inexperienced. I’m saying, my brother was there in the evening. He should have said: Just say no. I didn’t think that just because I read Dziuba, you would get such a sentence…

What next? That meeting... I remember that on March 9, 1974, I went to Shevchenkos homeland. I visited his grave later. Our year group went to his homeland, to Moryntsi, to Shevchenkove. I return, and they summon me to the deans office. They had been planning it for a long time. And it was like, What have you done? Youre such an enemy there.

They gather. Who spoke there? A girl from Bila Tserkva spoke…

V.O.: Natalka?

M.Y.: Yes.

V.O.: How was this meeting prepared? Who was the initiator?

M.Y.: The pro-rector for economic (?) affairs, Pavlo Horshkov, or whatever his name was, was there. Pavel, and then… Well, I have notes somewhere. There were many teachers. It was the largest auditorium in the yellow building, on the third floor. I just dont know if that auditorium is still there. It could hold the most people.

V.O.: Was it a meeting of the faculty or the year group?

M.Y.: The year group. The third year was large. You see, they didnt let me finish. Thank God, at least they let you finish.

V.O.: And what did people say at this meeting?

M.Y.: Ill tell you now. It was March 18, 1974. I remember it was already warm, a kind of early spring that year. Im wondering what theyll do with me. I remember they were already sitting there when I arrived...

V.O.: Who were they?

M.Y.: The students. They were already sitting. And I was a bit late, I was preparing my speech. This Semenchuk, the professor who wrote about Hryhir Tiutiunnyk, grabs me by the sleeve like this: Why are you late? Where have you been? And he pulled me so viciously. And they started tearing into me at this meeting! (I have notes). First, the students spoke. What didnt they say about me! And there was some Liuda Klets (?), a heavy-set girl. I dont know if shes alive. She barely passed with Cs. I dont know how she got in there. Shes from Volyn, by the way. She said: These Banderites, these nationalists, and you too... – thats how she talked. Then this Heorhiy Khimich—hes now the editor-in-chief of the Novohrad-Volynskyi district or city-district newspaper. Just recently, I opened the newspaper *Literaturna Ukraina*—and I see he was admitted to the Writers . He used to write some childrens verses. During the stagnation era, some record of his came out in Moscow, some childrens songs. This one spoke out so harshly! And I lived with him in the same room in our second year. We had a debate then. He was all for this Lenin, with such hatred, saying they are nationalists... And I told him: At least youll make a career at the expense of Ukrainians. And then he spoke very badly. He was so spiteful. And now, I don’t know who got him into that . He later told me they had told him that if he didnt speak out, he wouldnt be admitted to the party. He had already served in the army. He had the rank of lieutenant. An unpleasant person. I don’t know what hes like now. Then Vasyl Stepanenko, with whom I studied modern Greek, also spoke.

V.O.: Vasyl too?

M.Y.: Yes. Stepped over dead bodies. This Natalka Bilotserkivets spoke. Not about me, but about some people who had approached her with some nationalist text, and how she rebuffed them, condemned it all, such a genius. Now I found out she spent three years in America. It would have been better if I had been in America, maybe I could have been more useful. How did she manage to get there? She was showing off back then too.

Well, who else? Yevhen Konopatskyi—he was writing the protocol. Thats not the point. They say now that if they hadnt spoken out against me, something would have happened to them. What would have happened? If all fifty of them had simply not shown up or not voted... How many were there: 50 or 70? I counted them, there were 100 (50 just in our Ukrainian department. In total there were 107 students. And there were teachers too. The place was packed, at least two hundred people. Maybe more. And the snitches came too). What would have happened to them if they hadnt voted or hadnt come? Would the entire year group have been expelled from the university? Thats all nonsense. They were scoundrels, I’ll say it again. Now time has passed—they could at least have apologized. They graduated in 1976... And I finished by correspondence later, in 1979. What kind of education was that... There was a twentieth reunion of their graduation, 1976-1996. They could have at least invited me or said sorry or something. Let them not make excuses, I bear them no ill will, but they were fully formed adults, 21, 22 years old.

Who else spoke there?... Pavlo Benyk. Now a school principal. I want to write an article titled “The School Principal.” There was Petro Diachenko. Remember that name. They say some Diachenko is Yeltsin’s son-in-law. I dont know if they are talking about him (he studied with me). I don’t think he spoke out then.

V.O.: And what did the professors say?

M.Y.: Wait. I’ll tell you about Diachenko. He is apparently now the deputy head of the SBU for the Kyiv region. I never had any conflicts with him. He was a teacher.

Who else spoke there?... There was one girl—Tania Shevchuk. From the Russian department. She got into a lot of trouble for it later. There was also some Kholodina, but this girl was the main one.

And from the teachers, there was one (she is probably still alive) Margarita Karpenko. She, for one, told me beforehand… But look, if we’re getting into it, I’ll tell you now. I’ve thought a lot about this. It’s not about me. You need to know how their kitchen works and their logic. If I am already sick, why expel a sick person? Did I attack anyone, strangle them? What scoundrels!.. I say to this Margarita Karpenko: Why are you doing this to me? What did I do? So I read Dziuba. So I had some conversations... There were denunciations. They say Brezhnev’s times were easier? It’s a lie! How were they easier? To this, she says to me: If you had reported on Vasyl... You see, the first time in Glevakha they gave me paper to write denunciations, and I didnt. In Bila Tserkva, they gave it—I didn’t do it. And now the same thing: “If you had reported on Vasyl, you would have been on top.” In other words, the Pavlik Morozov principle again! I think, how can I write a report on Vasyl when I liked and admired this man? If he were a scoundrel—that would be a different matter, one could burn him. You could write a report on a snitch if the snitch is trying to provoke you. I say: “I don’t know anything. My mother has worked so much, she’s old.” “Mothers endure even worse things than that!” That was our conversation. And I said my childhood was so hard, without a father, and so on. And this filth, as I read in the newspaper *Osvita* (Education), has now become an academician of pedagogical sciences, you understand?

V.O.: This Margarita Karpenko?

M.Y.: Yes, about a year ago, in independent Ukraine. That’s how it is.

Now, Oles Bilodid. That scoundrel also spoke, saying: This is a rotten sheep! What right does he have to be here with Ovsiyenko deciding the national question? It was solved in our country long ago. Why are we sitting here? Discussing some Yakubivsky, or whatever his name is? People are smelting steel, miners are extracting coal, and were here talking about some Yakubivsky and Ovsiyenko who wanted to solve the national question. He will never be in our university, this rotten sheep... And the rest are sitting there, watching. Theyre curious—they came to watch the show. And not one of the professors spoke up in my defense...

Nina Yosypivna Zhuk speaks. She says that over the years of Soviet power, so many of Kotsiubynsky’s works have been published. Well, they were published, of course. But at the same time, people were imprisoned, imprisoned for a thought, there were repressions! Yes, those books were published. But they used that literature for communist or Bolshevik indoctrination and said that Kotsiubynsky, whom she studied, wrote under the influence of Gorky. But thats a lie! The proletarian writer Gorky hosts the Ukrainian writer on Capri. And Gorky has a three-story dacha there! The poor proletarian writer! Who else spoke?

V.O.: And Valentyna Mykolaivna Povazhna.

M.Y.: Povazhna? I dont really remember. But since they told you that, it must have happened.

V.O.: Olha Heiko remembered she said: To live in the same room and not know what’s in your neighbor’s briefcase—that, excuse me, is not very Komsomol-like.

M.Y.: Yes, I remember you didnt even have a briefcase. You see, how much haloperidol they pumped into me, and I still have a memory... You had a suitcase.

V.O.: No, a briefcase. And the suitcase was under the bed.

M.Y.: There was a suitcase, and what was in the suitcase...

V.O.: No, the samizdat was only in the briefcase. I only carried it with me so that no one could search the room without me being there.

M.Y.: Thats one thing, I didnt snoop, why would I? And in general, Ill tell you, thats how it turned out. And you really were a unique philologist.

V.O.: Well, alright, how did this meeting end?

M.Y.: It ended with an almost unanimous vote... Seven abstained, three were against, as I have it recorded. And the rest were for expelling me from the Komsomol. And once youre not a Komsomol member, that means, accordingly, an order from the rector...

V.O.: Did that order come soon?

M.Y.: The meeting was on March 18th, and the order came about ten days later. I went to see that rector, Bilyi. I said, For what?...

I remember how I spoke. They saw that I could agitate. They had their eye on me. If they had had a bit of sense—I’m being honest with you—if they had stroked me nicely, I might have written poems for the Soviet government no worse, perhaps even better. But when they threw me in the nuthouse in Zhytomyr, I saw them for what they were… And they are so stupid... When I spoke, they saw that I could agitate. But at the end, I recited a poem. I had to disguise myself. I recited about Symonenko: _“Куди б мене дороги не манили і хто б мене на манівці не вів...”_ (“No matter where the roads beckoned me, and whoever tried to lead me astray...”). But who wrote it? I’ll bow to one person, you know who: “_і хто б мене на манівці не вів, у мене вистачить і розуму, і сили іти по тій, що Ленін заповів_” (“...and whoever tried to lead me astray, I have enough sense and strength to walk the path that Lenin willed”). Thats Symonenko! So, whoever is smart understands! Here I am quoting Symonenko (Laughs), but thats how it is…

How I was expelled—you could make a whole film about it. I looked around. And then I thought (you see, Im forty-six now, but I was twenty-one then): A forest of hands. My God, Mykhailo! And they don’t even know: a schizophrenic is speaking before them! You understand, they couldnt compete with a schizophrenic, with a mentally ill person...

Zarytskyi also spoke out very strongly against me before. He taught Russian grammar, was deputy party secretary. I think he’s still alive. So he says: I was recently at a meeting with Shcherbytsky. Shcherbytsky is such a good person. He says things like that. And Im thinking, youre a snitch. When I was a student, I understood that every professor, maybe every other one or every third, was an agent there.

And then this Serhiyenko spoke. Hes deceased now. He was the secretary of the universitys Komsomol organization. Later he worked at the philosophy faculty. They say he died recently, this year or last. He also spoke against me there. And that Horshkov, I remember what he said. He taught the history of the CPSU. “_Dopustim, chtoby ukrainskiy yazyk byl ot Karpat do Sakhalina. Nu i chto? Chto pri etom izmenitsya?_” (“Let’s suppose the Ukrainian language stretched from the Carpathians to Sakhalin. So what? What would change?”). He was talking such nonsense. (The next day, this Horshkov ran into me by chance and said: “_S vami nado pogovorit_.” [“I need to talk to you.”] This was the pro-rector. He didnt know my story yet they started digging later.)

In my speech, I mentioned my father, said that my mother worked on the collective farm for 40 years, and my father fought in the war. If only I had the sense I have now: I have my father’s medal “For Courage”—my father was on the front line. And my uncle was a Bolshevik. My uncle was a national-communist he was killed as soon as the war started. He even headed the district party committee or the district executive committee in Ostroh—Onufriichuk, Hryhoriy Danylovych. So you see, I didnt use any of these facts. And when they were expelling me, Mykola Moroz was in the deans office (and his wife, Valia). Mykola Moroz is another scoundrel. He later worked somewhere in the district committee. And his Valia said: “If it were wartime, he would have been a policeman. He would have been on the side of the Germans.” Do you hear that? And I say: “But my father fought...” These Morozes, by the way, are friends of Radyshevsky. And she apparently works in the Verkhovna Rada now.

This Serhiyenko says: Why, Mykhailo... Ill set you up. He wanted to make me one of his. In other words (I felt it already), to make me an informant. Youll stay here, in Kyiv. There are construction workers dormitories on Lomonosova Street, youll work a little. But Im studying modern Greek. No. Well, he says, well find you some Greeks.

And I thought, Ill go into the army and get rid of this article on my record. I specifically went to Zhytomyr. I thought, it’s closer there. Ill resolve this issue of removing the article because its going to hinder me my whole life. I’ll even go into the army.

They summoned me to the KGB a second time. Only not to the basement, but here, to the pass bureau, on the left side of Volodymyrska Street. There was a Vitaliy Fedorovych there. He was Jewish, apparently. But he spoke Ukrainian so well! I found out later that his last name was Ukrainskyi. We had a nice chat, and he said: You made such an impression on me! So they lost a great agitator for the Soviet regime in me. I praised the Soviet regime back then like Pavlychko. I knew what to say, to sound like Stelmakh or someone... He says, “You know, our prison here is empty now—there’s no one.” Im thinking, So what, you want to put me in there? (Laughs). Hes just talking, the doors are closed. (And when I went for my first interrogation, I had to get a pass. I said Ovsiyenko had been arrested. “_Ah, chto, svikhnulsya?_” [“Ah, what, did he go nuts?”]—so to them, anyone against the Soviet government had already “gone nuts.”)

And this one: Why are you going to Zhytomyr? I say that my mother is closer there. I didn’t mention the article. You understand, psychologically, its a disgrace. Those bastards invented this psychiatric hospital—its the worst thing, worse than a concentration camp—everyone says so now—its a ratio of 1 to 15.

I go to Zhytomyr, get a job at the regional Komsomol newspaper. I said there that I was a Komsomol member. I didnt think they would do anything bad to me. I said I had transferred to correspondence studies. The editor there was Dmytro Panchuk—by the way, hes the editor of the Zhytomyr regional newspaper now, the scoundrel, he knows me. Let me tell you: if we were to make a list of those people now… God be their judge, but if such a list were made...

V.O.: Which newspaper did you get a job at in Zhytomyr?

M.Y.: *Komsomolska Zirka* (Komsomol Star). I could write, you know. And that Vitaliy Fedorovych—he gave me an address: Youll go to this parish there. We have a parish in Zhytomyr.

V.O.: The KGB?

M.Y.: Yes. I thought, first, I need to show my loyalty. What mattered most to me was to get that article removed and to serve in the army, because in essence, I don’t even know how it happened the first time. Was it that scoundrel who did it? For what reasons did she do it? My brother brought books about Ukraine to Glevakha, and they tore them up there. And here they told me: “_Ty khotel KGB nakolot?_” (“You wanted to trick the KGB?”).

I went to Zhytomyr to get that article, that stain, removed. I wanted to serve in the army. I thought, just as they ‘washed away their guilt with blood’ in penal battalions during the war, I too will serve my time! I want to tell you the details. I enter the Zhytomyr KGB building. I remember it was somewhere before the park. When I was going there, I had this feeling... It instills fear. So many people were shot there!

V.O.: On Parizkoyi Komuny Street.

M.Y.: I was there once, and then they would meet me on the street. But they left phone numbers, thats the most interesting part. So, whats up with you? I remember hes smoking Novost cigarettes. This was sometime in April 1974. A young guy, should have been chasing girls. But I had just started smoking because of those events. You smoke? I was smoking Prima or something with a filter. And he offers me a Novost (for some reason it caught my eye): Maybe we should smoke a Cossack pipe?—trying to provoke me like that, you understand? Is this a Cossack pipe? Yes, yes. Well, says this Borys Vasyliovych, I was in Western Ukraine after the war. Oh, the things I saw there! Can you imagine how many he shot there? This Mykola Yosypovych—he will be your uncle, he says. And that one is standing there, with a hooked nose, an unpleasant face. Graduated from Leningrad Law University. Hell be your uncle. Im thinking, what uncle? Do you have any money? I say, What money! I just arrived... Well, heres 20 rubles. Write: received 20 rubles. Sign here. Im thinking, My God, what is this? I didnt want to take this money. But, I thought, maybe theyre just being kind, maybe I misunderstood them? Maybe because Im an orphan or something? I didnt know what they wanted. So kind! But at the same time, something in my soul twitched.

And then (I was already working at the newspaper) this Mykola Yosypovych meets me. I mention that some tenth-grader was beaten up, and he said, The police beat people like the Gestapo. Why didnt you tell us? Whats his last name? Who is he? Well, I say, what do I know about you? And my aphorisms were published in the magazine *Ukraina* in April 1974. Four of my aphorisms got through. The magazine had a portrait of Lenin on the cover. He reads: “Balanced: he grew an apple tree with both sour and sweet apples.” “What does this mean?” he asks. “That you’re for both us and them? You’re apolitical?”

I got a job at this newspaper in mid-April, and May 5th was Press Day. The newspapers editor, Kuzmych, was a good man, God bless him, he liked me. I didn’t work there for long. And I lived in a room on Gagarin Street (incidentally, where that executioner, the psychiatrist Kuznetsov, lives now). I shared a room there with Oleksa Kavun. He still works at the same *Zhytomyrshchyna* newspaper. Still the same commie! I used to tell him that one day we would raise the garrison for Ukraine. And he’d say, You need to be sent to Huiva. That is, to the nuthouse.

It was Press Day. Panchuk was heading the *Komsomolska Zirka* then. We gathered on the bank of the Teteriv River, in the park. It was nice: snacks, shashlik. You know, in those days, the press was everything. There was a girl there I played tennis or badminton with her. I had a bit to drink and left. Im walking, and theres a payphone. I call Borys Vasyliovych: Borys Vasyliovych, I understand you. You want me to work for you. What do you call it: a nark, an informant, or a snitch? I will not work for you. Please forgive me. Goodbye!—bang, and I hung up the phone.

The next day, I get fired from the regional newspaper. Where to find a job? The medical record? Go on disability? Who would want me... For everyone to laugh at? You see what a system!

I go to work as a loader at the flax mill. The bales there are so heavy. I’m on the night shift. And again, they’re watching me, and again they start, about who among the workers is saying what—to hell with you! They didn’t pay me for a month and a half. I quit, thinking, “To hell with them.” I thought Id leave here for Kyiv or even Tashkent. Because Tetiana Chernyshova says, “Run from here, or they’ll…” And then the police grab me—wham. Their van takes me away. I’m thinking, “For what?” This was June 13, 1974. They put me in a cell, like an elevator. There’s a man sitting there, a plant, obviously. I start banging on the door, and he says, “Don’t bang. Another guy was banging here, and they gave it to him…” When they lead me out, I ask the captain: “Why have you detained me? What laws have I broken?” “Well, you were expelled from the university…” “And what does that have to do with you? What are you going to do to me?”

And Pavlychko knew me. I idolized Pavlychko back then. I thought Pavlychko would come to my defense… When I was on my way to Zhytomyr, I visited Pavlychko, told him I was going to Zhytomyr. “Indeed, you need to serve in the army, and then you’ll return.” And that Pavlychko... Later they said he was some kind of KGB agent. That Beria himself recruited him. Well, thats how it was: whoever refused to serve them was destroyed...

Well, I say: If you do anything to me, tomorrow the Voice of America will know about you. Well, he says, give you a Voice of America right now! And the doors open, and just like in the movies, in come these heroes of our time in white coats. They twisted my arms. I’ve never told this anywhere—not in the KGB, not in Glevakha, that I had a disability status. (You know this story, and Ive told it on the radio now). They brought me to the reception ward. He asks, “What, are you hearing voices?” I say, “I am.” “What kind?” “The Voice of America.”

Back then, I was living in a room with this Oleksa Kavun. They say hes related to that party official, Kavun. He still works there. When they took me, some of my notes and food were left behind: my mother had just slaughtered a pig. I don’t know what happened to it all—they cleaned everything out.