KAVACIV1

An Interview with Father Josaphat KAVATSIV

(Last proofread on 02.21.2008)

V.V. Ovsiyenko: February 3, 2000, in Stryi, Father Josaphat Kavatsiv, rector of the Church of the Annunciation of the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church, is speaking. Recorded by Vasyl Ovsiyenko.

Father J. Kavatsiv: Beginning in 1946, very sad times befell the Greek-Catholic Church. Everyone knows this, history knows this, but, to my deepest regret, nobody—or rather, not nobody, but very few people—now wants to admit that the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church took a great step in building an independent Ukrainian state. It seems to me that without such a Church, we would not have Ukraine today. Those who taught me, those who were in authority then—our bishops, our professors—were ideologically Ukrainian; they held God, the Church, and Ukraine in high esteem, despite the fact that in 1946, almost all Greek-Catholic churches were liquidated, with the exception of those where village councils were located (only there were the churches preserved), while all other churches were closed and turned into various warehouses. It was horrific vandalism—what was done to the Greek-Catholic Church.

Many Catholics in the villages immediately went underground, deep underground, to the extent that they didn’t even go to church; they were subjected to ridicule by their fellow villagers or townsmen. It was easier in the city because in the city people know each other less, but in the villages, the situation of those poor Greek-Catholics who were faithful to the Catholic Church was unbearable. They did not go to church, were not buried according to the rite, were not baptized, did not marry. In Western Ukraine in 1946, intense arrests of our bishops began; they started deporting our priests. Only a few bishops and priests remained. And people died without confession, without Holy Communion, and lived without a church wedding. They married with two witnesses present—we were taught that in such a case, one must act this way to preserve one’s faith but not to submit to the Russian Orthodox Church. It carried out a terrible terror in Ukraine. We see now what they have. They have almost 10,000 parishes throughout our entire Ukraine—while we have 1,200. And the Poles have as many in Greater Ukraine—and we are again left with nothing.

The Ukrainian Catholic Church, which has for a full 400 years, since the Union of Brest, been faithful to the Apostolic See, remained faithful to it to the end. I do not want to sin against the Pope; I respect the Pope very much and suffered for the Pope. It would have taken just one wave of the hand—to write against Slipyj, against Lubachivsky—and you would be released from prison. But I never did that, because I am a patriot of the Church and the Ukrainian people. But for the Vatican functionaries (forgive me for saying so), hundreds of whom have now been exposed for collaborating with the KGB, we became a stumbling block. They would have been ready to liquidate us in that very second. Moscow Patriarch Alexy II says he will not even serve with the Pope until he liquidates the Uniate Church. That is how great we are in their eyes, such is the power we have, and such is the fear they have of us.

The priests were arrested before Stalin’s death, and after Stalin’s death, the priests and bishops began to return. Litoshevsky (?) returned, Chernetsky returned—not many bishops came back from imprisonment and exile. The situation was very difficult. But they were so understanding that they ordained all who wished and were somewhat prepared for the priesthood. I was not so fortunate. I studied theology for 12 years. Dr. Maksymets taught me philosophy (Mr. Melen knows him; he lived in Morshyn), as did Father Dr. Tymchuk, a professor of theology, who died held in great esteem. Everyone respected him; he taught many priests. Bishops Fedoryk, Klyuchyk—these are notable figures who wanted to do something good for the Catholic Church. In that very difficult time, Bishop Slyzyuk (?), who ordained me in Ivano-Frankivsk, said: “Father, do you realize what you are doing?”

We were released, but we were on the verge of being arrested again, because they were deporting people, evicting them, striking them from the registry in Lviv; they created terrible havoc with the priests and bishops. It wasn’t until May 24, 1954, that Protohegumen Hryadyuk of the Order of Saint Basil the Great arrived, and I took my monastic vows. I had been a Basilian since 1954, but just two years ago, those who collaborated with the KGB managed to have me removed from the Basilian order because I was not to their liking! Who would have thought—to be in an order for 54 years! And in the end, they did it, cast me off like a glove. I don't make anything of it, because I swore an oath of allegiance to Christ, not to Patrylo, nor Mendron, nor anyone else—I swore allegiance to Christ, and I have kept it to this day. I preserve what I was taught and what I have practiced for 54 years. And on May 24, 1962, Bishop Slyzyuk laid his hands on me and made me a priest. And from the very first day, having been ordained on a Friday, that same Saturday I set out with a bag in my hand, like all the other priests, to help people, because there were very few priests. And that’s Lviv: one wants a baptism, another a funeral, another a confession, another a wedding. And all of this had to be done.

By my estimate, in my priestly ministry—it will be forty years next year—I have worked in 87 villages and cities. I'm not just talking about Lviv as a single house. I would celebrate Mass in a home—if it was in a home, fine, and if I was called somewhere else, I went. I traveled to Kyiv and to Vilnius. Roman Khustynych and I launched such a major effort; we threw ourselves into such a whirlwind… I had him ordained by His Grace Khira in Karaganda. There was no one else, you know, on hand… His Grace Fedir was very kind, but he couldn't keep a secret. He went to the KGB and said: “Just so you know, there is one man to be a priest—I will ordain him.” Well, it’s nothing for you, you’re eighty years old, no one will do anything to you. But what about that young lad who is twenty-two years old—how is he to proceed? So I arranged it with His Grace Khira (he was a bishop from Zakarpattia, ordained after Romzha and an exceptionally good, loving person), so he came and did it for me, and it was easier for the two of us because where I couldn’t go, he went. I moved to Lviv, but every two or three months they would strike me from the residence registry. I was stricken from the registry in Lviv eight times. Someone comes—and writes you out, and writes you out, and writes you out, and each new propiska costs a thousand, a thousand, a thousand.

Then all that business with the propiska ended. We thought that since we had bought ourselves two rooms and a kitchen, no one could take it from us, because it was our property. But at the trial, they slapped us with Article 209, which includes full confiscation and exile. And that was it—what good is it that you own it? It wasn’t mine, and no one will ever give it back to me; it was lost once and for all.

I worked a great deal. Well, what kind of work can you do? I could only work as a stoker, or something similar. But someone wrote a letter, it went to the KGB, they checked—you’re an unreliable person, there’s an order from above to fire you. And who can you complain to—to God? So you look for something else. Then I got a job through someone in the third department of the hospital, in the maternity ward. There were two people working there, which made it easier for me. So I would pay them money for my shift, and they would cover for me. But I had to show up from time to time, at least so the doctors and everyone else could see that I was at work, because they were also being watched.

Question: And did they know that you were a priest?

Father J. Kavatsiv: Yes, they knew, because you couldn’t hide it. No one would know about someone who doesn't work anywhere, but he who works is seen. But there were also such priests... For instance, Voronovsky boasts a lot about being an underground bishop—but he never celebrated a single Divine Liturgy for anyone in the underground. He didn't even celebrate a liturgy on his own mother’s deathbed. He would move a wardrobe, behind which there was a small table, he would celebrate the liturgy, slide the wardrobe back—and he was an underground priest. Well, I would not want to be such a priest, and I would not boast now of having great merits in the underground. And there were dozens of such priests and bishops who never worked anywhere—they would just celebrate Mass for themselves, pocket the intention offering… Because the offering had to be brought ready-made to his house, from whoever gave it to you.

I do not belong to that group—I’m not bragging, but I worked everywhere. Priests celebrated Mass in private homes, and so did I. Many churches in the Stryi region, in the Yavoriv region, in the Horodok district, in the Peremyshliany district were deregistered. But they didn’t turn them into warehouses—which means there was some reasonable village council chairman who just turned a blind eye to it. The people opened the churches themselves and entered those churches themselves. Father Roman and I would go to such churches and celebrate church services there. Thousands of people would gather for those services.

For example, in Stryi, when I celebrated Mass in Kolodnytsia, people from Stryi, from Drohobych, from Stebnyk, from Hai-Vyshni, from Hai-Nyzhni—all those villages, they all came there. They already knew what time the liturgy would be, they passed the word to one another, and everyone gathered.

For many years, for example, I celebrated Mass in the cemetery in Zavadiv. And that Berezdetsky, who now carries the blue-and-yellow flag—he should be hanged somewhere in the square! For his godlessness, for his communism, and for the evil he did. He was terribly furious with me and persecuted me so… People brought out a table (the cemetery is way out in the field there, in this Zavadiv). They just brought the table to the cemetery, I hadn't even laid out my things—and already the KGB and the police had surrounded the cemetery. But I didn't back down because there were a lot of people. And I knew their powerlessness; when there are people, they can’t do anything to me. The only problem was how to escape among the people afterward, how to hide among them somewhere—that was the main thing. And it was very simple—the best way was with the women. Men don't have such tongues, and the KGB men didn't really bother the women. Because a man, you know, was at work somewhere, but what could he do to a kolkhoz woman? So they let their tongues loose, pulled me into their midst, led me to one house, and then through a pantry to another—and I disappeared. Then the people watched to see where the KGB and the police went, so they could lead me out by another road. When I left Kolodnytsia, I didn't go back the same way, but went out somewhere else, near Drohobych, on another road. And they knew it; they searched for me everywhere during and after the holidays.

Such was my work. The work was very dangerous and very difficult because there was no time to sleep. Sleep only happened on the bus, perhaps. I worked most of all in the Yavoriv region. There was a chairman of the raion executive committee there named Ivanchenko. And the church had stood in ruins for about 56 years. It had developed cracks, no one paid any attention to it anymore, they had given up on it. It was an old church; we used to celebrate Mass in it. It was 700 years old, an architectural monument. A huge number of people gathered there for the services. But since winter was coming, with rainy weather, where could you accommodate all those people? Okay, I could get my head under cover—but where were the people to put their heads? So I made a suggestion, that maybe we could repair the church a bit and move into it. It didn’t take much convincing. Within a year, the church was standing, covered with a tin roof, painted, fully restored, everything. And that's maybe only about 12 kilometers from Yavoriv, as the crow flies.

Question: And which village is this?

Father J. Kavatsiv: That’s Muzhylovychi. That Ivanchenko knew all about it, because he was told everything. But he didn't touch me. We were on good terms with the school director; if I was driving, I would pick him up, and if he was driving, he would pick me up. He had a lot of trouble later when I was on trial, because the trial was mostly about that village, about that church. For them, building a church was a great evil. We consecrated the church, and commissions from Kyiv came one after another. Bolshevik power, communism—and a church was built.

In Lushkovychi, the people also had no church, because it had burned down sometime before or during the war. They built a church for themselves; I consecrated that church and celebrated Mass in it. This village, Cherchyk, is right next to Yavoriv. One woman, very deaf, wore a hearing aid. Her family abroad sent large sums of money, sent her parcels—she gave it all for the church. I consecrated it and celebrated services there.

Ivanchenko knew all of this. One time, after we had consecrated the church in Muzhylovychi, on Christmas Eve, the one before the Epiphany holidays, around 9 in the morning, a “bobik” drove up with about four KGB men and four policemen: “Get in with us, let's go!” I made a bit of a fuss because I didn’t want to take off my cassock—I used to walk around in a cassock. These were villages where I walked around in my cassock. At a time when a priest didn't have a cassock, had no idea what a cassock looked like, I allowed myself to do this, because the people were very drawn to it, and the authorities remained silent about it all.

Remark: That's like walking around with a flag.

Father J. Kavatsiv: Yes, they were silent. Long story short, I got into that “bobik,” they brought me to Yavoriv...

Question: So they brought you in your cassock?

Father J. Kavatsiv: No, they told me to take it off, they tore that cassock off me, I was just in some kind of jacket or coat, I don't remember, some shoes—right after the liturgy. They bring me in, and everyone is there—the prosecutor, the head of the KGB, in short, twelve men, the entire district administration. And they press me from all sides. It wasn't the first time I had to talk to them, because the KGB had dragged me in many times, I knew what to say to them, how to say it, and how much to say, and what could be said... That was in 1979. They tormented me there until about three o'clock. They all dispersed, and only Ivanchenko was left. He stood up from his chair (it was maybe six or seven o'clock), looked to see if anyone was in the corridor, turned back, and said to me: “Father Josaphat! I value you immensely”—this from the chairman of the raion executive committee! I froze, thinking: is he in his right mind? “Everything you have done is a historical document and a historical fact. It will never be forgotten. And I promise you that if I live to see those times—because things will not stay like this, there will be better times—I will bring you to Muzhylovychi in my car and carry you in my arms to the altar.”

You know, I’m thinking: is he joking, or is this the end? Because I had been convicted before, so I already know their tricks. He asks: “Do you have any money?” I say: “No, because they took me unexpectedly.” He made a call, summoned his driver (in Yavoriv, the bus station is at the edge of town, and the center is deep within the town), gives me 10 rubles, and tells the driver to take me there. He says: “Find yourself a bus or a taxi—that’s your business—and go home.” I've been hungry all day long, you know, it’s Christmas Eve. I get home around ten o’clock, because there were no taxis; somehow I managed to get from there to Lviv by bus. I arrive—there's no one at home; I don't know what to do next.

Another fact about that Ivanchenko. When I was already in prison, my sister came to visit me and told me that he, that Ivanchenko, had shot himself. He had been in some Ukrainian organization somewhere in Ukraine. He was from Eastern Ukraine. And either in Kyiv or Lviv, there was some big meeting of high-ranking officials. A woman who knew about his underground Ukrainian activities recognized him and said: “So you hid yourself as the secretary of the party's raion committee?” And he wasn't a child; he understood what could happen next. He came home, went into a room or his office somewhere, and shot himself.

Remark: I served in Yavoriv, I know him.

Father J. Kavatsiv: You know, he was an extraordinary person. Whoever asks me, I always mention him, because he is a person worth remembering. We built three churches in his district, and he kept silent about it. Isn’t that heroic on his part? And he told me: “You have no idea how many denunciations were written against you! But they all went into the trash can; none of it was ever filed.” It’s a pity about him, you know. But he probably knew the whole policy and the system of the Bolshevik government well and knew how it could end. Maybe he wasn't ready to stand up for himself, or maybe his mistakes were too great, so he ended his life by suicide.

That was one incident. And there were many such incidents. We worked the most in Mshana—that’s the Horodok district. The church was deregistered, we did some repairs there, and a great many people gathered. They were all Catholics—there were no Orthodox or anyone else. On December 8, 1977, when the children were in school and the people at work, 16 cars full of police and KGB agents arrived and smashed the church. There were such carved iconostases, carved icons. The church was about 400 years old, and everything was carved. It was a marvel, Mr. Melen, you can’t imagine... They chopped it all with axes, carried it outside, and burned it. Some things they took away somewhere, to some museum in Horodok, where they were later destroyed. When people found out about this and rushed to defend it, they set dogs on them; the dogs bit people, women; the screams were terrible. Long story short, six months later they completely destroyed the church, the main altar. They turned it into a warehouse. From bottom to top, they packed it with picture tubes for televisions—they had a television factory in Lviv.

And I, along with Father Roman, would place a table at the doors of that church and celebrated Mass there almost every Sunday to support the people. A great many people would gather for that service, and one time, perhaps two years later, in 1979, the people couldn't bear it any longer—everything that was in that church, they threw it all outside. On December 4, the feast of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Temple (it’s the parish feast day), I am celebrating the Divine Liturgy. The service has just ended, but the village council chairwoman, a terrible woman—she called Horodok some six times for the police to come. And the secretaries were Catholics—they told us all about it later. The police were in no great hurry, so she then declared: “If you don’t come and sort them out, I will immediately call Kyiv, Moscow, everywhere. I see that you are collaborating with them!”

I am finishing the Divine Liturgy, and people come up: “Father, a whole car has arrived—the entire administration from Horodok is already at the village council!” And there’s nowhere to run. First of all, I have never interrupted a service by fleeing—never! And there's nowhere to flee anyway, because that church is the last building at the end of the village, and here is a farm. Well, where will you run—to the field? And the village is behind. I finished the liturgy and am saying the supplications when I see—just red hats standing behind me. The prosecutor is there, the chief of police, the head of the KGB—twelve of them in total are standing there, and only one took off his hat. I went into the little room, the sacristy, where the censer was—what to do? I say: “Send the women in here, I'll start putting my things away slowly, because I feel sorry for these things I have.” And so each woman (since it’s December, it’s cold) puts the phelonion under her kerchief, or the sticharion, or the chalice, this, that—and slowly everything was carried out. “And now what do we do?” “Now,” I say, “get all the men—from the threshold to the royal doors—let them all huddle together in one group, with the women on the sides, and I will walk out—surely they won’t tear me away from them.” And indeed, they were loyal enough not to do that. We went outside, six of them stood on one side, six on the other. I slowly walk out; they are all standing there. The people are arguing with them: “You’ve ruined our feast day, for shame, and look what you’ve done to the church.” Each woman has her own just demands for them. Long story short, the men led me out like that, all the way past the church and a little farther. That crowd of people, the women, led me here and there to some house, and sent word to a friend of mine, who drove some second or third secretary of the regional party committee. The car's windows were tinted, and they salute him—not him, but the car as it drives by. He arrives in that village, they salute him—and the whole village is surrounded by police to prevent me from leaving. But he arrived, and they told him which house I was in. I quickly put some kerchief on my head, pretending to be a woman, darted to the car, and got into the back seat. And he drove me from that Mshana all the way to Hrabivtsi in the Stryi region, because I had a Mass scheduled there. Is that not heroism? Not mine, but that of those people who exposed themselves to such troubles—losing their jobs, losing everything. And it happened like that more than once. It was actually those who worked in the regional party committee—mostly the drivers—they were very kind to me: whether it was to drive me somewhere or pick me up sometime. It was best for them because no one would stop them and ask whom they were driving. Who had the right to enter a regional committee car and see who was inside? And those were Father Vasyl's uncles, both of them, who worked for the regional party committee, driving such high-ranking officials. It’s all one family, and they helped me out in such situations. And there were, perhaps, hundreds and thousands of such facts.

How did this underground work succeed for me, and what benefit do I have from it? Firstly, during the underground period, after I got out of the labor camp, with my knowledge and my own funds, I brought 31 priests to the altar. I have no gratitude from them, with the exception of Father Vasyl, and there is Father Oleksandr in (Village name inaudible)—I value and respect them. I said that when I die, I don’t want anyone else at my funeral—only these two priests should bury me. But the others, who exploited my kindness, my goodwill towards them—to bring them to the altar, to sew cassocks and phelonions for them from my own material—they haven't shown their faces for ten, twenty years, as if they don’t know me. They don’t need that. I don't regret what I did, because I didn't teach them so that they would later honor me or carry me on their shoulders.

From Poland, from Krakow, two priests came with the blessing of Pope John Paul II. They needed to revive the Russian Catholic Church, which was once headed by Exarch Fyodorov. Many of those Russian Catholics, Dominican nuns and monks, were left. Since they are of the Eastern rite, the Western church did not want to ordain them as married men—only celibate priesthood was acceptable. And if they are already married, what can you do with them? And even now among us, tell them not to marry—they don’t want to, because they want to be married priests. Few want to make such a sacrifice as to be unmarried—that is a personal value and worth for each individual.

At that time, His Grace Pavlo Vasylyk used to visit me 2-3 times a week. I told him about this matter, and he said: “Father, let them come.” And these were mostly Jews who were baptized in my house, studied in my house; they had to travel here from Kyiv, Kharkiv, Vilnius, Kaunas, Riga, where they had their churches, their supporters, those Dominican Russians. The most important thing for them was that the liturgy was celebrated in Russian. I understand that for Russians, reading in Old Slavonic or Ukrainian—they might accept it as Christians, but the Russian language is dear to them. And if they are Russians, we must value them, because not all Muscovites are communists; there are good people too, whom we must treat normally. And they came and were baptized, ordained, and then I would sew them phelonions and cassocks. Because Father Vasylyk ordained them and left; was he going to stand there and teach them how to celebrate the liturgy? That became my function. I traveled and taught them, and I was satisfied with this. And those nuns were satisfied. They had all been in prisons, in labor camps—they were all sentenced way back after the revolution. They were abused; it was terrible. When they told me their stories, I was sometimes envious, thinking: Lord God, if only I could spend some time in prison, to have something to boast about. I didn't have to wait long—the time for that came too.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And how did it happen that you were repressed?

Father J. Kavatsiv: I was first tried in 1957 for my connections with His Beatitude Cardinal Josyf Slipyj. I worked as a senior accountant in the accounting department at the paper mill in Zhydachiv. And there in the town, half were Catholics, half were Orthodox. And the people were very generous. Someone wrote several times that Slipyj was in Siberia, that he was suffering greatly. Of course, he was suffering—what work could an old man do there to earn anything? I didn't have a big salary, but after finishing work, I would go in the evenings to all those Catholics, where they would gather, and I would ask, and the people were very generous, giving what they could—lard, sugar, flour, whatever was available then. Later, you could only receive a parcel once every six months, if you didn’t have any violations. But back then, under Stalin, you could send as much as you wanted. And I got involved in corresponding with His Beatitude Josyf, and so, time after time, every two or three days—I sent parcel after parcel. They found out about it. There was a certain Trofymchuk or Trofymyak in Zhydachiv, a chief dean, and in Drohobych there was a certain Savchak. They wrote a denunciation against me to the KGB. The head of the KGB in Zhydachiv even read that denunciation to me and showed me their signatures. They wrote about me that if they didn't arrest me, they would consider the head of the KGB to be collaborating with us.

I was arrested. I spent a long time in prison. Many witnesses were called, but no one wanted to confirm anything, and they only gave me three years of forced labor at the Stryi Woodworking Plant. There, I carried scraps in huge boxes to these huge piles—mountains—and overturned them there. You know, to go from being an accountant in the accounting department to doing such work for three years… And I wasn't in very strong health.

On March 17, 1980, I went to the Basilian Sisters for the Divine Liturgy. I am returning from the service, I came home. And Father Roman was summoned at ten o'clock somewhere, to the Plenipotentiary for Religious Affairs. And before that, they had been constantly trying to persuade us: “Sign a statement that you will not celebrate Mass anywhere.” I said that I could not write such a thing because Article 124 of the Constitution guarantees freedom of conscience, and I have the right to celebrate wherever I want. If the Constitution changes—well then, maybe I will write something, but not for now. Around one o'clock, they call me from the Plenipotentiary's office, asking me to come there.

I went. He didn't talk to me for long, just gave me a form: “Sign here that you will not conduct any religious services from this day forward—you will not preach, nor baptize, nor hear confessions, nor marry.” And I took the pen and wrote: “In accordance with Art. 124, as a priest of the Ukrainian Catholic Church, I have the right to celebrate Mass, hear confessions.” I signed it and put the date. He said: “You are free to go.” I went home. I arrive at the house, I haven't even taken off my coat—and 14 of them have already come into the house. I was in the summer kitchen, the house was locked, and they rushed to the house, right away: “Your last name! Open the house!” I went and opened the house, they read me the prosecutor's warrant. And from two-thirty in the afternoon until seven in the morning, they conducted a search and took everything out of the house—absolutely everything that was there. Down to the last thread—whatever was there, they put it all into sacks, sacks, sacks, and they took it and carried it all away. They didn’t let me go anywhere, forgive me, except to the toilet, and he stood right next to me. Father Roman was walking around the attics, the summer kitchen, the cellar; they were searching there, writing something down.

At seven o'clock, a “voronok” arrived and they took us to Lonskoho Street prison. They held us at Lonskoho for ten days, and then threw us into Brygidki prison. I was under investigation for 11 months, there were 124 interrogations, a great many people were involved... Just think, he would summon me in the morning at nine o'clock, and I wouldn't get any breakfast, lunch, or dinner, because what they brought, we ate, and they wouldn’t give you more. It was like that three times a week. There was a man named Osmak, a senior investigator for particularly important cases. For putting me in prison, he became the prosecutor for the railway district of the city of Lviv.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And what article were you charged with?

Father J. Kavatsiv: It was 139, “illegal religious services,” and 209 was “infringement upon the rights of minors.” And what was I accused of? Telling them not to eat meat, telling them not to watch television, not to go to the movies. That is Article 209.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And how many years did they give you?

Father J. Kavatsiv: 8 years.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And do you remember the date of that trial?

Father J. Kavatsiv: I have the verdict. I can give you the verdict, if you return it to me afterward. I have one from Kyiv and one local one. Just for celebrating the Divine Liturgy, hearing children's confessions. After 11 months, they held a trial that lasted 18 days. There were very many witnesses. They had gathered those children because Osmak traveled to schools, to villages—for example, Kolodnytsia, Zavadiv, Muzhylovychi, Mshana, Pidlube, and others, and under dictation. The teacher would tell them to dictate that we know Father Josaphat Kavatsiv, who came to us, celebrated liturgies for us, told us not to eat meat, told us not to go to this and that—that’s what they wrote under dictation. But then, when they came to court, all the children denied it. But the judges said that their parents had coached them to say that, and it was not accepted.

M.O. Melen: And what was Berezdetsky’s role?

Father J. Kavatsiv: Ah, Berezdetsky’s role was this. He and that Udych, the one who was in Holobutiv, and that priest who was in Zhovtantsi, I don't remember his name, and that hero from Trukhaniv—they wrote all sorts of denunciations against me to the KGB and the prosecutor's office of the city of Lviv. When I got out of prison, Zenyk Kotyk was the Lviv city prosecutor then. I wrote him an application saying I wanted to review my case. He gave it to me for a whole day, placing a couple of men in the room. I picked out all those denunciations that Udych wrote, that the one from Trukhaniv wrote, whatever his name was, I don't know now—Illishevsky or something like that. I copied all of it. From my trial, seven large volumes like this came out. Seven volumes of the whole story!—of such a great criminal who told children not to eat meat, not to dance, and not to watch movies. And I say: “Well, that’s fine, a child won't cook food, but will eat what her mother has cooked. And what kind of child would go to a dance if her mother doesn't allow it, because she's not yet 14? There's no such law anywhere. But for them, that was the law, but not for me.

Long story short, I copied it all down—which volume, which page—and later published that data in newspapers. You, Mr. Melen, you know—you published it, it was published in Skole, in Kamianka-Buzka. They went around saying they would burn my house down, especially that Illishevsky. They caused me terrible trouble, just terrible. But I said: “Please go to the city prosecutor, get what's written there, refute it, and put me in prison for slander.” But no one has dared to do that to this day.

M.O. Melen: And was it possible just to request the case file and copy things out of it?

Father J. Kavatsiv: Well, the prosecutor allowed me to. It was the same prosecutor who tried me and demanded eight years of imprisonment, exile, and confiscation—I forgot his name. When I returned from the camp, I look—and he’s in charge of rehabilitation, sitting somewhere on the seventh floor. I go to him, I wait and wait and ask where he is. But he’s gone out for lunch somewhere.

(M.O. Melen's remark about the prosecutor's last name—inaudible.)

Father J. Kavatsiv: No, no, his name was something else... Dorosh! Dorosh was my prosecutor, and this Dorosh. I had come to him in my cassock, but you know, there wasn't yet that certainty. And when he saw me in the corridor—he froze! I entered his office and said: “Mr. Dorosh, please explain to me, on what basis did you do such-and-such!” And then he says: “I am not to blame—the KGB is to blame. The KGB did everything.” I say: “For God’s sake! You are a prosecutor, not some agency for which the KGB is higher than the prosecutor's office? You knew everything.” “Father, I respect you very much, I like you very much, and I felt sorry for you, but I had to give you as much as they wanted.” That's the story.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And which camps were you in?

Father J. Kavatsiv: That’s Sumy, Perekhrestivka. It was a terrible camp. They’ve now turned it into a special maximum-security camp, and it's all been rebuilt. But back then, it was an experimental zone, where they experimented on us. And then I was in exile in Uralsk. But I wasn't there long, because the “thaw” began, and I was already a second-group invalid—so what could they do with me? They released people like that.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And in what year did they release you?

Father J. Kavatsiv: Eighty-six.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Yes, that’s when the new wave started, “perestroika.”

Father J. Kavatsiv: Such a wave had come that they pardoned me. I served my prison term, and as for the rest of the punishment, the exile—they acknowledged that I was an invalid, unable to work—so why should they feed me for nothing? Go and feed yourself. The zone was terrible! The people there were terrible, I don’t even know if they were Ukrainians. Although from there, for example, the prime minister of Ukraine (I respect him) Yushchenko, they spoke Ukrainian there but wrote in Russian. They don't even know how to write in Ukrainian—everything is in Russian. I was the one and only Catholic priest there, and in fact, the only priest among that terrible gang, who didn't know how to speak in any words other than ten-story-high curses. To me, they would speak one way, but as soon as they turned away, they would curse among themselves...

Remark: Purely “po-russki” [in Russian].

Father J. Kavatsiv: Yes, purely po-russki. That, you know, was the worst and most painful for me. Never mind the hunger, the lice, the cold, but that was the worst. I was raised in a deeply religious family. We didn't use such words at home, and being a priest, you know... Who would dare among people—even someone who cursed, he wouldn't say such things in my presence. But there, they spoke like that even in their sleep, and one had to endure it all—it was terrible! Our “local zones” were always locked; they opened them only when we went to work and locked them when we returned from work. We had to work 12 hours a day at the job.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And it wasn’t just the prisoners who spoke like that, but the authorities too—the same way.

Father J. Kavatsiv: Well, the authorities—that was terrible. The one person there who didn't curse was Kyrylenko, the camp chief. I never heard a single such word from him. He may have respected me, and even liked me. I once went to him for some sort of appointment with a complaint. There were four rooms, a stool was nailed to the wall near the entrance, and he was sitting at a desk. He walked over, pushed a chair forward like this, and told me to sit down. And after I had come, he had no more appointments. He was interested in everything. There was a woman who monitored letters—the censor. But he was very cultured, he never once cursed in my presence—you have to give him that. And he never refused when I came to him for an appointment. I never asked for anything, but various injustices were done, they would torment us, because they were zeks, many of whom had several convictions. He always listened to everything, was always polite and considerate.

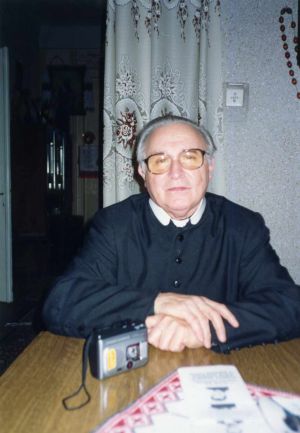

V.V. Ovsiyenko: May I take a picture of you as you speak?

Father J. Kavatsiv: Please. Thank you. One can talk about such things, but I don't even want to dream about them. Believe me, if I dream at night about some camp, about that cursing, I wake up and immediately turn on the light. And I tremble. Not because I’m afraid of it, but because my nervous system is saturated with that experience. I’ll tell you the truth—it was easier to be in prison under Stalin. Even where His Beatitude Josyf was imprisoned. Priests told me how they would gather for Christmas Eve, have a retreat, celebrate the Divine Liturgy. But with us, if they saw a tiny cross, even one made of wire, they’d immediately put you in the ShIZO. No one dared to make the sign of the cross on themselves—that's how terrible that experimental camp in Perekhrestivka was!

V.V. Ovsiyenko: You know, somewhere during a transport, they were searching Bohdan Rebryk, found a small cross, and wanted to take it. But he hid it in his mouth. They tried to get it out of his mouth. Rebryk bit off the major's finger. He was severely beaten. Rebryk himself requested that a case be opened against him for the bitten finger. The replies he received said that, well, all our majors have their fingers.

Father J. Kavatsiv: Well, that's how it is. My dear sirs, please believe me that there are no words—Mr. Melen knows this, and Mr. Vasyl knows it too—there are no words to express or to recount in detail and analyze deeply all the crimes they committed against us.

First of all, I am a priest. We go to work—they search us. What are you going to find, when the local zone is locked and no one can enter it? There's a fence eight meters high and another 12 meters of barbed wire with electric current—who is going to get in there? Nobody. We enter—a search. They strip this person and that person naked. You know, it's unpleasant—we are all human, but it’s a terribly unpleasant business. I’m not in a shower, or a banya, or a steam room, where I came to undress myself, or to the beach. It’s terribly humiliating, how they mock you there, everyone who wants to. There's this old warrant officer, whose son is a warrant officer and whose grandson is a warrant officer—and they’re all barely able to walk, but they curse terribly!

And the food? They fed us on eighteen and a half kopecks—morning, noon, and night. Our three meals a day cost 18.5 kopecks. Just imagine how one could live on 18 kopecks and what kind of food it all was.

And the laundry? In those prisons, the worst thing was the “propiska” [initiation rite]. That was something unbelievable. I used to say that when I get out, I will write a book, *Cell-71*. There were over 70 of us in cell 71. They did such terrible things, it's beyond human comprehension. How do they “initiate” you? Well, a priest was an exception—the priest wasn't “initiated.” I was the only priest, and it was my second time in prison. By the way, after me, no other priests were imprisoned—I was the last victim of the Stalinist or Brezhnevite terror. So, forgive me, I'll give you a crude example. They ask what you will eat—sugar from the slop bucket or jump from some sheet from the top bunk. He says, sugar from the slop bucket. So what did they do? Forgive me, one of them would take a dump, sprinkle sugar on it—and tell him to eat it. Would you believe such a thing? And it wasn't the Bolsheviks doing this—it was all done by the zeks who were the leaders in the cell. The hazing—it was terrible! They instilled such fear that everyone trembled from it all. Or they would give you a piece of laundry soap—you had to eat it and wash it down with water. And the slop bucket, excuse me, doesn't work because there's no water anywhere in Lviv, especially on the seventh floor of a prison. Water is supplied after midnight, and a person is dying from it all, and they beat you as much as they want. Such bandits they were.

M.O. Melen: The morality of "homo sovieticus."

Father J. Kavatsiv: Oh-oh-oh!

V.V. Ovsiyenko: When Danylo Shumuk, who served a total of 42 years, 6 months, and 7 days, was asked if he felt psychologically free, he said: “I probably will never be free, because prison dominates my dreams.”

Father J. Kavatsiv: That’s right, that's true! Those terrible transports, those dogs, those Poltavas, those Kharkivs—the train arrives, and there are 22 men in one compartment! Can you even imagine that or not? They crammed 22 men into one compartment. The slop bucket, excuse me, only at six in the morning and six in the evening. But we are people, we ourselves know when we need to go and when we don’t need to go. They wouldn't give us water—those goons walking around, he wouldn’t have given a glass of water even to his own mother. Your throat would get so dry that you couldn't find saliva to swallow. And then when we arrived, those dogs, that kennel—my God, the dogs are barking, people are falling, and they're lashing them with those whips and beating them! In that banya, only cold water and no windows, everything broken, iron bunks and nothing to cover yourself with—so where does good health come from now? Of course, everything hurts me; I have a bunch of all sorts of illnesses. I just spent 64 days in the railway hospital. I was going to the Divine Liturgy and then returning there—they found nothing healthy in me, everything in me was sick! Both the liver, and the sugar, and the blood pressure, and the heart, and what have you. And what could it be healthy from, when everything was ruined?

So it's not for praise. I thank God that I became that victim—I’ll tell you the truth. I think to myself that in this way, I was able to make a small contribution to the freedom of the Church and Ukraine. And that, you know, comforts me. Despite what those KGB agents were doing on St. George’s Hill—driving away those bandits and finding some justice… I have no heart for them, not even for a single poppy seed. I used to think, Mr. Melen and dear sirs—I thought that when I get out of the camp... Maybe I'll get out someday, because I was dying a hundred times—a blood pressure of 260/160, and I still went to work, nobody excused me, you have to work—they didn't care about anything. You, they would say, did you come here to rest? We weren’t people, we were excluded from humanity, and there is no such concept as humanity there. That is, you are outside the law, people who can be treated worse than an animal—because you wouldn't even hit a cow, you wouldn't hit a dog, because, you know, somehow you feel sorry: maybe it hurts? But for them, nothing hurt when it came to us...

I thought, God, when you tell someone about this someday—who will want to listen? Nobody will want to listen. Yes, I told the story when I was in Częstochowa and met with Lubachivsky; he listened to me, but then they didn't let him listen to me anymore, they wouldn't allow me near him. And Huzar listened to me. But no one else ever listened to me—they didn't want to listen! As my Medvid said: “And who asked you to sit in prison for the Church? You shouldn't have sat, no one forced you!” And Datsko told me this: “One shouldn’t be a fool—you should have served the KGB, and you would be a gentleman today.” That's what my Datsko said, and that's what my Medvid said.

M.O. Melen: Just like he did?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And who is he—Medvid?

Father J. Kavatsiv: Medvid—he's a bishop in Greater Ukraine, an exarch of Ukraine. He’s in Kharkiv, he’s in Kyiv. He's the one who told me that! When he told me that, I couldn't say anything back to him. Believe me, I just stood up, offered my hand, and left. I couldn’t even say, “Be well!” Because I will not respect you for the rest of my life. Because if you had served time—I'm not saying a lot, but at least one day, if all those wise guys had served one day and at least saw what goes on there, and then were released the next day—that would have been a lesson for them. But they were not there—they were sleeping in feather beds and enjoying whatever they wanted. And they did not count us as people. And now we are nothing to them. We are nothing to them—they have taken all the positions of power for themselves, they have ensconced themselves in all the governments. If you have money, you are master of the situation.

Father J. Kavatsiv: And here, for example, is Father Vasyl. He was thrown out of school, they didn't allow him to enroll anywhere. From the age of 18, the boy had to go to work because he had the strongest connections with me, as he was with me every day. And they knew all of that. They were persuading him when he was already 30 years old... So, when I came back from the camp, he drove me everywhere possible. To Kamianets-Podilskyi, beyond Kamianets-Podilskyi, then through the villages, like this: to work during the day, and in the evening (I was already, you know, less energetic—I still traveled, but less) and at night the boy didn't sleep all night, he just drove me, drove me here and there. I died in his arms three or four times. Then I took him in, he studied under my guidance, finished what he had learned from me, then graduated from the Ivano-Frankivsk Theological Institute, and Bishop Vasylyk ordained him a priest with the blessing of Cardinal Lubachivsky, as he was traveling to Rome.

And what do you think? He has been a priest for almost ten years, and for ten years he served with me with nothing—no official document, no blessing, nothing. No one gave him anything. It was only this past year in April, when Huzar came, that I told him everything. He said: “Please come—I will issue a gramota [official document].” And so he issued a gramota for Father Vasyl. And he is faithful to me, you know, we live as one family from beginning to end—because what would I do alone? These are different children, devout, they go to church, they pray, receive communion, go to confession. They knew all that before they even went to school. And so it remains to this day—not a day goes by that the children are not at confession.

And the greatest service to me was rendered by Tetyana Protsyk, Father Vasyl's mother, because she has been with us for 30 years now. She used to come to the camp, but they wouldn't let her in because she was a stranger—only for a visit through the glass. But she would wait for those three months like it was the most important thing in the world—just to talk. And to send a little parcel, or something else—her own mother was old, 80 years old, and what could she do—she was senile, just sitting and waiting for death. But she always helped me and helps me now, and now she is with us—we all live as one family, because we have nothing to divide and no one to favor over another. To find a companion and a friend in life who is behind you—that is great happiness. And there are those who just grab the priesthood, get their jurisdiction—and so long, I don't know you anymore. That's why Father Vasyl is very good and devoted to me; he helps me a lot with whatever is needed—he even gives me injections, because nowadays try to pay for all that and call someone or even ask someone, not many will come and do it for you. You’ll go once, but the second time you won’t, because you'll be a little, as they say, embarrassed. But that's life.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: This was Father Josaphat Kavatsiv, a priest of the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church. This conversation was recorded in Stryi with the assistance of Myroslav Melen and his friend. Recorded by Vasyl Ovsiyenko on February 3, 2000.