I n t e r v i e w with Hryhoriy Mykytovych O M E L C H E N K O

V. V. Ovsiyenko: The narrative of Hryhoriy Mykytovych Omelchenko, recorded on April 5, 2001, in Sicheslav (Dnipropetrovsk), in his home. He is the last pilot of the Dnipro, 83 years old. Unfortunately, he has great difficulty hearing. His address is 85 Yasnopolianska Street, phone number 67-18-36. I was brought here by Tamara Zavgorodnya. The recording is by Vasyl Ovsiyenko.

There are a number of publications about the last pilot of the Dnipro rapids, Hryhoriy Omelchenko: "Ukraina Moloda" of July 27, 2000, a full-page article "The Dnipro Rapids," by author Serhiy Dovhal. In the newspaper "Dzherelo," January 14, 2000, No. 1 (171), page seven, "The Legendary Pilot," by author Volodymyr Sobol, a regional historian. In the journal "Zona" No. 13, 1998, there is a large feature titled "Through the Death Camps," from page 20 to 45, recorded by Mykola Chaban. In this journal, Hryhoriy Mykytovych Omelchenko talks about his imprisonment from 1948 to 1954.

H. M. Omelchenko: I was born on January 22, 1911, in the village of Lotsmanska Kamyanka—a settlement of the pilots of the Dnipro rapids, into the family of a hereditary pilot, Mykyta Omelchenko. My great-grandfather Yakiv lived to be 105, a hereditary pilot and fisherman. His son Oleksandr—a hereditary pilot and fisherman. My father, Oleksandr’s son—a hereditary pilot and fisherman. We lived our entire lives by this profession on the Dnipro and in the fields. We had land because the pilots were also peasants; they cultivated it, and as soon as navigation opened, everyone went to the Dnipro. Before the rafts appeared, they fished, and when it got warmer, they got on an oak boat or rafts and guided vessels, timber, and rafts through the rapids. And so it went until about September. Then the water turned cold, and this season ended. That's how we always lived.

I remember myself from the age of three. Why three—because I remember the beginning of the imperialist war, and I was born in 1911. My first visit was to Stanovyi Island—it's not there anymore. My grandfather and grandmother would go there on Trinity Sunday to mow sedge and took me with them. That was where I first saw a roe deer and a hare; it was my introduction to nature. That is seared into my memory; I remember all the details to this day. As a village boy, I helped with all the household chores, and from the age of five, I started herding cattle. From the age of seven, I helped in the fields—guiding the horses during plowing, sowing, threshing, and harvesting. All my childhood years were spent in these tasks. Later, I mastered all the agricultural work and worked all the time, including three years on a collective farm, from 1929 to 1933. And in all those years, I did not receive a single kopek, not a single grain—nothing. It was unpaid slave labor. In 1933, people started dying, and I was reduced to a skeletal state. I left the collective farm, and everyone else left, only a few remained, and I went to study—at least they gave a hundred grams of bread there.

I finished the four-grade school by 1921, but the famine of 1921 stopped my education. The schools reopened after a year or two, but I had already outgrown them. In 1929, an evening school opened for those who had interrupted their studies, and I graduated from it. I went to the preparatory courses of the Institute of Professional Education and in 1932, I enrolled in it. Later I transferred to Dnipropetrovsk University, to the socio-economic faculty. Attached to this faculty was a geology and geography department. There were frequent changes then, and this department was eliminated. I was the only non-party member in the faculty. The only one. Everyone was either a party member or a Komsomol member. My father was a believer and did not allow me to join the Komsomol. And I didn’t want to go against my father, to destroy the family, although some did.

In 1935, I transferred to the geology and geography faculty of Kharkiv University and graduated in 1937. All the subjects I had completed at the socio-economic faculty were credited to me; in Kharkiv, I studied only those disciplines that were in the curriculum of the geology and geography faculty. So in two years, I received a diploma as a teacher of geography and an assignment to the Melitopol Agricultural Institute—they had evening courses—as a lecturer in geology and geography. But since they couldn't provide me with an apartment right away, they advised me to take a few hours at a secondary school, which would provide housing. So I simultaneously worked during the day at the school, where I had a few hours, and in the evening at the institute.

After some time, I was invited to the Palace of Pioneers. The oblast was Zaporizhzhia, but the Palace of Pioneers was in Melitopol, because there was a building for it there. I was completely devoted to regional history work, and this distinguished me among all the teachers. After three years of regional history work with students, I won first place in the oblast and third in Ukraine; my club was awarded 36,000 rubles and a two-week trip through Crimea. Such was the distinction.

This regional history work ran through my entire life. Later, wherever I worked, I would create regional history clubs and work with them. And even when I retired, I still worked in schools. This took up most of my time, more than teaching hours, but I had no regrets. I often checked—taking any number of days and months—where I worked more, and it turned out that I worked more extracurricularly.

That was my teaching activity before the war. I was working in Melitopol, and in 1940, I was invited to the Zaporizhzhia Pedagogical Institute because they had learned about my regional history work. Besides, I was writing an essay about Khortytsia Island, its geographical location. The essay and some articles were published. They invited me to the pedagogical institute as a geography lecturer; they were planning to open a geography faculty. I resigned from the Palace of Pioneers and came to Zaporizhzhia. But due to a shortage of students, the faculty was not opened. So they advised: work somewhere for this year, and next year we will assemble a group and then we will take you. Out of ten schools, I chose a new one on Khortytsia Island and worked there for a year. I launched a large regional history project, in particular, I proposed to the regional department of education to organize a student expedition from Zaporizhzhia to Perekop, following the tracks of Wrangel, to collect historical regional material and publish it with the students' efforts. This idea was supported, and in 1941, I set off with the students. It was impossible for one school to cover the entire route, so we did it in relays. My section was 46 kilometers from Khortytsia Island to the village of Bilenke. I collected a wealth of material—historical, regional, and folklore. Incidentally, literary figures had gone before me; they too were tasked with collecting folklore, but they said: the people know nothing—you ask them, and they say: “We don't know any folklore.” Inexperienced young teachers, while I already had experience in this matter. I collected a wealth of material.

So, I corresponded with all the schools in advance, with the oldest grandfathers, and recorded everything from them. The expedition of the Academy of Sciences, which was working on Khortytsia Island, acknowledged that my school museum was richer than the regional history museum.

The war caught me on the path of this student expedition, near the end of the journey. My mobilization paper said: "Appear upon summons." Some were summoned on the first day, others on the third—it was all planned in advance for mobilization, who was to appear. But mine said, "upon summons." I thought, maybe they'll call me today. I put the children on a steamboat, and we arrived at the island. A week later, I was mobilized.

First, I ended up in Sevastopol. At the university, I had completed higher military training in the specialty of "artillery." I immediately became a gunner there; we defended Sevastopol from air raids. After Sevastopol, I ended up on the Kalininsky Front, from Kalininsky—to the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Baltic Fronts. After the hospital, I ended up in Ukraine, and after that, they didn't let me go back to where I had served, in the 221st division, but sent me to the disposal of the staff of the 3rd Ukrainian Front. I arrived at the staff of the Ukrainian Front in Odesa, and from there I was sent to the 60th artillery division, right to the bridgehead seized on the Dniester in the forest, where preparations were underway to break through the Romanian front. And we prepared skillfully there; after a four-hour barrage, in which I also took part, we went on the attack and captured 12 Romanian divisions, and Romania withdrew from the war.

From Romania, I crossed the Danube and ended up in Bulgaria. There, I crossed the Danube again into Hungary. In Hungary, I participated in the encirclement of Budapest. A large group was surrounded there. But Hitler withdrew five mountain alpine divisions from France and sent them to break through the encirclement of Budapest. At night, we took up a position, camouflaged in a cornfield. The tank crews didn't notice us; they came with their hatches open, without fear, not expecting that there could be a screen here. And until then there wasn't one—we had been moved here at night. Letting them get within a hundred meters, we opened fire. We destroyed seven tanks, and the rest turned back, damaged. We were victorious. Three kilometers from us, in the city of Székesfehérvár, was the front headquarters, and this group was supposed to destroy it. They didn't know that we were just a handful.

A week later, our battery was moved from the southern side of the city to the northern side, because the Germans went on the offensive again. Two of our guns were destroyed in this battle, and with the two remaining guns, we fought back until we fired all our shells.

V.O.: And were you a commander of some unit?

H.O.: I went from a gunner to a gun commander, a platoon commander, and a battery commander.

V.O.: And what was your military rank by then?

H.O.: I became a battery commander as a lieutenant. And my commanders were senior lieutenants. The Germans advanced along two flanks, afraid of running into an artillery screen. We found ourselves surrounded. What to do? Communication with the division was cut off. Tanks, artillery, and mortars began to shell us, guided by the flashes. But at night, it’s hard to determine the distance by fire. And in the daytime, they would destroy us with aimed fire. So we removed the firing mechanisms and optical instruments from the guns (all the shells had been fired), took the anti-aircraft machine gun for air defense, and went down into the river valley. The bank was steep. The Germans passed by us and didn't notice. And then we saw a light. I sent two scouts—they said it was a folwark, a landowner's estate. I positioned the machine guns and submachine gunners and sent them to scout in detail whether there were any soldiers there. If there were, they were to throw a grenade and retreat immediately, and we would open fire from above. It turned out there were no Germans. We entered the house, posting a guard. The landowner had fled, only the farmhands remained. Among them was a Czech, and I got all the information from him. During the day, he had seen columns passing by. We found ourselves in the enemy's rear.

I was struck that everyone here was an adult, there were no children. I ask: “Aren't there any children among you?” And I said "children" in Hungarian. Just then, the cellar trapdoor opens, and a little head peeks out. I say: “Come to me, don’t be afraid”—and the child climbed out. And after her, several more kids. I had a lump of sugar in my pocket, I divided it into four parts, and gave it out. The soldiers searched their pockets and also started treating the children with sugar. The master saw our friendliness, the mistress brought a bucket of milk, and we each drank a mug, rested a little, and then set off to the right of the city. After walking 42 kilometers, we reached the front line and rejoined our unit. That's how we broke out of the encirclement.

After a while, we received new guns. As part of the 3rd Ukrainian Front, I fought in Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Austria. I have medals for the capture of Budapest and Vienna.

After the end of the war, we were moved from Austria to Bulgaria—our forces wanted to seize the Bosphorus and Dardanelles from Turkey for letting the German fleet through. But England and the USA declared: a war with Turkey is a war with us. And our side yielded here. We stood there for four months, forty kilometers from the Bosphorus and Dardanelles. In 1946, demobilization began.

I wrote to the People's Commissariat of Education to be assigned to the pedagogical institute in Zaporizhzhia. But the Zaporizhzhia institute was not functioning; it had been destroyed, and classes had not yet resumed there. I was appointed director of the Bratske Pedagogical School in Mykolaiv Oblast. But I only worked there for one year, because the following year I was arrested and sentenced under Article 54-10 to 10 years. For what? The pedagogical school had 120 correspondence students from the villages. They would come for seminars, for sessions, for exams. And so, at one of the sessions, when we were gathering the students, only 80 out of 120 showed up. I was surprised: how could they not come? I knew that three correspondence students were supposed to come from a certain village, so I ask: “Why did you come alone—where are the others?” The student mumbled something indistinct. But when everyone dispersed, he approached me and said: “The teacher who was supposed to come with me is swollen.” I say: “What, a teacher?” — “Yes.” — “Why, how could that be?” And he says: “A teacher in a village receives two and a half kilograms of flour a month, and only for himself, not for his dependents, and he has a wife and two children.” This means they received it, ate it—and then what? The local teachers somehow survived the famine: one had a cow, another had sheep, another a goat, another had vegetables stored—they had something. But I, for example, demobilized, had nothing of my own, and yet I received a good salary compared to others—more than a thousand rubles, but a loaf of bread cost a hundred rubles, a bottle of oil a hundred rubles, something else a hundred rubles. Once, my wife comes back from the market and says: “I’ve just spent half your salary.” She started listing things; everything was expensive. She was a teacher and received only 400 rubles.

V.O.: You mentioned a wife—when did you get married? And please tell me your wife's name.

H.O.: We had known each other for three years already; there's a photograph—my wife and I. We got married when I was assigned to Melitopol, and we went there as husband and wife.

V.O.: And what is her name and maiden name?

H.O.: Oksana Yakivna Kovalenko. She graduated from the pedagogical school in Dnipropetrovsk. Her surname was Kovalenko. And she remained with her own surname. We decided that both surnames were good. So we lived as Kovalenko and Omelchenko.

V.O.: So, you were telling about the bloated teacher.

H.O.: I was so struck by this that I went to that village. According to instructions, the director had to periodically visit the raions to check how the district education departments were helping the teachers. They were supposed to consult the correspondence students, to help them. Groups of teachers had been formed. And under this pretext, I went to that village. I enter the raion education department, and through the ajar door, I hear a conversation. One voice says: "How can we take them in, we can only take one, where would we put two? Well, do as you wish, we can't take all of them." And I understood they were talking about children, so I open the door and say: "Excuse me, what are you discussing?" — "And who are you?" I say: "I am the director of the pedagogical school. I have correspondence students. I came to check on the work with the correspondence students and I hear you're talking about children." And he says: "A widow, her husband died at the front, she's bloated, and three children with her are bloated, barely alive, nothing to eat." — "Why are they bloated, didn't she work anywhere?" — "She worked for a whole year at the collective farm, received 60 grams of grain per workday." This outraged me: how can you give 60 grams for a workday, when a person needs kilograms?! And she wasn't alone—with children, and her husband died at the front. I insisted that they take these three children into the shelter. They had created so-called children's shelters for children on the verge of death. But you couldn't take everyone; if it were only a few cases—but it was a mass phenomenon. So I insisted that they take these children; I made them put them on the list, but I wondered if they would follow through. And with a heavy heart, I went to the oblast education department.

At the oblast department, as soon as I opened the door, a woman and two children were sitting there, all swollen—their eyes were just slits, and they were all crying. I ask: “Why are you crying?” She says: “How can I not cry, when they won't take my children into the priyut [shelter].” Such an old word, priyut. “Let me die, but at least save the children.” I started to inquire—the same story. Her husband died at the front, she worked at the collective farm, received 65 or 70 grams per workday. They ate that up over the winter, no matter how they economized, and now—death. She asked people to give her a ride to take her children to the shelter—they wouldn't accept them.

I was thinking of going straight to the obkom [oblast party committee], but I had business at the oblast education department. Who could I turn to? I read a sign: "Chairman of the Trade Union Committee." Aha, here’s the one. I open the door, but the door doesn't open. Not that it's completely shut, but it gives a little, and then no further. I pushed and pushed—it wouldn't open. So, in my agitated state, I kicked it—the door flew open. The chair that had been propping the door fell, and the person on the chair fell with it. They had propped the door with a chair so no one would enter, and the room was full of people. They all stared at me, and I at them. I ask: "What is going on here?" — "Who are you?" I identified myself. "So what do you want?" I say: "At the entrance sits a bloated woman and two bloated children with her. Help her! Her husband died for you to be alive!" Everyone is silent, listening. "Or perhaps I should go to the obkom if you are not capable?" Then one of them, Horovets, says: "Comrade, we didn't know about this, forgive us, we will definitely help her. We will finish our meeting now and help her. There's no need to go to the obkom." — "Well, fine, help her."

I went to the head of the oblast education department on business. An hour later I come out, and those three are getting ready to leave. I ask: "Did they help you?" She says: "They gave me seventy rubles." My God, what is 70 rubles? They'll buy a piece of bread, not even a whole loaf, eat it—and that's it, the end. I was terribly outraged, but there was no one there anymore. And I had to go home.

I came home in the evening—and I couldn't get what I had experienced and seen that day out of my head. I didn't have classes for the first two periods in the morning, so I thought I'd go in later, and I'm preparing for my lessons. The door opens and a woman comes in: a face like this, legs like this, swollen, and eyes like slits, and in such a deathly voice: “Give me a piece of bread.” And there wasn't a crumb at home, nothing; we ate whatever we had for dinner, and in the morning, until you get something, there’s nothing. I reached into my pocket, took out 10 rubles, and gave them to her. She took the money but didn't leave. I can't work, and she doesn't leave. We stood in silence for a while and she says: “Give me at least an onion, a carrot, a potato.” I say: “I was demobilized last year, we have nothing, we live off the market, and our salary is not enough even for food. And right now there's nothing in the house, I'm sorry.” She stood for a while longer and left, and I couldn't work anymore, I was so struck. After my lessons, I sat down in the evening and wrote a letter to the Central Committee about the starvation death of children, described all those cases, provided addresses. "It cannot be allowed for children to die—they are our future, our replacement. Take some measures."

And they took measures: three months later they arrest me at the post office; I was writing a letter somewhere. They had kept my letter—they were good at analyzing handwriting. They compared the handwriting, then ordered an expert examination and established that it was I who had written the letter. I hadn't written it secretly, but openly; I even went to the post office and asked: "And how does one send a letter to the Central Committee?" — "By regular mail." I say: "It's an extraordinary letter." — "It doesn't matter what kind," they simply informed me. And I dropped it into the mailbox. Maybe I should have done it differently.

V.O.: Did you send it to Kyiv or Moscow?

H.O.: To Kyiv. Kaganovich was the first secretary then.

V.O.: Yes, "the leader of the Ukrainian people."

H.O.: Yes, the "Ukrainian." And he was replaced by Khrushchev. I don’t remember if he was in power then... But neither of them ever saw the letter; they kept it right here until they found me.

V.O.: But the letter was signed with your name?

H.O.: I signed my address. We front-line soldiers were so naive; we thought, we’ve endured so much, why should I hide when I'm pouring out my soul? Besides, I knew that one could write letters to any authority. And I was a party member. At the front, no matter how I twisted and turned, I had to join the party, and in 1943, I became a communist. So as a communist, I have the right to express my opinion—that's how naively I thought. They arrested me, having first expelled me from the party.

V.O.: And when were you arrested?

H.O.: October 27, 1947. And in February 1948, I was tried. They held me in the Mykolaiv prison for three months without summoning me. I realized they were checking to see if I was connected to anyone, looking for accomplices. I had a front-line diary; they took it during the search… Only then did I realize how vile these people were and how vile the whole government was. During the search, they took all the most valuable things. My watch was bought, not a trophy. Bought in Bulgaria for 1000 leva, Swiss-made. And I bought one for my wife too. And they took these watches. Another fact. My wife lost a gold tooth. Her godmother hadn’t spared a cross for the tooth. They put in a gold tooth, but a normal tooth started growing out from under the gold one. So the doctors removed the crown—to let the natural one grow. She kept that tooth in a handkerchief in her jewelry box. They found it during the search and unwrapped it. The head of the NKVD smiled, exchanging a glance with the others. I say: “You think I pulled out a tooth? This is my wife’s tooth.” And I told them the story. And they smiled so maliciously, as if they'd caught a criminal. So, this tooth, the watches, my officer’s dress uniform, several meters of material—all the most valuable things we had, everything was taken. The officer's boots too. Those boots—they later said—were seen on the head of the village council. My shotgun—it was a personalized gift—was taken by the head of the MGB. And the rest they divided among themselves. To be so vile! They know that if I’m convicted, it will be without confiscation of property, because I didn't steal, I didn't squander, there's no economic crime, it's a political article. Knowing they'd convict me without confiscation, they divided my things among themselves. No matter how much I demanded later, I appealed to all authorities—they summon me: "What do you want, to be jailed again?" Just like that, sternly. I say: "How dare you?!" — "And how dare you demand it from me, when I'm not involved in this?" — "But you are the person responsible for this." — "I am responsible for nothing—all the items that were inventoried followed you; address your inquiries there." He's lying, nothing followed me, nothing arrived at the camp. Such baseness, such people were ruling us then.

After three months, they tried me. At ten o'clock at night, in the basement, the prosecutor, the judge, a secretary, and a supervisory judge arrived. They said there was no article for writing a letter, so they were trying me for agitation against the Soviet government.

V.O.: And what was the number of that article?

H.O.: 54-10, part one. It was the lightest one—10 years in the camps. After the Dnipropetrovsk transit prison, where I stayed for a month, a transport was sent to Siberia. We stopped in Omsk, I worked for a year in logging, in a construction brigade, and then—Komsomolsk-on-Amur. From Komsomolsk, I was sent to an active logging camp. We walked all day, made camp at night, cut down trees, lit bonfires, and slept by the bonfires. We'd spend the night and walk on during the day. And we entered such a wilderness—this is the basin of the Amgun River, where Gryzodubova and Osipenko made their long-distance flight and landed; they were found only a month later. Not a soul for a thousand kilometers. We cut down the forest there and built barracks and roads. First, we'd build a barrack for the guards, then a kitchen, and then for ourselves. When our own was built, we'd pack up again and move on, and so it went, all the time.

From Komsomolsk, I ended up in a logging camp, and then they started recruiting specialists for construction. I had been a construction brigade leader in Omsk, so here I signed up as a plasterer and painter. They brought us to Komsomolsk at night, where I worked all winter, and in the spring—on a transport to Sakhalin. On Sakhalin, I was in logging the whole time, and then they made me head of the timber exchange. We were building a pier across the Tatar Strait. That's when I had a good laugh: how illiterate our scientists are. They wanted to build a pier from Sakhalin Island and from the mainland at the narrowest point of the Tatar Strait, 9 kilometers. To make a two-hundred-meter opening for ice and ships to pass through. And here, a train was supposed to approach on the pier, get onto a railway ferry, and be transported to the other pier. It all seems correct. But the manager always had a shortage of timber, and a big one. The question is: this is not a densely populated region where every board, every log costs something—there's as much timber as you want, yet there's a shortage… A driver would give half a bottle—and for a week they'd write that he was hauling timber. They warned the camp commandant that if there were more such shortfalls, he would be fired. And so he started consulting with his assistants, even with some prisoners, and one of them says: "Just put a decent man in charge, not an alcoholic and not one of those recidivists—and everything will be in order." And they suggested there was a man named Omelchenko.

By the way, in the camp, they called me "the novelist." It was the first time I heard such a word. I had broad knowledge, I read a lot, knew many interesting stories. And there, there wasn't a single book, no radio—a complete wilderness. One evening, they asked me to tell a story. I had listened to some storytellers, but it was all rather primitive. But I had a good, clear voice and knew a lot.

My most popular lecture was "Ivan Sirko." I knew his story almost by heart. I would tell how he carried out his sea campaigns, how he sacked Trapezund, Sinop, Gazli, freed seven thousand captives, how he kept them safe so they wouldn't be killed during battle, how he tricked the Turks. The Turks gathered their entire fleet and sent it to the mouth of the Dnipro. The ships stood a hundred meters apart. No matter how brave Sirko was—he was finished here. Sirko understood this and went not to the Dnipro, but to the Sea of Azov. At night, they crossed the Kerch Strait into the Sea of Azov, dug a channel through the Molochnyi Estuary—a spit of land separated it from the sea there. As soon as the water started flowing, they moved their boats in, and with thousands of men, one-two, they pulled all the boats into the Molochnyi Estuary. And into the Molochnyi Estuary flows the Molochna River, which comes close to the headwaters of the Kinska River, which flows into the Dnipro near Zaporizhzhia. Well, of course, the "chaikas" and "baidaks" were not as cumbersome as the Turkish ships, but still quite large for a river. They pulled them along, digging here and there. And in this way, to save the treasure—for Sirko had captured the Turkish fleet, loaded all the goods onto his ships, he was carrying incredible riches with him. They had plundered three cities, freed seven thousand captives, and safely departed. But what an intelligent man he was! "The Turks might think the same way I do—what if they send a strong, armed flotilla up the Dnipro and destroy the Sich?" Because at the Sich, there were essentially no Cossacks. And the Turks did just that. They waited and waited, waited and waited—no Sirko, and they thought there must have been a storm, they must have drowned. And the Turks were already in a place where there were no storm winds; they went up the Dnipro right to the Sich itself. And who was left at the Sich? The crippled and the old, the unfit, fishermen. They saw the Turkish ships and started firing at them with a cannon, destroying several ships. The Turks went on the offensive, arrived—and there was no one at the Sich, everyone had hidden, because they knew the secret passages. The Turks set the Sich on fire and returned home.

But, leaving the Sich, the admiral of the fleet thought: what if Sirko broke through and is now coming down the Dnipro to the Sich? A meeting on the Dnipro would be dangerous: Sirko has nimble chaikas, fast-moving, and I have such cumbersome vessels… But they tell him that such a meeting can be avoided. And how? There is the Kinska River here, which flows into the Dnipro, and the Kinska comes close to the Molochna, and the Molochna flows into the Molochnyi Estuary of the Sea of Azov, and from there through the Kerch Strait. And they chose such a plan too! But Sirko was a man of foresight—to stand here with two thousand Zaporozhians against a ten-thousand-strong detachment of Turks! This stuck in my memory the most; I read about it several times.

So, Sirko sent several hundred Cossacks on reconnaissance. Two small boats are sailing, with fishermen and nets, one has no hand, the other no leg, on a crutch, slowly sailing along. In case they meet the Turks—who needs them? And those cripples saw some army approaching and informed Sirko. Sirko immediately led all his men into the forest, several kilometers from that spot; they hid all the boats and lay in ambush on both banks of the river. And then two Turkish boats appear. They let them pass, sail on. Behind them, two small galleys, and then the entire fleet. They let these small ones pass, and when the main forces approached—they were attacked from both sides. A hand-to-hand battle began. Well, there were more Zaporozhians, and it was a surprise attack—they killed everyone, and some surrendered. That's how Sirko defeated them and returned home safely.

Well, I'm telling the main points, but I used to talk about it for two hours. And wherever I was, whatever I talked about, everyone would ask: tell us about Ivan Sirko. I would tell about Suvorov, about Bagration, about some other brave people. I had a theme "Hryhoriy Neznamov," and there were two detective stories: "The Red Mask" and "The Black Mask." The bandits would always demand those—they were fascinated. Because I had heard some primitive versions… And I would add my own; it became broader. So I developed a cycle of lectures. One of the most detective-like was "Karakuto Island"—the Japanese name for Sakhalin. How two of our geologists ended up there and were urged to defect to the Japanese. They staged an escape and managed to return. The chase after them with dogs was a very exciting story. Such was the cycle of lectures.

V.O.: So you became such a "novelist"?

H.O.: A "novelist." When I first arrived on Sakhalin, as soon as we set foot on that land, they opened the gates of the barrack for us—and prisoners came out to meet us. Two came up to me: “Are you Nikitych?”—that was my nickname, "Nikitych." I say: “I am.” They shake my hand. I ask: “How do you know me?” — “About you,” they say, “the whole GULAG knows, in all the camps.” People are moved around; it's rare to stay in one place for a year or two; they're always sent off so people don't get used to each other. They say: "The whole GULAG knows about you,"—that's what they said about me in front of people.

And so the camp commandant summons me, says: "What is your education?" I say: "Higher, graduated from two universities." — "Haven't learned to steal?" — "No. I," I say, "want to preserve myself as I am. I am an educator, I don't have much time left, I will return to my work." He offered me the job of head of the timber exchange. He asks: "Can you manage it?" I say: "I've never done it, but if others have managed, I can too. I'm somewhat familiar with timber, and I'll learn how to calculate." So I became the head of the timber exchange and had a 24-hour pass. At any hour, day or night, I could leave the zone and walk as long as I wanted. This gave me at least a little freedom. I spent almost all my free time in the forest, observing everything. And once, I was picking berries... I brought berries every day and gave them to those who were sick with scurvy. I had scurvy myself twice. Until then, I didn't know that not only do your teeth fall out, but your whole organism rots, and often it's not the teeth, but the legs and arms that stop working. And so one morning I get up—my legs won't hold me. I could barely walk a bit—and sat down again. I didn't go to work; I went to the doctor, I say: "My legs aren't working for some reason; I didn't hit them, nothing." — "Undress." I think: "Why undress?" I undressed, he felt around, looked—"You," he says, "have scurvy." I say: "But what do legs have to do with it? The teeth..." — "It's not just the teeth," he says. "Scurvy affects other organs too. I am helpless. If you know any herbs, and you go out to work, drink some vitamin-rich herbs, because we have nothing." I knew that pine needles contain vitamins. I asked for a tin can from the kitchen, I'd pick pine needles, boil them, and drink this pine-needle tea two or three times a day. It was bitter, worse than wormwood, it stank—and that saved me, I got back on my feet and didn't let scurvy happen again. But my friend Kostya Vinogradov, a former raikom secretary—he was imprisoned for poems, and poems can be of all sorts—was eating fish and a bone damaged his gum; the gum began to swell and turn black. We hadn't seen each other for several days because we were in different brigades, and then I saw him bandaged and with a cane. "What's wrong with you, Kostya?" — "It's the end, Nikitych." — "What do you mean," I ask, "the end?" — "You see, here." — "And what happened?" — "Scurvy." I say: "You'll be dancing tonight, don't worry." I brought a pot of berries, gave him a mugful, and gave the rest to the others. And one day, I saw very large blueberries, almost like plums. I was surprised, picked some from the edge, stepped further—and my foot sank into something. What is it? I cleared it away, and there were—bones. I took a stick, poked it—it went deep. And I understood: they had dumped corpses into some ravine, piled them high, covered them with a little earth—and that was it. The earth settled, the corpses decomposed, merged with the soil, and so this lush growth of berries began. I brought that pot, and they were already waiting for me. I say: "Scurvy sufferers, come get some berries." I measured out half a glass for each. "So large! Where did you get such big ones?" I say: "They are so large from the blood of our brothers." And I told them everything. A week later, the operations officer summons me. "So, where did you pick such large berries?" I told him. "Take me there." — "Alright." We went. He looked, poked around. "There," he says, "the bastards. They did the deed but couldn't hide it, the fools." And he cursed out his own people who had let this be discovered. "Listen, not another word about this to anyone. You yap—you'll be here too," he said so crudely. I say: "I won't, because there won't be any more such pits." For a decree had come out to stop the executions. Before, for any reason, for the slightest offense—execution. The task was to shoot a certain number every day. It was a terrible regime, and no one was held responsible for it. But then a decree came out: "Investigate every death and sentence the guilty." They saw that there would be no people left, they'd kill them all; they were dying by the millions in freedom, let alone in the camps. And the executions stopped. I tell him: "There won't be any more such pits." — "We'll see," he says, "we'll see." Such was the conversation between us. Three days later, they take away my pass, and a week later this operations officer sends me to Kolyma.

V.O.: So what year is this happening?

H.O.: This was happening in 1953. I'm put on a transport. They brought 650 of us to the mainland. More arrived from other camps, and we find out that a transport to Kolyma is being prepared. "Are you serious," I say, "to Kolyma with 'children's sentences'?" The most terrible criminals were sent to Kolyma, those given 25 years, and here most had already served half their terms. They called 10 years "children's sentences." And I had already served seven. And so we arrive at a camp—they don't take us out to work. We just live. Roll call, lineup, and then we lie around, resting. One "parasha" [latrine bucket/rumor] after another—the things they would invent. Every day—if only one could have written it all down, we'd have a good laugh. "A special commission is coming, they'll be selecting so-and-so." Or another one: "The concentration camps are closing, but they won't send everyone at once, it'll be in parts." The things they would make up! And then, finally, we learn for sure: a transport to Kolyma. Prisoners are being gathered in this camp and will be sent across the Tatar Strait, across the Sea of Okhotsk, to the Kolyma River. In the evening, my closest friends come to me—there were six of us: a geologist from Izmail, Kostya—the former raikom secretary, Abramov—a captain, imprisoned for disclosing state secrets. When they liquidated Blyukher, and with him the entire high command, some little fish got caught in the net, including him. They interrogated him and said: "Alright, you're clean, but not a word to anyone, not even your wife, or you'll get what they got." The army was literally decapitated then. But one day he up and told his wife that so-and-so had been taken by such-and-such people. And she told her gossip-friend, and that one told another, and for that he got 15 years—"disclosure of a military secret." He had already served 10. All were such decent people. An economist. They came to me: Nikitych, this and that is happening. "I've already heard," I say. — "What should we do?" — "At any cost, try not to end up in Kolyma, because who knows if you'll return from there." And it's not Kolyma itself that's so terrible, but the transport. I explained what Kolyma is, what the seasonal winds are—for half a year they blow towards the land, for half a year from the land to the sea. The Sea of Okhotsk is calm only during two periods: for a few weeks or days in the spring and in the fall, when the pressure between the land and the sea equalizes. In the summer, there's a terrible pull from the sea to the land, because the air above it heats up and rises, and heavy air from the oceans flows into the void. And in winter—the opposite.

And so I met a prisoner who had been in the camp for about twenty years but didn't know what he was in for, what his term was, just living out his days. He had been imprisoned back in tsarist times, and now the Soviet government was holding him. He had accidentally been included in a transport to Kolyma. He got into the service crew. They prepared food on a tugboat, and then they would deliver it in tanks on a small boat to the barges. And halfway there, a terrible storm broke out. They managed to turn back on the boat. They didn't have time to deliver food to one barge; they said it was no longer possible. And such terrible waves rose up that the tugboat was like a cork—now sinking into a chasm, now being thrown up. It pulled the tow rope first to one side, then the other. And the captain ordered the tow rope to be released. And on the rope were three barges, each barge holding one and a half thousand people. And they released the rope… That prisoner was forced into the hold.

A terrible storm raged all night. The next day, the wind died down, but the waves were still crashing. He asked one of the sailors: “Listen,” he says, “what happened to the barges?” “Don't even ask about that,” he says. “Three barges sank—they were bumping into each other, being tossed back and forth.” I thought that the same could happen to us, and I told this to the boys. So that old man, who was part of the crew, was sent to the mainland by ship when he became unfit for work. And he’s the one who told me about the transport to Kolyma. “That,” he says, “is the most terrifying thing—to cross the Sea of Okhotsk. It’s the stormiest of all the eastern seas.” I knew this from geography, only I didn’t know about the prisoners; I had read about how seiners didn’t return from fishing, how they didn't make it in time. They were warned: abandon the catch and hide in the coves. They were notified in advance. Those who were closer hid, but those who didn’t have time perished. That’s what I knew about the Sea of Okhotsk, and now I was told even more.

So what were we to do? I said: “Let's agree on this. The six of us here will declare a protest: we will not go to Kolyma. First, the sentence doesn't state that we must serve our time in Kolyma, in the most remote camps. Second, they send those with the longest terms there, the twenty-fivers, for the most serious offenses, while all of us have short sentences, and some have only three or four years left. They have no right. In my opinion, they are sending this contingent there to release them as colonists, to serve as the service personnel they're short on. The prisoners work, and someone has to service them. Besides, they've opened radium mines there, and they send those with long sentences to them. After a while, they were written off as disabled; they died. And someone was needed to serve them. I propose we demand the supervisory prosecutor and declare that this is not in our sentences, therefore, they have no right to send us there. Everything should be done according to the law. If they still try to grab us and take us, we should link arms—they can’t lift six men at once—and hold on. When they call your names, don't step forward. When they've called everyone, they'll see that we haven't answered. We'll declare our protest that way. There is no other way out.” And so we agreed.

We were in different barracks. The next day, everyone was lined up; the whole camp was brought out. “Abramov”—that captain came out. I walked up and said, “What about you, Dmytro?”—and waved my hand like this. A guard said, “What do you want with him?” I said, “I needed something.” After a while—“Vinogradov.” I said, “Kostya,”—I moved closer to him—“what's going on?” “They've assigned me to the service crew, and they'll be unguarded there. That’s already,” he says, “half-freedom.” Well, alright. And so they called everyone, and everyone went, but I stayed behind. “Omelchenko”—I kept silent. They called my name three times and read on. When the last one came, they led that column away and sat them down on the ground a hundred meters away. “Gather the whole camp!” From all the corners, from the roofs, they gathered all the invalids, lined them up, and went through the alphabet again. The list reached me, since ‘O’ is far down. “Hryhoriy Mykytovych Omelchenko, Dnipropetrovsk, ten-year term,”—I reported everything as required. “Why didn't you answer?” I said, “Because I have less than half my term left, and I’ve already been told that they will release me this year.” The camp chief told me this: “You will be released because they requested a character reference from me, and I gave you the best one; I've never written one like that for anyone.” The commission came twice: however much timber I had accepted, that’s how much timber there was. That’s how it was. Until then, everyone insisted you couldn't get rid of the problem of lost timber. But it was possible. That's why he was so good to me. I told them this. They whispered among themselves for a bit, then the chief ordered, “Take him.” Two men approached and grabbed me. I sat down. They lifted me and started dragging me. After dragging me a short way: “Get up, why should we drag you the whole time.” And here, the gnarled root of a fir or larch was sticking out, and it had a loop in it. I hooked my hand into this loop. And I sat there, saying, “I’m not going.” “Then we’ll twist your arms off.” “Go ahead and break them.” I was very strong in my arms back then—no matter how they pulled, no matter how they twisted, I held on. “Why can't you manage him…” “The bastard just won't go, that's all.” The convoy commander ordered something—and two men came toward me with dogs. One was a black dog as big as a calf, and the other a gray German shepherd; one was in front of me, the other behind. “Either you get up, or they'll tear you to pieces right now.” “Let them tear,”—and I held on. The dogs reared up on their hind legs, just centimeters from my face. If I barely failed to hold on, my face would be gone. I shut my eyes. That was the most terrifying thing—the dogs. I wasn't afraid of the men. The dog behind me tensed and grabbed my shoulder. And all the people—both those already in the column and those remaining—cried out, “A-a-a-a!” The dog grabbed my shoulder, my quilted jacket, and ripped out a chunk, but its teeth grazed my skin. I screamed in pain. All the camp prisoners, all of them shouted in one voice, “What are you doing, you bastards, how dare you abuse him!” They were quieted down. “Are you going to walk?” I said, “No.” Just then, three women with baskets were walking by, probably not convicts, maybe they had come to visit their husbands, probably on their way to pick berries. They came up to the wire fence, watching what was happening. Two soldiers with automatic rifles approached and fired a burst into the air—of course, but everyone thought they were shooting at me. Then those women started shouting too: “What are you doing! We'll report you to the authorities right now for killing a man!” And they walked away. The chief immediately ordered, “Get the dogs away.” The dogs were taken away. “Listen, old man, tell us, why don't you want to go?” The camp chief came over. “Tell me, will you go?” I said, “No.” “Evseev, Bagrov,”—he named two men— “take him, carry him away.” Two huge guys came up, with hands like shovels—but they couldn’t tear me away from the root. They pulled and pulled… “What's the matter with you two, get four men and carry him.” And then the representative from Kolyma intervened: “Stop!” They stopped. He walked up to me. “Listen, batya,”—I had a beard like this, and even older men called me ‘batya,’ I have a picture of it—“listen, batya, tell me, why don’t you want to go to Kolyma?” “I,” I say, “am a geographer. I know that the sailing season for the Sea of Okhotsk is over; you are already late. I know that during severe storms, not all steamers, let alone transport ships, make it. I know how many people have drowned. I get motion sick in a car on long rides—how will it be in the hold of a barge, tossed from side to side? Do you need a corpse? Make one right here.” And then he said, “Alright, stay here.” He went to the camp chief and said, “I'm not taking this man.” “But we'll carry him there right now.” “Carry him wherever you want, I’m not taking him.” I don't know what influenced him, but he refused to take me. My God, all my strength left me at once—my arms went limp, and everything inside me just dropped. I thought, “Lord, where did you come from, man: to endure such a fight—and then he refused.” They gathered the rest, led the column out the gate, and Kostya Vinogradov shouted, “Nikitych, hold fast!” I shouted back to him, “Report immediately as soon as you arrive in Kolyma.” “Will do! I remember the address.” He remembered my address and got it out. And Abramov split the visor of his cap, put my address inside, and then glued it back together with bread—you know what camp bread is like—so it wouldn't be found during a search. So they knew my address.

I stayed in that camp for three months. Three months later, news of my release arrived.

V.O.: And when were you released?

H.O.: I was released in 1952, I think, in March.

V.O.: So, still under Stalin?

H.O.: After Stalin's death.

V.O.: But Stalin died in 1953. You have it written down as 1954.

H.O.: I made a mistake, it was in 1954, in March. What helped my release? My older brother was a colonel. He was summoned to Moscow for a promotion in rank and position. He met an old comrade from his army service, from when they were both soldiers. That man had already become a general, while my brother was a colonel. Very modest, shy, quiet-quiet, but an exceptional hard worker. And when they met, the general said: “Misha, I'll take you to Moscow, you'll be in my department.” He summoned him to Moscow, he went through all the channels, everything was signed. He got to the MGB—“brother of an enemy of the people.” And they removed him from there and didn't take him for the new position. Where could he go? He went to Kovpak—and Kovpak was then in charge of the rehabilitation department—and told him everything. He listened and said, “If everything you've told me is true, then he'll be released, but if it's a fabrication, then, excuse me, we can't do anything.” “Everything,” he says, “that I've told is true.” He told him everything that I've told you.

And so a request came to the camp chief in Sakhalin: provide a character reference for such-and-such prisoner. Because it happens that people commit crimes in the camps. And that chief, because I behaved so well (and I didn't drink, wasn't corrupt, a bottle couldn't sway me), gave me a very good character reference. He told me he had never given such a good reference to anyone. And when they were sending me on transport, he said to me: “You will be released.” And I told this to the others, but they said, “Oh, who knows what he'll say there.” This helped me get a reduced sentence—I served seven years, not ten. That was my great offense.

When I was released, they told me: “You are released with your conviction expunged; you can say everywhere that you have no criminal record.” And although I sometimes hid it, I mostly said that although I was convicted, my record was expunged. Nowhere would they hire me, no matter how many times I applied. I’d find a job—“Okay, alright”—and then they'd turn me down.

And only in 1961, when it turned out that I was rehabilitated, did I become a teacher at a night school, and two years later its principal, because I did have more experience than others, and more knowledge. I became the principal.

V.O.: And where was that school where you became the principal?

H.O.: In this village, in my own school. But I didn't stay principal for long. During the long break, a group of students came up, maybe 5-7 of them. They had been arguing and arguing, unable to prove their point to each other: “Hryhoriy Mykytovych, tell us, was Mazepa a traitor or not?” I said: “You can't say that unequivocally. Come after class, but I'll tell you right away that Mazepa was never a traitor to Ukraine. Whether he was to Peter or to Russia—that's their business, it doesn't concern us here, but Mazepa was not a traitor to Ukraine.” A week later, they summon me to the district party committee. “How can we leave you in such a position when you exhibit political illiteracy?” I said: “I don't know which of us is politically illiterate, but I know that Mazepa received the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called from Russia for his participation in the Crimean and Turkish wars, and the Order of the White Eagle from the allies. He served his Fatherland faithfully. As for Peter—that's a different relationship. But Peter is not Ukraine.” That’s what I told them. A week later, they summoned me to the district education department. “We are dismissing you from the position of principal by order of the district committee.”

And I went to be an ordinary teacher at School No. 61, worked there for five years, and retired from there. But even in retirement, all these years that have passed, I worked with some school every year. I was a mentor, gave lessons in local history, nature lessons, lessons in courage, lessons in ethnography—I visited almost all the schools. Even in kindergartens, in vocational schools, in technical colleges, and twice at the university—the university invited me to talk not about the camp, but about the book I had written. I gave a lesson at the agricultural university, and several times at the Mining Academy. So I'm working all the time.

V.O.: But what year are you considered to have been in retirement from?

H.O.: I retired in 1970.

V.O.: And what do you talk about with the students?

H.O.: I wrote two books: “Memoirs of a Dnieper Rapids Pilot.”

V.O.: And what year did it come out?

H.O.: In 1998. "Sich" Publishing House. For it, the regional Writers' Union awarded me the Dmytro Yavornytsky Prize. And last year they published a second book—“Dnieper Knights.” Almost everything is a repeat of the same, with a new topic added: “The First Otaman Musiy Pivtorak, a Zaporozhian Cossack Sotnyk.” There are two more books unpublished—there are no funds.

V.O.: And what are these unpublished books about?

H.O.: “The Steppes of Ukraine.” Essays about the steppes. And the second is also a memoir, from the age of three to the present day.

V.O.: And what will be the title of that book?

H.O.: Simply “Memoirs.” I should have started with it, and then I would have published the others long ago. I wrote it in 1985, started with the memoirs of the pilot, but for some reason, I left this one. I did the wrong thing—there's a gap: 1985, and now it's already 2001. For some reason, I kept thinking: will they publish it? And back then it could have been published, I had my own money then. Somehow I wasn't in a hurry. I lost 30,000 in the savings bank. I was saving all the time, thinking it would be for my old age, and when I needed something, I would take it. And it all disappeared due to inflation.

V.O.: And what about your wife, is she no longer with us?

H.O.: My wife died in 1995.

V.O.: And what children do you have, name them and their years of birth.

H.O.: I have two sons. Oleksandr, born in 1938, the older one, this is his wife, and the second was born after the war. In 1947, my wife was taken to the maternity hospital, and I was taken over there…

V.O.: What's the name of the second one?

H.O.: Volodymyr. So I didn't see Volodymyr until he was seven years old.

V.O.: And please tell me about your relationships with young people, with the creative youth of the Dnipropetrovsk region. Did Ivan Sokulsky come to see you?

H.O.: The Sokulskys visited me two or three times. I had great respect for Sokulsky. Doctor of Philological Sciences Popovsky, Mykola Petrovych Chaban, Matyushchenko—these were my closest friends. They visited me often and still do, and were at all my name-day celebrations, as was Tamara Zavhorodnya, who brought you to me. My circle of acquaintances includes writers, scientists from various fields, including Academician Hanna Kyrylivna Shvydko, a history lecturer at the Mining Academy.

V.O.: And in the sixties and seventies, did the KGB have any issues with you?

H.O.: Well, only the conflict over Mazepa, there were no others. By the way, I received a medal from the authorities last year. I gave a book to Bychkov, he's the head of the Zhovtnevyi district executive committee, and now he is Shvets's deputy and probably gave him my book. I haven't spoken with him, but I think the book made a strong impression on him, because for every holiday—Victory Day, other celebrations—I always receive gifts from the district committee, and I think it's at his request. In addition, I received a notice from the "Mazepa" publishing house that I have been included in the "Golden Book of Ukraine," they informed me. They wrote what I needed to add, and I would be included in this book. But it arrived in the final days, when the deadline had already passed. So, my relations with the authorities are good. And it was the regional administration that included me in the "Golden Book of Ukraine." I think Bychkov played a role, because he is now Shvets's deputy for culture. Relations with them are not confrontational for now, though they are tense with Shvets. I also created a museum of the pilots.

V.O.: Oh, that's interesting.

H.O.: I created a museum of the pilots in 1994. The head of the district executive committee and the then-head of the city council, and now the head of the regional state administration, Shvets, were at the opening of the museum. So before this celebration, they sent a People's Artist to me to consult on what to do and how to behave. He made a demand that I would present the bulava to Shvets, and he, as a descendant of Zaporozhians, would present a saber to me, because he believes that my great-grandfather Yakiv was of Cossack origin. Although it has not been possible to establish this, because those Russians burned the archives. We had very rich archives here in Kamianka—of the Sich, and the pilots, and church archives—all were burned. I could not establish exactly where my great-grandfather came from. But from questioning old pilots, he was also of Cossack origin. So I am of Cossack-pilot descent. Before the opening of the museum, I read in the newspaper that the head of the city council at one of the meetings of the heads of district executive committees gave each of them a Cossack hat, and he was given a bulava. By whom, I don't know. If it's a bulava, then someone of Cossack descent, a famous person, should be giving it, not some scoundrel who has nothing to do with either the Cossacks or the pilots. But someone was found to give it. This really angered me: on what grounds should they give Cossack hats to the enemies of Ukraine (and they are indeed enemies)? Well, give them devil's hats, horned ones, whatever hats you want—but why Cossack hats? Cossack hats are a symbol of glory, they belong to the Cossacks. People who are alien to Ukraine, who have no connection, are given such souvenirs! And Kuchma, and Shvets, and some city council heads, many people, received bulavas. Why are they being traded like some kind of goods? The bulava is a symbol of power, a symbol of Ukraine, and they treat it so lightly. When they presented this to me, I said: "And on what grounds must I give him the bulava? To whom? Is he a descendant of Ivan Sulyma or Polubotok, or some of the famous, celebrated Zaporozhians, Khmelnytsky, or whom? I cannot imagine him as either a hero or a true Ukrainian. This is the one who, in fact, ruined Ukraine."

I have my own concepts and my own reasons. I consider Ivan Sulyma the greatest of all the celebrated ones. Khmelnytsky is nothing compared to him. His friends from Khmelnytsky's register betrayed and destroyed him. The Poles quartered him. Now that's a hero. So I say to him: "Who is he? A descendant of these celebrated Zaporozhians? How can you give a bulava to a person absolutely unconnected with the past?" I refused. The artist was surprised, then said: "Don't you understand what this means for you?" I said: "I don't know what it means, but I don't want to seem like a traitor." So, of course, Shvets knew about this, and he didn't give me a single kopeck for my book. I did everything on my own, at my own expense. He never once pushed for its publication. As they say, I fell out of his favor. But Bychkov, Shvets's deputy—he, I believe, is the person who contributed to my inclusion in the "Golden Book." He took all the data from my book, and he knew it anyway, because I really deserve it. I have done so much in my life that twice I have been asked if I have ever met a person with a work capacity similar to my own. And I answered that I had not. I have never found an equal to myself in work capacity. I worked 14-16 hours a day, sometimes around the clock. In the war and during the harvest, I worked four shifts in a row. "Three times four"—that's a headline I have. I worked for four days straight. I haven't met anyone like that, but I worked. A day, two—no problem, there were countless such cases. I was extremely hardworking. So, he must have liked that, and he had all this information, and he probably submitted it—that's what I think. But I didn't get in because of the post office's negligence: they mixed up the address and sent it when the deadline had passed. Shall I show you the portrait?

V.O.: Please do. What's the story of this portrait?

H.O.: A man, a woman, and their son came to me, three of them, and said: “Our son is graduating from the art college, he needs to paint a diploma work, but we don't know what to paint. We just can't find anything good to paint from modern life, because there is nothing good, and we know little about the past. And so we were directed to you. Tell us who you are, what you are, what you know about the Cossacks.” And I told them. I said: “Listen, I have a manuscript, a book about pilots and the Cossacks. Take it and read it, because you will forget what I tell you, and I no longer have use for it.” And I gave it to them. A year later, he comes with this portrait. The son graduated from college with good marks and painted this portrait of Yavornytsky. Once Dmytro Ivanovych gathered his friends, they dressed him in this Cossack attire and photographed him. And in the house-museum, there is a small photograph like this. So he made the portrait from this photograph.

V.O.: And who is the author of this portrait? Tell me his name.

H.O.: Hrechanyi Stas. But, unfortunately, this young man died. He entered the Kyiv Art Institute, and one summer they were swimming, and he drowned.

V.O.: And how old was he then?

H.O.: About twenty-five years old, I think.

V.O.: And what year did he paint this portrait of Yavornytsky?

H.O.: One should know such things. Take a look, it should be written on the back.

V.O.: It says on the back: "Dmytro Ivanovych Yavornytsky in Zaporozhian attire (from a photo of the late 1890s). Painted by Hrechanyi Stas, 1996." And another inscription: "To Hryhoriy Mykytovych Omelchenko and his wife on his 85th birthday with best wishes."

V.O.: They write about you as a pilot, but you haven't said anything about it in your story. Tell us a little about it.

H.O.: I started being a pilot at the age of 16. Before that, I had been in the rapids, in my father's *dub* boat. My father, a pilot-*dubovyk*, would take tourists on excursions, raft timber, and as a boy, I sailed with him several times in the *dub* to get acquainted with the rapids. I started as a raftsman and an oarsman in the *dub* at 16. And from about 1926-27 until 1932, when the rapids were flooded. If the rapids were still there, I would have sailed, of course, because people sail until they are sixty. But the main reason pilots retire early is eyesight. You need to see far and clearly, because the entire passage through the rapids depends on it. If you see it up close, you don't have time to correct, you need to see it from a distance. I analyzed the most significant accidents, including the accidents during Mazepa's crossing of the rapids. He participated in the Turkish wars, Mazepa and Neplyuev—the commander of the Russian troops. They had huge losses in men and material values because the Dnieper was very shallow then, with little water. These were the biggest accidents. So I analyzed all these accidents of some famous pilots and came to the conclusion that the main reason was eyesight. The *partiionyi* is the senior pilot over the whole party of pilots and the party of rafts, there were about 15-20 rafts, and over them the *partiionyi* Ivan Kazanets—he was my mentor, I started sailing with him. He had accidents after the First World War because he was already old. I fought in the Second World War, and pilots of my age also fought, and only the old ones remained here. So he had two accidents, and some young people spoke disparagingly of him. I say: “Don't judge wrongly—he knew his stuff, he had the knowledge, it wasn't negligence—he couldn't see. And the currents change, various circumstances happen: the relief of the valley changed, and some other reasons, and all this needs to be seen. And he couldn't see it from a distance, and up close he wouldn't have time to correct. These were accidents only from a lack of vision.”

I was a raftsman, a *bobalshchyk* on a raft, many times I was in my father's *dub* and in others, I sailed in some 5-6 times, after several years of service I was the otaman of a raft, and in the last year I was already sailing as an assistant pilot. I piloted a raft independently, my mentor Savchenko Andriy Lukyanovych only observed, but did not interfere in anything and made no corrections. The next year they were preparing me to be a pilot, but the next year the rapids were covered with water. From Zaporizhzhia to Dnipropetrovsk, the water level became the same, the water rose here by 36 meters. That is, 36 meters there, and here 2 meters higher than it was before.

The rapids were a formidable phenomenon on the Dnieper, and only the desperate, brave, and courageous passed through them, and from them the team of pilots was formed. The first otaman was the Zaporozhian Cossack Musiy Pivtorak, whom Catherine renamed Poltoratsky. From that time on, everyone called him Pivtoratsky. Four generations of Pivtoratskys sailed through the rapids, piloting ships and rafts. And Pivtoratsky himself, for the skillful piloting of the tsarist flotilla... Catherine traveled with Potemkin in 1783, they reached Kamianka, and there the pilots took over the flotilla, and he flawlessly piloted the entire fleet without a single accident. For this, the Tsarina awarded him the rank of lieutenant, granted him a noble title, but none of the Pivtoratskys used it, because what did pilots need it for. Only one of the Pivtoratskys graduated from a higher military school and was among the guards in the protection of the tsar's palaces. But, as they say, no matter how much you feed the wolf, he still looks to the forest. No matter how he was involved with the nobility, you'd see him let slip somewhere: here's how we, the Cossacks, used to do it... He had no malicious intentions against the Tsarina and the tsarist government, but some reports came in, he was declared unreliable and exiled to Chisinau to serve. And Pushkin was in exile in Chisinau at the time, and they met there and became friends, and Pushkin called him one of his closest friends. And since he often wrote in verse in his letters, in response to an invitation from this Oleksiy Pivtoratsky to visit him—and apparently they had an estate there—he wrote: *“Когда помилует нас Бог, когда не буду я повешен, то буду я у ваших ног среди украинских черешен.”* That’s how he replied to the invitation to visit him. And their families were friends, and their wives, Oleksiy's and Alexander's, and they themselves, because the Zaporozhian spirit could not get along with the spirit of the quite natural Russian nobles. And here that Cossack spirit manifested itself. What else?

V.O.: I thank you for the conversation.

H.O.: You're welcome.

V.O.: Hryhoriy Omelchenko finished his story in Dnipropetrovsk, on April 5, 2001.

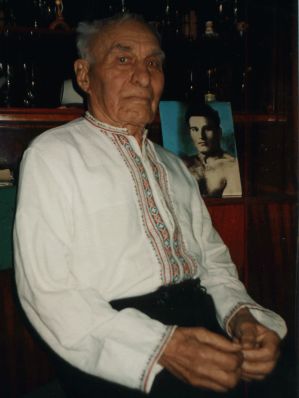

H.M. Omelchenko with his portrait from his student years. Photo by V. Ovsiienko, April 5, 2001.