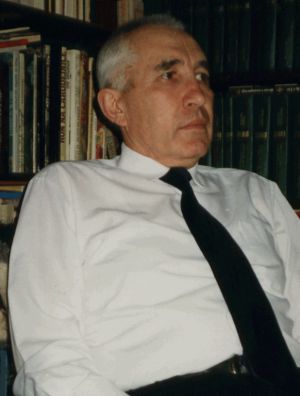

Interview with Yaroslav Ivanovych TRINCHUK

(On the KHPG website since March 23, 2008).

V.V.Ovsiienko: On April 2, 2001, in Sicheslav (still Dnipropetrovsk at the time), we are having a conversation with Mr. Yaroslav Trinchuk in his apartment. The recording is being made by Vasyl Ovsiienko.

Ya.I.Trinchuk: Yaroslav Ivanovych Trinchuk. Born on March 17, 1940, in Prykarpattia, the village of Stari Bohorodchany. A beautiful, picturesque village. Into a rural peasant family. A noble, hardworking family. We were relatively well-off, and our family was respected in the village. My father, Ivan Mykolaiovych Trinchuk, directed the church choir; he was a cantor. When he was young, the girls loved him, I was told. He had an exceptionally beautiful voice. He was killed by grenades thrown into a bunker in 1945, when he was 33 years old. He began fighting in 1939 in the Polish cavalry. You know, in 1939, Polish cavalrymen charged German tanks—well, among those cavalrymen were two of my relatives. That was my father and my uncle—my mother’s brother Ivan, who went missing in action. There were two men from Bohorodchany in the Polish cavalry. The selection process there was very rigorous. Like selecting cosmonauts. From the village, they selected two: my dad and my uncle—my mother’s brother Ivan. My dad’s older brother, my uncle Vasyl, died at the age of 39 in Stanislav. In 1939, the NKVD took him away. I suspect he was killed in Demianiv Laz.

My father’s younger brother, Bohdan, my uncle, fought in the Soviet Army. He was taken prisoner. He escaped from captivity. He was severely wounded and killed in 1945 at the age of 25. The killing happened like this. He was already in the UPA and was carrying a report when he ran into a roundup. They were firing from a machine gun. Several bullets pierced his greatcoat. He fell into a potato furrow—it was just at the beginning of summer. He crawled to a road that was in a small ravine. Not far away, behind a hill, there was a road. The machine gun couldn’t reach him there anymore. He stood up to walk along this road. But there was an ambush, NKVD men were sitting there. And one says: “Look, a Banderite is crawling. Let’s take him alive.” The other says: “What the hell do you need him alive for?” And he shot him right in the face with a pistol. It was Captain Belyaev who fired. They killed him and left him. He was still alive for a long time—because the potato patch around him was all trampled. It was the first and only legal funeral of an insurgent. The whole village came to the funeral. Later, they no longer allowed it.

Bohdan’s wife, Natalia Bortnyk, whom he had rescued from Germany, from behind barbed wire, came to us. Our family had great respect for this woman. Natalia said that this Captain Belyaev came to her and asked in Russian: “Where is your husband?” And she knew Russian, she answered: “My husband is fighting where everyone else is.” Then he saw a photo on the table and recognized the man he had shot. He went to the neighbors and said: go tell her to come and get him. I remember my father bringing my murdered 25-year-old uncle Bohdan home in a wagon. I loved him very much.

I was 4 years old when my uncle died, and 5 when my father died. I don’t know what came first in me as a child—love or hatred. Because they were killing my whole family. Before that, my grandfather had died. He fought in the Austrian army against the Russian army. His leg was shot off. He came home wounded, without a leg, and died later. My great-grandfather fought against the Poles—he also died…

Our family was good, respected, because we were hardworking. And because we were hardworking, we were also well-off. We had our own horses, our own forest. We lived, we sang, we knew how to enjoy life, as I was told. We felt life. We felt life better than we do now. Because now we feel a great deal of negativity from all sides, whether we want to or not. We may have more and better food than they had then. But then we didn’t have these negatives. Back then, they knew: this is the enemy, and behind your back is the one you must protect. My relatives understood this problem of protection well. My father voluntarily joined the UPA. There were three of us children—he left three children and joined the UPA. To the family’s credit: it was only when they cut off our land right up to our windows that my mother, the last one in Stari Bohorodchany, wrote an application to the collective farm to save us from starvation. But no one—not my mother, no one in the family—ever reproached my father for acting as he did, and not in some other way.

Why weren’t we exiled? They came to exile us many times. My mother would hide, and my grandmother would be in the house. My grandmother was 76 years old. They would come and shake her. I don’t want to tell a lie, God forbid, but I remember her uterus was prolapsed, she was in a terrible state. They would come to exile her: “Well, how are you going to exile me? Look at this…” They would curse at her, shake her. I can’t say if they beat her. But there was shouting, and I would rush to protect my grandmother. They came several times to exile us, but my mother wasn’t there; she was hiding. And so they didn’t exile us.

When I was 18 years old—I was a decent-looking lad, even though I grew up on meager rations—they summoned me to the district party committee. And one of the secretaries says to me: “We’ve been watching you, observing you.” What had happened was: I had beaten up the secretary of the district Komsomol committee at a dance. I beat him up because he was bothering me. And everyone was saying: oh, what will happen, oh, what will happen! It turned out that he was a real scoundrel. Everyone knew he was a scoundrel, and they were even glad that someone had beaten him up. Such a simple, mundane, banal event influenced my entire future fate. They called me to the district party committee with the intention of offering me a job and making me one of theirs. I say: “No problem. You want me to build a career with you—I’ll build a career with you.” — “But you have to write a tiny little note—no one will even pay attention to it. We’ll print it in small font at the end of the newspaper, that you renounce your father.” — “I do not renounce my father.” — “Well, write that your father was mistaken.” I say: “My father was not mistaken.” And two months later, I was in prison. I served six months. After six months, there was a retrial, and I was released. There was no reason to imprison me.

V.O.: You were imprisoned for that fight?

Ya.T.: No. The matter was different. About two years later, I was told that I was imprisoned for not wanting to renounce my father.

V.O.: State the dates when this was.

Ya.T.: This was in 1959. I spent the winter in prison and was released in the summer. It was three months in the Ivano-Frankivsk prison and three months in a camp called Tovmachyk in the Kolomyia Raion… I later drove past this camp several times. You know, strange as it may seem—it was a criminal prison, not a political one—but there were so many decent, noble people there. A driver who hit someone, someone who stole something, someone else who did something else. And the one who stole—he wasn’t a thief. There were very many good people there. I remember those conversations. I remember how they taught me. Later, in Kazakhstan, I had my academy, an academy like no other in the world.

V.O.: And what was the formal charge?

Ya.T.: I was in charge of a packaging warehouse. It rained, the bags got wet, many boxes turned black. They calculated a large sum—allegedly embezzlement. In fact, it wasn’t embezzlement, because everything was there, but it was spoiled. It was so stupid, not worth talking about. But they punished me. They charged me 18,000 rubles, which I paid off for 20 years. Do you understand what followed me? Two years later, they told me it was because I didn’t renounce my father. From then on, I knew their methods.

How was I fired one of the times? I want to focus on this because it’s a very interesting, comedic story. Before that, I had been fired from various jobs many times. To prevent me from engaging in pedagogical activity, they fabricated a charge that I had raped a student. And they wrote it in my work record book. I can’t recall all the cases now; there were many. When I was applying for my pension—and it took me 8 months to process my pension—my entire work record book was completely filled up.

I clearly remember one time I was fired. The one who fired me was Bykanova, now she’s Kravchenko. At that time, she was an instructor at the district party committee, and now she is the deputy head of the regional administration, under Shvets, for cultural affairs. Her friend, Lyudmyla Blokha, I don’t know her patronymic—maybe her father was a decent man, so I won’t mention him. But her name is Blokha. This is a detective story, a good one. I can’t find a job. And here we have a river port, there’s a dormitory for sailors—they drink and fight. There was a murder. And there’s no counselor. But according to the staff list, a counselor is needed to work with them. Like a psychologist now. The head of the human resources department at the river port is a former warrant officer, a real sea dog, a strong man. He also didn’t mince words, like our Kuchma. He cursed like our president. I come to him and say: “Here’s the thing—I want a job.” He says: “I’d hire you, but they’ll fire me because of you.” I say: “You know what, let me write an application for the job and at the same time write a resignation letter. If anything happens, you can fire me based on the letter. The letter is already there. And nothing will happen to you.” Because I needed a job, and he needed a person. He hires me as a counselor at the dormitory. I go to the dormitory: “Lads, I’m the kind of man who says, let’s just come to an agreement.” I had a request for them: when they fight, not to shout, and to take down the pornography from the walls and hide it on the inside doors of their lockers and nightstands. They asked me: “Are you with us or with the White House?” The White House was the administration. I say: “Lads, I’m with you, of course.” But it happened that one of them did something wrong, he needed to be protected, and I and this warrant officer protected him. I went to this warrant officer, the head of HR, and said: “We need to protect the lad.” He says: “No problem.” We protected the lad. They took down the pornography from the walls and didn’t fight as much. They drank a bit—lads will be lads. When they drink, they drink. And sometimes I even drank with them—there was nothing terrible about it. But they listened to me and brought some order. A little order, everything was clean, the beds were made, not a single indecent picture. Moreover, one even hung up Raphael’s “Madonna,” the one in Leningrad, the “Madonna Conestabile.” It had just been released in a print run of 200,000, you know. He hung it up for himself, in a nice frame. Such a picture above the bed—well, it was wonderful, the lad had good aesthetic taste.

So, listen to what happened next. A commission arrives to check the results of my work. And I’ve only been working there for a month—what can you do in a month? I see this Blokha poking around the rooms. Everywhere is in order, and she is terribly dissatisfied because there is nothing to find fault with. She enters this room and, when she sees this picture, she is overjoyed. I don’t know why she’s so happy. My spirit sank a little, I started to feel some respect for her, well, she was happy—she saw a work of art. I already see her as one of my own. But I see she has this kind of smile… “Yaroslav Ivanovich, and what is this Mother of God? Are you allowing them to hang icons?” I understood everything, and that smile too. I tell her: “Dear Lyudmyla,—I don’t remember her patronymic, maybe her father was a decent man.—This is Raphael, and by now every Negro knows that.” May the noble Africans forgive me, but that’s what I said. She twitched and ran away. She was gone, disappeared: there was a woman—now there’s no woman. She fled. It was funny to me, funny to everyone.

The next day I was a little late. After a month, I already had some authority. I could be late when I needed to, I could leave work early. Everyone is waiting for me. Right away: “Get to HR, quick.” I go to the HR department. As soon as I arrive, he yells at me: “What the hell did you order this lecture for?” And I say: “What lecture?” — “Don’t play dumb. You ordered this one from the ‘Znanie’ society, what’s it called…” I say: “I didn’t order any lecture.” — “What do you mean you didn’t? The director got a reprimand, the deputy got a reprimand, I got a reprimand, all for hiring a nationalist, and he’s ordering a lecture from the ‘Znanie’ society on ‘Sex in the West.’” As if I had ordered a lecture from the “Znanie” (Knowledge) society on “Sex in the West”! I didn’t order such a lecture because I knew no such thing existed. I myself sometimes gave lectures for the “Znanie” society, though they kept me there on a semi-legal basis. I knew that such a lecture could not exist in the “Znanie” society. It means Bykanova made it up, that he’s such and such, that he’s not just a nationalist, but also ordered such a lecture. And the warrant officer had already forgotten that he had my resignation letter: “Write a resignation letter!” I say: “Why write one? It’s already there. Let me just put a date on it.” I put a date on it. He was so happy. I say that this warrant officer is a decent man. He hired me as a certified specialist, with a diploma with honors. Such a situation.

And I remember one more story. I had forgotten it, but a university classmate, Valentyna Svyrydenko, reminded me of it. She was the class monitor, and I was the deputy monitor. I was thirty-one years old when I was admitted to the university. I was admitted purely by chance.

V.O.: What year was that?

Ya.T.: It was 1971. I enrolled in the Dnipropetrovsk State University, at the philology department. In the correspondence division. I had applied several times. You see, I studied in nine or however many schools. I barely finished school. I got my diploma with incredible difficulty. But I did get a high school diploma and tried several times to get into university—they wouldn’t accept me. I wandered around the Soviet Union: I had no place, they hounded me, hounded me, hounded me. And then Professor Shylovskyi, may he rest in peace, a normal person, helped me somehow. They accepted me on the condition that they wouldn’t let me graduate. That is, I wouldn’t make it to graduation. It was said from the start. I was looked after by Volodymyr Semenovych Bondar, may he rest in peace, also a bruiser, with biceps like this. When you ride in an elevator with him, it feels like a gorilla is with you, about to crush all your bones. I studied well. I passed my exams as an external student and finished early, receiving a “red diploma” with honors in 1976. But how did I get the diploma? I was warned: you will not pass scientific communism. This Volodymyr Bondar told me. I wrote a good thesis. The head of the commission told me to format it as a PhD dissertation. Just format it—it was such a good thesis. One way or another, I had earned a diploma with honors. So, listen to what happened next. When they told me I wouldn’t pass scientific communism, I knew I wouldn’t. You know yourself: they ask you a question you can’t answer. I was a loner. A very wise person once told me: “If you do something, don’t involve anyone else in it. You will be responsible yourself.” And so I lived my whole life as such a loner. But it started to get to me a little when I found out I wouldn’t get my diploma. And I wanted to study, I wanted to have a diploma, and I wanted to do a dissertation. I would have done it. I was talking to the head of the examination board one day, and he looks at his little notebook and says: “If it weren’t for your exam on the 22nd, I would have gone home to Kyiv on the 18th.” The head of the examination board was Kost Petrovych Volynskyi, the son of the famous philologist Petro. I have immense respect for this Kost Petrovych. Because whether he wanted to or not, it so happened that he helped me. How? He said that phrase, and it immediately flashed through my mind: reschedule the exam. He says: “What do you mean, reschedule the exams?” I say: “Just reschedule the exams. I’ll make sure the students are there, and you take care of the instructors.” And he moved the exam from the 22nd to the 8th. There were two days until the exam. In two days, this Svyrydenko Valentyna, who was the monitor, and I traveled around, called all the students from the region, and on the 8th, we held the exam. We started at eight o’clock, and by half-past nine, I had an A in scientific communism.

A day or two later, I get a summons to the military commissariat. That’s how the KGB summoned me—with a summons to the military commissariat. I go to the military commissariat, and there’s a black car, they shove me into it: “Let’s go.” They bring me to Bondar’s office. Bondar slams his fist on the table with all his might: “You’re a scoundrel, Trinchuk!” I say: “I know.” And he says it a second time: “You’ll never work anyway!” I say: “I know that too.” Just two small details like that.

Once, I had a normal job. It was for a year and a half, in 1994-95, I was the director of the Dnipropetrovsk Regional Philharmonic. But they didn’t pay me. Well, they paid very little. About 10 dollars a month. So I left that job.

All of this was the consequence of my conflict with the KGB, which happened when I was 18 years old. I never had a normal job. Secondly, I never had a home. I still live in someone else’s apartment. This is my father-in-law’s apartment.

The problem of the KGB always tormented me. I knew it was evil. I knew they wanted to kill me or destroy me because we were different. But I wouldn’t let them. Do you know when it was hard for me? Sometime in the fall of 1985, when Stus had already died, and later, we already knew about it. The October plenum had already taken place. Gorbachev was in, some kind of perestroika had begun. I had guests. Our people were sitting there. Several people—five families were there, or however many. I propose a toast: “To an independent Ukraine!” The guests scatter.

V.O.: What year was that?

Ya.T.: It was late fall of 1985. It was early, of course.

V.O.: Early, but it seemed like “perestroika” had begun. Gorbachev had been in since the spring.

Ya.T.: The plenum when Gorbachev came to power was in February. I must tell you, that saved me. Because it was planned to destroy me. Taraban—I’ll name him, he works in the KGB—received that assignment. Now he’s a successful businessman. He received the assignment to “localize” me. I don’t know what “localize” means.

V.O.: Well, probably to prevent some evil from spreading, it could be localized. For instance, they would hold workers’ meetings, and the collective would request: “We ask you to shield us from so-and-so.” Translated into Ukrainian, this meant: arrest him. One of the last such meetings was in the Dnipropetrovsk region in Vasylkivka in April 1978: the “working people” asked the authorities to “shield” them from Vitaliy Kalynychenko.

Ya.T.: But Taraban failed the assignment. He later received a reprimand. When they took me to the KGB, one of them shouted: “You let down such a man!” He was supposed to imprison me. As they later told me, I was supposed to get 8 years—for allegedly raping a student. Why wasn’t I imprisoned? I wrote a note promising not to engage in anti-Soviet activities. It was like a magical ritual. I gave them hundreds of such notes. As soon as they summoned me, I would write them such a note that I would not engage in anti-Soviet activities—and this note localized their actions against me. I never wrote any kind of repentance. I only wrote that I would not engage in anti-Soviet activities. One time Taraban said: “Yaroslav Ivanovich, look, we won’t summon you anymore.” This was before they framed me for supposedly raping a student. “We won’t summon you anymore.”

I was my own person, raised in a family in Stari Bohorodchany. Love for my land, for Prykarpattia, for the Carpathians, love for Ukraine, respect for a person—that’s how it was with us. And when they told me back then at the district committee to renounce my father, I understood that this system (I didn’t delve into the system then) demands scoundrels, not decent people. If they don’t want me as a decent person, but want a scoundrel—then that’s it, our paths have diverged. And this continued until recently. A KGB agent used to visit me here, Yevhenii Hrubа. He told me he was studying Ukrainian history, wanted to write a book on Ukrainian history. He kept coming, coming—with some economic questions. This was already in independent Ukraine, 1996. And another man used to visit me here. And they met here, in my room. And that Hruba stole 8,000 dollars from him. KGB agent Yevhenii Hrubа—a scoundrel among scoundrels. He supposedly wanted to write history…

I had such a case. It’s also interesting, it’s described in my book. I’ll show you. I knew one person was informing on me. I just guessed, suspected that he was informing. And for me, the slightest suspicion was enough to break off relations. I broke off relations with many people I used to socialize with. Just from that day on—I never called again. He called me once: “Why don’t you call?” And I ask him: “Vania, lend me some money. A lot.” As soon as you start asking them to lend you money, they freeze up and then don’t call for a long time. And when they call six months later, I ask for twice the amount. So he doesn’t call anymore. About five years later, we meet. This is already ninety-something. He’s terribly happy: “How are you?” I say: “Better than you.” He’s surprised: he’s a nomenklatura figure, and I’m unemployed, and I’m telling him I’m living better than him. He looks at me like that, and I say: “Vania, my conscience is clear.” And his eyes started darting around when I said that to him. But he doesn’t know what information I have. I also don’t know to what extent he gives information about me. It ended with me telling him: “You wrote denunciations against me to the KGB.” And he says: “Well, you see, we have a different worldview.” — “What worldview,” I say, “man? What worldview do you have if you wrote denunciations? We ate and drank together, you came to my house, I treated you, we made toasts—and you wrote a denunciation!” He starts to justify himself. I say: “You know what? For what you wrote—I can forgive you. But for justifying yourself, I will tell (and what can I do?)—I will tell your daughters.” And he had daughters who were already modern. They had already detached themselves from this imperial filth. He falls to his knees—nothing like that had ever happened in my life: “Yaroslav, I beg you—don’t tell my daughters!” I then gently pushed him away and said: “Well, I don’t know—if I’ll tell or not.” And I already knew that I wouldn’t tell. I don’t need his apology. I must say, I never felt such happiness in my life as I did then. I’m walking, there are many people, and something is lifting me up! There isn’t a single person in the world who could have treated me the way I treated him! Not a single one. This is what it means to be yourself.

This is what I’m saying, that they scattered when I made a toast to Ukraine.

V.O.: So they all just left?

Ya.T.: Well, we had already had a drink, and I say: “To an independent Ukraine.” Then everyone: “Oh, I forgot to turn off the iron!” They grab their husbands—and hurry away. And in a few seconds, no one is there—everyone forgot something at home! The glasses were left just as they were poured. If they had slapped me in the face, they wouldn’t have insulted me as much as with that act.

But look at the continuation. They ran away. But they have to justify themselves. And how to justify themselves? Trinchuk is a provocateur. They spread the phrase: “Trinchuk is a provocateur!”

We are standing with some guys from my region near the “Ukraina” cinema. I think it was 1987 or 1988. The year when a positive article about Mazepa was first published in the magazine “Ukraina.” The conversation is about Mazepa. A few of our fellow-countryman intellectuals. We are talking about history. That Mazepa was no traitor, he didn’t betray anyone. Did he betray his Ukraine? He wanted to liberate it. Peter was the traitor, because he didn’t adhere to the principles he should have adhered to. If he had at least adhered to those articles that the unfortunate Yurasik Khmelnychenky signed, those second Pereiaslav Articles. I’m saying that Mazepa is not a traitor. I even gave the analogous example of the Hungarian Rákóczi. The guys scattered, only one remains to tell me this: “Yaroslav, you are not a decent person.” — “Why?” — “Do you realize what position you’ve put me in?” — “What position?” — “I don’t know what to do. I know for a fact that tomorrow they will go and report what you’re saying, and I will be reprimanded for not reporting it.” I say: “Lads, you are scoundrels so refined that there are no greater scoundrels than you.” And I left.

A month later, that article about Mazepa comes out in “Ukraina.” Those guys approach me: “Yaroslav, did you conspire with that author?” — “No,” I say, “lads. We studied history from the same source.” You see, this fear of being yourself, of being a normal person—it’s a very disgusting fear. It’s as repulsive to me as the KGB agents are. One KGB agent said: “I’m doing my job. Do you think it’s normal to do your job?” I say: “You should do your job normally.” He was trying to justify himself. I have no complaints against him. He is on that side, and I am on this side. And he was doing his job normally.

But I have a very big complaint against those who fled when the toast to Ukraine was proposed. Because they are our Ukrainians. This sickly cowardice—it is harmful. But there were also good people with me. This was Mykhailo Fedorovych Kulish—a construction engineer. He wrote a novel, “Empire of Evil,” in five volumes. When I was being hounded, when I was jobless, he would give me his manuscripts for me to type. I would type them for him because he couldn’t type. He paid well, and I lived off this for months. I knew it was good writing, a good novel, a thriller, he built the intrigue very well. A wonderful intrigue, dynamic plot development. He had something that our literature greatly lacks—dramatic conflict. He could build a conflict. And what I liked most—when he talks, it’s like he’s building a crescendo in music. He builds and builds and builds—and then an explosion. He was a wonderful writer. Unfortunately, he died young. Mykhailo Fedorovych Kulish died in 1990. He loved Ukraine very much. He was the only one I could have a proper talk with. He comes over one day and says: “Yaroslav, they are saying such and such about you. And I said: you are lying! And they ran away from me.”

V.O.: And when was that novel written?

Y.T.: In the eighties. Already during Gorbachev’s time. He wrote it over a long period, starting sometime in the seventies. It was an attempt to realize his potential. He was a civil engineer. I used to say that we have three Kulishes in our literature: Panko, Mykola, and Mykhailo Fedorovych Kulish. A very good, decent man. In one of his novels, he describes a fantasy about elections in Western Ukraine. Two candidates: one from the UPA, one Communist. The Communist wins, of course, because they stuffed the ballot boxes. And the other one walks into his office in Kyiv and stands on the threshold to tell him: "You're a scoundrel, not a deputy."

The second one is Ivan Petrovych Mykhlyk, a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature. He had a peculiar way of protesting. He would copy books by hand. He would travel to the Moscow Lenin Library, take out books, and rewrite them. And it was then that I read one of Hrushevsky’s volumes in manuscript form, which he had copied. Also Iwan Ohienko's "Beliefs of the Ancient Ukrainians." He had an entire, huge library that he had copied by hand over his lifetime. I consider this a feat of heroism. Mykhlyk Ivan Petrovych, a teacher. He passed away; he was already old. He was around 70 years old. Not only did he tend a garden to survive, not only did he have a teacher's workload—during the summer holidays, he would go to the library and copy books. This was also a form of resistance, a rejection of that life. But he wasn't aligned with anyone—he just kept to himself and his wife.

In Kazakhstan

V.O.: And how did you end up there?

Y.T.: I wasn't in Kazakhstan of my own free will either. It was 1961–62. I had help getting out of there.

V.O.: What do you mean, not of your own free will? But if you don't want to say, don't say.

Y.T.: Well, here’s what happened. After I got out of prison, I had no job, nowhere to go. I went with some guys to Odesa to look for work. At that time, remember, they sent second-grade flour from Odesa to Cuba. And the Cubans cut open the sacks and showered our crew with that flour: "Why are you giving us black flour?" This was when we had no bread of our own. The sailors in Odesa went on strike then. And we—there were a few of us—when they were bringing in the strikebreakers, organized a picket to support the strikers. They grabbed us, threw us in a car, and onto a train. They said we’d get our documents in Ekibastuz.

V.O.: I see. They essentially deported you.

Y.T.: It was a deportation. There was no trial; nobody told us anything. They gave us our documents in Ekibastuz. That's in Kazakhstan. There are massive coal seams there. That was my university because those who had served 20–25 years were there in permanent exile. And I met those people.

V.O.: Were they insurgents?

Y.T.: Of course. The short story "The Exiles" is in this book, *To Each His Own* (Ternopil, 1998, 276 pp.). It's about life in Ekibastuz. They were noble people. I was amazed at how one could preserve such a caliber of humanity after serving 20–25 years in prison. Solzhenitsyn came later—I learned about all those horrors there. A little of it is described here, in the book. There’s a character, Petro, who served 25 years. He didn't know why. They just took him and locked him up. And the only thing he wanted was to see Ukraine. But they wouldn't let him go to Ukraine because he was in permanent exile.

As a result of this whole KGB mess, I wasn’t able to start a family. I formed a proper family only when I was already 51 years old. The same went for work. I don't want to talk about everything; it’s not worth writing about…

So, I said I would not engage in anti-Soviet activities. They gave me a trial run—hourly work at the university, teaching Ukrainian. After all, I had graduated with honors.

V.O.: And when was this?

Y.T.: They gave it to me in the 1976–77 academic year. And I was singing in the university choir. We went on tour. We were in Chișinău; we were in Lviv. I may have signed that pledge, but I remained myself. I signed it and forgot about it. I say what I believe. I wasn't preparing anyone for an uprising or for the barricades. But I did say: "It’s a disgrace that there are no Ukrainian schools, that they closed the Ukrainian school." In all of Dnipropetrovsk, with over 150 schools, only eight were Ukrainian. Eight. And one of them was somewhere in Pidhorodne, in the backwoods. It had only 200 students. Or a primary school with 20 students—that’s what they considered a Ukrainian school.

Before that, the KGB arranged a job for me at School No. 97. They checked every sentence I gave the students. Here’s an example. I gave them a sentence from Symonenko. From this poem: "Пощезнуть всі перевертні й приблуди..." Remember that?

V.O.: Uh-huh. "І орди завойовників-заброд."

Y.T.: I gave them this sentence. The whole quatrain. They summoned me to a "micro-pedagogical council"—this was made up of the top teachers and the party organizer. And the principal yells, "What kind of sentence is this?" I say, "It's a complex, compound, asyndetic sentence. Do you have any objections to it or a different point of view?" "What are you doing—mocking us?" "Not at all," I say. "I think someone here wants to mock me." Again: "What kind of sentence is this?" I take out the little book: published by the publishing house of the Komsomol of Ukraine. "Do you have any complaints about the publisher?" "No." "Then why do you have complaints about me?" Because, you see, a guilty conscience betrays itself. Everyone understood who this poem was addressed to, they understood perfectly, and we parted in silence. That was one such incident.

And when I was working hourly at the university, I used to make up all sorts of political jokes myself. Thirty of them.

V.O.: Ah, so you're one of those who make up jokes! And here I was, wondering who invents them.

Y.T.: And I would tell one joke to each person, one-on-one. I have a very bad memory—I remember everything. I can remember phone numbers for ten years. So it was very easy for me. I told everyone a joke...

V.O.: And you remembered which one you told to whom?

Y.T.: And I remembered which one I told to whom. A joke that I invented, no one would ever repeat—this was for the purity of the experiment. So, for instance, we are talking about this unfortunate Yaroslav Halan. I say that he’s no writer at all. Well, "The Punishment" is a decent, realistic short story, but *The Mountains are Smoking* is plagiarized; the plot is borrowed. And the fact that he writes all sorts of anti-church, anti-religious nonsense is absolute absurdity. And that the KGB killed him for it. He served them, and they killed him. The way I’m telling you now is how I told it to a whole group of people, who for some reason objected very strongly. They started yelling at me. I went to bed. A few days later, they summoned me. They summoned me for engaging in anti-Soviet activities. I already knew that someone from that group had informed on me. But now I needed to find out who. When they questioned me, I didn’t mention Yaroslav Halan at all. "But you also told a joke," they said. I ask, "What joke?" And he tells me my own joke. I tell him, "Dear Volodymyr Semenovych, wait a minute. You see, I was talking about Yaroslav Halan’s creative method. Classicism, realism, surrealism… But a professor of political economy might not have understood." He looks at me for a long time and doesn't yell anymore. He says, "Have a seat." And he went somewhere. He was gone for a long time. I waited for about two hours. I sat there alone; he didn’t even leave me a newspaper. He comes back. He's not yelling at me about the jokes anymore. He’s complimenting me, saying I'm smart. I say, "I know, I’m not saying I'm a scoundrel. I know I’m smart." I didn't say that Fedir Ivanovych Shcherbatykh was the one who informed. But I told everyone in the choir that I had told that joke to Fedir Ivanovych Shcherbatykh, the professor of political economy. And I told Bondar that the political economy professor doesn’t understand literature and got something mixed up because I was talking about Yaroslav Halan’s creative method. That was the situation. It was sometimes interesting for me to play games with them because they used to torment me.

V.O.: And you, them?

> Y.T.: And I played along a little. They had an absolute lack of a sense of humor. They didn't know what humor was. You could say anything in any way—they took it all seriously.

Then I had a job at a night school. They made a two-shift schedule for me like this: one hour in the morning, say at ten o'clock, and two hours in the evening. Tormenting me slowly like that. Now it seems almost amusing, but back then it was no joke. I don't want to be a judge of anyone; it’s not in my nature. But when I hear that someone was persecuted, expelled from the Party—that's all nonsense. Who asked you to join? Why did you crawl into that party? And then they would get reinstated. What kind of persecution is that? Those are your internal squabbles. I knew with absolute certainty that this was the enemy, and with an enemy, you have to be like an enemy. But I had far less strength than this enemy. I had my wits, though, and I saved myself.

During those six months I was in prison, the main topic of conversation there came down to suicide. And there were all sorts of attempts—one guy threw himself on a high-voltage wire... This suicidal theme was popular.

V.O.: You’re telling the truth. In prison, everyone thinks about suicide.

Y.T.: Yes. By and large, many people are certainly struggling now because people are facing a crisis of perspective. I am convinced that people in Ukraine have never lived as they do now in a thousand years of history. Many now have a little less to eat than before. But there were also times when there was nothing to eat. But now people have a crisis of perspective. I know this from my own experience. I had a goal: to outmaneuver them, to survive, to show intelligence, to show willpower in order to overcome, not to succumb, so they wouldn’t bend or break me. And they didn't break me. I survived intact.

Already during Perestroika, they lambasted me for being the only one at school who hadn't "reconstructed" himself. A special pedagogical council was held on one single issue—that Trinchuk had not reconstructed. Everyone reported on how they had reconstructed; there were 100 teachers, men and women, sitting there. One teacher was quite beautiful. She was the party organizer. Sometimes I might give her a little pinch. A person's a person; I flirted with her. And she seemed to be kind to me. And she wanted me to reconstruct. The single item on the agenda: that Trinchuk has not reconstructed. Everyone talked about how they had reconstructed and how nice it would be if Trinchuk also reconstructed. I stood up and said that I wasn't going to reconstruct myself: I was normal before, and I will be normal after. And what do you think? Half the school became my enemies; they wouldn’t talk to me. That's a simple example.

We live in a very difficult period. Not difficult because of the economic situation or the lack of money. Of course, poverty is a terrible thing because poverty begets shame, shame begets uncertainty, uncertainty begets weakness, weakness begets anger and hatred, and that leads to evil deeds. But a person needs to be true to himself. A person must be responsible for himself, but it would be so much easier for him if someone else were responsible for him. And he would delegate a great deal of his "self" to this "someone." Including the feeling of freedom.

V.O.: Even our president would be glad if Putin or Kwaśniewski were responsible for him.

Y.T.: Yes, he would delegate the entire independence of Ukraine to them. And our prime minister says that freedom is not a very sweet dish. Freedom imposes responsibility. There is no freedom without responsibility. And people do not want to be responsible. They would prefer someone else to be. These are the difficulties. And to be oneself is a huge luxury. One must thank God for giving life, for showing us the world, and for giving us the opportunity to be ourselves. I went through this school—the school of being myself—when I was just a little boy, when I learned that they were killing us because they wanted to take our piece of bread, our piece of land, our home. They took everything from us. We had a barn—they took that too. We were never able to build a house. And they took the barn. Not Muscovites, not Jews—our own fellow countrymen took the barn. They could have chosen not to take it. If those men who dismantled our barn had even a little bit of responsibility, they could have left the barn for the widow, to let her make a house out of it.

You look now at these political processes, at our political small fry... Take Yavorivsky. He came here to hold a regional conference of the Democratic Party. I was invited as the editor of the journal "Monastyrskyi Ostriv" (Monastery Island). I gave Yavorivsky three issues—the first, second, and third. In hopes that Yavorivsky would support it—he’s a deputy, he has connections, maybe he has ties to Pavlo, and Pavlo has plenty of money. It would have been enough to say, "Pavlo Ivanovych, take a look." Pavlo Ivanovych Lazarenko would have given money for the journal, and it would have survived. But Yavorivsky, when I gave him the journal, got angry and said that we'll get to the point where every street is publishing its own journals. Yavorivsky is not a talented writer. *Kortelisy* is not to his credit. It's our misfortune. He took advantage of documents. But, as Vasyl Stus said, "the cult of the talentless Yavorivskys, their time, their hour." Talented authors either remain silent, like Roman Andriiashyk, or they get busy with who knows what.

Let’s return to the *Shistdesiatnyky* [the Sixtiers]. There was the "Khrushchev Thaw," a loosening of restrictions, and talents emerged. But talent itself is a very fragile creature. Someone has to support talent; otherwise, it will wither and fade. It is to the great credit of our Maksym Rylsky that he supported the Sixtiers. He supported all of them! For one, he helped publish a collection; for another, he secured an apartment. I’m rereading his 18th volume now, his correspondence. I get immense pleasure from it because I see what a noble person he was. But the Sixtiers locked themselves in their own shells, in their egoism. Drach, Yavorivsky, others—they supported no one. They could barely support themselves. But the task should have been set: the integration of Ukrainian culture into society. Since you were supported, since Rylsky supported you—then you should support someone too. The same Andriiashyk, and not wait twenty years to publish his novel *Storonets*—a book about Yuriy Fedkovych. (Andriiashyk R. V. Storonets: A Novel // Vitchyzna. – 1989. – No. 9. – P. 18 – 67; No. 10. – P. 100 – 158; as a separate book: – K.: Ukr. pysmennyk, 1992. – 175 pp. – V.O.). A good book, it received an award. But as a writer, he never realized his full potential. In his time, he was not a subject of culture; he was rejected by society.

So, the Sixtiers, Drach—he was already a figure to be reckoned with—they should have set the task of integrating Ukrainian culture into Ukrainian society. And this task can be set now, but our guys don't understand it. So I want to give them a hint: boys, you need to organize a passionary burst of intellect and honor for the Ukrainian nation. The intellect should be sharp as a razor, and this intellect must be integrated into society. To create not a society of slaves and slave-drivers, but a society of free individuals. And only culture can do that. But right now, we have a pseudo-culture. They’ve imposed a colonizing American-Russian pseudo-culture on us, and we just chew on it. And our own culture is in the backwaters, on the margins. People who could have done something—they’ve been pushed aside, cast out. Only the loudmouths remain. Well, that's enough for today.

V.O.: On the evening of April 3rd, we continue our conversation with Mr. Yaroslav Trinchuk.

Y.T.: My phone conversations and my relationships with people were monitored, but I didn’t know to what extent. For example, a friend and I were planning to go on a bicycle trip to Western Ukraine. We had already arranged it over the phone. We also went down to the Dnipro River for a little swim. And there, a fellow comes up to us, a sturdy, good-looking man. We got to talking. He struck up a conversation. We told him we wanted to bike to the Carpathian Mountains. He said, "Take me with you." Well, if a man asks—we didn't suspect a thing. And so we went. Wherever we stopped—I figured this out later—he would start provocative conversations about the constitution. The constitution was being adopted just then. I said, "It’s a good constitution. The only thing that needs to be thrown out is the sixth article." That was about the leading and guiding role of the Communist Party.

V.O.: This constitution was adopted on October 5, 1977—so you were talking about the draft?

Y.T.: It was about the draft. And there was a lot more. I figured out later that he was a KGB agent. But it so happened that in the Carpathians we were invited to a wedding. He behaved disgustingly. He disrespected the guests, got very drunk...

V.O.: Like a pig?

Y.T.: Like a pig. I was so embarrassed for him in front of those people—terribly so. It offended me. To be honest, I still didn’t know who I was dealing with. "Why did you get drunk as a pig?" I said to him. "That's it. Get lost, I don't want to see you." We ride on. Then he started yelling at me: "You’ll do what I tell you!" And then I understood immediately. I said, "No, buddy, that’s it. From now on, you ride by yourself." We left him there. I don’t know how he got back from the Carpathians. Well, that was his problem. But about a month later, I was accused of opposing the constitution. Well, I already knew he was the one who informed on me. I’m telling you, at every step, I was as if under guard.

V.O.: Under a microscope.

Y.T.: As if under a microscope. Very primitive provocations. Take the surveillance. I already knew it was just to get on my nerves. I walk—some guy is standing in front of me. I walk back—that same guy is standing there. I go home, enter the building—that same guy is in front of me again. One time, I grabbed him firmly by the collar. And I said, "If I see you one more time—I'll break your neck." I shook him like that. He disappeared. And later, I run into him. At some conference, I see him. I approach—and he runs away. After I saw him at the conference, he wasn't there anymore. It was that kind of primitive stuff—but just to rattle a man's nerves. It was easier for me than for those who were kicked out of the Party, then begged to be let back in and were reinstated. Why? Because I had clarity. I understood what a vile ideology it was and what vile people were implementing it. If the colors blue and yellow coincided somewhere, it was already a terrible problem. And the colors just happened to coincide by chance…

V.O.: It was hard for dissidents—apostates from communism. But it’s a different matter when a person had a completely different ideology in their head.

Y.T.: Yes, it was easier for me. Those who begged, "Take me back into the Party"—I sympathized with them on a human level. But I haven't made it as a writer to this day. Although I know I have worthwhile works. And it's not just me who knows—people I’ve talked with know it too.

In the Soviet Union, a writer performed the function of an ideological police force. The Writers' Union performed the function of an ideological gendarmerie. It was not about creativity. It was enough to write a few denunciations—and you were already a member of the Writers' Union. Well, and maybe slap together some quatrain about collective farmers. No one asked, "Man, what are you even writing?" Ninety percent of them were like that. And if someone wrote normally—well, you know their fate. I understood that. So I wrote for the desk drawer. They are profound short stories—that’s what experts acknowledge. Take Professor Myslyvets—she’s a high-level specialist. She knows the subject. She knows what a dramatic conflict is and how it’s constructed. She knew the value of prose. But when Oles Honchar left the Party, my God, how she screamed, "Traitor! Traitor!"

V.O.: She screamed that?

Y.T.: Yes. I can't reproach this person for anything. This person had some kind of stamp in her head, and she tried to keep it clean. She didn't know what communism was, what communist ideology was. She understood that one must be decent. And she believed that if she was a communist, she was decent. This is what propaganda did to people. For instance, they slipped her my novel *To Each His Own*. She read it and said, "Very dense prose"—that was the highest praise from her—"but terribly hostile to us." Well, I understand her; I have no claims against her.

There was this one incident. A banker didn’t want to give money to some artists, and the artists made a fool of him: someone painted some abstract nonsense with their left or right foot. And someone whispered in this banker's ear that it was a work of genius. So he bought it for $1000. Not much, true, but they laughed at him afterwards.

There's no literary criticism; culture and literature are not integrated into society—culture is for itself, and society is on its own. And this is the fault of our Sixtiers. They closed themselves off. It's a peacock psychology—spread your tail and say, "Look at me." Of course, there are good writers among them. But how many people are still on the margins, how many creative people in music, in painting, in writing. To mobilize such a force and compel society to accept these values… They accepted a sewage-pipe culture, while real culture is somewhere off to the side. It's as if it exists—and as if it doesn't. This is also the fault of modern politicians. Take any of the modern politicians—I don't want to name names—take anyone out of the Verkhovna Rada—he doesn't understand what culture is, what literature is.

I ran for the Verkhovna Rada in the 100th district. A candidate is speaking—I don’t want to name him. He used to be a Ukrainian language teacher. Someone from the audience asks an innocent little question: "Why don't you recite something from Shevchenko by heart?" And he panicked. It turns out he doesn’t know any Shevchenko. The audience prompts him: "The mighty Dnipro roars and groans." The hall is chanting it. I'm dying—and he can't continue! This is the level of our political establishment. And they want to go to Europe! Look what France is doing there. We know all the French artists—whether we want to or not. Because France imposed its concept of art and culture on the world. It published its artists in million-copy runs, published albums and books in different languages.

Who among our political class understands that we need to do the same? Not a single one of them knows that an album of Zaretsky's work needs to be published. Alla Horska is published here illegally or at the samvydav level. The state doesn't understand, the political class doesn't understand that one can only speak of a European choice in the language of culture. Only culture, not how much money he stole and where he transferred it. Europe will not accept the uncultured. I try to talk about this. By the way, the KGB understood this better than our current politicians. They had their clichés, but you could even enter into discussions with them about and around those clichés. Although they couldn't have their own opinions.

You understand, Mr. Vasyl, that with the collapse of the USSR, two strong structures remained—the Moscow Orthodox Church and the KGB. They exist in parallel; they act brazenly, strongly, competently; they develop concepts, theories, ideas and try to implement them. And we—we don't know what to do; we quarrel and divide, quarrel and divide. And our nation is in no way inferior to any other nation. Let's say, in the West, there is a criterion of wage level. If you earn a lot, you are very smart. Ukrainians in America were poor, but after the war, they caught up with the Anglo-Saxons and the Germans. We could have been better at home, too, but the blame lies entirely with the political class that emerged from the depths of the KGB. Kuchma is a product of the KGB, all these Vitrenkos, Symonenkos, all these leftists, Moroz—they are also products of the KGB. To a large extent, the "right wing," the Rukh movement, is also a product of the KGB. People like Yaroshynskyi (Bohdan Yaroshynskyi – head of the URP in 1995–98, People's Deputy 1994–98. – V.O.) were sent there on a mission. I would bet my head that they "implanted" him as an activated element to bring about its collapse, which he did, and successfully at that, because they have some moves thought out in advance. We need to do this too. Tell me, does even one party have any kind of analytical center?

V.O.: We in the URP only talked about it but never created one.

Y.T.: What is an analytical center? It must have intelligence, like Razumkov’s. We could now pursue a policy of friendship with Russia, but not make concessions. That it should be friendly to Ukraine because it is also beneficial for Russia. But this general culture is missing, political culture is missing. Therefore, our main task is the integration of our own culture and world culture into society. And you don't have to ask anyone whether they want it or not, just as you don't ask if a child wants to go to school or not—he goes to first grade and starts learning the alphabet. There must be a book intervention. The Russians have captured the Ukrainian book market. But it's not the Russians who are to blame—it's our incompetent deputies, these blockheads, like Yavorivsky, who said it's a normal law. It is not a normal law that taxes books. To print a book, I have to pay VAT—that’s schizophrenia! What VAT can come from a book I’ve just written? Just take the tax from the profit, if there is any. Then we could flood the Russian market with Ukrainian books, and not just Ukrainian, but world literature—publish beautiful albums in the Ukrainian language. Why is it that when, say, some Russian official comes, he is not able, does not want, and does not know how to say a single phrase in Ukrainian? But when the Queen of Great Britain came to Georgia, she said a few words in Georgian. If Putin came and said, "Good day, dear Ukrainians." Would his tongue have withered from that? No!

V.O.: The Pope says it.

Y.T.: Yes, the Pope speaks sixty languages. Furthermore. If he had addressed his own people and said: "Guys! We are friends, learn the Ukrainian language!" Would anything have suffered from this? The issue today isn't about monolingualism—the issue is for people to know many languages, but the state language must be one. A state cannot exist with such a flimsy language policy. This will lead to flimsy thinking in people's heads because there is no clarity in the state's cultural policy.

V.O.: You still haven't read my article "Between Us Philologists, So to Speak"?

Y.T.: I read it back when it was published. I follow you; I read what you wrote about Marchuk.

V.O.: And did you notice what Kuchma said today? He said that Ukraine cannot live without Russia, but Russia can live without Ukraine. I've heard other authorities on the matter. For example, Bismarck, the first German chancellor, said clearly: "The amputation of Ukraine would be fatal for Russia." And there was another man, authoritative in the world in his own way, named Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. He said: "To lose Ukraine is to lose one's head." This means that the Russian empire is impossible without Ukraine. It can be a large territory like Canada, and even Canada is more or less stable, while Russia is constantly under the threat of disintegration. And Kuchma has never even heard of this!

Y.T.: No, he knows this, but he talks about the integration of Ukraine into Russia.

I am talking about culture. You come here—say a few words in Ukrainian. Publish a Ukrainian book in Russia, open a Ukrainian theater, as we have done here. So there is parity. It is enough for Ukrainians now to realize that they are Ukrainians—and nothing more.

I will draw a parallel now: for Ukrainian identity to survive, it had to start speaking Russian. The Russian language, to some extent, saved us as an ethnic group. Just as the Greek Catholic Church saved the Ukrainian language and culture in the territory where Poland had influence. If the Uniate, Greek Catholic Church had not been established, the slaughter would have been terrible and would have lasted who knows how long and ended who knows how.

So here we are, carrying this Ukrainianness on our backs like a heavy stone. I've lived for 61 years, and I've been holding this Ukrainianness like a huge stone on my back. If I had thrown off this stone in my time, I would have soared. I had the intellect, I had the will—but I held on to it and still do. We have a production center on Channel 34. They told me there: "Yaroslav, your own people will never support you; if you want, we'll support you." But I would have had to renounce some of my concepts. And I am unyielding because, after all, I don't earn my bread, I correct thoughts. A thought is a very significant and heavy life experience, an intellectual experience, a cultural experience. I have absorbed world culture, literature, philosophy, and I can no longer deviate from this path, especially since I haven't done so until now.

V.O.: We continue our conversation with Mr. Yaroslav Trinchuk on the evening of April 4, 2001.

Y.T.: They, the KGB agents, are absolutely devoid of a sense of humor. They didn’t know what humor was. They couldn’t laugh. They took everything seriously. But, despite this, their approach to people was very peculiar. Sometimes they wanted to be chummy, wanted to inspire trust, as if to say, we understand, you’re a smart man. But in general, they had no regard for a person. Sometimes they didn’t even seem to consider that a human being was sitting next to them. Take Lieutenant Colonel Volodyn Pavlo. They told me he now receives a general's pension. Let him, that's his business. He didn't do me much harm. He even posed as an intellectual. He had, after all, read a few things, knew something about Ukrainian literature. You could even talk to him as you would with a human being. But sometimes he acted as if some stump was sitting next to him. He was talking on the phone with someone about hunting. He was saying such nasty things that you can’t say in front of strangers. In other words, he didn't consider me a person at all. Just a piece of furniture sitting there. He tells a story about how a district party secretary was removed from his job. They went bear hunting in a protected area. He wounded a bear, and the bear came after him, so he ran—and climbed a tree. But the bear climbed a little way up and fell, strengthless, because it was wounded. They tell the secretary to come down—but he doesn't want to. For a very long time he couldn't get down, he didn’t want to. I don't want to and that's that. The colonel laughs: they didn't fire the secretary for shooting the bear, but for soiling his pants.

He told another story. Somewhere in the Lviv region, there was a district party secretary who really loved women. I don’t know if that was a compliment or a condemnation for them. A young surgeon came to this district center with a beautiful wife. And this secretary started chasing after her. He himself was attractive, and well, he seduced the woman. But the surgeon was not a malicious person. He put sleeping pills in the cognac and went to work. He comes home at night, and they're already asleep. So he performed an operation on him—a full castration. He set an alarm clock for him for twelve o'clock. The guy gets up. It's late, he needs to be at some meeting, he gets scared, pulls on whatever he can find. Something hurts a lot, but he doesn't know what. And when he comes to his senses—it's a catastrophe, the man is ruined. He went to the hospital, and the doctor there looks and says, "Eh, man, you've been castrated, you're a eunuch, everything here's been cut out!" He lost consciousness and never returned to work. His wife left him. And they did put the surgeon in prison for four years, but they let him out after a few months. I heard many such stories there.

V.O.: Such is their world.

Y.T.: Their world is like that. They told these stories as if they didn't consider me a person.

V.O.: April 4, 2001, in Sicheslav, Mr. Yaroslav Trinchuk continues the conversation.

Y.T.: So, culture—this must be the dominant principle in politics. For every politician, from the head of a village council to the president, it has to be culture. I'm terribly impressed by the Czech Republic, by Václav Havel. His articles occasionally appear in the newspaper "Den" or "Dzerkalo Tyzhnia"—now that's a smart man, that's the kind who should lead! I think: My God, if only one of our own, from the Presidential Administration or the Verkhovna Rada, would write something intelligent. They’re all so sluggish, lazy, ailing. But I'll tell you this, Mr. Vasyl: that’s the kind of people the government needs, because the government can manipulate them however it wants. They have no opinion of their own, they have no vision of their own—the government says so, and so they work.

Here we say: "independent Ukraine." Independent, of course, that goes without saying, there can be no more questions about it. The fact that there is some economic dependence on Russia, on the West—that's not so terrible. Many states in the world are economically interconnected. The Germans, the French also have something in common; in the world, this is accepted, and among intelligent people, it is resolved intelligently. But since the government has not accepted Ukrainian culture (it hasn’t accepted any culture at all, let alone Ukrainian), it is a foreign body in Ukraine. It is alien, it lives as if among strangers, it hates this nation, and although it lives on this land, it would like to ruin this land. It instinctively feels that the element of culture could make normal people out of them. In 1918, poets and musicians wrote songs for the Sich Riflemen. They were the intellectual elite, true aristocrats of the spirit, who knew that this was the only way to establish Ukrainian rule. And now I don't see an intelligent politician on television. Television is now the main means of communication with the government. And for ten years I haven’t heard the music of Yevhen Stankovych on television, I haven’t heard the Ukrainian folk choir for ten years, nor the banduryst kapelle. Instead, there's this Verka Serduchka—I can't watch it, the whole family can't, we turn it off… "Co zanadto, to nie na zdrowie" [Too much of a good thing is good for nothing]. That’s the level. I have nothing against Danylko as a talented actor.

V.O.: But this phenomenon is completely outside of culture.

Y.T.: As an actor he is talented, but what the directors make of him…

V.O.: We continue on April 5th.

Y.T.: One time I insulted a military man. He was a colonel, the military instructor at the school. He was a bit paunchy, a bit arrogant. I didn’t know he was a colonel. He was young, had fought in the war. I said that I don't like those who fought. I said, you fought—it's good that you won a victory. But you won a victory over widows. You fought and took everything for yourselves, while the widows were left hungry. Those who died are ignored. He was terribly offended. Why was I not entirely proper with him? Because he didn’t fight—he was an NKVD man. He came out for a holiday celebration—his chest was more decorated with medals than Brezhnev's. I later found out he was an NKVD man.

We had a neighbor like that, Petro Pysarchyn. He was deaf, poor. He was walking in the woods, and these NKVD guys were standing there, and one says, "Let's take a potshot." I myself heard the shot, and a neighbor saw it with his own eyes… One guy says to the other, "Let's take a potshot." And that deaf man was far away, near the forest. He took careful aim, fired into his back—the man never even saw where death came from.

V.O.: What is that, "let's take a potshot"?

Y.T.: Well, with a carbine. He just killed a man for nothing like that. This was 1945 or 1946. And this woman, they call her Petrykha Pysarchyna, is still alive. Her husband was killed, and they always told her she was the wife of a killed Banderite. He wasn’t a Banderite because he was deaf. An NKVD man killed him. And an NKVD man like that now receives a general's pension. And the widows? Here we have ten years of independent Ukraine. Kuchma speaks, Plyushch speaks, Tkachenko speaks—and not a single word about the poor, unfortunate widow. I still stand by my opinion that the glory and the victory have been unjustly divided. The benefits are enjoyed by those who have no relation to this victory. He was in the NKVD, he was shooting people in the back. And those who died—they were written off, they don't exist. And the widows suffered, their children didn't get an education, some children became alcoholics, some went down the wrong path, but they did so not because they were bad, but because the state didn't care one bit about them. And how many of these old grannies are in your Kyiv's underpasses right now? These are those very widows; ask any of them—her husband perished. And not a word—neither the president nor anyone else will say a word about this widow. Such an unjust society—it has no future. Because it's immoral—that's roughly what I said then. True, they didn't fire me from my job that time.

Based on the events we have observed recently, based on the tragic history of humanity, I want to express one thought. We do not understand the nature of power. Take all these hundred parties—and in each of their platforms, it is power for power's sake, to command people, to take from people what they earn, and to leave them a crumb of bread. Now they take everything. But power should exist to manage information flows, nothing more. A person should have a contract with the director, with the manager: I'll give you this, you give me that—and that’s it, and no one has any power over me.

They have imposed a sewage-pipe culture on us—we must impose a real culture to change people, to forever put a stop to the plundering of people, so that a person knows: this is theirs, this they have earned, and no one can ever take it away from them.

To return to that KGB agent I offended. One hundred years of Valerian Pidmohylny, a committee is being formed. Leonid Cherevatenko, whom I greatly respected, proposes the editor of the newspaper "Zorya," Leonid Hamolskyi, for the anniversary committee. Hamolskyi spent his entire life denouncing Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism; he traveled to political camps—the KGB sent him there, he wrote...

V.O.: It seems he wrote against Ivan Sokulsky, and that's what he's known for.

Y.T.: Yes. Hamnolskyi is a man on whom morality has never had a hold. And Leonid Cherevatenko proposes him for the committee. Money is being allocated to honor Pidmohylny’s centenary… I don’t understand Leonid Cherevatenko.

Let's return to where we began—the problem of sacrifice. I cannot comprehend a person who was allowed to defend a dissertation and thinks it is their merit to Ukraine. When we speak of sacrifice, we carry our stone in silence. When I speak of sacrifice—I know I wouldn't have survived twenty years in prison; I would have done something to put an end to it. But my family, my kin, made a huge sacrifice; many people perished. Three brothers died—my father and his two brothers, my mother's brother, my mother's sister died, my mother's sister-in-law's sister died, my mother's sister's husband died in a camp—they took him, and he died three years later. It would be a huge list of several dozen people who died young. A great sacrifice. But if you bear this sacrifice, you don't boast to anyone that you sacrificed your years. No one forced you; you knew what you were getting into; you knew it couldn't be avoided—such was your fate.

I also cannot understand a person whose father was one of the "thirty-thousanders," and who boasts that their father was a thirty-thousander. And the thirty-thousanders were the ones who organized the Holodomor. When it's convenient, he says his father was a thirty-thousander, and when it's not, he keeps quiet about his father and then says he was persecuted. I am not a judge, nor a prosecutor, nor a lawyer; I am self-contained. I understand that sacrifice is a purification, and, undoubtedly, these huge sacrifices made by the nation will not be in vain. The nation will be reborn and will have its say because its potential is great. We have a broken cumulative process of culture. We had nothing left after the Holodomor, nothing left after the war—but after that, there was a flash of culture. We have world-class music—Stankovych, Hrabovsky, Karabec; literature, world-class poetry—but it is unread, it is not integrated into society. But no matter what tricks these Medvedchuks and Surkises pull, it won’t help them. Well, they will steal money because that is their profession. But they cannot and will not create.