An Interview with Roman Stepanovych KALAPACH

V. V. Ovsienko: February 2, 2000, the town of Stebnyk. Roman Kalapach is speaking. The recording is being made by Vasyl Ovsienko.

R. S. Kalapach: I, Roman Kalapach, was born on November 12, 1954, in the town of Stebnyk. My mother was a native of Stebnyk; her maiden name was Emilia Ihnativna Trach. My father, Stepan Stepanovych Kalapach, was born in the Zhydachivshchyna region. My mother's brothers and sisters were connected to the national liberation movement in Western Ukraine. My mother's own brother was killed in 1943 while carrying out an assignment for the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. My mother's sisters were also participants in the national liberation movement.

V. O.: And you should state their names.

R. K.: The eldest sister was Maria. After her release from the camp, she lived in the Rivnenshchyna region, and that is where she died. What I'm getting at is that from our very childhood, the ideas of Ukrainian nationalism were instilled in me and my brothers by our maternal uncles and aunts. From a young age, I was familiar with the idea of Ukrainian nationalism. Here in Stebnyk, there are people whom I won’t name now—they are alive and well and can confirm that when I was just 12, we were already beginning our struggle, Mr. Vasyl. Not when I was 17, but at 12 years old. As young boys, we would put up anti-Soviet leaflets, and we were never caught. When we were finishing school, in the tenth grade, our class had an active, nationally conscious group of about ten people who shared our views. By that time, we already knew who Vasyl Symonenko and others were. At the trial, they asked me: “How do you know this? Who told you? Where did you learn about the yellow-and-blue flag?” Of course, I couldn't tell them openly. I said that we read about it in Soviet literature. And I provided facts: Volodymyr Sosiura had a poem that mentioned yellow-and-blue banners. That’s how I tried to mislead the KGB agents, while they kept insisting that if we gave up our elders, we would be pardoned.

V. O.: They thought some older person was directing you.

R. K.: It wasn't just that they thought... As we later found out, in 1972, more than 700 participants of the national liberation movement were living in Stebnyk, people who had been through the Mordovian, Perm, and Vorkuta camps.

V. O.: More than 700?

R. K.: Yes. So they summoned all of them to the security services, interrogated every one of them. First and foremost, they attributed the act to them. And what was the act? At the trial, the prosecutor asked me: “Why did you do it?” I stood up and answered. Even though my lawyer had told me beforehand in the Lviv prison: “If you shave off that Shevchenko-style mustache of yours”—he was that blunt about it—“maybe they’ll reduce your sentence.” I said: “That’s not going to happen.” So when the prosecutor asked why we did it, I replied: “To show people that there are still those who are fighting for an independent Ukraine.” This is officially recorded in my case file.

V. O.: And how exactly did this act come about? You mentioned that at 12 you were already putting up leaflets—what kind of leaflets were they, who made them, where did you get them, and what was written on them?

R. K.: I had a friend whose father was a very well-read man. He was a great lover of books and had old books in his home library—by Ivan Franko, Shevchenko, and many others. So, as young boys, we would spend time in his room, reading and discovering things.

V. O.: Could you name him?

R. K.: No.

V. O.: Then you don't have to.

R. K.: No, I can't. I'm not naming names for now; I don't yet believe in a complete victory. People like that were destroyed...

V. O.: Well, this isn't an interrogation, it's a conversation. I'm not insisting.

R. K.: Even if it's not an interrogation, it could become a pretext. I was arrested in August 1972 at Lviv State University. I was applying to the law faculty. They took me from my second exam. They held me for three days and then released me. We were free until February 9, 1973. What were they doing all that time? They were watching us, hoping to catch someone older; that was their goal. It’s written in my file: “How could you, a future law student, have done such a thing? How could you apply after such an act?” But that’s how one had to act. I wasn’t the only one; conscious people even joined the Party to build Ukraine, acting underground, and they were right to do so. If I hadn't done what I did, Mr. Vasyl, I was so ideologically committed that I would have ended up in the same institute or university anyway. I would have been admitted, 100 percent. My place at Lviv University was secured; my father had powerful connections there. I passed the first exam for the law faculty; I would have passed the second, third, and fourth. They just didn't let me take the second one; they called me to the admissions office. Three black “Volgas” were parked outside Lviv State University. The hallways were full of students. They called me out of the exam to the rector's office, and there they said this and that, clicked the handcuffs on behind my back, and took me away.

V. O.: What year was this?

R. K.: In August 1972, I was arrested for the first time, for three days. I was held in the “Narodnyi” hotel because there was no evidence yet. They could hold you for up to three days. But what I'm getting at is this: if not for raising the blue-and-yellow flag in Stebnyk, it would have been a different act—the creation of an underground organization that would have fought for the freedom and independence of Ukraine. It's my fate that I revealed myself so early. If it had happened later, when I was an adult... The act was committed as a minor—I was arrested in August, and I turned 18 in the fall. The lawyer hinted at this, that, and the other... My father told me that under Polish rule, activists who hung red banners were jailed for two days before May Day, held, and then released on the second or third of May, and that was it. But my predecessors, Danylyshyn and Bilas, natives of Truskavets, were shot by that government for singing the anthem—and the Ukrainian anthem and raising the blue-and-yellow flag are almost the same thing. So the Soviet authorities treated my act very leniently. But I was received very well in the camp.

V. O.: But wait, I'd like you to tell me about the event itself. You must have prepared, someone did something, you talked about something—all of that is what's interesting.

R. K.: You have the verdict in your hand...

V. O.: So what if I have the verdict? The verdict is one thing. Please, tell your story.

R. K.: The verdict says who did what...

V. O.: But you tell it; it's no longer a secret.

R. K.: It's no secret at all, yes. What exactly interests you?

V. O.: About how you came to the idea of raising the flag and how you did it.

R. K.: I will repeat to you now what I said at the trial about why we raised the blue-and-yellow flag. It was to show the population...

V. O.: Not why, but how.

R. K.: I'll tell you now. There was preparation. I personally went to the city of Lviv—to Lviv, to buy the blue and yellow material, not in Drohobych or Stebnyk. Because they might have noticed here... Others had other assignments, things they had to acquire. In the attic of a neighbor, not far from me, with Lyubomyr and that neighbor's boy and one other—there were four of us. The other two were let go as witnesses because Lyubomyr and I took all the blame on ourselves. The two of us, Lyubomyr and I, were convicted. I was sentenced to a strict-regime camp in the Perm region, and Lyubomyr was sentenced to a general-regime camp in the Mordovian region. (But he actually served his time in the strict-regime camp ZhX-385-19. – V.O.) Lyubomyr was arrested earlier; they didn't even let him finish school because he must have drawn attention to himself somehow, or maybe one of the other two boys did. The Chekists were here day in and day out; it was done in the spring, and they snooped around all summer. Well, that was their job; I won't go into how they found us. I was the last to be arrested, in Lviv, in August.

V. O.: On what date?

R. K.: In early August. I can't tell you the exact date. After passing the first exam, I came for the second one. The first exam was an essay in Ukrainian language; it was written, and I was admitted to the second exam. The second exam was supposed to be oral. We were in a large hall. They called me: so-and-so, please come to the admissions committee. Suspecting nothing, I went there. When I was walking to the admissions committee, I think with some professor who had called me, the university corridors were already empty. But when I was leaving, the corridors were filled with students and university lecturers. Someone from the admissions office must have already announced that they had come. The men who came introduced themselves, said who they were and who they were there for. One walked in front, two behind me, my hands behind my back.

V. O.: Were they in civilian clothes?

R. K.: In civilian clothes, and a black “Volga.” They put me in the car and took me to 1 Myru Street, in the city of Lviv.

V. O.: What's there, the KGB?

R. K.: The KGB.

V. O.: Tell me about the investigation, how it was conducted. Do you remember the investigators' names?

R. K.: Later there was some Ivanov, I think, a very Russian surname. How did they conduct it? They held me until evening. One person came, then another, then a third, all saying: “Confess, you're the last one, there's nowhere for you to go, we already know everything.” As for using any physical methods—no, there was none of that. They gave me something to eat in the afternoon. And toward evening, one of the security service officers couldn't take it anymore; he slightly uncovered a protocol that was signed by one of the boys I told you about. He confessed that I was so-and-so, so-and-so... The investigator says, what's there for you to do, you're like the locomotive on a train anyway, you see, everyone is testifying against you, everyone, everyone... I was there for three more days in the “Narodnyi” hotel. They assigned one of their own men to me; he was with me for three days. They took me in every day to tell them everything. There was nowhere to turn; that's how it turned out. Indeed, the other boys were arrested earlier...

V. O.: The investigation didn't last long?

R. K.: They released me after three days because there was no evidence or something. They released me back here, to Stebnyk, under a signed pledge not to leave. And then the investigation continued. I was supposed to start working. I got a job at a construction office, doing construction work—handing up bricks, removing formwork, I was an apprentice—what else could I do at that time. I worked like that all fall until winter, until I was arrested on February 9, 1973. They must have had the evidence by then. Or maybe they got tired of watching us. That's what I understood, because when they summoned me to Drohobych, they would say: “Tell us who, tell us who told you, point your finger at an older person—and you'll be free.” That was the interesting part.

V. O.: That's why they released you. To watch you.

R. K.: That's probably why they let me go: to see who I would go to, whose house I would enter... That's the story. Although I want to tell you, you have to give credit to those officers too... One of the security service officers told me one-on-one in his office: “We all love Ukraine, boys, but you went about it the wrong way. You took the wrong path. You didn't express it correctly...” There were people like that too. Even then, in those agencies, there were conscious people who saw all the injustice.

V. O.: So, you were finally arrested on February 9, 1973. And the investigation continued after that?

R. K.: That was the preparation for the trial. I spent another two months in the Lviv prison. When they arrested me, they took me alone from here in a “PAZ” bus in the morning to Lviv. There was some kind of guard. Straight to the Lviv prison, into a cell. The investigation was still ongoing there. There were more interrogations, some things were being clarified, they interrogated me again. I remember meeting someone there; he was being led somewhere. Only later did I find out it was Zoryan Popadiuk. He was being led down from above, probably from an interrogation room, down those stairs, and I was going up. When we met, they turned him to face the wall so I couldn't see him. They led me past him. And then the escorts themselves told me that was my comrade-in-arms, Zoryan Popadiuk. I saw him later; we met. There was probably no one else in the Lviv prison at that time. I think Chornovil had been there before that.

V. O.: Yes. Because those arrested in January 1972 had already had their trials and been transported out. When did your trial take place, and how long did it last?

R. K.: I don't remember. The trial took place about two months later. It lasted two days. A closed trial.

V. O.: Meaning there was no one in the courtroom?

R. K.: There were a few close relatives—family, and some other outsiders. It was supposedly closed. From Stebnyk, there were, I think, two or three citizens. Somehow they got in, my father told me. In practice, there were about ten people sitting in the courtroom. Although, I think—I should ask Lyubomyr—when they were leading us from the police car to the courtroom, there were a lot of people at the entrance. People must have known, because it was being talked about, there was a buzz, Radio Liberty was reporting on it... These events are so long ago, more than 25 years have passed, I've forgotten a bit. I didn't focus my attention on it.

V. O.: And after the trial, did you file an appeal? Or maybe the lawyer wrote one?

R. K.: The lawyer wrote one. I had quite an experience with my lawyer. My father hired a well-known lawyer here in Drohobych. He lived near my father's sister in Drohobych. My father's sister's apartment was across from his, on the same landing. He was a renowned lawyer in Drohobych. After some time, maybe three days or a week, he comes to us in Stebnyk and says: “Dear Mr. Kalapach, if your son had killed someone, God forbid, or burned something down, or stolen a large sum of money, I could have gotten him out. But in politics, I can't. I can't help your son in any way, I'm sorry.” Dad had apparently given him some down payment, so he returned the money, saying, “Look for someone else.” I made a big mistake by not defending myself, because in my youth I didn't know that was possible. They assigned me some lawyer in Lviv. You can imagine what kind of lawyer he was. When he came into my cell, he was eating an apple. I had been in there for about a month, it was winter, February, and he's just sitting there, one leg crossed over the other, eating an apple. He was the one who suggested I shave my mustache. You see, my mustache is gray now, but back then it was black. I still wear it to this day. He says: “Shave off your Shevchenko-style mustache, maybe they’ll give you a shorter sentence at the trial, maybe they won't convict you.” That's the kind of lawyer he was. So, could that lawyer have defended me?

V. O.: You probably know that the KGB had a list of lawyers approved for political cases. Not every lawyer could take them.

R. K.: What I'm getting at is this. I think I was waiting for the appeal because they said: even if they don't acquit you, you'll at least avoid the zone for another month, you'll stay here in Lviv a month longer. My sister lived there, and you could get a package or a delivery once a month. My sister came a few times. She still lives there to this day. Later, when I was already in the Perm camp, my father wrote me a letter saying that people had come again, even to the house, for me or my father to write a repentant statement for the newspaper to reduce the sentence. A prosecutor came to see me from Perm. I said: “Dad, it's a waste of your money, it's not a long sentence, people have been through worse.” It would have been a sin to say that we were in the camp... well, how to put it... There was always a piece of bread on the table, but the people I was with—they didn't have a piece of bread and gave their lives. So I can't complain about the conditions... For example, I was with older men like Stepan Yasnytskyi. He was my first camp teacher, old enough to be my father; his son finished the conservatory somewhere here in Lviv. He had been in the camps since 1947. Vasyl Pidhorodetskyi—now in Lviv...

V. O.: I know, I just visited him.

R. K.: He worked in a barbershop back then. Why did these men greet me so warmly? Because the idea of the national flag, the idea of the anthem, was dear to them—they fought for it, died, gave their lives, and ended up in the camps for it. And when I came to the camp so many years later, almost 20 years later, it was as if, how to say it, their hearts warmed. Because mostly the Sixtiers and Seventiers were coming to the camps by then—intellectuals, like Ivan Kandyba, a lawyer. He had a slightly different direction in the struggle for Ukraine's independence, he had slightly different ideas. He, perhaps, didn't understand those fighter-boys from the Insurgent Army; he kept his distance from them. The older generation kept its distance from the younger ones. How? Ideologically. And I was just right for them because my act was understandable to them. That's why I spent my entire term mostly sticking with and befriending our insurgents.

V. O.: And which camp were you in?

R. K.: VS-389/35—that's the Vsesvyatskaya station...

V. O.: Which people made the biggest impression on you? You've already mentioned the insurgents. Maybe you can tell a specific story about someone. There were strikes and protests there. What do you remember about that?

R. K.: I remember, why not, I remember. Of the political prisoners in the camp, the ones who impressed me most were Ihor Kalynets and Mykola Horbal, who met me right away. Since my youth, from my school days, I loved to read, especially poetry. And Ihor would offer me his works to read. He was middle-aged then, a suitable age for me, because I was probably the youngest political prisoner there. There were probably no younger ones. Later there were two younger boys from the Ternopil or Ivano-Frankivsk regions, but I've forgotten what for. One was Demydov, I think... Then there was Andriy Koroban. What connected me to him was that his wife lived in Drohobych. He was first married here... and in general, he began his activities in the Drohobych region. He told me he was setting up an underground printing press somewhere in Drohobych. He said he had a daughter here in the music college, that his wife taught music. He knew Drohobych and Stebnyk well. So when he heard I was from these parts, he came right over to me. He knew German well; I often talked with him, learned from him. What was his direction of struggle? He had spent a lot of time in Eastern Ukraine. He even traveled, he told me, to the mines, talked with the miners. His path of struggle was closer to the proletarian one, but for an independent Ukraine. That didn't divide us; on the contrary, it united us. And in general, everyone in the camp stood up for something of their own. After the Ukrainians, the largest group was the Balts, then probably the Russians, and then a few Armenians, there was one Tatar, there were Jews, the guys who hijacked the plane—that was Yagman, Gluzman...

V. O.: No, the plane was not Gluzman's case. He conducted an expert evaluation of Pyotr Grigorenko's materials and proved that he had been unjustly committed to a psychiatric hospital. The KGB figured him out and imprisoned him for that; he was not a "plane-hijacker."

R. K.: Ah, well, I mean those guys. Three of them were there, and the rest were scattered in other camps. My teachers were Stepan Yasnytskyi and Pidhorodetskyi; among the younger ones, I was in contact with Ihor Kalynets and Mykola Horbal. I loved to play chess, played well, even won a game against Volodymyr Bukovsky once.

V. O.: No-o-o...

R. K.: Yes! Under the birch trees. The one who was later exchanged for Corvalán. Honest to God. Our barracks were up on the hill, and below there were a few birch trees. It must have been a Sunday because we worked on weekdays. I worked on a lathe. I learned in a week. They only taught me theory for a week, and the second week was practice on metal. There, we mostly worked with cast iron; later I was transferred to metal products. I machined cutters, taps. But we only machined them halfway because the thread-cutting screw was removed from our lathes. The teeth and threads on the taps were cut in Sverdlovsk; they were transported in containers. We did incomplete processing. Because they were afraid we might machine some kind of weapon. The threading mechanisms on those machines were removed. That skill came in handy, because when I was released, I worked as a lathe operator at the potash plant in Stebnyk for another seven years. I reached the fourth skill category, then went to the mine, worked for three years in the mine as a timberman. First as a mine worker, then timbering in the mine. Our mines are not like coal mines—they are rock mines. I worked as a timberman and thought that I needed an education.

When I was being released from the camp, there were three representatives from the security services: one from Ternopil, one from Lviv, and I think one from Kyiv.

V. O.: And were you released there, on the spot, or were you taken to Lviv?

R. K.: There, on the spot, I came to the Vsesvyatskaya station by myself. At the checkpoint, one of them said that I would have the opportunity to study only in technical institutes. “Don't even try to apply to humanities institutes like law, journalism, or philology, we will ‘put a stop to it.’” So I thought about the mining institute, since I work in a mine. Here, in Drohobych, we still had a branch of the Lviv Polytechnic Institute. That branch had a mining department, and I tried to enroll there. I got in.

V. O.: What year?

R. K.: That was in 1984 or 1985. I enrolled late, already in my thirties. By then, I think Gorbachev had come to power, churches were starting to open, and the Greek Catholic faith was at least not persecuted anymore. I started my story by talking about my family, about my mother, my mother's sisters, relatives—my mother was a fanatically religious Greek Catholic. She attended underground gatherings. They prayed, believed in Ukraine even under Soviet rule. There weren't many of them, but a few dozen would gather. Their last gatherings were held in Truskavets, where there was a very, very old priest, over 90 years old. It was a kind of underground house. From time to time, as a boy, I would go there with my mother.

V. O.: And immediately after your release, were you placed under administrative surveillance? Was there pressure from the KGB throughout the years until independence?

R. K.: There was surveillance. For about a year I had to travel to Drohobych, where they took my fingerprints and checked for tattoos. But as for why they didn't want to hire me...

V. O.: Let's clarify. Were you officially placed under administrative surveillance? For example, being at home from seven in the evening to seven in the morning—was that established? Not leaving the district? This is what administrative surveillance entails. For six months or a year.

R. K.: For a year, I don't think so. The first month it wasn't official. Well, they asked me not to stay out late in the evenings. I would go to the House of Culture, and I could see that when I arrived, if the *druzhynnyky* [volunteer patrolmen] were there, they would all be watching me, standing nearby. Was there pressure from the authorities? This happened. I had been released for two weeks, my mother was cooking something nice... Two weeks passed—the district inspector knocks on the door, practically shouting: why aren't you going to work, why aren't you getting a job? I say, I was told to go to some office in Drohobych as soon as I arrived, to register my arrival. I had traveled to Kyiv, from Kyiv to Lviv, I didn't even stop at my sister's in Lviv, because that was forbidden. I came here by commuter train...

I went to the district office, I say: “What's the matter?” “Why aren't you going to work?” “Fine, I'll go.”

The next day I go to the potash plant's personnel department. I have a certificate—they gave it to me in the zone—stating I am a third-category lathe operator, and I ask to be hired. “Who are you? There's no place for you,” the head of the personnel department, a certain Dyomba, tells me. He says: “There is a spot, but unloading wagons.” That rock, the ore from the mine. It's so loose, white, like ash. “You can unload it there with a shovel. We have no place for you, go find a job wherever you want.” I come home and tell my father. My father says: “I can still feed you, if that's how it is. We'll look for a job. Stay home, don't go anywhere.” Not even three days had passed when that policeman comes again: “Why you?...” —and the same thing about a job. I say: “I went, but they refused to hire me.” “Who refused you?” I say: “He refused me.” “That can't be.” I say: “We can go together if you don't believe me.” We went to the mine, and I went to the head of the personnel department. He didn't know I had come with the policeman, who was in civilian clothes. People were milling about. I thought, I have support. And he shouts: “I told you”—or you plural, I don't remember—“not to come back, there's no place for you.” And then I say: “I was born here, I was allowed to come back to my parents, my parents live alone, I'm asking for a job in my specialty, here is my lathe operator's certificate. If there's no place here, then put a lathe in the Skrentsya store”—that's what I told him, we have a store like that—“I'll work there, but I'm not leaving my land.” And he pushes me toward the door and says, “Repeat that,” to the girls. There were three of them—one a neighbor, another, they're alive and well today, they laugh about it. I say: “Either give me a piece of bread, or send me back to the camp, at least there I had bread on my table every day. If there's no work, send me back to the camp.” And the policeman is standing behind the wall, hiding, listening. He says: “I'll make a call where I need to, they'll take you away again.” And he hadn't even said two words when the district inspector walks in on him, and tells me: “You sit here.” He shows his ID, says to the department head: “Into your office.” A few minutes later he came out and said: “Come with me.” We go to the workshop, you had to go onto the plant's territory. “The manager says there really are no spots, let's go and see now.” Three lathes of the same type were standing unused, you could put a person on them today, lathes of another type—again. He asks: “Which one can you work on?” I say: “I can work on that one, I've worked on that one, I can work on that one.” The district inspector goes to the head of that workshop, and he, as I was told later, was a former prison warden, his name was Shapovalov. He once took part in a “troika” that carried out executions.

V. O.: Oh, a real thug.

R. K.: They must have told him what was what, who I was. He says: “Go see the manager.” I go in, his first words were: “What was your article [of the criminal code]?” I said sixty-two, and he says: “Fifty-four or what was it?” He still knew the old articles. “Treason against the Motherland?” I say: “No, I did not betray my Fatherland.” His next words: “Will you work?” I say: “Why else did I come to you? I will work.” “Well, go write your application.”

That's how I got the job. So in a way, they helped me, because who knows where I would have been. And on the way to the plant, that inspector says: “Well, why this plant, maybe go to Drohobych, there are many plants there, we'll help.” I say: “No, it's closer to home for me here.” And back in the camp, the older men had warned me: when you get out, watch out, because they'll be watching you to catch you on something—and back to the camp. Try to get a job in a collective that you know, don't go into a strange collective. And here, I knew everyone: this one was a neighbor, that one an acquaintance, that one a relative, I went to school with that one. That's why I was so eager to go among my own people.

V. O.: Please state the years of your studies.

R. K.: I was released in 1976, on February 9. I served exactly three years, as prescribed. I started working a month later. I was registered on the third of March, I think, and by the beginning of March, I was already employed at the potash plant as a lathe operator on the most primitive machine. I earned about 60-70 rubles back then. When I was released, I was 21 and a few months old. I got married at 24, after three years.

V. O.: And your wife, who is she, what's her name?

R. K.: My wife is Yevheniya Mykhailivna; she was born in the Sambir region, in the village of Berestyane. By the way, her father is a former UPA [Ukrainian Insurgent Army] fighter, he was also in camps, but German ones. After the war ended, he returned home. He was captured—he told me. So you see, my whole family, especially my mother, is connected to the national liberation movement. So it must have been in my blood, embedded in my childhood consciousness, especially the songs I loved to listen to and sing at family gatherings. This could be at Christmas, but I remember it especially well at weddings.

V. O.: So you worked, got married. And I see you have two beautiful girls. Please state their names and years of birth, so it may be recorded.

R. K.: I worked for a long time at the potash plant. For seven years I worked as a lathe operator, then I moved to the mine. My father said: “Go, at least you'll earn mining seniority.” I worked in the mine for three years. Later I enrolled in the mining institute.

V. O.: What year did you enroll?

R. K.: In 1985, I enrolled in the Dnipropetrovsk Mining Institute. By correspondence. By then I had transferred from the underground mine to work in the mine rescue squad at the Stebnyk Potash Plant. I worked in the mine rescue squad for another 8 years, until 1992 inclusive.

When the events closer to the national liberation movement began, when the blue-and-yellow flags began to fly again, I met Myroslav Hlubish in Drohobych; he was already the head of the city at that time. He says: “Roman, how long have we known each other...” We had met before, I attended meetings of political prisoners, we had various events, we often met in the mountains, traveled with my mother to major religious holidays in different villages where services were held, where Greek Catholics gathered. On one side, there were many believers, and on the other side stood soldiers, police—there was already a confrontation. But as for any action from their side—no, they were simply on standby to prevent people from resisting. That's where I met Myroslav Hlubish and his father—a former political prisoner. And here I meet him in Drohobych, and he says: “Roman, are you still at the potash plant?” I say: “Where else would I be, I have to work.” He says: “It's time to work for Ukraine. We are independent now, our flags are flying. We need to start something in Drohobych. We need to show the first market relations that are already being talked about, so that there is real private property. After all, there used to be wealthy peasants—those who worked, had.” He says: “I have office hours on such and such days, stop by, we'll talk. They've already passed the new law on entrepreneurship. Take it on. I know you're a fighter, organize something like that in Drohobych.”

For two or three months, I paid no attention to it. But one day we had another meeting in Drohobych, and then Myroslav insisted, gave me a series of documents to read—the Law on Entrepreneurship, another one, a third one. He said it was necessary for the people in Drohobych to see that something of our own, something Ukrainian, was being revived. And he suggested I open a private enterprise.

V. O.: What kind of enterprise?

R. K.: It's a trade and production enterprise called “Roxolana.” Why that name? First, it encodes my initials—Roman Kalapach. Second, when we were starting this enterprise, it was truly a curiosity, because at that time state-owned trade was still shining, standing firmly on its feet, and they looked at us as if we were oddballs. What was private enterprise at that time? It's easier to talk about it now, in the year 2000, but in 1992, in the early nineties—that was almost a decade ago. Why the name “Roxolana”? We already had to submit the charter to the city executive committee: “What, no name?” I emphasized this at the beginning of my story, and I'll say it again, that in my youth I loved to read, I read a mountain of books, and I remembered our heroine Roxolana, who, having ended up in Turkey, still managed to stand firm, to win over the mighty sultan, she did not forget Ukraine, she defended it. Similarly, my enterprise found itself among enemies, because it was Soviet trade. Now Soviet trade has disappeared, there is collective property, private property, there are LLCs—limited liability companies. There is no more state trade, and the name “Zmishhtorh” [Mixed Trade] is gone. And we laid the foundation for its collapse. I think we were so brave in spirit that we defeated it. With the help of the authorities, of course. We were allocated premises almost in the center of Drohobych, and everything else—renovations, decoration—all at our own expense. I took out loans from the bank, all officially, on a legal basis, in accordance with the current legislation. If we had done something illegal, we would have ceased to exist by now. Of all the enterprises from that time, only this one has survived. There are few private enterprises now that are legal entities. Now there are more entrepreneurs, private individuals. And we have a registered license for foreign economic trade, a legally executed charter, and I am its director at the present time.

V. O.: And what is the correct title of your position?

R. K.: Director of the trade and production enterprise “Roxolana.”

V. O.: Good. I see you have two girls, please state their names and years of birth, so it can be recorded.

R. K.: My older daughter, Maria, was born in 1979, just two days before the New Year, at my father-in-law's house in the Sambir region. She was born on the very day that everyone remembers, because it was the invasion of Soviet troops into Afghanistan. At the maternity hospital, they said: “Why not register the girl for New Year's Day?” I said: “Why take away her birthday? Maybe if it were a boy...” She was born at night, around one o'clock, in Sambir, and in the morning we drove to my father-in-law's house by car—my wife's brother had a “Zaporozhets.” It was exactly six o'clock, and the first news on the radio was that international aid had supposedly been provided. That's how I remember it. Oh, by the way, just three months later—my wife was in the village with her mother all winter, until spring, even until fall—three months later, in the neighboring village of Rakove, there was the first funeral of a young soldier. Brought back from Afghanistan. The whole village gathered; I had never seen such a funeral. We specifically left the baby, she was three months old, and went to that neighboring village, maybe three or four kilometers from the village of Berestyane, to see that funeral. The boy was brought in a zinc coffin, there was a guard of honor, a military band played, the coffin was not opened. It was the first tragedy, and it was felt three months later.

My second daughter was born later, six years later, her name is Anna. She was born two days before the feast of St. Anna, on St. Nicholas Day itself. St. Anna's is on December 22nd, and she was born on the 19th. The Lord God must have given us such a gift for St. Nicholas Day—a daughter. She is 15 years old now. By the way, she attends the choir at the Church of the Holy Trinity in Drohobych, a well-known choir. They travel all over Ukraine, propagating religious songs, singing, performing. Two weeks ago she returned from Kyiv, from a concert. They toured Kyiv for a week, sang at the “Ukraina” Palace with Nina Matviyenko. My daughter got her autograph, she is very happy. In the summer, when Pope John Paul II came to Poland, they went there with the choir. The choir is called “Vidlunnia” [Echo], that's its name. It is recognized as one of the best, taking first and second places in Ukraine among teenage religious choirs. She went to Poland, saw the Pope up close. She is very happy, wants to sing, and goes to the Holy Trinity Church in Drohobych every other day. That church is right across from our firm. So, I have two daughters.

V. O.: Significant events took place in the late eighties and early nineties. Did you participate in the work of public organizations, were you in political parties?

R. K.: Absolutely. One of the first organizations registered here was the Society of Political Prisoners. I am still a member of that Society to this day; I participated in it from the very first days. On the initiative of this Society, if there was a need to speak somewhere, I traveled to villages, even with Mr. Myroslav Hlubish. We collaborated with other parties, with Rukh and with KUN—the Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists. As a political prisoner, I would explain things. It was still quite a difficult time then. I attended various conferences; I was invited. I went to Lviv when Yaroslava Stetsko spoke at the Third Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists. In Drohobych, I, my company, helped orphans a lot; we constantly allocate funds for them. We have the “Trident” society; back in 1994, 1995, I allocated a lot of funds for them to purchase clothing, boots, and for sewing berets. Mr. Mykola Ivanyshyn can confirm this. So, as much as I could, I took an active part. There are, Mr. Vasyl, some moments that are better not to mention even today.

V. O.: Well, I'm not an investigator to pry it out of you!

R. K.: The Decalogue of a Ukrainian Nationalist commands that one must speak of the cause not with whomever one can, but with whomever one must.

V. O.: Correct. I asked if you were in public and political organizations. You are in a public organization—the Society of Political Prisoners. As for parties, I understood that you were not in them.

R. K.: I support all parties.

V. O.: But were you a member of any party?

R. K.: A member—of none. I say: Rukh is a good party, the Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists, the Republican Party, the Christian Democratic Party... We have a doctor in Stebnyk, what's his name, Lyubomyr?

L. Starosolsky: Poriy.

R. K.: Poriy. He is the first one I help because he takes care of orphans. This year, on St. Nicholas Day, I also provided gifts for the children through him, and he is a member of one party. Those, others, thirds—I help them all, I say: “Boys, just remember: don't be divided, children, we are all the same. Don't look at it as: this party, that one, that one—we must go forward for the freedom of Ukraine in unity, not be stratified.” Our only enemies are the communists, the communist party, and all the rest of us should unite. Maybe uniting isn't possible, maybe it's even better that there are different parties. Everyone has their own opinion. I, for example, see something good in Rukh, something bad, likewise in the Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists party something I like, something I don't accept, but that doesn't mean everything is bad.

V. O.: Tell me, please, have there been any publications about you in the press or your publications about your political activities? Not as an entrepreneur, but as a political prisoner.

R. K.: Yes, back in the early nineties, two correspondents from the newspaper “Frankova Krynytsia” [Franko's Well] came to see me. There was a full-page interview with me, with a picture. I told them what I could at the time. I have that newspaper somewhere; I'll try to find it and send it to you.

V. O.: Good, please make me a photocopy.

R. K.: There was also something about me in the Drohobych newspaper.

L. Starosolsky: There is a book, *Drohobychchyna—The Land of Ivan Franko*, where Roman Pastukh wrote.

R. K.: Roman Pastukh wrote a good article about me and Lyubomyr, “The Stebnyk Stone-Breakers.” And there's also a clipping from the district newspaper, also about me and Lyubomyr, a short one. There are many. I have never gone and will never go to an editorial office and say: “Guys, write about me.” Well, glory—we don't need glory, we need to keep fighting, not to forget that the enemy is not yet asleep.

V. O.: Mr. Roman, tonight Lyubomyr and I were walking through the square where the flag stands, where there is a sign that the national flag was raised here in 1972. When this sign was unveiled, were you invited?

R. K.: I was at the unveiling.

V. O.: And did they perhaps give you a chance to speak there?

R. K.: Yes, they did.

V. O.: Why are your names not there, just: “Here, on May 9, 1972, the national flag was raised.”

R. K.: I told Lyubomyr at the time that they should have been. For some reason, they didn't want to list everyone. And then they decided either to mention everyone or it's better not to mention anyone for the time being. The initiator was Lyubomyr; I was already in Drohobych at that time, involved in business. But I was at the unveiling. Was it on November 1st or when? Or December 1st?

V. O.: When was that sign unveiled?

L. Starosolsky: In 1990, the first convocation of the council was elected...

V. O.: And when you walk by there, you probably always remember something?

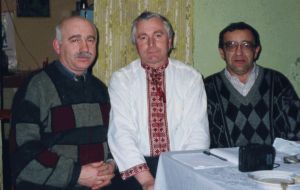

R. K.: Absolutely. Proniuk and I took pictures there last year. I took Proniuk to the Ivan Franko Museum in Nahuievychi.

V. O.: It's a shame we were passing by there tonight; it was dark and pointless to take a picture. It would have been good to have the two of you stand there and take a photo.

L. Starosolsky: If the need arises, we'll take a picture and send it.

V. O.: Good. I think our conversation has been a success. I'll set up the camera now, we'll sit like this and—click, the three of us. [Dictaphone turned off].

V. O.: Roman Kalapach, town of Stebnyk, February 2, 2000, end of conversation, approximately 70 minutes.

[End of recording]

Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, Vasyl Ovsienko, July 20, 2009.