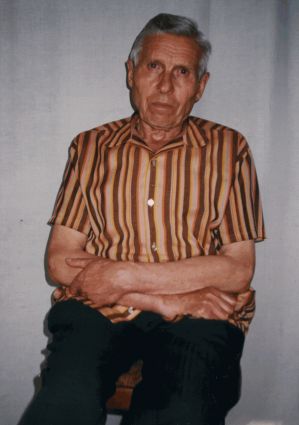

An Interview with Mykola Kindratovych P O L I S H C H U K

(With corrections by M. Polishchuk dated March 29, 2009)

V.V. Ovsiienko: June 22, 2002, Mykola Kindratovych Polishchuk. The recording is being made by Vasyl Ovsiienko at his home. Mr. Mykola Polishchuk is from Bila Tserkva, Kyiv Oblast, 64/55 Sholom Aleichem Street, Apartment 35, postal code 09117.

M.K. Polishchuk: Telephone 39-39-74.

M.P.: I, Mykola Kindratovych Polishchuk, was born on December 20, 1930, in the village of Biliivka, Volodarskyi Raion, Kyiv Oblast. Until recently, when dealing with the authorities, I concealed my place of birth because my maternal grandfather, Tsiruk Dorofii Herasymovych, had been dekulakized. Knowing that the descendants of kulaks were treated very mercilessly, I kept this hidden. It wasnt until later, in conversations with people I trusted more, that I would say that my father was a live-in son-in-law for Dorofii Tsiruk and that I was born there, in Biliivka. But on Malanka, on the Bountiful Eve of 1932, Dorofii Herasymovych Tsiruk was dekulakized. They drove everyone out of the house and warned that if anyone let them in to warm up, that person would be dekulakized too. So my mother wrapped me in an old homespun coat, in old rags, and carried me to her father-in-laws house across a field about a kilometer and a half away. And thats why I always stated that I was born in Haivoron, grew up in Haivoron, and went to school in Haivoron—that is, in my fathers house, the house of Kindrat Matviyovych Polishchuk. I dont know my distant ancestry because our lives were so fractured. It was only after my first imprisonment in 1979 that I traveled to Uzbekistan to visit my uncle, my fathers own brother, Hryhorii Matviyovych Polishchuk. He lived about 70 kilometers south of Tashkent, near the town of Almazyk. So I went there to see my uncle. And it was from my uncle that I learned that my distant ancestor, in the mid-19th century, had been traded by Count Rzewucki for a dog in Polissia.

V.O.: How do you spell Rzewucki?

M.P.: Rzewucki, Count Rzewucki. And when he brought him to Haivoron, he forbade him from using his own surname, and since he had brought him from Polissia, he gave him the surname Polishchuk. So that’s my father’s side. As for my mothers father, he had a huge family. He had a family of 14 souls in ‘22, and he was given 14 desiatynas of land, one desiatyna per soul. And from that position, my grandfather worked his way up to become a “kulak.” Ten years later he was dekulakized, even though he gave his horses to the collective farm, he gave his equipment, he gave his sheep—the only thing he didn’t give up was his cow, because his grandson needed milk. The older children—he had mostly daughters—were already married. But, based on the definition of a kulak, my grandfather wasn’t one, because a kulak was a peasant who had a farm too large to work by himself and who used hired labor. Grandfather Dorokhtei did not use hired labor. What’s more, his daughters, who were of marriageable age, earned money for their dowries by working for wealthy peasants. My mother was among them, working for the Rosinskis and the Sidletskis in the village of Biliivka. My mother never spent a single day in school, and neither did my aunts. From a very young age, they worked. From the age of five, there was a river about a kilometer away—I don’t know its name, it’s a tributary of the Berezianka, which flows into the Ros river near the village of Berezna, and this little river flows into the Berezianka—well, someone older would carry a washtub on their shoulders to that river, along with a bucket and food for the little ones, there were other small children there too. A hole was dug for the washtub, they brought water from the river, the ducklings would splash around in it, and the children watched to make sure that birds of prey, kites, didnt steal them. They played there from early morning until late in the evening. They were given a few eggs, some milk, something for the children to eat. So the whole family was like that, they didnt use hired labor, but they dekulakized my grandfather on Malanka in ‘32. At the age of seventy-one, Grandfather Dorokhtei was forced to get a job at the “Leninska Kuznia” factory. My mother’s youngest sister, Aunt Sanka, told me about this. She passed away late last April, we had the memorial dinner for the one-year anniversary on April 27th. My aunt told me how our own people, not Muscovites, were even selling my embroidered little shirts. This Anan Avramchuk was shaking the little shirts, shouting, “Buy the kulaks things, buy the kulaks things.” Sometime after that, my mother went to live with her father-in-law, Matvii Yakovych Polishchuk.

My grandfather, my fathers father, was a blacksmith and had his own forge. I know where the forge stood. But when collectivization began, the forge was taken by the collective farm. Grandfather didnt want to work on the collective farm he found work somewhere in Skvyra. My father didnt want to work on the collective farm either.

In 1933, very, very many people died in our village. The village of Haivoron is divided into two parts by the Berezianka River. The left bank has maybe a quarter of the village, and from the right bank of Haivoron, 470 souls were taken to the cemetery. I heard about this. I was still quite young, and my mother was afraid to tell me about it. My mother didnt tell me about the famine. It was my grandmother, Oleksandra, who told me about the famine, but she couldnt say how many died she didnt know. She was completely illiterate she was orphaned at the age of eight and grew up in a priests house. I first heard the number of dead from Tanas Demianovych Tokarenko. He was a land surveyor, and I was in the same class as his son. His son still lives in Bila Tserkva, his older daughter lives there too, in Tanas Tokarenkos yard, and his youngest daughter, my sisters age, lives in Kyiv on Chornobylska Street. So it was from Tanas Demianovych Tokarenko that I first heard how many people died on this side of the river.

V.O.: What part of the village was that, do you think, what percentage?

M.P.: I cant even begin to guess.

V.O.: A third of my village died, 346 people.

M.P.: No less in ours, either. I heard it a second time, maybe around 1950. I was working on the collective farm after school, and I had to spend a long night at the mill. I was dozing on some sacks, and the men—the miller was Hryhor Zaiets, what was his surname? Zaiets was his nickname in the village, but I cant recall his surname... Baybarza. And they were talking among themselves, and I overheard it by chance. The last time I heard the number, it wasnt just a number. Our field brigade leader, not a relative of mine, but also named Polishchuk, Vasyl Sylovych, was telling us as we were stacking straw in Pustokha. By the way, Pustokha is a field now, but there used to be many houses there from the village of Biliivka, all the way to the road from Skvyra to Volodarka, between Antoniv and Haivoron. Theres nothing there at all now, just a field, but I remember there were orchards, there were the ruined remains of ovens where the houses had stood. I remember this very well because I used to go to those orchards to “graze.” As soon as the cherries were ripe, Id go there to pick them. So, it was in this place that we were stacking straw, and when it rained, Vasyl Sylovych couldnt let us go because the sun came out, and as soon as it dried a bit we could get back to work. So I prodded him a little to talk, and he, starting from the very edge of the village, from the very last house, began to name them: here was a house, such-and-such people lived here—they all died, to the last one. Well, I wrote and wrote it down and came to the same number. So Vasyl Sylovych confirmed this somewhere around ‘61 or ‘62. He even named the houses and how many people had lived in them.

From our village, two women were taken to the cemetery alive. I know both of these women, I know them well. One was Yaryna Kremenetska, I dont know her patronymic, she was nicknamed Paslunka, she was also from a dekulakized family. They took her to the cemetery because the man who was collecting the bodies was hungry and said, “If you dont die today, youll die tomorrow. I have to take you away sooner or later, and Im hungry now, theyll give me a ladle of thin gruel for it.” So he took Yaryna, carried her out to the cart she was screaming, but it did her no good. He took her to the cemetery and threw her into this common pit. Somehow, she got out of that pit, Baba Yaryna, and the last time I saw Baba Yaryna, Paslunka, was in seventy-two. I had just gotten an apartment then, it was practically empty. I was visiting the village and some people asked me to help Baba Yaryna get to confession in Bila Tserkva, at the Church of Mary Magdalene in Zarichchia. I helped Baba Yaryna come here, and that was the last time I saw her. This woman lived for about forty more years after crawling out of that grave.

The second woman was Marta Dobrydnyk, Sylovna I believe, as she was the sister of that brigade leader, Vasyl Sylovych Polishchuk. She married an activist from the village of Antoniv in the Skvyra Raion his name was Dobrydnyk, and he was mentally ill. They had one daughter, and the daughter is still alive, I think, somewhere in the Fastiv Raion. Marta Sylivna Dobrydnyk lived for another fifty years or so after that. She died in the Fastiv Raion while living with her daughter, Halyna Dobrydnyk—that was her maiden name, Dobrydnyk—and the daughter brought her body back to our village, she is buried in our cemetery.

V.O.: In which village, Haivoron?

M.P.: In Haivoron, she’s buried in the village of Haivoron. I know the place in Haivoron where there was a house where a mother ate her own child—her own! There were many cases of people eating corpses, but this case of a mother eating her own child, I know of only one. And I know where that house was.

After it became freer to speak about this, I submitted a similar account to Literaturna Ukraina, and Literaturna Ukraina published it. I think that was in 1989.

In Bila Tserkva, on Stakhanivska Street, there lives a woman two years older than me. Her maiden name was Hanna Kyrylivna Virych, I don’t know her current name. After the Soviet collapsed, her father, Kyrylo Virych, was still alive, he was already 91. I asked her to get information from her father about how many people had died in 1933 on the left bank of the Berezianka. She promised she would, and she went and asked her father to tell her about it. Her father refused. He said that the people, our fellow villagers, who now hold high positions, were the ones involved in that plunder, and it was their fault that this great tragedy occurred. He wasnt afraid for himself anymore, but he was afraid for his descendants and so he named no one, not a single person. I think he was probably afraid of Volodymyr Ilarionovych Shynkaruk. Volodymyr Ilarionovych Shynkaruk was a history professor in Kyiv. Hes probably still alive, hes about three years older than me. I went to the same class as his daughter, Zoya. (Volodymyr Ilarionovych Shynkaruk (1928–2001) was a Marxist philosopher, professor, and a full member of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR (from 1978), originally from the village of Haivoron in the Kyiv region. He graduated from Kyiv University, where he became a professor in 1965, later dean of the philosophy faculty, and from 1968—director of the Institute of Philosophy of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, editor-in-chief of the journal “Filosofska Dumka” [Philosophical Thought] (from 1969), vice-president of the Philosophical Society of the USSR and head of its Ukrainian branch. His works dealt with questions of Marxist logic, Soviet humanism, and analyses of contemporary social development in the spirit of Marxism-Leninism, as well as the history of philosophy. – Wikipedia). And his father was supposedly the first secretary of the Volodarka Raion Party Committee at the time. That’s what I think, that Kyrylo Virych was afraid of him specifically. Well, I dont think that Shynkaruk could have done anything serious at that point—I dont believe that, but this is just my guess, Hanna Kyrylivna didnt tell me this.

So, 1933. Grandfather Matvii, to somehow save us from starvation, brought a pud of vetch from Skvyra. But we were no longer in the village. My mother had sent me to my fathers sister. She was in Horobiivka, working at the MTS (Machine and Tractor Station), and her husband was a cook at the MTS. They would pass me a small bowl through the window so no one would see them feeding some kulak descendant. So, on the evening my grandfather brought that vetch, he was strangled. And, as I was told, our close relative, Hryhor Martseniuk, strangled him. I dont recall his patronymic. Thats what I was told. I never spoke with Hryhor Martseniuk about this. I was on good terms with his children. His older son was my age, we went to school together, but he died early. Oleksandr is in Bila Tserkva now, he lives not far from me. I don’t talk to him.

And so, in 1934, during the harvest, my father came from Skvyra to reap the rye in our garden. The year 33 had been a great scare, so he had to prepare for the next winter. And my father didnt let my mother go to work at the collective farm—well reap the rye, and then you can go to work. We reaped the rye, came home in the evening, and lay down to rest. And then the village “comrades” arrived—Oleksandr Furmanenko, Hryhor Osadchuk, Vasyl Kyrylovych Kosiuk, and Hryhorii Petrovych Bondar. Hryhorii Petrovych Bondar also confirmed this somewhere around ‘62. So, they took my father and mother to the “kholodna” (cold cell), and Oleksandr Furmanenko conducted a search, looking for what he needed in the chests and took some things. My mother later told me what he took. There were about eleven such offenders. The next morning, they gave my father a scythe, my mother a rake and binding ropes, and Hryhorii Petrovych Bondar, a Komsomol member, marched these people, these offenders, under guard to the field. He marched them to the collective farm field under guard. I emphasize that it was to the collective farm field because later, when I got into some trouble in my adult years and the Deputy Prosecutor of Kyiv Oblast, Rusanov, came to investigate my conflict, I, in my defense against the village activists, mentioned this incident. The secretary of the party organization, Kalen Ivanovych Parubchenko, I think—he was the secretary of the party organization and the school director—really seized on that careless word of mine, that my parents were marched under guard to the collective farm field.

V.O.: You mean, with weapons, right?

M.P.: Well, yes, with weapons.

V.O.: Ill interrupt again. You said your grandfather was strangled—for that vetch, right?

M.P.: For that vetch. But hunger drove them to it. So for several days, my father, mother, and a dozen or so other people were marched to the fields. They were given lunch and dinner there, and then locked up again in the “kholodna.” And while they were being marched to work, our neighbor, Sydir Shevchuk, was given the task of taking the rye from our garden and bringing it to the “red threshing floor.” Sydir carried out this order—he took the rye, brought it to the “red threshing floor,” where they threshed it with a machine, burned the straw in the steam engine, and took the grain for the collective farm. After that, they released both my father and my mother.

I dont remember any other notable incidents being told to me after that. In 1936 my sister was born, Hanna Kindrativna Polishchuk, married name Shapoval, she lives in Bilychi, at 22 Marshak Street. My father refused to go to work on the collective farm, but my mother was a very obedient slave on the collective farm. She was terrified of the authorities, and so when I went to the first grade in 1938, my mother had a fortune-teller cast a spell for me, and the fortune-teller told her to watch me very carefully, because a great misfortune would happen. And no matter how they watched me, it was half a kilometer to the pond—God forbid I go there for a splash—they wouldn’t even let me climb a plum tree to pick a berry, they wouldn’t let me climb the fence. And my parents protected me from this, only the children of the activists constantly harassed me. One-on-one, I could successfully defend myself, but against a group, there was no defense. And so they beat me up everywhere. And my mother would add: “If you see them, run away from them, avoid them.” Well, that wasnt my way—I didnt run.

V.O.: Not in your nature?

M.P.: Not in my nature. And so, in the first grade, a group of them beat me very badly. It was already spring—probably in March—and the doctors couldnt determine the cause of my illness. It was only after I started to bend over that a completely illiterate woman, to whom my mother showed me—that woman diagnosed that I had been crippled. Then my mother went back to the doctors. I was laid up on the stove ledge for maybe ten months before they found a place where I could be treated. Before the war, they placed me in the childrens tuberculosis sanatorium in Vasylkiv. They put me in a plaster trough there. Since it was unbearable to lie in this trough, I would squirm, so they tied me to the bed. Still, Id put my hands under the apron and tear at it, so they made me a plaster vest. Worms started to breed under this plaster vest—it was terrible torture. They took the plaster vest off me in Biliivka—when the war was already going on. My mother brought me to her father, my grandfather, because she was afraid to remain in her husbands village. My mother and grandfather took me from Vasylkiv on the day the Germans took Kyiv. There were about fifteen of us children like that left, and they took me on that day.

Perhaps a very interesting point. During the war, the harvest was very good, but it rained so much during harvest time that people didnt know how to gather it. The Germans let people have the harvest in exchange for the third sheaf, and people gathered everything. There was a stack of grain in every yard. When it froze in the winter, you could hear flails thumping all over the village—people were threshing. And when the Germans began to confiscate the grain in the spring, they didnt take it like the Bolsheviks did. They would look at the size of the family and leave a pud of grain per person until the next harvest, and the rest, whoever had more, they took. The Bolsheviks, on the other hand, took everything. And here, perhaps, it would be appropriate to recall Baba Oleksandra, from whom I first heard about the famine in ‘33. I already mentioned that she was orphaned at eight and grew up in a priests family. So, in 22, Baba Oleksandra was given a piece of land, and she and her husband Havrylo built a tiny little hut. I was in that hut many times because it was sold to the man who helped with the dekulakization—Serhii Kysliuk, I cant name his patronymic, but I was in the same class as his eldest son, Vasyl. He later had two more sons, Kostiantyn, who married and went to live with his in-laws in Marmuliivka, Volodarskyi Raion, and the youngest son Mykola—he married and stayed on this homestead I think he has passed away already. Both the eldest and the youngest loved their vodka—and vodka took them both.

So, about Baba Oleksandra Hontaruk. Her husband died of starvation in 1932, either in November or perhaps December. She was left with three small children. Sometime in March, our own Haivoron “servants of the people” came to her, the same ones I already named—Vasyl Kyrylovych Kosiuk, who poked around the yard with a steel spear, Hryhor Osadchuk, and someone else, but I dont know the others. Baba Oleksandra may have named others, but I couldnt remember them. But she cursed Osadchuk all the time—that I cannot forget. So, at Baba Oleksandra’s, they found hidden bread—wheat grain in a pot in the chimney. They took the grain and beat Oleksandra. No matter how much she begged them to have pity on her children, they beat her, saying, “You hid it, you bitch, you hid bread from the Soviet authorities, hid it!” And so they beat her and took that grain—and her children died in 1933, all three of them. Baba Oleksandra left the village for some time. Ive known Baba Oleksandra since about ‘42—she helped my mother, and lived with us, because she had no home. Her house, which she had built with her husband, had three tiny little windows smaller than a television screen—and this woman was supposedly dekulakized because she didnt want to join the collective farm. It was this Baba Oleksandra who told me about her grief and about the famine in 33.

In 43, when the Germans were driven out of the village, I went to the third grade sometime in March.

V.O.: Were the Germans driven from your area in 1943?

M.P.: Ah, no, no, ‘44. My father, I think, crossed the Dnipro somewhere in December of 43, so it must have been ‘44. I misspoke. So I went to the third grade, in `chuni`—do you know what those are?

V.O.: I do, why wouldnt I?

M.P.: They are galoshes glued together from automobile tire tubes. Felt boots, sewn from old coats. And in some imported greatcoat, because it was green. The Soviet ones were gray, but this one was green. So, in 1948 I finished seven grades of the Haivoron seven-year school. I was an average student, because there wasnt the opportunity. There was one or two textbooks per class, and you had to constantly go around—doing one set of lessons with one person, another set with another. But I really wanted to claw my way out of that situation. My mothers situation did not suit me at all. And in the last ten days of August, I walked to Skvyra and on that same day passed all the exams for the Skvyra Agricultural Technical College, to become an agronomist. But an agronomist I did not become—it didnt work out because I caught a cold. I used to walk barefoot, and that was the end of my studies. In the spring, I went and took my certificate, and it wasnt until 1952 that I left for Donbas, enrolled in an evening school there, and worked at the Kirov Plant.

But I need to take a small step back because I missed a very important detail from my mothers life. When I was put in the hospital in Vasylkiv, my sister was about three years old she was in kindergarten. The nanny was washing the windows, standing on a stool, and for some reason the child came up and tugged at her skirt. The nanny jumped down and broke the childs leg. Because of this turn of events, in 1940 my mother was 11 `trudodni` [workday units] short of the established minimum. Because my father refused to work on the collective farm, and my mother didnt make the required minimum `trudodni`, the household of Kindrat Matviyovych Polishchuk was excluded from the collective farm and subjected to individual-farmer taxes—which meant all taxes were twice as high. They took away our garden, leaving only a path to the road, and sowed millet in the garden. They warned us: If even one of your chickens is found in the millet, youll have to compensate for the difference between the harvest we planned and the one we gather. Because of this, my mother didnt have a single chicken. In 1941, about a month before the war, all our property was seized for non-payment of taxes, including the house, down to the last bedsheet. If the war hadnt started, we would have been without our home, my grandfathers home, once again.

I also missed one very important detail—the famine in 1947. In 47, I ate potatoes that the peasants had grown in 1941. There is no mistake here. Ill explain. Back then, when the Germans were confiscating surplus grain, our people didnt open their potato clamps so as not to give the potatoes to the Germans. And so those potatoes remained. The famine forced them to remember these potatoes, because people were eating exclusively lambs quarters, linden leaves, things like that, living on foraged food. And when people remembered those potatoes, they opened one clamp, and of course, there were no potatoes inside, but rather something like pancakes there was starch, wrapped in potato skins. The stench was as if all the outhouses in the village had been opened. But they got these potatoes out, took every last one, cleaned off the skins, spread them on cloths in the sun to dry and air out, and then they pounded this starch in mortars. And that was a delicacy—the porridge was tasty, and they made all sorts of things from it. But only after it had aired out and dried.

V.O.: Perhaps they were called matorzhenyky?

M.P.: No, those were potatoes. Matorzhenyky were made from last years frozen potatoes, those that were missed in the rows and found in the spring when digging the garden. They were frozen, rotten, and they stank too, and they were also cleaned, but matorzhenyky were from those potatoes. They made the matorzhenyky from them right away.

V.O.: A different recipe, as bitter as it is to say.

M.P.: Yes, yes, a completely different one, and a completely different product. This product had been sitting from 1941 to 1947. So, after I couldnt study in Skvyra, I began my working life on the collective farm as a gardeners apprentice, under Tomasz-Khoma Havrylovych. (This mans last name was Blyndaruk. Probably from the German word: “blind”—sightless. His first name was Tomasz, and thats what he was called in the village. But the village leadership called him Khoma. They also wrote “Khoma” in the timesheets. – Note by M. Polishchuk.) It was in Tomasz-Khoma Havrylovychs yard that the house stood where the mother ate her child. His son lives in that yard now—he had one son, and an older daughter. And this son still lives there. My duties included keeping a record of peoples work. People worked in three places, so I had to run around, especially in the afternoon, measuring how much the women had weeded, how much someone had cultivated, harrowed, and so on. They paid me 0.75 trudodni as a gardeners apprentice.

The next year I was a milk recorder at the dairy farm, and in all my life, there was no worse job than being a milk recorder—not because the work was physically hard, but because I never had time to sleep. They milked the cows four times a day back then. We had to cull the cows, to bring in better ones and send the low-producers for meat. So, they started milking at four in the morning until six, and I had to record the milk from each cow separately. By six oclock, I had to take this milk to the separator, pick up the skimmed milk, and deliver it to the pig farm, for the piglets, the calves, and then I was free. At ten oclock they started milking again, until twelve. Again, I had to record everything, take it to the separator, it off, bring back the skim milk. At four in the afternoon, they started milking again, until six oclock in the evening. And in the evening, the same thing—they milked until ten oclock, but this milk, from the third milking, I didnt take to the separator, but I did take the daytime milk. When they finished milking at midnight, there was nowhere to take it. I would sleep right there at the farm, in the straw, because at four in the morning I had to be recording milk again. My eyes were swollen shut.

I was fired from this cushy job—fired because I embarked on a criminal path. It so happened that one time after a rain, a man who transported cream to the butter factory in Volodarka and I were carrying a can of cream. This man hadnt closed the lid properly, the can opened, and we spilled about ten liters of cream. When the milkmaid saw it—it was the end of the month—she was in tears, she couldnt say a word: What am I going to do now? How will I cover this? There was no one to buy more from and no money to buy it with. Well, I took a risk, thinking, I’m not just anyone—I’m the recorder. I told her I would cover it for her with milk. I immediately skimmed off maybe twenty liters of the milk I had brought. I returned to the farm and immediately made a correction in the logbook. If only it had been written in pencil—but it was written in pen. And the farm manager, Omelko Kysliuk, discovered it and immediately reported it to the accountant, Fedir Zakharovych Kysliuk. And he was very angry with me because I was a pretty good artist. By the way, when I was in the third grade, I drew a portrait of Stalin, and it hung in the seventh-grade classroom for several years until printed portraits appeared. For that, I got to go to the movies for free—they would give me a few meters of blank film, I was supposed to draw something, write something, and then they would project it onto the screen before the film. Well, I had written something about this accountant, and this accountant almost beat me up. But since I wasnt afraid, he didnt dare hit me. The zootechnician, Ivan Stepanovych Melnyk, came to my defense—he was a live-in son-in-law in Haivoron. He always spoke very well at meetings and defended me very actively, saying that this was not such a major criminal offense that anything could be made of it.

But they removed me from that job, and I started doing various jobs on the collective farm. I felt incomparably better doing different jobs, because I was no stranger to a spade or a pitchfork. And that summer, my friend and classmate, who worked in Donbas at the Kirov Plant as a train assembler, returned on leave. He convinced me that the work I was doing on the collective farm was much harder than what he, a big, healthy guy, was doing there on the railroad. All he had to do was connect two or three cars, whistle to the engineer, wave a lantern at night or a flag during the day—and off they went. He hadnt gone there alone either his brother, also a friend of mine, now lives in the village of Bloshchyntsi, Bila Tserkva Raion, thats Ivan Semenovych Ilchenko, born in 1928… And my friend Mykola Semenovych Ivchenko, his younger brother, who worked with him in Makiivka, persuaded me to go with him and work there. And he would help me get a job, because he already had experience there. And I went with him.

V.O.: And what year was that?

M.P.: That was in ‘52, in the summer. When I got there, my idea of a factory was that if theres a smokestack, its a factory. Because we had gone on an excursion to Horodyshche, to the sugar factory, and there I saw a small steam engine and a smokestack for the first time—that was a factory. We arrived in Makiivka—and there was a forest of smokestacks. So I asked this Mykola, “Mykola, which factory do you work in?” “The one were walking towards.” And this factory was seven kilometers long and about two kilometers wide. We were walking along the railway tracks. And here were four rolling mills, two open-hearth furnace shops, and from each open-hearth furnace and from each furnace—a smokestack, a smokestack, a smokestack. There was a forest of smokestacks, and I couldnt make any sense of it. And for a long time, I couldnt understand...

But we arrived in Donbas, and I lived in his room. There were four of them living there, there was always a spare bed, and when there wasnt, I slept in the same bed with him. But it was impossible for me to get a job—I couldnt pass the medical commission anywhere. No matter how much I explained that I had done much harder work on the collective farm, it convinced no one—pass the surgical exam. I couldnt pass, and the Makiivka city Komsomol committee helped me get a job—I was a Komsomol member back then, I was a Komsomol member for a whole five years.

V.O.: Since what year?

M.P.: Around ‘48 or ‘49. Yes, from ‘49. And I joined the Komsomol on a bet—I bet that they wouldnt accept me into the Komsomol, and the secretary of the Komsomol organization said that they definitely would. When we went to the Volodarka Raion Komsomol Committee, he introduced me as a very active young man, and they started asking me for my biography. Right there, I said that my grandfather was dekulakized, that my father had been expelled from the collective farm—I thought these were my biggest trump cards. No, Mykola Yanchuk (also an Ivchenko, but from a completely different Ivchenko family) insisted that I read a lot of books, that I participate in creating the wall newspaper, that when the film projector comes, I always participate in highlighting some moments of village life. He insisted that they accept me anyway. They asked me: well, if hes telling the truth, what kind of books do you read? I said that I love reading Dumas, I love reading Dreiser, Ive read Conan Doyle. Only Western authors came out, and he said to me, “Look, you’ve read ‘People with a Clear Conscience.’” “So what if I read ‘People with a Clear Conscience’—can you compare it to ‘The Three Musketeers’ or ‘The Exiles’?” Well, I thought, this is it, they definitely wont accept me now. They accepted me into the Komsomol. They did, and so I became a Komsomol member.

And that helped me get a job—they hired me as a plant guard. This was very necessary for me, because I came not so much to earn money as to get some education—I needed to go to the eighth grade, the evening school. There was no Ukrainian school in Makiivka, and they didnt want to accept me into the eighth grade: You studied in a village school, and this is a city school, the workload is much greater, you wont be able to keep up. I said that if I couldnt keep up, I would go back to the seventh grade, but I insisted on going into the eighth. Oh, there were so many of us!—three to a desk, and some even stood by the desks writing things down. But that only lasted for about three weeks or a month, and then everyone was sitting at the desks, and then two to a desk, and by spring, there were less than twenty of us left.

V.O.: And where did they all go?

M.P.: It was hard, they quit, they couldnt take it. My first grade in geometry was a D, even though I knew the material well. It was difficult for me to answer in Russian. And the teacher said to me: “I can tell you’ve studied something, but you have to understand, youre in an evening school, you have to answer clearly. For the first time, Im giving you a D, and when youre ready, Ill see.” And after a while, this teacher gave me nothing but As, because it turned out that I gave him a very good zinger. Because of my bad character again, the plant security sent me to a post that everyone avoided—guarding explosives.

Heres what happened. I was already going to school, and the secretary of the party organization demanded that everyone in the security subscribe to the newspaper Makiyivskyi Robochyi (Makiivka Worker). But I told him that I didnt want to subscribe to a Russian newspaper—subscribe me to Radianska Ukraina (Soviet Ukraine). He told me, “You understand Russian, and we wont allow you to disgrace our collective—everyone must subscribe to the newspaper ‘Makiyivskyi Robochyi.’” Since “everyone must,” I also paid, but when I returned to the dormitory—I lived in dormitory No. 6 in the Sovkoloniia district then, and studied at the school for working youth No. 2, which was on the Ninth Avenue of Makiivka... So, having returned to the dormitory where only security guards lived, there were nine of us—I was the youngest, and the others were my current age, old men—I immediately wrote an indignant letter to the newspaper “Radianska Ukraina”: why cant I subscribe to the newspaper “Radianska Ukraina,” and theyre forcing a Russian newspaper on me? About a month passed, and they chewed out this secretary. He came running to my dormitory: here, take this receipt for the newspaper Radianska Ukraina and sign here that you have this newspaper and have no complaints against me. Well, my request was satisfied, so I signed.

One time I was on duty at a post called TsEVKH, Tsentralnaia Vozdukhoduvnochnaia Elektrostantsiia (Central Blower Power Station), thats what it was called then. There were two posts there—one at the ash-handling plant and another by the administration. The latter was considered prestigious, while here, at the ash-handling plant, there was a lot of dust, soot, and such a racket that you couldnt have a normal conversation. What was it? There were five mills—horizontal barrels about three meters in diameter, lined inside with corrugated cast-iron plates. Coal was constantly fed into these barrels, and cast-iron balls rolled over these corrugated plates, grinding the coal into dust. Fans then blew this dust into a boiler. The boilers were about the size of a three- or five-story building, thats how big they were. The dust burned there and the soot was discharged through the smokestack. You couldnt get away from this soot in the city especially when the wind was from the southwest, the soot would fall on the city and on the dormitories.

And so I was at this very post. I had taken a bench outside, and I was sitting on that bench when the director of this power station, Batmanov, walked by, and I just sat there. I knew the director was coming—so let him come. But he walked about three steps past the post, then turned back and asked, “Guard, why arent you checking passes?” I answered him that I know you—you’re the director of the power station, a celebrity. He had just received a premium, the “Pobeda” car, so it was impossible not to know him. “Yes, that’s true, but they could have fired me yesterday. And you are obligated to check everyone’s pass. No matter how many times he comes here, you are obligated to check his pass every single time.” Well, I jumped up, stood at attention, apologized: Forgive me, I will be more disciplined from now on. This same Batmanov passed by about five times before lunch, and each time I leaped up from that bench, pulled my carbine to me, stood at attention: “Your pass?” He’d say: “There, well done, that’s right!” Id read it—Please, proceed.” But the fifth time, he lost it—he ran and called the guard commander. The guard commander came running, I was replaced, and immediately received instructions that this was no way to behave.

After that, they sent me to this worst post, where there was no one. Youre there alone, no heat, no fire, nothing—just a telephone and a large pile of felt mattresses, about two centimeters thick and a meter or so wide. And a huge black sheepskin coat, so big I could wrap myself up in it completely. So, at this post, I studied my lessons very well. And thats exactly what happened with that geometry teacher. I was studying the lessons ahead of time, and when we had the topic of inscribing a circle through a given point within an angle, the teacher explained it hastily. Then I raised my hand and said that he had only drawn one circle, but another one needed to be drawn. He told me, “The second circle cannot be inscribed.” “Allow me to do it.” “Well, come on up!” I went up and inscribed the circle—and after that, he only gave me As. The same in the ninth grade—only As. And so on the exam, my godfather, Oleksandr Laitarenko, and I (I have one godfather and one godson somewhere—I disliked the ceremony so much that I later didnt even go to be godfather for my own relatives, for my cousin), well, my godfather and I were a little late for the exam, and our classmates made fun of us: why are you so late—the problems are already here, weve solved them, and youre just showing up? Because they made fun of us, we sat in the general classroom—there were three ninth-grade classes, our class was by the windows, but we sat all the way by the door, separately, in the second classroom. I did my work and my godfathers work, but I didnt have time to fully copy over my own. Well, I figured Id get a C—so I handed it in and left, I didnt care about the grade. And in this way, I greatly offended that math teacher. He came up to me: “Why didn’t you pass the exam? Why did you treat it like that?” And I asked, “What, didnt I get a C?” “You got a C, but you need an A!” “Why do I need it? A C is fine with me.”

Well, they kicked me out of the tenth grade—because of Tychyna. Not so much because of Tychyna, as because I asked the teachers inconvenient questions. They gave me a piece of paper stating that I had studied in the tenth grade—and with that, my general education came to an end.

After that, I returned home, because my stepfather had been run over—he was coming back from seasonal work and got hit by a car. My mother demanded that I come home. I returned to the collective farm. My stepfather left me a cow, he left me a beehive. He really wanted to build a new house and had managed to acquire some materials. So in 1955, I returned to the village.

But no, I have to go back again, because it didnt end there. I had also left the Komsomol in Makiivka. And they didnt expel me from the Komsomol I spoke at a meeting and said why I didnt want to be a Komsomol member, and I handed over my Komsomol card. This is not a trivial detail.

V.O.: And why didnt you want to be in the Komsomol?

M.P.: Because you werent allowed to speak Ukrainian there—you had to speak Russian. I lived in the same room with two secretaries of Komsomol organizations. By the way, I did transfer to the railway department. Again, I committed a crime—when the holidays started, I passed the commission, but for the surgical office, I sent my friend Petia—I owed him a drink, just pass the surgical office for me. Petro passed the surgical office, and I gave him a bottle. I was hired, but two weeks later, they suspected that my health was subpar. Then the station master came, accompanied by his deputy—for me to go through the commission again. They immediately sent me to the surgical office, and the surgical office immediately rejected me—I couldnt do this work. No matter how much I tried to convince them that I did much harder work on the collective farm—no, and that was that. But two weeks had already passed, they couldnt fire me, so they transferred me to be a railcar clerk, in the same railway department, to another station. And again, I lived in the same room with two Komsomol organization secretaries—the secretary of the service was Bilonozhenko, Tolya, I think. This guy was very clever, he designed a tape recorder back then. And the secretary of the workshops Komsomol organization was Volodymyr Kozhedub—this blockhead, this yes-man, he knew how to curry favor. He was an instructor for locomotives. The first was a locomotive engineer, and he was an instructor. There was a phone to our room for this instructor. And because at the Komsomol meetings they wouldnt let me speak in Ukrainian—they let me a couple of times, then stopped—one time I defiantly went up to the podium anyway. By the way, the Komsomol organization there was very large. The railway department served the entire plant, and the department had 11 railway stations. The plants railway department owned 300 kilometers of railway track. There were about five thousand workers, and the Komsomol organization had about 500 members. The meetings could never be fully attended because people were always at work, but about 200 would gather. And so I went up and said that I live in Ukraine, and here we have such outrages: I couldnt find a Ukrainian school, the Russian language dominates everywhere, the Ukrainian language is oppressed, and even at Komsomol meetings I cant express my opinion. The goal of a Komsomol member is to become a Communist, but I dont want to be a Communist like Ogarkov, like Belyaev—which means I have no goal. Please, take my Komsomol card from now on, I am not a Komsomol member. I stepped down from the podium, took out my card, placed it on the table in front of the chairman, and walked out the door. There was a commotion: Wait, stay. And whereas before they wouldnt give me the floor, saying hell just start droning on in his Khokhol language, when I made that last speech in Ukrainian, how attentively they listened, oh, how attentively they listened! Then, quite a few Komsomol members spoke up in my defense, all Russian-speakers, mind you, but they spoke in my defense. They also assessed that I should have a good future, that I shouldnt leave the Komsomol, that I would definitely become a Communist, a useful Communist for the Soviet , but I never took the card back. For another six months, people from the plants Komsomol committee and the city Komsomol committee came to see me, but I didnt take my Komsomol card back.

V.O.: This is an important event, but can you remember when it was?

M.P.: That was already in 1955.

V.O.: Did you mention the name of that plant?

M.P.: I dont think so. It was the Kirov Metallurgical Plant, in the city of Makiivka, which was then in Stalino Oblast, now Donetsk. Back then, there were 12 kilometers between Makiivka, Shchehlova, and Donetsk a tram ran there. There was one little tram. Makiivka had about 500,000 inhabitants then, but it was very spread out because the houses were mostly one-story, made of wood, built from railway sleepers. There were a few multi-story brick buildings, and the largest was an eighty-apartment building. There was even a tram stop called Eighty-Apartment Building, that was a stop. And because in the tenth grade I started asking the Ukrainian literature teacher inconvenient questions, they gave me a warning once. The school principal gave me a huge lecture: If you dont understand something, ask the teacher. Fine, Ill ask, I raise my hand, the teacher says, Later. As soon as the lesson ends, the teacher is out the door and gone, and you cant ask. And so I pestered them to the point that they expelled me from the tenth grade.

I enrolled in correspondence courses at the Rzhyshchiv Construction Technical College. I successfully graduated from this technical college.

V.O.: And in what years were you at the Rzhyshchiv college?

M.P.: I graduated from the Rzhyshchiv college in February 1964.

V.O.: And when did you start studying there? Probably three years?

M.P.: Yes, I studied for three years. The college administration even thought I would probably graduate with honors. I had to retake one control assignment I got a C in reinforced concrete because I was sick, so I had a C, and I had to redo the course project. And they would have helped me, but again, I wasnt interested in grades. I had almost all As, but I didnt get an honors diploma.

Here’s another little thing. I was the only one who did my course project on structural statics in Ukrainian. I felt that if I kept my convictions, they would kick me out of here too. So I had to offer a moral bribe: I switched to Russian and defended my diploma in Russian as well.

But there was no work for a technician in my village. At that time, a thirty-thousander, Oleksandr Trokhymovych Otamanenko, was in charge, a very, very big sycophant he knew neither Ukrainian nor Russian. He finished seven grades before the war, and after the war, he completed a one-year party school and worked as the deputy director of the MTS for political affairs. When the MTS was reorganized into an RTS (Repair and Technical Station), he was sent to do leadership work in agriculture. Thats how he ended up with us. Although I couldnt get along with our own, local collective farm heads, I very quickly felt what it meant to have an outsider. He surrounded himself with a coterie of sycophants, and there was no way forward for me—they gave me exclusively hard physical labor, exclusively.

I had an accident. I had been working for a year, and this collective farm chairman had to give a report. Before the report meeting, the grain had to be reweighed, and I, while reweighing it with the other farm workers, went up to the attic of the cowshed. There was no ladder, so the guys climbed up using the gates, and I was the last one left with the son of that Hryhorii Petrovych Bondar, the one who had marched my father to the collective farm field under guard. He was a year older than me. I brought a ladder and said, “You go on up, and Ill hold it here so it doesnt slip, then Ill climb up.” He climbed into the attic, and it happened exactly as I had predicted—as soon as I put one foot on the attic floor, the ladder slipped out from under me, and I fell down onto that very ladder, onto the rungs. They had just unloaded beet pulp from a truck, so I landed face down in the pulp. They took me to the hospital in Volodarka, where I stayed for 17 days.

V.O.: When did this happen?

M.P.: That was sometime around 1963, I think, or maybe 1962, I cant recall exactly. I didnt want to be there because the New Year was approaching, so I checked myself out of the hospital with a fever. They told me to come back in March to check my health. I went there, and they gave me a certificate stating that I could not perform physical labor. But the collective farm chairman said, “You can use that for toilet paper. You can bring me a whole armful of certificates—they wont mean a thing to me.” I think it must have been in 1962. And so I failed to meet the required minimum of workday units.

V.O.: And did you injure yourself when you fell?

M.P.: No, I was already injured in the first grade at school. Nothing happened this time—perhaps my lower back still feels it to this day. Just yesterday, I stepped a bit too sharply from the curb onto a trolleybus—and either its sciatica or something else reminding me in my lower back. This happens often, especially now.

So, I didnt meet the required minimum of workday units, and for that, they imposed a 50% higher tax on me, and I was forced to pay it. I later spoke about this at meetings more than once. By the way, its probably worth noting here that there were men in our village, older than me, who, probably because I yapped a lot at meetings, would come to me and tell me about various wrongdoings—they would give me topics to talk about. I made an agreement with these people that I was willing, but since you saw it, you know about it, you should be the one to talk about it. “But I cant tell it like you can.” “Ill help you. Lets write it down.” We’d write it out. “Okay, now memorize it like a poem, and then you can recite it.” And I never once succeeded—all these people who provoked me to speak out later ran for the bushes. There was always some reason—he was drunk, or something else, always some very compelling reason why he absolutely couldnt speak, just couldnt.

Here’s another incident. There was a general party line to consolidate administrative units—they were consolidating raions, consolidating collective farms...

V.O.: That was in 1962, under Khrushchev. Thats when they created industrial and agricultural raions.

M.P.: Yes, yes. They sent us this thirty-thousander and merged two collective farms—the Komintern collective farm, where I grew up, in the village of Haivoron, and the village of Petrashivka, which borders Haivoron on the left bank of the Berezianka, where the Shevchenko collective farm was. Our collective farm chairman was my fathers age, with four grades of education from the Haivoron zemstvo school, while the other man, Kuzma Burlachenko, had two grades. Understandably, both were party members, and thats why they were collective farm chairmen. But when they were replaced and this thirty-thousander was put in charge, I very, very quickly felt what that was like.

So a year passed. The Volodarka Raion Party Committee was very pleased with this Otamanenko they wanted to attach another collective farm to his authority—the collective farm in the village of Biliivka, the village my mother was from. They had already held a closed party meeting and a general collective farm meeting at the Frunze collective farm there, and they sent delegates here to merge these two collective farms as well. And at this meeting—it was in the village of Petrashivka, there was one village council by then, but the meeting was held in the village with the larger club. Eleven people from the party-activist group spoke, telling of the benefits that would come from such a merger. I spoke after everyone else, even though they werent going to give me the floor. Again, I spoke defiantly and explained why this shouldnt be done. I warned the Biliivka people, especially, how bad it would be for them, because they would have to run three kilometers to Otamanenko for every little thing, just to get a piece of paper signed. And he would also tell them not to say tovarysh holova (Comrade Chairman) but tovaryshch prysydatel (Comrade Chairman in broken Russian). And if they didnt speak to him properly, he might not sign it at all. Well, the people started murmuring that he was telling the truth, because his mother was from that village, so he knew that village too. I knew these villages very well because I had been a postman in the village, so I knew everyone there—from the oldest to the babies in their cradles.

And so, after my speech, they put it to a vote. Ive forgotten who was chairing. He put it to a vote and announced, Passed unanimously. I stood up and started screaming, Youre very bad at math—Im bad at it too, but I can count to a hundred. I counted eleven speakers, and those very same eleven voted for, and the rest didnt vote. I voted against, and you didnt even see me. Well, a commotion started, and they held the vote again. They recounted—the club was divided by an aisle, and they tasked me with counting the votes on the left side of the aisle, facing away from the stage, and Petro Oleksiyovych Ishchuk (he had also been a collective farm chairman here and had whipped people with a horsewhip in 47) was tasked with counting the votes on the right side of the aisle. They repeated the question, who for, who against—and again, the same eleven who had spoken, the disciplined party members, voted. They finished, I was the only one against. I shouted, straining my lungs, “Petro Oleksiyovych, how many did you count?” What could he do? He said he counted eleven. I turned to the chairman and asked, Did you hear how many votes Petro Oleksiyovych counted in favor of merging the Shevchenko and Frunze collective farms? He didnt answer, but announced, Passed unanimously with one against. I was against, and everyone else was for.

V.O.: But they didnt even vote, did they?

M.P.: They didnt vote. Then the outraged people stood up and left the club, while the presidium remained on stage. About two weeks later, a policeman came for me. Right after the war, I had plowed a field behind the same plow as this policeman, Serhii Maikut—he held the plow handles, and I led the horses. So Serhii came and handed me the charges, on a big sheet of newspaper, I read it and said, You know what, Serhii, youre not taking me by yourself.

V.O.: Wait, what do you mean on a big sheet of newspaper—was it written in the newspaper?

M.P.: No, the charge sheet was as big as a newspaper. And he said, Im not going to take you, but you must understand that if I dont bring you to the police station, it wont be long before, if you cant defend yourself legally, theyll bring you in tied up, and youll end up wherever they see fit. Article 206 of the Criminal Code—hooliganism, for disrupting a meeting.

V.O.: So, this was 1962, the merger of collective farms?

M.P.: No, this was a little later, not sixty-two. This was probably around sixty-three.

V.O.: But when Khrushchev was removed in October 1964, they immediately reversed all that consolidation.

M.P.: Immediately. As soon as Serhii got on his cart and left, I locked the house and ran... I went to Kyiv to my sisters place in Bilychi, at 22 Marshak Street. I really wanted to see my highest-ranking deputies. At that time, we had voted for Synytsia, who was the secretary of the Kyiv Oblast Party Committee—to the Council of the , and Oleksandr Yevdokymovych Korniychuk—he was elected to the Council of Nationalities. I really wanted to see these deputies, to tell them and ask them how one was supposed to understand all this. But I didnt succeed. I spent almost a week and got nowhere—I didnt see either one of them. I tried to get to Synytsia through the Oblast Party Committee, but they kept turning me away for various reasons, and then they told me not to even look for him in Kyiv anymore because he had moved to Odesa.

V.O.: Yes, he became the Oblast Committee secretary in Odesa.

M.P.: Whether it was true or not, in any case, thats what they told me. So I decided to get to Oleksandr Yevdokymovych. His address was nowhere to be found—they wouldnt give it to me at the Supreme Soviet or at any information bureaus. At the Supreme Soviet, a guard suggested I try the Writers —they would certainly know there. I went to the Writers , at 2 Ordzhonikidze Street, now Bankova Street—and no one there knew either. I left the small office, where a secretary or someone was, I dont know, there were a few people there, but as I was leaving the premises, I said very briefly that I was in such trouble: Im supposed to go to prison, but I havent committed any crime, and this is my last hope, and now I dont know what to do. But these people said nothing to me. I went out, walked down the corridor to a window, and stood there thinking about what to do next. Then the woman who had listened to me there came up to me and said that she understood me, that she sympathized with me. “But Oleksandr Yevdokymovych Korniychuk is a very, very big shot, he doesnt receive people of our rank but if you dont give me away, Ill tell you where he lives. For some reason I trust you, but I must warn you, because Ill get into a lot of trouble: Oleksandr Yevdokymovych Korniychuk lives at 10 Karl Liebknecht Street, apartment 28. Hes at home now I wish you all the best, may God be with you, but I beg you again—dont let slip where you got this address.” I promised her I wouldnt. A few minutes later I was there, in front of that gray building, and rang the bell immediately.

A stout woman in a beautiful embroidered Ukrainian shirt opened the door. In Ukrainian, she asked what I wanted. I asked if Oleksandr Yevdokymovych Korniychuk lived here. She confirmed that he lived here. So I have just one question: where and when does Oleksandr Yevdokymovych Korniychuk receive his constituents? Instead of an answer, she countered with a question: “And where are you from?” I told her I was from Haivoron, Volodarskyi Raion. “No, you are not his constituent, he will never receive you.” I started to explain to her: how can that be, I know very well that we voted for Synytsia for the Council of the , and for Oleksandr Yevdokymovych for the Council of Nationalities back then. “No, you did not vote for him, he will never receive you. You did not elect him.” Well, I understood that people like me didnt elect him—he was elected by someone a little different, and he receives those who elected him.

V.O.: And this woman—wasnt she his wife, Liubov Zabashta?

M.P.: I dont know who she was.

V.O.: His first wife...

M.P.: Wanda Wasilewska was, but she was skinny.

V.O.: And the poet Liubov Zabashta was his second wife.

M.P.: I dont know. A stout woman, stout. I only saw her face for 2-3 minutes.

V.O.: Evidently, it was her.

M.P.: Well, that was the conversation.

V.O.: And when was this?

M.P.: This was probably during the harvest of 1963.

V.O.: Wasnt 1963 the year of the bread shortage—do you remember? There was no bread. Pea-flour bread…

M.P.: No, some time had passed since then. That pea-and-corn bread... my neighbor would send his wife to Volodarka in the morning to buy a loaf of bread, while he worked as a fodder-man. After finishing his work at the farm, he would go to Skvyra to buy two loaves—this was the year after that. The year after you had to get buns by prescription. So from there, from 10 Karl Liebknecht Street, apartment 28, I didnt know where to go. Then I decided, come what may, I had to go to the prosecutors office, and so I went to the Kyiv Oblast Prosecutors Office. I arrived in the afternoon, the secretary told me the oblast prosecutor wasnt in, but if I wanted, I could see the deputy prosecutor, Rusanov. I said I had no choice, I was willing to see Rusanov. She went into Rusanovs office and immediately invited me in. He was alone in his office. As soon as I opened my mouth and told him what had happened, that there had been this meeting and that I was being accused of disrupting it, but that I had done nothing illegal, that I had behaved in a disciplined manner—he didnt let me get another word in. He jumped up, started pacing around the office, and started shouting about the party line and how I was undermining it—God forbid... When he was done shouting, he said, “Go home, I will come personally tomorrow, I will sort this out myself. This time, there will be no arrest, but be warned, there will be no more forgiveness for you in the future.”

It was too late to leave then, it was already four in the afternoon. We left his office, and he immediately told his secretary to call Volodarka. I went back to my sisters, spent the night, and took the bus early in the morning. By the time I arrived, it was also around four in the afternoon. I had just stepped over the threshold, not even had time to fry a couple of eggs, when my neighbor came running: Oh, youre home? Run! Run away, theyre going to arrest you today. Some cars came, and the head of the village council was asking if you were home. Run! Well, I didnt see you,” he slammed the door and fled. Maybe five minutes passed, and in comes a major activist, Oleksii Kosiuk. What was his patronymic, I forget. Well, there was only one Oleksii Kosiuk there, he lived with the village elders family as a son-in-law, he really didnt get along with the village activists and constantly provoked me, saying, theres this or that injustice, you tell them at the meeting, because I cant do it as well as you. He came in just the same: “You’re home? Run! Some strange cars have arrived, theyre going to arrest you today. The head of the village council asked if you were home.” And he warned me that he hadnt seen me. No sooner had he left and I had barely had a bite to eat, when the messenger came and told me to go to an expanded meeting of the collective farm board.

An expanded meeting of the collective farm board—that was a real marvel, because this thirty-thousander never did anything like that. At a board meeting, only the people who were invited could be present, no one else was allowed. But this time they made three announcements that there would be such an expanded meeting of the collective farm board. When I arrived, you couldnt squeeze into the club—it was packed with people. I arrived, knowing I had to go up to where the presidium was, because thats where I saw Rusanov and the collective farm chairman, and the head of the village council, and our activists. So I went there, they sat me on a long bench, and the meeting of the collective farm board began.

V.O.: And where was this bench—on the stage, perhaps, or in the hall?

M.P.: In front of the stage.

V.O.: As if you were the defendant?

M.P.: In front of the stage. The collective farm chairman reported on the progress of grain delivery—they had met and exceeded the quota for grain crops, only the corn was left, but the corn was still green. He was confident that they would exceed the corn quota as well. With that, the chairmans report for this expanded meeting of the collective farm board concluded. After that, he gave the floor to Rusanov. Rusanov began to intimidate the collective farmers...

V.O.: And what language did he speak?

M.P.: Ukrainian, flawless Ukrainian. He started scaring people about the high crime rate in Kyiv Oblast. He reported how many crimes had already been solved, how many people had been convicted. And here in Haivoron, too, not all is as it should be. Among you lives a certain collective farmer, Mykola Kindratovych Polishchuk, and he is preventing you from building communism. So, I would like for those people who have worked with him, because its impossible that no one ever spoke to him, I would ask those people to tell us how they tried to bring him to his senses and how he reacted to their good advice. At this, he fell silent. But no one was eager to say anything. He stood up again, began to shame the people, saying that he understood they were ashamed to have such people living among them—but you must understand that you need to build the future, and people like this are hindering you, so you must tell how it was, you cannot tolerate this. He sat down—and again, no reaction, they were silent. Then he stood up, looked around the hall, waved his finger around, and pointed at a very, very young girl, my friends sister, Yulia Oleksiivna Novitska. This little girl stood up and said that she had finished ten grades last year and was now working as a team leader. This greatly pleased Rusanov, he made sure she knew me. She confirmed that she did. Then he asked her to tell everything she knew about me.

But I missed something. After Rusanov, the secretary of the party organization, Kalen Ivanovych Parubchenko, the head of the village council, Danylo Ivanovych Omelchenko, and then the same Petro Oleksiyovych Ishchuk began to speak. After that, three or four other men spoke, and Rusanov stopped the speeches. He stood up and said, I see that this is all the village activists speaking, and if even half of what theyve said is true, then Polishchuk needs to be isolated from you. But will anyone say anything different? And so he began to ask the people. No one responded, and so he pointed his finger at this Novitska, and she stood up and said that she had finished 10 grades, worked as a team leader, and that she didnt know anything of the sort about Mykola Kindratovych Polishchuk that these people were saying. He told her to sit down.

Then a little woman, older than me, Nina Kimnatska, jumped up. She was practically my neighbor, across the road and two gardens over. There was a parallel road on the other side, and our windows faced each other. This woman grew up in terrible poverty, in patched-up shirts and patched-up skirts she grew up, hungry. She didnt marry after the war, and she had a child out of wedlock. Whenever we had to be together somewhere at work, whether by the chaff cutter or some other group work, and there was a pause, the boys were always teasing the girls with jokes, but I was afraid to say even a careless word in her direction, because this woman had been so wronged by fate. And this Nina, with her shining eyes, looks at Rusanov and says, Why are you coddling him? His father was like that—and so is he. Id pack him off myself to God knows where.

After her, her friend, also two years older than me, jumped up. This one married a war veteran. Her father, during collectivization, was for some time either the head of the village council or the secretary of the party organization, but he was a very, very cruel man—the peasants who didnt want to join the collective farm were summoned to headquarters at night. Not only did they beat them, but this Fedir... what was his surname, her mothers poker... Shynkaruk. Fedir Shynkaruk. He had spent some time in a tsarist prison and had contracted tuberculosis there. So after torturing those men who didnt want to join the collective farm, he would grab them by the nose and beard and spit in their mouths to infect them with tuberculosis too. So, his daughter, Vira Fedorivna Ivchenko, also jumped up after Kimnatska and also said that Mykola Kindratovych Polishchuk is a very bad man: hes lazy, he doesnt want to work on the collective farm, if he did even a hundredth of what I do, life on the collective farm would be very good. This was at a time when I, after my accident, couldnt meet the required minimum of workday units on jobs that exceeded my physical capabilities. And she was such a great shock-worker that they wanted to make her a Hero of Socialist Labor. So, besides the beets grown by her team, the women who worked in animal husbandry—in the cowsheds, pigsties, poultry farms—also had sugar beets planted, and these women worked on those beets separately, and it wasnt recorded for them, because they earned their pay separately—one with milk, another with pigs—but it was recorded for Vira Fedorivna Ivchenko. But even that amount of beets wasnt enough, they didnt make her a hero. But she was a very generous woman—she was always traveling to congresses, always a part of these delegations.

After this, Rusanov addresses the collective farmers: “So, maybe we should give Polishchuk the floor—let him have a say too?” Here, there was a loud, united murmur: “Let him speak, let him speak!” He gave me the floor: “Tell us, how do you intend to behave in the future?” I stood up and began to refute why Parubchenko was saying such things, why Omelchenko was saying such things, why Ishchuk was saying such things. Rusanov interrupted me: No, no, no, thats not what the collective farmers are expecting from you! And I asked him, “And what are the collective farmers expecting from me? I havent heard anything from them that they expect from me. If the village activists and the Kyiv Oblast Prosecutors Office expect me to repent, and to repent only because such respected people are accusing me, then I do not accept such an accusation. Even if Rusanov himself accuses me of being a criminal, I will not admit to these crimes until it is proven to me in a convincing manner that I have committed this or that specific crime.

And on that note, this meeting of the collective farm board ended. When all the people had left the hall, Rusanov called me into the collective farm chairmans office and said this: “You see that you have no friends here? You see.” I answered him that I know all these people, I delivered the mail and I know everyone from the oldest to the babies in their cradles. “So heres my advice to you: get out of here. Theyll give you good papers—just get out of here.” I answered him that I didnt want to leave here, because I had already built a house, I already had five beehives, I was already planning to live here. He countered: You will have no life here—and your house will be gone, and you will have nothing. You get out of here.

I didnt listen to him. I endured another year on the collective farm, and then they finally convinced me that they would imprison me for parasitism. Imprison me. And so, in 1964, I left for Bila Tserkva. Initially, they hired me at the 34th Construction Administration as a 2nd-grade carpenter with the condition that they would make me a foreman in the spring. But since that didnt happen, I quit and went through many, many construction organizations. I worked as a foreman at the construction administration of the brick factory for a little over a month, I think. There, they started demanding that I pad the books—so I quit. I thought, I dont have experience with that yet, its too soon. Then I joined SPMK-5—it was a construction administration that dealt with underground utilities and landscaping on the right bank of Kyiv Oblast.

V.O.: What is SPMK? What does that acronym stand for?

M.P.: Specialized Construction and Installation Administration-5. I also remember the management then Serhii Kysylenko was the head, and Hryhorii Dmytrovych Kushnirenko was the chief engineer. They hired me for 100 rubles and sent me to the Tetiiv airport. They sent me there because all the money from the budget had already been taken, but the work was far from started. They didnt allow me to issue work orders or sign transport reports—I wasnt allowed to handle that paperwork. There was a local young man from Tetiiv, he only had a 10th-grade education, but because he was a local, it was much easier for him to go to the motor pool for trucks. They gave me only the technical work. There were two runways—one was 750 meters, and the other 350 meters, mutually perpendicular. A small AN-2 plane flew in there twice a day. And in one month, I leveled both of those runways. I divided the whole field into 20-meter squares, put in stakes, and on each stake, I noted that here you need to remove 10 cm, and next to that stake you need to add 5 cm—I wrote all this down in a separate notebook. A month later, for this work, they gave me a 15-ruble raise and transferred me to another site.

The other site—that was already Myronivka, Bohuslav, Kaharlyk. I had already been in these places. But my partner, Mykola Patsiuk, was severely punished by a bulldozer operator. They had a habit: every foreman felt like a little lord, that he would just sign and stamp the paper, while the mechanics themselves filled out the forms. So this Mykola Sydorets, who worked on the bulldozer, had done something like 50 cubic meters of earthwork, but he was always supposedly making repairs. I gave Patsiuk a note, and based on my note, Patsiuk signed his work report, signed it, stamped it, but Mykola Sydorets left a space, added two zeros, for five thousand, and wrote out in words: Five thousand cubic meters over a distance of one hundred meters. And in this way, he punished this Mykola Patsiuk. He came running to me in tears: “What should I do? I wont work this off in half a year! My salary is what it is, and now this, and my reputation!” I told him, “Here’s my diary, what I recorded.” When he saw it, he exclaimed, “This has saved me!” So they punished that guy, and as for me, I was moved around: Snytynka, Myronivka, I was constantly going around these places.

But in Myronivka, I got into a big fight with the site supervisor, my direct boss. By education, he was a mechanic and he really, really loved to cheat. Now they say hes working at the Bila Tserkva prison colony. I was making efforts to build according to the project plans, while he was doing whatever he needed to get his completion reports signed, to be able to close out the work orders. The head of the collective farm in Myronivka at that time was a Hero of Socialist Labor, Buznytskyi. Buznytskyi chose his staff to be more or less competent in certain things. People from his farm even went on excursions to the United States of America. So, there was a technical supervisor, Robakovskyi, supposedly with great experience, and this Robakovskyi wrote on the project plans that I should do not as specified, but the opposite—that the roads there should not be excavated, through which water was supposed to drain, but that instead of an excavation, I should build an embankment. I did not agree to this. The site supervisor wrote me a note: only this way. Just then, the chief engineer, Hryhorii Dmytrovych Kushnirenko, arrived. I showed it to him and said, Hryhorii Dmytrovych, how can I do this? Kushnirenko crossed that out and wrote: according to the project. I had just started to do so when Kushnirenko left, and that Ivan Yashchuk came running, throwing his hat on the ground: let me write it for you. He wrote again: in a crescent-shaped profile, just so and so—as Robakovskyi had written. I took this project, went to Bila Tserkva, and gave it to Kushnirenko: Hryhorii Dmytrovych, excuse me, but I cant work like this—its like Im harnessed by Jewish coachmen: theyre pulling on both reins, whipping me, and shouting gee and haw at the same time. I dont understand this. And I immediately submitted my resignation.

Then I went to work on the construction of the tire plant, at Administration No. 1. They also hired me as a foreman for 100 rubles, and just a couple of days later they showed me an order stating that all falsified reports would be fully reimbursed at my expense. Two young guys, one of whom is now my neighbor, living on the fourth floor above me, were punished, one for a hundred rubles, and the other for one hundred and four—for falsifying reports. The head of the administration, Cherniavskyi, was walking by and saw that the bulldozers and cranes were idle, the month had ended, and here were paid reports for the work of these machines. So these young foremen were punished for padding the books, and I was warned. Well, since I was warned, I stuck strictly to the letter of the law. But its impossible to work like that—constant, constant, constant accusations from all sides. So I also drove the head of the administration to the brink, just like I drove Batmanov in Makiivka… This head, Cherniavskyi, forced me: that bulldozer is working, write him down for half a day, and let him drag the boiler with molten tar over here, so they can glue the roof up here. I did so. I did it twice and got into a fight again, and I quit that job. They punished me—transferred me to be a leader of a concrete workers brigade. Because of this, I submitted my resignation.

A month later, I found a job in a design organization—there was an organization of the 5th Kyiv Trust for the organization of construction technology. The head of that group was a Jewish man, Oleksandr Malin, Ive already forgotten his patronymic, we called him Sasha. The second chief project engineer was Stanislav Oleksiyovych Kobeliev, a Russian, and there were other senior engineers there. By the way, the current mayor of Bila Tserkva, Hennadiy Volodymyrovych Shulipa, was there. (Hennadiy Volodymyrovych Shulipa is a hereditary opportunist. In the phony , he was a “comrade” of the workers and peasants, a “servant of the people,” a “proletarian.” One of his ancestors had the Ukrainian surname Shulika, but Hennadiy Volodymyrovychs ancestor didnt defend his name, which was distorted by the Muscovites, so he became Shulipa. When the “power of the working people” decided to its mask of verbiage, he immediately became a master in Bila Tserkva, and perhaps the richest one! No wonder he used to enter the offices of “comrades” with his own opinion, and came out with the opinion of the “comrade”… – Note by M. Polishchuk). They also hired me for one hundred rubles, but there they immediately put me on the waiting list for an apartment. A few months later, when the organizations that didnt want to hire me before started trying to poach me—they were already offering me a salary 20 rubles higher, just come and work for us. But I said I couldnt, because they put me on the waiting list for an apartment here—I needed an apartment, I was already, oh my, 37 years old.

V.O.: And where were you living in the meantime—in a dormitory or what?