An Interview with Yaroslav GEVRYCH

(Corrections by Y. Gevrych on 10/25/2009 entered on 11/7-8/2009)

V. Ovsienko: December 24, 2007, at the commemoration of the seventieth anniversary of the birth of Viacheslav Chornovil, in Kyiv, at the Viacheslav Chornovil Museum, we are speaking with Mr. Yaroslav Gevrych. Recorded by Vasyl Ovsienko.

Y. Gevrych: I was born on November 28, 1937, in the village of Ostap’ie, now in the Pidvolochysk Raion of Ternopil Oblast, into the family of a Greek Catholic priest. I received my primary education at the local school in my native village. Due to the arrest of my father, who categorically refused to renounce his paternal faith and convert to Muscovite-KGB Orthodoxy, I was forced to survive on the kindness of good people. My mother, Yelyzaveta Rachkovska, despite having a university education, being a specialist in Greek and Latin, and fluent in six languages, was not allowed to work as a teacher even in primary school. But, despite the unfavorable living conditions, with God's help, all five children—three sisters and two brothers—managed to obtain higher education through their own efforts.

After finishing secondary school in 1954, I enrolled in the Stanislaviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk) two-year technical college, where I received a secondary technical education with a specialty as a mechanic for the repair and operation of construction machinery, and I got a job in the garage of the Kosiv forestry enterprise. In 1957, I was drafted and served three years of military duty.

After being demobilized in 1960, I enrolled in the Kyiv Medical Institute in the dentistry faculty. During my student years, I was a co-organizer of the institute's bandura choir, participated in the work of the Club of Creative Youth of Kyiv, and organized Christmas carolers. We would announce in advance whose home we were going to carol at. We went to the professors Kolomyichenko, Mykhailo Kharytonovych, I believe his name was. We went to his place first. There we found two women—evidently his wife and another one. We sang carols for them, and the women started to cry. They said: "My God, my God, when was the last time we were able to hear Christmas carols." Then the professor said: "Go visit my brother across the way." I don't know his name; he was a professor in the ENT department—otolaryngologist, ear-nose-throat, I think that's right. He himself couldn't hear well, so he put on his hearing aid, listened, and then pulled out a hundred rubles and gave it to us. He got into trouble for that later. The KGB mentioned that money to me, so I immediately told my colleagues: "Go and take that money back." But, apparently, they didn't, or maybe they did…

While still students, during the summer vacation of 1964, we gathered a fine group of our own—youth from Kyiv and Lviv—and went to the Carpathians. We knew there was a lake called Lebedyn above the village of Sheshory. All sorts of legends were told about that lake, and we decided to see what kind of lake it was. When we arrived in the village, not knowing where the lake was located, we went to the first house we came across. It turned out to be the home of the village council chairman. We said that we wanted to see the lake, and the host, that is, the chairman of the village council, Volodymyr Mykhailiuk, said: "Myroska, why don't you take these gentlemen up the mountain and show them." The lake was somewhere in the mountains. We went there and came back. And that Volodymyr Mykhailiuk was just harvesting honey; he treated us to some of that honey, and we got to talking. He said: "I have a small museum at the village council." Let's go and have a look—it's interesting to see. We went there, and I saw a mound of earth. I thought, how should I ask him about it, I don't know what kind of person he is, maybe even a communist, you know. I said to him delicately: "They used to build mounds for the fighters for Ukraine's freedom. Is this not one of those mounds?" He said: "No, this one is in memory of Shevchenko, but over there, further on, there is such a mound." There were two mounds in the village. This village has always been very active. By the way, there is now a monument to Chornovil, and to Ivan Franko, and a monument to Shevchenko. I asked: "And where is the monument?" He said: "During the war, Hungarian military units came through and demolished it." And he added: "I have fragments of that monument in the cellar under the village council." – "Well, show us." He brought them out. They were made of sandstone, very primitive work. I said: "You know, Mr. Mykhailiuk, I have an acquaintance—because I often visited Ivan Makarovych Honchar. – I have an acquaintance—an outstanding Ukrainian patriot. Perhaps we could turn to him to restore that monument?" He said: "Well, we've already tried, but here the party's district committee, the KGB—it's all forbidden."

I returned to Kyiv, went to Ivan Makarovych, and he said to me: "My dear boy, come to my place on Saturday. On Saturday, the architect Hryhoriy Kovbasa will come to us, and we will discuss this matter." I came to him on Saturday, and Kovbasa also came, and I explained the situation, that something needed to be done. Kovbasa said: "We need to make a project plan, but based on what?" From memory, I drew a sketch. From that sketch—and he worked at 'Ukrdiproproekt'—he made a proper construction plan on tracing paper. It was signed: "Honored Artist Ivan Honchar and Architect Hryhoriy Kovbasa." I delivered those plans to Kosiv, Mykhailiuk went to the district party committee, and there they saw that he was an honored artist—but they didn't notice that there was no official seal. Well, alright, if Kyiv allows it, then build the monument. Ivan Makarovych made the monument himself, but he said: "Just pay for the technical work of the people who will cast it." Kovbasa, thankfully, didn't want anything at all. A few months later, the monument was ready. Two young men from the village of Sheshory came with a truck, took the bust, and they were supposed to build up the mound, restore it to how it was before, and make a pedestal.

The village got very actively involved in this work. They had a good amateur performance group, they traveled to villages, earned a little money, so they were able to organize it. In short, it was planned to unveil the monument in August 1965. And then this situation arose. First, Mykhailiuk said that it should be a holiday for the whole mountain region. A huge number of people were invited. But a day or so before the unveiling of the monument, which was already standing, covered with a suitable cloth, they came to me and said: "Listen, the KGB has detained Mykhailiuk." What to do?

The next day we went to the bus station to take a bus to the place where the unveiling was to take place. We arrived—the buses to Sheshory were cancelled. Just like it always happens here. But I had a good acquaintance there, a dispatcher, a man from a good family, and he gave us a small bus for the elderly. And we took a shorter path through the mountains, it wasn't that far. What they did was set up a picket on the main road, because there is a turnoff for Sheshory. At that turnoff, they set up a police picket and turned back all the buses that were going there. And they turned back, as I was told, about 200 buses. At that time, in the sixties, that was a sensation. But many people came on foot. And the monument is quite close to the road. So they decided to send a truck, the truck drove back and forth to disperse the people. Well, the people got fed up with it, they threw stones at the truck, broke the windows, and the truck drove away somewhere. (Lyubomyr Hrabets says, not very confidently, that this was on the Feast of the Transfiguration, August 19. – V.O.).

The scenes were very beautiful, well, the stages were wonderfully decorated with Hutsul carpets, embroideries. There were two stages—one near the monument, the other lower, because there is a small valley and a river there. But no one was officially allowing the monument to be unveiled. In that valley, there is a radio relay station that has a direct link to Kyiv via the KGB line. Tetyana Ivanivna Tsymbal was there, she was a very good declaimer. Tetyana Tsymbal came to Kosiv at my invitation with her daughter Viktoria. Tetyana worked, if I'm not mistaken, at ‘Ukrkontsert’—there was such an organization. She recited poems and said: "Oh, over there in the forest, the ‘Homin’ choir of Lviv University is preparing." But for some reason, ‘Homin’ never performed. They recited some poems, sang a little, and suddenly—Chornovil appeared, and so rapidly—ta-ta-ta-ta-ta-ta-ta, he said his piece, that here we have the authorities, they should understand us. And he disappeared. The secretary of the raikom Komsomol approached me and asked: "Listen, who was that speaking?" I said: "I don't know, how would I know? Ask him."

V. Ovsienko: But did you really know?

Y. Gevrych: Of course, I knew. In short, the authorities set up a police picket, a tent, and the policemen guarded this monument for a whole week. But the monument was already standing, there was no way to dismantle it. So the authorities decided to unveil this monument the following week anyway. Ah, I must go back. A man from England was traveling in a taxi, he reached the picket, and they wouldn't let him through. He showed his English passport, saying: "I am from England." – "Ah, please, proceed." He said: "No, not now. In our capitalist country, no one would allow themselves to do what you are doing here." In short, by evening, Radio Liberty had already broadcast the information. It's clear that this also had an effect, because the following week, they gathered amateur collectives, hung some carpet that they brought from the raikom, a portrait of Lenin on one stage, on the other stage… So I say—there is a Polish saying: “What does gingerbread have to do with a windmill, or a tailcoat with a vest?” `P’yernik` is a comforter cover. A tailcoat is long, and a vest is short. It was clear that everything was done in the Soviet style: they read out how many eggs from a laying hen, how many piglets from a sow… It was all staged, it was all done in a formulaic way.

V. Ovsienko: Were you at this second unveiling as well?

Y. Gevrych: Yes, I was at the second unveiling, because it was interesting. People still came, the authorities tried… They were singing hymns. Well, I didn't even know those people, maybe they knew me a little because I was busy with that monument. The anthem of the Soviet Union played, and I stood there in my hat, a beret. They put their hands to their heads, but didn't take off their hats, looking at me.

All this took place somewhere around August 21, 1965. I already had to go back to my studies at the Kyiv Medical Institute. On August 28, I was taking a bus to Ivano-Frankivsk, to then fly or take a train to Kyiv. In the settlement of Tysmenytsia, at a turn, the bus was stopped, and KGB Captain Grigoriev, as he introduced himself, took me off the bus. Well, if they take you off, they take you off. They took me off the bus and in the car they told me: “We’ve been observing you for a long time.” They searched me. I didn't have anything special on me, except a couple of booklets of “The Derivation of the Rights of Ukraine,” which you can now buy everywhere, some feuilleton about Khrushchev, and there were also some film negatives. I spent the night in a cell, and the next day I was flown to the central prison in Kyiv, to Volodymyrska, 33, I think. Of course, the investigation began, the twisting and turning.

I was detained on August 28, 1965. The next morning I was already sent on a regular flight to Kyiv. I'll tell you, not only I, but probably many people were not ready for that. We simply didn't know how to behave. The investigation lasted seven months. They twisted things, and I twisted some things myself, so much so that the investigator Koval said he was dropping my case. They took me to a psychiatric hospital for some examinations.

V. Ovsienko: How long did that examination last?

Y. Gevrych: Very briefly. They brought me in, he talked to me for a bit and said that I was not mentally ill, not legally insane. That is, I was subject to trial, I could be tried. It dragged on until March, that makes seven months in a solitary cell. It's true, they planted 'nasedki' (ducks) with me… I was a fool, how would I have known… They put some supposed poet from the Vinnytsia region, from Pohrebyshche—I remembered that—in with me. And I knew many poems by Symonenko, Drach, and Vinhranovskyi by heart. Well, I recited those poems to him. It was naive… Then they took him away, then they gave me some other old man, but he didn't stay with me for long, he spent one night and then disappeared, he wasn't there anymore, but I was mostly alone in the cell.

The investigation was conducted only during the day; they never called me in at night. They used to practice that. My father told me, when he was in prison, they would call him in at night and watch him. That didn't happen to me. I will say that it was conducted in a relatively civilized manner. But, for example, in Stanislav, Panas Zalyvakha was even beaten, they threatened him.

V. Ovsienko: Mykhailo Osadchy was beaten by Major Halskyi in Lviv.

Y. Gevrych: In Lviv, yes.

V. Ovsienko: You said the investigator was Koval?

Y. Gevrych: Koval, yes. For some reason, they brought me together with another one, with Petro Morhun. I had photocopies made at Morhun's. They busted Morhun first. How—I don't know, but they got to me based on some information. They arrested me on the road. For some reason, they wanted to include me in that group—Oles Martynenko, Ivan Rusyn, Yevheniia Kuznetsova from Kyiv. They thought it was all one group. But I didn't even know those people.

The trial was on March 9, 1966. It was at the regional court, which is near the monument to Bohdan Khmelnytsky. I was tried there. A lot of people came, I'll tell you, and it was clear that these people were outraged. Chornovil was actively involved in this. The trial lasted for two days. Interestingly, on the first day, all the guards were Ukrainian—the officer was Ukrainian, the guys were Ukrainian. During a recess, that officer went up to the judge and said: "What are you trying him for? He's not guilty of anything." The next day, there were already black-uniformed guards, they didn't understand anything. Because that could have an influence on the soldiers...

They gave me five years. Mykola Plakhotniuk was very active in finding me a lawyer. And he found one. She said: "Based on Leninist morality, we must understand, we must be humane"—such general phrases. Who's going to pay attention to that? The main thing there was the prosecutor, saliva was flying from his mouth. They gave me five years and sent me back to my cell. The trial, of course, was closed.

V. Ovsienko: So you were the only one in the case?

Y. Gevrych: I was alone.

V. Ovsienko: And how did Morhun drop out—was he separated into another case?

Y. Gevrych: He wasn't separated. He, poor thing, has no arm…

V. Ovsienko: So what was his fate—was he tried or not?

Y. Gevrych: No, just the time he served, that was it.

V. Ovsienko: Ah, released from the courtroom?

Y. Gevrych: He wasn't even tried. I don't know how, but they released him. He lives here on Lvivska Square in Kyiv. And I'm glad they didn't try him—a poor cripple like that, you know. It's true, they kicked him out of the party. Maybe they didn't try him so as not to compromise the party. He's an artist, he has no arm, but he painted with his other hand. He worked at the Franko Theater, did scenery and other things.

After some time, I don't remember when, that lawyer filed an appeal and they, as they say, knocked my sentence down to three years.

V. Ovsienko: To "knock it down"—like sliding the beads off an abacus.

Y. Gevrych: Yes, they knocked it down. I was lucky that I was traveling in a transport to Mordovia and met some Banderite guys. They were from Western Ukraine. They were being taken to Volyn, because Oliinyk was being tried.

V. Ovsienko: That was Anton Oliinyk and Roman Semeniuk.

Y. Gevrych: Yes, Anton Oliinyk and Semeniuk were tried then. Anton had already escaped once before. They told him that this time he wouldn't get out alive. He was caught in such a foolish way, because he had a route planned to cross the border, everything was worked out for him. Well, I don't know, that's how it happened. And these were the guys who were taken as witnesses. For some reason, they took those three guys to Kyiv, and I was traveling with them.

V. Ovsienko: In addition to the escape, that insurgent Oliinyk was accused of "newly discovered circumstances."

Y. Gevrych: They pinned "cow bones" on him, as they say, because they really had nothing... He was a propagandist, and it can be assumed that he did not participate in planned combat actions, much less punitive ones. By the way, his archive was lost. A whole suitcase of his archive was buried somewhere in the Mordovian camps—and no one ever found it. He was a very wise man.

I was with those witnesses—Vasyl Pidhorodetskyi, Viktor Solodkyi, and one other, I don't remember his name—on the transport. The third one was younger, from that generation of the fifties. I made contact with them, we arrived at the camp together, and they had already informed me on how to behave.

V. Ovsienko: Which camp were you talking about?

Y. Gevrych: In Mordovia, number eleven, posyolok Potma. But I'll tell you, when I arrived at the camp, I felt a kind of relative freedom.

V. Ovsienko: Yes, yes, that's right.

Y. Gevrych: Seriously. You can walk around, you can talk, you can argue…

V. Ovsienko: After a solitary cell, there is such a psychological shift.

Y. Gevrych: And I even walked into the camp like this, I had sandals, a green quilted jacket, not a prison-issue one, I had some kind of tracksuit. In short, I could dress as I pleased, and I walked around like that for a while, until the head of the regime, Yoffe, caught me…

Some people I remember very little, others I remember... Those Banderite guys immediately took me into their brigade at the woodworking factory, making veneer, which they planed. It was interesting that the Lithuanians were terribly obsessed with meeting quotas, but our brigade working on veneer—we were like: we'd finish the quota in two hours and then whistle. The quota-setters came, started timing us. They told those Lithuanians that they were doing three quotas, so they made a triple quota the norm, but for us, they decided to raise it by five percent.

Yurko Shukhevych was also in that camp, as was Mykhailo Soroka. By the way, I had a very good relationship with Soroka, we spent very pleasant times together. Prison-style pleasant. Hryts…

V. Ovsienko: Perhaps, Herchak?

Y. Gevrych: No, there were two with the same last name… I forgot the names. There were guys from Volyn, interesting guys.

V. Ovsienko: Maybe Pryshliak?

Y. Gevrych: Ah, Pryshliak, Hryts Pryshliak, Yevhen Pryshliak. There was Stepan Soroka from Volyn, a young lad who was very into archeology.

V. Ovsienko: I knew him later.

Y. Gevrych: I knew him too, he worked a lot with books, a peculiar person, very stubborn and often suffered because of it. By the way, at first, for the political classes, I said I wouldn't go. But he said: "Don't be a fool, you'll sit for a bit, it won't kill you." When I came to the political classes for the second or third time, Soroka—the guy was very bright, well-read, as they say—asked that idiot, the camp commander, some question. Obviously, he was unable to answer and accused Soroka of asking a provocative question: “I'm giving you such and such punishment.” And I stood up and said: "Well, if this is the kind of punishment you get at political classes, then you won't see me here again." I just stood up and left like that: “I will never go to political classes again.” But maybe what saved me was that I was already in my final year of dentistry, and there was a dental office there, but there was no one to work in it. And those camp bitches who wore the armbands saying 'the bitch went out...'"

V. Ovsienko: SVP – 'the bitch went out for a walk' from `sukа vyshla pohuliat' `, ‘Council of Internal Order’ from `sovet vnutrennego poryadka`.

Y. Gevrych: They wrote to the Prosecutor General that "we have a dentist here, our teeth hurt, but they won't let him work." So from time to time they would put me there. So it was—I'd work for a month, the KGB would intervene—and they'd remove me. I already knew that when the camp commander brought his daughter or wife, they were going to get rid of me.

I did various jobs there, that's not so important. Then one day they transfer me to the hospital of Dubrovlag, in Barashevo. They bring me there, I don't know why. It turns out there's a dental prosthetic lab there—it's propped up with poles, tilted. There are two guys there, one from Zolochiv, the other some Jewish fellow. "Oh, it's good you've come, we'll work here." – "What do you mean," I say, "nobody asked me. How am I supposed to understand this?" I immediately rebelled. The head of the hospital, Shimkanis, summons me. She had some medal on her chest, hanging upside down, I remember… She called me in and said: "You will work as a dentist, but we will register you as an orderly." I said: "Right, as an orderly, and some freelance doctor who never shows his face here will get the money." – "Well, you know, this and that." I said: "No, I don't agree to such an arrangement." Then I heard the medical unit chief, Zborovska, who was sitting there, say: "And no one will ask you." I said: "Right. If it's necessary to dig trenches, they won't ask me, but whether I want to be a doctor or not is my personal business, goodbye." I stood up and left. I went to the guys, they said: "Don't be a fool. What's wrong with being here, in the hospital, everyone comes here, there are all sorts of connections here."

I stayed. There was a paramedic named Yevdokimov, later he was at the nineteenth camp. He introduced me to Volodymyr Horbovyi—he was in the foreign prisoners' camp then. The Czechs handed him over to the Poles, the Poles to the Soviets—that's how he was imprisoned. Horbovyi came to my office, we had a little chat. The next day they were stringing some wires in there. I thought they wanted to bug the conversations. He came to me again. The head of the squad for that zone came in and said: "Why aren't you at the political classes?" I said: "I don't go to your political classes." – "And what are you doing here?"—he said to Horbovyi. I said: "I'm treating his teeth." He got angry and left. The next day they put me on a transport and sent me to the 17th… I don't remember what that settlement is called…

I managed to outsmart them there again. I had chrome-leather boots… I didn't pick fights with those guards. A guard is just a man on duty, that's all. I got there, picked up my things. And Shukhevych had already found me some prison-issue boots, he said: "Take these boots, because they won't let you keep your own." No, it wasn't Shukhevych, it was someone else, I don't remember who. But in the meantime at the checkpoint: "And what's this?" – "Nothing," I say, "I'll take them to the storeroom." I didn't take them to the storeroom, I still walked around in those boots. (This camp was a kind of punishment camp. The territory was small: about 60x40 meters, 4 buildings, 2 of which were barracks. There were few prisoners, if I'm not mistaken, about 80 people. The camp commander called me in and boasted: "Here I have every little man in the palm of my hand." Inmates there included Mykhailo Soroka, Hryts Pryshliak, O. Polevyi, Stepan Soroka, Father Denys Lukashevych, Yuriy Shukhevych, Vasyl Pirus, I. Ilkiv, Dmytro Verkholiak, Bohdan Hermaniuk, Koshelyk, Daniel, Yevdokimov, Sinyavsky, and others.)

I was temporarily assigned to the medical unit there as a dentist, and those ‘dukharyky,’ the guards, would come to drink valerian. A little shot glass of valerian, thirty grams, bottoms up and that was it. One time they came, and Klara—there was a paramedic there—brought belladonna instead of valerian. And I didn't look, I gave them belladonna. An hour later, they were all like: "Water, water." Severe dehydration sets in, you can go blind. "What did you give us?" I look—belladonna! I gave them glucose, glucose, glucose… And they kept coming to me, but they would say: "Just don't make a mistake." They were Mordvins. Good guys, by the way. When my brother came for a visit, one of them said: "Shove the package in the stove there. And I'll throw it to you through the window later." He meant food. They were good guys like that. There were all kinds. One was very nasty, but two were normal guys.

Oh, and I had another interesting incident in the camp. They were sending Valentyn Moroz to prison. Everyone was at work in the workshop. There was a sewing workshop there. I was in the medical unit. And I saw through the window that the head of the regime was leading Moroz. He took him to the kaptyorka (storeroom), they took his things, and they came to the barracks. The door was like this, Moroz stood between the beds facing me, and the head of the regime had his back to me. And Moroz was rummaging in his backpack, suddenly grabbed something and threw it to me. I caught it in mid-air—and into the medical unit. I had a very good stash in the medical unit, I had a great hiding place. I was young, I dashed out instantly. I had a crack behind the door, I hid it behind the door's paneling. The head of the regime ran in there: "What did he give you?" I said: "Nothing." – "What do you mean nothing, I saw it." I said: "Search, if you find it, it's yours." He tore the office apart, didn't find anything. He wanted to get revenge later, when I was leaving the camp.

When I was being released from the camp, the guys saw me off with honor, a bucket of coffee was brewed. It was on August 28, right when the Soviets were conquering Czechia.

V. Ovsienko: 1968?

Y. Gevrych: Yes. The guys were walking me to the gate and not saying anything, but as I was walking to the checkpoint, they said: "We thought they would detain you." The political situation, you understand… My father came for me. First, the squad leader, Repchynskyi, came; he was a handsome fellow, from Dnipropetrovsk. He was even a bit nationally conscious, because I know he organized a Shevchenko evening in the settlement. So there was something in his head, he was even accused of something. He loved to listen to what the guys told him about the UPA. He listened to everything. They told him: "Listen, you're such a man, you could be a captain in the Ukrainian army, but what are you?" He took it all calmly, and I think he never used those moments anywhere. So, he came when I was being released and said: "Well, let's go, I have to check you." And I said: "What am I, a pig? There are people with me, drinking coffee." He waited. And Zalyvakha had entrusted me with some of his things. He made ex-libris on linoleum. What was I to do—I had it on me, it was now or never, you understand. He was like: “Okay, pull it out.” He looked through these things and covered them with his handkerchief. Suddenly—the head of the regime came running. "Well, how is it?" He said: "I've already checked his things." – "Well then, get undressed." His function was to carefully check every seam of the camp clothing. He didn't know I wasn't going to travel in that clothing, and he was very meticulously searching for something, obviously for Moroz's materials. And my father came to get me, brought me an embroidered shirt, a suit, everything as it should be. The guys there had sewn me a Mazepynka cap, so I put it on. The guy was stunned, and Repchynskyi just laughed.

But a tail followed us immediately, wherever we stepped. That was right when they were protesting at Lobnoye Mesto in Moscow. Daniel's wife...

V. Ovsienko: The “Demonstration of the Seven.”

Y. Gevrych: I was imprisoned with Daniel and Sinyavsky. In Moscow, I went to the Daniel family's place; she had already been arrested, only the son was there. But the tail followed us the whole time, it was especially noticeable at the train station.

V. Ovsienko: Daniel's wife, Larisa Bogoraz, right?

Y. Gevrych: Yes. After that, my father and I went to Kyiv. And in Kyiv, a tail was on us right away. I knew Kyiv quite well, and over here, where the ambulance station is, we went into one entrance and came out another—and he lost us. We went to Svitlychnyi's place…

That's all nonsense—to be in prison, not to be… But when you get out, that's when you feel who you are. In the camp, you feel like a human being, you could say, but out here—the problem of getting registered. Wherever you turn, you start, as they say, to assert your rights, and right away they say: "What, you want to go back again?" That's it, bite your tongue. I was running around, running around in Ukraine, in Kosiv, in Kyiv… Maybe I'm talking for too long?

V. Ovsienko: No, we have enough time.

Y. Gevrych: Nowhere would they register me. I got in touch with Lyuda Alexeyeva from Moscow. She later worked for 'Svoboda,' a very active woman. And there was this Grinberg, supposedly a dentist. Later it turned out he was a KGB man. He supposedly helped me, and Lyuda, Grinberg, and I went to Roslavl near Smolensk. That Venya went into the police station there, came out—and they registered me in Roslavl. Now one can imagine on what basis I was registered. Obviously, they wanted to recruit that Venya into the dissident group as an agent. They found some old lady, and I was registered at her place. I went to Ukraine, but no one would reinstate me at the institute. I went to Kozyrenko, the deputy minister. He gave me an official answer: "We cannot reinstate you." I went to the dean, M. Danylevskyi, to Kyselova, who was the secretary of the party bureau. She attacked me! I went to the rector, Professor Milko; he was a radiologist himself. Well, he was a sly old fox. He received me calmly, listened to me and said: "You know what I'll tell you? You should probably transfer to another institute." He started like that, but in any case, he spoke to me somehow, and for that, I am grateful to him. One might say, the only one in Kyiv. And then that Alexeyeva—they had channels, and through the USSR Ministry of Health, they had me reinstated at the Smolensk Medical Institute. I went there, the rector was Starikov. I already had the paper allowing me to study. He says: "Well, what, served your time?" – "Served my time." – "Well, look, if you get caught a second time, they'll let you rot. I used to shoot people like you when I was seventeen." It was unpleasant, but what could you do, you have to study. I returned to Ukraine, got married. My wife worked as a doctor in Turka, in the Lviv region.

V. Ovsienko: Please name your wife—her name...

Y. Gevrych: Oleksandra Sandurska, Lesia Sandurska. And I went and finished the institute. They sent me to the Penza region. At first, they offered Novosibirsk...

V. Ovsienko: And when did you finish the institute?

Y. Gevrych: In 1970. I said: "I don't want to, I'm married, I have this, that." – "Listen, khokhol, it's warm here, come on over, we have watermelons growing." In the end, you have to decide on something, I'm not going to stand on my principles. Fine, sign me up. But a professor who was the deputy dean told me: "Say one thing, but do what you need to do."

All graduates are given a relocation allowance, but I didn't take it. Because that could be a hook to get you convicted. I didn't take the allowance, I went to the Turka Raion of Lviv Oblast, and in the village of Limna, Stanislav Horlenko, the chief doctor—the only non-communist in the oblast—hired me on his own authority, so to speak. By the way, I was very lucky, because on the day I arrived, Tisnetska, a Jewish woman who was the head of personnel for the oblast health department, came to Turka. And he said to her: "Listen, a doctor came to see me, he graduated from an institute in Russia, and we don't have enough dentists, I would hire him." – "Hire him." And with that backing, he sent me to the village of Limna. I give my passport for registration, and in the evening the secretary comes and says: "Doctor, may a plague take him, you can't be here, you've been convicted, you have a stamp 'Regulation on Passports' in it." He says: "They snarled at me there..." I said: "What do you have to do with it?" In short, I couldn't be there: a border zone. Horlenko, without asking me anything, transferred me to the village of Yasenytsia, which used to be called Yasinka-Masiova, and I worked there for a year. I had big plans there, I decided to improve the health of the children, but in the meantime, a very unpleasant situation arose in the district: the dentists were fighting among themselves over something. Horlenko calls me in and says: "Your wife works for us, and you will work here too." And they immediately made me the district dentist.

Then I had big problems—they didn't register me for two years, I don't know why. It always surprised me and still does—everyone else got registered, but for some reason, they got stuck on me... Why they were stuck on me—I have no idea. There was a chief of police there, Sydir Rushchak. The Banderites had punished someone in his family. Well, they punished him for a reason—he was an informer. They warned him, and then they punished him. He used to tell me: "You, Banderite, go back to where you came from, to your Ternopil region, I have enough of my own here."

But they registered me anyway after two years, and it happened in a very original way. My wife's nurse was the wife of the deputy chief of police for political affairs, I think that's what it was called then. And one day Maria Stepanivna, his wife, said: "He told me that you should come to see him at the police station tomorrow morning." I went, and he said to me: "The chief of police wants to see you, and the head of the KGB will be there." I went there, there was a T-shaped table, the chief of police sat here, they sat me here, and that chief, Antoniuk, sat on the side. By the way, when the chief of police asked me if I knew who was in the office with him, I said I didn't know (though I knew), and he introduced the head of the KGB, Antoniuk, to me. And the head of the KGB said in a hoarse voice: "So, Yaroslav, what family are you from?" Aha! I understood, because Chornovil wrote in ‘Woe from Wit’ that I was from a peasant family. "Aha, so you've read Chornovil!" – "Of course!" he says. I said: "You know, forbidden fruit is always tempting to try"—well, what was I going to do, play the fool with him. And he said: "So what?" I said: "Nothing, I tried it, it didn't choke me." He laughed: "Heh-heh-heh, register him." And that was the whole conversation, although Antoniuk never summoned me. "Register him." And that's it. That police chief was like: "What, how?!" – "I said so!" – and that was it. The police chief angrily said: "Go get form number 1, fill it out," – and they finally registered me in Turka, after two years.

I worked in Turka. Then the so-called perestroika began. The first thing I did was organize a carol contest for the whole district. We set up two large trucks, opened the sides—this was on the square, in the center of the town... I'll tell you, it was such a festival that I'll remember it for the rest of my life, and I'll also remember it because no one was drunk. Twenty-five groups, they stood there all day, and I had come from Kyiv (I went to Kyiv for some reason, I don't remember what business I had in Kyiv) early in the morning to Turka and stood without a hat on that platform, because I was leading the whole thing. That happened just once, and after that, you can sing carols and stage nativity plays as much as you want—but that's not there anymore.

V. Ovsienko: The impression is not the same anymore.

Y. Gevrych: There were three nativity plays in Turka, even though there was this Brych, the district committee secretary—a complete scoundrel, he would break them up—it was terrible what they were doing. There were three nativity plays, and now last year there wasn't a single one, can you imagine? Only church brotherhoods sing carols now. Everything has terribly declined.

And then they started to create the Ukrainian Language Society. The secretary of the district party committee, Henadiy Brych, said that he would sooner have a brown bear society than a Ukrainian Language Society, but a writer came, his name starts with "I," tell me...

V. Ovsienko: Roman Ivanychuk?

Y. Gevrych: Ivanychuk. I don't know why, I'm already losing my memory a lot. I've forgotten a lot of things. I remember my childhood very well, but other things I'm already forgetting. Ivanychuk came, I gave a speech there, another doctor from the village of Borynia named Huchok gave a speech, and they had no choice—it was the last district without a Society. We decided to create a Society. Ivanychuk proposed me as the head of the Society and I was elected. They rushed to put their own people into the leadership, but they didn't succeed.

And then it went on—they started to organize Rukh. I was the deputy head of Rukh, the deputy head of "Memorial." Then came the preparation for the elections—I was then elected a deputy of the oblast and raion councils, because back then you could be a deputy of two levels of councils.

V. Ovsienko: This was from 1990?

Y. Gevrych: Yes, yes. We conducted educational work. First, we erected a monument to Shevchenko in Turka. That had great significance. We built a monument at the site of the first battles of the USS with the Muscovites between the villages of Botivka (now Verkhnie) and Sianky, conducted the reburial of UPA soldiers in the urban-type settlement of Borynia, in the villages of Yabluniv, Nyzhnie Vysotske, and placed a cross on the site where the bodies of insurgents were brought, forbidding their burial, and wolves and dogs tore at their bodies. It was horrible! We placed a stone cross near Turka, where the Poles tortured captured Galicians who were returning from Zakarpattia after the defeat of Carpathian Ukraine in battles with the Hungarians. In the list of reburials of UPA warriors, I also add the village of Holovske (the hamlet of Kryntiata) and the village of Verkhnie Vysotske. For some reason, in historical materials, the village of Botivka is called Botelka, which is an incorrect name.)

Then we created a KUN cell. For some reason, I always had to be the first, to lead, that's how it turned out… Then we had a KUN cell in almost every village. That had great significance. No matter how you look at it, there are many people who are very hostile to nationalism, but without nationalism, the national idea, excuse me, is dead and ineffective.

I worked for thirty years in Turka. And then circumstances developed in such a way that my daughter left for America. She went to her relatives, met a Ukrainian man there (his father is a former division member), a conscious Ukrainian, he can put more than one Ukrainian here to shame. My daughter got married, returned, finished her studies, then went back to America. After her son was born, someone had to be with the child, so my wife went for six months, and then they called for me. But even in America, as they say, I was not idle, because I joined the "Boikivshchyna" Society. Two years ago, I was elected the head of the "Boikivshchyna" society. I am supposed to be leading it now, but how long I will be there, I don't know.

V. Ovsienko: So you are now moving back to Ukraine, is that right?

Y. Gevrych: I intend to return for good.

Such is my life story.

V. Ovsienko: I just have one question. You said that Valentyn Moroz was tried in the camp. I know that he was tried in the 17th camp—that's Ozerne.

Y. Gevrych: That was Ozerne, Ozerne, it wasn't even the 19th, but the 17th, you see how I've forgotten, so you can correct that there...

V. Ovsienko: I was in both the 17th and the 19th, so I know. That was when Moroz, Mykhailo Horyn, and Mykhailo Masiutko were sent to Vladimir Prison at the same time.

Y. Gevrych: Moroz was a peculiar man…

V. Ovsienko: That is known. Alright, I thank you, you have told your story so well that you didn't even need this cheat sheet of yours, but let me keep it.

Y. Gevrych: You can keep it. If only a copy of the release certificate could be made here.

V. Ovsienko: We'll ask these guys right now, maybe we can get a photocopy.

Characters: 34,520

Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group.

Yaroslav Gevrych in a crown of thorns.

Yaroslav Gevrych, 11th concentration camp, Potma, 1966.

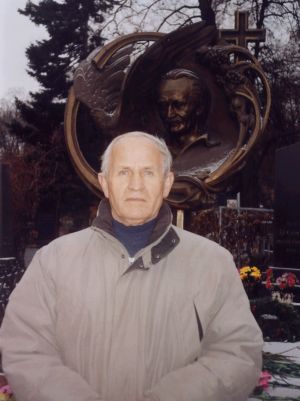

Yaroslav Gevrych at the grave of Viacheslav Chornovil at the Baikovyi Cemetery, 12/24/2007. Photo by V. Ovsienko.