Interview with Balis GAYAUSKAS

by Vakhtang Kipiani

Vilnius, 1995.

B. Gayauskas: We arrived in Kuchino from Mordovia in 1980.

V. Kipiani: So, you were among the first?

B. Gayauskas: Yes, among the first, because they gathered all of us from that special-regime camp in Mordovia and sent everyone to Kuchino. I was among the first.

V. Kipiani: And who were the prisoners you arrived with? What was the transport like? What were the conditions? This is all very interesting.

B. Gayauskas: Well, I can't name everyone off the top of my head right now; there's a list where you can look. I remember Levko Lukyanenko well, because we always had secret dealings together. So, there was Lukyanenko, the Lithuanian Yashkunas, Kuznetsov from the hijackers group, Murzhenko... (Fedorov and Murzhenko were from the hijackers group. And on April 27-28, 1979, Eduard Kuznetsov, as one of five Soviet political prisoners, was exchanged at New York’s Kennedy Airport for two Soviet spies. – V. Ovsienko). It’s hard for me to recall now because some arrived later, and I might mix up the dates. Well, it’s not that important; you can get the list and name them all.

What were the conditions like? The conditions in Mordovia were better. There wasn't as much isolation. It’s clear to me now why they sent us away: because we were writing various appeals, various materials, and secretly sending them abroad. They couldn’t put a stop to it. The materials kept getting out, getting out, getting out, and were published there, so they decided to create such isolation that no one could write or send anything, and that’s why they sent us here. When we were being transported in that prison car, the head of that special-regime camp from Mordovia was escorting us. He said, “You won't be writing here anymore.” We wondered where they were taking us—we didn’t know.

They brought us here, and interestingly, they thought we were bringing something with us. During the intake, they stripped us naked, took all our clothes, the camp uniform, and gave us a completely new one. Our belongings were also set aside, and then they put us in the cells. They later burned our clothes and held our belongings for a very long time. They inspected everything, searched everything, to make sure there wasn't a single scrap of paper. The isolation there was really not like in Mordovia. It was very difficult to write from there, and it turned out I was the only one writing. The first time, Levko and I managed to send something out, but then we were in different cells, and he couldn't do anything; he didn't have the opportunities. I had more opportunities. I described everything and sent it through Moscow. Lithuanian newspapers [abroad] published it under my name.

V. Kipiani: Were these, let's say, about the conditions in the camp, about harassment from the authorities, or were they more profound works?

B. Gayauskas: It was a rather strict regime, isolation, so that we would know less about each other, because one cell could have no contact with another; they never put you in another cell. The regime was just like in a prison—it was difficult to talk to another cell. Well, of course, we did talk; we took risks—if they caught us, it was the punishment cell. The work was set up so that... well, from cell to cell... If two people were in a cell, they also worked in that same cell, with no contact with other cells. We went out for a walk—also just one cell at a time, separately, so that no one saw anyone else. It was a prison regime. It was even worse. Some who came from other prisons said it was better in their prisons. And at first, people tried to get transferred to a prison from our camp—it was freer there. That was quite difficult. The control was very tight. As for food, it wasn't difficult; there wasn't that kind of hunger. You could receive packages—one every six months, if they didn't take away the privilege, but they very often did. (One per year, after half the term was served. – V.O.)

V. Kipiani: Tell me, please, did you personally, for example, have any conflicts with the camp administration, and with whom specifically?

B. Gayauskas: Well, I didn’t have any major conflicts. Sometimes I was in the punishment cells for something, that was normal, I don’t remember now, we didn’t consider it a conflict. If a person was a bit more proud, he was often in there, but that, as they say, was everyday life. I don’t consider it anything special.

V. Kipiani: You don't even know how many days you spent in the punishment cells?

B. Gayauskas: I'd have to think about it. I know the total number of days I spent in the punishment cells—157 days in total. But otherwise, I don’t remember it all; I'd have to count.

V. Kipiani: Besides Levko Lukyanenko, with whom did you have warm relations in the camp? Perhaps you can recall some pleasant moments?

B. Gayauskas: Well, I had pleasant relations with almost everyone. The exceptions, I can say, were my not-so-good relations with Murzhenko and Romashov, but I believe that was a KGB assignment, because I never shared a cell with him, we had no conflicts, I only knew he had been brought here, and he didn't know me.

V. Kipiani: And maybe you could recall the circumstances of that day? Because I've already heard it from third parties, a “broken telephone,” what it was like?

B. Gayauskas: Very simple. Here I have to go back a little. I'll tell you what the KGB man told me: “They will kill you in the camp.”

V. Kipiani: A camp KGB man, right?

B. Gayauskas: A camp KGB man.

V. Kipiani: You don't remember his name?

B. Gayauskas: I don't remember it now, I have it written down somewhere, but everyone who was imprisoned probably knows him—Ovsienko, for example. (In 1985-86, a KGB man by the name of Vasilenkov worked at the special-regime camp VS-389/36. – V.O.). So he told me that. I thought then, my term is ending... Andropov had issued a decree that if a prisoner here misbehaves, they could add three years to a strict-regime sentence, and five years to a special-regime one. (Article 183-3 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR, “Malicious disobedience to the requirements of the administration of a correctional labor institution,” 1983. – V.O.). So I thought that they... Well, of course, I misbehave, I've been in the punishment cell, if necessary, they could just write up a decree and that's it, they'd give me five years, send me to a common-criminal camp, and there it could all be done very easily, murders were not news there. That’s what I thought. I was in the nineteenth cell with Murzhenko, then they moved me to the twentieth—a large cell, and I was alone. A few days later, they transfer Romashov in. He behaves very well with me, normal relations—no smoking, no swearing. A good man, you know. But in other cells, he behaved very badly with the people he was with. And Levko, who was in the cell next to me, asks after a week: “Well, how are you feeling?” I say: “Wonderful.” “How can that be?” [The rest is inaudible, the dictaphone’s power was failing during the recording. The conversation is about the attack by cellmate Boris Romashov, a former criminal, on Gayauskas in work cell No. 15. Romashov struck him from behind on the head with a mechanical screwdriver. When Gayauskas lost consciousness and fell under the worktable, Romashov stabbed him twice in the heart area with the screwdriver blade (fortunately, at an angle) and several more times in other places. In total, Romashov struck Gayauskas 12 times. For this, he served 15 days in the punishment cell. No criminal case was opened. Gayauskas was discharged from the hospital before the 12th day so that his injuries could be recorded as “minor bodily harm.” – V.O.].

If I returned in 1987, then this was probably in 1985, in the summer, I think so. I need to check all this for accuracy; I have some things written down. (The attack by Boris Romashov on Balis Gayauskas was committed on April 17, 1986. – V.O.)

V. Kipiani: Tell me, do you have any records at home, or have you perhaps published them?

B. Gayauskas: No, I haven't published anything yet, but it exists. It was printed back then, abroad too; it became known quite quickly.

V. Kipiani: And has anything been published in Russian, perhaps?

B. Gayauskas: Probably in Russian too, because it was transmitted quickly—they found out in a week, maybe less. I fell, then, when Astra started knocking, the guards opened the door. I regained consciousness again for a short time, I see him (Romashov) standing near me—not right next to me, but further away, he’d thrown down the screwdriver. They came in. And I lost consciousness again. I don't know how long it was before I regained consciousness in the medical unit. Then a guard took me to the hospital. They performed surgery there and then took me to the camp hospital.

V. Kipiani: And how long were you in the hospital after that?

B. Gayauskas: Three weeks, I think. They stitched me up; it didn't reach the heart.

V. Kipiani: [Inaudible].

B. Gayauskas: Yes. Well, I couldn't have known anything, because I was unconscious. When I came to, I didn't feel that anything had happened to me. Then, when I was fully conscious, I look—I'm half-naked, bandaged up here, blood here. I’m thinking, what’s this? Then I understood.

V. Kipiani: And what did Romashov get for what he did?

B. Gayauskas: The people from this Kuchino told me; I didn't know any of this. At the time, when they brought me back, there were rumors that he would be tried, that a case had supposedly been opened. I didn't know if he would be tried or not; I never saw him again. They kept him in another cell; we didn't see each other. But these people (the staff of the Perm-36 museum – V.O.), who have now looked at his file, all the cards—nothing, not a word about this incident, nothing. And my file—I didn't know this either—is now in the Lubyanka.

V. Kipiani: Have you seen it already? I mean, is it declassified? Or is there still no access to it?

B. Gayauskas: My file?

V. Kipiani: Yes, your file.

B. Gayauskas: I don't know, I just found out now that my file is in the Lubyanka; these people told me. They checked all the documents at the Lubyanka, of many people, not just mine. And the files of those who were released around that time were sent to the Lubyanka, and those who were released later—their files are there. They reviewed all of our files. Romashov's file is there, but not a word, not a single word, no order saying he was in the punishment cell for it—it’s as if nothing happened.

V. Kipiani: Tell me, was there another Lithuanian with you in Kuchino, if I'm not mistaken?

B. Gayauskas: Petkus?

V. Kipiani: Yes. Can you tell us a little about him?

B. Gayauskas: He was serving his third term then. They brought him from a prison in Tataria. How long did he serve there? Well, until the end of his term; he got ten years. I don’t remember, I think he served eight years there, or a little less. We weren’t in the same cell, as they always tried to keep people of the same nationality from being in the same cell. Only the Ukrainians were, since there were so many of them, there was nowhere else to put them, so that’s how they kept the Ukrainians, it was just impossible otherwise, they were kept two to a cell. But we were kept separately, and how he behaved in the cells, I can't say, because in another cell—that's a different world, and you don't always have contact. If it's further away, there's no contact at all. And I don't know exactly when he was released, I didn't check. I think there are lists; I don't remember the release date. But he was also one of the last to be released. I was the very last to be released.

V. Kipiani: On what day did that happen, your release?

B. Gayauskas: It was in 1987, on April 22.

V. Kipiani: On Lenin's birthday, then?

B. Gayauskas: Yes, well, it was the end of the term, upon completion of the sentence, ten years.

V. Kipiani: And you went straight home?

B. Gayauskas: No, no, I had five years of exile. They took me to Khabarovsk Krai, to a small town there called Chumikan, on the shore of the Sea of Okhotsk.

V. Kipiani: And what did you do there? What was your job?

B. Gayauskas: I worked as a watchman. There was a fishing kolkhoz there. There wasn't any real work, and it was generally hard to find work there, but I couldn't work anywhere else. In that kolkhoz, they either fished or hunted for sable in the winter. I couldn't fish because they only took healthy, young men. Brigades were organized, there was a brigade, but they were mostly young because it was very hard work. And they worked from morning until dark, because this fish—the keta salmon—it only runs for two weeks, and you can only catch it during those two weeks, and that's it. So it was terrible work; I couldn't work there. And in the winter, of course, they would send people by helicopter into the mountains to trap sables.

V. Kipiani: And when did you return from exile? You didn't serve the full term of exile, did you?

B. Gayauskas: No, I returned in 1988, on November 7. That makes it seven years since I returned.

V. Kipiani: Tell me, what were you charged with in that case? You had several sentences, I know?

B. Gayauskas: Yes, it was anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. I had a translation of Solzhenitsyn's *The Gulag Archipelago*, I had partisan documents, various other materials, documents from the Moscow *Chronicle* of Current Events. They knew about my connections to Moscow. They found all these different materials.

V. Kipiani: Tell me, please, if you're able to share, what were the channels for transmitting materials, specifically from Kuchino, to the outside world, to the West?

B. Gayauskas: Only my wife could transmit them, while I was still allowed visits. And then, when they, the KGB men, had collected all this material that was being published—then that was it, it stopped. I didn't have visits for four years. But I probably couldn't have written anymore anyway, because the tension was immense. And the risk—that's another ten years if I got caught. I took the risk. I wasn't afraid, but it was hard to endure that kind of tension, because you had to be on edge every minute, so as not to get caught, so they wouldn't figure you out. Because you're always being watched, you have to find moments to write, you have to keep it all in your head—where you left off, and then where to begin. There can't be any drafts. You have to get paper—from where? If you don't have that thin paper, you can't do anything. It's all a huge amount of work, very tense and risky. And then it gets smuggled out. And there, with the Muscovites, it's less of a problem. Of course, you always feel you're in danger until they publish it. When you find out it's been published, then you feel good. Because your wife could also get caught. If she gets caught—it's up to seven years for distributing anti-Soviet materials. She would pass it to Sakharov's wife; she often did that—also a risk. Who she would pass it to, I don't know. To some foreigner. How it proceeds from there, you also don't know.

V. Kipiani: What were your impressions of the guards? There were different kinds of people there, weren't there?

B. Gayauskas: Different people, yes, different people. There were a few very bad guards, there were average ones, like Kukushkin. I wouldn't say he was bad, but he was so-so, you could still get by with him. I saw a photograph—Ovsienko is sitting there, Kukushkin and Shmyrov (Viktor Shmyrov – director of the Perm-36 Museum. Photograph from September 14, 1995. – V.O.). And there were some... for instance, there was one Ukrainian from the army, I forgot his name—he was so nasty (Vlasyuk. – V.O.). A young guy, and it's like, his countrymen are imprisoned there, and he's nitpicking. How could he not be ashamed? Let's say, he can nitpick at me, I'm some Lithuanian, but here are his countrymen. You might run into them later, what then? Well, despite that, he was nasty. Later, towards the end, he probably felt it was temporary; he left, lives somewhere near Odesa, they told me his address. I studied these guards, because it was very important to me. I knew each one's walk, how he walks, because one of them would run down the corridor every time and look in the peephole. So you had to be wary of that one, if he was on shift. You had to be wary. And I didn't know who was coming on shift, I couldn't see them, but by their walk, when they paced, I already knew if they were good or bad in that respect, whether they looked in the peephole often or rarely.

V. Kipiani: Tell me, how did you get involved in human rights activism in the first place, and what was your total sentence? That's important.

B. Gayauskas: Well, how else? The country was occupied—one had to fight. It's very simple. Young people—they are always patriotically minded, they always have ideas. When they came in 1940, I was 14. I already understood that these were clearly occupiers, and we all thought so. That meant something had to be done. When you're that young, a kid, what can you do—nothing. But by 17 or 18, you start getting involved with leaflets, with other things. It's clear it's an occupation, and that's it—you have to fight.

V. Kipiani: So, were you one of the Forest Brothers or not?

B. Gayauskas: Yes, that was our armed underground organization. We were involved in many things, not just that; we were heavily involved in literature too. We had a great many underground newspapers coming out; every partisan district had its own paper.

V. Kipiani: And you contributed to this newspaper?

B. Gayauskas: Yes, of course.

V. Kipiani: What was the newspaper called?

B. Gayauskas: There were many, many newspapers, with different names. For example, in one district they would start publishing one, and then people would get caught, or something else would happen, the paper wouldn't come out for a while, and then it would start coming out under a different name, in some other place—that was done on purpose. If you were to count how many titles there were—I don't remember now, but probably about twenty, no less. That's in the partisan districts. And the underground organizations published their own. Sometimes they published for a very short time, because they were caught. Only two issues would come out, the organization would be exposed, and so they stopped publishing. Others published for longer; it varied. But a great deal was published here. We still don't know all of them; we are only researching it now. Not all copies have survived; a portion was found somewhere in the KGB, and another portion we know about. There are people who published them, but the newspapers themselves are gone.

V. Kipiani: I know you head a political Union?

B. Gayauskas: Yes.

V. Kipiani: Because the other day I found a booklet, “Who is Who in Lithuania 1993,” and your portrait is in it; I read it. Tell me, how many people took part in the organized resistance movement in Lithuania? How widespread was it?

B. Gayauskas: We don't have a figure yet for how many people were in the resistance. What counts as resistance—the armed resistance, the unarmed resistance, which was very widespread here, it was everywhere. We don't have such a figure yet. Right now, we are counting the partisans who had weapons and were in units, who fought in an organized way. We are currently preparing to publish three volumes of lists of fallen partisans. We already have one volume, with 20,000 names collected. We haven't published it yet, but we've been researching all this for four years, because it's very complex work: you have to verify and re-verify, travel around, ask questions, check documents, to make sure everything is correct. We believe there's still two-thirds of Lithuania to go. In this one-third part, we collected data from where the most documents remained, and where the resistance was strongest. In other parts of Lithuania, it will be less, but approximately around 40,000 killed, maybe fewer. Then we also need to count those who ended up in the camps. Those who died in the camps. Those who were released and are still alive. There are about three hundred of us left alive. There are also several dozen people who live in Latvia, in the Kaliningrad Oblast. They are the survivors—those who had weapons and participated in the organized resistance. And also the couriers. There were many couriers, too; we don't know all of them yet, we are just now trying to count them as well.

On the fourth, there was a congress—I don't know what to call it exactly in Russian, let's call it a congress. Several hundred partisans and couriers gathered there. Our Union awards these people; we have a medal, a certificate. Every year we hold this congress. It's not so easy to restore these figures. Then there are the underground organizations. It's also very difficult to research them all, because during Stalin's time there were very many of them. Almost every school—the older students, universities, institutes, villages, factories—they were all involved. It's a huge amount of work.

V. Kipiani: Tell me, how much time did you personally serve?

B. Gayauskas: Thirty-seven years.

V. Kipiani: And when were you first convicted?

B. Gayauskas: In 1948.

V. Kipiani: For being caught with a weapon, or for literature?

B. Gayauskas: Yes, with a weapon. It was all part of it—both the weapon and the literature.

V. Kipiani: Were you living in Vilnius then?

B. Gayauskas: No, in Kaunas.

V. Kipiani: Kaunas, it seems to me, was the center of the resistance, wasn't it?

B. Gayauskas: Yes, yes, the center of national resistance.

V. Kipiani: Because many Poles, Jews, and Russians lived in Vilnius?

B. Gayauskas: Yes, yes. Besides, Kaunas was the temporary capital of Lithuania, and mostly Lithuanians lived there, and Lithuanians live there now. There are very few foreigners, other nationalities.

V. Kipiani: Tell me, please, if we just look at the chronology of your sentences since 1948, until what year was the first sentence and where did you serve it?

B. Gayauskas: The first time, they took us to Balkhash. In Balkhash, I was in two places: in the city and, I think, 35 kilometers from the city of Balkhash; there was a molybdenum mine there. Then—Dzhezkazgan, a regime camp. Just today, by chance, I met a Ukrainian who was in that very camp, and I was there at the same time. We started talking—we both know all those places, but we didn't recognize each other. Well, of course, it's been so long; he was young and I was young. We talked. So, I was there, in Dzhezkazgan, then in Mordovia. Always there after 1956, when many people were released. I was in various camps in Mordovia, in almost all of them; they kept moving us around.

V. Kipiani: The first time, how many years did you get? Ten?

B. Gayauskas: Twenty-five.

V. Kipiani: Twenty-five, right away?

B. Gayauskas: Yes.

V. Kipiani: And you served until what year? From 1948 to...

B. Gayauskas: Until 1973.

V. Kipiani: Meaning, without being released?

B. Gayauskas: Without being released. Day for day, as they say, from bell to bell. And then they gave me ten years in a special-regime camp and five years of exile. They took me to Mordovia again, to the special-regime camp, and in 1980 they sent me to the Urals. And after the Urals, to the Far East.

V. Kipiani: Tell me, do you have any regrets about how your life turned out?

B. Gayauskas: No, of course not. What is there to regret?

V. Kipiani: What did you want to become, what did you plan to be? Because I understand that at that time...

B. Gayauskas: I would have enrolled in the history department, but I already felt that I wouldn't be able to enroll anywhere.

V. Kipiani: You wanted to be a historian, but it didn't work out?

B. Gayauskas: It didn't work out. We saw that a struggle was going on; those who were studying, the students, they were also dropping their studies and joining the struggle. That was the primary goal—liberation, and then everything else.

V. Kipiani: Don't you think you made a mistake, for example, by taking up arms, and that you should have acted underground, more with leaflets, more by persuading people?

B. Gayauskas: No. There was a tactic. We had to change the partisan tactic. It was changed in 1948. At first, we thought there would be a war, that we would have to fight against troops, against a regular army, so we also needed to prepare a regular army. We started preparing battalions and so on, like a regular army. We didn't switch to partisan warfare—that was the mistake. We switched in 1948, when we realized that nothing would happen here soon, or perhaps ever, and that in the near future we would all perish. We should have applied that tactic back in 1944-1945. We would have saved many people and inflicted more damage than we did.

V. Kipiani: And one last question, if I may. I know that the Lithuanian Helsinki Group was one of the strongest in the Soviet Union. Just the other day, I was looking through some clippings and found an article from the newspaper *Soglasiye* about the Lithuanian Helsinki Group. Your name is there, among others. Tell me, when was it created and how did you get involved with it?

B. Gayauskas: It was created—I can't give the exact date now—around the time of Kovalev's trial in Vilnius. Approximately at that time. (Founded on 11/25/1976. – V.O.). They included me when I was already in the camp. I agreed reluctantly because I was involved in slightly different things, and I didn't want to surface like that. Although they knew me, they were always watching me, and once I was caught, there was no point in refusing—I was already caught anyway.

V. Kipiani: And you were a member of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group right to the very end, yes?

B. Gayauskas: Yes, yes.

V. Kipiani: In what year did it cease to exist?

B. Gayauskas: It still exists even now, but the people have changed, and it's not as active anymore, well, and there isn't the same need for it. But back then, of course, it was necessary and useful.

(Notes by Vasily Ovsienko, 01/28/2010)

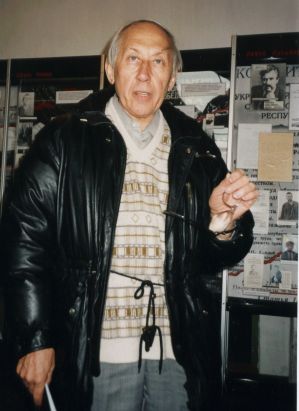

Balis Gayauskas at the Perm-36 Memorial Museum of the History of Political Repression and Totalitarianism - the former special-regime camp VS-389/36, in the village of Kuchino, Chusovskoy District, Perm Oblast. October 3, 2000. Photo by V. Ovsienko.