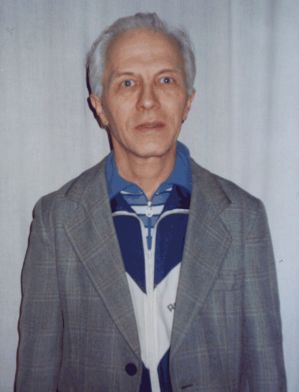

Interview with VADYM VASYLOVYCH PAVLOV

V.V. Ovsienko: March 10, 2007. Vadym Vasylovych Pavlov is speaking. Vasyl Ovsienko is recording.

MY FAMILY

V.V. Pavlov: I was born in the city of Kyiv on August 21, 1951. My father was Russian, originally from Russia; he ended up in Ukraine after the war and married my mother here. My father, Vasyl Illich Pavlov, born in 1925, served seven years in the army and was a front-line soldier. After his military service, he worked at a military plant as an instrument test mechanic and, unfortunately, died tragically; he drowned in 1961. My mother was of mixed origin: on her father’s side, she was of Swedish descent, Olha Adolfivna Savost. The surname had already been Russified. She was born in 1924 and now, thank God, is still alive, retired, in her eighty-third year. She is of mixed origin; as far as I know, her ancestors included Ukrainians, Russians, and even French, but unfortunately, there are no documents. But from what I know from stories, my great-grandmother on my mother’s side was of Cossack descent; her surname, I believe, was Sukhoruchenko. By the way, my great-grandmother’s nephew was repressed back in 1918, shot. Somewhere at the Lukianivske Cemetery in Kyiv, they were shooting people, and he died there because he was in the army of the UNR, under Symon Petliura.

My father died early, but my grandfather, Adolf Savosta, was still alive. He was an artist, a pre-revolutionary intellectual. He and my mother, as I heard from childhood, were critical, and even more than that, opposed to the Soviet government, to communism, and this probably influenced me.

I started school in 1959 and studied until 1969, finishing ten grades. I studied well, mostly getting fives, with only two fours.

My grandfather spoke critically while he was alive—unfortunately, he died in 1963, when I was about eleven and a half. If he had lived longer, I would have asked him much more. He was a very interesting person, studied a lot his whole life—both at the art institute and at a military academy before the revolution, and was a participant in the First World War. Unfortunately, I don’t know for sure, but he took part in the events in Kyiv during the time of independent Ukraine, but I don’t know for sure whether it was under Hetman Skoropadsky or in other Ukrainian military organizations during the UNR. I was still small when he told me about his participation in those events. My grandfather had a great influence on me. He told me a lot about pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary events. By the way, my grandfather did not want to join the Communist Party because he did not recognize the October Revolution. He was an artist, and they told him: “If you join the party, you’ll be in the Union of Artists, you’ll have privileges.” He refused and worked more as a decorative artist, restoring churches; he worked at the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, St. Sophia’s Cathedral, and St. Volodymyr’s Cathedral. I remember when I was little, he and my mother told me that he was arrested sometime in December of ’thirty-six or January of ’thirty-seven. As a decorative artist, he had once decorated Yakir’s office, and when he was arrested, they wanted my grandfather to give some testimony against Yakir. They came at night, arrested him, and he was interrogated all night, but as far as he said, he gave no testimony against Yakir. He was eventually released—he was a good specialist, an artist, and somehow it worked out.

There was another interesting incident with him. As an artist, he completed some job, and then went to a café to celebrate after they got paid. He was sitting there with friends and telling some joke, or something about Stalin. A plainclothesman “from the agencies” came up (they say that such employees often sat in cafes and restaurants back then, keeping an eye on things). He says: “What was that you said? I’m going to arrest you right now.” But it was only because another artist, Karl Welke, was there with my grandfather—an old Bolshevik who used to transport Lenin’s newspaper *Iskra*, but when Stalin came to power and the repressions began, even this old Bolshevik became disillusioned with his communist cause... So he said that they hadn’t heard anything, and so my grandfather was saved a second time. And the NKVD man said: “It’s a pity I don’t have a witness with me, or I would have taken you.”

V.O.: And did you mention that grandfather’s name? Or say the years of his life?

V.P.: My grandfather, as far as I know from the documents, was Adolf Vilhelmovych Savosta. They distorted the surname. My mother is listed as Savost, but my grandfather as Savosta. That happened with foreign surnames. He was born, according to the documents and his own words, on August 20, 1891, in Stockholm, Sweden. He was a Swede by nationality. Before the revolution, there was a large emigration from Sweden to various countries, so he came here, studied here in Ukraine, lived here, got married, and lived his life here.

V.O.: It was enough to be a foreigner to be shot. He lived until 1963?

V.P.: Yes. The only thing that saved him was that he was a very good specialist, a restorer, a decorative artist, and somehow it passed him by. Of course, after the fall of the UNR, he did not actively oppose the government.

V.O.: “There are no indispensable people,” said Comrade Stalin.

V.P.: Well, somehow he was lucky, he survived. He had a very great influence on me. He told me about one incident. An acquaintance came to his house in the thirties, when the massive Stalinist repressions had already begun. He came and said: “Adolf, what is going on, they are even destroying their own?” And my grandfather says: “And didn’t you greet the Bolsheviks in eighteen with bread and salt?” And the man says: “Well, who would have thought it would turn out like this!” Many people were deceived. The Bolsheviks promised a happy life and everything, and then it was too late to turn back.

And my mother also learned from my grandfather. By the way, my mother told me a lot in my childhood about the famine of 1932-33 in Ukraine, so I knew about that too. Well, the details, that it was planned by the Bolsheviks—of course, ordinary people didn’t know that then. Even in Kyiv, my mother said, many people were starving. Those who worked in production still got some sort of ration so they wouldn’t die of hunger, but many people, especially from the pre-revolutionary intelligentsia, the elderly, or those who absolutely did not want to cooperate with the Bolsheviks, had a very hard time—people sold their last valuables. My mother told me that before the revolution, my grandfather graduated from the Kyiv Art School (it was a branch of the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts) with a gold medal. He even went to Italy—it was a kind of reward: after graduation, a group of students went to Italy for practical training. He had a gold medal, so he turned it in to a *torgsin*—there were such stores then—so as not to die of hunger. There were also some silver spoons and forks. His wife didn’t want to give them up, saying, we have two daughters, they need some dowry, as was customary before. My grandfather said: “Well, if we die, there will be no us, no daughters, and nothing. But if we’re alive, we’ll somehow earn a living.”

My mother told me this. During the revolution, many buildings in Kyiv burned down: there were the Reds, then the Poles, then the Germans, then the White Guards—many buildings burned down. So they settled with relatives—there was a small hut in Predmisna Slobidka, which is now Hydropark. There, my mother says, about 30,000 people lived before the Second World War.

V.O.: In Hydropark?

V.P.: Yes. There were private houses, many people lived there. My mother says, probably sometime in December 1932 or January 1933, there was a blizzard at night, a snowstorm, the dogs were barking, and someone was knocking at the gate. They went to open it—a young girl, 16-17 years old. She says: “Let me at least spend the night, to warm up, I’m very cold. There’s a famine in our village, people are dying out, I’m going to Kyiv,” she says, “to find some work so I don’t die of hunger.” Their situation was also difficult, because my grandfather didn’t officially cooperate with the authorities as an artist, and in those days even the churches were closed, so there was no way to earn extra money. Before, they would restore something in the church, icons or paintings. They were selling the last of what they had. But they shared what they could with this girl, she spent the night, got warm, and left the next day.

And another man, now deceased, our neighbor, Volodymyr Vasylovych Voronovych, a Kyiv native born in 1924, told me that even—he was still a young boy then, during the Holodomor—in Kyiv, special trucks would come in the morning, many corpses were just lying on the streets, so they would collect these people’s bodies and take them somewhere. That’s how it was. My mother told me about the repressions of the Stalinist era, too.

And the events of 1968 in Czechoslovakia had a great influence on me. I was in the ninth grade when the “Prague Spring” began. There were great hopes, especially among the youth and intelligentsia, that if it succeeded there, maybe we would have some changes for the better here. But, unfortunately, they crushed that uprising of the Czech and Slovak peoples. I was very upset about it, even wrote a long poem about these events, and read it to my friends. But, unfortunately, I didn’t have any acquaintances or friends who truly understood what was happening in the country, who were critically and actively opposed to that Bolshevik government.

In the sixties and seventies, I listened to “Voice of America,” Radio “Liberty.” Although they were jammed, you could sometimes hear something, even though the receiver was old, but not bad, a “Riga-6”—the Balts still worked conscientiously, they hadn’t unlearned how to work conscientiously from pre-Soviet times. So it was a good receiver, you could sometimes listen to something, especially around midnight, after midnight. Of course, these events had a great influence on me. I was very upset after the suppression of the revival in what was then Czechoslovakia. I read this poem to friends—I had a few friends who were somewhat critical of the Soviet communist system of the time, but there were none with whom I could form a group or some organization, or actively oppose the government, to do something. Well, we were finishing school, planning to continue our studies, in institutes, in universities—to live as all Soviet people lived then. I was very lonely, I experienced all this. And so I finished school.

My father died tragically in sixty-one, he drowned. Of course, my mother wanted, like all mothers, for me to study further, to have an education. But at that time I already understood a lot, I was critical of that communist system. Although, of course, there was strong propaganda in school, on television, on the radio, in newspapers, so there were some illusions. Especially among some old people who gathered for some holidays, for a birthday. Some said that, well, maybe if Lenin had been alive, maybe things would have been better, maybe there would have been more justice. Such illusions lived among the people, because Lenin was in power for a short time. People didn’t know the truth; it’s only in recent years that the archives have been opened, and we learned what orders he issued. But then people knew little, so for them, Lenin was something of an ideal in contrast to Stalin and his repressions.

Before that, I attended an archeology club at the Palace of Pioneers, I was interested in ancient history, archeology, but in recent years I became more interested in philosophical problems, philosophy. On the other hand, I understood that both history and philosophy—all of it was permeated with the official communist ideology, the Marxist-Leninist doctrine.

YOUTH

Since I was born seven months premature and had poor health from childhood, my mother sent me to school at the age of eight. I finished ten grades right at the age of 18. I still couldn’t decide what to do next. On the one hand, I wanted to have an education, to study, and on the other hand, there was a certain aversion to that system.

It so happened that it was time to serve in the army. In 1969, I went into the military. First, I was in a school for junior aviation specialists, in 1969-70 I studied for seven months as an aircraft electrical equipment mechanic, then I served in a military unit in the Kaliningrad region. I served for two years. True, I developed a stomach ulcer in the army, my health was undermined.

I returned from the army, still had some illusions, thought maybe something would change for the better, maybe there would be some reforms in the country. By then I had heard a little on Radio “Liberty,” on “Voice of America” about the Ukrainian dissident movement. They were starting to talk a little about Sakharov then, about Solzhenitsyn.

V.O.: And you weren’t acquainted with anyone? And didn’t seek such acquaintances?

V.P.: I already said that among my friends and acquaintances, there was no one like that. In the archeology club, we had two comrades, Leonid Zalizniak and Mark Horovskyi. Mark Horovskyi once told me, when we were in the ninth or tenth grade, that his father had studied at Kyiv University before the Second World War in the history department, he raised some national issues, so, it seems, he was exiled from Kyiv to Siberia. He wasn’t imprisoned, but he was still subjected to some repression. And Leonid Zalizniak’s father was convicted twice in the Stalinist era—before the Second World War and after the war, he served many years in prison. But even these children and their parents, who had served their sentences, showed no activity. Maybe they were afraid for their families, for their children, they didn’t want trouble, because they had already suffered enough. Although I didn’t know the specifics of their personal lives at that time. I didn’t have such friends. There were thoughts, especially after the Czechoslovak events, of creating some youth organization, but there were no like-minded people. Some shared my critical thoughts about the government of the time, but there were no such like-minded people.

After serving in the army, I thought and thought about what to do next... My mother raised my brother and me alone, so I had to enroll in a correspondence course.

V.O.: And did you mention your brother’s name?

V.P.: My brother is Yurii Vasylovych Pavlov, born in 1953, a year and a half younger than me. I thought that I should help the family, so I enrolled in the correspondence department of Kyiv University, in the history department, in 1972.

V.O: And I had already graduated from there in 1972 with a degree in philology…

V.P.: I had doubts about whether to go into history. I was also interested in philosophy, and at first, I thought about enrolling in the philosophy department, but I understood that it was very connected with the communist Marxist-Leninist ideology. So I even thought that maybe it would be better to study by correspondence, there I would be somewhat detached from that system. There was hope that over time, maybe something would change for the better. By then, Solzhenitsyn was heard of in the world, they wrote about him in the Soviet press, of course, the information was critical, and they sometimes mentioned Sakharov, and Ukrainian dissidents.

V.O.: And did you hear about the arrests of 1972 in Ukraine?

V.P.: Yes. They reported it on Radio “Liberty,” the BBC. If someone had approached me then with a proposal to sign a letter or an appeal to the Soviet authorities protesting the repressions against representatives of the Ukrainian intelligentsia, I most likely would have signed such an appeal. But I myself probably lacked the courage then to come out with some protest on my own. The people who surrounded me then believed that it was pointless to fight the existing communist government, that this government was invincible. Even my mother’s own sister, Liubov Adolfivna Tkachenko (née Savosta), who had suffered a lot from the so-called Soviet, communist government, when she learned about my critical speeches against the CPSU and so on, once told me that I had probably really gone mad, because I went against such a powerful force, a whole system.

By the way, it’s interesting to recall: I returned from the Armed Forces in November 1971, and in May 1972 I was preparing to enter Kyiv University. On May 22, 1972, I was near the Shevchenko monument. But I couldn’t get close. There were a lot of police, people in plain clothes, obviously from the KGB. Anyone who tried or managed to break through closer to the monument was grabbed by the police, people in plain clothes.

I also remember my first visits to the monument of Taras Shevchenko on May 22, 1969. I was finishing the 10th grade then, and also studying in the archeography club of the Kyiv Palace of Pioneers. Once, Leonid Zalizniak, the son of the former political prisoner Lev Zalizniak, told me and a few other boys from the archeology club that on May 22, Ukrainian patriots would gather near the monument to Taras Shevchenko. Mark Horovskyi and I went there. Leonid Lvovych Zalizniak was there, well, then he was just Lionia Zalizniak, now he is a professor, a doctor of historical sciences, a lecturer at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. By the way, there we met Mark Horovskyi’s father—he was a former repressed person, a historian. Lionia Zalizniak’s father, Lev Zalizniak, was also there, I don’t remember his patronymic anymore. There were quite a few, two hundred, maybe more people. Of course, there were a lot of police, they surrounded the area. They sang Ukrainian songs, but they didn’t let anyone speak. And they didn’t even let people get close to the monument. But right at the monument, there was a small number of people, mostly young, probably students. Most likely, they came to the monument very early. But they were tightly surrounded by police and people in plain clothes. There was an interesting moment. One young man—I don’t know his last name, patronymic—approached, laid flowers at the Shevchenko monument, crossed himself, bowed, and wanted to say some speech, but some people in plain clothes grabbed him and took him aside. People surrounded him, didn’t give him up, they defended him. He somehow broke free. These were probably KGB agents in plain clothes. People were there for several hours, but it was impossible to hold a rally. Then they began to disperse.

And a few days later, Leonid Zalizniak told me an interesting story about that day. These KGB agents, the police, tried to track down at least a part of the people—where they were from, who was present at this gathering near the Shevchenko monument. The number 12 trolleybus ran there, there was a stop near the university, and, he says, a lot of people, young people, crowded into this trolleybus. And these KGB agents, the police, also got in there. They realized that they would be riding and watching them. So some boys climbed onto the back of this trolleybus, pulled down the poles, the driver had to open the doors, get out to fix these trolleybus poles, and these boys got out and ran away, everyone scattered. Most of them still escaped. Later they said that many students were expelled from the university for participating in such events.

V.O.: Interestingly, what time of day were you there on May 22, 1972?

V.P.: Around, I think, about twelve, maybe at eleven in the morning. In the first half of the day.

V.O.: Because around 5 p.m. I had a meeting with a friend, Petro Ostapenko, in the Botanical Garden, which is nearby, I was supposed to get some *samvydav* from him. They even tracked me down there: a policeman came up to check my documents, saying I looked like someone. I got the hint and didn’t go to the monument.

V.P.: It was about one o’clock, maybe eleven, sometime in the first half of the day. There’s a park there, people were relaxing, playing chess, checkers, so many people gathered under the guise of relaxing. They walked around, so as not to stand in one place, to somehow show that they had supposedly come here to walk, to relax. Such were the events.

V.O.: Were there no consequences for you for appearing there?

V.P.: First of all, I didn’t speak out myself, I was there among the people, and maybe because I’m short, one meter sixty-two, and looked very young... When I was finishing my service in the army, one officer said: “Oh, he’s so young, he could be drafted again for a new term.” So maybe the KGB agents took me for some schoolboy, because I looked about 16, I was very small. So it somehow worked out.

In 1972, I enrolled in Kyiv University in the history department, in the correspondence department, and studied. But, honestly, the situation was oppressive. I heard on Radio “Liberty,” on “Voice of America,” on the BBC: arrests began in Ukraine, seventy-two, seventy-three. It was clear that the situation was unlikely to change for the better.

V.O.: That’s when they nabbed me too, in seventy-three. You studied by correspondence, so you worked somewhere, right?

V.P.: Yes, I worked. Even before entering the university. I came back from the army in November 1971, so I took exams for the university the following summer. A relative, my father’s sister, got me a job through connections at the Fourth Medical School in Darnytsia, in the social sciences department. They taught Marxist-Leninist philosophy to the female students there—why they needed it, these future nurses and paramedics? I worked there as a lab assistant. What’s interesting, there was a philosophy teacher there, a woman—I can’t remember her name now—she was a philosopher herself and, obviously, a member of the CPSU, she taught Marxist philosophy. Brezhnev was in power then, and she was very critical of him. This also influenced me, as a young man. Sometimes we talked about political topics. Once she came and said: “Well, they’ve praised this Brezhnev to the skies, pinning all the medals on him, so distinguished. And what,” she says, “can we do? We just have to wait until he dies.” Those were the thoughts, such passivity was among the people. It was perhaps easier for her to wait, she was already a woman of a certain age, almost 50, married, maybe she had a family, children, and, of course, she treated it as, we’ll wait and see what happens. Well, I was still young, so I wanted to change something for the better. On the other hand, I had, of course, heard from my mother that my grandfather was arrested, and other people.

By the way, there are no documents about this, unfortunately. Maybe somewhere in the archives. I should look for them somehow. And people were afraid to talk about it. Only in 1990, shortly before her death… My father’s sister, Paraskoviia Illinichna, who went by her husband’s name Ivanova, died at the age of seventy. She told me that my grandfather, Illia Pavlov, worked as a train driver in the thirties, right when the Holodomor was happening. They transported grain through Ukraine and from Ukraine to the Polish border, where it was reloaded onto foreign trains. And he also supposedly expressed himself… They were traveling through Ukraine, saw corpses lying around, people were hungry, dying, so he said something like: “How can it be that people are dying of hunger, and we are transporting grain, selling it abroad?” And he was also arrested, repressed, and nothing more is known about him, where he ended up or what happened. And even her mother didn’t tell the children what happened to their father, she said he went to Siberia to earn money. Only shortly before her death (she died around 1980, she was already 83) did she tell this to her daughter, my aunt Paraskoviia Illinichna Ivanova, that their father was repressed in the thirties. People in those times were even afraid to talk about such things.

Of course, all this influenced me. On the one hand, I wanted a different life, freer, more democratic, and on the other hand, I also wanted an education. I often thought about this, talked with some friends. To write some protest… Well, I wrote critical poems, read them to friends, but to speak out somewhere, maybe I still didn’t have the courage.

By the way, in 1968—I was only 17 then, right on August 21, my birthday—I went in the morning and bought some newspapers, and there were many pages of these documents about the Czechoslovak events, about the introduction of troops into Czechoslovakia—that was the “gift” the Soviet government gave me for my birthday. Of course, this somehow influenced me, I thought, what to do next?

And in 1973, a friend, Yurii Volodymyrovych Voronovych, also born in 1951, his grandfather was also repressed, his grandfather’s surname was Lypskyi… He was from a wealthy family, maybe even of Polish origin, because his grandmother, his grandfather’s wife, was a Pole from Warsaw. Before the revolution, he graduated from some junker or military school, he was still a young boy. He did not recognize the Soviet government, often criticized it. And someone informed on him, he was arrested—and so he perished in the camps, it’s not even known how he died or where his grave is. He was such a brave man that even from prison he wrote to his wife, that’s my friend’s grandmother: “Send me some rope so I can hang myself, because I can’t, I don’t want to see these bandits”—that was his attitude to that government.

FIRST BRUSHES WITH THE AUTHORITIES

Of course, these people were afraid of repression, they tried to adapt to that communist-Bolshevik government, although they themselves were from families of the repressed, their parents and grandfathers had suffered, and they, of course, couldn’t get a good education. And so he, Yurii Voronovych, worked at the Institute of Hydro-Melioration as a lab assistant, and traveled to Crimea. In Crimea, some old library was closed, and they found Stalin’s works there. Under Khrushchev, they had already been thrown out of libraries, written off. He brought them to me, and out of curiosity, I looked through some of them. I was very impressed that in one of Stalin’s works, *On the Foundations of Leninism*—these were written as lectures that Stalin gave at Sverdlovsk University after Lenin’s death—that Lenin had introduced something new to Marxist doctrine. There I read one article—Stalin’s work on the dictatorship of the proletariat. There is an interesting thesis there—by the way, he referred to Marx and Lenin, that they had introduced such a thesis into their doctrine. Stalin writes that, since the party is the instrument of the dictatorship of the proletariat, then with the construction of a classless society, with the abolition of the dictatorship of the proletariat, the communist party also withers away, all power is transferred to the people, there will be a republic of Soviets. This interested me so much! I thought that I should take some part in public life, do something. And I began to read some other works by Marx, Engels, Lenin. There too I found confirmation of this thesis about a classless society, about the withering away of the party. And since under Khrushchev it was declared that we no longer have exploiting classes, that we are already moving towards a classless society, that the difference between workers, peasants, and the intelligentsia is small, these are not antagonistic classes, I seized on these theses and first wrote to the Institute of Marxism-Leninism, that it’s interesting, if even Lenin, Stalin, Marx wrote that with the withering away of the dictatorship of proletariat, with the construction of a classless society, the communist party is no longer needed, then, obviously, it should be dissolved and power transferred to the people. They didn’t answer me for a long time. Then I wrote to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine to Shcherbytsky, to the Central Committee in Moscow, I wrote that since I am studying in the history department, it is interesting for me to know this, both from a historical point of view and as a citizen of my society, my state—I would still like to receive some clarification, an answer. How is it that Marx, Lenin, even Stalin, wrote that the communist party should be dissolved with the construction of a classless society, and now—on the contrary. This was right under Brezhnev, 1973, there were already articles by Suslov and Brezhnev that the role of the communist party would increase as communism was built—and how to understand this, it’s a contradiction?

At first, they summoned me to the city party committee, but there was essentially no conversation there; a man of advanced age was sitting there, he didn’t give his last name, some Fedir Ivanovych, it sounded something like Shaliapin—Fedir Ivanovych. He asked where I studied, who I was, what I was, who my parents were, and had a chat with me like that. I said that I had written to the Institute of Marxism-Leninism, wanting some clarification. He says: “Wait, maybe you’ll get some answer.” After some time, a letter came from the Institute of Marxism-Leninism. They wrote that the struggle with international imperialism was intensifying in the world, and therefore it was necessary to strengthen the leading role of the party to help other countries fight for revolution, for socialist transformations. And there were such general, evasive replies.

PUNITIVE PSYCHIATRY

But after that, they summoned me to the psychiatrists. Or rather, how? They summoned me to the military enlistment office, supposedly for some check-up. I went to all the doctors, everything was normal—this was in 1973, sometime in the fall. I had already gone to the head of the enlistment office to have him note that I had been examined. He looked and said: “Something’s not right here.” The girls who worked at the enlistment office started running around. A girl comes into the office and says: “You need to see the psychiatrist a second time, she didn’t finish examining you.” We went to the psychiatrist’s office, there was an old grandmother there, smiling like that, she looked at my eyes, nose and said: “You need to go to the district clinic, to the district psychiatrist.” I lived then (and live now) in the Moscowsky district, now Holosiivskyi.

I went to the district clinic, to the psychiatrist. There was a doctor named Zhadanova. She looked me over, but couldn’t decide anything and sent me to Darnytsia, somewhere behind the “Yunist” market there is a psycho-neurological dispensary. I don’t know if it’s still there, but back then, in seventy-three, it was. A doctor named Kryzhanivskyi examined me there. There was another doctor there—unfortunately, I don’t know her last name, and I didn’t know it then, Sofiia Vasylivna. My mother told me that Kryzhanivskyi was inclined to either put me in a psychiatric hospital or give me some psychiatric diagnosis, but that Sofiia Vasylivna thought I was a normal boy, well, interested in politics, various issues. And since they couldn’t agree, they conferred and decided that I should be examined at the Kyiv Central Pavlov Psychiatric Hospital, they sent me for a consultation.

My mother and I went there, and they told us to come on a certain day, there would be a professor, his name was, as far as I remember, Baron. But when we came for this meeting a few days later, they told us—a doctor said it sort of secretly—that Professor Baron had refused to engage in such consultations. Maybe he was an honest man, and they were pressuring him, probably, to give me some diagnosis, so he refused. Then they scheduled another meeting for us. Unfortunately, I don’t remember now—there was another professor.

V.O.: Not Lifshits, no?

V.P.: No, not Lifshits. There was some Solomon Moiseyevich… His surname was Ukrainian, Polishchuk, I think. Have you heard of him, was there such a person?

V.O.: I recall something like that.

V.P.: Yes, Polishchuk, a professor, if I haven’t forgotten. And so we came—I was there, my mother, and also my father’s sister, my now-deceased aunt Paraskoviia Illinichna Ivanova. I went into a large office. Dr. Kryzhanivskyi was sitting there, there was another doctor—I don’t know his name, there was this professor Polishchuk, and there was another man, maybe 40, 45 years old—a white coat was thrown over his shoulder, but you could see that under the coat he had some kind of uniform.

V.O.: A psychiatrist in uniform.

V.P.: Yes, with epaulets, it seemed. Whether he was from some “agencies,” or from the prosecutor’s office, or from the KGB—I don’t know. Polishchuk began to ask questions, what, how. Well, I told him. Kryzhanivskyi and that other doctor—they kept interrogating me—he says: “What are you, a young man, just started studying at the university—and you’re already lecturing Brezhnev, writing to him how to understand Marxist-Leninist doctrine, telling everyone what to do.” And Polishchuk asks: “Maybe you know, in psychiatry there is a concept like ‘overvalued ideas’?” I say: “I’m not a specialist in psychiatry, but I think it means a person has a very high opinion of himself, probably that he’s a genius of humanity, that he can teach everyone—that’s how I understand it.” He says: “You understand correctly.” I say: “But I’m not teaching anyone on my own behalf, I just read—I can name the works of Marx, and Engels, and Lenin, and Stalin—they wrote it. So I’m interested, why did they write that way then, and now they write that the role of the communist party should be strengthened, not the other way around. It’s interesting to me as a future historian and as a person interested in philosophy, as a citizen of my country, my society.” Professor Polishchuk didn’t answer right away, he says: “Let me examine you, listen to you.” He listened to my heart, says: “There seems to be a little tachycardia, you should see a doctor.” He says: “Take an academic leave, get some treatment, rest and think about how you plan to live your life, what to do.” And I say: “And what about the questions I raised? You’re a psychiatrist. I don’t understand at all why I was summoned here and who should be giving me these answers. I would understand if the Party Central Committee or the city party committee held some discussion.” He says: “Well, they used to write that way, Marx, Lenin, Stalin, maybe someday it will be like that, but,” he says, “now it’s Brezhnev, we are guided by his instructions, then maybe there will be other leaders, the doctrine will develop,”—that’s how he answered. And the one who seemed to be in uniform sat and listened attentively, mostly silent, watching. Polishchuk said: “I don’t find anything wrong with you from a psychiatric point of view. Go on, take an academic leave, get a little treatment, rest. I have no complaints against you.” I came out satisfied: everything was normal.

V.O.: You said your mother came with you…

V.P.: They didn’t let her in, she and my father’s sister were in the corridor.

V.O.: And also: did the hand of the KGB show in this story, besides you seeing that man seemingly in uniform? Who sent you there?

V.P.: You see, I wrote letters to the newspapers—to *Pravda*, *Izvestia*, to the Institute of Marxism-Leninism, to Shcherbytsky at the Central Committee of the CPU, to Brezhnev at the Central Committee of the CPSU. Of course, these letters were forwarded somewhere, but they summoned me directly to the city party committee for a conversation.

V.O.: You weren’t a party member, were you? Well, you were in the Komsomol, right?

V.P.: There was an interesting story with the Komsomol too. My mother used to say, when relatives and acquaintances gathered, she would recall the past, that she hadn’t joined the Komsomol. She always somehow refused. She would say at school that she wasn’t ready for that step. Her homeroom teacher once came to their house and saw that they had many icons. Her father had painted some of them himself. My mother’s godfather was a priest. And her grandmother, Paraskoviia Stepanivna, was very religious. And this was 1938. I heard all this from childhood. My grandfather Adolf often said that the Bolsheviks were bandits and bums, riff-raff. Although in school, since the “Khrushchev Thaw,” all crimes and troubles were blamed on Stalin, Beria, and their cronies. We were promised communism (paradise on Earth) by 1980. Everyone wanted to believe in a better future. Although at home there were also talks about the bloody suppression of the Hungarian Uprising of 1956. Of course, at that time it didn’t affect my child’s consciousness much. Although, obviously, something was gradually being deposited in my head.

There was another incident. When I was in the first grade of Kyiv’s school No. 143 in 1959, for the New Year’s party at school, my grandfather Adolf and my mother Olha sewed me a clown costume from a UkrSSR flag. Grandfather Adolf got the flag from somewhere at work and brought it home. My mother sewed the costume: one half was blue, and the other was red. Grandfather Adolf painted large stars on it with silvery bronze. He drew me a clown mask, made a clown’s cap. Now I think it was a very bold step. Because if some outsider had found out about it (and I was 8 years old then. I could have told the children at school what my clown costume was made of), they could have sent my mother and grandfather to prison! It’s a good thing that even at the school’s New Year’s party, no one paid attention to it, at least to the colors of my clown costume. I was just a few votes short of getting the first prize for the best masquerade costume. Of course, this was not a deliberate anti-Soviet action with this flag. But, I think, in what happened, one can trace my relatives’ attitude towards that communist-Bolshevik government and its symbols.

It cannot be said that I was such a staunch anti-communist from childhood, but I was not drawn to the Komsomol either. Now, analyzing my past, I think that I am generally not inclined to be in the ranks of any parties, organizations with strict discipline, a certain totalitarian ideology. The world is boundless. It is obviously impossible to know it completely. As long as I can remember, I have always been and am in the process of learning about this world, in search of the Truth, in reflections on the most acceptable society for people, the structure of the state, and so on. Somehow I did not want to join the Komsomol. Maybe on a subconscious level. Despite the attractiveness of communist ideas at that time, the Soviet totalitarian, repressive system frightened off many people, especially thinking ones. For about two years, I managed to avoid joining the Komsomol. Only in 1967, in the 8th grade, in the spring, on March 1, was I accepted into the ranks of the VLKSM [All-Union Leninist Young Communist League]. And if our homeroom teacher, Lidia Zakharivna Prokhotova, had not detained us in the school cloakroom and taken us to the meeting of the school’s Komsomol committee, where they were already approving candidacies for membership, then maybe I would have finished school without being a Komsomol member. But I didn’t have the willpower to refuse to join then, unfortunately. I studied well. The homeroom teacher pressed me. She even asked my mother once why I wasn’t joining the Komsomol. And by then, in 1968, during the Brezhnev stagnation, joining the Komsomol was more of a formality that didn’t obligate anyone to anything. And how were people accepted into the Pioneers then? They were told to come to school on a certain day with Pioneer neckerchiefs. That’s how they were accepted into the Little Octobrists too. And in the summer of 1973, I submitted a statement to the Moscow district committee of the Komsomol in Kyiv and to the Central Committee of the VLKSM that I did not believe in the possibility of building communism in the USSR or anywhere else and was leaving the ranks of the VLKSM.

When I got a job at the Kyiv Film Copying Factory, in the standard application in the “VLKSM membership” line, I put a dash. Later, around 1975, when my confrontation with the Soviet communist government was gaining momentum, I was officially expelled from the Komsomol. By a decision of the Komsomol organization of the Kyiv Film Copying Factory—somehow they found out that I had once been a member of the VLKSM. Formally, for non-payment of membership dues. By the way, at the same factory, several other people were expelled from the Komsomol along with me for non-payment of membership dues. That was the easiest way to leave the Komsomol then. The Soviet communist system was already slowly falling apart then.

Let’s return to my letters. Since I touched upon problems of party history, Marxist-Leninist doctrine in those letters, they first forwarded the letters to the city party committee. But they didn’t summon me directly to the KGB. For some reason, they attributed these “overvalued ideas” to me and sent me to the psychiatrists. Not even directly, but through the military enlistment office.

V.O.: As a rule, that’s how they did it—with someone else’s hands.

V.P.: Polishchuk said that everything was normal. I came out, told my mom and aunt that everything was normal, and we went home. And then I needed a certificate for work… An interesting story came out of it. On the one hand, they probably still had reasons to put me in for an examination. So Dr. Zhadanova said: “Don’t go to work for now, stay at home, and we will figure out where to conduct the consultation.” They sent me to Kryzhanivskyi in Darnytsia, then to the Pavlov hospital. I didn’t go to work for about 10 days or more, as they said. Then Zhadanova said that the military enlistment office would give a note that I had been for an examination. I went to the enlistment office, they gave me a certificate there. Zhadanova at first gave me some kind of sick leave note. And I say at the enlistment office: “I wasn’t on sick leave, I was for an examination, so I don’t know if such a certificate is needed.” Well, they gave their own certificate from the enlistment office for my place of work, that I had been for an examination.

And they took my military ID card, then brought it back, gave it to me, without saying anything. I came home and—I don’t remember if it was that day or the next—I thought: why did they take my military ID? I started flipping through it, I open the 16th page and read—in Russian, they wrote everywhere then, even in Ukraine in state institutions—it says that “By the Medical Commission of the Moscowsky RVC, Kyiv, on February 11, 1974, declared unfit in peacetime. In wartime, fit for non-combatant service under Art. 8-B, group 1/224, 1966.” This must be a medical resolution from 1966. I looked at it and thought: no one said anything, but they wrote this.

Then I appealed, I think, to the Ministry of Health of Ukraine: I was for an examination, Professor Polishchuk told me that everything was normal, there were no claims against me from psychiatry, especially since I had served two years in the army, everything was normal—and here such a diagnosis: “unfit for military service”? They didn’t answer me at all. I wrote to Moscow to the Ministry of Health, they forwarded it to Kyiv—there was a whole correspondence. Zhadanova didn’t really say anything to me either—I went to her. My aunt, my father’s sister, asked some doctor acquaintances, and they said that this 8-B means something like psychopathy, that such people cannot be given weapons, which is why they deemed him unfit for service in peacetime, and for non-combatant service in wartime.

I already see that I’m on the psychiatric register, so what to do next? In Kyiv then, of course, there were no foreign correspondents, and I didn’t have any acquaintances to contact someone. I thought, if there is some glasnost, then maybe it would be possible to somehow influence, to review these issues. Nothing could be done. I wrote complaints to various authorities, and one day a paramedic came to me, he seemed to have worked with Zhadanova at first, and then in the inter-district psycho-neurological dispensary, his name was Voziian. And he told me: “If you keep writing, they’ll lock you up in a psychiatric hospital altogether. It’s better to stop all this, because you won’t achieve anything, it will only get worse.”

This was already, probably, in February 1974, it was cold. Nothing could be achieved in Kyiv. I got on a train and went to Moscow. I thought, maybe I’ll meet a correspondent somewhere near an embassy. I walked around like that all day. I had heard somewhere that the American embassy was on Tchaikovsky Street. I walked around it, there were plenty of police, nothing happened to me. I walked around there and returned to Kyiv. I thought, what to do? I need to continue to defend my rights, to fight, to do something.

They summoned me to the city party committee again, this Fedir Ivanovych. He had some letter with a red line on it. And it was written there—I peeked— “Gather information on the author of the letter to the CPSU Central Committee.”

V.O.: Interesting, that it had a red stripe.

V.P.: Yes, a red stripe like that.

V.O.: For example, for a prisoner, a red stripe on the file means “prone to escape.” So were you also considered dangerous?

V.P.: I don’t know what that red stripe was on that paper. He was already old, and he himself had forgotten that he had a conversation with me last time, and he forgot to gather information about me, so he summoned me a second time. He asked who I was, what, who my parents were, where I worked, where I studied.

I thought that the situation was already complicated. Especially since at that time, even before the psychiatric examination, there was such a rise in the cult of personality of Brezhnev, they were already praising him, starting to hang medals on him. I wrote to Shcherbytsky at the Central Committee: what is going on, you are supposedly communists, democrats, you say that you need to learn modesty from Lenin, and what is happening, they have inflated such a cult of personality of Brezhnev, how is this possible, it’s terrible, and people are laughing, they started telling jokes about Brezhnev. And I even wrote that maybe if Brezhnev has become so arrogant, he should be removed from his post, and a more decent person put in his place. This may have been such youthful épatage. But nothing else could be done.

I will, by the way, go back a little. When I learned on August 21, 1968, about the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops… It was right on my birthday, so I remember it very well. Regarding this invasion—when I read about it, I went to see some comrades. But it was summer, and we had returned from an archaeological expedition in the Odesa region at the beginning of August, everyone had gone on vacation, some to a dacha, or to a village to relatives, or went to the Dnipro, maybe. So I didn’t find Horovskyi or anyone anywhere. I walked along Khreshchatyk, but I didn’t see anyone. Maybe if there had been some protest rally, or something, I probably would have joined.

V.O.: You should have gone to Moscow, there was the “demonstration of the seven.”

V.P.: That was later, a few days later, in the evening.

V.O.: Yes, on August 25, 1968.

V.P.: I heard about it later on “Voice of America,” on Radio “Liberty.”

V.O.: You wouldn’t have made it, the demonstration lasted a few minutes.

V.P.: By the way, I recently read that in Kyiv on Khreshchatyk, one man unfurled some poster against the introduction of troops into Czechoslovakia. He just unfurled it—and he was grabbed in literally a minute.

V.O.: And on those same days?

V.P.: Yes, literally on the 21st or 22nd. I read somewhere in the press that such an incident happened.

V.O.: That was Vasyl Makukh. Only he set himself on fire on Khreshchatyk on November 5. He supposedly ran and shouted slogans against the Russification of Ukraine and against the occupation of Czechoslovakia. So that was on November 5, 1968. The student Jan Palach set himself on fire on Wenceslas Square in Prague on January 16, 1969. And Oleksa Hirnyk set himself on fire near the grave of Taras Shevchenko in Kaniv on January 21, 1978.

V.P.: I walked along Khreshchatyk like that, there was no one anywhere. And I was still 17, still a young boy, probably didn’t have the courage yet to write something myself, to speak out. Well, I did write a poem, I read it to friends.

V.O.: Interestingly, in what language did you write?

V.P.: Then, unfortunately, still in Russian, because, you see, I was born in Kyiv, in a Russian-speaking family. Kyiv was generally mostly Russian-speaking then.

V.O.: And your school was Russian, right?

V.P.: The school was Russian, yes. Kyiv was Russified, of course. My father was from Russia. He tried to learn Ukrainian, we had books at home—both *Kobzar* and Ukrainian fairy tales my mother read. My mother was also of mixed origin. So Kyiv was also Russian-speaking before the war. They taught a little Ukrainian in school before the war, so she knew a little Ukrainian, we had Ukrainian books. I read them when I started school. Then in the Russian school, they studied Ukrainian from the second grade.

V.O.: I hear you have such a natural Ukrainian language.

V.P.: Probably some genes from my mother’s side. Somehow I picked it up well, despite the fact that there was nowhere to communicate in Ukrainian in Kyiv. May Leonid Zalizniak, the professor, not be offended, but when he was a young boy, he also spoke Russian. Maybe at home he spoke Ukrainian with his parents. But I don’t know this for sure. I only studied it at school. Since I had already started studying Ukrainian at school, we had Ukrainian and Russian books at home, Ukrainian folk tales, so I immediately read all the books at home, at relatives’, neighbors’, acquaintances’, and signed up for the children’s library—I was about 11 or 12 years old then, then the adult one. I, of course, took any books, as long as they were interesting to me, whether in Ukrainian or Russian. There was also Ukrainian radio, it helped a lot, because on television—even the Dovzhenko Film Studio then made a lot of films in Russian.

V.O.: Some Ukrainian films have only survived in Russian versions, and they are still shown that way.

V.P.: And there was practically no one to communicate with in my circle. I’m saying: there were no such ardent Ukrainian national-patriots that one could join, communicate with. So then I wrote poems, of course, in Russian, although a few poems—I was inspired—I wrote in Ukrainian. In our school (it was Kyiv school No. 110, Russian-speaking), when I was in the 5th grade, there was a good teacher of Ukrainian language and literature. Unfortunately, I don’t remember her name now. It seems to me she didn’t teach us for very long, a year or two, not more. But she organized a Ukrainian literature club at the school. Not very many, but maybe 15-20 students attended this club (this was from three fifth-grade classes, in which a total of more than 100 students studied). We studied the works of Ukrainian writers there that were not in the curriculum, learned to write poems in Ukrainian, participated in amateur performances. So, in March 1964, for the 150th anniversary of Taras Shevchenko’s birth, a festive evening was held at the school. I think, thanks to this teacher. I played the role of the young Taras in a small play. I didn’t have a vyshyvanka, so a student from our class, Valentyn Doroshenko, lent me his (what an irony of fate, that a boy with such a surname studied in a Russian-speaking school, because those were the times). Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska spoke at this evening. I think that our teacher was acquainted with her and invited her. And a few years later I heard on the radio how the Soviet authorities were slandering her for nationalism, for some anti-Soviet actions. Such was our complicated and confusing life in Soviet times.

V.O.: Let’s return to 1974, after the trip to Moscow.

V.P.: I went to Moscow, returned to Kyiv, thinking, I need to do something further, to defend myself somehow. Nothing is working out with psychiatry either. I took an academic leave from the university. I already understood that history, and especially philosophy, were very politicized sciences in our country. I thought, since I’m already on their hook, they are unlikely to let me finish.

V.O.: And how many years did you complete, one year?

V.P.: Only the first year. I think they are unlikely to let me finish, and even if I do, I won’t be able to work against my conscience anyway. If I become a research fellow—I’ll have to write and say what they tell me. Even if I teach at school, I’ll have to teach what is written in the communist textbooks. I thought about this for a long time, and in 1974, somewhere in the summer, I wrote a statement to the rectorate of Kyiv University that since my views had changed greatly, I do not recognize Marxist-Leninist theory, I consider it some kind of myth and an unrealistic doctrine, I wrote that I do not believe in communism, in the construction of an ideal society on Earth. Therefore, I ask to be expelled from the university. Because I understood that it was only a matter of time, they would have expelled me anyway.

V.O.: Interesting, what was the reaction?

V.P.: In principle, there was no reaction, because I was already on the psychiatric register then. There was no answer and, by the way, my high school diploma, my school certificates, documents are still lying there in the archives, if they haven’t been destroyed.

V.O.: And was there an order of expulsion?

V.P.: I didn’t even inquire about it.

V.O.: They didn’t even inform you?

V.P.: They didn’t inform me of anything, I wasn’t interested, the only thing is that I still have a certificate at home for when I submitted my documents—the diploma, two certificates, other things—I didn’t even pick up the documents, somehow it wasn’t the time for that, and then, I thought, maybe something will change. Maybe I should inquire somehow. I don’t know if they are in the archives, or if they destroy them after some time, or if they keep them there forever.

After I found myself in such a situation… And the main thing was that I was alone, there was no help from anyone, no connections, nothing. Sometimes I would hear on the radio that so-and-so was imprisoned, so-and-so was imprisoned, and what to do?

LETTERS

I continued to write, mostly to newspapers—Russian, Ukrainian—critical remarks, responses to articles in a critical spirit. I criticized the Soviet government, the policy, what was being done in our country. I listened to “Voice of America,” “Liberty” on the receiver. When Sergei Kovalev was arrested in Lithuania, I wrote a protest to the prosecutor of Lithuania in support of Sergei Kovalev. Then I wrote letters in support of Mustafa Dzhemilev, when Mykola Rudenko was arrested—I wrote letters in support of Rudenko to the prosecutor’s office, to other authorities—many. Whatever I heard—I responded, wrote, but to distribute it, to give it to someone—there were no such people around me. My friends were even afraid to take these critical poems for themselves, to keep them. Love poems, something like that—I would give them to read, but critical things, of course, they were even afraid to take to keep. Nobody wanted to.

V.O.: Did you write by hand or on a typewriter?

V.P.: By hand. A lot, when you remember all this, it took so much effort and time. Wherever something happened—I tried to respond somehow, to write something.

When they put me on the psychiatric register, they would summon me to the psychiatrist, sometimes to the city party committee, but for some reason, they never summoned me to the KGB. Maybe because I was on the psycho-register. Then I, of course, already saw that the situation was difficult. But I couldn’t do anything here. Time passed, there were no such friends.

Just then, the movement for Jewish emigration from the Soviet Union began. I worked as a lab assistant at the medical school, and there were even girls there, maybe of Jewish origin—their relatives were leaving. I thought that if I can’t do anything here, if there’s no way out, if Jews are going to Israel, then my grandfather was from Sweden, even though I’m of mixed origin—my father is Russian, my mother is also of mixed origin. I wrote, I think, to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, that if in the Soviet Union I cannot freely engage in history, for example, to write a work about the need to dissolve the Communist Party, or, for example, when I was still studying at the university Engels’s work “The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State,” Engels was not as dogmatic as Marx, he sometimes had interesting thoughts. He described how the state arose, that it was not just as Marx or Lenin-Stalin wrote, that exploiters wanted to exploit people and therefore created the state, that the state is an instrument of exploitation of enslaved people. By the way, even in this work of Engels, it is written that the state arose historically, that people at first had a certain community—at first there were tribes, clans, there were separate social functions, a need arose to somehow organize their lives. Therefore, unlike the Marxist dogma that over time, under communism, the state will wither away, I believed that the state might exist forever, or for a very long time, because there will always be some criminals, some other functions will exist. Even if the bodies are self-governing, they will still be bodies of power. It can’t be that large nations, millions, tens, hundreds of millions of people—without any management. There will still be some bodies of self-government. I wrote that I would like to study something in this direction, to research, but here it is impossible, because it contradicts Marxist-Leninist doctrine. Moreover, I wrote that they gave me a psychiatric diagnosis. This is a stain—at work, everywhere. Even if people don’t know what it is, they already look at you as if you are abnormal. Of course, it was very difficult for me. I wrote that if Jews are allowed to leave for Israel, then my grandfather was from Sweden, maybe I could leave for Sweden. I thought that even there I could somehow help the democratization of Soviet society, somehow influence these problems, and I would be engaged in science more freely.

They summoned me to the Kyiv OVIR [Department of Visas and Registration], said: “If you had close relatives there, even then they wouldn’t let you go alone, because you are on the psychiatric register, if the whole family were leaving…” They said a lot of things, made it clear that there were no chances. What was I to do next?

V.O.: What year was it when you applied to leave?

V.P.: It was somewhere at the end of 1974. I continued to work, to write to Soviet newspapers, to criticize the problems that existed, letters in defense, regarding the expulsion of Solzhenitsyn then I wrote. By the way, what’s interesting, when Sakharov was awarded the Nobel Prize, I—unfortunately, I didn’t know his address either—I sent him a postcard. At first, it was spontaneous, so I sent an open postcard to the address of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union and wrote a congratulation, and then I thought that it was an open postcard, it definitely wouldn’t arrive. Then I put it in an envelope and wrote: Academy of Sciences and, I think, I wrote not to Sakharov’s name, but to the name of its then-president, Keldysh, and asked that it be passed on to Sakharov. I don’t know where it ended up.

By then I had left the university, so it was already inconvenient to work in this social sciences department, especially at the medical school. I resigned from there, although they didn’t want to let me go—they saw that I was a decent boy, studied well, even the head of the social sciences department, a front-line soldier and a retired colonel, told me: “We can even give you a recommendation for the party.” I didn’t know how to refuse, I kept wriggling, and then I said that the salary was low here. Because then lab assistants—they say that life was good under the Soviet government—but in 1972-74, I, a lab assistant in the social sciences department at the medical school, received 65 rubles. That was the rate, and from that rate, they took several rubles in taxes—income tax, single person tax, trade union, Komsomol dues, and it came out to about 59 rubles. So life wasn’t so good then either. For example, my mother’s aunt on her mother’s side, now deceased, she died at eighty-five in 1994, Ksenia Afanasiivna Onyschenko, she worked as a nanny in a kindergarten, and in the late 50s and early 60s, her salary was 300 rubles, this was before the reform. If people now receive 300 or 500 hryvnias, the prices are also like that now. But then, after the reform, it was 30 rubles. She was born in 1910, retired at 55. She had such family circumstances that she had to retire in 1965. So she received a pension of 30 rubles, and then a few years later they added, she received 45 rubles for about twenty years. Then later, when prices rose, they added a little. And when the communists say that it was good then, I have to say that people lived hard then. For example, when my father drowned in the Dnipro in 1961, died tragically, the state assigned me and my younger brother a pension of 34 rubles 68 kopecks for the two of us—that’s 17 rubles 34 kopecks per child per month, and you live as you wish. That’s how the communists cared for people.

By the way, back in 2002, before the parliamentary elections, there was a large article in *Holos Ukrainy* by Petro Symonenko with some other communist historian, which was called, I think, “Who is to Blame and What is to be Done?” They wrote there that the Rukh members were to blame for everything, that everything was good before, and they ruined everything. So I wrote a response to this article to *Holos Ukrainy* and described how people lived, what the prices and salaries were, something from my own experience, relatives, acquaintances, neighbors. There were people whose documents were lost during the war, not to mention those who lived in the village: they received pensions of 5-10 rubles. And about those whose documents were lost, and people were already old, there were also those who were 80-90 years old, they worked before the revolution, so that work experience was also lost, the Bolsheviks didn’t count it. And if documents were lost during the war, they received pensions of 9-12 rubles, so they survived as they could. And now they say that everything was good.

Then I was forced to leave my job at the medical school and worked from the end of 1973 as a film developer at the Kyiv Film Copying Factory, because it was close to me. The salary there was also not high, because salaries in general were not high then. I received 100, then 130-140 rubles.

When I wrote a congratulation to Sakharov for the Nobel Prize, I once came home from the night shift and was still sleeping. Someone was ringing and ringing the doorbell. And I, half-asleep, fell asleep again and didn’t get up. And then during the day, my neighbor Vitalii Pavlovskyi, who lived next door and still lives there, came to see me. He was a young boy then and could be a bit of a troublemaker. Someone had rung his doorbell that same morning as mine. He says, I open the door, and there stands a major in a police or some similar uniform. So he thinks: if I did something wrong or drank too much, or got into a fight, it’s unlikely they would send a major for me. And the major asks if Pavlov lives here, in apartment twenty-four. Vitalii answers yes. “And what kind of people are there, who lives there?” So he didn’t say anything bad. Then I thought that this could be related to the letter to Sakharov, because I wasn’t summoned anywhere else. By the way, in the newspaper, I don’t remember exactly, either in *Pravda* or *Izvestia*, right in those days after Sakharov was awarded the Nobel Prize, there was a large article called “To Whom Are Nobel Prizes Awarded?” They mentioned everyone there—some odious figures, to show that the Nobel Committee is such a Western bourgeois organization, it doesn’t give prizes to any good people by Soviet standards. So I wrote to them that a few years before that, Nelson Mandela received the Nobel Prize—he is such a person that even formally the Soviet communists supported and praised him, that he fights for the rights of blacks in Africa. I brought up a few more names in that letter—I tried to react to events, to express my thoughts.

HUNGER STRIKE

This was already 1975. From the beginning of the year, there were rumors that discussions were underway and soon agreements on human rights in Europe would be adopted, there were agreements between European countries. The Helsinki summit of European leaders took place around July 29 – August 1. Right on those days, from July 29, I declared a hunger strike and a strike in protest of human rights violations in the Soviet Union, I wrote about it to various authorities—the CPSU Central Committee, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, some newspapers. I wrote there about the persecution of famous people in the then-Soviet Union, and something from my own experience. Around the third day of the hunger strike, at the beginning of August, the party organizer of the workshop and a woman—the party organizer of the copying factory where I worked—came to see me at first. They asked what was wrong and what the matter was—obviously, some signal had been sent to them. I told them that since the Helsinki conference on human rights was taking place, Brezhnev had signed documents on behalf of the Soviet Union, they promised that they would fulfill all the provisions of these documents, and in the Soviet Union there were human rights violations everywhere, and not just hearsay that I had heard on some radio stations or from someone, but I had seen, understood, and felt from my own experience what it was, what kind of government it was and what it did to people. The party organizer of the Kyiv Film Copying Factory said: “These are your personal affairs. When we go to work, nobody asks us if we’ve eaten or not, so you must come to work, and if you don’t, we will simply fire you for absenteeism. And there will be such an article in your record that you won’t be hired anywhere. So decide for yourself.” I said that for now, I had decided to continue the hunger strike.

V.O.: Did you go to work?

V.P.: No, I didn’t go to work. I declared a hunger strike and a strike.

V.O.: Well, for a strike, you have to be at your workplace, but not work.

V.P.: Since I was on a hunger strike, I didn’t go out. I think I even wrote to the factory administration, and that’s when they came. She talked like that, said that I should decide for myself what to do, and they left. A few hours later, an ambulance arrived. They wanted to take me to Pavlivka right away, demanded that I stop the hunger strike, said that they would force-feed me there anyway. I said that I refused, but I would think about what to do. The bad thing was that even in such a situation, I had no connections and no support.

V.O.: Such things have some effect if there is support.

V.P.: Yes. You see, I didn’t want to live like everyone else, every day from work—to work, and be silent, and endure.

There was such a problem. My grandmother died before the war. Ksenia Opanasivna Onyschenko, my grandmother’s sister, my mother’s aunt—she was like a real grandmother to me, she told me everything—about Jesus Christ, and all sorts of religious things. In Soviet times, when I began to understand and be interested in something more or less, I always wanted to read the Bible or the New Testament, but it was impossible to get it anywhere, it was a problem. Not to mention that if a person wanted to read the Quran out of curiosity, or some other religious texts, or some Western philosophers. For us, everything was presented only in the interpretation of Marxism-Leninism, as they understand it. I simply did not accept such a life, I could not live in such a system, I wanted to turn the world upside down, but you can’t do it alone.

PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITAL

The next day, Dr. Zhadanova came and said: “Well, you won’t achieve anything, because if you continue the hunger strike, they’ll take you away anyway, they’ll give you injections, force-feed you, they’ll only ruin your health, and you won’t achieve anything.” She said: “Think about it. If you stop, then come to my office.” My mother was at work, so I went with my father’s sister, Paraskoviia Illinichna Ivanova. We went to see Zhadanova, and she, seeing that there was no point in talking to me, talked and talked with my aunt, and then they explained to me that since my body was weakened, they cleverly said that somewhere in the direction of Pushcha-Vodytsia there is a psycho-neurological hospital, you’ll stay there for a bit, get some treatment, because your body is weakened after the hunger strike. And they called an ambulance to take me there. When I arrived, I realized that they had brought me to Pavlivka! I don’t remember what number the ward was, it seems they were organized by districts before, those buildings. Some ward, I don’t remember if it was the sixth or the eighth—it was called the rehabilitation ward. And there was also a semi-basement room there, surrounded by a fence and barbed wire. They told me that in 1975 they kept prisoners there who were undergoing forensic psychiatric evaluation. And I was kept on the upper floor.

V.O.: I think the forensic evaluation was the thirteenth ward.

V.P.: Maybe the 13th ward was downstairs. And when I was there in 1975, they didn’t have the new buildings yet. This ward was in the basement. And what’s interesting, a doctor came to me from that basement, not from the ward where I was staying.

V.O.: I was in the 13th ward for forensic psychiatric evaluation in the summer of 1973, and it wasn’t a basement room.

V.P.: It was already new?

V.O.: Who knows what it was like. What did I see there? Only my cell. And under the window—a fence.

V.P.: When I was there in 1983, there was already a new building. And in 1978, they brought me here for an evaluation to this semi-basement room. Maybe only the experts’ offices were there.

V.O.: Maybe—I didn’t see anything there.

V.P.: And then they said that some forensic medical evaluations are also conducted in the basement, and a doctor came to me from there, from the basement. What were the conditions? They gave me some injections. They said it was some vitamins for me after the hunger strike to restore my body. I don’t know if there was anything else there, not just vitamins. They gave some pills, and from these pills, languor, drowsiness, and a kind of indifference set in, you walk around somehow relaxed and almost sleepy. Of course, I tried to somehow take it into my cheek when possible, and then spit it out…

V.O.: And they watch for that.

V.P.: They watched, but sometimes I succeeded, I tried to get out of it somehow. And the light is on 24/7 in the ward, you can’t get a proper sleep.

V.O.: And how many people were there?

V.P.: There were a lot of people. There were large wards with 10-15 men in each. There were different people, but I didn’t meet any political prisoners there. There was one, Oleh Ostroukhov, he studied at Kyiv University, he was interested in yoga, all sorts of Eastern teachings. So they put him in there for that.

V.O.: For “unhealthy interests”?

V.P.: For practicing yoga, vegetarianism, and various exercises—they sent him there. It’s interesting, I don’t know how true this is or not, maybe this information exists somewhere—there was a man there with the surname Shevchenko, what was his first name—Valentyn, I can’t say the name for sure—he was already, probably, almost 50 in 1975. He said that he was supposedly a descendant of Taras Shevchenko through his sisters. He said that they lived in the building where the SBU, the former KGB, is now, or next to it, where there is also an SBU building now, an old building—somewhere on that spot, as he said, it was built, of granite. His mother was some kind of employee—a local historian or something like that. Because when the war started and there was an evacuation, he was still a young boy, they traveled in echelons to evacuate with these valuables somewhere to the east—his mother was a research fellow. They were bombed by planes, he was slightly shell-shocked. After the war, on the basis of this shell shock, he sometimes had sad moods. After the war, he worked on repairing some road—then they sent young people, Komsomol members. He says that it was hard and hungry, and cold. He went to his foreman and said that it was so hard and difficult for him that sometimes he wanted to throw himself under a train, because he had no strength to endure after this shell shock. And the foreman immediately sent him to a psychiatrist, they gave him some diagnosis, and now he has this diagnosis for life and can’t get rid of it. He wasn’t kept in the hospital permanently, but he had to voluntarily come once a year, supposedly for a re-examination or a re-commission for a month. He said he lived somewhere in Darnytsia. He said that in the seventies, national-patriotic organizations in Canada wanted to take him, but it didn’t work out. He had such democratic views. He said that somehow he had to survive and endure all this. I don’t know how true this is or not: he said that he was from the family of Taras Shevchenko (a descendant of one of his sisters).

But there were no political prisoners like that.

V.O.: And how long did they keep you there?

V.P.: I was there for a month. They gave me pills, gave me injections…

V.O.: And were there any consequences? What was the conclusion?

V.P.: They asked me every time what I would do next, how I would live—they were interested in that. I told them I would work, and we’ll see what happens next. I was there for about a month. They didn’t let me out on my own. It was difficult for my mother to leave work, so my father’s sister, my aunt Ivanova, came and took me from there under her signature. That was 1975.

In 1976, I think, when information about the creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group began to spread on Western radio stations, of course, I wanted to somehow join this or get in touch with these people—the organizers and participants. I asked friends, acquaintances…

V.O.: Did they broadcast Oksana Meshko’s address on the radio? 16 Verbolozna Street?

V.P.: I personally heard about Verbolozna only when perestroika began, when I returned from prison. But then—I don’t know, maybe I just missed it, because they jammed it terribly, especially the Ukrainian service—not so much the Russian service as the Ukrainian one. For the Russian one—you could sometimes hear something.

V.O.: Yes, and they jammed it especially in the city. In the provinces, it was somehow easier.

V.P.: Well, I didn’t have anyone I could go to. I listened mostly in the city, and they jammed the Ukrainian service terribly. You could hear something around two or three in the morning.

V.O.: In 1977-78 I was at home, in the village, so I mostly oriented myself in the situation through the radio. In the village, of course, it was easier.

V.P.: An interesting story happened. I once borrowed Mykola Rudenko’s poems from the library, read his poems and his fantasy works with a subtext of criticism of the personality cult. I read his “The Magic Boomerang” as a teenager, read his wonderful poems. And I thought—there were information bureaus in Kyiv then, booths on every corner—I didn’t even know Rudenko’s year of birth and didn’t know if they would give information about him at the information bureau. I once took a book of his poems, and there he wrote in a poem that in 1941 he was 20 years old. And I roughly thought that he was born in nineteen-twenty or twenty-one. This was already, probably, 1976. I went to the information bureau, writing that it was Mykola Danylovych Rudenko. They didn’t give it to me for a long time, asked me to come back in an hour or later. They gave me an address in Koncha-Zaspa. But you see, like any average Kyiv resident, I had the impression that only the “big shots,” the party bosses, live in Koncha-Zaspa. I thought it might be some kind of trap. Who knows if he lives there. Especially since I knew that he was already in disgrace, expelled from the Writers’ Union. I thought, you’ll go there—and maybe some KGB agent lives at this address? I had never been to Koncha-Zaspa, how to get there—maybe there’s already some checkpoint where a policeman stands and watches who enters and leaves? Will they even let me into that settlement where the bosses mostly live? And will they let me to this house, or is there a policeman or a plainclothes KGB agent standing by his gate? I was thinking about it like that, and I had already looked near the bus station, I think bus 41 went to Koncha-Zaspa. And I was still thinking of going there at least for reconnaissance. But while I was thinking like that, they had already reported that Rudenko was arrested. I wrote a letter to the Prosecutor’s Office of Ukraine in defense of Rudenko. By the way, this letter is in my criminal case file. And again, I couldn’t make contact. What to do?

V.O.: This is 1976-77, and you were arrested only in eighty-three?