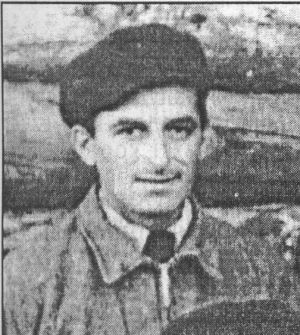

Interview with Bohdan Vasylovych Hermaniuk

V.V. Ovsiienko: February 9, 2000, the city of Kolomyia, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, Mr. Bohdan Hermaniuk. Recorded by Vasyl Ovsiienko.

B.V. Hermaniuk: Kolomyia is in the foothills, a place where everything gathered for the struggle for the national idea, for the national cry, “You will win a Ukrainian state or you will perish in the struggle for it.” And so, at a young age, after our studies, most of us not yet married, we made this call the main goal of our lives, because Ukraine had suffered for centuries.

The history of our people is very long and sad. We know that Ukrainians are a hardworking people who love to live by their own labor and raise their generations. Our people never sought to conquer anyone; they only defended our land and our ethnographic territory of Ukraine. But Ukraine was fragmented by our neighbors, who tried to grab as much of our land, our territory, and our people as possible, because our people were exceptionally hardworking.

Ukraine is a large piece of Central Europe; it had many neighbors in the center of Europe who coveted Ukrainian lands and the Ukrainian people. That is why from the very beginning of our studies, we tried to read as much old literature as we could, which people kept illegally and hid from all kinds of occupiers. That literature raised us to such an ideological height that from a young age we decided to fight for the independence of our Fatherland, our people, our nation.

Our parents advised us that we must fight, but we must fight very carefully and with great secrecy. Therefore, our organization decided to gather people who could fight for their independent state, for their people. We are members of an organization called the United Party for the Liberation of Ukraine (OPVU). It set a goal to have its own statute, its own ideological foundation, and to lead the struggle, because Ukraine, as a central European state, was supposed to lead the struggle for the liberation of all peoples enslaved by the red Moscow empire.

V.O.: Mr. Bohdan, could you state your date of birth, where you were born, who your parents were, so that we have biographical data about you.

B.H.: I said we should have made a plan…

V.O.: Please state your name and date of birth.

B.H.: I was born in the village of Piadyky, Kolomyia Raion, in what was then Stanislav Oblast. I was born on August 20, 1931. My parents were farmers. I still remember my parents’ land, which we cultivated and lived off of. My father was a minor official; he was a field warden, elected by the community. And my mother was a homemaker.

My father was Hermaniuk (with a hard ‘G’ sound, as in Ґерманюк, not with the soft ‘H’ sound the Soviets say), Vasyl Yosypovych, and my mother was from the Palii family—Palii, Hafia. Also Yosypivna. My father was born in 1900, and my mother in 1905. Both are now buried. My father died in 1951, and my mother died in the village of Piadyky, where she is buried in the cemetery.

V.O.: And where did you study?

B.H.: I studied at the Chernivtsi Industrial Technical School. Well, first I completed seven grades at the Piadyky secondary school, and after the seventh grade, I enrolled in the Chernivtsi Industrial Technical School.

After graduating from the technical school, I was sent to Ivano-Frankivsk for work. And why was I sent to Ivano-Frankivsk? Because when I was studying at the Chernivtsi Industrial Technical School, my mother lived in the village with my younger brother. I wasn’t able to visit very often because money was tight; there wasn’t any. After my father’s death, my mother lived on a portion of his pension. It was difficult for us with food and with travel to my studies and back home.

And from all this, my mother had a mental breakdown. At the culminating point, she started hacking at herself with an axe, but my little brother, Yosyp, ran up to her, and she started hacking at him. The neighbors ran in, saw this tragedy, and took the axe from her. She had split the little one’s face open like this. They took her to a psychiatric hospital. I was studying at the time, already taking my state exams, and knew nothing about this. My cousins, Mykola Palii and Dmytro Palii, came to Chernivtsi and told me about the situation at home. I then defended my diploma and immediately went home, because I didn’t know what was happening there.

When I arrived home, my mother was in the psychiatric hospital, and the little boy—he probably wasn’t in school yet, he was about five or six years old—was with my mother’s sister, who lived nearby. When I found out what had happened at home, I went to the psychiatric hospital and started talking to the doctors. The doctors promised me that I could take my mother home, but I had to sign a waiver stating that she could live under my supervision. I had to sign this waiver.

When I returned to Chernivtsi, because I still hadn’t passed all my state exams, I explained my situation at home and asked to be assigned a job closer to home so I could look after my mother. They then gave me a job in Ivano-Frankivsk, and I was able to visit home in Piadyky every Sunday and monitor how my mother was behaving.

After my mother was behaving well, it was then that the idea of creating the organization, the “United Party for the Liberation of Ukraine,” arose—to ease the lives of mothers and fathers like our own. We decided to create a party that could protect our people from the occupiers who tormented us, who did not let people live—people lived on meager kopeks, which led to tragedies like the one that happened to my mother.

V.O.: Tell us about your circle, how did your organization come into being? Who was the initiator, who were these people?

B.H.: I was the initiator. But in fact, I had a cousin, Bohdan Rubych, who served in the ranks of the Moscow Red Army. He was an exceptionally capable person, a talented artist. He could draw with a pencil in such a way that… I have a photograph of one of his drawings somewhere. If I had known, I would have brought it to show you… He served in the army in Leningrad. When he went home on leave, he never returned to the army but instead joined the underground UPA. He was the one who gave me the impetus; he gave me instructions on how to work so as not to get arrested. That’s why we maintained great secrecy; everyone had an alias, so if someone got caught, they couldn’t betray everyone, not knowing their real names. I was “Bohdan Khmel.”

Our party decided to conduct agitational work among the population, because the Constitution stated that every republic had the right to secede from the USSR. That is, from the red empire. Because it couldn’t be called anything else; it was just a red empire. We decided to carry out such agitational work and call upon all of Ukraine, our entire Ukrainian people, to struggle: believers, intellectuals, workers—we intended to involve everyone in this struggle. In addition, we intended to contact other republics: Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Georgia. We understood that we had to fight together, because neither Ukraine alone, nor Belarus, nor Georgia—no one could achieve liberation on their own. But if we all fought together, the Soviet Union would not be able to stand. That is why the idea was born among us to unite all the republics and our entire Ukrainian people to fight for an independent Ukraine.

V.O.: How did you manage to create the organization? This is the most interesting part—who was it composed of, what kind of people were they?

B.H.: I have photographs of these boys here. Each one of them harbored a hatred for Moscow and a feeling that no matter how much Moscow tormented and killed, it couldn’t kill and torment everyone, because young people remained, students—some were studying, some were working—that these people would eventually prevail and create such a united party that would fight for independence. Every republic should fight for its independence, and Ukraine all the more so, because the Ukrainian people are the largest; it is a great, intellectually developed nation. It must fight for its independence, no matter how much the enemy scares us, no matter how much it subjects us to torture. And, sooner or later, Ukraine must become free. We decided that Ukraine should become the nucleus that would lead the struggle for Ukraine and for the independence of other republics.

V.O.: You say, “We decided, we set goals.” But still, how did you come together? How did you create the organization?

B.H.: We came together very simply. We were all like-minded. For example, I knew Myroslav Ploshchak as a fellow villager who went to school with me. Vasyl Ploshchak is Myroslav Ploshchak’s own brother. They and their parents had also suffered from the red terror. Ihor Tkachuk was from a neighboring village, Hody-Dobrovidka. He was also set against the red empire. That’s how we selected our boys, who shared the same mindset. That’s why we gathered from all over the raion and the entire oblast. We didn’t just meet in Piadyky—we met in Vyhoda, we met in Dolyna, we met in Kolomyia by the Prut river… Each of us had a friend in mind whom he considered a possible candidate for our organization. Everyone had that right. When someone proposed a candidate, we discussed it and decided at a meeting whether to accept him. When we decided he was suitable for our organization, we would call him in and tell him what his goal and task would be, and whether he wanted to fight. If he didn’t want to fight—if he was afraid or said he didn’t want to—we would simply tell him: “Please, you are free to go; no one has said or will say anything bad to you. But if you want to fight for Ukraine, for our independence, then please join us. Know that we will take an oath, and the oath will be sworn in blood. And once you have joined the organization, you must be a pure member of the organization.”

V.O.: When did the organization begin its activities?

B.H.: Our organization began its activities in 1955. By then, it was already operating as a fully-formed entity, but we ourselves had been gathering as early as 1948. And in 1955, it was already an organization that was fighting.

V.O.: What specific actions did you take?

B.H.: We conducted agitation among the population, explaining how rich and strong our country is. If we unite—the intelligentsia, the workers, and the clergy—we will have great strength. We explained this to every acquaintance and relative. That was the kind of agitational work we did. We had our own statute, our own program, which called upon the entire nation to fight for its independence, for freedom.

V.O.: And who was the author of the statute and program? How was it done?

B.H.: The authors were Bohdan Tymkiv and Ivan Strutynsky—they were our ideologues. And Vasyl Ploshchak—he was a teacher of the Ukrainian language at the time. He did a lot of that kind of intellectual work.

V.O.: Did you publish leaflets or any other publications?

B.H.: We did.

V.O.: How was it done? On a typewriter, by hand?

B.H.: Not on a typewriter… We had a plan—maybe it was impractical, but we had in mind that we needed to steal a typewriter from somewhere to print these leaflets. So that was also one of our goals. And the goal was to distribute these leaflets in other republics, not just in our own.

V.O.: Did you actually establish contact with any organizations outside of Ukraine?

B.H.: We hadn’t managed to do that outside of Ukraine yet. First, we wanted to have our literature, to have the statute and program printed, and then with this statute and program, we could go to other republics so they would have an example of how to conduct the struggle.

V.O.: And were the statute and program adopted at meetings, were they discussed?

B.H.: Yes, absolutely.

V.O.: How and where did that happen?

B.H.: It was in Kolomyia, by the Prut river—we read the statute aloud there.

V.O.: What year was that, what season was it?

B.H.: Our work was usually carried out in the summer. In the winter, we more or less worked on ourselves. We tried to gain more knowledge so that each of us could persuade and re-educate a person who wanted to join our ranks. We tried to ensure that this person was conscious of what they were getting into, that they knew what they were committing to.

V.O.: So, you conducted propaganda for several years?

B.H.: Yes.

V.O.: Were there any setbacks, any failures?

B.H.: There were no failures, but there were provocateurs in our midst. They were Mykhailo Cherevko and Myroslav Myslovskyi. These two were possibly sent to infiltrate our organization. They were both former political prisoners who had been released from prison. I spoke with them, and they seemed like normal people, especially since they had been in prison. No one could have suspected that they would carry out such a provocation.

So what did they do? We had a secretary, and we had liaisons. They instigated our secretary—Petro Haiovyi, who worked in Broshniv (the village of Broshniv)—the secretary was keeping the oath that we had signed, where we had sworn in blood. They incited him, Haiovyi, and Mykhailo Kozak was also involved in this, and they took this oath and handed it over to the KGB. They handed it over to the KGB themselves. And for all the time we had been working, no one had been able to tail us, because we operated with great secrecy, setting up lookouts when necessary. Depending on the conditions: in the summer, we would undress somewhere near the river to make it look like we were swimming, so that no one would follow or approach us.

So they arrested...

V.O.: When did those arrests take place?

B.H.: That was in 1958.

V.O.: Specifically, when were you arrested?

B.H.: I don’t remember the date. In 1958, sometime before Easter. But I can’t say the exact date.

V.O.: Were you all arrested at the same time or little by little? How many of you were there in the raion?

B.H.: There were already up to fifty of us in the organization throughout the oblast. Nine of us were put on trial.

V.O.: Nine? It says here eight people (Ihor Mardarovych. Holos pamiati // Visnyk Kolomyi. - No. 63 (457), 1994. - November 10.). Not all the photos are here. It lists: Bohdan Hermaniuk, born 1931; Yarema Tkachuk, 1934; Bohdan Tymkiv, 1935; Myroslav Ploshchak, 1931; Ivan Strutynsky, 1937; Mykola Yurchyk, 1933; Ivan Konevych, 1930; Vasyl Ploshchak, 1929. Eight people are listed here. But nine were tried?

B.H.: No, it was probably eight of us who were tried.

V.O.: And where was the investigation conducted?

B.H.: In Frankivsk.

V.O.: Under what circumstances were you arrested, and how was the investigation conducted?

B.H.: The fact is, I was arrested last because I was working in Frankivsk at a brick factory. The boys were already in custody, and I didn’t even know they had been arrested. When they arrested me, my goal was either to hang myself or to do something to end my life, because I thought that Myslovskyi and Kozak had sold me out. I thought they had sold me out, and that all the other boys were still free. I was held alone in a death row cell, and when the investigation was almost over, they planted an informant. He pretended to be guilty and started messing with my head. I got so angry—I don’t know where I got the strength—I grabbed him and threw him into the latrine bucket, and they took him away from me immediately. That was after the investigation.

They arrested me, and I thought I was the only one in custody. So I decided I had to find a way out of this situation. I had heard many stories about the tortures they used. I thought, maybe I won’t be able to withstand it. So I thought I had to find a way out. And just then, as if by a gift from God, they took me to the bathhouse, and someone was washing there. They brought me in—here’s the bathhouse, and here’s a small room. The guard brought me in and locked the door from the other side. Someone was washing in there. When he came out, I was supposed to go in; the guard was supposed to let me in. But somehow, I don’t know by what miracle, I stuck my fingers in, turned the lock—and the door opened. And there was Yarema Tkachuk, washing. He told me that all the boys had already been arrested. I knew nothing. Only then did I realize that there was no way out. I took all the blame on myself. I took the blame because during the arrest, they had confiscated the statute, the program, and the text of the oath. I thought, that’s it, I’ll take it all upon myself—that I alone prepared the oath, I alone prepared the statute, I was the ideologue. I took everything upon myself. But when he said that everyone had been arrested, I thought, there’s nothing more to say. It was clear that now we all had to stick together. What everyone else said, I said too.

Well, then we started passing notes during our walks, making little balls of bread and throwing them. And we more or less made contact, we could more or less coordinate what to do, how to act.

The situation developed in such a way that the judge and the prosecutor demanded the death penalty for me. The trial was closed; no one was allowed in. When the trial was proceeding, the prosecutor demanded the death penalty for me. The court went into deliberation. When they returned from deliberation, they said that everyone… Tymkiv took the blame, Ploshchak took the blame, Strutynsky took the blame, and I took the blame. And they got confused, didn’t know how to sentence us. (Laughs). So they gave me, Tymkiv, Strutynsky, Tkachuk, and Myroslav Ploshchak ten years each, and Yurchyk and Konevych got seven years. We tried to protect Vasyl Ploshchak. We all took the blame on ourselves, saying he was not guilty, that he didn’t know it was a nationalist organization. That he didn’t know. We were shielding him so that someone would get out free. Since we all shielded him, they gave him two years. So we deliberately saved him. At the trial, I said that Vasyl Ploshchak was not guilty. They said, “And what if he had reported you?” And I said, “We would have executed him. We would have killed him. He didn’t know; he ended up there by accident.”

When the investigation was almost over, about twelve of them arrived, those Chekists, KGB agents. They sat me in the middle of the room. I’m sitting, they’re sitting around me, and each one asks me a question. I answer calmly and feel someone staring at my face so intensely that it burns, that it makes me feel unwell. But I answered each one slowly. For example, they asked, “So, you wanted Ukraine to be independent?” I said, “Of course, we wanted that. Why,” I said, “can other nations have their independence, but our 52-million-strong Ukrainian nation cannot have its independence? Especially,” I said, “since it’s in the Constitution that every republic has the right to secede from the Soviet Union. So why don’t you give this opportunity to a people who want to be independent, why do you hold them back?” And so it went with each one. I don’t remember all the questions they asked me, but each one around the circle asked me a question. After that, they stopped the investigation. They took us to trial.

All of us were arrested. And those who were not arrested served as witnesses. There was Roman Arsak, Myron Kostiuk, Mykhailo Kozak, Petro Haiovyi, Nazaruk… Twenty-eight people were questioned at the trial. They were witnesses, while the eight of us were the ones arrested and punished.

V.O. (Reads): “The first arrests took place on December 4, 1958. At that time, 28 people—members of the organization—were arrested and interrogated. Of course, not all were tried, as some of them served as witnesses and—it is written so—agreed to cooperate with the KGB.”

B.H.: Yes. Yarema Tkachuk wrote a book; he has a manuscript of 240 typed pages. But the thing is, we don’t have the means to publish it. (The book was published: Yarema Tkachuk. *Bureviyi. Knyha pamiati*. - Lviv: Spolom Publishing House, 2004. - 368 pp.).

V.O.: He wrote a book about this organization, correct?

B.H.: Yes. 240 pages. I have a part of it.

V.O.: But it’s good that he wrote it. Once it’s written, it exists. At the very least, it will be in an archive where it can be consulted. If you manage, perhaps you’ll publish it someday, because what isn’t written cannot be published, but what is written might one day see the light of day.

B.H.: After the trial, they put us in a Black Maria, in a “Stolypin car”—and off we went through the transit prisons. They took us to Ozerlag, in the Irkutsk Oblast. In Ozerlag, they threw us into a punishment camp. Of course, they didn’t keep us all together. I, that is, Bohdan Khmel, was with Myroslav Ploshchak and Mykola Yurchyk. We were in one punishment camp, and the others were sent to different ones.

What was so bad about the punishment camp? The water in the zone there was very bad. It had some kind of aftertaste, some kind of smell. That was in the residential zone, and in the work zone, across the wire, there was a bakery that baked bread for the nearby settlement. The water there was good. But they wouldn’t let us drink that good water; they gave us this rotten stuff instead.

There I met Mykola Kostiv, Myroslav Symchych, Zenko Karas, Petro Duzhyi…

V.O.: And was Volodymyr Hrobovyi there?

B.H.: He was, he was.

V.O.: And was Yuriy Lytvyn there?

B.H.: Lytvyn? I don’t seem to remember. After that camp was liquidated, they sent us to different camps: to No. 11 in Taishet, to No. 7, seven-one. In those camps, there were more people, and we could communicate more. There we became familiar with the conditions in those camps. Construction brigades were led to work, transported by truck. After that, they cut our rations for purchases in the camp store: we were allowed to buy only five rubles’ worth of goods. The rest of the money, whoever earned it or had it, was put on a savings book.

After that, they restricted our correspondence. We were only allowed to send three letters a month. With this, they aimed to make some people break and go into cooperation with the camp administration—to become snitches, informers, so they could buy more at the store and get unofficial correspondence privileges.

In addition, they organized amateur activities in the camps, that is, a choir, and they put on concerts. Those who cooperated with them and were members of the choir were given an extra-sessional visit if someone came to the camp. But in some cases, the boys also put on their own concerts, that is, they staged patriotic plays.

After No. 11, they took us to the punishment camp No. 17—that’s where I was released from in 1968.

V.O.: Where is No. 17?

B.H.: That’s in Mordovia.

V.O.: And when were you transferred to Mordovia?

B.H.: After the incident when the prisoners refused to go to work, they moved everyone from that punishment camp to Mordovia.

In camp No. 17, Hryts Pryshliak, Omelian Pryshliak, Yevhen Polovyi, Mykhailo Soroka, Levkovych—the colonel, Danylo Shumuk, and Zenko Karas were imprisoned.

V.O.: And what was the work in camp No. 17?

B.H.: In camp No. 17, we sewed gloves on electric sewing machines.

V.O.: I was in No. 17-A in 1975-76, also sewing gloves.

B.H.: They sewed both these work gloves and the kind with fingers.

V.O.: Do you remember your release date?

B.H.: 1968, in December.

V.O.: Were you released directly from the camp, or were you escorted home?

B.H.: From the camp. There was no train beyond that point. It was the last station. They gave us money for tickets. We got our tickets and were on our way…

V.O.: Were you traveling alone or was one of your colleagues with you?

B.H.: I was traveling with Myroslav Ploshchak.

V.O.: Where did you return to?

B.H.: To Kolomyia, here, to Piadyky.

V.O.: Did you work anywhere after that? Was there any persecution from the KGB?

B.H.: The persecution was constant. They would summon me two or three times a week. Not every week, but they would summon me to cooperate, promising an easy job, that they would let me study. Whoever wanted to study, they offered it.

They took me and Ihor Kichak to Frankivsk. We had two years left on our sentences then. They brought us here, to Frankivsk, for re-education. They brought us, summoned my mother. They made her bring a package—specifically to let me see my mother, to get me to cooperate with them, then they would let my mother have a visit, and pass on the package. And if I cooperated with them, they might release me home two years early. But we didn’t take those packages, we didn’t have the visit, and so we went back. They took us back to the camp, and we served out the rest of our terms in the camp.

I couldn’t start a family because my mother was incapacitated; she received that tiny, meager pension. It wasn’t enough, and I had to go to work. At first, I worked at the brick factory in Pechenizhyn. After Pechenizhyn, I worked in Kolomyia at the consumer services center as a construction foreman. But since the KGB wouldn’t leave me in peace, always trying to get me to cooperate with them, we decided it was better to get out of their sight and take construction jobs on contracts. I worked in the Mykolaiv region, mostly in Mykolaiv Oblast. We built cowsheds there, residential houses, a pigsty. You could earn a little more there because the KGB didn’t persecute you as much. I could finally help my mother. We worked, because one has to work in this world. There was no time to think about a family or relatives. I had to live like that, on faith.

V.O.: You were born in 1931, so you’re 69 now? When did you retire? You’ve forgotten… Well, that’s not essential. I’ve written down your address and phone number. But please state it here as well, let it be recorded. What is your address in Kolomyia?

B.H.: The address is: 1-A Bohdan Khmelnytsky Street, apartment 105, 2nd entrance, fourth floor.

V.O.: No phone?

B.H.: No. You already know my location. Next is Yarema Tkachuk: the village of Popovychi, Mostyska Raion, Lviv Oblast. Bohdan Tymkiv: Ivano-Frankivsk, street… I don’t know its new name, number 1. Myroslav Ploshchak: the village of Piadyky. Ivan Strutynsky: he died, poor fellow.

V.O.: And where did he live, where did he die?

B.H.: He lived in Kalush, worked there at a factory.

V.O.: What year did he die?

B.H.: I can’t just say what year. Mykola Yurchyk is in Mizyn. That’s in Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Dolyna Raion… no, not Dolyna. (M. Yurchyk lived in Broshniv, Rozhniativ Raion, then in the village of Vyhoda, Dolyna Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast.). I’ll have to write it down accurately. Then there’s Vasyl Ploshchak, also in Piadyky. And Konevych—I don’t even know where he is. After he was released, he left, and that was it. Maybe Tymkiv knows, I’ll have to ask him.

V.O.: Maybe someone knows. Thank you.