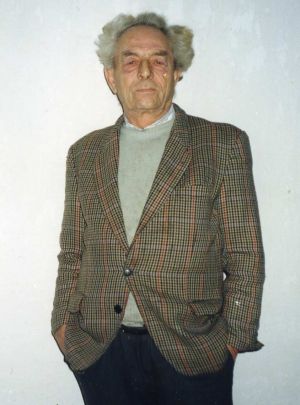

An Interview with Vasyl Lutsevych PIRUS

(Present: wife Anna Pirus and Vasyl Kulynyn)

V.V. Ovsiyenko: On February 20, 2001, in the village of Nyzhni Torhayi in the Kherson region, we are speaking with Mr. Vasyl Pirus.

V.L. Pirus: I am Vasyl Lutsevych Pirus, born July 22, 1921. My father went to Canada when I was six years old. My mother stayed behind with the four of us.

V.O.: What was your father’s name?

V.P.: His name was Luka Pirus.

V.O.: And your mother’s name too, please.

V.P.: My mother’s name was Nastia.

V.O.: And what was her maiden name?

V.P.: Sarakhman.

V.O.: And where were you born? You didn't say.

V.P.: The village of Zaryvyntsi in the Buchach Raion, in what is now the Ternopil Oblast.

I spent my childhood years without a father. I went to school for six years but learned nothing. It didn't seem necessary to me because I was an awfully wild child. Just mischief and more mischief; nothing else interested me. But I did play the accordion. I learned how. I played very well. Later, I played the banjo. That’s how my childhood passed.

I grew up. People from our village were emigrating to Argentina, to Brazil. And here’s something that I remember very well. I left the house and saw a large crowd of people. I ran over to them. They were heading to the cemetery. I followed them. At the cemetery, I saw them fall upon the graves and weep bitterly. They just cried and cried. They cried so much that we children began to cry along with them. And over the graves, they would say, “We will never see you again, we will not pray for you, our tears will no longer fall upon your graves”—this is what the emigrants said, speaking for a long time to the dust over the graves. From there, they went to the church. They crawled on their knees all the way to the altar. They kissed the altar there, kissed everything—and as they left, they kissed the ground and the thresholds: “Here I was baptized, here I was married...” and she fainted. They took her home. She dug up some earth from under the threshold, put it in her bosom, took an icon of the Mother of God, and carried it out into the yard. She turned back, fell onto the threshold, kissed the threshold, kissed the doors, and went to the window shutters. And I walked around watching, you know, a child, a little boy. She went to the gate, leaned on it, kissed it, and wailed, “I will never open you again.” And she fell with that icon. How that image didn't shatter... they picked her up there. They went to the river. It was ten meters to the river. They gathered stones, polished over millions of years by that river. As a memento, like a relic. They washed in the water, drank that water, and filled a bottle to keep as a memory. They were led to a wagon. The people—the whole village—were saying goodbye. When they were leaving, the village bells began to toll. Everyone started to cry, and I cried too. My mother took me by the hand. They drove off, and we went up the hill toward home.

As we walked home, I asked my mother why they were leaving their village. And she said, “Because, child, we have no life here. The Poles took our lands. Half the lands were taken for the *filvarky* [large Polish estates], and then the Poles took more, and then the Jews, and then all sorts of colonists. And on our own land, instead of carrots, we have turnips. So they go to foreign lands in search of soil.”

Then I asked my mother, without any hesitation, “Why don’t we drive out the Poles?” She replied, “We tried, child, we tried. Your two uncles—I had four uncles who fought with the Sich Riflemen—two were killed, two returned home. We couldn’t drive them out, because the Muscovites were pushing from Odesa, and the Bolsheviks were pushing from the north, and the Poles from the west, the Romanians were grabbing their piece, and we could not stand our ground.” And I, like a beaver slapping its tail on the water, blurted out, “When I grow up, I will drive out the Poles, and our lands will be ours.” And my mother bent down and kissed me, “May God speak through your words, child.”

And that was it. We turned around: the wagons were already disappearing over the hill. We waved, and they saw us and started waving back. Then they were gone. My mother started crying and said (my father had desperately wanted to take us to Canada, but my mother refused to go), “You see, son, that’s what awaited us if we had gone, and we probably would have never come back here. But I don’t want to leave my family’s graves. I’d rather go begging with a sack than go to a foreign land.” And so, with my childish mind, I made a vow to myself then and there. It all settled in my mind that I, too, would never go anywhere away from my homeland. And when the Germans came, there was a golden opportunity to go with them: my father was in America, I could get there and go... and I would be... No! I felt it would be a shame. I never even... such a thought never even crossed my mind.

And so I grew up. The Bolsheviks came. People greeted the Bolsheviks with flowers. Everyone, that is, except the wiser ones. But the rest of the people came out: “Our brothers are coming! We’re rid of the Poles, of the Polish eagle!” I went too. You know, organically, I could not look at that army. I just couldn't stand them, and that was that.

And then, a few weeks later, what the wise people had expected began. The Bolsheviks established new prisons. Arrests began at night. They would drive up and take away completely innocent people. A man might never have said a thing against the Soviet Union, not even have been in an organization—they just took them, and that’s it. And those who were taken... to this day... All of them were shot in the prisons.

V.O.: So that was in 1939?

V.P.: Yes, in 1939. In 1941, the Bolsheviks flee, and the Germans arrive. I’ll tell you, let people say what they want, but I was a supporter of the Germans. And I remain one to this day. And for me, Hitler is a saintly man. If it weren’t for him, not a root of our people would have remained in Galicia, and if any had remained, they would have been only communists, as everyone else would have been deported, shot, and tortured to death by the Bolsheviks. He saved our people. And he allowed us to create... If it weren’t for Hitler, we wouldn't have created the UPA [Ukrainian Insurgent Army].

V.O.: Yes, that's how it turned out.

V.P.: I’m telling you this from my perspective, as I understand it. He is our savior, he was our ally. Later, when they declared independence, he soon arrested Bandera. His brothers were arrested. They were hanged, put in concentration camps, killed. The brothers were killed. So our people went to fight the Germans. Such fine boys were killed, so handsome, so comely! So... so much so that it's painful to remember them. And you ask, what did they die for? They died for nothing. Why did we need to fight the Germans? Let the empires fight him, he’s shaking them up. But why should we fight the Germans? Just sit tight, give him a wide berth. Create your UPA, create your combat units, your detachments, and so on. Why fight? I always said this, even to the KGB agents in the camps. And they said that at least one person admitted that we were allies. And I’d say, “You were more their allies than we were, because you were feeding the Germans before the war, you started the war together with them—you attacked Poland, and then one of you went for Denmark and Belgium, while the other went for the Baltics. One went for Norway, and you went for Finland. One went for France, and you went for Romania. And then you couldn't divide the world between you. So you were the allies, much more than we were.”

Under the Germans, the national movement rose up, the national idea became so rooted in people’s souls that it was sacred. On top of that, news came from Volyn: they had defeated the Germans here, defeated them there, there was freedom over there, no more occupiers, there were battles with the Bolshevik partisans, with Kovpak. Finally, the Germans are retreating. And I could have gone with the Germans. And other boys went and called me to come. But I didn't go.

There was an evacuation; we had a front line here. Right after the Germans left and the Bolsheviks came, rifle battalions were organized. In the neighboring village of Pidzamok, there were Poles. And in our village, there were Poles too. And they began to inform—who was where, what was what. At night, the Poles attack our village. We are already in the partisans. I came home just as it was getting dark. About nine or more of the boys came into the house with me. My mother was going to milk the cows and she stood in the doorway with the pails, turned around, and for some reason stared at me for a long time. I felt something, wondering why she was looking at me like that. She went to the barn, and then the neighbor’s girl runs up and says, “Boys, the Poles are coming!” “From where?” “From Pidzamok, from Zvenyhorod.”

We immediately ran to the woods to face them. But they went around the woods. In the forest, they found my father-in-law (he was gathering firewood there)—they killed him. Two boys were hauling manure there—they killed them too. They were from my family. They came from the other side of the village and started burning it down. We were rushing back and forth. A battle began. We had to get past walls, we needed grenades to throw over them. I had a “desiatka.” Do you know what a “desiatka” is?

V.O.: No.

V.P.: A Russian ten-shot automatic weapon. The casing extractor broke on it. Next to me was a young boy (he's still alive), Mykhailo Mykytyshyn. He was so scared, shaking like his rifle. I took that rifle, and we pushed the Poles back to the ditch. When I got back to my own people, I looked and saw everything was burning—smoke everywhere, everything on fire. I looked down and saw a body burning at my feet. I turned the body over—into the snow to put it out. I didn't even know it was my mother. It was my mother who was burning. They had killed her before that. They’d thrown grenades into the house; I heard squealing in the entryway, so I ran to fight them off. And then I hear the command: “Forward!” And we went, we pushed forward and drove them back to the cemetery. They fled. There’s a ditch there where they regrouped. And we went from house to house to see what was left.

Thirty minutes passed, no more, when the call came: “Come on, let’s go!” The village is burning, the barns are burning, the house, the whole farmstead is burning. [Indiscernible]. We clashed with the Poles again. There were walls, you had to drive them out with grenades. Just then, a boy with a machine gun calls to me: “Vasyl, over here, over here! Come here, into the orchard! They’re coming through the orchards!” So I got on the machine gun. There was a big apple tree, and from behind it, I started firing. And here [indiscernible] runs up from the road and says, “They’re coming from the river, a whole horde is coming! The Bolsheviks!” Well, at that point, we didn't know what to do. We quickly hid—just for a moment. To see who was coming, so we would know where to engage. We look—and it’s our guys! A unit from Perevoloka was stationed there—over a hundred boys—they saw the fire and were coming to help. Then we discussed what to do. It was already late, just before dawn. We thought about going to Pidzamok, smashing and burning that whole village... but we changed our minds, because it was almost morning, there were no forests here, and nowhere to go.

The next day, I learned that my mother had been killed, my father-in-law was killed, thirteen people were killed and burned, my relatives were beaten.

V.O.: What time was this, which year? The month, at least?

V.P.: It was in 1945, in January. That's when the real partisan movement began.

V.O.: When did you join the partisans?

V.P.: In 1944.

From that time on, our detachment was organized—our unit. And we moved as a detachment, almost a hundred men. When the spring roundups began, the command came to break up and hide in the *kryyivkas* [bunkers], because they were coming in divisions—occupying the forests, fields, orchards, and villages—searching for us. Try to stand against a division. If only there had been forests, but this was Podillia. What’s more, if you started shooting, they would burn the village. We had to maneuver here and there.

Then we received an order. In 1944, the raion and supra-raion SB commanders came. They gathered all of us (those boys are still alive) and said that in the village of Stari Petrykivtsi there was a fluent military man named Ishchenko. Our people had left him alone as a Ukrainian. He was connected with our organization and did what the organization needed him to do under the Germans. He knew many people, knew many places. When the Bolsheviks came, he fled and became a Chekist in the raion. They gave him an operational group and assigned him villages where he operated. He knew everything about those people. He would come in with his group, and as soon as it got dark, he’d emerge from an ambush. He arrested many people there, he caused a lot of “joy,” and many were exiled because of him. They said, “Whoever kills him will receive the Iron Cross from the *Provid* [Leadership].”

The SB men talked to us, and we dispersed. They left. There was one girl with them, a courier. They went beyond the village of Novostovtsi. She went off and betrayed them. All four of them were killed. That same evening, by morning they were gone. A pursuit was sent after the girl. And we, as the SB, were sent to another district to look for her. Then the raion commander said that we wouldn’t go to another district, they had their own SB there—let them look. “But you know her, you know what she looks like.” “She could just change her pseudonym—and that’s it.”

We went searching and found her. We found her, brought her in, and handed her over to the commander. There was a new commander already. We handed her over to the commander of the supra-raion SB. He talked to her and let her go. We didn't know what to say. What was going on? What was happening? Who was he? How could he do that? It turns out he gave her a revolver and told her to carry out an assassination: “You’ll end up in our hands anyway,” he said—to kill that Ishchenko. He was a captain by then, I think. To kill that captain Ishchenko, the local officer. She left, and to this day, no one knows where she is. He wasn't killed.

Well, it's a long story. But I'll tell you about the reports.

One time, I had to deliver reports, because we had to submit them every month. Reports were submitted from the sub-raion to the raion commander. The raion commander would rewrite them and submit them to the supra-raion commander, who would rewrite them and submit them to the oblast commander. And so it went, up to the regional level, and then abroad. And I had already been appointed a sub-raion commander.

I took the reports with the raion commander. The raion commander was Dmytro from Pereluky—I’ve forgotten his last name. A very handsome boy, a good-looking guy, we knew him from social events, from a neighboring village. We talked about completely different things, and I gave him the reports. And he left. We went our own way and quartered nearby, at a woman's house. And he went on with another man, whose pseudonym was Hrim [Thunder]. Just as dawn broke, the woman comes running and says, “They’ve surrounded Bohdan. Ishchenko’s operational group has surrounded him. Over there, six houses up.” And so we—the five of us, me with the machine gun, I always loved the machine gun—we went to fight them off.

If it were today, I would never have allowed myself to do something like that. But the thing is, the Bolsheviks had military academies, combat experience, partisan tactics, they never expected such hocus-pocus. No forests, nothing—in Podillia! We went along the hills; the sun hadn't risen yet. We went to fight them off. No one thought about what would happen next. We had just come out onto the street from behind, and there were stone walls. We went along the walls, and people were running and saying that Bohdan and Hrim were already dead. They shot themselves. What to do? We went back: “Come on, boys, let’s set up an ambush.” And we set up an ambush in the village of Biliavyntsi or Osivtsi, I don’t even remember which. We set up the ambush. Ivan Solomynkiv from Pereluky, such a handsome boy, and Vasyl Mudriachkiv from Petrykivtsi ran out to join us (they were quartering there), and there were seven of us. People were passing by, and we herded them all into a barn, so no one would betray us, no one would inform on us. We locked the barn—and that was that.

And about two kilometers away from us was the Staropetrivskyi garrison: three hundred soldiers. And so, after lunch, a wagon drives by, carrying the bodies. Walking in front is Ishchenko, in a civilian fur-trimmed jacket, a fur coat underneath, a submachine gun on his chest, drunk. And behind him, two equally drunk officers. We had agreed not to do anything until the flare went up... I lay down in a smithy. There was a collapsed wall. And where the anvil had stood, the wooden block had been removed, so there was a pit there. I took up a position behind that wall with the machine gun. I had him in my sights, just above the knees, and I forgot about the flare; I didn't want to let him go. I fired a short burst—bang, and that was it. Then I watched the officer. The officer dropped to the ground. As soon as he started to get up, I fired a second time. The officer went silent. Chekists started firing from behind, a firefight broke out. That Ishchenko managed to get up again and then fell into a puddle. It was spring. A Chekist was firing from behind a wall. I was lying just like this, here's the wall, and I'm lying on the wall, the machine gun is on the wall, and he pokes his head out at me from behind his wall. I had a grenade ready and a revolver, a Nagant, at my side. I took the grenade and wanted to toss it gently to him. The grenade hit the wall. It was hissing. I wanted to hit the stone with my hand to knock it off with the grenade. The stone ricocheted—and the grenade went under my machine gun. In a flash, I threw myself into that pit where the anvil used to be. And the bag with ammunition and grenades fell under my stomach. I wanted to throw it out. At that moment, the grenade exploded and my finger was left just hanging here. The finger was dangling…

Then I told the boys, “Let’s retreat.” Because flares were already going up from Petrykivtsi, and flares from here: “Send help.” The Petrykivskyi forest was about a kilometer away, maybe less. We headed for that forest. We had just reached a crossroads when the trucks started arriving. I fired at the trucks with the machine gun, they jumped out and took cover on the road. And we ducked under the hill (there's a road down below) and entered the forest. They were coming towards us. We fired at them from the forest. They retreated. The encirclement began.

They are surrounding us, trucks are roaring, troops, flares, a dark night, spring, fog, cold. What to do? They surrounded us completely. What do we do? We go towards the village and start shooting and shouting, as if we are breaking through into the village. Once, twice, they opened fire, a battle began. As soon as they quieted down, we did it again; as soon as they quieted down, again. When that chaos started, we quickly went back to the other end and came out into a field. We’re walking. The field boundaries there are high. North of the forest, we follow a boundary line. And then a machine gunner opens up. He saw us walking. Because it was twilight, you could still see a little. But he knows that if he makes a move, he'll die. Because we're also soldiers, we know the drill. So he let us pass; we went by. We escaped from that hell.

We came out onto the main road. Someone is walking straight into our hands. “Halt!” “A Chekist is coming.” “Where from?” “From Buchach.” “Where to?” “To Novi Petrykivtsi.” “Why?” “To see a girl.” A young boy, Mykola Muzykin. He took him to the cemetery, wrapped the revolver in a handkerchief so the shot wouldn't be heard, shot him, took his rifle, and we went with Omel behind the village.

It’s dark—can't see a thing. A woman is walking. We stopped behind a barn and listened. A terrible barking of dogs. A woman comes out with a lamp. We approach her. She says, “Run, boys! The village is full of them, they're surrounding it. They're already surrounding that area. They’ve been surrounding the Petrykivskyi forest since daytime. And the village is full. Tomorrow, who knows what will happen here.”

We immediately turned and went towards Medvedivtsi. We went, and there they bandaged me up: they put a splint on my finger so it wouldn't dangle and wrapped it. My hand aches, it burns, burns like fire. Where to go? I went to Zvenyhorod. “You boys go on,” I said, “and I’ll get medical treatment.”

Just as dawn broke—the Bolsheviks. The yard was full of them. That means something's not right. In the evening, I escaped. I left that place. Where to get treatment, eh? I went home. I climbed into the *kryyivka* (there was a very good *kryyivka* at home). A boy had died there, but the hideout remained. I looked—the entrance was from above. I climbed in. I stayed there for a week. Early one morning, I hear screaming, noise, crashing, rumbling, cattle lowing. What’s going on? I quietly lift the slab and climb out of the *kryyivka*. The little door is ajar, I peeked—and a Chekist is standing there with the homeowner. I went back into the *kryyivka*. I lowered the slab, propped it up. And I hear him say, “Well, he’s at your place. He was here yesterday,” he says to the homeowner. The homeowner says, “He’s not here. Search. He’s not here.” “He’s here at your place. You’re being sly. We’ll give you...” Well, I don’t want to tell you what they’d give him. Some reward. “No, he’s not here.” So I listened, and finally I hear them coming. A Chekist climbs into the pit. He climbed in. Submachine gun, a probe. He pokes here and there. A second one climbs in: “What’s there?” “Nothing.” “Let me try.” The second one climbed in: here and there, poking the ground with the probe, the sides, the wall, the ventilation shaft, he broke the ventilation shaft. And the entrance is from above, covered by a slab. And I’m watching them. That one comes over: “Well, what’s there?” “Nothing, Captain. There’s nothing.” “How is there nothing? He’s here!” I hear someone talking to him: “I was just here. Kostia said he was here this morning. Search and you’ll find him.” “And where is he?” “He’s sleeping. He didn't sleep all night.”

Kostia (there was a Kostia Pirus), he was an informer under the Poles, then their informer in 1939, then he was our informer and theirs.

V.O.: The same last name—Pirus?

V.P.: Kostia. And I realized who was after me. A little time passed, they climbed out of the pit. The woman came in: “Vasyl, get out! Get out!” I kept quiet, because we had our own password. “Ah! I forgot,” she said, and gave the password. I got out, went to the stone slab: “What’s going on?” “Run quickly, you’ve been betrayed. They said you were here, and that you hid somewhere this morning. The officer said you hid somewhere this morning. Run. Here, take these clothes,” she gave me a skirt and a headscarf.

I took grenades, a revolver, put on the skirt, and went into the woods. I came out of the woods and went into the field. I went into the field—no one was there. I lay down by a field boundary. It was cold. I lay there until evening. I wandered like that for another week. The pain in my hand was unbearable. No medicine, no doctors. What to do? I pour moonshine on it. I have to get somewhere. I’ll go to my own village; there I can get bandages, I can get some kind of medicine. I went to a woman’s house; there had been a *kryyivka* there, but now only the entrance was left.

I arrived on a Saturday. On Sunday morning—troops. They came with a field kitchen. Two hundred men. A roundup! They’re looking for me. That’s how closely they were watching. They’re digging. My neighbor, Slobodyn, is digging a pit. They’re digging right next to me. The *kryyivka* is here, and they’re digging right next to me. I can hear them talking. A Chekist comes up: “Well, what is it?” “Nothing, chief. Nothing here... We’re digging,”—and they’re throwing the earth on top of me, on the *kryyivka*, on the entrance—“we’re digging—nothing here.” “But he is here!” He walked away and stood there. There was a hole in the wall, for air to come in and go out. Someone comes up to him: “Well, Comrade Major?” “The orders were clear: he is here. He was sitting in the lilacs. This morning he was here. We must find him.” They dig, they broke everything, tore up the entire yard and the houses. Then I hear: du-du-du-du—someone is running. He stopped: “Comrade Major, they found a *kryyivka*.” “Where?” “Over there, where we were searching last Sunday.” “Let’s go see.”

They rushed over there, the command. The command rushed to that *kryyivka*, and as I was leaving, I had said, “Fill it all with earth right away, otherwise it’s obvious something is there. Fill it with earth, throw some old pots in there. You can say it was there since the German occupation.” And that’s what they did. They piled earth on it. They came and searched in that *kryyivka*, maybe there was a second one inside.

Evening. It got dark. I'm climbing out. I get out—the wind is howling! I'm heading for the cemetery. I'm not walking anymore, but crawling on my hands and knees toward the cemetery. I look—a light flashes. I crawl back. I crawl through the vegetable gardens. A Chekist is lying there... There were two of them, talking quietly to each other. Ivan couldn't resist a smoke. No matter how he tried to hide the flame, he lit up. And I slipped past them—the wheat was still so short. I slipped into the wheat along the field boundary. While I was moving, they were lying there, about ten meters away from me. I got out of there and left. And I told myself that I would never enter that village again. They were watching me too closely there.

But still, the temptation is there. I went. I went to that Kostia, and he tells me he’s in trouble: “What should I do? Take me into the partisans.” “Where? Don't you know,” I say, “we’ve been forbidden to set up ambushes, we’ve been forbidden to show up in the villages. We have to bypass the villages.” I tell him all this. “But where can I go? They gave me the ‘barrel’ treatment.” Do you know what a barrel is?

V.O.: Yes, people have told me.

V.P.: So he tells me: “They came, arrested me, and took me to a *kryyivka*: Stepan Bandera, the trident, people sitting in tridents, belts with tridents. *Mazepynka* caps with tridents. They’re sitting there, talking: ‘Alright, Chekist agent, start talking.’ He says so-and-so, he knows the boys. ‘Which ones?’ He tells them about me, about this one, about that one. He tells them everything: ‘I’m no agent. You can ask them,’”—well, it’s a long story to tell. In short, they lead him out and take him to the village to hang him. Suddenly—a flare and a shot. He drops like a sack, because they're shooting. Those guys fled, the Bolsheviks catch him and take him to the raion center. ‘Where were you? Who beat you?’—he starts spinning a tale. They started beating him. Nothing came of it. Then they bring him witnesses. And they told him, ‘You have one month. Either you give up Vasyl, or you'll go where he’s supposed to be. If they don’t shoot you as a Bandera spy, you’ll get 25 years and go to Siberia.’”

And this Kostia Pirus tells me, “Take me into the partisans, because I’m in deep trouble.” But how could you take him into the partisans? When we knew who he was… We talked him out of it.

But the Bolsheviks had gotten so bold that it was impossible to collect reports—the ambushes were everywhere. So what did we do? This was us, the boys from Zaryvyntsi. Let’s go to Buchach. We need to blow up the power station, create a blackout, and then we’ll go for the prison. We’ll smash it. We had two German *Panzerfaust* anti-tank launchers. I took a machine gun, we loaded everything up. Those boys are still alive. Mykhailo, Franko Yursky… he’s still alive. We took a couple of anti-tank grenades, a cord. Cleaned our weapons, loaded them. Put our rifles on our shoulders. You know those rifle grenade launchers? The grenade can travel up to a kilometer. And before going to Buchach, we sent this Kostia on a reconnaissance mission: “Go find out how many of them are there, how they are positioned.” He went. He comes back and says, “Boys, everything’s clear. There are no Bolsheviks. Everyone goes out on ambushes in the evening. Besides the garrison, there’s nothing else.”

We're going to the station. There's a small farmstead there called Hai. I went to see my aunt. I hadn’t seen her for years. How could I not stop by my aunt's when it's just a few steps away? I say, “Boys, I’m going to my aunt's.” She burst into tears. She brought me a bandage. “Maybe you want something to eat? Where are you going?” “Well, we don't talk about that.” “I don't need to know. But I want to tell you, if you’re heading to the city, don’t go.” “Why?” “I just came from there two hours ago. They wouldn't let me leave, I started begging, crying that I’m from Hai, and they let me go. There are troops there, they’re digging trenches toward Nahynka, over here. The city is full of troops.”

So that Kostia is a scoundrel. He sold us out. We go to the river. It's quiet along the river. We approached the power station. We went in, and the guards immediately dropped down. We took their weapons, planted mines, and pulled the cord. A German hand grenade, a *Stielhandgranate* with a wooden handle. It failed to detonate. So I started firing at the engines with my machine gun, at the control panels. The lights went out.

We go into the city. We got to the top of a hill, launched two grenades. The grenades went off with a huge bang—silence. The city fell silent. It sounded like God knows what kind of artillery was firing. And there’s a forest nearby, Fedorivskyi Forest. We started shouting “Forward!” Oh, Lord! It’s a long story. Such a firefight started! The flares they began launching lit up everything as bright as day. Flare after flare, constant shooting. We look—the place is crawling with troops, nothing’s going to work. We started firing grenades from the launchers. We turned back to the river, crossed it, went through the German trenches, and got to our forest, to our *kryyivka*. In the morning, we hear—no one. But after lunch—someone is running. A woman stopped and said, “Boys, be quiet! A whole detachment attacked Buchach last night. So many troops have arrived! Planes are flying, they’re shelling the forest with cannons, they’ve surrounded the forest. Sit tight!”

It would have been quiet, but one of our men told that Kostia, and Kostia told the Chekists that I was the one who killed Captain Ishchenko. So they came after me. There was no escape. So I gather the boys: “What do we do? Let's go to the mountains.” We needed to cause a commotion in the villages. If it weren't for Kostia, they would have sat there for months, watching. But he sold us out!

The next day, this Kostia came to me and asked why we didn’t take Buchach. I told him, “Because the other units didn't arrive.” I already knew who he was and what he was about. I didn't believe a word he said. But I told him that in a few days, maybe a week, the units would arrive, blow up the station—and then attack the city, the prison... He ran off and informed on us. So they sat there day and night in the trenches, on guard. And later I was told that they figured it out, and when they launched their attack on us, we had to retreat to the mountains.

We went to the mountains but didn't make it. In the Marivski forests, we met up with some other boys and stayed there for a bit, but we had to move on, because of the reports—the reports had to be submitted every month, you had to go through the villages, collect them from the local leaders, copy them, and hand them over. Otherwise, the punishment was severe. The discipline was ironclad. We went. And then an order comes: only the SB. A few boys from the sub-raion—five, six, or at most ten from the sub-raion. The meeting point is designated here and here. Everyone must have an anti-tank grenade. At least one machine gun for every three men. Three spare disk magazines, one on the machine gun, and five hundred rounds of ammunition. Three days' worth of food. We went there.

We gathered; there were already fifty of us. The next day, there were a hundred. The third day, one hundred and fifty. We crossed the Dniester—a whole detachment of us. And there were others too. We started showing ourselves to draw the Bolsheviks towards us. And we succeeded. We didn't even have to draw them. Because in the forest, a stool pigeon was grazing a cow. He deliberately walked around with a cow. He was looking for where we were. And as soon as he found us, according to his instructions, he was supposed to light a fire. A plane flies overhead, immediately takes a picture, and provides the coordinates. The troops move out immediately. As soon as we saw the smoke, the commander said it was a provocation: “Go catch him!” The boys rushed after him and brought him back with his cow. We gave him fifteen minutes, and he confessed everything. Then we retreated and took up positions.

It would take a very long time to tell you about that battle. But after that, we retreated back to the west. And at night, we went back there again. A few days later, another detachment clashed with the Bolsheviks. We knew right away because we heard German weapons. “Oh, that’s our boys—they're in trouble! Let’s go help, boys!” We went. It was a good fight. Both our men and theirs were killed there.

Then the order came to disperse from large detachments into smaller ones. Because it was easier for smaller groups to move, easier to get food, and easier to conceal themselves. Smaller units were much better than large ones.

There were probably forty of us boys. And then a plane circles overhead. We were well camouflaged. The commander told everyone to get into the blackberry bushes. To hide, so the plane wouldn't photograph us. The main thing was to hide our weapons, so the metal wouldn't glint anywhere. That's what we did. The planes circled and circled, then flew on and circled over there.

And then a boy from my village, Mykhailo Kozariv (he was born in France, came here with his father), says: “Vasyl, come here quick—we found a *kryyivka*.” I had just dozed off: “Where?” “Over there.” I crawled over. Another boy from Pereluky was already there. He climbed in—and the cover broke because it had rotted. The boy was crawling on his elbows—and it gave way. That's how we found the *kryyivka*. No one in the world would have ever found it, and who knows who dug it.

We went inside. We lit some wood splinters. We look—there are candles. We lit the candles: there are bunks, but made of round logs. The entire *kryyivka* is lined with round logs, and the ceiling is laid with logs too. Strong supports. I don’t know if there was stone there or what, because it was all covered in wood. Two suitcases. No, not suitcases, but small trunks. And there were various things inside. Our commander came: “What’s here, boys?” “There are suitcases, but no one is here.” “Search! There are things, any clue who was here?” Not a single spoon that had touched food, or any food products, or even any slops—nothing. Buckets were standing there, all empty. Two Hutsul wooden buckets were there, Hutsul footwear, Hutsul blankets. A whole set of tools: a double-headed pickaxe, a metal crowbar, spades, a shovel—all standing there—a pickaxe, nails. We went further. We opened a suitcase. Oh, Lord! Our eyes widened: medicine or some ampoules. So many ampoules! But we never found out what kind of ampoules they were. Ampoules and more ampoules. Behind the ampoules lay a map: Romania, Poland, with lines drawn across the border—probably Poles had been here. Or maybe Jews? Or maybe Bolsheviks, communists hiding from the Germans? What did they eat? Nothing, everything was new. We found a notebook. In the notebook, it was written that on the third they left Warsaw, and on the ninth they were in Stanislav.

V.O.: What language was it written in?

V.P.: Polish. A photograph of a woman: him and her, sitting on his lap. She looks like a Polish woman. And he's dark, like a gypsy, very black. And there was a commercial fleet captain’s uniform. The boys came to see what was there. A cut of Polish fabric for a suit, expensive wool. Green challis fabric, with flowers. With clover. Two pairs of boots, absolutely new—women's and men's. And a lot of women's underwear: panties, nightgowns. Lots of them. A leather bag, made with a drawstring. We opened it—inside, in waxed paper, was something like a notebook. There were American and Canadian dollars, and English pounds sterling. A second bag was full of gold coins, from who knows where. The commander says, “Well, boys, figure it out, who could this have been?” We opened a small box. There were two small boxes, caskets. In one casket—two gold watches, rings. One casket was silver with gold, but not as beautiful as the wooden one, which was decorated with gold, with those stones, with that mother-of-pearl. Well, I had never seen such beauty before and probably never will again. Then we opened the second suitcase; there were similar watches and all sorts of jewelry. “They must have been some kind of thieves,” I say. There was also leather for boots, and cuts of fabric for suits—so they wouldn't have to exchange money. Not a single Polish zloty was there. And there were blankets, and sheets, and what wasn’t there. We inventoried everything, and the commander sent four boys with it; they took it "up the hill," as we used to call it.

We entered a village. What kind of village? It was just one house. Not like our villages, where houses are packed together. We went in to see a woman. She says, “A combat unit just left. There's nothing here, boys. The unit just left.” The commander says to cut some of the green fabric, and everything will appear. They cut the fabric, took it to her. Oh, how the girls’ eyes lit up! And they had children, like gypsies, four or five of them. And a teenage girl, about 14 or 15, tried it on. “Oh,” she jumped up, “Mama!” They said to cut some more because it was too much for one dress but not enough for two. They cut more. What a laugh we had! They went down to the cellar, brought up potatoes, and the man slaughtered a ram. And so began the feast. We gave them linen cloth, cut pieces for the children’s shirts.

We all swore an oath on our weapons that as long as we lived, we would never speak of this expedition. Wherever we were captured, no one was to admit to this. We swore. And what an investigation there was! I always said I had never been in the mountains. It turns out there was a high-level meeting taking place abroad, and we had been sent to divert the Bolshevik troops. We were already returning home when we encountered a group of Chekists. We were at the edge of the forest, it was evening—and suddenly—bang!—a group is coming. One of them comes towards us. No time to run, no time to shoot... He saw us—and ran. A firefight began. And that's when a bullet hit me.

V.O.: When was that?

V.P.: After we had been in the mountains.

V.O.: But the year, the time, the place?

V.P.: I don't remember what year it was: 1947 or 1948.

V.O.: You were a partisan for several years?

V.P.: Five years.

V.O.: Five years? And when were you arrested?

V.P.: At the end of 1948, on December 19.

V.O.: As late as the end of 1948? Obviously, you won't be able to recount all the combat episodes now…

V.P.: I already told you how I was taken to the *kryyivka*. I won't tell the whole long story, but I will tell you how winter came in 1948, and they were hounding us to get out of there. I was serving as a courier to the east. Is the story of the courier run interesting? I had contacts in the east, beyond the Zbruch River. And I decided to head out there. I went with one other boy. But it turned out that everything there had been exposed: a woman had remarried, her husband was a communist. That was that. So we—in the snow, frost, and blizzard—turned back. My comrade got sick, I left him in Laskivtsi, I think. I went on alone. The order was to collect the reports: winter, snow, frost, white everywhere, visibility for a kilometer. And the order is—collect the reports. I didn't want to go. “They’ll shoot you.” I say, “Who will shoot me?” “We’ll shoot you.” And we started arguing among ourselves. So I went to collect the reports. I entered my village, and I was sold out.

Morning. Just as dawn was breaking—a hundred men surrounded the house: “Come out!” That’s it, the end. My partner Vasyl and I kissed goodbye—we were going to shoot ourselves. But Vasyl says, “Let's kill his whole family so they know what happens when you betray someone.” And there were four or five children there. I wouldn’t allow it. But he insisted—it was the only way. “They’ll know for next time what it means to sell someone out!” And I say, “If you want to do that, let’s shoot it out with the Bolsheviks, not with a family.” We decided to fight back, to hold out at least until evening. And we began: a shootout, then negotiations, then a shootout, then negotiations. The houses there have metal roofs, two stories; we broke a hole through to the barn. When it got dark, we planned to stack two sacks, set fire to everything in the house, shout “Glory to Ukraine!” and pull the pin on a grenade. They would run to put out the fire and drag away the bodies, and we would slip out of the barn, out of the cowshed, shoot anyone in front of us with the submachine gun, and leave. There was shooting all around.

The sun went down. And they were firing—I'd never seen anything like it, the bullet was probably ten centimeters long; it would hit the wall, penetrate about three centimeters, and fall back out, emitting a blue-green-pink smoke that was very sweet in the mouth. I was upwind, the windows were shattered from the battle. But Vasyl was over by the wall; he inhaled that smoke and collapsed. It was night by then, we were lying by that hole, ready to jump down. It was time to set the fire. I say, “Vasyl, light it, light the bedding.” Vasyl is silent. “Vasyl, light the bedding.” Vasyl is silent. A grenade—pop! They threw a grenade. A burst from submachine guns sprayed the windows. I say, “Hold the door, hold the door. I’ll fire from this window, the corner one.” But he is silent. I nudged him, and he just stirred a little, and that was it. A grenade—pop!—it rolls towards me, I managed to grab it, throw it out the window, and it exploded instantly. A second one—I kicked it, and it exploded under the threshold. Smoke! The window behind me, two sacks lying over the hole. I say to him, “Vasyl, let's get out of here, they're using grenades now!” He’s silent. I nudge him, but he’s silent. That means he's dead, it's over. Then I hear: psh-sh-sh—one sack, a second sack, and here’s the window. I’m lying here, and there’s the door. A grenade fell between the sacks, hissing. I tucked my head down and buried myself in the sacks—and then the grenade exploded. It knocked me senseless, I don’t know what happened, I don’t remember. A sound and smoke, and sweetness in my mouth. And the Chekists swarmed me. They picked me up. Sleep! An overwhelming urge to sleep. Vasyl is sleeping, sleeping like the dead. They carried us out.

V.O.: Where did this happen?

V.P.: In our village. December 19, 1948. On St. Nicholas's Day. And I don’t remember what happened after that. I see light, a lamp is on. They are leading me. I feel very warm. They brought me in—a ward. I realized where I was. A doctor came, with cotton wool, and washed off the blood: my whole blouse was soaked in it. He pulls out a piece of shrapnel with tweezers. He pulled it out, took it to the Chekists. I remember this as if it were today. He says, “What a lucky guy—it was a millimeter away from his brain!” He shows them. He put on some cotton, sprinkled some yellow powder on the wound, bandaged it, and sat down. He gave me some injection and just sat there. He felt my pulse, stood up, and said, “You can proceed.” And that’s when they started beating me with clubs, just beating me.

V.O.: What did they beat you with?

V.P.: Clubs. Beating, beating, they beat and beat, beat and beat—and asked nothing. They finished beating me. The head of the Buchach MVD, Karpenko, walks in. When we had attacked Buchach, he hadn’t known what to do. He had a maid from our village. Where to hide?—It meant death. He told her, “If you hide me, you will live and never have to work a day in your life, if I survive this night.” She hid him in a wooden chest and covered it with firewood. He sat there until morning. In the morning, she went out to find out what was happening in the city. They told her the Banderites were in the forest. She went back and told him that there was no one in the city. They pulled Karpenko out of there—that raion head of the MVD. He couldn't stand up, his legs were crippled. The women rubbed his legs with alcohol and brought him around. So he said he would take revenge on me a hundred times over for that night.

And so he found out it was me. He comes in. With nothing in his hands, he grabs a club and, first thing, hits me over the head. He doesn't even look at the fact that my head is bandaged. What's more, blood is still seeping through the bandage. I fell to the floor and I can feel him beating me. He beat me and then, finally, spat on me. He sat down by the window. He must have been too tired to beat me anymore. He threw the club at me, spat, and left. Then they started asking: where is the village leader, where is the raion commander, where is the oblast commander, the county commander, where are the networks, where is the SB. I tell them the SB has been gone for a long time. “How can it be gone?” “Gone for a long time.” The conversation turned nasty: so-and-so this and that. And again with the beatings. On and on. And if you name one liaison, a whole village will be taken. And they arrest them, and transport them... And they just keep pummeling you, pummeling you! I thought to myself, I was supposed to be dead, like all the others. And here I am, like a fool, letting myself be tortured like this. I should have just shot myself right away. Why endure all this? And who knows what the end will be?

They ask me questions. And I say, “I don’t know. And even if I did, I wouldn't tell you.” And then they started torturing me. They beat the soles of my feet so badly I couldn't put my boots on. They tormented me, pulled my hair. I couldn't even walk to the interrogation. It's a long story...

When the investigation was over, they took us to Chortkiv.

V.O.: Where did the investigation take place?

V.P.: In the Buchach prison. They take us to Chortkiv. The station is in Peshkivtsi. In Peshkivtsi, they took us out of the Black Maria and led us to the station. The train hadn't arrived yet. And the place was crowded with people. And that Chekist from the convoy started telling the crowd, “Bandits, they wanted independence. You’ll see it when moss grows on the palm of your hand, you bandit scum.” I couldn't take it anymore, I went for him. And he screams, “Shut up! Shut up, or I'll shoot!” We arrived in Chortkiv—they filed a report that I had made anti-Soviet statements. Not once, not twice, and that the convoy had stopped me. But that I had continued. “Sign it!” I took it and signed. And he just stands there, watching, “What are you doing?” “This is what I said,” I say, “I did say it.” And he just stands there looking: “What are you doing?” “But I did say it.” He's looking at me as if a fool has just arrived. He went silent. The chief was a guy with a belly, a crew cut, a *khokhol* too, the chief of the Chortkiv prison. A major or a lieutenant colonel, I forget now.

And so in Chortkiv, a second investigation begins. I say, “I've said everything, I have nothing more to say.” Then they take me and my comrade to Ternopil, to the oblast center. They brought us to Ternopil. There, they tried to provoke me into escaping. An artist. He was a teacher himself, a rather cultured man. Let's escape, he says. I say I can hold out... But that's a long story. In the end, he knocked on the door and went out. And he's gone, and gone, and gone. And then the door opens, the corridor is full of armed guards: “Pirus and Slyziak, out with your things!” What things? A towel. We left, they pushed us into a Black Maria and sat us down. They consulted among themselves for about an hour, while we just sat there.

Finally, the vehicle started moving. It was evening, a starlit night, we were driving, I know we had already passed Terebovlia. The Black Maria stops: “Get out!” “Why?” “Get out!” They opened the doors: a field. Nothing else around. I say to Vasyl, this is the end for us, let’s kiss goodbye. We kissed, said our farewells. He’s putting on his boots, but his feet are so swollen—he can't get them on. I got my boots on and climbed out first. I shout to him, “Get out!” And he says he's putting on his boots. “Come out barefoot!” “I won't come out until I have my boots on.” We're standing there, we look—flash, a light goes on once, a second time, a third time. Vasyl has his legs out, ready to climb down. A car is coming, it passes by. Just as Vasyl gets down, a second car drives up. A Bobik [UAZ-469 utility vehicle]. It stops. We see an officer get out, then another. He approaches the convoy: “What are you doing here? What happened?” “Nothing happened.” “Then why did you let the men out?” “They wanted to relieve themselves.” I immediately understood and said to the officers, “That’s not true, we didn’t ask for anything.” The officer says to the senior guard, “What do you think you’re doing? I’m driving to Chortkiv right now, and I want you and them there within the hour. You will answer for this.” He said something else. This and that: “Get in, you scum.” We climbed in.

They brought us to Chortkiv, the Black Maria stopped in the yard. An officer came out, looked, and said, “Take them to a cell.” They took us to a cell. And it begins: sign everything—and you’re off to the transport.

I won’t say I was so clever, or so strong, or so bold, or some kind of defiant hero. It was some force that helped me endure, that I did not give up a single village leader, not one liaison, not one courier—absolutely no one. I was able to not give up anyone. But they themselves are partly to blame, the Chekists, because if they had just asked and persisted, but no—the prisons were overflowing, the circular saws were running day and night, people were being tortured, people were screaming. And diesel engines were running to muffle the sound, and the circular saws were screeching so loud that your brain felt like it would pop out, you couldn't stand it all. They were drowning out the screams of people, because they were torturing people there, beating them.

I am satisfied, I don’t even know what to say. I think that some Great Power helped me, no one else, because I couldn't have endured it myself if someone hadn't supported me morally and spiritually. Because in such torment, in such torture, a man might not even know what he is saying.

But time passed, and we were sent to the transport.

V.O.: Was there some kind of trial?

V.P.: The trial was in Chortkiv. Some prostitute and two sergeants came and commuted my death sentence to twenty-five years. Because I would have been shot, but there was an amnesty at the time.

V.O.: Do you remember the date of the trial?

V.P.: No.

V.O.: That was in 1949, right?

V.P.: In 1949.

And so, on to the transport to Lviv. That’s a long story to tell. From Lviv, they transported us for a whole month to the Far East. From the Far East, they took us to Magadan. But even before they took us to Magadan, I’ll tell you how they loaded us.

Three ships arrived: the *Dzhurma*, the *Nogin*, and the *Shevchenko*.

V.O.: Which port was this?

V.P.: Sovgavan. One ship was loaded with common criminals. The strange thing was—those criminals were playing cards. And now they are herded onto the ship. The common criminals know what Kolyma is, they know about the terror there, the great lawlessness. And they absolutely did not want to go there. They broke their own arms, their own legs. They led the cripples, carried them into the holds. He broke his arms—they led him; he broke his legs—they carried him. Do you understand—naked people are walking, absolutely naked, they’ve just torn up some cotton and wrapped it around their genitals. It's cold, freezing. He's walking barefoot. And they herd him into the hold. Another one is on the gangplank, the ship's stairs, carrying a sack made of bedsheets, full of junk—there are jackets, blouses, trousers and underwear, briefs—all won at cards.

V.O.: And the first one had lost everything?

V.P.: And that one had lost everything. The question is, what did he need it for? He's carrying a whole mountain of stuff. Up the gangplank. He can’t make it, they help him. Finally, he falls, the junk tumbles over and he falls down the gangplank, the stuff scattered everywhere. They’re gathering up the junk… We're watching—and waiting. They herd others. A guy walks by like an angel: two tattooed wings—a pure angel. Naked as the day he was born, with only a wad of cotton between his legs. An angel, with wings on his back. You stand and watch, well—it's a circus. Or who knows what. They loaded us on.

They loaded us. A storm rose up. Twelve-meter waves were crashing over the ship. It tossed us around like that for maybe a night, and then the storm subsided. They took us to Magadan.

V.O.: Which ship were you on? What was its name?

V.P.: The *Nogin*. And so they brought us to Magadan, to the transit camp. And in the transit camp—tens of thousands of people. They put us in trucks and took us to the camps to mine gold. They dropped a thousand of us off at Spokoiny. They dropped us off, and we went to mine gold.

They gave us these iron drill bits; they were one meter twenty centimeters long. We had to drill a one-meter-twenty-centimeter hole all the way through. One man kneels down, pushes aside the snow and slate, and the other takes a sledgehammer and strikes the bit. And the first one turns it, making a hole. There’s a special spoon to scoop out the dust when it accumulates, and then you keep drilling. The quota was to drill eight meters of granite per person, and for a team of two—sixteen. We had to drill sixteen meters. The blasters would detonate two meters, clear it out, and that would count toward the quota. Whoever meets the quota and exceeds it gets a reward. If a brigade produced more than the quota, and someone achieved 151 percent—that means he did more than one and a half times the quota. He already has the right to carry the “joy into the zone.”

What is “joy in the zone”? “Joy in the zone” is a decorated stick with a cross piece at the top, where it’s been shaved with an axe and written on in charcoal: “Br. Balabanova” [Balabanov's Brigade].

I was in Balabanov’s brigade. I didn't have a name, just a number: R-1743. And that’s it: a number on the knee, a number on the forehead, and a number on the shoulders. Balabanov's Brigade—we were all Balabanovtsy then. And so the Balabanovtsy carry the “joy into the zone.” They have exceeded the quota. Whoever did the most work is entrusted with carrying the “joy into the zone.” He carries this sign at the head of the brigade into the zone. The brigade has 25 men. All the brigades march by, and 150 men are standing near the zone entrance. The administration comes out: “What ‘joy in the zone’? Whose brigade?” “Balabanov’s, citizen chief.” “What was the percentage?” “One hundred fifty-one, citizen chief.” “Oh, well done, well done! And what’s your quota?” “Ours is one hundred and five—one hundred and ten.” “Not enough, not enough.” “Tomorrow will be better, citizen chief, tomorrow will be better.” “We hope so, we hope so.” He steps forward. “Citizen chief, let us know,” the guard knocked. The chief and a medic or doctor in a white coat come out of the guardhouse. There were no bowls. The bowls were made from American tin cans. He carries the small bowl on his hand, and it's forty degrees below zero. The bowl is covered with gauze, and there’s a sprig on top. The chief stands: “Attention, prisoners!” Everyone stands at attention. “For good behavior in the camp, for fulfilling and over-fulfilling the quota… (and then he listed all the ‘fors’) Vasily Fyodorovich Stupakov is awarded one ‘hot one.’”

I will never forget his name; I'll remember it to my grave. One “hot one”! What is one “hot one”? It's a hundred grams of a casserole made from oatmeal or barley, and if they didn’t have that, it was oil-seed-cake. You know what that is? A wild weed, they add a little bit of flour to it to hold it together, otherwise it crumbles. That kind of casserole. He sticks his finger in it and gives it to him, and the guy wolfs it down—one, two bites—and the casserole is gone. And the Balabanovtsy brigade stands there, and I’m standing there too. We just watch. And you just feel the saliva run down your throat. You swallow. A happy man—he ate! You understand, when they put me in the SHIZO [punishment cell], hunger brought me to the point where I forgot I had a family somewhere, or a wife, or a homeland. I didn’t think about anything. All I thought about was what I could eat—I gnawed the bark off trees with my teeth. What they did to a person! The stomach is the master of everything—of reason, of sight, of smell, of hearing, of everything.

By the gates, a band is waiting to greet those who brought “joy into the zone,” who made their quota and more. For those who didn’t make the quota, they play the so-called “Disgrace.” So, we made our quota, the gates open: “Balabanovtsy, attention! First five—proceed!” The first step is taken... There was a violinist, he had a violin, but no strings, so they made them from cable wire. There was also a tambourine, but it had no leather, so they made it from canvas and drew a picture of a Russian in a belted shirt dancing with one of our Ukrainian girls. And a balalaika. And the violinist—there was a bull whose tail had been cut off, and they made a bow from its hair—starts to play. And what a disaster—he barely gets out the first *‘ti-li-li’* of—*"Vykhodila na bereg Katyusha."* “First, second group—proceed!” And the Balabanovtsy marched proudly past the guardhouse to the music of *“Vykhodila na bereg Katyusha.”*

And for those who didn’t make their quota, the musicians play “Disgrace.” Just like that: a “br-r-r” on the balalaika, the tambourine bangs, shame on the brigade leader and the brigade.

And so one time, we didn't make our quota. And if you don't make the quota, they don't give you food, no dinner. The Balabanovtsy who didn't make the quota came back. The chief says to Balabanov, “No quota—what's the matter, Balabanov?” “That’s how it turned out, chief. Tomorrow we’ll make the quota. I give you my word—we will.” “We hope so.” “I’ll beat the souls out of these sons of bitches!” “We hope so, we hope so.” “I’ll wring the last drop of sweat out of them, but I’ll make the quota!” The chief thought and thought: “We’ll believe you, we’ll believe you, Balabanov.” Well, they grumbled out the “Disgrace” for us at that guardhouse, and the hungry Balabanovtsy went to sleep.

It went on like this for two months. After that, we became *“dokhodyagas”* [goners]. Just skin and bones. Everything changed. They created a so-called OP—an intensified-regime barrack.

In the spring, they started recruiting carpenters to build gold-washing apparatuses. And they took me on as a carpenter. I went there. And then one day, a brigade leader is beating one of his coworkers, a Latvian. The Latvian is as big as an ox. He’s already killing him, the man is crawling on his hands and knees in the snow. “Stop it, stop it!”—but he keeps beating him. And the brigade leader is like a bantam rooster—small, thin, but he's swallowed some pills or something, his eyes are bulging, and he’s just beating him. And the Latvian crawled towards me. I try to get away, but he keeps crawling towards me, that Latvian. Well, he brought sin upon me—I finally went to the brigade leader: “Brigade leader, either kill him already if he’s guilty, or [indiscernible, speaks very quickly] what are you doing?” And he turns on me, in camp slang: “Suka!” [Bitch!] And he hit me, then swung to hit me a second time. I blocked him with the handle of my axe—he hit the axe handle, it snapped, and the axe fell on my foot and cut through my boot. The cold seeped in—it was forty degrees below zero. And he comes at me a third time. I put up my arm, he hit my arm, I grabbed the crowbar he was using, smashed him over the head with it, and he fell. What was there to hit, I smacked him on his hat—and down he went. I thought: “I’m not going to kill you, I’ll just break your arms and legs, and you’ll learn.” Because he was one of those “suki,” a collaborating thief. They were called “suki” in the camps. I had just started hitting him when the guards started shouting. I hear: bang, a shot. Whoosh, it tore the cotton padding out from under my arm—from my pea coat. It wasn't funny, I started to run. But that’s a long story...

They took me to the guardhouse, beat me, and then brought a canvas sheet. It was probably six meters long. It was shaped like a pennant—wide, about 50-60 centimeters at the top, and it tapered down to a cord at the end, and a canvas cord was sewn there, also about three or four meters long. And a sleeve was sewn here, with a ring at the top. They told me to stand up—I stood up straight, put my left arm in the sleeve—I put it in. They wrapped me, brought my left arm around, then under the arm so they could feel my pulse. And they wrapped me like that all the way to my feet, making me look like a swallow, like a mermaid. I'm standing. They tied it at the bottom, threw the cord over my neck, and pulled it through the ring. Two of them stood there, kicked me from behind, and I fall. If you fall, your skull will shatter. I arched my back, but before I hit the ground, they held me up. I hung like that for a few minutes, and then they started lowering me, bit by bit. They bend you like that, and they pull you upward. And it bends, it bends you backward, backward, backward. First, you hear a crackling in your ears. Then your vision turns yellow, then your spine cracks, then your ribs crack, then everything cracks, everything cracks, and after that, I don't remember what happened.

I know that when I came to, I was lying on the floor, and there was blood, a lot of blood, and my head was wet. I lay there for a bit, they moved me aside, swept up the blood, and washed it away with water. The doctor stood up, felt my pulse, and nodded his head: “You can continue.” And they pull me up again. But not for long, I couldn't take it anymore. I lost consciousness again, they lowered me, unwrapped me—and threw me in the isolator. Naked, broken—into the isolator. The stove was falling apart, with holes so big you could stick your hand in them. Forty degrees below zero, maybe even colder. They threw me in for the night—to freeze to death. And I can't walk, everything hurts, an unbearable pain, but I stand. I stood by that stove, and finally the sky turned black. It got so dark—and then the frost broke before morning. If that frost hadn’t broken, I would have never survived in there. And in the morning, they moved me to a warm isolator. But there was snow there too—snow on the floor and snow on the walls.

V.O.: That procedure, it seems, was called the “swallow,” right?

V.P.: Yes. I was lying in that isolator. There was… Vasyl knows, I already told him… A thief came in, stumbled, and fell on me. Then he started asking, “Who are you?” I told him who I was. “What, are you a Bandera man?” I say, “Yup.” “What are you in for?” I say, “For Pysarevsky.” “Was that you?” And he immediately started banging on the door. The guard came, and suddenly everything was straightened out for me, and they gave me food… And those thieves, you see, they would gamble away brigade leaders, even camp officials in card games and kill them; the guards were afraid of them. And so he knocked, and the guard opened the door for him right away. And I survived in that isolator. I started to move, to move, to move. That thief told me, “You have to move, if you don’t move, you won’t live... We know these tricks. This is the first time you've tried this, it won't be the last... Move, otherwise,” he says, “even your spine…” I started slowly moving my arms, my legs—I survived.

I survived and was sent on a transport to D-2. There, they took me to the smithy. The same kind of thieves came to me... They were also Article 58, but what kind of political article was it? They had messed up in the camp, sinned so badly that they were about to be killed. So a guy screams something about Stalin, how he’s a homosexual or something—they grab him and slap an Article 58 on him. And that’s exactly what he needs. He gets among decent people, where he has some peace. They slowly gather, two, three, five, ten of them—and they've already formed their gang, they’re already starting their business... What was it I forgot, where did I leave off...

V.O.: You said you were sent to some D-2. What is D-2?

V.P.: It was a camp in Kolyma, that was its name. They were building the largest thermal power station there. There’s coal there. It was supposed to be the second-largest in Europe, forty meters high. They built the walls—and it collapsed. They were building it a second time. And they took me on as a blacksmith; I was making anchors for it. They gave me a task—make anchors. This was in the years when Father Stalin was still alive. I would make the anchors, and then I would make something for people—a sleigh, or something for a cart, and one guy would bring bread, another would bring something to smoke. You know how it is, with the free workers. And I try to get things done. But they came to me to make knives—they needed knives. I say, “Boys, it's not happening today—I was given a task, and I have to make such-and-such. No, it’s not happening.”

An argument started. They started calling me names. One of them came up to me and punched me in the stomach. I was holding tongs with a piece of hot iron in them. I smashed him over the head with it—and he disappeared from in front of me. There were two others there. We got into a fight there… But that’s a long story to tell… For that, they gave me the isolator, then the BUR—the high-security barrack.

And then on to a transport. They took me—there are no more roads in Kolyma past this point—to Ayaskitovo, there’s a settlement there, a camp between the mountains, beyond the Chersky Range. They mine tungsten there. You work there for a year as a driller—and your lungs get so cemented that a knife can’t cut through them. The dust was so thick that a knife couldn't cut it.

The boys said right away: boys, this is death! Either we are men, or we are dead men walking—choose one of the two. Either we go drilling, or we all refuse. And you know, they had selected the most troublesome ones in that camp. Boys with spirit. We decided to fight for ourselves. They brought me in—I won't talk about the others—an Ossetian woman is sitting there on two chairs. I had never seen such a woman—so beautiful that I can't even describe her. She was so big that she had to turn sideways to get through the door. Her breasts were as big as two heads—like two pumpkins. A mustache like a Cossack’s. A real beauty, and tall. “Oho-ho!”—she spoke in a man’s voice. She looked at me: “Oh, here's a driller!” “I’ll do some drilling for you alright!” I said to her. “What’s with you?” “Nothing.” “Write him down for the brigade!” “No, don’t write me down!” I can't repeat what was said here because it was all camp slang... And if you don’t speak to them in camp jargon, they won’t understand.

V.O.: Yes, they wouldn't understand.

V.P.: And cry or don't cry—Moscow doesn't believe in tears. It was the same there. Cry, talk, crawl on your knees—nothing helps. Only with jargon [indiscernible] whoever talks to them like that—that's it, he's one of us, “our guy.” There's no other way.

And so we clashed there. They take me to the isolator, to the BUR, as a hooligan and a work-refuser. They filled the isolator with our boys from this transport. There were three hundred and sixty of us brought in. They packed us in. “Give us the latrine buckets!”—we needed a toilet. The administration came and said, “You will relieve yourselves and eat here, urinate and drink here. Do you know who you’re dealing with?” Someone shouted, “We’ll show you, you Chekist scum, how Banderites die!” They break down the first door. We clashed. There were about fifty of us in the cell. We slammed against the door and the doorframe—and the door, frame, and part of the wall came crashing down. The door fell near the threshold, leaving the Chekists behind. The boys burst out of the cell and started beating them. I shout, “Boys, don’t kill them!” Some Chekist managed to break free—his whole face covered in blood. And the convoy was behind us, behind the BUR, with machine guns. They shout, “Fire, they’re killing our men!” He let out a burst into the BUR. “But our men are in there, where are you shooting?” And would you believe it: the bullets pierced the wooden walls, tore the cotton out of people’s coats, and no one was even wounded. The bullets went right through the coats. Now is that luck, or what would you call it... He fired a machine gun like that—and it only tore the coats. And not a single person was even wounded. There are a hundred witnesses to that. Just like that.

We broke out and entered the main zone. I lay around for six months, and no one could [indiscernible]. I read books—there was a good library there. I read through that library; for six months, no one even touched me. After that, two trucks arrived, they chased everyone out of the zone, and filled two Black Marias. They were taking people alphabetically, and they didn't get to the letter “P.” So I remained in the zone. Then they called me in: go help the brigade leader close out the work orders. They say you’ll be closing out the orders because the brigade leader doesn’t know how.

I went to the brigade leader. He was very happy, said everything would be fine, he wouldn't wrong me. I sat there, and sometimes I would go out at night. And one night I went out—I think it was their October [Revolution] holiday…

V.O.: What year was this?

V.P.: 'Fifty-two, probably. Because Stalin died in 'fifty-three. They loaded those men into the Black Marias and took them away, and we stayed. I was sitting pretty there—living like a king. The guards and the military demolition men came out. They got drunk and started beating our zeks. So we grabbed clubs—and went at them! A fight broke out. They dropped their gear, lost their hats, and ran away. And at night they surrounded the work zone with machine guns in three rows, put us back in the residential zone, and turned our barrack into a punishment barrack.

I asked the men that no one should go to work, because we would rot; they would let us fester here. Don’t go to work, I said, let them call the prosecutor: the guards started the fight, they started beating us—and now they want revenge on us. We need the prosecutor... We didn’t go to work. The brigade of bracers, tracklayers, and lift cage operators. We didn’t go out, and the mine isn't working—that's it, a strike.

And the prosecutor for Dalstroy was a man named Vasilyev, I remember. And here comes Vasilyev. They call me in—lead the men to work. “And who am I? Who do you take me for, to lead men to work?” An argument started between us. I tell him, you remove the bars and locks from the barracks—and the men will go out immediately. Take the latrine bucket out of the barrack—and the men will go to work. He gave the order, sent the guards. They took them down—and the men went to work.

They went to work, but I didn't go anymore. But after a few days, they took me and Sorokolit—have you heard that name? He's a friend of mine—down to the factory, then put us in a Black Maria and transferred us to another camp.

In the second camp, it was the holidays. The chief of discipline there, I don’t remember his name, and his wife—they were very good people. They were Ukrainians—from Eastern Ukraine. She used to bring us things—they were paying us money by then—she even brought vodka! Cookies, sausages, candies, butter, cheese—you name it! She brought everything, even vodka and tea. And we celebrated the holidays—a whole barrack. Kolyma had never seen such a celebration! She brought some of that dwarf pine—a small kind of pine tree, we decorated all the barracks with it, lit candles. The tables were lavish—I’d never known anything like it. We sat down for supper, and someone informed on us—the Chekists came running. And then the boys started singing *"Boh Predvichnyi"* [God Eternal]—one man is crying, one is joyful, one is singing carols, another is holding his head in his hands. And the Chekists—they came to break it all up. They called for me. I say, “You go on home, boys—nothing will happen, everyone will go to work in the morning, I'm telling you. Nothing will happen, absolutely nothing, people are celebrating. They took our families, they took everything from us—now you want to take our religion too? We have nothing left—only today! Tomorrow, there will be nothing.” They refuse. So I grab him by the snout—come here, you scoundrel. And gave him some vodka. They got so drunk that their wives were running around asking where their husbands were. That's how the boys celebrated. They sang carols all night—outside, everywhere. The settlement folk with their children came out at night to listen—they had never heard anything like it in Kolyma, among those mountains.

In the morning, they went to work, everything was in order. They gave me a very good job—shoveling tungsten into sacks. When it was washed, in the evening I would shovel it into 50 kg sacks. A week later, we came back from our shift—“Pirus and Sorokolit—with your things!” Where to—we don’t know. I went to the storage room, got my suitcase, he got his. “We'll turn in our stuff—mattresses and all that.” We came out, and I see a Black Maria standing there. Sixty degrees below zero! It's dark. We drove down. The driver is afraid because the truck might stall—it's all wrapped in cotton, in blankets, that engine. It could stall and freeze, the cylinders could crack—and what would you do with the people? But the order is to go. A stove is burning in the middle of the Black Maria; they picked up 17 of us and are driving.

They took us over a mountain pass—they call it “Dunka’s Navel.” Dunka lived there, a woman, I don't know who she was or where she was from, but she was Russian. She built a hut for herself there—who built it, I don't know—and the drivers used to stop at her place. She would feed and water them there. And if they poured a thimbleful of gold for her (and she was very plump, heavy), then love would follow. And no one ever bothered her, because the drivers were all thieves themselves—they got out of the camps and wanted to earn money for the road home, to get dressed, get shoes, and so on. These thieves would spend the night there, rest, eat and drink, and make love for gold. So they named the pass—Dunka’s Navel.

On those passes beyond the Chersky Range, there are descents of 2-3 kilometers straight down. And so they send our Black Maria hurtling into the abyss from the top of that pass. The driver and the convoy commander jumped out, but they wouldn't let us out with the convoy guard and the dog. When they jumped out, the truck was on the right side of the road, where there were these concrete road markers, you know, to keep from veering off the road. The truck was breaking them—but what’s there to break, at 50-60 degrees below zero, you could hit one with your hand and it would shatter. The truck was breaking them, and its right wheel was thrown slightly to the right; it didn’t go straight, but a little to the right. And to the right was a mound of snow, as high as half of this house of ours, or maybe a whole house, but lower. The truck’s right wheel drove up onto that mound, and it tipped over. The Black Maria overturned, and the stove overturned and opened up—the fire is burning, the coats are on fire, the pants are on fire—fire is falling from the stove, smoke. The guard shouts, “Don’t get out! Forbidden!” “But we’re on fire! You’ll burn too! Open the doors, get out with that dog!” There were three of them. They got out, the smoke billowed, and we got out. I came out and looked—my dear God! My brain went numb: down, I don't know how many kilometers down—an abyss, cliffs. There wouldn't have been any bones left, not even the wheels would have remained.

A tractor came—the convoy guards almost shot them—and pulled the truck out. We got in, drove to Ust-Nera—a settlement on the Indigirka River. Then the convoy commander asks, “Boys, do you have any money?” “We do.” “Give it here.” He went and brought us vodka, sausage, cigarettes. And some for himself. “Since we’re alive—let's have a drink.” And the convoy commander went with the driver to find us a place to spend the night in the camp, because you can't survive a night outside—you'd freeze. Even in a garage, it’s still dreadfully cold. And so we got drunk there, but we told ourselves, “Boys, we won’t let the convoy down, we won't cause trouble, everything will be civilized.” And so we did. They took us to our lodging for the night. They took us to the camp banya after the prisoners were asleep, after ten o'clock. We went in after ten, there was a man on duty—no matter what we said to him, he didn't say a single word to us. A prisoner, a long-termer, not a word.

We spent the night. At five in the morning, they woke us up, led us out to the Black Maria, and took us to Magadan. In Magadan, I asked thousands of people in all the camps about that first Black Maria that took the men—and to this day, there's been no sight nor sound of them. That's what was supposed to happen to us too.

We arrived in Magadan. I had a very good job there—I worked as an architect, making these kinds of brackets for decoration. The architects made the molds for me, and I did the casting. And after that, they almost put me on trial because I was cheating: the quota was different.