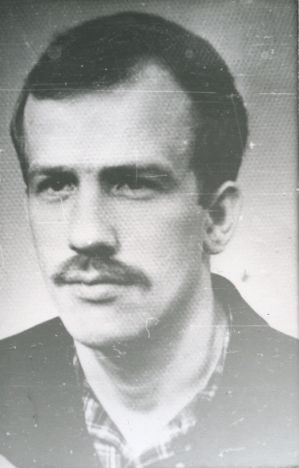

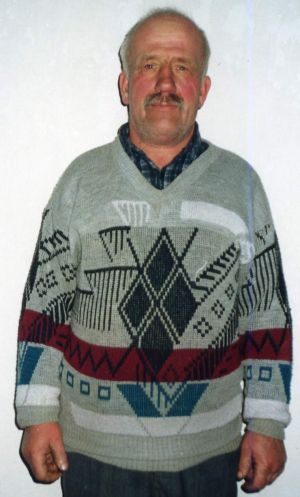

An Interview with Vasyl Ivanovych KULYNΥN

V. V. Ovsiienko: February 20, 2001, we are talking with Mr. Vasyl Kulynyn. Village of Nyzhni Torhayi. And what is the name of the district here?

V. I. Kulynyn: Nyzhni Sirohozy.

V.O.: Of the Nyzhnosirohozkyi district in the Kherson region. Recorded by Vasyl Ovsiienko.

V.K.: I, Vasyl Kulynyn, son of Ivan, was born on November 21, 1943, in the village of Lypa, Dolyna district, Ivano-Frankivsk region. My father, Ivan, son of Dmytro, was born in 1907. My mother was born in 1907 in the village of Sloboda-Bolekhivska, Dolyna district. Her maiden name was Pokryshka, and her name was Maria, daughter of Vasyl.

I was born right during the war, so I dont remember the war. But I do remember 1947, when they deported my paternal aunts because their husbands were in the partisan resistance. They didn’t take part in the fighting, but for their connections with the partisans, those two aunts were deported to Siberia, to Karaganda. They were in Karaganda. And their husbands had been killed.

My father and his brother Yurko were hiding and fleeing to the forest. One went low, and the other along the bank, and about five hundred meters from the church, he was wounded. He still ran a little further. His father hid him in the forest. Then the Muscovites chased after them, and my father escaped, hiding in a gully. But they took my fathers brother and then dragged him with horses... And they killed the second brother too. They didn’t take part in the fighting, but it was such a time that my fathers second brother also died.

My father also hid in the forests afterward. He was arrested, he was interrogated in Ivano-Frankivsk in 1945. But having gotten nothing from him, they let him go.

Before the war, when the first Muscovites came, my father was the village elder. He had only completed half a grade of Polish school. But he was a religious man, always working near the church. Elder—they call it a provisor, in church terms. He was a tithing man in the village, though he had no education. But it must be said that he was an honest man. There was respect for my father, and he was elected to such a position.

In 1950, I went to first grade. In those childhood years, I still saw how the Banderites fought for their state and how the roundups were carried out. So, around 1948, Muscovites came into our village and burned down a house in the upper part of the village. Banderites, insurgents, were hiding in that house. They killed them and then drove their bodies through the village—I remember that too.

And the main thing that I remember is 1952, there was a roundup, I was already in the second grade. I was finishing the four grades of school in my village. They came. They didnt even let us go to school. In 1947 there was SMERSH—that’s according to history. But I already remember—this was in 1952, for a whole week they searched for insurgents in our mountains. And it was under the guise of military maneuvers. Truth be told, I dont remember them catching any Banderites. As they say, their work was in vain. And the last battle in our mountains was in 1956. There was a battle, but they didnt catch anyone then either.

In 1954, I finished elementary school in my village. Then I went to school in the neighboring village—Sloboda-Bolekhivska, where my wife is from.

On religious holidays, I didn’t go to school because I was raised in a very religious family. For that, they almost expelled me from school in the fifth grade. They found some article that because I didn’t go to school on religious holidays, I was violating the rules. And they were going to expel me.

And my father strictly forbade me from joining the Pioneers. I didnt join, as a believer. This was the case in other families too. When they gave us the neckties, we would wear them at school, but on the way home, to our village, we would burn them. So every time, we’d get them. By the time we got home, wed have burned them. This went on for a long time. Then they saw theyd get nowhere with us. Not just me, but all the boys from our village who went to school did the same.

And with that symbolism—the trident. We often saw it (we grazed cows in the forests), how it was carved on trees. We carved it ourselves. Although, perhaps, we didn’t fully understand what it meant. But we saw all this from our youngest years. Thats why we formed the impression that the Muscovites, the Russians, brought us nothing good. And so it was instilled in us, little by little.

In 1957, I finished seven grades and went to the ten-year school, for grades eight to ten, now in the village of Vytvytsia. My father also didn’t let me stay in the dormitory. I didnt live in the dormitory, I rented an apartment. I lived in a private flat so that again they wouldn’t have the opportunity to recruit me into the Komsomol. At school (I finished ten grades), I wasnt a great student, but not bad either. I finished the ten-year school without a single C grade.

V.O.: And what year was that?

V.K.: In 1960, I finished ten grades. In the tenth grade, when I was already finishing school, they wanted to accept me into the Komsomol. Dmytro Kvietsko was the Komsomol organizer then. When they were supposed to accept me, he didnt even call me to join because he knew I wouldnt. He knew because Dmytro Kvietsko is my relative, my cousin. My mother and his mother are sisters. So he didnt even bother me. Instead, two teachers summoned me—Bilunyk and Petro Meleshko. They agitated me, saying this and that, that they had lived in such times, in 1948 they were almost killed, but they were in the Komsomol. I say: “No, I won’t join.”

So I finished ten grades without a single C. My homeroom teacher, Nina Ivanivna Berkish, wrote in my school record that the whole class was Komsomol, but I refused to join. There were two such students—Kateryna Deshyr and me. But her mother had been deported to Siberia, to Karaganda. So they didn’t even bother her—the daughter of an “enemy of the people.” But my parents were not deported. But my father forbade me because we are religious people. We are not allowed to be in the Komsomol because they are atheists, they are godless.

Thats how I was raised. And with that school record—there was nowhere to go—I enrolled in the FZO, in the Stryi Railway School No. 3. When I was enrolling, they asked me: “Will you join the Komsomol?” I said: “I will.” But I studied for two years, and almost before graduating, they asked again: “Are you going to join the Komsomol?” I said: “No, I’m not.” And I studied well there, too. They even kept me in Stryi for an internship at the “Metalist” factory. And then I passed the exam for a third-grade lathe and milling machine operator, and they kept me on at work in Stryi at the wagon repair plant. They even gave me a place in the dormitory there.

From there, I went into the army. In November 1962, I joined the army and served in Kalmykia in the air defense forces. After serving for three years, I was thinking of staying in the army. Not in the army, but they wanted to take me to teach math at a school (I know it quite well). They said: “Well send you to the correspondence institute in Volgograd. Youll study, get an education, and teach the children here at the school.” I write a letter home. My father says: “No, dont stay under any circumstances. Come home.” And I went home.

Back in 1961, when the blue-and-yellow flag was raised at the bus stop in Vytvytsia, I was summoned to the Stryi KGB. They asked if I might know who could have done it. I said: “How would I know?” I really didnt know who did it. And he says: “Well, if you find out, will you report it?”—“Ill report it if I know.” He kept me for a while, we talked for over an hour, and we parted on that note.

After coming back from the army, I went to work. According to the law, I was supposed to work where I was drafted from. They wouldnt hire me at the VRZ (wagon repair plant). I got a job as a lathe operator at another factory—the Kirov plant, forging and pressing equipment, the Kirov TPO. I found myself an apartment. Not the one I had when I was studying at the FZO, though. I was already working there as a lathe operator. I worked as a milling machine operator at the VRZ plant, and here I started as a lathe operator.

Around 1966, while traveling from Stryi, I meet Slavko Lesiv. Slavko Lesiv agitates me, saying there is such an organization—the Ukrainian National Front. And he knew what family I came from, what my attitude towards the authorities was. And I knew Slavko Lesiv too, because I was finishing the tenth grade, and he was in the eighth grade. He is two years younger than me.

V.O.: And what village is he from?

V.K.: From Luzhky. The village of Luzhky. His birthday is January 5, 1945. So the date on the monument is wrong. I agreed. He told me that a man would approach me, bring me literature. It turned out later we agreed it would be Dmytro. It was a Sunday, I happened to be at home. Dmytro Kvietsko approaches me. He brings me the journal “Will and Fatherland” and brochures, sealed, tells me how to distribute them, gives me instructions on everything. There was a brochure there—“Who are the Banderites and What Are They Fighting For.” Dmytro wasn’t afraid of me. He knew who I was, that I had even agreed.

In our village, there were some girls, I think from Dolyna or somewhere, doing repairs in the school. Dmytro and I went to them. We talked with them, and Dmytro began to agitate them. Dmytro told me to leave the brochure at the market, near the cinema, to it in a mailbox. He told me not to distribute it at my workplace, but at other factories. I took those brochures.

I did everything. My only mistake was that I dropped it not into peoples mailboxes, but into a collection mailbox. And they only found that one brochure, nothing else. This brochure ended up at the post office and they immediately handed it over to the KGB. They recorded when it was distributed.

I only got involved in 1966 and started working. I hadn’t even taken the UNF oath yet, and Mykola Kachur was already arrested in Donbas, they took him. We were already under surveillance. And I was still giving those journals to my close friends to read at work, and to Taras Kulynyn, my cousin. True, I didn’t give him brochures to distribute, only journals to read.

The second time they gave me an “Appeal to the Peasants” to distribute, an article about the Ukrainian language, the article “The Trial of Pohruzhalsky” about the Kyiv library. About the celebration of Easter in 1948—these were old brochures. There were new ones too, but there were still old ones. And again, but now unsealed, the brochure “Who are the Banderites?”. Just as he took them from the bunker, he gave them to me. This was again Dmytro Kvietsko who gave them. I went to his house in Sloboda and he gave me six issues of “Will and Fatherland.” Little ones like that. I took all of it. The brochures, all these articles I scattered in Stryi right at “Metalist” and at VRZ. There is a bridge at VRZ. I was walking across that bridge with someone else, we threw them—and again, nothing was found. Only this one brochure that I dropped in the mailbox—that’s what got me six years of imprisonment. And the journal was on my bed, under the pillow in my apartment. The landlady, when she was making the bed, found it and gave it to her son to read. And then, when they arrested me, she confirmed that I had such a journal. And they had no other evidence against me.

Dmytro Kvietsko, Mykhailo Diak, Zinoviy Krasivskyi, and Yaroslav Lesiv were arrested in March, between the twentieth and the twenty-third.

V.O.: Of 1967?

V.K.: 1967. They arrested me later, in April, on April 27 for the first time. I didn’t say. They put pressure on Slavko: who distributed this brochure in Stryi. At first, they only had one brochure. He told them it was me. It was my fault for dropping it in the mailbox. And it was his fault for pointing at me.

They came to my workplace. The director called me to his office—this and that, he told me. I see some guy in civilian clothes sitting there. I didnt know the ropes then: “Go, wash up and get ready. Come back here.” I went, changed my clothes. If I had been smarter then, I should have gone home quickly—to get rid of that journal. And there was another letter to me there. A young guy from Drohobych, who was doing an internship at our factory, I talked to him, he agreed that I would give him literature, and he would distribute it in Drohobych. I went to his home in his village. And he wrote me a letter. And he happened to mention that journal. I read the letter. I should have torn it up. No, I kept it to write a reply. And so, I washed up, and the KGB—bang—took me. They searched the apartment, found the letter on the bed. So I had to drag that boy into it with me… And Taras Kulynyn, that cousin of mine. Those were my witnesses, whom I dragged into it.

They held me for three days. It happened to be April 28, 29, and 30. And Easter was on April 30, and I was under investigation in Ivano-Frankivsk. They held me for three days. There was no evidence, I hadnt done much. I only said that I had read the brochures and the journal, given a friend an article to read about the language and about the trial of Pohruzhalsky. And they released me on April 30.

May 1 and 2—we have a village festival in Lypa. I came to Stryi, to my apartment. The buses to Stryi were still frequent then, I managed to get home for the festival. True, they were already scared at home, because they had started conducting searches there too. They let me go. True, I was under surveillance. On Monday, we had our church festival. I didnt go to church, but in the evening, I went to the store. Theres a club and a store there. My father told me not to go anywhere. But I say: “And why should I be afraid?” When I entered the store, a man there, Yosyp Levko or Levko Milchyn, by his street name, says: “Lets go, Ill tell you something.” I went with him. He says: “You hide under the bed, and I’ll call a man, and you listen to what we’ll be talking about.”

I crawled under the bed. The house was dark. He brings in Dmytro Kostiuk (while Im under the bed) and questions him. And this Dmytro Kostiuk had been an informer since the war and was still one. Dmytro Kostiuk says that some movement has appeared, Chekists are hunting them in the mountains. They created this aura that there were a lot of us, that we werent five people, but many more. And he reveals his connection. The other guy asks, and he tells. There is a teacher in Vytvytsia, Vasyl Petrovych Nosovych, who also taught me Ukrainian literature, and he himself was a church cantor under the Polish rule (this Vasyl Petrovych Nosovych came under the Soviet regime and became a teacher of Ukrainian literature). And another, a musician, Yanychivskyi (I dont remember his first name). Thats the connection. And there’s another one in Hoshiv too. All their agent network was laid out for me. But I didnt really trust that Levko back then, because he worked in the store, ran up a debt and they didnt imprison him.

V.O.: Ran up what?

V.K.: A debt, we call it *“manko”*. Thats the word. So it was hard to believe him. It was only later, when I was in the bunk, that I analyzed it and couldnt understand what it was—was Levko trying to save his own skin? Although this Levko, as a young man, had helped the insurgents—I learned that later.

Then I went to work, worked in Stryi. And it was only on May 26 that they arrested me for the second time. This time they came, wrote everything down, and locked me up. We were under investigation. It was May, June, July, August. In August, they handed us the indictments, and in November we had our trial. We were tried by a visiting session of the Supreme Court.

Taking into account that I was still young, hadnt done that much, and had supposedly repented, they applied Article 40 and gave me and Slavko Lesiv six years without confiscation of property. I didnt have anything anyway, I had just come from the army, so there was no property to confiscate.

Then they gathered us together. Me, Krasivskyi, Lesiv, and Stepan Tkach sat together in Ivano-Frankivsk in cell 99. What I really liked was the behavior of Zinoviy Krasivskyi. A man who had been through a very difficult school, but he was not broken, and he even convinced us not to lose heart, that everything would be alright. And no matter how much evil was done to him—he held no grudge against anyone. He was truly a saintly person. I only talked with him. That was in the cell. And when we were released, I visited him in Lviv when he was in the psychiatric hospital on Kropotkin Street, then at his home. My wife and I stopped by. He even took photos for us—of me, my wife, and our son Ruslan. And he never said a bad word about the people who had done him harm. And he didnt say anything bad about me either. Although I wasnt a saint during the investigation either, I didnt behave very worthily at the trial, you couldnt say I withstood everything.

I went through the Lviv transit prison, the Kharkiv transit prison, Ruzayevka, Potma—and ended up in Mordovia at the 11th camp point in Yavas. They immediately gave me a job—patching up defective furniture. I worked there for only a month. I didnt even earn enough for food, as I was not a specialist in this. They transferred me to the workshop to work in my specialty—as a lathe operator. I was familiar with that work, I had done it before. They put me on a fixed rate, I had a rate of thirty-five rubles. That was my rate, but from it, they deducted for food, for clothing. So I had little left over. I had a writ of execution. 410 rubles of debt, they were still deducting, and I was left with seven or eight rubles, just enough for the camp store.

V.O.: And when did you arrive in the zone?

V.K.: I arrived in the zone on February 20, 1968. And I grew a mustache then—I havent shaved it since. I worked. True, you had to go to political classes there, but we, the young political prisoners, neither I, nor Slavko Lesiv, nor the others—we didnt go to political classes. For this, they punished us. Not only were visits not allowed—they werent permitted for the first three years anyway. Because on the strict regime there are no visits, no parcels, not even the camp store for me. For a year and seven months, they denied me the right to shop at that store because I didnt go to political classes. But the people there were friendly—this Vasyl Yakubiak and Mykhailo Zelenchuk. Although my opinion of him is not very high, he did help me.

There I met the sixtiers. These were Bohdan Horyn, Opanas Zalyvakha, Mykhailo Osadchyi, Anatoliy Shevchuk, Ivan Hel (I still met him in the seventeenth), Mykola Kots (he came later), Mykola Horbal was there. Bohdan Rebryk—he was separate.

V.O.: Perhaps Levko Horokhivskyi was there? No?

V.K.: No. I dont recall such a name. Those were from the younger generation. And from the older ones—that was Ivan Pokrovskyi, with whom I corresponded for a long time. Ivan Fedoriv, Vasyl Yakubiak, Vasyl Pidhorodetskyi, Dmytro Besarab. These were the insurgents, the company with whom we sat, talked, drank tea.

When Honchars novel “The Cathedral” was published in the journal *Vitchyzna*, we studied it. Mykola Kots counted how many Russian words were in it and proved that Honchar was no longer writing entirely in his own language… At that time, educational work was carried out with the young political prisoners, we were taught.

At the eleventh camp point, there were no particular incidents. I worked, they punished me for the political classes. These were trifles.

They transferred us to the 19th zone, around June 1969. The 11th camp point was broken up into the third, nineteenth, and seventeenth. Most of us political prisoners ended up in the 19th—600 men. I also worked in the workshop there.

Once, in December 1969, a lecturer came from Moscow to give lectures on how well things were going, how much energy we produce...

V.O.: Per capita.

V.K.: Yes. How well we live. And my detachment chief—Ive already forgotten his name—suggests: “Lets thank him on your behalf for such a wise lecture.” And I, being stubborn, say: “And who asked for my permission—whether to thank him or not? We seem to be living well, but we buy bread from America?” Those were my only words. And thats it. And for that, they give me the punishment cell—seven days. They summon me to the camp commander and the “operative.” I am standing, and they are standing—the camp commander, the “operative.” They are wearing hats—and so am I. And they say: “Why dont you take off your hat?”—“And why should I? You take yours off—and Ill take mine off. We are equal.” For that, they add another three days—ten days. And this happened in December, between the fifth and the tenth. December 5 is Constitution Day, and December 10 is Human Rights Day. These days come, we declare a hunger strike, those of us in the punishment cell. And so that we wouldnt want to declare a hunger strike, after the 5th they immediately stop the heating, and even open the doors so theres no warmth. Well, to be honest, we werent too worried—they dont take us to work. I served those ten days—they let me out.

That was my first baptism. Before that, my life in the camp was quiet—I did my job, they had no complaints about me. Even when I was still in the 11th, I worked on two machines. And they gave me this extra porridge. I had no conflicts. True, the KGB would summon me, to break me, but Id say: “Ive done nothing wrong, I have nothing to repent for. I will serve my term.”

True, in 1970 they started making the regime even stricter. This is what Vasyl Pirus mentioned, that you had to do morning exercises—thats what they started introducing in 1970. In the morning, you had to get up, march in formation to the dining hall, in formation to exercises, in formation to work. And I say, I know when to get up myself, when to go to work, whether to eat or not. And Ill get to work early, because you had to work. And when they started introducing this stricter regime, the guard comes in the morning, time to get up. And I was still lying in bed. It wasnt bunks, but a bed. I didnt go to the dining hall to eat then, I came to work early, without the formation, to that checkpoint...

I came to work. Two guys from the second shift from the NTS—the Peoples Labor —come to me. Ive forgotten their names—two Jews. They say: “So and so. You’ve been punished with the denial of a visit (by that time I had already served half my sentence) and denied a package for violating the regime.” And they tell me: “You write a statement that you are declaring a hunger strike, and we will support you.” Without thinking twice, I went back to the living area and wrote a statement that I considered my punishment unjust, I had not refused to work. And from July 1, 1970, I declare a hunger strike. What was my mistake? I didn’t know the law that when you declare a hunger strike, you still have to go to work for three days, and only then are you isolated from people.

True, they supported me then—Slavko Lesiv supported me, and Anatoliy Shevchuk, and Ivan Pokrovskyi. About twenty of us gathered, and even those who agitated me for it, those Jews. But it turned out that I was the instigator, that I was the head of all this. And they put me in the punishment cell not for declaring a hunger strike, but for not going to work. Such a thing is possible.

They put me in the punishment cell. Without a mattress, without anything. And those who wrote their statements after me, so that this wouldnt spread—they didnt even keep them in the zone for three days, but immediately, with mattresses—to me, but into other cells. There were 17 or 19 of us on hunger strike then. But they were lying on mattresses, and I was on my bare knuckles.

I was on a hunger strike for 8 days then. It was my first hunger strike. On July 8, I came out of the hunger strike. The guys were great. Ivan Pokrovskyi is a very good person, he served a long time, such a conscious Ukrainian, he was the first to give me some milk, which he received, and some cookies. I ate one cookie and some milk—and was already full. But five minutes later, I wanted to eat again. So little by little, I recovered. After that, for the first time, I came to the kitchen to peel potatoes, to earn an extra ration, because I was hungry: in eight days, I had become very weak. But they didnt let me recover for long.

On July 12, we gathered—it was the day of Saints Paul and Peter and Fishermans Day. We gathered in a circle. Sat and talked. True, before that they had summoned me to a “kangaroo court,” the S.V.P.

V.O.: The “Council of Internal Order,” or “the bitch went for a stroll.”

V.K.: There was one Belarusian there, who had even helped the Germans fight, one Ukrainian, and another Ukrainian who had killed his boss because he wanted his job—Volodymyr Zahorodniy, himself from the Kharkiv region, and he was my foreman in the workshop where I worked as a lathe operator in the 19th. They start to grill me. True, the detachment chief—I forgot his last name—was a wise man, even though he was an officer, he didnt say anything to me, didnt condemn me. But these guys: “Oh! What right did you have? The Soviet government educated you, and you went against it and still wont reform here!” And without thinking long, I tell them: “You know what—you served the Germans for rotten fish, and you have blood up to your elbows. What right do you have to educate me?” I turned and left. And no one did anything to me. True, we sat around for that week.

And on the 13th, the four of us were sent on a transport. I thought, maybe from the 19th theyll move us to the third, Ill live there, or to the 17th, to that small zone where Vasyl Pirus and Dmytro Kvietsko were. But no—they bring us to the second camp, to the womens zone, there’s an isolator there. They keep us there for a week. They dont call us, nothing. We just sit there. That’s me, Stepan Zatikyan, who was later killed for supposedly causing the explosions in the metro in 1980 (they even summoned me here at the KGB and asked me about him). He was shot, though he was not guilty of that metro bombing, he didnt take part in it, but they needed to get rid of him. And two guys named Mykola are called. They were both from the Odesa region, both imprisoned for the NTS—the Peoples Labor . It was in fashion back then.

They kept us for a week—and then to court. We knew nothing terrible awaited us, just the *kryta* (high-security prison). At the time of the trial, those guys, the two Mykolas, had ten months left, Zatikyan—two years to the end of his term, and I had the most—two years, ten months, and ten days. At the trial, I also refused to stand up, I say that some cleaning ladies are judging me, I already know my sentence, that I have two years, ten months, and ten days of *kryta* left. They supposedly went to confer. Even the soldiers were surprised at how I behaved, they expressed sympathy for me.

They sentenced me, and then to Potma, to Moscow to Krasnaya Presnya, and to Vladimir.

V.O.: And do you remember the date of that trial?

V.K.: They took me from the zone on July 13.

V.O.: And what court?

V.K.: The Yavas court. They took us to Vladimir. I was at Krasnaya Presnya, that famous transit prison where you can fit ten thousand convicts. There are a thousand cells there.

They brought me to Vladimir in August. I was there for a month. Theres a law that if you get into a *kryta* from a camp, youre put on a strict, starvation ration—thats nine hundred calories. True, I got lucky—for some reason, they didnt throw me into a separate cell, but with other guys. There was Yurchenko, Aldov from Chisinau, and I dont remember who the third one was. Yurchenko was from Ordzhonikidze, from the Caucasus, but the third one—Ive already forgotten. And I was the fourth. They gave me the starvation ration: in the morning—tea (not tea, but water), at lunch—cabbage soup without potatoes, without anything, just water, and in the evening—porridge. And only 450 grams of bread. Well, the guys shared with me, so I didnt starve too badly that month.

After that month, they take me to Ivano-Frankivsk “for re-education.” I then went through Gorky, Penza, Kharkiv, Lviv, and Ivano-Frankivsk. They brought me to Ivano-Frankivsk. I had it good there after the prison, because they put me with a KGB informant, who had everything brought to him. He himself was supposedly imprisoned as a kolkhoz chairman—thats what he told me—for scheming. He had plenty of food. They brought him packages, so we fried cured meat over the toilet. Interestingly, while he was there, no one came in. As soon as they took him away (and I was being transported the next day), I also wanted to fry some, and suddenly—the door opens: a shakedown. Well, I had already managed to fry it, and had eaten. Nothing would have happened to me, but the guard was a woman (I hide the dirty plate underneath), she says: “Should I put you in the punishment cell or what?” And I’m being transported tomorrow.

True, my father came to visit me. He advised me to write a confession. But I write to my father that there will be no confession. [Unintelligible]. They, the KGB, promised to take me to a factory, that life is good, just repent—they’ll release me. I say: “No. Since I earned it, I will serve my term.”

They kept me there for a month for “re-education.” They also passed me a package. There was sugar, butter. So I took it with me for the guys in Vladimir. I dried a good bag of bread rusks. I didn’t eat the bread, because that informant fed me well. There was plenty to eat, he shared. I gathered it all up, not knowing that you cant bring bread into a prison cell, they dont allow it. For what reason, I dont know, because they let me bring sugar and butter into the cell in Vladimir if I managed to get it there, but they took all the rusks, not a gram was allowed in Vladimir.

And whats also interesting. On the transport from Ivano-Frankivsk to Lviv, they threw me into a cell with those on the special regime. There, God prompted me: share what you have, and I gave them a little sugar, a little butter. And I threw my own bag of rusks onto the bunks or under the bunks, because I was sleeping on the second tier—and I fell asleep peacefully, didnt even pay attention. And they, the common criminals, started playing cards. They wanted to take all my food. But I was lucky that there was one common criminal there who had lived for 62 years, and 38 of them he had served in prison. He was only free for 23 years. The last time he got caught was for feeling laundry in Kyiv, to see if it was wet or dry, and they caught him for that and—five years—to the special regime. Well, he got caught—5 years of special regime. And he was considered a thief-in-law. The first time he got caught wasnt for stealing, but because, while serving in the army, he killed an officer—it was either he kill him, or the other guy would kill him. And he tells them: “He treated you politely. He entered the cell—gave what he thought was necessary. He himself is going to the *kryta*. He has guys there, and hes taking this to them.” And he saved my food from being taken by those common criminals.

Whats strange is that in our Ukraine, they didnt care about political prisoners—they threw them in with common criminals. As soon as I got to Russia—thats it, a separate cell, even though there was no space. There was such a case in Penza, at the transit prison, that the prison was so full that there were no places, and they took me from the cell to the punishment cell. I spent that ten-day transit period in the punishment cell. They gave me bedding, fed me properly, the only thing was I wasnt in a cell, but in the punishment cell. For that, I got to walk in the yard in Penza as much as I wanted. It was winter, cold. But for an hour, or more, they didnt bother me. When I was done walking, Id say: “Take me back.” And this—one Penza transit prison, where they gave meat. For the first time in six years—that 46 grams of meat allocated, it was a little cube. That was the one transit prison where they followed the norms. In Gorky, I also had a separate cell.

I served a little over two years in Vladimir. When I returned to Vladimir, I was in a cell with Bukovsky, and with Ginzburg, and with Slavko Lesiv, with Gunārs Rode. And Yasha was his name, but his surname... it’s on the tip of my tongue...

V.O.: Suslensky?

V.K.: No, no, he left for Israel. There was even a conflict. I accidentally said something about Jews. We were going to the shower to wash in the bathhouse, and when he heard that word from me, he stopped talking to me. For as long as we were in the cell, he wouldnt speak to me anymore—he was offended because I called him a Jew.

When we were in prison in 1972 (it was a very hot summer, the peat was burning—in the Moscow region, in the Gorky region, and in the Vladimir region), it was very hot. And a law came out about the space norms in a cell. In prison, two and a half square meters per person were required, and in the camp—only two square meters. We measured our cell. We had ten and nine-tenths square meters, and thats including the latrine bucket. And there were six of us. And we—me, Slavko Lesiv, Rode, Bukovsky, this Yasha, and one old insurgent who was on his second term (the Dmytro Kupiak case: they arrested his people for a second time there was no one left to take from the old ones, so to maintain the fight against the Banderites, they tacked on a second term)—there were six of us in the cell, and we, five of us, wrote statements that this was a violation of the law on the detention of prisoners. Because it was stuffy here. We declare a hunger strike. Five of us declared it, but this old political prisoner didnt want to. That was his right. True, he stayed with us for one more day, and then they took him away.

The five of us were on a hunger strike. This was my second hunger strike, again for eight days, until the prosecutor arrived. We demanded: until the prosecutor comes. True, the prosecutor only came on the eighth day. And he started by saying that Khrushchev had promised that the prisons would be closed, but we have many common criminal prisoners, nowhere to put them. The prison is designed for eight hundred people, and here there are sixteen hundred, so be patient. True, after the prosecutor met with us, only four of us remained in the cell.

And so the four of us sat until the fall. Then they moved us to another cell, where I met Slavko Lesiv, Rode—a Latvian, Aleksandr Romanov from Saratov (we even corresponded with him), one old Latvian who didnt even want to communicate with us (he just sat silently). And there was one more, Vadim—a common criminal (who served in East Germany, escaped from there, they gave him a sentence, tried him as a political prisoner for treason against the Motherland). There were about eight of us there, and the cell was designed for ten people.

What I remember is how we celebrated the holiday. Pirus would also say this. In 1972, we celebrated Christmas. We made ourselves a Christmas tree. We, the young ones, didnt eat sugar for a month. We collected it, and then made a kind of *braga*. That Latvian, Rode, knew how to make yeast—he was a biologist himself. And we made ourselves some *braga*, learned carols, learned one Latvian song and one Russian song, so as not to offend anyone. Even that old Latvian sat down at the table with us for supper in the cell.

It was a beautiful Christmas tree! We sat at the table, tasted a little of the *braga*, however much there was, and sang carols. We sang carols until about ten oclock. The guards burst in—and started a shakedown. And they put us in the punishment cell. Nothing too terrible happened there. They didnt terrorize us much. They just did a shakedown, found nothing, and sent us back. They didnt even break up that cell then. Later, they transferred us from the first block to the fourth, where I, Oleksa, and Zraiko, the priest, and someone else fourth remained. We stayed in that cell until May, until my release, in the fourth block. When I was being released on the 22nd, Zraiko, the priest from Irkutsk, held a service for me in the cell.

And so God granted that they didnt touch me anymore. True, after I got married, I didnt get involved in anything else. But when they imprisoned Slavko Lesiv in 1980 “for drugs,” they wanted to imprison me too. In 1980, I was a foreman of a dairy herd, and a haystack of straw had burned down. That haystack should have been mine, but it turned out that I was the foreman—thats one thing, and secondly, that the haystack had already been written off, and they couldnt pin it on me.

And the second incident happened when our daughter Myroslava was born and we went to have her baptized in the Carpathians in 1981. Both my children were baptized in the Greek Catholic rite. I went to a woman to ask her to stay at my apartment while I was away. I was walking and ran into the managers son, Chornolys. It was just before Easter and the May holidays. I say: “What are you preparing for, Easter or the May holidays?” And I went on my way. It was already evening, around ten oclock. I spoke with the woman, made arrangements, and in the morning, I left for the Carpathians.

And that night, they set fire to that Chornolys, the manager, and broke the window of a bus. And it was all supposedly my work. And my godmother worked as the village council secretary there. And she says: “No, it cant be, because he left earlier. He wasnt here that night. He left a day earlier.” And she convinced them that I was already gone. Thats how God provided. And if they had found out that I left in the morning, they would have picked me up in Kherson. But as it was, she convinced them, I left peacefully, and then later, when I returned, she told me about it.

These were two cases when they could have taken me. It seems to me that there was such a wave back then. Thats when they took Slavko Lesiv. Once a quarter, the KGB would come, even the chief from Kherson came, they kept trying to persuade me to write a repentance. Whenever I went to the Carpathians—they would immediately summon me: “Why do you go there, whats so special there?”—“To visit my parents—thats all, nothing more.”—“And why do you talk to Pirus?” As soon as wed go to a festival—they’d report it, so and so. Theres a neighbor there, Stepan Krakhovetskyi, who wouldnt even let old Pirus take water from the well, because, he said, Bandera had come. And he himself is from the Carpathians, from Vytvytsia, where I studied. That was the attitude towards the old man. They even tried to frame the old man, as if he had stolen mixed fodder, nails, a bag, and they harassed him for it. So life here wasnt very cheerful, as they say. But thats fate. There was an opportunity to go to Kuban, but I didnt stay there, I came here instead.

And so they hassled us, until that perestroika happened. When perestroika began, it became a little easier. You could speak more freely. But thats just because people are quite different. Here, generally speaking, they dont attach much importance to having been in prison. As long as you dont curse the Communist Party. But to help with something, or to steal something for the household, some feed—thats easy. Give a bottle—theyll bring you anything. I even had a case. There was nothing to feed the pigs with. And I was working at the farm as a mechanic, and I arranged with the guys that I needed mixed fodder. They brought me the fodder, I gave them a bottle of moonshine for it. And the neighbor sold us out. We hid the fodder, threw it by the fence. And they came... Who came then? Zlobin and the head of the village council.

Wife Iryna: The head of the village council, Kopenko. Only the head of the village council came in.

V.K.: They searched, sort of, searched—didnt find it. You cant say they were bad people. As long as you didnt curse the bad government.

In 1979, they held a public trial for us here—for me and Pirus. True, Pirus didnt go. And from the district there was this Ivan Ivanovych Bistiuk, third secretary of the district committee: “Why are you such nationalists?” They summoned me, and there was a history teacher there too. She had a whole report. And for the first time, she reported in Ukrainian. They brought schoolchildren, she told them who the Banderites were, what Zionism was. It was so prepared. Im already leaving and I say: “What now? Should I just leave the village?”—“No. Live here for now...”

And so it went on, until the thaw came. In 1990, when it became easier, I wanted to become a deputy of the village council. I nominated myself. I went and asked, and they told me: “No, no. We have quotas—it has to be either a Komsomol member or a party member. Its not your turn yet.” And sure enough, they elected my neighbor, Ivan Milyn. But already in 1994, when there were elections, I ran for deputy of the village council. By then, the collective pushed me through—it had become freer. I was a deputy of the village council.

And in 1998, I became a deputy of the district council. What can I say about my time as a deputy? It was impossible to decide anything there because it was all directors, chairmen of collective farms, or school directors, or teachers, and moreover, of a purely Soviet upbringing. We have four communists in the district council. True, they switched to the “Democratic ” party. And 11 socialists. And all the others are supposedly non-party, but they all come from that system. So there, whatever was planned, thats what gets decided. The only thing I peck at them for is the state language. The first speech by the chairman of the district council was in Russian. I tell him: “How can that be? Well, let a district council deputy not know the state language, but the chairman of the district council should know it.” And now he tries to speak Ukrainian. Well, and I am also fighting for benefits for war veterans, which are now in the budget law, and for my own benefits and those of the Chernobyl victims. And I havent achieved a great effect. Except last year for myself. As it turned out later, they gave me subsidized gas. So here, in this regard, its still very difficult. In my opinion, if economic life were easier, at least a little better than it was in the , then people would believe in the state. But since the economy here is limping, and the people are not ideologically driven, we will have to think about that Ukraine for a long time to come.

I also wanted to recall how we celebrated Christmas Eve in 1970 at the 19th camp point. Just as old Pirus described, it was the same with us. About forty of us gathered then. Volodymyr Romaniuk, the priest, was imprisoned there at that time. Hes the one who later became the patriarch... I was imprisoned with him, and he conducted a service at a table in the 19th camp point. We sang carols so beautifully then! The guards didnt say a word.

V.O.: Wait! Volodymyr—in the world Vasyl Romaniuk—could not have been on the strict regime then. He was imprisoned in 1972 on the special regime. Perhaps it was the priest Denys Lukashevych?

V.K.: No, no. Volodymyr Romaniuk. Thats for sure. He was on the strict regime… Or maybe it was another priest—he was tall, and he conducted the service in the 19th. Then we sang carols. There were many of us there. Even guests from the Russian side were invited, Lithuanians, as old Pirus said. But the majority of political prisoners were from two nations—from Ukraine and Lithuania. And then came the young generation of Armenians. They had a national issue, they wanted Moscow to save them from the Turks. A new generation came. But by then I had already ended up in the *kryta*, so that was without me. But that was truly a holiday that has remained in my memory.

And now we live like this, managing our household. We fight a bit with our local officials. Now the land is being distributed, divided into shares. In my opinion, this should not be done in these steppe regions. These nine hectares that we have—we cannot survive on them. There should be an honest collective with honest leadership here. Then we will have some economic shifts and then we will have a state. Otherwise, we will have to wait a long time until we, as they say, have our own home.

My family composition. There are four of us. This is my wife. I got married in November 1975. I was looking for a place to live. I was in the Kharkiv region on a seasonal construction job. It didnt work out there. I went to the Kirovohrad region. A nice place—Bobrynets district, village of Charivne. The state farm was a leading one. They gave me a job. I worked as a lathe operator, earned very well for that time—170-200 rubles. And the director promised me an apartment, it was just being built. But when the KGB sniffed me out (and Slavko Lesiv was also working in this same region, in the Haivoron district, in Staryi Haivoron, in a boarding school), they thought I had come there to establish contact. They summoned me to the district KGB: “We will put you under surveillance.” They didnt even want to register my residence. But, knowing my rights, I said: “Well, you register me, and then you can put me under surveillance.” But they had no right to put me under surveillance because I was already under surveillance.

Not finding common ground with the KGB there, and then with the state farm director, I was forced to move to the Carpathians. I got married there. And we had nowhere to go, because my parents had six children, and that was in the village, and there was no work for me in the village. And in the town of Dolyna, they wouldnt register me. And my wifes family was also large: her parents had ten children. So we had to move.

When I went to the resettlement office and said I was moving (I wanted to go to the Bilozerskyi district, the conditions there were better), they said they only resettle people to the Sirohozkyi and Ivanivskyi districts. I told them to resettle me to a state farm, because I didnt want a collective farm. Because in a collective farm, a person at that time had no rights, whereas a state farm is a state enterprise, where there is legal protection.

They resettled me to the village of Velyki Torhayi, state farm “Khliborob.” The KGB arranged for me to be resettled to a Russian village, with a Russian school, where they speak Russian, when nearby is the village of Stepne—a Ukrainian school, and Myrne, in the Ivanivskyi district, which also has a Ukrainian school. Even then, the KGB was putting obstacles in my life.

They gave us a house as resettlers. We began to set up our household slowly. In 1976, our first child was born—our son Ruslan. In 1980, our daughter was born, on August 14. Both my children are baptized in the Greek Catholic rite. My wife and I took them to the Carpathians to be baptized. We did not abandon our rite. Although now, in these conditions, we had to go to the Orthodox church, of the Moscow Patriarchate, no less. And why—because when my son died, I needed to bury him with a priest. I couldnt find one here to bury him in the Greek Catholic rite. So I went to this priest and asked. True, he didnt take any money from me, because I had done a lot for him and for the church, and I do work at his home, and we also have discussions.

There was an incident when they were founding that church, I was part of the founding committee of twenty. They even wanted to elect me as the chairman of that committee. But that would have meant helping a priest of the Moscow Patriarchate, so I refused. But when an Orthodox priest of the Kyiv Patriarchate arrived, I helped him. He was a young priest, wanted a lot of money, in my opinion. He just wanted to conduct services, and for building the church—he wanted all that to be given to him, for the community to do it. And the community here is not very keen on that. They dont even donate much money when people go around collecting for the church. So he stayed here for about four months, that was in 1998, he conducted a service, blessed the Easter cakes, and after that, he fled to another place. And his place was taken by an Orthodox priest of the Moscow Patriarchate. With the help of the community, they set up a building—its not a church, but a church building—where services are held, and water is blessed, and, most importantly, people are now buried according to the Christian rite. When my brothers from the Carpathians came, they looked and said that I didnt make a big mistake by burying my son with the help of an Orthodox priest, and of the Moscow Patriarchate at that, because burying him without a rite would have been even worse. He conducted the service on the fortieth day, and at six months, and at one year, and on his birthday we go to him, and he holds a service for our son. Now, on March 3, it will be two years, so we are also thinking of hiring him for a service.

My daughter works at the post office in Nyzhni Sirohozy. After completing an eight-month course in Kherson, she now has a job and is studying by correspondence at a branch of the Kherson Technical University, in the accounting profession.

I work as a lathe operator at this farm, and my wife is now unemployed. She worked various jobs, then as a bookkeeper, then as a guard at the central office, and since 1999, she has resigned because other people need jobs. And the work is not paid. Its accrued, but not paid out. So its better to be around the household. It brings more benefit now than that job.

V.O.: And you haven’t yet mentioned the name of Mrs. Iryna and that she is from the Kvietsko family.

V.K.: Yes. My wife. Her name is Iryna. Her maiden name is Kvietsko, her patronymic is Mykhailivna. She is from the neighboring village of Sloboda-Bolekhivska, Dolyna district, Ivano-Frankivsk region. She was born, like me, in November, but on November 4, 1949. She graduated from accounting courses in Lviv and worked as a club manager in my village, where we met.

And another interesting fact. When there was persecution of the church, in 1973, she got me a document from the village council and I took it to Moscow when I went to visit Dmytro Kvietsko. More precisely, I was taking his sister for a visit. So I took that document to Moscow and gave it to the dissident Tverdokhlib (Tverdokhlebov). I dont know if he passed it on. My father kept listening and listening for any broadcasts about it from the West… Maybe it helped a little, because the church in my village was destroyed not then, but only in 1982. On October 5, they destroyed the church, and on December 22, my father died. It was such a powerful blow for him. He worked for the church all his life, on a voluntary basis, without a salary, without anything, but he worked near the church.

I would like to return a bit to my story. When we were released from prison in 1973, me and Slavko Lesiv (Slavko earlier, and I two months later), we went to visit Dmytro Kvietsko, or rather, his family, his cousin. And his wife was from Kolomyia, worked as a teacher, Zhenia. When we came and started talking, she threw us out of the house—we were not needed. This was in May 1973. Later, when perestroika happened, I came home for a wedding. This was already 1990. And on St. Michaels Day, I came to Sloboda for a visit and ended up at a concert. And that same Zhenia, who had thrown me out of the house then as a bad man, a Banderite, had already become such a patriot—more so than me!

Iryna: She was the secretary of the party organization.

V.K.: These turncoats amaze me—shes a teacher, she should have known more than me. And to change like that… They did, however, organize a national concert in Sloboda then, taught the children.

But what is strange is that these same teachers, with the help of the police, were destroying churches in 1982. In my village, in the village of Luzhky, in two villages they destroyed churches, and then they turned around so much that they are now giving patriotic concerts. How can one change like that? It seems to me that the reason lies in our long life under the communists, that people are not constant, only a few have firm convictions. And these turncoats—they hinder us very much, so that we cannot achieve a normal state, so that we can truly live in our own home.

What else can be said? My mother was illiterate. But she was deeply religious, and she had more honesty than those people who now have higher education. My mother raised six children, because the seventh child died in 1945, when my mother came from an interrogation and gave the child a cold breast—the child died. And she raised the six of us. The state did not give her a single kopeck for that. Although they offered, they wanted my mother to take money, but my father said: “No, I dont sell my children.” These people were not uneducated, but they had a conscience and did not want to have any connection with that state, with that system. And now—we would sell everything, just to survive. Whether to survive, or to get rich. Its not such a disaster yet, we are still living not badly.

I also want to return to the fact of when independent Ukraine was proclaimed. I was present near the Verkhovna Rada. I saw there how a woman prayed all day in the sun. That was truly a sincere prayer. But we forced the deputies, when they were leaving the hall in the evening, around nine oclock, we said: “Until you vote, we will not let you out of here.” And so it happened. Around nine oclock they proclaimed the independence of Ukraine, and after that, there was a rally on Independence Square.

A second incident happened in Crimea. When the Crimean Supreme Council voted for the Republic of Crimea. And there too, by force, this time the communists, forced the vote. And then we condemned this, that it was dishonest, unjust. But why didnt we compare, that we did the same thing? The people were not yet ready, even those deputies, to proclaim independence. It seems to me that it was all done by force, not by consciousness. If those deputies had truly realized that they were building their own state, we would not have such a deplorable state of affairs now.

There was an instruction from the Communist Party to vote for independence in the referendum and to elect Kravchuk as the first president of Ukraine. When I was distributing photographs of Chornovil and leaflets for Chornovil, they were torn down at my workplace on the same day. And when they put up a portrait of Kravchuk, they warned me, you better watch out, dont tear it down. I said I wouldnt tear it down. These communist agitators even went to the school. Theres a Mykola Lysenko here, lives in Nyzhni Torhayi, he was agitating for people to vote for independence and for President Kravchuk. Which is what happened.

In our village, 93% voted for independence, which I didnt believe—such high consciousness cannot be possible. Perhaps it was done by order. In our village, about 85% voted for Kravchuk, and the other votes went to Levko Lukianenko, to Chornovil. Thats how it was distributed. I know all this for sure, because I was on the election commission, they already included me then. I already had the right to control all this. I even had to buy a round of drinks for the referendum. I didnt believe that in this village... I was predicting 70-75 percent, not more, for independence. And it turned out to be 93 percent. It means we got our state by order along the communist party line. And they elected their own president. And where did this partocracy lead us? We see what deplorable consequences we have.

V.O.: This was Vasyl Kulynyn, a member of the Ukrainian National Front. February 20, 2001. Kherson region, Nyzhnosirohozkyi district, village of Nyzhni Torhayi. Recorded at midnight, by candlelight, as there had been no electricity for a whole day.