An interview with Viktor Mykolovych MOHYLNY from January 13, 2000, his author’s evening on November 21, 1999, the article “The Story of One Poem,” and a certificate from the SBU

V.V. Ovsienko: January 13, 2000, on Kutia, at 11 o’clock, we are having a conversation with Mr. Viktor Mohylny. Vasyl Ovsienko is recording.

V.M. Mohylny: My name is Viktor Mohylny, son of Tetiana and Mykola. My father was born in 1913, and my mother was born in 1917. I was born in a Ukrainian colony in the Volga region. That place was called Stavropol; now it has been renamed Tolyatti. I was about two years old when they took me to my grandfather and grandmother. They were the parents of my Kyiv. They lived on the outskirts of Kyiv, in a place called Chokolivka. That’s where the war found me. During the war, my parents were killed in the armed struggle against the German invaders. I was left an orphan.

Chokolivka is an interesting place, a true islet of the Ukrainian spirit, because in the post-revolutionary times before collectivization, many refugees, former insurgents, and former kulaks ended up there. They had simply figured out that they wouldn't be allowed to farm anymore, and without waiting to be exiled to the Solovki Islands, they scurried off to the city where it was quiet and lay low. They worked as gravediggers, did some construction [unintelligible], but they had a strong Ukrainian spirit, and I took something from them. But it was life itself that made a dissident out of me. On one hand, I did have certain well-developed instincts, and on top of that, life itself, those contrasts, the things you saw. At every step, you heard that the khokhols were traitors, that they were this, that they were that. We were told one thing, but something else was being done. And there was another incident. We had a homestead there, 14 hundredths of a hectare, and next to it was a kulak’s homestead. That kulak had a hectare of land, and they de-kulakized him—the leadership thought it was too much. By the way, this kulak had built—he was a blacksmith—he had built a plow and would till the land by harnessing his wife and daughter to it. That's the kind of kulak he was. Well, another interesting detail. His grandson eventually graduated from the agricultural academy here in Kyiv [unintelligible] and now specializes in forestry.

Chokolivka borders Chata Volynska (officially, Post-Volynsky. —V.O.), and Chata Volynska is a railway hub, and there was an NKVD outpost there. In what sense? They had their large warehouses and a prisoner-of-war camp. First for the Germans, then for the Hungarians. There was a contingent of guards there from among these NKVD men. This was in the forties, 1947... around those years. So they had a subsidiary plot there. On that kulak’s plot, they grew cabbage and other vegetables and guarded it. I remember there were two lads there. One was a Volga Tatar, Volodka Khovsky (?), and the other a man of the steppe, a Ukrainian named Mykola Karpiv. These boys had been chasing bandits before, and then they were transferred here to finish their service. They would come to our place to borrow a mug or a bottle. We had contact with them. They once recounted a combat episode with the Banderites. So I ask him: "And what were they fighting for, who were these Banderites?" He says: "Nationalists." "What were they fighting for?" He says: "For an independent Ukraine." "And what," I say, "is an independent Ukraine?" "Well," he says, "it's on its own, not dependent on anyone." I say: "And is that a bad thing or what?" "Well, it's not bad, but they won't let us have it." So I already viewed this Banderivshchyna, as they called it...

There were many caricatures back then. I remember one on the central department store: they had drawn Franko with an ax, Tito with an ax, Bandera with an ax, and Uncle Sam holding them on short leashes—that sort of thing really had an impact on your psyche... These questions were hard to figure out. Although my grandfather had been a volost commissioner for either the Directorate or the Central Rada, a patriot he was, but when I asked him such questions, he would tell me, "Listen, don't talk about that, or they'll get you arrested. You," he said, "observe everything yourself and draw your own conclusions; people won't always tell you the truth. You watch, observe, and think." These were the conditions I grew up in. And since I was the type who got to the bottom of everything, I had conflicts with my teachers too. I could never get along with the Ukrainian language teachers; nothing worked out. Well, let’s take at least one such contrast. Some commander put Lermontov forward "for an award," but the tsar himself crossed his name out. And what, exactly, was the award for? For burning down auls?

I had such misunderstandings at every step of my life. When you look and don’t play false with your soul, but just cut through those doubts you have. And if you look closely at any ideology, you’ll find many things that don’t hold together. And the poorer the ideology, the weaker it is.

But this is all just lyricism. I finished seven grades and entered the polytechnic school of communications.

V.V. Ovsienko: What year was that?

V.M. Mohylny: In 1952, I enrolled in the polytechnic school of communications in Kyiv. They did allow us to take the exams in Ukrainian, but the instruction was in Russian. Well, I asked questions, why is it so. The answer was: “This is a polytechnic of all-Union significance.” As if to say, they would send you anywhere for work. But here’s the catch. It’s practically a mystery to me how children who had finished rural schools could enter any educational institutions. Because what did I observe there? In my own group, who studied and graduated? Those who finished school with "excellent" marks—they were admitted without exams. But when classes began, we had a test dictation in Russian. And the top student, a boy who had a medal, made about 50 mistakes in that dictation. But to get in, you had to write a Russian dictation. Practically none of them could write it, because in the village, the teacher didn’t dictate “vada,” “vazmi,” “paydi,” “ulybatsa”; he dictated “ulybatysia” [the Ukrainian phonetic way] and so on. So he simply couldn’t write it correctly here. Yes, there were Muscovites studying there, who had come here because they felt at home in their native element. But I had to stumble along. I had to relearn this mathematical terminology, the physics, and so on. Well, what kind of knowledge did I have from school? I didn't even have textbooks. My knowledge was weak. This caused me some discomfort, a feeling that this was mockery, an outrage against me: I am on my own land, but I'm being taught in God knows what way.

In my second year, we put out a wall newspaper. There were older guys there who had come after their army service, so I gravitated toward the more experienced ones—I didn't have parents, so I intuitively gravitated toward the older guys. A wall newspaper is a nasty thing; it's used as a tool of terror, they start criticizing you. So we took it into our own hands. I published it in Ukrainian. It was the only one in the polytechnic. I was 15 or 16 at the time. And back then I was writing little poems, as a child, I read Shevchenko. But when I finished the polytechnic, I went to Zakarpattia in 1956. They sent me to Uzhhorod. There was a polytechnic of long-distance communications there. I took a wife from there, from the Kuchmash family, Aurelia, Oronka.

V.V. Ovsienko: Can you state the name more clearly?

V.M. Mohylny: Aurelia from the Kuchmash family, Oronka, or Oron—that’s in Hungarian. It's the Latin translation of Aurelia. All the graduates were sent to different places. But I came back on vacation and saw: everyone’s here, in Kyiv. And I had even more right to stay, since my grandfather, my de facto father, was already over seventy, and so was my grandmother. So they would have left me here, but I was used to playing fair, by the rules—if you have to work off your assignment, you have to work it off. So I went to the Ministry of Communications and told the head of the personnel department: "Listen, your daughter was also assigned somewhere, but you kept her in Kyiv. Let me stay too, change this up; I don't play by such rules." Well, I stayed here.

In general, I tried to communicate in Ukrainian back then, not only with friends but everywhere. And once you start speaking Ukrainian, conflicts would just stick to you at every turn. I developed a way of communicating that wasn't lyrical—it was prickly; it didn't bother me, I knew how to fight back. Even in those times, there were people who still... As sad as it is, the Ukrainian language became a kind of banner, as they say. It essentially became a symbol of resistance... It’s truly a pathological phenomenon, that in Paris or London, the local language would become a banner in a struggle for something. It's understandable when the Germans occupied Paris... But here was the sovereign Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Now one can say something about it, but back then this communist ideology was considered indigenous. After all, Vynnychenko himself wrote that if it weren’t for the bayonets of Ukrainian peasants and workers, would Moscow have ever taken hold? It relied on the workers; their ideology found fertile ground here. And yet, there were even bus conductors who, in those days, made a point of announcing stops in Ukrainian. There were other signs, names, forms of greeting—that spirit still smoldered, it survived.

But then there were the little poems, those literary studios. The literary studios—why was I drawn to them? I was scribbling little poems, so scribble away, but I needed to communicate. As I said, a lot of things were unclear to me, so I tried to understand. You analyze, and here too, as they say, not everything added up. It was just when the cult of Stalin's personality was being debunked. They turned him into a cannibal. But at the same time, they said the real god was Lenin, and what came from Stalin was just some harmful deviation that perverted the sacred idea. Well, so I went to the University of Marxism-Leninism, to the history department, to get to the truth, to study this Lenin. I studied there for a year.

V.V. Ovsienko: When was this?

V.M. Mohylny: That was 1960, I studied for the 1960–1961 academic year. I took the primary sources, those volumes—and again, nothing added up for me. I saw that it was a lie, the tricks of a hunter who wants to catch his prey, fooling it like they catch a pike with a lure. But I was already getting my poems published. The Dnipro publishing house printed a selection. And in Odesa, they had those month-long seminars for young creative people, so they recommended me. I got to the first seminar in Odesa in 1961. It was probably the most productive one. Who were the participants of this seminar? Anatoliy Shevchuk...

V.V. Ovsienko: From Zhytomyr.

V.M. Mohylny: From Zhytomyr. He's Valeriy's brother, not as famous, but a most interesting man, no doubt about it. Mykola Vinhranovsky was there, but not for long, about two weeks. There was Leonid Tyndiuk from *Molod Ukrayiny*, Valeriy Yuryev from the steppe region of Ukraine, he has passed away now. Borys Demkiv, Yuriy Koval—the executive secretary of *Zhovten*, a journal in Lviv, it has a different name now.

V.V. Ovsienko: *Dzvin*.

V.M. Mohylny: *Dzvin*. Mykhailo Bakhtynsky, a young Ivan Illienko, they say he's passed away too. A few other people. And the supervisors were Volodymyr Pyanov and Borys Buryak—interesting people. The next seminar, the following year—Iryna Zhylenko wrote about how they pecked at her there, it was just strange for me to read. Mostly, the protégés of district newspapers, the promoted ones, got in there, so you can imagine... We also had a few, as they say, "wolfhounds," but there was no spirit of pinning labels on anyone. They would tug at you for technical clumsiness and so on.

So it went, I wrote those little poems, corrected things—I was gaining some sort of culture.

But what happened next? There were quite a few of those studios. There was the "Molod" literary studio, but it was a trough-fed studio, located at the publishing house; you’d get noticed there, editors would walk by, so you’d make some connections. In a creative sense, it offered practically nothing, it was so ossified. There was also "Siaivo" in the park named after the 21st Party Congress.

V.V. Ovsienko: What is it called now?

V.M. Mohylny: Could it be "Nyvky"? It's hard to say... It's near the Beresteiska metro station, Khrushchev's dacha used to be there, and before that, it seems it was Lyubchenko's dacha. The place was nice, and the studio was there too; the head was Gelman—a fine Jewish fellow, an educator himself. Among them, there are people who understand that young people won't toe the line 100 percent. Well, it was customary there to have a studio entourage, for there to be some "ears" [informants], and a ritual where the studio members would compile a list of who was present each time; everyone knew what it was for, and some kind of immunity developed. But there were hundreds of us. However, no matter how much you wrote, there was a monopoly on publishing. If you wanted to get published back then, you had to listen to your inner censor; he sat inside you. He would tell you: write about flowers, or this, or that, but don't touch this topic. And if you went too far, well, so be it. I was never angry with them for not publishing me the way I wanted. But they did publish something, after all. I’m saying that reality itself provoked a person to certain reflexive actions.

It was 1965, spring, the day of the vernal equinox. Around March 24th or so... I thought it was the 22nd... I was working at the Paton Institute then, in the electrothermics laboratory; my boss was Oleksiy Bulyha, he has passed away, he was a most interesting poet. This laboratory was near the Arsenalna metro station. So he and I got off at the Bilshovyk metro station (it was the last stop then) and went into the *Molod Ukrayiny* office. And a rather interesting contingent of editors and literary workers had gathered there—progressive lads. By the way, they were later dispersed, their military department credentials were annulled, they were swept into the army, and then scattered across Ukraine. Some managed to hold on, like Dmytro Stepovyk—he somehow slipped through and now specializes in Christian history. They say there’s supposed to be an evening in memory of Shevchenko at the Gorky Machine Tool Plant, Dziuba will be there, and some other things. So we went to this evening. And this "Siaivo" studio existed under the patronage of the Zhovtnevyi District Party Committee, and the Zhovtnevyi District at that time included the present-day Leningradskyi district, that is, Sviatoshyn, and covered everything, because the machine tool plant also belonged to it. The evening was to take place in the club of this machine tool plant. I see Dziuba standing there, I saw someone else, greeted them. And the head of the literary studio, Anatoliy Yakovych Gelman, and a few studio members are standing near him, waiting for something. I ask: "What's going on?" Gelman hesitates, doesn’t say. And then some bustling man comes up to him. "He's not one of them, is he?" he says to Gelman. And Gelman says: "He’s one of ours." "Well, you see," the man says in Russian, "too many of those who speak Ukrainian have gathered here, so there won’t be any evening." Well, the literary studio members were no fools either, they say: "So let's give them a fight!" "No fights in whatever year of Soviet power!" Now you smile, it seems like an anecdote, but back then it grabbed you by the soul, like a hundred devils. Not only is the evening in memory of Shevchenko being held at the last minute, almost at the end of March. It would have been held at a high level, and, no matter how you look at it, Shevchenko did work for their ideology. No, here some despot jumps out of the bushes. Well, what are you going to do? The group went its own way, but the choir, "Zhaivoronok" I think, turned into the Lenin Komsomol Park, where that statue with the hammer stands... And there, after I left the Central Telegraph, I had a long pause, I couldn't find a job. Gelman helped me; I became the manager of the reading pavilion, he paid me 60 karbovantsi. There was a small hollow there, a dell. The choir stood there, they sang "The Testament," "My Thoughts." It was neat, it sounded beautiful. And by then cars had driven up, druzhynnyky with blue and red armbands. It was the first time I'd seen where they found such people. It was like some national-communist Ukrainian guard. The police ‘bobiks’ arrived. Should we sing something else? And then Vasyl Stus says: "So what, are we just going to sing? You see, our militsiya has arrived so that hooligans don't bother us, so let's talk about something, maybe someone will recite a poem." Well, a wise man, he wasn’t looking for a fight with them—he says, you see how we honor the memory of Shevchenko, say what you will, it’s a solemn moment. Then they started reciting poems. Bulyha, I remember, was reciting, someone else was reciting. And I was wearing a light raincoat, and I had just gotten a haircut. I was cold, trembling like a puppy. Someone gave me a hat, but what good is a hat for warmth… And the guys say: "You go and read a poem too." So I stood up and read my "Fragment" and "The Wind." In "Fragment" there are lines that mention a sawn-off shotgun and blue-eyed Muscovites. And in "The Wind": "and in the city without a storm, the flags are suffocating." Well, in context, it tickled some nerves. Then they started blubbering about how I was calling for Muscovites to be slaughtered.

They held meetings on Saturday and Sunday. The district committee met on Saturday, the city committee on Sunday. They were up in arms there. But they didn’t touch me. Then word got around, they dug something up, because Bulyha says: "You’re being summoned to Khrenov"—he was an academician, head of the electrothermics laboratory. Bulyha had also read poems, but he didn't have those Muscovitisms. "So you talk to them gently there." "Ah," I say, "how am I going to talk gently—they spat in my soul, and now I’m supposed to talk gently?" So he went himself, had a talk, says that these poets—they're perverts. And who's going to do such a volume of work for that kind of money? This is some kind of science, technology, you need results there, not ideology. So it all blew over. But there's intelligence everywhere. They ask, what's to be done with this Mohylny? The party authorities answered: "Do what you want." And Bulyha had just gotten sick with erysipelas, with cancer, this was the end of 1965. He died at the beginning of 1966, in February. So they laid me off, but the very next day they hired someone else for my position. I already had some connections, I couldn't get a decent job, but two Jewish men got me a job as an electrical fitter at the "Lenkuznia" factory; I had helped both of them with their dissertations. And so it went. This, so to speak, was one of my feats.

Now for another incident. There was a tradition of laying flowers at the Shevchenko monument on May 22nd. Of course, this date should be celebrated, but I’m not a fan of laying flowers for an idol, because a graven image is still an idol. I believe that one should hold the image of a hero, like God, in one's heart, in one's soul. But since our own people gathered there, a certain microclimate was created. True, it was stuffed with "ears," but our own spirit dominated. And since I am a hardened smoker, I stood off to the side, having a smoke. The situation escalates. A lad from the theater institute is reciting. And they were provoking. Some soldiers were walking by, listening to a Spidola radio. And some militsiya official called them over and said: “Turn it on full blast and go into the crowd.” I had a word with that soldier, I say: "What are you, some kind of mutt? What, is he your boss, some cop? You're just walking by, trying to pick up a girl—so get going." He left. So, this student was reciting, and there are lines about "brothers from the East," and here are two ranks of militsiya. They grabbed him, dragged him off somewhere. And it turned out that I, who had been standing in the back, ended up in the front when everyone turned around. Cries of indignation began. And then some lug suddenly—wham!—pressed my arms to my body and, like a sack of straw, like a sheaf, he picked me up, carried me in front of him, and shouted: “Who’s the fascist? Who’s the fascist? Who’s the fascist?” And his boozy breath on the back of my neck. But he was a big lug. He carries me to the bus, and I see they’ve already grabbed someone else there; I was the last one. They bring them by the arms, and there, two huge goons grab them by the hair and pull them into the bus. But my head was shorn, so there was nothing to grab me by. He shouts: “Sit down! Sit down!”—in that Levitan-esque voice. I figured it out right away, they’d give me 15 days—unpleasant. But then I see that the crowd that had gathered there starts running, they run up to the bus—and that Levitan-esque bass voice breaks into a falsetto, shouting: “Close it! Go! Go!” And they bolted, they didn’t pack the bus, though they probably wanted to bring in a lot more people. Well, they brought us in... The militsiya station was near the Shchors monument, there are some buildings there now, the Botanical Garden on one side, and this was on the other side.

V.V. Ovsienko: Is that on Shevchenko Boulevard?

V.M. Mohylny: On Shevchenko Boulevard. Well, as they say, the militsiya were hostages. They understood that we hadn’t done anything improper. We heard some voices: “Come out, get in the car.” Very polite. True, when we arrived at the militsiya station, that goon was also politely telling us to get out. But here the politeness was a bit different, not official. We got in the car, and they brought us to Kalinin Square, today's Maidan Nezalezhnosti. There were a few dozen people here—Mykola Plakhotniuk, Nadiya Svitlychna, maybe I recognized someone else. They ask: "Is that everyone?" I say: "Seems like it."

V.V. Ovsienko: And how many of you were there?

V.M. Mohylny: They argue about whether it was four or five. It seemed to me there were four, maybe I wasn't counting myself.

V.V. Ovsienko: Do you remember the names of the people who were detained?

V.M. Mohylny: How would I? I didn't know any of those people. There was one lad there, we started talking, and he turned out to be Jewish, he says: "I'm just here out of curiosity." Plakhotniuk was trying to get to the bottom of this, they were writing some letter, recording the names somewhere, but that wasn't my concern.

It was already May, the days were long, maybe they grabbed us sometime between seven and eight in the evening. And they let us go, probably, at the start of the next day. This was 1967; the *Vitryla* almanac had just published my work, there was a positive review of my little book *Zhovta Vulytsia* (Yellow Street). They were releasing “cassettes” back then, several small collections in one package. And then they return my manuscript for a larger collection. If only they had written the truth, but I'm a trusting person. So I went to the publishing house. Vil Hrymých was the director there. He was a man of letters, after all. The director there, I think, was some sort of wedding general. But with this one, you could talk. He tried to weasel his way around it a bit, and then he says that it doesn’t depend on him—there's the Central Committee of the Komsomol, go sort it out there. Well, I went to Tamara Hlavak—she was the same as what Kravchuk was in the Communist Party.

V.V. Ovsienko: She was the second secretary of the Komsomol Central Committee for ideology.

V.M. Mohylny: Ah, well, so even higher than Kravchuk.

V.V. Ovsienko: But in the Komsomol Central Committee, not the Party.

V.M. Mohylny: I say, this is what happened, what's going on? She tried to do something—but no, where could she? "Pagan motifs..." I say: "But that's a good thing, pagan motifs—that's practically atheist propaganda."

V.V. Ovsienko: What, did she speak Russian to you?

V.M. Mohylny: She spoke Russian to everyone, but sometimes she could say something in Ukrainian. They were like collective farm foremen: all the collective farm foremen in all the collective farms spoke Russian. Just like they speak Russian to dogs even now, in independent Ukraine. And then she says: "No, you need poems there that would prove your loyalty." "That may be so," I say, "but what kind of loyalty can there be? My whole life testifies to it; I wasn't brought here from America." "Well," she says, "give me a few poems like that, and then it will go through." I figured: this is nonsense. And that’s where it ended. Then came the events in Czechoslovakia… I had an article published, "We Must Find a Common Language," about the letter Ґ. When they were restoring communism in Czechoslovakia, they regretted having acted rashly by publishing that little article. These are my feats.

When I was working at "Lenkuznia" as an electrical fitter, an electrician, they sent me on business trips a few times. Once to Vyborg, once to Tashkent, just before May 22nd. I later read in Kasyanov that this was one of their methods of re-education: the Party would send down a directive on whom to send to the second shift on that day, whom to send on a business trip. (Kasyanov, Georgiy. *Nezhodni: ukrayinska intelihentsiya v rusi oporu 1960-80-kh rokiv*. Kyiv, Lybid, 1995. 254 pp.). Just imagine, what a demonstration of power: they could play with a person like a cat with a mouse—either this way or that. This was 1967, May 22nd, Plakhotniuk organized a march to the Central Committee. The militsiya intercepted them somewhere, and Holovchenko himself, the Minister of Internal Affairs, came out to meet them in a vyshyvanka. He was in civilian clothes, in a vyshyvanka, and he says: "I’m a member of the Writers' Union," speaking Ukrainian, "just disperse. We’ll sort it out, the boys got a bit carried away, it's already late."

And then he showed up at our place, at "Lenkuznia," and was saying something there. I also wrote him a little note, saying, listen, on May 22nd your boys are going to get carried away there, it’s already happened. He started reading it, and next to him was some little colonel: "Whoever wrote this, after we finish this conversation, come over, we'll explain it to you in detail." Well, fine, I stayed behind to wait for the explanation. But this was after work. And most people are attacking him with what? It's "Lenkuznia," it had its own rules. You graduated from a vocational school, even if it was affiliated with Lenkuznia, but you're not registered anywhere, you're just drifting around. They draft you into the army—you drift around there. You come back, they give you a bunk in a dormitory, but no registration. And so what? You continue drifting, and to get on the waiting list for housing, you need five years of Kyiv registration. So he'd hang around for another five years without registration. Dozens of people like that rushed to Holovchenko to sort out these issues. And each one is explaining something, it's a matter of life. Well, I waited out one, then a second, a third, and then I see, well, what am I going to hear from them? It's just a taunt. So I turned around and went home. But a few months go by, they call me at work, I'm summoned to the shop foreman, they say there's a call for me on the city phone. I pick up the receiver, and a voice says it’s from the Regional State Security Directorate—they named a place somewhere near the Young Spectator's Theater—"drop by after work, there’s a matter here."

Well, I dropped by. They show me this note. As if to say, look how clever we are, we figured it out. Well, what can you say? If I had your resources, I would have figured it out in ten minutes. "And why is there no signature?" "Well," I say, "it’s not customary to put signatures on these notes. If it’s a crime, let me sign it right now. He could have asked who wrote it, I would have stood up, I was sitting in the first row, not hiding." I say: "And why the hell did they pack me off? They could have at least apologized, or something." Then they tell me to write down the poems, the texts. "Well," I say, "I don't remember." But I had to write some kind of explanation. I wrote something there, but I said, what bothers me more is that I can subscribe to the "Voice of Yakutia," but I can’t subscribe to this Ukrainian Warsaw paper "Slovo" or the Prešov "Zhyttia" or something like that, this is socialist Czechoslovakia, after all.

This was 1972. They had just locked up Kholodny (February 20. —V.O.). One of them blurted it out, trying to get something out of me, saying that Kholodny was blaming me for things. I don't know what I would have done in his place. We were in a slightly different position. And so we parted. And then—well, what are you going to do, they, as they say, beat you and don’t even let you cry.

Some little poems were being scribbled, in '78 I scribbled that “Autobiography.” My wife had been seriously ill since she was forty—her heart, one heart attack after another, I couldn’t lift my head, just spinning on inertia. On top of that, the status of a worker—you're cut off from everything. They had closed down the studios by then, otherwise you could have gone there, even if you were old.

You see, I am stressing that I practically never showed any initiative; the situation found me on its own.

I was interested in philately. I started looking for letters from "учреждений" [institutions]. They used to write a sign on them—"учреждение." Because there's a branch of philately—collecting letters from places of confinement. In the USSR, only letters from prisoners of Nazi concentration camps were valued. But in the wider world, they all are valued. And in the USSR, when letters were displayed at philatelic exhibitions, they would cover up a stamp with Hitler on it with another st it was undesirable to display it. But abroad, they displayed all the letters. I managed to get a few letters; I had connections with philatelists in the West, with Ukrainians. I sent them several letters to America through Czechoslovakia and Poland, and they displayed them there. They had some of their own stuff too. It is, after all, a document that exposes the GULAG. Oles Shevchenko was more active; after all, he was the executive secretary of the *Biokhimichnyi Zhurnal* (Biochemical Journal). He had access to the UGG, or UHG as it was called then.

V.V. Ovsienko: The Ukrainian Helsinki Group.

V.M. Mohylny: Helsinki. I don't remember what prompted it anymore, but the fact is that he and I went to see Oksana Meshko. By then, all the men had been imprisoned, only Meshko was left, and, as they say, the nominal members who were sitting somewhere. And Rudenko had already been imprisoned, and Berdnyk, well, whoever was here. And I had a "Moskva" typewriter; they asked me for it. They later took it away from me during a search. They were talking; she had a "Russian-Russian conversation book" there.

V.V. Ovsienko: Ah, I know. (A device with a film on which one could write with a stylus. Then you would lift the film, and the writing would disappear. —V.O.)

V.M. Mohylny: I took that very memorandum...

V.V. Ovsienko: The Helsinki Group Memorandum?

V.M. Mohylny: Yes, and the Declaration, to retype them. So I took them, I'm retyping, and of course listening to Radio Liberty. And not a single dog is barking about our people being in jail. Only the Russian-language "Liberty" talks about the Jews, but it’s as if nothing is happening here. I say: "Kume,"—and Oles Shevchenko is my kume—"listen, you have some connections in Moscow, so I'll translate it into Russian, and you try to somehow get these materials over there. And you can explain verbally that the Ukrainian Group is no more, only Meshko and these prisoners are left. Because," I say, "what can we do, where can you make a move here in Kyiv?" Well, he actually did it.

V.V. Ovsienko: What, you really translated the Declaration and the Memorandum?

V.M. Mohylny: We translated them, and he took them and gave them to Hryhorenko's wife. And the next day, the radio was already chattering on about how everyone was in jail. Meshko got alarmed, she had some plans of her own there, but we got it done.

Then there was another little story. Oles comes to me, brings a piece of shielded cable and says: "You're a specialist, what could this be?" I say: "It's a shielded cable, maybe a television antenna." "No," he says, "it's not an antenna." "Then what?" "Well," he says, "the neighbor above me exchanged apartments. And the new neighbor was re-laying the parquet floor and found a whole bundle of cables like this, leading to my place, and five more branched out from there under the parquet." So he asked, what kind of cable is this. And I say: "Well, I didn't install it." "Well, I just," he says, "pulled on it and yanked it out. The bastards," he says, "rigged up some listening equipment." Well, I've read detective novels, how they plant a "bug" the size of a millet seed, and here you have this... Well, it just doesn't fit. They would have had to get an agreement with the previous owner, and that's an extra step, because you have to pay for silence—no, it didn't fit with my logic. So I say, "Kume, something's not right here; well, the cable is indeed high-quality, but it doesn’t say what it’s for, maybe the wiring in this radio device was done with the same kind of cable."

So it went on and on, and then on March 31, 1980, just as I had changed my clothes after coming to work, they summon me to the shop foreman, they say the HR department is calling for me. I'm dressed in my work clothes, but he knew where I was being summoned to, he says: "You should change into something clean." "Ah," I say, "so what for?.." He fell silent. Well, you feel better when you’re in your work clothes. I go into their office, they give me a warrant, God knows what kind, I read it, I understand all the words, but the meaning—no. But I have to keep a straight face. They say: "We're going to your home." It must have been a warrant for my arrest. They put me in a black "Volga," brought me here, saying something like—"distracting questions." They brought me in and asked: “Do you have materials related to the Khmara and Shevchenko case?” Of course, I have nothing. So they searched and searched and found some things.

V.V. Ovsienko: And what did they find?

V.M. Mohylny: Well, what did they find? They took all the manuscripts, I had a diary, some samvydav was there, some letters.

V.V. Ovsienko: What samvydav did you have?

V.M. Mohylny: "Among the Snows"...

V.V. Ovsienko: Valentyn Moroz's "Among the Snows"?

V.M. Mohylny: Yes. Mykola Kholodny, some undelivered speech of his, they even took “The Sword of Ares.”

V.V. Ovsienko: Ivan Bilyk’s book?

V.M. Mohylny: Yes. A couple of small journals, a typewriter. I regret the loss of my diary. Although it was inconsistent, I didn’t make entries every day.

Well, so this whole thing spun up, they want to make a witness out of me.

V.V. Ovsienko: A witness at the Shevchenko-Khmara trial?

V.M. Mohylny: Yes.

V.V. Ovsienko: So, did they summon you all the way to Lviv? Where was the trial?

V.M. Mohylny: The trial was in Lviv. They sent a summons twice. The first time they canceled it with a telegram, something didn't line up for them, and the second time I was there. But was that a trial? It was God knows what. They herded in boys from vocational schools as spectators, and they wouldn’t even let the families in.

V.V. Ovsienko: What did they question you about there?

V.M. Mohylny: They asked me silly things. There was one interesting thing. They incriminated Oles in the publication of the *Ukrayinskyi Visnyk* (Ukrainian Herald), and they incriminated him in distributing anti-Soviet literature—he had given Doroshenko's *History* to someone. He had given it to me too, but I wasn't listed as a defendant, so for the sake of appearances they found another character who confirmed this fact. But this incident with the UHG—they didn't touch that. In a private conversation, they talked to me about it, laughing at how Meshko got alarmed when the information went abroad, she had the whole of Kyiv up in arms here. And they said: "You were with Oles at her place, weren't you?". Because the question arose of what I had retyped: "Where did you get it?" I said: "I got it from Meshko, where I was retyping it from." "And you were with Oles at her place?" "Well," I said, "I don't remember." "That’s all clear," he says, "we’re not prying too much." The question was not: you retyped it, so where did those copies go, that one copy went to Moscow? That question was not raised. It's a mystery. What kind of mystery? They just let Oles slip through their fingers. By all laws of logic, they should not have let him leave Kyiv. So they were masking this event. That could have been one version. And another KGB man gave me an interesting thought when I was getting my certificates later, he says: "Well, they weren’t acting independently—they were acting according to a Moscow script. They were told to play it this way, so they staged this whole performance." The *Visnyk* hadn't been published for five years, but they dug up something old. Oles gave me this *Visnyk*, and I was supposed to confirm it as a witness.

V.V. Ovsienko: So, that must have been issue 7-8, right?

V.M. Mohylny: Yes. Well, Chornovil didn't acknowledge it.

V.V. Ovsienko: He didn't, that's right.

V.M. Mohylny: So what was I supposed to confirm?

V.V. Ovsienko: From whom you received it, to whom you gave it to read?

V.M. Mohylny: No, I'm a witness, I am, as they say, a person with an untarnished reputation, and Oles is the criminal; he used me as an object of corruption. I was supposed to confirm that he gave me this *Visnyk*. That's one thing, and the second: in what context was that “Autobiography”? The “Autobiography” was supposed to figure in it. But the fact is, I forgot that he had given me this *Visnyk*. He gave it to me without the title page. Some time had passed, a few years. It was just when they were dragging my wife to the hospital, so I only skimmed it in places. And a lot of samvydav material passed through my hands, so it didn't stick in my memory. When did it all unravel? You see, a silly thing happened there. You heard how Oles tried to shield me: he said he stole the “Autobiography” from me, he gave me the *Visnyk*, but he did it rashly, without thinking, he gave it to me without the title page, and that Mohylny returned it the next day and said that he doesn't read anti-Soviet literature. In other words, he was portraying me as a positive Soviet person. When they showed me that testimony, I said: "Listen, that's not how it happened." And they kept telling my kume Oles that if you’re going to deny it, we’ll imprison your kume too. I say: "The thing is, my kume is covering for me, you see, he's taking the blame himself. That’s not how it was. I wrote this ‘Autobiography,’ but you see, from a technical standpoint it’s imperfect, and who could I show it to but my kume? So I gave it to my kume. As for the ‘Visnyk,’ I couldn't say it was an anti-Soviet work because I hadn't read it; I refrain from categorical conclusions." Well, to them, you're still confirming the fact, if not head-on, then from the side.

They summoned me dozens more times, so it really frayed the nerves. And at the same time, they were delicately trying to persuade me to cooperate with them. I considered that option. But they immediately and skillfully drove a wedge between his family and me; they know how to play on emotions. They would say: "If it weren't for this Mohylny—he's the one who corrupted Oles, look at him, he’s walking free, while he turned yours in." It worked one hundred percent. And he had two little girls, his wife Lida fell gravely ill from all this stress. The way they manipulated things! So I think, to hell with it, after all, an idea, honor—these are all conditional things, but a human life—that's a reality. I told them straight out: "Will you release Oles?" "No," they said, "that train has already left the station. He shouldn’t have pulled that wire." That’s when it hit me. Well, of course, if he still had the wire, where would they take him? Nobody kills the goose that lays the golden eggs.

One more piquant detail. We need to draw some connection to the modern SBU. For me too, after those events, it took a long time to settle. Why did I end up in complete isolation? The neighbor above me, she was a simple woman, worked as a janitor, a cleaner, a former Ostarbeiter. But her son was in and out of jail, petty hooliganism: broke a kiosk, a shop window, a bottle, something like that. And when they started trying to turn him into a repeat offender, they got to her. She would go out in the morning to sweep, a conscientious woman, sweeping until around noon. So they chose a time when my children had gone to school, my wife was also working somewhere part-time, no one was at our place, and they say to her: "Someone in your building is listening to the 'Voice of America,' so your son might fall under its influence." She was a Stalinist, she prayed to Stalin as if to an icon. They say: "He might fall under harmful influence, so we need to save the man, to identify who it is." Well, so be it, she left everything for them… But then they told her, don't tell anyone, but she confessed to me. She just begged: please don’t tell... But another neighbor asks: "Who was making all that drilling noise at your place?" She says: "Even the neighbor said, he was doing something there, didn't clean up properly, but I still found the holes, between the parquet floorboards." I analyzed that there must have been some installation here. When I contacted the SBU a year or two ago to get my manuscripts and diary back and to find out the status of this equipment, they didn’t satisfy all my demands, because you can feel that it’s the same guys. And they completely ignored my inquiries about the listening devices, as if I had never asked, though I persistently mentioned it in all my applications several times. Well, the essence of the state probably doesn’t change, and the essence of the state services remains the same. And as for the poet, they say that a poet is fated to be an eternal dissident, if he is a true poet. So there you have it.

So, you see, that’s our life. But matter is indestructible, and the spirit is also a material thing, so it cannot be destroyed either. Well, that’s probably all.

V.V. Ovsienko: Tell us about your family.

V.M. Mohylny: I have two children. My daughter Dzvinka, born in 1960, she’s a telephone operator, and she has a son, my grandson Bohdan.

V.V. Ovsienko: And when was Bohdan born?

V.M. Mohylny: In 1982. He inspired the children's poet in me. In fact, from about 1984 to 1988, I was learning to write children's poems. I used the pseudonym Vit Vitko, and two little books came out: "Ravlyk-Muravlyk" (The Snail-Ant) and "Hoyda raz, hoyda dva" (Rock Once, Rock Twice).

V.V. Ovsienko: In which years were they published?

V.M. Mohylny: In 1988 and 1989. As Ivan Malkovych said, they received a favorable press. I also have a son, Attila, he’s a fairly well-known Ukrainian poet, he also has several books.

V.V. Ovsienko: What year was Attila born?

V.M. Mohylny: Attila was born in 1963 (September 16, 1963–September 3, 2008). So, I was playing around with these children's poems, and then I had a whole lot of work to do. I never left my job at "Lenkuznia," and to master the technique and all these various tricks—because, unfortunately, the genre of children's literature is poorly developed in our country—it practically consumed me entirely.

But when this liberation movement rolled in and reached its apogee, the so-called perestroika, taking advantage of my position at "Lenkuznia," I also made some waves there: I was the co-chairman of the strike committee, I took part in the rally skirmishes in Kyiv—in strikes and similar actions, "Lenkuznia" played one of the leading roles. But then I rethought it. After all, when you are a citizen of an empire, you have one psychology, but when you become a citizen of an independent state, the scales fall from your eyes, and you begin to see some things in a clearer light. And so it happened. The materialization of this became my latest little book, "Chokoli-vko, chovkay meg..."

V.V. Ovsienko: Can you state the title more clearly?

V.M. Mohylny: Csokolivka, csokolj meg!, or The Bitten Apple: Chimeras. —Stolytsia, 1999. – 43 pp.

V.V. Ovsienko: So that's in Hungarian, right?

V.M. Mohylny: Yes.

V.V. Ovsienko: And how does the title translate?

V.M. Mohylny: It translates literally as "Chokolivka, kiss me." It’s a play on words. So I took the genre of the British limerick. As they say, I sifted it through the sieve of Ukrainian irony, Ukrainian folklore, and concocted something like this. Essentially, the problems that existed remain the same, because a person is born free, but from the first step, from the first breath, they try to turn them into a domestic creature that submits to certain dogmas, rules of conduct, and morals that are convenient for the powers that be, the anti-humans. On the other hand, everything in the world is relative. For example, that same well-being. Look at the well-being of a Ukrainian chicken—it reaches its full size in a year, and for that year, it runs around the yard. So it actually lives for a year: it sees a bug or two, it can even look at the sun. But an American chicken—they pump it full of antibiotics, and it grows up in a month and a half. Apart from a cage and antibiotics, some concentrates, it sees nothing. Both end their lives on the dinner table.

It's the same when you look at the standard of living. Take a Ukrainian worker and an American one. It's like one feeds his horse chaff, the other oats. The one who feeds it oats can put a heavier load on his cart, while the one who feeds it chaff has to push the cart himself. An American worker won't run off for lunch and come back with a bottle; ours does. It's all relative. But life—it is beautiful, and let it be as it will be, and it will be as God grants.

V.V. Ovsienko: That’s what Bohdan Khmelnytsky used to say.

V.M. Mohylny: Yes. This conversation took place on January 13th, of the Ukrainian year two thousand.

V.V. Ovsienko: Two thousand, you don't need the "th" there. Thank you.

* * * * *

Viktor Mohylny's Author's Evening

V.V. Ovsienko: Viktor Mohylny's author's evening at the Museum of the Sixtiers on November 21, 1999, was opened by Mykola Plakhotniuk.

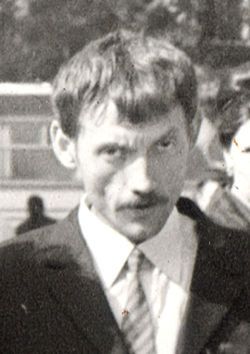

M. Plakhotniuk: I came to his house in early spring, it must have been March, the snow was melting, it was dreary outside, but when I entered the house, I found a complete comfort, one that resonated with my own soul. The house was all painted with Cossacks, Mamais, hopaks, inscriptions, like in a cave with rock paintings. One person had written this, another had drawn that, but it had such an aura that I was immediately drawn to these lads, to this group. It turned out that they had been meeting once a week before this. It was some kind of informal circle. If it had been 1972, of course, this entire circle would have been sent rumbling off toward the Urals all together. But here was such a circle. True, they understood very well that it was very dangerous, because where more than three gather, there's bound to be a commotion. Yarynka, Viktor’s wife, would walk around the house at that time, through the surrounding alleys, and check if any cars were parked there, or if anyone was coming. All they did there was read poems, discuss them, and prepare for the next sessions at the literary studio at the "Molod" publishing house, which was led by Dmytro Bilous. They were already armed to the teeth, reading their poems there, defending their positions. That’s where I met Viktor. Evidently, he “lit up” back then, and so it’s not surprising that they didn’t let his books go forward. And to this day, until the end of the eighties, Viktor did not publish a book of his own. Only in the eighties were his children’s books published, "Ravlyk-Muravlyk" and "Hoyda raz, hoyda dva," under the pseudonym Vit Vitko. And now his little book is circulating in samvydav under the pseudonym Vykhtir Orklyn—you'll break your tongue, I don't know why he chose such a pseudonym. Just look at the photographs, what he was like back then when we met.

He had a wonderful wife, may she rest in peace, she passed away two years ago. Yarynka, Aurelia, a Hungarian by nationality, from Uzhhorod. In Kyiv, she became more Ukrainian than all of us put together. She stood up for the Ukrainian cause and was a very fine, good companion to Viktor Mohylny.

Back then, in the sixties, on the initiative of either Viktor Mohylny or Mykola Kholodny, I don't know, a literary studio for worker-poets called "Brama" (The Gate) was created at the Club of Creative Youth. Viktor Mohylny was also a member. They took Liubov Panchenko as the artist, and Aurelia Mohylna was their translator. In 1963, when I first met them, Dzvinochka, his daughter, was a little girl in her mother's arms, and her mother was already expecting the future poet Attila Mohylny.

And that’s how I met Viktor Mohylny.

Years passed. Whoever reads this samvydav book of his will see that the KGB was very keenly interested in him, he was under "prophylactic" watch by the KGB because he was connected to the cases of those lads who were arrested, in particular, Oles Shevchenko and Vitaliy Shevchenko. He was constantly summoned to the KGB for interrogations, they traumatized Attila. Attila was a very little boy. That’s what kind of family this is. I'm keeping it short, because I said I wouldn’t be long, but it’s turning out long. And meanwhile, his adult book has not been published.

When we had an evening here dedicated to Alla Horska, we talked about him speaking. "No, I won't." Well, I somehow persuaded him, and today Viktor Mohylny will be reading his poems, and his friends will talk about his technique, his creative work, the means of this creativity. [Next, children read children's poems].

Bohdan Demyanenko:

Вчора (с. 5 збірки «Csokolivka…»)

Вчора дрізд прилетів із Китаєвого.

Тільки хто тепер тут покатає його?

Вже поснули автобуси

На блакитному глобусі –

А чи сниться їм вірш із Китаєвого?

Bohdan Plakhotniuk:

Лелека

Чи то клопіт, чи не клопіт?

Загубив лелека чобіт,

Загубив і не шука, не шука,

Босу ногу заховав у рукав.

Ти б ніколи ногу так не взув.

А лелека ще й дратує козу:

Не стояти козі

На одній нозі.

Біля Бродів (с. 37 збірки «Csokolivka…»)

Чи не вчора біля Бродів

Чорногуз ріллю скородив?

Чи лелека, чи то гайстер, а чи бусол садить айстри

На городі біля Бродів?..

Отаке собі (с. 20)

Отаке собі ходило

Теліпатися на тирло.

Як упало, то й не встало…

Ну, тоді вже не ходило.

V.M. Mohylny: ...Because almost all my old teeth have fallen out, and the new ones are growing in slowly, I feel a bit out of my element, because the dynamics aren’t the same. My grandson made a list of poems I should read, but the thing is, I can't keep up that pace anymore. So I made some adjustments. That is, I'll read a few poems from the sixties. Around the mid-sixties, I had already acquired, so to speak, a poetic culture. Although the first poem my memory recorded, I wrote somewhere in late winter or early spring in the third grade. I remember it like it was yesterday, I was sitting at the first desk—well, I didn't sit there myself, they made me sit at the first desk. Right next to the teacher's desk. We had inkwells back then, so I even dipped my pen into her inkwell. And next to me they sat such an obedient little girl, such a little girl that no one would ever pull her pigtail. She listened to the lesson so intently... And then inspiration struck me. I fidgeted a bit and wrote on the last page of my notebook; it took up about a quarter of the page. The main thing is, it was a masterpiece. I wrote it in free verse, though I didn't yet know how to break it into stanzas; I wrote it out like the "Our Father," in prose style. And in the next row sat a friend of mine, he was two years older, the strongest boy in the class, he later became a motorcycle racing champion. We formed a tandem. I tore out this masterpiece, folded it, and said: "Pass this to that girl, Borys." And I myself was staring at the teacher like a stone so she wouldn't catch my gaze. But I hear such a roar of laughter, these two boys burst out laughing, and the teacher, like a cobra, shot over there. She was something, Zinaida Zakharivna, with such black hair. She confiscated my masterpiece. And I could already see her twisting his ear. She was unceremonious and would twist it until tears welled up. And then what does she do? She stands in front of the class and says, you had a laugh, you were reading something funny, now I’ll read it. And on the third syllable or the third letter, she stumbled and turned red as a beet, because the masterpiece was, as they would say now, erotic. She stumbled over the profane language. And then she conducted an investigation and found out the origin of this work. She sat down at her desk and wrote a message to my grandfather, because I lived with my grandfather and grandmother. It was a mix of a political and a pedagogical masterpiece. And to drive a wedge between Borys and me, she sent him as a courier to give it to my grandfather. Well, nothing particularly interesting happened after that. As they say, I drew a conclusion. My enthusiasm waned, and it was only in the sixth grade that I returned to poetry, when an epidemic started—all the boys suddenly started writing poems. But I had concluded that I could write masterpieces, because the effect was colossal. My grandad appreciated it; he was a witty man. But there could be consequences that are impossible to predict.

Well, and here are the little poems; by 1961 I had learned to write a bit. I’ll read a few. Again, free verse. Well, free verse is no innovation; it’s ultimately a fraud, because what are the "Psalms of David"? But to pull off a poem in free verse—that’s top-tier skill, because in a regular poem you have rhyme, some alliteration, you can play with that. But free verse—what is it? You’re drawing a rainbow with a single-color pencil. Here you really need great technical skill, teeth. [Reads the poems "Through Your Crystal Threshold," "They're Burning the Stalks in the Gardens," "Fragment" very quietly and with some interference, barely audible].

I also had a poem, "The World." It was masterfully translated into Hungarian by Yuriy Murashov; it sounded better in Hungarian than in Ukrainian. I don't remember it now, to be honest. I have a little poem, "The Danube." This is a river that is full-flowing and full-blooded in almost every other Ukrainian song, but somehow we don't even perceive it poetically beyond those few dozen kilometers of the left bank that currently belong to us. But since it is full-blooded in the songs, then sooner or later, it will become a central river of Ukrainian poetry. [Reads the poem "The Danube": I couldn’t come to you…].

Now, one of the signs of our democrat is that he has to make reverences and demonstrate a love for Jews. But I was ahead of these trends by about three hundred years. [Reads a poem, unintelligibly].

Well, something from the seventies is needed. [Reads the poems "These Houses, Like Family Crypts…"; "They Came Out of the Forest…"; "Flock Together, Simple-Winged Birds…"; "Willow Leaves…" unclearly].

Mykola Plakhotniuk: Viktor Mohylny is a great philatelist. He collected stamps all his life, conjured something over them, and now he compiles and publishes a journal. A worldwide journal, in fact, right?

V.M. Mohylny: The editor is over there, you can give him the floor later.

Kobzar: One of the Ukrainian songs, in the original, as it is recorded in our songbooks. It is very relevant even now: "It’s been two hundred years since the Cossack has been in bondage." [Sings to the accompaniment of a bandura].

Yuriy Murashov: I need to add something to what Mr. Mykola said about Viktor. I would like to say this. They say here—a talented children's poet. Well, you've heard the children's poems, and for me, he was indeed a children's poet, because when I met Mr. Viktor, I was a child in an ideological sense. I was a child who simply loved Ukraine. Honestly, I had only heard before that there was such an anthem "Shche ne vmerla Ukrayina" (Ukraine Has Not Yet Perished), and I heard it for the first time in this very house. And it was Mr. Viktor who was my spiritual father in the sense that I heard from him what true Ukrainian nationalism is. Can you imagine: you come to a worker, a proletarian, and all his walls are covered not only with inscriptions but also with books. This is a home warmed by thought and cigarettes, a home with no great earthly riches, but where great, great spiritual riches are gathered. This man could not get a higher education because, as I heard, Viktor came to an exam on Ukrainian literature and drew Shevchenko’s "Kateryna." He is an absolutely sincere person who has never lied in his life. He is a unique person. And he says that Kateryna is Ukraine, ruined by the moskal. And he gave his analysis of "Kateryna." Understandably, in those days, he was very lucky to have made it home at all. (Laughter). But his knowledge... If you needed any information... Let’s say, the SVU case. "Mr. Viktor..." "Ah, it'll be ready in a few days." And there you have the stenograph of the SVU case, a little book published somewhere. It was in his house that I first learned such names as Mykhailo Dray-Khmara, Mykola Zerov. I remember how we read in this house, passing from hand to hand a little book—for us, it was something otherworldly—Ivan Koshelivets’ "On the Contemporary Ukrainian Literary Process" (Perhaps "Contemporary Literature in the Ukrainian SSR." —V.O.). This book caused a great revolution in our minds because in it we read things we had never heard before.

He was truly a good mentor for children, because we were little children then. And it was there that we grew into men. If we can now say that we have some convictions, then it was the poetic talent of Viktor Mohylny that greatly helped these convictions to grow and strengthen. He had no agitprop poems, but "Fragment," which we heard today—I was just thinking, "Could it be that Viktor won't read ‘Fragment’ today?"—that "Fragment" was with me all the time in my head. It wasn't written down anywhere, but it was always in my head, it warmed me, it always sustained me. And when you're in a situation where you might falter, you feel that you’ve already been enlisted into the hundred-man company of a chieftain whom you can no longer betray. That's the kind of Vit Vitko he is. And he's also Toka Mykolashyn, and he had many other pseudonyms because he wasn’t published.

He was the first in Soviet times, in those sixties and seventies, to write an article, "We Must Find a Common Language"—in defense of the letter "ґ". And this article was published in 1968 in *Literaturna Ukrayina*. They don't mention it now. The letter "ґ", even now, though it has been rehabilitated, is being introduced into modern literary publications with great difficulty. And back then, he broke through with it in *Literaturna Ukrayina*.

Do you know what his strength was? He never lied, he spoke absolutely calmly, rationally.

One more thing. They say: Hemingway, you need fewer words, a short telegraphic style, short phrases. Compared to Viktor Mohylny, Hemingway is a windbag. In Mohylny’s work, there is not a single extra word, not a single extra line, not a single extra letter. And when he speaks, and when he writes. You see what short forms his poetry has now been poured into. But more is said in these poems than in any of those long-winded, graphomaniacal, pseudo-patriotic epics that we often see. They have everything: that the communists are bad, etc.—we see that anyway. But we read one of his small poems—and it becomes ours. And you know why this is useful? Someone explains to you at length that two times two is four, and you get bored. But when Mohylny says it—there seems to be no political content, no KGB agent, no investigator could find anything seditious there, but it enters a person, it makes the person understand the situation themselves. He teaches people to think, and in this, he was very dangerous to that regime. Perhaps even to the current one, because people who think are very dangerous to a paper-pushing bureaucrat.

Oles Shevchenko: In the sixties and seventies, the people who gathered here today and those who could not be with us—almost every family was an island of Ukrainian independence. But you could count them on the fingers of two hands, at least as far as we knew each other in Kyiv. When I came to Kyiv from the village to study, I felt lost. I felt that a Ukrainian was a stranger here, in the capital of Ukraine he was a stranger, he was humiliated here, a disdain for everything Ukrainian, and especially for the peasantry, was cultivated here. For three years, I was somewhat lost, and I couldn't transform myself, and there was no place here for someone like me. And only when I found myself on that island of independence, where the Mohylny family lived, did I feel: this is the ground where one can land and where one can become oneself and grow. And there were many, many people like me in that family, in that house. We drew from that energy, from that mind, from the courage, from the unvanquished spirit. He loved everyone, supported everyone, helped everyone—our Viktor, my kume, by the way. I had the honor of baptizing the younger Mohylny, Attila, also a poet. Of course, he couldn't read all his poems today, but in them, he mentioned Mykola Plakhotniuk, who was in distant lands. People like that were held in Russian concentration camps and psychiatric hospitals, so Viktor wrote about such people in his poems, in particular about the gentle Mykola Plakhotniuk. He would say: "I will put a triangular dot at the end of my life." With his entire civic life and poetic work, he indeed put his bayonet into the history of Ukrainian life, his triangular dot. And of course, he has not said everything yet, because it is not yet the end of his life.

I will end my short speech with this episode. When they seized me at Hospital No. 3 in Kyiv (March 31, 1980. —V.O.)—a KGB lieutenant colonel arrested me and brought me home, they searched the place all day from ten in the morning until midnight—and they found Mohylny's poem "I Was Scared" on me. The poem greatly interested them; they immediately put it in a separate folder. It was clear: this was material not just for Shevchenko, but for Mohylny as well. And when they interrogated me—they held me there for 14 months, half here in Kyiv, half in Lviv, the case was connected with the publication of the *Ukrayinskyi Visnyk*, in which my dear friend and colleague, also a journalist, Vitaliy Shevchenko, and I were involved—they wanted to twist it so that Viktor Mohylny would also be prosecuted for this poem. They interrogated me: Viktor Mohylny distributed his poem. And that's Article 62, "anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda," for distributing anti-Soviet materials. "Viktor Mohylny distributed this poem among you, do you confirm this?" I say: "No, I do not confirm it, he did not distribute it." "Then how did you get it?" I say: "I stole it." "Well, how did you steal it, where did you steal it?" "Well," I say, "at their house. I came over, and Viktor Mohylny wasn't home yet." "And who was there?" "Well, his wife was there." "Ah, so his wife distributed the poem among you." "No," I say, "she was doing laundry in the bathroom and said I could sit and read something. I read this poem, which was lying on the table, it interested me, I put it in my pocket and thus stole it." And that's how I shielded Mohylny. But they still dragged him in quite a bit. If that poem had stayed in my pocket, because it's quite large, I would ask you, kume Viktor: maybe you could read it?

At that time, we drew strength, hope, and faith in the future from Viktor Mohylny, we went to Antonenko-Davydovych together and saw the same strength and power, unvanquished spirit there, together with Yurko Murashov and many, many other friends, with the disappeared Hryts Tymenkom. By the way, Hryts Tymenko disappeared after Dziuba's work "Internationalism or Russification?" appeared. I know that he reproduced and distributed it. And it was at this very time that he disappeared, and no one knows where he went. I am personally convinced that the disappearance and death of Hryts Tymenko, a talented young Ukrainian poet, was the work of the KGB. He lived for some time at Viktor's. Thank you.

Y. Murashov: I want to tell one episode that may be awkward for Viktor himself or for Mr. Plakhotniuk to recount, but it connects them. The fact is that in the book "Russification of Ukraine" (Russification of Ukraine. A popular science collection. K.: Publication of the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America. — 1992. — pp. 346-347) it is written that on May 22, 1967, four men were seized near the monument to Taras Shevchenko. Some sources say four, others five. Among them was Viktor Mohylny. It was then that Mr. Mykola took charge of the people who had gathered, and they went to the building of the Party Central Committee and secured the release of these four or five heroes, among whom was Viktor Mohylny. And by the way, it was at this rally that the now famous word, which later scared everyone, the word "hanba" (shame), was first uttered. When they started grabbing people, the word "hanba" sounded like a cannon shot. It was later revived at modern rallies. And all those people saying: "Oh, there they go again, they only know how to shout ‘hanba!’." Because it made their knees tremble.

And I also want to say that Viktor didn't just write poems. Pay attention to how he works with language, how he works with words. I remember him refusing to speak to a person just because they called him "Viktor"—"The Ukrainian language has a vocative case." I never had a chance to hear him speak Russian. It was under his influence that I traveled through the entire Caucasus speaking Ukrainian. I managed to do it. It was on such examples, on the examples of the Sixtiers, that the cohort grew which then continued to hammer away at that regime in the eighties, in the nineties. He did not take up a machine gun, he did not study weaponry, he simply wrote poems and was simply a Ukrainian...

M. Plakhotniuk: I'll add to this "hanba." There were the only correspondents from Germany there. They didn't understand what hanba was and started bustling about, running around and asking: "Was ist ‘hanba’?", "Was ist ‘hanba’?" (Laughter).

V.V. Ovsienko: That was May 22, 1967.

Vitaliy Shevchenko: I'll add to Mr. Oles Shevchenko’s story that they brought Viktor Mohylny to our trial in Lviv. On trial were Stepan Khmara, Oles Shevchenko, and I. This was the end of 1980. The aforementioned poem was in Oles Shevchenko's indictment. They call Viktor Mohylny as a witness. Of course, the judge immediately qualifies the poem as anti-Soviet, nationalistic, ideologically flawed, and so on. Viktor, absolutely fearlessly: "What’s anti-Soviet about it, what’s nationalistic about it? Let's look at every line, I'm ready to discuss it." His testimony was the bravest among all those from eastern Ukraine who were summoned to the trial. On the same level were people from Chervonohrad, I believe, simple workers. They proved that the witness—the secretary of the mine’s party organization, who supposedly heard Stepan Khmara’s anti-Soviet statements in a billiard hall—they proved that the party secretary didn't even know how to get into that hall. There was some complicated entrance that he didn't know how to navigate. And they proved that it was a fabrication. So the judge’s only argument was that the party organization secretary himself had said it and he couldn't have been lying. So, I wanted to say that Viktor also spoke with the same level of courage. This is a person who could never falter, and I think that maybe even the KGB bypassed him because he would have been too much trouble; he won't yield even half a centimeter.

Y. Murashov: I want to add one more thing. At that time, I was working in a museum. A living legend came to see me—Vsevolod Hantsov himself, a defendant in the SVU case, came to me. He came to donate a gold coin to the Museum of Historical Treasures, which had been accidentally preserved in his family. And I was talking to this living legend. Of course, I immediately informed Viktor about it and gave him Hantsov's home address, which was written in the acceptance certificate for this coin. And Viktor Mohylny writes a letter to Hantsov, asking not a political question, but a philological one. Something very intelligent, scientific, something about sibilants (Now: consonants. —V.O.), I don't remember exactly anymore. You understand, a person who had been under surveillance all the time, with whom everyone was afraid to talk, who had already been written off as a philologist, suddenly receives a letter where Viktor Mohylny asks him for a consultation on a purely scientific matter. I think that was a huge support for Hantsov; he replied shortly after, it was a substantial, long letter. Viktor read it to us. Maybe it has been preserved. But Viktor survived a search, and I don't know if this letter survived. It wasn't just curiosity; it was an act of courage, of supporting a person. I would like Mr. Viktor to read "We Were Scared" after all.

V.M. Mohylny: By the way, they were talking about this "triangular dot" here. Plakhotniuk said that if he had a display case, he would stick me in there as a live exhibit. (Laughter). It wasn't just you, Oles, who felt out of place in Kyiv—I, at the age of 15, also dreamed of meeting a peer (15-year-olds have their own secrets that you can’t discuss with a grandfather or an aunt, they have their own vision of the world, they’re dynamic lads). I dreamed of meeting a peer with whom I could converse in Ukrainian in this very capital.

We were all moving towards each other. Since I had an apartment in Kyiv, and everyone else lived somewhere in dormitories, they were drawn to me. But we were all creating this critical mass together, which could then create something. Because a single person, by themselves—what can they do? Everyone here says: a little poem, a little poem, but it’s long, this "Autobiography," and I get mixed up, I need to get a piece of paper. [Reads "Autobiography." See the publication "The Story of One Poem" in the newspaper "Chas" January 29 – February 4, 1998].

This was December 1976. Well, and then I wrote little poems for a bit, until about 1978, and then I stopped. But when my little dark-haired grandson appeared, I got fired up: it turns out, children need Ukraine. I was working at "Lenkuznia," I worked there for 25 years, I had no language problem there, because the workers are yesterday's peasants, the language there is a bit cluttered, but what syntax, if you listen—it’s a witty language, Ukrainians are a noble nation. There was no problem there. But then this little one. And my other half got a startle: let's make up for the sins of our youth, she hadn't taught the children her language, so we must experiment on this grandson. My God! And in Hungarian, they have words with 150 letters, a single word! And the sounds! So she starts buying books. And back then in the "Druzhba" bookstore, there was something in foreign languages, they cost pennies. I looked: the Hungarians were making such little books back then, like Malkovych is making now—a pleasure to hold in your hands. And then it takes about two weeks for a child to tear it to shreds. And it's only a five-minute read. [Long, unintelligible phrase about a book of children's poems]. Larysa Kolos worked at the "Veselka" publishing house. She didn't like my pseudonym, Vit Vitko. She wanted Viktor Vitko. Well, I say, that’s nonsense—Viktor Vitko. [Unintelligible].

Like in 1967 when they threw me in the bus—I know how to count to five. It seems to me that there were indeed four of us. I had a diary. Well, what kind of diary? I'm a person who isn't very punctual, as they say, but I could write something down there. I remember that one of us was Jewish, one was young, and the other was an older man compared to me, a gray-haired man already. So I remembered that my diary was confiscated in 1980—all manuscripts, the diary, some correspondence. I went to the SBU and said, here's the deal, give me back my file.

When they called me in for interrogations… Well, what’s my habit: no matter what a person is, you still try to see signs of a human being in them. Because I myself was a worker, an electrician, though I have no special talent for it, but you have to earn a living somehow. [Unintelligible]. So what did they tell me then? Sometimes, you’d get wound up, ask something, and they would stand there, gracefully leaning on their truncheon: "Viktor Mykolovych, excuse me, but in this building, we are the ones who ask the questions." Well, and now I've started demanding things from them. It turns out that when the ground started burning under their feet in 1989, what did they do? These files—you can imagine how many there were. Here's mine: "DON 3725-P". DON means "Delo operativnogo nablyudeniya" (Case of Operational Surveillance), 3725 is the number, P is for "profilaktirovannoye litso" (a prophylactically treated person). By my calculations, they started it somewhere in the mid-sixties. Even if it was in the eighties, that's still 3700—which means after me there were, by my count, about seven thousand more. That's just in Kyiv, seven thousand. Because mine is 3725, and the selection list is 51. And there were hundreds of those selection lists. So you can imagine how many of these files there were. So they started destroying them—because they contained intelligence reports. What's interesting? "Selection list 51 of archival cases and prophylactic materials subject to destruction upon expiration of the archival storage period"—there's no contradiction here, but under this list is a signature: Head of the Tenth Department of the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR, Lieutenant Colonel Pshennikov. And here, in the certificate they provided, it also says: Head of the State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine O.N. Pshennikov. Now a Colonel.

And now this General Prystaiko, a friend of Ukrainian writers, who published a book with Shapoval about the SVU trial… (Prystaiko V.I., Shapoval Yu.I. *The Case of the "Union for the Liberation of Ukraine": Unknown Documents and Facts*. Scholarly-documentary publication. K.: Intel, 1995. – 448 pp. – V.O.). Seventy-one, Lieutenant Prystaiko—an investigator in the case of Nina Strokata in Odesa.

V.V. Ovsienko: Prystaiko is a friend of mine too…

V.M. Mohylny: Well, a friend is a friend. These are some friends... (Laughter). What did I demand from them? They have an interesting thing there—a protocol of the examination of seized items. What does the search protocol say? A green notebook, beginning with such-and-such a word, and ending with such... But in the examination protocol, they quote certain passages from the diary—so you can already figure out that it is a diary, and there are juicy quotes there, comments, names are mentioned. And it doesn't matter that my lawyer was Ivan Makar, Ivan, and my consultant was a friend of mine. For conspiratorial reasons, I won’t name him. They put the squeeze on that judge and brought out their selection list; I took it for the cover of this samvydav book "Csokolivka, csokolj meg!" And the younger generation did the artistic design for me.

What am I getting at? I wanted to pressure them from another side, I wanted to use Radio Liberty, Voice of America, I have buddies everywhere there, but you have to seek truth in your own house. Ukrainian Radio told pretty much the same story I just told you.

And when I needed to churn out some children's poems, I struggled and struggled, but it just wasn't working. So I took a little book by Edward Lear. It was published here in a translation by Krylovsky in 1980 and 1988, two editions. It's popular in England. But here they consider children to be dim-witted—children's magazines don't print these poems. But it’s not the children who are dim-witted… But to hell with them. Well, not dim-witted—overworked, saddened. The form is the limerick. It's an Irish city—Limerick. Like our kolomyikas—they come from Kolomyia. A kolomyika is a very powerful thing. But limericks have a trick where you repeat the word from the first line in the fifth. I was talking with Mokrovodsky, that we have analogs of the limerick. For them, the limerick or limericks are a literary fact, that is, they entered high literature, but our kolomyika remained at the level of folklore, and the collective-farm kolomyikas did not enter literature. It’s such junk, as the Russians say. I decided to play around with these limericks. Approximately, because I feel rhythm and melody like a color-blind person sees color, I can’t sustain it, because a classic limerick is an anapest. And what is that? Well, these things just don't sound right for me. So I twisted them. It was a favorable coincidence. They can be read.

M. Plakhotniuk: Let's have a musical break, because people are tired, and then we'll read, okay?

Ruslan Kozenko: I am Ruslan Kozenko. Although, you might hear not Ruslan, but Rusayim more often. Now I'll sing the song "Oh, a Young Cossack Rode to Muscovy." A famous song, in our arrangement. [A song plays].

V.M. Mohylny: [Reads limericks, very quietly and unclearly. Here are some of the ones he read, scanned from the book: Csokolivka, csokolj meg!, or The Bitten Apple: Chimeras. – Stolytsia, 1999. – 43 pp.].

Тамань (С. 21)

Та чи й тільки того на Тамані,

Що сльоза п’яні очі туманить?

Чи тополя безкрила?..

Чи не та ж Україна

На цій самій вчорашній Тамані?..

Зелений Клин (С.18)

Далеченько зелений Клин…

Та своє воно – як не кинь!

І душа ж не чужа

Пестить вістря ножа –

Прикипів до серця той Клин!

Безсовісний (С. 16)

Може, хтось і має совість –

я свою спровадив псові.

Ще як вчився в третім класі –

грошики носив до каси.

Щоб згубила каса совість.

Лемківщина (С. 8)

Чи ж ми дикого меду вощина –

Щоб у приймах була Лемківщина?

Поміж ляхів і товтів –