From the declassified archives of the special services, former political prisoners learned about the “snitches” in their circle, the bugging of their apartments, and the KGB's operational methods.

These archives still hold many secrets. Fortunately, some of them are becoming public knowledge. So today, former dissidents can look into folders containing once top-secret documents of the Ukrainian SSR's Committee for State Security and learn many interesting things about themselves and others.

So, what secrets did the special services' archives hold? Ekspres asked the subjects of the “BLOK” case—Ukrainian dissidents of the 1960s–1980s Vasyl Ovsiienko, Valentyn Moroz, and Bohdan Horyn—about this.

The Secretary Was an Agent

—How did it happen that you gained access to the holy of holies of the Soviet special services?

V. Ovsiienko: —Back on February 17, a group of us, former political prisoners, were invited by the then-director of the SBU archive, Volodymyr Viatrovych. We were invited to review the archives and express our thoughts on what to do with them next. Everyone agreed with Valentyna Chornovil (Viacheslav Maksymovych’s sister) that the archival documents from that time contain so many lies about each dissident that they can only be published with appropriate commentary. Although the information I read about myself was quite objective. By the way, I found interesting details about myself in my file that I never knew…

—Such as?

—For example, I only now learned that one of our trusted associates—a typist who in the summer of 1972 typed Vasyl Lisovyi’s “Open Letter to the Members of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine” in defense of the arrested Sixtiers—was a KGB informant.

When Yevhen Proniuk and Lisovyi were arrested for this letter, they refused to name the typist for a very long time. I also didn't name her after my arrest until her name appeared in the case file. But it turns out that on the very day I brought this “Letter” to the typist, Raia (that is, June 26, 1972), she reported it to the KGB, and the KGB officers decided to “not obstruct the creation of the document in order to catch them red-handed.” This Raia, whom we trusted so much, appears in the file as “Agent Valia”!

In general, a lot of lies circulate about this “BLOK” case. For instance, that people like Kendzior or Yavorivskyi had underground pseudonyms in the KGB and worked under them. That's not true; it's the other way around. For operational purposes, the KGB would assign a pseudonym to a target, and the person wouldn't even know they were being called that.

Where, When, and with Whom

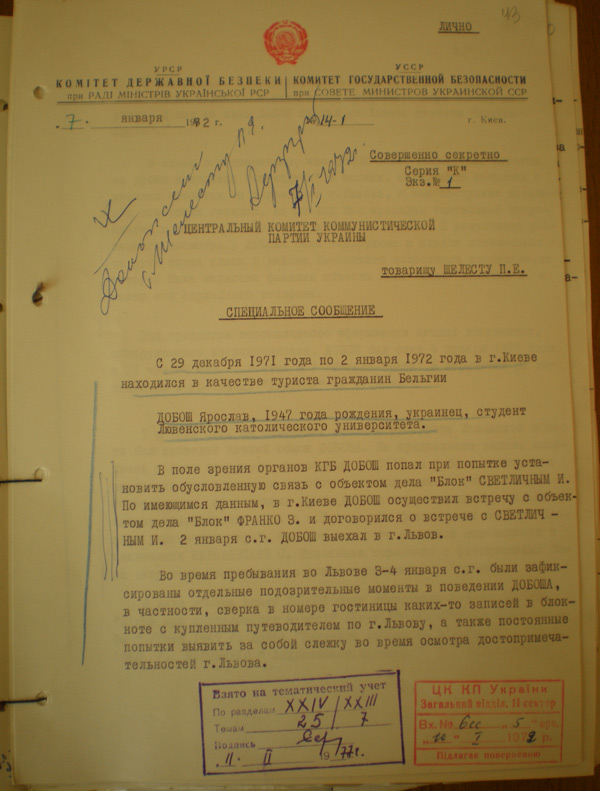

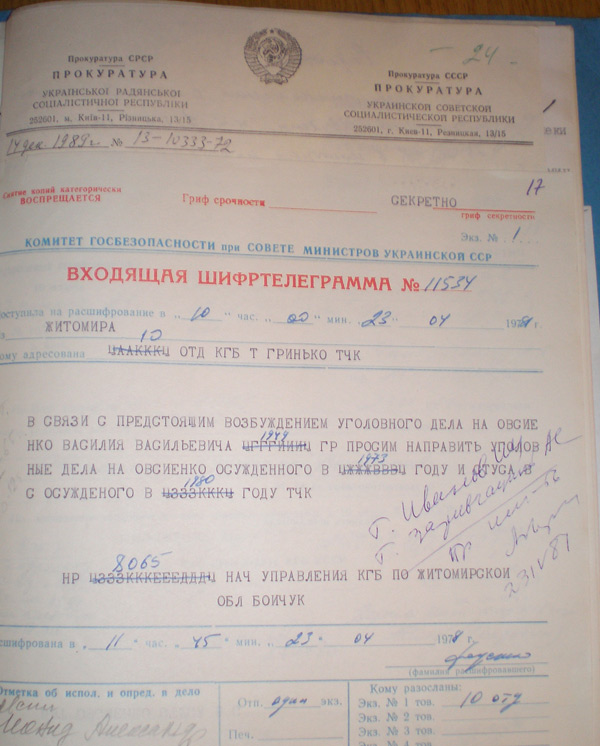

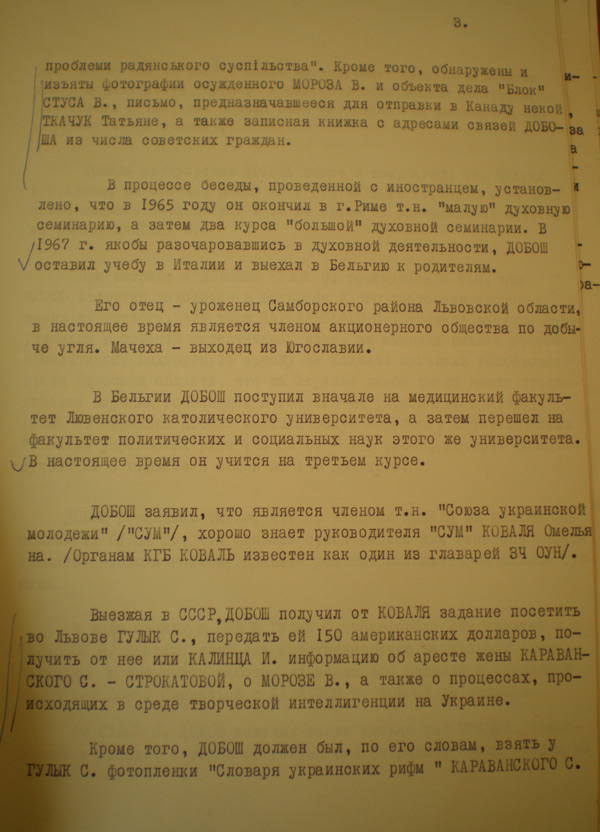

—In the documents from the case of Yaroslav Dobosh (a Belgian Ukrainian who smuggled *samvydav* literature abroad), it’s described in great detail how the KGB agents surveilled him. The surveillance was even conducted in his hotel room, apparently with a hidden camera. Were there any instances of such “technological” surveillance in your case?

B. Horyn: —When I was reviewing KGB reports from the late 1980s and early 1990s, I was shocked—they described in such detail, day by day, where, when, and with whom I met and where I went. Day after day. There is similarly detailed information about my brother Mykhailo, Ihor and Iryna Kalynets, Stepan Khmara, and Viacheslav Chornovil.

As for technology, in the SBU archive, I randomly opened one of the volumes and came across a KGB message: “With the help of a listening device installed in the Kalynets’ apartment, we were able to find out such and such.” Of course, it’s unknown where and how they installed these devices.

V. Ovsiienko: —The “BLOK” case features Yevhen Kontsevych from Zhytomyr. He has been paralyzed since 1952. In 1965, when he was 30, many friends from Kyiv came to visit him—Chornovil, the Svitlychnyis, Sverstiuk. And the KGB planted a bug. Yevhen discovered the device during the night and threw it in the trash.

The next day, they searched his place but didn't find the bug, even though it was in a trash pail. A wire was even sticking out. After that, his works were no longer published. During the search, one KGB agent said, “That lying corpse—if he got up, he wouldn't be walking. He'd be serving time.”

I passed some documents I had photographed in the SBU archive to my colleague, Oles Shevchenko. They were about how in 1976, he, along with Vitaliy Shevchenko and Stepan Khmara, prepared the next issue of the journal *Ukrainskyi Visnyk* (Ukrainian Herald). They typed it, reprinted it onto microfilm, and gave it to a person in Lviv who was supposed to pass the film abroad. But KGB agents secretly searched this man's place, found the film, made a copy of it—deliberately of poor quality, with a blurred image—and put it back where they found it.

And this blurred microfilm, from which nothing could be read, was sent abroad. The KGB agents then reported “upstairs” that the *Ukrainian Herald* had been neutralized and was not published abroad. And we, the participants in those events, only learned the real reason for its non-publication now, a quarter of a century later.

V. Moroz: —There was also ordinary surveillance. At that time, we lived in an atmosphere of constant watch. But you get used to it. When a spy follows you on the street every time, endlessly walking and noting everyone you meet or exchange a word with, you get used to it whether you want to or not.

“Snitches”

—Did reviewing the archive file change your attitude toward the people who testified against you during interrogations?

V. Ovsiienko: —Maybe there were “ideological” snitches. I know one thing: none of my friends could have informed on me voluntarily. They were put under pressure, forced into certain circumstances, made dependent on whether they would continue their studies or not, have a job or not. And some people gave in, others held firm. But I blame myself more than them…

V. Moroz: —It all depended on a person's fortitude. Someone would stand on principle, like Stus—die, but not give in. And another would write a review of your work, accusing you of all sins. In my case, there was an “expert,” Khvostin, who wrote in his conclusion that my articles contained “extreme anti-communism,” although there wasn't a single word about communism in them. And that was enough to convict me.

When I worked at a department of the Polygraphic Institute, there was such a guy working there. He did the expert analysis of Ihor and Iryna Kalynets's works. And those bastards are still working.

Now, in the case of Ivan Dziuba, the KGB used a method that all the world's special services have used since the time of King Hammurabi. When a person is put in prison, their character hardens, they become focused. But when they are released, the person relaxes psychologically. That's how they got Dziuba. He was first arrested, then released, and later arrested again. And he couldn't take it. In my article from that time, “Amidst the Snows,” I wrote that of all people, Dziuba, who was a symbol of the Ukrainian resistance, had to hold out to the end, but he wrote a letter of repentance. Dziuba is still angry at me for those words.

—And were you personally forced to repent?

V. Moroz: —That kind of pressure was constant. They used various methods. For example, they put me in a so-called “press-cell” with three “criminals.” They are usually psychopaths; being with them is daily torture. And I was given an ultimatum: either sign a letter confessing your guilt and repenting, or you will die in this hell.

I endured it. But some people repented. For example, there was a poet, Mykola Kholodnyi. A wonderful poet, without exaggeration. But he broke immediately and wrote a public letter condemning all his human rights defender friends. But there were few capitulators among Ukrainians, no matter what they say.

—Do those archives contain the names of the informers who “snitched” on you?

V. Moroz: —Informers, as a rule, are not named in the documents. No police system, especially not the Soviet one, would ever publicize the names of its agents. They are its greatest treasure. Personally, I knew a few “snitches” who worked for the special services. For example, among the political prisoners, there was one nicknamed Baltiyskyi.

Or a certain Kichera (that's also a pseudonym), whose task after the war was to pose as an underground fighter to uncover bunkers with UPA members and turn them over to the Soviets. In Vladimir Prison, we had a Captain Donnikov, and that agent Kichera collaborated with him.

V. Ovsiienko: —That's just it, there are no names of informers. The documents we were given to review were written based on denunciations, operational intelligence, and interrogations. They were written in Russian with quotes in Ukrainian (it's immediately clear who was in power) and signed by KGB heads. First by Nikitchenko, and then by Fedorchuk. Moreover, the names of informers are missing not only in my case, but in general. The documents use the term “source” (*istochnik*). Sometimes, the informers' pseudonyms are used. As a rule, these are memoranda that KGB agents wrote to the Central Committee of the Communist Party, and more rarely, to other institutions.

B. Horyn: —As the director of the SBU archive told us in that conversation, in special services jargon, denunciations are called “operational data.” And no more than two percent of this “operational data” from the Soviet period has been preserved. The rest was destroyed when General Holushko headed the Ukrainian KGB. After Ukraine declared independence, he moved to Moscow, taking a huge portion of the operational materials with him.

I think that these materials actually exist somewhere. This belief is bolstered by the fact that some of these supposedly destroyed materials are occasionally published by some of our domestic media outlets. After all, it is known that archives do not burn.

Ekspres Reference:

The Ukrainian SSR KGB special operation against Ukrainian dissidents, codenamed “BLOK,” began on June 28, 1971, with a decree from the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee on combating *samvydav*. The case lasted fifteen years, with its last documents dated 1986.

The goal of this operation was to counteract the Ukrainian national movement. The Dobosh case (he was arrested on January 4, 1972, in Chop) and the mass arrests of 1972 gave it special impetus.