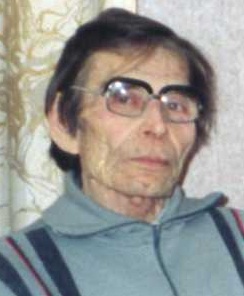

An Interview with Semen Ivanovych BUTIN

V. V. Ovsienko: February 22, 2001, the city of Kherson. Semen Ivanovych Butin, 75 Komkov Street, apartment 115, postal code 73011, telephone 0552-23-86-98. The interview is being conducted by Vasyl Ovsienko.

S. I. Butin: I am Semyon Ivanovich Butin, born on October 17, 1927, in the village of Tsagan-Oluy, Borzinsky District, Chita Oblast. My father, Ivan Semyonovich Butin, worked as the director of the state farm (sovkhoz) named after the NKVD until 1938. And on July 5, 1938, by the authority of that very name, he was arrested and in total served ten years in a Soviet concentration camp.

V. O.: And what was he accused of?

S. B.: It’s a strange turn of events, but to this day I don’t know what he was accused of, because I was eleven years old at the time and was not privy to all these repressive events. But I do know that in Chita and Chita Oblast alone, twenty-five thousand political prisoners like my father were rounded up that year.

And my father was born in 1896. His parents, his father, Semyon Ignatievich, was classified as a kulak and exiled to the town of Tulun in Irkutsk Oblast as a kulak.

My father's mother, Lyubov Alekseyevna, was also repressed along with her whole family and her husband—that is, my grandfather—to this town of Tulun.

I was 11 years old then. In my collection of poems, I made a reference to page 64, so I would rather not repeat myself. But then again, it’s better to say it into the dictaphone than to have someone look for my little papers and search for that 64th page. Or the 13th.

I was 11 at the time, and I remembered my father’s arrest for the rest of my life. I finished school. In 1944, I was drafted into the army and served until 1948. Back then you didn’t serve for two years, naturally, but for as long as the Motherland required. So I served for four years. After the army, I entered the Khabarovsk Institute of Culture. After graduating from the Institute of Culture, I was appointed—or rather, not appointed, but invited as a musician to work in an ensemble. Our ensemble was sent on tour to the city of Magadan, to Kolyma. We toured in Kolyma for two and a half months.

When everyone was about to leave to go back to Khabarovsk, to the Khabarovsk Philharmonic, I met Valentin Mamontov in Magadan—I think he was an editor—who worked at the editorial office of the newspaper *Magadanskaya Pravda*. I don't remember what his job was... I got to know him, and he invited me to the dormitory where he lived. And in that dormitory, we held, if I may put it this way, several conversations on free topics.

One of the topics was about communists and communism. That’s how I got hooked. Later I thought that he might be a KGB agent. I'll tell you why. Before inviting me to the Arktika restaurant, he said that supposedly there were some people he knew in Odesa who were engaged in anti-Soviet propaganda and held sentiments similar to mine. And he said: “Write me something anti-Soviet”—well, he didn’t say “anti-Soviet” then—“write me something for Odesa in verse and curse Khrushchev.” And Khrushchev was already in power then.

Which is what I did. But I did it while drunk. We had a good drink then. We went back to the Arktika restaurant. In the Arktika restaurant, he invited me to a table next to the stage where the musicians were. Since I already knew the musicians (I was staying at the Arktika hotel, and the restaurant was also called Arktika), it was natural for me, a musician, to find a common language with them. And I demonstrated a few things on my musical instrument. By then I had mastered the accordion, the piano, the bass guitar, and something else, I don't remember anymore. So, we sat down at a table next to the stage. On the table, there was ice cream, an unopened bottle of “Champagne,” a decanter of vodka, and apples in a vase. The thing is, in Kolyma, these apples, and fruits and vegetables in general, were always a delicacy. That's quite natural: everything was imported.

Mamontov and I were sitting and talking. But then I noticed he was in a kind of anxious mood, that he kept looking around and seemed thoughtful, with a guilty look on his face. It was only later that I found out why he was in such a state.

At that time, it was customary to treat the musicians and give them money. Among those on stage were some who liked a drink. The leader of the ensemble was the oldest one in the group. I gave him a sign, and he told me to take it to the buffet. The buffet was in the hallway, as is usual in restaurants with a kitchen and service counter. I carried this small glass of vodka across the hall to the buffet so that the ensemble leader could come and drink it there.

As I was walking past a nearby table, a short, red-haired man got up and demonstratively knocked the glass out of my hands. And at that same moment, a man in civilian clothes came up from the next table—I later found out he was Captain Kozlov—and he took me to the administrator's office of the same restaurant. He immediately reached into the pocket of my jacket, precisely the pocket where the letter was. Although, of course, I have more than one pocket in my jacket. Maybe it was a coincidence, I don’t know, but that’s how I understood it. When he pulled the letter addressed to Odesa, with abusive words against Khrushchev, out of my jacket...—I can't even talk about it calmly now, because this scene is still mentally before my eyes.

I immediately realized then that it was Mamontov's doing. And the man who knocked the glass over turned out to be a Lithuanian. I don't know him, not his name or anything. Because, naturally, he disappeared like a ghost. He wouldn’t show up, not even as a witness: he knocked over the glass, that was it, and he disappeared. And that was all.

A few minutes later, I was taken by car to the KGB prison in Magadan. And that was it. I got stuck there. The only piece of evidence against me was that abusive letter. But abusive in what sense? Not in the sense of swearing, but in the sense of criticism, and not so much of Khrushchev's personality, as the issue was the system we lived in, and so on. But Khrushchev was mentioned personally there. In that letter, I called the whole communist plague a gang.

Thus, I ended up in a KGB prison. Two or three months passed before the trial. They weren’t in a hurry back then. And—five years. The trial—and five years in a corrective labor camp.

V.O.: Do you remember the date of your arrest and the date of the trial?

S.B.: The term started on October 13, 1958. By the verdict of the Magadan Oblast Court on December 29–30, 1958, under Article 58-10, part 1 of the RSFSR Criminal Code, I was sentenced to five years of imprisonment.

V.O.: And where were you held, what were the conditions?

S.B.: I was lucky in the sense that I didn’t have to serve my sentence in Kolyma. The fact is that in those days, there were massive, so to speak, massive evacuations of all political prisoners from Kolyma. Everyone was sent to the mainland, to Taishetlag. The political camps in Kolyma were liquidated. I was the only prisoner in the jail; there was no one else. I alone was flown to a transit prison in Nakhodka, and there I was joined with other prisoners and taken to Taishetlag. In Irkutsk Oblast, I think. I served my sentence in Taishetlag. I don’t remember the names of the people I was with anymore. Everything is indicated there, in my documents.

From there, from Taishetlag, all the prisoners were relocated to the Mordovian ASSR. Including me.

V.O.: Sometime in 1959, I believe?

S.B.: I'm not sure about the dates. But on the way, those of us who had paper and pencils in the train we were taking to Mordovia, for the whole journey, at all stations, large and small, we wrote and threw anti-Soviet leaflets out through the bars. I remember this because it was summer: it was warm, the windows were not closed. At every station, at every small stop, at every train station—we threw them out through the window bars of the car.

When we arrived in Mordovia, not all citizens of the USSR turned out to be honest. Some handed these documents over to those who should and should not have them. They should have, of course, been taken to the local KGB offices at all the stations and stops. Apparently, they ended up with the KGB.

V.O.: Which camp were you in in Mordovia?

S.B.: It's hard for me to remember right now, I need to look it up. I remember ZhKh-385; I was in the tenth camp unit, then in the nineteenth.

V.O.: That's the settlement of Lesnoy. I was there in the seventies.

S.B.: Oh, that's interesting. The settlement of Yavas… Vikhorevka—that was in Taishetlag, I just remembered. After we had scattered anti-Soviet leaflets all the way to Mordovia, we found people in the camps who were critical of the existing Soviet system. We decided to organize to fight the Soviet system. How? Like-minded people like me found a common language and decided to act in an organized manner against the existing system in the USSR. Our union was called the Democratic Union—DS. Like Valeriya Novodvorskaya’s.

V.O.: But she came later…

S.B.: Yes, she wasn't there at all. She had nothing to do with what I just said. I remembered her as an example. The Union’s tasks included the dissemination not of deliberately false information, as the KGB guys accused us of, but of deliberately not-false information. The UDS—the United Democratic Union—had as its goal the overthrow of the state system, but not by violent means (we had no such opportunity: we were prisoners and unarmed), but by spreading our ideas among the population, among free citizens, not just prisoners. Well, among prisoners, that goes without saying.

So, our group worked on prisoners in an anti-Soviet spirit; we looked for accomplices. We existed in the conditions of a concentration camp, where there were searches and all sorts of actions by the wardens and the administration. Despite this, we existed for more than a year until, due to the fault of one of our accomplices, Yevgeny Maslov, the Charter and Program of the UDS—our party—were discovered under his pillow during a so-called *shmon*, a search during the lunch break.

That’s where it all started. After they found the Program and Charter of our organization under Maslov’s pillow, the chairman of our UDS, Chingiz Jafarov, an Azerbaijani by nationality who had arrived with us from Taishetlag; Vladimir Tunyov; and Semyon Butin, your humble servant—we decided to take the organization underground for a while. But that didn't save us from a second arrest. Why? Because when Zhenya Maslov was arrested, they naturally started interrogating him: where did all this stuff come from? Because they found it under his pillow. He said it wasn't his, that he had nothing to do with the organization. He said it was either planted on him by the guards or by one of the prisoners. Thus, Maslov had nothing to do with the UDS, although he was our colleague. Out of the entire UDS organization, only three of us were tried. The rest served as witnesses or were not prosecuted at all. They added another two or three years to my sentence.

V.O.: What article?

S.B.: Article 58 didn't exist at that time; there was already Article 70 and 72 of the RSFSR Criminal Code.

V.O.: Article 70 is for anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, and what's 72? Creation of an organization, maybe?

S.B.: The thing is, I knew Article 58 well... Article 72 was for organization, I think.

V.O.: And how much did you get?

S.B.: Two years. Or three. One moment. I served seven years in total, so that means five and two. (According to the verdict of the Supreme Court of the Mordovian ASSR from September 13–18, 1961, Semen Butin received 3 years of imprisonment with one year from the previous sentence added. The final sentence was 4 years, beginning on September 18, 1961. In total, he served 7 years and was released on May 4, 1965.—V.O.)

V.O.: And what happened after the trial? Were you kept in the same zone or transferred somewhere else?

S.B.: They scattered us among three zones. I think that's where I met Yura Litvin.

V.O.: You were in the tenth, and from the tenth, you were scattered to other places...

S.B.: Yes, then I ended up either in the nineteenth, or... Well, that's not the main point. Is there anything about Taishet there?

V.O.: Here it only says about the tenth camp unit, that the organization was created there.

S.B.: Where did we leave off?

V.O.: On the fact that you received two years and continued to serve them in Mordovia.

S.B.: So, they added two years for the anti-Soviet organization, in which I held the position of head of security for the UDS. Tunyov handled coordination and political matters. I refer you to the indictment, which I have with me here and which I am giving to Vasyl Vasylyovych Ovsienko. Everything will be clear from the indictment: what, where, when.

I was released after serving my sentence in 1965. I don't remember the month, I think it was in the summer of 1965 (May 4, 1965.—V.O.). I served seven years in total. From there I returned home to the city of Tselinograd, where I started working in my profession, that is, I worked as a musician in restaurants. I directed amateur art activities in the clubs of Tselinograd. I lived in Tselinograd for twelve years.

V.O.: And when did you come here, to Kherson?

S.B.: In 1978. Here I continued my work, but not in an anti-Soviet direction, because the Soviet Union still existed. I worked here as a musician at weddings in Kherson, around Kherson Oblast. I had a special wedding ensemble of musicians. That's how we made extra money. Well, what else can I tell you “about Sakhalin”?

V.O.: And did you face any oppression due to your previous conviction? Did the KGB have any complaints against you? Were you banned from working, from your profession?

S.B.: There was oppression. But it wasn't so noticeable: they didn’t grab me by the scruff of the neck, they didn’t put me in any police lockups, and so on. They didn’t even incriminate me in any drunken brawls or hooliganism. I'm not that type, for one thing. Secondly, I always felt I was being watched. Here, let me tell you a little episode. When we were living in Tselinograd (my father was still alive), we had a dacha outside the city. They used to give you six hundred square meters, if I'm not mistaken. But that was enough for us. One day, as I was crossing the bridge to the dacha, over the Ishim River (it was a suspension bridge, specially for the dacha owners, not a permanent one), I saw a man catching up to me. I remembered I had seen this man somewhere before. It was during the day. He caught up to me and tried to throw me over the railings. The railings there were made of wire; it's a suspension bridge, you walk on it, and it sways. And he wanted to throw me off. My legs saved me. He was hefty, with a big belly, strangely enough, though not a woman. At first, I had the impression that it was a pregnant woman, then I looked closer, and no, he had a man's face. And what do you do in such cases? Run, just run. How do you say it in Ukrainian—“тікать”?

V.O.: Yes.

S.B.: Exactly. What else can I remember about how they persecuted me? They wouldn't give me a job. Here's a small episode. It was so many years ago, but still under the Soviets. When I arrived, I didn't tell anyone that I was a former prisoner. I didn't show these certificates to anyone. I didn't tell anyone in Tselinograd after my release. I told no one. I mean, why would I go around saying I was a prisoner, asking people to either love me or hate me? Of course not.

But I always felt the Chekists’ breath on my neck. Always, I had my reasons for it. I worked as a musician in the restaurants “Ishim” and “Moskva” in Tselinograd. Now the city is called Astana—the capital of Kazakhstan. I felt the breath of this Soviet police-militia, the KGB. Because although I was released, I had not yet been rehabilitated. And there was always a “tail” on me. I don’t want to go into detail; there were too many of these incidents to recall them all. I’ve already told you about one, about the bridge.

There was another incident. When I left the “Moskva” restaurant after an evening's work (we worked, I think, from seven o'clock—the start of work—until twelve, until two in the morning). To get home, I asked a taxi driver—taxi drivers were always on duty near the restaurant—and he started to drive me. But it turned out he wasn't a taxi driver, strangely enough. Though he had the “taxi” sign. At two in the morning. He took me to the police station, or maybe to the KGB, I don't know. But in that direction. I jumped out of the car... It was winter, I remember it like it was yesterday. In the park near the Tselinnik Palace (the famous Palace of the Virgin Landers, which became world-famous, built under Khrushchev, its photos were all over the Soviet Union). There, in the garden of this Tselinnik Palace, I jumped out of the car: the door on the side where I was sitting wasn't closed. I jumped out and into a snowdrift. And how did I know I wasn't mistaken? The thing is, the car circled this garden several times: three or four times and maybe more, lighting up the garden with its headlights. But I climbed into a big snowdrift between the trees, or rather, the bushes—and his search for me was in vain. In the morning, I went to that spot and looked: indeed, cars had been waiting for me there. Well, okay. I’ve digressed a bit from the main topic.

V.O.: And when were you rehabilitated? Is there a rehabilitation document?

S.B.: Yes, I'll tell you about the rehabilitation now. The thing is, one certificate was sent from Mordovia stating that I was not subject to rehabilitation. Here... I have a suitcase here. I called it “Kompromat on the Communists.” There's a small note in there. A formal reply from the Mordovian KGB stating that I am not subject to rehabilitation. And then they rehabilitated me. When, God help my memory...

V.O.: And here there is a certificate of rehabilitation: “Procurator’s Office of the Mordovian ASSR, dated 09/13/1993.” “According to the RSFSR law ‘On the Rehabilitation of Victims of Political Repression’...”

S.B.: That's when they rehabilitated me themselves. Well, what's the difference, really: rehabilitated or not. What does it give me? Take my father, for instance. He served ten years in a Soviet prison somewhere in the North, in a concentration camp. But he was never rehabilitated, not even when he died. Because the Soviet Union still existed. After all, when was I rehabilitated? Is the year indicated there?

V.O.: 1993.

S.B.: 1993, that's when there were no more communists and Soviets. Forgive me, does it surprise you that I use such terminology? *Sovdepiya*, communist plague, and so on. Does it surprise you?

V.O.: It’s well-known terminology, and it’s correct.

S.B.: I “love” communism and the communists so much that I cannot express myself any other way. As an acquaintance of mine would say in my place, “vyrazhóvyvat’sya” [to express oneself].

V.O.: I read somewhere that you were imprisoned with Yuriy Litvin. Where was that?

S.B.: That’s what I'm saying, either in Taishet or in Mordovia.

V.O.: He was in Vikhorevka, and he was in Mordovia.

S.B.: Really? He was in Vikhorevka? One moment, I can't remember where. We had bunk beds in the barracks. Yura slept on the other side, the beds were on one side and the other. And Boris Vail was there. He was a former student from Leningrad. Boris Vail. They had some kind of anti-Soviet student organization. And this Boris Vail, by the way, taught me Esperanto. He had textbooks in Esperanto, and so he taught me. I was a good student, but then I was released, and Borya, I think, stayed there. And Litvin, I think, stayed there too. They were released after me. God, I don't know when.

V.O.: Litvin was released in the fall of 1965.

S.B.: I was released in the summer of 1965, or in the spring.

S.B.: It's a pity I got caught up in Tselinograd. After my release, I could have written to him and met him somewhere. But, of course, I didn't know his address, Yuriy Litvin's. And he didn't know mine. I know he only spoke Ukrainian.

V.O.: He wrote poetry in both Russian and Ukrainian.

S.B.: I don't remember that. But he did write poetry. He came up to me several times after work in the barracks, asking for words: “Well, what about this, how is this?” I have a couple of poems by Boris Vail here. Not by Yuriy Litvin, but by Boris Vail. Here they are.

V.O.: Did you know Viktoras Petkus too?

S.B.: I knew Viktoras Petkus. Did I tell you about how a Catholic priest baptized me in the banya?

V.O.: Ah! Yes, yes, please tell me.

S.B.: Račiūnas Pranas—although he was a priest, he had his own accordion. There was an amateur art group in the camp, even in the political one. Mostly, the musicians in the amateur group were from the Baltic states. But Račiūnas Pranas had his own accordion. He didn't participate in the camp's amateur activities. He had some nice sheet music in a retro style. And I wasn't baptized. We got to talking one day—he didn’t know Russian that well, this Pranas. I call him Pranas. Why? Frans. Frans is the Russian way. But in Lithuanian, it's Pranas Račiūnas. And so I tell him in the camp: “I want to be baptized. I am not baptized. And I don’t want to be baptized into the Orthodox faith, because I’m already thirty-two, for one thing. Secondly, I consider the Orthodox to be somehow... not quite right. There are too many traitors among them. There were, and perhaps there are now. This topic has been discussed to death. I'm judging from my own perspective: for me, everyone is to blame—the priests, and now these priests in Moscow, starting with Alexy II and so on. If you look at the press, how many of them worked for the KGB! I knew about this before. So, I think, I should become a Catholic. Especially since there's a Catholic right here with me. He is in prison, he's not for sale, he is a priest. To make a long story short, where could I be baptized? Only in the banya. So we went to the banya. My witness was—by the way, you need a witness at a baptism—Ivan Bóhdan. He had one arm, a prisoner from Western Ukraine.

V.O.: Was he brought from Vorkuta?

S.B.: There was some kind of uprising, I think, in Kazakhstan, in Dzhezkazgan. I don't know where they brought him from, Ivan. From Dzhezkazgan, from Kazakhstan, or from the northern regions. I don't remember exactly. So much time has passed.

V.O.: About the baptism. You said a Catholic priest baptized you.

S.B.: So, this Ivan Bóhdan, he's a Uniate, was my witness. Račiūnas Pranas baptized me. I remember it for the rest of my life.

When we moved to Ukraine as a family, my wife’s uncle, Uncle Vitya Bóhdan, lived here, whom, by the way, I'll talk about later. The thing is, he was in a concentration camp in the North for many years. And his brother, my wife's father, Ivan Yakovlevych Bóhdan, was also a political prisoner. But that's a separate story, I have their “family history,” their epic, where they were sent, for what, and so on. But I’ll continue on another topic for now.

So, I repeat, when I arrived in Kherson and when this communist plague collapsed—and I don't call it anything else… I could say worse, but in this case, it sounds too soft. When it collapsed in the early nineties, I went to all the demonstrations at the drama theater here in Kherson, where all sorts of people who joyfully welcomed *nezalezhnist* [independence] gathered. Now many people don’t like it. It's clear why. Because they expected a different kind of independence. But here it turned out that this independence was dependent, first on the Russians, then on some other riffraff. I can’t even speak calmly...

V.O.: And our own thieves...

S.B.: Yes. I attended all these demonstrations because I was glad that, thank God, we had finally lived to see the time when Ukraine would be free and independent. Of course, I am not disappointed even now, but judging by everything, this is not the kind of independence we were waiting for.

V.O.: Well, at least one can now speak freely and without fear. And even record it.

S.B.: Here I am, sitting in front of a recording device, thank God. But there is no real freedom of the media. There isn't. In 1991, I myself walked around with posters. An artist friend of mine drew a simple poster for me, and I walked around with it: I wrote “CPSU” and crossed it out with thick lines. I walked around with this poster and was as happy as a child. And I was already over a hundred years old. Well, I'm just kidding. Like a child—we finally made it! And my camp years were not in vain! The sacrifices were not in vain!

I think it was in 1993 that I started looking for channels through which I could get closer to any organization, any people, just so I could contribute to the common cause of Ukraine’s independence. And for me, the turning point was meeting people from Rukh. I didn't know at the time that there was such a person as Chornovil... But I met the Kherson Rukh members and became a member of Rukh. I didn't care where I went, as long as it was against the communists. It didn't matter to me with whom, as long as it was against the communists. I have to repeat that again.

V.O.: And I see your little book here titled *Abracadabra. The Prose of Life in Rhymes*, Kherson, 2000. There's a short foreword here by O. S. Tkalenko, chairman of the Kherson Oblast organization of the People's Movement of Ukraine (Rukh). Did they help you publish this little book of poems? Yes, it says here that the author expresses his deep gratitude to the Kherson Oblast organization of the People's Movement of Ukraine for the assistance and help provided in publishing this collection.

S.B.: So, I got acquainted with Rukh, and for the third time I want to say: I didn't care where I went, as long as it was against the communists. They were my worst enemy, and they remain so. They ruined the nests of my entire family, my wife’s family—the communists ruined everyone. Therefore, even without knowing the Ukrainian language, I joined Rukh. And I don’t regret it. They also helped me financially to publish a collection of poems titled *Abracadabra*. I don’t want to name the amount, it’s not large, but they helped me publish a hundred books. By the way, since I've started talking about the collection, let's continue.

At first, I had the idea to sell them for a hryvnia or two to compensate a little for the expenses. Then I decided: no, I'm not going to sell them. These collections were not written for sale. I left a few copies at Rukh for them to distribute among their colleagues, and I sent a few copies to Moscow to the Solzhenitsyn Foundation. I gave thirty collections to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. It’s right here next to me, one stop away. Thirty. For them to sell or give to their parishioners. I only have five left. I gave away the sixth one today. It was a pleasure for me to give this collection to Vasyl Vasylyovych Ovsienko. In short, I am not a mercenary person; I just like to give things to people. These are not some fairy tales about Buratino. Those are for children, and this—*Abracadabra*—is for adults.

V.O.: Thank you. Let this book be in the library of our Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group.

Told by Semen Ivanovych Butin in the city of Kherson on February 22, 2001. Recorded by Vasyl Ovsienko.

Semyon Butin. *Abracadabra. The Prose of Life in Rhymes*.—Kherson, 2000.—74 pp.

On p. 64:

“Of two who are talking, one is an informer.”

Honoré de Balzac

Вымерли давно мамонты,

Но один остался живой.

Это Валентин Мамонтов,

Магаданский поэт хромой.

Заловил меня хитро в ловушку,

В общежитие пригласил.

Выпили спирт под горбушку

И Мамонтов мне предложил:

Пиши под диктовку листовку,

Отправим в Одессу ее.

Вот адрес. Конверт – не винтовка,

Не бойся. Имя поставь свое.

Вот так написал я листовку –

Хрущевскую банду ругал.

Не брал я в руки винтовку,

А просто Кремль проклинал.

Сдал он меня чекистам:

“Эпитафию” написал:

Якобы я не чистый,

Против совдепии стал.

Сдал в ресторане “Арктика”

Капитану Козлову, в ЧК

Провокатор – литовец из Балтики,

Выбил бокал у меня.

А дальше игра как по нотам.

Пятдесят восьмая и срок.

К истребительно-трудовым работам

(Музыкантом я выжить мог).

Не успел еще выйти из зоны.

Две статьи – и опять новый срок.

Не хватало мне в зоне озона,

(Верою в Бога я выжить мог).

Теперь я сижу и взираю.

Из окон в решетках тюрьмы.

И “мамонтов” тех проклинаю,

В мерзлятине Колымы.

.