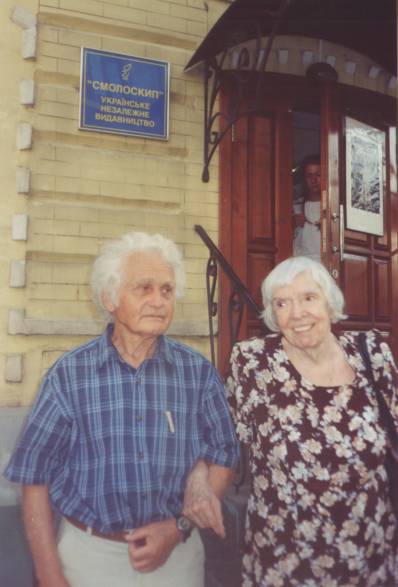

Meeting of Ukrainian political prisoners with L.M. Alexeyeva and Y.F. Orlov

(Smoloskyp publishing house, July 18, 2008)

Edited October 17, 2015:

V.V. Ovsiyenko: July eighteenth, 2008, Friday, four o’clock, the Smoloskyp publishing house, a meeting of Ukrainian political prisoners with Lyudmila Mikhailovna Alexeyeva and Yuri Fyodorovich Orlov.

Y.F. Orlov: I was in the SHIZO in camp No. 37. They brought me out, and in the corridor (it’s a small SHIZO) they interrogated me about Valeriy [Marchenko]. I didn’t have anything; I didn’t know anything.

Voice: And if you had known, you wouldn’t have said.

Y.F. Orlov: Well, that’s what I’m saying, that I didn’t know anything.

Voice: Well, may God grant you health.

L.M. Alexeyeva: They were in camp No. 37 together, he says. How pleasant to reminisce.

Voice: [inaudible] he said, because he knew your intellect, he knew your level, and to meet you in that camp as a friend, as Sakharov’s assistant, was a great honor for him, a great joy, and the fact that the three of you wrote that document, for him that was also, as they say…

Y.F. Orlov: It wasn’t just the three of us, Plumba was there, right?...

Voice: Kiurent was there?

Y.F. Orlov: Yes.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And Antoniuk.

Y.F. Orlov: Well, I know Antoniuk…

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Oh, Zinoviy Antoniuk has arrived.

Voice: I thought he wouldn’t come.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Let’s perhaps sit down at the table, because we’ve already started reminiscing. Let’s sit here, I’ll introduce you, then we’ll talk. Please, over here, to the table. Nina Mykhailivna [Marchenko], over here, please. There are young people here who might not know her. Sit down, sit down here. I’ll stand.

Voice: No, no, I’ll sit over there.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: There are three spots here, Nina Mykhailivna.

Voice: And you? I’ll just [inaudible].

Voice: Sit in the middle.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: In the middle, yes?

Voice: I have a suggestion! As Kotvintsev used to shout in the 37th: “I have a suggestion!” Let’s put these two bouquets on the windowsill.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Yes, yes, because you can’t see the people. Or we can put them on the floor, right?

Voice: No, you can’t put flowers on the floor, let’s put them here.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Okay, let’s do it, like this. So, esteemed ladies and gentlemen, we are very happy to welcome you to Ukrainian land. Lyudmila Mikhailovna has been with us more than once, but you, Yuri Fyodorovich, it seems this is your first time visiting us, isn’t it?

Y.F. Orlov: Well, it’s not my first time in Ukraine. The last time I came, it was to Lviv…

L.M. Alexeyeva: But that was before the camps, and this is the first time since the camps.

Y.F. Orlov: First time since the camps, yes.

Voice: As a foreigner.

Voice: What do you mean a foreigner? He’s one of us anyway.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Well, allow me. I think I can introduce our guests in Ukrainian, because they are in our dictionary—the “Dictionary of Dissidents.” There are entries about them there. By the way, Lyudmila Mikhailovna Alexeyeva will have her birthday the day after tomorrow; she will be eighty-one years old. (Applause). And one more thing, maybe someone doesn’t know, her surname is Slavinska…

L.M. Alexeyeva: Pardon me?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Slavinska. Born Slavinska, she is from Yevpatoria, so she is our compatriot. And Yuri Fyodorovich was born in Moscow, but he spent his childhood in the Smolensk region, and the Smolensk region is essentially Belarus, so they are our compatriots.

I will say a few words about Mrs. Lyudmila Mikhailovna Alexeyeva. Her father was killed in the war in 1942; she studied at Moscow University, then in graduate school, was a scholarly editor, a research fellow at the Institute of Scientific Information, and after Stalin’s death and the exposure of Beria, she had what you might call a cognitive breakthrough. As early as 1956, her apartment in Moscow was one of those centers where dissidents would gather and discuss issues. She was very active in the Daniel and Sinyavsky case—that was in 1965–66. She created an unofficial Red Cross, which collected aid for political prisoners and their families. That was back in 1965–66. When the campaign around the Ginzburg-Galanskov trial began, Lyudmila Mikhailovna signed letters in their defense, and in 1968 she was expelled from the CPSU and fired from her job.

So, the sixties were a pivotal and very active time for her. Lyudmila Mikhailovna participated in the publication of the “Chronicle of Current Events” from 1968 to 1972, and her role was quite significant: she retyped the editorial copy, she retyped Anatoly Marchenko’s “My Testimony,” she retyped Sakharov’s “Reflections on Progress,” and her signature is on many documents of the Helsinki Group. She was warned in 1974 about the inadmissibility of such activities, for which she could be punished. She participated in press conferences on the occasion of the Day of the Political Prisoner in the USSR in 1975–76 (that’s October 30). When Yuri Fyodorovich invited her to join the Moscow Helsinki Group in 1976, she accepted the proposal. So, she is a founding member of the Moscow Helsinki Group. She agreed in advance that if she were thrown out of the country, she would represent the Moscow Helsinki Group abroad. And that’s what happened. Lyudmila Mikhailovna collected a great many Helsinki materials; in particular, she made a special trip to Lithuania on a business assignment. Priests and schoolchildren were being persecuted there. She maintained ties with Ukrainians. Many Ukrainians stayed at her place when they traveled to visit relatives in the camps, bringing back information from there… Where is your book? They took your book. No, no, not that one. I read that Nina Strokata and Alla Marchenko visited her. Alla Marchenko, by the way, is present among us.

So, shortly before the arrests of the Helsinki Group members began, Lyudmila Mikhailovna went abroad. She was allowed to leave on February 10, 1976, but on the 9th, the day before, Yuri Fyodorovich held his last press conference at her apartment. On February 10, Lyudmila Mikhailovna had already left for abroad…

L.M. Alexeyeva: No, Yuri was arrested on the 10th, and I left on the 22nd.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: The 22nd? Ah. Abroad, Lyudmila Mikhailovna did an enormous amount of work. She prepared the complete edition of the Moscow Helsinki Group documents, worked at Radio Liberty and the Voice of America, where she hosted separate programs, and had a great many publications. In 1977, she received an offer from the United States Department of State to write a reference guide on the currents of Soviet dissent. She did the work well and saw that this work was growing into a monograph. In 1974 [1984], this book, “The History of Dissent in the USSR,” was published. It’s a fundamental work, about three hundred and fifty pages, and I want to note that the first essay in this book is “The Ukrainian National Movement.” 35 pages about the Ukrainian national movement—it comes first. The book contains photographs. Yesterday I counted: there are 65 photographs of Ukrainian political prisoners here, maybe even more. Ukraine is the best represented in this book. For me, it is a reference book, one of the most valuable sources on our human rights movement.

Lyudmila Mikhailovna returned to Russia in 1992. By then, the Moscow Helsinki Group had been revived, and in 1996, Lyudmila Mikhailovna became the head of the Moscow Helsinki Group, and she still heads it today. I think she will tell us about her current activities herself. From November 1998 to November 2004, Lyudmila Mikhailovna was the president of the International Helsinki Federation.

I will also say a few words about Yuri Fyodorovich Orlov. On August 13, he will be eighty-four years old, but you wouldn’t say he looks it. I already said that he was born in Moscow and grew up with his grandmother in the Smolensk region. He is a war veteran; he took part in the capture of Prague and was demobilized in 1946.

L.M. Alexeyeva: But he didn’t take Prague in sixty-eight, a little earlier.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Not in 1968, true, but in 1945. He was a student at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, then the physics department of Moscow University, a research fellow specializing in elementary particle physics; he prepared his dissertation but didn’t have time to defend it. The criticism of Stalin’s cult of personality began, and at one of the party meetings where the cult of personality was being criticized, Yuri Fyodorovich spoke out sharply, saying that Stalin and Beria were murderers who were in power. He put forward a demand for democracy based on socialism. This anti-party outburst was “suppressed”; he was fired from his job and expelled from the party. There was no work; he had to go to Armenia and worked there for 16 years. In Armenia, he defended his candidate and doctoral dissertations, and there he was elected an academician of the Armenian Academy of Sciences.

In 1972, he returned to Moscow and immediately resumed his civic activities. Already in 1973, he wrote a letter to Brezhnev titled “On the Reasons for the Intellectual Lag of the USSR and Proposals for Overcoming It.” This letter went into samizdat. Of course, the Soviet leadership did not like such things. In 1973, Yuri Fyodorovich founded the Soviet section of “Amnesty International.” By the way, our Mykola Rudenko was also a member. Is Raisa Rudenko here today? She is. Of course, he was fired from his job and got involved in human rights activities. He held press conferences for the Day of the Political Prisoner in the USSR. His work “Is a Non-Totalitarian Type of Socialism Possible?” went into samizdat—this was in 1975. Of course, there were no positive examples of socialism in the world, but the idea of socialism with a human face was popular at the time. When the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe was signed in Helsinki, the opinion spread among dissidents that the West had lost, Moscow had won, Moscow had gained most-favored-nation status in trade, and Moscow had affirmed the borders that were established as a result of the Second World War. But Yuri Fyodorovich found a positive here. Détente, which seemed like a defeat, could in fact be transformed into a fulcrum for the human rights movement. It was he who came up with the idea of creating groups that would monitor how the Soviet Union was or was not fulfilling the agreements signed in Helsinki. This was a truly brilliant idea. It was Yuri Fyodorovich who thought of it. It was this idea, the implementation of which, along with the implementation of other lines of pressure on the Soviet Union, ultimately led to the collapse of the Evil Empire; it was destroyed. This was a truly brilliant idea, and I want to emphasize that.

We have gathered in a room where Petro Grigorenko is present everywhere. Here, you see, is a photo exhibition of Petro Grigorenko. I want to note that it was Yuri Orlov who determined that the central figure for us was Major General Petro Grigorenko, bear that in mind.

Of course, such activity could not last long. Mr. Orlov headed the Helsinki Group for only nine months and was then arrested. This happened on February 10, 1977. The investigation lasted almost a year, and he got the maximum sentence—seven years in strict-regime camps and five years of exile. He was sent to the Perm camps. In the Perm camps, he was with Oles Shevchenko, with Zinoviy Antoniuk, with whom else?

Y.F. Orlov: [inaudible] for a bit was [inaudible].

V.V. Ovsiyenko: A little with Vitaliy Shevchenko. And you, Mykola Matusovych, were you there too? You were. Yuri Orlov did not manage to serve out his term to the end… Well, he served his prison term to the end, but he did not complete his exile in Yakutia. In 1986, Gorbachev’s negotiations with the West began, and someone had to be released. Of course, Yuri Orlov was in the queue, probably one of the first, and in 1986, on October 5, he was deported to the United States. A little earlier than us, because we were released in 1987–88.

Of course, there he took an active part in the work of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe and was elected honorary chairman of the International Helsinki Federation. He now comes to Russia almost every year, but he currently lives in New York state and is a professor at Cornell University. You will tell us about your mission, why you came to Kyiv, yourselves. I have introduced all of our honored guests, but I don’t know what to do now—introduce all of us?

Y.F. Orlov: Maybe there will be questions?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: But still, shall we name them? Here we have Raisa Rudenko, here is Zinoviy Antoniuk, here is Oles Shevchenko, here is Levko Lukyanenko, Vasyl Lisovyi, Mykhailo Horyn, Bohdan Horyn, Hryhoriy Kutsenko—I am naming the political prisoners—Levko Horokhivskyi, Nina Mykhailivna Marchenko—she is our “equal-to-the-apostles,” almost like a political prisoner. Alla Mykhailivna—she is Valeriy Marchenko’s aunt. Further on, there, in glasses, sits Vitaliy Shevchenko, behind him is Mykola Plakhotniuk, and over there in the doorway stands Mykola Matusovych. It seems I’ve named all the political prisoners, right? The rest are not political prisoners, so let them wait a bit later, let them sit for a while…

I would like to give the floor to Lyudmila Mikhailovna. I haven’t shown this: this book, “The History of Dissent in the USSR,” has already had several editions. I have the 1992 edition and this one from 2006. The documents of the Moscow Helsinki Group have also been published in Moscow. And here is a very dangerous book: “Dangerous Thoughts” by Yuri Orlov [M.: Moscow Helsinki Group. 2006]. It was just brought to Kyiv. I think this book will be properly presented here.

Voice: The documents of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group are also here, right?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Yes, that’s right. For their outstanding services to the Ukrainian human rights movement, we included biographical entries for Lyudmila Mikhailovna and Yuri Fyodorovich in our “International Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents. Ukraine.” This is a project that covers the post-Soviet space, twenty-two countries. So far, only the Poles have published their two volumes, and we, the Ukrainians, the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, have published our two volumes. So you are in these volumes, have you seen them?

L.M. Alexeyeva: Yes.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Oh, very good. Now, Lyudmila Mikhailovna, I think it would be best to give you the floor.

L.M. Alexeyeva: No, just a moment, I think if we go by seniority… Such a rare occasion: there is a person older than me.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: The first chairman of the Helsinki Group.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Secondly, he’s my superior, he founded the Moscow Helsinki Group. You said he is the honorary chairman of the International Helsinki Federation, but you didn’t say that he is the honorary chairman of the Moscow Helsinki Group. Therefore, the floor goes to the honorary chairman.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Well, please.

Y.F. Orlov: I protest, but I am forced…

V.V. Ovsiyenko: To submit to a woman.

Y.F. Orlov: To submit, yes. When I returned to Moscow and got involved in the human rights movement…

L.M. Alexeyeva: One moment—does everyone understand Russian, yes?

Y.F. Orlov: I can speak English, if you like.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Let’s do it in Russian.

Y.F. Orlov: …by that time Lyudmila Mikhailovna was already far ahead in her activity and in her connections with dissidents from other republics, especially Lithuania and Ukraine, precisely Lithuania and Ukraine. I can say that, in principle, I knew Ukraine quite well, I had been there many times… I had never been to Kyiv, but I had been to Kharkiv on physics business, because there’s a well-known Physics Institute there, a linear accelerator, I’m a specialist in accelerators, and I was there two or three times, met with Volkov there, there’s a theorist there. And when I began human rights activities in Moscow, the first person I very actively defended—I released several documents in his defense, together with Tatyana Khodorovich—was in defense of Plyushch.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Leonid Plyushch, right?

Y.F. Orlov: You know him, right? Leonid Plyushch from Ukraine. Together with Tanya, his wife, we went…

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Zhitnikova, right?

Y.F. Orlov: With Zhitnikova, we went to the psychiatrist Snezhnevsky, who was the author of the famous, I would say criminal, theory of “sluggish schizophrenia.” These documents in defense of Plyushch were later, of course, used to incriminate me in court, about seven documents in his defense. Then—I’m talking about direct connections—in 1976, Mykhailo and Bohdan [Horyn], they were just mentioned here. I went to Western Ukraine for a combination of reasons. First, to meet with Kandyba. When Kandyba was released—listen, Lukyanenko—he came to my place, and at our home we provided him with clothes, whatever he needed, and from our place he went to Ukraine, to Lviv. But there they put him under administrative surveillance in Pustomyty, if you remember… And what happened? Immediately after his release, he wanted…

V.V. Ovsiyenko: This was 1976?

Y.F. Orlov: ‘76. He wanted to join the Moscow Helsinki Group. Then Valentin Turchin and Alexander Ginzburg went to see him, remember? They went to see him to ask him…

L.M. Alexeyeva: Yes, you started discussing it in Moscow.

Y.F. Orlov: Yes, of course. They went to him specifically to ask him not to do it, to give himself a rest. They would arrest him immediately. Because we Muscovites were not arrested right away, because we were in the public eye, it’s the center, we knew all the journalists, we knew some political counselors at the embassies and so on. But in Ukraine, they would have arrested him immediately. After that, we weren’t sure he would refrain. As you know, he joined the Ukrainian Helsinki Group anyway, but that was later, after my arrest. So, I went, one of the goals was just to see him so that he wouldn’t feel isolated, because, in my opinion, one of the reasons he immediately wanted to join the Moscow Helsinki Group was that he was afraid of being cut off from the movement. And here we were, visiting him. That was one of the reasons. We arrived in Lviv and Pustomyty. We went to his place in the morning, spent the day. He was under surveillance, he wasn't allowed to leave the house after six o'clock. We went out, and he… he knew this, but he took half a step outside the gate, beyond the garden fence—and they jumped him right away. They arrested him, and they added another six months of surveillance. They temporarily arrested us too and held us overnight at the local precinct. But that’s nonsense. In the morning, we went to Lviv. He said right during the incident that they would have done it anyway, so whether it was this or something else—it made no difference. We told him, we begged him: “Hang on, don’t go out.” But, as you know, he later joined the Ukrainian Helsinki Group.

There, in Lviv, we met with Bohdan and Mykhailo Horyn. And how is it in Ukrainian—Hóryn?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Hóryn. Hóryn, yes.

Y.F. Orlov: For some reason in Moscow, we always said Horýn.

L.M. Alexeyeva: No, I said Hóryn. The first person to call him Horyn for me was Nina Strokata; she knew how to say it.

Y.F. Orlov: It was, I would say, a very pleasant meeting for me—two intellectuals, working at the time as stokers. Well, that’s a normal, so to speak, Soviet phenomenon in that sense. They showed me the city with its architecture, with some pictures, bas-reliefs—I remember, right?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Yes, bas-reliefs.

Y.F. Orlov: Interesting. Then I visited seven prisoners, a couple or three families—wives, mothers, and one of the mothers… There was an idea to go to a village in Galicia. One of the mothers took us to the village, and it was impossible for a Russian to rent a house in Galicia, but she explained—they are Russians, but good ones. And, of course, they rented us an apartment immediately. It was very nice there. I visited other villages where there had been resistance. They told me what was what. And in one village, they explained that out of a thousand people, about thirty worked for the KGB, receiving money. It was everywhere. In Yakutia, the proportion was about the same. That was the extent of my Ukrainian activity. After arriving in Moscow, I wrote a report on the situation of the families of political prisoners in Ukraine. It’s one of our documents, you can find it in this collection.

When I was arrested, on February 10, 1977, a year later the investigation and trial were over and I was sent to the thirty-fifth camp, to the Perm camp. There I again came into close contact with Ukrainians, political prisoners from Ukraine—Valeriy Marchenko, Zinoviy Antoniuk, Matusovych, Marynovych, Shevchenko…

Voice: No, that was in the thirty-seventh.

Y.F. Orlov: That was the thirty-seventh, not right away. In the thirty-seventh, I immediately met Dasiv.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Kuzma Dasiv?

Y.F. Orlov: Kuzma Dasiv, he has already died. He, by the way, at that time… I’m going to jump around a bit now. When I was transferred to the thirty-seventh camp, so that we wouldn't meet, they were taking out Paruyr Hayrikyan, you know him, right?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Of course, of course, everyone knows him.

Y.F. Orlov: Of course. Dasiv pushed him into the drying room, and he pushed me into the drying room, and we met for five minutes.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Did you dry out?

Y.F. Orlov: Yes, Paruyr explained to me who was who in the camp, who worked for whom. And they took him away; I never met him again. I went to his trial in Armenia in 1974. His last trial. They gave him another seven years there.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Although there, too [inaudible].

Y.F. Orlov: Yes. Dasiv showed me where fifty rubles were buried.

L.M. Alexeyeva: A treasure.

Y.F. Orlov: Yes. I didn’t use those fifty rubles for a long time, but then, in the end, I used them. I gave them to the librarian so that she would take my scientific paper out of there. And how did I know she was getting out—she had gotten involved with a prisoner {Basha} from the thirty-seventh camp and was marrying him, and he was being released. I figured it out, since I think I’m a good psychologist, I figured out that she…

Voice: Wouldn’t sell out.

Y.F. Orlov: Yes, and that she had gotten involved with a political prisoner. And she took that paper out. In the thirty-fifth camp, they helped me a lot right away. Valeriy Marchenko with Antoniuk, there was a very well-organized Ukrainian group there. There were also three UPA men there—Pidhoretskyi, Verkhovliak… Verkhovliak?

Voice: There is such a person, Verkhovliak.

Y.F. Orlov: Yes, yes. And I’ve forgotten the third name.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Myroslav Symchych? He’s still around, thank God, alive and well.

Y.F. Orlov: He is?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Yes, he lives in Kolomyia.

Y.F. Orlov: So Verkhovliak and Pidhoretskyi immediately sewed me a new suit compared to what the KGB gave me. [inaudible] a black one, a good black color suit, and that was very good. As soon as I arrived at the camp, I proposed the idea that we write a report on the situation of prisoners from inside the camps. I didn’t have any experience myself yet, but I had experience of transportation. I took on that part, and the preamble—an assessment of how many prisoners I thought there were in the USSR, of different types, this type, that type, chemical exiles, for example, are also de facto prisoners, and so on. I wrote that in the preamble. I wrote about the transportation of prisoners, and others took on other sections—food, medical care, treatment, etc. How all this was transmitted, you probably know in general. In various ways. I think I don’t need to explain it to you, but I’ll explain anyway. For example, on cigarette paper. When you bought cigarettes, when there was permission for the commissary, if anyone got it, there was cigarette paper. And in the thirty-seventh camp, I used technical tracing paper. You write on the cigarette paper with a very, very fine pen, then you roll it up, then wrap it in plastic, you get a small ball like this, and you swallow it. And then you pass it on during a visit.

Voice: There was another way…

Y.F. Orlov: No, of course, of course. I passed one or even two scientific papers in a completely different way… When I had sugar, well, one of us always had sugar. There were about four of us in the thirty-seventh camp, or five, depending, and someone would have sugar. I would make a sugar solution so that when you wrote, it would be visible on one side after ironing, but on the other side it would be invisible without an iron, so it could be transported. I would sit and write—you take a blade of grass, a narrow capillary, dip it in this water, it rises up and you have a writing tool. And you write. You see nothing, you write and you see nothing. Then the guards appear, immediately… Just an empty sheet of paper. Then you continue, and you don’t know if you’re writing in the right place or the wrong one. If you made a mistake, you can’t fix it. But you write anyway. That’s how I sent things. What happened? I had two notebooks with such notes, but it was impossible to pass them on. I had one visit, then a second. There were no more visits, for five years there were no visits. But there was a prisoner there who had once deserted from the army. He escaped to Turkey. From Turkey, they handed him back, and he got ten years. He finished his sentence, he was getting out. And before his release, of course, they put him in the SHIZO for three months so that none of what I’ve explained would be possible. But when he was getting out, it turned out that his wooden camp suitcase was still in the camp zone. A guard came and told one of the prisoners, one they trusted, that the suitcase was needed. And he didn’t know, he asked me: “Do you know where it is?” I said: “I know where the suitcase is.” And we went. And the guard trusted this man. And I could trust him, maybe not, but I remembered my childhood, I told him: “Listen, what’s that over there by the window?” He looked, and I put those two notebooks in the suitcase. The prisoner’s name was Karpenok.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Yes, yes, I know him.

Voice: A Belarusian?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: A Belarusian, yes.

Y.F. Orlov: Yes.

Voice: I know him too.

Y.F. Orlov: Mykhailo, I think. Karpenok lived in the North Caucasus, at least he returned to the North Caucasus. He understood. He tells the guards: “They’re empty notebooks.” And they let them through. You could buy notebooks in the commissary. School notebooks. They didn’t notice anything, he got them through. He understood they were from me.

L.M. Alexeyeva: And you didn’t have time, you couldn’t tell him, you just put them in?

Y.F. Orlov: No, no, he understood, he’s a smart guy. But he came to Moscow at first without them, to see who these people of Orlov’s were, just in case. He met my friends, my family, realized they were normal people, and the second time he came with the notebooks. They had to be ironed, every page, and a text appeared. That’s how it went. A different method, so to speak. And my third method was—I didn’t write about this in the book, because when I was writing the book, Soviet power still existed, it could have been useful, so I didn’t write about it.

L.M. Alexeyeva: In case they imprison you again?

Y.F. Orlov: No, not me. But when I was getting out, I told this idea to a few people. The idea is basically this. You have a sheet of paper. Let’s say, from a school notebook, with a grid. But that’s not very good, it’s better if it’s under a blank sheet. But the squares are still slightly visible. The idea is to write what you need in the correct squares. And how do you know where the correct squares are? Each letter had its own code. The very last sentence of each letter contained the code for that letter. But it changed every time. And the code was simply this: the length of a word determined how many squares to count from the beginning… Understand? Then the next length, and the next, and so on. They sent my letters for inspection—they couldn’t decipher anything, because it’s very simple. You have this square, sometimes two, because the word goes this way, and so on, and immediately there’s the next square. For example, you can fill it, or you can leave it empty. You can put one letter, or you can put three. Or you can make a checkmark and include a whole sentence there, right? It was chaotic; there was no order there, and in the next letter, the code would be different anyway, not this one. Understand? They didn’t discover this. So I'm telling you about this code once more.

Well, that’s about my connections with Ukrainians. If there are questions, please ask.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And now, what is your mission, why did you come to Kyiv?

Y.F. Orlov: We want to renew or revive the Association of Helsinki Committees on a somewhat new basis. This idea was born in Helsinki, among us—Lyudmila Mikhailovna, Daniil Meshcheryakov. He has already done a huge amount of preliminary work for such a unification, because there was this Helsinki Federation, but as a result of a crime—the cashier or accountant there…

L.M. Alexeyeva: The treasurer.

Y.F. Orlov: No, the treasurer did nothing.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Oh, a cashier, they just trusted him, no one checked him.

Y.F. Orlov: Yes. To make a long story short, a huge sum of money was stolen, and the Federation was declared bankrupt, but the committees are still working anyway. And we need representation in international organizations, we need to coordinate the work of various committees, so an organization is needed for these purposes. Well, and now, considering that experience and many years of work, we think that we can do it better now, and for this purpose, they asked me to come here too.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And where are you working now?...

Y.F. Orlov: I am at Cornell University, I am a professor in two departments—physics and so-called government. It's actually a department of social sciences—government. There, of course, I will lecture on human rights, on relationships. My plan is this: this fall semester, I teach physics for graduate students, a special course, and the spring semester, the next one, after this—I teach a course on the social sciences, on the relationship between the government and human rights structures. It’s a very interesting thing.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Is that about relationships in America?

Y.F. Orlov: No, no, it’s a European… [end of track] …the whole complex of relationships between public and state…

L.M. Alexeyeva: Between society and the authorities.

Y.F. Orlov: Yes, but in the sense of human rights. In this field. That’s what I’m doing.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: I see. And how shall we proceed—maybe Lyudmila Mikhailovna will speak, and then?...

Y.F. Orlov: What questions, questions for Lyudmila Mikhailovna as well, that would probably be easier.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Well, let me speak first, then questions from whoever has them. Agreed?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Yes, please.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Well, first of all, I’ll say that in the years when Yuri Fyodorovich, along with many of those present here, was resting in the camps and in exile, I was working in emigration in America as a representative of the Moscow Helsinki Group, and in particular I met with representatives of “Smoloskyp.” No sooner had I arrived than they were there, right on the spot, they came to meet me to find out what was happening here and generally how we could be useful to each other. So when I learned that I would be coming to Kyiv and that this meeting would be at the “Smoloskyp” publishing house… Well, we’ve lived to see it, thank God, because when we met in America, it never even occurred to us that one day Smoloskyp would be able to open an office in Kyiv. This is very pleasant and joyful.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: It has been here since 1992.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Well yes, but I met with them in 1977–78—did we think about that back then? Now. In Ukrainian I’m like a dog—I understand everything, but I can’t say anything, so I understood everything that Vasyl Ovsiyenko said. Firstly, thank you for your kind words about me, and secondly, I was very pleased to hear Vasyl Ovsiyenko emphasize, even twice, that Yuri Fyodorovich’s idea of creating the Helsinki Group was a brilliant idea. It seems simple, right, but they say—everything brilliant is simple. Not everything simple is brilliant, but everything brilliant is simple. This really is a brilliant idea. You know, I am bound by the cowardice of diplomats who don’t allow… Well, they invite you first for a talk, and then they say: “No, no, no, nothing in the press release, otherwise we’ll have diplomacy issues.” And so I’ll put it this way, circumspectly. A few days ago, three human rights defenders, myself included, met with the president of a country that is a member of the European Union. He asked us about the current situation in Russia, what we expect next in our Fatherland, and then he said that we in the West highly value what the Helsinki Groups did in the Soviet Union, because they turned the Helsinki process from various other subjects toward human rights, and if there had not been the Helsinki process, which they initiated, there would not have been perestroika after the collapse of the Soviet Union, everything would have been completely different. That’s how they see it. So how else can you describe an idea that led to such results? In the end, a free and independent Ukraine is also a result of perestroika, and therefore, to some extent, its beginning was in the Helsinki process. So, I want to emphasize that this idea is specifically Yuri Fyodorovich’s idea. As they say: defeat is always an orphan, but success has many parents. I have heard a hundred times who gave birth to this idea, who suggested it to Yuri Fyodorovich, and so on. And I—Yuri Fyodorovich won’t let me lie—was very close. And I was in various groups many times before 1976, where Yuri Fyodorovich was also present. I saw how he, I would say, maniacally talked to people about one thing all the time. He was constantly thinking about it, you see? He was thinking about how our powerless society in an authoritarian state could force the state to treat its citizens with respect, and how to encourage the West to help us more actively in this. And no matter what company you met him in—smart, average, foolish—he would always ask everyone about it. And everyone would talk to him, and he would sit and listen. He never interrupts anyone, just sits and listens, only asking questions. He asked me too. I also thought about something, said something, but it doesn’t occur to me that the Helsinki groups, the Helsinki process were my idea. No, of course not. He listened, I think (since I didn’t participate in all such conversations), I think he listened to certainly more than a hundred people on this topic. And he stewed it all in his scientist’s head, you see? And a little from here, a little from there—he took this from one person, that from another, and this simple idea was born. And I remember very well how, after Yuri Fyodorovich was arrested, I read in some American newspaper, either The New York Times or The Washington Post, that the Moscow Helsinki Group had fallen victim to its own success. Fallen victim in the sense that the arrests began, and the first to be arrested, though with a week’s delay even though the warrant was issued on the same day as Ginzburg’s, was Yuri Fyodorovich.

Y.F. Orlov: First the Ukrainians.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Yes, back in December. (M. Rudenko and O. Tykhyi were arrested on February 5, 1977. — V.O.). So, I think that this audience will understand that I have no reason to suck up to Yuri Fyodorovich, we already have a good relationship, and therefore I will say—a brilliant idea only comes to the mind of a brilliant person, you see? For some reason, these ideas don’t come to simple minds, they are not born there, they don’t pop out from there. And in this sense, Cornell University is not stupid for having Yuri Fyodorovich lecture on social sciences, because they understand from whom this can be heard. As for the rest—I will add. We definitely know the common phrase that there are no people without flaws. I know there are people without flaws. Yuri Fyodorovich is a man without flaws. All those who were imprisoned with him—a person is tested there, like glass, like crystal, everyone can see what someone is made of. Even though I wasn't imprisoned, I know this, I've been told it a hundred times, and I can imagine it. So, besides the fact that, to put it mildly, he’s not stupid, given that brilliant ideas come to his mind, he is a kind, responsive, selfless, hardworking, modest person. Well, tell me, what else is there, what more is needed? He has everything, and nothing bad. And I’ve known him for many years, and you’ve known him for many years. Who can say a single bad word about him—no one, not even his greatest enemy.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: And the KGB?

L.M. Alexeyeva: That is the very absence of flaws, that you think you have flaws. The last thing we need is for you to think, “I am brilliant, the best, and without flaws.” Then you would be one solid flaw. You know, Yuri Fyodorovich was arrested on February 10, 1977, in my apartment, right before my eyes. They simply took him from my apartment, and on February 22, I left. I already had my tickets at that time, and visas, and tickets, that’s why Yuri Fyodorovich came to my apartment—he was hiding. He came to my apartment because when they gave me a visa, they removed the surveillance on my apartment. So he thought there would be no surveillance, and he came. But the apartment was bugged, and they immediately found him at our place. One of my first tasks when I arrived in America was… I compiled… Well, it's a book about this thick, maybe a bit thicker, a book like this, called “The Orlov Case.” The Orlov Case has a double meaning. The case for which Orlov was imprisoned, how they developed it—that’s the case he was jailed for. And the epigraph for this book… It’s like the “White Book” on Sinyavsky and Daniel. We compiled it for all political prisoners, and you did too. We—I mean all of us. So I took the epigraph for this book from Jerzy Lec—such an aphoristic and very witty Pole. He has an aphorism: “If someone is ahead of their generation, they have to wait for their peers in very uncomfortable places.” And this is about all our political prisoners, including Yuri Fyodorovich. Very honestly, correctly said. And when he was released in 1986—he finally waited for his generation to catch up with him.

I also want to say that on the one hand, I am very sad that Yuri Fyodorovich lives in America and not with us. Well, such people are needed everywhere, and there are never enough of them. But I remember very well how from the very beginning of our acquaintance… When did you come to Moscow from Armenia?

Y.F. Orlov: At the end of 1972.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Well, we must have met in 1973. So, since 1973, I have heard more than once, when he first explained it to me, then to others. “In general,” he says, “I consider science, physics, to be my life’s work. I am a physicist, but such things are happening here that I have decided to dedicate five years of my life to the fight for human rights.” He said this in 1973, then in 1974, I hear him in another company say: “Actually, I am a physicist, and my calling is science, but I have decided to dedicate five years of my life to the fight…” For some reason, time went on, but he continued to dedicate five years…

V.V. Ovsiyenko: They gave him twelve.

L.M. Alexeyeva: And he got a full seven plus five years of exile. So, when they agreed to release him on the condition that, without asking his consent, they would put him on a plane and send him to America, and there, they are no fools, they immediately took him to Cornell University to do physics, you see? Why do they have so many Nobel laureates, while we don’t have many? Because they approach it more intelligently than ours—both our rulers and our leaders of science. And Yuri Fyodorovich began to engage in physics. And, of course, I can’t bring myself to say to Yuri Fyodorovich, “Come to Moscow,” because the man dedicated not five years, as you correctly noted, and not just to the activity, but to the camp and exile, and if he finally managed to engage in science, what he considers his life’s work, then why pull him away. He’s doing it as much as he can, for another year he will be doing… He’s also involved in Chinese human rights—I, for one, don’t have the stamina for that. And you see how the Lord God arranged it correctly. Yuri Fyodorovich is older than me, usually at this age, scientists no longer generate ideas, and a person loses creative potential, but Yuri Fyodorovich publishes in prestigious physics journals all over the world, and he still has some ideas. He recently told me on the phone: “You know, an idea came to me, and it turned out to be correct, I’ll explain it to you now.” I said: “Yuri Fyodorovich, don’t, I won’t understand anyway.” He says to me: “No, I’ll explain it so that you’ll understand.” He explains it to me, and I understand everything. Then my son calls me right away, I say: “You know, Yuri Fyodorovich came up with something so good, he just explained it to me, I’ll explain it to you now.” It turns out, I can no longer. For all the years he spent on human rights and then paid for it so cruelly, the Lord God extended his time as a scientist.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Compensated.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Yes. And I can wish one thing, and I think each of you does too—long life, both as a person and as a scientist. (Applause).

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Well, how shall we proceed? I would like our conversation to be not only about the past, but also about the present, about our place in society in the past, and now, and in the future. Vasyl Lisovyi. He served seven years, five in exile, then another year.

V. Lisovyi: Yuri Fyodorovich, in post-Soviet regimes, human rights work is complicated by the fact that it is closely tied to political issues. For example, the murder of Politkovskaya. With the level of corruption that exists in both Russia and Ukraine, the courts and investigative bodies are under the influence of this process. Do you continue to study the problems of totalitarian, post-totalitarian society and so on at the university, in this light?

Y.F. Orlov: I think that this question is generally more for Lyudmila Mikhailovna—how exactly one has to act in the situation you just described. In general, the harsher, the more repressive the regime, the greater the connection, of course, between human rights and political activity, naturally. In a totalitarian regime, it is very difficult to separate one from the other. But there is a fundamental difference in methods. In general, human rights is not about the what, but about the how. This is my very deep conviction. In this sense, human rights is not a political activity, because there are other rules for political activity. You can deceive, as in a chess game, that is allowed, it is a war in a certain sense, deception is allowed. From my point of view, in a certain sense not violence, but the threat of [violence] can be allowed in political activity. In human rights work, these methods are not allowed. It is a completely different activity. As for our opinion on political activity, on regimes and so on, on ideological goals, on the political goals of various groups, organizations, classes and so on, again, our concern is not about the what, but about the how. How you achieve your goals—that is the criterion for us. A person, say, of an imperialist mindset—he has a right to that. But he does not have the right to suppress the opposition by violating international norms and agreements. That is, how he does it. If he just publishes and continues to be a monarchist or a Stalinist—that’s one thing. But it’s another thing—how he fights for his ideas. The same applies to progressive ideas or, say, liberation ideas. The same, how is very important.

Voice: Absence of violence or [inaudible].

Y.F. Orlov: That’s a difficult question—about the absence of violence. Sometimes it’s hard to do without mutual violence. Take South Africa, when there was segregation there, for example. Difficult. And Hitler’s regime, and Stalin’s regime, for example. But again, there is always a line. And first and foremost, it is not our concern, as human rights defenders, to use violent methods. But to evaluate political activity—we evaluate it. At least, I do. And we always somehow agree in our opinions.

V. Lisovyi: Yuri Fyodorovich, but the issue here is that protesting arrests or publishing about political persecution was already human rights work. Now the conditions have changed, specifically concerning how to act in conditions of, for example, corruption. That is the question. I mean that if the judicial system works successfully, then human rights work can be carried out effectively. But in conditions of a high level of corruption, the mechanisms of human rights work have already changed. That is, a simple protest and announcement of political arrests are no longer just human rights work. You need to defend a specific person through legal mechanisms. That's the point…

Y.F. Orlov: But now that's the only thing that's being done. For example, the Moscow Helsinki Group is specifically engaged in such defense. At the request of Lyudmila Mikhailovna, I visited Veliky Novgorod. There are human rights defenders everywhere. The human rights defenders there explained and simply showed me how they work. They involved students from the law faculty of the university in their activities. These young people are not corrupt. They defended people who were administratively… not even repressed, but simply suffering from administrative violations.

L.M. Alexeyeva: They were underpaid their pensions there.

Y.F. Orlov: And other things. For example, a woman was evicted from a dormitory because housing conditions needed to be improved. She was evicted from the dormitory and given an order for an apartment. She goes there, and there are people living in the apartment. She ended up on the street, without a home. That’s an example. Students are involved in this. So, of course, the conditions are different.

L.M. Alexeyeva: May I add about Novgorod and the involvement of students? Novgorod is not such a big city. They started doing this a fair number of years ago—involving students in their free legal aid clinic. These students finished their studies, received their diplomas, and were assigned to jobs—one to the court, another to the prosecutor’s office, a third to the police. Five years later, it turned out: wherever they go, their former students are sitting there. They say that the situation in the city regarding compliance with the law has noticeably changed, because even if the students of yesterday have not yet grown to be bosses, in time that will happen too. But at some levels, they are already finding understanding. So, human rights work consists not only in defending each individual person, but also in influencing consciousness in various ways—through students, through the press, and in many other ways—on society and on representatives of the authorities. Yes, and among the representatives of the authorities, not all are corrupt and not all are scoundrels. In general, I wouldn’t take their place, but nevertheless, if you start talking to them, you can get to something human in them. You know, now there is a public council attached to the Moscow police, and we repeat to them like a mantra: “No beating, no beating!” And at first, they were like: “Huh? Oh, yes, yes, no beating.” We’ve been repeating to them like parrots for two years, “No beating.” And now we’ve managed to ensure that when there’s a demonstration in the city, they don’t invite the OMON from other cities, because they don’t yet know that you’re not supposed to beat people. And ours, though reluctantly, mostly agree. Now we’re starting to explain to them that you can’t detain people without reason, on the orders of superiors. And now they don’t beat them, but they detain them. Then they get two or three days on fabricated charges. It’s not a huge deal, but it’s unpleasant. So, you can talk even to these… But is this political activity, explaining to cops that you can’t beat people? In my view, it’s human rights activity, although it’s direct communication with the authorities.

Y.F. Orlov: In the end, in a very broad sense, what we do is to improve and civilize the relationship between people.

L.M. Alexeyeva: And between society and the authorities.

Y.F. Orlov: Yes, in a broad sense.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Levko Lukyanenko wanted to speak?

L. Lukyanenko: Yuri Fyodorovich, may I ask one question?

Y.F. Orlov: What?

L. Lukyanenko: I would like to ask a more philosophical, or historical-philosophical, question. You know, among the Russian intelligentsia, there has long been a belief that it is impossible to democratize Russia. For example, Dostoevsky spoke about this very vividly. You belong to those people who want to democratize. The government is reviving Stalinism, now they are talking about proclaiming Zhukov a saint. In historical terms, we know that in Russia there has always been a certain group or part of the intelligentsia with a pro-Western orientation. There were pro-Westerners in the nineteenth century, in the twentieth. One could say that your groups were pro-Western. Since the time of Ivan the Terrible, there has been this democratic current, but it has always been so small that it generally did not decide Russia’s fate. What do you think is the dominant force now, and what should we expect from Russia? Will it continue the history that has been characteristic of it for the previous five hundred years, or do you, to some extent, believe in the possibility of democratizing this society?

Y.F. Orlov: Is this question for both of us, I suppose?

L.M. Alexeyeva: No, this question is for Yuri Fyodorovich.

Y.F. Orlov: I would say that for me, the question doesn’t exist. I have to do it. Period.

L. Lukyanenko: You know, for me the question of national freedom was and is in exactly the same form. I don’t look at how many enemies of an independent state there are; I act in this direction, and that’s it, it’s my fate, it’s my path. But I turned to you as a very intelligent person who has not just determined his behavior, but who has an understanding of historical processes. Do you believe in the possibility of Russia democratizing?

Y.F. Orlov: You know, if we’re talking from a philosophical point of view, I don’t believe in determinism, and that says it all.

L. Lukyanenko: Yes, I understand.

Y.F. Orlov: Clear, right?

L. Lukyanenko: Yes. As proof of the correctness…

Y.F. Orlov: History depends on me, on us. It's not machines that make history. We do.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Please, Oles Shevchenko.

O. Shevchenko: May I? I wanted to say a few words, not ask a question. I’ll probably speak in Russian so I don’t have to be asked to repeat. When you look at Yuri Fyodorovich, you imagine an academic from an academic environment. We have many examples in Ukraine: if he’s an academician, it means his father was an academician, his grandfather was an academician—a family of academicians. Or doctors.

Voice: A dynasty.

O. Shevchenko: Yes, the environment, the environment is conducive. And it’s hard to imagine that Yuri Fyodorovich comes from a simple peasant family. This book you have here—everyone has seen this book, but for now, they have only memorized its appearance. [Yuri Orlov. Dangerous Thoughts. Memoirs from a Russian Life. — M.: Moscow Helsinki Group. 2006. — 314 p.; Published in Ukrainian: Orlov, Yuri. Dangerous Thoughts: Memoirs from a Russian Life / Yuri Orlov; trans. from Rus. by Petro Romko; foreword by Yevhen Sverstiuk — K.: Smoloskyp, 2012. — 406 p. ]. I assure you, when you start reading it—it’s not just a memoir. You will see that this book was written by an extraordinarily talented man. And a man of extraordinary honesty. He doesn’t try to embellish his biography with anything. I say this because Gleb Yakunin brought it to me with Yuri Fyodorovich’s dedicatory inscription, so I had time to read it. He absolutely does not try to embellish his biography; he writes: “My mother was a street child.” Yes, she lost her father. His mother was indeed a street child. Someone else would have spoken about their mother differently. But he writes it as it was. From a simple peasant family, from the simplest people…

In the thirty-seventh camp, Yuri Orlov was the spiritual leader. You know what it means to be a spiritual leader in the camp. This is a person whose word is considered the most authoritative, and in all doubts or conflicts, they turn to him, and he is the highest judge in the camp. But keep in mind that the full repressive power of the KGB (and all political camps were under the KGB’s control) is brought down on the camp leader. I was first in the thirty-sixth camp. There, Viktor Nekipelov, a member of your group, was such a spiritual leader. But we had a very strong Ukrainian group there. Then they scattered us. In the thirty-sixth, they set a Soviet Union record on me—sixty-six days without being taken to work, that is, with food every other day. Not in a PKT, but in a punishment cell, in the SHIZO. And then they brought my skeleton here to Kyiv for processing, but nothing came of it, so they sent me back, but not to the thirty-sixth, but to you, to the thirty-seventh, where the leader was Yuri Orlov… One might imagine that a political camp is something large. But it was the smallest political camp in the Soviet Union. There were only 20 people in the thirty-seventh.

L.M. Alexeyeva: And police collaborators were among those twenty.

O. Shevchenko: Among those twenty were also police collaborators, and among those twenty, there was always one criminal for whom no moral or ethical norms existed. He would do whatever the administration told him—what dirty trick to pull, what to plant on whom, what to steal from whom. It was mandatory in every camp, and in our small thirty-seventh, there was one too. By the way, about repressive power. There was very little opportunity to communicate with Yuri Orlov in the camp, because, as a rule, it was either the punishment cell or the PKT for him, the punishment cell or the PKT. Sometimes we just felt sorry when we thought: “Let’s hold a hunger strike…” We would say: “Let’s not invite Yuri Fyodorovich. How much more can he take, he gets it bad enough as it is.” The thirty-seventh camp was divided. One part had forty people, where Vitaliy Shevchenko was, and ours had twenty. Once we were sitting in the PKT, and our cells were next to each other. Gleb Yakunin was in one, and Yuri Fyodorovich and I were in the other. And the three of us, in shifts, for eight hours in the work cell, as they say in Ukrainian, stood bent over and turned a crank—the iron handle of a machine tool. Every week we were rotated—one at night, one in the morning, one in the evening. We cranked it for eight hours. And from the other end came a wire mesh, it was called a rabitsa. This was the work of a priest, the work of the physicist-academician Yuri Orlov under the dear Soviet government.

I want to say that to a certain degree, I am happy to have ended up there. I know that in the camp—one, then another—I became better than I was before the camp, because I had the opportunity to communicate with people who also exist in freedom, but here they are dissolved in a huge environment, while there they are concentrated.

L.M. Alexeyeva: And there they gathered them all for you.

O. Shevchenko: Yes, concentrated. And among such people, of course, you gain firmness, self-confidence. The camp, of course, educates…

Voice: Better than a university.

O. Shevchenko: Yes. For that, I want to say: thank you, Yuri Fyodorovich, for having served time with me. (Laughter, applause).

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Professor Mykola Rozhenko has been raising his hand for a long time. True, he wasn’t imprisoned, but he was indeed kicked out of the Institute of Philosophy.

M. Rozhenko: My [inaudible] specialty is quantum logic. That is Yuri Fyodorovich’s specialty—quantum logic. And something else. Your articles on quantum logic appeared in America while you were still in prison. From this, I concluded that your works were passed on from those GULAGs. You see, I figured you out, as you say. And my question is this: will quantum logic and, accordingly, the quantum computer enter our everyday, customary life situation in the same way the classical computer did? Will we have to wait long for the quantum computer or not?

Voice: A very difficult question.

Y.F. Orlov: I’m afraid any answer could be mistaken, because there were great hopes, for example, for the thermonuclear reactor, right? The Tokamak, and so on. Say, thirty years ago, everyone hoped that in about twenty-five years the energy problem would be solved, thermonuclear reactors would be working. But now that has been pushed back by another fifty years or so. This, it seems, is very difficult—quantum computers. I published works on quantum computers even after my prison term.

M. Rozhenko: Your latest works on quantum logic are from 2000.

Y.F. Orlov: Yes, how, perhaps, a quantum system could be replaced by a classical one with the same results, for example. I don’t know, it’s very difficult, because you know how many bits are needed for it to really work usefully—at least a thousand. And for now, we have a few units.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Bohdan Horyn wants to say something.

B. Horyn: In Ukraine, people who are highly respected are often addressed as “highly esteemed.” So I address you, Lyudmila Mikhailovna, and you, Yuri Fyodorovich, as our highly esteemed and dear guests. It is a great joy for all of us that you are in Kyiv, the capital of our Ukraine, and there is no doubt that your brilliant idea is part of the struggle for the independence of many republics, including Ukraine. I have the double joy of meeting you, for I recall that thirty-two years ago we met in Lviv. We talked about many things in Lviv, in my apartment, and then in the Carpathians, when in the forest one could see no one, and only my brother Mykhailo and I discussed various issues with you. Your assertions about the evolutionary path of societal development were very close to me. I am not a revolutionary. To this day, I like to say that I am an evolutionist. I think that the evolutionist and evolution are all-encompassing processes of the development of nature and society, and it was by this path, the path you took, the path of demanding reforms, of pressuring the government, that perestroika came.

When I speak of double joy, I mean that your arrival coincided with the release of the second volume of my memoirs, where I could not fail to mention the visit of Yuri Orlov to Lviv, and could not fail to mention my visit to Moscow and my visit to Lyudmila Mikhailovna’s apartment. These are memories that will always be with me. I believe that people who did so much to fight Soviet totalitarianism, not only in their own historical homeland, but who spread this idea to other republics, and what’s more, spread this idea throughout the world, and the [Helsinki] movement became worldwide—these people deserve special gratitude. I would very much like us, as political prisoners, to appeal to the President of Ukraine to award such people with the highest award of Ukraine—the Order of Yaroslav the Wise. I believe that this is entirely possible, and that we will achieve it. And I give you this book as a memento.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Valeriy Kravchenko wanted to say something, right?

V. Kravchenko: It is a great harm, of course, for the state, but if society is mired in corruption, then it is natural that the courts also become mired in corruption. To hope for the effectiveness of the courts in a society where everything is mired in corruption—I think there is no hope there.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: There’s no question there, right? Hryhoriy Kutsenko. He is a former Soviet officer, then a former Soviet political prisoner.

Y.F. Orlov: I have heard that name.

H. Kutsenko: I have always followed in your footsteps. First, I lived and served in Zagorsk, and that’s where they imprisoned me. In Lefortovo, I sat in the same cells where you had been. I was in the thirty-fifth and thirty-seventh camps, and they gave me your things, your books. I consider you my teacher, although we were not acquainted. Our common acquaintances, probably, are Lina Tumanova (deceased), Ivanov, Svetlana Balashova, {Sofya Vasilyeva} and other Moscow dissidents. I too, like Oles Shevchenko, who thanks prison for having sat with you, for you having sat with him, I too thank prison. That’s what I named the book, only in Ukrainian: “Thank You, Prison.” I want to give you my memoirs. I join in all the enthusiastic reviews that you are the hope that Russia will nevertheless become more reasonable, because it has such people.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Who else wants to speak?

V. Holoborodko: On behalf of Yevhen Proniuk, I want to convey greetings. Volodymyr Holoborodko. Unfortunately, I don't know you, but I've heard a lot about you. But with you, madam, I was very connected in Moscow. I transported literature to Bolshaya Akademicheskaya, where, by the way, you lived in the late 60s. I was studying philosophy in Moscow at the time. I must tell you that Yevhen Vasylyovych Proniuk invites you and everyone present, right to the office they want to take away. Tomorrow or the day after, any day. Yevhen Vasylyovych Proniuk is the head of the Society of Political Prisoners and the Repressed; I am a member of the Coordinating Council. And he passes on to you the journal “Zona” with signatures. Here you go. Today is the anniversary of the burial of Patriarch Volodymyr on St. Sophia Square, there will be a rally there. May God help you, such holy people, may the friendship between the great Russian people and the especially talented Ukrainian people grow stronger.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Which of the political prisoners would like to say something? Mykola Matusovych, will you not say anything?

M. Matusovych: Nothing special. [inaudible, from a distance] there were lathes and turners. I also tried to learn for myself [inaudible], and when the cops left, they would turn so calmly, [inaudible, interference, laughter]. So I realized that one could sit like that [inaudible, several voices].

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Raisa Opanasivna Rudenko.

R. Rudenko: I personally did not have the chance to meet Yuri Fyodorovich, because somehow we missed each other in Moscow. We saw each other at the Grigorenkos’ birthday on October 18, but there were so many people there that we didn’t get to meet… But I knew him well, because both Mykola Rudenko, and General Grigorenko, and Valentin Fyodorovich Turchin, and Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov—whenever we met, they never talked about anyone as much as they did about Yuri Fyodorovich. Everyone said with one voice that he was the brains, he was the founder of the Moscow Helsinki Group, that he explained how this was the safest method, that it had to be legal, and how effective it would be. Some thought that it would achieve nothing, and only Yuri Fyodorovich Orlov could explain the role the Ukrainian Helsinki Group would play. So, Yuri Fyodorovich, I have known you for a long time, only, one might say, from the words of very authoritative people. And these authoritative people considered you the most authoritative among them, and that is very important.

Y.F. Orlov: I want to answer, perhaps, not only you. Still, one must keep in mind that of the Helsinki movement, the Ukrainian Helsinki Group received the heaviest blows and persecution.

Voice: And the Ukrainian people.

Y.F. Orlov: Well, that of course. The heaviest blows, the largest number of arrested, the greatest number of years spent in prisons, the largest number of deceased—this is all the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. And that was understandable, because Ukraine was very important to the regime, very important. But to arrest us immediately, as I have already explained, was already impossible. This, by the way, indicated that the regime was already weaker than before. Right? Under Stalin, they would have arrested us even before that, even before…

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Yes, and they would have shot us.

Y.F. Orlov: The moment we opened our mouths, and even before we opened them, while whispering under the covers deep at night—we would have already been dead. This already spoke of the regime’s weakness. But still, there is no comparison between the fates of Russian human rights defenders and Ukrainian ones. Ukrainian human rights defenders were persecuted most brutally. We are perfectly aware of this, Lyudmila Mikhailovna and I, we know all this and do not forget it.

L.M. Alexeyeva: The Ukrainian Helsinki Group, how was it created? First, Mykola Rudenko came to Moscow, he came to Yuri Fyodorovich, I remember this because the conversation happened in my presence. Yuri Fyodorovich told him: “Do you realize everything? Do you understand how it will be in Ukraine? Perhaps you could pass documents about Ukraine to us, and we will publish them under our name, because it is very dangerous for you.” And he said: “No, we realize it, we believe that if it is in our name, it will be more effective than if we anonymously pass documents to you.” When they created the Group, they came to Moscow. It was the first group created in the republics, it was on November 6 (Nov. 9, 1976. — V.O.), as far as I remember. And why did they come to Moscow? We held a press conference and announced the creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. That was the only way to announce it then, because there were no foreign correspondents anywhere but Moscow. The Soviet ones didn't come to our press conferences. Western ones came, and not even all of them, but those from the more courageous countries. We even had a document on this… We announced the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, it was our presentation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. We wrote in this document that we ask the international community and the heads of the Helsinki states to pay special attention and to monitor the situation in the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, because these are people who have expressed a willingness to work in the most dangerous conditions, and we are especially worried about them. And it turned out we weren’t worried for nothing, because, as Yuri Fyodorovich is right, arrests began in the Ukrainian Helsinki Group in December, and in our group in February.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: In February. In '77, in February.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Yours were in December '76…

V.V. Ovsiyenko: There were searches.

L.M. Alexeyeva: There were searches, then on the 3rd they arrested…

Voice: On the 5th of February.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Arrested on the 5th? The warrant for the search and arrest of Alexander Ginzburg and Yuri Orlov was signed on February 3. And Ginzburg was arrested on February 3. And this is an amazing story. It turned out there was one KGB captain, Victor Orekhov, who warned that a warrant had been issued for Yuri Fyodorovich, and Yuri Fyodorovich left home. A week later, he came to my place, hoping that my house was not under surveillance. Yes, there was no external surveillance, but as soon as he started talking… In ten minutes, he wanted to leave, but I said: “First we’ll go and check.” I went out with Tolya Shcharansky. Standing in our entryway are a man and a woman, forgive me, with a rear end like this, both in expensive sheepskin coats, and they’re kissing. Well, young people kiss in entryways, not these people in expensive sheepskin coats. They have other places to kiss besides the entryway. Shcharansky approached, and they kept kissing. And he looked like this, and says: “I know that guy, he follows me.” I went up, said: “Yuri Fyodorovich, you can’t leave, they’ve already surrounded the whole place in these ten minutes—the house… So Yuri Fyodorovich was supposed to be arrested on the 3rd, but because he left, they arrested…

R. Rudenko: The arrest warrant was issued for February 3 for Mykola Rudenko, Oleksa Tykhyi, and Ginzburg was arrested on the fifth.

L.M. Alexeyeva: No, no, Alik Ginzburg was arrested on the third. He went out to a payphone to make a call, because his home phone was turned off, and they arrested him.

There was another peculiarity of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. When it was announced, political prisoners who were already in the camps began to join it, knowing they would definitely not be released, but would be given another sentence—and they joined the Group anyway. I said, forgive me: how stubborn! Heroic people, a heroic Group—all of it! And that’s why, when we heard about Ukrainians and especially when I meet Ukrainians—these are heroic people.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Lisovyi, Lukyanenko, and Nina Mykhailivna want to speak—in what order? Nina Mykhailivna first, right? Go ahead, Nina Mykhailivna.

N.M. Marchenko: I will say very little. Why did we come? Here is my sister, here is a young relative who is very interested in the human rights movement that existed even before she was born. Here came Halia, Proniuk's wife. We came to see you, to look at you, esteemed Yuri Fyodorovich, at you, esteemed Lyudmila Alexeyevna, because it was a terrible time… I never allowed the thought that life would twist me so and I would end up in such a stream. I collected two huge briefcases of rejections for the review of my son’s case. My son was arrested, who had just graduated from university and worked for two years as a journalist at “Literaturna Ukrayina.” Today we talk a lot about the human rights Helsinki Group. But you know that the human rights movement in Ukraine began much earlier, in the sixties. In 1972, when a purge of the intelligentsia took place in Ukraine—that was already a human rights movement. They gathered almost all of them. Some ended up in Mordovia, but most were in Perm, in the 35th camp. The leader of this movement was the late, may he be blessed in the next world, Ivan Svitlychnyi. You met Ivan Svitlychnyi many times—right, Lyudmila Alexeyevna?

L.M. Alexeyeva: Yes, I’ll talk more about him—him, and Lyolya, Nadia Svitlychna, when she would visit…

N.M. Marchenko: Yes, a whole family like that. It was a catastrophe, it was a bolt from the blue, when my son was arrested. Lyolya helped me and my sister—she gave us direction on what to do. She knew that no one would release my son, just like her husband. But one had to have at least some connection with someone and moral, spiritual support—that was Moscow, that was you, Tatyana Velikanova, Nina Lisovskaya, Larisa Bogoraz, and especially Malva Landa. She came to visit us, she stayed at our place. It was a huge, I repeat, moral support. These two briefcases of rejections to all my appeals, to all my addresses to higher authorities, Moscow and Soviet, Shcherbytsky and Fedorchuk, and Brezhnev, and Rudenko, after Rekunkov—it’s terrible to remember, but these two briefcases pushed me towards you, the human rights defenders. And it was a tremendous help. In the most difficult conditions, to write, save, and get information out through a visit, for which I wait a whole year to see and feed my son, and instead he waits for me to leave sooner… I am seeking his pardon, and he is dragging me into a completely different affair. I saw his trembling hands, I saw his pleading eyes, I saw his great desire to help his friends who are in the camp—I didn't have the strength to refuse him. That was the first trip. Then there were several more such trips, until we were deprived of visits. In short, there was a mass of everything, but the most terrible thing was that he was already under pressure. They did not forgive him for the enormous amount of information that was going abroad. I, honestly, didn’t need it, but I couldn’t refuse him…

L.M. Alexeyeva: He needed it.

N.M. Marchenko: He needed it very much, and I could not deprive myself of the happiness of knowing my son as my own kin in everything. And I probably would not have forgiven myself to this day if I had not supported our love and friendship. When young people ask what the human rights activists achieved, I answer: they showed high morale and the deepest unwillingness to submit to totalitarianism, to the banditry that continues even now in both your country and ours. This spirit, with which a great number of people were infected, helps many even now.

L.M. Alexeyeva: You spoke about your son, and I want to speak about Ukrainian women, about your mothers, about your wives, about your sisters. You see, I met most of you only after I returned from emigration, when you came to Moscow or when I came here. But I had known you for a long time, and I knew you very well, and I cared for you—because your women came to us. I got to know them first—your wives, your mothers, your sisters. Nadia Svitlychna, Raya Moroz, all of them. And my home in Russia was called the “Ukrainian inn,” because Ukrainian women came to my place, because whether you’re going to Mordovia or to Perm, it’s all through Moscow anyway. So you have to stop in Moscow, you need someone to stamp your tickets, you need to wash up and rest somewhere, not spend the night at the station, and, most importantly—to buy food that would simply spoil while being transported. We would buy it in advance in Moscow and save it for that day, that “salami” that doesn't spoil, or we’d run to the market to buy something. They would arrive, wash up, sleep, we would prepare everything together, and the next day we would see them off to the train. If the load was heavy, one of our men or sons would go to help carry the heavy bags. I was very proud that Ukrainian women came to my place first. And not because I was born in Crimea. When Daniel was still free, Ivan Svitlychnyi used to visit him, and I met Ivan and Lyolya at their apartment. I must say that Ivan Svitlychnyi was the first person to explain to me that, as it turns out, Ukraine was oppressed. I said: what do you mean oppressed—we have all sorts of Kirilenkos and Kirichenkos in our government, so it depends on who is oppressing whom. But they told me about the camps. I learned about the Lukyanenko and Kandyba case from them. And Ivan knew Ukrainian history very well. There sat Daniel, Larisa Bogoraz, me, and another two or three people, and he’s reading Hrushevsky to us. Well, then I had to read those books too. And the first acquaintance was through Svitlychnyi and Lyolya, and the second—Nina Strokata. It happened like this. She came for a visit with her husband, and Larisa came for a visit with Daniel. They had already had their visits. This was in the eleventh camp. They were being led from the work zone to the living zone. And the wives, to see their husbands one last time, stood nearby, but they didn’t know each other and didn’t look at each other. And Daniel shouted to Larisa: “Get to know her!” And pointed to Nina. But Larisa didn’t hear properly and looked confused: “He said something…” And those walking behind said: “He told you: get to know her!” And she turned to Nina and said: “I’m Daniel’s wife.” And Nina said: “And I’m Karavansky’s wife.” They hugged and traveled to Moscow together. And then Nina introduced me to Larisa. They started telling me why Karavansky was imprisoned: that in Odesa there were Russian schools instead of Ukrainian ones—we knew none of this. We, of course, were very sympathetic and we listened to her. She said: “But you don’t know anything! You need to be educated!” And Lyonya Plyushch and others undertook to translate Ivan Dziuba’s “Internationalism or Russification?” They translated it into Russian. Because I, for example, when Ukrainian is spoken, I understand almost everything, but I absolutely cannot read in Ukrainian. I don’t understand, it’s easier for me to read in German—I don’t know, I can’t. They translated “Internationalism or Russification?”, they started translating other documents and bringing them to Moscow specifically for us to distribute Ukrainian samizdat among Russians. And Nina amazed me, she said: “I never thought we would find like-minded people under the shadow of the Kremlin!” And Luda: “What makes you think we are under the shadow of the Kremlin? We are under the same shadow as you are.”

Voice: We were all under the shadow of the Kremlin.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Yes, exactly. And you know, maybe because of Svitlychna and Strokata, my apartment became the “Ukrainian inn.” And that’s why I came for the thirtieth anniversary [of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group], I went to Romaniuk’s grave. His wife Maria visited me many times with their son. Some priest is bustling about there, I don’t even pay attention, and he comes up and says: “You don’t recognize me?” I say: “I’m sorry…” — “I’m Tarasyk Romaniuk.” And I had seen him when he was this little, when she took him to the camp. Of course, I didn’t recognize him as an adult. But he recognized me. And Raya Moroz traveled with her son Taras...”

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Valentyn, the son is also Valentyn.

L.M. Alexeyeva: Really? For some reason I thought his name was Taras. I must have been mistaken—Romaniuk’s son is Taras. In short, all of them. We knew from the wives and mothers what Ukrainians had to endure. We learned from them first, from your wives. Such a horror was revealed to us… There was nothing like it in Moscow, although in Moscow they didn’t pat you on the head either.

V.V. Ovsiyenko: We have been sitting for two hours already, there’s coffee waiting for us, but Lisovyi, Horyn, and Lukyanenko still want to speak.